#Yerba Buena Cemetery

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

books i read this year in vaguely chronological order

the verifiers - jane pek

the truth is - nonieqa ramos

tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow - gabrielle zevin

tomorrow will be different - sarah mcbride

i'm glad my mom died - jennette mccurdy

the first to die at the end - adam silvera

tell me i'm an artist - chelsea martin

sea of tranquility - emily st. john mandel

talking with my mouth full - gail simmons

yerba buena - nina lacour

the empress of salt and fortune - nghi vo

station eleven - emily st. john mandel

you made a fool of death with your beauty - akwaeke emezi

all systems red - martha wells

artificial condition - martha wells

our wives under the sea - julia armfield

we are okay - nina lacour

pageboy - elliot page

exit strategy - martha wells

fugitive telemetry - martha wells

xenocultivars: stories of queer growth - ed. isabela oliveira and jed sabin

love, loss, and what we ate - padma lakshmi

aristotle and dante discover the secrets of the universe - benjamin alire sáenz

margaret and the mystery of the missing body - megan milks

the seep - chana porter

this is how you lose the time war - amal el-mohtar and max gladstone

crying in h mart - michelle zauner

less - andrew sean greer

gender queer - maia kobabe

autoboyography - christina lauren

artemis - andy weir

the glass hotel - emily st. john mandel

less is lost - andrew sean greer

cemetery boys - aiden thomas

the hate u give - angie thomas

how high we go in the dark - sequoia nagamatsu

how far the light reaches - sabrina imbler

the candy house - jennifer egan

notes from a young black chef - kwame onwuachi

trust exercise - susan choi

overdue: reckoning with the public library - amanda oliver

girl mans up - m-e girard

#BEHOLD THE BOOKS THAT I READ#they were not all gay but...very many of them were gay lol#excited that i read all these books and excited to read some different books next year!#books#goodbye 2023

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

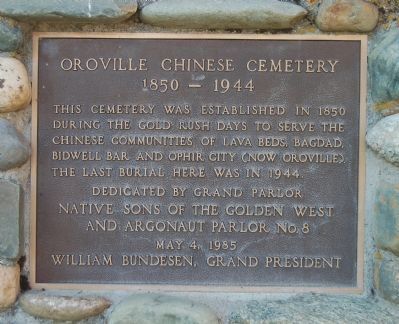

What most people in the Bay Area already know is that the city moved the vast majority of its dead to Colma in the 1930s. That, at least, is the common narrative. What Winegarner uncovers here is a far more shocking tale — one in which San Francisco remains awash with dead bodies that are simply lacking grave markers. And we’re not just talking about the handful that have popped up over the years during construction work.

The bodies that were moved to Colma came from San Francisco’s four main cemeteries — Laurel Hill, Masonic, Odd Fellows and Calvary — all of which were positioned on the north side of the city. However, San Francisco’s Forgotten Cemeteries thoroughly charts all of the other places that city dwellers once used as graveyards — and many are in unexpected, and under-discussed, locations. Dolores Park, for example, was a Jewish cemetery. Russian Hill is named for the fact that Russian sailors were buried there in 1848. Bodies were buried at First and Minna downtown. Most shockingly of all, Civic Center was once home to an enormous cemetery named Yerba Buena. (And a smaller one known as Green Oak.)

The Yerba Buena graveyard started at Market and Larkin and stretched all the way up to where City Hall stands today. It was opened in 1850, contained an unmarked mass grave of 800 bodies moved from North Beach, and was filled with between 7,000 and 9,000 bodies within the first eight years of its existence. In 1868, the dead were disinterred and moved again — at least, they were supposed to be. In truth, hundreds of bodies were left behind, under what is now Civic Center Plaza, City Hall, the Asian Art Museum and the Library.

According to Winegarner, few corners of the city are actually free of former residents’ bodies. Keep in mind that the Mission Dolores graveyard once contained between 10,000 and 11,000 bodies. And while only 200 or so are marked by gravestones today, thousands of dead remain under 16th Street and the surrounding buildings, many of them the Indigenous people who built the mission in the first place.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

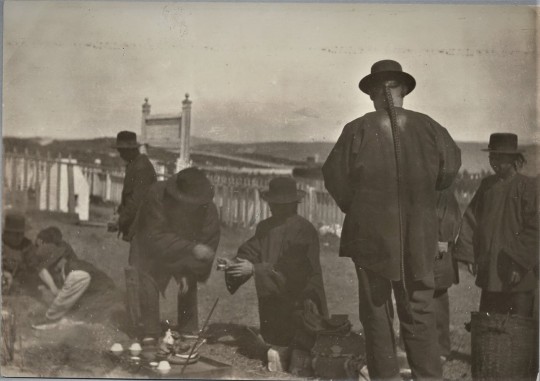

“Offerings to the Dead” (from the collection of the Bancroft Library). An unknown photographer reputedly took the above photo (from the Bancroft Library) of what some commentators have stated was a “burial” on Laurel Hill in San Francisco, California, in 1892. As no actual burial appears in the scene, the caption for the photo may more accurately have captured the observance of Qingming by Chinese San Franciscans with attending onlookers.

Qingming, Legacy Cemeteries, and Chinese American Funeral Processions over the Centuries

The Chinese pioneers to North America brought with them their observance of Qingming (清明节), also known in English as “Tomb-Sweeping Day”(掃墳節). Qingming falls on the first day of the fifth solar term of the lunar calendar, usually the 15th day after the Spring Equinox, which can either be 4, 5 or 6 April in a given year.

Historian Thomas W. Chinn in his book, Bridging the Pacific, described the day when families visit the tombs of their ancestors as follows:

“The pure brightness Festival (Ching Ming) is the Chinese version of Memorial Day. Visits to family tombs are a formal right in China. Because the Chinese in America were far from the family tombs of their native Villages, they would visit the local Chinese Cemetery area on this day. Various associations erected “spirit” shrines for those who had no loved ones buried in the area.

“In the San Francisco area, Ching Ming is generally celebrated on a Sunday early in April. Before World War II, Chinese could not be buried in Caucasian cemeteries, so Chinese cemeteries were established near Colma, California, South of San Francisco. Buses in carloads of Chinese would travel to Colma on Ching Ming to visit the shrines or the graves of loved ones.

“At the tomb, the elder of the family would carefully sweep the graves with willow branches to repel evil spirits. Then the family would clean and pull weeds from the grave. The final ritual involved laying cooked food in dishes before the graves for the deceased to “eat.” After a while, the roast pig, chicken, buns, and so on would be eaten as a picnic lunch at the site. Following lunch, wine would be poured on the ground, after which the remaining food was removed and taken to different families. No food was wasted.

“During the course of the ceremony the spirit offering would be made, consisting of lighted incense sticks and red candles, which, together with paper money and paper clothing (sold in certain stores in Chinatown), were burned and dust transmitted to the deceased for their comfort and needs in the spirit world. While these offerings were being burned, firecrackers were exploded to confuse evil spirits and keep them from pursuing the deceased. These same rituals are still observed by most of the older generation of Chinese in America, although offerings of food and incense and the exploding of firecrackers are not as common today.

“Funeral at Gravesite,” no date. Photographer unknown (from the collection of the California Historical Society). According to Woody LaBounty of the Western Neighborhoods Project, the location was probably the San Francisco cemetery in what is now the city’s Lincoln Park and golf course. “The camera person was facing to the northeast,” according to LaBounty. “The small building visible in the photo is the caretaker's cottage of the German M. B. Society. It would take a bit of work to say which plot the photo was taken in, but it could probably be done. [This and the following image] were apparently taken only a few seconds apart.”

“Ceremony in a Chinese cemetery” no date. Photographer unknown (from the collection of the California Historical Society). According to Woody LaBounty of the Western Neighborhoods Project, the location was probably the San Francisco cemetery in what is now the city’s Lincoln Park and golf course. Amidst the solemnity of the ritual offering, the absence of women from this haunting photo is palpable, as the men of the Exclusion era’s bachelor society venerate another departed pioneer of Chinese California.

When historian Thomas Chinn described Qingming as practiced by the “older generation” in 1989, he might not have foreseen its continued vitality as Chinese from the mainland, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore would continued to emigrate to the US. Wherever the diaspora calls home, they continue to celebrate the “festival” in much the same manner as the Chinese pioneers of California.

Chinese men making offerings of food, wine and incense probably in the Chinese cemetery in Colma CA. Photographer unknown (from the collection of the Bancroft Library).

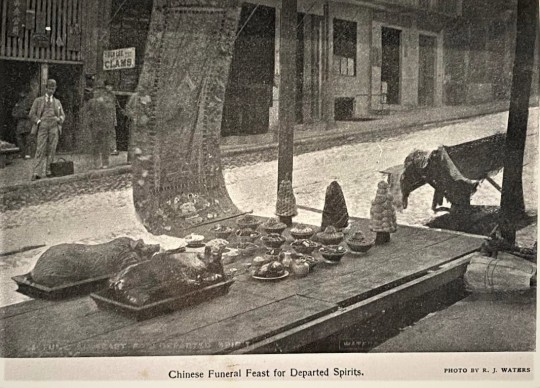

A close up of the offerings placed on the funerary platform and cenotaph probably at a Chinese cemetery in Colma, CA, c. 1890 - 1900. (Photograph by Louis J. Stellman, from the collection of the California Society of Pioneers and the Bancroft Library).

“Chinese Funeral Feast for Departed Spirits,” no date. Photograph by R.J. Waters. Local historian Art Siegel has identified the approximate location of this offering as across from Yuen Lee clam store at 719 Sacramento Street, based on a news item in the Daily Alta California of January 19, 1892:

Chinese and San Francisco’s Early Cemeteries

The annual veneration of ancestors during Qingming inevitably prompts questions about the early history of Chinese burials within the city limits of San Francisco at cemeteries such as the pioneer Yerba Buena Cemetery, Lone Mountain/Laurel Hill Cemetery, and the city’s cemetery once located on the grounds of today’s Lincoln Park. Much of the history remains obscure, but a master’s thesis by Kari L. Hervey-Lentz in 2022, titled “Remaking an Unmade Cultural Landscape: Mapping the Space and Exploring the Meaning of San Francisco’s Historical Cemeteries,” has made a major contribution to local understanding of early cemetery usage by the city’s pioneer Chinese community.

The first Chinese settlers in San Francisco community laid their deceased members to rest in Yerba Buena Cemetery. According to an early account, they occupied a separate area, distinct from the Christian burial section in Yerba Buena, which was described in one newspaper as a "strange looking place" used for the performance of their unique “genius and custom of their Pagan faith.” (J.L., 8 March 1857).

Yerba Buena Cemetery ceased burials in 1854, and the populace, including the Chinese, gravitated toward the Lone Mountain Cemetery. Newspaper accounts indicate that Chinese burials were already occurring at Lone Mountain by 1857 (citing California Farmer and Journal of Useful Sciences, 18 December 1857).

“A Chinese Funeral in Lone Mountain Cemetery, San Francisco, California,” drawn by Paul Frenzeny and published in the Harpers Weekly of January 28, 1882.

According to Hervey-Lentz, Chinese merchants in the city contributed to the construction of a receiving vault at Lone Mountain during the Fall of 1860. This vault served as a temporary resting place for prominent members of the Chinese community upon their passing, where various rituals were conducted. At its peak usage during the 1860’s, the vault held between 150 to 200 bodies at a time before their remains were repatriated to China. The Chinese community’s use of the vault proved short-lived.

“The old Chinese vault” sketch from the San Francisco Chronicle of March 25, 1888. Artist unknown.

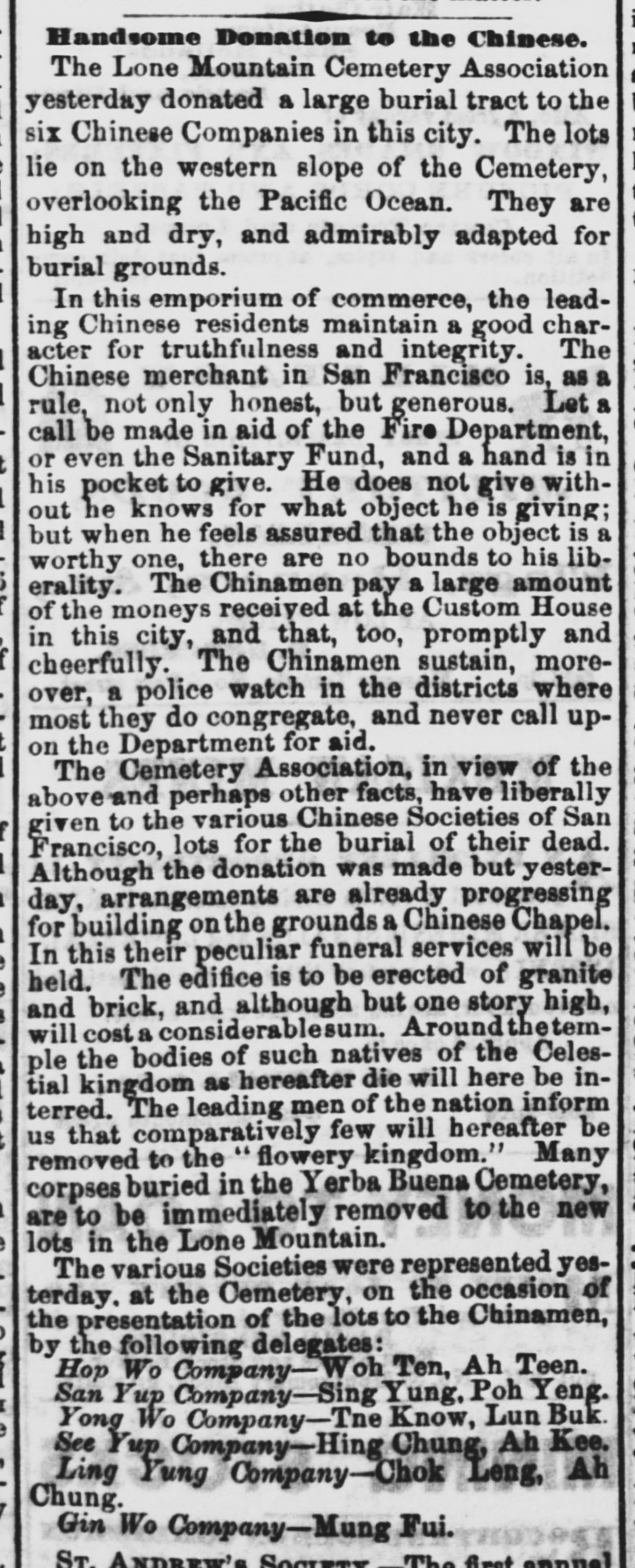

Growing anti-Chinese sentiments forced the relocation of the interment space to the western edge of the cemetery. Hervey-Lentz’s research of contemporary news accounts from the 1880’s identified this area, now roughly bounded today by Arguello Boulevard on the west, California Street on the north, Palm Avenue [east], and Euclid Avenue (south), became the resting place for Chinese remains.In describing this relocation, one newspaper (Daily Alta California, February 8, 1877) noted the shifting circumstances, stating that the Chinese “were deprived of the privileges of interring in Laurel Hill Cemetery” and subsequently relegated to a “narrow space” near Lone Mountain. This confined area, according to Hervey-Lentz, quoting from the Daily Alta California of November 25, 1863, “likely references land on the western slope of the cemetery that the Lone Mountain Cemetery Association had granted to the Chinese Six Companies (Hop Wo Company, San [sic] Yup Company, Yong Wo Company, Sze Yup Company, Ling [sic] Yung Company, and Gin Wo Company) in 1863.

“Handsome Donation to the Chinese,” as reported in the Daily Alta California of November 25, 1863.

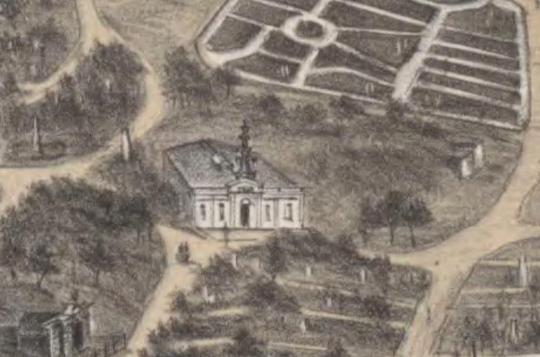

A newspaper article in the San Francisco Chronicle of March 25, 1888, included a sketch of the vault and mentioned that, after the Chinese community abandoned it, the structure served as a storage shed and tool shop for the cemetery groundskeepers. This information allowed for Hervey-Lentz to identify a tool shop building on a map from 1895, matching the architectural features of the vault depicted in the newspaper sketch. The structure measured approximately 40 feet in length by 24 feet in width, and there were graded pathways leading to its east-facing entrance. Notably, historical accounts indicate that Chinese funeral processions typically involved horse-drawn carts, making these pathways convenient for their ceremonies.

Lone Mountain Cemetery, San Francisco” c. 1866. Lithograph by Charles B. Gifford (from the collection of the Bancroft Library). The lithograph shows some of the architectural features of the central entrance, including its columns that flank two sunken panels. According to Kari Hervey-Lentz, “the structure was about 40 feet long by 24 feet wide and there would have been graded pathways that led to its east-facing entrance. . . . The structure in the 1866 image was embellished with an arched gable above the door in the Italianate style. However, Gifford identified the building as ‘other’ by drawing a fantastical and spindly pagoda on top of the structure. Although it is possible that the ornate pagoda structure was taken down before the 1885 sketch was made, the lack of other images showing this elaborate building within the cemetery coupled with the anti-Chinese sentiment of the time point towards Gifford’s 1866 embellishments as invention.”

The Chinese vault would survive into the next century. During the 1930’s, the renowned photographer Ansel Adams photographed the vault among other photos taken of the Laurel Hill Cemetery's architecture.

The entrance to the Chinese mausoleum in Laurel Hill Cemetery, San Francisco, c 1935-1936. Photograph by Ansel Adams and print prepared for his 1936 one-man exhibition at Stieglitz’s gallery An American Place—including Architecture, Early California Cemetery. Adams' photograph showcases striking architectural details of the building.

Kari Hervey-Lentz writes about Ansel Adams’ photo as follows:

“The image shows the bold architecture of the building, including an arch with sunray-like beams over the entryway. Niches with ornate arched lintels and protruding sills are captured, exactly matching the 1888 newspaper sketch. . . .Understanding that this image depicts Chinese-built architecture, and that within the architecture took place deeply meaningful spiritual and cultural practices to Chinese communities of San Francisco, provide an important context.”

Hervey-Lentz’s research about the chronology and destinations for Chinese mourners and officiants provide welcome context for the images of Chinese funeral processions of the 19th century.

Chinese Funeral Procession, Chinatown. Stockton near Pacific circa 1895 -- photographer J.S. Wooley (Courtesy of a Private Collector). This photo captured a view northwest across 1100 block of Stockton Street between Jackson and Pacific showing the west side of the street. A funeral procession with horse-drawn hearse leads mourners walking in the street. Quen Hop (or Quon Hop) underwear factory 1119 Stockton, appears in the background at right.

Jesse Brown Cook (1860-1938) served the San Francisco Police Department from the late 1880s to the 1930s. He began as a beat officer, and then served as a sergeant of the “Chinatown Squad.” He served as Chief of Police after the 1906 earthquake, retired, and was later appointed to the Police Commission. In his memoirs, Cook wrote about various aspects of the 19th century Chinese in the city and their customs, including funerary rites and the observance of the Qingming festival in the Chinese section of the cemetery out near the city’s Land’s End as follows:

“When I was a boy it was a great treat to go out to the Chinese burying grounds, now known as Lincoln Park. It was a long journey out there -- a long and a solemn one for the Chinese. The Chinese buried their dead in great state. They brought out choisest [sic] cooked foods for the dead to eat before they left the earth (the tramps and birds could be seen eating this later). As the procession moved through the cemetery they threw into the air small pieces of paper with holes. It was believed that the Devil or Evil Spirits had to pass through each little hole before reaching the spirit of the dead. Thus they could beat the Devil and get the body buried first so the Devil could not reach it.”

The few surviving cemeteries of Chinese California comprise part of the dwindling physical legacy of the Asian pioneers on the American frontier. Most Chinese were interred in segregated and often forgotten graves.

Re-touching gravesite information on markers at a Chinese cemetery (probably in Colma, CA) c. 1900. This photograph by Louis Stellman appears in Richard Dillon’s 1976 book for the Book Club of California, Images of Chinatown - Louis J. Stellman’s Chinatown Photographs.

View of a casket resting on a support in a street, wagon parked beyond; several men standing nearby; Chinese funeral preparations in San Francisco, Cal. Photograph by Goldsmith Bros. (from the collection of the California State Library).

The tourist travelogues of the late 19th century expressed constant fascination with the social fabric of old San Francisco Chinatown. The quality of such accounts varies widely, ranging from the profoundly ill-informed, or even racist, to the sometimes scholarly. Tourists to pre and post-1906 Chinatown often saw funeral rites conducted in the streets and recorded their obsersations. In an article published by The Pacific Tourist in 1878, F.E. Shearer wrote about Chinese funerary practices as follows:

“The funerals are conducted with great pomp. The corpse is sometimes placed on the sidewalk, with a roast hog, and innumerable other dishes of cooked food near it, when hired mourners with white sheets about them, and two or three priests as masters of ceremony, and an orchestra of their hideous music, keep up for hours such unearthly sounds as ought to frighten away all evil spirits.

“The wagon-load of food precedes the corpse to the grave, and from it is strewn “cash,” on paper to open an easy passage to the “happy hunting grounds” of the other world.

“’Ancestral Worship’ is the most common of all worship among the Chinese. Tablets may be seen in stores, dwellings and rooms connected with temples. Its origin is shrouded in mystery. One account derives it from an attendant to a prince about 350 B.C. The prince while traveling, was about to perish from hunger, when he cut a piece of flesh from his thigh, and had it cooked for his master, and perished soon after. When the prince found the corpse of the devoted servant, he was moved to tears, and erected a tablet to his memory, and made daily offerings of incense before it. Other absurd stories of filial devotion are told for the same purpose.

“The ancestral tablet of families, varies from two to three inches in width, and 12 to 18 in height, and some are cheap and others costly. There are usually three pieces of wood, one a pedestal and two uprights, but sometimes only two pieces are used. One of the upright pieces projects forward over the other from one to three inches.

“One tablet can honor only one individual, and is worshiped for from three to five generations. To the spirit of ancestors a sacrifice of meats, vegetables, fruits, etc., is often made with magnificence and pomp, and the annual worship of ancestral dead at their tombs, is of national observance, and occurs usually in April, and always 10 days after the winter solstice. . . .

Dupont Street funeral, c. 1895. Photographer unknown (from a private collection).

“The offerings are more plentiful than the meats at a barbcue in the Far South, carcasses of swine, ducks, chickens, wagon-loads of all sorts of food and cups of tea, are deposited at the graves; fire-crackers continually exploded, and mock money and mock clothing freely consumed. All kneel and bow in turn at the grave, from the highest to the lowest.

“As in the case of the gods, the dead consume the immaterial and essential elements, and leave the coarse parts for the living. Unlike the gods, the dead consume ducks. ‘Idol no likee duck, likee pork, chicken, fruits.’”

-- from Shearer, F.E., “The Chinese in San Francisco,” The Pacific Tourist, (Henry T. Williams pub., 1878), p. 323.

“Street Scene” of a funeral in San Francisco CA. No date. Photographer unknown (from the collection of the Bancroft Library)

A funeral parade on Dupont Street, c. 1900. Photographer unknown (from a private collection). The signage of the mercantile house, Sing Fat & Co., at 614 Dupont can be seen in the left of the photo.

As the presence of Chinese in North America lengthened, the various family and district associations assumed the responsibility for providing funeral and burial services on tracts of land devoted for Chinese use, including the construction of funerary incinerators and the appropriate positioning of grave plots according to feng shui (風水) principles.

The above photo appears to depict a funeral in Colma, California, c. 1903. Photographer unknown (from the collection of the Bancroft Library). The absence of women from the photo is palpable, as the men of the Exclusion era’s bachelor society lays to rest another pioneer of Chinese California.

Away from the major settlements, however, and in the smaller towns of the Sierra foothills, the cemeteries established by small Chinese communities eventually fell into disuse and decay, as Chinese were driven off or drifted back to the cities.

A Chinese funeral procession in Dutch Flat, CA.

Today, the discovery of Chinese graves often occurs during large-scale construction projects in areas that were settled during the mid-19th century. In 2005, the construction of the Metro Gold Line Eastside Extension revealed 174 unmarked Chinese graves in Boyle Heights.

In the Boyle Heights case, the LA Times reported in 2010 that all the bones and artifacts were reinterred inside Evergreen Cemetery which had originally banned Chinese interments. About 1,400 Chinese were believed to have been buried in the Boyle Heights potter’s field. According to the Times, and despite an outreach effort, the MTA was unable to identify any living relatives of the Chinese whose remains were uncovered during the digging for the Gold Line extension.

The Chinese who helped build California were forbidden to marry or own property, and they were generally barred for decades from using the secular burial grounds that served the state’s cities and towns. Moreover, the Chinese practice of unearthing bones for shipment back to the deceased’s ancestral village (as seen in the photo below); the practice complicated the maintenance of grave markers and even the identification of the locations of Chinese graves over subsequent decades.

Bone pickers in Colma CA.

“Cleaning the Bones of the Dead” (after disinterment) from “Chinese Life in San Francisco” engraving published in Harper’s Weekly, c. 1879. Illustrator unknown.

The cemeteries of Chinese California and elsewhere in the American West represent part of the vanishing physical legacy of the Chinese pioneers in far-flung rural communities. Many have only markers to show the locations of long-deceased ancestors.

Borden CA

A Chinese cemetery in Los Angeles CA, c. 1900. The funerary burner bears the date of September 1886. Location and photographer unknown from the California Historical Society Collection at the University of Southern California.

Conventional historical accounts assert that the practice of disinterring remains for shipment back to the ancestral villages in China continued in North America at least up to the 1949 communist victory in the Chinese civil war. The growth of families in the US, however, also induced many Chinese families to bury deceased family members in permanent plots in America, presumably to facilitate veneration of ancestors in the US.

Regardless of the changes in the ultimate disposition of ancestral bones, large funeral processions continued to represent significant occurrences on the Chinatown streetscape. My great grandmother’s death in December 1922 presented a notable and exceptional example of a community-wide honor to a woman. Contrary to the news report about the family’s original intent to send her bones to China, my great grandmother’s remains were permanently located in Olivet Cemetery in Colma CA.

As the above clipping from the San Francisco Examiner of December 25, 1922, attests, the rites and funeral procession for my great grandmother Hee Ching She (erroneously named “Chuck How” in the news article), made the news for its size and hundreds of women attendees.

The all-women head of the funeral procession for Mrs. Hee Ching She in San Francisco Chinatown on December 24, 1922.

The San Francisco Examiner reported that the December 24, 1922, funeral procession for Mrs. Hee Ching She “strung along for three city blocks, the women halted first in front of the decedent’s home, 620 Clay street, then again in front of the home of the [actually younger] son, at 705 Kearny street, finally disbanding at the corner of Pine street and Grant avenue.”

The southbound funeral procession of prominent businessman Chin Bok Lain (1869 - 1938) as viewed from the balcony of the Hang Far Low restaurant overlooking Grant Avenue toward the intersection of Grant and California Street at the top of the photo. A brief account of Chin’s life by his descendant, Kenneth J. Hong, may be read here.

The acceleration of Chinese American family formation and growth because of the enactment of the War Brides Act and the Immigration Act of 1965 also strengthened the practice of permanently locating and venerating ancestral graves in communities across North America.

Families present offerings and burn paper money for their ancestors in the Chinese section of the Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland CA, on Qing Ming or Tomb Sweeping Festival day in 2021. (Photo by Doug Chan)

Although terrain may vary, the old rules of grave location, e.g., south to a hill or north toward water in front of the grave, and ideally with a “mountain behind and luxuriant plants around” remain desirable. Over the course of events during the 20th century, Qing Ming became, and remains, a very Chinese American day of remembrance.

[updated 2024-4-14]

#Qing Ming#Tomb Sweeping Day#Thomas W. Chinn#Chinese funerals#Chinese cemeteries#Yuen Lee clam store#Lone Mountain Cemetery#San Francisco Chinatown#Dutch Flat#Hee Ching She#Ansel Adams#Laurel Hill Cemetery#Yerba Buena Cemetery#Jesse B. Cook

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

hi yes I don't shut up so here's my list of preorders I'm excited about

I Kissed Shara Wheeler - Casey Mcquiston (CM YA f/f with a bit of a mystery twist? YES PLEASE)

The Noh Family - Grace K Shim (this is being advertised as kdrama like and look I'm a sucker for "person finds out they're actually related to royal/rich family" books)

We Were Dreamers: An Immigrant Superhero Origin Story - Simu Liu (I love him!!!!)

Tokyo Dreaming - Emiko Jean (speaking of books where the mc finds out they're royal... this is a sequel to Tokyo Ever After where that PLUS bodyguard romance happens)

Yerba Buena - Nina LaCour (NL adult f/f book? INTO IT prepare for max emotions)

Valiant Ladies - Melissa Grey (As soon as I saw this I got musketeer vibes in a good way-- YA f/f best friends with swords in 17th century peru)

Epically Earnest - Molly Horan (YA retelling of the importance of being earnest, giving the queerness a Wilde play deserves I expect)

The Final Gambit - Jennifer Lynn Barnes (the last installment of the Inheritance Games aka Truly Devious meets Knives Out with less murder and more weird rich people family secrets and games)

Self-Made Boys: A Great Gatsby Remix - Anna-Marie McLemore (the trans retelling of Gatsby that we didn't know we needed but AMM did because they are a genius)

The Sunbearer Trials - Aiden Thomas (people are saying pjo meets hunger games and I was like eh until I realized it was by AT and will obv bring the amazing magicalness seen in Cemetery Boys)

Red, White, and Royal Blue collector's edition (look I have read my paperback like 6 times a hardback with bonus content is a good investment I have no shame)

The Ones We Burn - Rebecca Mix (YA witchy, queer, the cover is beautiful, enemies to lovers thing going on, honestly it sounds VERY cool and the author is a great Twitter follow)

I must have bookish followers right?? who wants to talk about your preorder lists what did you get from the b&n sale what are you looking forward to tell me the deets

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ordinarily I’d wait until I've finished a book to start blogging about it, but I’m only about 100 pages into Ada or Ardor, there’s already so much to say, and I don’t anticipate it being a short read.

I have a complicated relationship with Nabokov. I appreciate Pale Fire or Lolita as literature, they appeal to most of my aesthetic sensibilities, I’m very glad I read them, I plan to do it again, and I found them both, from start to finish, really viscerally unpleasant. Ada or Ardor isn’t like that. It’s unpleasant in places, but not claustrophobic the way his other novels sometimes are. There’s such a profound sense of world. Not that I’m entirely clear on how much of that world is actually in Van’s head or really what the fuck is even happening.

I’d say it’s the postmodern 19th-century SFF novel I didn’t know I wanted, but that’s a genre preference I was honestly pretty well aware of. I’m sure that when more things start to happen I will have more opinions on how they relate to science fiction genre theory.

Until the plot starts to materialize, I’m just in it for the language. When I’m reading German or Hebrew or Latin, the sound and texture and rhythm of the words have a stronger aesthetic effect than what it is they mean. It’s a property of not being fluent, and Nabokov is one of a very few authors who can do that to me in English. It’s strange to read about his regrets over having to write in English instead of Russian - I’m not sure a native speaker could have written this book. (I’m not sure how anyone could have written this book).

It’s something I’m struggling to articulate. Nabokov isn’t trying to communicate any kind of sensory experience, words matter in that they are words, not in that they point to things. The content is still there, but it’s connected to the text at a remove; everything is lighter, looser, more playful. It’s not that he’s not a very visual author, but he’s translating, not transcribing, real things (”real things”?) are represented as the auditory effect of all that accumulated specificity. The only passage I’ve both underlined and highlighted:

Natural history indeed! Unnatural history - because that precision of senses and sense must seem unpleasantly peculiar to peasants, and because the detail is all: The song of a Tuscan Firecrest or a Sitka Kinglet in a cemetery cypress; a minty whiff of Summer Savory or Yerba Buena on a coastal slope; the dancing flitter of a Holly Blue or an Echo Azure - combined with other birds, flowers, and butterflies: that has to be heard, smelled, and seen through the transparency of death and ardent beauty. And most difficult: beauty itself as perceived through the there and then. The males of the firefly (but now it’s really your turn, Van).

That’s all, the rest is commentary.

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“🎉🎉🎉 Happy birthday to our building: a 100-year-old beaux arts beauty! Learn more about our building’s beginnings as the original site of the Yerba Buena Cemetery and San Francisco’s Main Library, to the cultural gem it is today”

.

credit: @asianartmuseum

.

@cmonboardsf compiles the best things happening in San Francisco. Keep an eye on our website for more .

.

.

.

0 notes

Text

Body Found Under Home Was Child Buried 140 Years Ago

Body Found Under Home Was Child Buried 140 Years Ago

In this June 4, 2016 photo, the Knights of Columbus, Yerba Buena Lodge of San Francisco, stand guard as a casket, holding the body of a girl found in May 2016 and buried in San Francisco in 1876, is carried to her new grave at Greenlawn Memorial Park Cemetery in Colma, Calif. (Michael Macor) In this June 4, 2016 photo, the Knights of Columbus, Yerba Buena Lodge of San Francisco, stand guard as a…

View On WordPress

0 notes