#also the multiple layers of character each being self centred for their own reasons and tani being the only real one

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

hello winsnow

did you know I saw a death in the gunj just yesterday

how did you like it omg

#unsolicited opinion ->#it was such a visual treat i LOVED every frame of that movie#AND THIS IS HOW YOU GRT A MULTISTARRER MOVIE DONE ABSOLUTELY CHEFS KISS#not one character i didn't like#the manjari feeding the puppy scene the wrestling one the poornima scene (i was afraid they're going to do the looking down by kalki on her)#and i love stories where a family/friends are on vacation and something happens likr that's the theme i imagine if i ever did a rome#also the multiple layers of character each being self centred for their own reasons and tani being the only real one#the scene i most resonated was chutu coming back after falling down the pit but he sees everyone's busy and no one really cares like yeah

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

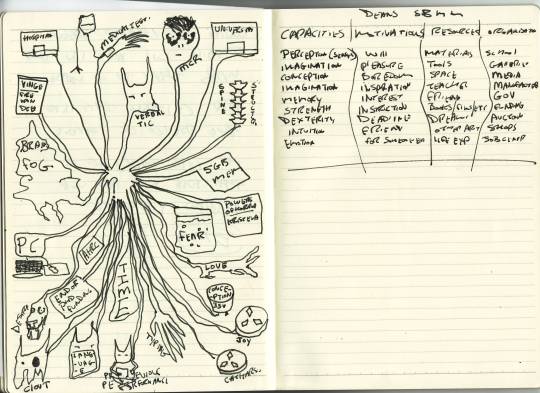

Dean Kenning, Social Body Mind Map

I just finished reading and making notes on (using the Digestion System I employ to get around my badly limited memory, which is i think detailed in an earlier post) a paper shared with me by the artist and lecturer Dean Kenning. I’ve known Dean’s work for a while, we’ve been on panels and in exhibitions together going back 5 years or so, but this is the first time I’ve been able to got through a text to understand this system which he uses in teaching. I’m going to attempt to summarize it briefly here, and then talk about what happened when I tried the system myself.

Dean sets up the context for the workshop against increasing pressures in the UK on art education. The system of education in this country is primarily based around learning, recalling, and appling pre-existing methods and facts on demand, to satisfy predetermined outcomes. This is a problem because it is both incompatible with learning art, but also therefor discounts art and the definition of “thinking” it embodies. The thinking in art is generative, rather than prescriptive. There are ideological reasons for this which Dean doesn't go into but which should be fairly obvious in relation to school as site of labour discipline and enforcer of pre existing hierarchies of thought and power.

The “Social Body Mind Map” is method of understanding an artwork in particular, and art making in general as not arising from either a pre established set of ideas, or from an inscrutable and unknowable mystical self. It does this through the use of “the diagram” which i will return to, but first the aim of the workshop which this system is delivered to students by is characterised within its name, and the pairings of the four words. The “Social Body” reminds us that this is primarily about understanding self not as an autonomous individual but as the expression of multiple flows through one’s body connecting to things outside of it over time. The “self” (and Dead draws from Deleuze here) is better understood as an area where possibilities and influences converge. I wont go into more detail than that, as explaining this is in part what the workshop does. the second pairing is “Body Mind” and this emphasises that the thinking is something we do with our bodies rather than in some abstracted upper hierarchy. In fact Dean proposes the SBMM is a process of thinking through a diagram. Finally the paring “Mind Map” is a recognisable one to most students and is there to add a recognisable position to begin from. Dean’s mind map is not the same as the spider diagrams we might learn in school though for an important reason. Normally the mind map begins with a clear central position, the subject being “brain stormed”. Dean rightly points out that this standard method generally results in the reinforcement of existing structures, it favours cliches especially at first. Dean’s mind map will change this, by having the central position occupied by a partially unknown quantity. This unknown quantity will be “the art work”, which can be a completed, in progress or future one. Dean’s aim for this is as already stated to allow art works to be understood not as the reflection of some static self but as "generative of a subject”. The aim is also to articulate the “thinking” involved in art which is also generative. Finally, in order to achieve the latter, the workshop uses the former to “alienate the student from their work”, to make the artwork strange and not simply a “reflection” and therefore grant them agency in the process of production of thought.

Workshop stage 1

the workshop begins by prepping the participants to think of where an artwork arises from other than just as a reflection of some unknowable constant self. Dean draws up a series of headings under which as a group they list the things which answer broadly the question “that facilitated this artwork coming to be?” the headings are

Capacities (things like: perception, imagination, strength, emotion etc)

Motivations (things like: Will, pleasure, boredom, instruction, deadlines)

Resources (things like: materials, tools, support from teacher, friends etc)

Organisations (things like: school, galleries, manufacturers, government etc)

So thinking about the production of the artwork moves from “I used my imagination” alone, to a series of statements such as “i used perception of the feeling of clay to see what forms it could hold without collapsing” and “The government set a syllabus which means is followed by my teacher who sets the deadline of two weeks to produce this artwork” and so on.

workshop stage 2

Dean then leads and example mind map, having already primed the students to think about their work in terms of these networks. the mind map begins with a “?” in its centre, and Dean tracks the influences which converge in this central point which is procedurally redrawn as “the artwork”.

Students then do their own, on their own, drawing on large paper this network. of factors which caused this artwork to be. Dean has some good examples of how a student, whos central image the wardrobe grew a giant toe in the drawing. The toe is in fact the act of student stubbing their own toe against the wardrobe in the dark which has identified as a factor in why they were drawn to make an artwork about it.

Dean’s recounting of conversations with students show that this workshop serves to uncover unknown or disregarded factors in the production of artworks. its described as “digging up hidden roots”. I think this is really important, I very much remember the feeling of art production as something “mysterious” in the sense that it was obscure. Following that pop cultural ciche of art just arising from some internal genius, that art was a reflection of the character or soul of the person making it. The process of production of ideas was not something I ever saw discussed in any art school I studied in including at Masters level. I understood in the second year of my MA that emotions where important, specifically that I could not make work when anxious, and I also developed rules around when during its cycle of development/production/reflection I would analyse a work (I’m currently deliberately breaking this rule, having adhered to it for over 10 years, specifically so I can understand it better, but thats another post)

Finally what also of note, is the manner in which the capacities/motivations/resources/organisations are connected to the alienated central artwork in the diagram also become important. As with everything in Dean’s system, there’s no prescribed way to do it, but in drawing out a line as a big toe, or casually decided as in mine to draw “fear” as the contents of a specimen jar this opens up further layers of reflection. This is a process of achieving that art teacher mantra of “letting go”. How you draw the limbs or tentacles becomes important without being anxiety provoking up front.

Final final note, as stated all of the system is adaptable and emergent. The lists of capacities etc as just an example, and they are generated with the group including the potential for entirely new categories. I copied Deans example list into my notebook above, and used both that and further examples as and when i thought of them .

My SBMM for “Ok, Welcome to the black parade”

OWTTBP is an artwork I started, and then deliberately let stall and left incomplete a couple of weeks ago because I wanted to write about the process of making it (even though this breaks a rule I’ve long followed, which is to not take apart works in progress, but to only analyse my works when there is at least one completed work between them and what I am working on now, my “one work buffer” rule). Reading Dean’s model for SBMM seemed like a perfect opportunity to work on this Reanimator corpse that I had left partially assembled, and also understand the process Dean is talking about better through employing it.

[Briefly, the “artwork” as it stands is a short science fiction story, written to an arbitrary formal constraint of 5 line paragraphs for the majority of the text. There are two points where this 5 line pattern deviates. firstly there is a section where the paragraphs all begin “You wake up...” for 7 paragraphs (there are around 50 of the 5 line paragraphs, paras 31-37 begin with “you wake up”. Secondly, after the narrative in the 5 line paras ends, there is an epilogue, which loosely sticks to 2 line paras, and has a different tone of voice. The artwork so far exists as this narrative, and a structure whereby I want something to happen between each of those 5 line parars (excluding the block which begin “you wake up”, which are back to back, in the manner of the scenes of strobing in and out of consciousness we are familiar with in cinema) which pulls the audience out from the narrative into an unstable space. Likewise there will be unstable space between the paras of the epilogue, but where I understand the former unstable space to be disordered but partly intelligible, the space between the epilogue paragraphs should be utterly ahuman.]

Above in pink is a diagram I had already developed (there is another one in the post before this) on my own to try and understand the art work I had made. the Diagram using SBMM is right at the top of this post, drawn by hand in my notebook. What became apparent when drawing is that the diagram was going to be much larger than i had space for. There are threads which I felt dissatisfied with because i knew there was so much more detail which had been left out due to the “resolution” I was working at. For example, the first thread I drew was the “Verbal tic” head at the 12 o’clock position in the diagram. I have verbal tics which occur mostly when I am stressed and/or struggling to manage my intrusive thoughts. It feels like trying to tap alt-f4 with my brain or shake and etch-a-sketch. What I happen to mutter in the form of these tics goes through phases and for whatever reason, I had been muttering “Ok, welcome to the black parade” for a few weeks at the point when I decided to write a new story, and this become the image I began with, a character repeatedly muttering a statement about a My Chemical Romance song (which I must admit, at the time, I hadn’t even knowingly heard, i just knew the name).

My point is, that Verbal tic head could itself have expanded with multiple growths outward which followed the trains of why I came to be muttering that, how I had come into contact with the phrase, how I had experience in my practice of taking an arbitrary starting point to jump start a work, how I like the Becketian aspect of my tics which make language alien, how I like the repetition, how they connect in both directions of causality to anxiety (they are caused by stress, but they also draw attention to me) and so on and so on.

In closing, I think SBMM is a fantastic system, and its refreshing to try someone else’s system of diagrammatics, rather than my own which is utterly organic and chaotic (see pink diagrams, and the monkey-goth drawing at the end of this post which I drew to write the “ok, welcome to the black parade” narrative from). I’m currently prepping material to write the section of my thesis which is about diagrams, and Dean’s system is going to be in there, especially as it serves a very good bridge between the chaotic-code-switch which i employ for practice and the much more structure systems I use for written research such as the Digestion System.

#art#dean kenning#deleuze#diagrams#phd#research#drawing#science fiction#animals#horror#art research#art practice#uma breakdown

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Iroh & Zuko: A study in change and healing.

Uncle Iron and Zuko’s relationship is one I find truly interesting. It shows an interesting look into how people can change, how people can help others, the nature of wisdom and addresses healthy relationships that can survive toxicity.

So first change, this is obviously Zuko’s main character arch change and redemption, that’s been talked about ad nauseam, but Iroh also changed beforehand. We can infer he had a period of time that changed him the same way Zuko did over the course of the show.

Iroh isn’t a magically better person, but one of the main reasons he can be a good force in Zuko’s life is his past change. Iroh always had a tendency towards knowledge and mastered the more spiritual part of Firebending. He also seemed to be more comfortable playing Pai Sho and tea than being a leader. I think his quest for knowledge and lack of political ambition allowed for the death of his son to be a moment that pushed him to end his military campaign and not challenges Ozai’s power grab. We also know somewhere around this time he joined the Order of The White Lotus connecting him to a force trying to bring back balance. Had he not dealt with the reckoning of the destruction of his own family and past, as well as work through tragedy he would not have been able to as effectively help Zuko. He understood the pain and trauma but he had learned acceptance. He was of course not perfect but having known the hate and found the peace he wasn’t leading Zuko blind. This means that not only can Ioh mentor him from a place of age, be fatherly after having lost his own child, but more than most people also have an inherent connection to the struggle being had.

Iroh’s important role within the show is as a sage and mentor to primarily Zuko but others as well. Iroh is calm, accepting, generally level headed and steadfast in his beliefs allowing him to be a guidepost and foil to Zuko’s own erraticism. He loves Zuko deeply and wants nothing more than for him to be able to heal and choose his own path but does challenge him as time goes on knowing if Zuko just lives in pain he can never move forward.

He gives education about the cultures, people and bending of the people they see. He tries to give Zuko the power to work through his own issues. This act is crucial even though Iroh knows Zuko can be a danger to himself and others he doesn’t try and totally strip his autonomy or leave him unable to defend himself. I think this is evident with Zhao in the first book and then the Zuko alone arc in book two. Allowing Zuko to fight for himself when possible, and fail when he has to allows learning and gives real power. This is reinforced when multiple times he tells Zuko that in the end he has to choose what he wants, chose his own destiny and honour. If he wanted Zuko to make good choices reinforcing the life of little choice they came from would have done more damage.

Iroh doesn’t leave him without backup ever either. He’s always there for Zuko either physically having his back in battle, talking to him or even trying to help their crew understand where Zuko is coming from. No one has really had his back since his mother left, and it’s debatable how much she was even capable of doing. Trying to help him understand he isn’t alone is so powerful. Someone just being there for you is one of the most healing things a person can have. And I think more than any of the actual lessons just giving unconditional love was one of the strongest legacies you can leave.

Iroh also modelled what he wanted Zuko to learn. Rather it is Firebending being able to take it with your head held up, letting down walls, enjoying the small things, or brewing the best tea. Iroh lived his ideas making it do as I say and as I do in almost all circumstances. This irked Zuko of course as it was periodically embarrassing for him but I think it was why everyone who met him respected him or at least liked him. Even when Iroh was a man of layers and did have a few secrets he wasn’t duplicitous. Being a model of what you want increases trust and can help it easier to actually learn new ways of being.

Iroh is an example of Wisdom and not just knowledge. I think this difference does matter. Iroh was, of course, a master Firebender knew much of history and culture and was at least a decent military man from the way others spoke of him, but his understanding of the intangible is what makes him powerful. He always knew to watch and learn, he invented multiple bending techniques because he let down the arrogance and took in other ideas. Being a member of the White Lotus he knew and respected the connection of all four elements. He was often a third party within the first book, during the siege of the north we see him chose not to fight really for or against the Fire Nation. He acts to protect the spirits, to keep the balance. He is not averse to using violence (even against his brother or niece) but has a respect for the life of all peoples. This kind of understanding and wisdom is more powerful than any spewing of facts. Because this plays into the level of acceptance he has, makes him a formidable foe and gives him an ability to convey complex ideas.

Trying to find your centre and accepting who you are is an act of connection to the world and yourself. He can help many people Toph, Aang and a street beggar can all listen and understand where he comes from. He can help Zuko through his metamorphosis moment because he understands the connection of identity, health and spirituality. When you can bring a whole connection to someone it will always be stronger then listing facts or platitudes.

Zuko and Iroh have a relationship that is a blur of found family and blood ties. He is Zuko's biological uncle but they don’t seem to have been exceedingly close when Zuko was very young but after Iroh returned from war become closer. In the world of ancestors, destiny and bloodlines their relationship matters, but their connection was born from love, time, care, compassion, struggling, loss, fighting, and forgiveness. Neither the story or Iroh force Zuko to forgive Ozai or Azula. Iroh recognizes that his brother was abusive and horrible to his children, and recognizes that Aula can’t be left in power. Zuko chooses how he confronts both of these people, disavowing his father, and facing his sister with Katara. Their relationship comes out of this history of abuse and toxicity but is forged forward because of how much they have grown to care for each other in their own right and how much they grow. Iroh is Zuko’s real father in any important way and Zuko is as much his son as Lu Ten ever was.

Real World Techniques:

Through writing a mentor to someone who is clearly dealing with mental illness (C-PTSD, BPD) real-world psychological and coping strategies end up being employed in a strong connection.

-Radical acceptance. I skill taught in the framework of Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT). Iroh has learned to accept his past, and the loss he has shown. Iroh works hard to drag Zuko out of obsessive behaviour by trying to get him to accept that past happens, you can not fix that. Iroh himself embodies this behaviour. He doesn’t force non-action though, the acceptance makes you better able to manage future stress and build better lives.

-Meditation A common skill suggested across mental health and general health practice. He tries to instruct Zuko in this ability as one that is key to being able to properly Firebend and to reach in and use innate human power. This concept also connects people to the spirit world built into the mythology of the world.

-taking responsibility w/out victim blaming. Iroh knows Zuko’s backstory built him into this damaged person, but Iroh doesn’t allow him to hurt others through this. Iroh works to teach him to respect his crew, let down boundaries of pride and learn a new way of working in life. But there is never a time Iroh blames Zuko for the abuse he faced. Ozai’s treatment was never Zuko’s fault. They create an ability to simultaneously own your shit but not stew in self-hate

-We also see the structure we often see in productive de-radicalization programs. Zuko is exposed to the people he was taught to hate, facing the humanity and real-world effects of hate usually begin to break through narratives. Iroh lets him into his own point of view that connects all life, he learns the practice of living within balance instead of the belief system jammed into his brain, doesn’t let Zuko uses his past as reason for his behaviour, and acts and expects Zuko to let the humanity of The Earth Kingdom colour his view. The dissidence from his childhood beliefs and the new ones he can’t integrate into his life. This is crucial to his being able to learn the history of the fire nation, even describing the earth kingdom people favourably before his complete transformation.

Learning to use empathy across whole peoples is powerful to deprogram people, he is expected to verbally and through actions show contrition. Zuko is eventually able to connect to this over his indoctrination. The ability to come with humility and not expect the other side to forgive you. Often framed as seeking forgiveness from the people he does not deserve it from. This behaviour can work in reality and seeing played on screen is part of why this arc resonates across the media.

-Iroh helps Zuko find and construct meaning. The loss of a belief system Zuko experiences through his trauma leaves him in horrible confusion. Iroh helps him connect to his past giving a new lens to view the world from. He can’t do so from the position he held before having that structure built for him.

-I mentioned previously Iroh providing Zuko with a degree of control. Long term child abuse often creates either extreme self-reliance or sometimes learned helplessness. Offering both the ability to protect and control his life combined with having his back can combat both of these. Along with the deeply obsessive thought patterns around the avatar.

I truly belive their relationship is hugley important. Two characters who fit simple archetypes at the start are allowed to bloom into deeply strong and complex real feeling characters. Iroh is shown to be powerful, respected, incredibly kind and wise. We can all learn from him, and be shown a powerful love. Zuko’s own arch ahs been seen as groundbreaking for years but without Zuko we wouldn’t have had a person to guide and reflect this. Adding layers to the world and understanding ourslves.

[Requested by nbj on AO3]

#fandom:#atla#avatar the last airbender#topic:#relationships#trauma and media#abuse and media#character:#zuko#uncle iroh#azula#fire lord ozai#ship:#iron & zuko#type:#txt#my post

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

ZS Mythos (2/3): Sections & Sessions

This article is part of a series about the Mythos (worldview-narrative) underlying the Zero State (ZS). Part 1 is about our highest concept, ideal, and level of organization, which we call The Array. Part 2 (below) explains the Sections & Sessions our core activity revolves around, and Part 3 covers the Twelve Foundation Stones that form the basis of our story.

There is a lot of information in this article. You may wish to bookmark it, and use it as reference material, regardless of whether you view the Zero State (ZS) as a game, or as a real-world activist network, or just take an interest in online subcultures.

1. What’s in a Game?

Some people choose to think of the Zero State (ZS) in terms of being a game, specifically an Alternate Reality Game, which is basically an immersive narrative which deliberately blurs the boundaries between reality and fiction. ZSers are definitely not obliged to think it as a game, that’s their choice; we don’t mind how people engage and do their part, as long as they engage and do their part.

Regardless of whether any given individual prefers to view ZS activity in terms of a game or not, there are three nested levels of such activity, like the rings of an onion or a tree. In this article I am going to refer to these three levels as an outermost game, and two levels of game-within-a-game within, which we might call metagames. Using the analogy of an egg, let’s refer to these three levels as the yolk, the white, and the shell, starting from the centre as follows (and yes, yes, I know you could count the ‘metagames’ as the two innermost or the two outermost levels, that’s up to you):

The yolk is obviously the innermost level of the game, where it manifests as a mysterious puzzle, which we call the “Glass Bead Game” (after the Hermann Hesse novel). If you want to know more about this level of the game, then I’m afraid you will have to play the outer levels first, to search for it. The one thing we can say here is that, at this level, playing the game and developing the game are very similar things, perhaps one and the same. At this level the game is pure strategy – pure logic completely abstracted from all personality and narrative.

The white is a kind of bridging or hidden layer, connecting the worlds of pure logic with our pragmatic activity out in the real world. This is the level of the Sessions, which will be explained in part 3, below. For now, let’s just say that this level most resembles an online Role Playing Game (RPG), where ZSers adopt roles (the Core ZSers already have assigned roles, and all others are free – even encouraged – to craft their own within the established framework of the ZS Mythos), and participate in storytelling sessions which connect those roles to developing plans for our actions in the real world. This is the level where the ZS Mythos is most vibrant and alive. To learn how to join the game at this middle level – even if you choose not to view it as a game at all (as many of us do not) – then please be sure to read this entire article!

The shell is the ZS–ARG, which is to say the outermost, and most public level of the game. At this level, all distinctions between reality and fiction, truth and media, are deliberately blurred beyond all recognition. That is not our choice, but the nature of the world now; We hold to our Principles and the respect for Truth that they insist upon, but we all must play the game as we find it.

At this level it really doesn’t matter in the slightest if you think it’s a game or not; all that matters is how effective an activist you are. If you are ineffective, if you are inactive, then we really don’t care what you think. Sure, we’ll care about your wellbeing as our Principles dictate, but you haven’t earned the right to tell us how to do anything. If you want to change that, then wake up, and get involved!

Core ZSers don’t always use their role names at this level – although they are encouraged to do so – and what anyone else wants to do is up to them. At this level, ZS is in the business of growing activist networks, and the extent to which you’re involved is the extent to which you can be active, or at the very least support those who are. Game and Mythos narratives infuse our activity at this level, but they are entirely secondary to the practical results of our actions, as a network, out in the real world.

2. What are the Sections?

ZS is divided into seven functional groups called the Sections. Four of those (S1-4) concern the proper functioning of a balanced society, while the Higher Sections (S5-7) act as our deepest organizational structure, collectively representing the core functions of a cybernetic organism. The three Higher Sections are not only used to organise our core game sessions, but also to inform their themes and narratives. We will discuss the nature and logistics of the Sessions in the next section, below, but here are the themes which Sections 5-7 bring to them:

SECTION 5 / VR & internal “world-building”

Wyrd, Zero State, Illusory realities, Info-ops, strategy games.

SECTION 6 / AI & perception

Fyrd, Social Futurism, search for redemption or final frontier.

SECTION 7 / OS/UX & metaprogramming

Ásentír, Array, Reality hacking, neo-Gnosticism, and Transcendence.

3. What are the Sessions?

So finally, now, let’s focus on the Sessions, which draw upon the structure of the three Higher Sections, and are the very essence of ‘the white’, the bridging structure of ZS��� three game levels. As mentioned above these are essentially Role Playing Game (RPG) sessions, although they serve a number of practical non-game purposes and do not need to be viewed as a game by participants. Remember: What matters is outcome.

In the Sessions, every participant plays a role, based on the idea of a traveller from the future who has a mission to alter details of the past (our present). The Sessions are based around the teams that ZS members operate in to achieve their mission goals. Session activity is split (in no obvious or consistent way, and deliberately so) between narrative to establish your characters and relationships, and actual planning to go out and do things in the real world which help ZS and give your team prestige.

You will have a full say in what those things are, as part of your team. Team members who reach a certain level of accomplishment are encouraged to branch out and run entire teams of their own. The entire thing hangs together around a “league table” – an important function of The Array as an organizational entity – of the most accomplished teams. The better the players are at playing, the faster and more effectively ZS grows.

Logistics

The Core Sessions are based on a network of six factions. There are two such factions per Higher Section, arranged in loose alliances, each of them representing one of what we call the six Metahouses. The Metahouses are organizations within ZS which go by the colourful names of The Foundation, Cloud Nine, ZODIAC, The Black Parade, The Beast, & Club 21. Mythos narrative associated with all of these groups will be covered by the final article in this series (which is about the so-called “Twelve Foundation Stones”).

Most Session logistics are now being worked out within Discord itself, among the people who choose to participate in them. Basically, you just need to stick your head in there, sniff around until you have some sense of which faction you fancy belonging to (there are chat and voice channels for each of the three Higher Sections, so it shouldn’t be too hard to find where you fit, and you can always change your mind or join multiple teams) – or want to pretend you belong to! – and from there small groups of ZSers can self-assemble and request to arrange Sessions at whatever time suits them as a group. Don’t worry, it will all make sense… you just have to start by doing. Get involved, and see where the narrative leads you! The best way to get a head-start on understanding that narrative is to read the third and final article in this series.

Dharma

For some time we have intended to develop a “Dharma” system, which is to say a way of keeping track of status and achievement within ZS. That system couldn’t exist before now (aside from a few credits which we will of course honour by reflecting them in the new system, going forward) because there was no functional context for it, but now it has an important place at the very heart of our community.

As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, among other things The Array is a kind of “league table” that keeps track of the most accomplished ZS teams, using Dharma as the points representing their achievements. The exact details of the Dharma system will be developed within Sessions, as part of the game via our Discord server, which you can find here: https://discord.gg/R4t7V8U

One particular aspect of the Dharma system to take note of is its capacity to measure who should be allowed to branch out with entire session-teams of their own, which represents a higher level of achievement and responsibility within ZS. Again, we will be discussing (and deciding, collectively) exactly how this works within the mechanics of Discord over the coming days, and that conversation will be held via the Discord server itself, so you need to join there if you want to be part of it.

Resources

Finally, let’s take a moment to talk about resources. This idea – of the need for resources – was pivotal within ZS at the beginning, and for very good reason: Without resources, you can do nothing. If your resources are low enough you don’t have a network (not one you have any reliable control over, anyway), you can’t protect yourself or your loved ones, and push come to shove, you can’t feed them either. Late Capitalism’s gross materialism may give one pause about attaching any value to material things (I must admit, I’m no fan of money or status-symbol-objects myself), but at the end of the day if you don’t have enough resources, it’s game over for you and yours.

That sadly, is the basic and uncomfortable reality of life. So, as a matter of sheer pragmatism and also in order to live up to our Principles (most notably our commitment to mutual aid), we must take the question of network resources very seriously indeed. If we don’t, then there is no network, simple as that. Game Over.

In short, at every level ZS must now demonstrate an ability to secure resources, and use them wisely for the benefit of the entire network. Yes, that raises many (many) questions, which we will work out together, but the bottom line is that either we do that, or we forego any notion of an effective mutual aid network whatsoever. It really is as simple as that, I’m afraid. So, going forward, please be prepared at every step to ask yourself one question: What Have You Done For ZS, Lately?

ZS Mythos (2/3): Sections & Sessions was originally published on transhumanity.net

#activism#Alternate Reality Game#AR Gaming#ARG#Dharma#Mechanics#Metafiction#Metagaming#Metahouses#Narrative#Networks#Sections & Sessions#Zero State#zs#ZS Sections#ZS Sessions#crosspost#transhuman#transhumanitynet#transhumanism#transhumanist#thetranshumanity

0 notes

Text

Circles of tragedy and How To Act

Clare Finburgh, Senior Lecturer in Drama and Theatre at the University of Kent, responds to How To Act.

A circle. Anthony Nicholl, the “successful theatre director in his fifties” invited in Graham Eatough’s How to Act to give an acting masterclass, asks members of the audience to remove their shoes, which he then places centre-stage to form a circle. Nicholl marks out the circular space in which his participant, the young female actor Promise, will do improvisation exercises based on her own past.

According to Friedrich Nietzsche The Birth of Tragedy (1872), tragedy pulls “a living wall … around itself to close itself off entirely from the real world and maintain its ideal ground and its poetic freedom”.

[1]

Since its ancient Greek origins, tragedy has demarcated itself clearly as an art form distinct from the lives of the audience members watching it, a feature that the circle in How to Act recreates. In this, and in other respects, How to Act returns to the vast scope of the Classics. At the same time, How to Act expands classical tragedy in order to speak eloquently both to theatre today, and to politics today.In a number of respects How to Act, like the “prize-winning tragedians of ancient Athens” to which Nicholl refers, foregrounds its own status as art. Like a classical tragedy, How to Act features a chorus. The chorus self-consciously draws attention to the fact that what the audience is watching, is a piece of theatre. In addition, according to the French cultural theorist Roland Barthes, the chorus constitutes the very definition of tragedy, since it draws attention to the tragic dimension of the play by remarking on it.

[2]

How to Act differs, though, in that the members of an ancient chorus tend to pass judgement on the proceedings in the play, whereas Eatough’s chorus involves clapping and movement, which are performed in the circle. But in the extent to which ancient plays themselves featured song and dance,

How to Act does inherit from classical tragedy.Predating Nietzsche by over two millennia, the first theorisation of tragedy in theatre was provided by Aristotle, whose Poetics stated that the central tenet of tragedy must be one single, unified, clearly defined plot – what Nicholl in How to Act describes as “Proposition – dilemma – response. The fundamental building blocks of drama.” The circular space in which a tragedy is performed becomes a kind of boxing ring, a scene of combat in which conflicts are battled out until their final dénouement. Within the circle, the two conflicting worlds of Nicholl and Promise – male and female, European and African, older and younger, coloniser and colonised – clash. However, the plot in How to Act is far from straightforward. Eatough introduces a play-within-a-play device, where Promise, following Nicholl’s instructions, enters the circle and conducts drama exercises in which she enacts scenes from her childhood in her native Nigeria. When Promise reveals that Nicholl, who had formerly travelled to Nigeria to conduct research for his theatre practice, had no doubt had a brief affair with her mother, it is not clear if she is enacting a fiction, or whether she has actually come in search of the man who might be the father she never knew. Like the French author Jean Genet’s The Maids (1947), where two maids play at being a maid and her mistress; or indeed the most famous play-within-a-play of all, The Mousetrap in Shakespeare’s Hamlet (1599?), levels and layers of fiction in How to Act become entangled, as it is never quite certain on whose behalf the doubled characters speak. Like Shakespeare before them, generations of playwrights have abandoned the unity of an Aristotelian tragic plot in favour of multiple interweaving narratives. Indeed, the mid-twentieth-century German playwright, director and theatre theorist Bertolt Brecht, to whom I come presently, argues that today’s world is far too complex to be encapsulated in a singular dramatic plot:

Petroleum resists the five-act form; today’s catastrophes do not progress in a straight line but in cyclical crises; the ‘heroes’ change with the different phases, are interchangeable, etc.; the graph of people’s actions is complicated by abortive actions; fate is no longer a single coherent power; rather there are fields of force which can be seen radiating in opposite directions.[3]

“The truth is that theatre is dying and we all know it”, declares Nicholl in How to Act.

Whereas Nietzsche entitled his major work The Birth of Tragedy, George Steiner in the twentieth century announced The Death of Tragedy (1961) – the name of his important study. Steiner argues, “tragic drama tells us that the spheres of reason, order, and justice are terribly limited and that no progress in our science or technical resources will enlarge their relevance”.

[4]

For Steiner and other Marxist theorists and theatre-makers, notably Brecht, the incontrovertible fate in tragedy is incompatible with a political commitment to the radical transformation of society: tragedy in art is anti-progressist because it reinforces political fatalism in life. It is important to note that Aritotle’s Poetics does not in actual fact mention fate, although ancient tragedies do often submit tragic heroes to their destiny. Sophocles’s Oedipus is the classic example: before his birth it was predicted that Oedipus would murder his father and marry his mother; and despite his and his parents’ lifelong efforts, this is precisely what takes place. The circle in Eatough’s How to Act thus denotes the inescapable circularity of fate.

The Algerian playwright Kateb Yacine, many of whose works were written during the Algerian War of Independence (1954-62), named his tetralogy of tragedies, which was inspired by Aeschylus’sThe Oresteia, the Circle of Reprisals (1950s). In this series of plays, as in Aeschylus’s House of Atreus in the Oresteia, a closed circuit of violence, an ancestral cult of violence, reprisals, revenge, fatality and failure, become inevitabilities for all of Algeria’s population. Kateb writes:

For me, tragedy is driven by a circular movement and does not open out or uncoil except at an unexpected point in the spiral, like a spring. […] But this apparently closed circularity that starts and ends nowhere, is the exact image of every universe, poetic or real. […] Tragedy is created precisely to show where there is no way out, how we fight and play against the rules and the principles of “what should happen”, against conventions and appearances.[5]

This resignation to a doctrine of circular fate is illustrated when Promise in How to Act says:

It’s all been written for us hasn’t it? Sometime in the past. Before we met anyway. Before you met my mother even. None of it could have been any other way. You thought you could make a difference. Control things. Control the story. But it’s not yours to tell. You’re just a part of it. Like we all are. You’re just in it. Subject to it. It’s all been decided. Who we are. What we mean to each other. How this turns out. I was always going to find you. Come back to you. Like a curse. Show you who you really are. A liar. That’s how this ends. There’s no escape.

It is precisely this belief in the circle of fate and the absence of a possibility for escape from this circle, that has been rejected by Marxist playwrights and directors like Brecht.

Instead of submitting to a destiny of suffering, for Brecht, characters – and the audience – must seek to understand the reasons for suffering, and to redress the social and economic injustices that cause that suffering. Marxist cultural theorist Walter Benjamin, Brecht’s contemporary, explains how Brecht’s politics distinguish between simplicity and transparency. Simplicity denotes the defeatist acceptance of misery and resists challenge to the status quo: “That’s just the way it’s always been”; transparency, on the other hand, rejects the mystifications that lead society to believe that suffering is universal and eternal. Erwin Piscator, a Marxist dramaturg who was also contemporary to Brecht, summarizes how tragedy is the result not simply of fate, but of political and socio-economic circumstances:

What are the forces of destiny in our own epoch? What does this generation recognize as the fate which it accepts at its peril, which it must conquer if it is to survive? Economics and politics are our fate, and the result of both is society, the social fabric. And only by taking these three factors into account, either by affirming them or by fighting against them, will we bring our lives into contact with the “historical” aspect of the twentieth century.[6]

In How to Act, the causes of suffering on the African continent, notably in Nigeria, are given clear explanations by Promise. As Brecht highlights in the quotation to which I have already referred, “petroleum” is one of today’s most pressing and complex problems. Promise explains how, in spite of Nigeria’s vast oil wealth, it has been crippled by “debt to western governments and the World Bank.” In addition, she describes how “western oil companies” such as “Shell, Exon, Chevron and Total” have not only made many billions of dollars of profits out of Nigerian oil and gas and massively expanded the west’s consumption of energy and goods while their employees live on “less than a dollar a day”. In addition, these oil companies have committed human rights abuses by encouraging the Nigerian government to execute activists campaigning for social and environmental justice. These perspectives provided by the play engage directly with current geopolitics, since in June 2017 the widows of four of the nine activists extrajudicially executed in 1995 by the Nigerian government for campaigning against environmental damage caused by oil extraction in the Ogoni region of Nigeria, launched a civil case against Shell, accusing them of being complicit in the torture and killings of their husbands.[7] While inheriting from classical tragedy, How to Act conducts, in parallel, a typically Marxist analysis that seeks out the causes for suffering, rather than submitting to them. “[Y]our having everything depends on us having nothing.”, admonishes Promise.

In Theatre & Ethics, Nicholas Ridout defines ethics by posing the question, ‘Can we create a system according to which we will all know how to act?’

[8]

By admitting to the reasons for social, economic, gender and environmental injustices, we can strive towards an ethics of “how to act”, as the title of Eatough’s play suggests.

In some respects How to Act could be described as a postcolonial play, or at least a play that examines and exposes the afterburns of British colonial occupation in Nigeria. The Nigerian playwright and Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka, rather than dismissing tragedy outright, argues for the “socio-political question of the viability of a tragic view in a contemporary world”. For him, as he demonstrates in some of his great tragedies, notably Death and the King’s Horseman (1975), the theosophical school which would accept suffering and death as the natural order of things, and the Marxist school which insists that the historical reasons for human suffering must be explored, understood, and rectified, can indeed be encapsulated in the same play (1976: 48). Graham Eatough demonstrates, as Kateb Yacine and Wole Soyinka have done before him, and as authors such as the Lebanese-born Quebecan playwright and director Wajdi Mouawad continue to do today, that tragedy is an enduring form that can not only affirm the inevitability of suffering and injustice, but can also candidly expose the reversible reasons for that suffering. There are economic, social and political reasons for tragic suffering which must be comprehended and apprehended, in order to effect change. These artists replace circles with spirals, and spirals have an end.

[1] Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy, trans. Shaun Whiteside, London: Penguin, 1993, 37-8.

[2] Roland Barthes, “Pouvoirs de la tragédie antique” [1953], in Ecrits sur le théâtre, Paris: Seuil, 2002, p. 44.

[3] Bertolt Brecht, Brecht on Theatre, trans. John Willett, London: Methuen, 2001, p. 30.

[4] Steiner, George. The Death of Tragedy. London: Faber & Faber, 1961, p. 88.

[5] Kateb Yacine, “Brecht, le théâtre vietnamien : 1958”, Le Poète comme un boxeur : Entretiens 1958-1989, Paris: Seuil, 1994, p. 158, my translation.

[6] Erwin Piscator, The Political Theatre [1929], trans. Hugh Rorrison, London: Methuen, 1980, p. 188.

[7] Rebecca Ratcliffe, Ogoni widows file civil writ accusing Shell of complicity in Nigeria killings, The Guardian, 29 June 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2017/jun/29/ogoni-widows-file-civil-writ-accusing-shell-of-complicity-in-nigeria-killings.

[8] Nicholas Ridout, Theatre & Ethics, Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2009, p. 12.

HOW TO ACT Written and directed by Graham Eatough.

Internationally-renowned theatre director Anthony Nicholl has travelled the globe on a life-long quest to discover the true essence of theatre. Today he gives a masterclass. Promise, an aspiring actress, has been hand-picked to participate. What unfolds between them forces Nicholl to question all of his assumptions about his life and art.

https://www.nationaltheatrescotland.com/content/default.asp?page=home_How%20To%20Act

0 notes