#also this whole project is so low stakes... like it's literally for an event where nobody is gonna care how it turns out except me lol

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Snoopy #51

21/11/2024

#peanuts#snoopy#art#51#a lil snoopy doodle from my journal!#been a bit too busy today to break out the drawing tablet and the laptop hahaha#for avid readers of my tags (all zero of you :P) i managed to finish the art project i've been doing this week jusssttt on time!#idk i still have a little bit more time to work on it so i'll put in some finishing touches later but it's like doneeeee#also this whole project is so low stakes... like it's literally for an event where nobody is gonna care how it turns out except me lol

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Out of all of the show runners/creators to get their shows taken away from them or pushed out/quit, why couldn’t it had been Chris? 🥺

Chris did have some truly brilliant moments, but S8-9, IWTB, and S10-11. Although all of them had episodes I liked (and moments for the movie), Chris was disconnected from his audience and no longer understood what made the series work.

Although I can live without the conspiracy post S5, it does have its importance. I see the appeal of it from a show running and fan perspective.

The problem is: either Chris didn’t have a series bible or ignored it (I believe I heard he didn’t have one). So, when you don’t pay the conspiracy too close attention, it’s compelling and thrilling.

But, post S5, it feels like an afterthought that believes it’s much more important than it really is. The stakes don’t feel (as) high. I don’t think the location change would’ve hurt all that much if they don’t lose the writers as well. They also figured out better lighting later on to give it that same mysterious vibe (But, I enjoy S6-7 regardless).

But, when the S8 conspiracy unfolds to us, we get Chris at his absolute worse, which he doubled down on every time a new project for the series was greenlit.

I’ve always been of the mind that Skinner should’ve had a bigger role in S8-9. Another fan said it quite succinctly, “Fans invested in the ‘Mulder and Scully v world’ dynamic and now you’re trying to include other people.”

We went on this long journey with Mulder and Scully. We saw how their relationship began, watched it developed, and saw all of the ups and downs. We know why they only trust each other.

The show asked us to invest in the intimacy of these two people. And I don’t mean that in a sexual way. But, working so closely with someone for literal years and they are literally the only person you trust. Putting their lives in danger and risking everything for each other and the greater good. The only acceptable person to “replace” Mulder would’ve been Skinner.

How that would’ve happened, I’m not sure.

But, Doggett was never going to work this late in the series, esp replacing a well loved character who is the driving force of the premise.

Fans would’ve had an easier time accepted Mitch in a promoted role and having Skinner and Scully work to find Mulder. As they investigate in their off time, that’s when they uncover the new conspiracy...or maybe Mulder floated it and Scully finds proof of it.

After taking some time off from the FBI due to Mulder’s disappearance, she comes back. Chris could’ve did like a three part episode (lol) of Scully being in Seattle and the desert. Following up, gathering evidence, and maybe even exploring her emotional reaction to this traumatizing event and spending time with her family.

Maybe we could’ve met Charlie! But, I think we could’ve gotten an episode from their perspective or something. How much Dana has changed, her peculiar behavior, and their protests about her going back to work.

Scully initially wants to trying investigating the x files alone, but realizes she can’t because 1. She isn’t Mulder 2. You need at least two people for the x files to work 3. Her pregnancy.

This is then when she gets a partner. Skinner wanted to vouch for them, but the decision was above them and he can’t be sure where their loyalty lies.

The series doesn’t do any of that “Mulder secretly had cancer and didn’t tell Scully”, esp because Scully was allegedly his physician and, you know, that’s just something he wouldn’t do.

Like, what the fuck?!?! Mulder was secretly dying of cancer for a year or two and we never see signs of it? We don’t see a change in Mulder or a somber air about him. We don’t see Scully reacting to this??? And it’s even more of a slap in the face because Scully dealt with cancer and she could’ve been there for him. And Mulder would’ve never wanted to leave Scully out of the loop like that!

There’s no way!

No way at all.

For a season or two, Scully, Skinner, and the fans are unsure as to where the new agent loyalties lie.

We could do DeadAlive, it we’d need to spend some time with Scully and the aftermath. Skinner gets to choose the new (temp) partner. Vouches for them.

Mulder comes back and he’s paranoid about the new agents. Scully explains that there isn’t anything they can do, she doesn’t trust one of them either, but she trusts skinner (finally, and it was after Mulder was abducted), so she tells him not to worry about the second agent.

I think the series may have to lean on Mitch even more in season 9. My problem with Doggett was his overt hostility about paranoid shit. Scullys whole thing was that she was a skeptic, BUT she was respectful and kind even when she thought the theories were out there. Doggett is an ass about it. We’ve followed the series for 7-8 seasons at this point and we bought into th premise, Doggetts behavior doesn’t work due to 1. Most of us love Mulder 2. We love how Scully treats Mulder’s theories 3. We are willing to suspend our beliefs for the improbable.

Doggett beliefs are like Tom Colton and we didn’t like him (it’s mocking). I mean, I don’t hate the guy, but it’s clear he’s frame as a secondary antagonist to Mulder during the ep.

So, the person who plays off of the plant/maybe plant is respected, but nothing eye roll worthy. They have a healthy amount of skepticism, but we see that they’re struggling with the things they’re encountering. They don’t know what to make of the x files, but what they knew or thought they knew was all wrong or not exactly write.

We see them reading casefiles. Asking Scully about when she first started there herself. They’re trying to wrap their mind around the existence of the paranormal.

They ask Skinner why they were assigned to the x files, maybe we see a flashback. And skinner says that they needed something to believe in. Perhaps this new agent comes from BSU or an intense unit and is burned out. But, also, it only are the damned food at their job, they have integrity. The x files will challenge you, but it will give you something to fight and believe in.

When Scully comes back from maternity leave, the second agent returns to their previous position, which was a unit they transferred to after BSU. After a few cases, Scully can’t stand to be away from William and decides to work in office (teaching). The second agent gets permanently reasssigned to the x files.

Mulder is constantly traveling to unravel this second conspiracy. But, he and Scully are always in contact. We hear about it more so than see it. Scully (Mulder)/Skinner chooses the cases.

Scully doesn’t give up their son.

Maybe they still run away together.

(A shot of William in the hotel room with them. 🥺)

I low key want to write this. Lol.

I’ll speculate more in how I can rework IWTB and S10-11.

Thoughts?

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nuno Brandão Costa - Factory extension, Paredes 2015. Via archdaily, photos (C) André Cepeda.

“Correcting the box” Kersten Geers

What is the form of a box? Boxes and their potential architecture are both fascinating and utterly problematic. Forty-five years since Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi made us learn to love the box, this most common of utilitarian structures has been the subject of preposterous and mostly failed attempts to turn it into Architecture. Many of these attempts were ambitious but seldom successful; most of them were too keen to inscribe the buildings with what we commonly accept as architecture, with its intricacies and mannerisms, and as a result, they ignored the very DNA of these buildings. When making architecture forces us to hide its generic character, it is an awkward mistake: a box is a box after all. The fact that boxes are ubiquitous today doesn’t make it any easier to design them. Mid-sized boxes are everywhere. They are an important constituent in an evenly covered field. If Big Boxes are a somewhat more gratifying design problem, simply because of their sheer size – it often is the only real quality these buildings seem to possess – scale also remains a key factor in the design of these mid-sized industrial buildings that seem to make up half of our present-day urbanised universe. In the slipstream of the ‘Decorated Shed’, any ambitious entrepreneur will have engaged himself over the last decades in beautifying his or her industrial container. Thus fitting both the desire to be seen, and seemingly fulfilling the cry for architecture in a place of perpetual sameness. But is that really what we should be after? Is it really what is at stake? These endless variants of company buildings, shoeboxes with add-ons: strange fronts, fancy signs, elegant entrances ‘du moment’, they all might make for a proud CEO, but they do not add up in this endless sea of small special features of self-indulgence. Like spoilers and stripes on a fancy car, they are merely a private affair; totems of personal taste and machismo – features the landscape simply endures.

How can a box transcend this pool of self-indulgent indifference? What is it that makes a box engaging, a space defining or simply powerful enough to transcend the private project?

To be any of this (and preferably all at once), a box needs to have territorial intentions. It needs to engage with the landscape it inhabits and find a proper scale to deal with it. In the meantime, it should give up its obsession with small intricate details: spoilers are not allowed.

A box that engages with its territory can be many things: it can be both simple and complex, long or short, high or low, but most important: it has to have the guts to choose what it is about and how it delivers; a good box acts without mercy with an intelligent version of an economy of means.

The building designed by Nuno Brandão Costa for Viriato is such a building. Perhaps the new building was fortunate to already find itself in a complex situation, a place that asked for clear decisions. Many things that were already there were perfect examples of mild self-indulgence. The site already had a workshop and a tasteful front. The fancy face was there, so the new building could find its challenge somewhere else. The Viriato box of Brandão Costa is an addition to the existing complex and seeks that opportunity as a possibility to give the whole complex territorial significance. Its negotiation with the landscape can be understood rather literally: the building is long and wide enough to make the complex exist. It is simple enough to make it understood. It is blunt enough to make the rest of the buildings – the existing ones – disappear.

The new building is stretched to its maximum dimensions and defines a clear datum. The landscape it inhabits is not flat, but in a rather uncompromising way, the new building seems to ignore that fact. The building is pure plinth and corniche – if the landscape goes down, that is considered a pragmatic opportunity but not a fundamental architectural theme. The theme defines the building and its appearance; the territorial opportunities make the building work. The plinth and corniche define the datum of the building and somehow narrate what the building would like to be. They show from up close where it reluctantly gives in, as if it is a carefully measured compromise. Although the building itself is very boxy and in fact quite clever in its sophistication for a box, it finds its final shape in the negotiation of what is there. Each of these negotiations makes for small corrections without ever losing the overall shape of the box itself.

The high voltage post on site provokes a complex formal decision, a bump in the platonic geometry. But it is so simple and effective in how it curiously reveals the fiction of the single-storied building, momentarily, that the moment you see it, you seem more convinced of the overall geometry. The explicit architecture of the box turns this major event into a footnote. The entrance to the showroom has an even smaller effect. It is a simple ramp that by its existence only emphasises the plinth, and again confirms the basic geometry. The angle of the adjacent street slightly tweaks the geometry of the box itself, but that also happens almost invisibly. Time and again, the box seems strong enough to take any blow of function and context without losing its steadfast character. Perhaps, most interesting in these series of small corrections of the flat and elegant volume is the positioning of the small stairway on its longest façade. By placing it at the plinth there just before the terrain steps down, it grabs all our attention, and the drop in the terrain becomes almost invisible. One keeps looking at the stairway and the pedestal. The simple building is of course in the end a complex tour de force. What seems like a pedestal along most of the façade, and before the previously mentioned stairway, turns into a beam, and carries the cantilever of the building above the loading dock. So, in a way, it loses its major feature (as a base) and it becomes ‘technical’. It is at this moment that one can see the extreme refinement, and perhaps manipulation of Nuno Brandão Costa’s architecture. By (over) designing a set of defining elements of his building, he somehow frees these elements, so they can do what they want. If the pedestal wants to be a cantilever, fine! It will forever remain a pedestal, no matter how it behaves. Does the plan need a bump? OK! It will forever be read as a box. Thus, Nuno’s corrections show at the same time the intricacies of great architecture, and the monumental features of a great building – a landscape defining box. Nuno Brandão Costa’s box is for that reason the many things he allows the building to be, but most importantly a few things he wants his building to be.

It is in what he wants, that one finds the essence of his architecture: a plinth and a corniche – ground and roof: the two horizontal lines of reference; the rest is secondary. This is no accident. If the plinth’s role is blatant and indisputable, it is in the treatment of the roof that the building finds its sophistication. On the shorter sides of the new building, the mirror glass cladding abruptly stops to reveal the beams of the roof structure: a Spartan skeleton, a naked structure. In all its binary logic, the plinth remains an architectonic intervention, ready to show the skills of the sophisticated designer. The roof, however, is shown as what it is, as the ultimate counterpart of territorial design: technical containment. Is this the ultimate design task of the architect in a sea of indifference? To have the guts to show all that we have left. And to put that on a pedestal. Anything more seems frivolous.

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

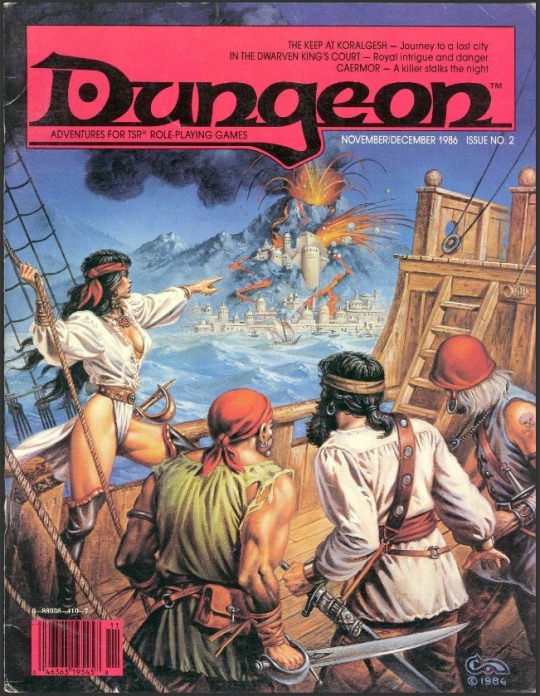

Patch Has Issues: Dungeon #2

Issue: Dungeon #2

Date: November/December 1986 (Pretty sure my Christmas haul that year was full of dope toys from The Transformers movie/show.)

The Cover:

(Use of cover for review purposes only and should not be taken as a challenge to status. Credit and copyright remain with their respective holders.)

Ah, Clyde Caldwell. He, Larry Elmore, Jeff Easley, and last issue’s Keith Parkinson were the mainstays of TSR’s amazing stable of artists. I have a soft spot for Caldwell. He did the covers for the D&D Gazetteer series, which means his work emblazoned some of my absolute favorite books from my middle school years. (At the time I had the whole series except the two island books, GAZ 4 & GAZ 9 (which I’ve since collected), plus the Dawn of the Emperors box set. My favorites, for the record, were GAZ 3, 5, 10, and 13. I...may like elves...a little too much.) And even as I sit here, other covers demand to be named. The very first Dragonlance adventure, the iconic Dragons of Despair? The Finder’s Stone trilogy? The first Ravenloft box? Dragon #147? Yep, he did those covers too. He was amazing.

But hoo-boy, we also have to talk about the not-amazing parts. Once Caldwell settled on a way of doing things, that’s how he did them. Points for consistency, but man, he had tropes. Even his tropes had tropes. He had a way of painting dragon’s wings. He had a way of painting swords and boots. He had a way of painting jewelry, and belts and coins—ovals upon ovals upon ovals.

And his way of painting women was with as few clothes as possible. Everything I said about Parkinson last entry? Yeah, that goes double for Caldwell. He never paints pants when a thong will do. His take on the reserved and regal Goldmoon—thighs as long as a dwarf and bronzed buttcheeks exposed—reportedly left Margaret Weis in tears. Magic-users (God, I hate that term) famously couldn’t use armor in D&D and AD&D, but Caldwell’s sorceresses pretty much stick to gauze just to be safe. And the Finder’s Stone trilogy I mentioned above? Yeah, the authors of Azure Bonds took one look at Caldwell’s cover art and literally had to come up with in-text reasons why the heroine Alias—one of the most surly woman sellswords in existence—would wear armor with a Caldwell boob hole.

Don’t get me wrong, I love cheesecake as much as the next dude. (Actually that’s not true; I came up in the grunge ’90s—our version of cheesecake was an Olympia brunette in three layers of thrift store sweaters reading Sandman while eating a cheesecake. Hell, that’s still my jam.) But context matters. The sorceress from “White Magic,” Dragon #147’s cover, may barely be wearing a negligee, but she’s also in the seat of her power and probably magically warded to the hilt—she can wear whatever she damn wants; it’s her tower. So no complaints there. But this cover’s pirate queen Porky Piggin’ it seems like an unwise choice. (The friction burns alone from clambering around the rigging…)

It’s clear from reading The Art of the Dragonlance Saga that TSR was trying to turn the ship around when it came to portrayals of women in fantasy, however slowly. And in Caldwell’s defense and to his credit, he definitely delivered women with agency—in nearly every image, they are nearly always doing something active and essential. They just tend to be doing it half-dressed.

Which is all a way of saying I dig this cover—the explosion, the churning sea (even if it does more look like snow drifts than waves), the sailors all running to the rail to look—but yeah, that pirate captain needs to put on some damn pants.

The Adventures: Before we get started, I have to note that though we’re only an issue in, already the magazine feels more noticeably like the work of editor Roger Moore. This is 100% a guess, but it really feels to me like Dungeon #1 was made of adventures that the Dragon office already had laying around, whereas Dungeon #2 was composed of adventures that Roger Moore and the new Dungeon team had more of a hand in sifting through. (He also has an assistant editor this time in Robin Jenkins, which had to have helped.) Even the cartography looks better. Again, I have zero confirmation of this, but the feeling is strong.

“The Titan’s Dream” by W. Todo Todorsky, AD&D, Levels 5–9

PCs visiting an oracle accidentally walk right into a titan’s dream and must solve some conundrums to escape. What an awesome concept this is! (Spoilers for “Best Concept” section below.) It’s a shame I don’t like this more.

First of all, dreamworld adventures are really hard to do well. And for them to work, there usually need to be real stakes—and not just “If you die in the dream, you die in real life!”—and/or a real connection to the PCs in your campaign. The latter, especially, is really hard to pull off in a published adventure; typically it’s only achieved through tactics that critics deride as railroading. (For instance, @wesschneider’s excellent In Search of Sanity does a great job of connecting the characters to their dream adventures...but it does that by a) forging the connection at 1st level, and b) pretty strongly dictating how the adventure begins and how the characters are affiliated. It works, but that’s high-wire-act adventure writing.)

Being a magazine adventure, “The Titan’s Dream” doesn’t have that luxury—it’s got to be for a general audience and work for most campaigns. That unfortunately means the default “Why” of the adventure—a lord with a child, a wedding, and an alliance at stake hires the PCs to chat with a wise titan—is little more than that: a default.

On top of that...I cannot get excited about anything Greek mythology-related. To me, just the fact I’m seeing it is a red flag.

Look, Greek mythology is why I got into this hobby. Hell, it’s why I got into fiction, period. (For some reason I somehow decided I had no use for fiction books targeted to my age, with the exception of Beverly Cleary. Then in 4th(?) grade, I got a copy of Alice Low’s Greek Gods and Heroes, and the rest is history.) But Greek mythology is often the only mythology anyone knows. When people think polytheism, that’s where most people’s minds go. Which is why, if you ever played D&D in the ’80s, I pretty much guarantee your first deity was from that pantheon. (In my first game, my first-level cleric pretty much met Ares and got bitch-slapped by him, because that’s what 4th-grade DMs do.)

So to me, putting Greek deities or titans in your adventure is the equivalent of putting dudes riding sandworms into your desert adventures—you can do it, but you better blow me away, because that is ground so well trod it’s mud. And this one doesn’t do the job.

The format is three dreams, each with five scenes. Parties will move randomly—a mechanic meant to represent dream logic (or lack thereof)—through these scenes, until all the scenes from one dream have been resolved. This is actually kind of fascinating, and I wonder how it would play at the table—I have a feeling observant players will dig it, but others may find the mechanism’s charm wears off quickly, especially if they have difficulty solving the scenes or get frustrated with the achronicity of events. I also like that every scene has a number of possible resolutions, so the PCs aren’t locked into achieving a single specific objective like they were stuck in a computer game.

But...I can’t shake the feeling of weak planning and execution (or even laziness?) that stayed with me throughout the adventure. Like, okay, the first adventure is a cyclops encounter out of the Odyssey. Cool! But then...why does the Titan follow it up with pseudo-Norse/Arthurian encounter? Did the Odyssey not hold the author’s attention? (Nor the Iliad, the Aeneid, or Metamorphosis? Really?) And then why is the third dream “drawn from the realm of pure fairy tale”? Like, were you out of pantheons? Horus didn’t return your calls? Or be more specific—why not German fairy tales, or Danish, or French Court, or Elizabethan? It feels like a class project where one group was on point, one group got the assignment a little wrong, and one didn’t even try.

Again, it’s not even that this adventure is bad—I honestly can’t tell if it is or not; I’m sure a lot of its success is determined at the table. And I could totally see throwing this at a party if I was out of inspiration that week or we needed a low-stakes breather before our next big arc. But the instant I think about it for more than a second, it all falls apart for me.

Have any of you tried this one? Let me know what you thought. And for a similar exploration into dream logic/fairy tale scenarios, I recommend Crystal Frasier’s The Harrowing for Pathfinder.

“In The Dwarven King’s Court” by Willie Walsh, AD&D, Levels 3–5

Willie Walsh is a name we’re going to see a lot more in issues to come—he’s a legendarily prolific Dungeon contributor, delivering quality, typically low-level, and often light-hearted or humorous adventurers issue after issue after issue. His first entry is a mystery with a time limit: A dwarf king is supposed to make a gift of a ceremonial sword to seal a treaty, but the sword has vanished. Brought to the king’s court courtesy of a dream, adventurers must find the sword and the surprising identity of the culprit before the rival power’s delegation arrives.

At first I was going to ding this adventure for its “What, even more dreams this issue?” hook...but here’s the thing with Walsh—never judge his modules until you reach the final page. Nearly every time I’m tempted to dismiss one of his sillier or more random adventure elements, it turns out that it makes sense and works just fine. In this case, the cause of the dream is haunt connected to the mystery, and I feel dumb for being all judgy.

So anyway, the PCs are given leave to search for the stolen object and the thief, but of course it turns out there is a whole lot of light-fingeredness going around. As Bryce (see below) puts it, “It’s like a Poirot mystery: everyone has something to hide.” This castle has as much upstairs-downstairs drama as any British farce, with nearly every NPC having either a fun personality and/or a fun secret (and with the major players illustrated by some equally fun portraits) that should make them memorable friends and foils for PCs to interact with. Not to mention the actual culprit is definitely a twist that will be hard explaining to the king...

GMs should be ready to adjust on the fly, though—a) it’s a lot of characters to juggle, and b) since the PCs are 3rd–5th level, the right spells or some lucky secret door searches could prematurely end the adventure as written. You may want to have some last-minute showdowns, betrayals, or other political intrigue outlined and in your back pocket if what’s on the page resolves too quickly.

Overall though, I’m a big fan of this adventure, and look forward to the rest of Walsh’s output. Also, given the dwarven focus and the geography of the land, this adventure could be a very nice sequel to last issue’s “Assault on Eddistone Point.”

“Caermor” by Nigel D. Findley, AD&D, Levels 2–4

Look at this author’s list of writing credits! Findley was amazingly prolific, and his work was pretty high-quality across the board, as far as I know. I particularly loved the original Draconomicon, one of the first and only 2e AD&D books I ever bought as a kid. I also loved his “Ecology of the Gibbering Mouther” from the excellent Dragon #160, and some of his Spelljammer supplements are currently sitting upstairs in my to-read pile, recently purchased but as yet shamefully untouched.

Now look at his age at the time of his death. Life is not always fair or kind.

(Speaking of unkind, man is the bio in this issue unfortunate in retrospect: “[H]e write for DRAGON® Magazine, enjoys windsurfing, plays in a jazz band, and manages a computer software company in the little time he has left.” As Archer would say, “Phrasing!”)

Anyway, this adventure is simple: An otherworldly force has been murdering the locals. The locals have pinned the blame on a handsome bard from out of town, and their own prejudices and general obstinacy are sure to get in the way of the investigation—that is, if the true culprits, some devil-worshipping culprits and and an abishai devil, don’t get in the way first.

All in all, this is a tight, well-written adventure, so I don’t have much to say about it, other than that if you like the idea of sending your party to help out some young lovers and save some faux-Scots/Yorkshiremen too stubborn to save themselves (and maybe slip in a valuable lesson about prejudice and xenophobia as well), this is the adventure for you.

One thing that does jump out to a contemporary reader, though, is the comically overpowered nature of the baddie pulling the strings in this adventure: Baalphegor, Princess of Hell (emphasis mine). Overpowered, you-won’t-really-fight-this-NPC happens with a lot of low-level adventures, when the writers want a story more epic than characters at the table can handle or are trying to plot the seeds for future evils. But still, any princess of Hell would already be a bit much...but an 18-Hit Dice, “supra-genius”, the Princess of Hell? Like, what the f—er, I mean, Hell?

If you use the adventure as written, the only way to have Baalphegor’s presence make sense is to eventually reveal that the area is an epicenter of some major badness. (Maybe that explains the lost nation of evil dwarves in the adventure background.) For a good model on how to seed early adventures in this matter, Dungeon’s Age of Worms Adventure Path and Pathfinder Adventure Path’s Rise of the Runelords AP, both from Paizo, are exemplars of small-town disturbances that eventually have world-shaking implications.

It’s also fascinating in retrospect to note Ed Greenwood’s massive impact in the hobby. Any article that appears in Dragon has the sheen of being at least semi-official, but it’s clear that Greenwood’s content was a cut above even that. In this case, an NPC from a three-year-old article of his is not just treated as canon, but also supplies the mastermind behind the adventure! It’s no surprise that in the following year his home campaign, the Forgotten Realms, would soon become AD&D’s newest and then its default setting.

Two final thoughts: 1) There’s some fascinating anti-dwarf prejudice in this article. Nearly every mention of dwarves paints them as exceptionally greedy and/or villains. And 2) how did one even begin to balance adventures in those days? This adventure is for “4–8 characters of 2nd–4th level.” There are a lot of difference at the extreme ends of those power scales…

“The Keep at Koralgesh,” by Robert Giacomozzi & Jonathan Simmons, D&D, Levels 1–3

One of the problems of BECMI D&D being known as “basic D&D” is that writers often assumed the players to be basic (that is, younger/new) as well. Which probably accounts for some of the early suggestions to the DM we get at the beginning of this adventure—like some pretty patronizing advice along the lines of not immediately announcing to PCs what the pluses are on their magical swords.

Fortunately, after that the article settles down and gives us Dungeon’s first real D&D adventure. In fact, not just real, but massive: 20 full pages of content—nearly half the issue! It’s a fully fledged dungeon crawl that has the PCs taking advantage of the summer solstice to open a shrine door that will lead them inside a long-ruined keep said to hold great treasure.

Now, I imagine in the coming installments it’s going to seem to many of you like I’m grading D&D adventures on a curve, because of my love for the system and the Known World/Mystara. That’s a fair accusation, but a better way to consider it is that I’m reviewing D&D adventures for what they are—adventures from a separate system, with a more limited rules system and palette of options than AD&D. You don’t go to a performance of Balinese shadow puppetry and compare it against Andrew Lloyd Webber; you look at it for what it achieves in its own medium. Since they appear side-by-side in the same magazine, comparison is going to be inevitable, but that’s with the understanding that AD&D was the kid coloring with the 64-crayon box of Crayola, while D&D was getting by with just eight.

On its own terms then, “The Keep of Korgalesh” is a decent, if not superlative, success. I love that it’s practically module-length and that we get three complete levels—a far cry from the previous issue’s side-trek-at-best, “The Elven Home.” We also get two new monsters, which absolutely fills my inner BECMI D&D player with glee. And I like that what starts as a dungeon crawl/fetch quest evolves into a “kill the big bad thing” and “find out what really happened to this city.”

There are issues, though. If the whole city was destroyed, getting to see some of it besides the keep would have been nice. Some of the ecology for the dungeon inhabitants is questionable. There pretty much wasn’t a single pool or fountain in this era of D&D adventure design that wasn’t magical, and this adventure was no exception. One of the new monster’s names makes no sense except that “tyranna” and “abyss” are cool words (I mean, I guess you could read that as “tyrant of the depths,” but still…) And there are painfully obvious borrowings from other works, especially Tolkien—a door that only opens at solstice, a lake monster, an orc with a split personality that is clearly a Gollum homage, etc.

What this adventure really needs is stakes—just something to give it a bit more oomph beyond the dungeon crawl. (Finding a blacksmith’s lost hammer is the hook offered in the adventure but it’s pretty flimsy.) Perhaps the PCs are some of Kor’s last worshippers, and clearing out the dangers here and resanctifying his temple is one of their first steps toward returning him to prominence. Maybe the PCs’ grandparents were involved in the city’s demise and restoring Koralgesh will restore the families’ honor. Or you could keep it simple and have a band of pirates or a rival adventuring group also trying to clean out the keep, turning it into a race (with the tyrannabyss causing the scales of fate to wobble at appropriately cinematic moments).

So the final analysis is this is a decent dungeon crawl upon which you can build a good adventure. The real reward of this module isn’t treasure; it’s finding out just what happened to Koralgesh. But for that to matter, it needs to tie into the PCs’ pasts, futures, or both.

BONUS CONTENT FOR KNOWN WORLD/MYSTARA NERDS: Kor is almost certainly a local name for the sun god Ixion. The chaotic deity Tram is probably a local version of Alphaks, though Atzanteotl is another strong candidate, especially since deceit was key to the pirates’ success. Koralgesh could be located somewhere on the Isle of Dawn, the northern coast of Davania, or an Ierendi/Minrothad Isle that those nations haven’t made it a priority to rebuild.

Best Read: “Caermor.” Nigel D. Findley was a pro.

Best Adventure I Could Actually Run with Minimal Prep: “The Keep at Koralgesh,” as a well-written, straight-ahead dungeon crawl. Every other adventure here relies on a pretty strong handle of very mobile NPCs and their motivations, or a Titan’s dream mechanics.

Best Concept: “The Titan’s Dream,” as noted above. It’s a great idea very worth exploring, even if I wasn’t about the execution we got in this case.

Best Monster: This was actually a monster-light issue. Despite some awesome art for the tyrannabyss, I have to go with the epadrazzil, a scaly ape from a two-dimensional plane of existence that has to be summoned via a painting. All of those details are just so wonderfully and weirdly specific it has to win. (Extra points for anyone who noticed the thoul—a classic D&D monster (though it did make its way into AD&D’s Mystara setting) born from a typo.)

Best NPC: Since this is a role-playing-heavy issue, there are a bunch of contenders, and the final verdict will go to whoever your party sparks to at the table. Obviously King Baradon the Wise should get the nod for [spoiler-y reasons], but I also really like the opportunity the executioner Tarfa offers, thanks to his incriminating goblet and how it might bring the PCs to the attention of a far-off assassin’s guild at just the right level.

Best Map: All together the maps from “The Keep at Koralgesh” form an extremely appealing whole. But for best single map I have to go for the palace of Mount Diadem—that is a bangin’ dwarven demesne.

Best Thing Worth Stealing: Jim Holloway’s illustrations of dwarves. Good dwarf, gnome, and halfling art is hard to find, and even the good stuff often leans stereotypical. While Holloway’s art is often humorous—I have a feeling he and Roger Moore jibed really well, though that’s totally a guess based purely on what assignments he got handed—his dwarves, especially in this issue, are fresh, specific, and unique. You could identify them by their silhouettes alone—always the sign of good character art. If you need an image of a dwarf NPC to show the players, “In the Dwarven King’s Court” is a great first stop.

Worst Aged: Female thong pirates on magazine covers. Also using the actual names of actual mental illnesses in game materials.

What Bryce Thinks: “This seems to be a stronger issue than #1, although half of the adventures are … unusual.”

Bryce actually almost likes “The Titan’s Dream,” confirming my loathing of it. He in turn loathes “In the Court of the Dwarven King.” Like me, though, he is pro-”Caermor” and sees potential in “The Keep at Koralgesh.” (Also credit where it’s due: I might have missed the condescension at the start if he hadn’t called it out.)

So, Is It Worth It?: If you’re a Clyde Caldwell fan, this issue might be worth searching out in print. So much of Caldwell’s work from this era was dictated by product needs, cropped and boxed up in ads, or shrunk down to fit on a paperback cover. So to get this cover in full magazine size, with only the masthead tucked up top to get in the way—that could be well worth a few bucks to you.

Also, if you’re BECMI/Rules Cyclopedia-era D&D fan (or know someone who is), again, this one might be worth having in print. “The Keep at Koralgesh” is a legit, proper BECMI D&D adventure, spanning 20 whole pages and with two new monsters to boot. I would have practically have cried if someone had given 7th-grade me this.

Beyond that you can probably just rely on the PDF. But both “Caermor” and “In the Dwarven King’s Court” have strong bones worth putting some modern muscle and skin on.

Random Thoughts:

The Caldwell cover painting was also used for the Blackmoor module DA4 The Duchy of Ten. PS: I’m not trying to tell you what to do or anything, but if you do happen to run across a physical copy of The Duchy of Ten or and of the DA modules, holla at ya boy over here.

Since this is our second issue, we now have a “Letters” column. Turns out Dungeon had been announced in Dragon #111 with a really detailed set of writer’s guidelines; most of the correspondence is questions re: those. In the process of answering, we get some surprisingly frank talk about payment. The $900 for a cover seemed low until I converted it to 2018 dollars, and ~$2,000 does seem right to my ignorant eye. I then made the mistake of converting my current salary to 1986 dollars and felt a lot worse about myself and what I’ve achieved.

Apologies this took so long to post. I had the issue read by early October and most of this review written with the next week or two after...but then I got involved in dealing with a 4.5 week hospitalization and aftermath...and then a second still-ongoing hospitalization...and even though I only had about four paragraphs left I just couldn’t find time to put a bow on it.

Notable Ads: The gold Immortals Rules box for D&D. (I also still don’t have that one yet, and Christmas is coming. Just saying, guys, if you happen to find one in your attic.) ;-) Also an ad for subscribing to Dungeon itself, starring “my war dinosaur, Boo-Boo.” No, really.

Over in Dragon: Beneath a glorious cover, Roger Moore is the new editor of Dragon #115, three authors (including Vince Garcia, who I like a lot) share credit on a massive six articles about fantasy thieves, a famous article proposing that clerics get the weapons of their deity (people were still talking about it in the “Forum” column when I was buying my first issues two years later), and a look at harps from the Forgotten Realms (notable because behind the scenes Ed Greenwood’s home setting was being developed for the AD&D game for launch in 1987.) A photographic cover and a 3-D sailing ship are served up in Dragon #116, along with maritime adventures, more Ed Greenwood (rogue stones), and articles for ELFQUEST, Marvel Super Heroes (Crossfire’s gang), and FASA’s Dr. Who game (looking at all six(!) doctors). (Incidentally, I had an Irish babysitter around this time who first mentioned Dr. Who to me—I wish I’d explored more but I was too young to understand what I’d been offered.)

PS: Yes, I’ve heard about the upcoming Tumblr ban. It is a terrible idea that will affect way too many of my readers. It shouldn’t affect me much (and I have all my monster entries backed up at the original site), but I will keep you posted as I learn more, particularly if I find you, my readers, packing up and going elsewhere.

#daily bestiary#patch has issues#pathfinder#paizo#3.5#dungeons & dragons#dungeons and dragons#d&d#dnd#ad&d#becmi#dungeon#dungeon magazine

95 notes

·

View notes

Link

via Politics – FiveThirtyEight

There is a story that Stanford University political science professor Jim Fishkin likes to tell about George Gallup, the man who helped popularize public opinion polling in America.

After the 1936 presidential election — which Gallup’s polling correctly called for Franklin D. Roosevelt — Gallup delivered a lecture at Princeton in which he argued that polling could allow voters from across America to come together, like in a New England town meeting, to debate and decide on important issues facing the country. As he saw it, newspapers and the radio would broadcast the debate, and polls would capture what people thought after having heard from all sides. It would be, to quote Gallup, as if “the nation is literally in one great room.”

Eighty-some years later, Fishkin says Gallup’s vision hasn’t quite held up: “He was right in that there could be a shared discussion and polling about it, but wrong in that the room was so big that nobody was really paying attention.”

But what if you could get the whole country into a more manageably sized room?

That is — quite literally — what Fishkin and his Stanford colleague, Larry Diamond, tried to do. Over the course of four days in September, in partnership with Helena, a nonpartisan institute that funded the event, and NORC at the University of Chicago, they gathered a nationally representative sample of 526 registered voters1 in a suburb of Dallas to talk about issues that Americans have said are important to them in 2020: immigration, health care, the economy, the environment and foreign policy. They called it “America in One Room.”

The aims of the project were lofty. If you gather all of America in one room and provide them with facts and a set of arguments from both sides of the political aisle, can respectful, moderated discussion change people’s minds?

The answer: Sort of.

In September, a nationally representative group of registered voters gathered to talk over some of the big issues driving the 2020 election.

Helena

There was some movement on the event’s five issues, as captured in the pre- and post-event surveys conducted by NORC, though how much movement differed depending on the question. Fishkin and Diamond found, for instance, that support grew among Republicans for proposals like increasing the number of visas for skilled workers and for less-skilled workers in industries that need them. And support for proposals like a $15 minimum wage and issuing $1,000 per month to all adults (a universal basic income) fell among Democrats.

But it’s unclear how lasting these changes will be, or even whether these types of events are the best way to encourage real political change. They’re not very practical, for one. Moreover, for people for whom these political issues hit close to home — those struggling to pay for health insurance, for example, or worried about family members being deported — the idea of engaging with the other side might seem overly idealistic, daunting or even useless. Some issues just don’t have much of a middle ground when you get down to the level of individual people.

Still, Diamond told FiveThirtyEight that if they could raise the money, they planned to survey the participants again in six or nine months to find out what, if any, changes had endured.

Many of the participants FiveThirtyEight spoke with, though, seemed to think that the emphasis on people changing their minds might be missing the larger purpose of an event like this.

“I don’t think people’s minds are changing,” said Susan Bosco, a retiree living in Fairfax, Virginia. “I think what we’re doing is respecting other people’s opinions more and not seeing them as ogres.” Robert Granger from Bristol, Tennessee, and Jamie Andersen, from Portland, Oregon, who were in Bosco’s group for the event, agreed, saying they had decided to attend so that they could better understand what makes people hold the opinions they do. “We all want to see our country succeed, regardless of race, gender or what part of the country you’re from. But we all have different ideas of how to get there,” Granger said.

One of the discussion groups talking about the economy and taxes.

Helena

And the survey results back them up. Pre- and post-event surveys found most people who came as Democrats left as Democrats, and the same with Republicans. But while the experiment didn’t make people change how they identify politically, it did seem to make them more understanding of those who hold a different view. As London Robinson of Chicago told FiveThirtyEight, many people in her discussion group made arguments that she expected given where they were from or their political party, but she was also surprised that people from different parties “think just like I do.” “I didn’t think they would think that way,” Robinson said. “It was breathtaking to see that.”

That’s something. Contrary to conventional wisdom, most Americans don’t watch and read only partisan news outlets. But the country is largely segregated by politics — most people live near and work with like-minded souls, and many dislike their counterparts from across the political aisle. So the America in One Room gathering was designed to give people a low-stakes environment to debate politics, because as Diamond said, “These are dangerous conversations out there in the real world.” For instance, a 2016 Pew Research Center study on partisanship found that 55 percent of Democrats said the Republican Party makes them “afraid,” while 49 percent of Republicans said the same about the Democratic Party.

In a convention hall outside Dallas, though, getting everyone into the same room seemed to change that some:

Participants didn’t identify as more politically moderate after the event, but there is evidence that they viewed those on the other side of the political aisle more positively. When asked to rate their feelings toward the other party on a scale of 0 to 100 — with higher numbers meaning warmer feelings — Democrats’ views of Republicans improved by nearly 12 points on average. For Republicans, the jump was even larger, almost 16 points.2

Before the event, people were also more likely to say that the other side was “not thinking clearly.” On a scale of 0 to 10 — where 10 was strongly agreeing with the statement that your political opponents are not thinking clearly and 0 was strongly disagreeing with the statement — the average response dropped from 6.2 to 4.7, indicating that even if participants didn’t agree with each other more, they had more respect for those they disagreed with.

Participants also left the event with a better opinion of democracy and their place in it. They were asked to rate how well they thought democracy was working on a 10-point scale, with 0 meaning that democracy was working “extremely poorly” and 10 being “extremely well.” On average, respondents’ ratings increased by 1.6 points. There were also increases in the number of respondents who agreed that public officials care a lot about what “people like me” think, and in those who felt they have a say in what government does or who thought that their opinions about politics were “worth listening to.”

Take Rob Snyder of Murrells Inlet, South Carolina, one of the participants FiveThirtyEight talked to. He emailed after the event to say that while he’d always considered politics as something “better left for someone else to worry about,” his experience had made him feel like he was no longer just “one person with one voice and one vote.”

And finally, the event may have gotten us one step closer to Gallup’s vision of a more informed and empowered electorate. In the post-event survey, respondents were asked seven multiple-choice questions testing their political knowledge about things like which political party holds the majority in the House and Senate, and what the major provisions of the Affordable Care Act are. And on average, participants answered one more question correctly after the event. Participants also skipped3 about one fewer question on average, suggesting they knew (or thought they knew) the answer to more questions.

For some respondents, like Veronica Munoz of Los Angeles, the event sparked an interest in being better informed. Munoz said that while she was familiar with some of the proposals being discussed, there was a lot she didn’t know, so she was glad she had come. “Now I’m more interested in reading the newspaper to find out what’s going on with our politics and our economy and policies than I was before,” she said.

Granted, the real-world implications of these findings are limited at best. Most people don’t have the opportunity to spend their weekends debating big political issues with a group that’s carefully selected to be representative of their fellow Americans — and that’s unlikely to change anytime soon. But in an era in which we’re increasingly polarized as a country and even facts are under fire, the idea that an event devoted to political debate can increase knowledge, decrease skepticism of the other side, and bolster participants’ faith in democracy — and their place in it — certainly seems like good news.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Spiral Q Peoplehood and Participatory Puppet Performance, Part 3

(Jump here for Part 1 and Part 2)

How it is created and why that matters

In Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century, Henry Jenkins writes that “[p]articipatory culture shifts the focus of literacy from individual expression to community involvement.” Peoplehood, as an event that seeks to involve a community/ies expression of itself/themselves through parades and pageantry, is an interesting context to explore participatory culture and its potential. The lens of participatory culture is also useful to look at Peoplehood in order to understand its creation process and why it matters.

A participatory culture was originally defined by Jenkins as one:

With relatively low barriers to artistic expression and civic engagement

With strong support for creating and sharing one’s creations with others

With some type of informal mentorship whereby what is known by the most experienced is passed along to novices

Where members believe that their contributions matter

Where members feel some degree of social connection with one another (at least they care what other people think about what they have created)

Researching participatory cultures over time - through fan communities and activists movements primarily - Jenkins and Sangita Shresthova have been interrogating the possibilities and challenges through the Civic Imagination Project where “imagining community ... is actively generating new cultural symbols to describe their relationship with each other. Imagination is seen not as a product or a possession ... Rather, we talk about imagining as a process.”

Supporting imagining as a process and creating new signs and symbols through sharing stories are core ideas of the Spiral Q Puppet Theater. Through low-stakes and accessible object creation and performance, participants can make and remix their everyday reality alongside others. In its mission statement, Spiral Q states that “We imagine a city whose streets reflect the full spectrum of its residents’ creativity. We see a responsive and engaged society that rallies consistently to overcome the challenges of discrimination and oppression. We envision a world of abundance that mobilizes its resources to nurture shared vitality.” When sharing the power of the 2019 Peoplehood Parade and Pageant, co-director Jennifer Turnbull describes the process that surfaced the story and related puppets:

This year we partnered with three local grassroots activist groups .... Through pageantry we were able to show the through line connection they all had to health, housing, self determination and freedom.

In working to design for shared power and participation, Tracy Broyles - the Director of the Q after Matty - describes the ways that affirmation, imagination and practice are so important. Everyone has a role to play, she says, and that “any moment someone enters the process is the right moment” (TEDx Philly, 2012). Affirming participation, and providing many points of entry, are key ways that the Q attempts to build Peoplehood and, according to Jenkins, are defining features of participatory practice.

Another central element of participation, according to Jenkins, “is that we participate in something larger than ourselves, however we want to imagine what it is we are participating within” (Jenkins, Confessions of a Aca-Fan post, 2019). Eli Nixon, in 2003, describes themselves and this work as part of a larger whole:

I'm just a small column of flesh and bones. I can build something that's larger than me... I really get a kick out of it as a way to tell stories and to make humans bigger than they are or to examine different parts of everyday people's lives in a way that I think is more interesting than real life. It's an awesome way to interpret who we are.

Looking at the outcomes of a participatory process is another way to assess its viability (Jenkins, Confessions of a Aca-Fan post, 2019). Tracy describes the ways that people literally “spiral out of q.”

What we see is this a place where people test these things and then go out into the world. Okay so now [they] might not use puppets and art and all these things ... but they have got this place, a sense of direction, a sense of safety, a sense of community has formed around that individual or that community and then that cause or idea ... can really gain some traction and go off and become a movement that’s working on a policy level or at a community organizing level or simply building beautiful things.

In working to refine a definition of participatory culture in a fractured media environment, Jenkins and his colleagues bring a critical focus to the mix, ie. “Which members of a dis-privileged group find their power position strengthened through the participatory process?” A complex question but also critical for the Q. In one example, we find an interview 2003 with Jennifer Hilinski, a therapist at Girard Medical Center, who was asked about her experience working with a group of men in recovery in collaborating with the Q on Peoplehood the previous fall.

"The common story was about recovery and getting back into the real world as contributing members of society.” Jennifer said, “And they took a theme of going from hell -- which was the streets and using -- to this kind of angelic transformation and re-entering the world and the streets but not as street person” (2003). Since that time a group from Girard Medical Center participate in Peoplehood every year, leading with their giant backpack puppets of transformation.

Conclusion

In the 2008 Peoplehood newsletter, the process of building Peoplehood is described by Tracy as “flawed, just like our democracy.” And we are reminded by the Civic Imagination Project that “If stories can inspire and empower social change, stories can also shatter communities, feeding our fears and suspicions, re-enforcing stereotypes in particularly vivid ways.” Jenkins and his colleague also tell us that the fostering of participation is vital while fragile and requiring care:

participation could also be finished. It could come to an end. Democracy, as a political and social practice, is not a given, but could cease to exist. ... This is why participation and democracy need to be actively protected, and not just silently appreciated.

We know that object performance, storytelling, or even parades and pageants which historically have also been used in fascist and authoritarian settings, do not create democratic space themselves. Instead democracy, through an ethos of participation, needs to be fostered.

Peoplehood, as a creative space for democratic storytelling and cultural remixing, is one such opportunity to intentionally test and tinker with the possibilities and challenges of participatory practice. It allows individuals and groups to come together, figure out what is needed when they work together, and then bring it into being through object creation, puppet performance and joyful demonstration.

In 2003, Matty Hart described Peoplehood’s parade and pageant as "secular cultural ritual[s] ... that are actually really kind of sacred and really really old.” These rituals, when built in shared and participatory ways, situate puppets and objects as powerful vehicles for fostering civic imagination through the creation of new cultural symbols and understandings.

As Jennifer writes about the Q in a Nonprofit Executive Leadership Institute newsletter: “we create space for the unknown. You just don't know what you don't know.”

Want to read more about Peoplehood and Spiral Q? Check out Part 1: What is Peoplehood? and Part 2: Elements of Performance.

Images courtesy of spiralq.org and my personal collection.

0 notes

Text

Camelot with Mathew Hannibal Butler

This week we chat with Matthew Hannibal Butler about which of life's truths can be gleaned from the Kennedy-favourite musical - Camelot!

"A 1993 review in The New York Times commented that the musical "has grown in stature over the years, primarily because of its superb score ... [which] combined a lyrical simplicity with a lush romanticism, beautifully captured in numbers like 'I Loved You Once in Silence' and 'If Ever I Would Leave You.' These ballads sung by Guenevere and Lancelot are among the most memorable in the Lerner-Loewe catalogue. King Arthur supplies the wit, with songs like 'I Wonder What the King Is Doing Tonight.'"

Listen to Matthew's Podcast here: thatsnotcanon.com/deliciouswordsandwichpodcast

FURTHER READING:

Camelot (musical)

Camelot (film)

Alan Jay Lerner

Frederick Loewe

The Once and Future King.

Kennedy Administration

Julie Andrews

Richard Burton

Robert Goulet

https://open.spotify.com/album/5Fp6Y3gNufwzUeEBxuOZpo

https://music.apple.com/us/album/camelot-original-1960-broadway-cast-recording/158476378

Camelot: The Musical, A History By Matthew Hannibal Butler

By Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Lowe

A History By Matthew Hannibal Butler

Camelotis an oft forgotten and underrated musical masterpiece by the iconic duo Lerner and Lowe, first premiering with Sir Richard Burton as King Arthur and Dame Julie Andrews as Guinevere, with Robert Goulet as the dashing Sir Lancelot. They did not have these titles when it premiered in 1960 at the Majestic Theatre, but I thought it was a nice touch considering their royal counterparts.

Camelotis inspired by the definitive Arthurian novel The Once and Future King by T.H. White, a four book saga consisting of the iconic Sword in the Stone,The Witch in the Woods, The Ill-Made Knight and finally The Candle in the Wind. The musical mainly focuses on the events of this final instalment detailing with the last weeks of Arthur’s reign, the machinations and ultimately revolts by his son Mordred, Guinevere and Lancelot’s demise, and the tragic king’s final reflections of right and wrong. For all its levity, what I adore about this musical’s story is its choice to focus on one of the greatest tragedies in western folklore: The Fall of Camelot.

As you can tell, I am an Arthurian lore fanatic, and T.H. White’s book, in my opinion, is the best classic interpretation of King Arthur. A tragedy of this musical is, in my opinion, that it did not inspire more interest in White’s marvellous book.

Lerner and Lowe, as well as Camelot’s original director Moss Hart, were all coming from the chaotic universal success of their musical My Fair Lady and their musical film Gigi. Tensions and stakes were high. ‘Twas the classic tale of ‘What’s next?’ after tremendous success. Hart and Lerner decided upon T.H. White’s quintessential fantasy published in 1958 for their next musical. For a very small background on White, he wrote the bulk of the series in Ireland as a conscientious objector of the second World War between 1938 and 1941, thus writing a distinctly anti-war, anti-violent story engrained with western identity. To adapt this at this time, just before Kennedy’s escalation of the Vietnam War is a right proper noble gambit worthy of Arthur, let me tell you.

Frederick Lowe initially had no interest in the project, but agreed to write the score on the condition that, if it went badly, it would be his last. This do or die spirit, I found, reigned throughout the whole production, in spite of everything, and made it the suitably tragic triumph that it became. There were several problems plaguing the production, not least of which was Lerner’s wife leaving him during its writing, causing him to seek medical attention. I can’t help but surmise this informs one of the most poignant moments of the play, when Arthur realises the feelings shared between Lancelot and Guinevere and he thus soliloquises about his love for his kingdom, his purpose and in truth his friends will ensure that they will together nonetheless prevail through all challenges.

During its initial previews, it overran drastically. It was supposed to be two hours and forty minutes, instead it clocked in at a casual four and a half hours with the curtain coming down at twenty to 1 in the morning. Lerner later noted, “Only Tristan and Isolde equalled it as a bladder endurance contest”. In spite of this trial, positive reviews still generally prevailed though with an insistence much work needed yet. With drastic editing to be done, Lerner was hospitalised for three weeks with a bleeding ulcer, then Hart tagged into the hospital just as Lerner tagged out with his second heart attack.

Cutting it down became a stubborn quest, for Lerner did not want to make dramatic decisions without Hart. Alas, Jose Ferrer of Cyrano de Bergerac fame was unable to step in, and so it goes as Lerner wrote: “God knows what would have happened had it not been for Richard Burton.” He accepted cuts and changes all while radiating faith and geniality to calm the fears of the cast. A King off and on the stage. Meanwhile, ever the Queen, last minute changes were so dramatic that literally at the last minute before the New York preview Julie Andrews was given the iconic number “Before I Gaze At You Again”, simply remarking “Of course, darling, but do try to get it to me the night before”.

With Hart returned, literally and figuratively, cuts and edits continued. The New York critics’ reviews of the original production were mixed. However, My Fair Lady’s fifth anniversary approached and Ed Sullivan wanted to do a tribute segment on his show. Lerner and Lowe chose to mainly perform highlights from Camelot on the show, and so it was their new show achieved an unprecedented advance sale of three and a half million dollars.

Now that’s perseverance, even when things are going haywire, you raise the stakes even higher! This served also to make Robert Goulet a household name with his signature ballad, “If Ever I would Leave You” becoming the Once and Future Belter.

Camelot had its initial run. In such time, it gained many an award, including four Tony Awards, with Richard Burton for Best Leading Actor, naturally Best Scenic Design and Best Costume Design, with Franz Allers for Best Conductor and Musical Director and finally with Julie Andrews being ROBBED and fetching a nomination for Best Leading Actress.

Robert Goulet became a STAR with appearances on the Danny Thomas and Ed Sullivan Shows, and the stellar, and frankly best, original cast recording became a favourite bedtime listening for President John F. Kennedy, who was Lerner’s classmate at Harvard University. His favourite lines from the final reprise of the titular song became well-documented, and forever associated Camelot, with all its idealism and sheen, with the Kennedy Administration.

Small sidenote, to enjoy this tremendous score, the best buck starts and ends with the original cast soundtrack.

Alas, the obstacles encountered in producing Camelot were hard on the creative partnership of Lerner and Loewe, the show turning out to be one of their last collaborations. Camelot was indeed Hart’s last Broadway show, dying of a heart attack on December 20, 1961.

Since the original production, Richard Burton reprised his role as Arthur with Christine Ebersole as Guinevere and Richard Muenz as Lancelot. Then ‘twas revived in 1981 with Richard Harris as Arthur, Meg Bussert as Guinevere, Muenz once more as Sir Lancelot. This version can be found three parts on the YouTubes. Harris starred in the tragic for all the wrong reasons film, but proved he was the jewel in that particular crown for he took the show to tour nationwide with Muenz. A curious Broadway Revival also ran in 1993 with Robert Goulet now King Arthur.

There was then in 2007 Michael York as King Arthur, Rachel York, no relation, as Guinevere and the disgraced James Barbour ironically as Lancelot.

Alas, I have not been able to see Michael York as King Arthur, as that is inspired casting.

The final production I have had the honour of seeing was in 2008, since alas taken down from the YouTubes, where the New York Philharmonic presented five semi-staged concerts of Camelot with Gabriel Byrne as a more contemplative and subdued King Arthur, Marin Mazzie as Guenevere, and Nathan Gunn as Lancelot. What made this production stand out for me was it didn’t overdo anything, as this musical can oft be overwhelming, and also it featured Christopher Lloyd as Pellinore, a role I feel he was destined to do. Oh, if only they had done a spin-off adventure story starring Christopher Lloyd as Pellinore in his endless hunt for the Questing Beast.

All in all, the history of Camelot I think reflects it perfectly for better or ill. It is not a universally appealing production. In my opinion, it was never destined to be, considering its content and style. It is very chatty, pontificating and philosophical, yet with its simply magic score, a lush fantastical world, sweeping tragic romance and swashbuckling glory, when it connects with people it connects as firmly as the sword in the stone.

Like us on Facebook! Follow us on Twitter! Support us on Patreon!

Email us: [email protected]

Visit our home on the web thatsnotcanonproductions.com

Our theme song and interstitial music all by the one and only Benedict Braxton Smith. Find out more about him at www.benedictbraxtonsmith.com

#broadway#nyc#music#musicals#jazz#overture#diva#lifelessons#dance#choreography#new york#theatre#performance#stage#thespian

0 notes

Text

A Brief History of the Citroën 2CV – Everything You Need To Know

A Farm Cart And The Citroën 2CV

Legend has it that the germ of the idea that would become the Citroën 2CV was sown in the mind of the Vice-President and Chief of Engineering and Design of Citroën, Pierre-Jules Boulanger, one rainy afternoon when as he drove along a narrow French lane he found himself stuck behind a farmer’s horse and cart which was moving at horse walking pace.

Boulanger could have simply become annoyed, which would have done no-one any good. But he didn’t, instead he started thinking like a car manufacturer, and asked himself the question “Why not offer French farmers a better mode of transport?”

This was a sensible question, not only to make traffic move more quickly on French country roads, but for the benefit of the farmers. A horse requires a significant amount of maintenance including feed and vet bills. But a car could be built that was low maintenance, easy to start, easy to drive, and a whole lot faster than a horse at walking pace.

In his mind Boulanger decided to get the boffins at Citroën working on the design of just such a vehicle. It didn’t need to be fancy, but it did need to be cheap: and it had to do the things farmers needed to do reliably day after day, year after year.

The Citroën 2CV Design is Formulated + Prototypes Built

Boulanger sat down with a sharp pencil and clean sheet of paper and began thinking through the concept for the new car. That thinking did not begin with a car design but instead was based on Boulanger’s thoughts on what a farmer would need a vehicle to do.

In this sense his design analysis was somewhat different to that used by Dr. Ferdinand Porsche when he created the Volkswagen Beetle. Porsche’s design began with concepts for a car and those ideas were steered by none less than Adolf Hitler, who had very definite ideas of what the car for his people should be. Boulanger on the other hand was free to do his task analysis unencumbered.

Boulanger did not come up with a pencil sketch of the new car, instead he came up with a list of requirements for it. This set of requirements included that the car had to be able to transport up to four passengers, it needed to be able to cross a freshly plowed field with a basket of eggs on the back seat without any of the eggs getting broken, that the car should be able to comfortably be driven on the worst of French potholed muddy roads, and that it should have the load carrying capacity to take a 50kg sack of produce or a full cask of wine to take to market.

Additionally Boulanger specified that the car have fuel consumption of not less than 3 liters per 100 kilometers, which is 80 miles to the US gallon or 95 miles to the British Imperial gallon, have a top speed of 60 km/hr, and be easy for women to start and drive. He also decided that the car should require minimal maintenance and that any servicing work or repairs must be kept inexpensive and affordable: it had to be cheaper to run than a horse.

These were the specifications that Pierre-Jules Boulanger gave to his design team in 1936 and some of them probably thought he was just a trifle mad when he referred to it as “an umbrella on wheels”, but he was the boss, and what the boss wanted was what the boss was going to get.

The design team charged with creating this quite unique vehicle included André Lefebvre as the chief engineer and Italian stylist Flaminio Bertoni. They referred to the car as the TPV which stood for “Toute Petite Voiture” (English “very small car”).

The work on the car design proceeded in absolute secrecy. The design team initially used a single cylinder motorcycle engine and bodywork made of aluminum, with magnesium being used in some parts. During the 1930s it was thought that aluminum production was to become much cheaper and so it was expected to be a durable and inexpensive material to use in car production.

Similarly the downsides of using magnesium, especially its propensity to burn rather well, were not yet well understood. The chassis was to be a simple ladder frame while various systems were tried in the search for a suitable suspension system.

The most complex of these was created by Alphonse Forceau and it consisted of a leading arm front suspension and a trailing arm rear, the whole sprung by a system of eight torsion bars located beneath the rear seat. These torsion bars comprised one for the front suspension which was connected by cable, one for the rear, an intermediate bar for each side, an an overload bar for each side.

The rationale behind this complex system was that the overload bars would become active when the car was loaded with three or more people or cargo. This suspension would not be carried through to the post-war production cars.

The then bankrupt Citroën company had been taken over in 1934 by the Michelin tire company and Pierre Michelin became president of Citroën at that time. Michelin became involved in the design and creation of the Citroën TPV and as his tire company were working on a new concept for passenger car tires, the radial tire, he wanted that more advanced tire technology to be used in the TPV. Michelin created their first radial tires in a special size specifically for the needs of the TPV and so tires and suspension were jointly created to compliment each other.

A feature that was not carried forward to production was the use of hammock type seats which were suspended from the roof. These moved around with vehicle motion and proved to be most unsatisfactory so they were replaced with conventional steel tube frame seats.

Boulanger was determined to be highly involved in the TPV project and he created a department whose job it was to weigh each and every component and to try to find ways to make each one lighter. The project was top secret, Boulanger did not want rival car makers Renault or Peugeot to get wind of it or to start working on their own versions.

Pierre Michelin was killed in a car crash in December of 1937 so Pierre-Jules Boulanger became Citroën’s President. By this time 47 prototypes had been built and tested and the TPV design finalized. A pre-production run of 250 cars was undertaken and completed by the middle of 1939. These cars had just one headlight and one taillight because that was all French law required. The plan was to debut the car to the public at the Paris Motor Show to be held in October 1939. Publicity materials were prepared and the car was re-named the Citroën 2CV ready for its launch.

youtube

It was at this point that one of the most significant events of world history took place. Adolf Hitler ordered his military to invade Poland on September 1st, 1939 resulting in both France and Britain declaring war on Nazi Germany on September 3rd, 1939. France took military action against Germany on September 7th, 1939 and moved troops with armored support into the Saar and up to the Siegfried Line. This was to be short lived however and on September 17th the French withdrew, heralding in the period known as the “Phoney War” which the French referred to as the “Drôle de guerre” (Joke of a war).

This was a situation in which the French knew they were facing a menace so dangerous that the future of their nation was at stake. Suffice to say that the planned October 1939 Paris Motor Show was cancelled as France began preparations for what would become the fight for her life.

Hiding the 2CV From The Nazis

By May of 1940 the German Army had brought the British Expeditionary Force to Dunkirk from where 330,000 British troops were able to be evacuated. By July of that year the Germans has succeeded in occupying the northern part of France, including Paris, and Pierre-Jules Boulanger had to make some major decisions about how his company would deal with the new Nazi German occupiers.

One of his first decisions was to hide every trace of the Citroën 2CV so the Nazis could not steal and gain advantage from the technology. The prototypes and pre-production cars were either destroyed, buried, or hidden. The plans and machinery to build the cars were requisitioned by the Nazis who packed them into railway wagons ready to steal them away to Germany. However, help of the French Resistance these machines were re-labeled and sent off to various locations in France where they were hidden, hidden so effectively that Boulanger was not sure he would be able to recover them once the pesky Nazis were expelled from his country, as he earnestly hoped they would be.

Pierre-Jules Boulanger was so resistant to the Nazis that they labelled him an “Enemy of the Reich”, a title that he no doubt thought perfectly appropriate, but which put his life in danger. He and his countrymen endured four years of Nazi occupation until the D-Day landings in mid 1944 and the eventual defeat of the Nazis on May 8th, 1945.

With the war behind them France began the process of recovering from its ravages, and a new Citroën 2CV was to be a vital component in that recovery.

The Perfect Car for Post-War Europe

With the ending of the occupation of France in 1944 the French people elected a socialist government, as did the British people. The result of this for the French car industry was government restrictions on what they could or could not do. The new French government nationalized car maker Renault and put policy for car making into the hands of a former car industry executive Paul-Marie Pons who’s plan for the French car industry was called the “Pons Plan”.

Under this plan the only company permitted to make cars for the lower priced end of the market was to be Renault. Renault had been working on their new Renault 4CV model, which was in many respects similar in concept to Dr. Porsche’s Volkswagen and thus subject to the same limitations, and amid the post-war political wrangling Dr. Porsche was forced to be involved with Renault for a time.

So while the political machinations went on Citroën were forced to shelve their 2CV and just produce their Traction Avant. Boulanger and his team were not idle however but had spent the war years and post-war years working on improvements to their pre-war design. The multi torsion bar suspension was gone, the water cooled two cylinder horizontally opposed engine was replaced with a 375cc air cooled one designed by Walter Becchia who was also charged with designing a new gearbox to go with his new engine.

Becchia created a new four speed gearbox and told Boulanger that the fourth gear would act as an overdrive to assist with getting the required fuel economy. The bodywork was re-modeled because aluminum had become expensive and so the car was now to be made of steel.

The Pons Plan was to cease by 1949 and Citroën lost no time in getting the newly designed 2CV into the public gaze for the first time. The 2CV made her debut at the Paris Motor Show of October 7th, 1949: ten years after the planned debut of the pre-war TPV based 2CV.