#chicago rail splitter

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

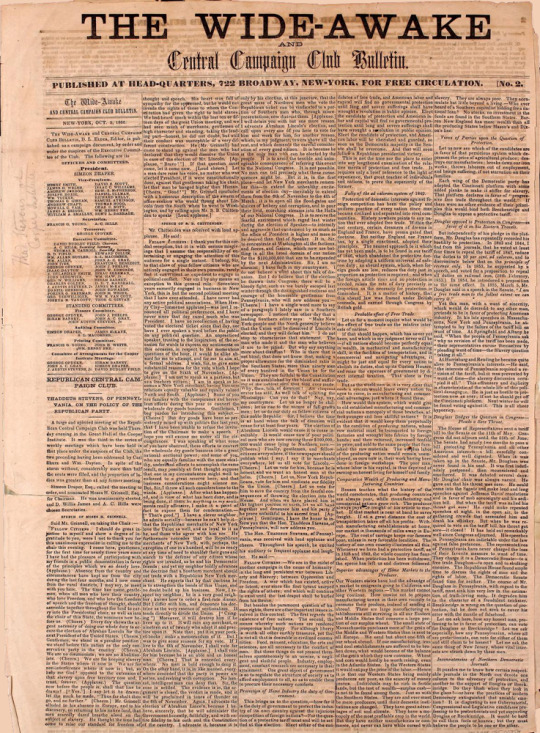

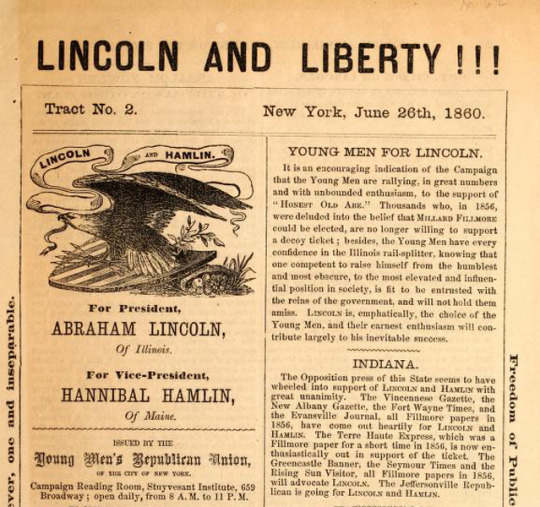

The Partisan Press — Republican Campaign Newspapers in the 1860 Election

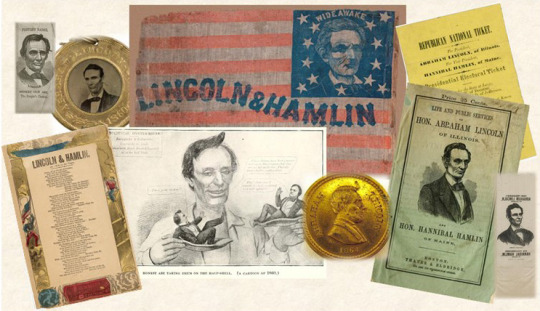

The 1860 presidential campaign, which pitted Republican Abraham Lincoln against Southern Democrat John C. Breckinridge, Northern Democrat Stephen A. Douglas, and Constitutional Unionist John Bell, was a brief affair by 21st-century standards. The campaign began after the party conventions in May and June and ended with the election on November 6th. The candidates did not campaign for themselves—with the tradition-breaking exception of Douglas’s “visits to his mother”—so it was up to the candidates’ supporters to bring their man to the voters’ attention and whip up the enthusiasm that would produce success at the polls. Lincoln’s supporters got to work, producing biographies of the candidate; political cartoons; campaign flags, tokens, and buttons; and songs to be sung at rallies.

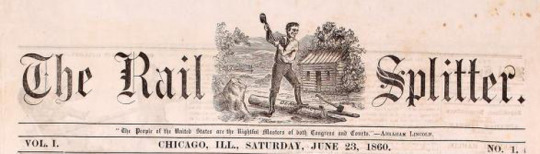

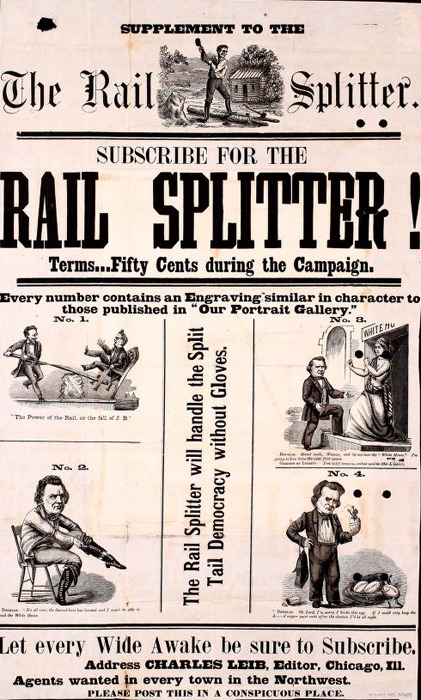

And they published campaign newspapers—entirely partisan weeklies that supported the Republican Party and lauded its candidate while criticizing and sometimes demeaning the opposition. The Chicago Rail Splitter is a prime example. The paper made its debut on June 23, 1860, and published 18 regular issues, ending on October 27th.

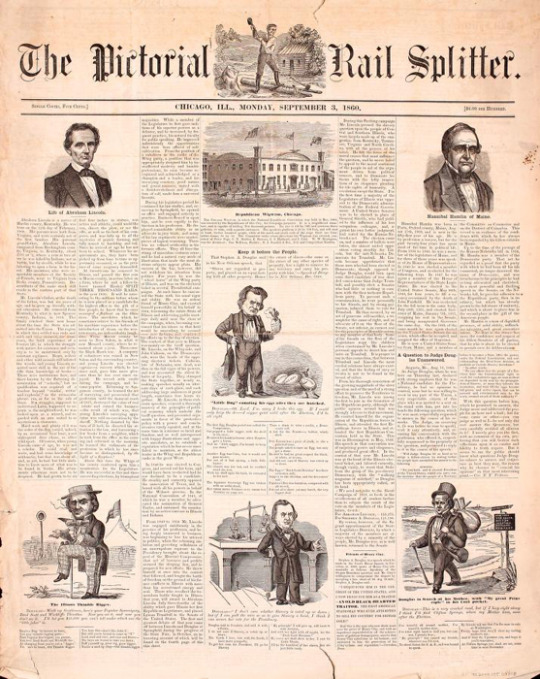

In addition, it published a special “pictorial” issue on September 30th that featured a series of cartoons lampooning Democrat Stephen Douglas.

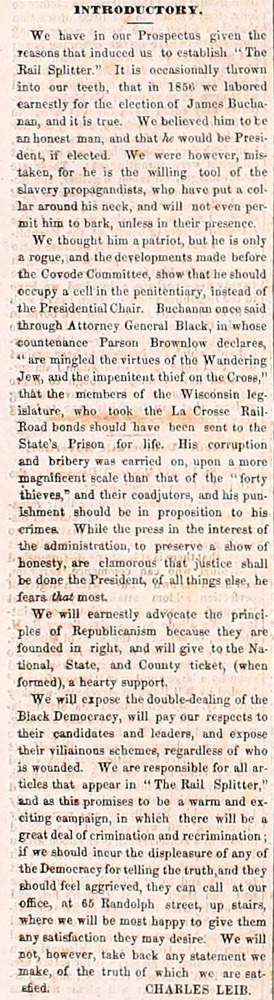

The paper’s editor, Charles Leib, was a man with a somewhat shifting (or shifty) political history, but with his appointment as editor of the Rail Splitter, he became a vociferous Republican partisan. An advertisement for the paper promised to “handle the Split Tail Democracy without Gloves.”

And in his introduction to the first issue, Leib promised to “earnestly advocate the principles of Republicanism because they are founded in right” and to “expose the double-dealing…and…villainous schemes” of the Democrats. “There will,” he proclaimed, “be a great deal of crimination and recrimination.” And he concluded somewhat pugnaciously, “if we should incur the displeasure of any of the Democracy [Democratic Party] for telling the truth, and they should feel aggrieved, they can call at our office, at 66 Randolph Street, up stairs, where we will be most happy to give them any satisfaction they may desire. We will not, however, take back any statement we make, of the truth of which we are satisfied.”

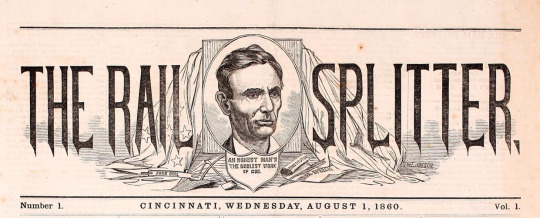

The Republicans of Cincinnati also published a Rail Splitter, independent of the Chicago paper. The Cincinnati paper published every Wednesday from August 1st through October 17th, with a final issue on October 27th, under the editorship of J.H Jordan and J.B. McKeehan.

The Cincinnati Rail Splitter advertised itself as “devoted to facts, arguments, and incidents, which will be of great service to the Republican cause throughout the United States” in order to “take the ‘starch’ out of the ‘Little Giant’ and other Democratic ‘Dough Faces,’ and show them up in their true colors.” In fulfilling that goal, the paper would “stir up the young men of the country to activity and vigilance, and light up the watch-fires of ‘LINCOLN and HAMLIN’ on every hill.”

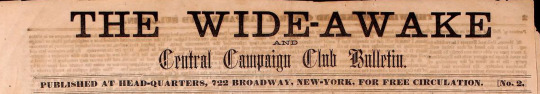

Unlike the Chicago and Cincinnati campaign papers, each of which cost 50 cents per issue, the Wide-Awake and Central Campaign Club Bulletin was distributed in New York City for free.

New York City was home to numerous Wide-Awake clubs—groups of young men who supported Lincoln and the Republicans with well-organized torch-light parades featuring marching units dressed in helmets or caps and shiny caped uniforms made of enameled cloth. Parades usually ended with nighttime rallies. The clubs also sponsored indoor meetings with well-known speakers. The October 5th issue of the Wide-Awake and Central Campaign Club Bulletin details a meeting held at the Cooper Union where Thaddeus Stevens was the primary speaker.

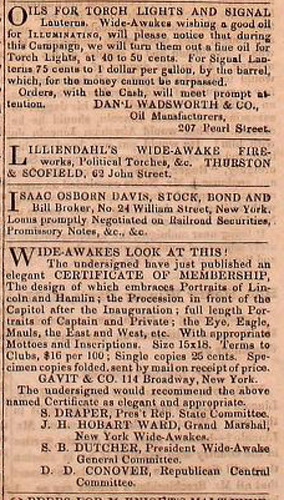

It also includes advertisements for Wide-Awake supplies like torches, “oils for torch lights and signal lanterns,” and printed membership certificates.

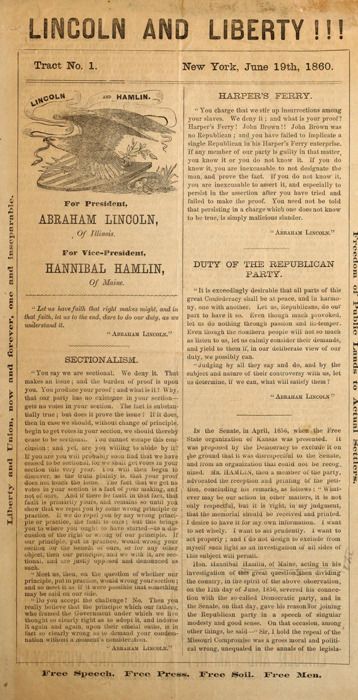

While the Wide-Awake Clubs were new organizations formed for the 1860 election, the Young Men’s Republican Union of the City of New York was a more experienced group, having been formed in 1856 to support Republican candidate John C. Frémont. The Union sponsored a reading room and met regularly to hear speakers—it was, in fact, the sponsor for Abraham Lincoln’s speech at Cooper Union on February 27, 1860. The Union published a series of tracts or campaign papers between June 19th and October 2nd titled “Lincoln and Liberty!!!” The papers published excerpts from speeches and newspapers and reported on the campaign’s progress across the North.

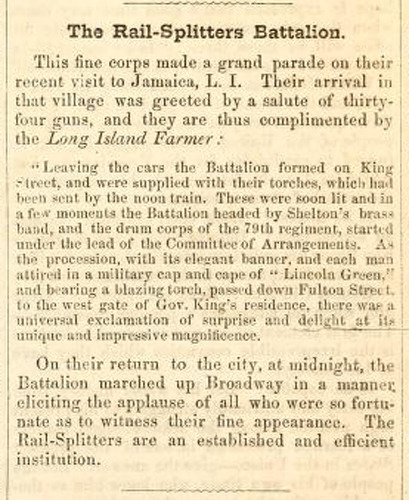

The Union was, however, a self-proclaimed young men’s movement and formed its own Wide-Awake unit, the Rail-Splitter’s Battalion.

In Tract No. 2, the Union proclaimed that “Young Men are rallying, in great numbers and with unbounded enthusiasm, to the support of ‘Honest Old Abe’…the Young Men have every confidence in the Illinois rail-splitter, knowing that one competent to raise himself from the humblest and most obscure, to the most elevated and influential position in society, is fit to be entrusted with the reins of government, and will not hold them amiss. Lincoln is, emphatically, the choice of the Young Men, and their earnest enthusiasm will contribute largely to his inevitable success.”

Whether Lincoln’s success in 1860 was inevitable was an open question, of course, but the Republican campaign papers did their best to make it so.

#abraham lincoln#abrahamlincoln#1860 election#campaign newspapers#newspapers#chicago rail splitter#cincinnati rail splitter#young men's republican union#wide-awakes

13 notes

·

View notes

Quote

You need to read Turner’s essay to understand exactly what George W. Bush is talking about when he talks about “dead or alive” or “tracking people down” or “smoking them out” because the Frontier Thesis is central to American political discourse in some senses. But what’s interesting is that when he gave the talk in 1893 at the Chicago Exposition, half a mile away, Buffalo Bill was performing his Wild West show. So you’ve got the popular culture invention of the Wild West going on at precisely the same time as the academics are trying to write about it … so 1893 is the moment where the Wild West gets invented. If you take President Lincoln, in the early 1860s, he could credibly say he was born in a log cabin, and went from log cabin to White House and was a rail splitter in his youth and actually did these things. Then at the turn of the century, another Harvard alumnus, Theodore Roosevelt …uses the myth the west to support his claims for the presidency. He very consciously writes a four volume book called “The Winning of the West” which is about the least politically correct history of this period you could possibly read. Then you get to Regan who is an actor in Western movies, so he’s one step removed again. And finally you’ve got George W. Bush standing in front of television cameras saying “wanted dead or alive” and remembering television programs he watched in his youth in Texas. So we go from log cabin, to conscious use of the myth by a Harvard man, to someone who acted in b-movies, to someone who watched it on television. Now the myth remains the same, but they all have a different relationship with it. But when you’ve got someone saying words taken from television programs as serious political discourse, it does show the resilience of the western.

Christoper Frayling The American West In Our Time, 13 June 2002 BBC

82 notes

·

View notes

Note

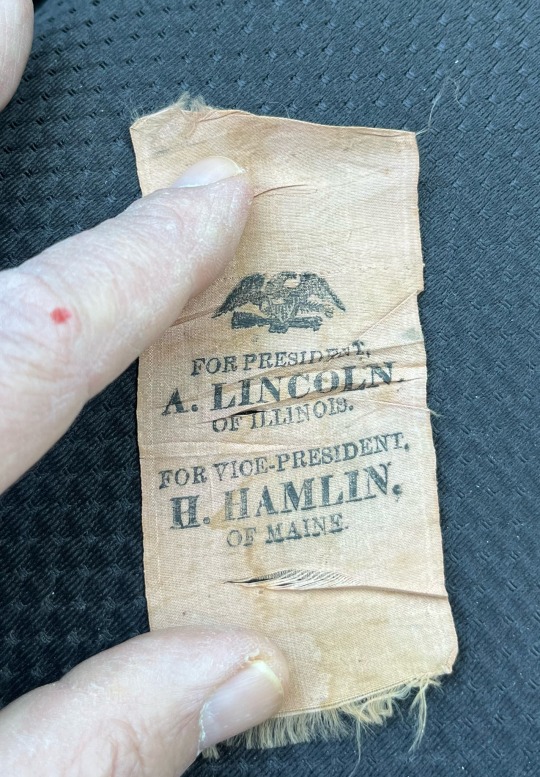

I found this tucked into an antique book. Is there anyway to verify it’s authenticity?

Hi Swedenator!

Because the Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection is an actively collecting collection and must avoid conflict of interest, we cannot appraise or authenticate items. A used or rare item dealer in your area may be able to give you an idea of your item’s value. If you need assistance locating an appraiser, you may contact the American Society of Appraisers at http://www.appraisers.org/find-an-appraiser, phone 800-272-8258, for names of appraisers in your area.

Or you may want to contact Daniel Weinberg at the Abraham Lincoln Book Shop in Chicago http://www.alincolnbookshop.com/, phone 312-944-3085, contact http://alincolnbookshop.com/contact/, email [email protected]. Mr. Weinberg is a dealer and appraiser of Lincoln and Lincoln-related books and other 19th-century materials.

Another alternative is to visit the website of The Rail Splitter (http://railsplitter.com/), an organization of Lincoln collectors and dealers. You can obtain a complimentary informal appraisal by following the instructions on their "Contact Us" page at http://railsplitter.com/?page_id=74 .

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

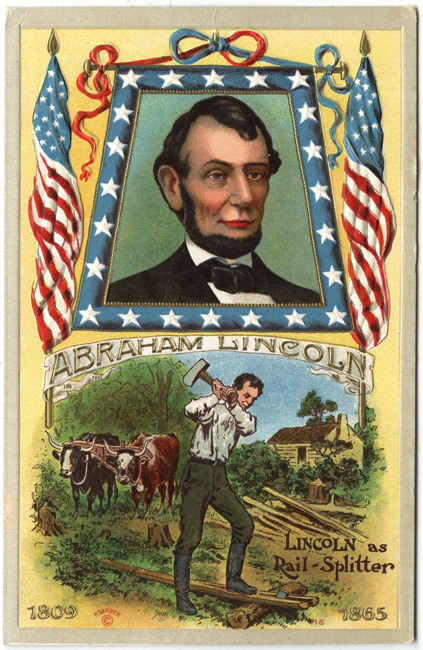

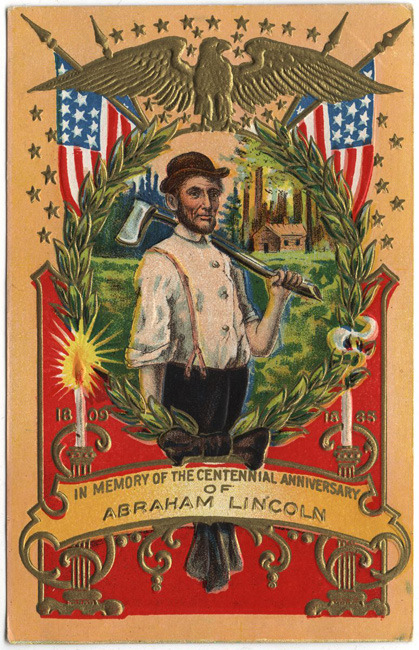

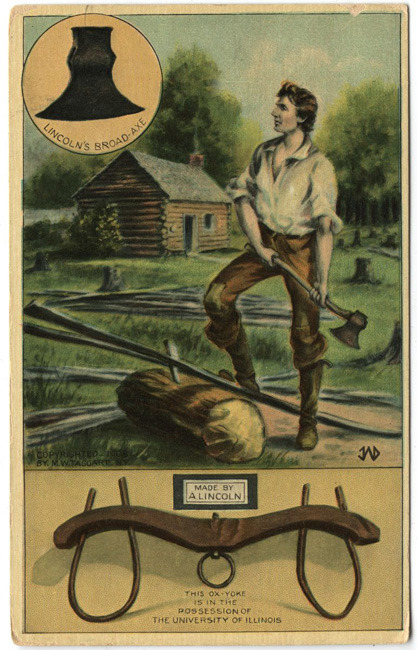

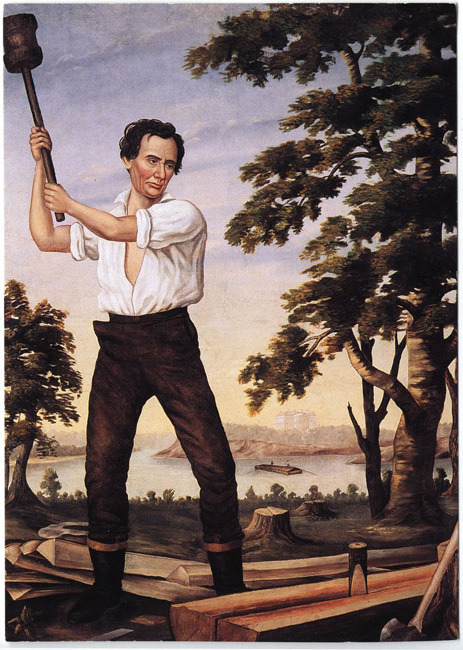

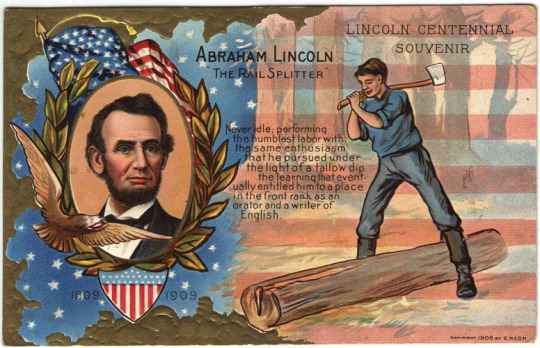

Lincoln the Rail Splitter—The Postcard Image

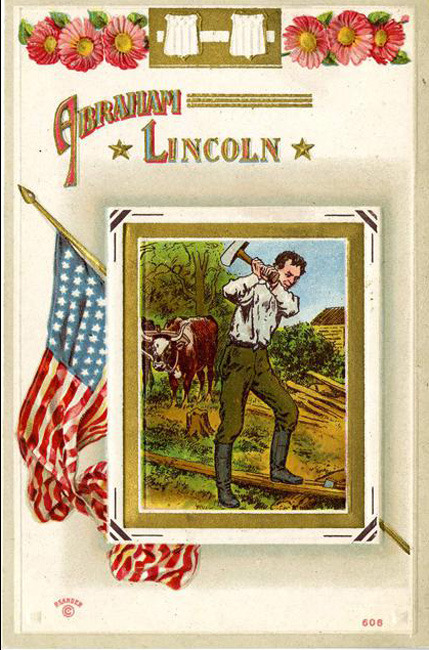

One of the most enduring images of Abraham Lincoln is Lincoln the Rail Splitter—the tall, strong young man wielding his ax or maul splitting fence rails on the Illinois frontier. Lincoln was nicknamed the Rail Splitter by his supporters at the 1860 Illinois state Republican Convention, where they were touting their relatively unknown candidate for the national party’s presidential nomination. Marching though the Decatur Wigwam carrying two fence rails that they claimed were “from a lot of 3,000 made in 1830 by Thos. Hanks and Abe Lincoln,” they cheered Lincoln as “The Rail Candidate.” At the Republican National Convention in Chicago eight days later, the “rail candidate” won the nomination—and in November the presidency—and the rail splitter image became part of Lincoln iconography.

The popularity of Lincoln as rail splitter is reflected in the pictures gracing that very popular 20th-century souvenir item, the picture postcard.

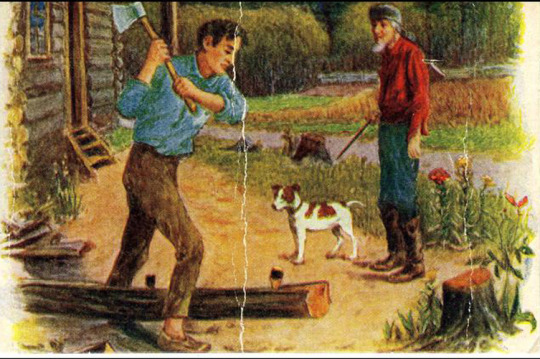

Some postcards focused solely on Lincoln’s rail splitting prowess. This one shows young Lincoln working under the watchful eyes of an older man and a dog. According to printing on the reverse, it was a souvenir card offered by “Boston's Newest Commercial Hotel.”

On this souvenir postcard the Rail Splitter is equipped with both a maul and an ax.

The design on this postcard is embossed for a three-dimensional look.

The same image of young Lincoln at work appears below a portrait of President Lincoln on this postcard.

This embossed postcard was created for the Lincoln centennial in 1909. The Rail Splitter appears much older than the 20-something youth who split fence rails in Illinois, and he sports a post-1860 beard.

“Abraham Lincoln as a Rail Splitter” includes inset images of “Lincoln’s Broadaxe,” with a note on the reverse saying it was then owned by a man in Petersburg, Illinois, and of an Ox-Yoke made by young Lincoln and owned by the University of Illinois.

In 1996, the Chicago Historical Society produced this postcard reproducing a painting from its collection, “The Railsplitter, 1860” by an unknown artist.

This Lincoln centennial souvenir postcard shows the Rail Splitter at work but links that work to young Lincoln’s well-known determination to read and write. The text reads, “Never idle, performing the humblest labor with the same enthusiasm that he pursued under the light of a tallow dip the learning that eventually entitled him to a place in the front rank as orator and a writer of English.”

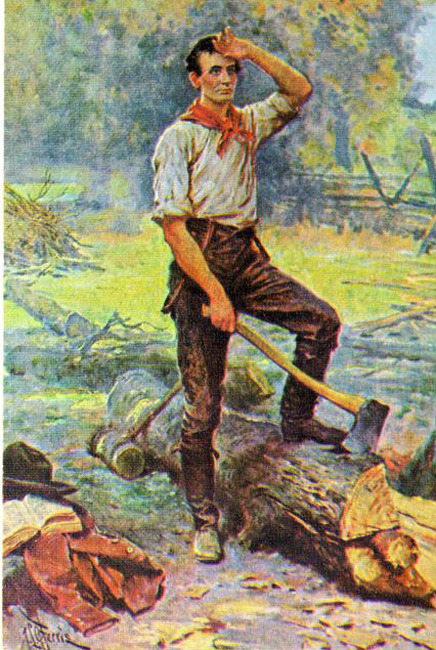

The link between Lincoln’s rail splitting and learning is clear in other postcard images of the young Rail Splitter as well. This postcard, a reproduction of a painting by J.L.G. Ferris, is captioned “The Rail Splitter – 1830 – Lincoln clearing land in Illinois.” Ferris portrays Lincoln with an ax and a maul and also with an open book, which Lincoln will return to at his next rest.

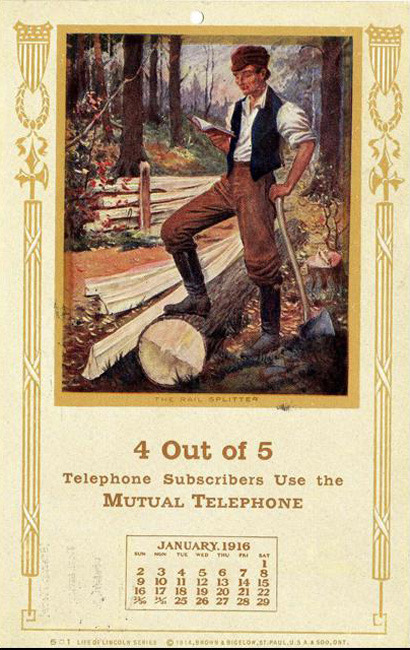

The illustration on this postcard—a 1916 New Year’s greeting card sent to customers of the St. Paul Mutual Telephone Company—shows Lincoln resting his hand on his ax and his foot on an unsplit log while he reads.

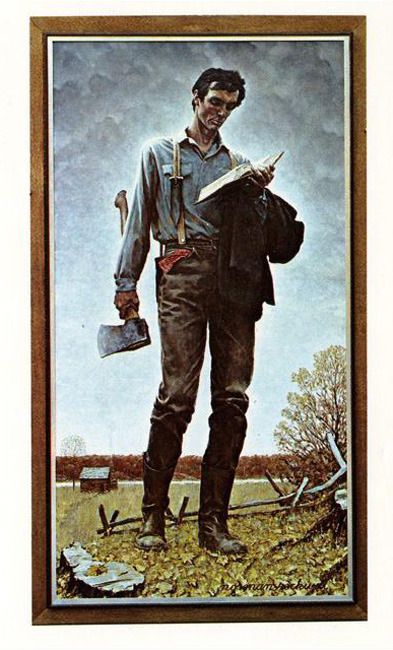

This postcard reproduces Norman Rockwell’s 1964 painting “Abraham Lincoln, Age 22.” Originally titled “The Young Woodcutter,” the painting shows Lincoln reading as he walks away from his rail splitting duties.

All these postcards, and hundreds of others, are held by the Lincoln Financial Foundation Collection. You can browse through all the collection’s postcards here.

22 notes

·

View notes