#and nonprofits need money for consistent employees too

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

It’s worth noting that the 211 program started with a regional United Way (San Diego or Pennsylvania, I believe) and has since gone nationwide. Who mans and funds a 211 is dependent on the state/region and the nonprofits based there.

I mention this because how 211 and its host nonprofit may need donor help. Grants, contract for services with governments, and key, high worth donors (like the wealthy and companies) MIGHT be funding these programs. It’s usually a portion of overall cost though. And government spending is generally frowned on in the US. So Individual donations to these organizations are still critical.

Every United Way is a little different- please research to see if they’re hosting a 211 or resource navigation. And if so, please consider making a donation or suggesting a workplace campaign to help fund those efforts! These past couple of months we’re hearing and seeing the need for assistance spike throughout the US. If you prefer, donate to food pantries and nonprofits that assist with housing. One way or another it’ll benefit the whole!

If you live in the USA and you're pleading for donations to pay your rent, bills, or get food then dial 211! Please dial 211 before the last minute!

It's a toll free service with people who will help you find programs in your community to pay those bills, find food, and find housing! They will give you numbers to call so you can get help.

It is not 100% foolproof. Their job is to direct you to a program they believe will help your current issue, but it's still a step up from praying random strangers online will give you enough cash before a deadline! The added benefit of these community programs, which get funded by the local government most of the time, is if there are more people using them then they can get more money to help more people.

You're not taking resources from other people if you use your community services. Your taxes pay for them. Use them.

Dial 211 first to see if they can help, and if for some reason they can't, then make your donation posts!

https://www.211.org/

#nonprofits#united way#211#community assistance#literally every dollar counts#and nonprofits need money for consistent employees too#Volunteers are always welcome#volunteering

89K notes

·

View notes

Text

Very long and self-centered work rant incoming.

I know I've referenced a few things about what a hard and weird time it is at work and honestly I've only said about 5% of the truth of what all I'm carrying and that is going on. The ambiguity around what happens w/ my role, in particular, is killing me. I'm not at risk of losing my job, but a major leadership transition is looming and it's all very confusing. The cut to the chase is that I don't know what my role actually is in the new FY, which starts in 3 weeks now. It's a total shit show and in the process, I've discovered that I could be making almost twice what I make now at different nonprofits in fundraising, in positions that carry about 1/3 the responsibility and weight of other people's roles/livelihoods, etc. (It really is true when you are someone who STAYS you get penalized financially.)

I've loved this mission and this team for nearly 14 years now but IDK how much longer I can wait through all this bullshit. Someone I know from the Austin nonprofit world reached out to me to offer me free career coaching bc she's getting her certification and needs guinea pigs and I don't mind being one because I just need HELP and some outside perspective on what I actually want to do as I am 18 years into my nonprofit career at this point.

At our last session she asked me if I ever think about what's best for me instead of constantly focusing in on what's best for this organization and like I knew that's a problem for me but I didn't KNOW-know it until she said it. It's sitting really heavy for me.

I don't mean to sound arrogant, but I'm going to for a second. I'm really good at my job. Like REALLY REALLY GOOD. Like award winning in my industry good. Like has a reputation as one of the few very healthy mangers/team leads of nonprofit fundraising in Austin good. (All 3 of my current direct reports at different times have told me they'll also plan their exits when I go, and I've successfully retained all of them for 5-10 years depending on when they joined.) Like have been attempted headhunted many times but haven't ever wanted to leave this mission before good. Like I wanted to see what's out there that may want me, and I've gotten 3 interviews w/in 2-3 days of contacting some recruiters or putting my resume out there good.

And it's all just making me so fucking sad because I don't WANT to leave, but I DO want to feel appreciated and seen and make the kind of money my peers are, for doing FAR FAR less work....or to at least feel as recognized by my current employer as I do these prospective new ones for how obviously awesome and valuable I am.

I've always been an authority-pleaser (ugh abuse baggage.) I've damaged myself tenaciously reaching goals that were too much, too hard, etc. I've been working now for 25 years in some form or another and I'm consistently told I'm a top performer...so why don't I feel like it here and now??? I started working as a babysitter and tutor when I was like 13, and I began pulling down "real" paychecks when I turned 16. Across the dozens of jobs I've had, I've never had a single corrective action taken against me...I've never been written up or fired. I barely have any listed areas of "needs improvement" on any of my reviews across ALL TIME. I don't say all of this because it's how i believe employees should act, but because I just want to paint a picture for you as to what a dream I am to have on a team because my sense of self-worth has been toxicly linked to what I do/produce and if I can get an A, and if the teacher/boss/lead loves me, since Day 1.

And HEY KIDS, GUESS WHAT??? It hasn't been worth it!!!!!

Thankfully, I do get to take care of myself fairly well in my current organization's culture and I do take time off and I don't have to pull crazy hours. But I also carry and "produce" and take care of way more than anyone else in my side of the org. Way more than anyone SHOULD. It's been admitted to me several times by leadership that I am "the agency's most precious human resource" (even if they don't make me feel that way by how I'm compensated or treated when it comes to this ambiguity.) But carrying this much means I've probably had 2-3 true incidents of burnout w/ my org in the pushing 14 years I've been with them, but I always somehow found a way to recover and get back to happiness or at least contentment.

I'm not sure if that's possible for me now, and it's largely due to the fact that our board doesn't know what they're doing and they are torturing someone who they really really depend on for the agency to stay afloat w/ unnecessary ambiguity. I'm drowning in the ambiguity.

#mine#work complaining#personal#turning off reblogs ofc. but as a reminder a ❤️ to me always = a lil sign of support#nonprofit life

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

SO, WHAT DO WE KNOW about them, these vocal second-home owners? They worked hard for everything they own. They are clear on this. Their critics, they believe, are often motivated by jealousy. “I’m certainly not ‘rich.’ I’ve worked for my entire life to have the properties I own,” wrote one group member. Like many mountain communities, the Gunnison Valley attracts a motley mix of younger residents — seasonal public-land employees, ski bums who work the lifts, river guides, college graduates who stick around. “Irresponsible, non-tax-paying, bored children who will never plant roots here successfully,” one Facebook comment called them. In early April, a second-home owner from Oklahoma City, described “local adult skateboarders and bikers” picking up donated food at a food pantry in Crested Butte. “These takers need to pony up or get out,” she wrote. “Sadly,” another replied, “there are many entitled ‘takers’ here.”

In a phone interview, Moran dissected the implications of the word “rich.” Describing the second-home owners as such was a tactic employed by the media to “divide people by social strata,” he told me. I pointed out Gunnison County’s housing shortage to Moran, who, from 2008-2011, was an advisor of the private equity firm Lone Star Funds — the biggest buyer of distressed mortgage securities in the world after the 2008 financial crisis. After the crash, the firm acquired billions in bad mortgages and aggressively foreclosed on thousands of homes, according to The New York Times. I asked Moran if, compared to locals who struggle to pay rent, people who own two or more properties should be considered wealthy. “I think that’s wrong,” he replied.

Over the summer, I obtained access to the Facebook group. Beneath the anger at the County Commission and the exasperation with the local newspapers and adult skateboarders, a deeper grievance burned, one that was expressed consistently in the group. “Our money supports all of the people in the valley,” wrote one man. “Where is the appreciation and gratitude for the decades of generosity?” wrote another. According to the second-home owners, Gunnison County’s economic survival and most of its residents’ livelihoods depend on their economic contributions and continued goodwill. Their donations prop up the local nonprofits. Their broken derailleurs keep the bike shops open. In late April, Moran sent an angry message to a local server who had criticized the second-home owners, posting his note to the GV2H Facebook group as well. Moran, who had apparently left the server a large tip, called her comments “a betrayal of the good people who have been gracious to you.” Around that time, there was talk on the Facebook group of compiling a list of locals they considered ungrateful. “People who rely on others for their livelihoods should not bite the hand that feeds them,” wrote one second-home owner.

The list, which was posted on Facebook, became known as the Rogues Gallery. It named 14 people described as “folks who oppose GV2H.” The list, which was later deleted, included a local pastor and an artist. Sometimes it noted where someone worked and what they did. Repercussions were hinted at. “One of those big mouths is slinging drinks for tips — I’ll be sure to leave her a little tip — ‘Maybe don’t run your mouth so much on social media when you depend on those people to help pay your bills,’ ” one Facebook commenter wrote.

Amber Thompson, a longtime server at Crested Butte restaurants, was not in the Rogues Gallery, but was mentioned later as a possible addition after several online arguments with Moran and others from the GV2H Facebook group. She gets especially mad, she told me, when a second-home owner cites a big tip as evidence of their authority and value. As a server, she said, her job is simply to deliver food. The demand for gratitude, the resentment when they don’t receive it: “It’s a way to intimidate people, to make them bow down, and I just won’t do it.”

The first name on the Rogues Gallery was Ramgoolam, and he, too, declined to back down. His offence was a Facebook post in which he asked why Gunnison County residents were incapable of making their own political decisions — a thinly veiled critique of the super PAC, which Moran had registered in May. Shortly after learning about the Rogues Gallery, Ramgoolam wrote another Facebook post, thanking the community for its support during the pandemic. It included a picture of him in a red bandanna, carrying a Captain America shield. He intended it as defiance.

“I think (the super PAC) spits in the face of the relationship we have with our neighbors in this valley,” Ramgoolam said. “Whether you are a primary homeowner or a second-home owner, you respect people’s opinions and everyone is welcome to the table, but to overpower everyone at the table and try to take all the chairs for yourself is just wrong.”

For many in the Facebook group, opinionated locals interfered with their ability to relax and enjoy the Gunnison Valley. Fun, after all, is what brings them to Crested Butte. But fun was hard to come by in 2020. People were irate when the county declared a mask mandate on June 8. “We come to decompress, to relax, to regenerate!” one person wrote. “That’s a pressure we don’t need! Or don’t WANT, which isn’t a crime either!”

This came to a head when local demonstrations were held, prompted by George Floyd’s killing by Minneapolis police. One of them took place on June 27, in Crested Butte. After a short rally, a crowd proceeded up main street, led by the Brothers of Brass, a funk band from Denver. Demonstrators then lay on the blacktop for 8 minutes and 46 seconds, the time that Officer Derek Chauvin knelt on Floyd’s neck. Many diners, who were sitting at outdoor patios on either side of the march, paused their meals for the duration. But on the Facebook group, indignation bubbled up. “People come to the Valley to relax and enjoy nature,” wrote one commenter. “This is made impossible when ‘protesters’ are bused in for a photo-op (not to mention pollution, noise, aggravation, and trash).” Several other commenters also insinuated outside influence. (Other than the band, there is no evidence that the protesters were not primarily local.) The Crested Butte Town Council’s subsequent decision to paint “Black Lives Matter” on the main street prompted another wave of irritation. “Crested Butte has clearly forgotten why people (tourists or second homers) like going to the mountains. It’s about escaping the craziness and the BS of the cities,” one of the second-home owners wrote. A few others announced that they would no longer go downtown.

This hostility came as no surprise to Elizabeth Cobbins, the lead organizer of the Gunnison Black Lives Matter demonstration. The second-home owners come to their vacation properties to “escape the real world,” she said. They forget, she told me, that the valley is more than a ski destination. It includes a college that is home to many students of color, and a sizable Hispanic community. The second-home owners feel their opinions matter because of their economic contributions, which, Cobbins said, are important, but, “the people who serve them live here, too, and they live here for the whole year.”

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

What can I do to limit Amazon’s* negative impacts without harming vulnerable communities who rely on their services?

* or any similar company that people are forced to use to survive if they are poor, disabled, elderly, rurally isolated, or any combination of the above

My post on Amazon has been circulating pretty far these past few weeks, and a lot of people keep trying to argue about what can be done right now.

1. Contact your representatives

If you live in the US, there are several sites you can use to figure out your senators (you have two) and your representative (you have one). Call them if there’s a phone number. Email them if there isn’t. They’re obligated to have SOME form of contact. If your rep is already on your side, they can use your email as evidence for how citizens feel about the issue when Congress is in session to argue. If your rep is NOT on your side, they will see the email as evidence that a portion of their constituency is NOT willing to reelect them if they don’t play nice, and that scares them a lot. Either way, make yourself heard. Harass them if you have to.

(For more local issues, especially things like minimum wage and labor laws, you can find your representatives for your state or city government, like your mayor or governor or county rep, and contact them as well. Make yourself heard.)

Write emails in your own words about one of the following subjects:

Supporting the USPS. It’s the backbone of the US shipping industry, and major shipping companies like UPS, FedEx, and Amazon use it for overflow.

Monopolies and antitrust acts. Reference past antitrust acts leveled against oil, railroad, and telecom monopolies.

Raising the minimum wage. Reference inflation.

Enacting a marginal tax rate on high earners (re: the 1%, but phrased in a way that they’ll take seriously). Reference the marginal tax rates of the fifties.

Increasing disability benefits. Try to work something in about how stringent the requirements to qualify are, and how benefits don’t cover enough for medical care, transportation, assistive technology, and so on.

Increasing social security benefits for retirees. People pay into this fund all their lives as part of their income tax; it’s supposed to benefit them right back! (You can circle back to marginal tax rates and how the rich usually have savings and don’t need social security, but the poor often don’t have savings and rely on it.)

Enforcing corporate taxation. Find some statistics on who paid corporate taxes in the past few years and who didn’t. Make sure to find a few big names and what their tax rate SHOULD have been. Emphasize how much extra money the government would be making.

Nationalizing the health care industry. Reference how well it works for countries like Canada, Korea, or Sweden, and how often hard-working Americans are bankrupted by unexpected medical emergencies.

Enacting or enforcing higher standards of employee rights. Did you know that minimum wage employees in Indiana don’t have the right to a lunch break unless they’ve been working at least twelve hours?

Legal repercussions for predatory pricing practices. Walmart is the best-known for this, but Amazon does it too, and they’re a fair bit sneakier about it.

Capping rent prices. Housing costs are among the highest financial pressures Americans face right now, and the fact that housing costs have risen SO much faster than the minimum wage is why it’s impossible to rent a one-bedroom apartment on a minimum wage anywhere in the US right now.

Capping upper management incomes. A CEO should not be earning several thousand, or several million, times as much money as their employees. It’s a long stretch (so argue the more achievable things first), but imagine if we could convince the government to say “actually, you can only make up to twenty times as much per hour as your lowest-paid employee.”

Banning police as threats against unions. UNIONS ARE GOOD THINGS. SUPPORT THEM.

Anything else that comes to mind! There are lots of subjects. This list is not an exhaustive one.

2. Vote

Pretty self-explanatory, I think. Vote in every election. Sometimes you won’t be able to vote for your top choice, and that sucks, but remember that our system is fucked and you have to go for the lesser evil that’s still capable of winning. So vote Blue (because ambivalence to our desires is better than glee at our suffering), and then send as many emails and make as many calls as you can to force them to recognize that, since you helped them get into office, they have to honor the deal to actually represent you now.

3. Support small businesses

Okay, so supporting local businesses probably isn’t too easy in a pandemic. You can’t just walk to your nearest mom and pop store to see if there’s an affordable option. That said, if you can afford to do so, try to see if there are small businesses in your area that are doing delivery or curbside-pickup.

If you live in a more rural area, see about ordering from small online businesses for non-essentials. If you’re thinking “hey, I’d like a new scarf” or something, check Instagram or Etsy first. All faults aside, Etsy is only a marketplace, not a seller themselves, so they rely on the vendors using their site to remain in business. (Whereas Amazon tries to drive their vendors out of business to take over their market share.) You can also use Google Shopping, eBay, or Craigslist.

4. Don’t Use Amazon (or similar), but don’t shame people for using it either

Some people rely on loss leaders to survive. That’s a fault of the American economy being a horrifying mess, and I listed a whole litany of the causes above. Money talks, so avoid using Amazon unless there is NO other way to get your product, but if someone you know uses Amazon, and you know they’re struggling, keep your mouth shut. If they’re not struggling, mention your distaste for Amazon but don’t push the issue; they’re more likely to come around if they feel like you’re not passing a moral judgement on them for it.

5. Recognize that many fairly-priced products are more expensive than you’re used to

The example I usually use is fashion. We’re used to a shirt costing ten or twenty dollars, even at places other than Walmart or Target. This price is what we’re led to believe is reasonable, but it’s really a factor of incredibly underpaid workers, usually overseas. If you can’t afford it, feel free to blame the low minimum wage (I certainly do), but remember to take a step back and remind yourself that it’s not that the piece is expensive, it’s that you are underpaid, and the current system is trying to teach you to expect cheaper items as the norm so they can get away with paying even more people less than they deserve.

6. DONATE

Yeah! There are a whole lot of nonprofit agencies that focus on issues that relate to this topic. I prefer to donate to organizations that focus on enacting systemic change through legal or institutional channels, like the ACLU and AAPD, but there are a lot of options, some of which focus on more direct help, or on specific parts of the country. Figure out one that speaks to you, check it against a trusted charity rating system like Charity Navigator, and set up a monthly donation if you can afford to. Constant support can cause compassion fatigue, but consistent support is how you Get Shit Done.

7. March

Join an activist group and march. Sometimes there are other major events going on (hijacking one of the current marches against racism and police brutality in favor of one about monopolies would be in bad taste AT BEST), but there will come an opportunity to make your voice heard by showing up on the street and just yelling with a sign.

Now go forth and unleash hell.

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

advertising is bullshit. not just for the carbon emissions, not just because they don't work, not just because they gather information on individual users, not just because unbridled capitalism is fundamentally broken without consistent regulations and control, not just because businesses are putting ad revenue ahead of human life.

here's the thing

you ever heard of acorn?

no not the video streaming service

there's an app called acorn that enables short form investment capital. you put in pennies to businesses to financially support them and if/when those businesses are successful then the amount of money you invested gets to be a lil bit more. so it's basically the stock market. you cannot eat the rich if you don't know what they eat. anyway it's a way to make supplementary income that's as far as I know untouchable by the IRS. but that doesn't matter. the thing is that this thing exists.

I can guarantee that 9 out of 10 people reading this has no idea that this app existed. and it's probably because you don't ever see ads for it. they don't really advertise. it seems to be some sort of communal hub for mass mutual financial growth among corporations and investors since that's how stimulating economics works. you don't hear about it on tv, radio, internet, video games, magazines, whatever. so clearly they have a tiny if not nonexistent budget for ads.

gambling ads are fucking everywhere. you got casinos, you got fantasy football leagues, you got horse racing, you got private pools for F1 and nascar, you got lottery scratch off tickets, you got fortnite overwatch battlefieldfront etc lootboxes, you got so much shit shoveled out every orifice of society, media, social media, radio tv websites and magazines. everywhere. they have a huge budget for ads because they are traps designed to steal money from gullible idiots privileged enough to have extra cash. and they take maybe 10% of that and sell out adspace to attract more gullible idiots. it's a predatory business model and it WORKS and it works because people are stupid and they're still clicking on ads and buying lootboxes and scratching scratchoffs and betting on football.

gambling doesn't serve society. it's a for profit model that the privileged elite use to suck up extra cash from sad pathetic losers who chase that high from a squirt of serotonin from hitting three lemons or a solid gold ak47 skin or a jpeg. so they can afford to throw cash away on ads.

but sheena, I hear you ask, what about all of the businesses that DO provide valid services to society?

spotify makes enough money from ad revenue to shill out Premium™ to people who happily vomit up $5/monthly en masse. even though there's plenty of ways to listen to music that a) directly benefit the creator or b) are 100% free.

places that serve food make so much extra money from sales that they can afford to fuck over they're employees by paying them dirt and shill out for ad spaces even though nobody's gonna watch a commercial for red lobster on tv and think OOOHHH I WANT JUMBO SHRIMP and you know why? because people who are rich enough to eat ad red lobster on a whim all have enough income they probably have dvr or Premium™ streaming and don't see ads in the first place. they're gonna spur of the moment think mmm cheddar bay biscuits (because when the fuck has red lobster shilled their delicious biscuits??? NEVER, THEY SHILL THEIR SCAMPI LINGUINI AND L O B S T E R.

(red lobster did not finance this post and you can easily find imitation recipes anywhere on google but damn what tasty cheesy bread).

United States Military spends $100 MILLION dollars on shilling ads to join the army on poor people's tv to boost enlistment for their blood machine instead of the government taking that money and using it to finance our schools. we can literally cut our military budget from $780 BILLION dollars to $779 billion- that's B as in billion- remove all military ads from our TVs and buy new textbooks for every single school in the entire country. I don't know why learning institutions hide knowledge behind class gates and why historical mathematical scientific and artistic groups don't just fucking give copies of one textbook about the subject to everyone, or why the publishing companies want so much goddamn MONEY from FUCKING SCHOOLS for LITERAL CHILDREN to LEARN but whatever I'm just someone who succeeded in high school in spite of its hundreds of open glaring flaws but whatever. anyway the point is the military could give money to groups that want to end wars but no they want poor people with nowhere else to go to oil the gears with their entrails so we can continue bombing the shit out of the middle east to steal their petroleum. and ads is how they do it.

charities who claim to want to help kids with cancer or endangered animals will gladly take vast portions of the money well meaning idiots send in, pocket 1/4 of it, put another 1/4 in the tv commercials, give 1/4 to some female adult contemporary singer who isn't famous anymore to sing a sad song over the sadness porn and then give the remaining 1/4 to people who are constantly failing to cure cancer, save animals, and just give up and join the nonprofit orgs that actually accomplish things instead. if a charity can afford to spend millions of dollars on fuckin ADVERTISING, they're a bunch of bloated and corrupt bastards who shouldn't be trusted with a goddamn penny. their members should be promoting shit FOR FREE if they actually care. not buying ad space on the cw tnt cbs & nbc. unless the businesses DONATE ad space. but they don't do that because all CEOs are evil. lol

what does wikipedia do when it needs cash? it POLITELY ASKS FOR MONEY IN A BANNER IN THE CORNER OF THE WEBSITE. ao3 does it too. and if dumb motherfuckers wanna shit on wikipedia for being the most accurate and communally moderated source of information on the entire internet "inaccurate"[citation needed] or ao3 for being the last bastion of independent fiction against federal censorship whores and virtue signaling white-knight moral guardians who don't actually care about victims of rape and csa "having incest fics", and yet say absolutely nothing to greedy conglomerates who destroy the planet, commit genocide and enslave coastal & island nation child residents, spread eugenics & other evil pseudoscientific propaganda, sexualize infantilize and fetishize women, and let millions die from cancer every day? then they're just as culpable.

fuck advertisements.

unless you're an independent content creator or something in which case that's not ads it's marketing and publicity which is different.

5 notes

·

View notes

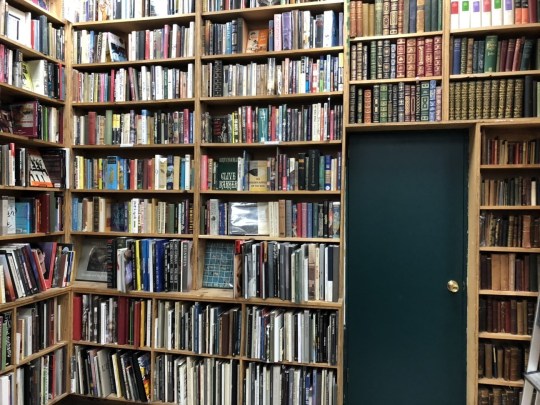

Photo

Shared from @thecomradecloset Original caption: “This is one of the first photo-essays I wrote way back when (as in almost exactly a year ago lol). I had been struggling with months of unemployment after the end of another nonprofit position that left me in extreme pain and constantly sick. These are some of my compiled reflections after about a decade of being in and out of the NPIC realm - I figured they could use a design upgrade from quickly typed story notes Thank you to @subversive.thread for helping format and streamline this piece. And shout out to @nowhitesaviors for taking on the work of challenging and outing anti-Blackness and white supremacy in the social good/nonprofit sector.”

ID: Reflections on the Nonprofit Industrial Complex “After years of working in the nonprofit industrial complex, I’ve seen white saviorism replicated repeatedly in the name of ‘helping the community.’ Over and over again, white leadership teams have created and dictated work policies to BI&POC employees, tokenized and otherized BI&POC program participants, and funneled large grants towards white-led research projects that could have been answered easily by people who have been deeply impacted by hierarchies of oppression. It’s mind-blowing when I hear nonprofit leadership / founders talk about how they really need to work on having community connections.

How can you work in a community without starting with the fundamental requirement of having relationships within that community? It reminds me of white entitlement, of the phrase ‘nothing about us, without us.’ Because nonprofits were created with the intent of neutralizing and funneling resources away from BI&POC resistance movements, they are the embodiment of white saviorism: hierarchical charity rather than solidarity; volunteering as a hobby / a philanthropic act of donating leisure time; and the performance of self-sacrifice as a measure of commitment. This often leaves little to no room for an analysis of systemic oppression - or of the ways in which white leadership is still complicit with white supremacy. For example, white-savior expectations of self-sacrifice and charity are (re-en)forced upon direct service workers who are mostly BI&POC, often on the lower rungs of the nonprofit hierarchy — ignoring how the circumstances or backgrounds of their BI&POC employees are frequently similar to, if not the same as, the ‘target populations’ that the organization ‘serves.’ BI&POC workers are expected to donate free time past our paid hours and to push ourselves far beyond our capacity in order to demonstrate our ‘commitment to the cause.’ There is a longstanding myth that there is no money for nonprofit or social work, so BI&POC employees are also pressured to donate to charitable causes as if we aren’t struggling too. We’re told that this is ‘just the way things are’ and that we must focus on maximizing output and minimizing costs, nevermind sustainable workloads or a living wage. Meanwhile, there are 501c3 executives who are awarded six-figure salaries when direct-service employees are the ones who work most closely with clients who are often in crisis mode or navigating deep trauma. Unsurprisingly, the majority of nonprofits perpetuate an ableist capitalist work ethic of endless production, an obsession with metrics and measurable data to ‘prove’ worth to investors and funders, often compromising meaningful work for rapid growth and scaling services year after year.

In part, this is because under capitalism people have internalized the idea that social work, especially in a direct service capacity, is simply less valuable — and therefore not worth the investment. This is unsustainable. We should be able to work for and support the communities that we are from — but it shouldn’t come at the cost of our own survival, nor should it be subject to the exploitation and gaze of white leadership. This isn’t to say that nonprofits led by BI&POC are automatically better — they might also overwork their staff, refuse to interrogate their ableism, maintain power imbalance through strict hierarchy, or work closely with carceral state agencies. Although nonprofits are often the closest we can get to doing meaningful paid work while also supporting ourselves with a consistent income, they’ll never be enough. It’s important to keep in mind that nonprofits work to reinforce the status quo and exist very much within the system, not outside of it. We need to keep building and supporting alternatives wherever we can. Ultimately, no community relationships should need to be mediated by state-sanctioned 501c3 organizations. As anarchists, our major goals are community self-determination and autonomy. And we won’t see liberation as long as we rely on venture capital to fund our work.”

#Nonprofitindustrialcomplex#autonomy#liberation#nonprofit#NPIC#toxicnonprofits#burnoutculture#burnout#capitalism#anticapitalism#anarchism#BIPOC#comradecloset

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

Wage theft is when your boss doesn’t pay you what you’ve already earned. When I learned that Massachusetts had “blue laws,” that my bosses weren’t obeying them, and had shorted me around three thousand dollars, it was wage theft.

This was the law: retail employees were to be paid at a “premium” rate on Sundays and holidays, time-and-a-half, the same as overtime. But none of the booksellers where I worked had ever been paid it. And while not being paid overtime is a textbook example of wage theft, when I tell people, they are happy to qualify it for me with a “Well…” or an “Okay, but…” I don’t know where this instinct comes from. Maybe it’s because “wage theft” makes it sound premeditated, more like a crime. (But it was a crime!) Or maybe it’s because I worked at an independent bookstore, and indie bookstores are beloved pillars of the community. (What would that mean about the community?) Maybe it’s because it doesn’t makes sense that an independent bookstore would do something like this. Everyone knows indiebookstores are thriving! (Which is true—it’s the people who work in them who are struggling.)

I found out when I was trying to see if I could afford to take a sick day. I felt like I was coming down with something, but taking a day off meant losing a not-insubstantial chunk of my monthly take-home pay ($11.50 an hour). Since there were sick hours adding up in a box labeled “time-off accrual” on my pay stubs—and surely they had to amount to something—I went to mass.gov to check the law. But they amounted to literally nothing, as it turned out: Massachusetts businesses only have to provide paid sick leave if they have more than eleven employees, and we had ten. My “sick days” meant I couldn’t be fired for staying home sick (as long as I wasn’t sick more than five days per year).

But I learned something else. There were links to related pages and I clicked the one about “blue laws,” which I didn’t know we had in Massachusetts.

Later that day I emailed the bookstore’s owners. Is there a reason our bookstore is exempt from blue laws, I asked, or was this an oversight?

They responded the same night. They’d heard that other area bookstores had to pay the premium rate, they said, because their booksellers were unionized, but that otherwise there was some exemption. They said they would investigate, that they’d talk to their lawyer and get back to me.

After that the story gets so routine you could probably write it yourself. When I followed up a few days later, they said their lawyer was on vacation but that they’d update payroll and we’d receive the premium pay on Sundays and holidays from then on. When some of the other booksellers and I contacted the Attorney General’s Fair Labor Division, they only sent a form letter saying the matter was too small for them to investigate personally, but we were welcome to pursue legal action (on our own time and at our own expense). I found some free legal clinics on wage theft, but only once-a-month and while I was scheduled to work. Ten days after the first email, I followed up again; “still the same conflicting intel,” they said, “but when we told our lawyer that we started paying 1.5 for sundays and holidays, the matter dropped. (lawyers are expensive!) let me know if it’s not reflected in your check.” A coworker who already planned to quit asked the owners specifically about back pay–which I hadn’t had the courage to do—and they told her no, they weren’t going to pay it, and they said it in writing.

I ended up speaking to a lawyer, who offered to represent me on a contingency fee basis: I wouldn’t have to pay if we lost, and the bookstore would be responsible for my legal fees if I won. But he recommended I not move forward until I got a new job. It isn’t legal to retaliate against an employee for bringing a case, he told me, but, you know, it also isn’t legal to ignore blue laws.

I said thank you, I’ll consider my options.

One day in November one of the owners called me into the office at the bookstore. She gave me $500 in cash and $500 in store credit, about a third of what I was owed. I spent the store credit on gifts for the holidays and I looked for a new job. I ignored a follow-up call from the lawyer and tried not to wallow in the humiliation. I was not successful. Even now it feels like admitting something shameful: I was fooled, maybe, or I’m some kind of miser. A few people asked me, what if they can’t afford to pay back pay and they go out of business? You hear it more than once and it’s easy to forget it’s not a ransom, that you didn’t pluck the number out of nowhere.

It’s hard to compare independent bookstores to other kinds of retail stores. Bookstores sell a cultural product and booksellers insist that bookstores can’t be compared to other retail stores because they sell a cultural product. And bookstores don’t exploit their employees more than other retail. But what grates is when bookstores market themselves as more than stores, as community hubs.

“Independent bookstores act as community anchors,” the American Booksellers Association declares, at the bottom of every page on their site; “they serve a unique role in promoting the open exchange of ideas, enriching the cultural life of communities, and creating economically vibrant neighborhoods.”

This same lofty idealism justifies why booksellers don’t need to be paid a living wage, like employees of nonprofits or teachers: because bookstores are so vital for the community, the assumption goes, the job should be reward enough itself. The work is so important that maybe booksellers should make personal sacrifices, working well below the value of their labor.

I spoke to around twenty booksellers while I was writing this, and I was struck by how many are willing to make trade-offs. Perhaps I shouldn’t have been. “Independent booksellers consistently describe their work as more than just a way to make a living, and more than just a means of escaping the constraints that come from working for somebody else,” writes Laura Miller, in her 2006 book, Reluctant Capitalists: Bookselling and the Culture of Consumption; “These booksellers see themselves as bettering society by making books available.” Plenty of the booksellers I spoke to saw bookselling as a calling. Because of course they do! If they weren’t willing to make sacrifices, they couldn’t still be booksellers. And how else could bookstores get away with paying them—they, who generally have to have a college degree; who have to spend a lot of unpaid time reading across all genres and topics; who have to have at least a little knowledge about everything, from the ancient Greeks to Dog Man 7: Brawl of the Wild; who, at at least one store, famously have to correctly answer quiz questions before being hired—so little, while so successfully preserving an image as a (generally progressive) force for social good?

And it is so little. A bookseller in Southern California with eight years of experience still earns less than $20 per hour; “I can’t think of another industry where you could work for eight years and still be making that little,” he said. A different Southern California bookseller/assistant events manager earns $17.50. A bookseller/assistant events manager in the Boston area is earning $14. A former bookseller in Northern California was making $14.25, a quarter above the minimum wage. A part time bookseller in Chicago makes $13, the city’s minimum wage. A former bookseller in Minnesota was salaried after two years at $30,000 while a bookseller and events manager in Tennessee started at $25,000, six years ago, and now makes $31,500.

I started at $11 per hour and ended around eighteen months later at $11.50, and as far as I know, none of the booksellers at that store even earned $15. The median rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Boston is $2400 per month, which I could cover if I worked 50 hours a week, didn’t pay taxes, and didn’t need money for food, utilities, medical care, or literally anything else.

The booksellers I spoke to reported quite a range of benefits—in one year, for example, a Bay Area bookseller accrued three weeks of vacation time, and in the same time period a Pennsylvania bookseller got three days. But some booksellers told me that their benefits were mostly on paper. Not being fired for calling in sick or going on vacation doesn’t make it financially viable, after all. A Minnesota bookseller told me she has ten paid vacation days per year, but the store has so few employees that taking time off means she’d have to make up the missed hours working overtime. A bookstore in California offered a health insurance program, but gave employees a fifty-cent raise if they didn’t enroll.

It’s not so bleak for everyone. Unionized stores generally fight for better benefits and act as safeguards against labor law violations; I talked to a handful of booksellers whose stores had some kind of profit sharing, which can make a big difference.

But… I don’t know. There’s a bookstore owned by people who, all evidence suggests, really give a fuck and want to do right by their booksellers. They pay at least $15 per hour, and I heard one of the owners say on a podcast how much is required of booksellers; “If you’re a college graduate, and you’ve spent all this time reading, in addition to going to college—yeah, you deserve $15 an hour. Period.” But when his interlocutor mentioned a bookstore that had profit sharing, the owner was quick to say it wouldn’t work at his store. (And it wouldn’t, yet—the store is young and not yet profitable.*) But “It’s also a matter of loyalty,” he said, and explained that he couldn’t envision employees staying longer than a year. “I would love to find a bookseller who I know would be around long enough. Right now it just hardly seems even worth doing all the work. No one would qualify, because they won’t stick around long enough.”

Tell me, what are they going to stick around for? The bookstore owner said all of his employees are part-time—they’re either in grad school or working other part-time jobs. Are they supposed to stick around for a part-time job that pays $15 per hour?

What is there to be loyal to?

IndieBound—an ABA project—has a section on its website dedicated to answering Why Support Independents? One answer is that “Local businesses create higher-paying jobs for our neighbors.” But you can also find a page at the ABA website on “The Growing Debate Over Minimum Wage,” warning that “a minimum wage increase that is too drastic could result in reduced staff hours, lost jobs, or, worse, a store going out of business.” There’s also an “Indie Fact Sheet” to print out and give to local politicians; “Many indies pay more than the current minimum wage already for senior and full-time staff,” it says; “They do this because offering superior customer service is one of their competitive advantages—it is what separates them from their chain and remote, online retailing competitors. This also helps indies retain and attract good employees.”

See? Many bookstores pay their booksellers more than the minimum wage! It’s not their problem that that same minimum wage isn’t enough to cover a one-bedroom in any state in the country. It’s not their problem that inflation has eroded the value of the minimum wage. It’s not their problem that low wages are an affront to basic dignity or that higher minimum wages save lives. They’re just fiercely committed to their neighbors and their communities.

The ABA is happy to help its member stores fight even modest wage increases. “If the minimum wage is raised,” the Indie Fact Sheet continues, “it inevitably means indies will have to increase the wages of senior and full-time staff, in addition to increasing the wages of any minimum-wage workers. This increases the ripple effect. A seemingly ‘insignificant’ wage increase can have a dramatic effect on the bottom line, sending a profitable store into the red.”

There’s no mention of the dramatic effect an increase in the minimum wage could have on employees.

At Winter Institute–an annual ABA conference for independent booksellers–there’s a town hall where members can share their concerns. According to the ABA’s coverage of the event, an independent bookstore owner went to the mic to speak about the minimum wage. “I’m very happy the staff is getting a pay bump,” she said, “but that’s a huge adjustment to make every 12 months and once you get a handle on it, then it’s going up again. I feel like this seems to be going countrywide and that is something that is extra important to our nonexistent margins.”

Why this framing? Why not ask how other stores are handling the adjustment? Why not pay employees a living wage now so as not to have to change business model every year? Why does a bookstore owner feel comfortable getting up and saying this in front of an audience of booksellers?

If your local indie bookstore skirts labor laws or advocates against them, at the expense of its employees, can you still be sanctimonious for shopping there? Is your local indie bookstore thriving if its employees skip doctor’s appointments they can’t afford? If your local indie bookstore’s trade group doesn’t have resources for booksellers on paid sick leave, health insurance, or wage theft–in an industry famous for its tiny margins–is it an industry you’d recommend joining?

“We find ourselves in the uncomfortable position of being believers in social and economic justice while struggling to pay our employees a salary they can survive on,” writes Elayna Trucker on shopping local and running a bookstore; “We urge our customers to Shop Local but make hardly enough to do so ourselves. It is an unintentional hypocrisy, one that has gone largely ignored and unaddressed. So where does all that leave us? Rather awkwardly clutching our money, it seems… All of this brings up the most awkward question of all: does a business that can’t afford to pay its employees a living wage deserve to be in business?”

I am so glad I don’t have to come up with an answer. I have no idea. I haven’t the faintest idea at all.

In the end it was a tweet. I left the bookstore after the holidays and started a new job in January. In February, after a night of shitty sleep, I tweeted, “I have been spending hours lying awake at night doing nothing but feeling this intense shame like a stone in my chest about experiencing wage theft at my last job and I am sincerely just hoping that tweeting about it is enough to make it stop so let’s see if it works.”

A day or two later I got an email. “It’s filtered back to me that the $1000 we gave you to settle the Sunday pay issue,” they said, “didn’t resolve it.” They said some things about how they hadn’t known until I told them. They cut me a check for the back pay that same day.

I didn’t delete the tweet. I don’t know if any of my coworkers got back pay.

A little later, I read an article about the student-run Harvard Shop in Cambridge. The Massachusetts Attorney General’s Office found that the store owed almost $50,000 in back pay to their employees and $5,600 in fines for violating blue laws. “In this case, we unknowingly did make a mistake in how we were paying our students for Sunday and holiday pay,” the store’s manager said.

I only saw the article because the union I joined at my new job shared it on Twitter.

In Seasonal Associate, Heike Geissler’s barely-fictionalized account of her time working at an Amazon fulfillment center, she writes: “What you and I can’t do, because you and I don’t want to, is to think your employer into a better employer, and to compare these conditions to even worse, less favorable conditions, so as to say: It’s not all that bad. It could be worse. It used to be worse. We don’t do that. You and I want the best and we’re not asking too much.”

I loved bookselling. I loved it for the same reasons everyone does: the community of readers and booksellers, the joy when someone came back into the store and says I recommended the perfect read, the pride when authors reach out directly to say how much my work meant to them. The free books, the discounts, the advance copies, all of it. And I do believe that bookstores can be forces for social good, insofar as bookscan be forces for social good, which I think they can. It is self-evidently better to get your books from a local store than from Amazon, and for precisely the reasons the IndieBound website gives.

But it’s not enough to Not Be Amazon, and framing bookstores as moral exemplars regardless of how they treat their employees isn’t to the benefit of booksellers. Bookstores “thrive” by hiding how much their booksellers struggle. “Any thriving I do personally is in spite of my store,” one of the booksellers I spoke to said. Working at a bookstore is not as bad as working at an Amazon warehouse; I didn’t walk dozens of miles per day and my bathroom breaks weren’t monitored. But are we willing to let that be the baseline?

*clarification added after publication

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Startup SEO: How to Get the Ball Rolling on a Limited Budget

Search Engine Optimization (SEO) can be a complete nightmare if you are a new startup. The majority of new startups know that SEO contributes to online success but many do not fully understand how to develop an effective SEO strategy. SEO companies from every corner of the world constantly contact new startups, promising the same outcome: top rankings in the search results. There will be large experienced digital agencies that will quote large five-figure monthly retainers and there will be some overseas companies that will promise the world for a few hundred dollars a month. This confusion can be quite overwhelming for a new startup, especially one that is launching with a very limited budget. Paying a premium for service that doesn't deliver the promised results can quickly deplete a marketing budget and selecting a poor service can get the website penalized, presenting the startup with a major handicap from the start. The worst thing a startup can do is hire a low quality SEO company in an effort to save money. The cost to clean up the mess they create can far outweigh what it would have cost to go with a more expensive and experienced agency from the start. If your startup is brand new and you don't have the budget to hire an experienced SEO agency then take a deep breath and follow the tips below to start your search engine optimization internally until your revenue can support the cost of professional help. Get Your On-Page Optimization Perfected First Many startups (and SEO companies) forget about one of the most important search engine optimization factors Blog9T for long-term success, and that is the on-page optimization of the website. Neglecting the on-page optimization is like attempting to run a marathon with one leg. Sure, you might eventually get to the finish line, but it is going to take much longer and you are putting yourself at a severe disadvantage from the start. I was recently speaking with Weston Bergmann, lead investor in BetaBlox, which is an equity-based business incubator for startup entrepreneurs in Kansas City, and he also compared SEO to a marathon: "The most important thing to note about SEO for early-stage ventures is it's a marathon, not a sprint. I see too many people getting frustrated by a lack of stellar results in the first couple months, when this just isn't possible. These fights are long-term ones, so buckle down and stick to the basics. Eventually you'll look back and see that you've built a monster." Want to learn what proper on-page optimization consists of and steps you can take to make sure that your website is ready for SEO? My company SEO Blog9T used our nonprofit marketing page as an example and created a guide to help you with on-page optimization: The Definitive On-Page Optimization Guide. Build a Strong Social Media Presence (Attract Social Signals) A startup needs to have a strong social media footprint from the day of birth, and a well thought-out social media effort can help the growth of the startup along with providing a SEO benefit. Every re-tweet, share, like, mention, etc., is referred to as a social signal, and these signals are an important component of a successful SEO plan. A full time social media manager or agency might not be in the budget but that doesn't mean the startups social presence must be neglected. I know of a start-up that would designate one employee as the "social king" for the day and they would be responsible for running all of the social accounts for the day. This included posting the new daily blog posts across the social profiles, interacting with their followers, and handling any customer support inquiries that came over via social media. They were starting out on a shoestring budget but got creative and made it work. Launch a Blog & Keep it Updated With Fresh Content Every startup should have a blog on their website and it should be updated on a regular basis. A simple way to get good content for the blog is to source it from within the organization. In the beginning have one employee manage the blog and delegate writing assignments throughout the company. Employees of a new startup should have no objection to contributing a weekly blog post, as it will help with the growth and success of the startup. Assigning blog topics that are based around keywords that the startup is going to target for SEO is a great way to help get some quality content posted that can benefit the search engine optimization effort. Guest Blogging is NOT Dead When Done Correctly Look for industry blogs that have potential to get provide the startup with exposure and traffic and then pitch them guest posts. Again, this can be spread out through the startup at first. Have a contest that rewards the employee who obtains the most guest posts and reward the employee that creates the guest post that drives the most traffic back to the startups website. This kind of internal competition can produce great results while building work place camaraderie, something that is very important for a new startup. When I was speaking with Weston Bergmann of BetaBlox we also discussed guest blogging and he had this to add: "Recently I've heard a lot of people say that guest blogging is dead. Well it's not. What's dead is spammy and manipulative link building techniques. What's more important than ever is high-quality guest blogging and thought leadership. If you're sharing high quality and exclusive content you'll be rewarded, not punished. Also, guest blogging shouldn't be a one-and-done thing; aim to write for the same publication multiple times." Once a startup experiences some growth it is then possible to hire an agency to handle the search engine optimization. In the meantime, the tips above can be used to kick start a SEO effort with a limited or even non-existent marketing budget. Want more free online marketing tips? Sign up for the Market Domination Media newsletter and receive online marketing tips delivered to your email every week. Visit here and enter your name and email to be added to the newsletter list.

1 note

·

View note

Link

Biden Takes On Sagging Safety Net With Plan to Fix Long-Term Care President Biden’s $400 billion proposal to improve long-term care for older adults and those with disabilities was received as either a long overdue expansion of the social safety net or an example of misguided government overreach. Republicans ridiculed including elder care in a program dedicated to infrastructure. Others derided it as a gift to the Service Employees International Union, which wants to organize care workers. It was also faulted for omitting child care. For Ai-jen Poo, co-director of Caring Across Generations, a coalition of advocacy groups working to strengthen the long-term care system, it was an answer to years of hard work. “Even though I have been fighting for this for years,” she said, “if you would have told me 10 years ago that the president of the United States would make a speech committing $400 billion to increase access to these services and strengthen this work force, I wouldn’t have believed it would happen.” What the debate over the president’s proposal has missed is that despite the big number, its ambitions remain singularly narrow when compared with the vast and growing demands imposed by an aging population. Mr. Biden’s proposal, part of his $2 trillion American Jobs Plan, is aimed only at bolstering Medicaid, which pays for somewhat over half the bill for long-term care in the country. And it is targeted only at home care and at community-based care in places like adult day care centers — not at nursing homes, which take just over 40 percent of Medicaid’s care budget. Still, the money would be consumed very fast. Consider a key goal: increasing the wages of care workers. In 2019, the typical wage of the 3.5 million home health aides and personal care aides was $12.15 an hour. They make less than janitors and telemarketers, less than workers in food processing plants or on farms. Many — typically women of color, often immigrants — live in poverty. The aides are employed by care agencies, which bill Medicaid for their hours at work in beneficiaries’ homes. The agencies consistently report labor shortages, which is perhaps unsurprising given the low pay. Raising wages may be essential to meet the booming demand. The Labor Department estimates that these occupations will require 1.6 million additional workers over 10 years. It won’t be cheap, though. Bringing aides’ hourly pay to $20 — still short of the country’s median wage — would more than consume the eight-year outlay of $400 billion. That would leave little money for other priorities, like addressing the demand for care — 820,000 people were on states’ waiting lists in 2018, with an average wait of more than three years — or providing more comprehensive services. The battle over resources is likely to strain the coalition of unions and groups that promote the interests of older and disabled Americans, which have been pushing together for Mr. Biden’s plan. And that’s even before nursing homes complain about being left out. The president “must figure out the right balance between reducing the waiting list and increasing wages,” said Paul Osterman, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Sloan School of Management who has written about the nation’s care structures. “There’s tension there.” Elder care has long been at the center of political battles over social insurance. President Lyndon B. Johnson considered providing the benefit as part of the creation of Medicare in the 1960s, said Howard Gleckman, an expert on long-term care at the Urban Institute. But the chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, Wilbur Mills, warned how expensive that approach would become when baby boomers started retiring. Better, he argued, to make it part of Medicaid and let the states bear a large chunk of the burden. This compromise produced a patchwork of services that has left millions of seniors and their families in the lurch while still consuming roughly a third of Medicaid spending — about $197 billion in 2018, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. By Kaiser’s calculations, Medicaid pays for roughly half of long-term care services; out-of-pocket payments and private insurance together pay a little over a quarter of the tab. (Other sources, like programs for veterans, cover the rest.) Unlike institutional care, which state Medicaid programs are required to cover, home and community-based care services are optional. That explains the waiting lists. It also means there is a wide divergence in the quality of services and the rules governing who gets them. Although the federal government pays at least half of states’ Medicaid budgets, states have great leeway in how to run the program. In Pennsylvania, Medicaid pays $50,300 a year per recipient of home or community-based care, on average. In New York, it pays $65,600. In contrast, Medicaid pays $15,500 per recipient in Mississippi, and $21,300 in Iowa. This arrangement has also left the middle class in the lurch. The private insurance market is shrinking, unable to cope with the high cost of care toward the end of life: It is too expensive for most Americans, and it is too risky for most insurers. As a result, middle-class Americans who need long-term care either fall back on relatives — typically daughters, knocking millions of women out of the labor force — or deplete their resources until they qualify for Medicaid. Whatever the limits of the Biden proposal, advocates for its main constituencies — those needing care, and those providing it — are solidly behind it. This would be, after all, the biggest expansion of long-term care support since the 1960s. “The two big issues, waiting lists and work force, are interrelated,” said Nicole Jorwic, senior director of public policy at the Arc, which promotes the interests of people with disabilities. “We are confident we can turn this in a way that we get over the conflicts that have stopped progress in past.” And yet the tussle over resources could reopen past conflicts. For instance, when President Barack Obama proposed extending the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 to home care workers, which would cover them with minimum-wage and overtime rules, advocates for beneficiaries and their families objected because they feared that states with budget pressures would cut off services at 40 hours a week. “We have a long road ahead of passing this into law and to implementation,” Haeyoung Yoon, senior policy director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, said of the Biden proposal. Along the way, she said, supporters must stick together. Given the magnitude of the need, some wonder whether there might be a better approach to shoring up long-term care than giving more money to Medicaid. The program is perennially challenged for funds, forced to compete with education and other priorities in state budgets. And Republicans have repeatedly tried to curtail its scope. “It’s hard to imagine Medicaid is the right funding vehicle,” said Robert Espinoza, vice president for policy at PHI, a nonprofit research group tracking the home care sector. Some experts have suggested, instead, the creation of a new line of social insurance, perhaps funded through payroll taxes as Social Security is, to provide a minimum level of service available to everyone. A couple of years ago, the Long-Term Care Financing Collaborative, a group formed to think through how to pay for long-term elder care, reported that half of adults would need “a high level of personal assistance” at some point, typically for two years, at an average cost of $140,000. Today, some six million people need these sorts of services, a number the group expects to swell to 16 million in less than 50 years. In 2019, the National Academy of Social Insurance published a report suggesting statewide insurance programs, paid for by a dedicated tax, to cover a bundle of services, from early child care to family leave and long-term care and support for older adults and the disabled. This could be structured in a variety of ways. One option for seniors, a catastrophic insurance plan that would cover expenses up to $110 a day (in 2014 dollars) after a waiting period determined by the beneficiary’s income, could be funded by raising the Medicare tax one percentage point. Mr. Biden’s plan doesn’t include much detail. Mr. Gleckman of the Urban Institute notes that it has grown vaguer since Mr. Biden proposed it on the campaign trail — perhaps because he realized the tensions it would raise. In any event, a deeper overhaul of the system may eventually be needed. “This is a significant, historic investment,” Mr. Espinoza said. “But when you take into account the magnitude of the crisis in front of us, it’s clear that this is only a first step.” Source link Orbem News #Biden #care #Fix #longterm #Net #Plan #safety #Sagging #Takes

1 note

·

View note

Text

How the James Beard Foundation Failed the Most Prestigious Restaurant Awards in the Country

James Beard Foundation CEO Clare Reichenbach at the 2018 James Beard Media Awards | Photo by Noam Galai/Getty Images

The foundation violated its own ethics rules to ensure that award winners fit into its new narrative of progress and social justice

Finalists had been announced. A virtual ceremony had been planned. Acceptance speeches had been filmed.

Then, in late August, the James Beard Foundation abruptly announced that it was effectively canceling its Restaurant and Chef Awards, widely considered the most prestigious accolades in the American restaurant industry, not just this year, but until 2022.

The annual black-tie gala for these awards — a multimillion-dollar production that some have referred to as the Oscars of the restaurant industry, with big-name sponsors like San Pellegrino, All-Clad, American Airlines, and Capital One — had already been delayed and moved online due to the coronavirus pandemic. The foundation blamed this dramatic pullback on the pandemic as well. “Considering anyone to have won or lost within the current tumultuous hospitality ecosystem does not in fact feel like the right thing to do,” CEO Clare Reichenbach stated in a press release.

A few days later, New York Times restaurant critic Pete Wells reported that the James Beard Foundation had not been entirely forthcoming about the reasons for its decision. Around the time of the announcement, the foundation had quietly appended a note to the nominee list, claiming that several nominees had “withdrawn their nominations for personal reasons.” But, according to Wells, the foundation had in fact deemed some too “controversial” and asked them to withdraw “because new allegations about their personal or professional behavior had surfaced over the summer.”

Most striking, however, was the revelation that “no Black people had won in any of the 23 categories on the ballot,” despite multiple Black nominees and semifinalists — a result that, as Wells noted, “would not have been a first for the James Beard awards.”

Over the decades of their existence, the awards have struggled to be inclusive and representative of the diversity of America’s restaurants and chefs, and the foundation has only recently begun to address and rectify these issues.

In short, according to Wells, the James Beard Foundation found itself with a list of award winners that was incompatible with its recent attempt to reposition itself as a vanguard for social justice causes within the restaurant industry. This seemed particularly untenable in the wake of this summer’s Black Lives Matter movement — which has sparked an ongoing reckoning, not only across the restaurant industry and food media, but among the foundation’s own staff. Instead of being transparent about these issues, the foundation decided to sidestep them by canceling the awards.

As someone who has been involved in the James Beard awards process for more than a decade, I was shaken by these allegations, and undertook my own inquiry. A series of correspondences with members of foundation’s leadership, as well as conversations with others within the award process and restaurant industry, seem to confirm Wells’s reporting — namely, that the foundation tried to take a shortcut to virtue by manipulating the results of this year’s awards, and has been trying to cover it up.

I believe that, motivated by the desire to keep sponsorship and donor money flowing, employees of the foundation violated its own longstanding ethics and procedures to avoid a possible public backlash over the award winners. Rather than trying to devise an equitable path forward, these employees attempted to manipulate the results after the fact, hoping to create a superficial appearance of diversity and wholesomeness without doing the work of achieving this in a meaningful way.

As a result, the foundation disenfranchised committee members, voters, and restaurants — many of which desperately needed the boost that an award might have given their businesses during a pandemic — and corrupted the integrity of the awards. This threatens to render what is widely considered America’s most respected measure of culinary excellence — one that can be a platform for greater equity — meaningless. To let that happen would not merely be a professional failing on the part of an organization that is ostensibly a beacon and guardian of the hospitality industry, but a profoundly moral and ethical one.

Established in 1983 to honor the “dean of American cookery,” the James Beard Foundation is a nonprofit organization whose stated mission is to “celebrate, nurture, and honor chefs and other leaders” in America. Over the years, it has added initiatives that focus on sustainability, scholarship, and inclusion in the restaurant industry.

Despite its issues-driven programming, the foundation’s Restaurant and Chef Awards have become both its crown jewel and cash cow. Perhaps because of this, many believe the selection process is a conclave of cloistered agreements, favoritism, and pay-for-play among industry cardinals. It was not designed that way. Though the system may seem convoluted, it was in fact devised to ensure as much transparency and impartiality as possible, largely in response to a prior scandal.

In the mid-aughts, the foundation was left in disarray after gross mismanagement by then-president Leonard F. Pickell Jr. He was caught embezzling foundation funds, pled guilty to larceny, and served time in federal prison. The cleanup was expensive — at least $750,000 in attorneys and accountant fees — and the nonprofit found itself in a financial free fall as donations, its primary source of revenue, quickly dried up.

The foundation realized that in order to regain the trust of the public — and its donors — it needed to reform. Among numerous policy changes, a key component of its rehabilitation required divorcing the award process from the foundation’s operations. The committee overseeing the awards, which is composed of unpaid volunteers, was hermetically sealed off to guard against undue influence from the foundation and its employees.

One of the chief fears was that chefs and restaurateurs might feel pressured to perform favors for the foundation to increase their chances of winning an award. For instance, a centerpiece of the foundation’s programming is the dinner series it hosts at the James Beard House throughout the year, which features guest chefs from across the nation. Being invited to cook at one of these pricey, ticketed events is generally perceived to be an honor, but it requires the visiting chef to shoulder much of the associated costs (the food they’re cooking, as well as travel to the event, among other expenses), making participation tantamount to donating thousands of dollars to the foundation, and therefore a privilege accessible only to the best-capitalized chefs. (If it’s unclear which way the largesse flows, while the chefs gain exposure and a measure of pride, the information page for guest chefs helpfully points out that “events such as yours are an important source of revenue for the Foundation.”)

Given the obvious potential for quid pro quo, it was deemed vital to the integrity of the awards that foundation employees had no part in the award process. To underscore this imperative, the foundation agreed to a set of policies and procedures that removed the awards from its reach, and placed them under the management of an independent committee of financially disinterested volunteers.

This umbrella awards committee oversees six separate subcommittees, each one responsible for a different set of awards: Leadership, Books, Restaurant Design, Broadcast Media, Journalism, and the best known, the Restaurant and Chef Awards. It is the annual gala for this last set of awards, traditionally held in May, that is the glittering, red-carpet ceremony that most associate with the James Beard Foundation’s awards.

The committee that oversees the Restaurant and Chef Awards is composed of 20 members: eight at-large members and 12 regional representatives, each representing one of the committee’s 12 geographic regions. To ensure a degree of impartiality, these committee members do not work in the restaurant industry; many are journalists. Each regional representative on the committee impanels 25 judges in their region to provide perspective on and knowledge of America’s restaurant community at the local level. Like all committee members, judges serve voluntarily and are not paid. (The sole perks of monetary value are an annual membership in the foundation — normally $150 — and a ticket to the awards ceremony, which was valued at $500 in 2019.) Here is where you will find me, at the bottom of the awards pyramid, where I have served as a judge in the Midwest region for 14 years.

The award process is initiated by the committee late in the preceding year, when judges are solicited for nominations and input. Over the following months, the committee holds a series of closed-door sessions to determine the semifinalists for that year’s awards. The resulting list of 20 candidates in each award category is usually published in February. These semifinalists are balloted and sent to the voting body, which consists of the committee members, regional judges, and all past Restaurant and Chef Award winners. The initial round of voting whittles the nominees down to five finalists per category, who are usually announced by late March. A second, final vote is conducted to determine the winners.

The results of this voting process are tabulated by Lutz & Carr, a third-party accounting firm that represents over 400 nonprofit organizations. According to foundation policy, Lutz & Carr is required to keep the results of the first vote confidential until the second ballot; the results of the final vote must remain confidential until they are announced at the award ceremony. To prevent tampering, vote manipulation, or the results from leaking, no one within the foundation is supposed to be privy to this information before it is made public. For similar reasons, the committee members are bound by nondisclosure agreements.

This year, it appears that the foundation violated these policies by illicitly obtaining the results of the final round of voting before they were announced. Dissatisfied with the slate of prospective winners, according to a follow-up story by Wells, the foundation tried to change the outcome by proposing to alter the composition of the voting body and holding an unprecedented revote. By removing past winners — a voting bloc that is traditionally dominated by white, male chefs — from the revote, the foundation hoped that a revote might yield a set of awards more compatible with the narrative of inclusion it has been trying to tell about the awards.

This raised red flags within the committee, which pushed back on the foundation’s proposal, saying, according to Wells, that it “compromised the integrity of the awards.” A revote never happened. But the foundation did not let this aborted revote go to waste: In the following weeks, it relied on the proposal of a revote to claim that it had no knowledge of the winners.

In public statements, as well as in emails to the committee, nominees, and me, members of the foundation’s leadership have adamantly denied knowing who the winners are. However, through my correspondence with foundation employees (which can be viewed in full here), it became clear that these denials have been purposely misleading.

In an email to me, Alison Tozzi Liu, the foundation’s vice president of marketing, communications, and content, wrote, “In reality, the lack of diversity in the original vote in May, and the eventual decision not to hand out individual Awards in August were not related. As previously mentioned, there was to be a revote with eligible nominees and therefore no-one had knowledge of the ultimate winners.”

This statement reveals a number of things. First, it suggests that the foundation did know who the winners were, because Tozzi Liu is claiming that the lack of diversity among them did not affect the decision to cancel the awards. Second, her wording indicates that these denials, thus far, have been cleverly worded to appear as denials of knowing the original outcome, when in fact, they are denials of knowing who would have won had there been a revote.

This sleight of hand relies on a revote having been considered, which Tozzi Liu attempts to legitimize by claiming that “the full Restaurant and Chef Subcommittee had agreed to the revote.” However, it is clear from Wells’s reporting that this is false.