#Zapatista Army of National Liberation

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Mexico’s Zapatistas warn Chiapas is on ‘the verge of civil war’

In a statement signed by 1,000 leading figures, including Noam Chomsky and Diego Luna, the EZLN say that they are coming under attack from paramilitary groups, who act with the ‘passive and active complicity’ of the authorities On May 22, Jorge López Santíz was hit by a bullet. It was an attack that also hit the heart of Mexico’s Zapatista Movement, the far-left group that controls territory in…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

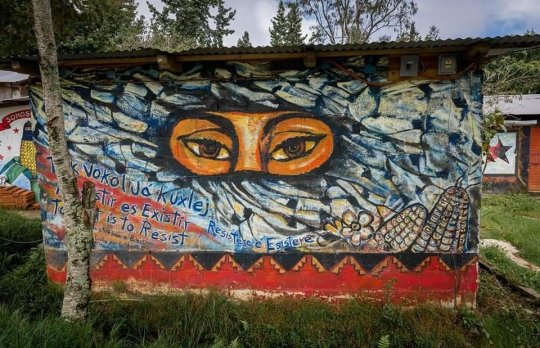

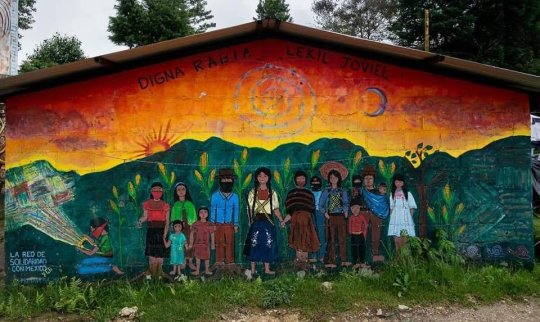

Radical murals seen around Oventic, an indigenous Zapatista village in Chiapas, Mexico.

On January 1st, 1994 the EZLN (Zapatista Army of National Liberation) launched an armed insurrection in Chiapas against the Mexican state and the NAFTA Free Trade Agreement.

The Zapatistas are a resistance movement of indigenous villagers in the mountains and jungles of Chiapas, Mexico’s poorest and southern-most state.

715 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN)

Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (EZLN)

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Somewhere in the Lacandon Jungle, Chiapas: The roots of the rebel Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) have long been intertwined with the roots of what remains of the Lacandon rainforest. The Tzeltal, Tojolabal, Tzotzil and Chol indigenous farmers who now form the core of the EZLN first came to the Lacandon as part of the great stream of settlers that poured into the forest 30 years ago. According to sociologists their long struggle to remain in the region, despite the objections of environmentalists dedicated to preserving the integrity of this unique lowland tropical jungle, have shaped the demands and the militancy of the Zapatista Army. Now, as tensions between the Zapatistas and the Mexican government ratchet up, environmentalists fear renewed hostilities could do irrevocable damage to the rainforest.

When the European invaders first reached this paradisical region in 1530, they literally could not find the forest for the trees. The rainforest extended from the Yucatan peninsula southwest, blending with the Gran Petan of Guatemala at the Usumacinta river, a swatch of jungle matched in the New World only by the Amazon basin. The Lacandon region was a three million acre wilderness of pristine rivers and lakes, its canopy teeming with Quetzales and Guacamayas under which lived ocelots and jaguars, herds of wild boar and tapir, and the Indians who gave the forest its name. The first Lacandones and the Spanish interlopers fought a guerrilla war that did not end until the Indians did — by 1769, there were just five elderly Lacandoes left living outside a mission on the Guatemalan bank of the Usumacinta.

The story of the Lacandon jungle is one of massacres, both of Indians and trees, relates Jan De Vos, the San Cristobal-based historian of the Chiapas rainforest. Soon after Chiapas won its independence from Guatemala and Spain, expeditions were sent to explore the “Desert (jungle) of Ocosingo” — De Vos uses its more poetic name “the Desert of Solitude” — all the way to the juncture of its great rivers, the Jacate and the Usumacinta. Timber merchants soon learned how to move logs on the rivers, and priceless mahogany and cedar groves began to fall. By the turn of the century the jungle was seething with logging camps — monterias — in which the Mayan Indians, gangpressed in Ocosingo, were chained to their axes and hanged from the trees. The conditions in the monterias were exposed to the world in the 1920s in a series of novels by the German anarchist writer Bruno Traven.

Foreign investors bought up huge chunks of the jungle — the Marquis of Comillas, a Spanish nobleman, still lends his name to a quarter of the forest. In the 1950s, Vancouver Plywood, a U.S. wood products giant, bought up a million acres of the Lacandon through Mexican proxy companies, and made another dent in the forest. The Mexican government later cancelled all foreign concessions and installed its own logging enterprise, initialed COFALASA, which took 10,000 virgin mahogany and cedar trees out of the heart of the Lacandon every year for a decade.

The settlers began to stream into the forest in the 1950s, boosted by government decrees that deemed the Lacandon apt for colonization. Choles, pushed out of Palanque, settled on the eastern flanks of the forest. Tzotzil Mayans from the highlands, expelled from landpoor communities like San Juan Chamula under the pretext of their conversion to Protestantism, arrived in the west of the Lacandon, as did landless Tzeltales and Tojolabales, newly freed from virtual serfdom on the great fincas (haciendas) of Comitan and Las Margaritas. In 1960 the Mexican government declared the Lacandon jungle the “Southern Agrarian Frontier” and non-Mayans joined the exodus into the forest. Oaxacan Mixes displaced from their communal lands by government dams, campesinos from Veracruz uprooted by the cattle ranching industry, and landless mestizos from the central Mexican states of Guerrero and Michoacan all pushed through Ocosingo, Las Margaritas and Altamirando, on their way down to the canyons — Las Canadas — towards the heart of the forest. The land rush narrowed the dimensions of the Lacandon and upeed its population considerably. In 1960 the municipality of Ocosingo had a population of 12,000 — the 1990 census was 250,000.

The new settlers were not kind to the forest. Infused with pioneer spirit, the campesinos cut the forest without mercy to charter and extend their ejidos (rural communal production units). Other settlers were more footloose, aligned themselves with the cattle ranchers, slashed and burned their way into the Lacandon, planted a crop or two, and abandoned the land to a cattle ranching industry fueled by World Bank credits. The zone of Las Canadas, the Zapatista base area, was one of the most devastated by the logging and cattle industries.

Two government decrees sought to brake the flow into the forest but backfired badly. In 1972, President Luis Echeverria turned 645,000 hectares of the jungle over to 66 second-wave Lacandon families and ordered all non-Lacandones evicted — settler communities were leveled by the military. Seeking to crystalize communal organizations that could defend the settlers from being thrown off the land they had wrested from the jungle, San Cristobal de las Casa’s liberation Bishop Samuel Ruiz sent priests and lay workers into the region to build campesino organizations such as the Union of Unions, Union Quiptic, and the ARIC — formations from which the Zapatistas arose years later.

Then, in 1978, a new president, Jose Lopez Portillo, added to the turmoil by designating 380,00 hectares at the core of the jungle as the UNESCO-sponsored Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve, declaring that all settlers living inside its boundaries must leave. Forty ejidos, twenty-three of them in the Canadas, were threatened. A young EZLN officer, Major Sergio, remembers well the struggle of his family to stay on their land in Montes Azules: “the government would not hear our petitions. We were left with no road except to pick up the gun.”

Many Zapatista fighters — the bulk of the fighting force is between 16 and 24 years old — were born into the struggle of their parents to stay in the Lacandon in defiance of the Montes Azules eviction notice. “The first experience the young colonos of Las Canadas had with a factor external to their lives was the pressure brought by environmentalists to preserve the forest,” writes sociologist Xochitl Leyva in Ojarasca, a journal of indigenous interests.

A 1989 environmentalist-backed ban on all wood-cutting in the Lacandon also led to resistance and frequent clashes with the newly-created Chiapas forestry patrols. In one of the first EZLN actions, two soldiers, thought to have been confused with forestry patrolmen, were killed in March 1993 near a clandestine sawmill outside San Cristobal.

The EZLN uprising has highlighted the development vs. conservation controversy that has raged in the Lacandon for generations. The EZLN demand that new roads be cut into the region drew immediate objection from the prestigious Group of 100, which, under the pen of poet-ecologist Homero Aridjis, complained the new roads would mean “the death of the Lacandon.” The Zapatista demand for land distribution also worries Ignacio March, chief investigator at the Southeast Center for Study and Investigation (CEIS), who fears the jungle will be “subdivided” to accomodate the rebels.

“Ecologists? Who needs them? What we need here is land, work, housing,” Major Mario remarked to La Jornada earlier this winter, when questioned about the opposition of the environmental community to EZLN demands.

The June 10th EZLN turndown of the Mexican government’s 32-point peace proposal has heightened fears of renewed fighting, a worst-case scenario for ecologists. S. Jeffrey Wilkerson, director of the Veracruz-based Center for Cultural Ecology worries that a military invasion of the Lacandon by the Mexican Army would mean the cutting of many roads into untouched areas, the use of destructive heavy machinery, the detonation of landmines, bombings and devastating forest fires and even oil well blow-outs.

Because of national security considerations, PEMEX, the government petroleum consortium, does not disclose the number of wells it is drilling in the Lacandon — some researchers think there are at least a hundred. From the air, the roads dug between oil platforms scar the jungle floor, and painful bald patches encircle the drilling stations.

One of the Zapatistas’ most important contributions to preserving the integrity of the Lacandon was to force 1400 oil workers employed by PEMEX, U.S. Western Oil, and the French Geofisica Corporation to shut down operations and abandon their stations during the early days of the war.

Despite disputes with the environmental community, the EZLN may be one of the most ecologically-motivated armed groups ever to rise in Latin America. The Zapatista Revolutionary Agrarian Law calls for an end to “the plunder of our natural wealth” and protests “the contamination of our rivers and water sources,” supports the preservation of virgin forest zones and the reforestation of logged-out areas. The lands they demand, the rebels insist, should not be shorn from the Lacandon but rather stripped from the holdings of large landowners.

The EZLN approach to the forest in which they and their families have lived for decades draws grudging approval from some environmentalists. “Few armed groups have ever included these kinds of demands in their manifestos” comments CIES investigator Miguel Sanchez-Vazquez. Andrew Mutter of the Lacandon preservationist Na’Bolom Institute is also sympathetic to the environmental roots of the EZLN: “this revolution rose from the ashes of a dead forest...”

#ecologist#Processed World#Zapatistas#deep ecology#anarchism#revolution#climate crisis#ecology#climate change#resistance#community building#practical anarchy#practical anarchism#anarchist society#practical#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy#economics#anarchy works

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

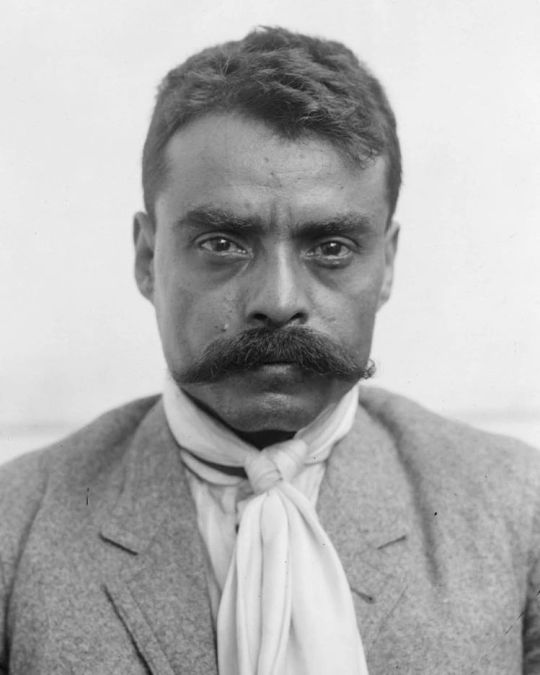

On this day, 10 April 1919, Emiliano Zapata, peasant leader during the Mexican revolution of Nahua Indigenous and Spanish descent, was assassinated in Chinameca, Ayala, by the "revolutionary" Carranza government. Early in life, he began to advocate for the rights of Indigenous peoples in Morelos when he saw wealthy landowners continually stealing their land, with no response from the government. So he began taking part in armed land occupations. With the outbreak of revolution in 1910, Zapata became the leader of the Liberation Army of the South. The force was a peasant militia fighting for "tierra y libertad" (land and freedom), a slogan they adopted from Mexican anarchist Ricardo Flores Magón. After Francisco Madero took power in 1911, Zapata denounced him for betraying the revolution, and drafted the Ayala Plan: a radical programme of land reform. Madero himself was then overthrown by counter-revolutionary Victoriano Huerta. Zapata's southern army allied with the revolutionary armies in the north, led by Pancho Villa and Venustiano Carranza. They soon overthrew Huerta, and called a convention to form the new government, which Zapata declined to participate in as none of the organisers had been elected. With Carranza in power, he only implemented moderate reforms, which fell well short of the Ayala plan, so the Zapatistas fought on. Carranza put a bounty on Zapata's head, hoping that one of his own fighters would betray him, but none of them did. In the end he was lured to a meeting with one of Carranza's men who pretended to be interested in defecting. When Zapata arrived for the meeting he was riddled with bullets, and his body photographed for propaganda purposes. He remains to this day a national hero, and Indigenous rebels in Chiapas who rose up in 1994 and created an autonomous territory named themselves after him. Learn more in this biography and check out our reproduction of an iconic photo of him: https://shop.workingclasshistory.com/collections/all/emiliano-zapata https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=606761904830362&set=a.602588028581083&type=3

254 notes

·

View notes

Text

On this day, 1 January 1994, the Zapatista uprising began, when Indigenous peoples in Chiapas, Mexico rose up and began reclaiming land.

As the North American Free Trade Agreement was due to come into effect, around 1000 members of the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) occupied the towns of Altamirano, Las Margaritas, Ocosingo, and San Cristobal de las Casas.

They released a statement declaring: “For many years, dictators have engaged in an undeclared genocidal war against our people. For this reason, we ask for your participation and support in our struggle for jobs, land, housing, food, health, education, independence, liberty, democracy, and justice, and peace. We will not stop fighting until these basic demands are met and a free and democratic government rules in Mexico.”

The rebels battled 14,000 Mexican colonial troops and police, and took over municipal buildings. In San Cristobal de las Casas, Zapatistas destroyed land records, and freed over 230 prisoners, most of whom were Indigenous peasants who had been locked up due to land disputes.

After 11 days of heavy fighting, a ceasefire agreement was reached, and between 159 and 300 people were dead. The Mexican army were accused of carrying out summary executions, arbitrary arrests and torture.

In their new, autonomous areas, Indigenous peoples took control of their communities, redistributed power and organised new, directly democratic ways of running society.

Despite state repression, violence and massacres, their movement of around 300,000 people remains self-managed to this day.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

For all those worried or confused about the recent communiques from the Zapatistas, I highly recommend giving this a read

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) was founded Nov. 17, 1983 in the Lacandon Jungle in Chiapas, Mexico by three indigenous and three non-indignous members of its parent organization, the Forces of National Liberation (FLN).

58 notes

·

View notes

Note

https://www.tumblr.com/dog-park-dissidents/754912605032857600/tango-your-dastardly-master-of-ceremonies-fancy?source=share

this might be a dumb question but what is the flag that Manny has?

That would be the flag of the EZLN, or the Zapatista Army of National Liberation. The Zapatistas are an indigenous anarchist society that have been in a cold war with the Mexican state since 1994, and they control some of the territory of Chiapas.

Manny grew up going to a Zapatista school and their revolutionary politics formed his moral center, but he'd later leave for Argentina to go pursue the art of tango dance and supervillainy.

Anyway Rage Against The Machine wrote "People of the Sun" about them

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flag Wars Bonus Round

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Declaración del Encuentro de la Red Europa Zapatista (Frankfurt 2024)

A las comunidades bases de apoyo zapatistas,

A los Gobiernos Autónomos Locales,

Al Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional,

Al Congreso Nacional Indígena (CNI),

A las compañeras, compañeros, compañeroas de la Sexta en el mundo,

A los pueblos que luchan desde abajo y a la izquierda,

Compañeras, compañeros, compañeroas,

A tres años de la llegada del…

Declaration of the Meeting of the Zapatista Europe Network (Frankfurt 2024)

To the Zapatista support base communities,

To the Local Autonomous Governments,

To the Zapatista Army of National Liberation,

To the National Indigenous Congress (CNI),

To the companions, companions, companions of the Sixth in the world,

To the people who fight from below and to the left,

Companions, companions, companions,

Three years after the arrival of…

#zapatistas#161#1312#anti capitalism#antinazi#jewish antizionism#antizionist#anti colonialism#europe#fortress europe#anti cop#anti colonization#eat the rich#eat the fucking rich#ezln#ausgov#politas#auspol#tasgov#taspol#australia#fuck neoliberals#neoliberal capitalism#anthony albanese#albanese government#antifa#antifascist#antifascismo#antifaschistische aktion#antifaschismus

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's January 1st, and I am thinking about Comandanta Ramona, an officer of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, a revolutionary indigenous autonomist organization based in the southern Mexican state of Chiapas. She led the Zapatista Army into San Cristóbal de las Casas during the Zapatista uprising on January 1, 1994. Today, I honor the 30th anniversary of the uprising.

Zapatistas emerged from decades of organizing among Indigenous peoples to address the systemic issues of poverty, discrimination, and lack of representation faced by Indigenous communities in Mexico. They demanded that the government recognize their rights to land, autonomy, and self-determination and called for a new political and economic system that would benefit all Mexicans, not just the wealthy elite. As is human nature, no one is perfect. The Zapatistas honor this and take care to learn from their mistakes.

The uprising was a call to action for marginalized communities worldwide and continues to inspire movements for Indigenous rights and social change. Though their initial spark in 1994 came with physical conflict with the Mexican military, the Zapatistas have since focused their efforts on building autonomous communities that are centered around their Indigenous traditions while seeking to create what they refer to as “‘Un Mundo Donde Quepan Muchos Mundos’ (‘A World Where Many Worlds Fit’) by emphasizing the dignity of ‘others,’ belonging, and common struggle, as well as the importance of laughter, dancing, and nourishing children.”

"Zapatismo is not a new political ideology, or a rehash of old ideologies. Zapatismo is nothing, it does not exist. It only serves as a bridge, to cross from one side, to the other. So everyone fits within Zapatismo, everyone who wants to cross from one side, to the other. There are no universal recipes, lines, strategies, tactics, laws, rules, or slogans. There is only a desire – to build a better world, that is, a new world."-Clandestine Revolutionary Indigenous Committee Zapatista Army of National Liberation

There is much to learn from the Zapatista Revolution and movement, like the demand for equity and belonging and the honoring of all that is ancestral. Every January 1st, I make it a practice to become reacquainted with the seven Zapatista principles as I set my intentions for the year.

1. Obedecer y No Mandar (To Obey, Not Command)

This Zapatista principle emphasizes the importance of executing the will of the people, while holding a position of leadership. In Zapatista autonomous communities, leadership positions are short-lived. This reflects the need for leaders to obey the collective desires of the community rather than command them from a position of power.

2. Proponer y No Imponer (To Propose, Not Impose)

Humility is a key part of life for the Zapatistas and aligns with their practice of debate and self-reflection. Therefore this principle is birthed from Zapatista culture of proposing a path forward and not imposing one.

3. Representar y No Suplantar (To Represent, Not Supplant)

Deriving from the Zapatista understanding that before the colonizer arrived, Indigenous people governed themselves. This principle is guided by the importance of self-governance for the Zapatistas and is grounded in the collective trust of the community to represent what the community wants.

4. Convencer y No Vencer (To Convince, Not Conquer)

The principle to convince not conquer is important to the Zapatista practice of dialogue and assembly. For the Zapatistas convincing requires logical argument, reflection, consideration of many viewpoints, and open discussion.

5. Construir y No Destruir (To Construct, Not Destroy)

The fifth principle is rooted in an ethic of anti-destruction and an end to exploitation. This principle is a practice in creating the institutions and the world that we want. This includes the unique Zapatista view of both relationships to humans and the land.

6. Servir y No Servirse (To Serve Others, Not Serve Oneself)

A traditional value for the Indigenous people of Chiapas is humility. The Zapatista slogan, ‘Para todos todo, para nosotros nada’ (Everything for Everyone, Nothing for Ourselves), is at the core of this principle. Every Zapatista must find a balance in serving others for the collective while taking care of their individual family work.

7. Bajar y No Subir (To Work From Below, Not Seek To Rise)

In Zapatista communities ‘trabajo colectivo’ (collective work), is a way of life. This seventh principle aligns with the mentality of working at the grassroots level for the benefit of your community.

Happy New Year!

#zapatistas#indegenous#human rights#humanity#mexico#history#on this date#happy new year#january 1st#1990s#resistance#oppression#free all oppressed peoples#free palestine#free gaza#freedom#inspirational quotes#inspiring quotes#intersectional activism#activism

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Separatist and irredentist movements in the world

Zapatista

Proposed state: Chiapas

Region: Chiapas, Mexico

Ethnic group: Mayans

Goal: independence

Date: 1820s

Political parties: -

Militant organizations/advocacy groups: Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN)

Current status: active

History

7000 BCE - first human occupation

250-1697 CE - Maya civilization

1522 - Spanish arrival

1810-1821 - Mexican War of Independence

1823 - Chiapas declares independence from Mexico

1824 - declaration of the State of Chiapas

1867-1870 - “caste war”

1910-1920 - Mexican Revolution

1983 - creation of the EZLN

1994 - Zapatista uprising

1997 - Acteal massacre

2005 - Sixth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle

The first human beings settled in present-day Chiapas around the 7th century BCE. The most important civilization to emerge was the Maya one. The Spanish arrived in the 16th century and did not leave the region until Mexico’s achieved its independence in 1821.

After the creation of the United Provinces of Central America in 1823, some Chiapanecan towns wished to join the new republic and declared independence from Mexico. However, after a referendum, Chiapas joined Mexico.

The “caste war” was a Tzotzil uprising due to religion and pitted the Liberals against the Conservatives. Poor farmland and poverty affecting Maya people led to non-violent protests and eventually an armed struggle led by the EZLN. Zapatista forces occupied several towns after the entry into force of the NAFTA. In 1997, 45 unarmed Tzotzil peasant were killed by government forces. In 2005, the Zapatistas published the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle, where they stated their principles and vision for Mexico.

Maya people

There are around 8 million Maya, of which 7 million live in Guatemala. The rest of them live in Belize, Honduras, Mexico, and the United States. The Tzotzil are the indigenous Maya in Chiapas. They number almost 300,000 people.

They speak Tzotzil, a Maya language, and Spanish, and practice a syncretist form of Catholicism that incorporates elements from their traditional religion.

Vocabulary

(Spanish - Tzotzil - English)

Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional - Zapatista Army of National Liberation

Estado Libre y Soberano de Chiapas - Skotol Yosilal Chyapas - Free and Sovereign State of Chiapas

México - Meejikoo - Mexico

lengua tzotzil - Batsʼi kʼop - Tzotzil language

pueblo tzotzil - Sotz’leb - Tzotzil people

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN)

Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (EZLN)

551 notes

·

View notes

Text

In December of 1994, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) revealed the existence of 32 rebel indigenous municipalities, which are known as autonomous municipalities, within the district lines of the official municipalities.

The autonomous municipalities are the organization of the rebel peoples of Chiapas for resistance. The war and the militarization prevent the people, in many cases, from going to the municipal seats in order to resolve their immediate problems; the soldiers at the checkpoints assault and interrogate every person suspected of being a zapatista: that is, all poor campesinos. There have been instances of rape against women at the military checkpoints, and also of kidnappings and attacks.

The lack of freedom of movement in the state has also forced the appearance of the autonomous and rebel municipalities.

Some autonomous municipalities have opened their own marriage, birth and functions registries, because, since 1994, many villages have stopped utilizing official services, because they belong to the civil support structure of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation.

Completely abandoned by state institutions, and without basic services, the indigenous communities of Chiapas have opted to resolve some of their own problems through self-organization.

The legitimacy of the autonomous municipalities is based in the Treaty 169 of the International Labor Organization (ILO), to which Mexico is a signatory, and which recognizes the rights of the indigenous peoples to live according to their uses and customs. In addition, municipal autonomy is recognized in Article 115 of the Mexican Constitution.

For the rebel peoples of Chiapas, the creation of the Autonomous Municipalities is also a means for carrying out the San Andres Accords. On February 16, 1996, the Mexican government signed the Accords on Indigenous Rights and Culture with the EZLN. These accords were to have been transformed into constitutional changes. But the Mexican government rejected the legislative proposal of the Commission of Concordance and Peace — made up of all the political forces in the Congress of the Union — which they had prepared in December of 1996.

The carrying out of the San Andres Accords on indigenous rights is still not resolved, and it is one of the EZLN’s essential requirements for returning to the dialogue table.

The EZLN maintains that the autonomous municipalities are legitimate, given that they are the results of the application of the San Andres Accords, which the govenrment signed, and which it now refuses to recognize.

#autonomous communities#Chiapas#Indigenous#Zapatistas#autonomous zones#autonomy#anarchism#revolution#climate crisis#ecology#climate change#resistance#community building#practical anarchy#practical anarchism#anarchist society#practical#daily posts#communism#anti capitalist#anti capitalism#late stage capitalism#organization#grassroots#grass roots#anarchists#libraries#leftism#social issues#economy

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 11.17 (after 1950)

1950 – Lhamo Dondrub is officially named the 14th Dalai Lama. 1950 – United Nations Security Council Resolution 89 relating to the Palestine Question is adopted. 1953 – The remaining human inhabitants of the Blasket Islands, Kerry, Ireland, are evacuated to the mainland. 1957 – Vickers Viscount G-AOHP of British European Airways crashes at Ballerup after the failure of three engines on approach to Copenhagen Airport. The cause is a malfunction of the anti-icing system on the aircraft. There are no fatalities. 1962 – President John F. Kennedy dedicates Washington Dulles International Airport, serving the Washington, D.C., region. 1967 – Vietnam War: Acting on optimistic reports that he had been given on November 13, U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson tells the nation that, while much remained to be done, "We are inflicting greater losses than we're taking…We are making progress." 1968 – British European Airways introduces the BAC One-Eleven into commercial service. 1968 – Viewers of the Raiders–Jets football game in the eastern United States are denied the opportunity to watch its exciting finish when NBC broadcasts Heidi instead, prompting changes to sports broadcasting in the U.S. 1969 – Cold War: Negotiators from the Soviet Union and the United States meet in Helsinki, Finland to begin SALT I negotiations aimed at limiting the number of strategic weapons on both sides. 1970 – Vietnam War: Lieutenant William Calley goes on trial for the My Lai Massacre. 1970 – Luna programme: The Soviet Union lands Lunokhod 1 on Mare Imbrium (Sea of Rains) on the Moon. This is the first roving remote-controlled robot to land on another world and is released by the orbiting Luna 17 spacecraft. 1973 – Watergate scandal: In Orlando, Florida, U.S. President Richard Nixon tells 400 Associated Press managing editors "I am not a crook." 1973 – The Athens Polytechnic uprising against the military regime ends in a bloodshed in the Greek capital. 1983 – The Zapatista Army of National Liberation is founded in Mexico. 1986 – The flight crew of Japan Airlines Flight 1628 are involved in a UFO sighting incident while flying over Alaska. 1989 – Cold War: Velvet Revolution begins: In Czechoslovakia, a student demonstration in Prague is quelled by riot police. This sparks an uprising aimed at overthrowing the communist government (it succeeds on December 29). 1990 – Fugendake, part of the Mount Unzen volcanic complex, Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan, becomes active again and erupts. 1993 – United States House of Representatives passes a resolution to establish the North American Free Trade Agreement. 1993 – In Nigeria, General Sani Abacha ousts the government of Ernest Shonekan in a military coup. 1997 – In Luxor, Egypt, 62 people are killed by six Islamic militants outside the Temple of Hatshepsut, known as Luxor massacre. 2000 – A catastrophic landslide in Log pod Mangartom, Slovenia, kills seven, and causes millions of SIT of damage. It is one of the worst catastrophes in Slovenia in the past 100 years. 2000 – Alberto Fujimori is removed from office as president of Peru. 2003 – Actor Arnold Schwarzenegger’s tenure as the governor of California began. 2012 – At least 50 schoolchildren are killed in an accident at a railway crossing near Manfalut, Egypt. 2013 – Fifty people are killed when Tatarstan Airlines Flight 363 crashes at Kazan Airport, Russia. 2013 – A rare late-season tornado outbreak strikes the Midwest. Illinois and Indiana are most affected with tornado reports as far north as lower Michigan. In all around six dozen tornadoes touch down in approximately an 11-hour time period, including seven EF3 and two EF4 tornadoes. 2019 – The first known case of COVID-19 is traced to a 55-year-old man who had visited a market in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China.

2 notes

·

View notes