#albanian vocabulary

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Vocabulary in some languages of Indo-European (Indian subcontinent, Iranian, Armenian, and European).

#languages#culture#vocabulary#indo european#hindi language#urdu language#sindhi#pashto#punjabi#kashmiri#nepali#sinhalese#bengali#iranian#persian#afghanistan#tajik#armenian#kurdish#slavic#germanic#romance#albanian#greek tumblr#scriptwriting#language arts#alphabet#russian#yiddish#wordpress

1 note

·

View note

Text

Arnavut Dilinin Diyalektleri: Toskça ve Gegçe

Bugün aslında biraz bu konu üzerine araştırma yaptım ve yapmaya da devam ediyorum. Kendime aslında Arnavutlarla ilgili her şeyi öğrenmek için bir araştırma listesi hazırladım. Yeni şeyler öğrendikçe buraya yazıyor olacağım. Konumuza gelirsek, Arnavut dilinin bilinen iki diyalekti olduğu söyleniyor. Birincisi ve bildiğim kadarıyla standart Arnavutçayı oluşturan Toskça. İkincisi ise Gegçe diyebiliriz. Kuzey ve Orta Arnavutlukta Gegçe konuşuluyor. Güney Arnavutluk'ta ise Toskça diyalekti kullanılıyor. İki diyalekt arasındaki sınırı Shkumbin nehrinin oluşturduğu da söyleniyor. Her diyalektin kendi içinde de alt diyalektleri var. Örneğin,

Gegçe’nin alt diyalektleri:

Güney Gegçesi (Tiran, Elbasan, Durrës).

Kuzeybatı Gegçesi (Shkodër, Malësi, Tivar, Ulqin).

Kuzeydoğu Gegçesi (Kosova, Üsküp, Kumanova).

Güneydoğu Gegçesi (Dibra, Gostivar, Tetova).

Borgo Erizzo alt diyalekti (Zara).

Toskça’nın alt diyalektleri:

Doğu Toskçası - Vjosa’nın doğusu (Berat, Korça).

Labçe - Vjosa’nın batısı (Vlora, Gjirokastra).

Çamçe - Güney Arnavutluk ve Kuzey Yunanistan.

Arnavut İtalyanlarının alt diyalekti (Arbëreshler).

Gibi durumların olduğu söyleniyor. Tabii ki diğer taraftan diyalektler arasında birkaç fark daha var. Örneğin,

Ses bilgisi farkları:

Gegçede burunlu ünlüler kullanılırken, Toskçada bunlar yoktur (ör. zâ – zë; bâj – bëj).

Gegçede uzun ünlüler fonolojik bir değer taşırken, Toskçada bunlar bulunmaz.

Morfoloji farkları:

Gegçedeki -sha, -she geçmiş zaman çekimleri, Toskçada -nja, -nje olarak bulunur (ör. punojsha – punonja).

Toskçada fiillerin belirli bir eki korunurken, Gegçede bu ekler kaybolur (ör. hapur – hap).

Sözlük ve sentaks farkları:

Gegçede, Osmanl�� Türkçesinden alınan kelimelerde vurgu sondan bir önceki hecede (káfe), Toskçada ise son hecede bulunur (kafé).

Gegçe kelimelerinin sonundaki sesli ünsüzler Toskçada sessizleşir (ör. elb – elp, zog – zok).

Bu gibi birkaç örnek vermek istedim. Bu bilgileri bir haber sitesinde okudum. Bunları anlayacak bir şekilde size aktarmak istedim. Unutmayın buraya yazdıklarımın yanlışlık payları olabilir. Umarım bilgilerinize bilgi katacak bir yazı olmuştur.

1 note

·

View note

Note

Curious, did you know about Albanian Sworn Virgins when you designed Third Options? Since it strikes me as a very similar phenomenon down to the fact that while obviously saying very interesting things on matter of gender and identity. I believe some of the people who were interviewed were very candid on how they would have just lived as women in a more liberated society.

Yep! Long ago I did a bunch of research on this idea, and came across them. It's gonna sound goofy (and it is) but my original inspiration for the concept was a conversation I had with some friends about "geek" being the third gender. For some reason I felt really passionate about this idea and I started to dissect why it hit me so hard. I was pretty young and no one was talking about nonbinary people yet but I think it's the same thing; we just didn't have the vocabulary at the time.

But anyway, Alderode has a recognition of a type of woman for whom their gender is secondary to their passion or ability. This cannot be allowed to influence society, so their gender is "corrected," and the result supposedly benefits everyone.

It's turning a hyper specific "I'm not like other girls!" into public policy. As a social band-aid, it seems to be doing the job, but who knows how long it'll stick when the influence of the rest of the continent can only grow.

38 notes

·

View notes

Note

Beevean, what did find hardest when learning a language? I need to gather information since one of my characters is having trouble learning a language and it's rules, so I thought it would be good to ask someone who went through that experience.

The rule of thumb is that you're going to struggle with grammatical principles and words that are not similar to your native language (or languages that you're fluent in)

I know that when Americans study Spanish, they generally have a hard time wrapping around grammatical genders, because they don't exist in English anymore. Other Romance language speakers have no trouble with it, although at worst what is masculine in one language may be feminine in the other, and viceversa. Or, when I vaguely dabbled into Korean, I noticed that it had a similar sentence structure as Japanese: I had already learned the "noun-particle-object-particle-verb" structure, so that was a passage I could skip.

I also noticed that English speakers struggle with Japanese's very simple phonetics, because they're used to a much wider range of wovels. Personally, that was very easy for me. However, I did struggle to learn the R sound (which sounds something like a mix between L and the D/T in American - pudding in Japanese is purin lol) and sometimes I forget to pronounce the H sound, which doesn't exist in Italian but it exists in English.

Sometimes, and I mention it in case you want to add a similar detail to your character, the problem might be completely personal! I have a slight defect of pronunciation: I have never learned to make a rolling R sound, which is the standard in Italian. My Rs are all pronounced at the back of my throat. Helps me a lot with English and French! I also never fell into the trap of saying R in Japanese when the sound is more similar to L/D! Very annoying in Spanish, though, which has the same sound in words with RR.

As for the rest, it depends from person to person. I enjoy learning grammar more than I do vocabulary lol. Grammar is usually logical, and it makes me picture putting blocks together to form a construction. (I may have been lucky of course lol) Vocabulary... well, if you're learning a language similar to your own, you have to look out for false friends. If you're learning a language completely alien from your own, then it's little more than brute force memorization. But this is my perspective: many people I knew hated grammar more than vocabulary lol, precisely because for them it was a bunch of rules to memorize. (then again i'm the weirdo who was good at math in school, that might have influenced me...)

And, of course, you have to practice. Often. Both actively, by speaking and writing, and passively, by reading and listening. Depending on the language, this can be easy or excruciatingly hard. Needless to say that if you're learning English, Spanish or Japanese, resources throw themselves at you lmao. Learning Albanian? Haha, good luck :)

I think I covered everything I could? I hope it was useful!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The votes and placement a country gets do matter actually. If you place low, you only have two options: 1) double down on your ethnicity and not give a shit about winning or losing next year, or 2) translating to English, and I hope it is not the second, because English fucking sucks for some countries.

So maybe Sweden has songs that are written in English to begin with, but the usual Albanian pipeline (bc we keep songs strictly Albanian when competing bc such is our taste) is translating an Albanian song into English lyrics that don't fit for shit bc songs are a lot like poetry: prose can translate the essence bc it can take three sentences when the original took one; poetry has to go by translate line by line and cannot add more lines, and the rhtymn gets all messed up bc the utterances of a language actually do matter a lot in poetry.

I do feel a lot of our earliest entries placed for shit because we kept trying to globalize into English for broader appeal and the English lyrics didn't fit the rhythm or tempo of the song, let alone fitting the original meaning.

(I discovered that translating Albanian poetry into English also sounds choppy, and could be bc we have too many little words to indicate emotional states that, while English has a larger vocabulary for specific words, don't get translated well in English or would require 2-3 lines to do so.)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

me earlier: "okay the majority of this language's vocabulary will be from proto-Italic and proto-(Indo-)Iranian"

me now: "hehe more caucasian albanian words please"

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

It still ultimately happened because of him, but most Romance vocabulary in English actually comes from the Angevin period (12th-13th centuries) and are sourced from the Old French of Anjou (where they were from) and in many cases compete with words sourced from the Old French of Normandy in the Norman period (11th-12th centuries)

The earlier Norman words preserve a hard c before a where the later loans palatalise it to ch (e.g. earlier Norman castle, much later chateau, and much earlier chester~cester~caster), similarly Germanic words that re-entered English via earlier Norman retain the original w, whereas the later Angevin words show the gu- we see in French today (e.g. Norman wardrobe, the first part of which is also identical to the inherited word ward vs Angevin garderobe which contains the later borrowing guard instead)

Also, the examples here are quite poorly chosen. Animal is the only one of these words that isn't (probably) Germanic:

Dog is usually said to be of uncertain origin, but its use predates the Norman invasion, and it's formation seems parallel to other animal names like frog and pig which are found throughout West Germanic making an early origin pretty likely (although it only became the general term much later), it's probably derived from an adjective meaning "dusky"

Die is found throughout Germanic (albeit in a slightly different form in Gothic), albeit alongside many other verbs. It's only in the early modern period that it fell out of use in continental west germanic (it is retained in Scandinavian though, where it has always been the most common verb for death, likely the reason for its prominence in English). Whilst the use of die as the usual word for the end of life is an innovation in English (or possibly a recurrence of the earlier state), it's presence is an instance of English being more conservative than continental Germanic

Tree is extremely old, it's one of the most easily reconstructible Proto-Indo-European words (cf, in various formations, Hittite taru, Greek drus, Sanskrit dāru and dru, Old Irish dair, the dru- of druid, Old Church Slavonic drěvo, Albanian dru, etc all with the meaning of "tree"). The loss of this word (except in some compounds) is an innovation in (some of) continental west germanic. English is actually much more conservative here

So, overall, of the four examples given, only one is a romance borrowing, and two are actually instances of continental west germanic being the one to change (in one instance alongside a change within English)

so the thing about english is that people think it's so divorced from other germanic languages based on like. words. I've even heard people try to insist that english is a romance language. because of that whole messy business in 1066 with out-of-wedlock willy and his band of naughty normans. and now a good chunk of the vocabulary is french or whatever and they're prestigious so not using them makes you sound like a rube and this and that and the other

and yes william the conqueror will never be safe from me. I will have my revenge on him. he fucked up a perfectly good germanic language is what he did. this will be me in hell

but the thing is that most words in, say, german do have a one to one english equivalent. not all hope is lost, for those who still dare to see it. it's just that you 1066pilled normancels aren't looking in the right place

dog (en) ≠ der Hund (de) but der Hund (de) -> hound (en)

look with your special eyes. that one was easier. not all of them are this intuitive because of semantic narrowing and broadening and waltzing and hokey-pokeying and whatever else. I'll give you a few more

animal (en) ≠ das Tier (de)

aha! you think. I've got him on the ropes now.

but then

das Tier (de) -> deer (en)

nooooo!! you whine and cry in gay baby jail. the consonants are different!!! listen to me. listen, I say, putting both my hands on your shoulder. /t/and /d/ are the same sound. you just put your voice behind one of them.

nooooooooo!! you wail. deer are animals but not all animals are deer!!! listen to me. LISTEN. they used to be. animals used to be deer. that's just what we called them. it was a long time ago. it was a weird time in all our lives. it's okay.

let's try for a verb this time

to die (en) ≠ sterben (de) but sterben (de) -> to starve

same principle with the consonants, we're just changing a stop (where we completely stop the airflow and then let it through) for a fricative (where we still let some air go through. idk where it's going. maybe to its job or something.)

to starve used to mean generally to die, not just to die of malnourishment. we do that a lot. we take one word for a lot of things and make it mean one thing. or take one word for one thing and make it mean a lot of things. this is common and normal.

"okay but roland," you say, suddenly coming up with an argument. "what about tree? trees are super common. I don't think we'd fuck around too much with that. the german word is baum! what about THAT?"

"when did you learn german?" I ask, but then decide it isn't relevant right at this very moment. but fine.

tree (en) ≠ der Baum (de) but der Baum (de) -> beam (en)

beam??? you ask incredulously. beam???? BEAM?????? you continue with the same tone and cadence of captain holt from brooklyn 99.

yes. beam. like the evil beams from my eye I'm going to hit you with if you don't stop shouting.

but the vowels!!! you howl.

listen. listen to me. the vowels mean nothing. absolutely nothing. they're fluid like water. it got raised in english.

"WHAT DOES RAISED MEAN"

it doesn't matter right now. they were raised better than you, at least. stop shouting. open your eyes and see what god has given you. they're the same word.

"they're NOT the same word. they mean different things!"

we've been over this. they didn't used to. a beam was (and is) a long solid piece of wood. much like the long solid piece of wood I showed your mother last night.

FAQ:

Q: could english be some kind of germanic-romance hybrid?

A: do you become a sexy thing from the black lagoon just because you dressed up as one for halloween? english may have gotten a lot of vocabulary from norman french, but its history and syntax are distinctly germanic. that's what we base these things on.

Q: okay but what does it matter? this doesn't actually affect my day to day life

A: you come into my house? you come into my house, the house of an autistic man living in vienna austria and studying english linguistics and you ask me what does it matter? sit back down. I was going to let you go but now I have powerpoints to show you

Q: you're stupid and wrong and gay and a bad person

A: I know it's you, Willy

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

The vastness of Peter Constantine’s personal linguistic range is almost unimaginable to most of us. He moves with ease between German, Modern Greek, Italian, Russian, Afrikaans, French, Ancient Greek—and those are just the languages I happen to know about. It’s no surprise that the Times asked Constantine to review Michael Erard’s book about hyperpolyglots, Babel No More—only that Erard didn’t feature him in it.

Peter is also a terminal speaker of Arvanitika, a severely endangered language of Greece related to Medieval Albanian. That has led him to engage with endangered languages in Europe and across the world. Primarily known as a literary translator, Constantine generally translates into English, but has also recently published a Greek translation of works by Polish poet Grzegorz Kwiatkowski.

Lately he’s been channeling his talents in new directions. He is Professor of Translation Studies at the University of Connecticut, and director of the Program in Literary Translation there, which he founded several years ago. He is also the publisher of the new press World Poetry Books, which exclusively publishes foreign language poetry in English translation.

This April Constantine’s kaleidoscopic debut novel, The Purchased Bride came out from Deep Vellum. The central figure in its shifting perspectives is Maria, a young Greek peasant forced to flee with her family across the mountains of the Ottoman borderlands in eastern Turkey when her village is invaded and ransacked in the spring of 1909.

A precise and visceral study of what imperial heteropatriarchy does to children who have no hope whatsoever of escape, the novel has all the vivid, telling detail of a war documentary, while the empathetic love that suffuses its portrait of Maria makes it unexpectedly buoyant. We know from the beginning that she will survive no matter what she faces.

In celebration of The Purchased Bride’s publication, I asked Peter a few questions about the throughlines between life, fiction, and translation.

*

Esther Allen: What’s it like to live in such a magnificently expansive linguistic universe?

Peter Constantine: Growing up with many languages was a helter-skelter sort of experience. I was born in England but spent my childhood in Austria and Greece—mainly Greece. We were a large family, and my parents and grandparents all spoke different languages, each insisting that I only speak their language to them. Battling this was my father, who was a passionate naturalized Brit of Turkish origin. (His Turkish background was a family secret never to be mentioned in public.)

He insisted that I speak only English. He had been a British major in World War II, and the fact that my Austrian mother and I spoke exclusively in German irked him no end. He hadn’t fought Rommel at El-Alamein only to have to hear the language of the enemy spoken at his dinner table. My parents’ marriage was one long battle, and my mother’s campaign tactics were to speak exclusively in German and to turn his household into a Germanic one, with German parties, German books, German friends, a German priest.

Dad was not pleased that I spoke Greek either. He felt that every word of Greek or German I knew would trounce an English one, banishing it from my vocabulary, compromising my prospects of growing up to be a British gentleman: a man of leisure in a Savile Row suit driving a Jaguar and sporting an Etonian British accent. In fact, he had me registered at Eton minutes after I was born, which in the 1960s was still the done thing among the British upper classes from which his Turkish background categorically excluded him.

EA: So it was your family’s extreme linguistic intransigence that inadvertently trained you in hyper-versatility? Did you end up attending Eton? I can’t imagine they were any less intransigent there….

PC: I never thought of it that way, but you are right! My family was utterly inflexible when it came to language. Not to mention, none of them would tolerate any foreign words bobbing up in anything I might say to them. As for Eton, that was not to be. I passed the exams and was accepted, but my father went bankrupt and left home rather suddenly at just about that time, when I was ten years old.

We had lived all those years in a British and Germanic expat bubble in Kolonaki, a privileged and beautifully manicured Athenian neighborhood, and then my mother and I ended up as illegal aliens in one of the shanty towns outside Athens. It was a worrying but very exciting new way of life: one was never sure if there would be enough food to eat, and though we had a tap, there was only water for one or two hours a day. The shanty town was a wild, unzoned area of red mud and olive trees and open fields with shacks and Romani tents.

There, the true language adventure began. Since time out of mind the area had been an Arvanitic region, and so Arvanitika, one of the non-Greek languages of Greece, was still spoken there, as was Romani whenever the large Roma families would arrive with their orange Datsun pickup trucks and pitch up their tents for a month or two.

EA: How long did you and your mother live in the shanty towns?

PC: All in all, about ten years. But two of those I spent in England, from eleven to thirteen where Dad had moved after the divorce. The plan was still that I would somehow go to a good boarding school like Eton, but since Dad had gone bankrupt I ended up in an inner-city school in London instead.

I arrived there like little Lord Fauntleroy, impeccably dressed and with a posh British accent, since I’d gone to the British Embassy school in Athens. It was a Catholic school, but boys were throwing switchblades at the blackboard, and girls—eleven and twelve years old—would head to the train station during recess to make some pocket money.

Two things happened immediately: I exchanged my posh accent for that of a rough Londoner, and I started saving pennies, one at a time, till I had 24 pounds, which was enough for a bus ticket back to Athens. My father, now in his mid-sixties, had married a nineteen-year-old Iranian girl. I was about to say “woman,” but she was a teenager, and people assumed that she was my fifteen- or sixteen-year-old sister. The marriage was a disaster, and she escaped to France, my father in hot pursuit.

Since by then I had gathered my twenty-four pounds, I used the opportunity to escape to Greece. It is remarkable in retrospect that back in the mid-seventies, with the bus crossing all those European borders on its four-day journey to Athens, none of the passengers or border guards wondered why a thirteen-year-old was traveling unaccompanied.

EA: Was that when you learned Arvanitika, after you got back to your mother in Athens, in the shanty towns? And did you learn Romani, as well?

PC: We lived along a dirt track just off the old road to Mount Pendelikon, which is where the marble for the ancient temples of Athens came from. The mountain has gaping holes from millennia of excavations. Greek was the main language spoken there, but also Arvanitika. Our landlord was a man in his late thirties, and I was surprised that he had trouble speaking Greek.

By then, in the mid-seventies, almost everyone was bilingual, and Arvanitika was beginning to fade. I had been exposed to Arvanitika from an early age, since in the 1960s my parents had bought a house in an old Arvanitic village near Lake Stymphalia, where Hercules had fought the murderous Stymphalian birds.

In the shanty town, there was a lot of Romani in the air, but the Roma remained within their communities and just pitched their tents for several weeks at a time. There was something like a seasonal flow of different Roma groups staying for a while and then moving on. At my school we had a choice between Ancient Greek and Sanskrit, and I chose Sanskrit.

I was very surprised to come across familiar Romani words in class. When the Roma, for instance, say “Dzhanas Romanes?”—”Do you know Romani”—the Sanskrit word for “you know” is dzhanasi. It’s the same word. It was news to me that the Roma might have come from India—in fact the Roma didn’t know that either. But there were so many words in common.

EA: You did have formal schooling during this period, then. In Greek?

PC: I didn’t have a Greek education. I ended up going to Campion, one of the international schools of Athens. The headmaster was a fascinating figure, Jack Meyer. Very British, and very eccentric. He had teachers from all over the world. His first suggestion was that I take Vietnamese classes, that the school would see to it that I could “pass for Vietnamese” by the time I graduated. I was intrigued, but hesitated. His ultimatum was that I must choose Vietnamese or Russian.

I chose Russian. There was an interesting mix of students. My best friend Natasha’s grandparents had fled Russia during the Bolshevik revolution; she spoke an elegant and aristocratic Russian at home. Among our classmates were also the children of Eastern Bloc diplomats. Natasha’s mother, Lily, was a fascinating figure. We were very close, and she introduced me to the Russian classics.

EA: The narrator says on the first page of your novel that the main character, Maria, is his or her (we never find out much about that narrator) grandmother. It’s a work of fiction, clearly, but this seems to indicate, perhaps, some sort of autobiographical inception. What sort of connection did you have with your own grandmother?

PC: The Purchased Bride is indeed a novel and not a memoir; but it is based on my grandmother’s story and that of other women of my Turkish family. My father, who read the first draft, felt that it was very accurate, which surprised me, as I had changed names and places, and had invented characters and situations.

He in fact considered it a sort of biography. I never understood whether what he actually meant was that I had captured the vital essence of my grandmother’s story. I felt that it had to be that. But either way, he recognized the portraits of his mother and his father.

The first glimmers of The Purchased Bride came some twenty years ago, a good two decades after I had left Greece. I was translating the Complete Works of Isaac Babel at the time. It was not that my work on Babel triggered the novel in any way, but that period was when I first wanted to reach back into my family’s Turkish background. It had to be in a fictional way, as my father—and my aunts in the UK—had turned their backs on their Turkish past and would never admit to it.

One aunt had even married a Greek man, who throughout their many decades of marriage never knew she was Turkish. I always found that most puzzling. I wondered what had happened in the 1920s and 1930s to have caused this complete rupture, and their extreme attempts to reinvent themselves as Europeans. As a young man my father kept changing his name—to Turkish names at first, and then Greek ones. He also kept changing his age: he was born in 1920, but also in 1919, and 1915. He had paperwork and passports to prove it. Finally, he confessed that he was born in 1914.

All this in an attempt to escape the past that I touched on in the novel. I tried to research my father’s past, looking through archives and records, but he had managed, quite remarkably, to make any official paperwork that pointed to his birth, or provenance, or schooling disappear. His sisters had done the same. The first sign of my father was as a modern European man, Major Constantine of the British army in Egypt.

As for my grandmother, she died in 1976 in Cyprus, as a result of the violent ethnic cleansing that forcibly moved Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot populations into the Greek or Turkish sectors of the island. The irony is that though my grandmother was old and infirm and originally Greek, she was considered Turkish because of her marriage, and so was expelled by force from the Greek part of the island.

I never met her, as she was part of the Turkish past that my father did his utmost to avoid. And to think that we lived in Athens all those years, a two-hour flight from Cyprus.

EA: You began looking into your family history while translating Babel—but that was not what triggered your interest. What role do you think your career as a translator did have in the writing of this novel?

PC: Gregory Rabassa, a great mentor to a whole generation of translators, famously said that translation is the purest form of writing. It is one of the joys of translation that you can put all your energy into writing: the translator of a novel need not focus on the nuts and bolts of creating characters or developing narrative structures. The main creative focus can remain on how something is said or narrated.

After translating the works of Isaac Babel, I signed a three-book deal to translate a contemporary German author I greatly admire; but as I put pen to paper I found to my dismay that I was having trouble connecting with his style and with the plot movements of the novel. It turned out that we were not an ideal fit. Translating these books was a struggle, and I had a great urge to change the directions of the plot, to take charge of what the characters might do or say.

I successfully resisted, but this urge inspired me to work on my own novel, where I would be free to make my characters say and do what I wanted. I haven’t been similarly tempted since, but that was a great inspiration for my own work.

EA: Hmmm…. I think I know which books you are talking about. Fantastic that translating novels you had serious quibbles with was the catalyst for writing one of your own. Novelists, beware: your translators are learning from you and may outdo you…

Beneath the polished, finely crafted surface of The Purchased Bride is a complicated and intricate criss-cross of languages and cultures. Almost every figure we meet speaks a different group of languages, and the novel beautifully and with great subtlety represents the way its characters are constantly confronting linguistic difference and doing their best to communicate across it. And of course you wrote it in a language none of its characters speak. Were you very conscious of that as you were working on it?

PC: I didn’t consciously give my characters each their own language—but it was very much the way things were in those turbulent borderlands of Asia Minor. Turkey is linguistically quite diverse, and the Ottoman Empire was even more so. Maria, the protagonist, was expected to become Turkish and Moslem, and to shed her old identity, and never speak Greek again.

There was a trend among Ottoman gentlemen of a certain class to have wives who were not Turkish. One of the underlying fears was that Turkish girls were already formed, and might have meddling families, while foreign girls could be molded to fit a husband’s or master’s taste. For centuries Caucasian, Russian, or Greek girls in their early teens would be purchased and cultivated to be ideal Ottoman wives, or concubines, or servants.

The worry that a girl might seem unattractive and suspect if she knows Turkish or any Turkic language is a recurring theme in the novel. Maria, who speaks Tatar relatively well—a Turkic language that is perhaps as similar to Turkish as Dutch is to German—has to keep pretending that she knows only Greek. But through her knowledge of Tatar she can often follow what is being said in Turkish throughout all the transactions that lead to her being purchased.

EA: Did it feel natural to write it in English? Or did you feel the other languages you speak, Greek and Turkish, particularly, tugging at you, annoyed with you for not consecrating your talents to them?

PC: It did feel natural. Throughout the years I have mainly written in English and translated into English. Though I consider Greek to be one of my native languages, I know very little Turkish. In a strange way I hear the language and feel it, but I don’t speak it.

Yet my peculiar connection to Turkish does manifest itself in the novel in oblique ways. I had fun translating some of the newspaper articles of the day spinning out conflicting information about the rumors and scandals that fascinated and delighted Ottoman society of 1909. For instance, the story of the glamorous Madame Claudius Bey who had been murdered “on the high seas” for her priceless pearl necklace.

After years of striving to be meticulous in my translations I now went at these texts with total abandon, understanding some of the phrases, guessing at others, looking up this and that word, recreating the confusion and excitement of an early-twentieth-century reality show.

EA: Your portrayal of Maria skillfully captures what it is to be a valuable piece of human merchandise. She’s a full and complex human being to the reader, but to the people around her, including her own family, her beauty is basically her entire worth. Aside from her luck in the DNA lottery, the other physical asset that confers value on her is her virginity, something we know she has no control over whatsoever.

PC: My father always felt that his father had shown great kindness to my grandmother in marrying her: a sophisticated middle-aged man condescending to show interest in an insignificant little girl. My grandmother was actually thirteen, not fifteen, as Maria is in the novel. It is perhaps a harsh thing to describe my father’s attitude to his mother in this way, but it was entirely a cultural matter.

Beauty and virginity were the only two important elements. If either of those had been missing, my grandmother would not have been acceptable. Wit, to some extent, was important too, a worthwhile quality if it could amuse, but unacceptable if it was to be used to challenge the husband or master.

On reflection, I believe I wrote The Purchased Bride as an antidote to this unyielding patriarchal mindset, which though it belonged to an obsolete, if colorful and intriguing, late-Ottoman society, seemed still so prevalent in the southern European cultures that I grew up in. As a first-generation American literary translator, editor and writer, I felt far enough removed from my European, Greek, and Turkish past, for me to reach back and write a novel that in some ways was connected to that life.

0 notes

Text

Albanian War Vocabulary

Fjalori i luftës në shqip

luftë - war

paqe - peace

perandori - empire

perandor - emperor

monark - monarch

sundimtar - ruler

mbretëroj - reign

mbret - king

kurorë - crown

shtet - state

betejë - battle

fitore - victory

Zot - God

shenjë - sign

pushtet - power

i fuqishëm - powerful

i dobët - weak

i fortë - strong

tradhti - betrayal

aleancë - alliance

besnikëri - allegiance

drejtësi - justice

pushtim - conquest

ndikim - influence

ushtri - army

kalorës - knight

vras - kill

vdekje - death

vuaj - suffer

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Witchy Albanian Vocab.

Inspired from @noonymoon who made one for German. You can check that out here.

THE ELEMENTS / Elementet

fire - zjarr

water - ujë

air - ajër

earth - tokë

spirit - shpirt

WITCHCRAFT / (no translation)

witch - shtrigë

magician - magjistar

wand - shkop magjik (lit. magic stick)

broom - fshesë

chalice - kupë

crystal - kristal

candle -qiri

cauldron - kazan

bell - zile

incense - temjan

potion - ilaç

charm - hajmali

amulet - hajmali (same term is used)

talisman - hajmali (same term is used for all three)

spell - magji, formulë magjike

curse/hex -mallkim

banishment - syrgjynosje, dëbim

divination - parashikim

POSITIVITY / POZITIVITET

fertility - fertilitet

fidelity - besnikëri

peace - paqe

protection - mbrojtje

destiny - fat

memory - kujtesë, memorie

contentment - kënaqësi

happiness - lumturi

enthusiasm - entuziazëm

awareness - ndërgjegjësim

friendship - miqësi

admiration - admirim

acceptance - pranim

prosperity - begati

abundance - bollëk

health - shëndet

empathy - ndjeshmëri, empati, prekshmëri

harmony - harmoni

knowledge - njohuri

beauty - bukuri

courage - kurajë

healing - shërim

wisdom - mençuri

success - sukses

energy - energji

curiosity - kuriozitet

dreams - ëndrra

friends - miq

pets - kafshë shtëpiake

animals - kafshë

truth - e vërteta

trust - besim

goals - qëllimet, synimet

love - dashuri

luck - fat

joy - gëzim

THE SIGNS / SHENJAT

aries - dashi

taurus - demi

gemini - binjakët

cancer - gaforrja

sagittarius - shigjetari

capricorn - bricjapi

aquarius - ujori

pisces - peshqit

leo - luani

virgo - virgjëresha

libra - peshorja

scorpio - akrepi

SOLAR SYSTEM/ SISTEMI DIELLOR

earth - Toka

sun - Dielli

moon - Hëna

mercury - Mërkuri

venus - Afërdita/Venusi

mars - Marsi

saturn - Saturni

uranus - Urani

neptune - Neptuni

pluto - Plutoni

EMOTIONS / EMOCIONET

hope - shpresë

euphoria - eufori

passion - pasion

compassion - dhembshuri

serenity - qetësi, kthjelltësi

freedom - liri

CREATIVITY / KREATIVITETI

poetry - poezi

poet - poet

poem - poemë

poetic - poetik

writing - shkrim

writer - shkrimtar

artistic - artistik

art - art

(to) paint - pikturoj

(to) draw - vizatoj

drawing - vizatim

painting - pikturë

(to) photograph - fotografoj

fantasy - fantazi

imagination - imagjinatë

surreal - surreal

(to) create - krijoj

FLOWERS / LULE

daisy - margaritë

peony - lulegjaku, bozhure

carnation - karafil

tulip - tulipan

sunflower - luledielli

gerbera - margaritë

orchid - orkide

iris - iris

lilac - jargavan

gardenia - gardeni

jasmine - jasemin

magnolia - manjolë

hyacinth - zymbyl

lily - zambak

poppy - lulekuqe

violet - vjollcë

wildflowers - lule fushe

petals - petale

thorns - gjemba

ANIMALS / KAFSHËT

wolf / wolves - ujk/ujqër

owl - buf

bat - lakuriq nate

cat - mace

dog - qen

bird - zog

fish - peshk

rabbit - lepur

bear - ari

tiger - tigër

lion - luan

leopard - leopard

cheetah - gatopard

raccoon - rakun

otter - vidër

deer - dre

butterfly - flutur

moth - flutur nate

fox - dhelpër

raven - korb

frog - bretkosë

horse - kalë

NATURE / NATYRA

forest - pyll

woodland - pyjor

earthy - tok

flame - flakë

bonfire - zjarr (i madh)

mother - nënë

nature - natyrë

cosmos - kozmos

universe - univers

stars - yje

moor - kënetë

WITCHY / (no translation)

enchanting - magjepsës

enchanted - i/e magjepsur

supernatural - mbinatyror/ i mbinatyrshëm

fairy - zanë

fairies - zana

elf - elf

unicorn - njëbrirësh

wish - dëshirë

wise - i mençur

celestial - qiellor, hyjnor

mythical - mitik

magical - magjik

(to) bewitch - magjeps

spiritual - spiritual

spirit - shpirt

soul - shpirt

soulmate - shpirt binjak

twin - binjak

psychic -psikik

sigil - sigil

seal - vulë

wax - dyll

#albanian studies#albanian#albania#vocabulary list#albanian vocabulary#albanian vocab#vocabulary#vocab#languages#llanguage#languageblr#language blog#langblog#langblr#polyglot#ultilingual#bilingual#studyblr#education#study

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

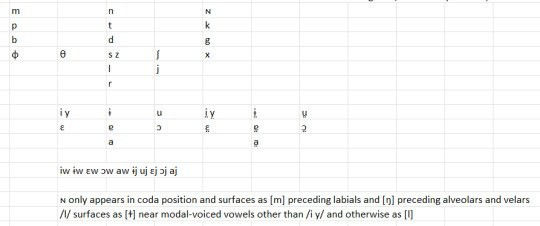

so I made a language by putting proto-indo-european in a blender and leaving it on the liquefy setting for an afternoon

Yeah.

Today I'll be describing my hypothetical Indo-European conlang Bèhsráto. It's an isolate within the family, but there's considerable influence from Slavic languages, Latin, Greek, and a bit from Albanian and Hungarian, mostly in the form of loaned vocabulary.

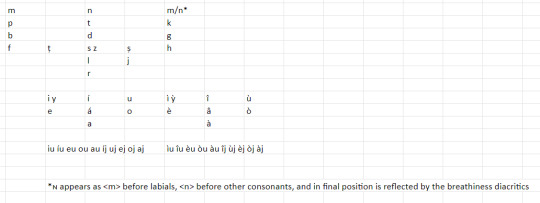

PHONOLOGY

I made a lot of interesting decisions here.

Breathiness in vowels spreads forward in a word except when there's a consonant cluster, then it's blocked. ɴ arose from breathy vowels via rhinoglottophilia, i.e. V̤ > Ṽ > ɴ, in stressed syllables and at the end of words.

Consonant clusters can get a little crunchy, though at the beginning of words they're fairly limited to s or ʃ followed by a voiceless stop, z followed by a voiced stop, an obstruent and then a sonorant, a cluster of a stop and then a fricative of the same voicing, or just about any sequence of /x/ and then another consonant. For one example of a crunchier consonant cluster, the name of the language is pronounced [bɛ̤xsrɐtɔ]. Stress is ...weird, but typically on the penult (as here) or the antepenult.

Bèhsráto is a satem language, meaning the Proto-Indo-European palatal stops shifted to fricatives and affricates and the labiovelar *kʷ *gʷ *gʷʰ merged with k g gʰ. The word for hundred is státo [stɐto]. (For a while, the postalveolar affricates the palatal stop series yielded surfaced as retroflex sounds, and some very strange things happened to some of them, yielding these st- or zd- clusters.)

Another fun note: Bèhsráto retains the laryngeals from Proto-Indo-European as /x/ in some environments. This is where a lot of those weird initial clusters involving /x/ come from. *h₃mígʰleh₂ surfaces as hmáglej [xmɐglɛj] "fog", *h₃rḗǵs as hris [xris] "king", *h₂ékʷeh₂ as hakoj [xakɔj] "drinking water", and so on.

ORTHOGRAPHY

I decided to write this language with the latin script like a basic bitch. I'm kind of assuming it's spoken on the coast of the Black Sea, but I didn't put a ton of effort into the history, I was more interested in bullying the phonology and grammar until they took a new, strange form. I could justify using Cyrillic or Greek alphabet for this but I didn't want to think about it, so I simply didn't.

GRAMMAR

This is where I did some of my weirder things.

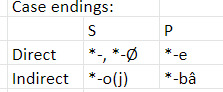

Bèhsráto is a topic-prominent language. It retains a nominative, accusative, genitive, and dative case in pronouns, but in most nouns there is only the direct (serving the roles of both nominative and accusative) and the indirect (a catch-all for all others, most often clarified via prepositions). Word order is topic-initial.

Here's the personal pronouns:

In ...most... of these, four cases remain distinct. The genitive serves double purpose as an ablative, and the dative is also a locative and instrumental.

The topic marker agrees in animacy, number, and case with the marked noun:

The topic marker developed from a historical definite article. The historical indefinite article developed into a sort of indirect particle that can apply to the indirect object for emphasis when it isn't the topic, singular form ojno, plural ojna.

Also here's the case endings:

Direct case means it's either the subject or the object; indirect case means it's anything else. The direct case is a -j suffix when the noun ends in o, else it shifts any final vowel to o or is a suffix. Adjectives agree to the noun in case and number, i.e. șrego "darkness" en șregoj in darkness-IND "in darkness" en țonákoj șregoj in hellish-IND darkness-IND "in hellish darkness" (these examples are very My Immortal, I know, don't @ me)

The verb agrees to the topic of the sentence and so has direct and inverse endings to mark which is the agent and which is the patient. More on that later. For now let me crack out a few example sentences to explain just what is going on here:

Sa testu teset legâsna TOP.DIR carpenter make-PST.3S.DIR bed "The carpenter made a bed"

Tod legâsna testor testu TOP.DIR bed make-PST.3S.INV carpenter "It was a bed that the carpenter made"

Basically, since word order is determined by the topic and not by who's doing what, the verb has different endings to determine which noun serves which role.

Now let's do something with an indirect object:

Sa hmoj dâgantèr zgome esto per ojno dzero TOP.DIR 1S.GEN daughter ride-3S.IPFV.DIR horse through IND gate-IND "My daughter is riding a horse through the gate"

The particle "ojno" here adds a degree of specificity and secondary emphasis to the noun it's marking; this is an example of the way the indirect case operates, where it's part of the constructions that use prepositions.

Now let's mark this gate as the topic:

Per tod dzero hmoj dâgantèr zgome esto. through TOP.DIR gate-IND 1S.GEN daughter ride-3S.IPFV.DIR horse "Through the gate is where my daughter is riding a horse"

In this case, the indirect object is fronted and the old SVO default word order is returned.

Now let's get into some of the uses of the indirect case.

The possessive construction uses the preposition hapo "off, away" and places the possessor noun in the indirect case, i.e. hneumo hapo táranoj "the name of the tyrant".

Other constructions that deal in origin use the preposition haz "from", i.e. záuro haz poloj "the man from the city"

There's a benefactive-type construction using the preposition pro "leading to", i.e. dèștâ pro Aținoj "altar for Athena"

There's a locative construction using en "in", i.e. en Ațínoj "in Athens" (btw that's not a typo, the name of the city and the name of the goddess are a minimal pair of /ɨ/ and /i/)

There are two instrumental-type constructions, one for a living thing and one for a tool: jágo estoj "with a horse"; zájzdo nehábâ "with boats". (It took me this long to use literally any plural? shame.)

So that's basically nouns.

VERBS

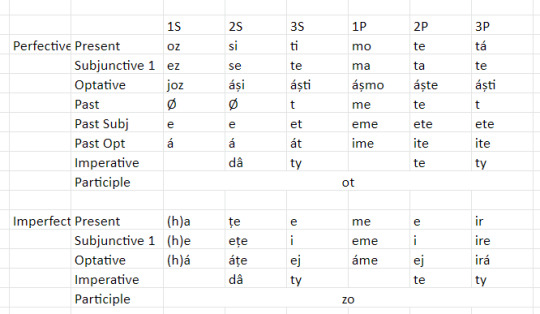

I'm going to drop tables for the direct endings and the inverse endings, and then things get weird. Basically these are suffixes, but they'll tend to replace the last vowel of the root. Not always, but often.

Direct endings:

"Subjunctive 1" refers to the fact that I have two things I couldn't come up with a better label for than "Subjunctive" and the number just differentiates between them. Subjunctive 1 is a bit softer, deals in hopes, preferences, etc, in a way that's adjacent but distinct from the optative, and subjunctive 2 is needs, ought statements, etc.

"Direct" here means that the topic is also the subject, or that the topic is the indirect object and the order of subject, object, and verb is the default SVO.

Inverse endings:

"Inverse" here means the topic is the object. The personal agreement is still based on the subject of the sentence, but this means it's not the topic.

Now, there are several tenses that affix after these endings:

Example: Ṣediștâ eat-3S.DIR-SUBJ2 "He needs to eat" (Note here that the t in the 3S.DIR ending, normally -ti-, is lost here because of the voiced stop.)

These five suffixes are actually derived from converbs, which function in a rather similar way.

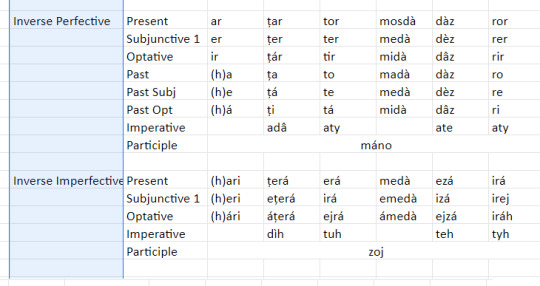

CONVERBS

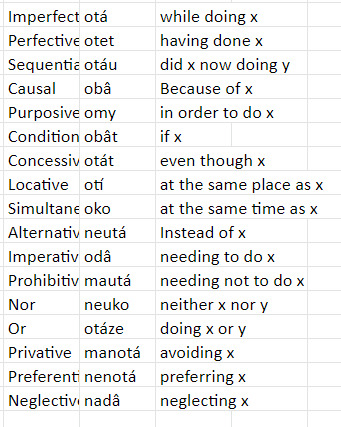

Here's each converb suffix and its main meaning:

These can have broader meanings than the above; I just listed the basic ones to save a bit of space here. Going into what each of these does would be annoying as hell for the purposes of a post like this. Anyway, let's crack out an example sentence or two:

Ṣedáneutá hmá, taj haște ze stejgìr ha ojno bèjzdo. eat-3P.DIR-CONV.instead 1S.ACC TOP.P bear-P REFL.IND climb-3P.IPFV.DIR on IND.S hill-IND "Instead of eating me, the bears are climbing on a hill."

(I use the reflexive and a locative construction here because the verb stejgè "climb, march" doesn't take an object, and specifically the indirect reflexive because they're using their body to do an action and not really doing it to themselves.)

Zorozmautá, zdo tetol hmoj zdensèrè ne henáko. stir-1S-CONV.NEG.SUBJ 1S.NOM hold.up-1S.DIR.PST 1S.GEN hand-P NEG breathe-1S.DIR-and "Needing not to move, I held up my hands and didn't breathe"

(When they are subject, pronouns are by default the topic and need not be marked if in topic position. Also, the suffix -ko is "and" or "any", and the suffix -zi means "or", and these can apply to nouns, verbs, and adjectives. Also, particle ne is one of the negation pathways. There are three, more on that later.)

AUXILIARY VERBS

There are two auxiliary verbs, bỳh "to become" for the future tense and hajs "to have, to obtain" for the past perfect tense. The auxiliary verbs take the endings and the main verb is in participle form. An example of each:

Zdo bỳhoz hládòt h'Afroditeu en Sofijo 1S FUT.1S.DIR.PERF arrive-PTCP.DIR on Friday in Sofia-INDIR "I will arrive in Sofia on Friday"

(Here the preposition ha "on" is cliticized. That happens with initial vowels. Also, weekdays are derived from the names of Greek gods. Aphrodite gets Friday. A note that's not super relevant to this example but seems useful to include: Saturday, Kroníu, can also be Síbota, or "sabbath", and which is used varies some by region but Síbota is universally far more popular among devout followers of Abrahamic religions.)

Sa Aleksada hajsti zejdot sjo zásto. TOP.DIR Alexander have-3S.DIR find-PTCP 3S.GEN dog "Alexander has found his dog."

NEGATION

There are three forms of negation. The general one is the particle ne. It negates verbs, serves as an answer, etc.

Another, now primarily a derivational form, is the prefix o(n)-, meaning "without", "not", etc. Example: zásteto "holy", ozásteto "unholy"

The third is the command form, the particle ma. Example:

Ma se zejdâ! NEG.IMP REFL tremble-2S.IMP.DIR lit. "Do not tremble", basically "B̴̻̐͑̚Ȇ̵̱͔͘͜ ̵̳͂Ṉ̷̙͑͘O̶͎̫̮̾T̴̪̺̉̈́ ̷̬͕̬̔Ã̷̛̜͒Ḟ̸̳̺̯R̶̝̒̈Ȃ̵͉͓̎̒I̷̠͚͊̓D̴̡͛̇͘͜" as a biblical angel might say. bèjà is a general term for "to fear, to be afraid"; se zejb- is a way of saying the same thing that is intense and often has religious connotations.

INTERROGATIVES

it question tiemn binch

That's right, we have quite a stack of question words. Several that take more than one word in English, and singular and plural forms. The question word is generally going to be the first thing in the sentence.

kí/ko here is a term that shows up in questions that aren't covered by these others or can function as "What?" as in asking for clarification, repetition, etc.

A couple of examples:

Kosmud gomosi? where.from come-2S.DIR "From where have you come?"

Ska sa proruka șesti? who TOP.DIR prophet be-3S.DIR

RELATIVE CLAUSES

Relative clauses use the relative pronoun, singular jo plural je, and sometimes an appropriate interrogative. I'll give just one example because anything is able to be relativized.

Example:

Taj goneje je zejd hmoj hagno hajsir zesezo halbè zeste TOP.DIR woman-P.DIR REL.P find-PST.3P.DIR have-IPFV.DIR.3P wear-PTCP.IPFV white-P clothes-P "The women who found my lamb were wearing white clothes"

It's technically also correct to render this as Taj goneje je kítaj zejd hmoj hagno but it's not mandatory.

REFLEXIVES

There are two reflexive, a direct and an indirect one, se and ze respectively.

Let's bring back the times I used these and talk about the reflexives specifically a little bit more.

Ma se zejdâ! NEG.IMP REFL tremble-2S.IMP.DIR "Be not afraid!"

Se is used for an action done directly and consciously to oneself; in this case, since when angels issue this as a command it implies agency over one's own fear, it qualifies.

Ṣedáneutá hmá, taj haște ze stejgìr ha ojno bèjzdo. eat-3P.DIR-CONV.instead 1S.ACC TOP.P bear-P REFL.IND climb-3P.IPFV.DIR on IND.S hill-IND "Instead of eating me, the bears are climbing on a hill."

Ze carries less intentionality in contexts like the above, but is also an indirect form. The action is, in this case, technically without object, so you use the indirect reflexive.

And that basically sums this thing up. Here's a translation I had a lot of fun with.

Cave Johnson's announcement about mantis men

Ysmá je benhpreste pro taj DNAje hapo bugolmoka inikermedà zej, zdo taj zese zerde trejsteko dàr. DAT.2P REL.P volunteer-2P.PST.DIR towards TOP.P DNA.P off mantis inject-1P.SUBJ.INV 1P | 1S TOP.P excellent.P word-P sad.P-and give-1S.INV To you who volunteered so that we would inject you with the DNA from a praying mantis, I give happy words and sad ones.

Trejstá, taj teste prolatomosdàștâ hed telo hapo tímpo. sad TOP.DIR.P test-P delay-1P.INV-SUBJ2 until end off time.IND Sadly, we must delay those tests until the end of time.

Zesá, sa nezo test hajsmosdà ysmá: Jy bỳhțe keutásnezo serkáty zdánáto bugolmoke-záure. excellent TOP.DIR new test have-1P.INV 2P.DAT | 2P become-2P.DIR.IPFV fight-DIR.IPFV.PTCP army made.of mantis-P man-P Happily, we have a new test for you: You will be fighting an army made of mantis men.

Gàbàdâ pușka; sa zdèlò șejter seksadâ. take-2S.IMP rifle | TOP.DIR yellow path follow-IMP.INV.2S Take a rifle; follow the yellow line.

Ty bỳhsi zojdot jo kídeh sa test kene. 2S become-2S.DIR know-PTCP.DIR REL when TOP.DIR test begin-3S.IPFV.DIR You will know when the test is starting.

#conlang#i stabbed proto indo european right in the left kidney and this is the result#"B̴̻̐͑̚Ȇ̵̱͔͘͜ ̵̳͂Ṉ̷̙͑͘O̶͎̫̮̾T̴̪̺̉̈́ ̷̬͕̬̔Ã̷̛̜͒Ḟ̸̳̺̯R̶̝̒̈Ȃ̵͉͓̎̒I̷̠͚͊̓D̴̡͛̇͘͜#cave johnson

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Someone saw this and offered to teach me Spanish swears

Who else wants to teach me to swear

If you're not living your life trying to get kicked out of the Vatican are you even truly living

#I know like 2 swears in Russian#I think only one in Albanian#A couple in mandarin#Help me expand my vocabulary

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

나라와 언어 어휘 - Country and Language Vocab

It’s been such a long time since I provided a vocabulary list! In my final year of university, I have to do a lot of language reports that result in me comparing and contrasting a lot of language families (this usually includes sociolinguistics to typology). I thought that I could do a blog related to the countries and languages! This might not be an entirely comprehensive list. If I missed your country, let me know and I will add it! Enjoy <3

나라; 언어 - 번역 // Country; Language - Translation

대한민국/한국; 한국어 - Korea; Korean

중국; 중국어 - China; Chinese

일본; 일분어 - Japan; Japanese

태국; 태국어 - Thailand; Thai

독일; 독일어/히브리어 - Germany; German/Hebrew

러시아; 러시아어 - Russia; Russian

베트남; 베트남어 - Vietnam; Vietnamese

영국; 영어 - England; English

캐나다; 영어/프랑스어 - Canada; English/French

미국; 영어/스페인어 - America; English/Spanish

멕시코; 스페인어 - Mexico; Spanish

프랑스; 프랑스어 - France; French

스페인; 스페인어 - Spain; Spanish

인도; 힌디어/영어 - India; Hindi/English

이탈리아; 이탈리아어 - Italy; Italian

헝가리; 헝가리어 - Hungary; Hungarian

가나; 영어 - Ghana; English

그리스; 그리스어 - Greece; Greek

뉴질렌드; 영어/마오리어 - New Zealand; English/te reo Māori

덴마크; 덴마크어 - Denmark; Danish

레바논; 아랍어/프랑스어 - Lebanon; Arabic/French

루마니아; 루마니아어 - Romania; Romanian

말레이시아; 말레이시아어 - Malaysia; Malaysian

모로코; 아랍어 - Morocco; Arabic

브라질; 포르투갈어 - Brazil; Portuguese

스웨덴; 스웨덴어 - Sweden; Swedish

스위스; 독일어/프랑스어/이탈리아어/로만슈어/라틴어 - Switzerland; German/French/Italian/Romansch/Latin

아일렌드; 아일렌드어/영어 - Irish/English

알바니아; 알바니아어 - Albania; Albanian

이란; 페르시아어 - Iran; Persian

자메이카; 영어/파톼 - Jamaica; English/Patois

케냐; 영어/스와힐리어 - Kenya; English/Swahili

파키스탄 - 우르두어/영어 - Pakistan; Urdu/English

타이완/대만; 중국어 - Taiwan; Chinese

Some other important vocab:

언어 - language

표준어 - standard language

사투리 ~ 방언* - accent/dialect

우리말 - our language

외국어 - foreign language

대륙 - continent

동양 - the east

서양 - the west

아시아 - Asia

동남아시아 - Southeast Asia

유럽 - Europe

아프리카 - Africa

북아메리카 - North America

남아메리카 - South America

오세아니아 - Oceania

*사투리/방언 - while it’s generally assumed these are interchangeable, depending on a certain context, they can mean different things. 사투리 refers to the actual regional differences, whereas 방언 can include social differences and slang!

Like I said before, if I missed your country/language, let me know and I will add it!! Unfortunately, this list does not include Indigenous languages - but I am willing to do the extra research to find out more!

Happy Learning :)

~ SK101

#korean#korean language#korean language blog#korean langblr#korean blog#kblr#klangblr#countries in korean#languages in korean#korean vocab#korean culture#k vocab#한국어#한국어 공부하기#한국어 배우기#한국어 어휘#한국#한국어 블로그#study korean#learn korean#korean vocab list#sk101#나라와 언어 어휘

257 notes

·

View notes

Text

European languages vocabulary in Finnish

Albania - Albanian Armenia - Armenian Azeri - Azeri, Azerbaijani Baski - Basque Bosnia - Bosnian Bretoni - Breton Bulgaria - Bulgarian Englanti - English Espanja - Spanish Eteläsaame - Southern Sámi Friisi - Frisian Fääri - Faroese Gaeli - Scottish Gaelic Galicia - Galician Georgia - Georgian Grönlanti - Greenlandic Hollanti - Dutch Iiri - Irish Inarinsaame - Inari Sámi Islanti - Icelandic Italia - Italian Jiddiš - Yiddish Katalaani - Catalan Kiltinänsaame - Kildin Sámi Koltansaame - Skolt Sámi Korni - Cornish Kreikka - Greek Kroatia, kroaatti - Croatian Kymri - Welsh Latina - Latin Latvia - Latvian Liettua - Lithuanian Luulajansaame - Lule Sámi Luxemburg - Luxembourgish Makedonia - Macedonian Manksi - Manx Malta - Maltese Montenegro - Montenegrin Norja - Norwegian Oksitaani - Occitan Piitimensaame - Pite Sámi Pohjoissaame - Northern Sámi Portugali - Portuguese Puola - Polish Ranska - French Romani - Romani Romania - Romanian Ruotsi - Swedish Ruteeni - Rusyn Saksa - German Sardi - Sardinian Serbia - Serbian Sisilia - Sicilian Skotti - Scots Slovakki - Slovak Sloveeni - Slovene Sorbi - Sorbian Suomi - Finnish Tanska - Danish Tataari - Tatar Tšekki - Czech Turjansaame - Ter Sámi Turkki - Turkish Ukraina - Ukrainian Unkari - Hungarian Uumajansaame - Ume Sámi Valkovenäjä - Belarusian Venetsia - Venetian Venäjä - Russian Viro - Estonian

#Finnish#suomi#polyglot#languages#langblr#languageblr#language blog#langspo#tongueblr#studyblr#vocab#European languages

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

langblr playlists

Hi everyone!!

Listening to music in my target language(s) always helped me a lot with pronunciation, vocabulary and use of language, so i’ve decided to share my playlists that each focus on one language!

My playlists on Spotify and YouTube.

A Albanian Amharic Arabic (+ variety groups) Armenian Aymara Austrian German

B Bambara Basque Belarusian Bosnian Bulgarian

C Cantonese Chuvash Croatian Czech

D Dutch

E Estonian

F Farsi Finnish French

G Georgian German Greek Greenlandic

H Hindi Hungarian

I Icelandic Indonesian Inuktitut Irish Italian

J Japanese

K Khmer Korean Kurdish Kyrgyz

L Latvian Lithuanian

M Mandarin Māori

N Norwegian

P Panjabi Polish Portuguese

Q Qazaq Quechua

R Romanes Romanian Russian

S Serbian Sámi Slovak Slovene Spanish Swiss German

T Tagalog Tamashek Thai Turkish

U Ukrainian Urdu

V Vietnamese

W Welsh

X Xhosa

Y Yoruba

Z Zulu

Bonus: AAVE

Big playlist with non-English songs only: click here

🚧 "Pipeline" aka playlists I'm working on (recs needed)

💖 Drop non-english songs you think I need to listen to in my inbox!

😖 Not your taste? Have a look at these playlists by other creators! (g0ogle sheet). Want to go hunting and gathering yourself? Try these resources.

❗ Disclaimer: these playlists may contain different dialects that may not be mutually intelligible/may vary from the dialect that you're learning. I therefore encourage you to ask about any uncertainties. I will try my best to answer your questions or to crowdsource answers.

‼️ Sometimes I mess up! Kindly send me an ask if I have. 🩵

Many thanks to everyone who has directly or indirectly contributed to this project:

@lesbianmangoes @orzamara @yibo-wang @jackisblu @malfunctioningsublime @kreideprinz-studies @holochromatic @arag0ns, @quatregats @sandushengshou @highwarlockkareena @lan-xichens @aheartfullofjolllly @sovietunions @surnudring @nonenglishsongs @kristina100000 @tomirida @metamorphesque @hexenmond various anons and many other people <3

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Proto-Slavic and Proto-Germanic are the reconstructed proto-languages - ie, what the ancestor of modern languages belonging to those families (Russian, the languages of the Balkans, for Slavic; English, German, the Scandinavian languages for Germanic) might have looked like. They were created by looking at cognates between languages within those languages and determining what sound changes might have taken place to get a word in one language to be different from another. It should be noted that Proto-Slavic and Proto-Germanic are both descended from Proto-Indo-European, meaning that, technically speaking, English is related to Russian.

Anyhow, that is where this language I am making comes in; I created it out of boredom, and the vocabulary and things like conjugation and declension comes mostly from Proto-Slavic and Proto-Germanic, though there are also words of Middle Chinese, Proto-Albanian (another Indo-European proto-language), and Egyptian, for a bit of flavour.

So, many words in my language, which I've called Nimełwu, or "new language", that look like English words, or words you might be familiar with if you speak a Germanic or Slavic language, are, in fact, more than likely actually related.

2 notes

·

View notes