#america was build with enslaved human labor

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Quote

A new civics training program for public school teachers in Florida says it is a “misconception” that “the founders desired strict separation of church and state,” the Washington Post reports. Driving the news: That and other content in a state-sponsored training course has raised eyebrows among some who have participated and felt it was omitting unflattering information about the country's founders, pushing inaccuracies and centering religious ideas, per the Post. The Constitution explicitly bars the government from “respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof." Scholars interpret the passage to require a separation of church and state, per the Post. In another example, the training states that George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were against slavery, while omitting the fact that each owned enslaved people.

Florida training program: "Misconception" that founders wanted separation of church and state

So ... DeSantis and his Fascist supporters want to just straight up lie to generations of children about the history of American violence, oppression, racism, and they are using the law to do that.

I���m speechless. I haven’t finished my coffee yet, and it’s early, but ... holy fuck. I am speechless.

#fuck republicans#teach the truth of america's racist history#the founding fathers all owned slaves#thomas jefferson was a rapist#george washington's false teeth were stolen from enslaved humans#america was build with enslaved human labor#teach the fucking truth you white supremacist christian nationalist fucks

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

In fact, far more Asian workers moved to the Americas in the 19th century to make sugar than to build the transcontinental railroad [...]. [T]housands of Chinese migrants were recruited to work [...] on Louisiana’s sugar plantations after the Civil War. [...] Recruited and reviled as "coolies," their presence in sugar production helped justify racial exclusion after the abolition of slavery.

In places where sugar cane is grown, such as Mauritius, Fiji, Hawaii, Guyana, Trinidad and Suriname, there is usually a sizable population of Asians who can trace their ancestry to India, China, Japan, Korea, the Philippines, Indonesia and elsewhere. They are descendants of sugar plantation workers, whose migration and labor embodied the limitations and contradictions of chattel slavery’s slow death in the 19th century. [...]

---

Mass consumption of sugar in industrializing Europe and North America rested on mass production of sugar by enslaved Africans in the colonies. The whip, the market, and the law institutionalized slavery across the Americas, including in the U.S. When the Haitian Revolution erupted in 1791 and Napoleon Bonaparte’s mission to reclaim Saint-Domingue, France’s most prized colony, failed, slaveholding regimes around the world grew alarmed. In response to a series of slave rebellions in its own sugar colonies, especially in Jamaica, the British Empire formally abolished slavery in the 1830s. British emancipation included a payment of £20 million to slave owners, an immense sum of money that British taxpayers made loan payments on until 2015.

Importing indentured labor from Asia emerged as a potential way to maintain the British Empire’s sugar plantation system.

In 1838 John Gladstone, father of future prime minister William E. Gladstone, arranged for the shipment of 396 South Asian workers, bound to five years of indentured labor, to his sugar estates in British Guiana. The experiment with “Gladstone coolies,” as those workers came to be known, inaugurated [...] “a new system of [...] [indentured servitude],” which would endure for nearly a century. [...]

---

Bonaparte [...] agreed to sell France's claims [...] to the U.S. [...] in 1803, in [...] the Louisiana Purchase. Plantation owners who escaped Saint-Domingue [Haiti] with their enslaved workers helped establish a booming sugar industry in southern Louisiana. On huge plantations surrounding New Orleans, home of the largest slave market in the antebellum South, sugar production took off in the first half of the 19th century. By 1853, Louisiana was producing nearly 25% of all exportable sugar in the world. [...] On the eve of the Civil War, Louisiana’s sugar industry was valued at US$200 million. More than half of that figure represented the valuation of the ownership of human beings – Black people who did the backbreaking labor [...]. By the war’s end, approximately $193 million of the sugar industry’s prewar value had vanished.

Desperate to regain power and authority after the war, Louisiana’s wealthiest planters studied and learned from their Caribbean counterparts. They, too, looked to Asian workers for their salvation, fantasizing that so-called “coolies” [...].

Thousands of Chinese workers landed in Louisiana between 1866 and 1870, recruited from the Caribbean, China and California. Bound to multiyear contracts, they symbolized Louisiana planters’ racial hope [...].

To great fanfare, Louisiana’s wealthiest planters spent thousands of dollars to recruit gangs of Chinese workers. When 140 Chinese laborers arrived on Millaudon plantation near New Orleans on July 4, 1870, at a cost of about $10,000 in recruitment fees, the New Orleans Times reported that they were “young, athletic, intelligent, sober and cleanly” and superior to “the vast majority of our African population.” [...] But [...] [w]hen they heard that other workers earned more, they demanded the same. When planters refused, they ran away. The Chinese recruits, the Planters’ Banner observed in 1871, were “fond of changing about, run away worse than [Black people], and … leave as soon as anybody offers them higher wages.”

When Congress debated excluding the Chinese from the United States in 1882, Rep. Horace F. Page of California argued that the United States could not allow the entry of “millions of cooly slaves and serfs.” That racial reasoning would justify a long series of anti-Asian laws and policies on immigration and naturalization for nearly a century.

---

All text above by: Moon-Ho Jung. "Making sugar, making 'coolies': Chinese laborers toiled alongside Black workers on 19th-century Louisiana plantations". The Conversation. 13 January 2022. [All bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me.]

#abolition#tidalectics#caribbean#ecology#multispecies#imperial#colonial#plantation#landscape#indigenous#intimacies of four continents#geographic imaginaries#indigenous pedagogies#black methodologies

464 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fascinating article in the NYT about the last two Shakers (gift link from Eric Conrad on bluesky). I've long wanted to write an FF historical romance about two women in the group. Beyond that, I think they're an important case in showing how *when* historical people were radically egalitarian it was in their own terms, not because they were somehow "modern" or "like us" -- they found their way to it using their own cultural tools.

Too many "historical" stories depict a historical person with egalitarian ethics as basically a person who thinks in "modern" terms - as if "modern" is the pinnacle of human beings (and which "modern" do we mean exactly?) given all the wrongs we're embedded in. It really sacrifices something important, which is realizing how truly different people can think even while trying for good ends.

Some neat quotes:

The youngest Shaker in the world is 67 years old, and his name is Arnold. He lives alongside Sister June, 86, in a magnificent brick building designed to sleep about 70 — the dwelling house of the last active Shaker village in the world, at Sabbathday Lake in Maine. Together they constitute one of the longest-running utopian experiments in America. It’s a triumph, as utopian experiments aren’t known for their durability, though the impulse — to start afresh apart from the mess of mainstream society, to reinvent society with like-minded people — has always been strong here. Out of the many that America has fostered, this is one of the most abiding. Out of the tens of thousands of Shakers who have lived out their faith in the last quarter-millennium, these two remain.

...The Shakers have been breaking bread in this manner since before the Revolutionary War. In 1774 a blacksmith’s daughter named Ann Lee led a small group of refugees from Manchester, England, where they had been jailed and beaten for following her heretical teachings: that God was both male and female, a Father-God and Mother-God. She taught that true virtue required sacrificing individual desires for the collective good, including total celibacy. She preached pacifism and the equality of the sexes and races. (Black Americans were welcomed as early as 1790, and communities purchased freedom for their enslaved members.) Her followers lived together in largely self-sufficient communal villages, everyone a brother and sister to one another. To join, prospective Shakers had to divest themselves of their worldly attachments — property, marriages, debts — and dissolve their families: Husbands would live with the brothers, wives with the sisters, and children would be raised separately by the brethren assigned to child care. Shakers believe their calling is to manifest the kingdom of God on Earth, and their Millennial Laws, first drawn up in the 1820s, specified that every detail of their built environment should express that vocation. They organized their lives around the belief that work is a vehicle for the divine: When early Shakers planed wood for a barn, or designed that barn, or sheared sheep, or rolled out a pie crust, they understood themselves to be worshiping. Every day, through their labor, the flawed world in which they lived could be made more whole.

Though it’s hard to get a precise count, at Shakerism’s height in the 19th century, the community numbered roughly 5,000. Over its history, 19 Shaker communities spread out from New England as far west as Ohio and south into Kentucky and Florida. Now some of the most tangible products of their philosophy — the furniture — are more well known than the religion itself. Their chairs are in the Metropolitan Museum of Art; knockoff replicas are sold in big-box stores. The traditional Shaker “aesthetic” is so popular that The New York Times’s Style section ran a 2022 feature on the influence of Shaker design on contemporary “tastemakers.” When I mentioned to a friend that I was writing about the Shakers, she replied, “Are those the furniture Christians?”

...Once, after supper, I asked Brother Arnold, “What makes a good Shaker?” He was in the recliner in the corner of the kitchen, looking at his phone. He told me about the willingness to labor, both physically and spiritually, in perpetuity. This is what it takes. Not everyone can do this work knowing that they might never see the fruits of their labor. “The idea that we need to see results in our lifetimes — that’s not how the Shakers actually teach us to think about those types of achievements,” Graham pointed out to me. “That’s man’s time, not God’s time.” Brother Arnold said to me more than once that Shakers live “in the eye of eternity.”

There are a lot of people around Sabbathday Lake striving to labor in the eye of eternity these days. Maybe a new Shaker will come this year; maybe not. But in the Meeting House this summer, people are singing. Lavender is drying from the eaves of the old sisters’ shop; future harvests will hang in the new herb house. A concept of survival and flourishing that isn’t primarily concerned with linear time or material gains may be the most radical thing about this historically radical American religion, and the one most resonant with a world that is experiencing, constantly, its own existential threats and calamities. It is obvious by now that everyone and everything is dying and living all at the same time, that failure and hope are all mixed up, and still the sheep are lambing and the roof has sprung a leak again and you’ve been snappish and petty even though you swore you’d be better and someone has to make breakfast and even breakfast can be a gesture of belief in the world as it could and should be.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Josh Kline’s installations for Climate Change at MOCA use a variety of different mediums to explore the environmental issues of today while focusing on a potential dystopian future.

From the museum-

Looking at our era through a lens of labor and class, Josh Kline (b. 1979, Philadelphia) speculates in his art on some of the most urgent issues facing the world in the coming decades. His largest body of work is an as-yet-untitled cycle of immersive installations, organized as chapters, that explores key political, economic, technological, ecological, and biological questions of the twenty-first century. Climate Change, gathered together for the first time at MOCA, is the cycle’s fourth chapter.

Climate Change is both an exhibition and a total work of art—a visceral suite of science-fiction installations that imagines a future sculpted by ruinous climate crisis and the ordinary people destined to inhabit it. Begun in 2018 and produced in sections over the last six years, the works in Climate Change were largely made during the COVID-19 pandemic and informed by events during those difficult years. In its profound disruption of ordinary life, the pandemic became, for Kline, a cipher for the looming climate catastrophe and unprecedented disruption of our lives that scientists predict will accelerate in the years ahead. Using dystopia as a point of entry rather than a diagnosis, he invites us to place ourselves within it and consider the rear view. What happens in a world where the systems built to sustain and extend capitalist enterprise and global hegemony melt down their own foundations? Is this the future that we want to live in? Can we build a new and more hopeful world from the ruins?

The images above are from Kline’s sculptural installation Personal Responsibility. Although set in the future, the rise of tent cities around the country today in combination with the need for temporary structures after recent destructive storms, make this work feel contemporary.

From the museum-

Personal Responsibility (2023-24), the core of Kline’s project Climate Change, is a sculptural installation set in the future, in the aftermath of climate disaster. Borrowing their forms from the temporary shelters used by refugees and migrants in the United States and around the world, the tentlike structures here serve as both home and workplace for “essential workers” — the individuals who will still have to physically go into work, often at great personal risk, while those in higher-paying jobs can work from home in comfort and safety.

The installation also features two sets of related videos. Capture and Sequestration (2023) centers four iconic commodities made from materials that powered America’s rise as the world’s preeminent military, economic, and cultural power: sugar, tobacco, cotton, and oil. Through these materials, it is possible to trace the lineage of human-made global warming and climate change back through America’s global empire and the industrial revolutions of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to the most painful parts of US history —the enslavement of Africans and the theft of Indigenous land. The other videos are fictional interviews with people living through catastrophic climate change in a future America. Although set decades from now, these videos are informed by extensive research into survivors’ experiences of climate-related disasters such as Hurricanes Katrina, Sandy, and Harvey and recent California wildfires. In visualizing and making relatable the forecasts of climate scientists, Kline raises questions about whether Americans are willing and able to work together to prepare for, and possibly mitigate, what is to come.

Below are images from Kline’s short film Adaptation (2019-2022).

From the museum about the work-

The short film Adaptation (2019-22) imagines a future Manhattan transformed by climate change and follows a team of relief workers at the end of their shift. Described by the artist as a “science fiction of ordinary life,” the film focuses on what tomorrow could be like for the working people who will clean up the inevitable mess resulting from the political and economic decisions of previous generations. The fictional workers of Adaptation survive by doing the kind of essential but poorly compensated, physically taxing jobs that society takes for granted.

Using primarily analogue special effects — scale models, miniatures, and matte shots-and 16mm color film instead of high-definition digital video, Kline creates an expressionistic science fiction that suggests a nostalgia for the present from the perspective of a future transformed by global warming. Although it was filmed in 2019, the work was completed during the pandemic, and its poetic voiceover and melancholy soundtrack, both added in 2020, quietly evoke the lockdown and quarantine in New York.

This exhibition closes 1/5/25.

#Josh Kline#MOCA#Art#Art Installation#Art Show#Art Shows#Climate Change#Dystopia#Environmental Art#Film and Video#Installation Art#Los Angeles Art Shows#Sculpture

0 notes

Text

Sydney Cleveland

11/02/2024

Dear future art educators,

This is a great class to take if you like to dive a little deeper into yourself and your interests. There are so many ways you can put your own personal touch on your assignments that bring you pride. The history of quilting is something I have always been interested in but never took the time to actually research. Like many Black Americans, I know little about my lineage and crave more knowledge about where my roots lie. But the art of quilting makes me feel closer to finding my roots.

A little background about me: I have a love for teaching not only fashion, but sewing and construction. It is truly a lost art and carries so much importance in human history. Sewing and construction is more than just trendy fast fashion, I discovered that it can be used to tell stories and advocate for important causes.

I worked at a non-profit for designers and artists and they opened a pop up on 125th. We had small fashion brands there, some home decor and other art, but hung up on the ceiling were these huge quilts. My boss handed me a paper listing their prices and my jaw dropped; of these quilts were over two thousand dollars! I was curious who would buy them and what made them worth the money. My more knowledgeable coworkers informed me of the deep roots that quilt making has had within the Black community. I was amazed by the history that I learned from a simple square piece of fabric. Over time, I have learned why they were valuable and desirable enough to be in a luxury store.

Dutch, English AND Africans brought their quilt making skills to America at the same time. This a fact that is often overlooked. Most articles only mention the English and Dutch settlers. Slaves were probably making most of these quilts since they did most handy work with textiles. Almost all of enslaved Africans history has been lost and under documented I think historians look over this fact.

The first quilts were rags made out of necessity. There is hardly any evidence that they even existed because they were worn down so badly. But people still found ways to use quilts creatively even if it was out of necessity. Some people made their deceased loved ones' clothing into a quilt. Slaves escaping to freedom used quilts as a visual queue to spot safe houses and as a map to guide themselves.

Quiltmaking started to evolve into a social activity to build community and gossip. People courted, gossiped and held political discussions over quilting. Susan B. Anthony discussed women's suffrage at these events. Eventually the people of Gee’s Bend (previously enslaved, black sharecroppers) turned their hard labor into profit and community even after they were isolated from the world due to their participation in the civil rights movement. They developed distinct quilting styles because the community was so isolated. Now their work is in museums.

During the civil rights era the use of quilts to protest and advocate for causes began to rise. Clement Bond advocated for self employment by selling quilts. Faith ringgold used her quilts for activism and to tell her story as a black woman from harlem. She has turned her quilts into published books, like Tar Beach. Her family has quilting roots dating back to slavery. Her mother was a fashion designer. I really identify with her work so much as a black woman, a designer and someone who is trying to be closer to their roots.

0 notes

Text

Free From Sin In Christ Jesus

Thank God! Once you were slaves of sin, but now you wholeheartedly obey this teaching we have given you. Now you are free from your slavery to sin, and you have become slaves to righteous living. Romans 6:17-18 One of the biggest black marks in American history came at the legalization of slavery. Slave owners forced those they owned to do all types of labor using abuse and other methods. A slave remained a slave even if they escaped from their master. The reason, because they had to continue running, always looking over their shoulder. Fortunately, America abolished slavery. Americans, however, paid a price to set the slaves free. It took the Civil War and the loss of many lives to free people from their bondage. A different type of slavery exists that has had people in bondage for centuries. Paul called it slavery to sin and told us how we can live a life free from it. We know slavery existed before the birth of Moses. The Egyptians forced the Israelites to make bricks and build cities for them. Taskmasters made sure they completed their jobs. The slave master of sin operates in just a little different manner. It offers things that aren't good for us and hard for us to resist. And we get to choose who or what we will serve. Don't you realize that you become the slave of whatever you choose to obey? Romans 6:16 I'm sure you've heard someone say something like this before, "I know I shouldn't do this, but..." Or maybe you've even said it yourself.

The Influence of Sin

Sin leads us to do things that make us feel good, regardless of how we make others feel. We often feel free to sin because we only think of the moment. We don't consider its eternal effect. You can be a slave to sin, which leads to death, or you can choose to obey God, which leads to righteous living. Romans 6:16 Sin's influence can cause a monster to arise within us that takes over in our lives. In other words, it makes a slave out of us from the inside out. Because of the weakness of your human nature, I am using the illustration of slavery to help you understand all this. Romans 6:19 Sin will also try to override our consciences. It will guilt us into doing what we know is wrong. Sin works to convince us that "I need to take care of me" no matter what it costs. Previously, you let yourselves be slaves to impurity and lawlessness, which led ever deeper into sin. Romans 6:19 The worst part about the bondage of sin is we can't free ourselves from it. So, we must give ourselves to a master who can free us. The third part of verse 19 addresses that. Now you must give yourselves to be slaves to righteous living so that you will become holy. Romans 6:19

A Life Free from Sin

So, how do we change masters? We have a free choice to choose between sin and righteousness. God gave us the ability to make the following choices with the help of the Holy Spirit. - Do not let sin control the way you live; do not give in to sinful desires. - Do not let any part of your body become an instrument of evil to serve sin. - Instead, give yourselves completely to God, for you were dead, but now you have new life. - So use your whole body as an instrument to do what is right for the glory of God. - Sin is no longer your master, for you no longer live under the requirements of the law. - Instead, you live under the freedom of God's grace. Romans 6:12-14 Take another look at our verse for today about how sin used to enslave us. It says, once you were slaves of sin, but now you wholeheartedly obey this teaching we have given you. What teaching? The Word of God! All the things Paul taught them became a part of the bigger picture, the Bible. Freedom from sin comes from obedience to God and His Word. Just like sin enslaves us from the inside, when obeying God, we begin to change first on the inside. We become less selfish and more righteous. We continually become free from sin. In fact, we become a slave to righteousness, which means we want to live a life pleasing to God. Being free from sin also changes our view on how we deal with the people in our lives. It's wanting to treat others with respect and dignity and with love and compassion. Look at what Jesus taught in Matthew 7, which we call the Golden Rule.

The Golden Rule

Do to others whatever you would like them to do to you. This is the essence of all that is taught in the law and the prophets. Matthew 7:12 So, let's say that you feel free from sin and living in righteousness. Plus, you treat everyone in your life the way you want them to treat you. And now you can just coast along. I don't think so! As humans, we will always serve as a slave in one way or another. If we don't consistently and consciously serve the Lord daily, our coasting will lead in the direction of sin. Now you are free from your slavery to sin, and you have become slaves to righteous living. Romans 6:18 Anyone who remains or reverts back to living as a slave of sin will forfeit the gift of God. Sin only produces wages, which results in a payday no one should desire. For the wages of sin is death, but the free gift of God is eternal life through Christ Jesus our Lord. Romans 6:23 Lord, because you have made a way for us, we can be free from our slavery to sin. It is only through your son Jesus we can become slaves to righteousness. Check out these related posts about freedom - God Helps the Helpless and Sets Us Free - How To Be Free In Life - Freedom From God For Everyone Read the full article

0 notes

Note

Why do you think Hamilton supported the Alien and Seduction acts as an immigrant himself?

This is a common discussion I see, and it becomes quite easy to understand when you take into account the current events, what prompted the Alien and Sedition Acts (which is what I will assume you meant instead of Seduction, since I think it would be pretty self explanatory why Hamilton would support Seduction acts), who John Adams was, and Hamilton's beliefs.

Firstly, the most prominent international event occurring at the time was the French Revolution. When the Revolutionary government replaced that of the Ancien Regime, it dissolved it's alliances with foreign nations, especially after they cut their king's head off. This resulted in a war and a dude you might have heard of named Napoleon, but we don't need to get into that to understand that Britain and France had major beef, even more so than before. As a result, a lot of the French people who did not approve of their government's actions, but still did not want to live under a monarchy, immigrated to the United States. Much like today's current debate over immigration, some people believed that the United States were not obligated to give refuge to these immigrants, that they would take American jobs, and posed a risk to American citizens. Hence, the Alien portion of the Alien and Sedition Acts.

As for the Sedition part, this was a personal gift from John Adams to himself. He was a very egotistical, sensitive man who could not take criticism of his policies from the newspapers. As stated by the National Archives, "The Sedition Act made it a crime for American citizens to "print, utter, or publish...any false, scandalous, and malicious writing" about the government."

John Adams, a Federalist, believed that in putting restrictions on citizenship and free speech, he was preventing American people from sympathizing with the French in the potential war that was brewing between America and France, since France was currently raging and ruining everything and making everything difficult for everyone.

Now, where does Hamilton come in? Hamilton was a Federalist, and while he didn't agree with Adams on almost anything, he was fiercely against any kind of violent rebellion. This is exhibited in the many times he attempted to stop a mob, the earliest one being at King's College, when he stood before a mob and lectured them, buying time for the president of the college to escape being tarred and feathered. This is repeated during the Cadaver Riots in 1788. This belief of his can be traced back to his childhood in the Caribbean, in which there was a constant fear that the overwhelming enslaved population (80% of the island's inhabitants were enslaved Africans) would revolt.

Hamilton was also a fan of Thomas Hobbes, who believed in a cynical idea of human nature, in which every individual is self-serving to their own wants and needs. Hobbes wrote in The Leviathan, "And from hence it comes to pass that, where an invader hath no more to fear than another man's single power, if one plant, sow, build, or possess, a convenient seat others may probably be expected to come prepared with forces united to dispossess and deprive him not only of the fruit of his labor but also of his life or liberty." The key differences between the philosophies of Thomas Hobbes and John Locke also resemble the distinction between Federalists and Democratic Republicans.

All this to say, Hamilton's beliefs were shared with Adams- the French immigrants were possibly dangerous, being a threat to the stable revolution that was surviving in America. Additionally, he followed the principles of Hobbes in his belief that the government was responsible for keeping the people in check, and preventing them from entering into their natural state, which made life "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short." The goal of the Alien and Sedition Acts was to prevent individuals aiming to bring a French-style rebellion to the United States, and to discourage similar sentiments from circulating in the press.

Clearly, this didn't work. The United States never went to war with France, this violation of the right to the press was not tolerated, Adams never served another term as president, and Hamilton never convinced a mob to disperse. The Alien and Sedition Acts weren't entirely anti-immigrant, as they were mainly targeted by the French, and if you're asking me personally, I believe Hamilton was able to disregard this as the law for citizenship (changing the residency requirements from 5 to 14 years) wouldn't apply to him anymore, and he could further hide the fact that he was an immigrant. He was ashamed of his origins, as the Caribbean was used at the time as, essentially, a large prison, and he didn't have the best reputation while he was there. I do think it is ironic that Adams was responsible for the Alien and Sedition Acts, and he was the one who tormented Hamilton for this birthplace. But, you know, I wasn't in that crazy ass redhead's mind.

I know this is long, but I've thought about this before, and I love getting into the reasoning behind Hamilton's politics. He was one of those cases where you can really see how his personal life influenced his political beliefs, and I think that's really interesting. Anyway, I hope this helps, and thank you for the ask <3

#alexander hamilton#amrev#amrev history#american history#john adams#alien and sedition acts#frev#french revoluton#napoleonic era#napoleon wars#history#also i didn't include a source for the hobbes quotes because i got them from my school papers lol#at the beginning of the year we did an assignment on locke vs hobbes and i was like 'oh man its the 1790s all over again'#fr tho i love that i got this ask#its been so long since ive talked/read about this era of hamilton's life so it was good to refresh my memory#and infodump about my bullshit as always#im still in 1778 in my reading of hamilton's papers so im moving at a snails pace in that area#and iiiii haven't read any chernow in like. a year#but i have been doing reading on the french revolution and man im really missing american history#its so much simpler im not going to lie#any country with a court is going to be way more complicated to learn about than a bunch of small democracies forming one big democracy#anyway im going to go work on fanfiction now bc ive done my duty to historical accuracy for the day ASLKFSKLJFJO#toodles

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Long post about whiteness

I’m seeing a lot of false-start questions based on a narrow understanding of whiteness. Whiteness (and recovery from whiteness) can be tricky to unpack because it has a lot of layers that have been added over the years. So you’ll run into a layer and may be tempted to stop there, but it goes deeper.

1) Racial identity was a vague belief before it was officially named, but it’s not as old as many think it is. Prior to European Expansionism, travelers and merchants and militaries alike have generally referred to people based on their place of origin or their language. The idea of vaguely lumping hundreds of ethnicities together based on a handful of physical attributes started to kick up when Portugal began capturing and enslaving huge numbers of sub-Saharan Africans in the mid-1400s. As slave traders and “explorers” brought shiploads of captured, multi-ethnic Africans to Portuguese auction blocks to be traded all over Europe, what set these enslaved people apart from anyone else there (including other enslaved people) was a) the fact that they were to some degree darker than the Portuguese despite displaying a wide range of skin tones, b) were from Africa at the time, and c) were enslaved. When Christian militant and royal biographer Gomes de Zurara was hired in 1453 to write about the life and “accomplishments” of Portugal’s most famous slave trader, Infante Henrique aka Prince Henry the Navigator, he officiated, in writing, the idea that all these newly enslaved people were their own class of people with no differentiation between them. Here, race is a burgeoning social narrative invented to praise European slave traders, and this racial concept is defined in relation to slavery, African origins, and skin tone. Racial concepts appeared in tandem with racist concepts, because races began to be envisioned in order to excuse the abuse of others. The ideas of whiteness and blackness were birthed simultaneously, specifically around slavery, and they became deeply entrenched beliefs before they were ever officially named.

2. “Negro” became the first major racial term before “white” was widely used, binding the development of racial concepts even more securely with the practice of European slavery. In fact, race and racism became encoded in colonial-American law in 1640, when African servant John Punch ran away from his European buyers along with two European servants. He was eventually recaptured, as were his Dutch and Scottish companions. However, the colonial judicial system sentenced Punch to a lifetime of slavery, while the two Europeans had an extra year added to their initial servitude. This marks the first record of a Euro/American legal precedence for lifetime sentencing of enslavement based openly on race. John Punch’s African lineage and the other servants’ European lineage were the differences between their sentencing. Here, European origin was what freed a person from being of the “negro race” and therefore severely reduced one’s likelihood to enslavement. It was also the requirement for incoming settlers who wanted to be able to buy land. Only white people were allowed to develop inter-generational wealth, at a time when this continent was being carved up by land speculators for massive profits.

3. The concept of whiteness was officially named by Carl Linnaeus in order to rank Europeans as superior among other conceptual categories of people. It involved grouping hundreds of ethnic groups together to form white, yellow, red, and black races in he text “System Naturale" (1735). While primarily an introduction to our current taxonomy system, it included these racial categories. It was highly regarded by Europeans eager to cast themselves as superior because it a) created a popular “scientific” framework for excusing the most obscene (and profitable) crimes against humanity, b) officially outlined/invented the white race and identified it with everything good and the black race as everything bad, and then c) clearly defined Europeans as the basis of whiteness, “Homo sapiens europaeus.” Here, whiteness is coined to describe European ancestry, particularly in relation to “grotesque” non-whites.

4. An individual’s personal ideas of whiteness fluctuates with time and circumstances. As governments, social institutions, literature, etc all work to redefine history and clean up their image, people have different/less information to work with, but the effects are the same. The popular spoken definition of whiteness is often simply a reference to a relatively pale skin tone caused by European ancestry. Obviously there are pale people in other places around the world who aren’t European and weren’t related to the slavery of European Expansionism, so pale skin isn’t enough. The relation to Europe’s capitalistic global expansion is key. But what about European countries who didn’t go expanding this way, or whose involvement is harder to pinpoint? After all, most of the trading of enslaved indigenous peoples from Africa and North & South America were carried out by the Portuguese, Genoese, Dutch, French, British, Spanish, and Americans. Well, the rapid enrichment and development of the rest of Europe for centuries to come was specifically made possible by all the labor, resources, and capital brought in by this period of the European slave trade. European ancestry links every white person to privileges and developments born on the backs of black and indigenous enslaved peoples. Furthermore, simply being white makes one safer from these kinds of exploits, and today it also makes one safer from the effects of generations of racial prejudices and resource extraction on the global scene. Which brings me to...

5. Whiteness tends to involve one’s relative freedom. Freedom of movement, both physical and social, without immediate threat of policing. Freedom to explore one’s ancestral history without being blocked by 500 years of forced removal, renaming, forced childbirth, etc. Freedom to exist without having to actually know or respond to one’s racial identity. This one’s really important. Whiteness involves not having to think about being white, usually in relation to living in a country/region whose laws and norms are defined and enforced almost exclusively by other white people. Since whiteness and blackness arose mutually around the European slave trade, blackness is inherently tied to a lack of rights/freedoms and whiteness is inherently tied to an abundance of them. That doesn’t mean that every white person experiences these equally, and there will always be exceptions to the rule. But the exceptions don’t make the rule, and after centuries of globalized white supremacy, whiteness has become a subconscious signifier of power for people all over the place.

The big take-away is this: whiteness is inherently toxic. There is nothing positive to defend in whiteness. It was born out of ugliness and it is ugly to its core. That’s why it feels so bad. It’s why “white pride” is always ugly. However, the solution is not to disconnect from our ancestry. All that does is leave us trapped here, in an ugly set of circumstances, with no concept of who we are except what we’re living in, now. The real work to be done is to connect with our ancestry before whiteness, with the ancestors who related to the land as a living entity, before the land was limited in social memory to a source of private capital, servitude, and empire-building. This land, this Earth, is the backdrop against which all our relativity is measured. From this place of relative security, understanding, and development of the spirit, we can withstand the reality of our more recent ancestors, and finally heal from the last 1000 to 2000 years of trauma.

I know I’ve said this before, but now that I have this huge post, I’ll repeat it: Dr. Daniel Foor’s Ancestral Medicine is a really helpful book and/or course for this whole process. It’s not the end-all be-all resource, but it’s a great start! I’m also always down to talk about this stuff. Hit me up. I need to be able to talk about it, too.

(I should add, while blackness was created by white people and therefore was born out of the racism of whiteness, blackness was forced on people, while whiteness was claimed by the takers. It’s no white person’s place to have an opinion about "black identity.” White people started race, so white people are responsible for deconstructing our own race--no one else’s. We cannot be “post-racial” while everyone else is still living the violent reality of racism.)

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, Captain America’s shield.

Here’s a symbol made of metal stolen from Wakanda and painted red white and blue for the purpose of mythologizing and defending ~America~. It gained its symbolic meaning through the blood, sweat, and tears of marginalized white Americans: disabled dirt-poor son of Irish immigrants Steve and implied-Jewish-in-Agent-Carter Howard. Is a Black man, descended from people who were stolen from Africa and forced to build the United States under horrific conditions, taking up this symbol only a “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house” situation, or is it worthwhile to manage the messy politics for the sake of the entire country celebrating Sam’s heroism as the obvious successor to Steve’s legacy?

I want Falcon and Winter Soldier to explore ALL the complex reasons Sam declined to take up the Cap mantle. Like the fear Sam has, and lots of other regular human people with high integrity and a strong moral code have, that the risk of making one mistake that hurts people makes him somehow unworthy (when this perspective is what makes Sam worthy, just like Steve “it’s not about me” Rogers before him). Like does he even want to bother representing a country that stole his ancestors and wants his labor and his aesthetics but not his perspective and will hate him even more for trying this. (Head writer Malcolm Spellman has told press that the majority-Black writers room is definitely planning on going here and I cannot wait to see more.) Like Sam got out for a good reason and once upon a time Captain America needed his help and that was a good as hell reason to get back in but is it still a good reason after all the fresh trauma he’s been through. Like his sister and nephews could use his help and maybe helping his family and hometown economically and psychologically recover from the blip is a better use of his energy and expertise than US imperialism or whatever the fuck SWORD is doing.

I want the show to explore why Sam gave the shield to the Smithsonian, specifically. Why this institution? It’s a unique part of the federal government that in some ways functions as an independent nonprofit educational institution and in some ways is a joint project of the 3 branches of the federal government (the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Vice President, and a few selected Senators and House members are always on its senior decision-making body). The Smithsonian is an obvious choice if Sam was deciding “which museum do I give the shield” — but was that the decision he was making? If Sam chose to give this historically meaningful but also still very powerful tool of war to the Smithsonian instead of the Department of Defense, that’s a very interesting character and plot choice and I want to see more about that. Especially given the Smithsonian seems to have immediately handed it over to the DOD without Sam’s input.

There’s a very obvious choice that I have zero faith Disney will explore but that would be infinitely more meaningful than Sam carrying the shield into battle, some right-wing jackass doing the same, or the shield sitting in an exhibit at the Smithsonian. Repatriate the shield to Wakanda. There’s no way in hell that pile of vibranium made its way to Howard Stark without colonialist theft involved. Sam could just give it back.

Imagine a museum exhibit in Birnin Zana that displays Captain America’s shield and shows the timeline from Wakanda protecting itself from European colonialism and its people from enslavement but some white people still managing to steal a little vibranium, to an American son of Jewish immigrants using some of that stolen vibranium to build a tool for an American supersoldier to use in fighting Nazis, to Steve Rogers using it first against and then alongside King T’Challa of blessed memory, the Black Panther who opened Wakanda to the world, and finally Sam Wilson, an African American who may or may not have Wakandan ancestry and may never know where on the continent his ancestors were stolen from, taking up Steve’s mantle and using that power to return this complicated piece of American symbolism to its ancestral home. Imagine African American kids seeing that exhibit on field trips to Wakanda.

Sam is going to pay a price no matter what he does with the shield, because that’s how antiblackness works. He’s paying a price right here on this hellsite because some fans can’t see past their Bucky obsession long enough to think about the white supremacist context of their shitposts. He would pay a hell of a price for going so far as to repatriate to Wakanda an object that many in-universe white Americans would no doubt see as a sacred object of ~their~ country. We saw at the end of this first episode the heartbreaking, insulting price Sam paid for giving the shield to the Smithsonian. Fuck how I wish there were an easier path for this character who is just so, so good and deserves a little goddamn peace already.

All that said, one thing I do have confidence Disney will give us is Sam punching that live-action Hydra Cap in the face on his way to taking back the shield. The politics of this show are messy as hell, but at very fucking least they can let Sam get in a really good punch.

#fatws#fatws spoilers#sam wilson#cap's shield#us imperialism#slavery cw#nazi cw#antiblackness#ffs america#marvel#mine#long post

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Afro-Futurist Future is a Harm-Reductionist Future

by Mallory Culbert

The end of the prison-industrial complex and the release of all prisoners are in humanity's best interest. Disabled people are more likely to be arrested & abused by authority figures/cops. Black people are arrested & jailed for drug-related charges at 2x the rate of whites, despite using drugs at the same rate. People who use drugs are punished for needing healthcare and/or minding our own damn business. We can do better.

The afro future cannot exist with harm reduction. We must address harm to the "afro" (Black) community in the form of reparations. For Black Americans reparations are due for slavery and for the racist drug war that incarcerates Black people disproportionately. After the civil war, 40 acres of land and a mule were promised to us. Without reparations, Black americans today have 1/10th of the wealth of white americans.

We are looking towards the future. We must be able to envision the future in order to build the future! In the Afrofuture, where we fully own our own bodies, drug use is a fact of life. Why? Because we can determine what best works for us!

We imagine an inclusive future that intentionally makes space for the perspectives & needs of historically excluded groups of people.

“The first Afrofuturists envisioned a society free from the bondages of oppression—both physical and social. Afrofuturism imagines a future [without] white supremacist thought and the structures that violently oppressed Black communities. Afrofuturism evaluates the past and future to create better conditions for the present generation of Black people through the use of technology, often presented through art, music, and literature” [1].

Afrofuturism is a direct contrast to Black Pessimism, a belief that considers Black people not as Humans, but as things to be watched and used by white and non-Black people. Black Pessimism examines the unique horrors of anti-Black violence, the endurance of anti-Blackness in the US after emancipation of enslaved folks and racial desegregation, and those aspects of Black suffering that cannot be fully explained by political economy or class conflict.

Black (capitalized, like every ethnic group) doesn't just include people descended from enslaved peoples in the americas, but is a term that describes the systematic devaluation of Black labor and bodies in a racial capitalist hierarchy. Whew, that was a mouthful!

This can look like Black laborers making a portion of what non-Black laborers make for the same work (devalued). It can look like Black neighborhoods being used as waste dumping sites by the local government (devalued bodies). It looks like racial segregation and whites moving away en mass to keep away from Black people. It is based in slavery with the idea that Black people are replaceable animals and not human. “Black” encompasses many culturally distinct groups of Indigenous peoples across the world, like the people of the Mer Islands of what is now called Australia or the Siddi people of Southeast Asia. Black folks span the spectrum and the globe; yet there is one universal experience between us--experiencing anti-Blackness, racial prejudice against Black people. This experience varies across cultures and depends on how race is socially understood and constructed in each one.

Afrofuturism escapes us to a different world, a world of our own creation. Black joy is not found in the absence of pain and suffering. It exists through it, even if injustice is inescapable. "So yes, I want the world to recognize our suffering. But I do not want pity from a single soul" [2].

Sources

Perry, Imani. “Racism is terrible. Blackness is not.” The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/06/racism-terrible-blackness-not/613039/

Capers, I. Bennett, Afrofuturism, Critical Race Theory, and Policing in the Year 2044 (February 8, 2019). New York University Law Review, Vol. 94, p. 101, 2019, Brooklyn Law School, Legal Studies Paper No. 586, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3331295

#afrofuturism#afrofuturistic#drugs#harm reduction#drug mention#Blackness#futurism#parentsnevertoldus#parentsnevertoldme#comprehensive sex education#afropunk

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

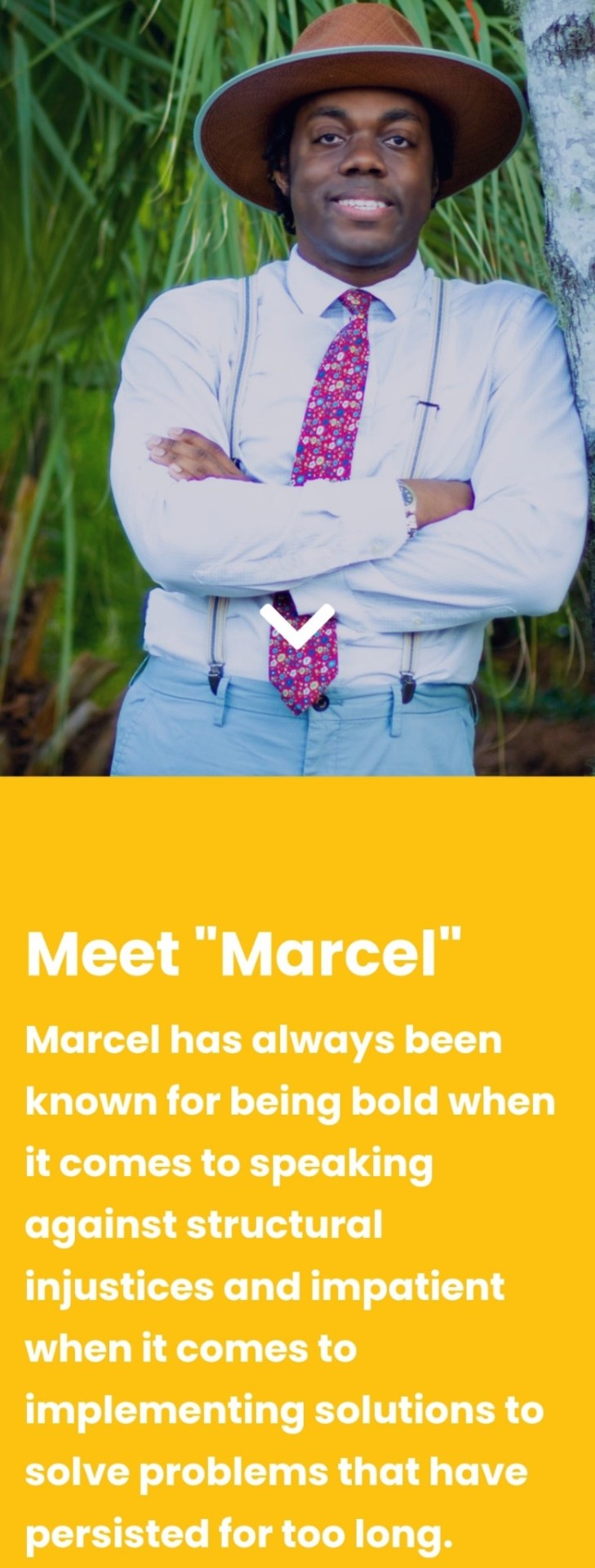

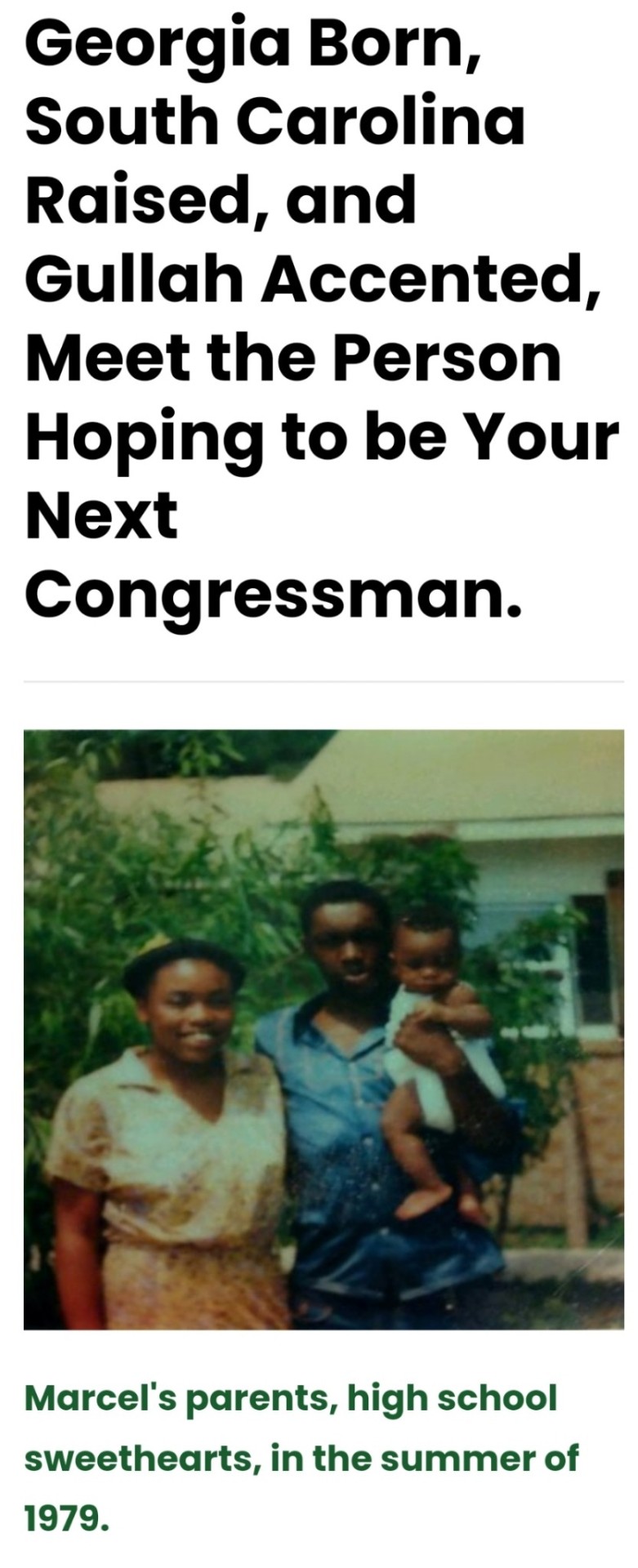

Gregg “Marcel” Dixon, the third of his parents, high school sweethearts, four children, is Georgia-born, the port city of Savannah, and South Carolina raised, just minutes away in the small, rural town of Ridgeland. Both areas are home to the Sea Island Creoles, or as they are better known, the Gullah-Geechee, a Black American ethnic group native to the sea islands, and the Lowcountry of the Gullah-Geechee Corridor where his family has resided since at least the mid-1700s. Even though he was a student of the Jasper County School District, South Carolina’s lowest performing district, a very troubled school system part of the state’s so-called “Corridor of Shame”, his childhood days, especially the earliest parts, were marked by love, happiness, and his rich, unique culture. He grew up with a large immediate and extended family that included his mother, his grandmother; his great grandmother; his grandfather, his two granduncles, his two uncles, his two aunts, his two cousins, and his three siblings. His great-grandaunts and cousins provided him and his siblings with a constant source of companionship, affection, camaraderie, and protection in their longtime community along a busy stretch of coastal highway that connected his town to the more popular Lowcountry destinations of Hilton Head Island, Beaufort, and Savannah. From all, he witnessed overwhelming compassion and empathy as they clothed, fed, protected, and housed many in need even though they were all people of modest means themselves. It was truly a wonderful time in his life.

At the end of slavery in 1865, Black Americans owned 0.5% of America’s wealth. Today, 165 years later, Black Americans at almost 15% of the population, fare little better owning just 3% of the nation’s wealth. The average wealth for a white American family is approaching $200,000.00 while the average wealth for a Black American family is almost 10 times less at $24,000.00. Twenty-five percent of black families have a net worth of either zero or negative and in just two decades, it will soon be zero for all Black Americans! This has NOTHING to do with the work ethic of Black Americans but has EVERYTHING to do with the systemic, government-sanctioned, violent enslavement, and the subsequent anti-black racial terror faced by Black Americans first centuries. This first manifested during chattel slavery, where they did not receive as much as a penny for their labor and then it continued through goverment sanctioned, violent discrimination and exclusion from government policies and initiatives that resulted in Black Americans being excluded from opportunities to build wealth, a number estimated to be high in the trillions. At the same time, they were simultaneously being forced into deep poverty, by means of redlining, Jim Crow, and land theft; extreme violence by means of lynch mobs, police brutality, terrorism from the FBI, and race riots; robbed denied equal access to an education by means of underfunded schools and educational discrimination, and more. This has not just hurt Black Americans, but all Americans.

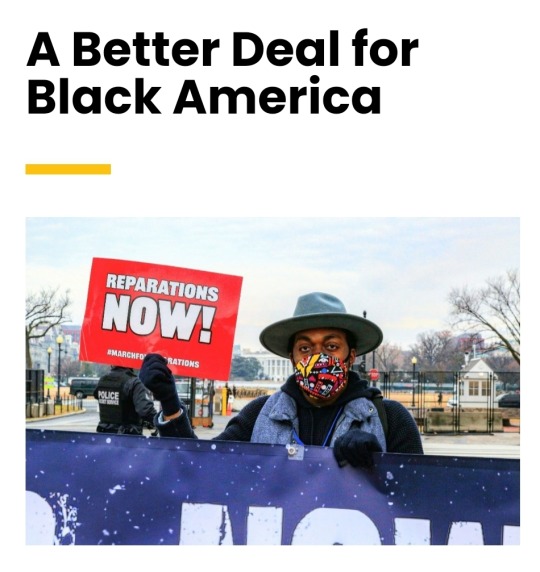

According to one study, anti-black racism has caused the United States SIXTEEN TRILLION DOLLARS! It goes without saying then, a thriving Black America is a thriving America, hence, the motto of my campaign, “Repair Black America To Fix America”. The word “reparation” means “the act of repairing and keeping in repair.” To solve these issues, the American government has a responsibility to repair the damage it has caused, and that is why I will do all within my human power to bring a multifaceted reparations package for Black Americans That Are Descendants of Those Who Were Enslaved By The American Government aka Freedmen to fruition that will be funded by government spending, as have past initiatives.

This package will include:

The closure of the racial wealth gap that will include measures such as direct monetary payments, tax exemption status, debt cancelation, land grants, business grants, and more;

Class protection status for those descending from those who were enslaved by the American government;

Allotments of federally granted and protected land in all 50 states where only Freedmen can settle and receive services from the institutions located on these aforementioned lands;

Provisions of federally subsidized housing and business grants;

The investigation of cold cases of anti-black racial terrorism to bring all living criminals to justice;

The reform of heirs property to provide full equity and ownership to all heirs and compensation for any property that may have been lost or stolen through unethical avenues such as “partition sales”;

The reestablishment of the Freedmen Bureaus to close all disparities between Freedmen and White Americans such as the high mortality rate for black women during childbirth versus what it is for white women, job discrimination, heirs property, etc.

Establish a commission to specifically review and immediately address the unique challenges facing black men and boys.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

curious as to your take on the current debate going on in hamiltonia re: hamilton a slaver vs hamilton not a slaver?

Whew, this is going to be a long answer. Since Jessie Serfilippi’s “As Odious and Immoral A Thing” was first published (I posted a few brief quotes here), likely as part of an ongoing interest in the Schuyler Mansion State Historic Site with the subject of the Schuyler and Hamilton families and slavery (see here for blogposts labeled ‘slavery’ including a couple about AH specifically), there have been three versions of a rebuttal by Michael E. Newton and some people calling themselves Philo (”Love”) Hamilton, one of whom is Doug Hamilton*. The ongoing engagement on this topic also brings up issues of historiography and hagiography.

In this whole discussion there is only one new piece of evidence that Serfilippi has referenced on Twitter but is not part of her article - I’ll get into that below. Everything else is a re-analysis of known and fairly popular sources, so I don’t think going through it point by point would be helpful.

But let’s be clear about something. This discussion around AH is in large part because of this Chernow falsehood: “[f]ew, if any, other founding fathers opposed slavery more consistently or toiled harder to eradicate it than Hamilton.” Chernow also calls AH a “fierce abolitionist” and a “staunch abolitionist” because Chernow doesn’t know what abolitionism is. This lie got tons of mileage with Lin-Manuel Miranda, whose musical character AH may have personal moral defects, but not blind spots as huge and disastrous to a modern audience as a lackadaisical approach to the owning of other human beings. (That Miranda’s approach totally riled some Black artists and scholars is well-known, and I wrote briefly about it here.) Serfilippi’s article doesn’t get the media play it does without the popularity of the abolitionist Founding Father myth that Miranda put on stage. So this conflict and news-cycle interest arose from Chernow’s need to give AH the moral high ground by claiming that he was the best best best abolitionist because Chernow is interested in hagiography, not biography. Unfortunately, Newton-Hamilton seem interested in the same thing.

A brief note on word usage: an enslaver, in most current usage, is defined as someone who participated in any aspect of the slavery enterprise. Considering AH’s undisputed role as money-handler (or the more laughable ‘he was a banker’ assertion in the Newton-Hamilton essay) for members of the Schuyler family acquiring enslaved persons, AH was an enslaver.

In my opinion, on the issue of slavery, AH is damned by his extensive ties from 1780 onwards to the Schuyler family. There’s nothing that can explain away the fact that AH at times lived with, visited, and sent his wife and children for extended stays and to be educated by his slave-owning in-laws. AH did not somehow become innocently involved in slave trading and ownership. Rather, he knew what he was doing when he married into the heavy slave-trading and owning Schuyler family and when he engaged in business acts for that family, including helping them to acquire/sell enslaved persons. These were morally weighty - and abominable acts, argued even in his day - and he did them anyway. There is not any record that remains that he had a problem having his children reared within an abhorrent system/household where people were enslaved and served them; in fact, given the number of times he sent his children to his father- and mother-in-law’s home for extended periods, it could be suggested he found nothing morally objectionable going on there. Philip Hamilton even thanked his enslaver grandfather for his advice on how to “be a good man.” P. Schuyler’s wealth and trading was through the slavery economy. Moreover, AH’s economic concerns were also inextricably tied to slavery - keep in mind that every mention of tariffs on sugar is connected to the slave trade. Almost everything led back to that evil institution.

During AH’s lifetime, a number of white AND Black persons articulated that all enslaved Black and Indigenous persons should be freed, that the practice of enslavement was a grave moral failing. AH was well-informed enough to know that Black Americans were articulating how freedom should be applied to them - indeed, many of the manumission policies of the original states arose from these efforts. So AH was fully aware of the arguments. (His son was involved!) Maybe this helped inspire him and his slave-owning friends and political colleagues to form the NY Society for Promoting the Manumission of Slaves, although none of this group agreed to give up their own enslaved persons as part of the organization of this group.

Or, as Newton-Hamilton audaciously state, “[AH] was more involved in building a nation” sotto voce based on enslavement and racial distinction than he could be bothered to care about the lives of enslaved people. This shouldn’t be a surprise when it comes to AH’s major moral failings/blind spots - he didn’t care about the lives of the people affected by his whiskey tax either. If one wants to nevertheless call this a “good man,” we’re probably looking at each other from across a void.

But this is well-trod territory. Several articles post-Chernow have evaluated and summarized positions on AH and slavery that I share:

“Hamilton's position on slavery is more complex than his biographers' suggest. Hamilton was not an advocate of slavery, but when the issue of slavery came into conflict with his personal ambitions, his belief in property rights, or his belief of what would promote America's interests, Hamilton chose those goals over opposing slavery. In the instances where Hamilton supported granting freedom to blacks, his primary motive was based more on practical concerns rather than an ideological view of slavery as immoral. Hamilton's decisions show that his desire for the abolition of slavery was not his priority.” Michelle DuRoss, “Somewhere in Between: Alexander Hamilton and Slavery,” Early American Review, 2011 [part 1, part 2]

“But it does illustrate something that his primary modern biographers have been reluctant to concede: Hamilton routinely subordinated his antislavery inclinations to other family and political concerns, and he did not ever approach even a modest level of engagement on the issue in his otherwise voluminous published works.” Phil Magness, “Alexander Hamilton’s Exaggerated Abolitionism,” 2015

“He was not an abolitionist...[h]e bought and sold slaves for his in-laws, and opposing slavery was never at the forefront of his agenda.” Annette Gordon-Reed, “Correcting ‘Hamilton’,” Harvard Gazette, 2016.

Serfilippi extends this:

When those sources are fully considered, a rarely acknowledged truth becomes inescapably apparent: not only did Alexander Hamilton enslave people, but his involvement in the institution of slavery was essential to his identity, both personally and professionally.

I have no objection to her statement. We simply have no record of AH strongly challenging the institution of slavery, while several of his colleagues and friends most certainly did. Instead, we have the financial transactions, the possible use of enslaved labor, and the possible ownership of enslaved persons, alongside his strong personal, professional, and political ties to owners of enslaved persons. And the new evidence: the inclusion of the following in a list of persons dead of Yellow Fever in NYC 1798, “Hamilton Alexander, major-general, the black man of, 26 Broadway” An Account of the Malignant Fever, Lately Prevalent in the City of New-York, 1799. We cannot know if this was an enslaved man or a free Black man who lived and labored for the Hamiltons, but it should eliminate anyone confidently stating that the Hamiltons did not own enslaved persons.

Thus, Serfilippi has successfully accomplished at least one important goal: bringing to the forefront the names (as we have them) of persons, servant or enslaved, connected to the Hamiltons.

I wrote above that part of the problem here is hagiography. If his concern is with the truth, I certainly look forward to Newton’s chapter-by-chapter repudiations of books written by Chernow, Brookhiser, and Knott on AH and the AH/GW relationship.This leads to the second issue that has arisen: the unprofessional, and frankly gross, glee in trying to punch down on a young female scholar. In my own field (an ex-partner is a military historian so I’ll speak for their field too), the approach when one believes a colleague is publishing in error and one has additional information that could illuminate the issues is to contact them and seek to work together to analyze and draw conclusions. Newton and the anonymous Love Hamilton clan didn’t treat Serfilippi as if she were deserving of this respect. Moreover, Newton has never, to my knowledge - and I purchased his books! - gone this hard after Chernow, who certainly deserves it even more.

But Newton-Hamilton betray their own concerns here: “Considering the era in which Hamilton lived, the challenges he faced, and his accomplishments, it is not difficult to understand why Hamilton did not make opposition to slavery his primary focus. His attention was on building a nation.” And what kind of nation was that? At the Constitutional Convention, AH’s lengthy speeches on the formation of the government have been recorded. There is no record of him offering any statements about the slavery issue, unlike his friend Gouverneur Morris.

Newton-Hamilton continue: “Unfortunately, that meant neglecting other important matters, not just slavery but also his own financial well-being.” Wow, a comparison is made between AH’s personal finances and the ownership of human beings. Could these authors be any clearer that the slavery issue is an inconvenience that they are ultimately unconcerned about? I’m unsure if Newton-Hamilton realize just how gross their attempt at addressing this issue has been, and that it’s hard to take their interpretation and analysis of the evidence seriously when these are the kinds of statements making their way into the rebuttal essays.

Now there is an interesting discussion about how even later abolitionists did not see a conflict in the employment of enslaved labor, but that too isn’t something that Newton-Hamilton show interest in. Instead, their approach seems to be that AH needs to be celebrated at all costs, and thankfully, those days are passing into history.

*It’s ridiculous that a group of people have given themselves a stupid pseudonym to avoid attaching their actual names to a so-called scholarly article. And I’m aware that I’m writing this anonymously, but on tumblr where maybe 5 people have made it to the end of this (I’m not publishing it on my real blog).

**I will not link it, but it can be found on Newton’s blog discoveringhamilton.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

As early as 1700, Samuel Sewall, the renowned Boston judge and diarist, connected “the two most dominant moral questions of that moment: the rapid rise of the slave trade and the support of global piracy” in many American colonies [...]. In the course of the eighteenth century, three textual moments prepared the grounds for a major semantic shift in the trope of piracy in the Atlantic context, turning its primary connotations from exploration and adventure to slavery and exploitation. [...]

[A] large share of Atlantic seafaring took place in the service of the circum-Atlantic slave trade, serving European empire-building in the Americas.[...] [S]hips also became a popular literary topos for writers critiquing slavery. Ships have been cast as important sites of struggle and as symbols of escape in the context of a fledgling Black Atlantic consciousness, from Olaudah Equiano’s Interesting Narrative (1789) and Richard Hildreth’s The Slave: or Memoir of Archy Moore (1836 [...]) to nineteenth century Atlantic abolitionist literature such as Frederick Douglass’s My Bondage and My Freedom (1855) or Martin Delany’s Blake (1859-1862). [...] Black and white abolitionists across the Atlantic world were imagining a different social order revolving around issues of resistance, liberty, (human) property, and (il)legality [...]. In the Black Atlantic context, the ocean, like the ship, similarly functions as an ambivalent, heterotopic site, “a trope marking the unruly space between the past memory [...] and the present reality of slavery in terms of active resistance” [...]. Furthermore, the moving ship, as a symbol, represents “the moving to and fro between nations, crossing borders” [...].

---

During the slavery crisis of the mid-nineteenth century, piracy signified the criticality of legitimacy in the context of Black Atlantic literature.

Black Atlantic narratives responded to the crisis and voiced a critique of the triangular trade by turning the trope of the pirate as a figure of excessive consumption on its head. Using black pirates as figures of resistance to an exploitative system of enslavement and to the spectacle of colonial commodities, Maxwell Philip’s novel Emmanuel Appadocca (1854) emphasizes the nexus of insatiable material desire and its conditions of production: slavery. In addition, Black Atlantic narratives of piracy also turn upside down the traditional definition of the pirate as renouncing all ties and laws of nature [...]. [B]y appropriating claims to natural law as incompatible with a slave-based system, the pirate, paradoxically, becomes the outlaw defendant of laws of nature as opposed to legal law. [...] [T]he consumption of commodities produced by slave labor itself was delegitimized [...],.

In Emmanuel Appadocca, piracy is presented as a result of disenfranchisement on the one hand and as a source of empowerment and strength in the struggle against inequality and injustice - particularly against slavery and its consequences - on the other. In the novel, the pirate ship enacts a different sort of “imagined community” (Anderson {1983] 2006) than that of the nation-state, which excluded various groups of people due to its racist and classist colonial structures. [...]

One of the central discourses in Emmanuel Appadocca is that of legitimacy, of rights and lawfulness, of both slavery and piracy, focusing on the natural right to resistance [...]. About midway into the book, Appadocca gives a powerful speech in which he argues that colonialism itself is a piratical system:

If I am guilty of piracy, you, too [...]. [T]he whole of the civilized world turns, exists, and grows enormous on the licensed system of robbing and thieving [...]. The people which a convenient position ... first consolidated, developed, and enriched, ... sends forth its numerous and powerful ships to scour the seas, the penetrate into unknown regions, where discovering new and rich countries, they, in the name of civilization, first open an intercourse with the peaceful and contented inhabitants, next contrive to provoke a quarrel, which always terminates in a war that leaves them the conquerors and possessors of the land. ... [T]he straggling [...] portions of a certain race [...] are chosen. The coasts of the country on which nature has placed them, are immediately lined with ships of acquisitive voyagers, who kidnap and tear them away [...].

In this [...] analysis, slavery appears as a direct consequence of the colonial venture encompassing the entire “civilized world,” and “powerful ships” - the narrator refers to the slavers here - are this world’s empire builders. [...]

---

The alleged violence of the Caribbean pirates [...] is of special significance in the context of the text’s discursive appropriation of piracy as a means of heterotopic resistance. [...] Moving from the Caribbean background toward the ocean in its setting, Philip’s novel inverts the significance of this Atlantic motif through the association of piracy with a rough [...] Robin Hood principle [...] by redistributing the wealth of the colonies. Piracy, for Philip, signifies a just rebellion, a private, legitimate war against colonial exploiters and economic inequality - he repeatedly invokes their solidarity as misfortunate outcasts [...]. That the pirate’s mobile, temporary home has to remain beyond the Caribbean shores is both evidence of an emergent counter-modernity informed by the Black Atlantic and the tragedy of Philip’s text. In the nineteenth century, the heterotope of the pirate ship thus helped Black Atlantic literature like Philip’s to give voice to subaltern subject positions and allowed for a discursive questioning of the dominant order, even though the design of a ‘more perfect’ place from the perspective of the oppressed remains unstable.

---

All text above by: Alexandra Ganser. “Cultural Constructions of Piracy During the Crisis Over Slavery.” A chapter from Crisis and Legitimacy in the Atlantic American Narratives of Piracy: 1678-1865. Published 2020. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me.]

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

Black Lives Matter: Race and Racism Across Time in the U.S.

by Amir Agurs

“The construct of race has always been used to gain and keep power, to create dynamics that separate and silence. Racist ideas have been woven into the fabric of this country, and the first step to building an anti-racist America is acknowledging America’s racist past and present”. - Ibram X. Kendi

Racism is the cancer of America. It is pervasive and has influenced and infiltrated every system of this country. America was not founded from a human rights standpoint and the constitution extended the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness primarily to white men. This final presentation will focus on the theme of race and racism across three key time periods 1) the onset of slavery and the science of race, 2) Jim Crow to Black power and 3) the age of social media to racial reckoning.

RACE + OWNERSHIP = RACISM

In 1619 the first Africans arrived at the shores of Jamestown. They did not come by choice, but through brute force; captured from their homeland, transported across the Atlantic, to exist in a permanent state of chattel enslavement in a foreign land. Forced labor and indentured servitude were not uncommon practices throughout history. According to Elliot and Hughes (2019), “Africans and Europeans had been trading goods and people across the Mediterranean for centuries ---but enslavement had not been based on race” (Elliott et al.). The trans-Atlantic slave trade sparked a 244-year reign of terror and suffering on Black people supported by science and law. Despite this reality, Black people resisted, survived, and begin to create a new cultural identity in America.

Racism as defined by sociologist Neely Fuller, is system of thought, speech, and action, operated by people who classify themselves as white, and who use deceit, violence, or the threat of violence to subjugate and abuse people classified as non-white, under conditions that promote the practice of falsehood, injustice, incorrectness, in one or more areas of activity, for the ultimate purpose of maintaining, expanding, and refining the practice of white supremacy” (Fuller 36).

Race became what Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie refers to as a single story. The single-story, she says, “creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but they are incomplete---making one story become the only story (Adichie 03:15–05:21). Race, as a US social construction and human invention, was developed to justify the enslavement of Black people and grant or deny benefits and privileges based on a hierarchy of racial superiority (National Museum of African American History and Culture).

youtube

In Early American history, Racial stereotypes played an essential role in shaping the attitudes towards Black people (Green). During the mid-1800′s the scientific community tried to legitimize their racist ideas that Black people were inferior and only suitable for service (National Museum of African American History), lacked the intelligence to learn because they had smaller skulls, the initiative to work and the qualities for morality and domesticity to live in a society (“Racial Stereotypes of the Civil War Era”). The work of early European scholars helped to fuel anti-blackness that the Civil War and Emancipation did not undo.

RACISM + JIM CROW = 100 YEARS OF TERROR

The Emancipation Proclamation of 1865, abolished chattel slavery, was signed into law by President Lincoln. Even though Black people were technically free, it was not until the ratification of the 13th-15th amendments adopted between 1865-1870, five years following the Civil War that slavery full ended (Reynolds and Kendi). These laws restructured the US from a country that was “half slave and half free” to a nation where freedom existed for all people, not just those that were white.

Reconstruction provided hope to Black people, allowing them to obtain the privileges and rights of being an American. For the first time in 200 years, Black people were able to function and be recognized in society as fully human. Black people were able to run for political office, own land, serve on juries, vote, and marry. By the end of reconstruction in 1877, over 2000 Black men had served in offices from senators to ambassadors (Locke and Wright). The promise of Reconstruction was short-lived because primarily southern white Americans became increasingly opposed to the idea of Black social and political power (Reynolds and Kendi). The response from white people was to use law and state constitutional provision to empower the south and kick off a 100-year reign of terror on Black people.

The Jim Crow era (1876-1965) disenfranchised Black people through a set of laws referred to as the Black Codes and returned Black people to a subordinate position in society in order to maintained white supremacy and control over Black people lives (Reynolds and Kendi). Black people did could not serve on juries, run for political office, own firearms, had no voting rights or civil rights. Many of the Jim Crow laws were focused on creating segregation and keeping Black Americans from white schools, public transportation, entertainment, parks, restaurants, bathrooms, and even water fountains (Reynolds and Kendi 54). It would be almost 100 years before Black Americans would not enter the political field again and reclaim their human rights (Stefoff and Takaki 58-59).

youtube