#Wynton Marsalis Quintet

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Branford Marsalis: Jazz Virtuoso and Boundary Pusher

Introduction: Few names in the jazz world have the same impact as Branford Marsalis. Marsalis, who is renowned for his dazzling saxophone performances and outstanding range, has not only made an enduring impression on the genre but has also forged a unique musical identity that goes beyond convention. The life, career, and musical contributions of Branford Marsalis are explored in this…

View On WordPress

#Alvin Batiste#Art Blakey#Branford Marsalis#Branford Marsalis Quartet#Crazy People Music#Ellis Marsalis#Eric Revis#Eternal#Jazz History#Jazz Messengers#Jazz Saxophonists#Jeff "Tain" Watts#Joey Calderazzo#Kenny Kirkland#Robert Hurst#Sting#Wynton Marsalis#Wynton Marsalis Quintet

0 notes

Text

Wynton Learson Marsalis (October 18, 1961) is a trumpeter, composer, teacher, and artistic director of Jazz at Lincoln Center. He has promoted classical and jazz music, often to young audiences. He has won at least nine Grammy Awards, and his Blood on the Fields was the first jazz composition to win the Pulitzer Prize for Music. He is the only musician to win a Grammy Award in jazz and classical during the same year.

He was born in New Orleans and grew up in the suburb of Kenner. He is the second of six sons born to Dolores Ferdinand Marsalis and Ellis Marsalis Jr., a pianist and music teacher. He was named after jazz pianist Wynton Kelly. Branford, Jason, and Delfeayo are jazz musicians. While sitting at a table with trumpeters Al Hirt, Miles Davis, and Clark Terry, his father jokingly suggested that he might as well get him a trumpet, too. Hirt volunteered to give him one, so at the age of six, he received his first trumpet.

In 1979, he moved to New York City to attend Juilliard. He intended to pursue a career in classical music. In 1980 he toured Europe as a member of the Art Blakey big band, becoming a member of The Jazz Messengers and remaining with Blakey until 1982. He changed his mind about his career and turned to jazz. He has said that years of playing with Blakey influenced his decision. He recorded for the first time with Blakey and one year later he went on tour with Herbie Hancock. After signing a contract with Columbia, he recorded his first solo album. In 1982 he established a quintet with his brother Bradford, Kenny Kirkland, Charnett Moffett, and Jeff “Tain” Watts. When Branford and Kenny Kirkland left three years later to record and tour with Sting, he formed another quartet, this time with Marcus Roberts on piano, Robert Hurst on double bass, and Watts on drums. The band expanded to include Wessell Anderson, Wycliffe Gordon, Eric Reed, Herlin Riley, Reginald Veal, and Todd Williams.

He is the son of the late jazz musician Ellis Marsalis Jr. and grandson of Ellis Marsalis Sr. His son, Jasper Armstrong Marsalis, is a music producer known professionally as Slauson Malone. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellencence

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wynton Marsalis (tp), Branford Maralis (ts), Kenny Kirkland (p), Phil Bowler (b), Jeff 'Tain' Watts (dr)

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The dapper and sagacious Ahmad Jamal may have looked more like a UN delegate than a jazz musician, but he was recognised as a truly great jazz artist by some of the music’s most notable pioneers. Jamal, who has died aged 92, was hailed in the 1940s and 50s by Art Tatum and Miles Davis, and more recently by McCoy Tyner and Keith Jarrett. In the 90s, when a jazz piano-trio renaissance was being led by gifted newcomers such as Brad Mehldau, Jason Moran, Geri Allen and Esbjörn Svensson, Jamal did not retire to the sidelines but played better than ever. The former Wynton Marsalis pianist and composer Eric Reed has said that Jamal is to the piano trio “what Thomas Edison was to electricity”.

He was a fascinating philosopher of contemporary music and a lifelong critic of the entertainment business, which he accused of fleecing African-American artists. Although he recognised the structural and technical distinctions of jazz and European classical music, he was adamant that there was no superiority of one over the other in what he called “the emotional dimensions”. “You have to know what the hell you’re doing,” he told me in 1996, “whether you’re playing the body of work from Europe or the body of work from Louis Armstrong.”

Jamal was born Frederick Jones in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and regarded the eclectic musical culture of his birthplace as crucial to his development. His father was an open-hearth worker in the steel mills, but his uncle Lawrence played the piano and at only three years old Jamal was copying his playing by ear. He took lessons from seven, and would recall “studying Mozart along with Art Tatum”, unaware of white society’s widespread prejudice that European music was supposed to be superior to that of African-Americans. Significant influences in his early years were the music teacher Mary Cardwell Dawson (founder of the National Negro Opera Company), and his aunt Louise, who showered him with sheet music for the popular songs of the day. Pianists Tatum, Nat King Cole and Erroll Garner were among the young “Fritz” Jones’s principal jazz influences, and he also studied piano with James Miller at Westinghouse high school.

At 17 he toured with the former Westinghouse student George Hudson’s Count Basie-influenced orchestra, worked in a song-and-dance team, and wrote one of his most enduring themes, Ahmad’s Blues, at 18. Two years later he adopted Islam, and the name Ahmad Jamal. He also joined a group called the Four Strings, which became the Three Strings with the departure of its violinist, and caught the ear of the talent-spotting producer John Hammond, who signed the trio to Columbia’s Okeh label.

The public liked Jamal’s distinctive treatments of popular songs, and so did Davis. Developing his new quintet in 1955, Davis sent his rhythm section to study Jamal’s then drummer-less group. Davis liked Jamal’s pacing and use of space (the prevailing bebop jazz style was usually hyperactive), and he noticed that Jamal’s guitarist, Ray Crawford, often tapped the body of his instrument on the fourth beat. Davis told his drummer, Philly Joe Jones, to copy the effect with a fourth-beat rimshot, which became a characteristic sound of that ultra-hip Davis ensemble. Davis began to feature Jamal’s originals and arrangements in his own output, including New Rhumba (on his 1957 Miles Ahead collaboration with Gil Evans), and Billy Boy (on 1958’s classic Milestones session).

The gifted young Chicago bassist Israel Crosby joined the trio in 1955, and the following year the percussionist Vernel Fournier – who fulfilled Jamal’s requirements for a subtle hand-drummer as well as orthodox sticks-player – replaced Crawford. The group became the house band at the Pershing Hotel in Chicago, and one night in January 1958 they recorded more than 40 tracks there. One was Poinciana, which had been a hit tune from the 1952 movie Dreamboat. Jamal modernised its Latin groove, maintained a catchy hook throughout the improvisation, and found himself with a pop hit that stayed in the charts for two years.

Eight songs from that night, including Poinciana, made up the million-selling album At the Pershing: But Not for Me. Jamal’s newfound wealth led him to branch out into club ownership by opening the Alhambra in Chicago, though the venture barely lasted a year. Crosby and Fournier left for the pianist George Shearing’s group in 1962, and Jamal recorded the Latin-influenced Macanudo album the next year, with a new trio and a full orchestra. He also explored his cultural and ancestral roots in Africa, then recorded Heat Wave in 1966 – with a new group (Jamil Nasser on bass and Frank Gant on drums) and a more contemporary feel, reflected in the funkier approach to his old piano hero Garner’s Misty.

Jamal’s knack of keeping audiences mesmerised with unexpected modulations, time changes and catchy riffs, while never losing the undercurrent of the tune, was still unmistakably intact. His trademark device of insinuating a song – through toying with its bassline or its characteristic groove, but endlessly delaying the appearance of the tune – was adopted by many later jazz pianists, including such contemporary masters as Mehldau.

In 1970 Jamal recorded Johnny Mandel’s M*A*S*H theme for the movie’s soundtrack, and with the albums Jamaica (in 1974, which included Marvin Gaye’s Trouble Man as well as M*A*S*H) and Intervals (1979, which included a Steely Dan cover), showed he was not averse to toying with pop forms and even electric pianos. But he soon returned to the jazz of his roots. In 1982 he made the live album American Classical Music (it was the term he always preferred to the word “jazz”), sustained a steady output through the decade, and with Chicago Revisited (1992) sounded as assured and inventive as ever.

Now in his 60s, Jamal began to develop a higher profile in Europe. Sessions for the Dreyfus label in France led to The Essence (issued in three parts in the 90s), and found him in full flight with the saxophonists George Coleman and Stanley Turrentine and the trumpeter Donald Byrd. In 1995 his version of Music, Music, Music and the original take of Poinciana were featured in the Clint Eastwood film The Bridges of Madison County. He made what he regarded as one of his best recordings with Live in Paris 1996 (featuring Coleman again), and returned to the city to celebrate his 70th birthday in 2000 with Coleman; he was in inspired form on what would be released as the album A l’Olympia (2001).

With the exciting James Cammack on bass and Idris Muhammad on drums, Jamal’s composing blossomed. Striking originals dominated his 2003 album In Search of Momentum, and he even made a faintly stagey but soulful foray into singing, amid a raft of virtuoso keyboard displays, on After Fajr (2005).

Jamal’s alertness to an irresistible riff, like his keyboard contemporary Herbie Hancock’s, made him a favourite with hip-hop artists, and De La Soul’s Stakes Is High and Nas’s The World Is Yours were among many unmistakable testaments to that. Mosaic Records’ nine-CD set of his game-changing work in the late 1950s and early 60s was released in 2011, his group made a spectacular live appearance in London in 2014, and his last album releases came in 2022 with Emerald City Nights: Live at the Penthouse, parts one and two, featuring live recordings made in Seattle during the 60s. A third in the series is due for release this year.

Jamal was married and divorced three times – to Virginia Wilkins, Sharifah Frazier and Laura Hess-Hay. He is survived by a daughter, Sumayah, from his second marriage, and two grandchildren.

🔔 Ahmad Jamal (Frederick Russell Jones), musician, born 2 July 1930; died 16 April 2023

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

LÉGENDES DU JAZZ

ELLIS MARSALIS, LE PATRIARCHE

‘’The greatest influence on me was seeing his dedication to music during the many times when he wasn’t playing gigs that much. Even without any work and no money coming in from music, he had such true love for the music that he didn’t let anything shake his confidence in the power that comes from really working on your sound and not trying to avoid any of the things you have to know if you’re truly going to be a jazz musician.’’

- Wynton Marsalis

Né le 14 novembre 1934 à La Nouvelle-Orléans, Ellis Louis Marsalis Jr. était le fils d’Ellis Marsalis Sr., un homme d’affaires et activiste, et de Florence Marie Robertson. Propriétaires du Marsalis Motel de La Nouvelle-Orléans, la famille Marsalis avait accueilli des visiteurs prestigieux comme Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Ray Charles et Thurgood Marshall, le président de la National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) qui était devenu plus tard le premier juge afro-américain de la Cour Suprême.

À partir de l’âge de onze ans, Marsalis avait joué de la clarinette à la Xavier University's Junior School of Music de La Nouvelle-Orléans, dans le cadre d’une formation préparatoire à son entrée à l’université. Il avait aussi joué du saxophone ténor et du piano au high school. Durant son adolescence, Marsalis avait demandé à sa mère de lui acheter un saxophone ténor afin qu’il puisse jouer du rhythm & blues, qui était la musique la plus populaire de l’époque. Marsalis s’était alors joint au groupe de son high school, les Groovy Boys.

En 1951, Marsalis était entré à l’Université Dillard à La Nouvelle-Orléans dans le cadre d’une majeure en musique. Marsalis avait décidé de se concentrer sur le piano après avoir entendu Nat Perrilliat jouer du saxophone ténor, car il ne croyait pas pouvoir l’égaler.

Au milieu des années 1950, Marsalis s’était joint au American Jazz Quartet composé d’Alvin Battiste à la clarinette, de Harold Batiste au saxophone ténor, de Richard Payne à la contrebasse et d’Ed Blackwell à la batterie. Même si le groupe n’avait pas décroché beaucoup de contrats à La Nouvelle-Orléans, il avait réussi à poursuivre ses activités durant un certain temps.

Marsalis avait décroché un baccalauréat en éducation musicale en 1955. L’année suivante, Marsalis avait travaillé comme assistant-gérant au motel de son père tout en continuant de jouer comme accompagnateur avec le American Jazz Quintet. À la fin de sa carrière, Marsalis avait poursuivi ses études à l’Université Loyola, toujours à La Nouvelle-Orléans, où il avait décroché une maîtrise en musique en 1986.

DÉBUTS DE CARRIÈRE

Après que Blackwell ait été recruté par Ornette Coleman pour aller jouer à Los Angeles, Marsalis et Harold Battiste avaient décidé de le rejoindre en Californie. À Los Angeles, Marsalis et Blackwell avaient joué avec Coleman durant deux mois. Après être retourné à La Nouvelle-Orléans pour devenir directeur temporaire du groupe de la Xavier Preparation School, Marsalis avait reçu son avis de mobilisation de l’armée à la fin de l’été.

En janvier 1957, Marsalis s’était joint à la Marine dans le cadre d’un service militaire de deux ans. Marsalis avait passé tout son service militaire dans le sud de la Californie et avait fait partie du Corps Four, un groupe de la Marine qui se produisait dans le cadre d’une émission de télévision hebdomadaire diffusée sur le réseau CBS intitulée Dress Blues. Il avait également participé à une émission de radio appelée "Leather Songbook’’ qui était aussi commanditée par la Marine. C’est dans le cadre de ces émissions que Marsalis avait commencé à accompagner des vocalistes.

Après sa démobilisation, Marsalis était retourné à La Nouvelle-Orléans où il avait formé un quartet avec le saxophoniste Nat Perrilliat et le batteur James Black. Le groupe avait enregistré un seul album intitulé Monkey Puzzle. Dans son compte rendu de l’album, le magazine Cadence avait commenté: "Marsalis' flowing, linear melodicism was a good foil for Perrilliat's more meticulous exploration of chord and rhythm changes." En 1962, Marsalis, Perrilliat et Black avaient également enregistré avec les frères Cannonball et Nat Adderley, mais l’album intitulé ‘’In the Bag’’ avait attiré peu d’attention.

C’est également à cette époque que Marsalis avait épousé Delores Ferdinand. Le couple avait eu six fils: Brandford, Wynton, Ellis III, Delfeayo, Miboya et Jason qui avaient tous été élevés dans la religion catholique. En 1964, Marsalis s’était installé avec sa famille dans la petite ville de Breaux Bridge, en Louisiane, où il avait travaillé comme directeur du groupe et de la chorale du Carver High School.

Marsalis avait continué de jouer à La Nouvelle-Orléans avec un succès modéré dans les années 1960. En 1966, Marsalis était retourné à La Nouvelle-Orléans et avait dirigé le trio-maison du Club Playboy.

À court de contrat, Marsalis se trouvait au club du trompettiste Al Hirt en 1967 lorsqu’on lui avait proposé de se joindre au groupe. Il expliquait: "Although it wasn't about where I wanted to be musically, it turned out to be a very good gig for me. It got me back into music on a full time basis, and that's probably the most important thing. Playing is always better than not playing." Même si le répertoire du groupe était limité et que son style était un peu trop influencé par le rock n’ roll au goût de Marsalis, son séjour avec la formation lui avait permis d’amasser plus d’expérience et de visibilité, ce qui lui avait permis de participer à des émissions de télévision comme le Today Show, le Mike Douglas Show et le Ed Sullivan Show. Marsalis avait quitté le groupe de Hirt en 1970.

En 1971, Marsalis avait commencé à jouer avec le Storyville Jazz Band de Bob French. Il pr��cisait: "That's when I began to learn how to play the traditional literature.’’ L’année suivante, Marsalis avait co-dirigé la ELM Music Company avec le batteur James Black. Le quintet avait joué durant environ un an et demi au Lu and Charlie's, un populaire club de La Nouvelle-Orléans. Son séjour avec le groupe avait été plutôt décevant pour Marsalis, qui avait expliqué au cours d’une entrevue accordée au magazine Down Beat: "We had some good original stuff, but I'm telling you, it was two or three steps ahead of a rock band."

LE PROFESSEUR

Même si Marsalis avait obtenu un certain succès à La Nouvelle-Orléans, il était plutôt inconnu à travers les États-Unis. Il expliquait: "I wasn't able to put it together. When I was growing up, the way that one succeeded in music was to pack up to New York and take a chance. By the time I was really thinking about doing that, we had a lot of kids. It wasn't an easy decision to make to do that, on that kind of gamble." Afin de gagner sa vie, Marsalis avait continué de jouer à La Nouvelle-Orléans et avait commencé à enseigner dans les écoles secondaires. En 1967, Marsalis avait également enseigné la musique afro-américaine et l’improvisation comme professeur adjoint à Xavier University.

En 1974, Marsalis était devenu professeur au New Orleans Center for Creative Arts High School (NOCCA), où il avait travaillé durant les douze années suivantes. Dans le cadre de ses fonctions, Marsalis avait servi de mentor à de nombreux jeunes musiciens, dont les trompettistes Terence Blanchard, Marlon Jordan et Nicholas Payton, le pianiste Harry Connick Jr., le saxophoniste Donald Harrison, le flûtiste Kent Jordan et le bassiste Reginald Veal. Quatre des fils de Marsalis, Wynton, Branford, Delfeayo et Jason, étaient aussi devenus des musiciens respectés. Excellant tant au saxophone ténor que soprano, Branford avait même été directeur musical du groupe du Tonight Show avec Jay Leno. Même s’il était tromboniste, Delfeayo s’était surtout fait connaître comme producteur et avait produit pratiquement tous les albums de ses frères et de son père depuis le milieu des années 1980. À l’âge de quatorze ans, le plus jeune fils d’Ellis, Jason, avait joué de la batterie sur l’album de son père intitulé Heart of Gold en 1993.

Comme professeur, Marsalis incitait ses étudiants à s’intéresser à l’histoire du jazz et à découvrir leur propre son. Il expliquait: "We don't teach jazz, we teach students.’’

De 1986 à 1989, Marsalis avait également enseigné à la Virginia Commonwealth University à Richmond, en Virginie, où il avait été coordonnateur du programme de jazz durant deux ans. Après avoir obtenu un doctorat honorifique de l’Université Dillard en 1989, Marsalis s’était joint la même année à l’Université de La Nouvelle-Orléans où il avait été directeur du programme de jazz jusqu’à sa retraite en 2001. En plus de son doctorat honorifique de l’Université Dillard, Marsalis avait également obtenu des honneurs semblables de l’Université Ball State (1997), de la Juilliard School of Music (2003), de l’Université Tulane (2007), de la Virginia Commonwealth University (2010) et du Berklee College of Music (2018).

Avec ses fils, Marsalis avait été nommé ‘’Jazz Master’’ par la National Endowment for the Arts en 2011. Intronisé au Louisiana Music Hall of Fame en 2008, Marsalis avait également remporté un ACE Award en 1984 pour sa participation à des émissions diffusées sur le câble.

DERNIÈRES ANNÉES

Marsalis avait commencé à enregistrer comme leader relativement tard. Après avoir enregistré seulement quelques albums en près de trente ans de carrière, Marsalis avait enregistré son premier album comme leader en 1982. Intitulé Father and Sons, l’album avait été enregistré avec ses fils Wynton et Branford. Commentant l’album dans le magazine Melody Maker, le critique Brian Case écrivait: "Father Ellis has no trouble bedding right down in [the] fast company [of Branford and Wynton], being a fleet boppish piano player of some originality." Les albums suivants de Marsalis avaient également été très bien reçus, plus particulièrement Syndrome et Homecoming, dans lesquels il avait démontré sa grande expérience. Décrivant l’album de Marsalis enregistré avec le saxophoniste Eddie Harris, le critique Jon Balleras avait précisé: "To say these players are seasoned would be the height of understatement; their playing makes it evident that both men have long since surpassed the point of mastering their instruments and improvisational theory, transcending technique and stylistic limitations to forge a completely transparent, immediate music, music of a broad swirl and swell."

En 1987, Marsalis avait également écrit la musique pour la version enregistrée de la légende du roi Midas. C’est l’acteur Michael Caine qui avait effectué la narration. Le violoncelliste Yo-Yo Ma avait aussi participé à l’enregistrement.

En 1994, Marsalis avait publié Whistle Stop, un album dans lequel il avait repris plusieurs de ses compositions des années 1960, dont plusieurs avaient été co-écrites avec le batteur James Black. Même si le critique Larry Birnbaum du magazine Down Beat avait salué la performance de Marsalis, il avait ajouté que son jeu avait souvent été éclipsé par ses accompagnateurs. Birnbaum précisait: "The subtle artistry of his elegant phrasing and refined touch are best appreciated on the closing ballad... where he plays unaccompanied." Pour sa part, Marsalis avait fait remarquer que son intention était d’écrire pour de grandes formations et d’explorer des formats de plus longue durée. Il avait expliqué: "[Whistle Stop] with its emphasis on the small ensemble represents the pinnacle of my work in that format."

Marsalis avait également siégé sur des comités de la National Endowment for the Arts et de la Southern Arts Federation. Marsalis a été intronisé au sein du Louisiana Music Hall of Fame le 7 décembre 2018. Le Ellis Marsalis Center for Music avait également été nommé en son honneur.

En 2010, la famille Marsalis avait publié un album live intitulé Music Redeems. L’album avait été enregistré au John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts de Washington, D.C., dans le cadre de Duke Ellington Jazz Festival. Tous les profits résultant de la vente de l’album ont été versés directement au Ellis Marsalis Center for Music. En 1990, Marsalis avait également fait une apparition sur l’album de son fils Wynton intitulé Standard Time Vol. 3 The Resolution of Romance. Participaient aussi à l’album le contrebassiste Reginald Veal et le batteur Herlin Riley. Interrogé par Stanley Crouch, Wynton Marsalis avait décrit ce qu’il avait ressenti en travaillant avec son père dans lle cadre de l’album Wynton Marsalis, Standard Time Vol. 3 en 1990:

‘’Besides Marsalis’ own development, the force of heart and the rhytmic finesse heard in the lyricism of this recording are due to the presence of his father, Ellis, at piano. ‘’I always wanted to do an album with him, but I never felt prepared because I didn’t play well enough on changes and have a sound good enough to pay the kind of homage to my father that I really felt. Just having the opportunity to listen to his sound for all of those years when I was growing uo was a tremendous inspiration for me and for my brothers, all of us. The greatest influence on me was seeing his dedication to music during the many times when he wasn’t playing gigs that much. Even without any work and no money coming in from music, he had such true love for the music that he didn’t let anything shake his confidence in the power that comes from really working on your sound and not trying to avoid any of the things you have to know if you’re truly going to be a jazz musician. The kind of belief he had in music would make you realize that you can only go forward by facing the obligation of mastering the weight of what the titans of the idiom have laid down.’’

Membre de la Phi Beta Sigma et de Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia, deux organisations humanistes, Marsalis s’était vu décerner le titre de 24th Man of Music par la Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia en 2015 pour avoir fait avancer la cause de la musique en Amérique.

Ellis Marsalis est mort le 1er avril 2020 dans un hôpital de La Nouvelle-Orléans à la suite d’une pandémie contractée dans le cadre de la pandémie de la Covid 19. Il était âgé de quatre-vingt-cinq ans. Souffrant d’autisme, le plus jeune fils de Marsalis, Mboya Kenyatta Marsalis, avait été élevé par son frère Delfeayo après la mort de son père. La femme d’Ellis, Dolores, était morte en 2017. Ont survécu à Marsalis ses fils Branford, Wynton, Ellis III, Defeayo, Mboya et Jason.

Même si sa carrière avait souvent été éclipsée par ses célèbres fils Wynton et Branford, Marsalis a enregistré près de vingt albums comme leader au cours de sa carrière. Il a aussi joué comme accompagnateur avec des musiciens comme David "Fathead" Newman, Eddie Harris, les frères Cannonball et Nat Adderley, Ornette Coleman, Ed Blackwell, Marcus Roberts et Courtney Pine. Même s’il avait joué avec les plus grands noms du jazz, Marsalis était particulièrement fier de sa carrière comme enseignant et pédagogue. En 1999, D. Antoine Handy a consacré une biographie à Marsalis intitulée Jazz Man’s Journey: A Biography of Ellis Louis Marsalis, Jr.

Insulté que son père ait souvent été accusé d’avoir profité de la notoriété de Wynton et Branford pour connaître la célébrité, son fils Ellis III avait déclaré: ‘’I become irritated when people say, ‘’Youf father is ‘cashing in’ on the success of Wynton and Branford. I have to correct them. The old man’s been doing his thing for a long time. High standards always; he’s been very consistent. There’s been no ‘cashing in.’’ He’s been playing forever. As children, we’d to to gigs with him. There weren’s many in the audience. But it didn’t bother him. He plays what he plays and is not fazed by what others do.’’ On pouvait également lire sur le site All Music Guide to Jazz: ‘’It is a bit ironic that Ellis Marsalis had to wait for sons Wynton and Branford to get famous before he was able to record on a regular basis, but Ellis has finally received his long overdue recognition.’’ Après la mort de son père, le saxophoniste Branford Marsalis lui avait rendu hommage en déclarant:

“My dad was a giant of a musician and teacher, but an even greater father. He poured everything he had into making us the best of what we could be.’’ De son côté, le professeur de droit David Wilkins de l’Université Harvard avait commenté: ‘’We can all marvel at the sheer audacity of a man who believed he could teach his black boys to be excellent in a world that denied that very possibility, and then watch them go on to redefine what excellence means for all time.”

©-2024, tous droits réservés, Les Productions de l’Imaginaire historique

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Obed Calvaire 150 Million Gold Francs

Obed Calvaire 150 Million Gold Francs Ropeadope Obed Calvaire is one of jazz’s renowned drummers who made his mark with the SF Jazz Collective and Wynton Marsalis’ Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, among other ensembles. On 150 Million Gold Francs Calvaire leads a quintet in an especially timely project, given the ongoing strife in Haiti, as he was born of Haitian parentage. He’s intent on…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Video

vimeo

Yesterdays by Wynton Marsalis Quintet, live in Wellington, New Zealand, 1988

#music#jazz#wynton marsalis#wynton learson marsalis#wynton marsalis quintet#todd williams#marcus roberts#todd maxwell williams#reginald veal#herlin riley#live#live music#wellington#video#live video#concert

9 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Joe Fiedler’s Open Sesame - Fuzzy and Blue - my WVUD pal Ako turned me on to this last night, a trombone-led quintet doing Sesame Street songs! (Oh, and Fiedler actually works on Sesame Street!)

In 2019 trombonist Joe Fiedler released Open Sesame, packed with inventive jazz readings of material drawn from his longstanding “day job” as an EMMY-nominated music director and staff arranger for the famed children’s show Sesame Street. The effort was equally beloved by lay listeners and the jazz world alike. DownBeat praised the music’s “diverse aesthetic,” in which Fiedler blends “elements of funk, rock, free-jazz and New Orleans polyphony into a potent mix that gives depth and texture to the lighthearted compositions.” When Fiedler and the band toured the music, including a stop at Dizzy’s Club Coca-Cola with guest luminaries Wynton Marsalis and none other than Elmo himself, the realization set in that the project would be no one-off. “I have these songbooks from the Sesame Street office,” Fiedler says, “and if you whip through the first 30 tunes, absolutely everyone knows them. But there are six or seven thousand songs they’ve done over the past 50 years, with plenty of gold in there to do a second album for sure.” Fuzzy and Blue, Fiedler’s second volume of Sesame Street songs, shines still more light on the extraordinary wit and melodic gift of the foundational Sesame Street composers Joe Raposo and Jeffrey Moss, among others. The album boasts the same top-tier lineup as Open Sesame, with a couple of twists. Trumpeter Steven Bernstein, who played on only part of Open Sesame, now becomes an integral cog in a nimble three-horn section, expanding and varying the palette and allowing Fiedler to bring his seasoned orchestration skills to the foreground. Reedman Jeff Lederer plays tenor and clarinet and relies more heavily on soprano sax this time out, helping achieve the ideal blend of colors and registers that Fiedler was seeking. Drummer Michael Sarin and bassist Sean Conly keep the rhythms locked and creatively churning, from the Dr. John/Professor Longhair vibe of “Fuzzy and Blue” to the reggae feel of “Elmo’s Song” (by Tony Geiss), to the Hugh Masekela-inspired Afropop of “Ladybug’s Picnic” (originally a peppy country novelty by the late William “Bud” Luckey). The ensemble also gets a visit from vocal powerhouse Miles Griffith, the very model of a guest on Sesame Street. On the “I Love Trash/C Is for Cookie” melange (a one-two shot of Moss and Raposo), Griffith’s singing is unabashed, larger than life, uproariously funny but insightful and firmly in control. He’s equally compelling in a sociopolitical vein on “I Am Somebody,” in which Fiedler combines an original song with the lyrics of Reverend William Holmes Borders — words recited to powerful effect on Sesame Street in 1972 by Reverend Jesse Jackson. Fiedler felt a need on Fuzzy and Blue to acknowledge social tumult at the close of the Trump presidency and the still-tentative aftermath of the COVID pandemic. “We Are All Earthlings,” a gentle and idyllic Jeffrey Moss folk ballad from 1993, accomplishes this as well, though Fiedler brings a stark added tension with his Stravinsky-esque horn voicings. Throughout the album there’s an atmosphere of fun, “a sense of burlesque” as Fiedler put it in the Open Sesame liner notes, that flows from the trombonist’s deep love of Ray Anderson, the Jazz Passengers, Carla Bley and other major influences. Steven Bernstein’s Sexmob is another. The improvisational openness and risk of Fiedler’s trio dates Sacred Chrome Orb, The Crab, I’m In and Joe Fiedler Plays the Music of Albert Mangelsdorff also carry over to this more song-oriented endeavor. Fuzzy and Blue, like its predecessor, is Fiedler’s way of bringing it all together, reminding himself and all of us that inspiration can and does come from everywhere, and that everything is connected.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Think of One

Wynton Marsalis Quintet

Wynton Marsalis – trumpet Branford Marsalis – sax Kenny Kirkland – piano Ray Drummond – bass Jeff “Tain” Watts – drums

#Think of One#Wynton Marsalis#Branford Marsalis#Kenny Kirkland#Ray Drummond#Jeff Tain Watts#Thelonious Monk#Youtube

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

ON THE ALL-STAR JAZZ BAND

COUCH TOUR: THE HEAVY HITTERS (Mike LeDonne, Eric Alexander, Jeremy Pelt, Jim Snidero, Alexander Claffy, and Kenny Washington!), SMOKE JAZZ CLUB, 19 AUGUST 2022, 2nd Set

BLACK ART JAZZ COLLECTIVE (Wayne Escoffery, Jeremy Pelt, James Burton III, Xavier Davis, Vincente Archer, and Darrell Green), DIZZY’S AT LINCOLN CENTER, 2017 via YouTube

Let’s start with The Greatest Jazz Concert Ever by THE Quintet (Charlie Parker, his worthy constituent Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, Charles Mingus, and Max Roach) at Toronto’s Massey Hall in 1953. Quite a band with plenty of overlaps in NYC clubs and recordings, but pulled together for the occasion with a quintessential bebop set that makes a good stab at living up to its name.

But jazz, with its standard book and sessions, seems so well suited to the format that you could say that the Verve, Prestige, and especially Blue Note albums of the 1950s and 1960s were all-star bands—Dexter Gordon and Freddie Hubbard with Butch Warren and Billy Higgins on Takin’ Off where, arguably the leader, Herbie Hancock, was the only non-all star even if he brought in tunes like Watermelon Man and Alone and I. But those albums had leaders who brought in the tunes even if Rudy Van Gelder, Alfred Lion, and Norman Granz helped figure out who was on the session.

No, I think what I’m discussion here is the deliberately formed band, that whatever leadership structure, is designed to put and, as importantly, keep a core of players working together.

In the 1980s, a more avant-garde group of players including Chico Freeman, Don Cherry then Lester Bowie, Arthur Blythe, Don Pullen to Hector Ruiz to Kirk Lightsey, Cecil McBee, and Don Moye then Billy Hart were The Leaders. They were during my hiatus so I don’t know their albums. Then McBee and Hart are in the occasionally still active The Cookers with Eddie Henderson, Billy Harper, George Cables and the organizer David Weiss. I’ve like their recordings but I can’t say they are more than the sum of their parts.

Let’s see if Artemis can bounce back after lockdown, but their parts—Renee Rosnes, Allison Miller, Anat Cohen, Ingrid Jensen, Nicole Glover replacing Melissa Aldana, and Noriko Ueda—are formidable. Their album and Jazz St Louis show were appealing, but I’m happy to see Anat Cohen and Allison Miller’s Boom Tic Boom this coming season. I don’t miss Aldana or Glover when they show up on the streams. But are they or any of these ensembles a team or just all-stars?

I’d spent the week listening to lots of Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, so sextets and retrospective all-stars. But those were his bands with 35 years of consistent vision even as the music directors shifted from Benny Golson to Wayne Shorter to Wynton Marsalis and beyond.

Comes now The Heavy Hitters, with Mike LeDonne and Eric Alexander as leaders, as a recent addition to the format. These musicians are solid regulars I know from Small’s Live. Kenny Washington is the out and out all-star among them, but seeing him with horns is a treat. Indeed, such ensembles, often sextets, are an identifying feature of the format as clubs, on a night to night basis are trios or one horn and rhythm section with the occasional quintet. Jeremy Pelt is probably next in this pantheon for some very tasty trumpet work, but I also tend to underrate and undervalue the bench of trumpet players. I’ve liked Alexander of late for a nice middle tone and linear solos and Alexander Claffy is a welcome name on any gig for his reliability. It is LeDonne who is sometimes heavy handed, but not here. Indeed he steps out here with the bulk of the tunes and some solid not overly fussy soloing. Pelt was his reliable self with fine tone and thoughtful solo work. The most appealing horn was Jim Snidero’s alto and he’s the one who isn’t quite the streaming regular. But again the treat was to hear Kenny Washington have a horn section to whip into shape with his taste, elegance, and velvet glove power.

I thought I would get a Small’s Archive show from 2018 from the Black Art Jazz Collective but instead I found a 2017 gig on YouTube from Dizzy’s in Lincoln Center. The Small’s gig rhythm section was Victor Gould whom I’d heard in a recent trio gig, Rashaan Carter, and Johnathan Blake who would have been fun to hear with horns after lots of trio work. Instead, the Wayne Escoffery, Jeremy Pelt, and James Burton III frontline had Xavier Davis, Vincente Archer, and Darrell Green backing them up. Everybody got some space, but yes with six pieces the rhythm section made their marks with strong accompaniment. And they did. Archer is surprisingly forceful behind his thick spectacles and Darrell Green is solid. I did not know Xavier Davis but he shone in his couple of solos but even more in some very sympathetic fills and comping. I catch Escoffery often and he is, as he was here, solid and rich, but as the tenor player he wailed a bit. It was Pelt who was consistently tasteful, though he could growl. Burton was rich and patient in his soloing. The tunes were originals but thematically about the Black experience and so evoked WEB DuBois and Sojourner Truth as well as the plaint When Will We Learn.

BAJC, like Artemis and all of these ensembles, may be an occasional ensemble. I won’t wait for either of them or the Cookers or the Heavy Hitters to hear their members when they go out on their own gigs. But the all-star band has the advantage of, well, having all-stars.

1 note

·

View note

Link

Piano quintets by Amy Beach and Florence Price, Baroque music from Guatemala, and the premiere recording of Wynton Marsalis’ Symphony No. 2 headline our recent classical reviews, along with a narrative-choral-dance project by Jerod Impichchaachaaha’ Tate showcasing Chickasaw music and stories.

via AllMusic Blog

1 note

·

View note

Text

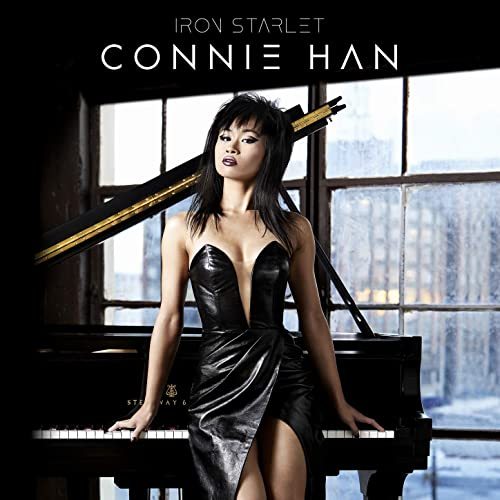

Connie Han: Iron Starlet (Mack Avenue, 2020)

Connie Han: piano & Fender Rhodes; Ivan Taylor: bass; Bill Wysaske: drums; Walter Smith III: tenor saxophone, Jeremy Pelt: trumpet.

When 23 year old pianist Connie Han released Crime Zone, her Mack Avenue debut in 2018 it caused quite a sensation. For starters, she used the influences of Kenny Kirkland and Mulgrew Miller along with those of McCoy Tyner, Hank Jones and others to put her spin on the post bop music that young musicians made following the arrival of Wynton Marsalis. Now, with her sophomore Mack Avenue release Iron Starlet Han shows growth from Crime Zone and also plenty of potential with expansions into other directions. Here she mixes even more refined examples in the burnout style heard previously; head bobbing swing, expressive ballads. She uses her working trio, bassist Ivan Taylor and drummer/producer/composer Bill Wysaske, augmented by Walter Smith III (returning from the previous album) and Jeremy Pelt on trumpet on select tracks in full quintet and quartet formations.

What in part and parcel makes this music successful and enjoyable is that it is road tested. Han and Wysaske did not just bring in the charts for some of this very difficult music for a first time studio run down-- they played much of the material on the road, including a stop at New York's Jazz Standard last summer. The other common denominator is the Wynton, Branford, Terence Blanchard, Kenny Garrett, Kenny Kirkland and Jeff “Tain” Watts stream of playing the new compositions take their cue from and expand on. It's all music that Pelt, and Smith III had also grown up on so it's a natural fit. For musicians in their 30's and 40's, it's nearly impossible to not be influenced by albums the above named players made that boldly through their own lens blended the kind of energy found on the best jazz-rock and jazz-funk records, the defining Blue Note albums of the 60's, and some of the pivotal albums from John Coltrane, McCoy Tyner and Pharoah Sanders.

Han's interest in insistent rhythm and locking into a stone groove with Taylor and Wysaske announces the title track with powerful conviction. The knotty theme has the striking use of piano and bass unison like that of “Southern Rebellion” on Crime Zone with abrupt thematic passages for Pelt's trumpet and winding unisons for Pelt and the pianist. For Pelt's bravura solo, staccato eighth note jabs and legato tones incite Han's comping figures, prompting eruptions from Wysaske's drums. Han's solo is brash, rhythmic acuity a defining feature; Taylor locked in his walk, Wysaske's short high hat chokes on the upbeat and swiss triplet figures in groups of five stoking the flames even more. If the first four minutes of the album are a thrilling joy ride on the Audobon, then Wysaske's attractive “Nova”, the first tune to feature Han on Fender Rhodes electric piano shows how adept the pianist is at switching moods. This is where the growth from Crime Zone really begins to shine through. Pelt and Smith III play Wysaske's pretty melody as if they are skaters on ice, Han's Rhodes solo is filled with a warm glow, keen sense of space, and blues undercurrent. Her playing on the coda under Wysaske's straight eighth ride brings about a feeling of melancholy letting the glowing “Nova” go.

“Mr. Dominator” a Hank Jones and Mulgrew Miller inspired lesson in hard swing, is distilled here to it's essence from the lengthy versions the trio played nightly. The pianist is sly, sultry and funky, freely using techniques of horn players in her improvisation ,while Wysaske sticks purely in service to the groove. Ivan Taylor gets his say with a Wilbur Ware and Jimmy Garrison depth of tone, and a brief economical drum solo bring things back the funky, memorable melody. “For the O.G.”, dedicated to the late McCoy Tyner conjures up some of the feeling of the pianist's defining 1970's Milestone albums. The pianist launches into the piece with determination, and her solo assimilates the innovations of Tyner wisely. Her use of the lick as a motivic device is dryly humorous, and her cadenza at the end demonstrates how much she loves and understands the Tyner style, but she uses the ground he broke to speak those lines in her own voice. Sandwiched between the head and the pianist's solo, Wysaske's drum solo has judicious use of toms as a thematic component.

Eugene McDaniels “Hello To the Wind” originally taped by vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson for his classic Now (Blue Note, 1970) and later reprised with the LA Philharmonic on the obscure Blue Note Meets The LA Philharmonic (Blue Note, 1977). McDaniels' lyrics and the entire Now album, in light of our divided social climate, and the general surge for change are as relevant in the present as they were then. Han's choice of chorused Rhodes and a Philip Glass like ostinato in the left hand, for the introduction with textures later thickened by acoustic piano add emotional weight to the piece. The deeply emotional current is further in her solo and Walter Smith III's tenor. Wysaske's tender ballad “Captain's Song” an ode to a French bulldog, has a gently floating feeling and Han digs deeply into color in her solo, much as she does on the drummer's gorgeous “The Forsaken”; making all the note choices count. Both “Boy Toy” and the closing homage to Wynton Marsalis' Black Codes From the Underground (Columbia, 1985) “Dark Chambers” mine the treacherous burnout territory once more, with the closing track in particular a marvel of focused intensity, and the rhythmic urgency found on the Marsalis recording. Han takes zero prisoners in her solo, using motivic development to smart effect. Smith III, and Pelt go full steam ahead as well for a wonderful conclusion to an engaging collection.

Sound:

Recorded at Sear Sound in New York City over two days in August, 2019 recorded and mastered by Chris Allen, and mixed by Patrick L. Smith at Dennis Songs Studio in Los Angeles Iron Starlet is a significant upgrade in sound from Crime Zone. Well done acoustic jazz recordings have a particular matter of fact quality to them that Iron Starlet definitely has in that the instrument tonalities are natural and realistic, the relatively dry sound stage bear this out. Han's piano shines on Focal Chorus 716 floor standing speakers, where it's midrange is one of it's strongest assets, and the stereo image of the piano is accurate to what is heard in real life. The Fender Rhodes tones are particularly fat and luxurious, the Chorus 716's again excelling at mid range. The upper end of Han's Rhodes work makes subtle use of Focal's patented inverted tweeter technology. The high end of her Rhodes silky and smooth, with the way the instrument is recorded there is an pleasing bell like ping in the upper notes, reminiscent of Bob James' signature Rhodes timbre on his classic work. Walter Smith III's warm tenor tone is captured attractively and Jeremy Pelt's rounded tone comes through without issue. Ivan Taylor's bass tones in the phantom center channel are rendered accurately on the Chorus 716's where some speakers may have difficulty with tones that deep. Finally Bill Wysaske's drums have the snare in the center image with ride cymbal on the right of center, high hat on far left, with splash and crash in the far left and right and tom drums far left and right. The snare has resonance but is contrasted with a weird hybrid Tony Williams 70's type sound with a more deadened one for the toms. As Wysaske is a lover of Steely Dan, this kind of tom sound is no surprise, but at first the subtle resonant-dead sound can take a minute to get used to. The deadened tom sound did appear on acoustic jazz albums in the 70's like Frank Butler's The Stepper (Xanadu, 1978) so it wasn't uncommon then, but album's like Butler's often had strange mixes, as did a lot of acoustic jazz of the period.

Final thoughts:

With Iron Starlet, Connie Han has truly arrived. This is very much a project of continued growth in an artist's journey. The assured ness that informs a very specific area of the jazz universe is heard through each one of her compositions, those of Wysaske's, and the lone standard “Detour Ahead” . Han is a driven and unshakably confident soloist always ready to burn, but she also exhibits a level of restraint and sensitivity that further drives home her passion. She has a trio that makes challenging music quite accessible, and with the added gusto of Walter Smith, III and Jeremy Pelt, the ensemble delivers on a high level the very visceral music that helped shape and establish many musicians who came in it's wake. Iron Starlet also points to Han's further potential, perhaps a double live album to cap off the music presented thus far on her Mack Avenue releases, an album with Kenny Garrett, Christian McBride and Jeff “Tain” Watts, or even an album expanding on the cyberpunk themes the pianist loves with her ethos at the core, enhanced by more Rhodes, keyboards and funky rhythms in addition to searing swing. The sky is the limit for Connie Han.

Music: 9/10

Sound: 9/10

Equipment used:

Yamaha RS202 stereo receiver

Focal Chorus 716 floor standing speakers

CD playback: 80GB Sony Playstation 3

Note: Jazz Views with CJ Shearn will now have a more detailed sound category offering audiophile insight into recordings as part of review thanks to upgraded equipment.

Key terms:

Sound stage: The audio depiction of the placement of instruments, as if one were to go see a play and see the position of the actors/actresses on stage, when a listener closes their eyes, they can see and hear the placement of the players and instruments. The term stereo image can also be applied.

Stereo imaging refers to the aspect of sound recording and reproduction of stereophonic sound concerning the perceived spatial locations of the sound source(s), both laterally and in depth. (source for stereo image definition: wikipedia)

youtube

#Connie Han#jazz#young lions#wynton marsalis#branford marsalis#kenny kirkland#mulgrew miller#fender rhodes#bob james

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Herbert “Herbie” Jeffrey Hancock (born April 12, 1940) is a pianist, composer, bandleader, and keyboardist. He was born in Chicago to Winne Belle Griffin, a secretary, and Waymand Edward Hancock, a government meat inspector. He performed at age 11 with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. He attended Wendell Philips High School, Roosevelt University, and Grinnell College, where he double majored and received degrees in Engineering and Music.

He recorded his first album in 1962. He then joined the Miles Davis Second Great Quintet. He signed with Warner Brother Records and composed the soundtrack for “Fat Albert and the Cosby Kids” TV series.

He and his sextet made the first of three albums that became known as the “Mwandishi” albums. He formed a new band, The Headhunters, and released three more albums. The first Head Hunters album was the first jazz album to reach platinum status. He toured with his V.S.O.P. Quintet. He released albums in Japan. He introduced trumpeter Wynton Marsalis to the world as a solo artist, by producing his debut album.

He produced soundtracks for Blow Up, The Spook Who Sat by The Door, and Death Wish. He won an Oscar for the score to Round Midnight. He has had many television appearances that led to hosting on the TV programs Rock School and Coast to Coast.

He collaborated with artists such as Chick Corea, Joni Mitchell, Stevie Wonder, Sting, Annie Lennox, and Kathleen Battle. Those collaborations as well as solo albums have earned Hancock numerous honors including Grammys and awards such as the Soul Train Music Award, the Kennedy Center Honors, and Lifetime Achievement Awards. He was the Norton Professor of Poetry at Harvard University.

He was named by the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra as Creative Chair for Jazz and serves as Institute Chairman of the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz. He is a founder of The International Committee of Artists for Peace, and was awarded the “Commandeur des Arts et des Lettres”. He was designated an honorary UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador.

Since 1972, he has practiced Nichiren Buddhism. He married Gigi Meixmer (1968) and has one daughter. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

1 note

·

View note

Text

1984 - Wynton Marsalis Quintet - Japanese tour

Wynton Marsalis (tp), Branford Marsalis (ts), Kenny Kirkland (p), ??? (b), Jeff 'Tain' Watts (dr)

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jimmy Cobb obituary

By John Fordham

Jazz drummer who continued to perform for half a century after recording Kind of Blue with Miles Davis

There are sublime moments in music that only the cognoscenti notice, plenty that millions love, and some that many sense without quite knowing why. Kind of Blue, the 1959 recording led by Miles Davis, had enough of all of them to become the bestselling jazz album ever.

Jimmy Cobb, the drummer and last surviving member of that landmark session, who has died aged 91, was not just a crucial contributor to a jazz revolution unleashed by it, but the instigator of a split-second playing choice on one of its best known themes that seems to define the here-and-gone magic of the best of jazz.

Cobb’s magic moment on So What, Kind of Blue’s opening track, was the quintessence of perfect timing and the definition of his receptive musical character. The tune’s setup seems to suggest at first that the music has nowhere to go, with the pianist, Bill Evans, apparently lost in preoccupied reflections around a slowly shifting three-chord motif with the bassist, Paul Chambers.

Evans then implies he has found a route out, thickening the chord harmonies before Chambers brings in the tune’s famously catchy bass hook, while Cobb ticks off a quiet pulse with a cymbal sound like someone idly shaking a bag of loose change, and Davis and the saxophonists John Coltrane and Julian “Cannonball” Adderley repeat a minimally simple rising and falling two-note hook.

Then Davis hangs out a single sustained note as if dangling it over a long drop, resolves it with an answer an octave beneath and Cobb breaks into a disruptive drum hustle and a cymbal smash as the trumpeter’s solo eases into swing, and such a captivating improvised trumpet solo that composers have since transcribed it for performance as if it had been laboured over note by note.

Cobb was to react instinctively to situations like that all his working life. That moment was not fortuitous for him, but the obvious option at the time for the astute 30 year-old percussion accompanist who had already partnered the vocal-toned R&B saxophonist Earl Bostic, the gospel-rooted and pop-savvy singer Dinah Washington , and Davis partners including pianist Wynton Kelly and Adderley. Those connections taught Cobb the patience to wait for the turning moment – in jazz, usually unscripted – of a soloist’s entry, the drive to power a blues, and much more.

Born in Washington, Jimmy was the son of Wilbur Cobb, a security guard and taxi driver, and his wife Katherine (nee Bivens), a domestic worker. As a teenager in the mid-1940s he became obsessed with jazz, staying up at night to listen to the American wartime DJ Symphony Sid’s broadcasts and washing dishes in diners to save money for a drumkit – on which he aimed to learn the polyrhythmic innovations of the bebop drum gurus Max Roach and Kenny Clarke. Largely self-taught, though he briefly studied with the National Symphony Orchestra percussionist Jack Dennett, Cobb had accompanied Billie Holiday in Washington and partnered Charlie Parker and Davis on Symphony Sid’s roadshow before he was 20.

By 1950, he was on the road with Bostic, whose hit-making R&B band of the period included such jazz-sax luminaries as Coltrane, Benny Golson, and Stanley Turrentine. Cobb and Kelly then accompanied Washington for some years, a period in which Cobb was having a relationship with her, and a young Quincy Jones was writing some of the singer’s arrangements.

The drummer’s antennae were retuned by the musical differences between his own Catholic background and Washington’s Baptist one. “When I heard that Baptist sound, it took me over,” Cobb later told the jazzwax.com’s blogger Marc Myers. “I wasn’t used to hearing that. It would make the hairs stand up on my arms and neck, where people are singing and shouting in church. That struck me right away. She taught me to put the passion into what I was doing.”

In 1956, Adderley hired Cobb to play on his Verve Records sessions Sophisticated Swing, Quintet In Chicago and Takes Charge, with the latter two staffed by the Miles Davis band without the trumpeter. Those connections led via brief stints with Stan Getz and Dizzy Gillespie to Kind of Blue, though Davis’s work in the period following ran on different tracks, with Coltrane and subsequently Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock exploring more modally stripped-down, scale-based music rather than the songlike forms Cobb had experienced with Bostic and Washington.

Cobb and Kelly played with the jazz guitarist Wes Montgomery between 1962 and 1965, formed a trio with Kind of Blue bassist Paul Chambers that recorded with guitarist Kenny Burrell, and from 1970 to 1978 the drummer partnered the operatically eloquent vocalist Sarah Vaughan. He worked thereafter with many leading younger musicians of the postbop generation including sometime Miles Davis saxophonist David Liebman, trumpeter Art Farmer, and pianists Kenny Drew and John Hicks.

Cobb taught in summer schools in Europe organised by Duke University, North Carolina, and for the New School for Social Research. New York, in the 1980s, worked regularly with Adderley’s cornetist brother Nat, and toured and recorded regularly in the US and Europe in the following decade.

Drawing from his New School student connections among others, Cobb formed the quartets and quintets he called Cobb’s Mob in 1998, performing and recording with them into the 21st century in lively postbop lineups including a young Brad Mehldau, the composer-guitarist Peter Bernstein, tenor saxophonist Eric Alexander, and the Marsalis family patriarch, the pianist Ellis Marsalis.

On the 50th anniversary of Kind of Blue, an 80 year-old Cobb memorably went to the UK with a group including the uncannily Miles-like trumpeter Wallace Roney and the saxophonists Javon Jackson and Vincent Herring – spurring those timeless themes with his old lazily springy dynamism, even if the renditions might have been a little lighter and funkier for some.

In June 2008, he received the Don Redman Heritage award from Michigan State University, and the following year a National Endowment for the Arts NEA Jazz Masters award. Cobb continued to perform and teach, aided by his wife, Eleana Tee (nee Steinberg), and daughters Serena and Jaime, all of whom survive him. He had previously been married to Ann Porter, who died in 1987.

He was often asked for the secrets of his light and buoyant drum sound and hair-trigger reflexes, but he had no magic formula. “The first thing is they have to love it” was his advice.

• Jimmy (James Wilbur) Cobb, drummer, born 20 January 1929; died 24 May 2020

* John Fordham is the Guardian's main jazz critic. He has written several books on the subject, reported on it for publications including Time Out, Sounds, Wire and Word, and contributed to documentaries for radio and TV. He is a former editor of Time Out, City Limits and Jazz UK, and regularly contributes to BBC Radio 3's Jazz on 3

© 2020 Guardian News

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

12 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Sweet Georgia Brown - Wynton Marsalis Quintet Featuring Mark O'Connor an...

2 notes

·

View notes