#YOU are allowed to think otherwise. but others can view this as compelling storytelling and put that above their shipper goggle lens

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

the day the fandom realizes that chenford doesn't currently function within the confines of a healthy, communicative, adult relationship is the day i will know peace.

#like yes if the relationship you were talking about existed i'd be anti breakup too#but it doesn't! and those flaw-free characters you talk about don't exist on the show - they only exist in fic!#these are flawed messy and sometimes immature people with a vast number of communication issues#and a penchant for being the martyr (tim) and being the runner (lucy)#they're not automatically devoid of flaws once they're together. if anything their fear makes those flaws worse#their lack of communication and overt side-skirting of issues is prevalent from 512 to 521 without the rose coloured glasses filter#like step back from the pancakes and the 'dadford' and i promise you'll see two people with a myriad of interesting and complicated issues#and that people are allowed to think a fascinating way to handle this is to get them apart to build them stronger back together#YOU are allowed to think otherwise. but others can view this as compelling storytelling and put that above their shipper goggle lens#text

47 notes

·

View notes

Note

So, I don't think I've ever asked you this... what IS the whole point of the Spider-Sense? It really seems like something that only exists for writers to ignore or work around when they want to inject Legit Tension into a story.

I’ve thought about this power so much, but never with an eye to defend its right to exist, so I needed to think about this. The results could be more concise.

Ironically, given the question, I have to say its main purpose is to ramp up tension. But it’s also a highly variable multitool that a skilled creative team can use for...pretty much anything. It does everything the writer wants it to, while for its wielder always falls just short of doing enough.

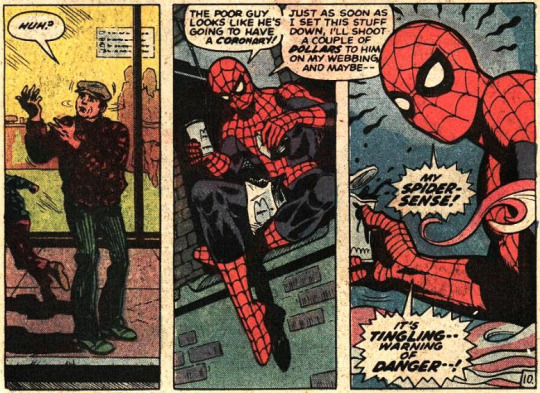

I went looking through my photos for a really generic, classic-looking example to use as an image to head this topic, but then I ran into the time Peter absolutely did not reimburse this man for his stolen McDonald’s, so have that instead.

A Scare Chord, But You Can Draw It

That one post that says the spider-sense is just super-anxiety isn’t, like, wrong. It’s a very anxious, dramatic storytelling tool originally designed for a very anxious, dramatic protagonist. I find it speaks to the overall tone of the franchise that some characters are functionally psychics, but with a psychic ability that only points out problems.

Spidey sense pinging? There’s danger, be stressed! Broken? Now the lead won’t even KNOW when there’s a problem, scary! Single character is immune to it? That’s an invisible knife in the dark oh my god what the fuck what the fU--

Like its counterpart in garden variety anxiety, the only time the spider-sense reduces tension is in the middle of a crisis. But in the wish fulfillmenty way that you want in an adventure story to justify exaggerated action sequences, the same way enhanced strength or durability does. Also like those, it would theoretically make someone much safer to have it, but it exists in the story to let your character navigate into and weather more dangerous situations.

For its basic role in a story, a danger sense is a snappy way to rile up both the reader and the protagonist that doesn’t offer much information beyond that it’s time to sit smart because shit is about to go down.

Spidey comic canon is all over the board in quality and genre, and it started needing to subvert its formulas before the creators got a handle on what those formulas even were, and basically no one has read anything approaching most of it at this point, so for consistent examples of a really bare bones use of this power in storytelling, I’d point to the property that’s done the best job yet of boiling down the mechanics of Spider-Man to their absolute most basic essentials for adaptation to a compelling monster of the week TV series.

Or as you probably know it, Danny Phantom. DON’T BOO, I’M RIGHT.

DP is Spider-Man with about 2/3 of the serial numbers filed off and no death (ironically), and Danny’s ghost sense is the most proof in the formula example of what the spidey sense is for: It’s a big sign held up for the viewer that says, “Something is wrong! Pay attention!” Effectively a visual scare chord. It’s about That Drama. And it works, which won it a consistent place in the show’s formula. We’re talking several times an episode here.

So why does it work?

It’s a little counterintuitive, but it’s strong storytelling to tell your audience that something bad is going to happen before it does. A vague, punchy spoiler transforms the ignorant calm before a conflict into a tense moment of anticipation. ...And it makes sure people don’t fail to absorb the beginning of said conflict because they weren’t prepared to shift gears when the scene did. Shock is a valuable tool, too, but treating it like a staple is how you burn out your audience instead of keeping them engaged. Not to go after an easy target, but you need to know how to manage your audience’s alarm if you don’t want to end up like Game of Thrones.

The limits of the spider-sense also keep you on your toes when handled by a smart writer. It tells Peter (everyone’s is a little different, so I’m going to cite the og) about threats to his person, but it doesn’t elaborate with any details when it’s not already obvious why, what kind, and from what. And it doesn’t warn him about anything else-- Which is a pretty critical gap when you zoom out and look at his hero career’s successes and failures and conclude that it’s definitely why he’s lived as long as he has acting the way he does, but was useless as he failed to save a string of people he’d have much rather had live on than him.

(Any long-running superhero mythos has these incidents, but with Peter they’re important to the core themes.)

And since this power is by plot for plot (or because it’s roughly agreed it only really blares about threats that check at least two boxes of being major, immediate, or physical), it always kicks in enough to register when the danger is bearing down...when it’s too late to actually do anything about it if “anything” is a more complex action than “dodge”.

Really? Not until the elevator doors started to open?

That Distinctive, Crunchy Spider Flavor

The spider-sense and its little pen squiggles go hand in hand with wallcrawling (and its unique and instantly identifiable associated body language) to make the Spider-Person powerset enduringly iconic and elevate characters with it from being generic mid-level super-bricks. Visually, but also in how it shapes the story.

I said it can share a narrative role with super strength. But when you end a fight and go home, super strength continues to make your character feel powerful, probably safer than they’d be otherwise, maybe dangerous.

The spider-sense just keeps blaring, “Something’s wrong! Something’s wrong! God, why aren’t you doing something about this!?”

Pretty morose thing to live with, for a safety net! Kind of a double edged sword you have there! Could be constantly being hyperattuned to problems would prime you for a negative outlook on life. Kind of seems like a power that would make it impossible for a moral person to take a day off, leading them into a beleaguered and resentful yet dutiful attitude about the whole superhero gig! Might build up to some of the core traits of this mythos, maybe! Might lead to a lot of fifteen minute retirement stories, or something. Might even be a built in ‘great responsibility’ alarm that gets you a main character who as a rule is not going to stop fighting until he physically cannot fight anymore.

Certainly not apropos of anything, just throwing this short lived barely-a-joke tagline up for fun.

One of my personal favorite things about stories with superpowers is keeping in mind how they cause the people who have them to act in unusual ways outside of fights, so when you tell me that these people have an entire extra sense that tells them when the gas in their house is leaking through a barely useful hot/cold warning system that never turns off, I’m like, eyes emojis, popcorn out, notebook open, listening intently, spectacles on, the whole deal.

It also contributes to Peter Parker’s personality in a way I really enjoy: It allows him to act like an irrational maniac. When you know exactly when a situation becomes dangerous and how much, normal levels of caution go out the window and absolutely nothing you do makes sense from an exterior standpoint anymore. That’s the good shit. I would like to see more exploration of how the non-Parker characters experiencing the world in this incredibly altered way bounce in response.

It’s also one of many tools in this franchise hauling the reader into relating more closely with the main character. The backbone of classic Spidey is probably being in on secrets only Peter and the reader know which completely reframe how one views the situation on the page. It’s just a big irony mine for the whole first decade. A convenient way to inform the reader and the lead that something is bad news that’s not perceivable to any other characters is youth-with-a-big-exciting-secret catnip.

Another point for tension, there, in that being aware of danger is not synonymous with being able to act on it. If there’s no visible reason for you to be acting strange, well...you’re just going to have to sit tight and sweat, aren’t you? Some gratuitous head wiggles never hurt when setting up that type of conflict.

Have I mentioned that they look cool? Simultaneously punchy and distinctive, with a respectable amount of leeway for artists to get creative with and still coming up with something easily recognizable? And pretty easy to intuit the meaning of even without the long-winded explanations common in the days when people wrote comics with the intent that someone could come in cold on any random issue and follow along okay, I think, although the mechanic has been deeply ingrained in popular culture for so long that I can’t really say for sure.

It was also useful back in the day when no artists drew the eyes on the Spider-Man mask as emoting and were conveying the lead’s expressions entirely through body language and panel composition. If you wiggle enough squiggles, you don’t need eyebrows.

Take This Handwave and Never Ask Me a Logistical Question Again

This ability patches plot holes faster than people can pick them open AND it can act as an excuse to get any plot rolling you can think of if paired with one meddling protagonist who doesn’t know how to mind their own business. Buy it now for only $19.99 (in four installments; that’s four installments of $19.99).

Why can a teenager win a six on one fight against other superhumans? Well, the spider-sense is the ultimate edge in combat, duh.

Why can Peter websling? Why doesn’t everyone websling? Well, the spider-sense is keeping him from eating flagpole when he violently flings himself across New York in a way neither man nor spider was ever meant to move.

How are we supposed to get him involved with the plot this week???? Well, that crate FELT dangerous, so he’s going to investigate it. Oh, dip, it was full of guns and radioactive snakes! Probably shouldn’t have opened that!

Yeah, okay, but why isn’t it fixing everything, then? Isn’t it supposed to be why Peter has never accidentally unmasked in front of somebody? ('Nother entry for this section, take a shot.) That’s crazy sensitive! How does he still have any problems!? Is everything bad that’s ever happened to characters with this powerset bad writing!? --Listen, I think as people with uncanny senses that can tell us whether we are in danger with accuracy that varies from incredible to approximate (I am talking about the five senses that most people have), we should all know better than to underestimate our ability to tune them out or interpret them wrong and fuck ourselves up anyway. I honestly find this part completely realistic.

*SLAPS ROOF OF SPIDER-SENSE* YOU CAN FIT SO MANY STORIES IN THIS THING

The spider-sense is a clean branch into...whatever. There is the exact right balance of structure and wishy-washiness to build off of. A sample selection of whatevers that have been built:

It’s sci-fi and spy gadgets when Peter builds technology that can interface with it.

It’s quasi-mystical when Kaine and Annie-May get stronger versions of it that give them literal psychic visions, or when you want to get mythological and start talking about all the spider-characters being part of a grand web of fate.

Kaine loses his and it becomes symbolic of a future newly unbound by constraints, entangled thematically with the improved physical health he picked up at the same time -- a loss presented as a gain.

Peter loses his and almost dies 782 times in one afternoon because that didn’t make the people he provoked when he had it stop trying to kill him, and also because he isn’t about to start “””taking the subway’’””’ “‘’“”to work”””’’” like some kind of loser who doesn’t get a heads up when he’s about to hit a pigeon at 50mph.

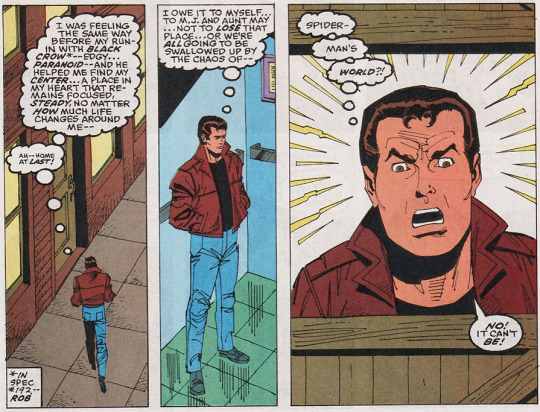

Peter’s starts tuning into his wife’s anxiety and it’s a tool in a relationship study.

It starts pinging whenever Peter’s near his boss who’s secretly been replaced by a shapeshifter and he IGNORES IT because his boss is enough of an asshole that that doesn’t strike him as weird; now it’s a comedy/irony tool.

Into the Spider-Verse made it this beautiful poetic thing connecting all the spider-heroes in the multiverse and stacked up a story on it about instant connection, loss, and incredibly unlikely strangers becoming a found family. It was also aesthetic as FUCK. Remember the scene where Miles just hears barely intelligible whispering that’s all lines people say later in the film and then his own voice very clearly says “look out” and then the room explodes?? Fuck!!!!

Venom becomes immune to it after hitchhiking to Earth in Peter’s bone juice and it makes him a unique threat while telling a more-homoerotic-than-I-assume-was-originally-intended story about violation and how close relationships can be dangerous when they go sour.

It doesn’t work on people you trust for maximum soap opera energy. Love the innate tragedy of this feature coming up.

IN CONCLUSION I don’t have much patience for writers who don’t take advantage of it, never mind feel they need to write around it.

#spiderman#peter parker#spiderverse#spidey#marvel#danny phantom#one day you'll see what i'm doing with it in the project i'm collabing on w/ my brother and then you'll all be sorry and hopefully impresse#mirrorfalls#asks answered#essays

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Thinking about this image and how much I feel this when it comes to Bionicle and my creation and consumption of transformative content in this fandom, especially when it comes as someone who prefers the more secondary heroic characters, the villains and the few neutral characters the series has over the main heroes (who I do like, just don’t have as big brainrot for).

OK let me explain.

So, lately I been thinking a lot about Greg’s writing style as well as how he engaged with the fandom. And one thing I have in particular paid attention to is the following: Bionicle is the type of story where plot is it’s driving force (alongside its worldbuilding) and Greg is the type of writer who writes characters in the service of the plot, rather than plot in service of the characters.

Now, I don’t think this writing style is inherently bad, and it works for Bionicle since as said, Bionicle is a plot-driven series where the big appealis uncovering the world and numerous webs of conflict and drama and discord. I’m not also saying that Bionicle doesn’t have compelling characters or that some of those characters don’t have emotionally compelling arcs. Bionicle is an action-figure focused toyline so of course the characters have to be fun/interesting/likeable and there are many characters whose arcs people have either enjoyed, liked their writing or resonated with such as Takua or Vakama for instance. I’m also not saying Greg is incapable of writing emotional moments either (I mean, everyone in this fandom cried when Matoro died soo.)

What I am trying to say is the following: 1) Bionicle is an action-fantasy-science fiction-war drama aimed at kids which main focus is telling a complex story in a complex universe. Despite that the characters are (relatively) simple in the grand scheme of things. 2) Greg has said at least on a few occasions he uses characters as tools in story, and uses characters whenever they need to appear in the story. For Greg a lot of the time it feels he uses characters for what they can do in the story rather than who they are. 3)Greg often said that he thinks about details only if “they’re important to the story”. This is true to characters and their emotional struggles as well. 4) The fans love to overthink and speculate stuff that Greg probably never thought of because it wasn’t important for him. 5) A lot of the time Bionicle characters (especially the non main hero ones) only have their emotional struggles implied or skirted from.

Because of Gregs writing style and the way he is more interested in exploring the world/plot rather than the characters emotional struggles, it feels that the characters sometimes feel..undercooked. That they aren’t allowed to go through their emotional struggles in a way that feels natural. Heck, at times the emotional struggles feel accidental rather than intentional on Greg’s front (see one of the reasons Nidhiki is my favorite character is because his characterization just has that “deep rooted self-haterd/haterd towards everything else issues” yet when asked about this Greg just went very “idk I guess he’s dead so doesn’t matter”).

And just, this is a thing I like about the Bionicle fandom because like, we can add emotional struggles and stuff there where it was implied. Fandoms in general (transformative fandom in particular) tends to often focus on characters above any other aspect of storytelling, and as such, we can analyze, headcanon and breathe life into characters in a canon that was more focused on plot and world like Bionicle. It does help that unlike a lot of plot/world-focused series (which tend to have rather shallow and generic casts), the characters in Bionicle actually do have a lot of potential to be explored and dissected, no matter how clearly you can see them not being the focus of the story. So just interesting characters who don’t get as much of emotional caharsis/focus as they deserve equals desire of wanting to write meta/headcanons/fic where those characters issues are addressed and touched on. Because unlike Greg, I (and other ppl in the fandom as well9 do care about stuff like this.

Of course there are exceptions (see Vakama for instance). In addition, not every character needs to have emotional struggles: one thing I really like about Lhikan for instance is that he was able to keep hisidealism despite everything that happened to him.

But yeah. This is just my few cnets as a very vocal villain liker who also likes emotional catharsis. Idk how ppl who like main toa teams feel about this so I would love to hear your thoughts on this subject and whether or not me liking villains/secondary characters colors my view on this subject. Again keep in mind that the writer of this meta had their favorite character basically been characterized as “just a selfish bastard” according to Greg despite the text arguably suggesting otherwise so I am biased a f.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Horror History of Werewolves

As far as horror icons are concerned, werewolves are among the oldest of all monsters. References to man-to-wolf transformations show up as early as the Epic of Gilgamesh, making them pretty much as old as storytelling itself. And, unlike many other movie monsters, werewolves trace their folkloric roots to a time when people truly believed in and feared these creatures.

But for a creature with such a storied past, the modern werewolf has quite the crisis of identity. Thanks to an absolute deluge of romance novels featuring sometimes-furry love interests, the contemporary idea of “werewolf” is decidedly de-fanged. So how did we get here? Where did they come from, where are they going, and can werewolves ever be terrifying again?

Werewolves in Folklore and Legend

Ancient Greece was full of werewolf stories. Herodotus wrote of a nomadic tribe from Scythia (part of modern-day Russia) who changed into wolves for a portion of the year. This was most likely a response to the Proto-Indo-European societies living in that region at the time -- a group whose warrior class would sometimes don animal pelts and were said to call on the spirit of animals to aid them in battle (the concept of the berserker has the same roots -- just bears rather than wolves).

In Arcadia, there was a local legend about King Lycaon, who was turned to a wolf as punishment for serving human meat to Zeus (exact details of the event vary between accounts, but cannibalism and crimes-against-the-gods are a common theme). Pliny the Elder wrote of werewolves as well, explaining that those who make a sacrifice to Zeus Lycaeus would be turned to wolves but could resume human form years later if they abstained from eating human meat in that time.

By the time we reach the Medieval period in Europe, werewolf stories were widespread and frequently associated with witchcraft. Lycanthropy could be either a curse laid upon someone or a transformation undergone by someone practicing witchcraft, but either way was bad news in the eyes of the church. For several centuries, witch-hunts would aggressively seek out anyone suspected of transforming into a wolf.

One particularly well-known werewolf trial was for Peter Stumpp in 1589. Stumpp, known as "The Werewolf of Bedburg," confessed to killing and eating fourteen children and two pregnant women while in the form of a wolf after donning a belt given to him by the Devil. Granted, this confession came on the tail-end of extensive public torture, so it may not be precisely reliable. His daughter and mistress were also executed in a public and brutal way during the same trial.

Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?

The thing you have to understand when studying folklore is that, for many centuries, wolves were the apex predator of Europe. While wolf attacks on humans have been exceedingly rare in North America, wolves in Europe have historically been much bolder -- or, at least, there are more numerous reports of man-eating wolves in those regions. Between 1362 and 1918, roughly 7,600 people were reportedly killed by wolves in France alone, which may have some bearing on the local werewolf tradition of the loup-garou.

For people living in rural areas, subsisting as farmers or hunters, wolves posed a genuine existential threat. Large, intelligent, utilizing teamwork and more than capable of outwitting the average human, wolves are a compelling villain. Which is probably why they show up so frequently in fairytales, from Little Red Riding Hood to Peter and the Wolf to The Three Little Pigs.

Early Werewolf Fiction

Vampires have Dracula and zombies have I Am Legend, but there really is no clear singular book to point to as the "First Great Werewolf Novel." Perhaps by the time the novel was really taking off as an artform, werewolves had lost some of their appeal. After all, widespread literacy and reading-for-pleasure went hand-in-hand with advancements in civilization. For city-dwellers in Victorian England, for example, the threat of a wolf eating you alive probably seemed quite remote.

Don't get me wrong -- there were some Gothic novels featuring werewolves, like Sutherland Menzies' Hugues, The Wer-Wolf, or G.W.M. Reynolds' Wagner the Wehr-Wolf, or even The Wolf Leader by Alexandre Dumas. But these are not books that have entered the popular conscience by any means. I doubt most people have ever heard of them, much less read them.

No -- I would argue that the closest thing we have, thematically, to a Great Werewolf Novel is in fact The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson. Written in 1886, the Gothic novella tells the story of a scientist who, wanting to engage in certain unnamed vices without detection, created a serum that would allow him to transform into another person. That alter-ego, Mr. Hyde, was selfish, violent, and ultimately uncontrollable -- and after taking over the body on its own terms and committing a murder or two, the only way to stop Hyde’s re-emergence was suicide.

Although not about werewolves, per se, Jekyll & Hyde touches on many themes that we'll see come up time and again in werewolf media up through the present day: toxic masculinity, the dual nature of man, leading a double life, and the ultimate tragedy of allowing one's base instincts/animal nature to run wild. Against a backdrop of Victorian sexual repression and a rapidly shifting concept of humanity's relationship to nature, it makes sense that these themes would resonate deeply (and find a new home in werewolf media).

It is also worth mentioning Guy Endore's The Werewolf of Paris, published in 1933. Set against the backdrop of the Franco-Prussian war and subsequent military battles, the book utilizes a werewolf as a plot device for exploring political turmoil. A #1 bestseller in its day, the book was a big influence on the sci-fi and mystery pulp scene of the 1940s and 50s, and is still considered one of the best werewolf novels of its ilk.

From Silver Bullets to Silver Screens

What werewolf representation lacks in novels, it makes up for in film. Werewolves have been a surprisingly enduring feature of film from its early days, due perhaps to just how much fun transformation sequences are to film. From camera tricks to makeup crews and animatronics design, werewolf movies create a lot of unique opportunities for special effects -- and for early film audiences especially (who were not yet jaded to movie magic), these on-screen metamorphoses must have elicited true awe.

The Wolf Man (1941) really kicked off the trend. Featuring Lon Chaney Jr. as the titular wolf-man, the film was cutting-edge for its time in the special effects department. The creature design is the most memorable thing about the film, which has an otherwise forgettable plot -- but it captured viewer attention enough to bring Chaney back many times over for sequels and Universal Monster mash-ups.

The Wolf Man and 1944's Cry of the Werewolf draw on that problematic Hollywood staple, "The Gypsy Curse(tm)" for their world-building. Fortunately, werewolf media would drift away from that trope pretty quickly; curses lost their appeal, but “bite as mode of transmission” would remain an essential part of werewolf mythos.

In 1957, I Was a Teenage Werewolf was released as a classic double-header drive-in flick that's nevertheless worth a watch for its parallels between werewolfism and male aggression (a theme we'll see come up again and again). Guy Endore's novel got the Hammer Film treatment for 1961's The Curse of the Werewolf, but it wasn't until the 1970s when werewolf media really exploded: The Beast Must Die, The Legend of the Wolf Woman, The Fury of the Wolfman, Scream of the Wolf, Werewolves on Wheels and many more besides.

Hmmm, werewolves exploding in popularity around the same time as women's liberation was dramatically redefining gender roles and threatening the cultural concept of masculinity? Nah, must be a coincidence.

The 1980s brought with it even more werewolf movies, including some of the best-known in the genre: The Howling (1981), Teen Wolf (1985), An American Werewolf in London (1981), and The Company of Wolves (1984). Differing widely in their tone and treatment of werewolf canon, the films would establish more of a spiderweb than a linear taxonomy.

That spilled over into the 1990s as well. The Howling franchise went deep, with at least seven films that I can think of. Wolf, a 1994 release starring Jack Nicholson is especially worth a watch for its themes of dark romantic horror.

By the 2000s, we get a proper grab-bag of werewolf options. There is of course the Underworld series, with its overwrought "vampires vs lycans" world-building. There's also Skin Walkers, which tries very hard to be Underworld (and fails miserably at even that low bar). But there's also Dog Soldiers and Ginger Snaps, arguably two of the finest werewolf movies of all time -- albeit in extremely different ways and for very different reasons.

Dog Soldiers is a straightforward monster movie pitting soldiers against ravenous werewolves. The wolves could just as easily have been subbed out with vampires or zombies -- there is nothing uniquely wolfish about them on a thematic level -- but the creature design is unique and the film itself is mastefully made and entertaining.

Ginger Snaps is the first werewolf movie I can think of that tackles lycanthropy from a female point of view. Although The Company of Wolves has a strong feminist angle, it is still very much a film about male sexuality and aggression. Ginger Snaps, on the other hand, likens werewolfism to female puberty -- a comparison that frankly makes a lot of sense.

The Werewolf as Sex Object

There are quite literally thousands of werewolf romance novels on the market, with more coming in each day. But the origins of this trend are a bit fuzzier to make out (no pun intended).

Everyone can mostly agree that Anne Rice’s Interview with a Vampire was the turning-point for sympathetic vampires -- and paranormal romance as a whole. But where do werewolves enter the mix? Possibly with Laurell K. Hamilton’s Anita Blake, Vampire Hunter books, which feature the titular character in a relationship with a werewolf (and some vampires, and were-leopards, and...many other things). With the first book released in 1993, the Anita Blake series seems to pre-date similar books in its ilk.

Blood and Chocolate (1997) by Annette Curtis Klause delivers a YA-focused version of the classic “I’m a werewolf in high school crushing on a mortal boy”; that same year, Buffy the Vampire Slayer hit the small screen, and although the primary focus was vampires, there is a main werewolf character (and romancing him around the challenges of his wolfishness is a big plot point for the characters involved). And Buffy, of course, paved the way for Twilight in 2005. From there, werewolves were poised to become a staple of the ever-more-popular urban fantasy/paranormal romance genre.

“Sexy werewolf” as a trope may have its roots in other traditions like the beastly bridegroom (eg, Beauty and the Beast) and the demon lover (eg, Labyrinth), which we can talk about another time. But there’s one other ingredient in this recipe that needs to be discussed. And, oh yes, we’re going there.

youtube

Alpha/Beta/Omegaverse

By now you might be familiar with the concept of the Omegaverse thanks to the illuminating Lindsay Ellis video on the topic (and the current ongoing lawsuit). If not, well, just watch the video. It’ll be easier than trying to explain it all. (Warning for NSFW topics).

But the tl;dr is that A/B/O or Omegaverse is a genre of (generally erotic) romance utilizing the classical understanding of wolf pack hierarchy. Never mind that science has long since disproven the stratification of authority in wolf packs; the popular conscious is still intrigued by the concept of a society where some people are powerful alphas and some people are timid omegas and that’s just The Way Things Are.

What’s interesting about the Omegaverse in regards to werewolf fiction is that, as near as I’ve been able to discover, it’s actually a case of convergent evolution. A/B/O as a genre seems to trace its roots to Star Trek fanfiction in the 1960s, where Kirk/Spock couplings popularized ideas like heat cycles. From there, the trope seems to weave its way through various fandoms, exploding in popularity in the Supernatural fandom.

What seems to have happened is that the confluence of A/B/O kink dynamics merging with urban fantasy werewolf social structure set off a popular niche for werewolf romance to truly thrive.

It’s important to remember that, throughout folklore, werewolves were not viewed as being part of werewolf societies. Werewolves were humans who achieved wolf form through a curse or witchcraft, causing them to transform into murderous monsters -- but there was no “werewolf pack,” and certainly no social hierarchy involving werewolf alphas exerting their dominance over weaker pack members. That element is a purely modern one rooted as much in our misunderstanding of wolf pack dynamics as in our very human desire for power hierarchies.

So Where Do We Go From Here?

I don’t think sexy werewolf stories are going anywhere anytime soon. But that doesn’t mean that there’s no room left in horror for werewolves to resume their monstrous roots.

Thematically, werewolves have done a lot of heavy lifting over the centuries. They hold up a mirror to humanity to represent our own animal nature. They embody themes of toxic masculinity, aggression, primal sexuality, and the struggle of the id and ego. Werewolf attack as sexual violence is an obvious but powerful metaphor for trauma, leaving the victim transformed. Werewolves as predators hiding in plain sight among civilization have never been more relevant than in our #MeToo moment of history.

Can werewolves still be frightening? Absolutely.

As long as human nature remains conflicted, there will always be room at the table for man-beasts and horrifying transfigurations.

--

This blog topic was chosen by my Patreon supporters, who got to see it one week before it went live. If you too would enjoy early access to my blog posts, want to vote for next month’s topic, or just want to support the work I do, come be a patron at https://www.patreon.com/tlbodine

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deciding on a POV

There are many ways to tell a story, and each one comes with a benefit or a downside. Still, I figured it’s worth going over the different ways each can be effective.

First Person

Reliable Narrator: A story with a reliable First Person narrator is one of the most common narrative styles. What this means is that the reader can trust what the narrator is telling them is the truth as it actually happened. Think Percy Jackson in the Percy Jackson and the Olympians Series.The reliable narrator is far more common than the unreliable variety. The benefit of this narrative style is that it mirrors how we tell stories verbally. If something happened to me, and I tell my friend what happened, I am going to use First Person narration to explain the events that transpired. Thus, this can feel like the most organic option. It also allows for total access to the POV character’s thoughts, allowing readers to see how they reached a conclusion, or why they’re acting a certain way. However, this can come with the problem of not being able to get inside the head of anyone except for the narrator. Now, while it’s standard for the First Person narrator to be the main character, it isn’t always the case. If the narrator is some sort of omniscient, bystander, or divine presence, whether they interact with the characters or not, it technically falls under First Person if they voice their opinion using I statements. The figure of Death in The Book Thief is a good example of this, as Death uses I and me in the narrative of the story. Because the story is set in Germany during World War II, the narrator of Death sees the protagonist, Liesel, frequently, and thus we’re able to get a narrator who is observing a protagonist from outside of her immediate story.

Unreliable Narrator: An Unreliable narrator is going to be the exact opposite. They tell the story, but take their story with a grain of salt. Whether their perception of reality is distorted, they’re using metaphors and symbolic imagery to tell the story, or they’re telling the story from a very narrow viewpoint, the unreliable narrator can be a good choice to get the reader to engage with the story and think critically about the work. Rugrats is a good example of this type of storytelling, as the main characters are babies, and therefore often mistake things for something else, making them unreliable narrators. This type works well if you want to tell a more abstract story. For instance, an entire story is about a boy chasing after a red balloon, but that red balloon itself represents accepting his mother’s death. Suddenly everything experienced becomes unreliable, leaving the reader wondering if the foes he defeated or the desert he crossed was literal, and he went on an actual journey to come to terms with his mother’s death, or was everything figurative, and the journey was more symbolic and allegorical? An unreliable narrator can play with these questions, blur the lines between reality and fiction, and leave their readers asking questions.

Third Person

Omniscient: Lemony Snicket is a perfect example of a great omniscient narrator. Mr. Snicket knows everything about every character, knows what’s going to happen before it happens, and comments on everything. Lemony Snicket himself is not a character in the story. Rather he recounts the story much like the First Person style, but from an outside perspective. Instead of being part of the story, Lemony Snicket is telling us about the Baudelaire children through the lens of the all-knowing and opinionated narrator. It’s not entirely uncommon for this type of narrator to be some supernatural force, a wise old sage, or someone who lived through an experience recounting the tale many years later. In fact it could be rather fun to play with this last one, having the story almost be told like a myth or legend, but having the narrator constantly side track to discuss how historians know and gathered the information for this story, only to reveal the narrator isn’t some omniscient being, but just a docent in a museum giving a tour and explaining an old myth to the patrons.

Limited: With a Limited POV, the reader learns things as the narrator does. Even though the narrator is the one telling the story, their information is only up to date with whatever is currently happening on the page. This and First Person are the two POV types most likely to appear in a mystery novel, or any novel where a mystery or unanswered questions drives the plot. Harry Potter is a series written in Limited Third Person. The story follows Harry, and the reader only learns information as Harry does. And every year, Harry is faced with the recurring mystery element of figuring out what’s going on, and stopping whatever their plan was. However, because the narrator only knows what the protagonist knows, this can allow you to play around with giving the narrator a personality, and having them comment or react to things as they happen, perhaps even mirroring the way you hope the readers are responding.

Objective: Think of Objective Point of View as watching a tv show. Anyone who’s into shipping has to read into objective romantic coding. Two characters held eye contact for five seconds? You the reader have to interpret that as you will. Objective is strangely both the most human and the most robotic point of view. At its most human, Objective treats the narration like a normal person. They can’t read the thoughts of other characters, they don’t know more than the hero or reader, and you’re effectively just a bystander in the crowd watching things happen with no context clues about what’s happening inside a character’s head. On the opposite end, it can also be the most robotic because it is the most lacking in human connection, as it leaves the reader detached from the characters themselves. However, a liberating or perhaps crippling aspect of this POV style is that it frees the author of show don’t tell because this type of POV can’t enter anyone’s minds or go on a rant about a character’s feelings about someone else. You just have to take what you get at face value and all information has to be conveyed through your characters and story, whether directly through dialogue, or subtly through background details.

Switching POVs

Most stories tend to stick with a single narrator. Stories can be complicated when one person is giving an opinion, but when multiple people are talking, it can be hard to find a voice and plot for each of them. And if you’re planning on writing a series, you may run into the problem of some characters having meatier plots than others. It’s for this reason that when it comes to watching Game of Thrones, I always groan internally whenver the story cuts back to Bran or Jon at the Wall. It’s a scene or two of people standing around being cold or talking about being cold and something something three-eyed raven and then we finally get back to the part I’m more interested in: the political games of manipulation and intrigue. But that’s also a strength of changing POVs. With something like Game of Thrones, you might not necessarily like every storyline happening, but you’re more likely to enjoy one. In a sense, Game of Thrones is like 11 novels stitched together, and because each is so different, you’re more likely to find something in the series that speaks to you. Conversely, when there’s multiple POVs experiencing the same thing, such as with the Heroes of Olympus series, having shifting POVs can be a good way of exploring each character. In The Lost Hero, Piper knows more about the giant waiting to fight them than either Jason or Leo, and because we have shifting POVs, we the reader get access to this otherwise Limited Third Person information from the character who already knows it, thus building dramatic tension of when the others will find out. Another benefit to this is giving unique encounters to the characters. Percy has already met Aphrodite in the past, but through Piper, Aphrodite’s daughter, we’re able to see a different side of this goddess, the goddess as a mother to someone else. This could also manifest in differing opinions of the same things. This is also part of why it works so well in Game of Thrones. Game of Thrones is a civil war story with multiple sides all vying for the same end goal. Because there are so many sides and players in the game, having so many different points of view is valueable to the story being told. If Eddard Stark was the sole protagonist, the only thing that we would know is whatever he knows. Everything Danny is doing across the narrow sea would need to be told to Ned for it to matter. And the same with Jon at the Wall. And if Jon or Danny was the sole narrator, the reader would miss out on everything happening in King’s Landing because neither Danny nor Jon are connected to that part of the plot. An entire element to the story is lost when a major POV character is dropped, which goes to show how strong George RR Martin’s writing really is. Something I like doing with multiple POVs is describing the same character in two different ways from two characters who would see them in a drastically different way. One description might paint a character as dark, alluring, and attractive, while another person might describe them as a rat-faced shifty-eyed snake that stinks of booze and dead fish. It’s the same character, but two different people see that character in entirely different ways. However, this also comes with a major backlash. It can be an absolute nightmare juggling not only so many plots, but trying to make them fit together nicely. You’ll notice this a lot with shows that emphasize drama and interconnecting storylines. They’ll be really strong in their earlier seasons, then peter out once they’ve hit the creative brick wall. It happened to Once Upon a Time and to a lesser extent, Glee. Both shows had tightly knit and compelling drama in season 1, but by season 4, both shows felt like they were just going through the motions and had lost the edge that made them interesting. Even with something as well-written as Game of Thrones, it’s still possible to have someone’s story be weaker than everyone else’s. Arya Stark for instance spent the first couple of seasons focused on learning to sword fighting, then once the Hound died, she went to Braavos, but it always kind of felt more like a detour than really what Arya’s story was supposed to be about. She was a little girl out for vengeance, she went to Braavos for a season or two, didn’t really learn much, and then she came back to Westeros and pretty much went right back to exactly who she was before going to Braavos. Now granted, I’m going by the TV show, but it always felt to me at least that Arya’s vacation in Braavos was just kind of George not knowing what to do with her as he built up to the big climactic battle. So if you’re going to use shifting POVs, it’s important to weigh the pros and the cons carefully.

#writing#writing tips#writing advice#pov#writer problems#writing your book#do it write#points of view#point of view

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

FEATURE: Why The Early Pokémon Anime Was So Important To Its Audience

The '90s was a big decade for anime. Iconic series like Neon Genesis Evangelion and Cowboy Bebop were born, shows that are still presented as the gold standard of what the medium can achieve. Studio Ghibli continued their string of soon-to-be classics, helping to cement Hayao Miyazaki into a globally-recognized “auteur” status, a title usually reserved for the creators of live-action fare. Meanwhile, Dragon Ball Z, Gundam Wing, and others made their debut on the programming block Toonami, effectively introducing anime to an entire generation of Americans who may have otherwise never been exposed to it.

But what about the importance of Pokémon? That was pretty big, too, right?

Obviously, the status of the Pokémon anime as it relates to Pokémon as a whole is clear. There has perhaps never been a franchise with more coherent brand synergy, none better at directing traffic so fans of one aspect could be easily guided to another. Aided by an almost supernaturally compelling catchphrase “Gotta catch ‘em all!,” the uncertain development and angst surrounding the first set of titles in the core game series Red and Blue were quickly left in the rearview mirror. Pokémon is seemingly an undefeatable pop culture hydra with the anime serving as one of its many heads.

So how does Pokémon fit in the grand scheme of anime and what it can give to us? Because with all of that in mind, it’s hard not to look at it with a kind of cynicism, viewing it less as a fictional series with all the pros and cons that come with it, and more as an advertisement for itself and other parts of the franchise that has lasted over 20 years. However, I believe the Pokémon anime can be, depending on the specific section, very good at times. And though the explosion of “Pokemania,” as it was dubbed when the franchise landed in the United States, seemed to render it as an extended commercial urging kids to get their parents to buy them a Game Boy as soon as the "PokeRap" finished, I think the early parts of the series are particularly strong.

Because while the anime has formed a kind of cyclical pattern in its storytelling, one that allows newcomers to easily latch onto the series whenever they happen to discover it, I think the portions set in Kanto and Johto are extremely cool to examine. The space from the first time Ash Ketchum wakes up too late to grab one of the three “starter” Pokémon from Professor Oak to the time he says goodbye to Misty and Brock at the crossroads following the Silver Conference contains a really touching narrative. One about growing up and learning to rely on others and then, eventually, learning to rely on yourself.

When we first meet Ash, he can barely keep things together. He’s desperate to be a Pokémon Master, but clueless when it comes to most of the techniques involved in actually doing that. He’s stubborn, but his confidence often reveals itself to be brittle bravado, a ten-year-old puffing his chest out only to be deflated when overtaken by an obstacle. His travel partners, Misty and Brock (and Tracey Sketchit for a little while,) obviously adore him, but their greatest shared trait is likely patience. Ash has a lot of learning to do.

This learning is usually slow and painstaking. Critics of the series are often quick to point out that Ash rarely wins his gym battles outright, something that’s a requirement to progress in the games the series is based on. Thus, more important than a solid KO is the lesson learned due to the battle, often something centered around taking care of your Pokémon, yourself, and other people. The “monster of the week” structure usually has Ash learning these lessons again and again, like a child that needs to be politely reprimanded until they fall out of a bad habit.

As the series moves from Kanto to the Johto region, Ash gains legitimate wins with higher frequency, gathering experience while his style remains eager, clumsy, and definitively Ash. His rivalry with Gary Oak — one initially informed by Ash’s seeming inadequacy and Gary’s loud, yet often precise assurance — evens out. At the end of the Indigo League in the Kanto region, Ash finally gets to battle Gary and loses. Then, in the Johto League tournament, Ash defeats Gary and the two make amends thanks to Ash’s defeat of his bully and Gary’s newfound serenity. It’s a nice payoff to their relationship, and Gary’s change of heart reflects the themes of personal growth found in the Original Series.

Meanwhile, Ash’s personal growth often comes with much more heartache. In “Bye Bye Butterfree,” he bids farewell to his first-ever caught monster because it would be happier with its own kind. A few episodes later, in “Pikachu’s Goodbye,” he seems all too ready to let Pikachu live with a pack of the little yellow critters, likely because his experience with Butterfree indicated that it was the right thing to do. Of course, Pikachu comes back to him, because he’s Ash’s ride or die.

Another relationship Ash learns from is the one with Charizard. Evolved from an abandoned and emotionally distraught Charmander, Charizard is rebellious to the extent that it causes Ash’s Indigo League loss, not because it gets knocked out but because it just doesn’t feel like fighting anymore. What follows is one of the most disheartening scenes in the series, with Ash shouting in anger and sadness at his Charizard to continue while Charizard just doesn’t respect his trainer enough to stand up. Though they eventually gain a sense of mutual reverence, their partnership is marked by this uncertainty.

And finally, the ending, which sees Ash, Misty, and Brock go their separate ways, recalls one of the franchise’s most resonant homages, that of the '80s film Stand By Me. Referenced in the opening moments of the first game, the movie about setting off on your own adventure as a youth and learning where nostalgia ends and the harshness of growing up begins mirrors the ethos of the franchise constantly. At the end of that film, the characters depart one another and the main protagonist muses to himself, “I never had any friends later on like the ones I had when I was twelve. Jesus, does anyone?”

You can get the same feeling from the affirmations of the importance of their friendship Ash, Brock, and Misty make when they head off on their own (though Brock quickly re-joins Ash in the next season of the anime). It’s here that Pokémon displays why it deserves its place among the notable anime of the '90s, not because of its massive marketing push (though that certainly helped its popularity) and not because of how it retold the story of the games (which, as adaptations go, is pretty hit or miss).

.

Instead, it’s a story about growing up. By the end of Ash’s time in Johto, it becomes clear that strength was never the objective, that the point of the whole affair was not Ash becoming a "Master." It was about teaching Ash enough so that when the time came for him to go out on his own, he could. And though he finds new companions in the regions to come pretty quickly, the impact of this is not diminished. If you began watching the show when it first appeared in America in 1998, you likely grew up with Ash to an extent, and you likely experienced some major life events during that time, whether it was going to a new school or facing some kind of family change or attempting to achieve some new, grand goal.

Ash and the Pokémon anime’s message was that you could do it. That the trials you’d experienced and the lessons you’d learned and the relationships you’d made had prepared you for it. And that while the future seems scary and unknowable, it isn’t insurmountable. Pokémon teaches you that you’ll be okay. That sounds pretty important to me.

Daniel Dockery is a Senior Staff Writer for Crunchyroll. Follow him on Twitter!

Do you love writing? Do you love anime? If you have an idea for a features story, pitch it to Crunchyroll Features!

By: Daniel Dockery

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

My biggest pro-tip: Fiction is NEVER Reality.

If I could give one and only one pro-tip for writing that so very many people, including people who are otherwise excellent storytellers, just don’t get it’s to remember that Fiction is NEVER Reality.

I have never seen so consistent a sign of a piece of fiction that isn’t going to work as the claims, “But that’s how it really happened,” or, “But that’s how it would really happen.”

To the point that the one few times back in grad school where I was writing something BASED on a real event, and people really wanted to know where I got such a compelling moment I was extremely reluctant to share. And the second I did, my lecturer turned on me, warning me that real events usually don’t work and usually aren’t the best way to do the action in a story even when they do work. And I was like, yeah, that’s why I didn’t want to tell you.

Which should not be mistaken for a contradiction.

I am not saying this belief that Fiction is NEVER Reality is something imposed on me by my teachers. I got to this one on my own. Though I think there was plenty of implication from my teachers that such a thing was the case, that lecturer was actually the first teacher I ever had to specifically say that clearly tome. I will eternally maintain that whatever works in specific, works. That trumps any general truth about writing. Same the other way around. You can follow the “rules” to the letter and still get crap because they don’t work for your specific piece. Every writing “rule” that may exist, exists for a reason. So long as you fulfill that reasoning, you don’t have to follow the “rules.” So long as the reasons for that “rule” don’t apply to your specific piece, it will hurt the piece to apply it. And, that’s the same thing as Fiction is NEVER Reality.

I can successfully write “real” events, well enough to get a bunch of very excellent writers, including my lecturer who wrote a lot for the BBC, very excited because I get that SEEMING real and BEING real are different. SEEMING real is the goal. BEING real tends to kill the seeming of reality. Because a rule in the real world is a rule. Drop a ball and it will accelerate toward the surface of the Earth at 9.8 meters per second squared. That is reality. Not every choice makes sense. The inexplicable happens every day. People just lie because... who knows... they’re liars. The world doesn’t make sense except in a very local or very abstract or very scientific way. And that’s fundamentally not what a story is.

A story’s job is to convince you it is real. But we’re used to living in that extreme local or deep abstract. Which means all the middle world incomprehensibility just doesn’t land right with most people. So, following the rules that are real rules, that things just happen, that is wide and incomprehensible, shuts people down the same as if you try to tell them really weird stuff in real life. A story SEEMS real by limiting itself to that personal level, even - or most especially - when it is not being written about that personal level.

Pardon me while I sidestep into my philosophy of art for a brief moment, it is applicable. There are a lot of opinions about art, how art works, and what art does. And I should be clear that my opinion is NOT the majority opinion.

The philosophy that i am an adherent to, and all the above is a recursive part of why, is that art happens as an act of communication between Artist and Audience, with the Medium of the Art as a conduit between. For writing in specific, that means my philosophy is that ART is the act of me, the Primary Author, taking an image I have in my head and giving you, the Reader, the basics of that story through the Medium of a Book, so that you, as a Secondary Author can build the full story up in your own head. I don’t have the totality of the Art. You don’t have the totality of the Art. The Book is simply the container for us to pass the communication between us. The Art only exists in that communication and interplay between us. It requires all three parts. Otherwise it doesn’t occur. I can make up a million stories in my head, I do, and if I don’t tell them to you, I don’t believe that is Art, I believe that is play. And the same for you. It has to pass between two people or more, allowing room for interpretation to be Art.

Which I mention because it informs why the personal point of view reigns supreme for story. Because in order for a story to occur, it has to get inside a person’s head and operate there. The Audience can only interact, truly, with a piece of Art as it sits inside their own understanding. So as you step away from a PERSONAL level of understanding on the part of the audience, you are stepping away from what they will believe, understand, and care about. We, as writers, are always limited by an “I” that we cannot control. Just manipulate.

To some degree, it is our job as writers to build the scaffolding for the readers to climb out of that “I” into a new and wider world. That is inevitable. But the basic logic of that as the beginning is inescapable. Everything starts as “I.” That’s why first person is so powerful and so natural as a starting place for new writers. Because it plays to that “I.” “I” am reading about a person A, who has to do B, but C is in the way. And while things will build to a richness where it will appear that A, B, and C will exist beyond their life in the book, that “I” will never absent itself. Which is why readers get mad when authors do things with characters and their world that don’t fit with the conceptions and rules that “I” have built up. Because we, in our personal lives maintain a structure of personal order. Violate that structure and “I” will rebel.

The real world violates it constantly. CONSTANTLY. There is no escape. We never know for sure what the other people in our lives will do. We never know precisely what the weather will do. There’s not a hope in hell of knowing what our leadership, far away, and foreign nations will do. But we hate that. We have to live with it but we hate it. So, we invent a narrative. We create for ourselves a line of reasoning to explain the unreasonable. Our parents yelled at us even though we didn’t do anything because they had a rough day at work. You know, that Allison is always giving them a hard time. “I” bet that was it. “I” bet Allison really laid into my parent and threatened to fire them for not getting the Bulletin Board Project done and even threatened to fire them, when all they really wanted was to get in, get it over with, and get us all to Carrow Beach for a relaxing weekend but now they have to work instead and they feel bad and then feel guilty and “I” am not helping so “I” better help and maybe if “I” can get some dinner on the table they would have more time and energy. Etc.

We’re playing with that as writers. Everything happens, eventually, for a reason. Everything, eventually, has a clear architecture of order - though it is usually emotional rather than factual. Because if a writer builds toward that SEEMING of reality, we can rely on the reader to take it and run with it and build out from that logic because that’s what they would do anyway. Try to make it literally real and you’re fighting against the architecture you’re trying to use. It’s like trying to make boat out of building. You might be able to. But it’s not taking advantage of how things are.

So whenever you are trying to deal with REAL. Think about it from the point of view of “I”. Not what really happened but what “I” would come around to telling “myself” happened. You are recreating the MODEL of the real world you carry around in your brain, well enough that someone else can use that model to reconstruct that interpreted world.

This is my biggest number one thing because it is the only thing that dictates how everything else works. Why does a story have to be interesting? Because “I” don’t have the patience to read boring things. If “I” don’t care, “I” won’t read. Why does a story have to be clear? Because “I” am not directly experiencing any of it, there is no real world for “me” to see, just the model that has been given to “me.” The only way “I” know what is happening is if “I” am shown it. Why doesn’t the 100% Real world look like the world as “I” experience it? Because we all live in the matrix, we’re a brain in a walking, talking, feeling jar, and neither brain in the jar nor jar that is the body experiences anything without talking to each other and every bit of communication allows for miscommunication. So the world of every “I” is slightly different. So the most important, fundamental bits of a story have to be built. WHY something happens. WHO someone is. HOW they go about getting what they want. These things have to work internally to the story.

You can’t make something more REAL. What real? Whose real? Instead you make things seem more real by focusing on the emotional logic of an “I.” I am disenchanted with the world, so my fictional world becomes more gray to communicate my disaffection. I am frightened, so descriptions become more ominous to communicate my discomfort. I am happy so the party I am writing about is a description of joy safe in the harbor before the storm that is coming. A stalker doesn’t jump from the sidewalk to the second floor balcony (the first ‘but it really happened’ I ever heard) instead they are just there in the apartment to communicate the terror of that, someone in the room, where there shouldn’t be anyone, and when they flee out the window and you’re frozen in fear a full beat after they’ve disappeared, heart hammering, because you know, you KNOW, they’re still there, it’s two stories up, but you make yourself grab your keys in your fist and shuffle to the fluttering shades, wishing you could hold the noise of your shoes on the carpet like you’re holding your breath, and rip them back, taking two blind punches to try and drive him back, keep him from touching your skin, grabbing your wrist in a death lock, and then... you don’t know what and you don’t want to know so you punch like somehow God will guide the keys into his eyes, but the balcony is empty, you’re punching empty air, there’s no one at all, nothing you can see, like a ghost, who doesn’t care at all that there was nowhere to go, that you can’t vanish into nothing, that the door was locked, that there is such a thing as walls to keep you safe.

There’s nothing REAL about that. But that’s an “I” thinking, experiencing, an architecture is there: that the stalker is a monster and will obey monster rules. Later, yes, there can be an explanation about how he is a champion ex pole vaulter and literally can leap up and down from the ground to the second story. But by the time we learn that, those are just facts defining the monster’s powers. We already know HOW he did it: he’s a monster. It doesn’t matter that it is literary fiction and there are no fantasy or science fiction elements. It’s the rules “I” apply. How “I” think about it all. There are tons of ways to do this. It doesn’t particularly matter. There’s no right answer. But the way it really happened that no one believes of that you have to pause the story and justify, is one of the wrong answers. Because if the reader has to explain it all to themselves, then they aren’t working on the writer’s story anymore, they’re working on their own. Which is why it tends to throw people out of a tale.

Real is for Non-Fiction, and even then there’s an art.

Fiction, no matter how much it is based on a real thing, has to build up its own world and own logic. Realness either doesn’t apply or works against the model you are trying to create which means you’re working against your reader. Because fundamentally, Story is about A leads to Z. While reality cannot be predicted like that, only recorded, and even then can only move in a straight line from A to Z with labyrinthine explanations and diversions to accommodate the sheer amount of reasoning necessary to explain how A could get to Z in a clear path. The best you can do is to do the large scale abstract. You’ll see that a lot in movie prologue voice overs. “No one would have expected X, to win the election that year, but then there was a war and a plague and the language started to change, and when he won by a landslide, things changed even more.” That’s the abstract. Not the real. The ruleset that “I” carry around that says when things get bad, we turn totalitarian. And it happens quick. That’s not reality either. That’s a scripted narrative. We, culturally believe that. And that’s where we get tropes coming into it. Those are the abstract truths we, as a culture, trust, having no clue how valid it is for Reality itself. But it doesn’t matter. It’s a tautology. So it goes.

And I think I have gone on long enough. It’s just getting too REAL for me at this point :p

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aw man, I’m feeling sentimental for a fully unrelated reason so I wanted to take this moment to say that I really love Friends at the Table and it has been a comfort to me during some dull and sad parts of my life, and also remained there for me after I shed a lot of that dullness and sadness. I still find great charm in the show even as Austin and the players’ storytelling interests have, with time, diverged from mine, and for every choice that distances me there are more to woo me back... I used to feel FATT’s best moments were the ones that came like bolts from the blue: strange, gorgeous, fully-formed scenes and transformed ideas. But there are also themes, especially in Twilight Mirage and late-season Hieron, that struggle hard to get underway, gaining momentum creakingly after a hundred hours of nothing... I like that style of surprise too; it’s nice when against all odds a story earns your patience. “Stockholm Surprise.”

...I mean, I still think Spring in Hieron is pretty bad. But I liked the epilogue, and it made me less regretful about having listened to the rest of the season. Mainly I liked the climax and the Understanding, and I especially liked, and wish they had kept, the original name of the Six, which seemed to best capture the most important and most underwritten of Hieron’s throughlines---that the horror of divinity is the horror of unilateral action, and that there’s no categorical difference between mortals acting secretly and destructively to serve “the public good” and gods doing the same. So the Six from the Last University mirror the Six from Marielda and the original pantheon of gods, complete with numbering chicanery. “Utilitarianism is wrong because it’s a fundamentally paternalistic, tyrannical dream that inflexibly robs individuals of their right to self-determination and discovery; it is so corrosively wrong that you are not excused in using utilitarian methods to fight a greater or more catastrophic fiat,” is a surprisingly rare message to find in genre fiction, which tends more toward “Utilitarianism is wrong... oh shit, look at all those people who died, though. Kind of makes you think.” That’s not to say that the above view of utilitarianism is co-signed by yours truly, but it was nevertheless refreshing to find it so clearly articulated and pressed on by the story, even to the point of the absurd “and so...?” stalemate to which Hieron devolves. And so, nothing.

It made me think about how sad I am about Samol, as a character, and as prime wellspring of the trauma and abusive love that characterized his whole family; I find his narrative shadow really compelling in retrospect, but his decision to save Samot’s life without Samot’s consent---kind of the ultimate reconfiguration and evocative even of Samol’s own birth from the nothing---should have been explicitly linked to Samot’s meltdown and actions in the finale. Also to Adelaide’s thinking around Adularia. Because Samol’s death is a refusal to change that he offers as the nearest thing to changing: he sees the harm he’s caused, regrets it, but even the gift of freedom for his children has to be given against their will. As a human narrative, it’s incredibly dark, and as a godly one it touches me in its unapologetic apartness. His ability to care and empathize with people never allows him to act as a person, with a person’s responsibility to others; alone of the gods, he really seems to have no choice but to do as he sees fit, beyond reproach or challenge, because no one can challenge him and to pretend otherwise would be a new way of imposing his will. Nor can he remove himself from the world he is. Which is like the truest parent conundrum, haha. ... ... But ... he nonetheless is written, played, and felt as a person, just a person beyond others’ reach. Which I know I’ve mentioned before as my favorite early Hieron theme and, well, here it is again, in the last place I expected, even if the season really buries it. So. I’m sad. End of post.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Predictable” Is Not A Four-Letter Word

Well, looks like it’s that time again. That’s right: it’s time to talk about our good friend, Subverted Expectations™.(WARNING: Game of Thrones spoilers below the jump)

Hey, who’s super excited for the upcoming Benioff and Weiss Star Wars trilogy now?

I’m alluding, of course, to the latest episode of HBO’s Game of Thrones, in which, after an 8-season-long journey learning to own her own power, master her fate, lead armies, free slaves, and reclaim her family’s place on the Iron Throne, Daenerys Targaryen evidently got just a wee bit too much girl power and decided to become…bad? I guess? Boy, who could have foretold such a stunning subversion of expectations?

(I mean, a woman gaining power, being gradually resented by the men around her for her ascent, and eventually being viewed as a megalomaniacal villainess who needs to be taken down a peg is kind of the opposite of a subversion, it’s actually pretty much what happens to most women in power, fictional, or non-fictional, but I digress)

Fan response, needless to say, has been…mixed. Generally, folks seem to be unhappy with this course of events, given that, aside from some allusions to “Targaryen Madness” throughout the series, the buildup to Dany’s heel turn has been widely seen as rushed and somewhat arbitrary. True, she’s suffered a lot in the past few episodes, but the series has also put quite a lot of effort into making Dany a sympathetic character. Complicated, yes, and flawed, as most GoT protagonists are, but still heroic and generally good. Even as a conqueror, she holds her armies to a code of conduct, shows sympathy to the downtrodden, and overall seems to want to be a good, ethical ruler even after she’s taken the Iron Throne. So, uh….what gives?

Those of us who were Star Wars fans during the release and aftermath of The Last Jedi will recognize this feeling all too well. And, much like with TLJ, the backlash itself spawned a backlash. “Actually,” declared the internet masses, “It’s good that Rian Johnson subverted our expectations. To follow through on what Abrams set up would have been obvious and boring. The whole point of storytelling is to be unexpected!” But if this is the case, why did so many people walk away from TLJ, or this past episode of GoT, feeling so unsatisfied? And why, for god’s sake, do we find ourselves constantly having this argument any time a new piece of media comes to an end?

The internet certainly provides many examples of the attitude that objection to an incongruous shock ending is somehow weak, entitled, emotional, and juvenile. There’s a sense that true fans of a franchise are tough enough to absorb an unsatisfying ending, that they actually find satisfaction from the dissatisfaction, and that to want an ending that ties up loose ends and closes character arcs (dare I say, even happily, at times) is to want one’s hand held, or to be incapable of handling nuance or bittersweetness. “Life isn’t always happy!” the internet masses cry. “Life doesn’t always make sense! Life is disappointing too! Deal with it!” But stories aren’t vegetables we’re supposed to choke down before we can leave the dinner table. The purpose of storytelling, for adults, at least, is not just to condescendingly remind the viewer that bad things happen sometimes, and force them to suck it up. Which, of course, isn’t to say that all endings have to be neat and happy, either–there are stories with dark endings that are deeply satisfying (Breaking Bad) and ones with happy endings that are deeply unsatisfying (How I Met Your Mother). There are even stories with subtle, unclear endings that still feel logical and satisfying to many viewers, albeit not all. The ending of The Sopranos, for instance was famously controversial for its ambiguity, but even this ending was tied to themes and concepts planted earlier in the series, and several perfectly cogent arguments have been written to explain this quite persuasively.

But what satisfying endings tend to have in common, that unsatisfying ones don’t, is a feeling of appropriateness and completeness. Most fans who hated the finale of How I Met Your Mother did so not because they resented that it was “happy,” but because they felt it was a 180-degree turn from the arcs of all the characters and storylines up until the last few minutes of the last episode. Conversely, people didn’t love Breaking Bad’s ending because it was “difficult” or “dark,” they loved it because it was a believable, complete, fitting ending to the story that had come before (funny enough, I would wager that more people guessed the ending of Breaking Bad than guessed the ending of How I Met Your Mother, though that’s neither here nor there). But in the current cultural environment, a person can gain quite a bit of attention for boasting that unlike those blubbering fake fans, they LIKED that this ending didn’t conclude the arcs that had built for years, didn’t pick up dropped plot threads, didn’t allow protagonists to learn anything or achieve their goals, and so on and so forth. That they, by virtue of some unspecified quality, didn’t NEED an ending like that in order to enjoy what they were watching. Do I believe people who say this? Well, maybe. Human opinions are varied, and I don’t allege some conspiracy where everyone secretly hates the same things I hate. Nonetheless, I often find a degree of disingenuousness in these statements. A good ending can be obvious, unexpected, happy, sad, or even ambiguous–but more often than not, what makes it good is that it is satisfying. And loving an ending because it is unsatisfying, because it gives the audience nothing it wants, runs counter to this instinct, like it or not.

To use one example of a satisfying ending (albeit not a true ending, since it comes in the middle installment of a trilogy), Darth Vader’s revelation that he is Luke Skywalker’s father has gone down as one of the greatest plot twists in cinema history. Indeed, if you didn’t know that a mystery like this was building, you’d never think to put the pieces together–the ominous references to Luke having “too much of his father in him” or having “much anger…like his father,” the Chekhov’s gun of Anakin’s murder that goes unaddressed throughout A New Hope, and so on. But this twist is somewhat unique in that much of the buildup to it was done retroactively. During the writing of A New Hope, there was no plan for Vader to be Luke’s father–instead, the decision was the result of looking back at what the story had built, and following it to a coherent, unexpected, yet somehow totally natural conclusion that set up compelling stakes for the subsequent chapter. That is why the Vader twist works–it wasn’t chosen purely so the audience couldn’t guess the ending of the film, it was chosen because that was a compelling direction for the story to go, because it complicated and heightened the stakes, and because it deepened the existing text through unexpected means. In other words, arguably the greatest movie twist in history wasn’t great just because it was hard to guess, it was great because of the emotional impact of looking backwards and realizing how well it fit into the framework that was already in place despite the twist being unexpected. The surprise on its own is only a surprise; the surprise filling in the blanks of the story so effectively is what makes it sublime.

So why, then, do we find ourselves sucked into a maelstrom of hot takes every time we say we dislike a shock-value ending? And why does this trend seem to have gotten so much worse in recent years?