#a corrupted and aged and evil version of alfred makes the most sense. to me. who killed the world? us govt most likely

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

pruhun mad max fury road au.....save me pruhun mad max fury road au......

#I JUST THINK. IT SUITS THEM.#erzsi deserves a cool metal arm and a big fuckoff car and gilbert....well i think he would look cute in that muzzle thing#had to think long and hard about who immortan joe would be but honestly#a corrupted and aged and evil version of alfred makes the most sense. to me. who killed the world? us govt most likely#wouldnt be a 1:1 equivalent to the movie but the vague plot/vibes#text#hws prussia#hws hungary#pruhun#are there even enough women in hetalia for all five wives? stay tuned

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alright, time for some pretentious sociological-esque rambling. This is gonna be long as hell (its 1822 words to be specific) and I don’t begrudge anyone for not having the patience to read my over-thought perspectives on a murder clown. CWs for: child abuse,

I think a lot of things have to go wrong in someone’s life for them to decide to become a clown themed supervillain. A lot of people in Gotham have issues but they don’t become the Joker. I think that as a writer it’s an interesting topic to explore, and this is especially true for roleplaying where a character might be in different scenarios or universes. This isn’t some peer reviewed or researched essay, it’s more my own personal beliefs and perspectives as they affect my writing. I think villains, generally, reflect societal understandings or fears about the world around us. This is obviously going to mean villains shift a lot over time and the perspective of the writer. In my case, I’m a queer, fat, mentally ill (cluster B personality disorder specifically) woman-thing who holds some pretty socialist ideas and political perspectives. My educational background is in history and legal studies. This definitely impacts how I write this character, how I see crime and violence, and how my particular villains reflect my understandings of the society I live in. I want to get this stuff out of the way now so that my particular take on what a potential origin story of a version of the Joker could be makes more sense.

Additionally, these backstory factors I want to discuss aren’t meant to excuse someone’s behaviour, especially not the fucking Joker’s of all people. It’s merely meant to explain how a person (because as far as we know that’s all he is) could get to that point in a way that doesn’t blame only one factor or chalk it up to “this is just an evil person.” I don’t find that particularly compelling as a writer or an audience member, so I write villains differently. I also don’t find it to be particularly true in real life either. If you like that style of writing or see the Joker or other fictional villains in this way, that’s fine. I’m not here to convince anyone they’re wrong, especially not when it comes to people’s perspectives on the nature of evil or anything that lofty. Nobody has to agree with me, or even like my headcanons; they’re just here to express the very specific position I’m writing from.

The first thing I wanna do is set up some terms. These aren’t academic or anything, but I want to use specific and consistent phrasing for this post. When it comes to the factors that screw up someone’s life significantly (and in some instances push people towards crime), I’ll split them into micro and macro factors. Micro factors are interpersonal and personal issues, so things like personality traits, personal beliefs, mental health, family history, where and how someone is raised, and individual relationships with the people around them. Macro factors are sociological and deal with systems of oppression, cultural or social trends/norms, political and legal restrictions and/or discrimination, etc. These two groups of factors interact, sometimes in a fashion that is causative and sometimes not, but they aren’t entirely separate and the line between what is a micro vs macro issue isn’t always fixed or clear.

We’ll start in and work out. For this character, the micro factors are what determine the specifics of his actions, demeanor, and aesthetic. I think the main reason he’s the Joker and not just some guy with a whole lot of issues is his world view combined with his personality. He has a very pessimistic worldview, one that is steeped in a very toxic form of individualism, cynicism, and misanthropy. His life experience tells him the world is a cold place where everyone is on their own. To him the world is not a moral place. He doesn’t think people in general have much value. He learned at a young age that his life had no value to others, and he has internalized that view and extrapolated it to the world at large; if his life didn’t matter and doesn’t matter, why would anyone else’s? This worldview, in the case of my specific Joker, comes from a childhood rife with abandonment, abuse, and marginalization. While I will say he is definitively queer (in terms fo gender expression and non conformity, and sexuality), I’m not terribly interested in giving specific diagnoses of any mental health issues. Those will be discussed more broadly and in terms of specific symptoms with relation to how they affect the Joker’s internal experience, and externalized behaviours.

His childhood was, to say the least, pretty fucked up. The details I do have for him are that he was surrendered at birth because his parents, for some reason, did not want to care for him or could not care for him; which it was, he isn’t sure. He grew up effectively orphaned, and ended up in the foster care system. He wasn’t very “adoptable”; he had behavioural issues, mostly violent behaviours towards authority figures and other children. He never exactly grew out of these either, and the older he got the harder it was to actually be adopted. His legal name was Baby Boy Doe for a number of years, but the name he would identify the most with is Jack. Eventually he took on the surname of one of his more stable foster families, becoming Jack Napier as far as the government was concerned. By the time he had that stability in his mid to late teens, however, most of the damage had already been done. In his younger years he was passed between foster families and government agencies, always a ward of the government, something that would follow him to his time in Arkham and Gotham’s city jails. Some of his foster families were decent, others were just okay, but some were physically and psychologically abusive. This abuse is part of what defines his worldview and causes him to see the world as inherently hostile and unjust. It also became one of the things that taught him that violence is how you solve problems, particularly when emotions run high.

This was definitely a problem at school too; moving around a lot meant going to a lot of different schools. Always being the new student made him a target, and being poor, exhibiting increasingly apparent signs of some sort of mental illness or disorder, and being typically suspected as queer (even moreso as he got into high school) typically did more harm than good for him. He never got to stay anywhere long enough to form deep relationships, and even in the places where he did have more time to do that he often ended up isolated from his peers. He was often bullied, sometimes just verbally but often physically which got worse as he got older and was more easily read as queer. This is part of why he’s so good at combat and used to taking hits; he’s been doing it since he was a kid, and got a hell of a lot of practice at school. He would tend to group up with other kids like him, other outcasts or social rejects, which in some ways meant being around some pretty negative influences in terms of peers. A lot of his acquaintances were fine, but some were more... rebellious and ended up introducing Jack to things like drinking, smoking cigarettes, using recreational drugs, and most important to his backstory, to petty crimes like theft and vandalism, sometimes even physical fights. This is another micro factor in that maybe if he had different friends, or a different school experience individually, he might have avoided getting involved in criminal activities annd may have been able to avoid taking up the mantle of The Joker.

Then there’s how his adult life has reinforced these experiences and beliefs. Being institutionalized, dealing with police and jails, and losing what little support he had as a minor and foster child just reinforced his worldview and told him that being The Joker was the right thing to do, that he was correct in his actions and perspectives. Becoming The Joker was his birthday present to himself at age 18, how he ushered himself into adulthood, and I plan to make a post about that on its own. But the fact that he decided to determine this part of his identity so young means that this has defined how he sees himself as an adult. It’s one of the last micro factors (when in life he adopted this identity) that have gotten him so entrenched in his typical behaviours and self image.

As for macro factors, a lot of them have to do specifically with the failing of Gotham’s institutions. Someone like Bruce Wayne, for example, was also orphaned and also deals with trauma; the difference for the Joker is that he had no safety net to catch him when he fell (or rather, was dropped). Someone like Wayne could fall into the cushioning of wealth and the care of someone like Alfred, whereas the Joker (metaphorically) hit the pavement hard and alone. Someone like the Joker should never have become the Joker in the first place because the systems in place in Gotham should have seen every red flag and done something to intervene; this just didn’t happen for him, and not out of coincidence but because Gotham seems like a pretty corrupt place with a lot of systemic issues. Critically underfunded social services (healthcare, welfare, children & family services) that result in a lack of resources for the people who need them and critically underfunded schools that can’t offer extra curricular activities or solid educations that allow kids to stay occupied and develop life skills are probably the most directly influential macro factors that shaped Jack into someone who could resent people and the society around him so much that he’d lose all regard for it to the point of exacting violence against others. There’s also the reality of living in a violent culture, and in violent neighbourhoods exacerbated by poverty, poor policing or overpolicing, and being raised as a boy and then a young man with certain gendered expectations about violence but especially ideas/narratives that minimalize or excuse male violence (especially when it comes to bullying or violent peer-to-peer behaviour under the guise of ‘boys will be boys’).

Beyond that, there’s the same basic prejudices and societal forces that affect so many people: classism, homphobia/queerphobia, (toxic) masculinity/masculine expectations, and ableism (specifically in regards to people who are mentally ill or otherwise neurodivergent) stand out as the primary factors. I’m touching on these broadly because if I were to talk about them all, they would probably need their own posts just to illustrate how they affect this character. But they definitely exist in Gotham if it’s anything like the real world, and I think it’s fair to extrapolate that these kinds of these exist in Gotham and would impact someone like The Joker with the background I’ve given him.

I have no idea how to end this so if you got this far, thank you for reading!

1 note

·

View note

Text

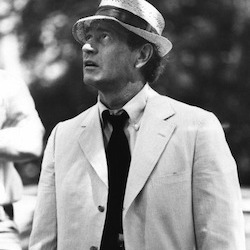

DARREN McGAVIN, MAN OUT OF TIME

Although Darren McGavin’s six decade career in movies and television carried him into the twenty-first century, his face and voice never changed in all those years, and they were a face and voice that somehow escaped the era in which they belonged. The more performances I see, especially later in his career, the more it occurs to me he was a man trapped in time, but who had somehow conned his way over the transom decade after decade without anyone noticing. Like so many great character actors from the Thirties and Forties, no matter the role—reporter, judge, general, doctor, cowboy—he was always just himself in a different costume, with the same subdued physicality, the same gestures and tics, a way of moving his head as if everything was a double-take, the same mildly-stammered delivery, and eyes that were less sad than resigned. In a Hollywood increasingly populated with “stars who are all but impossible to distinguish from one another, his tough features were both wide-eyed and sly, world-weary and innocent, but an innocence maintained despite circumstance and history. He had the face, it’s often occurred to me, of a more expressive Buster Keaton, or a Lee Tracy who’d been beaten with a lead pipe a few times.

As with most kids in the early Seventies, I first became aware of McGavin (born William Lyle Richardson in 1922) through the 1972 made-for-TV movie The Night Stalker. It was there that this notion of McGavin as a man out of time was solidified in my young brain, and deliberately so. Although on the surface a contemporary horror film about hardboiled investigative reporter Carl Kolchak chasing a vampire around modern-day Las Vegas, producer/director Dan Curtis made no bones about the fact it was quite consciously a throwback to the films he’d grown up with, that Kolchak was a character who dressed, spoke and acted like a character in a Thirties film regardless of his surroundings. And in fact with its blend of horror, comedy and sharp-tongued dialogue, the film plays much more like Doctor X (1932) than,,say, a Hammer film. The point was further driven home when the TB movie spawned a sequel and a short-lived series, both populated with guest stars who either made their names in the Thirties and Forties (Elisha Cook, Margaret Hamilton, John Carradine), or looked like they belonged there (John Marley, Wally Cox, Simon Oakland). The cluttered and grimy newspaper office where Kolchak works, his old Burroughs manual typewriter, and the fast-paced banter with his ever-frustrated editor could have been lifted directly from a Lee Tracy vehicle. His ever-present white seersucker suit and straw boater were merely the capper.

But let’s back up, because all this makes sense.

Although he made his screen debut with an all-but-uncredited role in 1945’s A Song to Remember, the earliest McGavin performance I’ve seen was in Alfred Zeisler’s Fear from a year later. In what amounts to a low-budget, dumbed-down and Americanized version of Crime and Punishment, a then-24-year-old McGavin plays one of a group of students trying to help a fellow medical student plagued with guilt after murdering a local loan shark. Although he only has a few lines and mostly lurks about the edges of the scenes he’s in, he is already unmistakable, even with bleach-blond hair and the standard collegiate sweater. He’s much thinner and lankier than he would be in later years, but there is already a cragginess to his features that belies his age.

Nine years later, after nearly a decade as a busy TV character actor, he came to national prominence as Louie, the cool, sinister, sharply dressed pusher in Otto Preminger’s Man With the Golden Arm. The tarnished innocence that would be as much a standard element of his m.o. as his streetwise cynicism is here buried deeply beneath an oily sheen, a wicked smirk and a pencil-thin mustache as he repeatedly lures Frank Sinatra into having another fix. What always struck me as interesting here is that although Louie is as far from the standard McGavin character as they come, he’s still a character from another era. Despite the film’s reputation at the time for being a searing, hard-hitting social drama, it remains as naive a picture as the novel it’s based on. By the mid-Fifties, Americans were well-familiar with the heroin problem, and McGavin plays Louie like an evil cartoonish peddler from the first wave of anti-drug propaganda films which emerged two decades earlier.

Toward the end of the Fifties, McGavin finally and fully came into his own, settling into the solid persona he would inhabit for the next half-century. The upstanding, street-smart and tenacious cop confronting police corruption in The Case Against Brooklyn (1958) and Mickey Spillane’s two-fisted private dick in the Mike Hammer TV series (1959) were both indistinguishable from the later Carl Kolchak, minus the boater, seersucker suit and monsters.

(As a sidenote, it was interesting to see McGavin playing opposite Ralph Meeker in one scene in The Night Stalker, considering both actors were known at the time for playing Mike Hammer, a character himself who was an anachronism in many ways.)

McGavin was one of those rare character actors who could play broad comedy as easily as intense drama, and who, though having spent much of his career playing supporting roles, could easily carry the lead. The same year The Night Stalker was aired, he starred with Sandy Dennis in Something Evil, Steven Spielberg’s made-for-TV follow-up to Duel. Predating The Exorcist by a year, McGavin and Dennis star as a couple who move into an old farmhouse that’s, yes, inhabited by Satan, who does his darndest to possess the wife.

Following a mid-Seventies run in which he appeared in a good deal of made-for-TV horror, McGavin was versatile enough to avoid being typecast. Three years after the Kolchak series ended, he appeared as an aeronautics engineer opposite marine biologist Christopher Lee in the all-star disaster sequel Airport ’77, and an earnest but not humorless NASA official who finds himself overseeing the study of a crashed UFO in Hangar 18 (1980).

It was his memorable turn as the irascible, understanding, and inherently believable Old Man in Joe Clark’s enduring A Christmas Story—a film set in the 1940s, appropriately enough, and the last time I’ve heard a character utter the mild oath “rassafracken” onscreen—that McGavin entered the second phase of his career. Apart from occasional major roles in big budget action films and mid-budget crime dramas, he would spend much of the next twenty years playing testy but ultimately understanding fathers. He was Candace Bergen’s dad on Murphy Brown, Adam Sandler’s dad in some Adam Sandler comedy or another, and Lance Henrickson’s dad in the grim Chris Carter series Millennium. The latter—in which Henrickson himself was a refugee from another era—was McGavin’s second role in a Chris Carter series. Carter freely admitted Kolchak was the primary influence in the development of The X-Files, in which McGavin made a few appearances not as Kolchak and not as anyone’s dad, but as a retired Kolchak doppelganger who acts as a father figure to a new generation of investigators into strange phenomena. So even though he avoided being typecast by genre, he had a much more difficult time avoiding being typecast, simply put, as himself.

Ironically, and again it only makes sense as a man out of time, after appearing in nearly two hundred films and television shows, McGavin’s final screen appearance would be in 2008—two years after he died.

by Jim Knipfel

40 notes

·

View notes