#and the endfield trailer and now this

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Me: Man, I just really don't care for the direction the Kazimierz stuff went in. And I feel so disconnected from the mainline plot because I'm still stuck in Chapter 6 while everyone else is on like, 11 or 12 or something.

Me: And given the aforementioned Kazimierz problem, am starting to wonder if the Reunion plot is really going to land as well as I had hoped, either; is the neoliberal vibe a problem unique to the jousting honses, or is that just the canary in the coal mine? Between all that and the gameplay burnout, maybe I should just back off more for a while...

Hypergrif: Winged Serpents real, hot evil feathered snake milfs spotted in your area.

Me: Fuckit, I can stick around a while longer yet...

#not a reblog#arknights#memes aside#between dusk and ling's events#bringing me back into playing for a while each time#and the endfield trailer and now this#keeping my fan morale intact#when it was running low#it feels like whenever I'm wavering#the trick to pull me back in#is either sui siblings or space shenanigans#the most mythological and most sci-fi extremes#of the genre spectrum#good stuff#but also yeah#ho'olheyak is a vibe

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

it's kinda funny just how much worldbuilding and lore Endfield is giving out for free. just one translated image was enough to piece together a mostly complete overall timeline while referencing only the current state of the global server (though if the translation is somehow incorrect, that throws the wrench back in, but so far i haven't seen anyone give a corrected TL).

#arknights endfield#arknights#holding myself back from actually saying any of this here until i can grab a couple friends and bounce the ideas off them#but it is kinda funny how i was correct about one aspect of the trailer that i temporarily got convinced i was misreading#bc endfield comes back the very next day or even overnight with stuff that supports my reading of it#mixed feelings still overall for the decisions they've made from a game dev standpoint but the lore is still fun to follow for now

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Cinematech's Trailer Park - Arknights: Endfield (Multiplatform)

"I'm here for you now, Endministrator."

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

I guess talos-II is terra that a space-faring civilization in the far future, which also uses originium, is trying to terraform:

terra's currently inhabited by lifeforms called the aggeloi which are speculated to be endemic to the planet:

so eventually arknights terra went to shit. how much time has passed? how many centuries did patriot's statue just stand there, enduring in a desolate planet? wild

but then, aside from the smug kal'tsit lookalike we also have this fellow in the background of the promo image:

and totally not angelina:

and rhodes island still exists alongside endfield, which I assume is another company:

and the voice at the end of the trailer, perhaps jokingly, asks the player: should I call you the Doctor? so the Doctor is a known figure.

I guess eventually terrans noped out of terra, and doctor likely remained a key player in keeping humanity alive, and somehow rhodes island persisted for a long, long ass time on the new planet, but their original planet was forgotten along with the name terra and is now being treated as a new frontier by people who likely originated from terrans?? and they're trying to reach north again? also gacha player character has amnesia, how novel

bruh isn't this patriot?

hello? what?

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

19/3/22 and the little things we know about Arknights Endfield

hello hello welcome back to my a9 nonsense rambles and i write this while redownload mumu because now./gg denied my ggplay. no i havent check the tags on this site yet and probably won’t in near future.

note: everything is from the official website and looting from discord to deal with my assumption.

so first we have this

talos-II

the ‘II’ part is actually nothing deep, really. terra is ‘terra 0′, es astris is probably gonna be ‘something-I’, and endfield is talos-II. it’s just their way of naming.

more info according to wiki: Talos - also spelled Talus or Talon was a giant automaton made of bronze to protect Europa in Crete from pirates and invaders, in greek mythology. on the newest CG trailer, the transmission beginned from the space, from a spaceship outside the planet. so with the introduction says ‘explore this world’, we can safely establish A9End that the whole land itself gonna oppose the players, which i suppose is the catastrophes and this:

inorganic swarming constructs is that punishing gray raven

mons3tr, a.k.a. kal’tsit spine, is neither a manifestation of originium arts nor a true living creature. and base on the beta art then mons3tr and those constructs more or less are of a kind. can’t wait to see mons3tr in A9End.

the first pioneers toiled for years to establish a foothold

which means there are many more factions/teams/companies. welcome to Asian OW gacha game. let’s hope that HG can do better than Hoyoverse (tho i love both)

i wonder if there’s native talos-er, besides those inorganic constructs?

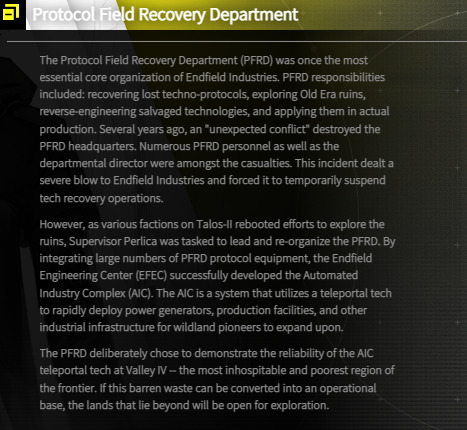

it seems that Endfield Industries itself is everything in space exploration / neverland founding field, and ‘we’ are going to be a part of PFRD first. PFRD seems to be an important part which its shutdown strikes at the whole industry. not sure if the tech they’re tasked to recover is the Old Era tech or their own tech (bc y’know, techies from the main house on space probably are expensive, or a chance that those inorganic constructs can absord new and higher tech to evolve themselves as we have seen in one certain case: the seaborn) but maybe both.

originium

so far we’re not sure what th is catastrophe on talos-II and if it’s the same type of catastrophe terra-0 has, nor we know for sure if talos-II has originium and oripathy. i don’t remember the originium catastrophe on terra can physically distort enviroment to the point it creates phenomena, so the Corruption probably another kind of catastrophe.

but does talos-II have originium catas? yes, originium engines exists, so there is originium catas and the pioneers have been exploiting its power for years

this colonel sanders might or might not has oripathy on his head. (btw he’s mgs5 parody lol Lowlight can you stop doing meme)

so i say that in this timeline, oripathy might yet to be a global crisis.

the timeline

well, in case A9 and A9End place on the same planet

you see, the auto this lupo / vulpo is holding is some high tech that not even columbia got, anyone who’s obsessed with terra industries lore can see that. so now we’re basing it on gun now.

exusiai’s file:

the word ‘discovered’ in chinese is 发现, which is discover.

this is the part about gun in A9 artbook, rough translation under (thanks friend)

Gun weapons, shortened as guns, also known as firearms, are a type of weapon that uses spells to pressurise the projectiles to long distance targets. Compared to other weapons, guns belong to a type of new staff type weapon.

The structure resembles wands (Originium firing gear) – crossbows with gun core, which seems more suitable in the study of human factors. The structure of guns is more complicated. Besides requiring a certain industrial standard to manufacture, the user also needs to possess basic shooting skills and basic Originium Arts talent. Besides needing good aiming technique, the strength to control recoil after firing the gun, a well-versed gun user also needs precise, stable, and high frequency spell ability.

On Terra, most guns are produced in Laterano and are used by the Laterano people. Some Columbian technology companies have attempted to create some simple imitations of gun weapons. And to most non-Laterano people, gun weapons are not a type of practical weapon.

A note from translator: 铳 is really just the olden Chinese way of referring to the modern 枪. And based on the other gun related lore, 铳 seems to refer to Laterano guns while 枪 refers to other non Laterano guns. You will see 枪 when it comes to the more unorthodox guns: Sesa and the Rainbow Squad. Sesa himself is an anomaly and a potential catalyst in the gun lore, with his potential to change it in the future with his (brother’s) invention of guns that do not require Originium Arts.

it’s clear that gun on terra is found, not invented. it’s a bit less clear that technology on terra is underdeveloped. yeah, they don’t even have plane. they have helicopter, but what kind of helicopter flying so low that it got shot down by a shoulder cannon? (gravial event if you ask). even specter and gladiia said oldfashioned. terra’s tech is very underdeveloped, especially if the terrans didnt have much choice but develop the things that mainly help them survive the catastrophes.

so again, gun on terra is found and monopolized by laterano. RI itself is a 800 meter-long landship digged up from under dirt by Babel, which means the landship’s based tech belongs to older times. not sure if the terran invented the nomadic cities themselves (probably not given their standard technology, the nomadic city’s tech is definitely higher than that) but:

‘settlements and nomadic cities sheltered by massive walls formed a new foundation for our civilization.’ this means the nomadic city tech, in fact, either exists long before A9End starts or it’s started by the pionners. so i wouldn’t be surprised if A9 later reveals that nomadic city’s core tech isn’t the terran’s.

Old Era and A9End in trailer seems to possess higher tech than A9 too. so yeah, assuming the timeline like this:

Old Era -> A9End -> ... -> A9

something happened with the Old Era first; then the pioneers A9End a.k.a ourterspace men came to recover Old Era’s things and establish new civilization with their high tech; then something happened to them too; then long and long and long shit after shit we got Arknights! when climate somehow became worse and has given birth to countless originium catastrophes and resulted as the suffusion of oripathy and nomadic cities, also the weird mixing technology between the terran’s own tech and the old old tech from both Old Era and A9End era.

...

one more thing

HYPERGRYPH I DEMAND EXPLAINATION

(what if Yan’s shadow has been running since True Lung’s time? what if A9End’s timeline is also True Lung’s timeline????)

#arknights#arknights endfield#im not high while writing this yay#for the first fucking time#man i play too many gacha games

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sound of Fury

“America, as a social and political organization, is committed to a cheerful view of life,” Robert Warshow wrote in his seminal 1948 essay “The Gangster as Tragic Hero.” Democracies depend on the conviction that they are making life better and happier for their citizens; only feudal and monarchical societies can enjoy the luxury of fatalism or a fundamentally pessimistic view of life. Praising the gangster genre as a form of modern tragedy, Warshow also accounts for film noir in his statement that, “There always exists a current of opposition, seeking to express by whatever means are available to it that sense of desperation and inevitable failure which optimism itself helps to create.” The gangster’s demise is the purest American tragedy because it is driven by his mania to climb the ladder of success. The end of his saga is inevitable, so in chasing success he is really chasing failure; his self-destructiveness expresses defiance at the inevitability of defeat, but also confirms it.

This underground river of pessimism and disillusionment unites the pre-Code films of the early thirties and postwar film noir; they share a tone of bitter gallows humor; a satisfaction in being wised-up, knowing the score; they flaunt the scars and calluses of lost innocence. Pre-Code movies reflected the free-fall of the Depression, the farce of Prohibition and the dizziness of a society edging towards anarchy. Noir exposed the suppressed anguish of WWII, the anxiety of the Cold War, the stresses of conformity and materialism.

Films like Cry Danger (1951)—recently restored to full glory by the Film Noir Foundation—depict a battered, abraded country that has turned cynicism into a running gag. A man just out of prison after serving five years for something he didn’t do trades sour wisecracks with a one-legged, alcoholic ex-Marine. They make their home in a dilapidated trailer in a scruffy park perched on Bunker Hill, where the proprietor sits around strumming a ukulele and ignoring the busted showers. The vet (Richard Erdman) falls for a pickpocket who steals his wallet whenever he gets drunk. The ex-con (Dick Powell) idealistically tries to vindicate his best friend, who’s still in jail, only to find out he’s a double-crossing liar. The film achieves an extraordinary blend of the glum and the snappy, a deadpan insolence that saturates the air like smog. “What’s five years?” Powell says of his stretch. “You could do that just waiting around.”

While pre-Code movies gleefully portrayed an “age of chiselry,” a country where everyone was looking for an angle, they never plumbed the depths of alienation, fatalism and misanthropy that noir opened up. For all their knowing skepticism, Depression-era films evoke a sense of camaraderie, a shared body heat from people huddled and jostling together—maybe cheating each other, but still sharing jokes and boxcars, Murphy beds and stolen hot-dogs. Noir, by contrast, purveys a chilling sense of isolation and social atomization; not only institutions but individual relationships are corrupt and predatory. There’s no longer a hard-times sense of being all in the same boat. As Kirk Douglas nastily smirks at his colleagues in Ace in the Hole: “I’m in the boat. You’re in the water.”

Noir used unpretentious, low-budget crime thrillers to smuggle this caustic vision into movie theaters during a time when, on the surface, America was at the height of prosperity and social cohesion. Unlike the early-thirties gangster cycle, which reflected a real wave of lawlessness, the crime movies of the fifties were made during a time when the murder rate was lower than in previous or succeeding decades, perhaps as a channel for other, submerged anxieties. Noir’s prophetic vision of disintegrating communities has become only more compelling with time, a development that may explain the passionate revival of interest in film noir in the last decades of the twentieth century.

Healthy, functioning groups don’t exist in noir; even gangs and criminal “organizations” fall apart because their members are out for themselves, ready to betray each other for a payoff or a bigger share of the take. Institutions like politics and business appear only in stories revealing their corruption. The police are the only representatives of government commonly seen, and they are often bullying and crooked, hounding innocent suspects with sadistic relish. Even films that take the side of law enforcement underline hostility between cops and the people they protect. Apart from the justice system, the public sphere does not exist: the town meetings and popular movements that crowd the screen in thirties films, with indignant and excitable citizens marching, rioting or celebrating, are unimaginable in film noir. People seem to exist in a vacuum.

In part, this vision reflects the privatization of life that accelerated in the postwar era, as cars replaced trains; television replaced movie theaters; appliances eliminated the need for servants, milkmen and ice men; suburban back yards took the place of parks, all part of the glorification of the detached home for the “nuclear” family. The homogeneity of the suburbs and the intrusiveness of media and advertising paradoxically diminished any sense of place or community. Meanwhile, Cold War paranoia meant that expressions of communitarian spirit or calls for collective action could rouse suspicions of communist sympathies.

Many of the writers, directors and actors associated with film noir were liberals, often former Communist Party members who had seen the left-wing idealism of the thirties buried by World War II and then vilified during the Cold War. Disillusioned, they used crime movies to indict a culture of rampant greed and cut-throat competition. Thieves’ Highway(1949), the last film directed by Jules Dassin before he left the country to escape the blacklist, slices open the produce business to reveal the rotten heart of capitalism. Even something as pure and nourishing as an apple becomes a poisoned agent of strife when it’s equated with money. A Polish farmer, enraged at being paid less than he was promised for his apples, flings boxes of them off a truck, screaming, “Seventy-five cents! Seventy-five cents!” The apples roll wastefully across the ground, an image foreshadowing the film’s most famous shot, when after the same truck has careened off the road and exploded, apples roll silently down the hillside toward the flaming wreck. When the dead trucker’s partner finds out that money-grubbers have gone out to collect the scattered load to sell, he begins kicking over crates of apples, fuming, “Four bits a box! Four bits a box!” Everyone in the movie is “just trying to make a buck,” and cash haunts the film, dirty crumpled bills changing hands in a series of soiled, coercive transactions.

It is easy to see why the House Un-American Activities Committee wanted to drive people like Dassin out of Hollywood. Films such as Joseph Losey’s The Prowler (another Film Noir Foundation restoration) and Cy Endfield’s The Sound of Fury, (a.k.a Try and Get Me! 1950, the FNF’s next project) are scathing attacks on a materialistic society, unmasking the American dream as a shallow and shabby illusion that breeds crime and shreds the social fabric. (Both directors fled to England in the early fifties to avoid persecution by HUAC.)

Endfield’s stark anti-lynching drama opens with a down-on-his-luck family man hitch-hiking on a dark highway; he tells the trucker who picks him up that he’s been looking in vain for a job. Howard Tyler (Frank Lovejoy) moved his wife and son out to the postwar California suburb of Santa Sierra, hoping for a better life; “I can’t help it if a million other guys had the same idea,” he complains bitterly. They live in a shabby little bungalow behind a wire fence that makes the place look like a miniature P.O.W. camp. Howard’s pregnant wife hates the idea of using a charity clinic, and frets over money owed for groceries, while his whiny little boy begs for money to go the baseball game (“All the other kids are goin’!”) A bartender at a bowling alley sneers at his cheap customer: “You take a beer drinker, you got a jerk.” If Howard weren’t so dejected and humiliated, he would never fall under the spell of Jerry (Lloyd Bridges), the vain braggart he meets at the bowling alley.

Primping and preening, flexing his muscles and showing off his fancy aftershave (“Smells expensive!”), the manic Jerry boasts about his sexual conquests and the big money he makes, and he treats the modest, submissive Howard like his valet. He offers to put him onto something good—“nothing risky”—just driving the car for his hold-ups. When Howard hesitates, Jerry snorts, “You guys kill me! The more you get kicked in the teeth the better you like it.” Their first job is knocking over the grocery store at a cheap motel (“The Rambler’s Rest”), where Jerry easily intimidates an elderly couple and pistol-whips their son. Intoxicated with the easy money—and a few stiff drinks—Howard bursts in on his family with armfuls of groceries. His wife gasps at the extravagance of baked ham and canned peaches, and he brags that now they can get their own TV, and won’t have to go over and watch their neighbors’. “And we’ll throw this piece of junk away!” he crows, pointing to the family’s radio. Soon Howard is buying his wife new shoes and dresses with hot money, telling her he has a night job at a cannery. His little boy sports a cowboy outfit and ambushes his jumpy father with toy guns.

Unsatisfied with these penny-ante crimes, Jerry comes up with a scheme to kidnap a wealthy young man and hold him for ransom. He’s overcome by envy as he fingers the victim’s suit, tailor-made in New York, and after they’ve taken him out to a gravel pit in a disused army base, Jerry panics and kills him. When Howard gets home, dazed with horror and guilt, his wife wakes and tells him about the lovely dream she was having: she had the baby and this time there was no pain at all; “I got right up out of the hospital and took her shopping. I was buying her a pinafore.” Even in her dreams she’s a consumer, subconsciously linking commercial goods with the fantasy of a painless life.

As Howard mentally unravels, the shoddy vulgarity of the culture around him takes on a sinister cast. Jerry shows him the ransom note he’s written in a diner while ordering a steak sandwich (“Cow on a slab!” the waitress yells.) For cover, they go out of town to mail the letter, taking along Jerry’s girlfriend, a glossy blonde, and a lonely manicurist she has dug up for Howard. In a nightclub, he’s subjected to a string of dumb jokes and parlor magic tricks from a burlesque comedian. “Blame my psychiatrist,” the comic quips, “I didn’t pay my bill last month and he’s letting me go crazy.”

From its opening moments, the film depicts the crowd as a mindless and malevolent force, which will eventually be stirred to frenzy by sensationalizing newspaper articles. Crowds in noir are always bloodthirsty mobs, surrounding and destroying strangers in their midst; the communal desire for security is tainted by bigotry and ignorance. This is a dark inversion of Capra’s rallying citizens, or even the all-for-one armies of bums who fight for their squatters’ rights in Wild Boys of the Road. Movies of the Depression era never saw anything wrong with wanting money, good food, a pair of shoes, or even fur coats and diamond bracelets. They are tolerant of people—especially women—who do whatever they have to do get ahead. By contrast, The Sound of Fury shows materialism—the desire to keep up with the neighbors, to make a better life for your family—as a force that corrodes souls and breaks down social decency. The deepest well of pessimism in noir is a distrust of change, desire and ambition. “I just want to be somebody,” people are always saying, but the urge to squeeze more out of life, to grab a chance at happiness, is brutally punished.

Below the surface, the force driving noir stories is the urge to escape: from the past, from the law, from the ordinary, from poverty, from constricting relationships, from the limitations of the self. Noir found its fullest expression in America because the American psyche harbors a passion for independence, an impulse to be, in the words of Walt Whitman, “loosed of limits, and imaginary lines, / Going where I list, my own master, total and absolute.” With this desire for autonomy comes a corresponding fear of loneliness and exile. The more we crave success, the more we dread failure; the more we crave freedom, the more we dread confinement. This is the shadow that spawns all of noir’s shadows: the anxiety imposed by living in a country that elevates opportunity above security; one that instills a compulsion to “make it big,” but offers little sympathy to those who fall short. Film noir is about people who break the rules, pursuing their own interests outside the boundaries of decent society, and about how they are destroyed by society—or by themselves.

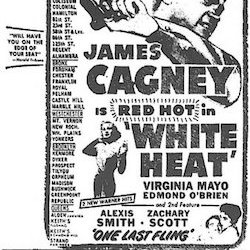

The gangster, Robert Warshow wrote, is driven by the need to separate himself from the crowd, but in doing so he isolates and dooms himself. White Heat (1949), which brought James Cagney back to the gangster persona that made him a star, came out one year after the publication of “The Gangster as Tragic Hero.” It took the “man of the city” (as Warshow defined the gangster) out of the city, but Cagney’s explosive death atop an industrial gas tank is the supreme illustration of Warshow’s observation that the gangster’s pursuit of success—“Made it, Ma! Top of the world!”—is a pursuit of death.

White Heat is also a perfect example of what Edward Dimendberg (in Film Noir and the Spaces of Modernity) called “centrifugal” noir: it’s a film without a center, about a world flying apart like the cooling fragments of an exploded star. Cagney’s gang, decaying under the strains of resentment, betrayal and madness, moves between equally bleak urban and rural hideouts. After robbing a train in a rocky no-man’s-land, they hole up in a frigid, creaky old farmhouse “a hundred miles from nowhere,” as Cagney’s wife gripes. Cooped up together in this gloomy Gothic house, surrounded by split-rail fences and naked, rolling hills, they snipe at each other and grumble about their leader. Cody Jarrett (James Cagney) suffers debilitating migraine headaches and huddles in the lap of his gaunt, fiercely loyal Ma. The realization that came to Cagney in Public Enemy as he stumbled into the gutter in the rain—“I ain’t so tough”—is here amplified into an infantile weakness, perpetually on the verge of breakdown. Cody’s frailty only makes him more vicious. At his orders the gang leaves a wounded member behind, bandaged and in pain, to freeze to death once they make their move to a motor court in LA. The motel is typical of the “non-places” (in Marc Augé’s term) where noir flourishes: marginal, transient spaces where “people are always, and never, at home.”

The banality of the modern west makes room for Cagney’s majestically psychotic performance, fine-tuned and sensitive as a landmine. Cody Jarrett crumples inward under the crushing pain and then erupts, and White Heat similarly closes in and then shatters people are either cramped in suffocating enclosures (Cody shoots a man while he’s locked in the trunk of a car, cruelly offering to “give him some air”), or stranded in vacant, inhospitable spaces. At the rural hideout, the wind is always blowing bitterly around the house, tossing the trees; Cody walks alone at night, talking to his dead mother, who was shot in the back by his wife while he was in jail. He tells a friend—really a police plant who will betray him—how lonesome he is, because “all I ever had was Ma,” and how hard his mother’s life was, “always on the run, always on the move.” White Heat brings together the ultra-modern—radio tracking devices; drive-in movie theaters—with the pre-modern, even the primitive. It proves not just that film noir can thrive in the country as well as the city, but that noir was not merely a response to the new—industrialization, the bomb, etc.—but drew on deep veins in the American psyche and the American landscape: the desire to stand alone on top of the hill, even if there’s nowhere to go from there but death; and an accompanying fear of being buried “on the lone prairie,” having no one to talk to but the night wind.

by Imogen Sara Smith

#Imogen Sara Smith#The Chiseler#The Sound of Fury#James Cagney#White Heat#Raul Walsh#Noir#In Lonely Places: Film Noir Beyond the Cit#Buster Keaton: The Persistence of Comedy#the criterion collection

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Endfield Announcement

It is now the official Endfield Announcement by Chinese game development company Hypergryph that has launched Arknights: Endfield. The official website for the game features some artwork as well as more details regarding the game's settings as well as the gameplay as well as CG trailers.

0 notes

Text

What To Expect From Arknights Endfield After the Announcement From Hypergryph?

Many video game franchises have made the transition from PC to mobile over the years. However, few companies have made the switch in the other direction.

Many companies managed to accomplish this feat in 2020 when they simultaneously after releasing for mobile and console. Now Hypergryph is ready to achieve the same feat with アークナイツエンドフィールド afterAnnouncing Hypergryph Arknights.

The Arknights original mobile tower defence game, with RPG elements, was released on mobile devices in 2020. It was instantly a success. Hypergraph revealed that the mobile game had received over one million preregistrations before it was launched outside of China. Arknights proved to be a popular game due to its addictive gameplay, a rich storyline and subtle gacha mechanics.

Hypergraph revealed that Arknights would become a franchise on March 17th, with the next Arknights: Endfield entry. The new game will retain some of the same strategy elements as the original game, but it will be a 3D real-time RPG. エンフィールド will have the same "worldview" as Arknights. However, it will be set on a completely new planet with a new cast and storyline.

HypergryphがArknightsを発表 with some concept art, a trailer and a gameplay demo for Arknights Endfield. The footage feels very similar to some of the locations from PlatinumGames' action RPG Nier: Automata. The gameplay video shows a glimpse at the map interface. It seems to have the same futuristic aesthetics as Arknights' UI. The video then cuts to the two characters running through desert locations before they reach a vibrant oasis. The demo's manmade objects seem to have been abandoned long ago, giving the area an apocalyptic feel.

Arknights Endfield takes place on a planet called Talos-II. Players embark on a dangerous mission to find a home for themselves in this hostile world. There are vast expanses of unexplored land beyond the colonies. Players work with Endfield Industries, a company that aims to discover the secrets of this abandoned planet, which once supported human life.

While the RPG game's gameplay will be different, players will still be able to control a party and complete missions. They can also unlock chapters that will help them progress their story. Battle will take place in real-time in Endfield, unlike the turn-based combat in arknights. Players will face a variety of enemies and factions.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hypergryph Announces Arknights: Endfield for PC and Mobile

Hypergryph, the developer behind the successful mobile tower defense game, announces the next title in the franchise, Arknights: Endfield.

Over the years, several video game franchises have successfully made the leap from PC or console to mobile. Call of Duty: Mobile has proven to be so popular that Activision recently announced that a mobile version of Call of Duty: Warzone is in the works as well. Fewer companies have managed to make the move in the opposite direction, however. MiHoYo kind of accomplished the feat in 2020 by simultaneously releasing Genshin Impact on console and mobile, and now developer Hypergryph hopes to do the same with Arknights: Endfield.

The original Arknights, a free-to-play mobile tower defense game with RPG elements, was released on mobile devices in 2020 and was immediately a hit. Even before launching outside of China, Hypergryph announced that there were over one million pre-registrations for the mobile game. Arknights proved to be popular due to its addicting gameplay, detailed storyline, impressive graphics, and gacha mechanics that weren’t too obtrusive.

Hypergryph announced that Arknights would be a franchise, with the next entry called Arknights: Endfield. The new game will be a 3D real-time RPG that retains some of the strategy elements that fans enjoyed in the first game. While Endfield will possess the same “worldview” as Arknights, it will take place on an entirely new planet, introduce a new cast of characters, and feature a unique storyline. The game is currently in the early stages of development for PC and mobile devices, and there is no word of a planned release date yet. There has also been no mention of a possible next-gen console launch.

So far, Hypergryph has shared some concept art, a trailer, and a gameplay demo of アークナイツエンドフィールド , and from the footage so far, the game feels reminiscent of some of the locations in PlatinumGames’ groundbreaking action RPG Nier: Automata. The gameplay video gives viewers a glimpse of the map interface, which seems to feature the same futuristic aesthetic as the UI of Arknights. Then the video cuts to two characters running through various locations in a desert locale before reaching a vibrant oasis. Manmade items in the demo seem to be long abandoned, giving the area a post-apocalyptic feeling, which matches the theme of Arknights.

The game will feature new gameplay mechanics, though players will still control a party, have missions to complete, and unlock chapters to progress the story. Unlike the turn-based combat in Arknights, battle in Endfield will take place in real-time, and players will encounter a variety of enemies and factions to defeat.

1 note

·

View note