#and sure you have a bit of a guide with the storyboard underneath and any onion skins you got active

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

im watching a professional animator on twitch rn and its crazy how, like... hes drawing entire frames so quickly.. thats what years upon years of practice and working on art and animation does to a mfer

#like hes not sketching at all hes just freehanding the lineart right off the bat#and sure you have a bit of a guide with the storyboard underneath and any onion skins you got active#but like even the wildly different hand angles when the character is gesturing quickly so theres not any similar reference for it.. so quick#ive been watching for like an hour and a half or two hours and in that time hes done most of the lines of like... 7-8 seconds of animation#like... fuckin inspirational i wanna get good enough that i can draw that fast and consistently LOL

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

planning a story

Planning a story goes differently for all writers but is useful regardless of style. The plan and plot are the two main components of the skeleton of your tale (the characters being the heart) and go a long way when coming to write your story. An issue that many writers face today is that they know where they want to go by the end but not how they will get there. This is a reason why planning is an essential step before and during the process of accomplishing your goals. Whether you are a do-er or a thinker, this guide can come in handy and give your big idea a backbone.

Most people know the fundamental conflicts, characters, and goals of the story but cannot precisely grasp the ins and outs of their plan, missing out on some extraordinary plot twists and details that would otherwise be present if they had thought it through. Though a huge part of writing is the thought-dumping within it, we must make that those thoughts are comprehensible for others to read as well. We have to give ourselves motivation and a plan for how we will make them into a unified piece. Below are some neat tips and common sense that should be kept in mind when completing the plan.

Keeping A Journal/Notebook

Maintaining a physical copy of your thoughts is crucial when coming to plan. Whether it is noted on a laptop or scribbled on a napkin, you should have an account of what you were brewing in your mind that will help you later. No matter how insignificant or silly it may seem, you should write everything that comes to mind. I cannot tell you how many times I wished that I'd written down or remembered a small detail from before only to have it gone in an instant. Unfortunate, yes, but I learned to document because of it.

These things can include small excerpts, quotes, twists, ideas for characters, ideas for events, and pretty much anything else. The sky's really the limit here.

Have a Basic Sense of Your Story Before Your Plan

Super simple. Exposition, Conflict, Rising Action, Climax, Falling Action, Denouement. You know all of this but in case you forgot, I'll put a little summary underneath.

Exposition: Setting, main characters, foreshadowing (although it can be present all around), and an introduction. Who is your story going to be about? Where are they? Give us a taste of their personality before we begin so we can connect and anticipate what will happen next.

Conflict: What's the problem of the story? How does the character find this out? Is it that they won the lottery and don't know what to do with the money or are they held at gunpoint in a Chinese Resturant? This is the central conflict of the story, but there can be more mini ones later on, which we will find in rising action. (Note: it is possible to start your story with conflict, however, make sure to include the exposition as you go on and about)

Rising Action: How are your characters trying to achieve their goals? How did they develop and what did they learn? What were the hurdles along the way and how did it shape them to be the people that they are? If you are writing in mystery, be sure to mull this through. The rising action is the bulk of the story and should not be taken lightly.

Climax: Is it a plot twist? A grand revelation? The ultimate fight scene? In any scenario, it's the most intense bit, and we discover the results.

Falling action: everything from the climax and rising action coming into place. This is where you decide if the character has resolved the conflict or not and how things are settling down.

Denouement: Aftermath. An epilogue maybe. It goes hand in hand with the falling action and shouldn't be too long. It's basically just ending your story.

Point of View

How will you tell the story and how will that cater to your readers? First person or third person? Past tense or present tense? Remember, this depends solely on your preference and comfort, no one being better than the other. Though past tense with third person may be traditional, it is not out of date, the same for present tense with first person not being careless. Most readers don't judge stories based on this so leave it up to yourself to choose. You are writing your story, the one that you've worked so hard on so be comfortable with it!

So, this may have been pretty elementary but do not forget it! You must at the very least know these details and write them down in a place where you can expand on them later. Also, this is BEFORE you start to write. Yes, you can add on more (something I will be touching on in a short bit), and you can also keep notes at the bottom of your document, but this is the bare minimum. Do it, and you'll thank yourself later.

[For those who don't need to plan as much, feel free to scroll to the bottom for organization ideas. You can also, as I stated earlier, plan while you are writing your story. This can be found below]

So, we've finished the basics but for those of you wanting a more elaborate storyline, expand. The following are some methods of doing so.

Do Your Research

Is your story based on a real-life event or setting? If so, research! Find out how life is/was like there, if the area was large or small, highly populated or not. What are/were the norms? Please don't lay out every detail but rather, be aware of them, applying them to your character and plot when necessary. I mean, how will your character live otherwise? Although it's fiction, we can't have a man in the 1720s scrolling through Tinder now, can we? (unless that's your purpose, of course)

I know it may be a pain, but it's loads of help too! Trust yourself and go ahead.

Build Your World

Writing fantasy? Think it out! What is your universe like? The laws? The norms? I, personally, don't have too much experience in this area but I am sure that you can find a post or article that will highlight it. In fact, here you go!

Character Development

Where has your character come from? How did they get from A to B and what lessons did they learn to do so? What are your As and Bs? I'll put up a character development post soon enough, but for now, you can refer to this.

Details

What additional information do you need? Is it the placement of a can of beans that will be crucial later on or a slip in an antagonist's dialogue? Write notes as to how this will be important later in your story and why. Stick to the key events and let your writing do the rest.

DO NOT plan out your WHOLE story. Yes, chapter by chapter is okay, but not everything down to the T. Give yourself a break and space for your imagination to flow. Have boundaries but don't choke yourself.

Additional Components/Expanding

Character development, description, and dialogue do not necessarily have to be planned out as stated earlier but keep the main details in mind. Go back to the journal entries, go back to the research and merely expand. How will your story be better with a little tweak? What about this character? Those types of things.

Remember, with every action, there is a reaction. This is very important to consider when drawing up your plot. If you are aiming for a more realistic type of story, make something go wrong. Increase the stakes. Make your character's stakes evident. What are they willing to do? If it can go wrong, it will go wrong, and with writing fiction, there are many possibilities.

So, with all of that being said, you now have your plan! You know what will happen, how it will happen, and some other details too. But now, how will you organize your thoughts? Though some of you may be okay with going back and forth between pages and pages, others may want a bit more structure. Luckily, there are many different, and unique templates and systems that you can use that will fit with your story perfectly. Ranging from the basic Exposition - Denoument to a massive spreadsheet, there are many options to chose from. Simply, select the one that is best for you.

If you are more of a visual thinker, try a flowchart or mind map. If you like detailed, maybe go chapter by chapter. If you fiddle a lot while writing or like to feel things, try making your own storyboard. Not only will you now have a customized planner, but also more motivation to write. (I mean, if you came this far then surely you'd want to finish it?) And that's what it's about. Really making the story matter to you. Yeah, you may have a dozen other projects waiting in line, urging for you to start them but this way, you finally can sort out your priorities. You can finally work.

So, that wraps up planning for now. I've attached some useful links below that can help you further, but if you have any questions, please don't hesitate to ask. I'm always here and ready to help at every step of the way. I hope that I didn't miss anything too important, but if so, I can certainly post them later. Keep an eye out for updates and feel free to interact. With luck, this helped, but for now, it's all. Thank you for reading this far and have a great day!

link number one

number two

number three

four

five

#writing#writers on tumblr#writing advice#improve your writing#writing tips#plot development#plot#plan#planning#planning your story

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

Character Design Lesson

Assignments I’ve found online:

From Cedric’s Blog-O-Rama

Lesson 1: Fat Joe

You are to design a concept sketch of Fat Joe based on the play, The Long Voyage Home. Take it as far as you like. Description: SCENE—The bar of a low dive on the London water front—a squalid, dingy room dimly lighted by kerosene lamps placed in brackets on the walls At the far end of the bar stands Fat Joe, the proprietor, a gross bulk of a man with an enormous stomach. His face is red and bloated, his little piggish eyes being almost concealed by rolls of fat. The thick fingers of his big hands are loaded with cheap rings and a gold watch chain of cable-like proportions stretches across his checked waistcoat.

Lesson 2: Silhouettes

Our assignment was to take Dr. Jeckyll and Mr. Hyde, and fill a page with little thumbnail silhouettes. We were told to play with shapes, trying to find a simple and clear design for the character. The good thing about doing fast little thumbnails is it forces you to think in broad, general terms and not get hung up on the details. When you are just concerned with the overall shape, your thought process can flow and brainstorm. The goal isn’t to do terrific sketches, its to get a lot of ideas onto the paper so that later you can develop the best ones. It’s a great exercise and I highly recommend it. In the future I hope to make it part of my process when designing characters for clients projects.

Lesson 3: Portrait Study

We were given photos of four different men. First, we had to do a straight-forward sketch of the person, not really pushing the shapes or getting too cartoony. Just do a standard portrait. Then, after finishing the portrait sketch, immediately put it away and get rid of the photo. From memory, draw the person again using three different shapes: a circle, a square, and a triangle.

The goal was not to do a dead-on likeness and squeeze it into the shape, because that would be almost impossible. Rather, we were to take the features that defined that person (i.e. eyes wide apart, big chin, small pointy nose, whatever) and play with those features within the shapes to create three new characters.

Lesson 4: Jekyll and Hyde

Last week we were told to choose one of two stories (Dr. Jeckyll and Mr. Hyde, or Oliver Twist), and start thinking about designs for the main characters. Our first step was to fill up at least one page with thumbnail silhouettes of possible designs, thinking about what we could say about the character with just the overall shape. Stephen then critiqued our thumbnails and told us which ones were the strongest. As the course progresses, we will continue to develop our character(s).

Lesson 5: Hand-y Drawing Exercise

Part 1 was to sketch a page of hands.

Next to the face, the hands are the most expressive part of the body, and therefore one of the most important features in any drawing. Its easy to get lazy with the hands, because they can be so stinkin’ hard to draw. I think there are two reasons so many artists struggle:

1. Hands are incredibly complex. I think there’s something like 27 bones in the hand and 15 joints, not to mention all the little muscles, tendons, etc.

2. Hands are always moving, and they can move a zillion different ways. There is no “standard” hand pose.

Stephen spent a significant portion of his video lecture analyzing the hand and pointing out how to break it down into manageable parts to make it easier to draw. Then he told us to go draw a page of hands, using either our own hands or photos for reference.

Lesson 6: Jekyll and Hyde Clean-Up

Our assignment was to choose one design from our “Jeckyll and Hyde” work and ink it up. Inking is not my strong point, especially digital inking on the Cintiq. The Cintiq is superbly fabulous and awesome….except when it comes to inking. I just can’t seem to get the same line quality that I could on paper, which makes my lines look even more mediocre than they normally would be. Maybe I just need to practice it more.

As part of the class, Stephen gives each student one-on-one feedback on their assignments via internet video. Here’s some pointers he’s given me on my assignments, which I tried to incorporate into this final design:

• Watch out for “parallels” (lines and/or shapes in the design that run parallel to each other).

• Push your shapes more. Use more extreme angles, greater size contrasts, broader curves, etc.

• Work on thinking through the understructure of the drawing (especially in your legs and hands). Don’t just use blobby shapes, make sure there is a real skeleton with real muscles underneath.

• Keep your sizes/proportions consistent (i.e. both hands the same size, both arms the same length, etc.)

• Let your design “breathe”. Pull your arms and legs out and away from the body for clearer poses. Spread out your facial features more (I tend to bunch them up a bit).

Lesson 7: Turnarounds

This week’s assignment was to do rough turnarounds of our character.

In animation, once a character design is approved the next step is to create “turnaround” drawings. The purpose is to make sure the storybaord artists, animators, and/or computer modellers can re-create the character accurately. Turnarounds are a tedious but essential part of any character designer’s job. For major characters, there are generally four to five drawings that need to be done: Front View, 3/4 Front View, Side View, 3/4 Back View, and/or Back View. For minor characters, usually only a Front 3/4 View and a Back 3/4 View are needed.

Turnarounds can be quite challenging. It’s relatively easy to do just one drawing of a character. But drawing the same character from other angles can complicate things. The most common difficulty for the artist is making sure that the character looks appealing and consistent from all angles. Easier said than done.

Turnarounds will also reveal any flaws or weakneses in the design. You may sketch a character that looks great from the side view, but draw him again from the front view and he may suddenly flatten out and get boring.

A good designer must also think about functionality. In animation a character can have crazy proportions, but he/she must still be able to act expressively and perform common tasks. For example, did you know Charlie Brown can only touch his nose if you look at him from the front? If you look at him from the side, his arms are too short to reach around his big head.

The best way to do turnarounds is to start with a 3/4 view and then spin him around in your mind to get the other views.

Lesson 8: Attitudes and Expressions

This week’s lesson was all about model sheets, specifically attitudes and expressions.

A “model sheet” is a page of drawings that animators and storyboard artists will use as a guide when animating a character. A good model sheet will give a sense of both the personality of the character (i.e. how does he react to certain situations?) and the physicality of the character (i.e. how does he walk, move, etc.).

Our assignment was to create a model sheet for our character, consisting of two parts:

1. Six standard expressions (anger, surprise, sadness, happiness, fear, and disgust);

2. Two full-body attitude drawings, which could be whatever we wanted. The only rule was that they give a sense of the character’s personality and/or response to a given situation. I chose to depict Dr. Jeckyll before and after drinking the potion that transforms him into a big, ugly, hulking monster.

Lesson 9: The Importance of Sketchbooks

We had to go to a busy public place and fill a page with observational sketches. The Mall of America is near my house, so I went there to sketch the above page.

I can’t over-emphasize the importance of keeping a daily sketchbook. The only way to get better at drawing is to draw. As Stephen likes to say, “A page a day keeps the competition away”.

A sketchbook isn’t for polished drawings. Rather, it’s a private place where you can stay loose, experiment, stretch yourself, and make mistakes. Lots of them! (Mistakes are the best teachers). If you want to keep growing as an artist, the worst thing you can do is fill your sketchbook with things you already know how to draw.

Going to a busy place to draw real live people is something you should do regularly. (Stephen fills a page every day over his lunch hour). Most people don’t sit still for very long, so it forces you to stay loose, think fast and make bold decisions, which over time will increase your confidence. Don’t sweat the details; focus on the essence of a pose (which can usually be captured in just a few lines). Try to capture the overall physical attitude of the person, which is the foundation that breathes life into a drawing. You can always go back and flesh out the details later.

In his lecture, Stephen talked about what a character designer should focus on as he sketches the people around him (i.e. balance, gesture, line of action, negative space, rhythm, attitude, etc.) He also talked about not just seeing, but studying what you draw. Observe the different ways people walk, talk, and gesture. Notice body types, hairstyles, and clothing choices. Study how fabric clings and hangs around the body, how people position their legs when they sit, how they lean when they carry things, how their posture changes with their attitude (i.e. excited, bored, annoyed, etc.) These are the things that give your drawings personality and character.

Stephen also talked about “frankensteining”, that is, assembling parts of several people into one character. You might start to draw a man reading the paper, but as soon as you rough in his body pose he gets up to leave. Don’t abandon your drawing. Add the profile from another person, maybe the hair from a third person, etc. Frankensteining keeps you from getting frustrted when your models keep moving (or leaving) in mid-drawing, and you might be pleasantly surprised at the new character you’ve created.

The point is that you keep drawing, keep experimenting, keep learning.

Lesson 10: Memory Sketching

“Memory sketching” is an exercise designed to strengthen your observation muscles. It works like this:

Go to a place where there are a lot of people (i.e. a mall, airport, coffee shop, etc.). Choose someone in the crowd to draw. Before you pick up your pencil, spend a few moments studying everything about them (their clothing, their posture, their face, the way they do their hair, their height….everything). Don’t look at them for longer than one or two minutes. If they haven’t walked away by then, turn and face the other direction.

Now, close your eyes and continue to study them in your mind. Analyze as much as you can remember. What was that hairstyle again? How far apart were the eyes? What color were the shoes? What was with that funny walk? (Don’t peek. It will completely destroy the purpose of the exercise.)

Finally, when you’ve got your target burned into your brain and you’ve thought everything through, THEN pick up your pencil to draw. And again, no peeking.

Lesson 11: Fat Joe

Our very first assignment was to design a character based on Fat Joe from the play The Long Voyage Home. We were given this description:

SCENE—The bar of a low dive on the London water front—a squalid, dingy room dimly lighted by kerosene lamps placed in brackets on the walls At the far end of the bar stands Fat Joe, the proprietor, a gross bulk of a man with an enormous stomach. His face is red and bloated, his little piggish eyes being almost concealed by rolls of fat. The thick fingers of his big hands are loaded with cheap rings and a gold watch chain of cable-like proportions stretches across his checked waistcoat.

Now, nine weeks later, we were asked to return to that assignment and do it again, this time with clean-up and color. Since this was our last class, it was a chance to apply everything we’d learned.

0 notes

Text

Create storyboards for your animations

Rachel Nabors will give a talk about the web in motion at Generate San Francisco on 9 June, which will also feature presentation by Steve Souders, Stephanie Rewis, Aaron Gustafson, Josh Brewer and 9 other great speakers. Get your ticket today.

These days, we’re all used to seeing show-stopping animated and 3D movies. Technology has come a long way in recent decades, but, to this day, some parts of animation production remains unchanged.

Let’s go back to the first time anyone had attempted to create a feature-length animated film. The cosy team dynamics that worked so well for creating Mickey Mouse shorts would not scale for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. The Walt Disney Studios needed a way to coordinate many teams in order to tackle the massive undertaking.

It was a simple idea: dissect the story into its component scenes, illustrate them roughly on paper or cards, pin those cards on large cork boards, then distribute those boards to the teams every morning. The story department could steer the project, and the production artists would never be able to wander too far down any dead ends.

Storyboards brought what we now call agile development to studio animation. Since Snow White, they’ve become a production staple of film, interaction design and game design. Now, with animation entering the toolsets of web designers and developers everywhere, it seems that storyboards might become this industry’s new best friend, too.

Storyboards help map out sequences of animation

Storyboards for the web

When it comes to animating user interfaces on a project, communication between designers and developers tends to break down if they aren’t working side by side. In companies where animation deliverables are ‘thrown over the fence’ to developers, sometimes designs are handed down as animated GIFs or videos with little else to guide the developers when recreating them.

Storyboards can help designers and developers communicate this very visual topic using its lowest common denominators: words and pictures. They require very little training to make and read, and you can create and edit them without the need for specialised software.

Storyboards are great for sketching out quick UI animation ideas during a team meeting and gathering immediate feedback. For rapid prototyping teams, wireframes can be a great way to document the patterns used, so successful patterns can be applied consistently as the project continues. And as design artefacts, they fit perfectly with style guides and design systems for documenting reusable animation patterns.

Don’t miss Rachel Nabors’ talk about the web in motion at Generate San Francisco on 9 June

A perfect match

On their own, wireframes can help break down communication barriers between developers and designers by giving them a common, collaborative medium. But they are even more powerful when coupled with video and prototypes.

Often motion designers create and polish animations in a program that’s not designed for web development, like After Effects or Keynote. Indeed, it makes sense to experiment with animations using visual tools. But alone, video is a poor deliverable for developers. A developer might spend hours trying to recreate a subtle bounce effect that could have taken seconds if they had only known the easing value used by the designer in their animation program.

Delivering storyboards alongside videos lets developers know exactly what steps to follow to recreate an animation. This is less intimidating than having to make many inferences (which might also frustrate their coworkers). The difference between a cubic and quintic curve is nigh-on impossible for a harried developer to spot in a 500 millisecond GIF. But for a sharp-eyed designer, the difference in production is glaring.

The storyboarding process

Modern storyboards at the office are quite a bit smaller than the large corkboards of the 1930s; they look more like a comic book page than a billboard. Just like a comic page, each panel illustrates and details a different snapshot in time. Underneath each panel is text detailing what’s happening, how and why.

In web design, each of those panels could contain a screenshot, a wireframe, even a sketched microinteraction, supported by notes expanding on what interactions trigger the animations, and over what period of time they occur.

Two panels illustrate cause and effect. Words and illustrations are colour-coded to draw strong relationships

Storyboards can be as macro or as micro, as polished or as rough, as you please. Do what makes sense for you and your team. I have created storyboards with index cards, Photoshop, and even Keynote. It’s important to pick tools that everyone on your team can use and read. Often that ends up being pencils and paper!

For UI animation, storyboarding should start alongside wireframing; right after user research and information architecture. If your workflow is more vigorous, you might start storyboarding alongside design. As long as you’re thinking about animation early, you will be in good shape.

Code your colours

In addition to the black and grey of wireframing, storyboarding benefits from reserving two special colours to indicate action and animation. I use blue and orange respectively, partly because they are discernible for people with various kinds of colour blindness. Blue subconsciously registers as an actionable ‘link’ colour, and orange is very active and stands out. Use these colours to indicate what user interactions cause which things to animate.

Get those digits

A picture is worth a thousand words, but in animation the right numbers can be worth even more. Be sure to include the duration of each part of the animation. Even adverbs like ‘quickly’ or ‘slowly’ will help paint a mental picture for those that need to implement the animations.

Spell out what properties are being changed: from colour and opacity to width or height. Use descriptive words like fade, shrink, slide, expand. Phrases like pop, bounce and swoosh have more subjective values, often affecting more than one property. Does a ‘pop’ involve expansion and contraction as well as a rise and fall? Save these words for naming your animation patterns once they emerge.

Stipulate the animation’s exact easing. This value is supremely helpful to the people implementing the storyboard later on.

Number Each Panel

Numbering a storyboard’s panels is a best practice sometimes discarded by cinema, but invaluable in web design. Starting from 1, they tell readers which way the action flows. Storyboards could come in vertical or horizontal layouts, and numbers quickly reinforce which mental model everyone should be using. Numbered panels allow quick feedback (for example, ‘What about instead of panel 16, we use a nice fade?’), and let you index what animations and interactions happen and reference them accordingly.

Additionally, numerical panels let you add branching logic to your interactions or show several alternatives. For example, you could group several options for the fourth panel under 4a, 4b, 4c.

Use your words!

When adding notes to your storyboard, always detail why the animation is happening. Be sure you can justify the animation with sound reason. You may have to defend the animation to others, and if you can’t explain why it’s important to yourself, perhaps it’s unnecessary for your users.

In my A List Apart post Animation at Work, I list six different ways you can use animation to underscore relationships and hierarchy. Can you use two of these words to explain your animation?

Storyboard Checklist

Each panel (or pair of panels for complex interactions) of your storyboard should demonstrate the following:

What event or user interaction causes which things to animate

How said things animate

Why the animation improves the interaction

Often this breaks down into two panels:

A clear indication of the trigger for the animations (‘When the user clicks the button…’)

A description of the changes that follow (‘…the button fades away to reveal…’)

Colour-code your words, too, with interaction words (like clicked, hover and focus) being underlined or written in your designated interaction colour, and descriptive works (shrink, bounce, fade) using your animation colour.

Bringing storyboards to work

The most common challenge we face when bringing animation to our projects is building a strong rapport with the people who design or code them. The second most common challenge is not standardising those animations we do implement. Both of these lead to inconsistent animation that gives our creations a sloppy, half-finished feel.

Storyboards address both of these challenges: communication and documentation. As such, they are powerful not just for their technical depth, but also for their ability to bring people closer together on a project. This is the spirit in which we must embrace storyboards: not as a tool to dictate but as a conversation to join.

This article was originally published in issue 276 (February 2016) of net magazine.

If you can’t catch Rachel Nabors at Generate San Francisco on 9 June, there’s also a conference in London, which will see a rare appearance of top web animator Chris Gannon. Early bird tickets are on sale now.

This post comes from the RSS feed of CreativeBlog, you can find more here!

The post Create storyboards for your animations appeared first on Brenda Gilliam.

from Brenda Gilliam http://brendagilliam.com/create-storyboards-for-your-animations/

0 notes

Text

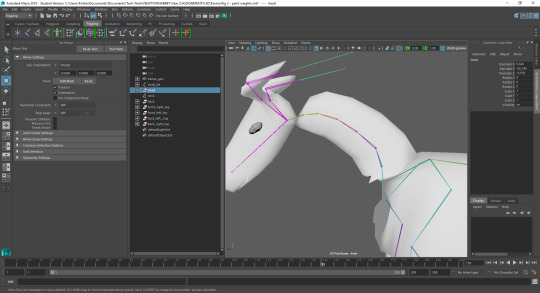

Task 2: Assignment - Doe

Upon reading the brief for this assignment, I already knew what my idea was going to be from the beginning. I wanted to create a deer, a doe to be more specific, gallivanting around a forest as it would in real life. From my storyboard below, I had planned to have my doe emerge from a forest to sniff some treats in a bush, but will look up startled upon hearing moving in the forest. After a period of silence, she would go back to foraging, but the noise would return, and she would gallop away.

The purpose of creating this animation was to learn how to accurately create, rig, and add controls to a quadruped model for animating, all of which I had no previous experience or knowledge in before this. By learning these techniques, I would gain a better understanding as to how an animation is created, and would make it possible to use those methods when creating other animations in the future.

In order to create my deer, I had to research some tutorials that would show me a simple way to model a quadruped. Unfortunately, I couldn’t find any material relating the deer in the slightest, so I had to make use of tutorials about creating domestic quadrupeds such as cats and dogs, while also using reference images of deer I found online to help me create my model. A bank of reference images, along with the main tutorial I used is displayed below.

vimeo

Creating the Scene

I knew I wanted a low poly style scene, as my main focus was the deer itself and it wasn’t possible to create a large, realistic environment given the time constraints. To start with, I made a plane for the grass and created a basic pine tree using a combination of cylinders and boxes. The boxes were changed to Editable Polys to move the vertices into the correct shape for each branch layer. I imported my doe model to use as a size guide, so I could compare the tree to that model and make the tree a realistic height.

For lighting, I added a Daylight to the scene. By adjusting the light’s position, it will create realistic lighting based on it. For example, if the light is high and straight above the scene, it’ll give off shadows and lighting that occurs at noon. Move the light lower to the ground off to left or right and lighting and shadows will resemble those in a sunset afternoon. In the image above, you can see the horizon line where the sky ends is a bit higher than the scene.

Sunlight, mental ray, options

Rendering tab, environments, change to mr Physical sky.

To hide the horizon point and to make the landscape less flat, I created several Geo-spheres, changed their sizes to be completely different from each other, and positioned them as I’ve done in the image above. Through the material editor, I assigned four different shades of green to each geosphere, so the environment appears to more vast than what it actually is. By adding these hills, it gives the the atmosphere more depth to it. As hills aren’t perfectly rounded, I assigned Noise modifiers to all geospheres, cranking up the width, length and scale to give them a bumpy, more natural surface.

Texturing

The next step was placing a texture on the doe. Although I have previous experience of texturing an organic model, I followed a tutorial to brush up on the basics of it. (mention tutorial).

A big problem I had when unwrapping the texture of the doe was connecting the seams for each section, particularly the ears and mouth. I didn’t realise that when making the ears and mouth that I was positioning the vertices in the MeshSmooth modifier instead of the Editable Poly, which meant that the vertices in that modifier were scattered around the mesh. This issue made it very difficult to find the correct vertices for that particular seam. To fix this, I had to locate the vertices within the mesh while in the Editable Poly, and arrange them in a manner that could be clearly noticed while maintaining the same basic shape of the ear.

It was tricky creating seams around the doe’s ears as the vertices in the Editable Poly were difficult to pinpoint. So, I had to go back into the Edit Poly, pick out the vertices hidden within the mesh and position them back into the shape of ears again before creating the ear seams.

After every section was mapped out properly, I saved out the UV map to be sent to Photoshop to apply the texture.

I found a short fur texture at roughly 10MP in size to replicate the deer’s fur. To cover all the UVs without stretching the texture, I duplicated the texture that I turned into a Smart Object, duplicated it several times, and positioned them underneath the UV layer, as I’ve done above. With the same texture piled up several times, it left a lot of harsh, dark lines across the UV from the images borders. To get rid of these, I used a scatter brush with altered settings to make it look similarly to fur, and carefully painted over all harsh lines in a (layer mask) I added to some of the fur layers. I used the same technique for all the other UVs. I saved out all the UVs and PNGs, placed them into the material editor and assigned it to the model. This took a few tries at adjusting UVs in the UV editor, and repainting the texture to get it to fit just right.

Rigging

To rig my deer, the first thing to do is to build a skeleton the model can use to move its body around, just like real living things do. For this, I researched diagrams of deer skeletons as reference material to get a clear reading on how a deer skeleton works.

In the Animation tab, I used the Joint tool to recreate the deer skeleton, placing the joints according to the diagram. I also added a few extra joints for the ears so that they can be told to twitch and move just like they would in real life.

Joints (find diagram).

The next phase requires creating IK handles. IK handles (find what they do). For the front leg, I create an IK handle for the entire leg, which allows the joints to move forward and backward like an actual leg, but that was all it could do. I also made IKs to allow the knee to bend, and for the hoof and ankle to curl behind the leg like it would when it’s walking. Although everything has the flexibility to move, the ankle and hoof do not curl in the direction they’re supposed to, but that can be fixed once the controls are added later on.

A big problem that I had was that I was unsure of how to go about creating the joints for the neck, face and ears for the deer, so I had intended to add IK handles to the rest of the body, come back at a later stage and connect the neck to the body. However, the neck joint will only connect to another joint that has not been converted to an IK handle, meaning I had to go back and connect all the joints of the skeleton before going back into creating the IK handles.

Painting Weights

After binding the rigged skeleton to the mesh, some of the geometry became a bit warped when parts of the body were moved, such as the belly stretching abnormally when moving around the deer’s limbs. Another more major problem was that when bending the deer’s neck downward as it would naturally, the mesh would twist and warp into itself around the base of the neck and beneath the head. In order to fix this problem, I had to adjust both the rotate and position pivots for both joints until they became relatively untwisted. I painted weights around both the base and the height of the neck to stop it twisting inwards again.

Controls

Adding controls aren’t always necessary, but I decided to add these as, due to the size of the joints of my deer model, it would make selecting to animate later on much more difficult. These controls would make it easier for me to select the part of the body I want to move, and animate it accordingly.

I used basic circles for each control, making them slightly bigger than the body part it’s assigned to so I can see it clearer to the eye and easier to grab. To actually connect these controls to the IK handles, I snapped the pivots of each IK to the area where the most movement would be, and then snapped the pivots of the controls to that same IK. If I hadn’t fixed the pivots, my rigged movements would’nt move the way it should. For example, if the pivot for bending the knee was not in fact in the knee, then the knee would contort very badly and unnaturally.

Exporting

Exporting was a bit of an issue. Due to Maya not having Mental Ray, a renderer I need to render out my animation with, I had to export my animation back into 3DS Max again. By doing this, I had to re-adjust object sizes, recreate small objects within the scene such as the bushes due to 3Ds not recognising the shape, and I also had to add new materials to every low poly object except the geospheres and the deer, due to them being listed as lamberts from Maya, which 3Ds Max do not support.

Animation

Animating was tricky, considering all the parts of the doe’s body I wanted to move. I had made an error throughout the course of the animation process that I hadn’t noticed until late. Somewhere along the way, I must have forgotten to freeze transformations on all controls and parts of the deer, as when I wanted to reset a limb to its neutral position at 0, it would not look as it was supposed to, and therefore I had to copy and paste numbers all over the place to make sure the animation was smooth. Also, I hadn’t realised that at the beginning of the deer’s walk cycle, the belly jumps out unnaturally at times and makes the legs appear to be popping out of their sockets at times. As I had only noticed this issue at the very end of the animation process, it was too risky to dive in and fix it when I had already animated everything else.

Rendering

The rendering was the final step. By using mental ray, and by allowing it to use the Ambient Occlusion settings, each frame was rendered twice. One frame had the entire scene rendered within it with some shadows, while the other image of the exact same frame would be in black and white except for some darker shading in parts of the body. By rendering it out this way, I would be able to bring both renders into After Effects, compile the two, and the shows in the scene would pop out much more, looking more natural.

youtube

2. Guitar

To create the main part of the body, I created a Line from the Spline menu, and used it to draw the shape. After closing the Spline and re-positioning the vertices to give the body curvature, I (did something here), extruded top face, and capped the back of the body to make it more 3D.

Creating the neck involved a bit more work. I created a new box and converted the object to an Editable Poly to move the vertices into the correct positions. To get the right shape for the head of the guitar, I extruded out the neck a few times and positioned the new vertices according to the reference. The trickiest part was the curved wood at the back of the neck, which involved extruding out two of the polygons at the bottom of the neck, and chamfering the connecting edges down the spine of the object to a high enough value. The final touch was to have the head of the guitar slanted at an angle like in the reference material, which I did by simply selecting all the faces of the head and rotating X axis.

Creating the string tuners on the back of the guitar head required making a number of objects and combining them together. The base of the Tuner was made from a simple box, and converted it into an Editable Poly to arrange the vertices in a flatter, rhombus shape. On top of the rhombus, I placed another box, connecting two of the edges of it’s top face and lifting the new edge to create the raised surface from the reference material. For the parts that actually do the tuning when twisted, I created a basic cylinder coming from one side of the box with the raised surface, brought down the length segments of the shape to (12/8), and removed all segments along the width of the cylinder to create a clean circular face. To get the intricate shape required a series of extrusions and adjusting vertices of each segment. The final part was made from a simple box with (2) segment(s) on each face, converted to an Editable Poly and squashed the other vertices. With the complete tuner, the entire thing was duplicated five more times and positioned on back of the guitar head like the original.

Each guitar string was made from cylinders sized in accordance with the actual size of the strings from the reference material. All were extruded out, bent to follow the shape of the guitar head, and individually twisted around its corresponding tuner.

Bibliography

Photography-on-the.net, 14 October 2012. A Deer, A Doe [online]. Available from: http://photography-on-the.net/forum/showthread.php?t=1237945 [cited 21 November 2016].

Deviantart.com, [online]. Available from: http://daftopia.deviantart.com/art/Deer-Doe-Stock-Images-336745089 [cited 21 November 2016].

Stiltner, Charliece, 19 August, 2010. Female Deer Running 2 [online]. Available from: https://www.flickr.com/photos/shinesindarkness/4911365657 [cited 21 November 2016].

0 notes