#and red wing black bird on a cattail of course

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

i NEED my redwingblackbird tattoo

#when i get money its so over#personal#i think i want it paired with a crow or maybe a flicker#crow on a red cedar#and red wing black bird on a cattail of course

0 notes

Text

CRITTERS I FUCKING LOVE:

*Monarch Butterflies (one of my elementary school teachers in Iowa had a monarch farm and would bring buckets to school and let them go in the classroom!!)

*Blue Morpho Butterflies

*Luna Moths

*Rolly Pollies

*ALL beetles

*Praying Mantis

*Cicadas

*Katydids

*Crickets (my special talent was taught to me by a cricket... I can chirp just like one!!)

*Carpenter/Leaf Cutter Ants

*Jumping Spiders

*Banana Spiders (although its utterly terrifying to walk into an occupied web on accident!!!!)

*Water Skippers

*ALL frogs and toads

*Walking Sticks

*Inch Worms

*ALL Birds of Paradise

*Red Winged Black Birds (fond memories of watching them in the cattails in Iowa)

*Ravens and Crows

*Grackles (hilarious and ornry fuckers)

*Redtailed Hawks

*Barn Owls

*Screech Owls

*Tawny Frogmouths

*Penguins!

*Fiddler Crabs (had one as a child and it ate all my mom's angelfish. I still loves him.)

*Peacock Mantis Shrimp (the crazy eyeball moving beautiful shrimpy shrimp!)

*ALL Jellyfish (doesn't matter that I got stung by a bed of Jellyfish while I was a little girl in Mississippi. That's what made me love them more!!)

*Whales (they are old souls full of all the wisdom in the universe)

*Snow/Cloud/Amur Leopards (I did my conservation biology final on Amur Leopards because I libe them so fucking much!!!)

*Skinks (I used to walk my 3 mile driveway to the bus stop in Colorado and pick through the rocks to find skinks and horned lizards to put into my backpack to take to school and have them bite my finger while I chased my classmates around waving them while they held on)

*Otters

*Ferrets (one of my 5th grade teachers in Colorado had a white ferret in the classroom that he'd let out everyday, and it would pilfer everything and I fucking loved it!!!)

*Dapple Grey/Paint/Appaloosa/Palameno/Friesian Horses (got a floating rib from training horses and most of my toes were broken by the giant babies, but I still fucking love them!!)

*Mountain Gorillas (their eyes hold the universe in them)

*Bats (nothing like having bats regularly attend elementary school with you in New Mexico!!!!)

*Bees (I used to catch them bare handed from the flowering trees and put them into bottles to innocently give to my mom who was deathly allergic to them. Then in Texas my bro thought it hilarious to put a pot over a ground bee nest, call me over, then kick the pot over before running away to leave me to get stung by them. Still love them!)

.... And of course, all domestic/slightly domestic cats, LOLOLOL!! Mine is a demon dragon pygmy-leopard after all!!! LMAO!!!

CRITTERS I FUCKING HATE:

*Annoying-Ass Sand Pipers (aka Killdeer... It depends on where you live for what they call that fucker. I've lived everywhere, but I call it a Sand Piper.) I always scream at it, LMAO! I don't care how crazy I look!

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The red-winged blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus) is a passerine bird of the family Icteridae found in most of North America and much of Central America. Claims have been made that it is the most abundant living land bird in North America, as bird-counting censuses of wintering red-winged blackbirds sometimes show that loose flocks can number in excess of a million birds per flock and the full number of breeding pairs across North and Central America may exceed 250 million in peak years. It also ranks among the best-studied wild bird species in the world. The red-winged blackbird is sexually dimorphic; the male is all black with a red shoulder and yellow wing bar, while the female is a nondescript dark brown. Despite the similar names, the red-winged blackbird is in a different family from the European redwing and the Old World common blackbird, which are thrushes (Turdidae).

The common name for the red-winged blackbird is taken from the mainly black adult male's distinctive red shoulder patches, or epaulets, which are visible when the bird is flying or displaying. At rest, the male also shows a pale yellow wingbar. The female is blackish-brown and paler below. The males of the bicolored subspecies lack the yellow wing patch of the nominate race, and the females are much darker than the female nominate.Young birds resemble the female, but are paler below and have buff feather fringes. Both sexes have a sharply pointed bill. The tail is of medium length and is rounded. The eyes, bill, and feet are all black. The female is smaller than the male, at 6.7–7.1 inches long and weighing 41.5 g, against his length of 8.7–9.4 inches and weight of 64 g.

The range of the red-winged blackbird stretches from southern Alaska to the Yucatan peninsula in the south, and from the western coast of North America to the east coast of the continent. Red-winged blackbirds in the northern reaches of the range are migratory, spending winters in the southern United States and Central America. Migration begins in September or October, but occasionally as early as August. In western and Central America, populations are generally non-migratory.

The red-winged blackbird inhabits open grassy areas. It generally prefers wetlands, and inhabits both freshwater and saltwater marshes, particularly if cattail is present. It is also found in dry upland areas, where it inhabits meadows, prairies, and old fields. The red-winged blackbird is omnivorous. It feeds primarily on plant materials, including seeds from weeds and waste grain such as corn and rice, but about a quarter of its diet consists of insects and other small animals, and considerably more so during breeding season.

The red-winged blackbird nests in loose colonies. The nest is built in cattails, rushes, grasses, sedge, or in alder or willow bushes. The nest is constructed entirely by the female over the course of three to six days. It is a basket of grasses, sedge, and mosses, lined with mud, and bound to surrounding grasses or branches. It is located 3.0 in to 14 ft above water.

Red-winged blackbirds are polygynous, with territorial males defending up to 10 females. However, females frequently copulate with males other than their social mate and often lay clutches of mixed paternity. Pairs raise two or three clutches per season, in a new nest for each clutch. A clutch consists of three or four, rarely five, eggs. Eggs are pale bluish green, marked with brown, purple, and/or black, with most markings around the larger end of the egg. These are incubated by the female alone, and hatch in 11 to 12 days. Red-winged blackbirds are hatched blind and naked, but are ready to leave the nest 11 to 14 days after hatching.

Since nest predation is common, several adaptations have evolved in this species. Group nesting is one such trait which reduces the risk of individual predation by increasing the number of alert parents. Nesting over water reduces the likelihood of predation, as do alarm calls. Nests, in particular, offer a strategic advantage over predators in that they are often well concealed in thick, waterside reeds and positioned at a height of one to two meters. Males often act as sentinels, employing a variety of calls to denote the kind and severity of danger. Mobbing, especially by males, is also used to scare off unwanted predators, although mobbing often targets large animals and man-made devices by mistake.

322 notes

·

View notes

Photo

No Works and No Days (Part 1)

“Love me a good mystery! Tra-la-la!”

The toy soldier advanced forward, climbing over a cake of burned out Pal-Mals, layered with a crust of ash at the top.

“No one can stop me now! I am at the top! And the New York Ripper will soon be in my gr…”

“AHAH!”

Another toy soldier landed from the sky, his spruce green face crudely washed over with pigments of white. Black circles enveloped his eyes and red paint was smudged round his lips.

“No, my dearest Marlowe! The world belongs to me! You better Hyde up or play dead! Not even the devil himself, can save you now!”

“Damn you Hyde! Run back into the gutter where you dragged your stinking ass from! Pew! Pew!”

A third soldier figure arose from behind the ashen pile. Threads of black cloth had been crudely sewn round his torso, ending in a double tail meant to resemble a 19th century frock.

“Time for you both to face the Music! Your Meister has arrived! Your pathetic strife shall serve as fine material for my new sonata! Ha-hah-hah-hah! John Martin, you are nothing but a hack! As for you detective, I shall strike you on the back! KABANG!”

Ding-Ding!

Marlowe dropped his toys and rushed to the microwave. White fumes and the scent of crackling meats met his nostrils, as he dragged out what some may called a club-sandwich but what most cardiologists would call the back road to an early grave.

Six slices of bread, the first filled with bacon and cheddar cheese, the second with barbeque sauce and potato fritters, the third with tomato, pork sausage and ketchup, the fourth with mayo and chicken nuggets, the fifth with beef and sour sauce and the sixth with grated parmesan and two fried eggs. A gruesome pile of carbohydrates and animal fat, self-humorously named by and after its inventor.

The Marlowe Sub. Also known as the shortest possible route to the emergency room.

With that monstrosity in hand, Marlowe hauled his newly acquired twenty-pound-extra beer-belly to the dining table, where he rested on a night-sky themed chair, made in 1924 as a gift from Clara Winter, to her son Robert, a few months before she perished from pneumonia. Marlowe, had spent the last two years of his life in the Winter manor, first setting in the Fall of 2018, when he attended the funeral of Christopher Winter’s housekeeper, James Krumphau.

James was diagnosed with liver cancer the previous year but kept it a secret from everyone he knew, including Marlowe. Yet again the people James knew count scarcely be counted in the fingers of two hands. James was never exactly the socialite, having spent half of his life serving the Winter family and the other half, being Christopher’s right hand man during his Music Meister years.

The housekeeper was always nice to him, albeit a little distant. Marlowe had garnered suspicions, that there were certain dark spots in James’ private history, albeit he paid no regard to them for long. After all, since his 2012 brush with Martin and the Black Glove, the classic detective novel mystery of “Who’s the criminal” had been reversed into “Who isn’t?”.

Even if James had claimed his literal pound of flesh, by the time they met, he had become one of Marlow’s handful of allies. In retrospect, James was the one to inform him that Christopher had willed him the Manor and half his fortune on that 2013 night that came to be known since as The Storm of the Century. James was also the man, who facilitated Marlowe by providing him with the passwords for all the Winter-family bank accounts and trust funds, including the house in Wilbraham, where Marlowe discovered the existence of the Black Glove and the spawn of their abandoned experiments. In the ensuing years, Marlowe would even receive letters from James once in a blue moon, typed in a code they had pre-agreed upon. James would share a few notes about his routine, but for the most part he inquired on his welfare and progress in rooting out the organization that had destroyed the life of Winter and Marlowe alike. Upon hearing the news in 2018, Marlowe rushed back to Midvintersville, where he made arrangements for James’ inhumation. Marlowe was not surprised to find himself alone during the ceremony, lest for James’ Asian-American nephew Lee, who had apparently visited his uncle a few times during Marlowe’s hunt for the Black Glove. Meanwhile, James had apparently spent his last years in prosaic retirement, tending the Winter manor and its grounds, interrupted only by a short adventure involving a Pleistocene fossil, his nephew had drawn him into. Upon its closure, Lee had gifted his uncle with a Chinese pine Bonsai, that James never failed to prune and water and love as if it was the child he never had.

No tears were shed during the funeral, just a merciless silence occasionally interrupted by the uncanny echoes of the maple leaves dancing in the wind, before collapsing on the freshly mowed cemetery lawn. A single line from Homer’s Iliad was read by the Catholic pastor, before the mahogany casket with James in it, was swallowed by the dirt.

Like the generations of leaves, the lives of mortal men.

In the following day, when Marlowe read James’ will, he couldn’t do otherwise but take a moment to weep for James but maybe more so, for himself. James had bequeathed his share of the Winter fortune to Marlowe and Lee alike, although the Winter Manor was left entirely under Marlowe’s custody. His sole request was for Marlow to care for the tree and be there for Lee should the need arise.

The little pine now rested against the oval window of the Winter Manor’s second floor ballroom. Marlowe would remind himself to water it each day, even when his ruminations became too self-consuming to let him rise from bed, he’d still force himself up to tend the Bonsai before burrowing under the sheets once more. Marlow had even employed the tree in reenacting vignettes from his life, using a vintage toy-soldiers set he had unearthed from the Manor’s old storage, that since 2008 had become the Music Meister’s center of operations. Under its upward pointing branches, lay three soldiers whose faces he had charred against the hearth’s embers and then placed in horizontal position, each marked with the label: Prospero, Driskull, Boisette. Three powerful men who sought immortality, and left mountains of bodies in their efforts to achieve it. And yet the last beheaded the rest and he was in turn penetrated to death by the very man whose cruelty he envied. A much coveted eternity, cut short by the razor-sharp fangs of a monstrous always.

Marlowe often starred at the pine’s, fallen needle-sharp foliage, drying and dying and rotting over the toys representing the inhumane leaders of the Black Glove. And he would often take pleasure in the thought, that his actions, in part, made sure that men like them deserved to have no place on earth, or beneath it.

Like the generations of leaves, the lives of mortal men.

The once detective, now close-to-obesity recluse, however had little clue on how to care for anything living. Youtube channels on botany and gardening tutorials came to be of great help, teaching him the delicate arts of trimming, soil enhancing and of course, the spiritual and medicinal value of plants across human history.

In his early days at Winter manor, Marlowe attempted to dig deeper into plants, immersing himself into books about foraging and gathering as well as the transcendental aspects of the natural world, he found in the pages of Henry Thoreau’s Walden. Marlowe even attempted to conduct Thoreau’s experiment for a while.

In early 2019, he had moved to a tightly-spaced lodge not far from the Manor, where he spent his days, wandering across the forested lands surrounding the property, ensuring the well-being of James’ child as well as the much larger: mountain planes, black spruces, white oaks, balsam firs and the bonsai’s towering cousin, the white pine. His diet consisted solely of wild apples, grains, dried nuts and a variety of fungi, weeds and berries like the newly sprouting cattails he’d heat and serve with dandelion and purslane toppings, and the salty morels he’d sizzle on the campfire with elderberries and meadowsweets. Sumac and dog-rose teas became his daily refreshments, while his wonderings provided daily inspiration in the shape of new discoveries of various shapes, size and species.

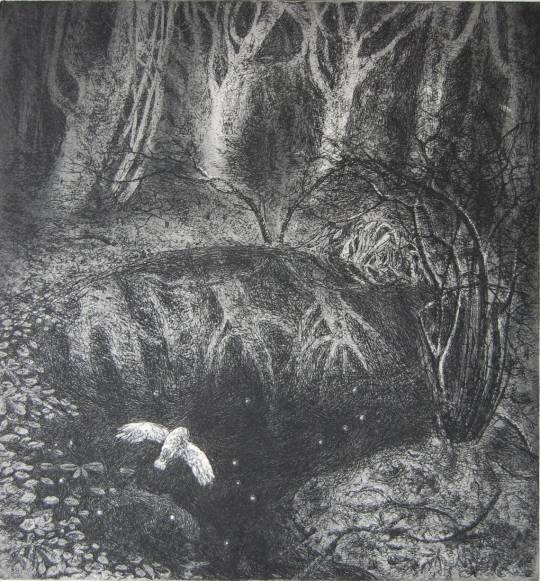

Alien-looking British Soldier lichens, multicolored lady-slippers and processions of various insects and parasites growing out of severed tree stumps were but a few of the curiosities he’d encounter as the woods themselves seemed to come alive throughout spring. Vireos, wobblers, whippoorwills and the occasional grouse, would often surround his lodge for scraps, while in the still of some King’s Country summer nights, a barred owl would descend like a shadow of times long past, a demon-winged silhouette against the silver moon, snatching the avian visitors away from the camp and into scalpel-like talons that promised an one-way trip to the spectral realm. Marlowe witnessed it in full only once, yet he did not fail to see the semblance between the majestic and terrifying grace of the ancient bird and the thing he had seen John Martin transform into, a few years ago.

Reflecting upon that night’s experience, Marlowe started putting bizarre sketches into paper. While finishing the lines of two shadows, facing together at an endless ocean formed of teeth, gloves, hats, scarves and corpse-baring owls, he felt a sharp pain cutting across his stomach. At first, Marlow lifted his flannel shirt, glancing at the ten-centimeter line of still healing flesh, outlining the area below his ribcage. Marlowe gnarled as memories of Stephen Boisette slicing right through him with a double-edged saber, gifting him a scar the size of a pencil, were returning. The Alchemist, the Black Glove’s personal bulldog. The man that framed him for the murder of a girl at Cambridge all those years ago, turning him into England’s scapegoat for a decade. The man who gloated after his mother’s death from cancer. The man that got an inch away from sending him to join her. Now dead, by Martin’s dick and teeth. Served him well.

But the ache returned, stronger now, more penetrative.

His gut began turning ferociously as Marlowe crawled on his knees, pushing himself to and fro against the moss-covered stump of a severed birch.

The last thing he remembered when he woke up in the E.R., was dialing 991 and watching a cauldron of bats with a barred owl, savagely screeching at their tail, breaking away from the canopy and into the evening sky.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Adventure Begins

38.485050, -107.948616

I start this academic adventure close to my home. A little secret I’ve held for just such an occasion. Not far from where I spent some years of my childhood there is an odd little marshy area, several to be more accurate. In the largest is where I encountered my very first arcane creature at only 12 years old. It was so remarkable a discovery it changed the course of my life. I only ever saw the creatures 3 times and then only for a few seconds clearly each time. It wasn’t until I reached Writtle University College for arcane studies that I learned exactly what they were. PIXIES, as one of the most prevalent of lesser arcane creatures(LACs) it is no surprise. Pixies also are one of the most diverse and easily the most seen by the masses. There are many different subtypes of pixie and they are very location specific and adapted. They are often reported as small birds, large bugs and sometimes fireflies. Which is how I came to discover them originally. A school teach informed me there were no fireflies in western Colorado, I exclaimed she was wrong as I had seen them on many occasions. I was a bit strong headed in my youth. After the scolding I became determined to catch a few just to put her off. To say I was surprised is an understatement. I never got close to catching one then and only now realize how different this pod was than standard.

The Red Willow Pixie Kingdom

I have been watching the pods for the last several nights. It seems they are most active in the late afternoon into the early evening. There are three separate but cooperating pods here. Very VERY unusual pixie behavior. The red willow pixies are far more organized than typical pods and instead of the 10-15 in a pod here we are seeing the pods at 33, 53 and 68 as best can be counted. I have observed heavy traffic of more than 100 passings a night between the 3 locations, also a rarely observed trait. These levels are even higher than the accredited kingdom of Plitvice Lake Pixies. I have place 3 observation spheres in the reeds and they have placed a single rotating guard on each! Extraordinary levels of organization for pixies. On the second day of observation the pixies completely obscured the spheres by weaving the broad cattail leaves into a basket around them. And the most surprising event of all happened on the evening of the third night. A single pixie with a small red willow branch in her hand appeared and began dancing around between the basket and the sphere. It took three complete circuits and the sphere popped out of existence. She went one by one to them and did likewise. In my field bag the next day I found a rolled up leaf with what appears to be Sumarian or Hittite written on it. I sent a digital picture of it to a colleague (Prof. Darragin Newhammed)who informed me it will take some study as there is a lot there. However he was able to make a good guess on the larger text. He believes it says “Treaty Breaker go away.” I have done just that. This appears to be at least a level 3 social group and I am no diplomat. I have sent my report and requested they dispatch one at their earliest convenience. This group is near and dear to me so I will keep track of the finds and may comment further on it later.

Each Red Willow Pixie has a pattern of tan and green as skin color and it varies between them and is slightly bumpy like a common lizard. 8cm heigh and an estimated weight of 25-30 grams. The limbs are thin as is the body. The eyes slightly too large to have a human appearance and black with a barely detectable iris that allows greens, blues, and violets to sparkle through depending on the specimen. Each has the red willow coloration starting vein like from the head and into the very dragonfly like wings. The red vein color being most prominent in the wings and is the source of the slight glow in flight. 3 fingers per hand and a thumb. Females are distinctly so with breasts. They all appear to wear lower covering much like a kilt of natural leaves and woven roots.

1 note

·

View note

Link

Mary Oliver and her dog, Perry. Photograph by Rachel Brown.

Editors’ note: This story was originally published in the now-departed SEARCH magazine, in 2008, edited by KtB co-founder Peter Manseau. We thank them for permission to republish.

Each spring I teach a course at Boston University called “Death and Immortality.” My students and I discuss the quest for an elixir of immortality in the Mesopotamian epic of Gilgamesh, and the execution of Socrates in Plato’s Phaedo. I tell them Christian stories about the crucifixion of Jesus and Buddhist stories about the death of the Buddha. Along the way, my students reckon with their own mortality, even as I reckon with mine.

In a final lecture on deathbed proclamations, I talk about the last words attributed to Plato, Jesus, and the Buddha. I also include some more secular examples, such as Conrad Hilton’s “Leave the shower curtain on the inside of the tub.” But I give this lecture’s last words over to the poet Mary Oliver. Oliver, who has just released a new book, The Truro Bear and Other Adventures, is neither a scientist nor a preacher. But like Henry David Thoreau of Transcendentalist fame she is a naturalist whose attention to what used to be called the Book of Nature borders on both devotion and experimentation. Her poems work in my course because they are somehow animated by death, and they work on me because they speak about the mysteries of mortality in a language that feels like home. Perhaps that is because, like Oliver, I live on Cape Cod, so I am familiar with the fiddler crabs, great horned owls, humpback whales, irises, goldenrod, and honeysuckle that populate her poems. I suspect, however, that her poetry vibrates at frequencies close to my own because I share with her something of a Buddhist sensibility, particularly when it comes to an awareness of the transiency of things.

I read different Mary Oliver poems to my students each spring, but I always conclude with “In Blackwater Woods.” This poem begins with one of Oliver’s favorite commandments: “Look.” Next the poet calls our attention to trees and autumn leaves and “the long tapers/ of cattails” and “the blue shoulders/ of the ponds.” Then, as is her wont, she redirects our attention to something broader and more human: in this case, “the black river of loss.” The poem ends with these words:

To live in this world

you must be able

to do three things:

to love what is mortal;

to hold it

against your bones knowing

your own life depends on it; and, when the time comes to let it go, to let it go.

When I started working on this article, I was hoping to talk with Oliver. It’s the 25th anniversary of her Pulitzer Prize-winning collection American Primitive, so I wanted to meet her at sunrise, to trudge with her across the Provincetown dunes, to pay attention to her paying attention to nature. I wanted to ask her what she knows about Buddhism, and what she thinks of it, whether her poetic practice of attention—of looking and listening—is a kind of mindfulness, whether her attention to nature is informed by No-Self, and whether her ability to reckon with loss is rooted in an understanding of Impermanence,

I wanted to talk with her about the parallels between her sort of looking and the looking my biologist friends do through their microscopes. I wanted to understand what she meant when she referred to herself as “spiritually curious,” and to the poem as a “confession of faith.”

Unfortunately, Oliver, who once called privacy “a natural and sensible attribute of paradise,” turns out to be rather reclusive, so I never got to ask her these questions. Apparently she prefers making poems to giving interviews, watching the tides to revealing the ebbs and flows of her own autobiography. “You don’t want to hear the story/ of my life, and anyway/ I don’t want to tell it, I want to listen,” she wrote in 1986. Three years later she told an interviewer that poets should vanish into their writing rather than hover in front of it. “I believe it is invasive of the work when you know too much about the writer, and almost anything is too much,” she said.

After Oliver faxed back my request for an interview with a terse (but not unfriendly) “no,” I briefly considered trying to observe her in her native habitat, traveling to Provincetown to observe her on her morning rounds, not unlike she might observe a great blue heron or some other force of nature. But this strategy sounded too much like stalking to me, perhaps because it was.

I tried to track her down at a poetry reading last summer in Provincetown. We exchanged hellos as she walked in the door, and a goodbye as she left. But she came and went more like a hungry hawk than an established poet, and did not take any questions.

So I decided instead to visit some of the sites in and around Provincetown where Oliver sites her poetry. I decided as well to try to be in the world for a while after the manner of a Mary Oliver poem—to wake early, to look and to listen, to attend to nature, to slow down, to be grateful, to live simply, to love recklessly, to sit with my losses, to take what is given rather than what is desired, to attend to the presence of death in the midst of life, to venture out into storms rather than taking refuge from them.

On a CD I recently received as a gift, “At Blackwater Pond: Mary Oliver Reads Mary Oliver,” is a jewel of a poem called “The Buddha’s Last Instruction.” Here are many of the themes of Oliver’s work: a preoccupation with spirituality, a fascination with death, and a strategy of abiding in the mysteries of both by attending with amazement to the glories of the natural world. The poem begins:

“Make of yourself a light”

said the Buddha,

before he died.

It then jumps to the poet herself, mulling over this last sermon in the presence of the rising sun. The poem then migrates across millennia and continents again—back to Kushinara, the place of the Buddha’s death. There she shows us an old man lying down between two trees, with worlds of possible words before him as he ponders his last words. Then back to the poet and the sun. Then to the old man again, recounting the twists and turns of “his difficult life.” Then back to the poet and the sun and feelings of human inadequacy and human brilliance. And finally back to the Buddha raising his head and readying his lips to say something to a crowd at least as frightened as we are in the presence of the mystery of death. This sounds like a Buddhist poem to me. But is it?

The Catholic theologian Karl Rahner famously referred to believers outside of the Christian tradition as “anonymous Christians” bound for a heaven their religious traditions do not even entertain. There is something generous about this intellectual sleight of hand, which conspires to smuggle Hindus and Muslims, for example, into heaven. But there is something unsettling and even arrogant about it too, since Hindus and Muslims presumably do not want to be Christians, or to abide eternally in the aftereffects of the Christian imagination. I have no interest, therefore, in converting Oliver into a Buddhist against her will. She is, as far as I can determine, a Christian, and far more likely to refer to her poems as “alleluias” than as “meditations.” Her most recent work, moreover, particularly poems crafted since the death of her life partner, Molly Malone Cook, in 2005, evokes an array of explicitly Christian themes, not least God, the soul, loaves and fishes, and resurrection.

Still, she greets many of the standard preoccupations of Christian theology with a shrug (the afterlife, she writes, is a “foolish question”), and her work is salt-and-peppered with references to Buddhism. An owl—one of her favorite subjects—is a “Buddha with wings”; turtles demonstrate “Buddha-like patience”; and a toad sitting implacable and immovable by the side of a path “might have been a Buddha.”

More importantly, mindfulness seems to be Oliver’s métier, looking and listening her scientific method and contemplative practice. “To pay attention, this is our endless and proper work,” she writes. “Attention is the beginning of devotion.” But paying attention is also Oliver’s way of being in the world. It is what she does. She looks. She listens. She attends. “Listen,” this poet of mindfulness writes in “Terns,” “maybe such devotion, in which one holds the world/ in the clasp of attention, isn’t the perfect prayer,/ but it must be close.”

And what this mindful devotion does for Oliver is thrill and amaze her. An Oliver poem called “Mindful” begins like this:

Every day

I see or I hear

something

that more or less

kills me

with delight,

that leaves me

like a needle

in the haystack

of light.

It is what I was born for—

to look, to listen . . .

If Oliver is a poet of mindful attention, she attends particularly mindfully to death. In fact, she attends to death with a clarity equal to any living writer I know. Her poetry seems as exquisitely calibrated as Buddhism itself to the hard realities of loss, which she calls “the great lesson.”

In my “Death and Immortality” class, my students and I explore attitudes toward death in the world’s great religious and philosophical traditions—from Jesus’s hot defiance to the Buddha’s cool acceptance. Oliver lies closer to the founder of Buddhism here than to the founder of Christianity, but more than simply accepting death she seems to embrace it—as the secret ingredient in the recipe of nature and culture alike, the umami that somehow makes this life of suffering sweet with purpose and meaning and even mad love.

My first visit to Mary Oliver’s Provincetown began auspiciously—with the sighting of a red-tailed hawk. As I was driving out Route 6 toward the tip of Cape Cod, I saw a large bird perched in an old oak tree by the edge of a salt marsh. Usually a sighting like this would not stop me short, but on this day the Mary Oliver in me told me to pull over, and so I did. As I walked back toward the tree I tried to determine whether the bird was an owl or a hawk. As if on cue and under direction, it immediately obliged my curiosity by turning its head from side to side, revealing the distinctive profile of a hawk. And when it flew away, flashing a brilliant red tail, I knew what sort of wild animal had visited me.

Farther down the road, I was able to locate what at least one map referred to as Blackwater Pond. On my approach, I was surprised to see that access had been carved out in asphalt—in the form of a large, circular parking lot connecting to a series of clearly-marked walking trails around the pond. And because it was winter, I was also surprised to see dozens of cars in the parking lot. Out on the pond there was little to commend a poem, at least not of the Oliver variety, since her work is notorious for its single-minded focus on plants and animals. “Few poets have fewer human beings in their poems than Mary Oliver,” the poet and novelist Stephen Dobyns once wrote, and Blackwater Pond on this day was thick with children and adults lacing up ice skates and playing hockey or twirling about on clear black ice.

During my own walk that day around and then across Blackwater Pond, I tried to honor my new guru by paying attention. I tried to glory in the natural world and to meditate, as Oliver herself seems perpetually to be doing, on change and death and loss. But I couldn’t help thinking of Thoreau and that pesky fact that he went into town just about every day (for supplies and conviviality) during his much-hyped experiment in so-called solitude at Walden Pond.

Gradually I realized that I had been storing up pictures of Oliver making her own path through virgin woods, cutting herself on the sorts of brambles that cut into me as a boy exploring my own woods on Cape Cod. I realized that in all likelihood she had been dodging joggers and rollerbladers on a bramble-free asphalt bike path while musing over “On Blackwater Pond.” I found myself wondering whether she might even have made her way to this place not by foot (as I had always assumed) but by car, and maybe not in a Prius either. I wanted to know what Oliver the poet would have to say not only about the hawks and owls that populate Blackwater Pond but also about these high-schoolers with their Gatorade bottles and I-pods and hockey sticks. Are they immune, I wondered, from the predatory instincts she finds so frighteningly beautiful in the owl and the red-tailed hawk? From the immortal lusts of the natural world?

As I drove home, I found myself meditating on how death and loss are married to love and abundance in Oliver’s work, but I had a hard time homing in on the familial connection. In some of her writing, Oliver seems to take up the Romantic position that to embrace death is to befriend both truth and beauty. A poem of hers about lilies includes this reflection: “to be beautiful is also to be simple/and brief; is to rise up and be glorious, and then vanish.” A poem called “Peonies” relates the reckless beauty of these flowers, their “eagerness/to be wild and perfect for a moment, before they are/nothing, forever.”

Oliver writes repeatedly and lovingly about dogs, who reside in the limens between nature and culture, the wild and the tame. And she prefers to walk her dog off-leash. So it should not be surprising that her poems about love read like unleashings. Love for her is a sprint from domesticity into the wild, from calculation to abandon. “There isn’t anything in this world but mad love. Not in this world. Not tame love, calm love, mild love, no so-so love. And, of course, no reasonable love.”

One of the claims I explore with my “Death and Immortality” students is that life and love are richer and deeper once you realize that nothing is immortal. “Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon?” Oliver asks. Each of us is “a customer of death coming.” But Oliver’s takeaway is not to hasten to a funeral home (or, for that matter, a nunnery), but to live wildly and love madly, to imitate the peony and the lily in bloom, the dog sprinting off its leash after sea spray and seagulls.

A friend recently introduced me to a prose poem by Oliver that had somehow eluded me. It is now my favorite piece by her, the John 3:16 in my Gospel according to Mary Oliver:

You are young. So you know everything. You leap

into the boat and begin rowing. But listen to me.

Without fanfare, without embarrassment, without

any doubt, I talk directly to your soul. Listen to me.

Lift the oars from the water, let your arms rest, and

your heart, and heart’s little intelligence, and listen to

me. There is life without love. It is not worth a bent

penny, or a scuffed shoe. It is not worth the body of a

dead dog nine days unburied. When you hear, a mile

away and still out of sight, the churn of the water

as it begins to swirl and roil, fretting around the

sharp rocks – when you hear that unmistakable

pounding – when you feel the mist on your mouth

and sense ahead the embattlement, the long falls

plunging and steaming – then row, row for your life

toward it.

There is so much I love about this poem. I love that it is set on the water, and in nothing more elaborate than a rowboat. I love the words “roil” and “fretting,” and the fact that they are separated by nothing more than a comma. I love the provocation that life without love is nothing. But mostly I love the surprise at the end, which turns this poem into a short story of sorts; did she really say toward all that danger?

Although Oliver’s poetry is notorious for neglecting human subjects, I find real insight here into not only the “great lesson” of loss but also the equally great lesson of love. In a poem called “Gratitude,” Oliver brings these two subjects together. “Have I not loved as though the beloved could vanish at any moment, or become preoccupied, or whisper a name other than mine in the stretched curvatures of lust, or over the dinner table?” The answer, as readers of Oliver’s extraordinary poetry will instantly know, is yes.

So what about my experiment in the Dao of Mary Oliver? How did that go?

Not so well, I’m afraid. I did venture out, umbrella free, into virtually every storm I have encountered over the last few months. I paid better attention to the red-tailed hawks and blue herons that populate the salt marsh behind the cottage where I live—and, I suspect, to my friends as well. I continued to love impossibly, and tried to accept the losses that wild love brings. And while I did once get up once to greet the sunrise, glorying in that moment like the birth of a new child, I haven’t set my alarm that early since.

Still, my efforts to walk in the footsteps of Mary Oliver have brought me a stronger sense of my own mortality, a stronger determination to love madly whatever the cost, and a new mantra: “joy before death.” This mantra comes from Oliver’s poem “Blossoms,” which recalls for me the pond near my boyhood home, thick every spring with bullfrogs and possibilities. And though it is about beginnings, because it is about beginnings, this poem seems an appropriate place to end this walk.

In April

the ponds open

like black blossoms,

the moon

swims in every one;

there’s fire

everywhere: frogs shouting

their desire,

their satisfaction. What

we know: that time

chops at us all like an iron

hoe, that death

is a state of paralysis. What

we long for: joy

before death, nights

in the swale – everything else

can wait but not

this thrust

from the root

of the body. What

we know: we are more

than blood – we are more

than our hunger and yet

we belong

to the moon and when the ponds

open, when the burning

begins the most

thoughtful among us dreams

of hurrying down

into the black petals

into the fire,

into the night where time lies shattered

into the body of another.

Editors’ note: This story was originally published in the now-departed SEARCH magazine, in 2008, edited by KtB co-founder Peter Manseau. We thank them for permission to republish.

0 notes

Text

Exalted secret Santa Journal -17

Introductions of your choice of four (sort of) characters under the cut. 100% solar because everyone can use a bit of sunshine. The descriptions are long - again - and a lot of the text is copypaste from my last years’ journal. When, oh when will there be enough 3e books for our Storytellers to want to continue...

1) The Wind Which Sways the Cattails Growing in the Last Meander Before the Rapids Flowing Past Two Flowers in Bloom - She Who Walks the Wyld Unafraid, Heaven’s Voice, Silver-Tongued One [Eclipse Caste Solar]

“Wind” is a Linowan noble and the mother figure and diplomat of her circle. She isn’t above using her charisma and failing that, manipulation to redirect her circle’s focus as well as that of any misbehaving god they meet to a more beneficial course. One of her defining principles is “respect must be earned”.

Appearance: Wind is about 185cm (~6′) tall, with a reddish-orangeish hue in her skin and black hair with dark green accents that reaches halfway down her back. She prefers dressing in natural colours, though her transformative clothing gives her access to anything imaginable and she enjoys showing up in the appropriate dress to anything and outshining most others, especially if she’s thought to not be able to. The buckles and fastenings of her clothes are always wood or bone or horn, and her shoes moccasins decorated with intricate beadwork. She has simple gold buttons in each earlobe and one under her lower lip, which indicate her status as a noble. For equipment she usually wears an orichalcum chain shirt mostly hidden beneath her clothes and carries a blue jade chakram, lined with veins of blackened orichalcum and dotted with three staring crimson eyes.

She is never apart from her familiars, a mink who often wraps around her neck into a makeshift fur collar, and a juvenile prism dragon.

Her anima is filmy and fluctuating like aurora borealis, white with touches of green and warm gold. The iconic flare spreads its wings in the form of a massive osprey taking flight or swooping down.

Notable:

Appearance 4-5

Hazel eyes

Two beauty marks under left eye

References (for original body):

Middle one

Uncoloured for clarity

Things & weapon

With ‘Derp’

A MINK

Prism dragon

2) The Wind Which Sways the Cattails Growing in the Last Meander Before the Rapids Flowing Past Two Flowers in Bloom - She Who Walks the Wyld Unafraid, Heaven’s Voice, Silver-Tongued One [Eclipse Caste Solar (?)]

This introduction is here just for those who might want to have slightly more challenge / freedom of expression, as I don’t have any existing pictures of Wind in her new look.

No, this is not a mistake. In the current timeline, "Wind” has two forms. One the body she was born with and another a body her spirit currently resides in as she and her companions attempt to undo the future where her circle failed to stop the world from ending.

Inhabiting her new body, Wind still acts like a noble of Linowan, though her circlemates keep reminding her to not draw attention. She has also moved from diplomacy to deceit when it comes to influencing people, though it’s only because she finds it hard to be taken seriously as she is.

Appearance: Wind’s “new body”, though she intends it to be temporary, is that of a young northener girl, around 130cm (~4′3′’) in height and very slight. Her skin is pale and lightly freckled and her hair ash brown and roughly sheared to short, almost cloud-like waves that barely brush the tops of her shoulders. Her taste in clothing has remained the same even though obtaining her old standard of materials has become almost impossible. She favours leather, kept in shades of brown or dyed in muted shades of green and decorated with stitching or beads of wood, horn or bone. Her clothing is mostly practical despite aiming for elegance, warmed by the inclusion of fur.

Wind’s artifact equipment is under safeguard and out of reach, replaced by a feathersteel chainshirt she wears half-hidden by her clothing, a simple sling and a set of javelins. She has managed to get her ears pierced, but her face remains clear of piercings.

As Wind’s spirit changed bodies, so did her familiars, the mink becoming an Ice Weasel, and her beautiful prism dragon inhabiting the form of a northern Leech Bat. Wind takes solace on the strangeness of her familiars’ new forms in the fact that she is small and light enough to ride the Ice Weasel, who has a saddle for the purpose, masterfully crafted from leathers and furs. Meanwhile, the unsettling-looking Leech Bat is small enough to travel napping in a pouch, barely larger than a hand.

Her anima remains the same - filmy and fluctuating like aurora borealis, white with touches of green and warm gold. The iconic flare spreads its wings in the form of a massive osprey taking flight or swooping down.

Notable:

Appearance 4-5

Light grey eyes

Freckles faint but present all over body

References (these are just visualisation aids, sorry):

Appearance concept (minus hair)

Hair concept

Clothing Style concept 1

Clothing Style concept 2

Ice Weasel

Leech Bat (careful clicking on this if lamprey mouths and other such things squick you out!)

3) Nezu Mi, Light-Bringer [Zenith Caste Solar]

Nezu is generally cheerful and almost childlike, but able to turn severe and regal at the drop of a hat. She’s an acrobat and a priestess for the Sun that can call forth miracles, but above all she is a sorceress-craftsman. She dreams of the first age, and of returning its wonders to the world with her own hands and with those of her people.

Appearance: Nezu is a djala, with the baldness and panda-spotted skin that comes with it, and some 142cm (~4′8′‘) tall. Her eyes are sky blue and her body is somewhat pear-shaped with muscular legs built for jumping and a deceptively delicate upper half. She wears copious amounts of jewelry, mostly of materials other than metal. She prefers clothing that sits snugly on the top half but is loose and roomy at the bottom, and gravitates towards long sashes. She dislikes shoes altogether but wears sandals to avoid stepping on sharp things. For equipment, she carries a massive grand daiklave, most of the blade of which disappears when not in use, as well as a myriad of bags and containers filled with knickknacks. She also has a set of artifact bracers but wears no armour. She prefers clothing in cream gold, gunmetal grey and navy blue now that they’re set as the colours of her homestead-micronation. She also adores pretty dresses but so far Bad Things™ have always happened whenever she gets comfortable wearing one.

Her anima is a blinding white with the barest hint of pale gold and manifests a shape that is like an intricate sunwheel but also the ears and tail of a mouse, difficult to look directly at for its brightness.

Notable:

Appearance 2

Skin has a permanent bronze wash from Bronze Skin

References:

Rightmost one

Uncoloured for clarity

With sword

Spots

Flag for colour reference

4) Yarona Tukauati - Talon of Deepwater, [Dawn Caste Solar]

Yarona is a sarcastic tya from the Wavecrest Archipelago, as well as one of the best sailors and shipwrights of the whole West. She is the right-hand person of a growing island nation and the guiding force behind its construction. Her great joys are sailing through events impossible for a mortal to navigate safely, doing battle with her martial arts - a pun and flyting focused remix of the Nightingale Style - and seeing her country gain profit and progress.

These days Yarona is rarely apart from her recently acquired familiar - a Harpy Eagle she calls Ata. He rarely sits on her shoulder because of his size though.

Appearance: Yarona towers over most at 198cm (~6′6′‘) with defined muscles and a forceful presence. She has dark taupe skin and shortish windswept indigo-violet hair with varying haircuts. Her eyes are a shade of maroon and the right side of her face has intricate navy tattoo-work that indicates her gender as tya and continues down her torso all the way to her thigh. Yarona clothes herself in whatever happens to be at hand but particularly enjoys bright, decorative scarves. She wears a single gold hoop in her right ear and an artifact chainshirt beneath the topmost layer of her clothing. On her belt hangs a pair of black and white jade sais shaped like tuning forks, and her left hand is covered by a gauntlet shaped a lot like a bird’s claw.

Her anima manifests in the hues of sunrise, gold touched by red with ripples of purple. The image is that of a great warship manned by an immaterial army of light.

Notable:

Appearance 3

Barefoot most of the time (will wear shoes as necessary)

Actually more muscular than reference drawing shows

References:

Leftmost one

Uncoloured for clarity

Third one down - most recent attempt to figure out her face

Body reference

A harpy eagle

0 notes