#a shifty tract

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

lads college au

lads headcannons

this is a college au in a normal modern universe (ours). theres no evols. gender neural mc/reader.

masterlist link

caleb

-childhood friend.

-was your neighbor during elementary school before you moved at the start of middle school

-you have two older brothers (name suggestions are welcome! i'm really bad at names)

-he has a younger sister (this isn't mc) who is around 14-15

-he's play's basketball (like in cannon)

-roommates with gideon

-wants to be a pilot and is getting his basics

-average grades

-extrovert

-lives in dorms

-partly on scholarship for basketball (not a full ride)

-runs on quick and cheep junk usually, but knows how to cook and cooks well!!

--------------------------------------------------------

zayne

-started as project partners

-you were passive aggressive at first

-he was just monotone and unbothered

-you have some where between 3-5 siblings with at least one sister.

-he's an only child

-going to be a doctor

-super smart with the bestest of grades

-introvert

-his parents are very supportive

-whiplash seeing zayne (monotone, cold) and his folks (very expressive and warm)

-he lives in a dorm with roomie grayson

-he's on scholarship (full ride)

-mix between healthy meals and quick shit so he can focus on school work

--------------------------------------------------------

sylus

-shifty guy

-met him due to the twin's shenanigans

-speaking of the twins, they are his little brothers.

-they're 16-17 in high school.

-sylus comes from a... wealthy family

-parents have never really been around

-he kind of parent to the twins due to this (poor baby :( )

-mephisto is here (no crow erasure!!) he's his pet tho

-treats him more like a bratty child (lol)

-business major (parents said he was going to college so here he is)

-shit grades (not because he's dumb, but because he does not care)

-introvert

-him and the twins live in a bougie apartment their parents own

-parent's do not live with them or visit

-he cooks healthy meals for him and the twins (growing boys need to eat well!)

--------------------------------------------------------

xavier

-sleepy little guy

-y'all bonded over food and video games

-you're an older sister to a little brother (12-13)

-he also is an only child

-he's undecided (idk what a hunter equivalent would be help! maybe he could be into space?)

-less then average grades

-pretty smart for someone who sleeps through all his classes

-introvert

-his mom is a strict woman (spooky)

-doesn't really talk to her, but she has cash to burn on him for college apparently (def pressured him to go, even if he wasn't sure what he wanted to do)

-he lives in the dorms with roomie jeremiah

-can sleep through all the noise on his floor (somehow)

-probably plays overwatch or valerent

-will loose tract of time playing video games, not helping his sleeping in class

-burns ramen

--------------------------------------------------------

rafayel

-amazing art student (skills!)

-he kind of just adopted you, idk

-you are an only child

-he is an older brother to a little sister named thalia

-she has the same eyes as him, but different hair color (same hair texture tho)

-art major (saaaaame)

-average grades (in academic classes. straight a's in art lol)

-extrovert (but is pretty picky about who he hangs with)

-parents are pretty distant, posh kind of rich

-didn't get to be a messy kid growing up

-has his own apartment with a big fancy bathtub and lots of his works on the wall

-he can cook, but he's lazy, so it's mostly take out unless he feels like it

--------------------------------------------------------

some world building i wanted to get down

a little food before more getting together parts cause they take forever. i was playing through story today, but i can probably finish two tomorrow (maybe. don't get your hopes up, loves)

thank you for reading

-chara <3

#caleb x reader#lads#lads caleb#lads mc#lads rafayel#lads sylus#lads x reader#lads xavier#lads zayne#love and deepspace#rafayel x reader#sylus x reader#zayne x reader#xavier x reader

52 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Some cold-ridden season-two Archi/vists, plus a Mar/tin who’s just trying to be nice. Please don’t track this dirt outside whump and snz tumblr

#nonsearchable tma tag#a shifty tract#anyway BYE i'm going to bed where i have big plans to hide my head under the blankets in shame

61 notes

·

View notes

Note

For the ask game, how would you combine accidental eavesdropping and arranged marriage with JayTim?? :)

58 (Accidental Eavesdropping) + 50 (Arranged Marriage) + JayTim.

Look, Tim didn't mean to listen in. When it comes down to it, he never means to listen in when his parents are having closed-door meetings, but let's be realistic here—if they didn't want him to listen, they would have done something about the unusually thin wall between that particular parlor and the adjacent library as soon as they learned of it.

He thinks he remembered to tell them how thin it is. Probably.

Either way, they brought this on themselves. If they didn't want him to listen in, they should have had this meeting in the parlor on the other side of the house and not the one next to his favorite study location. He was just grabbing a book from the shelf on that particular wall when he happened to overhear his father quite clearly say something about "a mutually beneficial arrangement for both parties" and "our son." At which point he couldn't just walk away and pretend ignorance, because he's not an idiot.

He's pretty focused on trying to get all the details so he can't be blamed for barely registering when the library door opens and someone else comes in.

"What are you doing?"

"Figuring out what kind of future my parents are planning for me. Now, be quiet before I miss anything." He doesn't really know Jason, but they've formed an unsteady truce in the few weeks he's been at Drake Manor as his father's newest live-in secretary.

He's unsurprised when Jason is suddenly right beside him, pressing his ear up against the wall as well. "Are they seriously trying to arrange a marriage? In this day and age?"

"I think so." Tim makes a face. He's only 24, he doesn't want to get married, let alone to some complete stranger, no matter how impressive her tracts of land. Pulling away from the wall, he buries his face in his hands. "Ugh, I hate being an only child. I bet you never had to worry about your parents selling you off to the highest bidder."

"Well. Not necessarily." Jason gives him a somewhat shifty look. "I may have left home because the offers started coming in as soon as my brother was off the market."

"My condolences."

"Which is to say—I have a good idea of how to get out of something like this. If you're interested in trying, I mean."

Tim perks up, his previous despair falling away. "You have my attention. What do I need to do?"

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Time fucked ? ⏱

Oh ! ... i Think the Date's are all Wrong You See as i Was Growing Up, i Went threw A lot of Odd shit very odd shifty Shit, i Used Get Locked in time loop's Like the Ground hog day Movie,

i Used see the Cloud's race out by Window for no reason and i saw the number's on the clock race like a Stop watch And i Heard the Sound's of the people in the House echoing from all side's Many time's, and i Could not Move, i Felt like i Was Melting, Out of Reality.

i kept skipping around and my Age kept getting tossed around from 8 year's old to 9 to 6 to 5 to 7 to 11 over n over i get called a different and the Weather would get all crazy and

i Used to be very good at tracking My Age, even tho it is a Dumb ass thing to do, Put a Number On how old you are

i Don't Think i'm 27, i think i'm 23 i Know it's Odd For some odd reason 4 year of my life Literally went by in a few Month's i'm also Good at tacking time to a Good enough degree and

i feel that time is racing ever since the Mandela Shit on 2012 my time has bin skipping Jumping a lot And Hour on the Clock Act's more like 20 Min's??? i think C.E.R.N fuck up time.

The Week’s go By So fast, i Can’t Keep tract of them, i don’t think there are 24 Hour’s in a Day any more ??? Minuet's are Faster, Second’s are slower yet .. Skip .. if you blink it’s like 9 min’s go by ???

Hour’s feel like Pouring Water out a Glass and before you know 5 hour’s went by in 9 Second’s ???

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

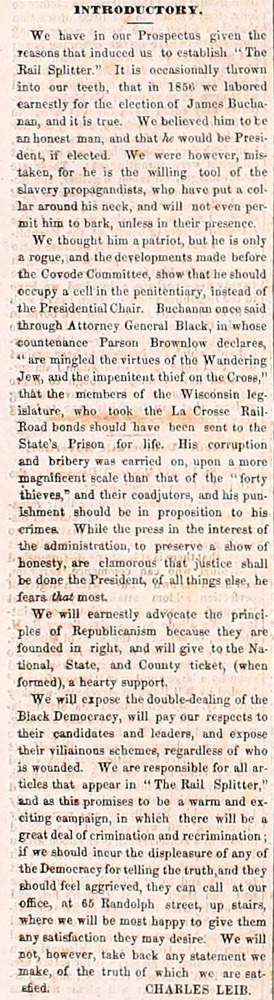

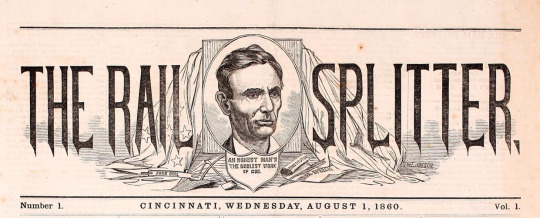

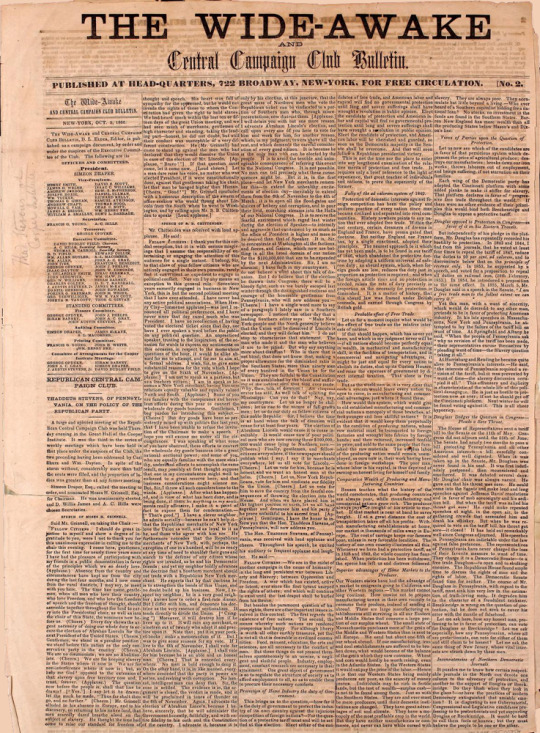

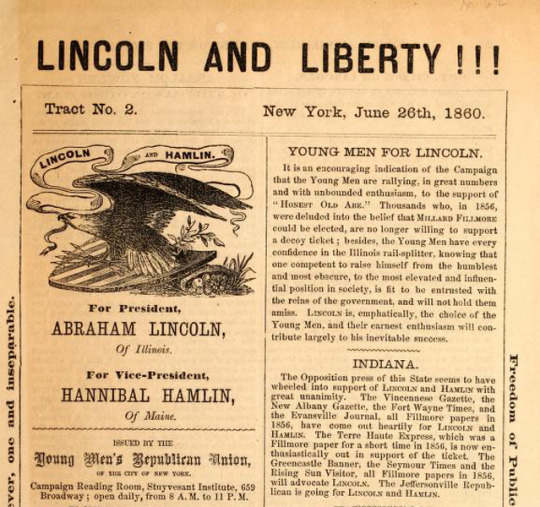

The Partisan Press — Republican Campaign Newspapers in the 1860 Election

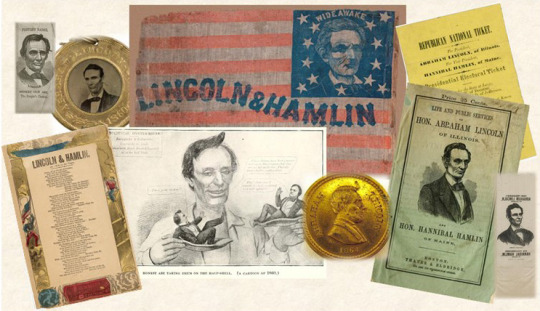

The 1860 presidential campaign, which pitted Republican Abraham Lincoln against Southern Democrat John C. Breckinridge, Northern Democrat Stephen A. Douglas, and Constitutional Unionist John Bell, was a brief affair by 21st-century standards. The campaign began after the party conventions in May and June and ended with the election on November 6th. The candidates did not campaign for themselves—with the tradition-breaking exception of Douglas’s “visits to his mother”—so it was up to the candidates’ supporters to bring their man to the voters’ attention and whip up the enthusiasm that would produce success at the polls. Lincoln’s supporters got to work, producing biographies of the candidate; political cartoons; campaign flags, tokens, and buttons; and songs to be sung at rallies.

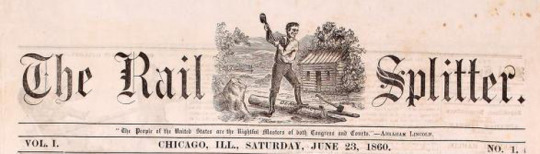

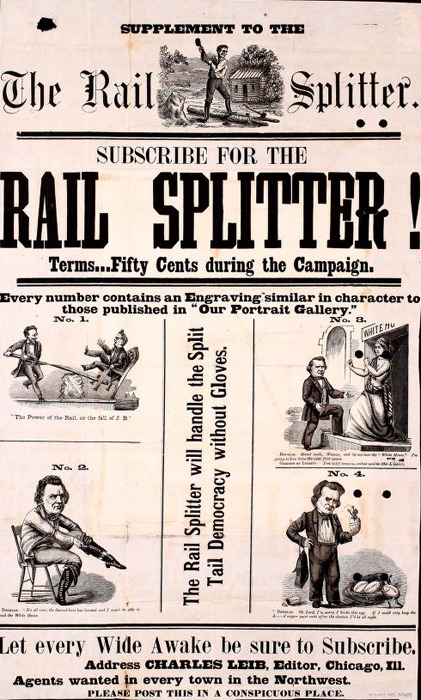

And they published campaign newspapers—entirely partisan weeklies that supported the Republican Party and lauded its candidate while criticizing and sometimes demeaning the opposition. The Chicago Rail Splitter is a prime example. The paper made its debut on June 23, 1860, and published 18 regular issues, ending on October 27th.

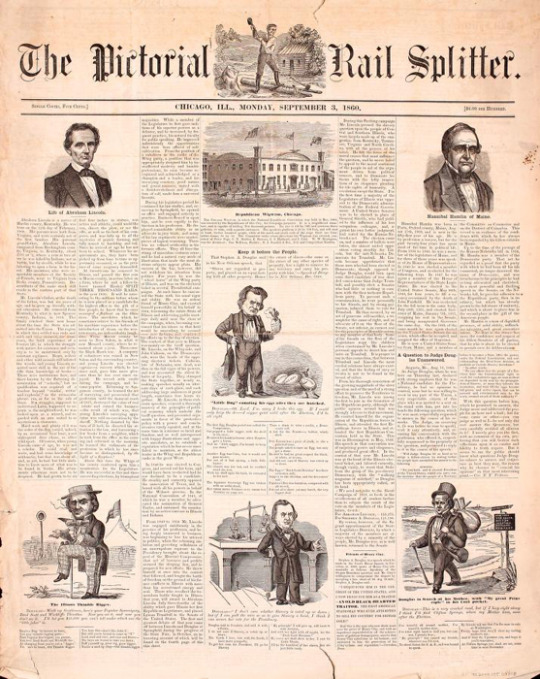

In addition, it published a special “pictorial” issue on September 30th that featured a series of cartoons lampooning Democrat Stephen Douglas.

The paper’s editor, Charles Leib, was a man with a somewhat shifting (or shifty) political history, but with his appointment as editor of the Rail Splitter, he became a vociferous Republican partisan. An advertisement for the paper promised to “handle the Split Tail Democracy without Gloves.”

And in his introduction to the first issue, Leib promised to “earnestly advocate the principles of Republicanism because they are founded in right” and to “expose the double-dealing…and…villainous schemes” of the Democrats. “There will,” he proclaimed, “be a great deal of crimination and recrimination.” And he concluded somewhat pugnaciously, “if we should incur the displeasure of any of the Democracy [Democratic Party] for telling the truth, and they should feel aggrieved, they can call at our office, at 66 Randolph Street, up stairs, where we will be most happy to give them any satisfaction they may desire. We will not, however, take back any statement we make, of the truth of which we are satisfied.”

The Republicans of Cincinnati also published a Rail Splitter, independent of the Chicago paper. The Cincinnati paper published every Wednesday from August 1st through October 17th, with a final issue on October 27th, under the editorship of J.H Jordan and J.B. McKeehan.

The Cincinnati Rail Splitter advertised itself as “devoted to facts, arguments, and incidents, which will be of great service to the Republican cause throughout the United States” in order to “take the ‘starch’ out of the ‘Little Giant’ and other Democratic ‘Dough Faces,’ and show them up in their true colors.” In fulfilling that goal, the paper would “stir up the young men of the country to activity and vigilance, and light up the watch-fires of ‘LINCOLN and HAMLIN’ on every hill.”

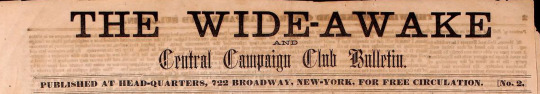

Unlike the Chicago and Cincinnati campaign papers, each of which cost 50 cents per issue, the Wide-Awake and Central Campaign Club Bulletin was distributed in New York City for free.

New York City was home to numerous Wide-Awake clubs—groups of young men who supported Lincoln and the Republicans with well-organized torch-light parades featuring marching units dressed in helmets or caps and shiny caped uniforms made of enameled cloth. Parades usually ended with nighttime rallies. The clubs also sponsored indoor meetings with well-known speakers. The October 5th issue of the Wide-Awake and Central Campaign Club Bulletin details a meeting held at the Cooper Union where Thaddeus Stevens was the primary speaker.

It also includes advertisements for Wide-Awake supplies like torches, “oils for torch lights and signal lanterns,” and printed membership certificates.

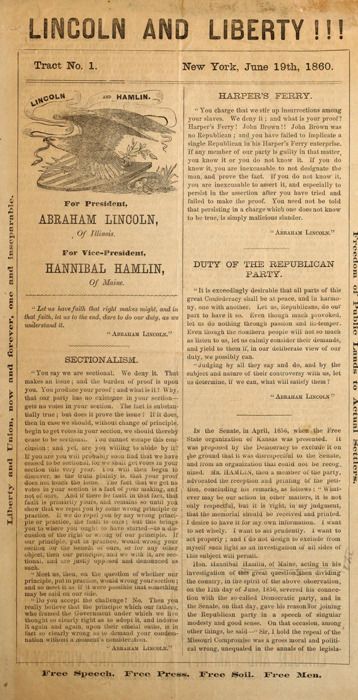

While the Wide-Awake Clubs were new organizations formed for the 1860 election, the Young Men’s Republican Union of the City of New York was a more experienced group, having been formed in 1856 to support Republican candidate John C. Frémont. The Union sponsored a reading room and met regularly to hear speakers—it was, in fact, the sponsor for Abraham Lincoln’s speech at Cooper Union on February 27, 1860. The Union published a series of tracts or campaign papers between June 19th and October 2nd titled “Lincoln and Liberty!!!” The papers published excerpts from speeches and newspapers and reported on the campaign’s progress across the North.

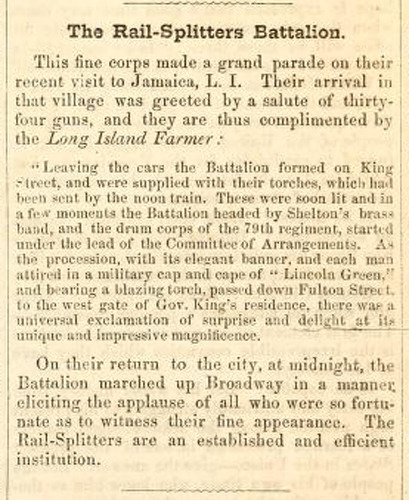

The Union was, however, a self-proclaimed young men’s movement and formed its own Wide-Awake unit, the Rail-Splitter’s Battalion.

In Tract No. 2, the Union proclaimed that “Young Men are rallying, in great numbers and with unbounded enthusiasm, to the support of ‘Honest Old Abe’…the Young Men have every confidence in the Illinois rail-splitter, knowing that one competent to raise himself from the humblest and most obscure, to the most elevated and influential position in society, is fit to be entrusted with the reins of government, and will not hold them amiss. Lincoln is, emphatically, the choice of the Young Men, and their earnest enthusiasm will contribute largely to his inevitable success.”

Whether Lincoln’s success in 1860 was inevitable was an open question, of course, but the Republican campaign papers did their best to make it so.

#abraham lincoln#abrahamlincoln#1860 election#campaign newspapers#newspapers#chicago rail splitter#cincinnati rail splitter#young men's republican union#wide-awakes

13 notes

·

View notes

Link

Can foreigners Invest in Real Estate in Rwanda?This is one of the questions that we get asked the most. The simple answer is yes! You can buy property in Rwanda even if you do not have Rwandan citizenship. And, even better, it is very simple and fast....

0 notes

Text

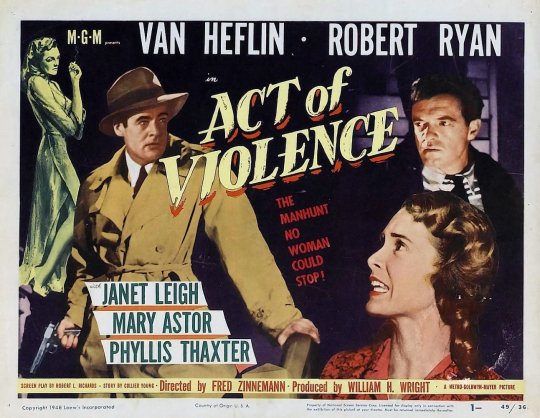

Act of Violence

Such a vast difference in funds, and pictures a male with a limp in the midst of memorial day. That’s actually the first time war was mentioned within the film. Catching sight of the man with the limp, he brought upon a hidden mystery into the mix of conflicting narratives.

As the shifty man calls, the husband had recently gone out to fish. Barreling music as the man signs everything he needs to. Hand delivering evidence to the right perceptive people. Doing everything himself shows that he has a one tract mind and nothing else to stand by his side. Trying to go at everything alone he is left with a metal gun.

The fisherman ended up finding out about the man attempting to kill him, and tried to run. Skeptical as Frank may be it gives question to what he did to the poor man. Or around him at all. Shocking his wife, it now gives a bit of tension to the atmosphere. Hearing the light trickle of water in the background gives the space eerie background noise. From the apparent description Frank was a patsy blamed for things he may not have done. Or just used as a punching bag.

Another reference to PTSD is when Frank puts down her idea for the police. Telling her it was just too much metal strain. Although with what we know now, if these problems aren’t taken care of they just get worse. Joe as we know as the supposed villain is has a different story. In the right of mind he was able to tell her what he strove through to get to this point. In one aspect you could say Frank was taking pity in other light he could be lying and running.

While talking to his wife in California he tries gaining height finding himself more important than the opposing opinion. Frank had been broken, and the others attempted to leave. Realizing that Frank had been the real villain in a taxing circumstances causes others to act. As impending death grows closer, he tries to get a drink at a closed bar. Where the bartender drinks the drink he left alone. Attempting to sell his own company to rid himself of his only mistake lead him to another chain of heavy dealings. A supposed lawyer is to help him get out of a bind Frank twisted himself into.

On top of it all he started to question himself and everything he has lived for. Did he create a nice life for himself or to cover up the guilt he feels from the war. Nevertheless it drives him to stand in front of a train with a blaring headlight looking suspiciously like a clock. As it gets closer and closer you can see his breath become greater and greater to the point where he ducks out of the way. Confirming his previous worry to only save himself.

As a result he relives the memory within a tunnel, and it seems that every memory is an echo. Shouting at random times, as the watcher gets bits and pieces of the situation. Hearing the distinguishing voice of everyone from the monologue in his head. Finally giving in to the delusion he lead himself to believe until he takes his future into his own hands.

Taking the bullet for another crime he had drunkenly set up cleansed his subconscious and helped the man that wanted to kill him in the first place. Essentially it was the only way to resolve the resounding issue’s between so many people in question. Joe was relived to see him die by someone else’s hand because he wont have to shoulder the burden of guilt or revenge any longer.

1 note

·

View note

Quote

3. EUROPE AFTER THE ANGLO-FRENCH WAR A subtle change now began to affect the whole mental climate of the planet. This is remarkable, since, viewed for instance from America or China, this war was, after all, but a petty disturbance, scarcely more than a brawl between quarrelsome statelets, an episode in the decline of a senile civilization. Expressed in dollars, the damage was not impressive to the wealthy West and the potentially wealthy East. The British Empire, indeed, that unique banyan tree of peoples, was henceforward less effective in world diplomacy; but since the bond that held it together was by now wholly a bond of sentiment, the Empire was not disintegrated by the misfortune of its parent trunk. Indeed, a common fear of American economic imperialism was already helping the colonies to remain loyal. Yet this petty brawl was in fact an irreparable and far reaching disaster. For in spite of those differences of temperament which had forced the English and French into conflict, they had co-operated, though often unwittingly, in tempering and clarifying the mentality of Europe. Though their faults played a great part in wrecking Western civilization, the virtues from which these vices sprang were needed for the salvation of a world prone to uncritical romance. In spite of the inveterate blindness and meanness of France in international policy, and the even more disastrous timidity of England, their influence on culture had been salutary, and was at this moment sorely needed. For, poles asunder in tastes and ideals, these two peoples were yet alike in being on the whole more sceptical, and in their finest individuals more capable of dispassionate yet creative intelligence, than any other Western people. This very character produced their distinctive faults, namely, in the English a caution that amounted often to moral cowardice, and in the French a certain myopic complacency and cunning, which masqueraded as realism. Within each nation there was, of course, great variety. English minds were of many types. But most were to some extent distinctively English; and hence the special character of England's influence in the world. Relatively detached, sceptical, cautious, practical, more tolerant than others, because more complacent and less prone to fervour, the typical Englishman was capable both of generosity and of spite, both of heroism and of timorous or cynical abandonment of ends proclaimed as vital to the race. French and English alike might sin against humanity, but in different manners. The French sinned blindly, through a strange inability to regard France dispassionately. The English sinned through faint-heartedness, and with open eyes. Among all nations they excelled in the union of common sense and vision. But also among all nations they were most ready to betray their visions in the name of common sense. Hence their reputation for perfidy. Differences of national character and patriotic sentiment were not the most fundamental distinctions between men at this time. Although in each nation a common tradition or cultural environment imposed a certain uniformity on all its members, yet in each nation every mental type was present, though in different proportions. The most significant of all cultural differences between men, namely, the difference between the tribalists and the cosmopolitans, traversed the national boundaries. For throughout the world something like a new, cosmopolitan "nation" with a new all-embracing patriotism was beginning to appear. In every land there was by now a salting of awakened minds who, whatever their temperament and politics and formal faith, were at one in respect of their allegiance to humanity as a race or as an adventuring spirit. Unfortunately this new loyalty was still entangled with old prejudices. In some minds the defence of the human spirit was sincerely identified with the defence of a particular nation, conceived as the home of all enlightenment. In others, social injustice kindled a militant proletarian loyalty, which, though at heart cosmopolitan, infected alike its champions and its enemies with sectarian passions. Another sentiment, less definite and conscious than cosmopolitanism, also played some part in the minds of men, namely loyalty toward the dispassionate intelligence, and perplexed admiration of the world which it was beginning to reveal, a world august, immense, subtle, in which, seemingly, man was doomed to play a part minute but tragic. In many races there had, no doubt, long existed some fidelity toward the dispassionate intelligence. But it was England and France that excelled in this respect. On the other hand, even in these two nations there was much that was opposed to this allegiance. These, like all peoples of the age, were liable to bouts of insane emotionalism. Indeed the French mind, in general so clear sighted, so realistic, so contemptuous of ambiguity and mist, so detached in all its final valuations, was yet so obsessed with the idea "France" as to be wholly incapable of generosity in international affairs. But it was France, with England, that had chiefly inspired the intellectual integrity which was the rarest and brightest thread of Western culture, not only within the territories of these two nations, but throughout Europe and America. In the seventeenth and eighteenth Christian centuries, the French and English had conceived, more clearly than other peoples, an interest in the objective world for its own sake, had founded physical science, and had fashioned out of scepticism the most brilliantly constructive of mental instruments. At a later stage it was largely the French and English who, by means of this instrument, had revealed man and the physical universe in something like their true proportions; and it was chiefly the elect of these two peoples that had been able to exult in this bracing discovery. With the eclipse of France and England this great tradition of dispassionate cognizance began to wane. Europe was now led by Germany. And the Germans, in spite of their practical genius, their scholarly contributions to history, their brilliant science and austere philosophy, were at heart romantic. This inclination was both their strength and their weakness. Thereby they had been inspired to their finest art and their most profound metaphysical speculation. But thereby they were also often rendered un-self-critical and pompous. More eager than Western minds to solve the mystery of existence, less sceptical of the power of human reason, and therefore more inclined to ignore or argue away recalcitrant facts, the Germans were courageous systematizers. In this direction they had achieved greatly. Without them, European thought would have been chaotic. But their passion for order and for a systematic reality behind the disorderly appearances, rendered their reasoning all too often biased. Upon shifty foundations they balanced ingenious ladders to reach the stars. Thus, without constant ribald criticism from across the Rhine and the North Sea, the Teutonic soul could not achieve full self-expression. A vague uneasiness about its own sentimentalism and lack of detachment did indeed persuade this great people to assert its virility now and again by ludicrous acts of brutality, and to compensate for its dream life by ceaseless hard-driven and brilliantly successful commerce; but what was needed was a far more radical self-criticism. Beyond Germany, Russia. Here was a people whose genius needed, even more than that of the Germans, discipline under the critical intelligence. Since the Bolshevic revolution, there had risen in the scattered towns of this immense tract of corn and forest, and still more in the metropolis, an original mode of art and thought, in which were blended a passion of iconoclasm, a vivid sensuousness, and yet also a very remarkable and essentially mystical or intuitive power of detachment from all private cravings. America and Western Europe were interested first in the individual human life, and only secondarily in the social whole. For these peoples, loyalty involved a reluctant self-sacrifice, and the ideal was ever a person, excelling in prowess of various kinds. Society was but the necessary matrix of this jewel. But the Russians, whether by an innate gift, or through the influence of agelong political tyranny, religious devotion, and a truly social revolution, were prone to self-contemptuous interest in groups, prone, indeed, to a spontaneous worship of whatever was conceived as loftier than the individual man, whether society, or God, or the blind forces of nature. Western Europe could reach by way of the intellect a precise conception of man's littleness and irrelevance when regarded as an alien among the stars; could even glimpse from this standpoint the cosmic theme in which all human striving is but one contributory factor. But the Russian mind, whether orthodox or Tolstoyan or fanatically materialist, could attain much the same conviction intuitively, by direct perception, instead of after an arduous intellectual pilgrimage; and, reaching it, could rejoice in it. But because of this independence of intellect, the experience was confused, erratic, frequently misinterpreted; and its effect on conduct was rather explosive than directive. Great indeed was the need that the West and East of Europe should strengthen and temper one another. After the Bolshevic revolution a new element appeared in Russian culture, and one which had not been known before in any modern state. The old regime was displaced by a real proletarian government, which, though an oligarchy, and sometimes bloody and fanatical, abolished the old tyranny of class, and encouraged the humblest citizen to be proud of his partnership in the great community. Still more important, the native Russian disposition not to take material possessions very seriously co-operated with the political revolution, and brought about such a freedom from the snobbery of wealth as was quite foreign to the West. Attention which elsewhere was absorbed in the massing or display of money was in Russia largely devoted either to spontaneous instinctive enjoyments or to cultural activity. In fact it was among the Russian townsfolk, less cramped by tradition than other city-dwellers, that the spirit of the First Men was beginning to achieve a fresh and sincere readjustment to the facts of its changing world. And from the townsfolk something of the new way of life was spreading even to the peasants; while in the depths of Asia a hardy and ever-growing population looked increasingly to Russia, not only for machinery, but for ideas. There were times when it seemed that Russia might transform the almost universal autumn of the race into a new spring. After the Bolshevic revolution the New Russia had been boycotted by the West, and had therefore passed through a stage of self-conscious extravagance. Communism and naïve materialism became the dogmas of a new crusading atheist church. All criticism was suppressed, even more rigorously than was the opposite criticism in other countries; and Russians were taught to think of themselves as saviours of mankind. Later, however, as economic isolation began to hamper the Bolshevic state, the new culture was mellowed and broadened. Bit by bit, economic intercourse with the West was restored, and with it cultural intercourse increased. The intuitive mystical detachment of Russia began to define itself, and so consolidate itself, in terms of the intellectual detachment of the best thought of the West. Iconoclasm was harnessed. The life of the senses and of impulse was tempered by a new critical movement. Fanatical materialism, whose fire had been derived from a misinterpreted, but intense, mystical intuition of dispassionate Reality, began to assimilate itself to the far more rational stoicism which was the rare flower of the West. At the same time, through intercourse with peasant culture and with the peoples of Asia, the new Russia began to grasp in one unifying act of apprehension both the grave disillusion of France and England and the ecstasy of the East. The harmonizing of these two moods was now the chief spiritual need of mankind. Failure to integrate them into an all-dominant sentiment could not but lead to racial insanity. And so in due course it befell. Meanwhile this task of integration was coming to seem more and more urgent to the best minds in Russia, and might have been finally accomplished had they been longer illumined by the cold light of the West. But this was not to be. The intellectual confidence of France and England, already shaken through progressive economic eclipse at the hands of America and Germany, was now undermined. For many decades England had watched these newcomers capture her markets. The loss had smothered her with a swarm of domestic problems, such as could never be solved save by drastic surgery; and this was a course which demanded more courage and energy than was possible to a people without hope. Then came the war with France, and harrowing disintegration. No delirium seized her, such as occurred in France; yet her whole mentality was changed, and her sobering influence in Europe was lessened. As for France, her cultural life was now grievously reduced. It might, indeed, have recovered from the final blow, had it not already been slowly poisoned by gluttonous nationalism. For love of France was the undoing of the French. They prized the truly admirable spirit of France so extravagantly, that they regarded all other nations as barbarians. Thus it befell that in Russia the doctrines of communism and materialism, products of German systematists, survived uncriticized. On the other hand, the practice of communism was gradually undermined. For the Russian state came increasingly under the influence of Western, and especially American, finance. The materialism of the official creed also became a farce, for it was foreign to the Russian mind. Thus between practice and theory there was, in both respects, a profound inconsistency. What was once a vital and promising culture became insincere.

0 notes

Text

I Am The Rock...

I was raised in a Republican, Conservative, Christian household. Three things I no longer identify with and haven’t in decades. I could say, like some do, that times were different then and they were. There is no doubt about that. Republicans in office approved the creation of The EPA, and now they wish to destroy it, and the planet along with it. Republicans approved the creation of OSHA, but now could care less about the safety and well being of workers, and would gladly send the jobs overseas to get a higher percentage. They spoke of responsible spending and self reliance, but later gave us Reaganomics, Trickle Down Economics, and Supply Side Economics, all slanted theories based on the same skewed me-first policies. Where did the Republicans go?

Conservatives were always a bit shifty. Nervous Nellies that were always worried about something that had nothing to do with them. They would meet and eat and talk and balk and the rest of the community would giggle at them for being such goofs. And look at them now. All those outlandish televangelists, the nutty politicians on the fringe of reality, and the tracts passed out like heroin to the addicted, along with an entire movement unsatisfied with their own lives and willing to inflict their discontent onto others rather than solve the issues at hand, eventually turned a jittery group of grumblers into a very vocal mass of whiners and complainers who simply refuse to mind their own business while attacking anyone who minds theirs. Many that once tended to stick together and keep the circle closed are now nothing more than a selfish infection upon society, with a whole section wishing nothing but destruction upon the world of those not like them. So where did The Conservatives go?

The Christians. Yes, them... All 39,000+ denominations of them. That says a lot right there. That so many denominations are needed to satisfy the interpretation required by it’s believers, to JUSTIFY the beliefs of it’s followers, to cherry pick the scriptures for the sake of how the denomination might tweak the original source to fit it’s needs, thus convincing it’s followers that it is the one true version and NOT the others who might be seen as anything from “the confused” to being unclean heretics. The church I attended until eighteen certainly wasn’t like that, well, not until I was about sixteen. My church spoke of committing to a decent life and spreading good news to others, of gathering together to celebrate what is good, and to respect ourselves and others. It taught us not to judge but to accept, not just tolerate people who were different or who had different beliefs. Why? Because they said all were children of God. Well, we certainly don’t hear that message much now do we? We are bombarded by “Christians” who do nothing BUT judge, who refuse to tolerate let alone accept ANYTHING not of the teachings they are absorbing by whatever blasphemous pricks they allow to poison their minds, thus doing the exact opposite of the savior they supposedly exalt. So I ask, where did all the Christians go?

The Republicans, the Conservatives, the Christians, where DID they go? They DIED. Let’s face it, each of them are movements. Humongous movements but still just movements, and they change over the years, decades, even centuries. The original message changes and in turn the motivating factors are affected, but as with all movements, they always need to grow in numbers and strength, lest they fade away and be forgotten. And as such, the movement may stray from it’s creators origins, and morph into something that we would hope is something good and wonderful, but time and time again, takes another path towards something dark and inclusive, that lashes out at those it should accept rather than persecute. We’ve seen it before and quite literally should not be so surprised at what we are seeing now. From The Crusades to The Inquisition to the many translations of The Bible to the vicious message of The WBC, we see two things that shape many Christians, and their Conservative members, which of course includes Republicans, all connected at the base; the inability to be independent, which is looked upon as being without God in many denominations, thus sinful; and forced shame, the key to how some denominations control their flock. To go against the grain is an abomination against God and the congregation and shall be judged and punished with isolation from God and eternal damnation. How awful!

It’s all in selling the fear, and they all bought it. Fifty years ago they knew it and there were those who ate it up then just as now, but they didn’t have the technological means then to spread it, or receive frightening updates every day. There was an effort one had to put in to find information back then and to find whatever one wanted. One had to go to the library, and talk to people face to face, and make phone calls and go to meetings, and DRIVE. That is all gone now. What I want is SECONDS away and is there at the press of a few buttons. With little effort I can find a group that suits me and they can find me the same way. Technology killed The Republicans, The Conservatives, and The Christians. While humans have taken advantage of humans since the beginning, they now have the ultimate tool. The first human to use a rock to smash something not only learned to make something practical from it’s use, but also how to destroy and kill. And nothing has changed.

That’s where they all went, and why people must now make a true effort like before, to return to, or create anew, the basic good without the convenient yet toxic additives the fear sellers have to offer...

0 notes

Text

ok but also consider the intimidation tactics of this duo. tell me u wouldn’t absolute shit ur pants. first of all on the front lines u’ve got h’aanit, this big beefy woman with a bow and arrow, an axe, and a goddamn snow leopard. she looks like she could break your arm and your neck whether standing in front of u or 50ft away. and then. AND THEN

while whoever it is is occupied with h’aanit. NO ONE is going to notice shifty little therion. you’re staring the goddess of death in the face u aren’t going to notice ur wallet disappearing, especially not from mr master thief therion over here. but if it’s something more than just a robbery tactic? like if some dick is like, “yeah i’ll take you on” to h’aanit? suddenly he’s got a dagger at his throat. h’aanit hasn’t even moved. she’s just :) and therion is equally as smug with his whole “you sure you wanna try that, buddy?” and then they’d just disappear.

not to mention they would be UNTRACEABLE. they’re the ultimate stealth duo. a thief used to hiding in the shadows and blending in and avoiding been seen and plenty used to outrunning guards who outnumber him PLUS a huntress skilled in tracking, using nature to her advantage, covering her own tracts, and communicating w animals on top of all the other cool shit h’aanit is?? u cannot tell me anyone could find them if they didn’t want to be found. like. bro. i bet they have their own little hand signals too.

just therion & h’aanit man. wow.

hear me out: therion and h'aanit are literally best friends. they don't talk much, perferring to spend time together in companionable silence, but when they do talk,, oH BOY does it get deep. therion trauma dumps a bit, h'aanit finally talks about her own issues (being orphaned, frustrations with z'aanta, etc), and they let each other feel deeply. they also gossip, probably a bit too much. h'aanit mostly listens, but contributes her two cents occasionally. they love to sit in taverns together whenever they go new places, and try to guess how much money people have on them. h'aanit nearly always makes therion return it once they've found out if they were right. therion doesn't complain too much. they first bonded over linde, since therion is just mildly obsessed with cats. he was always petting her, brushing her, and giving her treats. h'aanit quickly found out he loved apples, and, with ophilia's help, started making apple treats for him. and how could therion resist?

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 Simple Wildfire Survival Tips

Wildfires are quick moving and erratic. You should always be aware of wildfire survival tips. In the current years, rapidly spreading fires have turned into a genuine risk to ranges that were once thought not inclined. You can see the smoke from miles away, yet your first piece of information that there’s a woodland fire close-by is falling powder. Ideally, you will never be that close, however, in the event that you are, a shifty activity might be required.

Here are 10 simple wildfire survival tips:

Leave the region. Try not to stick around to perceive how things create. Fierce blazes are so capable, erratic, and dangerous, that even very much prepared and prepared proficient fire contenders to bite the dust when they wind up plainly caught by an onrushing burst that invades their position.

Keep up situational mindfulness. Know about what’s happening around you in all circumstances. Basic yet vital.

Pick downhill courses, not tough courses if conceivable. Fire moves speedier tough because of updrafts.

Recognize escape courses/safe zones where you could take shield if a fire came thundering through the range. Safe zones incorporate waterways, lakes (get in the water), or vast level spots out in the open far from an ignitable material. So the most secure zones are those that are downhill of the fire.

Spare yourselves! On the off chance that you are caught in a fire, get out as quick as possible. Try not to attempt to spare any of your rigging. Apparatus is replaceable, lives are most certainly not.

Remain out of gulches. Search for an escape course that leads downhill, however, don’t take after gullies, chutes or draws, as these go about as smokestacks that channel lethal warmth up the slope toward you.

Get low. In the event that the blazes are upon you, look for low ground — in a dump or the indent in a woodland street that will permit the super heated convective current to pass overhead. The lower you are the better your odds may be.

Alternative respirator. Inhale inside your dress alongside your body to secure your respiratory tract so you don’t breathe in hot gasses.

On the off chance that you can discover a territory that has officially copied over, leaving no remaining fuel to reignite, that may be a sheltered place. Be that as it may, the surrounding temperature of the signed earth, rocks and timber will feel like a broiler. Observe overhead to maintain a strategic distance from tangles and standing dead trees that may fall on you.

Emergency fire protects: if all else fails or when escape is no longer an alternative, firefighters utilize a fire shield. It’s an exceedingly versatile arch formed thwart covering to stow away under as the fire ignores. These havens claim to reflect 95% of brilliant warmth. They’re genuinely conservative and lightweight and cost $300-$400. In any case, when a mass of flame is thundering toward you at 70 miles for each hour, seeming like Hell’s cargo prepare, and live ashes are pouring down like blazing hailstones, 400 bucks won’t appear like a considerable measure. We prescribe this New Generation Fire Shelter with Case, $376.

0 notes

Text

Article Dod Diapers (3)

Easy Resolution Disposable Diapers For Canines However no more worries, we have performed an extensive research and reviewed prime 10 canine diapers that are readily available in the market to buy straight away in 2017. We embrace each disposable and reusable doggie diapers within the checklist, so in the event you're in search of an eco-pleasant alternative, we've got it lined for you. Without additional ado, let's see what on the listing. If you select human diapers for your canine, you can also make considerable financial savings over the price of disposable doggy diapers. However, you will most likely find that with a view to make them snug for your dog, you have to to cut a hole for the tail. House owners have additionally reported that human diapers fit their canine significantly better if they are placed on backwards - in other words with the adhesive strip fastenings designed for the entrance of child's tummy being fastened at the dog's back. What standards determines whether a certain brand and kind of dog diapers is the best one for you? Let's have a look at among the most necessary pointers you need to consider and consider before buying doggie diapers for Fido. Critically incontinent canine, however, might have a number of diaper changes within the night time. Poop often goes by the tail hole which is large enough; however when it doesn't, there'd be a need for a dog bathtub and diaper change. Typically, canines don't thoughts sporting Easy Solution Disposable Canine Diapers, and that is very important. Second, I saw him demonstrating the best way to put a diaper on a Dog Reveal puppy and I laughed myself silly. Positive, I do know pet diapers exist, but wow, it's so much extra work than baby diapers. The video's captioning explains that he lives in an condominium and the canine has serious urinary issues '” very sobering.

For example, many incontinent canine suffer from circumstances equivalent to a urinary tract infection which ends up in them not having the ability to physically control after they urinate each time, but you will by no means know this truth if you do not get your dog checked and ask for a professional veterinary opinion on your dog's condition and what exactly is causing this incontinence. Simply to let you realize, a few of the links on this web page could also be affiliate hyperlinks, which means that I Love My Chi will earn a small fee from purchases made through these links nevertheless it won't price you anything further. These earnings help to assist the price of working this web site. Thank you a lot for being a I Love My Chi good friend! Wow Jaye, you've a very particular little dog there. Thanks a lot for telling us her story and it's heartening to know that she copes so well - positively a sensible cookie! PS - simply popped over to your profile and noticed the hubs about your miniature schnauzer, so I'm heading back to learn them now! The material is durable yet gentle. These diapers fit comfortably and usually are not shifty. Canine do not mind wearing Vet's Greatest Comfort Fit Disposable Male Wraps at all of their day by day activities. It's important to measure the canine's waistline fastidiously earlier than ordering. It would be safer, though, to buy the bigger measurement while you're not sure because reviewers say these diapers are fairly small compared to most diapers they've used. Earlier than shopping for a package of doggy diapers, be sure you read opinions or examine with other dog proudly owning pals to see how they maintain up. You need to discover a diaper that will soak up effectively, however can also be comfortable. MAle Dog Diapers which are too tight will chafe the skin, and if they don't take in effectively they may trigger diaper rash. For instance, when you're only using a pet diaper for a female dog in heat, then disposable diapers might be a significantly better possibility for everybody. And if your canine suffers from incontinence issues, will probably be much cheaper to use fabric diapers in the long run. Female dog diapers are expected to have super powers. But what they actually do is give pet mother and father peace of mind. And, while that first diaper can be scary to you and your pup, keep in mind that horses in Central Park and even astronauts put on is the time to remain robust and provides your best pal some additional love and keep in mind that even a superb canine can have a nasty day! Like diapers for people, there are lots of differing kinds, styles and sizes of pet diapers for canine. You will want to perform a little research on which doggy diapers will greatest fit your canine's needs. It may additionally take some trial and error to find a model of one of the best dog diapers that may suit your Fido well. Bottom line, diaper carrying shouldn't be trending on social media to be the next massive fashion assertion. Nevertheless, that does not imply your best friend has to wear old style tidy-whities both. Just take a look at Etsy and you will find the newest in doggie diaper couture. There are exotic and playful prints, satins, ruffles, bows, and jewel-studded creations like you've never imagined. Of course, no outfit is full without a top and a company known as Fancy Nancy 's makes colorful tanks to match their particular line of diapers with whimsical names like Orange-Crush, Pink Monkey Kingdom. Want a specialty match for a tiny Chihuahua or big Mastiff, check out Pants for Dogs Their line consists of Leg Protectors for standard and miniature Poodles and Pee Jackets for big canines in full show coats. My private favorite is The Fig Leaf for small canine, possibly as a result of the name is pure genius.

0 notes

Text

This is ~2,000 words of fluff, inspired by late-night brain’s inadvertent mashup of this suggestion by boxofsfic with the ending of this story by sickiepop. (If either of you are seeing this post, hi! I love your work, and I hope you don’t mind what a monster I conceived while reading it…!)

The OCs I made up for the occasion are both around 30; the sick one’s a guy, and the other is nonbinary; they’re housemates; they might be in a QPR, but I don’t think they know that yet either.

I mmmmight write the sequel foreshadowed in the last few lines? Not sure yet; depends on whether I still like what I’ve written by tomorrow. But if you’re reading this and you’d dig that, please let me know!

—

Mr. Bartholomew Fox lay on his classroom’s hard, dusty floor, trying to remember how to pronounce respite. It had been a vocab word this week in some of his tenth graders’ books, but grading their worksheets had not required him to say the word aloud. He could remember that it wasn’t phonetic—it did not rhyme with despite, like its spelling suggested it should. But did one say the word as though it were spelled respeet? Reecepite? Resspit? The remembered voice of a friend from the days of his first smartphone reminded him, You have 3G; he fumbled for his phone, hoping the dictionary app would load this time deecepit the classroom’s shoddy cell service. When he lifted his phone, however, a text from Leverton distracted him.

You ok? At a meeting I forgot about or s/t?

Barty (he was Barty to friends, Mr. F among his less-creative students) hadn’t quite felt like himself all day, though he wasn’t sure what more than that to say about it. His joints and muscles ached, sure; his head throbbed for a bit after every movement, yeah; he’d been shaky and dizzy all day, true—but none of that was weird. He guessed these symptoms must be worse than usual, but no one of them seemed enough that way to justify what an unpleasant day he’d had. Or at least, none had done so until his final class ended, when struck the irresistible urge to lie down on the floor instead of heading home. On the floor, with nothing else to think about, they all seemed urgent. He felt so dizzy it made him hot all over, his upper lip prickling with sweat. If he moved in any way, and whenever he opened his eyes, the feeling grew worse. His left shoulder, right wrist, that mysterious place in his lower back, both knees, the muscles in his neck and thighs and forearms and halfway down his right calf—all traded off shouting for his attention. The throb behind his left eye grew sharper now, more electric, like the start of a migraine (but those usually came on earlier in the day). That side of his nose was clogged. Was he getting a cold? Not unlikely, this early in the school year. Or was it just allergy season.

He’d gone about this far in his musings and then apparently quit thinking at all until something (he could no longer remember what) had made him reach for his phone. Now, having read Leverton’s text, he laid the phone down on his chest and closed his eyes, trying to think how to reply. After he’d typed I’m okay, just and then lay still for a bit pondering how to make must’ve fallen asleep sound less dumb, another text arrived from Leverton:

Just send me an emoji or something so I know you’re not dead? You’re probably just at a meeting and I don’t want to bug you, but, starting to worry a little

I’m okay Barty sent back therefore, deleting the comma and the just. They’d both long-since turned off their phones’ “Read at 4:18 PM” feature—it made Leverton anxious, and incensed Barty on principle. Sending a quick reply took priority, therefore, over explaining himself. The little green progress bar hovered for eons about two thirds of its way across the screen, which it would never have dared at home unless he had tried to send multiple photos. Making sure not to touch the phone’s sides directly, even though he knew that made no difference on this non-dinosaur model, he wrote further, No meeting; fell asleep in classroom. Somehow that one went through at once—so quickly that he’d barely had time to close his eyes and set his head back down before it buzzed again.

Oh my god

Are you ok??? That sounds so unlike you

He didn’t know what to say. The first I’m okay hadn’t felt like a lie, since in that case it was clear he meant okay as opposed to dead. But now neither Yes or No seemed like the right answer. The long pause he elected to respond with instead probably treated Leverton worse than either one:

Are you still in your classroom? Stay there, I’ll come get you

I don’t knw [sic] if I’m comfortable w/ the thought of you driving like this.

On its face Barty found this absurd. Students fell asleep in his class nearly every time he turned on the projector, and that seemed a much greater feat than dozing off while lying alone on the floor. Besides, it hadn’t been real sleep—only stage one or two. If someone had asked whether he was awake he could have honestly said Yes, without startling first. Don’t, he began typing back, but once the initial guilt wore off he thought again about Leverton’s words (Stay there, I’ll come get you). The corners of his eyes grew hot when he pictured them setting out on foot to collect him. Leverton was right, after all—Barty never fell asleep during the day. He deleted the message he’d started and sent instead, Okay.

By the time he heard Leverton’s hand on the doorknob Barty had drifted back into early-stage sleep: close enough to the surface to recognize the sound, but far enough under that it surprised him a little. He’d forgot where he was, his thoughts (now vanished) so vivid they’d seemed realer than the floor under his back. He pulled himself up onto his elbows and his sight went dark blue from the corners inward.

“Hi,” he told Leverton as the latter entered—too quietly, as it turned out, for them to hear over the sound of the closing door. They peered around the room, but it took them a few seconds to spot him; he could tell they were looking for a seated person, rather than one on the floor. Barty cleared his throat and this time said, “Hello.”

“Oh my god—did you fall? Are you alright?”

“No, I’m fine,” Barty insisted, shaking his head, and then, smiling inanely, added, “I meant to do this.”

(Meant to do that was a long-standing meme of theirs, an offshoot from Leverton’s comparisons of Barty to a cat. After a cat does something stupid, it recovers its dignity so quickly you’d think it was trying to look like the stupid thing it did was all part of the plan. Thus whenever either of them made a mistake too large to ignore but too small for a real apology, they’d say to the other some variation on, Meant to do that.)

“You just thought the linoleum seemed like a nice change of pace from the nice couch we have at home,” summarized Leverton, and Barty noticed how they used the word nice twice in a row.

He lowered his head back to the floor, feeling too dizzy and neck-sore to waste his strength on trifles. “It’s vinyl; they just replaced it.”

“What?”

“The floor.”

“Ah. Vinyl. Excuse me.” They sat cross-legged down next to Barty, on the aforesaid vinyl.

“I’m alright,” Barty said again.

“Yeah, but that word doesn’t mean a lot coming from you. Excuse my cold hands,” Leverton warned, and placed the back of their hand to Barty’s forehead and each cheek in turn, brushing some hair out of the way first so it wouldn’t get in his eyes. Barty flinched slightly, having gone from unpleasantly hot to unpleasantly cold in the time since he’d first made contact with the floor. “Feels like you’ve got a fever. Do you think you might be coming down with something?”

“You just said your hands are cold, though,” pointed out Barty.

“Well, yeah,” Leverton conceded with a snarl of laughter—“‘cause compared to a face I figured they would be.”

“Thought you meant ‘cause you’d come from outside.”

“No; I wasn’t cold out there.”

This week had brought their town its first cold snap of the season, but in California an early-fall cold snap parses out to more like absence of heat wave. The last few days it had been cool enough to keep the AC off, but it was still t-shirt weather out from ten to ten. Leverton’s tie dye, sweatpants and flip-flops attested to this—as well as to how quickly they must have hurried to meet him. Though they worked from home, Leverton usually put on jeans to meet the public. And that tie-dye t-shirt, Barty knew, had a small hole in one armpit. It pleased him to remark that he could still keep track of details like this; too bad these examples of lucidity were invisible to Leverton.

“You look pretty sick,” said the latter. “How do you feel?”

Come to think of it, the word lucid itself could also mean translucent. That was about how he felt: diaphanous, vague, barely-there. His mother always said with it instead of lucid; though she’d never said so, he’d deduced the antonym of with it must be out of it.

“Not my best,” Barty admitted.

“But you didn’t faint, or hurt yourself, or anything.”

“No. Worried I might, but figured I’d preempt it.”

“Always thinking ahead,” scoffed Leverton, combing their hand through some more of Barty’s hair. “Your hair’s all sweaty; did you know that?”

“I did not.”

“You don’t usually sweat that bad just from feeling faint, I didn’t think.”

“You’re right.”

“So again I say, You look sick.”

“I’m probably getting sick.”

Leverton sighed through pursed lips, making them billow noisily. “Well, shit, pal, this is a terrible place to be sick.”

“Such language,” mumbled Barty, without conviction. He was so unused to letting swears pass without comment in this room that it would have taken more effort to say nothing. But Leverton, rightly, ignored this comment:

“Can you stand? Maybe I could get you some water—would that help?”

“Yes, and yes. On my desk,” Barty said, pointing without looking up.

“Uhhh… ah! I see it.” Leverton stood up and brought back Barty’s bottle of water. They sat again, uncapped it, and, once Barty had sat back up on his elbows, handed it to him and gripped his shoulder, presumably to help him keep his balance. Barty gulped down several mouthfuls, broke off to catch his breath, and shoved the cold-sweaty bottle back into Leverton’s hand, eager to lie back down. “Ah!—no—wrong way!” squawked Leverton. “Are you sure you can stand.”

“Just need a minute. Can you drag the desk chair over? Seems a pleasanter middle ground than.”

“Oh—good point. Sure.” They rolled it over, apologizing for the squeaky wheel. When he had more energy, among his friends Barty would sneer and hiss at such unpleasant sounds; the chair’s squeak hurt his head now too, of course, but somehow at the moment he found it easier to withstand unpleasant phenomena than resist them.

After a minute, he did indeed pull himself up and slither into the chair. (Leverton evidently knew better than to offer a hand to help him up; such offers would hurt his pride, and possibly also his shoulders.) His hands shook as he gripped the arms of the chair to haul himself up into it; his head spun; he was so weak the exertion hurt his chest and all four limbs. When he subsided to catch his breath his head throbbed raucously. He leant it into his hand—whose support Leverton then seconded with their own hand. Their touch chilled him at first, but he lacked the strength (whether of will or body who knew) to scoot away. He hadn’t realized how much the weight of his head had hurt his wrist until Leverton’s help removed that hurt.

“You’re really not feeling well, are you.”

“Seems that way.”

“Thank god I didn’t let you drive yourself home.”

“Too bad for the kids, they’re all gonna catch it,” Barty muttered, regretfully; “as will you, of course. And I won’t do nearly this good a job of looking after you.”

“I don’t mind. You’ll do your best.”

“Will I?”

“You always seem to. From my limited perspective.”

“I don’t have your patience. Or your empathy.”

Leverton scoffed: “Empathy? Yes you do! You feel other people’s feelings just as well as I do—you’re just shyer about it. You’re just emotionally constipated.”

“Perhaps,” granted Barty. He doubted that first half, but could already feel himself smiling at Leverton’s flatteries, and knew if he tried to argue that they would hold the smile against him as an admission. So he gave his doubts no more explicit form than, “Nice of you to say so.”

“Are you ready to try and walk to the car?”

Barty sighed, sort of phlegmily—almost a hiss. “Might as well be.”

#a shifty tract#(...first time i'm using the writing tag and it feels like a lie; no digestive ills here at all#(just vague fluey stuff and undiagnosed chronic illness. in my headcanon he has heds and pots 'cause that's what i have lmao#(but this premise Just Didn't Work on a character who understands his chronic symptoms' mechanisms as well as i know mine#(and barty--again like me--is the kind of guy who Learns Everything about any label he knows applies to him#(but who dislikes not knowing so much that if the problem has no name he'll pretend it doesn't matter for as long as possible#(sooooo no diagnosis for him. sorry pal)#permasickfic#(trying to avoid the chronic illness tag but figured i should tag for it in SOME capacity as i suspect it squicks some people)

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

MARTIN: Sorry.

ARCHIVIST: Ah, it’s fine. I just… I only need from when you got separated. From when you got lost in the tunnels.

MARTIN: No, I mean… I’m sorry I left you.

ARCHIVIST: …Oh, Martin.

MARTIN: [Tearful] It was an accident. I thought you two were with me! I mean, the worms came at us, and they were so much faster, and then there was the gas, and the running, and I just… I, I thought you were right behind me. But when I turned round you were gone. You were both gone. It was an accident.

ARCHIVIST: I know. It’s fine, Martin. Everybody’s… [sigh] Everyone’s fine… I just need you to tell me what happened next, and then it’s finished.

Didn’t fully internalize until a third listen that Jon records the interviews in MAG 40 while surrounded by worm carcasses??

[ID: A digital drawing of Martin and Jon from The Magnus Archives. They sit on the ground in the tunnels underneath the Institute. Martin is a large white man with reddish hair and round glasses. He has one knee drawn to his chest, and his eyes and one cheek are wet. He’s looking in Jon’s direction, but not at his face; he looks surprised. Jon sits with his back against a brick wall, one leg bent the other stretched in front of him. He’s a thin, brown-skinned, dark-haired man, and his glasses are squarer than Martin’s. There are bloody holes in his shoes and several kinds of bandage all over his face and hands. None match his skin--some are white, others beige, all uncomfortably placed. He wears an oversized cardigan, black with brown and gray stripes, probably borrowed from Martin. Under that, his green t-shirt and gray sweatpants both read “Magnus Institute,” though in neither case can we see all the letters. One of Jon’s hands rests lightly on Martin’s forearm. On the ground in front of Jon sit a tape recorder and a lantern; another lantern sits between him and Martin. There’s a ladder behind them, and three piles of hastily swept-up silver worms on the far right. Jon looks at one of these and frowns. End ID.]

#nonsearchable tma tag#a shifty tract#(guess i can use that for both art and writing. at least until i think of something better.#('shart trag' and 'shifty traces' both seemed A Bit too self-deprecating)#g o d this took forever. fuck worms. fuck bricks. i DIDN'T EVEN HAVE TO DRAW BRICKS elias just says 'basement'#that could just mean 'in the archives (as opposed to his own higher-floor office)' but nooooo gotta do TUNNELS for maximum creepy#because i love making more work for myself :')#honestly tho? main reason i drew this is bc i got excited when i realized the worms' attack would have ruined jon's clothes#wanted to draw him dressed wholly in institute merch except for a cardigan borrowed from martin and his own worm-chewed bloody shoes#ETA 2/3/21 fixed martin's glasses and added image description

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

*Illustrates own fic because I can*

...What? It’s not weird

Blanketless, ratless, different-facial-expressions version under here

Aaaand just in case (god, ever wish you could have two levels of read-more cut?)

#a shifty tract#2...#3...#4...#5...#nonsearchable tma tag#you don't want to know how far i got into drawing this before i remembered the stupid blanket#and after it took me SO LONG to decide on their outfits too God

0 notes