#KnY nerdery

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

What Rank did Michikatsu [Human Kokushibō] Hold as a Samurai?

When we think of a samurai, we often envision a fierce warrior prepared for battle. While this is partly true, we often tend to forget the internal heirarchy among them. Like any military group, samurai had a clear chain of command for smooth operations. However, it's important to note that samurai were a social class rather than a military one.

These "ranks," or more so, distinctions within the samurai were closely tied to hereditary social status, the extent of land ownership, and titles within the clan, rather than personal skills, which could vary depending on the era.

In this discussion, we will concentrate on the Sengoku era, as it is relevant to our topic. I will examine Michikatsu's role based on the available canonical information.

⚠ SPOILERS AHEAD ⚠ | Masterlist

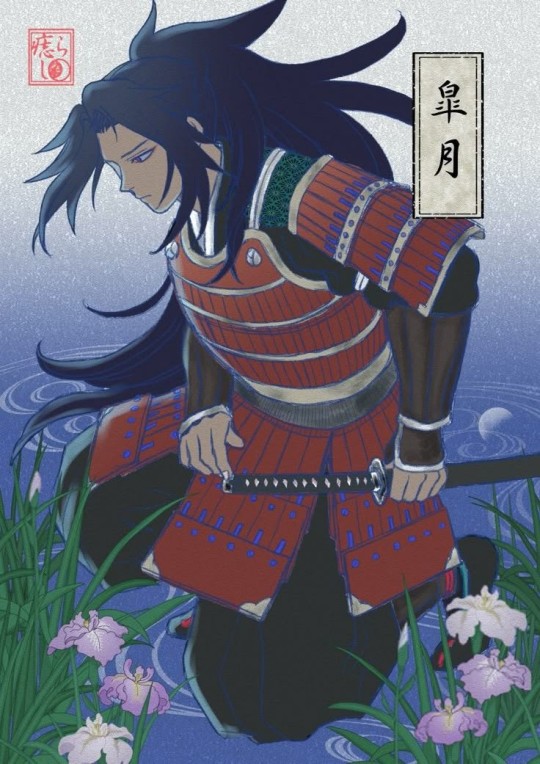

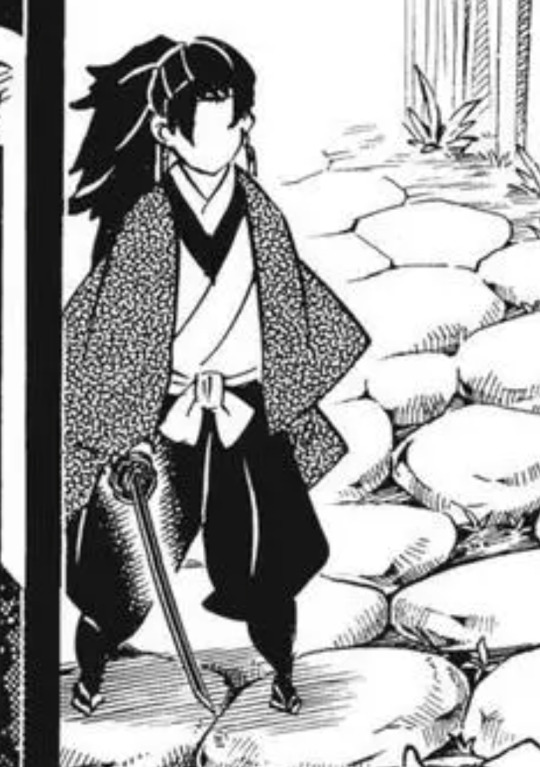

⨳ Where His Father stood

In the image above, Michikatsu talks about his father having a "vassal." A lot could be inferred from this, but it is likely that his father either might be a samurai lord [Sengoku daimyo] or a wealthy, high-ranking samurai who supports smaller samurai.

[Daimyo (大名): military lords who controlled small, unified areas in which all the land either belonged to themselves or was held in fief by their vassals] [Vassals: subordinates who pledged their loyalty and obligations towards powerful lords]

So essentially, he was not just an ordinary samurai but rather a figure of considerable importance. His possession of vassals and land suggests that he must be exercising some form of governance, implying that he is possibly some sort of lord having an independent clan.

As you can see, he seemed to have personal servants:

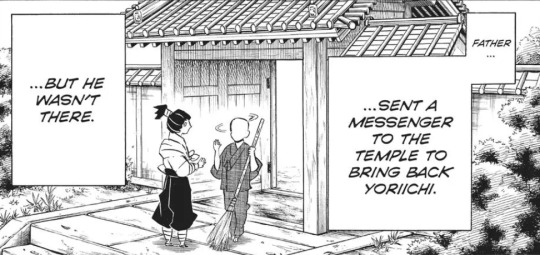

And also personal messengers:

Though it is rather difficult to tell whether he was a powerful lord or not—an actual daimyo who was the direct vassal of the shogun, or just a lesser lord having a smaller land—possibly a heir to the family head or a landowner with a fief.

⨳ Was The Tsugikuni Clan Powerful?

First, let us understand what was going on during that time:

"This was the 'Age of Warring States', when scores of minor daimyo seized power for themselves in their immediate localities and fought each other until, during the mid-16th century, a comparative handful of 'super-daimyo' competed with each other on a grand scale before Japan was finally reunified" [source]

From this, it seems logical to assume that the Tsugikuni clan was a smaller one rather than a grand one—also considering Michikatsu's father's rather obsessive nature and his intense determination on getting better heirs, even to the point of being willing to harm his own family due to superstitious beliefs. Better heirs: more likely the clan gets to thrive and gain power.

Also, if we consider these words from Kokushibou:

Notice how he says this—he doesn't seem to be very surprised to know that his clan's name has died out, which would only solidify the fact that his clan must not be very powerful to begin with. [Considering that many direct descendants of the major clans today still seem to be thriving, with many carrying out their clan names. Muichiro seems to be an exception here]

So now that we know that his clan was likely not a powerful one, we could also assume that his father was a local lord rather than a full on daimyo for obvious reasons. Not only that, but this would also suggest that their clan must be a retainer family—they would be under a much stronger lord—a powerful daimyo, whom they would had to serve.

⨳ MICHIKATSU'S POSIBBLE RANK [DISTINCTION]

Before moving on, I would just like to point out that holding a high-ranking position as a samurai—such as leading troops— was a result of personal achievement rather than mere familial ties. If a family did not meet the necessary standards of talent and capability, their members would be assigned to lesser roles based on who they served.

With that being said, let us now try fitting in Michikatsu into all of this and find out what military rank he should have based on his family background:

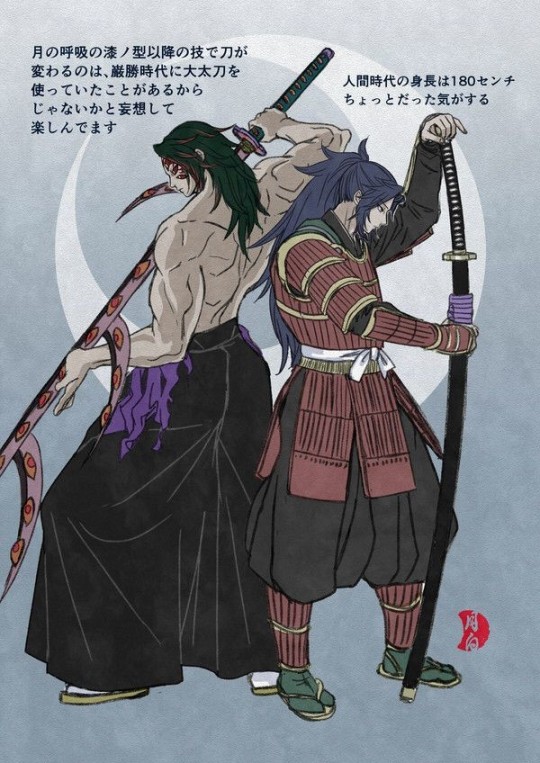

Initailly, I was rather confused and wondered if Michikatsu could be a Hatamoto. They were the highest ranking samurai, considered the most loyal and skilled, who acted as bodyguards towards their lord. Sounds familiar, right? However, there was one piece of canon information that completely debunked this idea:

Samurai usually had to chop off their enemy’s head as proof of their kills; typically that shouldn't be done by the hatamoto, as they typically stayed close to their lords as a last resort instead of fighting on the front lines like the others.

Okay.. so he probably isn't a hatamoto. If his first instinct was to bring the head of Ubuyashiki to Muzan, then it suggests he must have done this before. if that's the case, then he must have ranked lower than a hatamoto, more so in a class where he might have been around collecting heads. After looking into what the manga could offer, I reached two conclusions:

1. He was a Taisho (大将)[general]: These ranked officials were the generals in the Daimyo's army, leading groups of soldiers called kumi. Depending on the troops they commanded, they were either referred to as Samurai-taisho or Ashigaru-taisho. They usually oversaw multiple kumi, each consisting of around 50 to 100 men.

2. He was a Kumigashira (組頭) [captain/platoon commander]: These officers controlled and led a single kumi of troops and were called samurai-kumigashira or ashigaru-kumigashira based on the type of troops in their kumi; which, often consisted upto 15-30 men each.

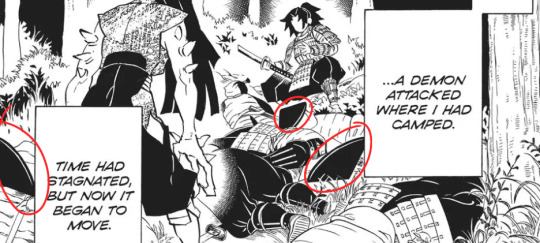

-> By those conical hats (jingasa) those men are wearing, I'm pretty sure they are depicted as Ashigaru foot soldiers. [This explains why he refers to them as his subordinates, as ashigaru were considered lower than samurai.]

Looking at the image, I doubt there are 50-100 men present there, and it seems more likely there are about 15-30. Therefore, we can conclude that he must be an Ashigaru-kumigashira.

Also, when people talk about Ashigaru, they usually think of peasants taken out of their farms. This is a misconception. Even though they were lower in class, ashigaru were generally treated as full on warriors. Not only were they as capable as their samurai counterparts, some were even stronger than them.The men under Michikatsu's command were fully capable and skilled swordsmen.

⨳ Michikatsu's Troops and His Role:

A general overview of the make up of the sengoku era army

—In short, the troops were reorganised in Sonae, which had between 300 to 800 men. Each Sonae included various types of troops. They were split into smaller units called Kumi, based on their weapons. These included archers, gun squads, cavalry, spear squads, and standard bearers.

By looking at these images, I see no one holding weapons, just a few casual swords thrown in here and there, which I find to be very odd..

Perhaps Michikatsu had set up his base further from his soldiers and gathered them up for a speech about the next day's plans just before they went to sleep? This could explain why they were caught off guard by the demon and didn’t have their weapons ready. After all, it’s strange not to have your weapons out when you are being attacked.

Regardless of the situation, his troops should be either a spear unit [Yari-gumi (長柄組)] or an archer unit [Yumi-gumi (弓組)].

These troops Consisted of: 1 samurai commander/katana samurai, 2-4 servants, ~20-30 foot soldiers, 3 labourers, 1 cavalry horse, and 2 packhorses.

Why you ask? This is because, firstly; guns weren't introduced until the mid sengoku period in 1543 [Michikatsu is theorised to be born around 1432] In the cavalry unit, the troops consisted of samurai rather than ashigaru, and bannermen did not engage in battle.

MICHIKATSU'S ROLE: Although there is not much provided anywhere about these commanders, from everything I have gathered: These commanding officers used to lead a unit of ashigaru soldiers. They were ranked below the sodaisho and samurai daisho (commanders) and an ashigaru taisho.

He would be assigned to train them, discipline the foot soldiers, and turn uneducated common men into reliable warriors. He would command and lead them, ensuring everyone followed his commands and maintained order within the ranks, and not disrupt the hierarchy. Hmm that sounds familiar doesn't it?

[I might actually make a detailed post about the military formation with Michikatsu if any of you are interested.]

Final thoughts:

[A/n: Hello everyone! It's been a while since my last post. No, I haven't abandoned my blogs. I just took a short break last week. Now I'm back and eager to share a theory with you all! Which I will be posting more of, both here and on my other blog, @gilded-sunrays. Please feel free to share your insights!]

And if you've made it through all of this, then I thank you wholeheartedly!

#「ᴛʜᴇᴏʀɪᴇꜱ & ᴀɴᴀʟʏꜱɪꜱ」#Kokushibo#Sengoku era#Tsugikuni clan#Michikatsu Tsugikuni#Kny sengoku era#Michikatsu#tsugikuni michikatsu#Kokushibo analysis#Michikatsu analysis#Kny analysis#Kny nerdery#kny reference#kny fandom theories and meta#kokushibou#kokushibo demon slayer#demon slayer kokushibo#demon slayer#kimetsu no yaiba#kny kokushibo

262 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wind up doodle because I'm in an Uzui Tengen mood this morning and his whole self-introduction scene remains the funniest of all the Hashira.

Sure, "umai" or stabbing some kid's demon sister is iconic, but the Uzui/Kamaboko intro just builds and builds and builds with their special brands of weird personality traits increasing one another's idiocy. In that game of toss-the-brain-cell no one even tried to take it from Zenitsu.

(Omake below the cut)

As I was drawing and giggling about Tengen's self-introduction and how comfortable he is with randomness and bravado (I'll bet he never bothered calling himself a god until that moment because it just popped into his head), I got to drawing his hands and I was like, "This looks sort of like the 'sword' hand pose of statues of the Buddha Amida (the one whose name Himejima is always invoking) in lecturing mode, but also that's not quite it and I doubt Uzui has much actual understanding of religion" and I wanted to embarrass him by having someone call him out on it, because embarrassing Uzui is a hard thing to do. His self-confidence is so powerful that he can deflect it (but also his self-understanding of his limits is so keen that he can face reality with more strength than, say, someone like Inosuke can).

And before you say "but he called himself a kami, not a Buddha," yes! And this takes place decades after the Meiji government forcibly made them separate! But as far as most common folks were concerned, the deities and religiosity in general was still pretty blended.

#uzui tengen#my art#my nice art#kny fandom theories and meta#kny nerdery#kinda#mostly just fangirl rambling that has some nerdery basis#tengen-samaaaa

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

How fast is Yoriichi Tsugikuni? || Calculating his minimum speed

Yoriichi Tsugikuni is regarded as the most powerful character in Demon Slayer, with him being able to rival and overpower the demon king himself, Muzan Kibutsuji. He is renowned for his exceptional speed and agility; however, the true extent of his speed remains uncertain due to the lack of comparable benchmarks.

Therefore, today I will make an effort to clarify some of the confusion by applying some of my knowledge to estimate the average speed of this character. From here, you are free to interpret and use this information as you see fit.

NOTE: SIGNIFICANT FIGURES UPTO 3 DIGITS AFTER THE DECIMAL POINT

⚠ SPOILER WARNING ⚠

⨳ Muzan's Explosion: Detonation or Deflagration?

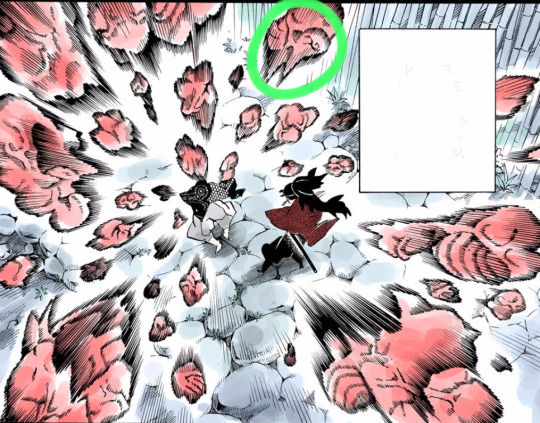

To begin, let us examine this image. If we want to determine Yoriichi's speed, then we obviously have to know the relative speed of some other body that we can compare it with. In this case, we will consider Muzan's explosion. [Not using NLM or COLM as it doesn't consider the huge amount of force being exerted]

In an explosion, an internal impulse (force per unit time) acts in order to propel the parts of a given mass into many fragments in different directions. After the explosion, the individual parts of the system have momentum. Obviously, if a body has momentum, it would mean it has a velocity as well, as momentum (p) ∝ v.

Explosions can be further classified into detonations and delafegations:

[Defragrations: Energy released is in the form of heat like in a flash fire. It requires fuel an external oxidizing agent, rely on the external pressure and are considerably more stable.] [Detonations: Energy is released in the form of high pressure (force). Does not require a fuel and doesn't depend on the external pressure, and involves chemicaly unstable molecules, which instantaneously split that recombine into different products.]

[Defragrations VS Detonations] You can refer to this link for more information. However, to keep this post concise, I will outline a straightforward distinction between the two

⇒ Muzan's explosion is more likely that of a Detonation, rather than a deflagration.

⨳ Muzan's Detonating Speed:

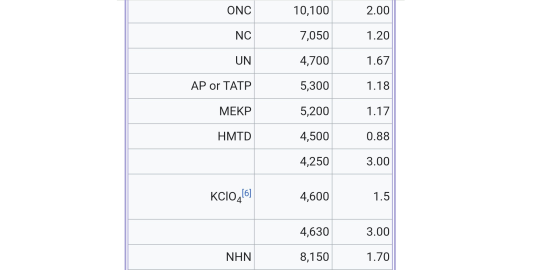

Detonation velocity depends on a number of factors, such as density, it's state, charge diameter and temperature. For solids and liquids, these velocities usually range from 4000 m/s-10300 m/s. Muzan's density is likely similar to that of a human, around 1000 kg/m³ or 1g/cm³. .. Let's compare this density to that of regular explosives:

link here

Although, we can see the closest explosives to Muzan's density are 1.___ ones. However, we can also see even then these velocities aren't propotional to their ascending order of densities, but it does give us some insight.

Though, we cannot determine his charge diameter and temperature [although his flesh appears very red]. Plus, there also seems to be one compound in the given table [ansu] which only has a detonation velocity of a mere 3400m/s. So.. it is very difficult to make assumptions here. So to remain neutral, we will just use the lowest speed value, ie 4000 m/s.

⇒ Hence, we can safely conclude, that muzan likely detonates with the minimum speed of 4000m/s.

⨳ Yoriichi's Attack Range and the Time Needed For Him to Cut All the Peices of Muzan

To evaluate Yoriichi's speed, we will first calculate the total time it would take for him to react and effectively cut all of Muzan's pieces [excluding the 300 pieces, which we will discuss later] before he has the chance to escape.

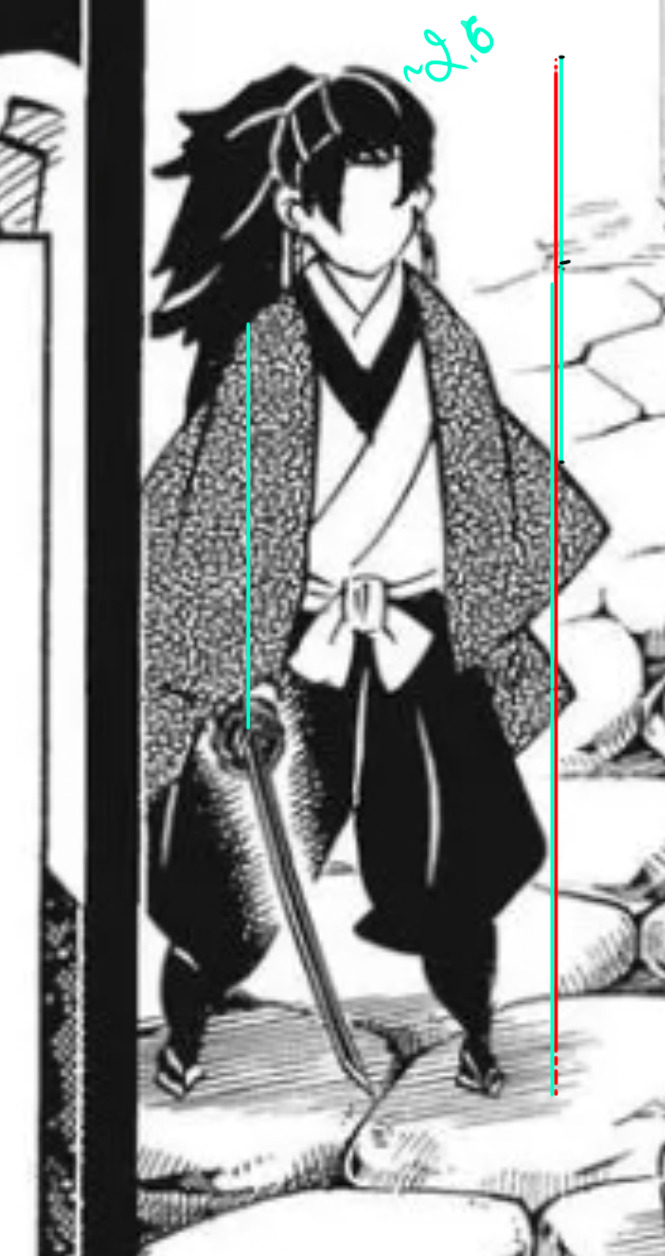

So for that, first, we need to determine Yoriichi's attack range by measuring his arm length. Instead of making an estimation using measurements of an average male arm, I decided to accurately measure this out myself:

We know Yoriichi is approximately 6.3 feet tall, which is about 2.6 times the length of his arms. Based on this, we can conclude his arm to be around 73.07 cm. (190/2.6) + sword length (we'll take the average of 65 cm)

ie = 1.381 m So, the maximum time needed for him to cut down muzan would be: ∴ 1.381 ÷ 4000

⇒ ~0.000345 seconds

⨳ Distance Covered By Yoriichi:

[I think if you know a bit about physics, you might see where I'm headed.] We know that speed = distance/time. We have already determined the time, and now we need to find the distance to calculate the speed. How can we do that? We can begin by figuring out the total distance Yoriichi's arms cover while swinging the sword:

To do this, let's refer to the image above. If we examine it closely, we can see that Yoriichi creates arcs with his sword, forming almost a complete circle

Please excuse my silly drawing, but this is my idea of the sword arc. I imagine it as two-thirds of a circle instead of a semi-circle.

To find the arc length, we will use 2πr × 2/3 Radius: Yoriichi's arms and sword ∴ 2 × 22/7 × 1.381 × 2/3

= 5.786 m is the length of each slash

⨳ How Many Slashes Did Yoriichi Make?

To finalise, we will check how many slashes he made to cut muzan. Clearly, he wasn't making just one slash for each cut, as that would be very impractical. So, let's see how much work he is doing here:

Once again, in the image above, we can see that he cuts multiple pieces of Muzan with each slash. On average, let's say he cuts about 2.5 pieces per slash. The picture shows him cutting 4 pieces with one slash and only 1 with another, with one piece just hovering, so the average:

(4 + 1) ÷ 2 = 2.5.

Now, he also mentions that he cut around 1500 pieces of Muzan, so we can divide to find the total number of slashes he made. That is:

1500 ÷ 2.5

⇒ ie; He made 600 slashes during that time.

⨳ Yoriichi's Average Striking Speed

Finally, for the moment we all have been waiting for. The speed by which Yoriichi is moving his arms would be:

n(number of slashes)×distance covered by Yoriichi/max. time frame = (600×5.786)/0.000345

~10,062,608.696 m/s

For Comparison: this is about 29,337 times faster than sound. ▪︎Have you guys ever played fruit ninja before? If you have, just picture Yoriichi taking on that game in real life; Number of slashes/frequency [1/T]= striking speed/ distance covered (gonna take 1/3 of the circumference of his slashes) Ie n= 10,062,608.696 ÷ (1/3 × 2 × 3.141 × 5.786) ∴ Slashes per second= ~ 831,361 So, if you were to toss about 8 hundred and 31 thousand fruits into the air, Yoriichi would be able to slice through them all in just one second! Meanwhile, I’m here taking like two entire minutes to chop an apple.

⨳ Yoriichi's Average Running Speed

So we have found out Yoriichi's striking speed; however, that doesn't tell us anything about how fast he can run. Since we're already looking into Yoriichi's speed, why not find out about his running speed as well?

"In an average person, the legs are able to push roughly four times as much weight as the arms can pull. What's more, the legs have an even better advantage when it comes to endurance."

Although there is no relationship between strength and speed, let us just try finding it ourselves.

Fleg-mg= ma (force exerted to lift your leg. Could have used the work formula, but then I realised that you're probably not doing any work when it's your own body. The same could be said for the force, however. Though this is an idealised situation and it really doesn't matter because:) ∴ Fleg∝a a∝v Let force required to push your arm be be f⁰ & leg be f Since f⁰ and f = 1:4 => f⁰/f=v⁰/v = v⁰/v= 1:4

This would mean the legs must also be 4 times faster than the arms.

Ie: 10,062,608.696 m/s ×4

= 40,250,434.784 m/s

For comparison: The speed of light, 299,792,458 m/s is only about 7× faster than Yoriichi's running speed. ▪︎If Yoriichi were to complete a journey around the entire Earth, traversing its full circumference, the time required for this would be: Earth's circumference: 40,075,000 meters Calculation: 40,075,000 ÷ 40,250,434.784 = 0.996 seconds [Wow.. now that's fast o-o] So imagine, if you ever find yourself missing a flight and in desperate need to get somewhere, all you have to do is call Yoriichi. He’ll have you zooming off faster than you can say “I missed my flight"!

poor muzan..

-> The distance between two countries [say, Japan to brazil] would be about 17,371 km (pretty sure it's not the road distance, so lets just just imagine Yoriichi can run on water) Time=d/s = 17371000/40,250,434.784 ...0.4 seconds to reach there.

▪︎But instead of a circumference; what about him covering the entire surface area of the earth? [not the area, but the entire outer surface, covering eacg and every path possible. Just visualize unfolding the entire earth into a flat ground.] So: 4πr² [csa/tsa] =4×3.141×6,371,000× 6,371,000 =509,805,890,960,000 m So the time: 509,805,890,960,000/40,250,434.784 12,665,848.050 seconds Which is about 3,518 hours Which is about 4 months I know now this looks kind of slow, but trust me- this is extremely fast. This pace equates to covering the entire circumference of the Earth approximately 29,348,102 times.. (29 million times)

⨳ Final Thoughts:

A/N: I tried my best to keep this entire post simple and concise as possible. For some reason though, I still feel like it might be more technical than I intended. I’m not sure this post will get much attention because of that. It doesnt matter though, I really enjoyed putting all of this together. I truly hope it proves helpful to someone out there who might find this interesting.

And to anyone who made it till here, I thank you wholeheartedly!! You’re amazing for sticking with all this. And if you think that I may have made any mistakes, then feel free to correct me!

Sources:

Leg Strength as a Limiting Factor, climbstrong Detonation velocity, wikipedia Table of explosive detonation velocities

#「ᴛʜᴇᴏʀɪᴇꜱ & ᴀɴᴀʟʏꜱɪꜱ」#Yoriichi speed#kny yoriichi#yoriichi tsugikuni#Kny analysis#Kny theory#demon slayer yoriichi#demon slayer#kny rp blog#tsugikuni yoriichi#kny#kimetsu no yaiba#Kny nerdery#How fast is yoriichi#kny yoriichi headcanons

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why don't demons burn/feel irritated in the moonlight?

Asked by @/echantedtoon // Oh wow.. This is a very interesting perspective that I had never really thought about before xd! I pondered about this for a bit and came up with two reasonable explanations.. I couldn't decide between them, nor could I think of anything else, so you're welcome to dive into either option. And please, don’t hesitate to share any other insights or corrections you might have! <33

THEORETICAL EXPLANATION

1] So one potential explanation could be that the demons may have adapted to the limited exposure to sunlight.

2] Alternatively, as you suggested, the demons might actually be feeling irritated from the sunlight reflecting off the moon.[And although this is not explicitly mentioned in the manga itself, it is pretty reasonable to speculate that such a phenomenon could be occurring]

--For the irritation to affect the demons, there must be a source of that discomfort, implying that the moonlight could be causing them minor harm, albeit with their regeneration occurring rapidly enough to counteract it.

Also, a repeated trauma to their bodies like this must actually constantly hinder their healing process, albeit temporarily. This also indirectly suggests that moonlight has varying effects on demons based on their strength—the stronger ones have greater immunity, while weaker ones not so much, which would result in their weaker and slower regeneration, as most of the energy is spent on already regenerating the damage caused by the moon.

[Also, the fact that even the moon seems to work out of favor against demons just truly shows how much they're completely out of bounds with nature.. lol]

But again, these are demons we are talking about—their inherent strength and regenerative capabilities might only be the result of Muzan's blood rather than the moonlight itself. Nonetheless, it is a fascinating concept to ponder.

A MORE PRACTICAL EXPLANATION

Shifting our focus away from the demons for a moment, let's consider the roles of sunlight and moonlight:

▪︎All of the energy emitted by the Sun that reaches our planet is in the form of solar radiation, consisting of visible light, ultraviolet light, infrared radiation, radio waves, X-rays, and gamma rays. Radiation is one way to transfer heat. Among these, we know UV rays are the ones that cause us sunburns.

[Though, unlike UV rays, it is the infrared energy that actually provides all the 'heat' energy, and we can also see that the demons might be literally burning in the sun, one could also assume it might be more because of the thermal radiation. However, since we already know that demons are not susceptible to death from heat, this notion can be disregarded.]

Now if we consider the moon, we would need to know the extent of sunlight it actually reflects. This reflection is influenced by the angle formed between the Earth, Moon, and Sun. During the first and last quarters, the moon is only partially illuminated, while a full moon is fully lit, allowing it to be visible even in the early morning daylight.

In fact, the moon reflects not only sunlight but also light from the Earth, known as Earthshine. This indirect sunlight bounces off the Earth's surface and clouds, and some of it is reflected back to Earth by the moon, creating a subtle glow referred to as the moon's ashen glow.

▪︎Ultimately though, at this stage all we need to know is that the maximum amount of light reflected from the moon that reaches Earth at night is approximately 12%.

The full moon has a magnitude of -12.6, whereas the sun's brightness is approximately -26.7. This indicates that:-26.7-(-12.6)= 14.1 magnitude This means the sun is 14.1 magnitudes brighter than the moon. The apparent scale of this magnitude operates logarithmically, where a difference of 1 magnitude corresponds to a brightness factor of 2.512.

With this, we can conclude that the sun is about 400,000 times brighter than the moon.

For comparison: This is like comparing the exposure of radiation absorbed by the Chernobyl residents who were relocated, which is about 350 mSv, to the radiation being emitted by your everyday banana [10 μSv].

Yeah.. there's no wonder why demons don't disintegrate in the moonlight.

KOKUSHIBŌ

As for Kokushibou, I personally believe that the intensity of moonlight or its phases does not influence his power? I mean, I can't really think of any correlation between him and the moon aside from the symbolic aspects..

For instance, Yoriichi uses sun breathing, but his strength is more or less the same regardless of whether the sun is out or not. I think the same must apply for the upper one.. However, I welcome any additional insights you may have!!

#「ᴛʜᴇᴏʀɪᴇꜱ & ᴀɴᴀʟʏꜱɪꜱ」#kimetsu no yaiba#demon slayer#kny#Kokushibo#upper moons#Demon Slayer analysis#muzan kibutsuji#kny demons#lower moons#Kny nerdery

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm still riding such a high from bejng the Ikebukuro crowd yesterday since there so many people matching my energy. I had the fortune of being roped in with two other adult fangirls in Corp jackets and they also roped in a 6-year-old Giyuu cosplayer and her mom. There was downtime between main events and we all got along really well because we were all on the same fandom wavelength of "you haven't been to USJ? There's more than rides! Look at this Haganezuka!!" and "you haven't been to Hashira-ten? The cafe food was actually really good!!" and "Look! You have that character! And that character! And that character!" and "You know what? I wish I had a Kakushi uniform." "YES."

But like, the 6-year-old. Was. So cool.

Once she got going with us, she just kept rattling and rattling off all KnY trivia, and we all loved it. She was so sharp. So confident in her interests. And she wasn't shy about noticing and identifying the other KnY items we had, which we of course loved showing off.

My favorite part was that I had a backpack with me and assumed I probably had a KnY key ring with me too. Correct. I had her guess which three demons were on it. And then after showing her the Tamayo, Yushiro, and Nezuko items on it, I revealed the Osaka Metro Kamaboko Squad card I still keep behind my IC card, and she delighted in images she hadn't seen before.

And because I was in travel-mode, I had a lot of KnY-themed pouches and other such items in my bag. And I kept pulling them out one after another. And she delighted in each one and totally picked up on that I put a Zenitsu keychain on a bag in the pattern of Nezuko's obi because he likes Nezuko. On my make-up bag that looks like Nezuko's bamboo, there is a little tag with a screenshot of Nezuko, and she delighted in pointing out that it was from when they met Tamayo. And then to really keep her (and me) entertained, I brought out my pouch that has Gotouge Taisho Secret doodles all over the fabric, and she explained the context of each one.

And, like, we didn't even get to every KnY item I had in my bag.

There were so many good moments. Taking the quiz with them was lots of fun too because we were all around the same level of nerdery. There were a lot of fun and difficult questions of all kinds--my favorite was matching the sound of a Zenitsu conniption to the correct bug-eyed screaming Zenitsu screenshot. The 6-year-old very easily knew answers we were shocked by but lost interest on any question that involved reading kanji. Singing Homura together to put the lyrics in the right order was like singing Kumbaya together. Everyone hanging around in that spot of Ikebukuro appeared to be on their phone concentrating on the same quiz.

Aaaaaaaa it was so much fun!!!! Fans don't usually interact with strangers much at these sorts of events, which is why I typically just get my fill by people watching (there is so much to appreciate), so it was such a blast to go on a mission together with like-minded people.

Also, I really, really hate Tokyo but I do wish I could go to more gatherings like this.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

What even is Kimetsu no Yaiba canon???

Good question, that's why I've done all this digging. But I've also been asked a lot about what officially released material is and is not considered canon. I am but one nerd on the internet and no authority on that and my attitude is that you should take and pick what you want to use in fan work, because it's yours. However, in a lot of my fics I love trying to stick to canon, and that also means trying to incorporate a lot of official material that Gotouge did not personally provide.

So instead of saying "this is canon, that is not canon," here is my tier list. This is especially relevant when you have two officially released materials that contradict each other. The manga has been self-contradictory too, so if you sweat too many small details, your fan work will never get done.

God-touge Tier: Content Penned by the Gator 1. The actual manga chapters, for this may be all someone has ever followed in the Shonen Jump magazines, and therefore they have no other context 2. All other material published in the 23 volumes, including Taisho Secrets, 4-panel comics, and expanded epilogue chapters 3. The two official fanbooks (also referred to by the fandom as under names like the databooks or encyclopedias), which are widely available in Japan, and (as I understand) have been at least partially translated into an official English version 4. Additional material provided for special events, like the Gotouge gallery and Mugen Ressha movie booklet for early showings (these have included Taisho Secrets not printed elsewhere)

Extremely Influential Tier: The Ufotable Anime Content 1. Ufotable's interpretation of the manga (except in cases when it contradicts Gotouge material, though these are slight, like animating a scene in the wrong season) in the TV episodes and movies as they first aired, including filler scenes based on but not found in Gotouge material (like the paper airplane contest) 2. Additional content Ufotable added later (like extra scenes for when the first arc was re-aired on Fuji TV) 3. Filler content only loosely based on the manga (like the Rengoku special)

Also Very Highly Regarded Tier: Official In-Universe Spin-Offs On the Same Shelves at Japanese Bookstores (none written by Gotouge) 1. The Tomioka and Rengoku Gaidens (except in cases when it contradicts Gotouge material, like how Rengoku got that hair color) 2. The light novels 3. Novelizations of the manga Like High-Quality Fanfiction: More Ufotable and Shueisha Content 1. Drama CDs produced by Ufotable (often just little side stories and character exploration, not major stories) 2. Kimetsu Academy, a.k.a. the official AU Spin-Off, and by extension, the "Total Concentration Drill" books that are a spin-off of the Kimetsu Academy spin-off 3. Additional art books and design books (though these are usually very careful to not introduce anything new, and merely reflect content already shown elsewhere) 4. Sometimes I am really tempted to put the Rengoku special all the way down here

Official material which I do not consider to have any baring on canon whatsoever, but which are simply fun and nice: 1. Any form of live stage performance (the musicals, the voice actors reading from scripts, concerts, the Noh adaptations, etc.) 2. Officially sanctioned games, especially the plot elements in a video game like the Hinokami Chronicles 3. Galleries like Zenshuuchuu-ten (though these usually stay entirely based on material already introduced in anime canon) 4. Tie-in collaborations 5. Any form of official sanctioned parody created by someone other than Gotouge (like the 4-panel comics compiled into a volume with the Gaidens) 6. Commentary from the directors, voice actors, etc.

Unofficial material which is fun for expanding on things but has zero baring on canon, nor should it have any influence on what the aforementioned officially sanctioned creators do with it: 1. Books that nerds have published with Kimetsu no Yaiba analysis while teaching fun facts about the Taisho period and demons and such (this is a bit of a trend in Japan, and maybe other countries have publications unabashedly capitalizing on the KnY trend) 2. Fans who create meta and headcanons 3. Fans who create fanwork out of love for the series, regardless of whether or not they stick to canon Things that make me say "nope" 1. Low-effort articles and videos that get the facts wrong 2. Fans who spread rumors by claiming something is canon, but that something is reflected nowhere in the aforementioned top four tiers 3. Anything AI-generated

#hope that clears it up for people who have asked 'is XYZ canon?'#'yes but also no' is how the reaction gif with the pirate goes right?#basic advice: strive for Gotouge canon above all else but otherwise chose what works for what you want to do with it!#fanwork is for fun#kny fandom theories and meta#kny nerdery

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

References for KnY Writers: Taisho Period

Below are links to my entries about the Taisho Period and how it might affect the KnY characters (at least according to canon resources, my research, and my interpretations). Please see here for the full masterlist of References for KnY Fic Writers.

Background info: The Taisho Period (1912-1926) a bit of an in-between period in a lot of ways, with Westernization already several decades underway, but with many new policies not yet uniformly enforced in the countryside. In some ways, rural life went on like it did in the late Edo period. The majority of Kimetsu no Yaiba most likely would have taken place in 1915. This means that it's still a little early for the full-on "Taisho Roman" fashions, but the groundwork was there.

-Notes on Corp salary, simple conversions into Taisho currency, as well as other monetary details -Taisho Period overview of the Yoshiwara Pleasure District -Photos and details of preserved Taisho Period brothel -How a Taisho Period birthday may be celebrated -How a Taisho Period New Years may be celebrated (in the case of the Kamados) -How keeping track of one's age was different in the Taisho Period -Photography and education in the Taisho Period -More on Taisho education and literacy rates -Marriage and being a girl in the Taisho Period -Polygamy and the Meiji Civil Code -Dating and wedding night protocol -Being queer in the Taisho Period (and beyond) -A few real life folk songs featured in KnY -Taisho Period undergarments -Taisho Period beverages and drinking age (separate masterlist of KnY-related food here)

-Flush toilets were a thing (and there are toilets in the Infinity Fortress)

535 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m mostly talking about muichiro here, that is NOT someone who is 5’3 standing next to someone who’s allegedly 5’11? Did they make him taller or smn?

also here, there looks like there’s less than an inch between him and mitsuri. And if mitsuri is allegedly 5’6 wouldn’t that make muichiro 5’5 instead of 5’3? Also iguro and shinobu look like they’re around the same height? Ughhhhh

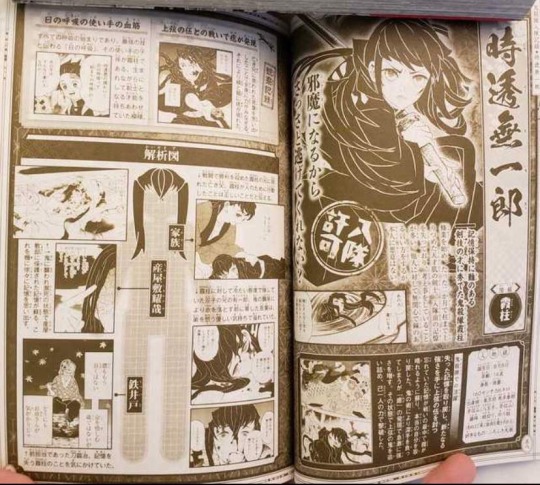

Now ofcourse we have the data books. Still waiting on translations for the muichiro pages. It’s important to know that numbers here are written in imperial units and are translated into actual digits, this can lead to inaccuracies as someone from the wiki wrote that the weight translations for some of the other characters are inaccurate.

Maybe I’m over thinking this but ughhh it’s been bothering me since the anime got adapted, rip manga genya and muichiro’s height difference but props to muichiro for getting taller lol

Just a question, do we ever get official confirmation for the heights of the hashira/other cast members or is it all speculation? Does anyone have any sources? I’m seeing so many inconsistencies with their sizing and it’s pissing me off. Pls help 🔥

#kny #demon slayer #Heights #sources #fanbooks #kimetsu no yaiba #official #sos

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Determining Ages and Birth Years

Kimetsu no Yaiba’s first official fanbook gave us ages for the many of the main characters, but in a manga where calculating age can be crucial, why are these numbers not so straightforward? Because the Japanese calendar is a mess, and the Taisho period was an in-between stage in many ways. Many new changes were established in the Meiji period but not broadly enforced until the Showa period, including how to count one’s age.

This subject can be terribly complicated, but please follow me below for:

--Historical context for how methods of counting age could differ --Which method I choose to apply to Kimetsu no Yaiba and why --Based on that, a list of my calculations for dates of birth, zodiac signs (Chinese and Western), and because it’s handy, the date each of these characters would have turned 25

In the Taisho period, there are two methods of counting age in play:

Kazoedoshi (“counting years”): Counting the years one has been in alive in, with that year having started on the agricultural new year and counting a new year to one’s age each New Year’s Day after that, like how it is still practiced in South Korea.

Which is to say, you are born at age 1, counting the first calendar year you lived in, and on the following New Year’s Day, you are age 2, even if you have only been out of the womb a very short time.

Mannenrei (“full year age”): Counting only each full 12-month period since your birth as part of your age, like how it is practiced in the United States of America.

Which is to say, you are born at age 0, and after twelve full months have passed, you are age 1.

Kazoedoshi was practiced through most of the Demon Slayer Corp’s history, but the Meiji government enforced a switch to Mannenrei in 1902. However, most people still practiced Kazoedoshi throughout the Meiji, Taisho, and early Showa periods, and it wasn’t until 1950 that the government reinforced the switch to Mannenrei. This is also when, with the influx of American culture due to the post-war occupation, individual birthdays started to be marked with cake and presents. Until that time, people did not pay much attention to their date of birthday besides, perhaps, a passing notion and maybe a shrine or temple visit and a nice dinner (see more on this post). Many people continued to count their own age in Kazoedoshi until 1950, and although some people liked the “oh, actually I’m younger than I thought I was!” surprise (because Manrenrei really was outside of their usual way of thinking), it made centenarians a little sad that they hadn’t actually reached 100.

Similarly, even though the Meiji government enforced a switch to the Gregorian calendar which put New Years on January 1, many people still celebrated a sliding date according to a lunar-based agricultural calendar, like is still done in China. It was likewise later reinforced.

In modern Japan, New Years on Gregorian January 1 and counting age by the Mannenrei system are the norm and standard, however, some customs (especially but not limited to religious customs) are still celebrated according to the agricultural calendar and Kazoedoshi ages. It’s annoying to keep track of and if I had a 5-yen coin for every time I say the Japanese calendar is a mess, I’d have a lot more yen.

The canon of Kimetsu no Yaiba does not specify any of the following: 1. What year most of KnY takes place (but based on clues from the Hand Demon, we can extrapolate that most of it takes place in 1915) 2. Whether the characters’ given ages are according to Kazoedoshi or Mannenrei, and whether the characters’ given birthdates are according to the Gregorian or agricultural calendars 3. Which method the characters use to count New Years and their own age 4. If there are any differences among the cast and how they count these things (like if the city-slickers were with the times and the country bumpkins were not) 5. Whether or not Amane accounted for Mannenrei or Kazoedoshi when stating that all the marked swordsmen of the Sengoku period died by the age of 25

So what are fanfic writers who are preoccupied with canon accuracy to do? How much should the fans of characters who got the mark fret?

After tying my brain in knots (for years, since I attempted tackling this issue years ago and this is my better post addressing the issue(s)), here are the ways that I approach it.

First: I firmly treat most of the events of canon as firmly taking place in Gregorian 1915, with the Final Selection taking place that winter and Muzan’s defeat coming sometime around the very end of 1915 or start of 1916. (See here for how I calculated all the time frames indicated in canon. You’re welcome.)

Second, we have to treat the official fanbook material in the context of how it was published. I think the ages in the fanbook are given in Mannenrei for the benefit of Heisei/Reiwa period readers, but if you really want to dig into it, the characters might interpret their own age differently based on Kazoedoshi, since it was such a prevalent way to count one’s age even for people born in the Taisho period. For example, Tanjirou’s given canon age is 15 (Mannenrei), but if you ask him in-universe, he might say he is 17 (Kazoedoshi).

Even if we assume many of the characters use the agricultural calendar and Kazoedoshi, there is a chance that characters who actively used western technology—for example, Shinobu, who uses textbooks in English microscopes and thermometers that likely came from Germany—had switched to Mannenrei for the sake of more accuracy on an individual basis. It is also possible that the Corp enacted their own standardization to Mannenrei around the time they standardized uniforms and updated the payment structure. If this is the case, it might have required country bumpkins to rethink the systems they had always been used to. Tanjirou, if asked in-universe once he is a Corp member, would therefore say he is 15 (Mannenrei).

The places the Kazoedoshi/Mannenrei difference has more implications is where characters have stated their own age. For example, Himejima seems to use a Mannenrei system (he states that he became a Hashira at age 19, and now is clearly over the age of 25, with his canonical age being recorded as 27. The numbers check out). This makes me more curious about Muichirou, who has a canonical given age of 14, but says in his own recollection that he was 10 when he was orphaned, and 11 when Yuichirou died.

If Mannenrei: It was four years or more ago that his parents died, and then sometime after he and Yuichirou turned 11 on Gregorian August 8, the demon attacked on a hot summer night. If Kazoedoshi: It was four years or more ago that his parents died. New Years passed that winter and he and Yuichirou turned 11. Many more months passed before the demon attacked on a hot summer night. However, if the Corp enforces his Mannenrei age of 14, but being a country bumpkin with a fuzzy memory, Muichirou still thinks of himself in Kazoedoshi, thereby making him think of himself as 16: It was six years or more ago that his parents died. New Years passed that winter and he and Yuichirou turned 11. Many more months passed before the demon attacked on a hot summer night. He nonetheless became a Hashira relatively recently (according to aligning Kyojuro-related flashback material and the second fanbook making passing mention that he hasn’t been a Hashira that long so his impression of the others isn’t that deep). This implies he spent a very, very, very, very long time incapacitated before he could so much as hold a sword, let alone join the Final Selection.

So what if we consider the opposite, that every given age is in Kazoedoshi? That would mean that when the fanbook and Tanjirou say he is 15, we would translate that back to a Mannenrei age of 13. And, dear readers, do you really want to imagine the entire cast being one or two years younger than their given age? I didn’t think so.

It is already very, very difficult to determine the order of Kimetsu no Yaiba canon both due to incomplete histories and canonical errors introduced by outside material (Ufotable animating Kanao’s May 19 encounter with the Kochou sisters with a winter setting, or Hirano-sensei drawing a spread of all nine Hashira in a 1913 setting) or timeline errors introduced in the original manga likely due to oversight (Gotouge drawing Aoi in uniform shortly after Kanae’s death when Aoi is later stated to have attended the same Final Selection as Muichirou, who at the time Kanae died is likely still living with his parents). That is why I assume the following rule of thumb:

When ages are given in-universe or in supplementary material, assume it is Mannenrei, because this is a shounen manga and not a math textbook. (As another case in point, the heights of the characters would have made most of the characters giants in Taisho society, though they get away with just being a bit on the tall side in Reiwa society. Some things are simplified for the benefit of modern readers.)

Assume the characters do not pay much attention to their age, or their birthday, because this is a shounen manga with a lot of dedication to historical settings and folk traditions (and those folks didn’t pay much attention to their birthdays).

Ergo: If the Corp tells its members “this is your Mannenrei age, use it. When we say 25, we have already done the math from our Sengoku period records and we mean 25 in Mannenrei,” the Corp members probably accept that. However, the Corp members might think of it as having two ages for two different purposes. Given the prevalence of Kazoedoshi, in their heart, they might still think of New Years as the time when you collectively celebrate everyone’s birthday.

Since I’m assuming Mannenrei, I’m also assuming Gregorian birthdates, and assuming everyone’s given canon age to be the age they were during the Infinity Fortress battle that took place roughly around New Year’s Day 1916.

Why am I picking this date? Because this is when the first fanbook was published, and it treated canon as it was occurring at that time in publication, so Akaza, Douma, and Kokushibou were not yet given the “eliminated” status (also, Rengoku was given already called “former” Flame Hashira. Shinobu’s demise had not yet been published in the serialization).

I also say “roughly New Year” because of the agricultural/Gregorian calendar issues. The agricultural New Year’s Day in 1916 would have fallen on Gregorian February 4, but because I’m treating this as the Corp having adopted Mannenrei, I’m also having them treat Gregorian January 1 as New Years. Because Ubuyashiki Nichika and Hinaki were singing a New Years song when Muzan strolled in to visit, that leans credence toward it happening around then. More crucially, cherry blossoms are in full bloom “three months later,” which aligns it best with Gregorian January 1, since late March/early April is when you are most likely to get the full bloom of the most common somei-yoshino cherry trees.

It’s also a convenient date and time in the plot to measure by because all their birthdays would have passed for that year, barely including Nezuko’s. (But if Mugen Ressha took place prior to May, like I have calculated before… does this mean Rengoku would have been part of Team 21? My gosh, I’m crying. For this list, I’m treating it as the age he would have been relative to the others on that date.)

Tl;dr: I’m assuming you can treat every canon age as Mannenrei, and totally ignore Kazoedoshi in the first place (unless if it will help you be crafty in your fic, because there’s still a good case to be made for the characters using it).

Now here is the fanfic reference list I promised, including: 1. Their date of birth according to the Gregorian calendar, calculated based their canon age being their Mannenrei age as of December 31, 1915. 2. Their birth year according to the Japanese period 3. The year they would have turned 25 4. Their Chinese zodiac sign (yes, I know there is argument about whether or not you can say “zodiac” here, but this isn’t the place to start a new topic. Anyway, I’ve also included the elements for each year for the deep nerds who anticipate it) (also I’m really sorry, Inosuke is not born in the Year of the Boar, nor is Iguro born in the Year of the Snake) 5. Their Western zodiac sign (yes, I know there was a recalculation of sun signs some years back, but no, I’m not bothering to take that into account, this post is complicated enough as it is) Important caveat: I'm bad at math.

Kamado Tanjirou: July 14, 1900/Meiji 33 (1925/Taisho 14), Metal Rat, Cancer Kamado Nezuko: December 28, 1901/Meiji 34 (1926/Taisho 15), Metal Ox, Capricorn Agatsuma Zenitsu: September 3, 1899/Meiji 32 (1924/Taisho 13), Earth Boar, Virgo Hashibira Inosuke: April 22 (as was written on his fundoshi along with his name), 1900/Meiji 33 (1925/Taisho 14), Metal Rat, Taurus Tsuyuri Kanao: May 19 (chosen for the day she encountered the Kochou sisters), 1899/Meiji 32 (sometime in 1924??/Taisho 13??), Earth Boar(?), Taurus (???) Shinazugawa Genya: January 7, 1899/Meiji 32 (1924/Taisho 13) – by Gregorian/modern Japanese system he is an Earth Boar, but the agricultural New Year wasn’t until February 10 that year, so he might instead be considered an Earth Dog, Capricorn Tomioka Giyuu: February 8, 1894/Meiji 27 (1919/Taisho 8), Wood Horse, Aquarius Kochou Shinobu: February 24, 1897/Meiji 30 (1822/Taisho 11), Fire Rooster, Pisces Rengoku Kyoujurou: May 10, 1895/Meiji 28 (1920/Taisho 9), Wood Sheep, Taurus Uzui Tengen: October 31, 1892/Meiji 25 (1917/Taisho 6), Water Dragon, Scorpio Kanroji Mitsuri: June 1, 1896/Meiji 29 (1921/Taisho 10), Fire Monkey, Gemini Tokitou Muichirou: August 8, 1901/Meiji 34 (1926/Taisho 15), Metal Ox, Leo Himejima Gyoumei: August 23, 1888/Meiji 21 (1913/Taisho 2), Earth Rat, Virgo Shinazugawa Sanemi: November 29, 1894/Meiji 27 (1919/Taisho 8), Wood Horse, Sagittarius Iguro Obanai: September 15,1894/Meiji 27 (1919/Taisho 8), Wood Horse, Virgo

Afterword:

Suppose Amane didn’t do the math to state the Sengoku swordsmans’ ages in Mannenrei terms? What if their records were spotty, or she took Kazoedoshi and applied it to swordsmen who now use Mannenrei?

Well, in that case, Tanjirou would probably die sometime in 1923, and Giyuu & Sanemi sometime in 1917. Ergo, I think I will stick with Amane having done the math and converted Sengoku ages to Mannennei if she was going to tell them all something so important.

Also, using Kazoedoshi would totally mess with the Kimetsu Gakuen AU.

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

I continue to find it funny that Genya's birthday falls on the Festival of Seven Herbs, a lesser known holiday that marks the changing of seasons. There are deeper connotations of the practice throughout history, but I've had this holiday popularly explained to me as that "you eat so much food that can be rough on your stomach during the New Year holiday, so eating rice porridge with seven herbs is supposed to be good to help your stomach recover."

Forget birthday cake, everywhere he goes everyone should be trying to feed this boy gentle rice porridge with herbs.

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

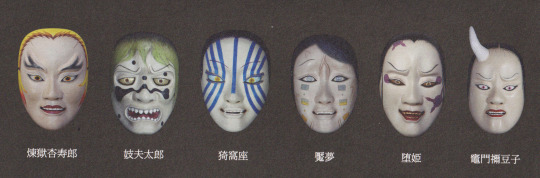

Appreciating the KnY Noh Production: Part 4

Humans are demons, demons are humans. Feelings passed on; bonds unsevered.

Or so goes the catch copy for the continuation of the Kimetsu no Yaiba Noh/Kyogen production, titled "Tsugu" (継). Very clever title, since this kanji is used in both 継続 ("continuation") and the KnY-specific term, 継子 (Tsuguko). In the catch copy, they also bend it to act like 繋ぐ, the "tsunagu" verb for "binding together" so often used in KnY, like Giyuu being told how he "brings forward" the will of those left behind, and prominent lyrics in "Mugen."

Of course, like I said when addressing how to translate the catch copy for the first KnY Noh Production, there are always different approaches--the same goes for how to translate a manga for the stage.

I felt they took a different translation approach this time--a more direct translation, and less fluency in the visual and audio language used in the Noh and Kyogen theater traditions. A Noh style of sparse dialogue and lets motion and chanting tell the story, and uses more breaking of chronology to let characters express their story by feelings instead of narrative detail. This, however, was more like all the snappy dialogue we already know and love moving the story along, but all delivered with Noh flair and Kyogen-style humor.

I'll be referring some Noh-specific character rolls and stage elements in this post, and probably referring back to the first production for comparison, so you'll get more out of this post if you read this overall post first, and these reactions to Act 1 and Act 2.

What words will probably come up most in this post: Shite: The lead character role; this is the character that often has a personal story to tell or character development to undergo. Waki: The character who helps draw forth the Shite's story, like a witness or listener. Kyogen: This is a humorous theater form often used as interludes in a Noh program. Often simply silly scenarios and word play. Noh: Start here. Bridgeway/hashigakari: the corridor leading to the main stage, where some of the story may also be staged to convey a different place or time or mental state.

An actor will often be raised in a family tradition that belongs to one school of Noh and one role type. The Ohtsuki Noh Theater took charge of this production, with its shite actors performing Tanjiro, Nezuko, and Gyutaro (previously Rui as well). Waki actors have traded off for the role of Uzui (previously Tomioka as well), and Kyogen actors have taken many of the other lead roles, such as Zenitsu, Inosuke, and Muzan. Actually, Muzan/Urokodaki/Tennoji Matsuemon/Kamado Tanjuro/Daki/Rengoku have all been played by Nomura Mansai-sama, a Kyogen actor with a lot of TV and movie experience as well who has been a driving force behind these productions. The man's name shows up everywhere and in everything and he's such a dork who clearly loves Kimetsu no Yaiba.

So anyway, Mansai-sama recruited a different writer to the project this time: Misaki Kana, who I could not immediately find a professional profile for. Based on her comments throughout the first version of the script which was included in the pamphlet, Mansai-sama had a big role in the direction this production took as well.

Clearly, Misaki has knowledge of many different Noh and Kyogen plays and classic poetry upon which to draw inspiration, but the sense I got both from watching the staging and reading her commentary was that she was, above all else, a deep fan of Kimetsu no Yaiba and felt hesitant to make too loose of a transformation of it. In many cases, such as Rengoku vs. Akaza, she chose to make as few alternations to the lines as possible. In other scenes, like Uzui bringing the boys to Yoshiwara, it was played in a Kyogen style but still played the original lines fairly straight, simply altered to fit the more archaic style of language. Even scenes that I highly anticipated seeing in Noh style (most notably, Gyutaro telling his story and then reaching a state of newly found peace) were performed somewhat close to the original pacing and straightforward set-up of the manga scene. Based on his commentary in the pamphlet, I think Living National Treasure Ohtsuki Bunzo found performing Gyutaro with nuance more difficult than how he performed Rui in a more traditional Noh style, which I thought worked extremely well.

So yes, I was left a little disappointed overall with how it seemed afraid to lean into Noh style this time, perhaps both for fear of alienating the main audience, and for fear of not living up to a well-loved original story. I would have liked to see this adaptation pushed a bit more like the first one was.

But that is not to say I did not enjoy it. I most certainly did, and reading Misaki's script and footnotes made me feel like we where fangirling together. Like we were squealing over the nifty little canon references she made. You could totally feel her love for the world and its characters. I also think Mansai-sama, who has a good understanding of many audiences and media, pushed for pleasing the Noh-newbies a bit more, and this production garnered a lot more audience engagement and big laughs (though there was still plenty of that in the original).

I still continue to find it very funny when Tanjiro, played in a very serious shite style, is on stage with Kyogen-style characters. Every line is delivered with utmost earnestness, from the emotional shouting after Akaza with lines that translated to archaic style beautifully, to honest-to-goodness Tanjiro simplicity inquiring what sort of deity Uzui is.

So let's take this a little more chronologically!

Act 1:

In which Lady Muzan recaps how Lower Moons suck and the oni hunter with the earrings must die. It makes a good framing device, but also, I think Mansai-sama and Misaki just really wanted to include Lady Muzan. The Kyogen-style Enmu played a pretty anime-like Enmu with a neat overcoat that suits a kimono, a mask, and a creepy glove. Enmu's theatrical personality translates as well as usual but it had nothing on the overt theatricality of the 4D stage musical Enmu-sama.

A major element of Noh is the use of chanters, and "Nen nen korori" worked very, very well for this. Aside from the repetitious sounds and the dreamy atmosphere they create, it was also accessible to an audience unaccustomed to understanding the important storytelling that goes on in Noh chants.

The Mugen Train made out of simply Noh props was adorable, especially when it moved in time with the drums!

Tanjiro performed in straight shite style in stark contrast to Zenitsu and Inosuke's more free and silly Kyogen styles, but Mansai-sama (technically a Kyogen performer) basically does whatever he wants to dominate most of the scenes he's in. That meant ditching the mask for Rengoku this time in favor of makeup that looked more Kabuki style. But also, I loved that wig that trailed all the way down his back.

(Photo from this article.)

The whole bentou scene played pretty close to the original dialogue, also though the first draft of the script had Rengoku monologing more about how his usual favorite bentou fixings make him "wasshoi" but how this new and different this bentou is. But also, he's called "Rengoku-dono" here instead of "Rengoku-san" and I loved hearing that.

There were no people infiltrating the dreams. They were kept simple with actors dropped in black wearing simple masks and props to take on dream characters. Nezuko in Zenitsu's dream wore an Ofuku-style mask--plump and comically cheery (and almost exactly like this), and they were adorable as they happily skipped around the stage arm-in-arm. skipping around stage. Also, he called her his beloved "Nezuko-dono" and before he noticed her appear he was saying how he wished to show her this lovely scenery and he started writing about it into a story which was an overt "Legend of Zenitsu" reference. Inosuke chanted the "ore tachi doukitsu tankentai" which I love almost exactly as in the anime. Tanjiro's dream was played pretty straight and simplified. No Shinjuro or Senjuro characters; Kyojuro instead monologues that part of it and then dreams of a memory of his mother, and Ruka made for such a good Noh character!!

Not only that, but she was written to look and move similar to the famous "Hagoromo" play! In her notes, Misaki made this choice based on fanbook mention of Rengoku enjoying Noh, and assuming Ruka and the rest of the Rengoku family would have appreciated it too. It does not seem she took the drama CD into account, in which Hagoromo is stated to be Ruka's favorite play (and I analyzed that more here). The pauses and gaps between the actors really spoke here and made this the most Noh-like scene of the whole production, I felt.

Enmu as a train--basically, with a worm-like appendage out his back carried by multiple actors in black, moved convincingly both like a train and like flesh down the bridge way, and during the fight on center stage, it looked inspired by a theatrical Kagura style battle against a Yamata no Orochi (giant 8-headed serpent).

(Photo from the official Twitter)

And then Akaza, oh boy. Similar to Inosuke and Gyutaro, he had full attire with textures and symbols to fit his personality as well as the Noh stage, but what I really was not expecting was the light-up props that he and Kyojuro used. In the first production, Tanjiro fought Rui in a traditional Tsuchigumo (demon spider of canonical Noh) style battle with paper string webs all over the place, but this time they clearly chose "cool" over "tradition." When they moved their glow sticks, Akaza created the illusion of floating snowflakes and Kyojuro's sword truly looked like it had flames coming off of it. I can wrap my brain around the spinning props creating snowflakes (and this slow-exposure photo takes it to an extreme), but those flames broke my brain. (I'm just so glad it wasn't projection mapping; I usually find projection mapping cheesy and feel the simplicity of physical props suits the Noh stage better.)

(Photo from the official Twitter)

The fight was brief, though. Tanjiro's lines shouted after Akaza sounded great in the shite delivery style, as does "set your heart ablaze." I really thought we'd get the satisfaction of seeing Kyojuro follow his mother down the bridgeway (see symbolic of moving on to the after life or attaining some level of peace), but we did not get that. Kyojuro died kneeling the middle of the stage after seeing his mother at the edge, then she went on alone. Tanjiro stayed at his side, a crow slowly circled the stage, and then Tanjiro began heading off alone, taking one look back as the lights fell on Act 1.

Perhaps we could take this as Kyojuro not having needed some spiritual change to occur in his character--he was profoundly at peace with everything from his father's treatment to his own mortality.

But also I COULDN'T SEE KYOJURO'S FACE AT THE END BECAUSE A STAGE PILLAR WAS IN MY WAY but otherwise I had a good view of things.

Act 2

We start with Warabihime-oiran making her fancy walk with an entourage celebrating her, then we got cut over to Uzui bringing the boys into the scene. He was very, very shiny. Like. The brightest of silver brocade you can get in a Noh costume, probably. When he told them to be dogs and monkeys, Kyogen actors Zenitsu and Inosuke did just that, while Tanjiro, in full shite-role seriousness, earnestly treats Uzui as a god. Since Uzui was played as a waki role (an often quieter side character who bears witness to the main shite-role character's story unfolding) I wondered if this would not be flashy enough for him, but I was sold on this waki-Uzui. No shame at all in putting a foot up on the banister of the bridge way as he declares himself a god and pushes Inosuke away after the king of the forest gets up in his face and introduces himself.

In part of the original script:

Uzui: Listen well, you all. I am a god! A god's words are absolute. Tanjiro: Understood. You are a god who rules over what? Zenitsu: What are you talking about? Uzui: I am a god who rules over that which is flashy... the god of festivities! Tanjiro: Understood, God of Festivities-dono. Inosuke: I'm the king of the mountain! Uzui: What are you talking about? Zenitsu: (Makes a face at the audience that says "Wasn't saying 'What are you talking about?' my line!?")

We then got a Kyogen interlude featuring the Muscle Mice! They were a delight, even if this was no where near as long and involved and full of puns as the Kyogen interludes in the first production. Still, it was nice to hear them chat and build themselves up for being Uzui's trusted mice, get a little distracted by the beautiful sight of their own muscles, and provide more exposition to carry things along. Again, being so plot-driven made it feel a little less like true Noh/Kyogen than the first production, but I'll take all the Muscle Mouse content I am gifted.

Daki has a moment with Muzan, whose face is hidden behind a curtain and whose lines are played from a recording. This is because Mansai-sama played both Muzan and Daki.

(Photo from this article.)

Although Sumiko and Inoko made brief appearances in the original script, this was probably cut due to the constraints of time and costumes/makeup changes. However, there is a brief chance for Zenko to lament being the last to be sold off and playing a broom while someone plays a shamisen at the side of the stage. Worth stating here, you don't typically hear string instruments in Noh--drums, chanting, and flutes are more traditional, but this performance also made extensive use of a koto and even an erhu. Traditional Noh fans might not acknowledge this performance as Noh because of all those unnecessary instruments.

After a brief moment for Daki to call out Zenko for barging into her room and for being ugly, Zenko and Inosuke fight the obi down the bridge way. We get to see Zenko with a balloon for a sleep snot bubble and Inosuke totally drop archaic language to tell him he should always stay asleep.

(Photo from this article.)

Tanjiro and Daki briefly fight, Tanjiro falls away so that Ohtsuki Yuichi can do a quick change into his Nezuko costume, complete with a one-horned mask. I loved her entrance--Daki is happily monologuing to herself when Nezuko appears right beside her with a loud stomp. Fun fact: stomping is an important element of Noh performance techniques, so there are big, hollow ceramic jars below the stage to amplify the sound. This was excellent for Nezuko vs Daki, as it was a lot of vigorous stomping until Uzui came in, beheaded Daki, and ordered Tanjiro to sing Nezuko a lullaby. The chorus chanted/sang it as Nezuko dreamily left the stage. (Meanwhile, Misaki's first draft had Tanjiro performing the first line of the song, and noting basically, "Not sure how they'll pull this off since the same actor plays both roles. I look forward to whatever they figure out!")

Then comes Gyutaro, played in more of a straightforward Gyutaro way than the Noh style I anticipated... Ohtsuki Bunzo's full-on Noh style Rui was so impactful, and I think leaning away from Noh delivery in favor of making it more familiar to the KnY fans did not work in Gyutaro's favor. Thing we could have stood to get a lot more impact from the whole Gyutaro & Daki story, like a dance as he tells his back story and attains peace for having faced it (and had Tanjiro take more of a waki-role in witnessing/listening). Theirs is the kind of story that really would have lended itself well to a Noh-style storytelling approach. Oh well, at least the 4D stage play musical used the best of it's theatricality to do Gyutaro a lot of justice.

The battle was alright but brief, the dying heads arguing with each other worked well, but Gyutaro simply remained a head until it was time for he and Ume to reconcile and head off to the afterlife. A straightforward Noh style ending with them heading down the bridge way, but not the impact I was hoping it would have like seeing Rui take that path with his parents. That being said, in the original script, Misaki paid homage to canon Noh plays like "Aoi no Ue" that have a kimono prop represent a female character, and Gyutaro was intended to carry that kimono off as Ume. That probably would have been too hard for Noh-novices in the audience to understand, though, so Mansai-sama simply did a slight costume change instead.

Tanjiro concludes it nicely with lines reminding us of the core of these plays*, and then Muzan struts out in a nice framing device to mirror the beginning when he's announcing to the Lower Moons that Rui is dead. Gyutaro failed, his 12 Moon Demons keep dying ever since those cursed Tanjiro and Nezuko appeared. Meanwhile, ever-serious shite-style Tanjiro just glowers at him from the bridgeway.

*I would say "that brings us back to the catch copy for this play!" but I don't remember precisely, and it wasn't in the first draft of the script. Still, they are are fitting. To go with different possible translation this time:

Humans and demons, demons and humans. A will carried forward, and a bond that can never be cut.

人も鬼、鬼も人 継なぐ想いと切れぬ絆

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

This isn't something that belongs on an upcoming oni blog, but definitely on the Kimetsu no Yaiba one. It's not totally meta levels of related and requires a little cherry-picking, but here are two "oni" origins (among many) that I love for how you can see them hidden away in the KnY lore.

First, metal working was a possible source of oni legends. One reason is because working the fires damaged the skin of the metal workers, so they had a frightening appearance (the shapes of their faces as they squint and blow into the fires is also an origin of Hyottoko "fire man" masks). But it's also because of how society viewed them. Collecting the iron and firewood from the mountains could be disastrous for the farms downhill from those metalworking sites, so that's a direct way to blame them for your family's misfortunes. However, there is also a common pattern of casting people who were opposed to (what would eventually be) the centralized ruling power in a negative light. Many "demons" of, say, Heian period lore were recently bandits forced into that lifestyle because they refused to be subjugated, or centuries beforehand, they were opposing kingdoms. Those kingdoms were often strengthened by thriving metal industries, and therefore especially fearsome foes to subjugate (or eliminate).

While we're speaking of the Heian period, this is also when some of the first dictionaries of the Japanese language and records of etymology were recorded. The idea of an "oni" was still a conflagration of multiple ideas and had not yet turned into the "oni" image that comes along in later periods, like ones that popularized the tiger skin loincloth and horns look or the gaping mouth hannya look. At this point, "oni," was still defined more as "that which is not seen." Although it was written with the character we now know as 鬼, its meaning was fairly closely associated with another kanji: 隠. This character is read "kakushi."

#kny nerdery#kny fandom theories and meta#we could dive so deeply into how this makes demons more relatable because the potential lurks in all of us#and how to fight a demon you need to do everything you can to make yourself on par with a demon however temporarily

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kamado Family Name Analysis

竈門: Kamado A rare but existing surname, the hearth (竈, kamado) is also an important gateway (門) through which disease can enter a home and make a family sick, so it therefore needed special attention in order to keep the family healthy. Likewise, it required care so as not to cause fire damage. However, it was likewise the source of sustenance for a house’s inhabitants, so the state of a hearth also reflects the state of the family. To say things are lively around a hearth is to say that a family is doing well, to say that the hearth is broken is to say that they’ve lost their fortune, and so on. You could also think of the fire itself sometimes being a cause for danger, something susceptible to evil influence, like how it might burn humans, so it took having a god of the health to protect against that too. These are reasons why the god of the hearth has been worshiped since ancient times, not only for protection from the dangers of fire, but also for prosperity.

As for the the personal names throughout the generations, follow me below...

Sengoku Period (often considered 1467–1568, though other dates are in use):

炭吉: Sumiyoshi Although you don’t typically see charcoal (炭, as sumi or tan) in a name, 吉 isn’t all that uncommon, whether as yoshi or kichi. It means “luck.” It’s worth stating right away that although making charcoal means working with fire for a few days at a time, it also means the longer-term work of forest management. A charcoal worker is nothing without plants. Notice the 山 (mountain, yama) that is also with 火 (fire, often hi or ka) in the 炭.

すやこ: Suyako Presented only in phonetic hiragana, we don’t have kanji to read into, but this is a pretty clever name. Because how -ko makes it sound like a typical girl’s name, similar to her descendants Nezuko and Hanako, the su also makes it feel similar to the rest of her family. Suya doesn’t really mean anything on its own, but suyasuya is an onomatopoeia for “sleeping soundly.”

すみれ: Sumire Another clever one presented only in phonetic hiragana. Sumi makes it sound like she inherited the charcoal family name, but sumire means “violet,” so this is a precursor to later Kamado family naming trends. (However, the flowers she gave Yoriichi were not violets, but Catharanthus roseus—as a fun tidbit, these are called nichinichisou, that is, “sun-sun-grass” (日々草).)

Meiji Period (1868–1912) & Taisho Period (1912–1926):

炭十郎: Tanjuurou (Whatever)+郎(rou) is pretty common in men’s names, since it’s basically like adding “son” to the end of boy’s name. Using numbers in men’s names (like the number 10 here, 十) used to be relatively common too.

葵枝: Kie Although 葵 (aoi or ki) is commonly translated as “hollyhock” (due to being conflated with tachiaoi), it is more accurately translated as “wild ginger,” but this is annoying because even though it has a similar scent, it is not actually related to ginger. Let’s just call this low-growing herb aoi, since it has a lot of religious connotations with ancient shrines and festivals—but this is also annoying, because there is a character named Aoi and her name is written phonetically and might be in reference to the color. So let’s use the Latin name for this genus, Asarum. 枝 (e) is “branch,” so Kie’s name is literally “a branch of Asarum.” But, if we want to go a step further, in older ways of transcribing Japanese, 葵 used to be written phonetically as a-fu-hi with a-fu meaning “to encounter (later on transcribed as au)” and hi being a word representing a god’s power, so it’s said that the a-fu-hi/aoi plant symbolizes coming upon incredible power. How ironic that Kie married into a family known for Hinokami Kagura.

炭治郎: Tanjirou We’ve covered 炭 and 郎, so why the 治? This is a pretty common way of adding the ji sound to a guy’s name (like Hakuji), but why this one instead of, say 次 or 二? This may be because Gotouge wanted to give his name both fire (火) and water (水)! You can see the fire in the charcoal kanji, but the three dots at the left side of 治 are the water radical, which often means the kanji might have some association with water. Although 治 literally means things more like “quell” or “reign” or even “heal,” it can also mean being in control of something like a river.

禰豆子: Nezuko First off, most OS systems do not express this first kanji correctly. The left radical would look more like ネ, with 爾 on the right. Alas, 禰 (ne) is a bit of a rare kanji in the first place, meaning “ancestral shrine.” This is kind of heartwarming what with how connected Nezuko is with her family, and how the checkerboard pattern the Kamado family uses also denotes a continuity of family. As for the 豆 (zu or dzu or mame), this is “bean.” Beans are deeply tied with warding off demons. This is especially seen in the Setsubun custom of throwing beans at demons to cast them off. But, more recently I stumbled upon the knowledge that the kurobe tree (Japanese arborvitae/Thuja standishii), a coniferous evergreen with flattened branchlets, is also called nezuko (in phonetic katakana, ネズコ).

竹雄: Takeo “Bamboo man,” with 雄 (o or yuu or other readings) being a pretty common thing to stick to the end of a man’s name. It’s a kanji with a sort of heroic ring to it if you're adding the masculine -o ending anyway). Fast-growing bamboo (竹, take) can be a problem if, say, you primarily focus on making charcoal out of oak, but bamboo charcoal has a lot of uses for keeping spaces around the home free from humidity and bugs. What’s more, bamboo itself is a bit of a heroic plant—it grows straight, stays strong through the winter, and can stand a lot of pressure and still flexibly bounce back. I've also heard of it being associated with happiness because there is a bamboo radical at the top of the kanji for "smile/laugh" (笑).

花子: Hanako “Flower Child.” The plants are a bit obvious in this one.

茂: Shigeru Another common manly name, “to flourish.” Like plants would flourish.

六太: Rokuta I have tried really, really hard to look for hidden meaning this one. He’s just “six” (六, roku) with another common way of ending a boy’s name, 太 (ta or tai, for grand, broad, magnificent, or fat). Tanjuurou and Kie weren’t feeling very creative by the time they got to this one. Couldn’t you guys at least have given him a plant reference? That would have really helped my meta out, thanks. But maybe not all is lost on this name! After all, remember how we might conflate 火 (fire/hi) with 日 (sun/hi) in Hinokami Kagura? Arguably, the sun is just as important for charcoal workers who manage the forest! 日 is not the only way of writing "sun." There is also 太陽 (taiyou)!

Heisei Period (1989–2019) & Reiwa Period (2019–current):