#also i was wondering whether to make this an edo period japan thing or a more generic fantasy setting and i think ill have to go w the 2nd

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

move aside takemichi/everyone it's time for kisaki/everyone

#kisaki gets a harem. as a treat#all of these relationships will be so different i cant wait to write them all sjdhd#also the baji trio is here preemptively even though i hardly have a plan for them yet. ot3 privileges i guess#court jester omegaverse#this might be the first time i dont struggle with finding a title. let's hope that's a good sign#also i was wondering whether to make this an edo period japan thing or a more generic fantasy setting and i think ill have to go w the 2nd#bc i dont remember much about japanese history anymore by now and that extra research would take a lot of time when i could just#isekai them and dont worry about it#lmao#the notes app background is so i can have something nice to look at while i write. i dont know if its really that useful#but it'd feel weird to write without it now so it Stays

1 note

·

View note

Note

do you still take asks? if so, could you explain tanjirou's hanafuda earings? i've seen some people online (like insta and other such places) claim that the design is one of a flower, but i always thought it was of a sun since it was supposed to be like a token for the sun god or something (disregarding possible [and hopefully unintentional] symbolisms coming from ww2)

whenever these people say these, they go back on to the earings being called hanafuda cards, and that hana means flower. i'm not that smart when it comes to japanese things or hanafuda cards specifically, so if you could, can you explain the hanafuda cards and the design on tanjirou's earings?

thank you and i hope you're having a lovely day (love your blog, btw, esp the art and japanese trivia posts)

Hahaha.... my attempted answer to this met so many technical difficulties, this is my third version, I think, hahahaaaaaa. TwT We shall indeed endeavor to keep this related to the original Sengoku period design of the earrings and their relation to Hanafuda cards, though indeed this is a Heisei/Reiwa period production and it's unavoidable that the similarity would be read in a post-WW2 context. It's not that I don't have things I could say on that, but I prefer not to go in that direction either (and people who choose to use the alternate design have my support). Short answer, though: nope, not a flower design!

The sun symbolism and its representation of Japan supersedes Muzan’s birth by at least a few centuries, and in its earliest uses with a simple circle to represent it, it wasn’t even always defined by the color red. The bright color red has been, however, long since symbolic of the sun, so it’s unsurprising that at some point the two symbols came together. No one knows who to credit for its design as a symbol to represent the emperor, but it seems this started in the Sengoku period, same time Yoriichi and his mother Akeno were around in the 15th, 16th centuries or so (but hard to say). The imperial use is due to the Shinto mythology that the emperor is descended from the sun goddess, Amaterasu. (I’ve have heard some KnY theorists posit that certain characters represent different gods in the Shinto pantheon and that Yoriichi represents Amaterasu (who indeed has historical male representations), but I don’t buy into those theories.)

While’s it’s not to say Amaterasu couldn’t be beseeched for healing a deaf child, she doesn’t strike me as the first goddess you’d go to for help with that, so I had originally suspected Akeno might have been more of a practicing Buddhist seeking the help of Dainichi-nyorai (the Buddha that represents the sun, if we put it very simply), or that she might had been a follower of the Nichiren sect, which embraced syncretism with Shintoism and used the “Nichi” (sun) symbolism pretty heavy-handedly (that sect tended to encourage a devout following of women, too). That’s as far as I find relevant to read into this side of things, though, for a look at Akeno’s altar shows us a round mirror often used in Shinto worship (some scholars suspect the round shape represents the sun, too, but it’s not at all limited to being a sacred item to represent sun-related deities). However, religion is and always has been complicated, and Akeno may have been a follower of any pure or blended strain of Shintoism and/or Buddhism.

Tl;dr: Akeno has a profound faith in some kind of sun deity.

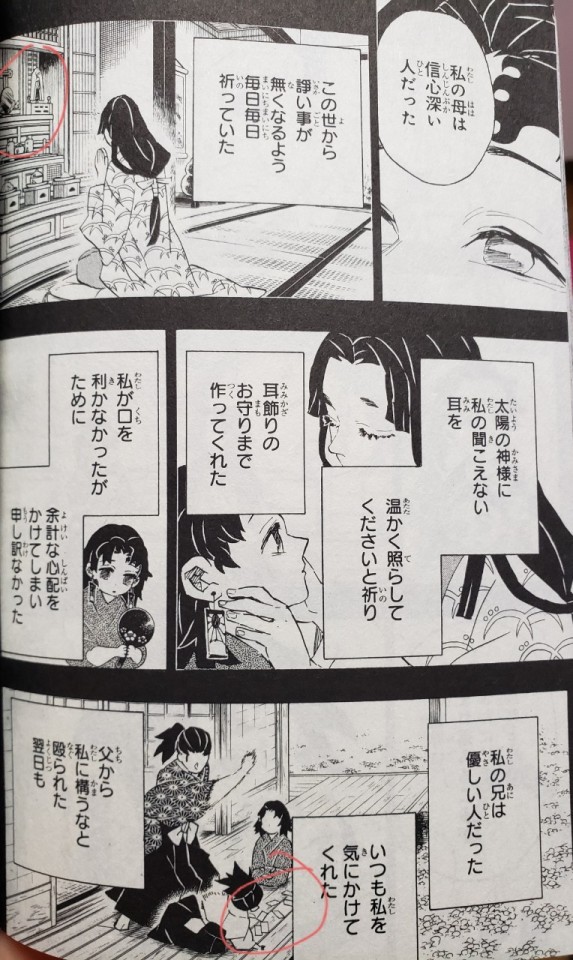

After all, Yoriichi says this very plainly on this page in Chapter 186, “My mother was a person of very deep faith.” In addition to her daily prayers for peace, she made the earrings for Yoriichi praying that the “god of sunlight” may shine on and warm his unhearing ears. We have no further definition of this “god of sunlight,” so it could be Amaterasu, Dainichi-nyorai, any possible unnamed sunlight god she might have had faith in (Gotouge tends to borrow heavily from a lot of different religious traditions without narrowing them too far into any particular sect or strain). We may not be meant to read this in such detailed historical context as Amaterasu because it is left so ambiguous, but the art representing the sun is pretty ubiquitous throughout Japanese culture by that period.

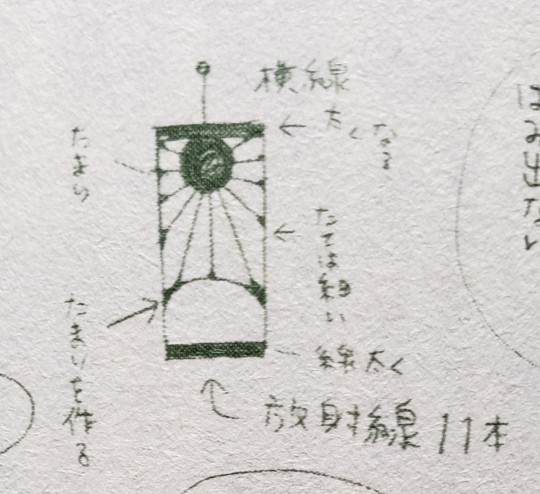

And would you look at that, little Michikatsu and Yoriichi were playing a card game! Hmm, I wonder what? While I cannot claim anything one way or another about how Gotouge and her editors saw it or what they may think of it being seen that way abroad, the rays inevitably make it seem similar to the 16-ray naval flag, and the earlier color illustrations did have red lines. However, at some point the design settled into using 11 thin black lines only, with an emphasis in Gotouge’s character design notes (from the first fanbook) on the pooling thickness at the ends of the lines. This feels to me a bit like inky brushstrokes, and there is also design emphasis on the thick lines at the tops and bottoms of the earrings. These details, as well as the notes (cropped out of the image below) about the movement and weight of the earrings around Tanjiro’s face make them seem to have the thickness of light cardboard, which altogether makes them very similar to Hanafuda cards. Most specifically, doesn’t it look like this card featuring pampas grass and the moon?

While Hanafuda does literally mean “flower cards” and there are designs grouped around certain themes (even if the theme itself isn’t a flower, the design will typically incorporate a plant), I feel fairly confident saying the design of Yoriichi’s earrings is not a flower, and indeed the sun.

Primarily because these earrings aren’t Hanafuda cards! Hanafuda technically didn’t exist until after Yoriichi’s time, and was adapted from a Portuguese card game. Said game was initially illegalized at the same time Christianity was illegalized, but the Edo public loved their card games, and reinvented it every time some previous version was outlawed for its use in gambling. Even today, there are many, many different versions or reiterations of Hanafuda under the same or different names. I have never played though, and will not attempt to explain it. ^0^;; (I have cousins who grew up playing the Hawaiian version, though.) It was finally legalized in the Meiji period, and the first fanbook even lists this as one of Zenitsu’s favorite games.

By the Taisho period anyone would had been familiar with it, leading Muzan to describe Tanjiro to Yahaba and Susamaru as “the demon hunter who wears earrings that look like Hanafuda cards.”

While my research didn’t take me this far, I’m willing to bet card games with similar illustrations existed far prior to Hanafuda, and whether or not Akeno would had been influenced by them is anyone’s guess. But as she made them as religious items, that still makes them not game cards. I do assume she used high quality washi paper though, the finest she could afford as the wife of a high-ranking samurai. Good washi is strong enough to last for centuries, and even used to be used for making clothing because it’s so durable. But it’s also lightweight, she wouldn’t want to weigh Yoriichi’s little ears with precious metals or anything like that, I believe!

This all being said, I have most certainly noticed a trend of actual Hanafuda cards being used in accessories, everything from earrings to necklaces to charms to hang on facemasks to manicures. The only time I’ve seen this sun design has been in clear reference to Kimetsu no Yaiba, though!

This went in a lot of different directions, Anon, but I hope that clears things up about the sun and Hanafuda connections more than it clouds everything in unnecessary details. XD

#KnY fandom theories and meta#KnY nerdery#KnY reference#tsugikuni yoriichi#tsugikuni akeno#kimetsu no yaiba#demon slayer

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Soul Society tattoo culture

These thoughts are inspired by @anza-redstar and @recurring-polynya's post about Hisana and SS’s tattoo culture, which I think is just fabulous.

I was thinking about this with Akon and like, whether the horns are something he grew into organically as a certain type of soul or whether it was a conscious body mod and if it’s the latter is Akon the guy everyone else goes to for all their body mod/fashion consults, because IF SO I am VERY into that!!

I do not know much about tattoos inside or outside of the Japanese context, but it did make me think about Okinawan hajichi and Ainu tattoo practices, which have come up in discussion at my work recently. This is something I’m still learning about, and I feel weird about bringing these topics into a headcanon about manga, even fleetingly, because the real-world conversations are very much about historical and ongoing Indigenous oppression, genocide, and cultural erasure. So I’ll just leave that at links to information, because I think the topic is important and definitely worth checking out! And say that it inspired me to think about how many tattoo cultures exist in Japan and where the contemporary taboo against tattoos/association with yakuza came from.

PRINT CULTURE

In addition to evergreen histories of violent colonization, it turns out that the Edo period was a big turning point in terms of tattooing in Japan. It was simultaneously the point at which modern tattooing developed in Japan as well as the period in which laws outlawing it started getting passed. (Of course!) Apparently the rise in modern tattooing was partially inspired by the development of woodblock printing, which showed tattooed heroes and began integrating these visuals into the popular culture, which is interesting to think about in the context of SS because I imagine these were also crucial in popularizing the practice in SS, too, since they are participants in cultural flows with the living realm (perhaps an even greater capacity back then than when Bleach takes place, given that mainstream belief in the existence of youkai in the living realm at that point would have been stronger). I would bet money on shinigami having also developed their own tattoo culture in-house, but I love the idea of there being critical interplay there, too!

WHO ENDED UP IN POWER?

Anyway, like the outlawing of most practices, in living-realm Edo it comes down to control (and a desire to "appear civilized" to other powers/to avoid their own colonization). The Tumblr post that inspired this one mentioned that most of the tattoos etc. we see are from shinigami, often noble families, rather than commoners, so it definitely seems like SS’s cultural history has unfolded as the reverse: There’s a sense of it being a high-end practice in SS/Seireitei (like it is in many cultures in our world too!), whether by birth or by virtue of high standing as a Gotei 13 officer. Perhaps the element of control exists in who is allowed to be tattooed, instead. Inasmuch as SS is modeled off the Edo period and inasmuch as its system of government reflects that, maybe it’s also a historical alternative in terms of who has ended up in power at the end of the violent pre-SS/Seireitei history that Yamamoto/Unohana/Kyouraku/Ukitake have alluded to.

It also makes me wonder whether these social mores would have been different, or would have changed, had their various dust-ups with other communities (i.e. the Quincy) gone differently. I remember like four things about TYBW, two of them are Rukia’s bankai, and none of them are about why anything happened or what the Wandenreich is, so CAN’T SAY MUCH BEYOND THAT UNTIL I FINISH MY RE-READ, but.

INDIVIDUALITY FOR WHOM?

The Seireitei seems to like order and uniformity at least to some degree (Yamamoto loves him some uniforms). But I imagine zanpakutou being so central to their society would definitely impact how they thought about these things, given how incredibly individual that relationship and its physical manifestation gets in its highest forms. (I mean, to bring in movie canon, if we’re willing to execute Kusaka because it is SACRILEGE to glitch and have the same zanpakutou as someone else, LOL, I guess individuality has to be somewhat important. Because like, my dudes, anyone who can summon shikai seems like someone you want to keep! There aren’t that many of you! You need all the help you can get!) Do you get to be individual if you’re not seated, or is that a privilege you have to earn? Do cannon fodder shinigami dream of the day they, too, might get to relish in the bold act of braiding their hair? Does Komamura still consider himself undeserving of such a privilege, hence the helmet? (Because god knows he is easily one of the most normal out of all this weirdo coworkers... Like Matsumoto implied, he needn’t have worried about standing out.)

This probably needs to be its own post, but I’m also interested in general about shinigami and their relationship to their bodies, which are clearly still important but also like… can’t possibly be the same relationship that regular humans have to theirs. Bringing reiryoku into one’s bodily conception (centering it, even) affords so many cool/interesting potentials! (As always please feel free to share your own hcs on this!)

#akon#bleach sociology#bleach headcanons#not a historian of japan#nor of tattoos#though LOL one time my sister suggested we all get a tattoo to honor the memory of my (japanese) grandmother#and i was like YOU GOOF i cannot imagine something she would be less proud of#she doesn't even like ear piercings!#both my sisters are tattooed though#just not with my grandma's handwriting#....yet

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Flowers of Jigokuraku

Disclaimer: this essay will refer to fairly recent chapters (53 and forward), so if you are a new reader, I advise you to catch up before you read it. And as usual, I am not Japanese nor Chinese, so my arguments and explanations are based on the research I made, but I won’t pretend I’m absolutely right on everything. My goal is merely to provide a comprehensive understanding of the references used in Jigokuraku, as well as a historical context to give the in-story points of view more perspective. English isn’t my native language as well, so I hope my explanations won’t be too wonky, grammatically speaking. On these words, I hope you’ll deem this essay an enjoyable or educative read. [Originaly posted here]

In this essay, we’ll study the cultural references used for the island and its inhabitants. We’ll see the reason why certain characters seem to have a rough knowledge of the island, providing a historical context that’ll help us understand why and how these legends are known both in-story and from a narrative perspective. The legends mentioned will be related to Xu Fu and the Immortals, since they are the basis for the mystical island in Jigokuraku.

I. Education during the Edo era

The Xianren, the Immortals, are brought up by both Senta and Toma on chapter 16. These characters have generally proved fairly educated and useful to provide insight to the reader through their discussions with other characters (GabiGang and Chôbe). However, one could wonder **why** apparently random characters like them would know about that sort of thing.

The Tokugawa period represents roughly 250 years of peace and stability throughout Japan and, despite the sakoku, the isolation of the country, it still received influences from Korea, China and Europe (via the Dutch traders). This general stability provided the perfect set up to develop Japanese culture as we know it, and to spread ideas through education. Indeed, education wasn’t solely reserved to the upper Samurai class, and many schools would open everywhere to provide at least a certain level of reading/writing/counting to young Japanese, and going as far as offering classes on Rangaku (Dutch studies), Kangaku (Chinese studies) or military strategy for the ones who could afford it.

Terakoya, temple schools opened for commoners, flourished during the Tokugawa era with a function similar to our current primary system. These schools developed with the blessing of the Shogunate, which would use them to promote Confucianism – the set of morals used as a basis for Japanese society during the Edo era. Such system would indeed provide all the knowledge necessary for the four main casts (Samurai, Peasants, Artisans and Merchants) to understand where they stood in the hierarchy and how much they could afford to learn as well. Furthermore, the daimyo, the feudal lords, would also create hankô, the schools of their domain (Han), to provide education to the children of their retainers. These *hankô* would follow the model of Shôheiko, the Confucian school administered by the Shogunate itself, in order to promote the study of Kangaku, Confucianism, history and even medicine.

Furthermore, knowledge could be more easily spread through time thanks to the development of woodblock printing. As such, even a commoner could have access to various texts and illustrations, which helped the general population learning about both historical facts and legends about both Japan and China. Sinophiles of this period would work to conciliate historical facts and legends and have them work together to integrate Chinese elements in Japan’s history without negating Japan’s own cultural and historical identity, while certain legends would see themselves modified and expanded according to both China’s and Japan’s cultural needs.

All in all, these facts about education and scholarly pursuits can easily explain why Senta and Toma would know about things such as the Immortals: it could have been part of what they studied before coming to the island, whether it was from a historical, philological or religious point of view. They would at least have a general knowledge of it because of the schooling they’d been provided when they were younger.

II. Xu Fu and the search for immortality

The story of the half-legend, half-historical figure Xu Fu starts in China, with his appearance in the Shiji (Records of the Grand Historian) by Sima Qian (145 – 90 BCE). The character quickly gained popularity and his story was expanded in later writings. These writings reached Japan during the Heian period (794 – 1186) and were further developed during the medieval period, yet their peak happened during the Edo era. As previously mentioned, Kanraku, the Chinese studies, became common under the Tokugawa thanks to the Confucian system imposed by the Shogunate. This in turn helped the study of Xu Fu and his quest to integrate it in Japanese history and culture, by notoriously adding that the quest for immortality led him to Japan – something never mentioned in the initial Chinese texts, but that appeared during the 10th century, thus potentially suggesting an influence between China and Heian Japan during that time. This notably led to three theories as to where Xu Fu and his party landed, and what Mount Penglai (where the Immortals are, known as Hôrai in Japanese) is exactly. The first two theories were made during the late Heian period, and situated Xu Fu’s landing near Mount Fuji or in Kumano (currently Mie Prefecture, near Nara). Without entering details (because it’d require a whole post just for Xu Fu), these theories became known during the Ming and Qing dynasties, as Japanese monks and scholars travelled to China and used the story of Xu Fu as a basis of Sino-Japanese friendship through cultural common grounds. The third theory appeared during the following Kamakura era (1185 – 1333), and located Xu Fu at Atsuta Shrine (Nagoya), with the shrine itself being Penglai/Hôrai. During the medieval period, these writings and theories were used as a basis to give Japan a proper position in Chinese culture, but the story really started gaining traction under the Tokugawa, thanks to the cultural exchange between Japan and China as well as the general intellectual development in Japan.

Historiography became widespread during Edo era, compiling and inventing stories became common to the point even Jesus and Moses had the story of their travel to Japan. Furthermore, these stories became popular with the many works of zuihitsu authors (miscellaneous writings), who used these stories to gain more readers. Edo historian Hayashi Razan even confirmed through his researched that Mount Fuji could indeed be Mount Penglai/Hôrai. According to the stories of that time, Xu Fu brought Chinese methods tied to textile, agriculture and medicine with him, sharing them with the inhabitants of the region and settling down there as well. Yet Kumano remained the most popular theory, leading to the creation of a shrine, Xu Fu’s tomb as well as the tombs of his seven retainers, Jofuku no miya (Xu Fu Palace), Mount Hôrai... These elements were used in numerous texts, travel records and poems, even famous ukiyo-e painter Hokusai drew Painting of Xu Fu Looking Up at Mount Fuji. The legend became larger as the theories about Xu Fu’s location varied and covered Japan (not counting Hokkaido), from Aomori to the North of Honshu to Kagoshima in Kyushu. All of these legends around Xu Fu were supported by the bakufu and the daimyo, who used them to promote the cultural importance of their Han and encourage tourism.

From an in-story perspective, we can see how and why some characters would be knowledgeable about certain things on the island, or at least recognise certain names, and even why the Shogun himself decided to take the search for immortality so seriously. From a narrative perspective, I commend UG for his twist on the location of Penglai/Hôrai, making it a mysterious man-made island south of the Ryukyu Kingdom (nowadays Okinawa) that fits the descriptions of a paradise... Only at a first glance. It gives the readers a refreshing take on a legend that has been told and modified for centuries to fit all sorts of narratives, and makes the story much creepier.

III. Xianren, the Immortals

Before talking about the Immortals and the material given by UG, we should see where the concept of immortals comes from, and how it evolved in time.

The concept itself comes from a religious movement called Fangxiandao, the Way of Mages and Immortals. This movement came to existence during the Springs and Autumns period (771 – 256 BCE), but fully developed during the Warring States period (771 - 256 BCE as well) and united scholars of various specialities (alchemy, divination, rituals, exorcism...) around rulers and aristocrats seeking physical immortality and under the belief that Immortals lived in the islands of the Yellow Sea and the East China Sea. Theories relating to Yin Yang and the Five Elements emerged during the Warring States period, and seemed to include the Yellow Emperor as well, since he was perceived as a Taoist Immortal (and is referred as one of the first Emperors in the previously mentioned Shiji). It is thanks to this movement that the concepts of the lands of Immortals (Penglai, Fangzhang and Yingzhou – nowadays Mount Kunlun) have been formulated and became the reason of many quests in search of these places. The most famous one is Xu Fu’s search for immortality, for which he’d been provided with a thousand of young boys and girls, and who never came back from his search. The Fangxiandao opened the way to Taoism under the Han dynasty, but the core concept of immortality and Immortals remained despite the religious shift. With Taoism, an Immortal becomes an incarnation of duality, mobile yet without form, residing among the stars and in the deepest caves and giving sacred texts to their most deserving apprentices only. I’m not going to explain the different types of alchemy and the rituals that lead to immortality, as this topic has already been explained by u/gamria and in the manga itself. However, I hope this explanation on what the Immortals are from a cultural point of view helps understand why certains characters in the manga would react to them as if they were somewhat aware of the general ideas about the Immortals and a character like Xu Fu. It is thanks to the use and expansion of Chinese legends that these elements became known from the Japanese population during the Edo era.

The most famous Immortals are the Eight Immortals, divine beings in Taoism popular both from a religious and literary perspective. The most famous pieces concerning them are The Eight Immortals Cross the Sea and The Immortals Celebrating the Anniversary of the Goddess. The first one relates the crossing of the sea to go to Penglai (or visit the goddess Xiwangmu), during which they renounce to take a boat and decide instead to show their magical skills by transforming their respective amulets into one. This action displeases the Dragon-King, who captures one of the Immortals, which leads to a battle. The situation is solved when Bodhisattva Guanyin reconciles both parties. The second one relates the Peach Festival, a feast of immortality organised by the goddess Xiwangmu, making the Eight Immortals a symbol of longevity and immortality. They are also the basis for a martial art imitating the movements of a drunk person, and based on a text during which the Immortals are drunk. Interestingly enough, counting Mei, we have eight Immortals drunk on Tan in Jigokuraku. And it’s still fine to remove Mei from the count, because it’ll make seven Immortals... Like the seven retainers of Xu Fu, according to the aforementioned writings that could be find during the Tokugawa period.

Now, concerning our Immortals, Rien and his friends, who have been tied to Xu Fu in chapter 53. I have noticed specific references concerning them, aside from Taoism: the flowers associated with them, which in my opinion have been purposefully chosen by UG for their cultural symbolism. I’m not going to make research on their official names though, since I don’t speak Japanese nor Chinese and would rather avoid misinformation caused by my own ignorance. If someone else feels like doing that, I’d certainly be glad to read it!

Rien: as it raises unstained from the mud, the lotus is commonly associated with purity and perfection. It is also one of the Eight Auspicious Symbols of Buddhism, a throne for Buddha, as well as the flower that grew under his feet when he walked. In China, it is one of the 4 major flowers, and it’s associated with Summer as well as He Xian-gu, one of the 8 Immortals.

Mu Dan: the peony has a major significance in China, both at a cultural and political level. It was the national flower during the Qing dynasty (1644 – 1911) and it is considered the King of Flowers, being associated with wealth, honour, aristocracy, love affection and feminine beauty.

Tao Fa: the peach blossom is associated with vitality and immortality, since it blooms before the leaves sprout. Peach wood was also believed to ward off evil spirits, and thus peach wood staves would be used for such purpose, especially to clear the way for the Emperor.

Ju Fa: the chrysanthemum is one of the Four Gentlemen in Chinese culture, along with plum blossom, orchid and bamboo. It is associated with Autumn and the 9th month of the year, as well as joy and long life.

Zhu Jin: the hibiscus is a popular flower associated with fame, riches, glory and splendour, given as a gift to both men and women.

Ran: the orchid is associated with love, beauty, wealth, fortune and unity. As such, it can also be used as a symbol for married couples. It is also associated with scholarly pursuit, nobility, integrity and friendship, as well as Confucius himself. It is a flower of Spring.

Gui Fa: the sweet osmanthus (cassia spice tree) is a flower traditionally praised by poets and associated with the Mid-Autumn festival in China. Osmanthus wine is seen as typical “family reunion” wine. Since it sounds similar to the word for “expensive, noble, valuable”, it is associated with these concepts. According to a legend, the moon has a cassia tree that produces a drug for immortality.

Mei: the plum blossom is both one of the Four Gentlemen and one of the Three Friends of Winter (with Pine and Bamboo). It is a symbol of longevity since, like peach blossom, the flowers bloom before the foliage sprouts. Its five petals are also associated with the Five Gods of Prosperity and the Five Good Fortunes.

As you can see, it looks like UG didn’t pick the flowers used to create Lord Tensen just because they were pretty. These flowers hold a notable cultural importance, and reflect well the high status of Lord Tensen on the island. It’s the botanical equivalent of screaming at the reader “*they are the boss of this place*”, if you will. Interestingly, these symbols are the part I started with for this essay, since in its first form I was seeking an answer to the self-asked question “are the flowers used for Lord Tensen significant one way or the other concerning the plot”, and decided to do some research based on the botanical, cultural and medicinal aspects of the flowers (cue the title of this essay, which I liked and kept because it’s still relevant)... But it was inconclusive on my end, and I’m not educated enough on these matters to dig them properly. Still, it was interesting to learn more about the cultural significance of these flowers and the potential reasons why they have been selected by UG for his characters.

To conclude, we can see through the research on certain references given by the characters in-story that there are two interesting layers: first, education during the Edo era, the interest for Chinese culture and its implementation in Japanese texts and how it is reflected via the comments and explanations provided by some characters. Second, the actual references used by the author, their origin and how they are implemented in the narration to construct a story that provides the reader with a new take on an ancient legend.

While I did my best to keep it short, it also means I didn’t go as in-depth as I could have, but I wanted to provide a general explanation on philology without going in too deep and ending up lost in my own thinking pattern. Still, it was very interesting to read about these elements, which provided a much clearer narrative frame for. I do hope you found it as entertaining or informative as I did!

Sources

Education in the Tokugawa era

Sinophiles and Sinophobes in Tokugawa Japan: Politics, Classicism, and Medicine During the Eighteenth Century

Wai-ming Ng, Imagining China in Tokugawa Japan: legends, classics and historical terms

Fangxiandao , Xian , Eight Immortals

Taoism in Japan

Chinese Symbols

Flowers and Fruits

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

As excited as i am to watch this Mexican noir, it should be shocking there isnt much Mexican film noirs like theres quite a few Mexican films with noir elements like use of shadows and lighting especially in the sexual sense and maybe a gun or two and maybe a gangster but never noir noirs like the united states and European film noirs and i think its the same reason Japanese noirs spread out from the late 40s to even 1960s is not only could studios really not afford to make film noirs in abundance that american and european noirs could affors but i also think its bc both mexico and japan during the 40s-60s were still trending in making films centered around very ground in old stories that are extremely famous whether by history or just folk tales like mexico was really into showing films centered around the revolution from the 1910s and colonial times and same thing i found with discovering a lot of Japanese films this same era is a lot of edo period but samurai films and meiji period and so forth but i think its bc they couldnt afford it AND both countries were really into making films of famous cultural stories and aesthetics and eras that would really join the country's pride in their roots. Just wondering.

#Cherry says#this is very gemini for me to post since nobody cares BUT#it came in my head when i picked up my Mexican noir#i dont think i heard much mexican noirs or elements outside late 40s early 50s#but u know japanese noirs are all spread out too#so much so they blend in the new wave era#man white bitches and their money they have EVERYTHING legendary cultural tales and film noirs like shut up rich bitch

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Koutetsujou no Kabaneri: Geographical Locations

(sorry this is super long but I can’t use a Read More because of the damn apostrophe glitch...)

In the absence of a proper map of Hi-no-Moto, I thought it’d be useful / interesting to compile all the information and theories I know of concerning the location of stations etc in order to try and map the journey of the Koutetsujou throughout the series and beyond. If you happen to have any contributions or corrections then please add to this list! I’m also interested in hearing guesses other than my own for stations that were seen or visited along the way that don’t have a confirmed location.

To start with, Aragane Station.

Aragane Station is located within Izumo Province (confirmed in prequel novel), ‘an old province of Japan which today consists of the eastern part of Shimane Prefecture,’ within the Chugoku Region. (The map shows Japanese provinces in 1868, at the end of the Edo Period.) Aragane is the location of the opening of the anime series, and after it is overrun the main characters decide to head towards Kongoukaku aboard the Koutetsujou.

(I’ll cover Kongoukaku later on, but for now let’s assume that the assumption of the Japanese fandom is correct and that it’s further east than Aragane.)

Prior to the Koutetsujou’s arrival at Aragane Station, it travels past Hayatani Station, which has fallen to the kabane. I don’t know of an exact location for this station, but given that we know Mumei is heading towards Kongoukaku, it is likely to be located to the west of Aragane.

Following the departure of the Koutetsujou from Aragane Station, the next stop is Yashiro Station (and I hope you’re ready for speculation because again, I haven’t seen any official info regarding location).

There was previously a town named Yashiro that merged with two other towns to become the city of Kato in Hyogo Prefecture, so I decided to look into that location as it lies between Aragane’s location and where Kongoukaku is likely to be. The Koutetsujou’s journey to Kongoukaku involves the risky decision to take a route through the mountains in order to reach their destination faster, and looking at a map that shows the topography, Yashiro / Kato is a potential fit, though possibly a little too far south (and perhaps just too far). As an alternative, there is the site of Yanahara Mine, but although geographically it looks promising, after checking details I’m not truly convinced (it primarily produced copper and wasn’t operational until some time in the 1950s).

(If you’re interested, you can see the distance between an approximate location assigned to Aragane Station and the mine site here, it’s worth toggling on the ‘terrain’ option too.)

After leaving Yashiro Station, the next stop is Shitori Station (no information about location, let me know if you have any ideas).

The last stop before Kongoukaku is Iwato Station. This station functions as a ‘gate’ that controls access to the Shogun’s stronghold (at least from the east) but that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s as close in proximity to Kongoukaku as it first seems, only that the sole way to reach Kongoukaku from that direction by rail involves being permitted to pass through Iwato.

And that brings us to Kongoukaku itself.

There is no confirmed canonical location for Kongoukaku, but Japanese fans consider it to be built near Lake Biwa, like Oda Nobunaga’s Azuchi Castle, while the design of the stronghold itself is modelled on Goryoukaku, with the shape being hexagonal rather than pentagonal (see images above).

This map gives some idea of distance from Aragane Station (somewhere in the east of Shimane prefecture) to Kongoukaku (eastern shore of Lake Biwa). Total distance as the crow flies is around 300km, but the actual journey in the series would of course be longer as their route was not direct.

I placed the marker on the map above at the location of the site of Lake Dainaka (now reclaimed land), as I’ve seen it suggested that this lake is the one Kongoukaku uses as its moat (either that or another of the nearby lakes existing at the time). For a closer look at the size and position of this lake, there’s a useful map here, look for 大中湖. The water of this lake was only 2.7m at its maximum, a shallowness that would allow it to be built on.

The Wadatsu Oohashi (Great Wadatsu Bridge) that Biba mentions in episode 10 is equivalent to the Biwako Oohashi, though if the location is the same, the site of Kongoukaku doesn’t precisely match that of Lake Dainaka as that’s not directly opposite the modern day bridge.

(I was also wondering when Ikoma falls out of the train after being stabbed, whether the water he falls into is Osaka Bay. There are actually a few modern train lines that run along that stretch of coastline before routes veer inland towards Lake Biwa.)

So, that concludes the named locations in the anime series.

...but I’m not finished yet!

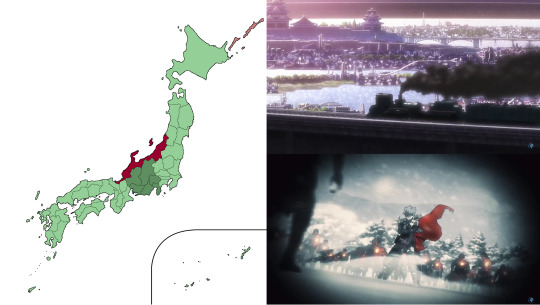

As you know, the game (Koutetsujou no Kabaneri: -Ran- Hajimaru Michiato) is due to be released later this year, and this article gave some information about the setting for the game’s events. With the fall of the Amatori Shogunate that governed the west of the country, the characters continue eastwards, with the game taking place in the region of Hokuriku, along the northwestern coast in Honshu.

(The map shows Hokuriku in red and the Chubu region that it is part of in darker green.)

I think we can expect a couple of things from this; sea and snow. Hokuriku lies right along the Sea of Japan, and has ‘the highest volume of snowfall of any inhabited and arable region in the world’ (source). The home station of the game’s three new characters is 勝木駅 , which Google Translate has as Katsuki Station (it could potentially be Gatsugi Station instead), but although it must be somewhere within this region, I don’t know exactly where.

That brings us to the next installment in the story after the game, a movie with the title of Koutetsujou no Kabaneri: Unato Kessen, set to be released in 2018. So far, very little is known about it other than that it’s set 6 months after the end of the anime series. The teaser video shows some unknown locations and characters but doesn’t give much away, making it hard to speculate about geographical location.

...but how about this?

I don’t think it’s likely that the Koutetsujou will return the way they came just yet (though if the story has a good end, then surely the reopening of Aragane station will require it eventually) so let’s assume they continue in the direction of travel we’ve seen so far.

海門 / Unato is left untranslated in the title (Koutetsujou no Kabaneri: Unato Decisive Battle) so I’ve assumed that’s a place name.

A search for ‘unato’ gives no real results (and nothing that matches the kanji) but if you choose to search instead for the kanji themselves then that gives ‘kaimon,’ a literal translation of which is ‘sea gate’. So, kaimon is a ‘strait’ or a ‘channel’ (check it out on Jisho and have a look at this list of straits of Japan). I obviously don’t know whether this holds any meaning for what we’re going to see in the movie, but what if it did? I’ve often wondered where the kabane outbreak first began in Hi-no-Moto, and I’m quite partial to the idea that it arrived in Kyushu and spread from there. The eastern region of Hi-no-Moto apparently has better technology (it’s the source of the blueprint for Ikoma’s mechanical arm) and I wonder whether that’s partly because the people there had longer to develop such things before the kabane reached them, and perhaps continued trade with other countries for longer (while the fearful and soon to be kabane-infested west, under the rule of the Shogun, would undoubtedly have closed the ports and focused solely on the building of walled stations to hide inside rather than pursue the means with which to fight the kabane, whether that be technological advancement or trade / info from abroad).

And it made me wonder about the furthest end of the country from Kyushu, the island of Hokkaido. Hokkaido is separated from Honshu by the Tsugaru Strait, which is 19.5km at its narrowest point.

...what if the people of Hokkaido were able to prevent the kabane from crossing the strait? The distance between may be enough (it was found to be a zoogeographical boundary). And if not that, what if they have some other reason for refusing to allow access to those trying to cross it? (I mean, you can go wild with speculation here... I wonder whether foreign countries have had more success in blocking or exterminating the kabane or even developing medicine or a way to control / use the kabane... It’d be kind of ironic if, as well as the kabane themselves, Ikoma and co. have to deal with an invading or occupying force who want the land for themselves.)

(...the only glimpse of water in the Unato Kessen teaser)

I could certainly see there being some kind of unique situation in Hokkaido that the main characters aren’t yet aware about, thanks to both its own geography and the Shogun’s attitude towards the sharing of information. Either way, I hope the continuation of the Koutetsujou’s journey will lead to some answers and hopefully a cure.

#kabaneri of the iron fortress#koutetsujou no kabaneri#long post#i mean seriously long post#everything from confirmed canon to wild guesswork#there's not much support for the unato kessen theory#but the geographical progression seems to fit#let me know what you think!

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Live Door] Put Pressure to the Side! Sota Hanamura challenges the stage!

Da-iCE’s Sota Hanamura’s ultimate weapon is being a vocal with overwhelming singing skill. After succeeding at the group’s Budokan live, in the spring he will challenge starring in the stage play “Chiruran Shinsengumi Requiem”. During his training lesson, he showed a smile, saying, “I am happy even to have painful experiences,” and shows no inclination to negative words. The harsh circumstances and heavy pressure turn into positive with the gentleness of his imagination. One by one, he responds to our questions with unexpected answers. What is going on inside the head of Hanamura-san?

The confidence of Shinsengumi Hijikata Toshizo is something they have in common!?

- The stage play originated from popular manga “Chiruran Shinsengumi” and is an action stage depicting the heroes of the strongest samurai group, the Shinsengumi, at the end of the Bakumatsu period. Expectations are high because Da -iCE ’s Sota Hanamura (role Hijikata Toshizo) and Toru Iwaoka (role Okita Souji) are starring together.

Because we did not know we’d be starring together, we were jumping around when we heard the news! (Laughs) Because there are many people who have performed in plays before surrounding us, there is more pressure to do our best so as not to drop the quality.

- I think that it will be a new challenge, completely different from your work as a vocalist, but have you prepared anything special to transition to the stage?

After having read the original work, I started investigating the person I was playing, such as why the original Hijikata Toshizo was the one who was called “the deputy head demon”

- Hijikata Toshizo in this stage is a hero who is growing through battle while aiming to be “the strongest” in Kyoto at the end of the Edo era.

Hijikata is confident at the beginning, fighting to believe that “I am strong” and “I am right”, and growing up with the surrounding encouragement, he becomes a really strong man. This story is about his growth.

- Is there any place you think that you are similar Hijikata Toshizo?

We’re similar! When I was 18 years old, I was convinced that “I can become the best singer in Japan in my teens” (laughs). But when I came out to Tokyo and attended lessons and started having lives with Da -iCE, I noticed, “I’m just one fish in a pond." Even now I’m confident, but unlike the old "overestimation”, I am planning to see my ability accurately. I think that growth is also a huge part of me

–I see. So, when do you think Hijikata is cool?

Aside from his swordsmanship, the place where he learns to trust himself to the end is cool, isn’t it? Because I think that it is very important that I believe in myself, apart from just good singing. I think that continuing to have confidence in anything is a talent.

- The stage lessons have begun, so how is trying out swordsmanship?

It is really hard. There are also a lot of scenes involving sword fighting, and I have only practiced the first half yet, but it is exhausting (laughs). Already … it feels like I’m about to die. Ha ha ha!

- You have a big smile but you must feel a little bitter (laughs).

Still, I’m a certain type. Rather than thinking “Wow, it’s not enough! I have to do it more!”, I would think “I have to know my limits”

- It seems tough to balance your practice with Da-iCE.

While practicing, I also had recording and choreography practice, but my abdominal muscle pain was so bad that it was hard to sing. I was trying to hold my breath, and it looked silly. Even when I tried to make my voice resonate, it was just “It hurts, it hurts, it hurts!”! (Laughs).

- Recording while in pain. It is not something you can easily experience.

It was a shock to me to witness how muscle soreness could make my singing less clear. But I was still content to do it.

- How positive! So what is the most enjoyable part of practice?

It is a lot of fun to interact with the performers, isn’t it? Even when you say the same line, it is slightly different each time. The response of your body and voice at that time will change depending on the line. I want to be able to express myself in various ways …. and every time I work, I feel the power of professionals. I think I surely grow each time during rehearsal and I have to take it to the highest point

- I am looking forward to it. What is it like starring together with Toru Iwaoka?

He is the kindest and the most innocent among my members. It’s easy to be with him because he understands me well. So practice is fun every time!

- It is encouraging that a member is nearby.

I think so, but I think that the pressure is also heavier. I am thankful to have someone like family with me, and since I can share anything including tough things with him, I really appreciate it.

Rather than dying without regrets, I want to regret dying!

- Although the word "pressure” has came out several times, do you easily feel pressure and tension?

It is very easy to feel! When singing live, it’s hard to get into the feelings without being nervous, so I feel as if I can’t sing as well if I don’t have those feelings. When recording, I sing a different way than I do during lives, since I value the importance of ease of listening. So if I do not feeling any tension during the live, it’s too similar to the recording. So, I’d like to be a little nervous all the time during a live event.

- For Hanamura-san, pressure is not bad, it’s also a friend.

Well, of course feeling pressure isn’t easy. After all, it can be a painful thing. Of course, there are days when I am feeling too much pressure and and feel useless, and that imbalance makes me anxious. It comes down to whether I can turn it in a good direction, and make it fun for myself.

- I think that mental attitude is a very wonderful way of thinking.

I’m aware I have limited time, so I want to become a human being who can use it well.

- In the manga “Chiruran Shinsengumi Requiem”, the emotions of a man are depicted beautifully, but what kind of image do you have about masculinity?

About the sense of being a man, it’s something I’ve thought of for a long time. It’s a bit embarrassing to say … (laughs). I think that there are many people who often say “I want to live a life with no regrets when I die,” but I would like to regret it when I die.

- Want to regret …?

I want to die thinking that “I want to live more” and “I wanted to do more” and “I wanted something better.” I want to live more. If you are satisfied, isn’t it a waste? If you think "Oh, alright,” then everything really ends there. I want to die with a desire and greed for living.

- That idea is interesting. When it comes to your work, are you usually satisfied, or do you reflect a lot after?

I will reflect a lot when I see my own videos. Perhaps I’ve seen the film of the Budokan live probably about 20 times. However, if I find five bad places, I try to to find ten good places. It is important to destroy those bad places, but it’s more important to improve upon the good places.

- Doing that, you analyze yourself well.

After all, you do not know until you see the whole picture. “If this song was good” then “Let’s increase it even more here” or “Let’s add more places to it like this”. If there is a place where I think “It was overkill here for a moment”, I should draw back a little..

Dreams are goals that you one day pass through …

- What character do you think you have– what kind of person are you?

I am confident and like myself. I like myself when I am singing, myself when I am dancing, and when I do something I like, I like shining brightly. So, basically, I think that the word confident is a match.

- It really overlaps with Hijikata Toshizo. When did you aim forbecoming a vocalist?

I began to like singing since I was little, but when I was about 15 years old, I started talking about it sincerely. For the first time I told everyone around me the words “I want to become a singer”.

- Were there any challenges?

When choosing my career in junior high school, it was so important to me that I didn’t want to study anything else.

- And in 2011, you joined Da -iCE at the age of 20 and had your major debut in 2014. In January of this year, you also had a one-man live at the Budokan. You are making dreams come true one after another.

When I was fifteen, the major debut was a dream, but when I debuted it became a passing point. Dreams change to goals, and the goal changes to a passing point. The same was the case with the Budokan, which used to be a dream before, so when I actually went to the Budokan, it did not feel like “My dream came true!” because it had become a goal I’d passed, and we were heading towards the next dream.

- Please tell me the next dream.

Someday I absolutely want to stand at the Tokyo Dome. That is a really big dream, because it took our sempai AAA over ten years, so I think that it will also take time to make it. And at the moment when I stand at the dome, if I can see that scene … I guess that I’ve made it an artist, right??

What do you think the next step would be after the dome?

I cannot imagine. That’s why I wanted to stand in that position I cannot imagine. What’s the next point up from the dome and what is left for the artist and what kind of ambition comes after? It is interesting, isn’t it? It would be fun to find out!

-The members of Da-iCE aim for such a dream together. For Hanamura-san, who are the members?

Well, I’m their business associate. …… putting it lightly, haha. (laughs). As I expected, they’ve become my family, and they feel like brothers now, don’t they? There are parts that you don’t want your brothers to interfere with, and there are parts that you want your brothers to understand. It is close to such a feeling. We absolutely can’t be separated!

I’m doing stand up comedy on radio programs by myself (laughs)

- I think you must be busy these day, but how do you spend the day off?

I do not go home at all, or I go to a dance lesson. I like dance lessons. I’m really into dancing now!

–Dance…? Da-iCE has been doing that since formation, but have you been particularly into it?

Yes Yes! When I am addicted, it is all consuming. Since all my senses are involved in it, when there is a lesson to go to, it’s better if I go to it. That’s why it’s so much fun. The thing that I want to do the most now is trying being a back up dancer to someone!

- Hanamura-san as a back-up dancer! (laughs).

No no no. If it’s impossible, I would be ashamed, but I want to do it (laughs). Of course songs are the best, but I’d like to try expressing myself with dance alone. I can express myself with songs, but I’d like to express “I feel like this now” just by dancing.

- Because you always sing, you must feel a strong motivation to try doing it

I agree. That’s why dance lessons relax me. I have no friends either.

- Now, we know that isn’t true … (laughs).

Out of all my friends, there is only one in Tokyo. I am lonely, recently. That’s why I have a feeling of needing to talk, watch comedy programs that I have recorded at home. I’m listening to a radio talk program while I’m on the move, and I keep making responses to it when I’m on my own (laughs).

- You’re being a stand up comedy man by yourself (laughs). Surprisingly, Hanamura-san’s lonely face is ….

I will go to movies by myself. I do not want to talk during the film. I am someone who understands the contents of the movie without needing to talk about it. I can understand the development, but when someone asks me “What was the meaning of that?” I will want to explain, during which the movie will proceed to the next scene ….

–(Laughs).

After all, going by yourself is comfortable (laugh).

- So, at the end …. finally, “One word to those who come to see the stage”, (laughs). Tell us your enthusiasm for the stage!

I am practicing now (* interview was done in early March), with the staff, director, performers and everyone, so that I can create the best stage together with them. I hope you will be satisfied if you come. I will make it “a time you will not regret”!

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flame in the Mist (Renée Ahdieh)

5 stars

“Mariko has always known that being a woman means she’s not in control of her own fate. But Mariko is the daughter of a prominent samurai and a cunning alchemist in her own right, and she refuses to be ignored. When she is ambushed by a group of bandits known as the Black Clan enroute to a political marriage to Minamoto Raiden – the emperor’s son – Mariko realises she has two choices: she can wait to be rescued… or she can take matters into her own hands, hunt down the clan and find the person who wants her dead.

Disguising herself as a peasant boy, Mariko infiltrates the Black Clan’s hideout and befriends their leader, the rebel ronin Ranmaru, and his second-in-command, Okami. Ranmaru and Okami warm to Mariko, impressed by her intellect and ingenuity. But as Mariko gets closer to the Black Clan, she uncovers a dark history of secrets that will force her to question everything she’s ever known.”

So, ‘Flame in the Mist’ had been one of my most anticipated reads of this year ever since it was announced. That’s a lot to live up to and I was both excited and nervous when I received an ARC copy, wondering whether it could live up to my expectations.

Thankfully, I adored this book…

Characters

Mariko, our protagonist is more interested in inventing things, whether they be objects that explode or those more practical, than being a Daimyō‘s daughter. The funny thing is that she’s actually kind of useless at first in the society of the Black Clan. She can’t cook, can’t cut fire wood, has pretty terrible upper body strength, and manages to make an enemy of pretty much everyone she meets. Maybe sometimes overestimating her own cunning and making chaos of situations, she’s a nightmare and I loved her.

Her twin brother, Kenshin, also known as the Dragon of Kai, is already a greatly revered Samurai warrior. He is equally as fierce as his sister and deeply protective of her, sometimes struggling with tenents of Bushidō relating to self control. One thing I couldn’t work out during the book is whether Kenshin actually has some magic of his own, mages are rare in the book but destruction seems to come to him far too easily. Fear for his sister, the complex political wranglings of the Imperial Court and having to lead a band of Samurai almost twice his age seem to push Kenshin to the brink and I’m pretty curious and worried to see how the next book works out for him.

Okami is, unsurprisingly, one of my favourite characters. Seemingly a little lazy and unkempt, the actually rather dangerous and dark-magic-wielding second in command of the Black Clan has some of the best lines in the book:

‘My life has been filled with death and lies and loose women…I regret everything else.’

Like, what am I supposed to do with that? Witty and a dashing facial scar? He almost comes with a sticker on his head saying ‘this one is going to be your favourite character‘. I also enjoyed just how infuriating he found Mariko in her guise as a young man, seeing her as little more than a burden and a risk to the Black Clan.

Ah, hate to love, isn’t it glorious?

Story

Often touted as a combination of the Chinese story of Mulan and the Japanese tales of the 47 Rōnin, I will say that, plotwise, it takes a lot more from the latter. It is a Mulan retelling to the extent that Mariko disguises herself as a man and in some aspects of the romance, but the actual story is much closer to the Japanese stories of the rōnin, leaderless samurai, seeking revenge for the death of their daimyō.

It’s a slow story, but I’m glad that was the case. Ahdieh’s descriptions and character building take time and space, she has a wonderful way with words that often made me want to read the story aloud. Likewise, she takes time to allow character relationships to blossom, often leaving the exact feelings of characters towards one another as confused or amorphous, which, let’s be honest, is often exactly how close bonds form.

One thing I have, unfortunately, found over my years of reading is that it’s really difficult to find fantasy set in a Feudal Japanese setting that doesn’t make my eyes roll out of my head. Between painful tropes, fetishization and a basic misunderstanding of Japanese cultural identity, finding good books has really been luck of the draw. This book was a breath of fresh air in that respect.

‘Flame in the Mist‘ is a sensitive portrayal of a fantasy feudal Japan. The story could not be told without its setting, it’s much more than scenic window-dressing, with Ahdieh addressing the political and cultural implications of Bushidō, ‘the way of the warrior’, as one of the central pillarstones of the story. It explores the duality of a fantasy Edo period and shogunate culture, where warriors such as the Samurai lived by the laws of Bushidō, including benevolence, integrity, loyalty and honour, but the structure of society enforced strict hierarchies with little or no social mobility. Ahdieh does a good job of explaining some more unfamiliar concepts in text, especially the omnipresent Bushidō code and the political importance of Geiko and the tea ceremonies.

It’s a story about revolution and social change, which, let’s be honest, is incredibly relevant right now. It asks questions about the status quo, about why it should be allowed to persist, whether it is even ethical for it continue in the way it is. Okami, for example, is vocally critical of the way of the Samurai and what he sees as unquestioning loyalty to an underserving upper echelon of society. I’m really excited to see how Ahdieh tackles some of those issues in the next book!

Note

I have seen one or two people comment that the use of Japanese in text is confusing or distracting for them. I would say that a) there’s a glossary at the back, b) the words are pretty easy to understand from context and cultural osmosis, and c) you’d probably just accept it if it was a fantasy novel. If you come from a martial arts background like me (Kendo), then you will probably have no problem with the words at all.

Conclusion

It was amazing, I read it too fast and now I’m going to have to wait painfully for book two. If you’re looking for a YA fantasy set in feudal Japan then this is the book for you; it’s beautifully written, sensitive to culture, has a perfect romance and is just, genuinely, everything that I wanted it to be.

Many thanks to Hodder and Stoughton for a copy in return for an honest review.

Originally posted at Moon Magister Reviews.

#proteinreviews#flame in the mist#renee ahdieh#renée ahdieh#hattori mariko#okami#hattori kenshin#book blogger#book reviewer#new books#pre-release#bookblr#young adult#ya#fantasy#japan#booklr#goodreads#book blog

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

Yes, we are actually closing in on the Kickstarter for Justin Achilli’s casual vampire card game, Prince’s Gambit. This is the first time Onyx Path will be offering a card game on Kickstarter, so it is a very new thing for us. And as we have heard it said: Anything done for the first time unleashes a demon!

Hopefully, in this case, we’re unleashing a demonic whirlwind of fun. But, I guess we’ll see. Certainly the playtesters who have had several iterations of the game to play through have seemed to really like it – especially this latest version!

As I always am before a Kickstarter, I’m nervous as to whether we’ve presented the game right and enough backers will get engaged with the project. So, I’m still fine-tuning the writing and presentation. It’s not a particularly complicated Kickstarter set-up, in fact, it’s our simplest. And the project is not at all expensive to back. In fact, a single deck of cards provides endless gameplay for you and 5-7 friends.

But still, I fret.

Shapeshifter for M20 Book of Secrets by Ken Meyer, Jr

It’s funny, Prince’s Gambit is actually an example of serendipity. I had been at Nashville By Night along with our friends at By Night Studios, and noticed how the live action roleplayers sat in the lobby of the hotel, or out on the patio, and played non-World of Darkness card games between LARP sessions.

Which made me wonder if we could create a Vampire; the Masquerade card game that would be simpler than the Vampire: the Eternal Struggle collectable card game (or even Magic: the Gathering) so that players could jump in and play relatively quickly. I threw some thoughts around with the gang at the con, and then filed the idea away under “things we should try”.

Fast forward to almost a year later, and during one of our usual conversations, Justin Achilli mentions that he has been working on a rough idea, really a prototype at that point, of a casual vampire card game. And would Onyx Path be interested in publishing it for Vampire: the Masquerade?

Lore of the Bloodlines Salubri by Mark Kelly

Ding, ding, ding, ding!

A “casual” card game. The very word to describe the sort of game I was thinking about in Nashville. And designed by my old friend and long, long-time Vampire developer Justin Achilli.

Yes, please!

So, hopefully, you’ll be able to see it yourself on Kickstarter next week. Not only do we have a great opening Kickstarter video featuring Justin describing the project, but we have an example of play video that is a compelling Prince’s Gambit session featuring representatives of the Clans (some of whom you might know from the Atlanta gaming crowd).

We’ll have the link to that, and the rules, in the Kickstarter, and also on our YouTube channel for ya’ll to check out.

Pugmire illustration by Pat Loboyko

Finally, I used to post a lot more about the conversations Eddy and I have in the first meeting of the day, the actual 12 noon Monday Lunch Meeting that is truly descended from the Monday lunch meetings we had at White Wolf from the time I started.

Subba-Wubba? Yummmmm!

Mostly, that’s because most of what Eddy and I have been talking about for months are Pugmire, Mau, or other projects that we really can’t reveal, or the intricacies of the care and management of licensing partners.

But today, we actually sat back and talked a little more of the working theories based on media that we’ve enjoyed putting forth over the years. Today, I just happened to mention conspiracy theorists, like you do, and Eddy was off on a theory of how our human brain is so built for pattern recognition that we have no choice but to look for patterns in everything.

Which means that we have no choice but to detect conspiracy theories, because we have to try and make disparate items fit together. Which, led us to wondering if Science, or at least scientific proofs, came about as a deep need to prove or debunk the general human impulse to jam things together crazily.

Naturally, this led to a discussion of Edition Wars, and whether they happen because our brains link the pattern (the gameplay, rules, art, well everything) of our preferred edition to our view of what is “correct” in the patterns of reality, and that gives us pleasure. Change, then, breaks that pattern and ruins our pleasure.

If any of that makes sense, or is interesting, to you, then you clearly suffer from the same issues as Eddy and myself. Welcome to the party, pal!

As a reward for sitting through our meandering, here’s a cute knitted doll of Princess Yosha from Pugmire, and a link to the site where you can get yourself a copy: http://ift.tt/2lQo87j

BLURBS!

KICKSTARTER!

I’m finishing up the KS pages for the Prince’s Gambit casual card game this week. Things look good, and we are all for starting the KS in March so long as the process of pulling the KS together cooperates. If so, then Monarchies of Mau KS would be next, after Gambit.

ON SALE!

DTRPG’s GM’s Day Sale starts March 2nd and runs for about a week! Check out all sorts of sales and bargains on Onyx Path and White Wolf PDFs at DriveThruRPG.com!

Looking for our Deluxe or Prestige Edition books? Here’s the link to the press release we put out about how Onyx Path is now selling through Indie Press Revolution: http://ift.tt/1ZlTT6z

You can now order wave 2 of our Deluxe and Prestige print overrun books, including Deluxe Mage 20th Anniversary, and Deluxe V20 Dark Ages!

The Secrets of the Covenants for Vampire: the Requiem 2nd REVEALED this Wednesday on DTRPG! Physical copy PoD version coming to DTRPG: http://ift.tt/2gbQjus

Vampires gather under many banners. But five have endured the tumult of Western history better than any other. The Carthian Movement. The Circle of the Crone. The Invictus. The Lancea et Sanctum. The Ordo Dracul. Each has its fierce devotees, its jealous rivals, and its relentless enemies. Now,for the first time, the covenants speak for themselves.

This book includes:

A variety of stories from each of the covenants, all told in their own words.

Never-before revealed secrets, like the fate of the Prince of New Orleans.

New blood sorcery, oaths, and other hidden powers of the covenants.

From the massive Chronicles of Darkness: Dark Eras main book, we have pulled this single chapter, Dark Eras: Fallen Blossoms (Hunter 1640-1660 Japan). Japan is moving into the Edo Period. New laws and new ways of thinking wash over the land, and with a new order come new threats to humanity. Take a look at the Vigil in a time where samurai transition from warlords to bureaucrats, Japan massively and lethally rejects outside influence, and when Edo rapidly grows into a world power.

Continuing our individual Dark Eras chapters, we offer you Dark Eras: Fallen Blossoms on in PDF and physical copy PoD versions on DTRPG! http://ift.tt/2mfc1F1

From the massive Chronicles of Darkness: Dark Eras main book, we have pulled this single chapter, Dark Eras: Doubting Souls (Hunter 1690-1695 Salem). Immigrants and tribes struggled to co-exist on the Eastern Seaboard in the ever-expanding Colonies. Violent clashes, supernatural beliefs, and demonic influences spelled disaster for Salem Village and its surrounding towns, while others fought werewolves and vampires on the frontier. With so much at risk, only god-fearing men and women were deemed innocent — and those were few indeed.

Available in PDF and physical copy PoD versions on DTRPG: http://ift.tt/2kKOrfm

From the massive Chronicles of Darkness: Dark Eras main book, we have pulled this single chapter, Dark Eras: The Bowery Dogs (Werewolf 1969-1979 NYC). New York City in the 1970s. Crime. Drugs. Gang violence. Vast economic disparity. And werewolves. It’s a lean, ugly time to be alive, and the lone wolf doesn’t stand a chance out there. In the end, all you really have is family.

Available in PDF and physical copy PoD versions on DTRPG: http://ift.tt/2lM0Tzv

The Locker is open; the Chronicles of Darkness: Hurt Locker, that is! PDF and physical copy PoDs are now available on DTRPG! http://ift.tt/2gbM9me

Hurt Locker features:

Treatment of violence in the Chronicles of Darkness. Lasting trauma, scene framing, and other tools for making your stories hurt.

Many new player options, including Merits, supernatural knacks, and even new character types like psychic vampires and sleeper cell soldiers.

Expanded equipment and equipment rules.

Hurt Locker requires the Chronicles of Darkness Rulebook or any other standalone Chronicles of Darkness rulebook such as Vampire: The Requiem, Werewolf: The Forsaken, or Beast: The Primordial to use.

Both the Beast: the Primordial http://ift.tt/2fEMsdO & Promethean: the Created 2nd Edition Condition Cards http://ift.tt/2iSein1 are now on sale on DTRPG in PDF and physical card PoD versions! Great for keeping track of the Conditions that are on your characters!

From the massive Chronicles of Darkness: Dark Eras main book, we have pulled this single chapter, Dark Eras: Ruins of Empire (Mummy 1893-1924). Perhaps the quintessential era of the mummy in the minds of Westerners, this period saw the decline of the two greatest empires of the age: British and Ottoman. Walk with the Arisen as they bear witness to the death of the Victorian age, to pivotal mortal discoveries in Egypt, and to the horrors of the Great War.

Available in PDF and physical copy PoD versions on DTRPG. http://ift.tt/2k0XDhX

From the massive Chronicles of Darkness: Dark Eras main book, we have pulled this single chapter, Dark Eras: The Sundered World (Werewolf and Mage 5500-5000 BCE). At the birth of civilization, in the shadow of the Fall, the Awakened stand as champions and protectors of the agricultural villages spread across the Balkans. In a world without a Gauntlet, where Shadow and flesh mingle, the steady taming of the world by humanity conflicts with the half-spirit children of Father Wolf.

Available in PDF and physical copy PoD versions on DTRPG. http://ift.tt/2k16mRj

Night Horrors: Conquering Heroes for Beast: the Primordial is available now as an Advance PDF: http://ift.tt/2j7p7lO

This book includes:

An in-depth look at how Heroes hunt and what makes a Hero, with eleven new Heroes to drop into any chronicle.

A brief look at why Beasts may antagonize one another, with seven new Beasts to drop into any chronicle.

Rules for Insatiables, ancient creatures born of the Primordial Dream intent on hunting down Beasts to fill a hunger without end, featuring six examples ready to use in any chronicle.

The PDF and physical book PoD versions of Reap the Whirlwind, the Vampire: the Requiem 2nd Edition Jumpstart swirls into being on DTRPG! http://ift.tt/2i1WPpD

You are a vampire, a junkie. Every night, you beg and you borrow and you steal just a little more life, just a few more sweet moments. But there’s a guy at the top. The Prince. He’s got everything. The money, the secrets, the blood.

Tonight, you’re going to take it from him. Tomorrow, there’ll be hell to pay.

This updated edition of Reap the Whirlwind features revisions to match the core rulebook for Vampire: the Requiem 2nd Edition. Text edits and rules clarifications have also been updated.

Reap the Whirlwind Revised includes:

Rules for creating and playing vampires in the Chronicles of Darkness

The first two levels of every clan Discipline, the dark powers of the dead

A complete adventure by noted horror author Chuck Wendig

This new revised Reap the Whirlwind Revised includes an updated booklet, 7 condition cards, and the interactive Vampire: the Requiem 2nd Edition character sheet.

Open the V20 Dark Ages: Tome of Secrets now on DTRPG! Both PDF and physical book PoD versions are now available! http://ift.tt/2i1XOXd

The Tome of Secrets is a treatment of numerous topics about Cainites and stranger things in the Dark Medieval World. It’s about peeling back the curtain, and digging a little deeper. Inside, you’ll find:

• Expanded treatment of Assamite Sorcery, Koldunic Sorcery, Necromancy, and Setite Sorcery

• A look at Cainite knightly orders, faith movements, and even human witchcraft

• Letters and diaries from all over the Dark Medieval World

CONVENTIONS!

Impish Ian Watson will be on a Q&A panel at CAiNE http://ift.tt/2m5ejGC being hosted in Hamilton Ontario March 16 to 19th 2017!

Discussing GenCon plans. August 17th – 20th, Indianapolis. Every chance the booth will actually be 20? x 30? this year that we’ll be sharing with friends. We’re looking at new displays this year, like a back drop and magazine racks for the brochure(s).

In November, we’ll be at Game Hole Con in Madison, WI. More news as we have it, and here’s their website: http://ift.tt/RIm6qP

And now, the new project status updates!

DEVELOPMENT STATUS FROM ROLLICKING ROSE (projects in bold have changed status since last week):

First Draft (The first phase of a project that is about the work being done by writers, not dev prep)

Exalted 3rd Novel by Matt Forbeck (Exalted 3rd Edition)

Trinity Continuum: Aeon Rulebook (The Trinity Continuum)

M20 Gods and Monsters (Mage: the Ascension 20th Anniversary Edition)

M20 Book of the Fallen (Mage: the Ascension 20th Anniversary Edition)

Ex Novel 2 (Aaron Rosenberg) (Exalted 3rd Edition)

C20 Novel (Jackie Cassada) (Changeling: the Dreaming 20th Anniversary Edition)

Pugmire Fiction Anthology (Pugmire)

Monarchies of Mau Early Access (Pugmire)

Hunter: the Vigil 2e core (Hunter: the Vigil 2nd Edition)

Redlines

Scion: Origins (Scion 2nd Edition)

Scion: Hero (Scion 2nd Edition)

Kithbook Boggans (Changeling: the Dreaming 20th Anniversary Edition)

VtR Half-Damned (Vampire: the Requiem 2nd Edition)

WoD Ghost Hunters (World of Darkness)

Trinity Continuum Core Rulebook (The Trinity Continuum)

Pugmire Pan’s Guide for New Pioneers (Pugmire)

Second Draft

The Realm (Exalted 3rd Edition)

Dragon-Blooded (Exalted 3rd Edition)

BtP Beast Player’s Guide (Beast: the Primordial)

V20 Dark Ages Jumpstart (Vampire: the Masquerade 20th Anniversary Edition)

GtS Geist 2e core (Geist: the Sin-Eaters Second Edition)

CtD C20 Jumpstart (Changeling: the Dreaming 20th Anniversary Edition)

Development

W20 Changing Ways (Werewolf: the Apocalypse 20th Anniversary Edition)

Signs of Sorcery (Mage: the Awakening Second Edition)

SL Ring of Spiragos (Pathfinder – Scarred Lands 2nd Edition)

Ring of Spiragos (5e – Scarred Lands 2nd Edition)

SL Dagger of Spiragos (Pathfinder – Scarred Lands 2nd Edition)

Dagger of Spiragos (5e– Scarred Lands 2nd Edition)

Arms of the Chosen (Exalted 3rd Edition)

Changeling: the Lost 2nd Edition, featuring the Huntsmen Chronicle (Changeling: the Lost 2nd Edition)

BtP Building a Legend (Beast: the Primordial)

Book of Freeholds (Changeling: the Dreaming 20th Anniversary Edition)

Editing:

W20 Song of Unmaking novel (Bridges) (Werewolf: the Apocalypse 20th Anniversary Edition)

CtD C20 Anthology (Changeling: the Dreaming 20th Anniversary Edition)

Wraith: the Oblivion 20th Anniversary Edition

M20 Cookbook (Mage: the Ascension 20th Anniversary Edition)

Post-Editing Development:

CtL fiction anthology (Changeling: the Lost 2nd Edition)

VtR A Thousand Years of Night (Vampire: the Requiem 2nd Edition)

Indexing:

Pugmire

ART DIRECTION FROM MIRTHFUL MIKE:

In Art Direction

Beckett’s Jyhad Diary – new stuff AD’d

W20 Pentex Employee Indoctrination Handbook

V20 Dark Ages Companion – Finals in from McEvoy, Gaydos, and Leblanc… still have three artists who owe me.

Dagger of Spiragos – Finals in progress… and maps.

VTR: Thousand Years of Night

Cavaliers of Mars – AD’d

Monarchies of Mau Early Access – Prepping notes for artists

BtP Building a Legend – Contracting…

April Fool’s thing – I will get Leblanc on it

Marketing Stuff

In Layout

Prince’s Gambit – Final tweaks to preview cards and some design stuff on the tuckboxes.

C20 – With Aileen

M20 Book of Secrets – Layout should start rolling this week.

Dark Eras Companion – Adding in corrections… and trying to wrap up artist shenanigans.

Proofing

EX3 Tomb of Dreams Jumpstart – first proof.

V20 Lore of the Bloodlines

At Press

Ex 3 Screen – Ready to ship, shipping starting this week.

Ex 3 core book – Ready to ship, shipping starting this week, along with map and bookmarks.

Secrets of the Covenants – Going on sale this Wednesday in PDF and PoD versions.

Beckett Screen – Shipped to shipper.

W20 Shattered Dreams – Ready to Ship.