#also it co-existed with SO many pterosaurs

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

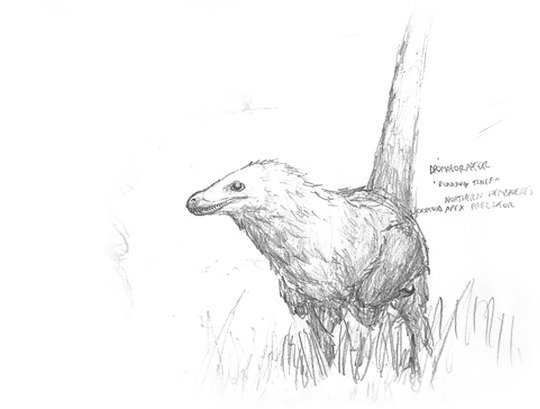

it's your grandma! it's juramaia!

(aka, that shrew-like thing that is the earliest known fossil ancestor to placental mammals)

#also it co-existed with SO many pterosaurs#u gotta forgive it for its frightened expression#juramaia sinensis#Jurassic#palaeoart#palaeoblr#paleontology#my art

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Multituberculate Earth: Birds

(As with all animal pages so far, this only goes so far into the Oligocene… for now)

At first, the avifauna of this timeline evolved much as ours. Only the toothless crown birds survived the KT event (though outliers like Qinornis may indicate other lineages survived briefly; one study did note the similarities between pelagornithids and ichthyornithids, but it hasn’t made the plunge), several lineages quickly producing megafauna to replace non-avian dinosaurs and other great reptiles. Gastornithiforms and ratites occupied large herbivore niches on land, pelagornithids and lithornithids attained large wingspans as competing pterosaurs ceased to exist and giant penguins and plotopterids were the first vertebrates to occupy large predatory niches at sea (barring sharks of course). To say nothing of the massive variety of smaller birds like stem-tropicbirds, the passerine-like zygodactylids and carnivorous parrots.

But the absence of an Azolla Event put avian evolution in a very different track from the Eocene onwards. For starters, without a mid-Eocene cooling to alter forest biomes, lithornithids and presbyornithids didn’t decline, thus preventing an opening for several lineages like cranes, storks and pelecaniforms. Many groups that depended on the cooling temperatures, like seagulls and relatives, also did not get the opening they wished for. Some modern groups you might assume quintessential, like ducks and shorebirds, were either greatly crippled or did not get to rise.

Likewise, the evolution of flying mammals put some pressures on birds that our bats didn’t have, but for the most part both groups managed to co-exist. Niche partitioning is easy when you can fly anywhere to get resources, after all, and birds are no strangers to it given how they co-existed with pterosaurs and other Mesozoic flyers for over one hundred million years.

By far the greatest challenge faced by birds thus far was the Grand Coupure, leading to a dramatic collapse of forest habitats. For European and Balkanatolian flightless birds it was particularly hard as their isolation in Europe came to a drastic end, but several flightless lineages remained in the Oligocene.

Because there are lots of Cenozoic bird groups, some more understood than others, this is something of a work in progress. However, I will list the bird groups that I have most assuredly set in stone.

Palaeognaths

The so called “old jaws” might be something of a misnomer, as some Cretaceous birds already had a neognath palate and their own palate is much more advanced than in some other early birds, but regardless they do invoke that prehistoric mystique. In our timeline the sole survivors are the flightless ratites + tiny tinamous, animals that truly seem to come from the era of the dinosaurs.

In this timeline, ratites similarly diversified, with rheas and other poorly understood taxa in South America and Antarctica, members of the cassowary/emu line in Australia, elephant birds in Madagascar (and possibly mainland Afro-Arabia) and a variety of stem-ostriches in North America, Europe and Asia. But it is another group, the flying lithornithids, that remain the most diverse and arguably spectacular group.

In our timeline, lithornithids started the Cenozoic in style, dispersing across the northern continents as forest dwelling probers like modern woodcocks. They were far more efficient flyers than our timeline’s surviving flying paleognaths, the tinamous, there being evidence of migratory behaviour and stork-like soaring, and some species attained quite large sizes. In our timeline the mid-Eocene cooling seems to have doomed them, but in the prolonged hothouse conditions of this timeline they managed to acclimate and diversify further.

Some lineages were lost in the Grand Coupure, but those that survived were ready for the spread of open habitats. Many forms occupy niches taken in our world by cranes and storks, prowling the steppes or stalking the swamps for small animals and nutrious plant matter. Others have diversified as shorebird analogues, probing along the coastlines. Some conversely became smaller and hoopoe-like; lithornithids were already more efficient perchers than other palaeognaths, so a few managed to capitalize on arboreal niches.

Though efficient flyers, lithornithids lack tails, relying mostly on their own wings for steering (for reference, see videos on tailless kites or hawks). Like in their ratite cousins it is the male that protects the eggs and offpsring, though in some derived species the young are superprecocial and can fly soon after birth, a condition seen in many Mesozoic birds. Many species have glossy eggs and feathers like cassowaries.

Other than lithornithids, there seems to be some other flying palaeognaths about. The stem-ostrich Eogrus for example is traditionally considered capable of at least some flying abilities, while flying stem-kiwis must be around somewhere given Proapteryx. And, of course, there’s the ancestors of tinamous, which have not yet debuted in the fossil reccord for some reason (in both timelines).

Pelagornithids

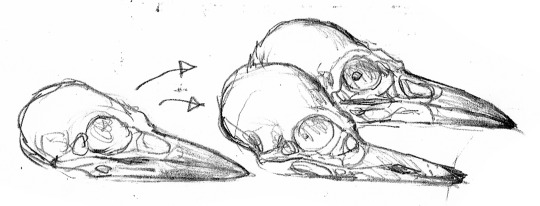

The so called “pseudo-toothed” birds due to tooth-like serrations in their bills, these seabirds are a mystery. Sometimes they are grouped among albatrosses and other higher waterbirds, other times they’re considered closely related to waterfowl, with most recent studies putting them in a polytomy between both groups. As mentioned above there is a study that does note similarities between their jaws and those of aquatic toothed seabirds, and given that their serrations seem to share a true molecular origin with teeth I wouldn’t be surprised if they were surviving toothed seabirds all along.

Anyways, besides the “teeth” (which were acquired late in life, implying prolonged parental care) the most notable feature of pelagornithids is their size. These are easily the largest flying birds of all time, some reaching wingspans of over 7 meters. Because they lack the quadrupedal launching of flying mammals and pterosaurs, they compensated by become extremely lightweight like living kites, thus while they look fearsome they most hunt small, soft prey like squids. Its even possible they can’t flap their wings anymore, relying solely on thermal soaring like modern frigatebirds (and not dynamic soaring like albatrosses), to which they can be considered close analogues if much larger.

While the evolution of giant insulonycteriids might seem like a disaster for these enormous birds, in truth both groups get along just fine (most of the time). The giant flying mammals are most robust and can hunt proportionally larger prey and even dive, so if the pelagornithids are the frigatebirds the insulonycteriids are the albatrosses and gannets.

Pelagornithids in both timelines have been extrariordinarily resilient, surviving from the PETM and Grand Coupure in spite of their effects to the marine biosphere. They died out in our timeline just as humans evolved, for unclear reasons; we’ll see if they have better luck here.

Gastornithiformes

Like ratites gastornithiforms lost the ability to fly and attained large sizes, occupying the niches left by ceratopsians and other herbivorous dinosaurs. They are clearly galloanseres, though its currently debated if they are closer to waterfowl or to galliforms.

Like ratites, they attained a cosmopolitan distribution, with gastornithids in the northern continents, dromornithids in Australia and Brontornis in South America, though gastornithids disappeared from Asia and North America in the PETM. Unlike ratites they have massive, powerful beaks, apt to crush through seeds and harsh plant matter like branches. In Europe they in fact were the most common megafauna, with few large mammals, much like in our timeline. With the Grand Coupure the collapse of rainforests and the arrival of Asian predatory mammals they disappeared from the former island continent, but they continued to thrive in Australia and in South America.

Presbyornithids

Presbyornithids are a clade of long legged waterfowl that first evolved in the Cretaceous and attained a diversity peak during the Paleocene, before declining in the Eocene of our timeline, reduced to only the terrestrial, goose-like Wilaru by the Miocene. This is often attributed to competition with anatid waterfowl, but studies show that they were incapable of filter-feeding, so they must have occupied fairly different ecological niches at the water’s edge.

In this timeline, they kept thriving thanks to the continuous hotshouse conditions, and more overtly diversified in piscivorous and crustacean eater niches akin to those of shoebills, spoonbills and even pelicans and ibises. Consequently, many of these waterbirds did not evolve in this timeline.

A partiular clade related to Wilaru kept exploring terrestrial biomes. These developed a novel way to process food: chewing it. Yes, some birds can chew (even used in the past to explain phylogenetic relationships between cuckoos and mousebirds before genetics said nah), using the cranial kinesis common to all crown birds to slide the upper jaw against the lower jaw in a pestle and mortar like way.

These birds, the Chakranatids, found thus a way to not only process plant matter more efficient while minimising fermentation, so they for the most part retained the ability to fly. Still, some have become large flightless herbivores, a distant echo of the Mesozoic hadrosaurs.

Palaelodids

The niche of ducks was instead taken by a decidedly non-waterfowl clade: the palaeolodids, relatives to flamingos and grebes. Neither divers or specialised filter-feeders (barring some species), these birds are rather generalistic, adapted to swim and catch small animals and plants with their broad beaks. They first debuted in the Oligocene in both timelines, though they might have a potentially older origin given grebes and flamingos split further back in the Cenozoic and Eocene fossil birds like Juncitarsus seem to represent the last common ancestor between these three groups.

Coliiformes

(A suggestion by Tozarkt777 on reddit)

In our timeline’s Paleocene, before passerines had evolved and spread to the northern hemisphere, the songbird niche was held by the Coliformes, an order that now only includes the mousebirds in our timeline, but back then comprised of many more species and many more niches, from generalistic grain-feeders to raptorial forms. They were most diverse in the Paleocene and Eocene before losing ground from there onwards.

Their decline likely is attributed to the PETM, and with the warm conditions of Multituberculate Earth having been maintained, so did mousebird rule. These are now the dominant small birds in the northern and African canopies, passerines now mostly restricted to small insectivores and nectivores.

Cariamiformes

Represented by the vicious little seriemas in our timeline’s present, this group is best known for producing the infamous terror birds. However, a variety of other extinct groups also existed in the early Cenozoic, including another clade of infamous flightless killers, the bathornithids. Though known from usually more fragmentary remains, they too were incapable of flying and had deep, powerful beaks, well suited to tear flesh.

Proving that mammals still oughta fear theropods, the terror birds spread far and wide in the Eocene. Eleutherornis and relatives terrorised Europe while Lavocatavis and kin terrorised Africa; it is in fact unclear if terror birds evolved in the Old World and later raft/swam (or flew, if the last common ancestor still could fly) to South America like many mammals did or if inversely it went the other way around. We do know at least that Eleutherornis is a late comer to Europe as it arrived only in the mid-Eocene, so the group likely didn’t evolve there, though many other cariamiform groups were present, from the crow-like Salmila to the herbivorous, also flightless Strigogyps.

Meanwhile, South America was host to a larger diversity of terror birds, and across the sea North America was ruled by a large diversity of bathornithids. Both groups co-existed with predatory mammals in both timelines, and attained large sized species over two meters tall. The African and European species seem to have gone extinct in the Grand Coupure – the later doubtlessly affected by the extinction of indigenous prey and the arrival of new competitors – but the Americas saw an adaptive radiation in response to the spread of open grasslands. Predatory mammal groups may rise and fall, but these dinosaurs seem to be a constant, though for how long remains to be seen.

Besides large predatory forms, there are a variety of other poorly understood forms, like the aforementioned European species. Some, like Elaphrocnemus, appear to have been efficient flyers, less adapted to run like their terrestrial cousins but capable of soaring for long distances. while others like Qianshanornis seem to have been functionally similar to hawks and eagles. Most of these groups died out in the Grand Coupure, unable to cope with the loss of forest habitats.

#multituberculate earth#speculative zoology#spec evo#speculative biology#speculative evolution#bird#birds#dinosaur#dinosaurs#bathornis#lithornis#presbyornis

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the smaller elements in the background of my Avatar-verses

And one that has its most direct impacts on and relevance to the plot in the various areas where the spirit world and material world overlap and merge and neither is entirely better off for it, is that the combination of the Vaatu-Raava rivalry and the Avatar's severing of the lines between the worlds is why so many hybrid animals and the like exist and why the original pre-hybridization animals either went extinct or to fringe corners of the world. In short the hybrid creatures are not 'natural' products of alternative evolution, it's a gigantic combination of the Annihilation/Colour Out of Space scenario.

At the same token one of the few creatures to be primarily unaffected by it in one way and very affected in another are the old komodo-rhino lizards. They don't merely resemble ceratopsians, they ARE Avatar-verse dinosaurs, the only non-avian dinosaurs to survive the equivalent of the KT boundary and to adjust just fine to the new mammalian era, helped by most of the predators that ate them going extinct and the only ones that remained, the dragons of the ATLA equivalent of the Cenozoic, developing sapience and opting for more complex approaches to life.

Dragons are descendants of Pterosaurs in this AU, not dinosaurs. Birds and komodo-rhinos are the only actual extant dinosaurs in the ATLA-verse.

Likewise as far as human evolution there are analogues to the Yeren/Orang Pendek/Yeti, though these creatures are even more Uncanny Valley than great apes, and portrayed as rather more intelligent than most takes on the Bigfoot/Sasquatch element. These creatures are *also* survivals of the AU's equivalent of Robust Australopiths who developed gigantism as both the conclusion of most evolutionary lineages over time and as a kind of self-protection mechanism against their hairless cousins.

They tend to co-exist somewhat uneasily with the four-legged apes and have a very nasty violent streak. You could even say their temperament is....abominable.

#atla aus#evolution and the atla world#there are cryptids in the ATLA-verse#they're either livestock or the friendly neighborhood sea serpent#minus the Yeren who are outside genre experience horror stories

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A World of Dinosauroids

C. M. Kosemen with Simon Roy

My post on Simon Roy’s “Dinosauroids” is one of the most reblogged things on this blog. I love the concept because it rewrites the cosmic tragedy of the K-T Mass Extinction Event, resurrecting dinosaurs and projecting their continued evolution in ancient world that is alien but also eerily resonant. Recently Simon turned me onto The-Master-Post-on-All-Things-Dinosauroid on his long-time collaborator, C. M. Kosemen’s, site. The following post has been transcribed from C. M. Kosemen’s blog and formatted for Tumblr with @simon-roy‘s blessing.

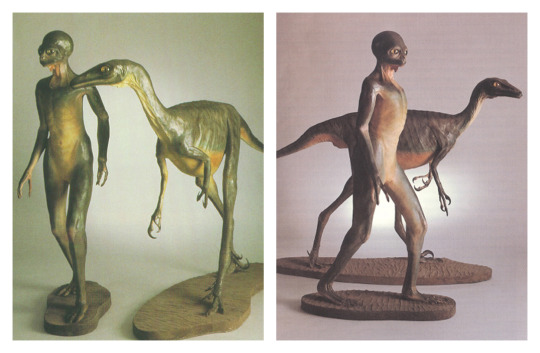

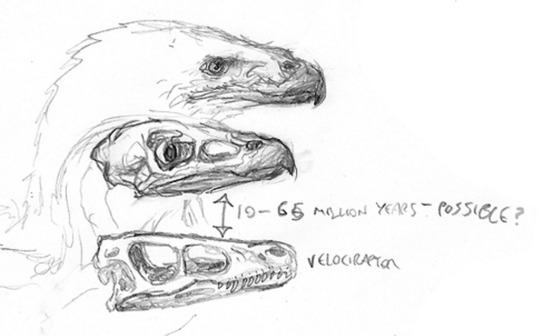

There are two highly-popular, vexing questions about dinosaurs: What would the world look like if these strange and majestic animals had not gone extinct? And, would they ever evolve into intelligent species comparable to humans? In 1982, palaeontologist Dale Russell, after observing “… a general trend toward larger relative brain size in terrestrial vertebrates through geologic time, and the energetic efficiency of an upright posture in slow-moving, bipedal animals”, postulated the Dinosauroid, a humanoid, erect-gaited sophont which may have evolved from Troodon-like dinosaurs had the end-Cretaceous extinction not occurred.

This question occupied the minds of yours truly (seen here on the right), and world-building comic genius Simon Roy (on the left), as well. We were unconvinced by Russell’s Dinosauroid. We thought that an erect, humanoid sophont was too prejudiced towards humans to be realistic. We were instead inspired by zoologist Darren Naish’s writings on the evolution of intelligent, bird-like dinosaurs: “No, post-Cretaceous maniraptorans wouldn’t end up looking like scaly tridactyl plantigrade humanoids with erect tailless bodies. They would be decked out with feathers and brightly coloured skin ornaments; have nice normal horizontal bodies and digitigrade feet; long, hard, powerful jaws; stride around on the savannah kicking the shit out of little mammals; and in the evenings they would stand together in the trees, booming out a duet of du du du-du, a deep noise that would reverberate for miles around…”

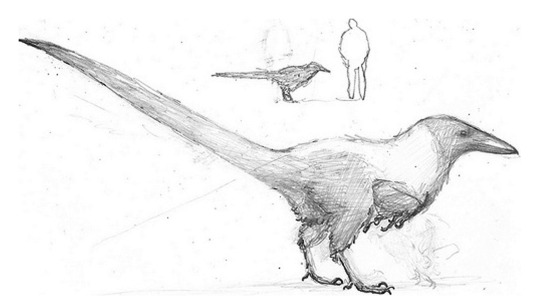

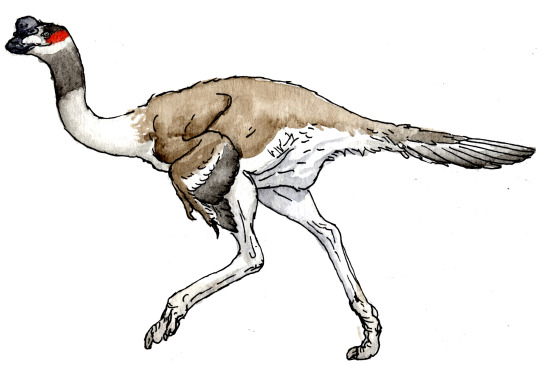

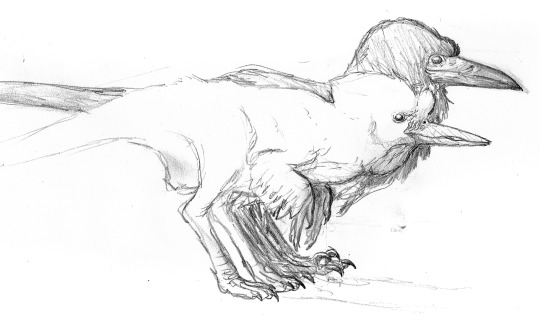

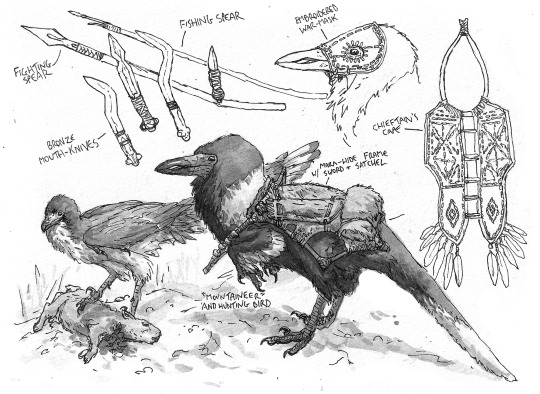

Towards the end of the ‘00s, Simon Roy and I independently began to develop our concepts for bird-like intelligent dinosaurs. Inspired by the ravens he saw around his Canadian home, Simon drew the corvid-like dinosauroids seen above.

I, in turn, was inspired by ground hornbills, parrots, certain dinosaurs and corvids, and came up with the speculative organism seen above. I named it Avisapiens saurotheos. Simon and I soon got in touch with each other; and started developing a world and a storyline for our dinosauroids. Our collaborative efforts continued, on-and-off, until the mid-2010s. Our aim was to develop the Dinosauroids story into an illustrated story-book, which we naively hoped to sell to a major sci-fi publisher. But we soon realised that we enjoyed world-building more than writing a story, or putting a book together. We kept bouncing concepts back and forth, but never had a chance to publish them, until now. Most of the body of work you see on this page was drawn by Simon, based on ideas we created together. I also contributed some of the “cave drawings” and certain creature illustrations. This is the first time the totality of our Dinosauroids-universe works has been displayed online.

Simon and I refined the design of my original Avisapiens dinosauroid…

And created a few more sentient races to accompany them. There was one more, slightly-crow-like species of Avisapiens (a continuation of Simon’s corvid dinosauroids - Avisapiens tataricus). These two species were joined by a variety of “forest giants” (Gigantosapiens borealis), and a race of pygmies (Avisapiens minimus).

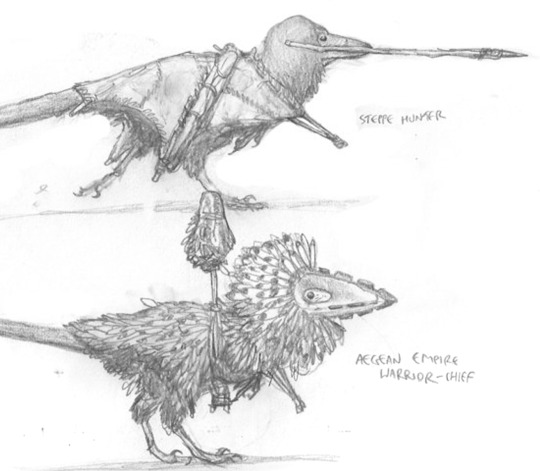

Simon’s refined studies of corvid-like, and pygmy dinosauroids.

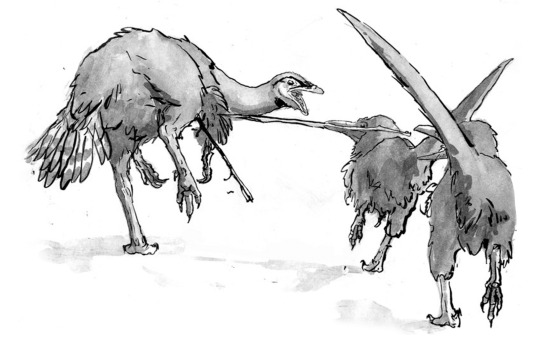

We also designed an extensive selection of animals around our dinosauroids. We predicted that even without the K/T mass extinction, dinosaurs and other animals would have kept on evolving, and many “familiar” groups of dinosaurs would have gone extinct. We thus designed a world where the majority of surviving dinosaurs were the descendants of “maniraptoran” groups; birds, deinonychosaur (“raptor”) dinosaurs, troodonts, oviraptors and therizinosaurs. Here, you can see two boreal dinosauroids using mouth-spears to hunt herbivorous troodont quarry.

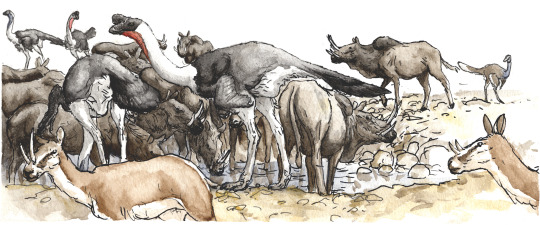

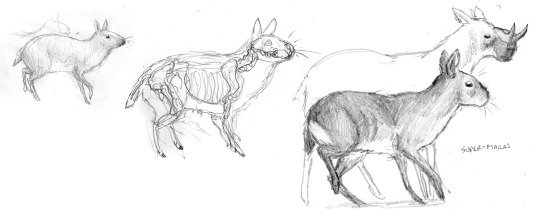

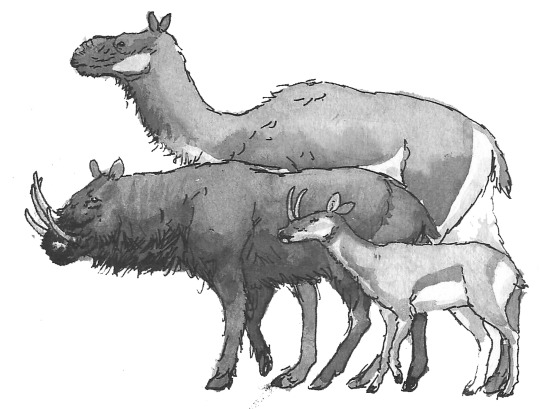

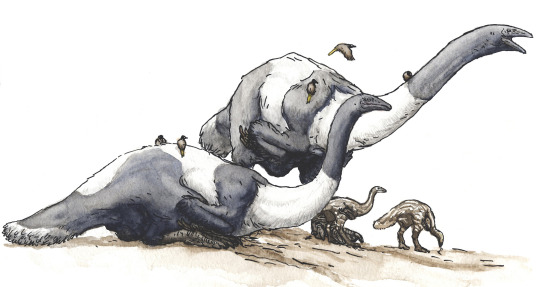

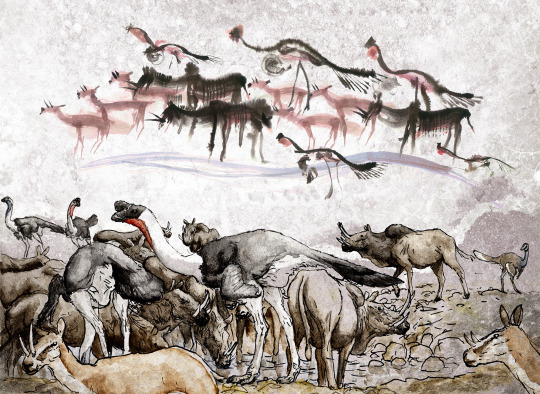

We also did not want this world to be devoid of mammals. Even during the age of dinosaurs, certain mammals evolved into large and sophisticated forms. We envisioned a world where parallel groups of mammals, similar to, but phylogenetically distinct from today’s forms, co-evolved alongside the dinosaurs during their continued reign. The scene above shows an Eurasian water-hole crowded with two species of ornithomimid herbivores (Rugocursor, left-centre; and Cyanogularia, far right); alongside robust (Afrotuberculocamelus) and gracile (Odontocervoides) species of herbivorous mammals which, for the lack of a better term, we decided to name “supermaras”.

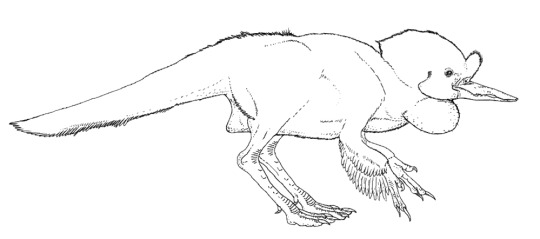

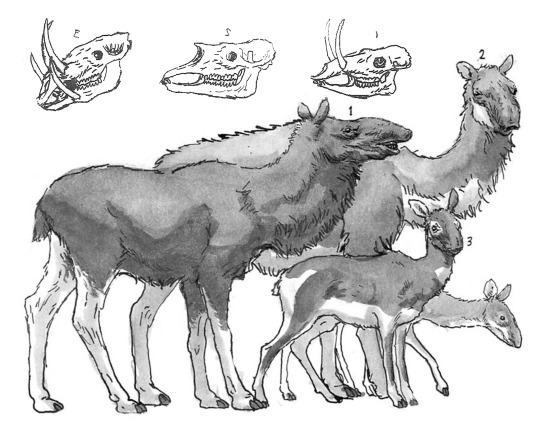

A series of studies showing the evolution of supermaras from rodent-like multituberculate mammals. The species depicted here is Ceratomegamys.

The full diversity of cursorial “supermaras”, from left to right: The burly, tusked Odontobovis; the superficially-camel-like Tuberculocamelus; the gazelle-like Odontocervoides; the trunked, moose-like Pseudalces; and the two related forms - the big, desert-dwelling Macropseudalces; and one of the many deer-like Cervopseudalces species.

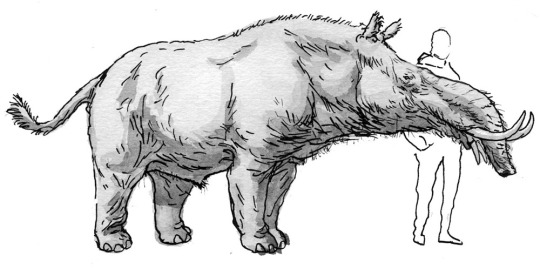

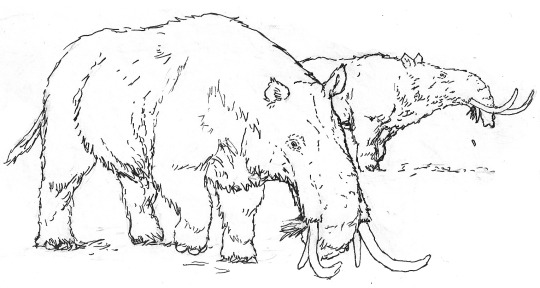

Studies of Megatapirus, large, superficially-elephant-like mammals that live in far-northern climates.

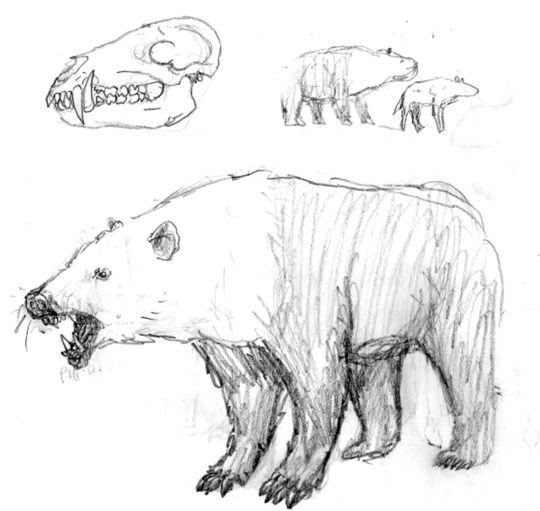

We also derived a variety of mammalian carnivores, mostly from marsupial stock. Through the honing forces of evolution, we imagined some would look very similar to the canid predators we have in the present day - the actual difference would only be in their internal and reproductive anatomies. Above, clockwise: The large, badger-like Mephitursoides; the extremely dog-like Pseudokynos; the hyena-like Krokutadasyurus.

Some marsupial predators diverged from the mammalian body-plan, and evolved into forms roughly converging with the predatory dinosaurs. The raptorial, meat-eating kangaroo-equivalent Theropodoktonos and kin are potent predators in South America.

Two more divergent marsupials: The leopard/possum Phobodidelphyoides; and the monkey-like Marsupiolemuris, a social, arboreal form with a potential to evolve intelligence.

We also wanted to have flying reptiles - pterosaurs - still alive and kicking in our world. These extraordinary animals were already in decline by the time dinosaurs became extinct. So we relegated them to only a few roles, comparable to storks and other large water-birds alive today. Above is a flock of Diluvipterus; large, filter-feeding pterosaurs. Also note the solitary duck flying on the upper-left corner.

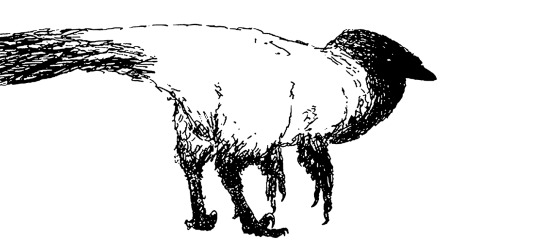

Another, flightless pterosaur, Cygnotherium, from the islands that now make up New Zealand.

A more unusual group are the avisuchians, descendants of maniraptoran dinosaurs that secondarily converged on the aquatic bodyplans of spinosaurs (which are now extinct in this timeline). Most resembled the short-tailed forms, Pisciraptor and Brachyornithoides seen above. These goose-to-dog-sized animals inhabit rivers and lakes, and occupied a niche comparable to otters today.

There were also long-tailed Avisuchians such as the Natatoraptor seen above. These animals inhabit open waters, and nested in estuaries and beaches.

A contemporary scene from Eurasia shows commensal life between mammals and dinosaurs. Two Pseudalces browse peacefully alongside two kinds of large ornithominids, Archganseria and Brontonyx. A tiny, heron-like troodont, Anatolocursor, can be seen between them, looking for small animals flushed out by the large herbivores’ movements.

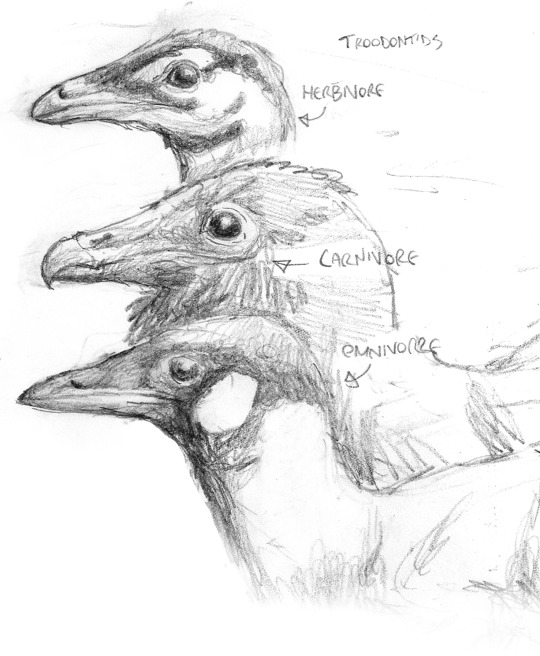

Nevertheless, despite co-existing with large mammals, dinosaurs are more diverse on this world. Herbivorous dinosaurs, such as these derived ornithomimids, constitute a large part of dinosaurian diversity. Above left are studies of Ganseria, a common, medium-sized browser. Above right, clockwise from the top right, are portraits of Ukkuloganser, another medium-sized browser; Nyctodromon, a nocturnal digger; Adzuganser, a small omnivore; and Pyramidoganser, a crested form native to the Nile Delta.

A scaled study of Brontonyx, a heavyweight ornithomimid herbivore.

Portraits of many cursorial dinosaurs from across Eurasia: 1- Leptoganseria, a mountain-dwelling ornithomimid browser found on the mountains of what is now the Caucaus. 2- Ikiridectes, a troodont that mostly hunts small digging mammals. 3- Aktardektes, a small ornithomimid that has specialised for cracking hard-shelled nuts. 4- The gracile, juvenile variant of Brontonyx, (6) which occupies a completely-different ecological niche as a generalist omnivore. 5- Rugocursor, a widespread, broad-beaked ornithomimid with many species, common across North Africa and Eurasia. 6- The adult form of Brontonyx, a gigantic ornithomimid that feeds on trees, and defends itself with heavy claws. 7- A vulture-like Cynornithoides, an extremely bird-like troodont, a frequent commensal of Avisapiens and related intelligent species.

A variety of Rugocursor, a mostly-herbivorous ornithomimid with adaptations for running.

Various troodonts, small-bodied, sometimes very bird-like omnivorous dinosaurs, distantly related to the Avisapiens lineage. Left, shaded study of Variocursor, a common, heron-sized, striding predator on small animals. Right, from top to bottom; Vuuria, a herbivorous form common across Eurasia; Boreocursor, a cold-climate predator, related to the Variocursor seen on the left; and Paravuuria, an omnivorous form.

The last descendants of hadrosaurs, the famous “duck-billed dinosaurs”, still roam in South America. The hoofed, sheep-sized Ornimastax seen above left, is a typical example. Australia, as in our world, is home to an unusual radiation of forms whose relations to animals on other continents are not very clear. Brachygullagong, seen above right, is a troodont-like form whose duck-like skull and batteries of grinding cheek teeth have secondarily converged with those of the hadrosaurs.

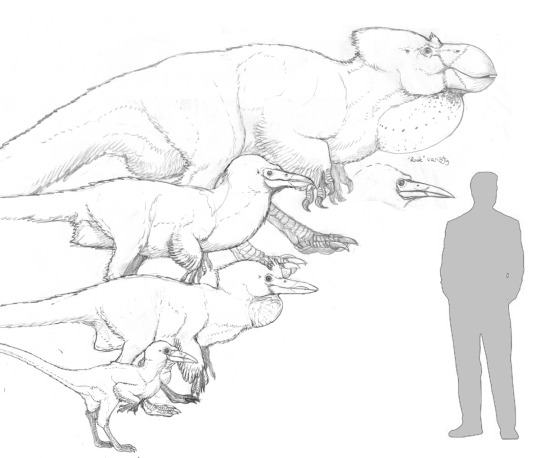

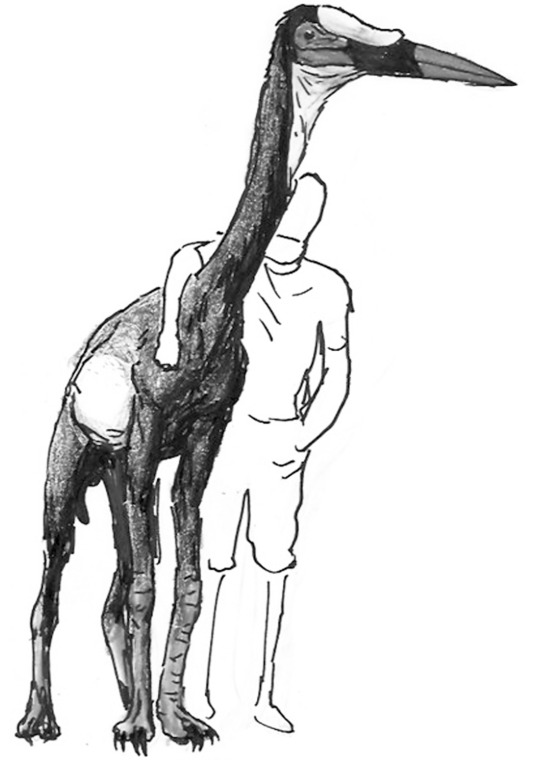

The largest herbivores on this world are long-necked, scythe-clawed ornithomimid relatives known as avititans. The largest species on Eurasia is Avititan bicolor, seen above in scale with a human figure.

Avititans owe their ecological success to their strong social structures and their care of their young. Here are two Eurasian avititans with their offspring. Yellow-tailed enantiornithine tick-birds, Parasitophagus leucurus, can be seen on their backs.

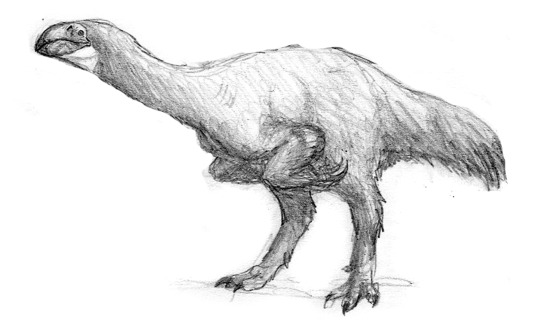

Oviraptoriformes made up another important clade of dinosaurs in this world.

Descended from bird-like ancestors, various clades of these animals live on as important omnivores, scavengers and even predators in many ecological niches. Above is Eblisornis, a common species found throughout Eurasia.

The bull-bird, Bosornithoides erythrops, is the largest and most prominent oviraptoriform on the Eurasian continent. It subsists mostly on plants and fruit, but will eat carrion if given the chance.

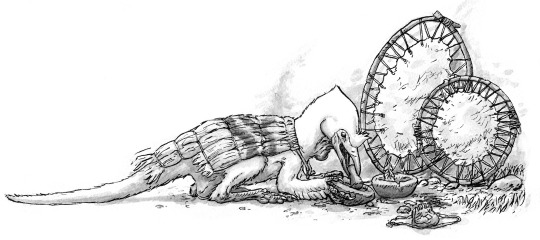

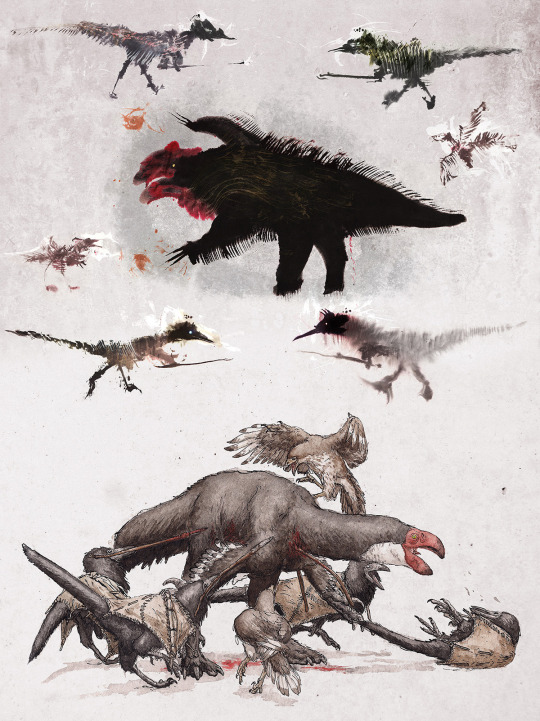

Hunting the wary and dangerous Bosornithoides is an important rite of passage for dinosauroids. The animals require coordination and group-work to bring down, and hunting one is a bonding experience for batches of young-adult nestmates. This ritual not only cements the dinosauroids’ social standing in their tribe, but also bonds the hunters together for the rest of their lives. The four hunters-to-be in this picture are accompanied by a couple of jackal-birds (Cynornithoides), domesticated pets that are almost as smart as the dinosauroids themselves.

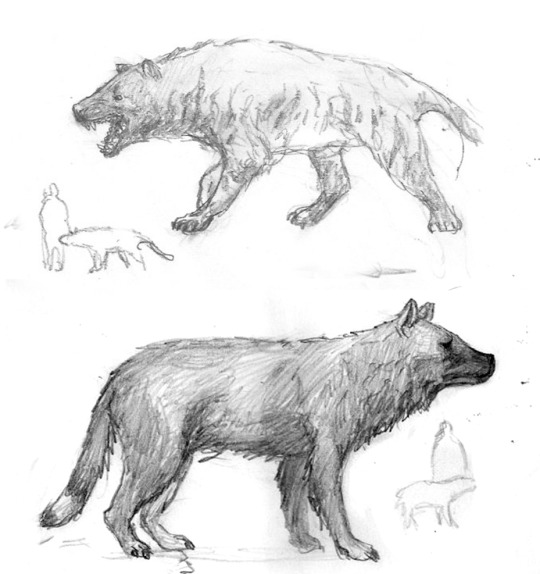

Many dinosaurs dabble in carnivory, but the main predatory niches on this version of Earth, are occupied by a diverse radiation of paradromaeosaurs, descendants of the famous “raptor” dinosaurs and kin. Paradromaeosaurs have diverged considerably from their ancestors. One lineage, known as the rhynchovenators, replaced their teeth with sharp, raptorial beaks.

The male and female of the common boreal rhynchovenator, Rhynchovulpes agilis.

A lean-legged Egyptian rhynchovenator, Rhnychovulpes aegypticus, atop a dead multituberculate mammal. The key to rhnychovenators’ success is their added tenacity and stamina. Even a small rhynchovenator can overcome comparatively large prey by continually harassing and chasing it into exhaustion.

The bald-headed Osteophaganax regalis is a common scavenger encountered across the Caucaus Mountains. Its males develop striking, black-and-purple wattles on their faces during spring.

Two more derived troodonts. Left, a tree-dwelling arbosaur, Toucanops dixoni, from one of the diverse and little-understood clades found across the South American continent. Right, the lean, narrow-beaked Halophagus sp. from fossil deposits in what is now China. This group evolved specialisations for marine diving and probably saltwater drinking, before becoming extinct during the Miocene.

The dominant guild of maniraptoran predators, the tyrannoraptors, evolved from “regular” dromaeosaurs with powerful, biting jaws. Some species living today, such as the Savannahdromeus shown above, are still very similar to the earliest forms. Despite its small size, the smart and social Savannahdromeus are apex predators thanks to their pack-hunting behaviour.

Another basal tyrannoraptor, Pantherdromeus - is a solitary hunter that is common across much of Eurasia. It probably represents a diverse and subtly-variable species complex.

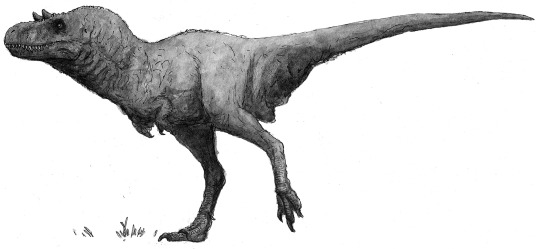

Solitary, basal tyrannoraptors eventually gave rise to the terrifying main-line tyrannoraptors in the last twenty-million years. The evolution of these animals was marked by the reduction of their wings and the enlargement of their legs, and jaws. Their tails developed into stiff and rod-like balancing organs. In some respects, they were the evolutionary echoes of the big-jawed, running tyrannosaurs, which had become extinct earlier on, during this world’s version of the Eocene period. Unlike tyrannosaurs, however, tyrannoraptors had well-developed social behaviours and intelligence; which, when coupled with their fast speed and terrific jaws, turned them into formidable apex predators. Above are the adolescent and mature forms of Metadromodaemon phobetor, a mid-sized hunter found in the Middle East and North Africa.

A scaled drawing of Wotandromeus bicolor, the terrifying, large-headed hunter of European forests.

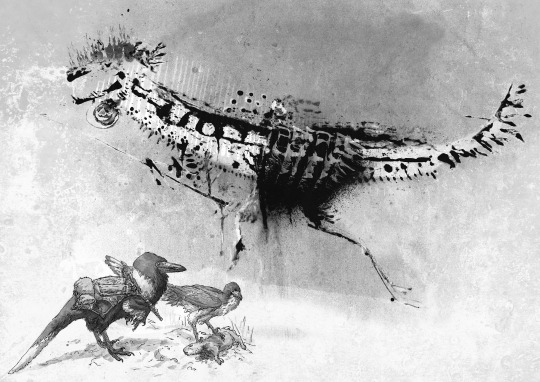

The seven-metre-long Melanorodromeus euceratus - also known by the Dinosauroids as “black thing” - is the largest predator on mainland Eurasia; but even larger forms are reputed to exist in Siberia and North America.

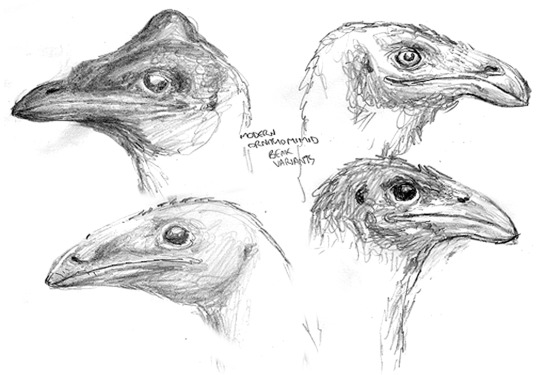

Let us now return to the Dinosauroids, their culture, and art. Above is a brief study illustrating the divergence of the two species of Avisapiens; A. saurotheos and A. tataricus, from ancestral eu-troodontid stock.

Especially A. tataricus shows considerable variation in beak shape, length and colouration. Above, right are the colouration of the Eurasian (top right, bluish-black), and Northeast Siberian (above right, yellowish-brown) races. Above, left shows a spectrum of variation in A. tataricus beaks. The cross-beaked and long, curved beaks occasionally crop up in certain bloodlines, which also have augmented song-memories. These individuals are revered as shamans in certain A. tataricus tribes; or are immediately killed-off as harbingers of doom in others.

Above, the extensive variation in the head shapes, beak lengths and crests of various races in A. saurotheos. The bottom-right sketch depicts a hybrid individual between A. saurotheos and A. tataricus.

A powerful hunter of A. tataricus, from the Carpathian Mountains, showing a stone axe and bent spear that are characteristically used by this particular tribe.

An artist/shaman of one of the settled A. saurotheos tribes living around the Balkans. He paints on animal skins stretched taut across circular frames, and paints using ground-up soil and other pigments, wielding a brush made from a wing-feather. The skin canvas also double as drums.

Art is one sure-fire way of identifying an intelligent species. This skin-painting shows a spear-hunter and prey, a painting by the aforementioned shaman.

Painting of a god or hero-figure with red tail feathers.

Painting of two shamans divining the future from the entrails of a dead flying animal.

Painting of a hatchling being trained by a village elder.

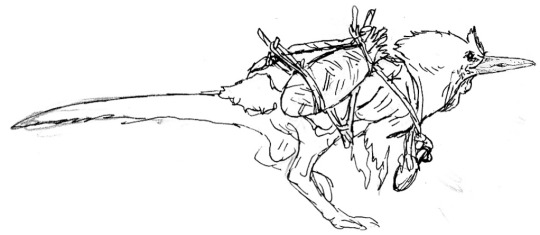

Studies of an A. saurotheos wanderer with a travel harness; and a duo of A. tataricus migrants with a domesticated bull-bird, a relative of the oviraptoriform Bosornithoides mentioned above.

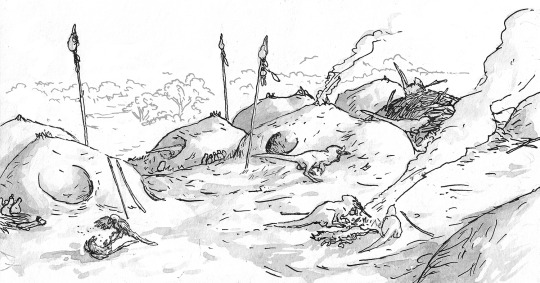

The view from an Avisapiens saurotheos village, showing the species’ characteristic nest-houses, and a pair of semidomesticated Cynornithoides jackal-birds playing in the village square. Note the heads mounted on tall poles, a sign of reverence to the spirits of the departed.

Detail of a brooding nest constructed by Avisapiens tataricus. Most tribes of these species are migrants that range across Eurasia, few build permanent structures.

Sketch of an A. tataricus wearing a travois-like travel harness.

Study of an A. saurotheos wanderer with travel gear.

A detailed study of the burly A. tataricus native to the Caucaus Mountains, complete with weapons, travel gear and ornamental cape.

Sketches of war-like A. tataricus tribes native to the Eastern Mediterranean region. These tribes are known for their ferocious (if impractical) war-masks.

Studies of two different warriors from two different Avisapiens tataricus societies.

A resplendent A. tataricus warrior from the Levant, wearing an ornate head-dress of feathers, and an obsidian-studded war-mask.

Studies for Avisapiens spear-throwers and wooden-slat armour; from a comparatively advanced period on this species’ societal development.

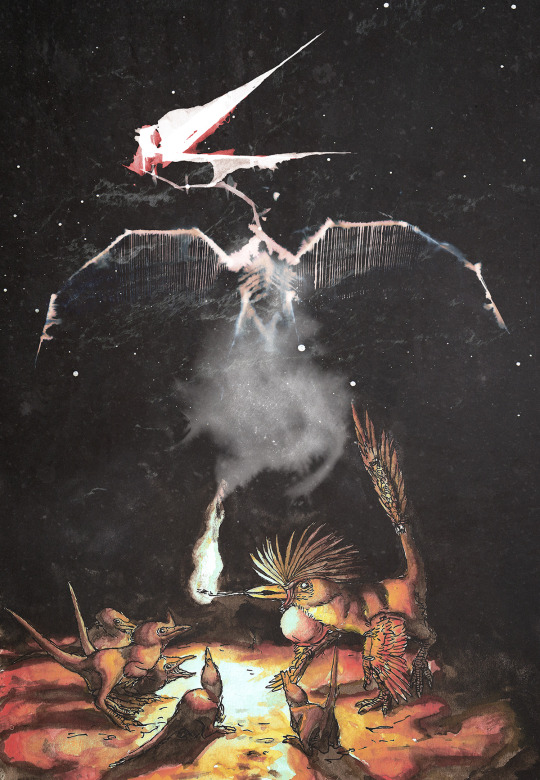

An A. saurotheos shaman entertains hatchlings with fireside tales of spirits and other worlds.

A band of slave-keeping A. tataricus warriors during a raid to an A. saurotheos village. A young shaman is captured and de-clawed.

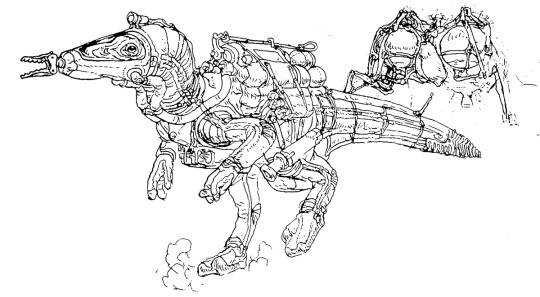

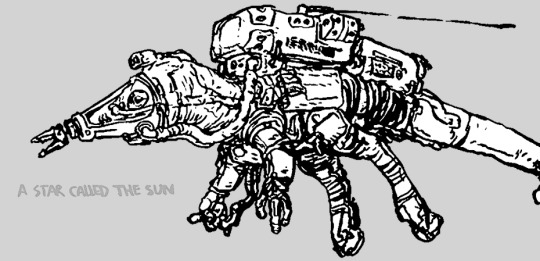

Simon Roy and I also dwelled on the far-future evolution of dinosauroid technology. The sketches above of a “knight”, moon lander and an astronaut were produced, but we did not pursue these scenarios seriously.

Let us conclude our visit to the dinosauroid tangent-universe with one last look at our artist/shaman, his village, and his paintings. Somewhere in deep time, they are still alive, and still waiting to tell us of their adventures.

A painting of an avititan family.

A painting of the dangerous, predatory “black thing”.

A painting showing numerous animals at a watering hole.

A painting showing an A. tataricus warrior.

Stylised paintings of spear-wielding Carpathian warriors.

Painting of a ferocious Aegean headhunter.

A stylised painting showing an immature dinosauroid.

Stylised painting of a warrior confronting a spirit-creature.

Stylised painting of a powerful Caucausian mountain warrior.

Painting showing a ghoul-like oviraptoriform animal.

Painting of one of the sky-gods worshipped by A. saurotheos.

A complex painting showing four A. tataricus warriors hunting a bull Bosornithoides.

Simon Roy and I may return to the dinosauroids universe one day with a real story; but truth be told we enjoyed world-building far more than inventing stories and characters.

- 2008 - 10/2019.

#worldbuilding#speculative biology#speculative evolution#dinosaurs#dinosaur art#dinosauroids#paleoart#creature design#c m kosemen#simon roy

435 notes

·

View notes

Photo

SUPER BIG NEWS: LEGEND OF NC DINOSAURS AND MONSTER BIRDS! Apparently my home state of North Carolina has become a hotbed for cryptozoological activity of the prehistoric survivor variety. This week The News & Observer - the second largest regional paper in NC - reported that a 20-year-old woman in the state capital of Raleigh spotted a pterosaur while waiting for the bus. The above drawing is her depiction of what she claims she saw. This story comes hot of the heels of NC being visited last year by the Japanese paranormal reality TV show What’s This? – Mysteries From Around the World which came for three days in September to hunt for an alleged plesiosaur in Lake Norman which is right outside Charlotte. Pterosaurs and plesiosaurs oh my! Though popularly depicted as a plesiosaur-type creature, the Lake Norman Monster - known affectionately as “Normie” - more closely resembles a large fish based on eyewitness sightings with the most popular candidate being an overgrown catfish. Nevertheless some witnesses have reported seeing a “dinosaur-type” creature in the lake as well. The most common rationale cited by cryptozoologists for the belief that Mesozoic marine reptiles inhabit certain lakes around the world is that these lakes are ancient. And indeed some of them are relatively speaking. Both Loch Ness in Scotland and America’s Lake Champlain - the homes of perhaps the two most famous lake monsters in the world - are both about 10,000-years-old and were formed at the end of the last Great Ice Age. Of course this still makes them far too young to be harboring any kind plesiosaur, the last of which died out 65-million-years ago. This problem is even more pronounced when it comes to Lake Norman which is a man-made lake created between 1959 and 1964 as part of the construction of the Cowans Ford Dam by Duke Energy. Being only 50-years-old there’s no way that Lake Norman could be hiding anything prehistoric! So what accounts for the alleged sightings? If we rule out pranks and hoaxes, the most likely cause seems to be cases of mistaken identity. Deer are common in the Lake Norman and are often seen swimming in the lake. Also large snapping turtles - some big enough that they have occasionally been mistaken for alligators - reside there but despite occasional reports there are no confirmed cases of actual gators in Norman though they do live in NC and can be found in lakes closer to the coast like Lake Waccamaw. Surprisingly freshwater jellyfish do reside in Norman. There’s also the folklore factor. As argued by Michael Meurger in his 1989 book Lake Monster Traditions: A Cross-cultural Analysis (co-authored with Claude Gagnon) there is just something about large bodies of water that inspires people to make-up stories about them whether it be that such lakes are bottomless, hide buried treasure, are the final resting place of victims of unsolved murders or harbor a monster. It doesn’t matter if the lake in question is natural or man-made - in fact as pointed out by Benjamin Radford and Joe Nickell in their 2006 investigative study Lake Monster Mysteries, Lake Norman is far from the only man-made body of water in the US to allegedly contain a cryptid (p. 151). When it comes to Raleigh’s supposed pterosaurs, similar factors seem to be at work there as well in that we are once again dealing with the familiar phenomena of animal illiteracy. As paleontologist Darren Naish writes in his wonderful little book Hunting Monsters: Cryptozoology and the Reality Behind the Myths (2017), one of the side-effects of the widespread popularity of prehistoric animals is that depictions of creatures like pterosaurs are so pervasive that “a great many people… have some concept of what a pterodactyl is, yet are stunningly naive regarding the living animals that live on their own doorstep” (p. 184). This seems to be a perfect summation of the situation we have here. NC is home is a sizable number of large birds including cranes, storks, pelicans, spoonbills, osprey, several types of egrets, herons, hawks, owls, three types of ibis and two types of both vultures and eagles. I live about an hour outside Charlotte and have literally seen most of these birds in my own backyard. They are big and can easily startle people - especially when you open your curtains in the morning and find a crane standing a foot from your window, which is something that actually happened to my mom. But people who aren’t as familiar with the local wildlife or do as much backyard bird watching as I do may not be able identify these birds and think they are seeing a “flying dinosaur.” James Robert Smith, a friend and local author of several fantastic works of paleo-fiction including The Flock (2006) and Withering (2014, under the pen name Robert Mathis Kurtz), related the following story about just such a situation to me when discussing the recent flap of supposed pterosaur sightings…

One of my old friends saw a great blue heron in flight (he’d never seen one) and insisted that he’d seen a pterosaur. I kept trying to convince him that he’d only spotted a heron but he resisted. Finally, one day he saw it again and it landed and he admitted that it was “just a bird.”

Further complicating matters is that in covering this story The News & Observer reached out to creationist Jonathan Whitcomb about the sightings. The issue of creationism isn’t one I’ve addressed on this blog before despite the fact that I regularly deal with the topic seeing how I teach a class on the intersection of dinosaurs and religion. For anyone not familiar with the subject, paleontologist José Luis Sanz offers a sufficient definition of creationism in his book Starring T.Rex describing it as “a political instrument of religious fundamentalists… derived from a literal interpretation of the Bible… which denies any evolutionary dimension to life, the Earth, or the Universe.” (p. 79) Creationism isn’t a very old movement, with its origins in the late 19th-Century, but has nevertheless gained a lot of traction is certain Christian communities in the US. One of the chief claims of creationists like Whitcomb is that dinosaurs and man lived alongside one another (God made them on the same day after all) and that some dinosaurs - and dinosaur contemporaries like pterosaurs and plesiosaurs - are still around today. Whitcomb is particularly infamous for his 2006 book Searching for Ropens in which he argues for the existence of a giant (16 to 23 ft. wingspan) bioluminescent, grave-robbing pterosaur residing in the jungles of Papua New Guinea. Whitcomb actually traveled to Papua New Guinea where he collected alleged eyewitness sightings of the Ropen from locals. Many of these locals were Christian converts who appear to have been impressed by Whitcomb’s status as an “important” white missionary (how he fiancees these trips) from America and were eager to testify to him about their encounters with the Ropen which Whitcomb then reinterpreted as encounters with a pterosaur. I say “reinterpreted” because it’s pretty obvious from even just a cursory overview that the Ropen is actually a kind of demon or vampire from the indigenous folklore - the name literally means “demon flier” - that many of the local people still believe in despite - or more likely because of - their conversion to Christianity. According to The News & Observer, Whitcomb claims to have nine different alleged NC pterosaur sightings on file including this most recent Raleigh encounter. The News & Observer reprinted all of these sightings as part of their story and from reading them I’ll say it’s not entirely clear why anyone would seriously think these people had seen a prehistoric winged reptile. But then it’s not clear how on the level Whitcomb is either. One of his key pieces of evidence for the existence of modern-day pterosaurs is a photo of Civil War soldiers standing with a dead pterodactyl, a photo which is incontrovertibly known to be a film prop (not just the pterosaur the whole photo is a prop) made for and used in an episode of the TV series Freaky Links in the late 90s. Loren Coleman actually has the prop pterosaur hanging in his International Cryptozoology Museum in Main. Nevertheless Whitcomb dogmatically maintains the photo is real! Naturally I’d love it if my home state harbored living non-avian dinosaurs and related creatures but the prospect is more then unlikely. So I guess I’ll just have to be content with the multiple avian dinosaurs I get to see everyday in my own backyard. And for anyone who doesn’t “get” the joke which is this post’s title I explain it here.

#pterosaur#pterodactyl#pteranodon#plesiosaur#cryptozoology#dinosaurs#dinosaur#darren naish#james robert smith#lake monster#north carolina#creationism#creationist nonsense#ropen#raleigh#lake norman#lake norman monster

8 notes

·

View notes