#and growing up in a sub-saharan african country in late childhood

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

posts that will get me hash tag cancelled (maybe) but these sorts of posts are really interesting to me bc i grew up in a heavily muslim country. i know what it means bc it was just part of the vernacular where i was. i am not immune to cultural appropriation, of course, but when does existing adjacent to a culture become part of your culture? I ask myself that question a lot and random little things like this niggle it.

#its just interesting#once again some of my intersections with autism and race in my early childhood#and growing up in a sub-saharan african country in late childhood#has really impacted how i think about race and culture...#this isn't a what about MEEEE ism it simply prompted musing. op's critique is apt and needed#and i made my own post bc this would be really annoying to add to op's post. anyway (peace signs and fades out)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mediterranean Medley: The Jewish Community of Tunisia

Tunisia is currently making global headlines. A decade ago the Tunisian protest for democracy sparked the “Arab Spring”, which led to vast political shifts in the Middle East. Now, its citizens are fighting to retain their past achievements and curb the ruler's authoritarian pursuits.

The recent events in this small country on the southern shore of the Mediterranean also provide an opportunity to discuss its Jewish community, a community small in numbers yet incredibly diverse in terms of socio-economic status and cultural orientation. This entry is therefore dedicated to exploring the complex history of the community, including the particularly tragic chapter of the Nazi occupation during the Second World War. As always fiction and culinary elements will be weaved into the discussion.

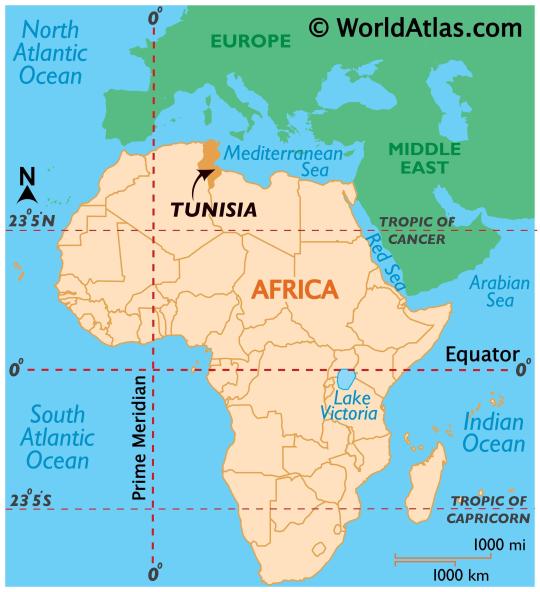

(Tunisia on the map: between Africa and Europe)

Berber, Italian and French Mix

The Jewish community of Tunisia settled mostly in the coastal areas in the cities of Tunis, Sousse, Sfax, Bizerte and Monastir. There were also several rural Berber communities, in which Jews lived a semi-nomadic life.

(The beautiful coast)

The origin of the Jewish community is disputable. Members of the community claim the first settlers migrated from Jerusalem after the destruction of the second temple in 70 CE. Several scholars, however, ascertain that the community originated from the conversion of either Phoenicians or Berber tribes.

Origin aside, archeologists indicate a viable Jewish presence beginning in the fourth century CE. Evidence also shows connection between Tunisian Jews and Jewries in Persia, Israel and Iraq. The Bagdadi community and its Talmudic centers, in particular, was a source of inspiration fueling the local Torah learning, and overall intellectual life.

In the fifteenth century, Andalusian Jews found refuge in Tunisia while escaping the Spanish Inquisition. Their influence is notable in architecture, culture, and clearly cuisine. Another wave of Jewish immigrants arrived to Tunisia from the Italian port city Livorno during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The Livornese Jews, mostly Portuguse Marrano descendants, built maritime trade between North African hubs to European Mediterranean port cities. In 1741, the Livornese community (also called “Grana”) asked for autonomy on the pretext of having a different liturgy. Followed by this act, two separate communities- native and Livornese- were formed. The two sub-communities had their own rabbis, synagogues, cemeteries and philanthropies. The Livornese section, which actually encompassed all European Jews whether they came from Italy, France, Gibraltar or Malta- prided themselves as superior. They refrained from intermarrige with the native Jews, refused to speak Judeo-Spanish and continued speaking Italian. Some of the Livornese became rich bankers and merchants, but many were weavers, tailors, shoemakers, and even lived in poverty relying on charities.

In the cities, since Medieval times, the indegenous Tunisian Jews, lived in the margins of the Muslim areas and the Souks, in quaters named Haras. The Haras became overpopulated starting in the second half of the nineteenth century with poor sanitary conditions, and no running water nor electricity. The residents of the Hara were mostly craftsmen- tailors, potters, leatherworkers and silversmiths. Those who could afford it, left the Hara to settle in the European quarters built by the French.

(The Hara of Tunis, image #1)

(The Hara of Tunis, image #2)

The French Colonization, starting in the late nineteenth century, created a new elite of Francophones. The upper Jewish class eagerly fostered French as their mother tongue, named their children in French names and sent their children to schools in Paris. The few, who managed to obtain key posts in the new colonial governments, were granted French citizenship, but the majority including some of the wealthiest families remained with the status of subjects.

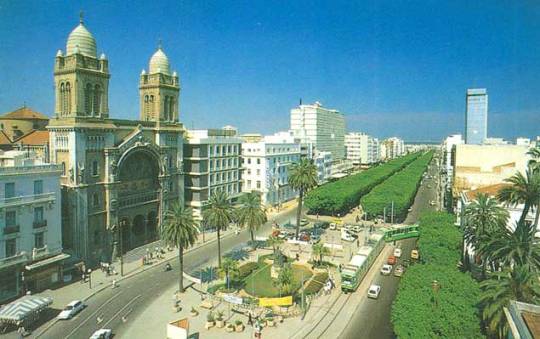

(The French Quarter of Tunis)

Despite the strong French influence, Tunisia continued to be fairly diverse as a port country luring people from different parts of the Mediterranean basin. Thus, the Jewish population (unlike their brothers in neighboring Algeria) lived in a multicultural environment, in which Greeks, Maltese, Italians and of course Arabs co-existed and influenced one another.

A Boy in a Ruthless City: The Nazi Occupation through the Eyes of an Adolecent

The cosmopolitan climate described above was the setting of Albert Memmi’s (1920-2020) semi-autobiographical novel, The Pillar of Salt. In the book, Memmi, a distinguished philosopher known for his work on Colonial Studies, disguised himself as Alexandre Mordekhai Bennillouche, a poor Jewish boy growing up in the Hara of the capital, Tunis.

( Albert Memmi)

Bennillouche (or Memmi) begins his account in describing his happy childhood as an age of innocence and unawareness to his poverty and inferior status as a “native Jew”. Gradually, the protagonist discovers the world around him. He excels at school, but suffers from anti-Jewish violence from Chirsitan and Muslim peers. Given his academic performance, he is given a stipend to study in one of the city’s top schools, where he is introduced to the upper circles of the Jewish community and the general European society. This exposure causes a rift in the relationship with his parents, who resent his education wishing for him to continue the family leather business. Although deeply ashamed of his parents - their meager existence and traditional views- Bennillouche is quickly disillusioned from the enchantment of the elite. Being a critical thinker, he spots its insincerity and snobbery, yet he is forced to hide his contempt as he is dependent on their funds for his schooling.

(The capital- Tunis)

The six month Nazi occupation of Tunisia (November 1942- May 1943) reaffirms Bennillouche’s beliefs about the hypocrisy of the elite. During the short- yet traumatic - German presence, Tunisian Jews were subject to constant harassment from the occupiers and general population, and were under the imminent threat of being deported to the death camps in Europe. Yet, the degree of Jewish misery varied based on socio-economic belonging. When the Germans issued a decree for Jewish forced labor, the wealthy ones of the community paid ransom to exempt themselves and their dear ones. Impoverished men- however- were destined to greater hardship.

(Jews assigned for forced labor)

Benillouche (and Memmi himself) was one of the unfortunate people. Despite being friendly with people in high places, and holding a prestigious teaching position, he was deported to a concentration camp in the Saharan desert. There, he suffered from the brutality of the guards, the senseless work, and above all the merciless sun. However, camp was also a place of revelation. The hardship created a sense of comradery between Benillouche and his fellow inmates, of whom he shared similar upbringing. He was even reunited with some old friends, and enjoyed conversing with them in his childhood dialect of Judeo- Arabic, which he neglected in favor of French. In addition, the camp helped him to rediscover and reconnect to his Jewish roots, as he was asked to lead Shabbat prayers as the camp’s intellectual figure.

By the time the camp was released by the Allies, Bennilouche was a more grounded man. He still continued to march according to his original trajectory in the academic world but with a wiser outlook on life.

Topped with Harissa: A Quick Peek to Jewish-Tunisian Cuisine

Even while estranged from his family traditions, Bennilouche always maintained a fondness for his mom’s traditional Tunisian cooking. In fact, he recounts nostalgically the smells of Shabbat dishes cooking slowly in the tiny kitchen of his childhood home. When he matures, he recognizes the power of food as a source of comfort and festivity in a household that is poor and filthy. One of the dishes he highlights is Bkeila (also pronounced Pkeila) - a hearty spinach and beans stew served vegetarian or with beef. Below is Yotam Ottolenghi’s take on it from his latest cookbook Flavor.

Bkeila, Potato and Butter bean Stew - Adapted from Flavor

(See my notes below to simplify the cooking process)

4 cups (80 gram), roughly chopped cilantro

1 ½ cups (30 gram) parsley

14 cups (600 gram) spinach

½ cup (120 ml) olive oil

1 onion (150 gram), finely chopped

5 garlic cloves, crushed

2 green chiles, finely chopped and seeded

1 tbsp plus 1 tsp ground cumin

1 tbsp ground coriander

¾ tsp ground cinnamon

1 ½ tsp superfine sugar

2 lemons: juice to get 2 tbsp and cut the remainder into wedges

1 qt/ 1L vegetable/ chicken stock

Table salt

1 Ib 2 oz/ 500 gram waxy potatoes, peeled and cut into 1 ¼ inch pieces

1 Ib 9 oz/ 700 gram jar or can of butter beans, drained

1.In batches, put cilantro, parsley and spinach in a food processor until finely chopped. Set aside.

(Massive amounts of greens)

2.Put 5 tbsp of olive oil into a large heavy-bottomed pot on medium heat. Add the onion and fry until soft and golden, mixing occasionally (about 8 minutes). Add garlic, chillies and all the spices and cook for another 6 minutes, stirring often.

3.Increase the heat to high and add the chopped herbs and spinach to the pot along with the remaining 3 tbsp olive oil. Cook for 10 minutes, stirring occasionally until the spinach turns a dark green. The spinach should turn a little fried brown but not burn. Stir in the sugar, lemon juice, stalk and 2 tsp salt. Scrape the bottom of the pot if needed. Bring to a simmer, then decrease heat to medium and add the potatoes. Cook until they are soft for about 20-25 minutes and then add the butter beans and cook 5 minutes longer.*

(Butter beans to break the deep green)

4.Divide into bowls and serve with lemon wedges.**

* As this dish was traditionally slow cooked using a slow cooker pot or a pressure cooker could easily do the trick. If using these- do the following: Skip step 1. Saute the onions, garlic, chilli and species as instructed in step 2. Then add the rinsed spinach and herbs. Mix them well with the onions and spices in the bottom. Once the spinach begins to melt, mash them using a hand blender and then add the ingredients described in step 3 (beside the butter beans). Then let it slowly cook until everything softens. In the end, add the butter beans and press on the “stay warm” button.

(loading the pot with spinach)

** I served it with bulgur to soak up the liquids a bit (rice, farro or any other grain will work as well). I also added hard boiled eggs for additional protein.

(Healthy and heart)

In addition to the Bkeila- The Tunisian Shabbat table will not be complete without the famous couscous. The process of making it from scratch without a food processor was quite laborious, but the result - whether served sweet with nuts and spices, or savory with meat stew or fish - was considered a delicacy.

The proximity to the Mediterranean shore brought fish dishes to the Jewish- Tunisian repertoire. Fish is mostly eaten fried or cooked as fish balls or oven roasted served with red hot sauce. Meat is also often served spicy, and often chunks of hot merguez sausage are added to stews or shakshuka.

Generally speaking, Tunisian Jews are fond of hot flavors, and their cuisine is potentially the spiciest in the diaspora (perhaps only second to the Yemeni). Harissa paste, now increasingly popular around the world - is liberally used to spice up any dish. This fiery red pepper condiment is added - for example- to the famous Tunisian fricassee, one of Israel's most popular street foods. Click here for a recipe for this tuna loaded sandwich, and here to learn more broadly about Tunisian cuisine.

(Tunisian Sandwich with some Harissa)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recording with Pendo & Leah Zawose and Wamwiduka in 2019 and 2020

Part 1: British Council Trip February 2019

Having spent a small but influential portion of my childhood in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, I was over the moon to be returning to take part in a music production and education project set up by the British Council. I’d be going out into the heat of sub-Saharan summer with accomplished guitarist, fellow music producer and regular collaborator, Tom Excell, to be part of a project I’d been dreaming about for 15 years. I held such fond memories of Tanzania; remembering street corners piled high with infinitely juicy oranges, the lush smell of a tropical climate next to the Indian Ocean, and the warm smiles of the Swahili people, always welcoming with cheeky curiosity. Exiting the airport I felt a strong sense of home wash over me as these thoughts returned to me expectantly.

I was excited to meet the musicians we knew so little about, that would soon change not only my perception of rhythm, but my outlook on what it means to write music from the soul. I discovered that writing and performing music for these particular Tanzanians isn’t so much a creative endeavour or choice, but a necessity. An unstoppable thirst for creative expression that defines they way that they live.

Our roll call was at 10am the morning after we arrived, but with Tom suffering from a mild bout of yellow fever (as a reaction to the jab he had had a few days before) I timidly arrived by myself at Nafasi Arts Space in the Mikocheni area of Dar es Salaam. Aziza Ongala, the creative brain behind the project, arranged us in a circle on the dusty dance floor of the outdoor space for an introductory meeting. There were the four boys in Wamwiduka band, all in their early twenties and wearing trendy clothes - purposefully ripped jeans, slogan T Shirts and a combination of beaded, dreaded and threaded hair that oozed style. None of them spoke more than a few words of English and with my Swahili embarrassingly bad, our introductions were limited to a thumbs up, smiles and hand slap thumb click combo that would be become the standard greeting. The Zawose sisters were next; Pendo & Leah, accompanied by Pendo’s 11 month old son, introduced themselves with a few words in Swahili that were translated for my benefit - they were excited about our collaboration, and had an open mind coming in to the project. Music to my ears! I fumbled a similar introduction for myself that was translated into Swahili, sweating in the 30 degree heat.

Having done a small amount of research beforehand, I had discovered that Pendo was the daughter, and Leah the granddaughter of the late Dr Hukwe Zawose of the Gogo tribe from central Tanzania. Hukwe had found fame with Real World records in the 90s singing and playing traditional instruments such as the illimba (a large thumb piano), zeze (similar to a kora as found in west Africa) and chizeze (similar to a violin). He had supported Peter Gabriel as part of his Growing Up world tour, and become a beacon of East African music when ‘world music’ was getting a first wave a recognition among western audiences. He brought the Zawose family to the UK for the 2000 WOMAD Festival, and released three albums with the label before his untimely death in 2003 from AIDS. Dr Zawose was highly regarded in his own country too, performing for the then President Julius Nyerere under whom Tanzanian arts and culture flourished. He started the Bagamoyo College of Arts in his home town and taught his large family (which consists of 7 wives and 14 children) how to play the music of the Wagogo. Later on I found out that Pendo’s brother, Charles Zawose, had become the de facto band leader when Hukwe had died, but in tragic circumstances Charles was also to succumb to AIDS only a year after his father. The family still perform occasionally, but their days of making a living as a large travelling music troupe are over. In this moment, we realised that Pendo & Leah have an opportunity to take the torch for their family legacy - not only as incredibly talented multi-instrumentalists and singers, but also as women, breaking the mould of their family’s patriarchal past. Their music is psychedelic in parts - motifs repeated with entrancing effects, topped with powerful voices in harmony, and intricate poly-rhythmic drum and percussion parts that bring an upbeat energy. As our relationship with them and their music developed, we realised how important it was to give these women a platform equivalent to the men in their family, and raise the profile of the Zawose name once again.

Wamwiduka tell a different story. The young men are from a small village just outside Mbeya, itself a small town in the far south west of Tanzania. The band consists of Brown as lead singer and banjo player, Peter on shakers and backing vocals, Matcha on a hand bass drum, and Zacharia on babatone, a large homemade instrument resembling something not too far away from an upright bass. The story goes that Brown, devoted to being a musician from a young age, learned to play the banjo from his father, as well as how to build the instrument out of a sauce pan and cow hide, with cycling brake wire for strings. On the daily long walk to gather water for his family, Peter would accompany him, begging him to let him learn too so they could perform together. Peter made his shakers from coffee tins with seeds inside and hand carved wooden handle, developing a highly intricate and energetic performance style. Later Zacharia and Matcha joined, forming a band that would get their whole village dancing on street corners as they honed their craft. Once old enough, they decided to leave the village and travel the 850km across the country to Dar es Salaam, where they stood a chance of making it as professional musicians. With just their instruments on their backs, they would busk in towns along the way to collect enough money for the bus fare to get to the next town, or hitch rides wherever possible. Their heady mix of upbeat banjo-led 3 chord progressions, fast syncopated drums, and 2- and 3-part harmony instantly puts you on your feet, conjuring feelings of island life and care-free joy. Upon arriving in Dar es Salaam, they gigged relentlessly until noticed, building up a reputation as one of Tanzania's most exciting contemporary young bands.

So it was with this knowledge that we set out in February 2019 to form a supergroup band consisting of the Zawose women, the four young men in Wamwiduka, Kenyan musicians Ambassa Mandela & Dunga, myself and Tom. We felt very fortunate to be involved and exposed to such inspired musicians, so decided to record as much of it as possible. During the project organised by Aziza (herself the daughter of Tanzanian music royalty, Remmy Ongala) we delivered 4 days of music production workshops in Dar es Salaam, and in Stone Town Zanzibar, as well as performing three 45 minute long sets of original material. On one down day, we took a memorable trip to Bagamoyo - the home of the Zawose women. We spent it on the beach swimming, dancing and laughing, but most importantly, jamming. It was here that I realised how important musical expression is to all of these musicians... they just did not stop! Here we were on our ‘relax’ day, having been rehearsing in a small hot room for 5 days straight, and there wasn’t a single moment in the day where someone wasn’t performing. Their thirst for music is unquenchable - they sing while waiting for the bus, dance across the beach, teach each other banjo while relaxing in the shade. They are singing about the plight of their people, love gained (never lost), and about their gratitude for the experiences they are having through music. There is something about this pure self-reflection and relentless positivity that is so different from western musical culture, and so uplifting. Even if you don’t understand the words, this spirit translates effortlessly through the music. I challenge anyone to listen and watch without a smile from ear to ear.

Our second and only other collective down day was in Zanzibar. We were all staying together in a typical Zanzibari guest house, complete with rooftop breakfast bar. It was on this rooftop, with its shaded area and view of Stone Town ferry port that we built a small recording setup using the equipment we were touring with. By this time I had gotten used to recording East Africa style - with 10 microphone cables of which only 5 worked, and the imminent threat of the power cutting out at any moment - so I knew I had to be clever with my microphone choices and quick in order to capture it all. The Zawose women were downstairs in one of the rooms, writing with the help of Tom and Dunga, while I recorded a rousing 3 song performance from Wamwiduka. Their music is very high energy, and knowing that they are used to playing to excitable audiences I hit record and jumped around like a maniac on the rooftop while they were playing, to make up for the lack of crowd. My questionable ‘mzungu’ dancing got a good few laughs in between the songs and I think we managed to capture their energetic performance.

Next up were the Zawoses who had written their first ever pair of songs. We couldn’t believe it, but such is the strength of the family patriarchy, that the women were never encouraged to put forward their own compositions for performance with the family. The first song, Sauti Ya Mama, was about Pendo's new role as the mother of a son. Baby Yussufu was with us on the trip and just before coming up to the rooftop to record the song, Pendo had been breastfeeding. It felt like the perfect time to record such a personal song, with Yussufu just out of sight but certainly not mind. Tom joined on guitar and a performance was recorded with two illimba thumb pianos and the voices live, with the sound of the nearby port bleeding into the background. As their act is made up of just the two of them, we decided to record some extra drum and percussion parts over the top to give the performance more energy. I watched how Pendo played the ngoma (drum) on every single beat that I did not expect her to play, and missed out every beat my western trained rhythmic brain had expected. All the while it felt like she was dancing simultaneously - a remarkable sight.

Part 2: Recording in Bagamoyo, February 2020

Once we had carried out all of our performances and the project for the British Council completed, Tom and I headed back to the UK. We spent the next 3 or 4 months sporadically working on the tracks we had recorded, adding subtle percussion and bass elements in order to make the production fuller, without taking away from the traditional aspects of the songs and performance. We resolved to return as soon as feasibly possible so we could complete full length recordings with the artists.

Towards the end of 2019, our plans started to come into fruition, and we enlisted the brilliant and enthusiastic help of Pepe Waziri in order to make it a reality. She conferred with the artists, acting as de facto manager for both groups, in a stroke of fortune Tom’s UK band Onipa had been booked to play at Sauti za Busara festival so would be in the area already during February 2020 already, and we felt like the opportunity to get out there and make these records had to be taken. We carried out meetings with UK based record labels specialising in releasing music from Africa, and they were enthusiastic about partnering to work with us on the project, giving us the guarantee of financial support to make it possible. We also received an extremely generous donation from Sue Huxtable, my old school headteacher in Tanzania that enabled us to pay for our initial costs. The next month was spent frantically organising all aspects of the trip - we decided that the location should be Bagamoyo so as to be close to the Zawose family, and found a pair of houses in a small cul de sac where we could stay and also record undisturbed. The Wamwiduka guys would travel from Dar es Salaam to be with us for enough time to record their album in a live setting, as we realised the Zawose record would involve more composition and potentially a deeper level of production. Once all aspects of the trip were in place, we booked our flights and were able to put more thought into the musical development of the project, listening to the music of Hukwe Zawose for inspiration.

We arrived and went straight from the airport to the house in Bagamoyo to meet Pepe and unload our equipment. We felt prepared technically, but with no real plan for how the music was going to play out. We had an incredibly tall order for the two weeks ahead, taking on the recording and partial writing of two entire albums - something that we would have spent months working on had it been done in the UK. Despite this, it all felt very immediate: the musicians seemed to have no lapses in energy or confidence, and we were able to keep up with the pace by working into the early hours each evening after the musicians went home. In order to break up the recording and give some variety to the sound, we decided to do some of the recording on the beach less than a mile from our house and home studio. We took Wamwiduka and a small portable setup with us in Pepe’s 7-seater car, setting up in a big fire pit at the back of the beach to avoid the wind. Wamwiduka performed around 8 songs in this setting as the sun went down, including an a cappella version of one of their songs, and a few that Brown sang without accompaniment. Once we had recorded and incredible 19 songs with Wamwiduka over the course of 3 days, we listened to them all as a group and chose the 12 that we felt best worked together to give the record variety and depth. What we’ve ended up with is a collection of performances that represents their sound completely - from the high octane songs as performed in their live set, to the more intimate performances where Brown’s rich voice tells stories of a life of struggle, and love for his companions.

The album with Pendo and Leah required a bit more planning and involvement on our part. On the first day, we were told that 4 songs had been written for the purpose of this recording, and a potential 5th existed as a collaboration with Leah’s father (also Pendo’s brother), known to us simply as Baba Leah. We were told he had played with Hukwe as part of his band, and specialised in the chizeze and zeze instruments which we had heard on Hukwe’s recordings. Setting out to record the songs already written, we helped develop them structurally and led the women through building up the production on the tracks bit by bit, making decisions as to what instruments might work on which songs as we went. We decided to keep some tracks in their bare forms, opting to maintain the traditional elements, but when it came around to writing new songs we started with an electronic beat that Tom or I programmed, in order to give Pendo & Leah a foundation to write on top of. They responded amazingly well to this - sometimes writing verses in a matter of a few minutes and being totally open to our ideas for the backing tracks. In total we wrote 4 songs from scratch in this way during our time with them. On two particularly special days recording with the Zawoses, Baba Leah graced us with his musical skill and enlightening company. We never asked his age, but his spirited performances belied his years and thin frame - proof that music really does keep the soul alive. His bright eyes lit up as soon as he started singing, and we found ourselves uncontrollably drawn to this experienced performer who had needed help getting out of the car, but could hop and skip around the room with ease when performing. We travelled with the Zawoses for a short recording session on the beach as well, only 50m down from where we had seen videos of Pendo’s late brother Charles make his final group performance before his sad death. It felt like such an honour to be entrusted with capturing their music - this music style that has been passed down for many generations through the Wagogo people.

Amazingly, on the day before we left, we were able to complete the recording for the Zawose’s album. 12 tracks in total that tell stories from the plight of their people, to feelings of collective hope in humanity. After making some video and photo content to use as part of the promotion, our job (for the time being) was done and we departed from Bagamoyo with our heads held high. Great friendships had been developed, as well as a huge amount of excitement for the next chapter of their story. A particularly special moment was when Peter, the shaker player in Wamwiduka, was leaving the Bagamoyo house. He shouted through the open window in his broken English ‘I love you guys, all so much’ with a huge grin spread across his face. It’s this completely genuine display of emotion and enthusiasm that fills the music of both groups, transcending language and borders to uplift the soul of anyone who listens. We really hope you enjoy it!

0 notes