#all i want is a functional symmetry and movement reflection tool

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I agree with Ransom VT and expand on the point of the range being limited with an example for the 3D only folks. Live2d is like making a 3D sculpture with paper doll parts that can break some rules that physical paper can't. To implement any kind of significant movement is going to require exponential amounts of time and effort.

Take a non-dot nose for example. In Live2D, if your artist and rigger aren't on the same page with this then it's going to end in absolute failure.

The artist needs to know that for a semi-real 3D nose to work for a model that will be able to achieve more than the tiniest XY head movement, that they're going to NEED to break up that nose into ~10+ pieces. Mine require 13 pieces to implement.

Then your rigger needs to know what the fuck to do with all 10+ of those nose pieces and how to envision what is essentially 10+ pieces of paper sliding around to animate something that resembles a nose going from front facing to 3/4ths head angle facing. This takes a LONG TIME (for me, usually a day or two) and at the end of the day, what do you have? A nose. Its not even a feature that actively adds to your stream besides distancing you from an anime aesthetic. For 3D models, its the relatively simple matter of sculpting it and then turning the camera. Boom. Your nose works in all angles. Similarly, I imagine that there are unique challenges that take exponential effort and time facing 3D sculptors and riggers with models in achieving some things that 2D models have with ease, but I don't come from the world of 3D modeling and don't know what those things are. All I can attest to is the exponential time and effort needed to achieve any kind of movement in L2D.

I might also add that Live2D is still implementing features that some would say are vital. Symmetry meshing and blend shapes were added in the 4.2 update on June 2022. Before 4.2, if you wanted a symmetrical mesh, you'd have to manually mesh half of your piece, copy, paste, and flip (and pray L2D didn't shit its pants and send vertices flying all over the place) and then connect the center, and that was the easy trick method! Today, you can use the symmetry mesh feature, but that Shit's broken af. You'll place 30 dots and L2D will forget to put down 5 of them on the other side. So ultimately, I think that part of why there's so much energy behind improvements in the 2D space is because our key software, the only software that can do what we need it to do, is objectively kind of shit.

I know it’s cause there’s a lot more attention and energy focused on Live2D improvement and features, but man 3D feels so behind on stuff it should be able to do.

#Live2d#I'll comment on L2D's quality#my comment is that it's shit#this is a live2d slander post#all i want is a functional symmetry and movement reflection tool

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

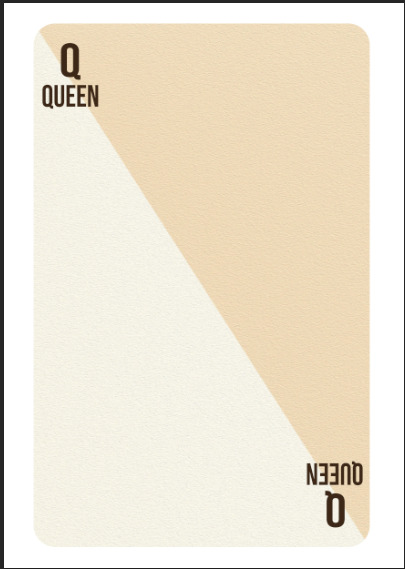

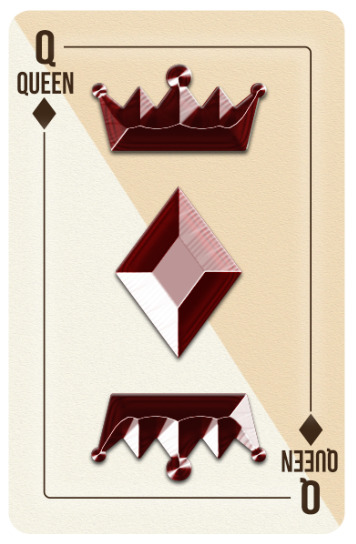

My Final Card Design and Development (The Front):

When going into my final design, I already had a rough sketched design that I could use from my previously created cards. The reason behind the card change that I was getting tunnel vision. I could not see past my previous design until I asked some friends what they thought of it. Once I had received their feedback I realised that my work was far from finished. The main points I got were that it was too complex and over the top for a playing card. This was a big reality check for me because I thought my original design was flawless. This is why in-situ feedback is insanely important as it helped me avoid a poor outcome.

Where it started:

I used my previous card design as a base to rebuild my card. The three main things that I carried from this card to my new card were: 1. The Typeface 2. The Pips 3. The Royalty definers.

It was hard to let this original design go because I had already put so much time and effort into it. I was a huge fan of the gradient and bright colours, but they had to go. One tool I used more than I thought I would is the ruler tool. These markings where absolutely essential when trying to make the card symmetrical and even. One drawback to these lines is that they had a huge impact on the general speed of Photoshop. It began to get fairly awkward to perform small tasks without lagging out Photoshop.

Once I knew which details I would be taking forward, I decided to make a mind map to help visualise the design. This mind map contained many different topics and styles. To me, mind mapping is one of the best forms of Idea generation and movement.

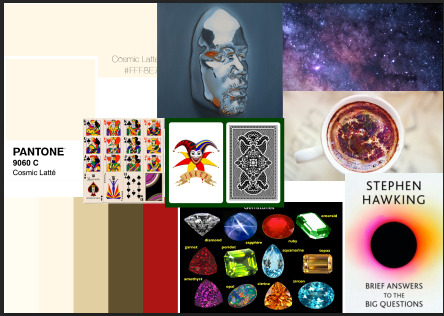

To commence my playing cards I started off with the debatably most important step of anything in design. This was the colour palette. I of course wanted to use the ‘Cosmic Latte’ colour as this what I based a majority the mood board off of.

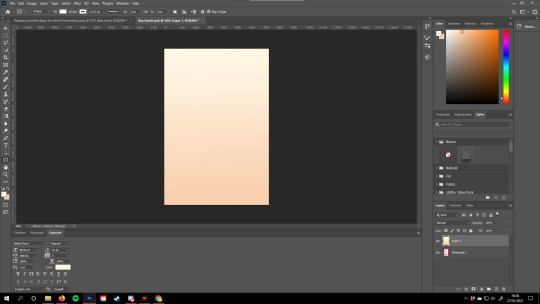

I hard to create the foundation to build my card onto. I started with the whole card as one colour, however I soon saw how bland and flat this looked. This made me turn to the gradient tool. At first I was happy with this outcome, but after rotating the canvas to see how it effected playability I soon realised that the difference in colour at each end of the card was too dramatic and could provide an unfair advantage.

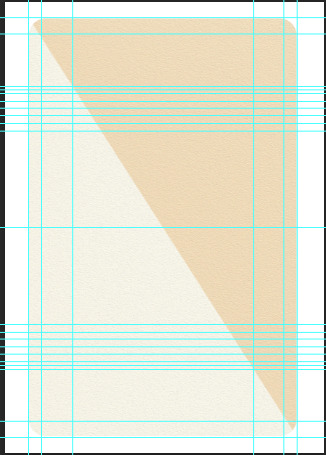

I tried playing around with the gradient tool until I found out about the angled pre-sets:

This formed this symmetrical stripe along the card using two different shades of Cosmic Latte and beige. I was much happier with this result. The next step from here was to start editing the texture of this background to add some depth. I used Photoshop’s in-built stylise function to add the ‘Oil Paint’ effect to the entire background. As I had used this effect before I knew that it created a ‘paper-like’ feel to the document, which is exactly what I wanted.

Although it is barely visible when far away from the card, I believe that it adds a much needed layer. The little details make all of the biggest differences.

From here, I wanted to start work on the borders and fonts. As I was using a previous font I did not have to spend ages scouring through the font websites to find one that would resonate with the card/ theme. The font had to be sharp and bold, while also being easily viable and not too overpowering.

I found this font on dafont.com and it ticked all of the criteria's. It was the perfect balance. The sharpness adds a degree of class and elegance to the card.

Picking a colour for the font and detailing was easy. I have been really appreciating earth tones recently, especially in these dark, wintery times. Brown is a great earthy tone that combines with beige well. It may sound weird but this colour scheme feels almost homely to me. It is a welcoming palette and works well in any environment. It was hard to decide whether to keep the letters in all capitals, or to break it down into capital and lowercase. The end product features all of the letters as capitals as I feel the uniform height and width of every letter supports the contours of this card much better than the lowercase would.

I used the guides to help line up these letters in their perfect corresponding place on the card. Symmetry is a very important feature on playing cards in my eyes.

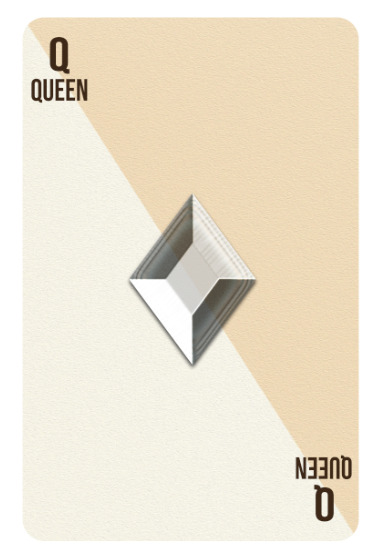

The next problem to tackle was where to put the pips. I wanted to keep this minimal and a playing card that I previously researched had the perfect solution. I was going to place a large, singular pip in the centre of the card, so that it was easy to see and did not obstruct the playability.

I was a big fan of how this looked, although I wanted a way to make this pip stand out a bit more from the background. I did this by duplicating the pip layer, removing the style, and making it black.

This result really excited me as it looks much better than I could’ve wanted. I love how these pips reflect what is underneath them. However, I soon realised that this method was flawed as it did not differentiate which colour the card was. This would have huge implications on playability and general use of the card.

To counter this, I changed the bottom pip to red using the paint bucket tool. This created this amazing gemstone style design, while also solving my issue of differentiation.

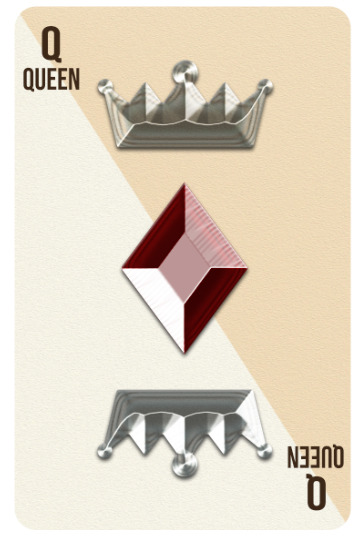

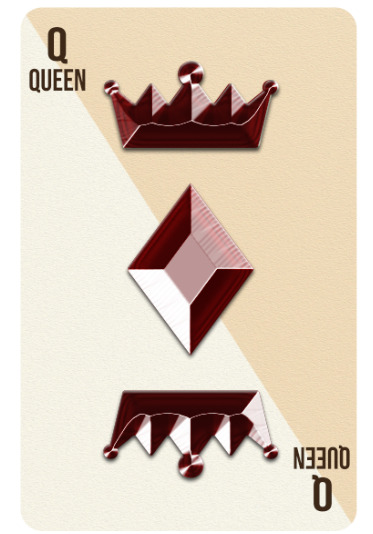

The next step was to find a way to show that it was a royalty card. I wanted to keep this along the theme of minimal, while also keeping it symmetrical. I used the designs I made previously within Illustrator as my template.

I applied the same style to these templates to create the same chrome effect as the pip. The next thing to do was to duplicate the layer and change it to red to support the rest of the design.

This really helped me see how well the red worked with the beige colour palette, as it was now more dominant.

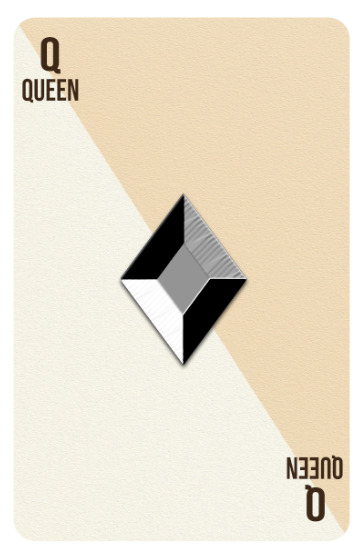

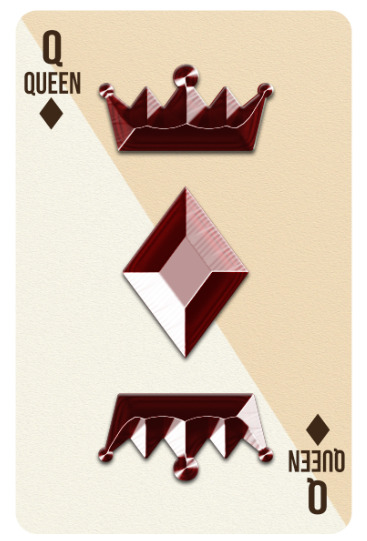

At this point I thought I was finished, so I sent it to a few friends to receive their input and verdict on my card. This is where I was helped massively, as an outsiders opinion is very beneficial in design. The main things they pointed out was that it wasn’t very easy to tell what the suit was. With this in mind I added a couple of small pips in the corners. This was a silly mistake on my end as I should have incorporated these from the beginning.

The final piece of input I received was to make the edges look less plain and to fill the space in a minimal way. I did this by adding a box around the card, this was inspired by traditional playing cards. This was done using the rectangle tool. I chose the rectangle to have no fill, and a stroke which was the same colour as the rest of the text.

I erased the rectangle where it met the text and pips to make sure it did not overlap anything and make it look untidy. One last thing I did to this rectangle was to add a white outer glow to add a minimal reflection of Kidmograph’s line work. This small addition helped to balance the tone difference between the brown line and beige card.

Overall I am very pleased with how this card turned out. I feel like I managed to portray my minimal design style and clean palette well. One slight problem I have with this card is that it is not for everyone. Although it looks clean and simple, many people might see this as lazy and unoriginal design, especially people that are very fond of traditional illustrative cards. I personally think this deck suits the 21st Century as it looks elegant and clean.

I created the rest of these cards in exactly the same way, however I changed the colours and shapes of the centre and outside pips. I also changed the colours of the royalty marks based off of which colour that suit is.

0 notes

Photo

New Post has been published on https://magzoso.com/tech/the-benefits-of-smart-technology-for-depression-and-anxiety/

The Benefits of Smart Technology for Depression and Anxiety

There are myriad exciting innovations that can help business owners reach peak performance.

December 7, 2019 7 min read

Opinions expressed by Entrepreneur contributors are their own.

Presented by

The following article is based on excerpts from Ben Angel’s book, Unstoppable: A 90-Day Plan to Biohack Your Mind and Body for Success. Buy it now from Amazon | Barnes and Noble | iBooks | IndieBound. And stay tuned for The Unstoppable Journal, the only journal of its kind based on neuroscience, psychology and biohacking to help you reach your goals. (Coming January 2020.)

Chronic stress can cost us more than just productivity and performance; it can trigger digestive symptoms, headaches, anger, anxiety, insomnia, sadness and depression. When you’re under chronic stress, you are more susceptible to severe viral infections, which is why you may find yourself getting sick more often than not. The problem is when we’re stressed out, we’ve switched on our fight-or-flight response. We lose our ability to access our prefrontal cortex, which is in control of rational and executive thinking.

So what can we do to take us to the next level of peak performance and productivity? Read on to learn about the biotechnology devices that I tested during my 90-day mission to become unstoppable, and see if they can help you gain that extra edge in business and life.

Brain Entertainment: Building a Better Brain With Braintap

I recently interviewed Dr. Patrick Porter, a leader in the field of brain entrainment and founder and inventor of Braintap, a wearable device that uses the benefits of light therapy, neurolinguistic programming and binaural beats to improve mood, memory and sleep. Braintap is a powerfully effective tool designed to help people achieve balanced brainwave states that enhance the production of all the necessary neurotransmitters needed for optimal function of body and mind.

“This exclusive, copyrighted technology has been extensively tested to create the perfect symmetry of sound, music and spoken word for the ultimate in brainwave training and relaxation, providing your mind and body with all the benefits of meditation without the disciplined effort,” states Dr. Porter.

Understanding how your brain works is the key to unlocking your potential. One area of interest of mine is brainwaves, which are created by synchronized electrical pulses from neurons communicating with one another and can be measured through an EEG. Light and sound can change our brainwaves to produce a different psychological state. In one study, brain wave entrainment usage was shown to produce average IQ increases of 23 percent. In cases where the IQ was lower than 100 to begin with, the average IQ increase was 33 points; a true game-changer.

Related: Smart Tech for Smarter Business

How to De-Stress in 30 Seconds Flat Using TouchPoints

Another device I experimented with for my book was TouchPoints. It’s a pair of watch-like looking devices that provide bilateral alternating stimulation tactile (BLAST). These devices have been shown to reduce excessive brainwaves and stress within 30 seconds. They were created by giving the user a gentle vibration that affects the brain and alters the body’s stress response to restore calm. This also relieves the associated body sensations that often accompany stress (i.e. stomachaches, headaches, or tightness in the chest).

Neuroscience has shown that this technology switches off your stress response without needing to meditate or stop what you’re doing to rationalize the situation. TouchPoints immediately eradicate that fight-or-flight response and brings you to a calmer state of being, creating new neural pathways to help de-stress. TouchPoints can even be preset to help you with cravings, calmness, anger, sleep, focus and performance.

Life-Changing Benefits of Meditation Using the Muse Headset

When you think about meditation in general, most of us don’t know if we’re doing it right. We don’t have any type of feedback to show us that we’re able to get our brain into a meditative state. We call this biofeedback, or real-time data that reflects how our brain is reacting to stimulus.

Research has shown us that the benefits of meditation are more relaxation, deeper focus and calmness, as well as increased gray matter density, reduced thinning of the prefrontal cortex, decreasing amygdala activity (associated with stress response) and increasing resilience. Basically, an overall beneficial change of the brain’s structure and function. When I discovered there was a device that could give me that necessary biofeedback, I jumped on the change to test it out.

The way that the Muse device works is via an EEG monitor built into its sci-fi looking headband, while you wear your own headphones attached to its app on your phone. It then transforms your active brain waves into sound waves. We then get biofeedback in the form of nature sounds of calm waves, all the way to a thunderstorm effect depending on what’s occurring in our brain. Birds will also chirp when you are lowering your brain waves to a neutral or calm frequency reassuring you that you are doing it correctly. So, practically speaking, it’s designed to train our minds to shift our focus from a busy, hyperactive state to one that’s calm and focused allowing us to get into the zone and be more productive and focused.

Scientific research found that after we get disrupted at work, it can take up to 20 minutes for us to get back into that zone, so using a device to retrain the brain is crucial. The Muse headset gives you that necessary biofeedback as it’s observing what your brain is doing while meditating. It makes you super aware of where your focus is or not and helps you refocus on your breathing and thoughts.

Taking Your Fitness to the Next Level With Halo Sport

Regardless of whether you want to succeed in business or career, you can’t optimize your mind without first optimizing your body. Fitness plays an integral role. The Halo Sport is an expensive-looking pair of headphones with softly pointed foam pads under the top band that touch your head, right above the part of your brain called the motor cortex. Based on 15 years of scientific research, the Halo Sport provides electrical stimulation during movement-based training helping build stronger, more optimized connections between your brain and muscles.

What excited me about using the Halo Sport was that it also received $60 Million funding from the Pentagon and garnered much praise from Olympic medalists, Major League Baseball and NBA and NFL players. I knew this was a device to take seriously. For 30 straight days, I electrically stimulated my brain 20 minutes before my CrossFit sessions designed by a friend of mine, Dean Haynes, an Olympic lifting and CrossFit coach from Adelaide, Australia. I realized that this noninvasive brain stimulation device could make my brain and body work harder and faster than it ever did before.

Where does Halo Sport fit in with obliterating fear and overcoming failure? Well, it’s pretty simple. It showed my brain what my body was capable of. It broke the old neural connections that said, “I can’t lift heavier or train harder than this,” and it also rewired neural pathways that helped me lift heavier in the gym even after I’d stopped using the device for several days. You can see my incredible results in my book, Unstoppable.

No matter where you are in your professional career, there are ways to help yourself out of depression and anxiety by taking the necessary steps to better health and wellness. What better way to prove your efforts than through scientifically proven devices that can give you the data you need to grow and change?

Related: 7 Steps to Peak Performance in Business and Life

Are you ready to become unstoppable?

Visit www.areyouunstoppable.com and take your FREE 60-second online quiz now. By answering a series of simple questions, my software will analyze your results and provide you with a comprehensive report that will indicate your identity type and lead you to the tools and tips you need to close that gap between who you are and who you could be. Take the quiz to get started!

0 notes

Text

All men are designers. All that we do, almost all the time, is design, for design is basic to all human activity. The planning and patterning of any act towards a desired, foreseeable end constitutes the design process. Any attempt to separate design, to make it a thing-by-itself, works counter to the inherent value, of design as the primary underlying matrix of life. Design is com- posing an epic poem, executing a mural, painting a masterpiece, writing a concerto. But design is also cleaning and reorganizing a desk drawer, pulling an impacted tooth, baking an apple pie, choosing sides for a back-lot baseball game, and educating a child. Design is the conscious effort to impose meaningful order. The order and delight we find in frost flowers on a window pane, in the hexagonal perfection of a honeycomb, in leaves, or in the architecture of a rose, reflect man's preoccupation with pattern, the constant attempt to understand an ever-changing, highly complex existence by imposing order on it - but these things are not the product of design. They possess only the order we ascribe to them. The reason we enjoy things in nature is that we see an economy of means, simplicity, elegance and an essential tightness in them. But they are not design. Though they have pattern, order, and beauty, they lack conscious intention. If we call them design, we artificially ascribe our own values to an accidental side issue. The streamlining of a trout's body is aesthetically satisfying to us, but to the trout it is a by-product of swimming efficiency. The aesthetically satisfying spiral growth pattern found in sunflowers, pineapples, pine cones, or the arrangement of leaves on a stem can be explained by the Fibonacci sequence (each member is the sum of the two previous members: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34 .. .), but the plant is only concerned with improving photosynthesis by exposing a maximum of its surface. Similarly, the beauty we find in the tail of a peacock, although no doubt even more attractive to a peahen, is the result of intra-specific selection (which, in the case cited, may even ultimately prove fatal to the species). Intent is also missing from the random order system of a pile of coins. If, however, we move the coins around and arrange them according to size and shape, we add the element of intent and produce some sort of symmetrical alignment. This sym- metrical order system is a favourite of small children, unusually primitive peoples, and some of the insane, because it is so easy to understand. Further shifting of the coins will produce an infinite number of asymmetrical arrangements which require a higher level of sophistication and greater participation on the part of the viewer to be understood and appreciated. While the aesthetic values of the symmetrical and asymmetrical designs differ, both can give ready satisfaction since the underlying intent is clear. Only marginal patterns (those lying in the threshold area between symmetry and asymmetry) fail to make the designer's intent clear. The ambiguity of these 'threshold cases' produces a feeling of unease in the viewer. But apart from these threshold cases there are an infinite number of possible satisfactory arrangements of the coins. Importantly, none of these is the one right answer, though some may seem better than others. Shoving coins around on a board is a design act in miniature because design as a problem-solving activity can never, by definition, yield the one right answer: it will always produce an infinite number of answers, some 'righter' and some 'wronger'. The Brightness' of any design solution will depend on the meaning with which we invest the arrangement. Design must be meaningful. And 'meaningful' replaces the semantically loaded noise of such expressions as 'beautiful1, 'ugly', 'cool', 'cute', 'disgusting', 'realistic', 'obscure', 'abstract', and 'nice', labels convenient to a bankrupt mind when con- fronted by Picasso's 'Guernica', Frank Lloyd Wright's Falling-f water, Beethoven's Eroica, Stravinsky's Le Sacre du printemps, Joyce's Finnegans Wake. In all of these we respond to that which has meaning. The mode of action by which a design fulfils its purpose is its function. 'Form follows function', Louis Sullivan's battle cry of the i88os and 18905, was followed by Frank Lloyd Wright's 'Form and function are one'. But semantically, all the statements from Horatio Greenough to the German Bauhaus are meaningless. The concept that what works well will of necessity look well has been the lame excuse for all the sterile, operating-room-like furniture and implements of the twenties and thirties. A dining table of the period might have a top, well proportioned in glisten- ing white marble, the legs carefully nurtured for maximum strength with minimum materials in gleaming stainless steel. And the first reaction on encountering such a table is to lie down on it and have your appendix extracted. Nothing about the table says: 'Dine off me.' Le style internationaland die neue Sachlichkeit have let us down rather badly in terms of human value. Le Corbusier's house as la machine a habiter and the packing-crate houses evolved in the Dutch De Stijl movement reflect a perversion of aesthetics and utility. 'Should I design it to be functional,' the students say, 'or to be aesthetically pleasing?' This is the most heard, the most understandable, and the most mixed-up question in design today. 'Do you want it to look good, or to work ?' Barricades erected between what are really just two of the many aspects of function. It is all quite simple: aesthetic value is an inherent part of function. A simple diagram will show the dynamic actions and relationships that make up the function complex: It is now possible to go through the six parts of the function complex (above) and to define every one of its aspects. METHOD: The interaction of tools, processes, and materials. An honest use of materials, never making the material seem that which it is not, is good method. Materials and tools must be used optimally, never using one material where another can do the job less expensively and/or more efficiently. The steel beam in a house, painted a fake wood grain; the moulded plastic bottle designed to look like expensive blown glass; the 1967 New Eng- land cobbler's bench reproduction ('worm holes $i extra') dragged into a twentieth-century living room to provide dubious footing for Martini glass and ash tray: these are all perversions of materials, tools, and processes. And this discipline of using a suitable method extends naturally to the field of the fine arts as well. Alexander Calder's 'The Horse', a compelling sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, was shaped by the particular material in which it was conceived. Calder decided that boxwood would give him the specific colour and texture he desired in his sculpture. But boxwood comes only in rather narrow planks of small sizes. (It is for this reason that it tradition- ally has been used in the making of small boxes: hence its name.) The only way he could make a fair-sized piece of sculpture out of a wood that only comes in small pieces was to interlock them somewhat in the manner of a child's toy. The Horse', then, is a piece of sculpture, the aesthetic of which was largely determined by method. For the final execution at the Museum of Modern Art Calder chose to use thin slats of walnut, a wood similar in texture. When early Swedish settlers in what is now Delaware decided to build, they had at their disposal trees and axes. The material was a round tree trunk, the tool an axe, and the process a simple kerf cut into the log. The inevitable result of this combination of tools, materials, and process is a log cabin. From the log cabin in the Delaware Valley of 1680 to Paolo Soleri's desert home in twentieth-century Arizona is no jump at all. Soleri's house is as much the inevitable result of tools, materials, and processes as is the log cabin. The peculiar viscosity of the desert sand where Soleri built his home made his unique method possible. Selecting a mound of desert sand, Soleri criss-crossed it with V-shaped channels cut into the sand, making a pattern somewhat like the ribs of a whale. Then he poured concrete in the channels, forming, when set, the roof- beams of the house-to-be. He added a concrete skin for the roof and bulldozed the sand out from underneath to create the living space itself. He then completed the structure by setting in car windows garnered from automobile junkyards. Soleri's creative use of tools, materials, and processes was a tour deforce that gave us a radically new building method. Dow Chemical's 'self-generating' styrofoam dome is the pro- duct of another radical approach to building methods. The foundation of the building can be a 12-inch-high circular retaining wall. To this wall a 4-inch wide strip of styrofoam is attached which raises as it goes around the wall from zero to 4 inches in height, forming the base for the spiral dome. On the ground in Paolo Soleri: Carved earth form for the original drafting room and interior of the ceramics workshop. Photos by Stuart Weiner. the centre, motorized equipment operates two spinning booms, one with an operator and the other holding a welding machine. The booms move around, somewhat like a compass drawing a circle, and they rise with a spiralling motion at about 30 feet a minute. Gradually they move in towards the centre. A man sit- ting in the saddle feeds an 'endless' 4 x 4-inch strip of styrofoam into the welding machine, which heat-welds it to the previously hand-laid styrofoam. As the feeding mechanism follows its circular, rising, but ever-diminishing diameter path, this spiral process creates the dome. Finally, a hole 36 inches in diameter is left in the top, through which man, mast, and movement arm can be re- moved. The hole is then closed with a clear plastic pop-in bubble or a vent. At this point the structure is translucent, soft, but still entirely without doors or windows. The doors and windows are then cut (with a minimum of effort; in fact the structure is still so soft that openings could be cut with one's fingernail), and the structure is sprayed inside and out with latex-modified concrete. The dome is ultra-lightweight, is secured to withstand high wind speeds and great snow loads, is vermin-proof, and inexpensive. Several of these 54-foot-diameter domes can be easily joined together into a cluster. All these building methods demonstrate the elegance of solution possible with a creative interaction of tools, materials, and processes. USE: 'Does it work?' A vitamin bottle should dispense pills singly. An ink bottle should not tip over. A plastic-film package covering sliced pastrami should withstand boiling water. As in any reasonably conducted home, alarm-clocks seldom travel through the air at speeds approaching five hundred miles per hour, 'streamlining' clocks is out of place. Will a cigarette lighter designed like the tail fin of an automobile (the design of that auto- mobile was copied from a pursuit plane of the Korean War) give more efficient service? Look at some hammers: they are all different in weight, material, and form. The sculptor's mallet is fully round, permitting constant rotation in the hand. The jeweller's chasing hammer is a precision instrument used for fine work on metal. The prospector's pick is delicately balanced to add to the swing of his arm when cracking rocks. The ball-point pen with a fake polyethylene orchid surrounded by fake styrene carrot leaves sprouting out of its top, on the other hand, is a tawdry perversion of design for use. But the results of the introduction of a new device are never predictable. In the case of the automobile, a fine irony developed. One of the earliest criticisms of the car was that, unlike 'old Dobbin', it didn't have the sense 'to find its way home' whenever its owner was incapacitated by an evening of genteel drinking. No one foresaw that mass acceptance of the car would put the American bedroom on wheels, offering everyone a new place to copulate (and privacy from supervision by parents and spouses). Nobody expected the car to accelerate our mobility, thereby creating the exurbant sprawl and the dormitory suburbs that strangle our larger cities; or to sanction the killing of fifty thou- sand people per annum, brutalising us and making it possible, as Philip Wylie says 'to see babies with their jaws ripped off on the corner of Maine and Maple'; or to dislocate our societal groupings, thus contributing to our alienation; and to put every yut, yahoo, and prickamouse from sixteen to sixty in permanent hock to the tune of $80 a month. In the middle forties, no one foresaw that, with the primary use function of the automobile solved, it would emerge as a combination status symbol and disposable, chrome-plated codpiece. But two greater ironies were to follow. In the early sixties, when people began to fly more, and to rent standard cars at their destination, the businessman's clients no longer saw the car he owned and therefore could not judge his 'style of life' by it. Most of Detroit's Baroque exuberance sub- sided, and the automobile again came closer to being a transportation device. Money earmarked for status demonstration was now spent on boats, colour television sets, and other ephemera. The last irony is still to come: with carbon monoxide fumes poisoning our atmosphere, the electric car, driven at low speeds and with a cruising range of less than one hundred miles, reminiscent of the turn of the century, may soon make an anachronistic comeback. Anachronistic because the days of individual transportation devices are numbered. The automobile gives us a typical case history of seventy years of the perversion of design for use. NEED: Much recent design has satisfied only evanescent wants and desires, while the genuine needs of man have often been neglected by the designer. The economic, psychological, spiritual, technological, and intellectual needs of a human being are usually more difficult and less profitable to satisfy than the carefully engineered and manipulated 'wants' inculcated by fad and fashion. People seem to prefer the ornate to the plain as they prefer day-dreaming to thinking and mysticism to rationalism. As they seek crowd pleasures and choose widely travelled roads rather than solitude and lonely paths, they seem to feel a sense of security in crowds and crowdedness. Horror vacui is horror of inner as well as outer vacuum. The need for security-through-identity has been perverted into role-playing. The consumer, unable or unwilling to live a strenuous life, can now act out the role by appearing caparisoned in Naugahyde boots, pseudo-military uniforms, voyageur's shirts, little fur jackets, and all the other outward trappings of Davy Crockett, Foreign Legionnaires, and Cossack Hetmans. (The apotheosis of the ridiculous: a 'be- your-own-Paul-Bunyan-kit, beard included', neglecting the fact that Paul Bunyan is the imaginary creature of an advertising firm early in this century.) The furry parkas and elk-hide boots are obviously only role- playing devices, since climatic control makes their real use redundant. A short ten months after the Scott Paper Company introduced disposable paper dresses for QQC, it was possible to buy throwaway paper dresses ranging from $20 to $149.50. With increased consumption, the price of the 99c dress could have dropped to 40c. And a 40c paper dress is a good idea. Typically, industry perverted the idea and chose to ignore an important need- fulfilling function of the design: disposable dresses inexpensive enough to make disposability economically feasible for the consumer. Greatly accelerated technological change has been used to create technological obsolescence. This year's product often incorporates enough technical changes to make it really superior to last year's offering. The economy of the market place, however, is still geared to a static philosophy of purchasing-owning' rather than a dynamic one of 'leasing-using', and price policy has not resulted in lowered consumer cost. If a television set, for instance, is to be an every-year affair, rather than a once- in-a- lifetime purchase, the price must reflect it. Instead, the real values of real things have been driven out by false values of false things, a sort of Gresham's Law of Design. As an attitude, 'Let them eat cake' has been thought of as a manufacturer's basic right. And by now people, no longer 'turned on' by a loaf of bread, can differentiate only between frostings. Our profit-oriented and consumer-oriented Western society has become so over specialised that few people experience the pleasures and benefits of full life, and many never participate in even the most modest forms of creative activity which might help to keep their sensory and intellectual faculties alive. Members of a 'civilised' community or nation depend on the hands, brains, and imaginations of experts. But however well trained these experts may be, unless they have a sense of ethical, intellectual, and artistic responsibility, then morality and an intelligent, 'beautiful', and elegant quality of life will suffer in astronomical proportions under our present-day system of mass production and private capital. TELESIS: 'The deliberate, purposeful utilisation of the processes of nature and society to obtain particular goals' (American College Dictionary, 1961). The telesic content of a design must reflect the times and conditions that have given rise to it, and must fit in with the general human socio-economic order in which it is to operate. The uncertainties and the new and complex pressures in our society make many people feel that the most logical way to regain lost values is to go out and buy Early American furniture, put a hooked rug on the floor, buy ready-made phoney ancestor portraits, and hang a flint-lock rifle over the fireplace. The gas-light so popular in our subdivisions is a dangerous and senseless anachronism that only reflects an insecure striving for the 'good old days' by consumer and designer alike. Our twenty-year love affair with things Japanese - Zen Buddhism, the architecture of the Ise Shrine and Katsura Imperial Palace, haiku poetry, Hiroshige and Hokusai block-prints, the music of koto and samisen, lanterns and sake sets, green tea liqueur and sukiyaki and tempura - has triggered an intemperate demand by consumers who disregard telesic aptness. By now it is obvious that our interest in things Japanese is not just a passing fad or fashion but rather the result of a major cultural confrontation. As Japan was shut off for nearly two hundred years from the Western world under the Tokugawa Shogunate, its cultural expressions flourished in a pure (although somewhat inbred) form in the imperial cities of Kyoto and Edo (now Tokyo). The Western world's response to an in-depth knowledge of things Japanese is comparable only to the European reaction to things classical, which we are now pleased to call the Renaissance. Nonetheless, it is not possible to translate things from one culture to another. The floors of traditional Japanese homes are covered by floor mats. These mats are 3x6 feet in size and consist of rice straw closely packed inside a cover of woven rush. The long sides are bound with black linen tape. While tatami mats impose a module (homes are spoken of as six-, eight-, or twelve-mat homes), their primary purposes are to absorb sounds and to act as a sort of wall-to-wall vacuum cleaner which filters particles of dirt through the woven surface and retains them in the inner core of rice straw. Periodically these mats (and the dirt within them) are discarded, and new ones are installed. Japanese feet encased in clean, sock- like tabi (the sandal-like street shoe, or geta, having been left at the door) are also designed to fit in with this system. Western- style leather-soled shoes and spike heels would destroy the surface of the mats and also carry much more dirt into the house. The increasing use of regular shoes and industrial precipitation make the use of tatami difficult enough in Japan and absolutely ridiculous in the United States, where high cost makes periodic disposal and reinstallation ruinously expensive. But a tatami-covered floor is only part of the larger design system of the Japanese house. Fragile, sliding paper walls and tatami give the house definite and significant acoustical proper- ties that have influenced the design and development of musical instruments and even the melodic structure of Japanese speech, poetry, and drama. A piano, designed for the reverberating insulated walls and floors of Western homes and concert halls, cannot be introduced into a Japanese home without reducing the brilliance of a Rachmaninoff concerto to a shrill cacophony. Similarly, the fragile quality of a Japanese samisen cannot be fully appreciated in the reverberating box that constitutes the American house. Americans who try to couple a Japanese interior with an American living experience in their search for exotica find that elements cannot be ripped out of their telesic context with impunity. ASSOCIATION: Our psychological conditioning, often going back to earliest childhood memories, comes into play and pre- disposes us, or provides us with antipathy against a given value. Increased consumer resistance in many product areas testifies to design neglect of the associational aspect of the function complex. After two decades, the television-set industry, for instance, has not yet resolved the question of whether a television set should carry the associational values of a piece of furniture (a lacquered mah-jongg chest of the Ming Dynasty) or of technical equipment (a portable tube tester). Television receivers that carry new associations (sets for children's rooms in bright colours and materials, enhanced by tactilely pleasant but non-working controls and pre-set for given times and channels, clip-on swivel sets for hospital beds, etc., etc.) might not only clear up the astoundingly large back inventory of sets in warehouses, but also create new markets. And what shape is most appropriate to a vitamin bottle: a candy jar of the Gay Nineties, a perfume bottle, or a 'Danish modern' style salt shaker ? The response of many designers has been like that so unsuccessfully practised by Hollywood: the public has been pictured as totally unsophisticated, possessed of neither taste nor discrimination. A picture emerges of a moral weakling with an IQ of about 70, ready to accept whatever specious values the unholy trinity of Motivation Research, Market Analysis, and Sales have decided is good for him. In short, the associational values of design have degenerated to the lowest common denominator, determined more by inspired guesswork and piebald graphic charts rather than by the genuinely felt wants of the consumer. Many products already successfully embody values of high associational content, either accidentally or 'by design'. The Sucaryl bottle by Raymond Loewy Associates for Abbott Laboratories communicates both table elegance and sweetening agent without any suggestion of being medicine-like. The Lettera 22 portable typewriter by Olivetti establishes an immediate aura of refined elegance, precision, extreme portability, and businesslike efficiency, while its two-toned carrying case of canvas and leather connotes 'all- climate-proof. Abstract values can be communicated directly to everyone, and this can be simply demonstrated. If the reader is asked to choose which one of the figures below he would rather call Takete or Maluma (both are words devoid of all meaning in any known language), he will easily call the one on the right Takete (W. Koehler, Gestalt Psychology), Many associational values are really universal, providing for unconscious, deep-seated drives and compulsions. Even totally meaningless sounds and shapes can, as demonstrated, mean the same thing to all of us. The unconscious relationship between spectator expectation and the configuration of the object can be experimented with and manipulated. This will not only enhance the 'chair-ness' of a chair, for instance, but also load it with associational values of, say, elegance, formality, portability, or what-have-you. AESTHETICS: Here dwells the traditionally bearded artist, mythological figure, equipped with sandals, mistress, garret, and easel, pursuing his dream-shrouded designs. The cloud of mystery surrounding aesthetics can (and should be) dispelled. The dictionary definition, 'a theory of the beautiful, in taste and Art' leaves us not much better off than before. Nonetheless we know that aesthetics is a tool, one of the most important ones in the repertory of the designer, a tool that helps in shaping his forms and colours into entities that move us, please us, and are beautiful, exciting, filled with delight, meaningful. Because there is no ready yardstick for the analysis of aesthetics, it is simply considered to be a personal expression fraught with mystery and surrounded with nonsense. We 'know what we like' or dislike and let it go at that. Artists themselves begin to look at their productions as auto-therapeutic devices of self- expression, confuse licence and liberty, and forsake all discipline. They are often unable to agree on the various elements and attributes of design aesthetics. If we contrast the 'Last Supper' by Leonardo da Vinci with an ordinary piece of wallboard, we will understand how both operate in the area of aesthetics. In the work of so-called 'pure' art, the main job is to operate on a level of inspiration, delight, beauty, catharsis ... in short, to serve as a propagandistic communications device for the Holy Church at a time when a largely pre-literate population \vas exposed to a few non-verbal stimuli. But the 'Last Supper' also had to fill the other requirements of function; aside from the spiritual, its use was to cover a wall. In terms of method it had to reflect the material (pigment and vehicle), tools (brushes and painting knives), and processes (individualistic brushwork) employed by Leonardo. It had to fulfil the human need for spiritual satisfaction. And it had to work on the associational and telesic plane, providing reference points from the Bible. Finally, it had to make 30 identification through association easier for the beholder through such clichés as the racial type, garb, and posture of the Saviour. 'The Last Supper', by Leonardo da Vinci. Earlier 'Last Supper' versions, painted during the sixth and seventh centuries, saw Christ lying or reclining in the place of honour. For nearly a thousand years, the well- mannered did not sit at the table. Leonardo da Vinci disregarded the reclining position followed by earlier civilisations and painters for Jesus and the Disciples. To make the 'Last Supper' acceptable to Italians of his time, on an associational plane, Leonardo sat the crowd around the last supper table on chairs or benches in the proper positions of his (Leonardo's) time. Unfortunately the scriptural account of St John resting his head on the Saviour's bosom presented an unsolvable positioning problem to the artist, once everybody was seated according to the Renaissance custom. On the other hand, the primary use of wallboard is to cover a wall. But an increased choice of textures and colours applied by the factory shows that it, too, must fulfil the aesthetic aspect of function. No one argues that in a great work of art such as the 'Last Supper', prime functional emphasis is aesthetic, with use (to cover a wall) subsidiary. The main job of wallboard is its use in covering a wall, and the aesthetic assumes a highly subsidiary position. But both examples must operate in all six areas of the function complex. Designers often attempt to go beyond the primary functional requirements of method, use, need, telesis, association, and aesthetics; they strive for a more concise statement: precision, simplicity. In a statement so conceived, we find a degree of aesthetic satisfaction comparable to that found in the logarithmic spiral of a chambered nautilus, the ease of a seagull's flight, the strength of a gnarled tree trunk, the colour of a sunset. The particular satisfaction derived from the simplicity of a thing can be called elegance. When we speak of an 'elegant' solution, we refer to something consciously evolved by men which reduces the complex to the simple: Euclid's Proof that the number of primes is infinite, from the field of mathematics, will serve: 'Primes' are numbers which are not divisible, like 3, 17, 23, etc. One would imagine as we get higher in the numerical series, primes would get rarer, crowded out by the ever-increasing products of small numbers, and that we would finally arrive at a very high number which would be the highest prime, the last numerical virgin. Euclid's Proof demonstrates in a simple and elegant way that this is not true and that to whatever astronomical regions we ascend, we shall always find numbers which are not the product of smaller ones but are generated by immaculate conceptions, as it were. Here is the proof: assume that P is the hypothetically highest prime; then imagine a number equal to 1 x 2 x 3 x 4 ... x P. This number is expressed by the numerical symbol (P!). Now add to it 1: (P! + 1). This number is obviously not divisible by P or any number less than P (because they are all contained in (P!)); hence (P! + 1) is either a prime higher than P or it contains a prime factor higher than P . . . Q.E.D. The deep satisfaction evoked by this proof is aesthetic as well as intellectual: a type of enchantment with the near-perfect.

0 notes