#aedicula

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Reims Stela (Autel de Reims) is one of the more impressive and complete survivals of Cernunnos iconography.

Because the weathered stone is so dull, I've always wanted to see it restored to its former polychromy glory — so I experimented with some digital colorization!

#reims#cernunnos#polychromy#polytheism#paganism#gaulish#horned god#mercury#apollo#aedicula#pagan altar#gaulish polytheism#roman polytheism

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aedicula containing a painted Athena and Agathodaemon

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Secrets of Christ's Tomb | SPECIAL | National Geographic

19 April 2025

National Geographic tracks a team of experts as they race to repair the structure housing Christ’s tomb. Evidence of the tomb’s origins are revealed.

Secrets of Christ's Tomb: Explorer Special | S1, E1

#Youtube#Secrets of Christ's Tomb#jesus#jesus christ#tomb#national geographic#nat geo#holy week#holy week 2025#lent#lent 2025#lenten season#Church of the Holy Sepulchre#cross#crusader's cross#calvary#holy site#christianity#faith#Aedicula#ancient relic#emperor constantine the great#st helena of constantinople#discovery#evidence#tomb of christ#edifice#sacred sites#jerusalem

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The house has an irregular layout consisting of two originally independent units being united. The atrium area almost entirely preserves the original decoration dating back to the last period of the city; the upper part, consisting of painted blocks of rows, is well preserved. A marble table resting on legs in the shape of winged lions is found at the edge of the impluvium.

The rear part consists of richly decorated rooms formed around the portico and the central garden, dedicated to gatherings or receiving guests. The life-size images of Bacchus and Venus are painted on the walls of the exedra, and the central area of the floor of the triclinium is embellished with inlaid coloured marble.

There is an aedicula on the back wall of the garden, where there is the lararium for family worship.

Date of excavation: 1896-1897.

View of the lararium from the portico in the "House of the Prince of Naples", Pompeii.

Photo: Luigi Spina

#history#classics#architecture#archaeology#roman mythology#ancient rome#roman republic#italy#campania#pompeii#house of the prince of naples#lararium#portico#atrium#impluvium#exedra#triclinium#aedicula#bacchus#venus

378 notes

·

View notes

Text

ALEJANDRO CESARCO. Three Books on Memory

Tre note a piè di pagina di un testo mai scritto dell’artista uruguaiano Alejandro Cesarco in mostra alla Galleria Cortese di Albisola

1 note

·

View note

Text

A Scythian goddess on Apulian vases

These are five vases likely showing the elusive Scythian ancestral goddess.

I love the floral imagery, but I’m also frustrated that I can’t find much information about the tendril-limbed female figures. I’m fairly certain that these images, aside from the siren, depict the Scythian ancestral goddess, but I can’t find any art historians who specifically discuss the figures. I’ve found several articles that talk about the vases in general, but they only focus on the flowing vines and the main scenes, not on the likely Scythian deity herself.

Apulian red-figure oinoche, about 350-320 BCE. Photo by courtesy of Dr. Matthias Recke, University of Giessen, Antikensammlung Museum. Photo via Peter on Flickr.

This vase could also be a siren, the lovely singers of Homeric fame. While the other Scythian goddesses only have wings, this woman has bird feet. Sirens were bird-bodied women to ancient Greek artists. However, this siren is unusual as her tail feathers curl out on either side of her, like the Scythian ancestral goddess’s tails do.

Apulian Red-Figure Loutrophoros about 330 B.C. Attributed to the Painter of Louvre MNB 1148 (Greek (Apulian), active 350 - 330 B.C.) Info from Getty Museum.

This woman has wings, a basket on her head like the Vergina mosaics of the Scythian goddess, and a dress like the Carytids in the Thracian Tomb of Sveshtari, Bulgaria, except her upper body is topless. The lower part of the vase shows the mourning of Niobe.

The figure is described but not identified in: Occasional Papers on Antiquities, Greek Vases In The J Paul Getty Museum. An Apulian Loutrophoros Representing the Tantalidae. By A.D. Trendall. 1985. Pages 140-41, fig, 14.

Winged woman with tendrils, likely the Scythian goddess. Apulian red-figure vase, about 340 BCE, Varrese Painter; Antikensammlung Kiel, inventory number B 724. Picture taken by Marcus Cyron via Wikipedia.

This woman also has wings, a basket on her head, and the distinctive curling chiton dress like other Scythian goddess figures wear. She’s mentioned in the article “Half-Human Half-Vegetal Hybrids in Eastern Mosaics” which does talk about Scythian goddess imagery, but the author doesn’t specify that this is an image of the Scythian goddess.

Likely Scythian goddess, Baltimore painter, loutrophoros with wedding scenes, about 325-320 BCE. Matera, Museo Archeologico Nazionale. Photos via Saiko on Wikipedia.

Our next goddess has a different style dress, and much more elaborate tendrils— but she also has wings and perhaps a basket on her head. It’s interesting that most of these goddesses have bare toros, as she Scythian goddess is usually shown with a full dress.

We also have a confirmation that this imagery is related to the Scythia goddess, in an article on her imagery:

“The female winged deity with lower part of the body resembling a palmette or acanthus leaves is a widespread image on Apulian vases. Two characteristic examples are the “Niobe” amphora (4th century BCE) from Naples, featuring an aedicula stepping on a base decorated with several such figures (20) Fig 7 and a case which was sold at Christie’s in 1979, dated to the last decades of the 4th century BC.” (Valeva 1995.)

This article could be referring to the Getty vase, as they're both showing scenes with Niobe. Image from Baggio 2013.

The figures are also described in a chapter about Scythian goddess imagery, by Ustinova, on page 103:

“In Italy, the chthonic symbolism of this goddess was conspicuous: on an amphora from Neapolis, featuring a Niobids-scene, Niobe is portrayed in a naiskos, its foundation decorated with a group of tendril-limbed winged figures, calathi on their heads (Curtius 1958: fig. 33).

Update: I found one more example of this motif on a vase here.

Sources.

Valeva, Julia. “Valeva-1995 The Sveshtari Figures (An Attempt to Specify Several Hypotheses).” Thracia 11, Studia in honorem Alexandri Fol, Sofia. (1995): n. pag. Print.

DERWAEL, Stéphanie. “Half-Human Half-Vegetal Hybrids in Eastern Mosaics.” Journal of Mosaic Research, no. 16, 2023, pp. 89–110, https://doi.org/10.26658/jmr.1376718.

Heuer, Keely. “Tenacious Tendrils: Replicating Nature in South Italian Vase Painting.” Arts, vol. 8, no. 2, 2019, p. 71, https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020071

Baggio, Monica. “Sistemi Di Immagini, Sistemi Di Oggetti Le Loutrophoroi Del Pittore Di Baltimora.” Cahiers « Mondes Anciens », no. 4, 2013, https://doi.org/10.4000/mondesanciens.1072.

Ustinova, Yulia. The Supreme Gods of the Bosporan Kingdom: Celestial Aphrodite and the Most High God. Boston: Leiden, 1999.

#twin-tailed siren#mistress of animals#ancient greek art#mistress of beasts#scythian goddess#apulian vase#red figured vase#potnia theron#greek mythology#greek myth art#sirens#greek art#ancient art

259 notes

·

View notes

Text

Minerva

Aedicula depicting Minerva, 2th/3th century, limestone, 30x20x12 cm (Gallo-Roman period)

Collection du Musée National d’Archéologie, d’Histoire et d’Art Luxembourg (MNAHA) Inv. 0234

138 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Ancient Synagogue in Israel & the Diaspora

A unique and fundamental aspect of ancient Judean society in both Israel and the Diaspora, the ancient synagogue represents an inclusive, localized form of worship that did not crystallize until the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE. In antiquity, there was a variety of terms that represented the structure, although some of these were not exclusive to the synagogue and may refer to something else, such as a temple. These terms include proseuchē, meaning "prayer house" or "prayer hall"; synagoge, meaning "a gathering place"; hagios topos, meaning "holy place"; qahal, meaning "assembly"; and bet kneset or bet ha-kneset, meaning "the house of gathering". The oldest term, proseuchē, originated in 3rd century BCE Hellenistic Egypt and clearly identifies a key characteristic of the structure: prayer. Although Torah reading set the synagogue apart from other public buildings or places of worship, much like the Temple before it, the Torah was not the only defining feature of the synagogue. Other distinctive traits included the activities that took place within them as well as the art and architecture of the structures themselves.

The Role of the Ancient Synagogue

Inscriptional and literary evidence suggests that judicial proceedings, archives, treasuries, prayers, public fasts, communal meals, and lodging for traveling Judeans were all associated with the ancient synagogue. The public reading and teaching of the Torah took precedence over all else by providing the liturgical activity that set the synagogue apart, but the synagogue was much more than a religious institution and must be considered as distinctly different from its predecessor, the Temple.

Following the destruction of the Second Temple and the rise of Rabbinic Judaism, a more democratic form of worship began to take root, as well as concepts such as urbanization and institutionalization, which spread throughout the Roman, and later Byzantine, Empire. With the end of the Second Temple period came the end of the practice of sacrifice, and so the reading of the Torah filled the void. As a result, the Ark of Scrolls and the Torah shrine developed, eventually emerging as the focal point of the synagogue, representing a symbol of survival and preservation. Nearly every ancient synagogue in the land of Israel yields traces and fragments of a Torah shrine, either in the form of a raised platform as a base for the aedicula, a niche, or an apse. This evidence demonstrates the significance of the Torah shrine as one of the few consistent features within the ancient synagogue. Yet the appearance of the Torah shrine was not the only emergent trait accompanying the rise of Rabbinic Judaism. Unlike the exclusivity of priestly-mediated ritual attributed to the Temple, the participants in the ancient synagogue were involved in the performance and conducting of ceremonies, reciting prayers, and reading from the Torah. A new participatory nature of worship was developing during this period, and it is preserved through the architectural remains.

As the rabbinic class rose in power, criteria that may be deemed "non-religious" began to fall under the control of the rabbis, and therefore, the "religious" domain. In terms of legal matters, Tannaitic cases may relate to settlements for divorce/widowhood, damages for public shaming, deeds dating on the Sabbath, and so on. Despite the fact that other venues were available for resolving legal matters, the rabbinic judges served as an alternate, and seemingly popular, venue. Generally, rabbinic legal activity revolved around property and family issues, which occasionally intersected with ritual law such as in Deut. 5-10 and halîsâ, a ceremony concerning the obligation of a man to marry his brother's childless widow. Quite simply, aside from the reading and studying of the Torah, the separation of religious and non-religious functions is not as clear as one may assume in terms of the activities performed in the ancient synagogue. Whether separate or not, both religious and non-religious activities attributed to the synagogue originated in response to communal requirements, differing in distribution throughout the ancient world with the exception of the study of the Torah, around which the synagogue's ultimate purpose revolved.

As a result of the Torah's dominance in synagogue performance, it seems only reasonable that it would become a popular motif with the rise of Jewish art in late antiquity, and in fact, the Torah Ark would become just that. Yet the Torah's dominance would be expressed by other means as well, such as with the development of the Torah shrine as the focal point and physical statement of Judean religious and historical lineage. Beyond the Torah shrine, however, the ancient synagogue would come to develop additional features and characteristics that reflected communal needs and practices, all of which are evident in archaeological remains.

Continue reading...

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

aedicula/restacks truly most beautiful love story of all time….

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Modi eligendi papam per conclave #SRE #Conclave #SedeVacante http://youtube.com/ProVaticanus http://www.zazzle.com/provaticanus/Sede+Vacante+gifts Conclave (-is, n.; e verbis cum clave) est in primis pars domus velut cubiculum quae (ut nomen dicit) clave clauditur, deinde conventus collegii cardinalium Ecclesiae Catholicae papam eligendum ab aetate nova plerumque cardinales in Aedicula Sixtina ad deliberandum secedunt. Electors formerly made choices by accessus, acclamation (per inspirationem), adoration, compromise (per compromissum) or scrutiny (per scrutinium). With acclamation, the cardinals would unanimously declare the new pope quasi afflati Spiritu Sancto (as if inspired by the Holy Spirit). If this took place before any formal ballot has taken place, the method was called adoration, but this method was excluded in 1621 by Pope Gregory XV. To elect by compromise, a deadlocked College would unanimously delegate the election to a committee of cardinals whose choice they all agree to abide by. Scrutiny is election via the casting of secret ballots. Accessus was a method for cardinals to change their most recent vote to accede to another candidate in an attempt to reach the requsite two-thirds majority and end the conclave. This method was first disallowed by the Cardinal Dean at the 1903 conclave. The last election by compromise is considered to be that of Pope John XXII in 1316, and the last election by acclamation that of Pope Innocent XI in the 1676 conclave. http://allmylinks.com/ProVaticanus https://youtu.be/ygKb0As18AI

0 notes

Text

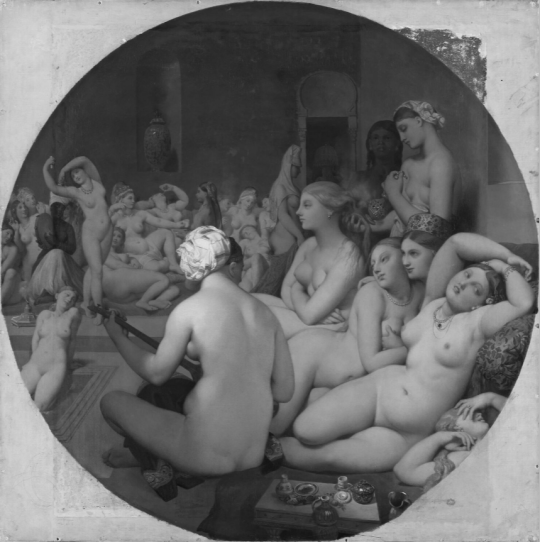

Competition, proposal for museumizing the Roman ruin in Curinga, Italy

I. The Turkish Bath (Le Bain turc) Painting by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres

II. III. IV. V. drawings and visualizations by Jakub Dračka and Betül Peker, 2024

The thermal baths of Acconia di Curinga is a harmonious blend of preservation, innovation, and sensory experience. The structure’s form, when viewed from above, is a testament to the rational grid inspired by the surrounding tree orchards. This grid, mirroring the hypocaust heating system, has been ingeniously translated into a new orchard of red-brown concrete columns, each proportioned differently to mimic the diversity of trees. The ruins themselves are encapsulated beneath an offset roof that not only casts shadows but also echoes the original structure’s shape. A wall, following the roof’s outline, gracefully crawls on the ground, reinforcing the historical silhouette. Roman-inspired windows perforate the roof strategically, allowing natural light to illuminate the interiors. These windows are not mere openings, they serve as architectural elements, transforming each space according to its historical function.

The immersive journey through the structure is facilitated by a path crafted from prefabricated steel, providing a lightweight contrast to the robust brick walls. Positioned close to the walls, it encourages visitors to engage their senses by touching and smelling the ancient materials. The scent of flowers and herbs planted within the small rooms and the garden further enriches the sensory experience. Orange and lemon trees, along with fragrant herbs like rosemary, creates an olfactory landscape. Thermae becomes a sensorial orchestra, playing with the elements of sound, light, darkness, silence, warmth, cold, and water. The frigidarium, filled with water and featuring a large window, exudes a cold and open ambiance. The gymnasium, with its open roof perforation, invites contemplation under the sky. In contrast, calidaria and tepidaria are intimate, dark spaces where small chimney-like windows distribute a subdued light. Aediculas, designed as a contemporary art gallery, adding a modern touch to the historical site. For those who prefer an external perspective, a strategically placed bench offers a shaded vantage point. The architectural design transcends mere visual aesthetics, aiming to engage visitors on a multisensory level, fostering a profound connection between the past and the present.

0 notes

Text

Wall painting on black ground: Aedicula from the imperial villa at Boscotrecase. Period: Early Imperial, Augustan

MET Museum -Public Domain images

473 notes

·

View notes

Text

CLARISSA BALDASSARRI. exposure value

Clarissa Baldassarri si interroga sulla manipolazione delle immagini, i meccanismi di presentazione dell’arte contemporanea e la ricezione delle opere d’arte

0 notes

Text

Architectural Design of the Library, facade roof

.

Statue of Arete ( virtue of excellence; living up to one's potential)

.

The Library of Celsus in Ephesus, Selçuk/Turkey

.

The Library of Celsus is considered an architectural marvel and is one of the only remaining examples of 'great libraries of the ancient world' located in the Roman Empire.

It was the third-largest library in the Greco-Roman world behind only those of Alexandria and Pergamum, believed to have held around 12,000 scrolls.

Celsus is buried in a crypt beneath the library in a decorated marble sarcophagus. The interior measured roughly 180 square metres (2,000 square feet).

[...]

The library is built on a platform, with nine steps the width of the building leading up to three front entrances. These are surmounted by large windows, which may have been fitted with glass or latticework.

Plan of the Library of Celsus

Flanking the entrances are four pairs of Composite columns elevated on pedestals. A set of Corinthian columns stands directly above. The columns on the lower level frame four aediculae containing statues of female personifications of virtues:

Sophia (wisdom), Episteme (knowledge),

Ennoia (intelligence), and Arete (excellence).

The four statues of the female virtues are not originals, but were replaced with four random female statues. These virtues allude to the dual purpose of the structure, built to function as both a library and a mausoleum; their presence both implies that the man for whom it was built exemplified these four virtues, and that the visitor may cultivate these virtues in him or herself by taking advantage of the library's holdings.

This type of façade with inset frames and niches for statues is similar to that of the skene found in ancient Greek theatres and is thus characterized as "scenographic".

[...]

...ancient history ♡

.

#https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Library_of_Celsus#library of Celsus#architectural design#beautiful buildings#ancient#private pics#17. October 2033

0 notes

Photo

Populonia

Populonia (Etruscan name: Pupluna or Fufluna), located on the western coast of Italy, was an important Etruscan town which flourished between the 7th and 2nd century BCE. Rich in metal deposits and so noted for its production of pig iron, it has become known as the 'Pittsburgh of antiquity;' the town was a successful trading port, able to mint its own coinage. 7th and 5th century BCE tombs survive at the site, including large tumuli and square stone aediculae set in rows.

Early Settlement

The earliest archaeological evidence of settlement are the cemeteries belonging to the Villanovan culture (1000-750 BCE), a precursor of the Etruscans. The settlement of Populonia benefitted from its location on the coast where it could act as a trading centre between incoming goods shipped by sea from the wider Mediterranean and export the minerals mined from the interior of Etruria. There were also long-standing trade relations with Sardinia. With its own port in the only Etrurian natural harbour (the Gulf of Baratti), Populonia was the only Etruscan town to be constructed directly on the coast. The Etruscan name for the town - Fufluna - is derived from the Etruscan god of wine Fufluns, and this may indicate viticulture was an early source of wealth. More certain is that Populonia became prosperous based on its production of bronze, using copper and tin deposits found in the nearby hills.

Even more important than all its other resources put together, Populonia was particularly noted as a smelting centre for iron coming from Elba. The island had exhausted its supply of wood needed for charcoal used in the smelting process and so was forced to send iron ore across to the mainland for treatment. It is interesting to note that archaeology has shown that the Populonians did not make the same mistake of mass deforestation. Analysis of charcoal remains at the town show that it typically came from trees which were 20 years old, suggesting there was some forest management and trees were cut on a rotation basis. Iron would bring great wealth to Populonia's ruling class, and as historian J. Heurgon points out, it would make the city as famous in antiquity as Pittsburgh was in the 20th century CE for its steel.

Continue reading...

22 notes

·

View notes