#alice through the looking glass 1966

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I want the 1966 Alice through the looking glass to get popular so there can be minor passive aggressive discourse about how people only like the movie for the "clowncore" character like what happened with 1976's "The Adventures of Buratino" in 2021

#i actually made a few people watch this movie because of an edit of this guy. one of the jabberwock too#alice through the looking glass 1966#alice through the looking glass#alice's adventures in wonderland#the adventures of buratino#alice in wonderland#clowncore#jester core#jester#clownblr

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

26K notes

·

View notes

Text

Thinking of an alice through the looking glass adaptation with these two

#i actually think about it alot#they're the inspo for two of my characters ndcnndnvneg#alice through the looking glass#alice through the looking glass 1966#alice through the looking glass 2016#alice's adventures in wonderland#alice in wonderland

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

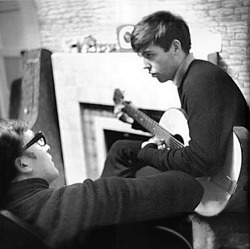

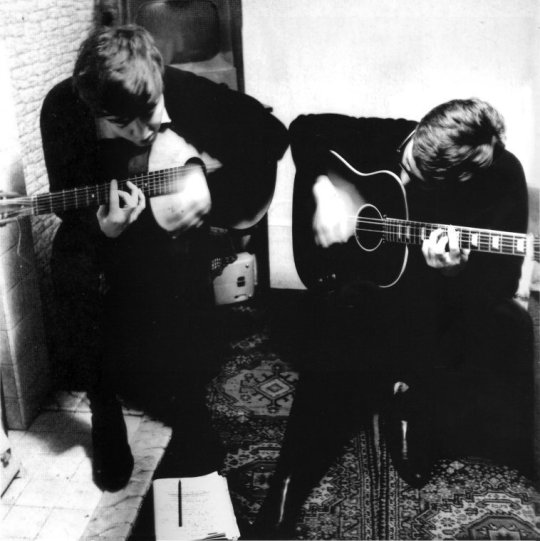

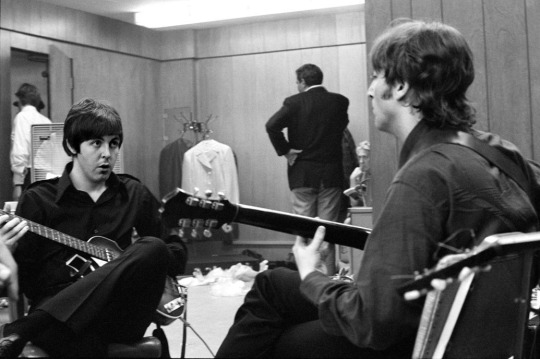

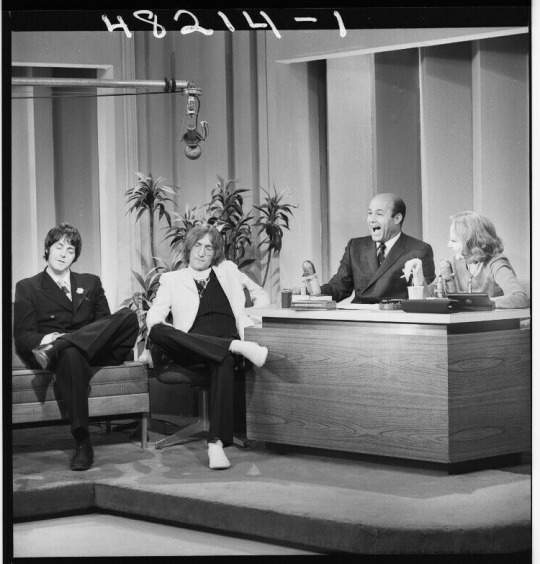

'I look in the mirror'

At the Cavern, 1963, photo by Michael Ward

Photo by Mike McCartney

August 13, 1966, photo by Bob Bonis

We wrote with two guitars, John and I. And, as I’ve mentioned previously, the joy of that was that I was left-handed while he was right handed, so I was looking in a mirror and he was looking in a mirror. We would always tune up, have a ciggie, drink a cup of tea, start playing some stuff, look for an idea. Normally, one or the other of us would arrive with a fragment of a song. ‘Please Please Me’ was a John idea. John liked the double meaning of ‘please’. Yeah, ‘please’ is, you know, pretty please. ‘Please have intercourse with me. So, pretty please, have intercourse with me, I beg you to have intercourse with me.’ He liked that, and I liked that he liked that. This was the kind of thing we’d see in each other, the kind of thing in which we were matched up. We were in sync.

(Paul McCartney, about Please Please Me in The Lyrics, 2021)

gifs by javelinbk

A lot of what we had going for us was that we were both good at noticing the stuff that just pops up, and grabbing it. And the other thing is that John and I had each other. If he was sort of stuck for a line, I could finish it. If I was stuck for somewhere to go, he could make a suggestion. We could suggest the way out of the maze to each other, which was a very handy thing to have. We inspired each other.

(Paul McCartney, about Eight Days A Week in The Lyrics, 2021)

gifs by nikidontsurf

When John and I met, the first year of our friendship was spent talking about these cover versions, the records we loved, and then playing them again and again. As we got to know each other, we practised these various covers until one day the conversation went, ‘You know, I’ve written one or two songs.’ And he said, ‘Yeah, so have I.’ That gave us something in common that was itself wholly uncommon. I went to a school of a thousand boys and I’d never met anyone who said he’d written a song. Mine were just in my head. So were John’s. We took each other by surprise. And then the logical extension was, ‘Well, maybe we could write one together.’ So that’s how we started. And we became versions of each other.

(Paul McCartney, about The Other Me in The Lyrics, 2021)

gifs by stewy

Q: "Can I ask you about Lewis Carroll?" A: "Oh, Lewis Carroll. I always admit to that because I love 'Alice In Wonderland' and 'Alice Through The Looking Glass.' But I didn't even know he'd written anything else. I was that ignorant. I just happened to get those for birthday presents as a child and liked them. And I usually read those two about once a year, because I still like them."

(John Lennon, June 16, 1965, interview for BBC)

Paul McCartney in his garden at Cavendish Avenue, 7; photo by Barry Lategan (for Observer 'What Makes A Man Stylish?', July 1968)

I think of the imagined world of Lewis Carroll [Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There] that John and I both loved so much.

(Paul McCartney, about I’ll Get You in The Lyrics, 2021)

We’d been together so much that if you had a question, we would both pretty much come up with the same answer. [about their hitchhike to Spain by way of Paris] <…> It’s a bit crude, but it’s fair to say that, in general, I’d had a good life and John hadn’t. His life had been tougher, and he had to develop a harder shell than I did. He was quite a cynical guy but, as they say, with a heart of gold. A big softy, but his shield was hard. So that was very good for the two of us. Opposites attract. I could calm him down, and he could fire me up. We could see things in each other that the other needed to be complete.

(Paul McCartney about Ticket To Ride in The Lyrics, 2021)

youtube

Sometimes I look in the mirror Is nobody there? But I just keep on staring and staring No Can it be? Can it be? Can it be? And if I look in the mirror And nobody´s there But I just keep on staring, and staring No Is it me? Is it me? Is it me?

(John Lennon, circa 1977)

+ this

#'when making art we create a mirror in which someone may see their own hidden reflection' (Rick Rubin)#john lennon#paul mccartney#john and paul#mirror mirror (on the wall)#the songs we were singing#the nerk twins#Youtube#please please me#i'll get you#eight days a week#the other me#i've got a feeling#interview: paul#interview: john#lewis carroll#get back#peter jackson#the beatles#george harrison#ringo star

464 notes

·

View notes

Text

Many gay men will be able to relate to Bob Mackie’s early life. His father had no interest in him, and his mother handed him off to his grandmother to raise. As a boy, he preferred drawing alone in his room over playing sports outside with other boys.

In high school in a Los Angeles suburb, he designed costumes for talent shows. He met Marianne Wolford and asked her to the senior prom. She would get pregnant, and they got married in 1960.

Marianne became a professional dancer and actress (changing her name to Lulu Porter). While she traveled for her work, Bob attended design school. In an interview, he described the guilt he felt, realizing he was gay and deceiving his wife. He didn’t want to lead a double life, so he told Lulu the truth. They divorced in 1963 but remained friends.

While attending Chouinard Art Institute in Westlake, Mackie was offered the opportunity to be a sketch artist for French designer Jean Louis. He worked with Louis on the design for Marilyn Monroe’s iconic “nude” dress, which she wore singing “Happy Birthday” to President Kennedy in 1962. (Mackie would late design “nude” gowns for Mitzi Gaynor and Cher - among others).

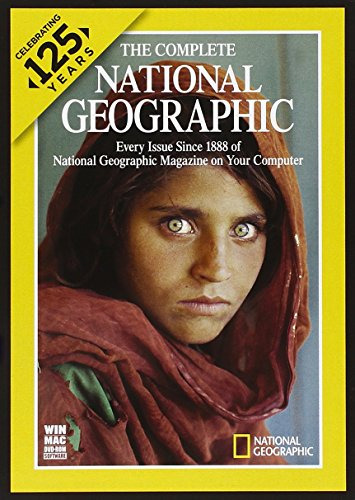

Mackie left Chouinard without graduating when he was offered a job costume sketching at Paramount Studios. There he worked with famed costume designer Edith Head and he became an assistant to costume designer Ray Aghayan. They would become lifelong romantic partners. Together they would win an Emmy Award for the TV movie “Alice Through the Looking Glass” (1966). (Aghayan died from natural causes in 2011.)

In 1967, Mackie was asked to design costumes for actress Mitzi Gaynor’s show in Las Vegas. This led to his work on her 8 TV specials - winning Emmys twice for his designs.

His work on Mitzi’s Vegas show led to Bob being hired by Carol Burnett for her variety show in 1967. His comic genius helped her to define and enhance her characters - never more so than her iconic Scarlett curtain dress. Over 11 seasons and 269 episodes, Mackie designed 16,000 costumes for Carol, her costars, guests, and backup dancers.

How could Mackie top that? Designing for Cher, of course. He worked on her TV show with Sonny, her solo show, numerous stage shows, and Academy Award appearances.

His work with Cher led to Mackie designing for British icon Elton John’s, including designs for his sequence studded Dodgers uniform and his infamous Donald Duck outfit.

In his career, Mackie has been nominated for 3 Oscars, nominated for 32 Emmys (winning 9 times); and winning a Tony for Broadway musical The Cher Show.

Bob Mackie’s son Robin died in 1993 due to an AIDS-related disease (from intravenous drug use). At the time, Bob and his former wife did not know Robin was a father himself. Years later, Bob’s granddaughter reached out to him. Eventually, Bob and his former wife Lulu developed strong bonds with their new extended family.

Bob Mackie’s designs, costumes, and gowns have been worn by a long line of glamorous stars including: Judy Garland, Lucille Ball, Raquel Welch, Diahann Carroll, Ann-Margret, Tina Turner, Diana Ross, Goldie Hawn, Julie Andrews, Liza Minnelli, Bette Midler, Bernadette Peters, Madonna, Pink, Miley Cyrus, and Zendaya.

“Bob Mackie: Naked Illusion”, a documentary about Mackie was released in 2025. It meanders and is poorly edited. It’s is a huge disappointment. Mackie deserves better.

#gay icons#Bob Mackie#costume designs#Carol Burnett#Cher#Marilyn Monroe#life partner Ray Aghayan#nude dresses#glamorous stars#elton john

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Collection of Alice in Wonderland media

American McGee’s Alice (2000 video game)

Alice in Wonderland (1933)

Alice in Wonderland - Nintendo DS (2010 video game)

Alice in Wonderland (2010 movie)

Alice in Wonderland (1951)

Habromania (2024 video game)

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1972)

Alice in Wonderland (1985)

Jon Svankmajer’s Alice (1988)

Alice in Wonderland (1999)

Adventures in Wonderland (1992)

Alice By Heart (2012 musical)

Alice in Borderland (2010 manga)

Once Upon a Time in Wonderland (2013 tv show)

Alice in Wonderland (1886)

Dreamchild (1985)

Alice in Wonderland by GoodTimes Entertainment - PC (1995 video game)

Europe’s Living Classics - Alice's Adventures in Wonderland - PC (1995 video game)

Alice in Wonderland- Gameboy Color (2000 video game)

alice is dead: hearts and diamonds (2022 video game)

Lexis Numerique’s Alice in Wonderland (2000 video game)

Ally's Adventure: Through The Glass (2002 video game)

"Alice's Adventures in Wonderland" by Joriko Interactive (2000 video game)

Wonderland (1990)

Alice in Wonderland by Glow Zone Interactive (1997)

Alice In Wonderland - commadore 64 (1985)

ALICE IN DREAMS (2024 analog horror series) (Tw for gore)

Wonderland Dreams (2023 art exhibit)

Wonderland (2011 musical)

Wonder.land (2015 musical)

Alice in Wonderland (1983 Broadcast Play)

Fushigi no Kuni no Alice (1983 Japanese tv show)

Alice in Cyberland - PS1 (1996)

Clamp in Wonderland

Miyuki-chan in Wonderland (1995 manga)

Alice in Wonderland (1995 Anime)

Alice in Wonderland (1988 Australian animated film)

Bideo Anime Ehon: Alice in Wonderland (1988; Walkers Company)

Yoiko Anime Video Meisaku Dowa: Alice in Wonderland (2000; Keep)

Manga Fairy Tales of the World (1976) ep. 62: “Alice in Wonderland” (1977)

Eternal Alice (2004 Manga)

Alice & Zoroku (2017 anime)

Alice SOS (1998)

Pandora Hearts (2006)

Alice in Wonderland (2015 Anime series)

Alice in Dreamland (2015 film)

Hitobashira Arisu/Alice of Human sacrifice (2008 Vocaloid song)

Alice in Musicland (2012 Vocaloid project)

Alice in Wonderland by Sakura Kinoshita (2006)

Disney Manga: Alice in Wonderland by Jun Abe (2009)

Alice in Wonderland Anthology (2012 Manga)

Alice ∞ Wonderland (2006 Manga)

Are You Alice? (2013 Manga)

I Am Alice: Body Swap in Wonderland (2012 manga)

Boy Alice in Wonderland (1993 manga)

Alice in Murderland ( 2010 slasher)

Alice in Murderland (2014 manga)

Wonderland (2015 manga)

Alice in the Country of Hearts (2007 Visual Novel)

Alisa V Strane Chudes (1981 Animated Film) ( @samaeljigoku thanks for the recommendation)

Alice in Wonderland (1903 movie)

Alice in Wonderland (1915 film)

Alice in Wonderland (1931 film)

Alice Through the Looking Glass (1973)

Alice in Wonderland (Vocaloid Song)

Nel Mondo Dil Alice (1974)

Children’s theater company: Alice in Wonderland (1982)

Alice Through the Looking Glass (1966)

Source:

Curiouser Archive

Another Internet Nerd

Alice in Anime Wonderland

A Journey Through Cinema

Phantomwise (channel)

@still-she-haunts-me-phantomwise

extras:

That one episode of Hello Kitty

That one episode of OHSHC

That one. Episode of Black Butler

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Alice in Wonderland" Actresses of the Screen, Youngest to Oldest

Not a complete list of actresses who have played Alice, but enough for me. The ages I've listed are their ages at the time of filming, not at the time each version was released.

*Kristyna Kohoutová, Něco z Alenky, 1988 (age 7)

*Natalie Gregory, Irwin Allen's Alice in Wonderland, 1985 (age 9)

*Sarah Sutton, BBC Alice Through the Looking Glass, 1973 (age 11)

*Kathryn Beaumont (voice), Disney's animated Alice in Wonderland, 1951 (age 10-12)

*Elisabeth Harnois, Adventures in Wonderland, 1992 (age 12)

*Annie Enneking, Children's Theatre Company Alice in Wonderland, 1982 (age 13)

*Giselle Andrews, Anglia TV Alice in Wonderland, 1985 (age 13)

*Tina Majorino, NBC Alice in Wonderland, 1999 (age 13)

*Anne-Marie Mallik, Jonathan Miller's Alice in Wonderland, 1966 (age 14)

*Libby Rue (voice), Alice's Wonderland Bakery, 2022 (age 14)

*Viola Savoy, W.W. Young's silent Alice in Wonderland, 1915 (age 15)

*Fiona Fullerton, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, 1973 (age 15)

*Ruth Gilbert, Metropolitan Studios' Alice in Wonderland, 1931 (age 19)

*Charlotte Henry, Paramount's Alice in Wonderland, 1933 (age 19)

*Mia Wasikowska, Tim Burton's Alice in Wonderland, 2010 (age 19)

*Judi Rolin, NBC Alice Through the Looking Glass, 1966 (age 20)

*Carol Marsh, Lou Bunin's Alice in Wonderland, 1949 (age 22)

*Kate Dorning, BBC Alice in Wonderland miniseries, 1986 (age 23)

*Kate Beckinsale, Channel 4 Alice Through the Looking Glass, 1998 (age 23)

*Kate Burton, Alice in Wonderland Broadway telecast, 1983 (age 26)

*Meryl Streep, Alice at the Palace, 1981 (age 32)

*Marina Neyolova (voice), Alisa v Stranes Chudes, 1981 (age 34)

*Janet Waldo (voice), Alice in Wonderland, or What's a Nice Kid Like You Doing in a Place Like This?, 1966 (age 46-47)

*Janet Waldo (voice), Burbank Films' Alice Through the Looking Glass, 1987 (age 67-68)

@ariel-seagull-wings, @themousefromfantasyland, @cbs-summer-playhouse

#alice in wonderland#alice's adventures in wonderland#through the looking glass#alice#actresses#ages#photos

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

THIS DAY IN GAY HISTORY

based on: The White Crane Institute's 'Gay Wisdom', Gay Birthdays, Gay For Today, Famous GLBT, glbt-Gay Encylopedia, Today in Gay History, Wikipedia, and more … January 27

1832 – Lewis Carroll (d.1898) is born in Baresbury, England, named Charles Lutwidge Dodgson. He was an English writer, mathematician, logician, Anglican deacon, and photographer. His most famous writings are Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, its sequel Through the Looking-Glass, which includes the poem “Jabberwocky“, and the poem The Hunting of the Snark – all examples of the genre of literary nonsense. He is noted for his facility at word play, logic and fantasy.

Carroll came from a family of high-church Anglicans, and developed a long relationship with Christ Church, Oxford, where he lived for most of his life as a scholar and teacher. Alice Liddell, daughter of the Dean of Christ Church, Henry Liddell, is widely identified as the original for Alice in Wonderland, though Carroll always denied this.

Carroll never married and his sexual identity is the subject of exploration by many historians an biographgers.

1888 - The National Geographic Society was founded In Washington, D.C. They are justly famous for many things but mainly for their magazine and for many gay men, the photographs of naked tribesmen featured in the pages of that yellow-spined National Geographic was their first look at the male form in its glory. ("What? Oh, I'm just interested in ethnography, mother.")

1936 – Troy Donahue, born in New York City (d.2001) was an American actor, known for being a teen idol.

Born Merle Johnson Jr, he was initially a journalism student at Columbia University before he decided to become an actor in Hollywood, where he was represented by Rock Hudson's agent, Henry Willson. According to Robert Hofler's 2005 biography, "The Man Who Invented Rock Hudson: The Pretty Boys and Dirty Deals of Henry Willson," Willson tried out the name Troy on Rory Calhoun and James Darren, with no success, before it finally stuck to Donahue.

The blond heartthrob made a name for himself with uncredited roles in The Monolith Monsters (1957) and Man Afraid (1957); leading to larger parts in several other films, including Monster on the Campus (1958), Live Fast, Die Young (1958), and opposite fellow teen idol Sandra Dee in A Summer Place (1959). A Summer Place was a hit and made Donahue a name, especially among teenaged audiences. He signed a contract with Warner Bros., and met actress Suzanne Pleshette on the set of Rome Adventure. They married in 1964 but divorced later that year.

Warner Bros. put him in a TV series, Surfside 6 (1960–62), one of several spin-offs of 77 Sunset Strip, announced in April 1960. On Surfside 6, Donahue starred with Van Williams, Lee Patterson, Diane McBain, and Margarita Sierra in the ABC series, set in Miami Beach, Florida. After Surfside 6 was cancelled, Donahue joined the cast of Hawaiian Eye, another spinoff of Sunset Strip, for its last season from 1962 to 1963 in the role of hotel director Philip Barton.

After the release of My Blood Runs Cold (1965), Donahue's contract with Warner Bros. ended. He later struggled to find new roles and had problems with drug addiction, alcoholism, and his closeted homosexuality.

He was married again in 1966, to actress Valerie Allen, but they divorced in 1968. In 1970 he appeared in the daytime drama The Secret Storm.

By this time, Donahue's drug addiction and alcoholism had ruined him financially. One summer, he was homeless and lived in Central Park. "There was always somebody who could be amused by Troy Donahue", he says. "I'd meet them anywhere, in a park, street, party, in bed. I lived in a bush in Central Park for one summer. I kept everything I had in a backpack."

After his fourth marriage ended in 1981, Donahue decided to seek help for his drinking and drug use. In May 1982, he joined Alcoholics Anonymous, which he credited for helping him achieve and maintain sobriety. "I look upon my sobriety as a miracle", he says. "I simply do it one day at a time. The obsession to not drink has become as big as the obsession to drink. I was very fortunate."

Donahue continued to act in films throughout the 1980s and into the late 1990s. However, he never obtained the recognition that he had in the earlier years of his career.

On August 30, 2001, Donahue suffered a heart attack and was admitted to Saint John's Health Center in Santa Monica. He died three days later on September 2 at the age of 65.

1949 – American author, essayist and cultural critic Ethan Mordden was born today. His stories, novels, essays, and non-fiction books cover a wide range of topics including the American musical theater, opera, film, and, especially in his fiction, the emergence and development of contemporary American Gay culture as manifested in New York City. He has also written for The New Yorker, including fiction, "Critic At Large "pieces on Cole Porter, Judy Garland, and the musical Show Boat, and reviews of a biography of the Barrymores and Art Spiegelman's graphic novel Maus.

His best known fictional works are the inter-related series of stories known collectively as the "Buddies" cycle. In book form, these began with 1985's I've a Feeling We're not in Kansas Anymore. The fifth in the series, 2005's How's Your Romance?, is subtitled Concluding the "Buddies" Cycle. Together, the stories chronicle the times, loves, and losses of a close-knit group of friends, men who cope with the challenges of growing up and growing older. In this circle of best friends, teasing putdowns become performance art, but none of the friends ever attacks any other friend's sensitive spots.

Mordden thus breaks away from the gay model proposed by Mart Crowley's play The Boys in the Band, in which supposed best friends assault one another relentlessly in a style that has bedeviled gay art ever since, for instance in the television series Queer As Folk. Mordden's ideal of Gay friendship presents men who genuinely like themselves and one another. They are unique in Gay lit in that they respect the limits of privacy. This explains their devotion to one another: this "family" is a safe place.

1966 – Taylor Siluwé, popular writer, blogger and activist was born in Jersey City, where he lived most of his adult life. He studied creative writing at New York University, fulfilling what he considered “a burning passion to write.”

Known for his darkly erotic and humorous story telling style, Taylor’s writing has been featured in numerous publications including Details, Venus, Literary New York, Out IN Jersey, FlavaLIFE, and the E-zine Velvet Mafia. His short stories appeared in the anthologies Law of Desire and Best Gay Erotica 2008. In addition, Taylor published two sexually charged short story collections, Dancing With the Devil and Cheesy Porn…and other Fairy Tales.

Taylor’s writing reached new heights of popularity on his blog, SGL Café.Com, which combined a canny combination of the personal and political. Taylor’s blog served has a fiery, and often hilarious, platform for the rights of same-gender-loving men, while also providing insightful and candid asides on his personal life, popular culture and his struggle with cancer.

On Sunday, June 19, 2011, Taylor Siluwé died from lung cancer in his home in New Jersey. He was 43 years old.

Radford with Duhamel

1985 – Eric Radford is a Canadian pair skater. With skating partner Meagan Duhamel, he is a two-time World bronze medalist (2013 and 2014), the 2013 Four Continents champion, the 2014-15 Grand Prix Final champion, and a three-time Canadian national champion (2012-14).

Radford began skating when he was eight years old. He competed with Sarah Burke on the ISU Junior Grand Prix series in 2003 in the Czech Republic and 2004 in Hungary, placing 6th and 5th respectively. He also competed in single skating. At the 2005 Canadian Championships, he became trapped in an elevator just before he was scheduled to skate in the men's qualifying round but eventually escaped and was able to compete.

Radford teamed up with Rachel Kirkland in 2005. They were coached by Brian Orser in Toronto and part-time by Ingo Steuer in Chemnitz, Germany. They competed at the 2007 Canadian Championships where they finished 5th. After finishing 7th at the 2009 Canadian Championships, they ended their partnership.

Radford moved back to Montreal in 2009. He teamed up with Anne-Marie Giroux and finished 8th at the 2010 Canadian Championships.

At a coach's suggestion, Radford had a tryout with Meagan Duhamel and they decided to compete together. They won a silver medal at the 2011 Canadian Championships and were assigned to the Four Continents and World Championships. At Four Continents, the pair won a silver medal. During the short program at the 2011 World Championships, Radford's nose was broken when Duhamel's elbow hit him on the descent from a twist, their first element – she opened up too early. Seeing the blood, Duhamel suggested they stop, but he decided to continue. They finished the program without a pause. Duhamel had not done a triple twist since 2005, and the new pair only began performing it before the Canadian Championships.

In the 2011–12 season, Duhamel/Radford won bronze medals at their Grand Prix events, the 2011 Skate Canada and 2011 Trophée Eric Bompard. They won their first national title and finished 5th at the 2012 World Championships. The next season, Duhamel/Radford won silver at their Grand Prix events, the 2012 Skate Canada International and 2012 Trophée Eric Bompard. They then won their second national title and their first Four Continents title. Duhamel/Radford stepped onto the World podium for the first time at the 2013 World Championships in London, Ontario where they won the bronze medal.

In 2014, Duhamel/Radford skated their short program to music composed by Radford as a tribute to his late coach Paul Wirtz. After finishing seventh at the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, they returned to the podium at the 2014 World Championships, where they scored personal bests in both the short program and the free skate on their way to a second bronze medal.

In December 2014, Radford publicly came out as gay in an interview with the LGBT publication Outsports. In doing so, he became the first competitive figure skater ever to come out at the height of his career while still a contender for championship titles, rather than waiting until he was near or past retirement; at the 2015 World Figure Skating Championships, Radford and Duhamel's gold medal win in pairs skating made him the first openly gay figure skater ever to win a medal at that competition. He is an ambassador for the Canadian Olympic Committee's #OneTeam program to combat homophobia in sports.

Radford with husband Fenero

Radford became engaged to his boyfriend, Spanish ice dancer Luis Fenero, on June 10, 2017. They wed on July 12, 2019.

Radford coaches skating in addition to competing. He studied music at York University, and plays piano and writes and composes music, and is registered as a member of the Society of Composers, Authors and Music Publishers of Canada.

1995 – At a press conference in Washington, DC, the House majority whip, Dick Armey, refers to Representative Barney Frank as 'Barney Fag.' He later apologizes, insisting it was a slip of the tongue.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

THROUGH A GLASS DARKLY (1961, Ingmar Bergman) x THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS... (1871, John Tenniel for Lewis Carroll). While Bergman's title is very close to Carroll's, it has an independent, Biblical origin—and yet the similarity of these sequences is striking, suggesting clear influence...

PERSONA (1966, Bergman) x THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS, & WHAT ALICE FOUND THERE (1871, Tenniel's original illustration for Carroll of Alice facing her reverse image & moving thru the mirror). This iconic image from PERSONA likewise seems to be clearly influenced by Carroll & Tenniel's ALICE works...

It seems fitting Carroll should inspire Bergman; both shared an interest in what lies beneath individual & social veneers, exploring it w/ elliptical, fantastical art. In the case of PERSONA, the exploration includes ALICE-esque touches of mirrors, mushrooms, madness, tea, & more...

Carroll's works have cast a long cultural shadow, & it's common to see their influence in classic films—including, seemingly, in works by Hitchcock, Rivette, Polanski, & more. Below, echoes in Kubrick's THE SHINING (whose source book by King expressly references ALICE, fwiw).

Given that TWIN PEAKS begins with rabbit references & ends with an enigmatic Alice, it's natural to impute to it an influence by Carroll's works. (But a further exploration of that topic will have to wait for another day.)

#alice in wonderland#through the looking glass and what alice found there#lewis carroll#ingmar bergman#persona#through a glass darkly#twin peaks#the shining#stanley kubrick#david lynch#mark frost#film comparison

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alice in Wonderland 1966

youtube

I realise that Alice In Wonderland, and especially the sequel, Through the Looking Glass is an acid trip of a story, that's the joy of it, but this adaption is just... surreal, like a whole 'nother level of freaky! 😆

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

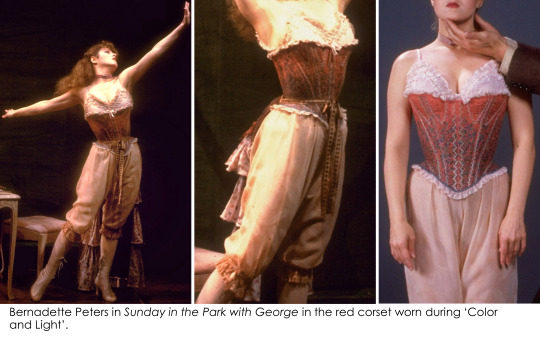

Court Gowns from Alice Through The Looking Glass (1966).. Costumes created by Bob Mackie..

536 notes

·

View notes

Text

Omg guys it's the jester from Alice through the looking glass

#alice in wonderland#alice through the looking glass#alice through the looking glass fanart#alice through the looking glass 1966

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alice Through the Looking Glass 1966

This adaptation was okay... Not the best, not the worst. This Alice was kind of mellow? I don't have much else to say. I wanted to draw her with her smile, which was a challenge. Expressions are hard! But I like when Alice has more than the usual "huh?" expression.

#alice#curiouserandcuriouser#curiouser and curiouser#through the looking glass#alice through the looking glass#alice in wonderland#lewis carroll#movie#alice timeline#1966#movie adaptation#illustration#alice liddell#drawing of the week#pen drawing#drawing#pen sketch#sketch#stippling#traditional art#my art

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

A retrospective on some of Broadway’s most important female costume designers across the last century

How much is our memory or perception of a production influenced by the manner in which we visually comprehend the characters for their physical appearance and attire? A lot.

How much attention in memory is often dedicated to celebrating the costume designers who create the visual forms we remember? Comparatively, not much.

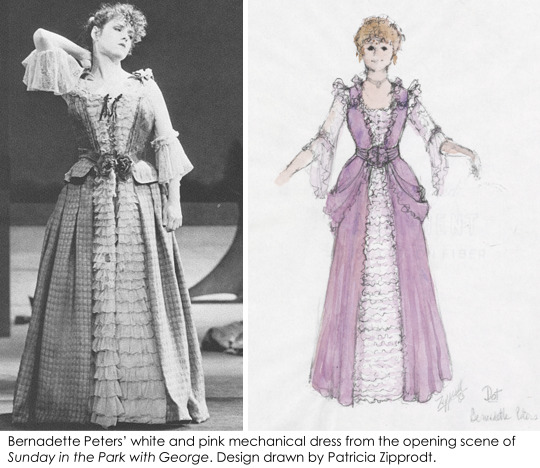

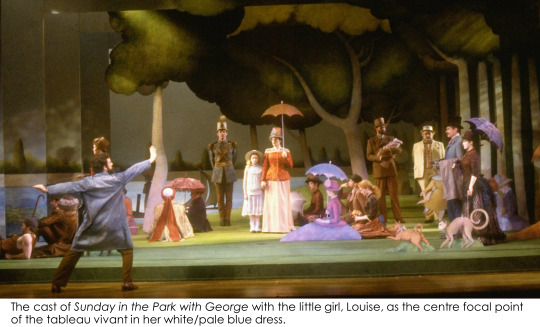

Delving through the New York Public Library archives of late, I found I was able to zoom into pictures of productions like Sunday in the Park with George at a magnitude greater than before.

In doing so, I noticed myself marvelling at finer details on the costumes that simply aren’t visible from grainy 1985 proshots, or other lower resolution images.

And marvel I did.

At first, I began to set out to address the contributions made to the show by designer Patricia Zipprodt in collaboration with Ann Hould-Ward. Quickly I fell into a (rather substantial) tangent rabbit hole – concerning over a century’s worth of interconnected designers who are responsible for hundreds of some of the most memorable Broadway shows between them.

It is impossible to look at the work of just one or two of these women without also discussing the others that came before them or were inspired by them.

Journey with me then if you will on this retrospective endeavour to explore the work and legacy that some of these designers have created, and some of the contexts in which they did so.

A set of podcasts featuring Ann Hould-Ward, including Behind the Curtain (Ep. 229) and Broadway Nation (Eps. 17 and 18), invaluably introduce some of the information discussed here and, most crucially, provide a first-hand, verbal link back to this history. The latter show sets out the case for a “succession of dynamic women that goes back to the earliest days of the Broadway musical and continues right up to today”, all of whom “were mentored by one or more of the great [designers] before them, [all] became Tony award-winning [stars] in their own right, and [all] have passed on the [craft] to the next generation.”

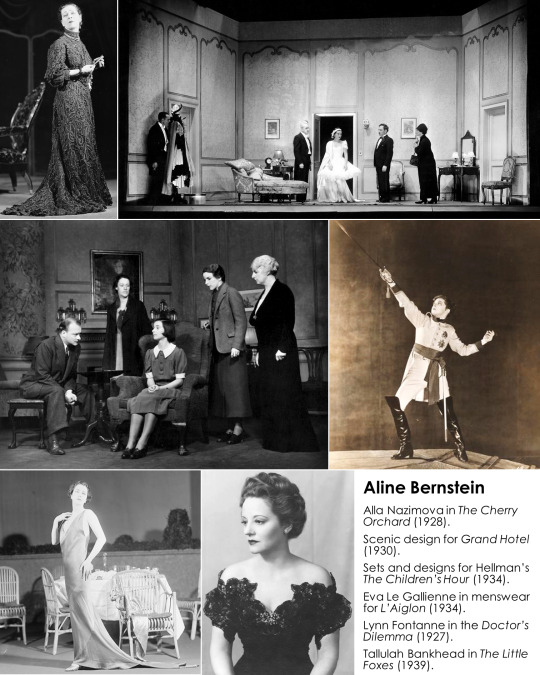

A chronological, linear descendancy links these designers across multiple centuries, starting in 1880 with Aline Bernstein, then moving to Irene Sharaff, then to Patricia Zipprodt, then to the present day with Ann Hould-Ward. Other designers branch from or interact with this linear chronology in different ways, such as Florence Klotz and Ann Roth – who, like Patricia Zipprodt, were also mentored by Aline Bernstein – or Theoni V. Aldredge, who stands apart from this connected tree, but whose career closely parallels the chronology of its central portion. There were, of course, many other designers and women also working within this era that provided even further momentous contributions to the world of costume design, but in this piece, the focus will remain primarily on these seven figures.

As the main creditor of the designs for Sunday in the Park with George, let’s start with Patricia (Pat) Zipprodt.

Born in 1925, Pat studied at the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) in New York after winning a scholarship there in 1951. Through teaching herself “all of costume history by studying materials at the New York Public Library”, she passed her entrance exam to the United Scenic Artists Union in 1954. This itself was a feat only possible through Aline Bernstein’s pioneering steps in demanding and starting female acceptance into this same union for the first time just under 30 years previously.

Pat made her individual costume design debut a year after assisting Irene Sharaff on Happy Hunting in 1956 – Ethel Merman’s last new Broadway credit. Of the more than 50 shows she subsequently designed, some of Pat’s most significant musicals include: She Loves Me (1963) Fiddler on the Roof (1964) Cabaret (1966) Zorba (1968) 1776 (1969) Pippin (1972) Mack & Mabel (1974) Chicago (1975) Alice in Wonderland (1983) Sunday in the Park with George (1984) Sweet Charity (1986) Into the Woods (1987) - preliminary work

Other notable play credits included: The Little Foxes (1967) The Glass Menagerie (1983) Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1990)

Yes. One person designed all of those shows. Many of the most beloved pieces in modern musical theatre history. Somewhat baffling.

Her work notably earned her 11 Tony nominations, 3 wins, an induction into the Theatre Hall of Fame in 1992, and the Irene Sharaff award for lifetime achievement in costume design in 1997.

By 1983, Pat was one of the most well-respected designers of her era. When the offer for Sunday in the Park with George came in, she was less than enamoured by being confined to the ill-suited basements at Playwright’s Horizons all day, designing full costumes for a story not even yet in existence. From-the-ground-up workshops are common now, but at the time, Sunday was one of the first of its kind.

Rather than flatly declining, she asked Ann Hould-Ward, previously her assistant and intern who had now been designing for 2-3 years on her own, if she was interested in collaborating. She was. The two divided the designing between them, like Pat creating Bernadette’s opening pink and white dress, and Ann her final red and purple dress.

Which indeed leads to the question of the infamous creation worn in the opening number. No attemptedly comprehensive look at the costumes in Sunday would be complete without addressing it or its masterful mechanics.

To enable Bernadette to spring miraculously and seemingly effortlessly from her outer confines, Ann and Pat enlisted the help of a man with a “Theatre Magics” company in Ohio. Dubbed ‘The Iron Dress’, the gasp-inducing motion required a wire frame embedded into the material, entities called ‘moonwalker legs and feet’, and two garage door openers coming up through the stage to lever the two halves apart. The mechanism – highly impressive in its periods of functionality – wasn’t without its flaws. Ann recalls “there were nights during previews where [Bernadette] couldn’t get out of the dress”. Or worse, a night where “the dress closed up completely. And it wouldn’t open up again!”. As Bernadette finished her number, there was nothing else within her power she could do, so she simply “grabbed it under her arm and carried it off stage.”

What visuals. Evidently, the course of costume design is not always plain sailing.

This sentiment is exhibited in the fact design work is a physical materialisation of other creators’ visions, thus foregrounding the tricky need for collaboration and compromise. This is at once a skill, very much part of the job description, and not always pleasant – in navigating any divides between one’s own ideas and those of other people.

Sunday in the Park with George was no exception in requiring such a moment of compromise and revision. With the show already on Broadway in previews, Stephen Sondheim decreed the little girl Louise’s dress “needs to be white” – not the “turquoisey blue” undertone Pat and Ann had already created it with. White, to better spotlight the painting’s centre.

Requests for alterations are easier to comprehend when they are done with equanimity and have justification. Sondheim said he would pay for the new dress himself, and in Seurat’s original painting, the little girl is very brightly the focal centre point of the piece. On this occasion, all agreed that Sondheim was “absolutely right”. A new dress was made.

Other artistic differences aren’t always as amicable.

In Pat Zipprodt’s first show, Happy Hunting with Ethel Merman in 1956, some creatives and directors were getting in vociferous, progress-stopping arguments over a dress and a scene in which Ethel was to jump over a fence. Then magically, the dress went missing. Pat was working at the time as an assistant to the senior Irene Sharaff, and Pat herself was the one to find the dress the next morning. It was in the basement. Covered in black and wholly unwearable. Sharaff had spray painted the dress black in protest against the “bickering”. Indeed, Sharaff disappeared, not to be seen again until the show arrived on Broadway.

Those that worked with her soon found that Sharaff was one to be listened to and respected – as Hal Prince did during West Side Story. After the show opened in 1957, Hal replaced her 40 pairs of meticulously created and individually dyed, battered, and re-dyed jeans with off-the-rack copies. His reasoning was this: “How foolish to be wasting money when we can make a promotional arrangement with Levi Strauss to supply blue jeans free for program credit?” A year later, he looked at their show, and wondered “What’s happened?”

What had happened was that the production had lost its spark and noticeable portions of its beauty, vibrancy, and subtle individuality. Sharaff’s unique creations quickly returned, and Hal had learned his lesson. By the time Sharaff’s mentee, Pat, had “designed the most expensive rags for the company to wear” with this same idiosyncratic dyeing process for Fiddler on the Roof in 1964, Hal recognised the value of this particularity and the disproportionately large payoff even ostensibly simple garments can bring.

Irene Sharaff is remembered as one of the greatest designers ever. Born in 1910, she was mentored by Aline Bernstein, first assisting her on 1928’s original staging of Hedda Gabler.

Throughout her 56 year career, she designed more than 52 Broadway musicals. Some particularly memorable entities include: The Boys from Syracuse (1938) Lady in the Dark (1943) Candide (1956) Happy Hunting (1956) Sweet Charity (1966) The King and I (1951, 1956) West Side Story (1957, 1961) Funny Girl (1964, 1968)

For the last three productions, she would reprise her work on Broadway in the subsequent and indelibly enduring film adaptations of the same shows.

Her work in the theatre earned her 6 Tony nominations and 1 win, though her work in Hollywood was perhaps even more well rewarded – earning 5 Academy Awards from a total of 15 nominations.

Some of Sharaff’s additional film credits included: Meet Me in St. Louis (1944) Ziegfeld Follies (1946) An American in Paris (1951) Call Me Madam (1953) A Star is Born (1954) – partial Guys and Dolls (1955) Cleopatra (1963) Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) Hello Dolly! (1969) Mommie Dearest (1981)

It’s a remarkable list. But it is too more than just a list.

Famously, Judy’s red scarlet ballgown in Meet Me in St. Louis was termed the “most sophisticated costume [she’d] yet worn on the screen.”

It has been written that Sharaff’s “last film was probably the only bad one on which she worked,” – the infamous pillar of camp culture, Mommie Dearest, in 1981 – “but its perpetrators knew that to recreate the Hollywood of Joan Crawford, it required an artist who understood the particular glamour of the Crawford era.” And at the time, there were very few – if any – who could fill that requirement better than Irene Sharaff.

The 1963 production of Cleopatra is perhaps an even more infamous endeavour. Notoriously fraught with problems, the film was at that point the most expensive ever made. It nearly bankrupted 20th Century Fox, in light of varying issues like long production delays, a revolving carousel of directors, the beginning of the infamous Burton/Taylor affair and resulting media storm, and bouts of Elizabeth’s ill-health that “nearly killed her”. In that turbulent environment, Sharaff is highlighted as one of the figures instrumental in the film’s eventual completion – “adjusting Elizabeth Taylor’s costumes when her weight fluctuated overnight” so the world finally received the visual spectacle they were all ardently anticipating.

But even beyond that, Sharaff’s work had impacts more significantly and extensively than the immediate products of the shows or films themselves. Within a few years of her “vibrant Thai silk costumes for ‘The King and I’ in 1951, …silk became Thailand’s best-known export.” Her designs changed the entire economic landscape of the country.

It’s little wonder that in that era, Sharaff was known as “one of the most sought-after and highest-paid people in her profession.” With discussions and favourable comparisions alongside none other than Old Hollywood’s most beloved designer, Edith Head, Irene deserves her place in history to be recognised as one of the foremost significant pillars of the design world.

In this respected position, Irene Sharaff was able to pass on her knowledge by mentoring others too as well as Patricia Zipprodt, like Ann Roth and Florence Klotz, who have in turn gone on to further have their own highly commendable successes in the industry.

Florence “Flossie” Klotz, born in 1920, is the only Broadway costume designer to have won six Tony awards. She did so, all of them for musicals, and all of them directed by Hal Prince, in a marker of their long and meaningful collaboration.

Indeed, Flossie’s life partner was Ruth Mitchell – Hal’s long-time assistant, and herself legendary stage manager, associate director and producer of over 43 shows. Together, Flossie and Ruth were dubbed a “power couple of Broadway”.

Flossie’s shows with Hal included: Follies (1971) A Little Night Music (1973) Pacific Overtures (1976) Grind (1985) Kiss of the Spiderwoman (1993) Show Boat (1995)

And additional shows amongst her credits extend to: Side by Side by Sondheim (1977) On the Twentieth Century (1978) The Little Foxes (1981) A Doll’s Life (1982) Jerry’s Girls (1985)

Earlier in her career, she would first find her footing as an assistant designer on some of the Golden Age’s most pivotal shows like: The King and I (1951) Pal Joey (1952) Silk Stockings (1955) Carousel (1957) The Sound of Music (1959)

The original production of Follies marked the first time Florence was seriously recognised for her work. Before this point, she was not yet anywhere close to being considered as having broken into the ranks of Broadway’s “reigning designers” of that era. Follies changed matters, providing both an indication of the talent of her work to come, and creating history in being commended for producing some of the “best costumes to be seen on Broadway” in recent memory – as Clive Barnes wrote in The New York Times. Fuller discussion is merited given that the costumes of Follies are always one of the show’s central points of debate and have been crucial to the reception of the original production as well as every single revival that has followed in the 50 years since.

In this instance, Ted Chapin would record from his book ‘Everything Was Possible: The Birth of the Musical ‘Follies’ how “the costumes were so opulent, they put the show over-budget.” Moreover, that “talking about the show years later, [Florence] said the costumes could not be made today. ‘Not only would they cost upwards of $2 million, but we used fabrics from England that aren’t even made anymore.’” Broadway then does indeed no longer look like Broadway now.

This “surreal tableau” Flossie created, including “three-foot-high ostrich feather headdresses, Marie Antoinette wigs adorned with musical instruments and birdcages, and gowns embellished with translucent butterfly wings”, remains arguably one of the most impressive and jaw-dropping spectacles to have ever graced a Broadway stage even to this day.

As for Ann Roth, born in 1931, she is still to this day making her own history – recently becoming the joint eldest nominee at 89 for an Oscar (her 5th), for her work on 2020′s Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom. Now as of April 26th, Ann has just made history even further by becoming the oldest woman to win a competitive Academy Award ever. She has an impressive array of Hollywood credits to her name in addition to a roster of Broadway design projects, which have earned her 12 Tony nominations.

Some of her work in the theatre includes: The Women (1973) The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas (1978) They're Playing Our Song (1979) Singin' in the Rain (1985) Present Laughter (1996) Hedda Gabler (2009) A Raisin in the Sun (2014) Shuffle Along (2016) The Prom (2018)

Making her way over to Hollywood in the ‘70s, she has left an indelible and lasting visual impact on the arts through films like: Klute (1971) The Goodbye Girl (1977) Hair (1979) 9 to 5 (1980) Silkwood (1983) Postcards from the Edge (1990) The Birdcage (1996) The Hours (2002) Mamma Mia! (2008) Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (2020)

It’s clear from this branching 'tree' to see how far the impact of just one woman passing on her time and knowledge to others who are starting out can spread.

This art of acting as a conduit for valuable insights was something Irene Sharaff had learned from her own mentor and predecessor, Aline Bernstein. Aline was viewed as “the first woman in the [US] to gain prominence in the male-dominated field of set and costume design,” and was too a strong proponent of passing on the unique knowledge she had acquired as a pioneer and forerunner in the field.

Born in 1880, Bernstein is recognised as “one of the first theatrical designers in New York to make sets and costumes entirely from scratch and craft moving sets” while Broadway was still very much in its infancy of taking shape as the world we know today. This she did for more than one hundred shows over decades of her work in the theatre. These shows included the spectacular Grand Street Follies (1924-27), and original premier productions of plays like some of the following: Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler (1928) J.M Barrie’s Peter Pan (1928) Grand Hotel (1930) Phillip Barry’s Animal Kingdom (1932) Chekov’s The Seagull (1937) Both Lillian Hellman’s The Children’s Hour (1934) and The Little Foxes (1939)

Beyond direct design work, Bernstein founded what was to become the Neighbourhood Playhouse (the notable New York acting school) and was influential in the “Little Theatre movement that sprung up across America in 1910”. These were the “forerunners of the non-profit theatres we see today” and she continued to work in this realm even after moving into commercial theatre.

Bernstein also established the Museum of Costume Art, which later became the Costume Institute of the Met Museum of Art, where she served as president from 1944 to her death in 1955. This is what the Met Gala raises money for every year. So for long as you have the world’s biggest celebrities parading up and down red carpets in high fashion pieces, you have Aline Bernstein to remember – as none of that would be happening without her.

During the last fifteen years of her life, Bernstein taught and served as a consultant in theatre programs at academic institutions including Yale, Harvard, and Vassar – keen to connect the community and facilitate an exchange of wisdom and information to new descendants and the next generation.

Many designers came somewhere out of this linear descendancy. One notable exception, with no American mentor, was Theoni V. Aldredge. Born in 1922 and trained in Greece, Theoni emigrated to the US, met her husband, Tom Aldredge – himself of Into the Woods and theatre notoriety – and went on to design more than 100 Broadway shows. For her work, she earned 3 Tony wins from 11 nominations from projects such as: Anyone Can Whistle (1964) A Chorus Line (1975) Annie (1977) Barnum (1980) 42nd Street (1980) Woman of the Year (1981) Dreamgirls (1981) La Cage aux Folles (1983) The Rink (1984)

One of the main features that typify Theoni’s design style and could be attributed to a certain unique and distinctive “European flair” is her strong use of vibrant colour. This is a sentiment instantly apparent in looking longitudinally at some of her work.

In Ann Hould-Ward’s words, Theoni speaks to the “great generosity” of this profession. Theoni went out of her way to call Ann apropos of nothing early in the morning at some unknown hotel just after Ann won her first Tony for Beauty and the Beast in 1994, purring “Dahhling, I told you so!” These were women that had their disagreements, yes, but ultimately shared their knowledge and congratulated each other for their successes.

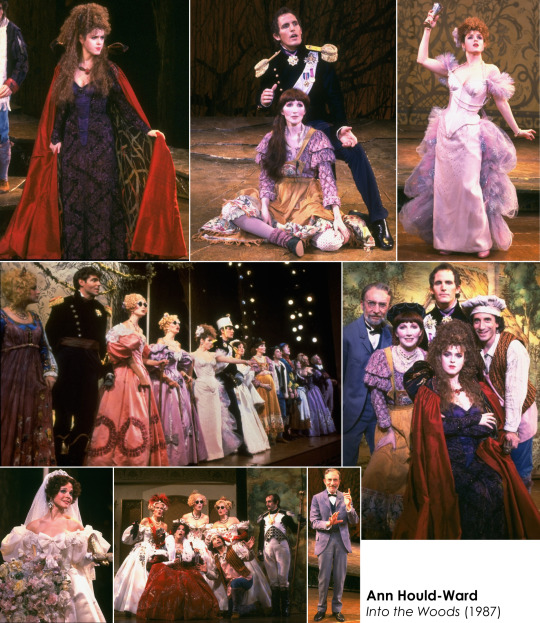

Similar anecdotal goodwill can be found in Pat Zipprodt’s call to Ann on the night of the 1987 Tony’s – where Ann was nominated for Into the Woods – with Pat singing “Have wonderful night! You’re not gonna win! …[laugh] but I love you anyway!”

This well-wishing phone call is all the more poignant considering Pat was originally involved with doing the costumes for Into the Woods, in reprise of their previous collaboration on Sunday in the Park with George.

If, for example, Theoni instinctively is remembered for bright colour, one of the features that Pat is first remembered for is her dedicated approach to research for her designs. Indeed, the New York Public Library archives document how the remaining physical evidence of this research she conducted is “particularly thorough” in the section on Into the Woods. Before the show finally hit Broadway in 1987 with Ann Hould-Ward’s designs, records show Pat had done extensive investigation herself into materials, ideas and prospective creations all through 1986.

Both Ann and Pat worked on the show out of town in try-outs at the Old Globe theatre in San Diego. But when it came to negotiating Broadway contracts, the situation became “tricky” and later “untenable” with Pat and the producers. Ann was “allowed to step in and design” the show alone instead.

The lack of harboured resentment on Patricia’s behalf speaks to her character and the pair’s relationship, such that Ann still considered her “my dear and beloved friend” for over 25 years, and was “at [Pat’s] bed when she died”.

Though they parted ways ultimately for Into the Woods, you can very much feel a continuation between their work on Sunday in the Park with George a few years previously, especially considering how tactile the designs appear in both shows. This tactility is something the shows’ book writer and director, James Lapine, was specific about. Lapine would remark in his initial ideas and inspirations that he wanted a graphic quality to the costumes on this occasion, like “so many sketches of the fairy-tales do”.

Ann fed that sentiment through her final creations, with a wide variety of materials and textures being used across the whole show – like “ribbons with ribbons seamed through them”, “all sorts of applique”, “frothy organzas and rembriodered organzas”. A specific example documents how Joanna Gleason’s shawl as the Baker’s Wife was pieced together, cut apart, and put back together again before resembling its final form.

This highly involved principle demonstrates another manner of inventive design that uses a different method but maintains the aim of particularity as discussed previously with Patricia and Irene’s complex dyeing and re-dyeing process. Pushing the confines of what is possible with the materials at hand to create a variety of colours, shades, and textures ultimately produces visual entities that are complex to look at. Confusing the eye like this “holds attention longer”, Ann maintains, which makes viewers look more intricately at individual segments of the production, and enables the costume design to guide specific focus by not immediately ceding attention elsewhere.

Understanding the methods behind the resultant impacts of a show can be as, if not more, important and interesting than the final product of the show itself sometimes. A phone call Ann had last August with James Lapine reminds us this is a notion we may be treated more to in the imminent future, when he called to enquire as to the location of some design sketches for the book he is working on (Putting It Together: How Stephen Sondheim and I Created 'Sunday in the Park with George') to document more thoroughly the genesis of the pair’s landmark and beloved musical.

In continuation of the notion that origin stories contain their own intrinsic value beyond any final product, Ann first became Pat’s intern through a heart-warming and tenacious tale. Ann sent letters to three notable designers when finishing graduate school. Only Patricia Zipprodt replied, with a message to say she “didn’t have anything now but let me think about it and maybe in the future.” It got to the future, and Ann took the encouragement of her previous response to try and contact Pat again. Upon being told she was out of town with a show, Ann proceeded to chase Pat through various phone books and telephone wires across different states and theatres until she finally found her. She was bolstered by the specifics of their call and ran off the phone to write an imploring note – hinging on the premise of a shared connection to Montana. She took an arrow, stabbed it through a cowboy hat, put it in a box with the note that was written on raw hide, and mailed it to New York with bated breath and all of her hopes and wishes.

Pat was knife-edgingly close to missing the box, through a matter of circumstance and timing. Importantly, she didn’t. Ann got a response, and it boded well: “Alright alright alright! You can come to New York!”

Subsequently, Ann’s long career in the design world of the theatre has included notable credits such as: Sunday in the Park with George (1984) Into the Woods (1987, 1997) Falsettos (1992) Beauty and the Beast (1994, 1997) Little Me (1998) Company (2006) Road Show (2008) The People in the Picture (2011) Merrily We Roll Along (1985, 1990, 2012, segment in Six by Sondheim 2013) Passion (2013) The Visit (2015) The Color Purple (2015) The Prince of Egypt (2021)

From early days in the city sleeping on a piece of foam on a friend’s floor, to working collaboratively alongside Pat, to using what she’d learnt from her mentor in designing whole shows herself, and going on to win prestigious awards for her work – the cycle of the theatre and the importance of handing down wisdom from those who possess it is never more evident.

As Ann summarises it meaningfully, “the theatre is a continuing, changing, evolving, emotional ball”. It’s raw, it’s alive, it needs people, it needs stories, it needs documentation of history to remember all that came before.

In periods where there can physically be no new theatre, it’s made ever the more clear for the need not to forget what value there is in the tales to be told from the past.

Through this retrospective, we’ve seen the tour de force influence of a relatively small handful of women shaping a relatively large portion of the visual scape of some of Broadway’s brightest moments.

But it’s significant to consider how disproportionate this female impact was, in contrast with how massively male dominated the rest of the creative theatre industry has been across the last century.

Assessing variations in attitudes and approaches to relationships and families in these women in the context of their professional careers over this time period presents interesting observations. And indeed, manners in which things have changed over the past hundred years.

As Ann Hould-Ward speaks of her experiences, one of her reflections is how much this was a “very male dominated world”. And one that didn’t accommodate for women with families who also wanted careers. As an intern, she didn’t even feel she could tell Patricia Zipprodt about the existence of her own young child until after 6 months of working with her. With all of these male figures around them, it would be often questioned “How are you going to do the work? How are you going to manage [with a family]?”, and that it was “harder to convince people that you were going to be able to do out-of-towns, to be able to go places.” Simply put, the industry “didn't have many designers who were married with children.”

Patricia herself in the previous generation demonstrates this restricting ethos. “In 1993, Zipprodt married a man whose proposal she had refused some 43 years earlier.” She had just newly graduated college and “she declined [his proposal] and instead moved to New York.” Faced with the family or career conundrum, she chose the latter. By the 1950s, it then wasn’t seen as uncommon to have both, it was seen as impossible.

Her husband died just five years after the pair were married in 1998, as did Patricia herself the following year. One has to wonder if alternative decisions would’ve been made and lives lived differently if she’d experienced a different context for working women in her younger life.

But occupying any space in the theatre at all was only possible because of the efforts of and strides made by women in previous generations.

When Aline Bernstein first started designing for Broadway theatre in 1916, women couldn’t even vote. She became the first female member of the United Scenic Artists of America union in 1926, but only because she was sworn in under the false and male moniker of brother Bernstein. In fact, biographies often centralise on her involvement in a “passionate” extramarital love affair with novelist Thomas Wolfe – disproportionately so for all of her remarkable contributions to the theatrical, charitable and academic worlds, and instead having her life defined through her interactions with men.

As such, it is apparent how any significant interactions with men often had direct implications over a woman’s career, especially in this earlier half of the century. Only in their absence was there comparative capacity to flourish professionally.

Irene Sharaff had no notable relationships with men. She did however have a significant partnership with Chinese-American painter and writer Mai-mai Sze from “the mid-1930s until her death”. Though this was not (nor could not be) publicly recognised or documented at the time, later by close acquaintances the pair would be described as a “devoted couple”, “inseparable”, and as holding “love and admiration for one another [that] was apparent to everyone who knew them.” This manner of relationship for Irene in the context of her career can be theorised as having allowed her the capacity to “reach a level of professional success that would have been unthinkable for most straight women of [her] generation”.

Moving forwards in time, Irene and Mai-mai presently rest where their ashes are buried under “two halves of the same rock” at the entrance to the Music and Meditation Pavilion at Lucy Cavendish College in Cambridge, which was “built following a donation by Sharaff and Sze”. I postulate that this site would make for an interesting slice of history and a perhaps more thought-provoking deviation for tourists away from being shepherded up and down past King’s College on King’s Parade as more usually upon a visit to Cambridge.

In this more modern society at the other end of this linear tree of remarkable designers, options for women to be more open and in control of their personal and professional lives have increased somewhat.

Ann Hould-Ward later in her career would no longer “hide that [she] was a mother”, in fear of not being taken seriously. Rather, she “made a concerted effort to talk about [her] child”, saying “because at that point I had a modicum of success. And I thought it was supportive for other women that I could do this.”

If one aspect passed down between these women in history are details of the craft and knowledge accrued along the way, this statement by Ann represents an alternative facet and direction that teaching of the future can take. Namely, that by showing through example, newer generations will be able to comprehend the feasibility of occupying different options and spaces as professional women. Existing not just as designers, or wives, or mothers, or all, or one – but as people, who possess an immense talent and skill. And that it is now not just possible, but common, to be multifaceted and live the way you want to live while working.

This is not to say all of the restrictions and barriers faced by women in previous generations have been removed, but rather that as we build a larger wealth of history of women acting with autonomy and control to refer back to, things can only get easier to build upon for the future.

Who knows what Broadway and theatre in general will look like when it returns – both on the surface with respect to this facet of costume design, and also more deeply as to the inner machinations of how shows are put together and presented. The largely male environment and the need to tick corporate and commercial boxes will not have vanished. One can only hope that this long period of stasis will have foregrounded the need and, most importantly, provided the time to revaluate the ethos in which shows are often staged, and the ways in which minority groups – like women – are able to work and be successful within the theatre in all of the many shows to come.

Notable sources:

Photographs – predominantly from the New York Public Library digital archives. IBDB – the Internet Broadway Database. Broadway Nation Podcast (Eps. #17 and #18), David Armstrong, featuring Ann Hould-Ward, 2020. Behind the Curtain: Broadway’s Living Legends Podcast (Ep. #229), Robert W Schneider and Kevin David Thomas, featuring Ann Hould-Ward, 2020. Sense of Occasion, Harold Prince, 2017. Everything Was Possible: The Birth of the Musical ‘Follies’, Ted Chapin, 2003. Finishing the Hat: Collected Lyrics (1954–1981) with Attendant Comments, Principles, Heresies, Grudges, Whines and Anecdotes, Stephen Sondheim, 2010. The Complete Book of 1970s Broadway Musicals, Dan Deitz, 2015. The Complete Book of 1980s Broadway Musicals, Dan Dietz, 2016. Inventory of the Patricia Zipprodt Papers and Designs at the New York Public Library, 2004 – https://www.nypl.org/sites/default/files/archivalcollections/pdf/thezippr.pdf Extravagant Crowd’s Carl Van Vecten’s Portraits of Women, Aline Bernstein – http://brbl-archive.library.yale.edu/exhibitions/cvvpw/gallery/bernstein.html Jewish Heroes & Heroines of America: 150 True Stories of American Jewish Heroism – Aline Bernstein, Seymour Brody, 1996 – https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/aline-bernstein Ann Hould-Ward Talks Original “Into the Woods” Costume Designs, 2016 – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4EPe77c6xzo&ab_channel=Playbill American Theatre Wing’s Working in the Theatre series, The Design Panel, 1993 – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9sp-aMQHf-U&t=2167s&ab_channel=AmericanTheatreWing Journal of the History of Ideas Blog, Mai-mai Sze and Irene Sharaff in Public and in Private, Erin McGuirl, 2016 – https://jhiblog.org/2016/05/16/mai-mai-sze-and-irene-sharaff-in-public-and-in-private/ Irene Sharaff’s obituary, The New York Times, Marvine Howe, 1993 – https://www.nytimes.com/1993/08/17/obituaries/irene-sharaff-designer-83-dies-costumes-won-tony-and-oscars.html Obituary: Irene Sharaff, The Independent, David Shipman, 2011 – https://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary-irene-sharaff-1463219.html Broadway Design Exchange – Florence Klotz – https://www.broadwaydesignexchange.com/collections/florence-klotz Obituary: Florence Klotz, The New York Times, 2006 – https://www.nytimes.com/2006/11/03/obituaries/03klotz.html

#bernadette peters#sunday in the park with george#costume design#costume designers#stephen sondheim#sondheim#broadway#theatre#tony awards#oscars#academy award nominations#ethel merman#judy garland#into the woods#theater#musical theater#fashion#dresses#meryl streep#elizabeth taylor#old hollywood#film#costumes#movies#musicals#writing#long reads#hollywood#actresses

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

Todos os filmes em que as cenas de sexo foram para valer

A Bula reuniu em uma lista todos os filmes da história do cinema nos quais os atores se envolvem em atos sexuais reais, não simulados. A diferença entre esses longas e a pornografia é que, embora possam ser considerados eróticos, a trama deles não é meramente pornográfica. Ao todo, a lista conta com 264 títulos.

A Bula reuniu em uma lista todos os filmes da história do cinema nos quais os atores se envolvem em atos sexuais reais, não simulados. Nos Estados Unidos, esse tipo de cena era proibido no cinema convencional, mas a partir dos Anos 1960 os cineastas começaram a ultrapassar os limites. A diferença entre esses longas e a pornografia é que, embora possam ser considerados eróticos, a trama deles não é meramente pornográfica. A maioria deles foi lançada nos anos 1970 e 80, com predominância de dois diretores: o espanhol Jesús Franco e o italiano Joe D’Amato. Por repetidas vezes, também aparecem os nomes de cineastas consagrados atualmente, como Lars von Trier, Gaspar Noé e Yorgos Lanthimos.

1 — Gift (1966), Knud Leif Thomsen

2 — They Call Us Misfits (1968), Stefan Jarl

3 — F*uck (1969), Andy Warhol

4 — 99 Mulheres (1969), Stefen Thrower

5 — Double Face (1969), Riccardo Freda

6 — Quiet Days in Clichy (1970), Jens Jørgen Thorsen

7 — Groupie Girl (1970), Drek Ford

8 — The Deviates (1970), Eduardo Cemano

9 — Bacchanale (1970), John Amero

10 — Kama Sutra ’71 (1970), Raj Devi

11 — Cry Uncle! (1971), John G. Avildsen

12 — Slaughter Hotel (1971), Fernando Di Leo

13 — Uma Lagartixa num Corpo de Mulher (1971), Lucio Fulci

14 — Luminous Procuress (1971), Steven F. Arnold

15 — Secret Rites (1971), Drek Ford

16 —A Clockwork Blue (1972), Eric Jeffrey Haims

17 — Pink Flamingos (1972), John Waters

18 — Who Killed the Prosecutor and Why? (1972), Giuseppe Vari

19 — La Verità Secondo Satana (1972), Ronato Polselli

20 — So Sweet, So Dead (1972), Rose et Val

21 — The Red Headed Corpse (1972), Renzo Russo

22 — Commuter Husbands (1972), Derek Ford

23 — Delirium (1972), Renato Polselli

24 — Christina, the Devil Nun (1972), Sergio Bergonzelli

25 — Danish Pastries (1973), Finn Karlsson

26 — Ingrid the Streetwalker (1973), Brunello Rondi

27 — Thriller – Um Filme Cruel (1973), Bo Arne Vibenius

28 — Revelations of a Psychiatrist on the World of Sexual Perversion (1973), Renato Polselli

29 — A Scream in the Streets (1973), Carl Monson

30 — The Devil In Miss Jones (1973), Gerard Damiano

31 — Fleshpot on 42nd Street (1973), Andy Milligan

32 — The Other Side of the Mirror (1973), Jess Franco

33 — Diary of a Nynphomaniac (1973), Jesús Franco

34 — A Virgem e os Mortos (1973), Jesús Franco

35 — O Reduto dos Monstros (1973), Vidal Raski

36 — The Devil’s Plaything (1973), Joseph W. Sarno

37 — Anita (1973), Torgny Wickman

38 — The Sex Thief (1973), Martin Campbell

39 — The Porn Brokers (1973), John Lindsay

40 — Emmanuelle (1974), Just Jaeckin

41 — The Eerie Midnight Horror Show (1974), Mario Gariazzo

42 — Zelda (1974), Alberto Cavallone

43 — I Tyrens Tegn (1974), Werner Hedman

44 — Score (1974), Radley Metzger

45 — Riot on a Women’s Prison (1974), Brunello Rondi

46 — The Girls of Kamare (1974), René Viénet

47 — La Bonzesse (1974), François Jouffa

48 — Sweet Movie (1974), Dušan Makavejev

49 — Fiossie (1974), Marie Forsa

50 — Contos Imorais (1974), Walerian Borowczyk

51 — Lorna: O Exorcista (1974), Jesús Franco

52 — Countess Perverse (1974), Jesús Franco

53 — Carnal Revenge (1974), Alfredo Rizzo

54 — Keep It Up, Jack! (1974), Derek Ford

55 — The Hot Girls (1974), John Lindsay

56 — Voodoo Sexy (1974), Osvaldo Civirani

57 — Nude for Satan (1974), Luigi Batzella

58 — In the Sign of the Gemini (1974), Werner Hadman

59 — Come To My Bedside (1975), John Hillbard

60 — The Image (1975), Radley Metzger

61 — Número Dois (1975), Jean-Luc Godard

62 — The Teenage Prostitution Racket (1975), Carlo Lizzani

63 — Emanuelle Nera (1975), Bitto Albertini

64 — Emanuelle’s Revenge (1975), Joe D’Amato

65 — Felicia (1975), Max Pécas

66 — But Who Raped Linda? (1975), Jesús Franco

67 — A Maldição da Vampira (1975), Jesús Franco

68 — Les Chatouilleuses (1975), Jesús Franco

69 — L’Éventreur de Notre-Dame (1975), Jesús Franco

70 — Justine e Juliette (1975), Mac Ahlberg

71 — The Bloodsucker Leads the Dance (1975), Alfredo Rizzo

72 — Lábios de Sangue (1975), Jean Rollin

73 — Rêves Pornos (1975), Max Pécas

74 — Wham! Bam! Thank You, Spaceman! (1975), William A. Levey

75 — Breaking Point (1975), Bo Arne Vibenius

76 — Rolls-Royce Baby (1975), Erwin C. Dietrich

77 — Girls Come First (1975), Joseph McGrath

78 — The Sexplorer (1975), Derek Ford

79 — Le Sexe qui Parle (1975), Claude Mulot

80 — Barbie Wire Dolls (1975), Jesús Franco

81 — Emanuelle em Bangkok (1975), Joe D’Amato

82 — Lust (1976), Max Pécas

83 — The Opening of Misty Beethoven (1976), Radley Metzger

84 — Alice in Wonderland: An X-Rated Musical Fantasy (1976), Bud Townsend

85 — Bedside Sailors (1976), John Hillbard

86 — In The Sign of the Lion (1976), Werner Hedman

87 — O Império dos Sentidos (1976), Nagisa Oshima

88 —Through the Looking Glasses (1976), Jonas Middleton

89 — A Real Young Girl (1976), Catherine Breillat

90 — Die Marquise von Sade (1976), Jesús Franco

91 — Girls in the Night Traffic (1976), Jesús Franco

92 — The French Governess (1976), Demofilo Fidani

93 — Inhibition (1976), Paolo Poetti

94 — Around the World in 80 Beds (1976), Jesús Franco

95 — Sex Express (1976), Derek Ford

96 — Keep It Up Downstairs (1976), Robert Young

97 — Secrets of a Superstud (1976), Morton L Lewis

98 — The Office Party (1976), David Grant

99 — The Angel and The Woman (1976), Gilles Carle

100 — Agent 69 in the Sign of Scorpio (1977), Werner Hedman

101 — Shining Sex (1977), Werner Hedman

102 — Fate la nanna coscine di pollo (1977), Amasi Damiani

103 — Blue Rita (1977), Jesús Franco

104 — Emanuelle na América (1977), Joe D’Amato

105 — Emanuelle Around the World (1977), Joe D’Amato

106 — Sister Emanuelle (1977), Giuseppe Vari

107 — Nazi Love Camp 27 (1977), Mario Caiano

108 — Under The Bed (1977), David Grant

109 — The Mark (1977), Ilias Mylonakos

110 — The Cerimony (1977), Omiros Efstratiadis

111 — Monsieur Sade (1977), Jacques Robin

112 — Caligula’s Hot Nights (1977), Roberto Bianchi

113 — Agent 69 Jensen in the Sign of Sagittarius (1978), Werner Hedman

114 — Behind Convent Walls (1978), Walerian Borowczyk

115 — Blue Movie (1978), Alberto Cavallone

116 — Sister of Ursula (1978), Enzo Milloni

117 — The Coming of Sin (1978), José Ramón Larraz

118 — Pleasure Shop on the Avenue (1978), Joe D’Amato

119 — You’re Driving Me Crazy (1978), David Grant

120 — Immoral Women (1979), Walerian Borowczyk

121 — Caligula (1979), Bob Guccione

122 — Images In a Convent (1979), Joe D’Amato

123 — Play Model (1979), Mario Gariazzo

124 — Giallo a Venezia (1979), Mario Landi

125 — Malabimba (1979), Andrea Bianchi

126 — A Prisão (1980), Oswaldo de Oliveira

127 — Beast in Space (1980), Alfonso Brescia

128 — Blow Job (1980), Alberto Cavallone

129 — La Gemella Erotica (1980), Alberto Cavallone

130 — Erotic Nights of the Living Dead (1980), Joe D’Amato

131 — Orgasmo Nero (1980), Joe D’Amato

132 — Flying Sex (1980), Joe D’Amato

133 — Libidomania (1980), Bruno Mattei

134 — When love is obscenity (1980), Roberto Polselli

135 — Hard Sensation (1980), Joe D’Amato

136 — Hotel Paradise (1980), Edoardo Mulargia

137 — Sex and Black Magic (1980), Joe D’Amato

138 — Porno Esotic Love (1980), Joe D’Amato

139 — The Porno Killers (1980), Roberto Mauri

140 — Sem Controle (1980), Paul Verhoeven

141 — Táxi para o Banheiro (1980), Frank Ripploh

142 — Os Frutos da Paixão (1981), Shuji Terayama

143 — Emmanuelle in Soho (1981), David Hughes

144 — Porno Holocaust (1981), Joe D’Amato

145 — Calígula: A História que Não Foi Contada (1982), Joe D’Amato

146 — Scandale (1982), George Mihalka

147 — Apocalipsis Sexual (1982), Carlos Aured

148 — Aphrodite (1982), Robert Fuest

149 — Il Nano Erotico (1982), Alberto Cavallone

150 — My Nights With Messalina (1982), Jaime J. Puig

151 — The Virgin for Caligula (1982), Jaime J. Puig

152 — Luz del Fuego (1982), David Neves

153 — Perdida em Sodoma (1982), Nilton Nascimento

154 — Killing of the Flesh (1983), Cesari Canevari

155 — Satan’s Baby Doll (1983), Mario Bianchi

156 — Taking Tiger Mountain (1983), Tom Huckabee

157 — Emmanuelle 4 (1984), Francis Leroi

158 — Lilian, The Perverted Virgin (1984), Jesús Franco

159 — Alcova (1985), Joe D’Amato

160 — James Joyce’s Women (1985), Michael Pearce

161 — Diabo no Corpo (1986), Marco Bellocchio

162 — Emmanuelle 5 (1987), Walerian Borowczyk

163 — Emmanuelle 6 (1988), Bruno Zincone

164 — Hotel St. Pauli (1988), Svend Wan

165 — Kindergarten (1989), Jorge Polaco

166 — Kinski Paganini (1989), Klaus Kinski

167 — Tokyo Decadence (1992), Ryu Murakami

168 — The Soft Kill (1994), Eli Cohen

169 — A Vida de Jesus (1997), Bruno Dumont

170 — Os Idiotas (1998), Lars von Trier

171 — O Tédio (1998), Cédric Kahn

172 — Fiona (1998), Amos Kollek

173 — Jesus is a Palestinian (1999), Lodewijk Crijns

174 — Romance (1999), Catherine Breillat

175 — Pola X (1999), Leos Carax

176 — The Man-Eater (1999), Aurelio Grimaldi

177 — Olhe por Mim (1999), Davide Ferrario

178 — Vampire Strangler (1999), William Hellfire

179 — Baise-moi (2000), Virginie Despentes

180 — Scrapbook (2000), Eric Stanze

181 — Intimacy (2001), Patrice Chéreau

182 — O Pornógrafo (2001), Bertrand Bonello

183 — Lucia e o Sexo (2001), Julio Medem

184 — Dias de Cão (2001), Ulrich Seidl

185 — O Centro do Mundo (2001), Wayne Wang

186 — La Novia de Lázaro (2002), Fernando Merinero

187 — Le loup de la côte Ouest (2002), Hugo Santiago

188 — Eternamente Sua (2002), Apichatpong Weerasethakul

189 — Coisas Secretas (2002), Jean-Claude Brisseau

190 — Ken Park (2002), Larry Clark

191 — Brown Bunny (2003), Vincent Gallo

192 — Faça Isto (2003), Tinto Brass

193 — Rossa Venezia (2003), Andreas Bethmann

194 — The Principles of Lust (2003), Penny Woolcock

195 — Anatomia do Inferno (2004), Catherine Breillat

196 — 9 Canções (2004), Michael Winterbottom

197 — Story of The Eye (2004), Georges Bataille

198 — Kärlekens språk (2004), Anders Lennberg

199 — Garotinho Bobo (2004), Lionel Baier

200 — All About Anna (2005), Jessica Nilsson

201 — 8mm 2 (2005), J. S. Cardone

202 — Beijando na Boca (2005), Joe Swanberg

203 — O Sabor da Melancia (2005), Tsai Ming-Liang

204 — Princesas (2005), Fernando Léon de Aranoa

205 — Deite Comigo (2005), Clement Virgo

206 — Destricted (2006), Gaspar Noé e outros

207 — Shortbus (2006), John Cameron Mitchell

208 — Taxidermia (2006), Gyorgy Pálfi

209 — Os Anjos Exterminadores (2006), Jean-Claude Brisseau

210 — Amour Fou (2007), Felicitas Korn

211 — Ex Drummer (2007), Koen Mortier

212 — Its Fine. Everything is Fine! (2007), David Brothers

213 — The Story of Richard O (2007), Damien Odoul

214 — Import Export (2007), Ulrich Seidl

215 — Serviço (2008), Brillante Mendoza

216 — Tropical Manila (2008), Sang-woo Lee

217 — Otto, ou Viva Gente Morta (2008), Bruce LaBruce

218 — À l’aventure (2008), Jean-Claude Brisseau

219 — Amateur Porn Star Killer 2 (2008), Shane Ryan

220 — Gutterballs (2008), Ryan Nicholson

221 — House of Flesh Mannequins (2009), Domiziano Cristopharo

222 — Anticristo (2009), Lars von Trier

223 — Viagem Alucinante (2009), Gaspar Noé

224 — The Band (2009), Anna Brownfield

225 — Canino (2009), Yorgos Lanthimos

226 — Angels With Dirty Wings (2009), Roland Reber

227 — Now & Later (2009), Philippe Diaz

228 — Bedways (2010), Rolf Peter Kahl

229 — Rio Sex Comedy (2010), Jonathan Nossiter

230 — The Bunny Game (2010), Adam Rehmeier

231 — Ano Bissexto (2010), Michael Rowe

232 — Gandu (2010), Qaushiq Mukherjee

233 — LelleBelle (2011), Mischa Kamp

234 — Desire (2011), Laurent Bouhnik

235 — O Amor é um Saco! (2011), Scud

236 — Caged (2011), Stephan Brenninkmeijer

237 — Léa (2011), Bruno Rolland

238 — The Wrong Ferrari (2011), Adam Green

239 — Clip (2011), Maja Milos

240 — Uma Estranha Amizade (2012), Sean S. Baker

241 — Paradise: Faith (2012), Ulrich Seidl

242 —And They Call It Summer (2012), Paolo Franchi

243 — I Want Your Love (2012), Travis Mathews

244 — Crônicas Sexuais de Uma Família Francesa (2012), Pascal Arnold

245 — Azul é a Cor Mais Quente (2013), Abdellatif Kechiche

246 — Ninfomaníaca (2013), Lars von Trier

247 — Pornopung (2013), Johan Kaos

248 — O Desconhecido do Lago (2013), Alain Guiraudie

249 — Zonas Úmidas (2013), David Wnendt

250 — Pasolini (2014), Abel Ferrara

251 — Diet of Sex (2014), Borja Brun

252 — Angry Painter (2015), Kyu-hwan Jeon

253 — Love (2015), Gaspar Noé

254 — Muito Amadas (2015), Nabil Ayouch

255 —Theo e Hugo (2016), Olivier Ducastel