#alacrity fitzhugh

Text

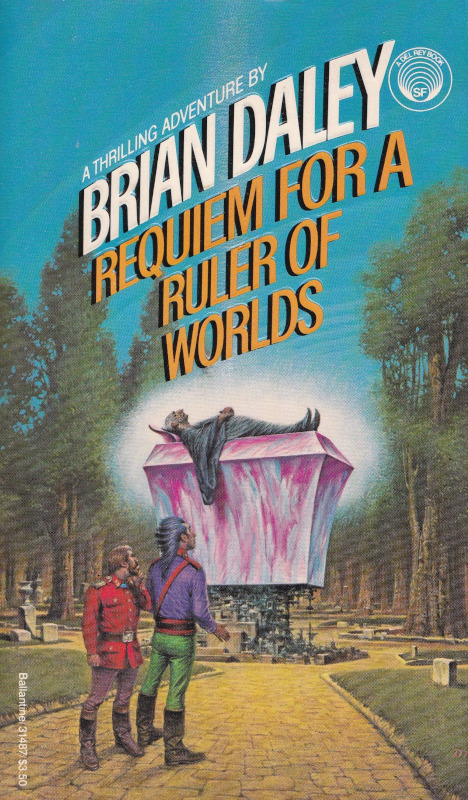

April 1985 to January 1987. One half of the pseudonymous "Jack McKinney" who wrote the prose ROBOTECH novels, Brian Daley is probably best known for his trio of delightful Han Solo novels, first published in 1979–1980, and for scripting the NPR radio adaptations of the STAR WARS movies. However, he also wrote a bunch of original sci-fi and fantasy novels, including this entertaining mid-'80s trilogy about the misadventures of Hobart Floyt and Alacrity Fitzhugh (a pseudonym, although his real name isn't revealed until the third book).

Centuries in the future, Hobart Floyt is a low-level functionary in the administrative bureaucracy of the oppressive Earth government. When he's unexpectedly named in the will of Caspahr Weir, the ruler of a minor but very wealthy interstellar empire (whom Floyt has never met), Earthservice decides Floyt must attend the reading of the will, expecting to confiscate whatever bequest he might receive. Since Floyt is a sheltered Terran who's never even contemplated going off-world, Earthservice coerces Alacrity, a young part-alien "breakabout" (starship crewman for hire), into becoming his guide. Thus begins a series of picaresque adventures through the diverse, colorful worlds beyond closed and xenophobic Earth. The first book focuses mostly on our heroes' journey to Weir's throne world, Epiphany, and the many ways they almost get killed prior to the Willreading. The second book deals with Floyt and Alacrity attempting to actually collect Floyt's inheritance — a starship to which Weir has left him title, but not actual possession — and figure out why Weir left it to him in the first place. The final volume shifts focus to Alacrity's quixotic quest to become the captain of the White Ship, a fabulously advanced starship intended to search for the secrets of an ancient alien race called the Precursors, which is also an object of fascination for Floyt and Alacrity's bitterest enemy: Dincrist, the father of the woman Alacrity falls in love with in the first book.

Anyone who enjoys Daley's Han Solo novels will probably also like these books, which are similar in tone and style: droll, action-packed romps starring two likable schmoes who spend a lot of their time running for their lives, with richly detailed settings full of exotic alien creatures and engaging if rather two-dimensional characters. These novels' literary merits are modest, but Daley's object was lighthearted pulp fiction, as evidenced by an amusingly self-reflexive subplot in the second and third books: Our heroes' friend Sintilla, a freelance journalist, starts publishing a series of extremely popular penny dreadful novels starring heavily fictionalized versions of Floyt and Alacrity (without their knowledge or approval) in wild adventures even more outrageous than their real ones. This soon makes the real Alacrity and Floyt inconveniently notorious — leavened slightly by the fact that the handsome male models depicted on Sintilla's book jackets look nothing like them!

(Ironically, this is also true of the covers of more recent editions of these books. Darrell K. Sweet's covers for the original Del Rey paperbacks, shown above, are reasonably close to how the characters are described in the text — although the gawks they're riding on the cover of the third book are all wrong — but the current versions aren't even within walking distance of the right ballpark.)

#books#brian daley#darrell k sweet#requiem for a ruler of worlds#jinx on a terran inheritance#fall of the white ship avatar#hobart floyt#alacrity fitzhugh#the han solo adventures#space opera#the gawks (which are sentient herbivores) have six legs#and resemble a cross between a giraffe and a triceratops#what sweet painted is not that#although their hide seems about right#jack mckinney

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louise Fitzhugh’s Harriet the Spy was unsurprisingly one of my favorite books as child, since like Harriet, I was precocious and lonely but also just mean and convinced of my own intelligence in a way that girls in flowered dresses aren’t supposed to be.

For far too long, I had a public blog where I’d write about my classmates without even altering their names since I rationalized that if they wanted me to speak kindly of them, they should have behaved better (a la Anne Lamott). I wasn’t ever wrong about my observations, but I was cruel in my alacrity to condemn them for what they did and for that matter, who they were.

I haven’t named names in my public writing since March of 2017 not because I magically realized that it was wrong to be cruel to others in a place where they and their friends could see it, but because I suffered interpersonal consequences for my behavior with regards to my relationship with someone I loved. In other words, like Harriet before me, I’m not sorry for what I said, which was unfair to say albeit true, but for the repercussions of what I said, which are still hurting me today.

I'm not sure if that makes me an unforgivably bad person or not, but that's how it is.

8 notes

·

View notes