#Which is deeply appreciated especially at the time when many young Japanese people connected to it

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Digimon Adventure 02 Appreciation Challenge - Day 9

Day 9: Which family dynamic in 02 do you find the most interesting?

The Hida family dynamic is interesting because, as much as it’s determined by who is in the picture, it’s equally determined by who isn’t.

First of all, can I point out that Iori’s family is the only fully named family in 02? We don’t know the names of Daisuke, Miyako and Ken’s parents, but for the Hidas we get all of them. Grandpa Chikara, mother Fumiko, father Hiroki.

Iori comes from a rather traditional Japanese upbringing - his grandfather is a kendo master, his mother’s Japanese cooking is brought up several times (she’s apparently very good!), they even have a butsudan (Buddhist altar) in a room with tatami flooring. They pray to it and everything! Iori speaks in perpetual teneigo, or polite language, as expected of a boy raised in such a traditional environment. Additionally, Iori’s father and grandfather before him were also police officers. Thus, Iori’s strong sense of justice, and very black and white dichotomy of good and evil.

Iori loves and respects his family, and especially his grandfather - Chikara is the father figure in his life, not only teaching him kendo but also imparting wisdom to him on a regular basis. Fumiko, Iori’s mother, usually shows up in the context of Iori having to do something very important that he can’t talk about. When that happens, Chikara always bails him out, because it’s quite clear that it hurts Iori deeply to even think of lying to his mother. He has too much respect for his family to blatantly lie to them.

Part of Iori’s character arc is learning to open up to new possibilities, and evolving his sense of justice from its rigid form into something much more flexible and inclusive. This is something Chikara seems to have been actively working on throughout 02 - his lessons to Iori always emphasized that he should be true to himself and do what he feels is right, and also be flexible in heart and mind. Chikara obviously learned from his dealings with his son and his best friend how important this is. I think he was probably pleased that Iori chose his own path of upholding justice as a defense attorney.

And then there’s Hiroki. It’s amazing how a long dead guy can have so much presence in the lives of their loved ones. From the few silent flashback scenes you get of him, he seems like the kind of person that would light up a room with his presence, with that big encouraging smile and open laughter. And he was the kind of person to put himself between a person and a bullet to save their life at the expense of his own! No wonder he’s so missed, he was probably an amazing guy.

Even early on in the series, you can tell Hiroki’s absence weighs on Iori heavily - in episode 3, he cites his late father’s words as something he must follow (in that case, finishing a dreaded cherry tomato because he “shouldn’t waste food”). In the last arc, when faced with big moral dilemmas, he keeps asking himself, “What would father thing?” “Would Father do something like this?” “Would Father approve of what I just did?” Iori was a kindergartner when Hiroki died, and as such he doesn’t really know who his father was, really. He was just too young. He’s clinging to what little he can remember his father said, and tries hard to figure out what his father would think of him now.

I think that’s why he takes everything Chikara says so seriously and absolutely. No one in his life knows his father better than Chikara did; Chikara raised Hiroki, and taught him many of the lessons that he is now teaching Iori. In a way, to get an idea of what his father was like, he has to go through Chikara.

You’d think learning his father had a deep connection to the Digital World, something they both share, would make Iori obsess about his father even more. In episode 49, this knowledge does trap him in the illusion where he shows the Digital World to his father. But by this point, Iori has grown a lot. He has seen how clinging to the past can ruin a person. He knows he can’t show the Digital World to his father or ask him what he thinks about things. But he now knows he can introduce Armadimon to his mother, and he can work on understanding the people around him more and creating a better future. There are things in his life here and now that he can and should focus on. And that’s why, as much as it hurts, he is ultimately able to let go.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Multiplicity and what identification and representation means to Us

Madeline: I don’t remember there being many cool, attractive, and overall desirable but not fetishized (bye yellow fever) representations of Asian people in mainstream media while I was growing up in the early 2000s. The Asian media I did consume was introduced to me by my dad, so you can imagine the kind of outdated and endearingly weird characters I was exposed to as a kid. Think blind Japanese swordsman Zatoichi or humanoid child robot Astro Boy, both of which originated in Japan around the 60s. As for celebrities, I occasionally heard people talking about Lucy Liu or Jackie Chan, but only as defined by their stereotypical Asian-ness. My point is that this kind of cultural consumption fell into one of two categories: that of obscurity, which suggests that cultural objects are created by Asians for Asians (bringing to mind labels like “Weeb” for Western people who love anime), or that of hypervisibility grounded in stereotypical exoticism. You’d be hard pressed to find a film that passes the Asian Bechdel test.I didn’t discover K-pop until coming to college when I became curious about who my white friends were fawning over all the time. Since then, it’s been really neat to see how K-pop has become popularized as one of the many facets of America’s mainstream music and celebrity culture, especially when artists write and perform songs in Korean despite the majority of their audience lacking Korean language fluency. This suggests that something about the music is able to transcend language barriers and connect people despite their differences. Today it’s not uncommon to see Korean artists topping Billboard’s hot 100 hits, being interviewed on SNL, winning American music awards, gracing the cover of Teen Vogue, or being selected as the next brand ambassador for Western makeup brands like M.A.C. If you were to ask your average high school or college student if they know Blackpink, BTS, or EXO, they would probably be familiar with one of the groups whether or not they identify as Asian.What does this mean, then, for young Asian-Americans to grow up during a time when Asian celebrities are thought to be just as desirable as people like Timothée Chalamet, Zendaya, or Michael B. Jordan? What does it mean to see an Asian person named “Sexiest International Man Alive”, beating out long-time favorite European celebs? What does it mean for popularity to exist outside of the realm of the racialized minority and for it to build connections across minority cultures? Of course, fame can be toxic and horrible-- it is, at times superficial, materialistic, gendered, fetishized, and absolutely hyper-sexualized-- but I for one think it’s pretty damn cool to see people who look like me featured in mainstream American culture.I’ve found that throughout the semester, my understanding of Asian presence in America (American citizen or otherwise) has been deeply shaped by our discussions of identity politics and marginalization, another class I’m taking on intergenerational trauma, and my own identity as a Laotian-American woman. Recently, I’ve been thinking a lot about the similarities between American proxy wars in Korea (The Forgotten War) and Laos (The Secret War), both of which involved US bombing of citizens in the name of halting communism. Taking this class has challenged me to reconceptualize how we make sense of mass atrocity in relation to a pan-Asian identity, especially when contending with how trauma and violence can act as a mechanism for cultural production, and I look forward to exploring this more in my thesis.

Cyndi: K-pop is always just the beginning. Enough in and of itself, any interest in the genre at all reinvigorates the consumer to become more engaged with the world in which it exists. Two years ago, I got into a big, but in hindsight pretty silly, argument with my mom when I started going to a Korean hair salon (because of my K-pop delulus / Jennie prints) instead of seeing Maggie, our Vietnamese hairdresser who I can usually only see twice a year on our bi-annual visits to California to visit extended family. My mom told me the Koreans don’t need our money, they are already richer than we will ever be. Who are ‘the Koreans’? Who is ‘we’?? Is every person of Korean descent doing better than every person of Vietnamese descent in America? And #why is my mom being A Hater? Surely, sharing our identity as ‘perpetual guests’ in America should create some sort of solidarity, or at least, allow for transitory economic collaboration??? I give my money to white people all the time: to McDonald’s (Cookie Totes), to Target, to Swarthmore College.

K-pop cannot be the end. As much as I enjoy the music, the show, and the celebrities, I also know in my heart that the current international interest in K-pop will not last. As an almost perfect and perplexing exemplification of modern global capitalism, the industry will over-expand and thus wear itself out. I always see the subtle disappointment on my language teachers’ faces when they ask me how I came to take interest in Korean, and I have to answer ‘K-pop’, because that is the truth; that is not where I am at now, but it will always be how I began. It has become clear to me that this disappointment is not just a generational difference. Maybe these old people are jealous of pop stars like how I also have to question whether I am secure in myself when I see a 14 year old accomplishing things I as a 21 year old could never accomplish in my long life. I am coming to understand that part of their reaction comes from the fact that there is a fine line between cultural appreciation and cultural appropriation, that pop culture is ephemeral, but they have lived their lives as entirely theirs. Casual or even consuming interest for the parts of culture that are bright, and clean, and easy cannot ever stand in for true racial empathy, though it is where many of us start. Identity in K-pop is merely another marketing technique, but to the community of fans and lovers, it is something that is real, lived, and embodied. I find that looking at K-pop always brings forth my most salient identities in terms of gender, race, and sexuality. As much as female group members express affection and jokingly portray romantic interest toward one another, would it ever be accepted if these jokes were no longer jokes, but lived realities? Even if the K-pop industry itself did not seek to produce fan communities of this magnitude, these communities that have been founded in response to it are here to stay. Lowe argues that “to the extent that Asian American culture dynamically expands to include both internal critical dialogues about difference and the interrogation of dominant interpellations” it can “be a site in which horizontal affiliations with other groups can be imagined and realized” (71). A recent striking example is Thai fans’ demand to hear from Lisa on the protests -- a primarily youth-led movement against the government monarchy--going on in Thailand. Although she is, of course, censored and silenced on this topic, the expectation is still there; fans are holding their idols to a standard of political responsibility.

Jimmy: I haven’t really paid much attention to K-pop until working on this project. Sure, my cousins would do anything to go see BTS perform in person, but I didn’t care so much. Or maybe, I was just not saturated with the cultural zeitgeist. Whereas they live in the center of a cosmopolitan city which imports and exports, my hometown hums white noise. Increasingly, though, K-pop has entered into my life and the wider American cultural space. Now, K-pop tops the charts and is featured on late-night talk shows. Whether or not you are a devout follower, you have probably encountered K-pop in some form. It was not until I went to Swarthmore that I have “become” Asian American. Back home, my friends are primarily either white or Vietnamese-American. And even though I did recognize that I had an “Asian” racial identity mapped onto me, I did not consider it to be based on any politics. After engaging with and working within Organizing to Redefine “Asian” Activism (ORAA) on campus, as well as taking this course, I have a better grasp of what it means to rally around an Asian American identity. It is a way to organize and resist. Reflecting on my political evolution, I feel comforted and alienated by the cultural weight of K-pop in America. It is amazing to see the gravity of cultural production shift away from the West. And to have global celebrities from Asia is great. Yet, K-pop is limited as a platform for Asian Americans to create identity. What are the consequences when mainstream ideas about contemporary “Asian” culture are still perpetually foreign from America? Is Asian American community just built around transnational cultural objects like K-pop and bubble tea? Does the economic and cultural capital of K-pop held by its idols obscure or erase the heterogeneity and multiplicity of Asian Americans?

Jason: The first time I heard K-Pop was when Gangnam Style came on during a middle school social event when everyone is standing in their social circles doing their best not to be awkward when teacher chaperones are constantly staring at the back of your head seeing if any wrongdoing would occur. At that time, I could never imagine the K-Pop revolution that would occur within the American music industry. Anytime I turn on the radio it is only a matter of time until a BTS song will start being blasted from the speakers. It is crazy to think that K-Pop has become so widespread within American popular culture that mainstream radio stations in Massachusetts are so willing to play K-Pop, even the billboards of 104.1 “Boston’s Best Variety” are plastered with BTS, because they know that is what their audience wants. Eight years ago, during that middle school social Gangnam Style was more about being able to do the dance that accompanied the song rather than the song itself. This has completely changed as more and more people are finding themselves becoming devout supporters of K-Pop. This class and project have continuously been pushing me out of my comfort zone by engaging in literature that I would never have read and discussions that I would never have imagined participating in. I have even listened to more K-Pop over the past couple of weeks than I had ever before in my life. I was impressed by myself when a song by BLACKPINK came on and the radio host said here’s some new music that I knew that the song was from their first album that came out around a month ago. I am grateful that I have been pushed out of my comfort zone and “forced (by having to actually do the homework)” to engage in the material of the class. Who knows how long this K-Pop fascination will last in American popular culture, but I am glad that I could be a part of it rather than letting it pass me by and staying within my comfortable music sphere of country, pop, and British rap.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The reason why Kimetsu no Yaiba (KnY) is so well received by the Japanese (as such a remarkable phenomenon)

Written by Vũ trụ 一19九

Translated by Meownie

Proofread by Alice

Everyone knows that just in a short time, KnY has almost occupied the spotlight in all fields, everyone talks about it, the number of sale in goods and comics is enormous, both of them are sold out, etc.

Following my own curiosity with this phenomenon, as well as my existent love for the original work of Kimetsu no Yaiba (the manga), I dug into this issue because, in Japan, every trend has its own root.

Taking aside all the numbers of sale or whatever, which have been analyzed by a lot of people, as I’m not a data person, I will look into the content, the storyline and the core of this phenomenon in reference to many sources and comments about KnY coming from people in this country.

Many of you say that KnY is only at an average level compared to the manga/anime general standard. Then let me tell you what the extraordinariness that an ordinary series can do.

Apparently, there are always conflicting opinions, the Japanese community is no exception. However, the pro-KnY still grows bigger and there is no sign of softening. And here are some positive comments for the success of this series.

1. The anime is excellent in graphics, sound effects, the plot details are neatly arranged, easy to understand and heart touching

Cannot ignore the fact that the anime has built up the KnY’s success. Ufotable made the anime so excellent, especially in terms of visual and sound. It makes the story more approachable and the audience more empathetic to it.

The anime is a contribution to KnY’s greatest success. But many seem to be mistaken that only thanks to the anime did KnY succeed like that?

If the anime succeeds, viewers will be more interested and curious about the main storyline, so they will try to read the original manga. But if the manga was a trashy series, they could stop buying/reading it and just wait for the anime, right? So what is the reason behind the boom in the KnY manga sales until the beginning of this year, and its rankings which are always in the top 3 of WSJ magazine?

Sometimes ago, I did a research and presentation about the anime/manga industry along with the cultural reforms that contributed to the revival of the Japanese economy after the war. In that research, there was a detailed analysis of the connection between the original manga and the anime adaptation as a yin-yang relationship. They are all for the sake of the original publisher and the animation studio, so one will complement the other.

Manga is a product which only attracts a certain group of people, it is not so popular since there are homemakers, young children, the elderly, and people who are not fond of reading, those who do not find manga interesting. But anime is more universal and extensive, as you know, Japanese families often buy a TV to watch the news or to entertain on weekends. The anime is only about hearing and watching, so anyone can access it. When a manga is adapted to an anime, it brings the original closer to the people, and furthermore, hopefully, make it to the big screen.

On the other hand, the original manga is the base, the soul of the work, so readers feel more excited when waiting for each chapter be published in the magazine, waiting for the changes to be re-compiled each time for a new volume. So the manga contributes to increasing a large number of consumers. Of course, buying DVD-BD is definitely more expensive than buying the volume.

As a result, success is mutual support between manga and anime. And making an anime warmly-received is not that easy, the good base of the manga should be credited and vice versa.

I will talk more about the content of the original in the second reason. But initially, it is necessary to distinguish: not all good originals are well-received and vice versa. Everything’s got its relative value, in which context and timing play a role.

2. The charisma of the protagonist, Tanjirou, a young boy trying to save his sister; With a warm-hearted characteristic, his story is not about “revenge” but “restoration”

11 over 10 people being asked, answered that KnY’s success comes from the main character. This is yet another compliment to the editor who directed the way for KnY, Katayama-san, for orienting to make a more gentle, kind Tanjirou, eliminating the brute in the original portray.

Firstly, it is appropriate in this day and age to have a main character who is kind and gentle, which replaces for the old MC portray, who was noisy, hot-tempered and “brainless”. Secondly, it suits the plot that Croc-sensei wants to shape, a story about a boy finding a way to help his sister to be human back, about family love and values. A character who is kind-hearted, with a loving and protective care towards his sister, is more suitable for the readers. On the other hand, the story which does not turn to revenge, but to the path of helping the younger sister to be back to normal and the main character with his sympathy for the tragic fate of the demons makes the readers/audience impressed and pleased and feel like they’re saved and soothed as well.

Tanjirou takes the crown not only because of his kindness but also the determination and strong will, as he does not forgive the crimes committed by the demons. Yes, he is surely sympathetic to them but they all have to pay for their guilt. Therefore, our main character is always consistent from the beginning to the latest chapter and that personality has never wavered.

Not to mention, there is an indispensable point in the MC of WSJ, that they all constantly try their best and do not deny what they are given.

Tanjirou carries all of those points of a MC of WSJ but still reaches many different types of audiences. Lots of mothers want their children to watch KnY so they can show more love towards their families and younger sisters like Tanjirou does.

That is the greatest success of the series. And that’s the reason why the media team take the slogan “Japan’s softest slaying demon story” to PR KnY successfully everywhere.

3. The next detail making the manga a big hit is the consistency in story theme, which is “family”

As everyone knows, the shounen mangas in general and ones in the WSJ, in particular, all discuss the solidarity. But there is a theme in KnY which reaches the audience more easily and widely: “family”. This is the affection that almost everyone can receive and understand.

The modern social situation of Japan, an Asian country, where even though family love is appreciated, the family warmth have gradually disappeared. Children who reach the age of independence and are out of a parent’s guardianship are able to easily leave the country, live independently and rarely return to visit their family. Here in Japan, the proportion of the elderly, late marriage and single people is increasing sharply. The rate of living alone now in Japan is very high and alarming. So a series about love for parents and siblings in the family is like warmth for this cold society.

From an old man’s POV who are living here: “I feel wholesome and nostalgic of the days I spent with my family, feel warm when watching KnY, and how Kamado siblings protect each other.”

The elderly do not pay attention to whatever trend is, they just watch TV basically to enjoy good work and support it.

The family theme is easy to empathize and to be delivered, so even the kids can watch and enjoy it with their mom. There are some POVs from some mothers, telling that their little kids love KnY and hoping they love their family just like the characters in the story do.

Although the context in the story is dark, the path of the story, the way expressing the theme of Croc-sensei is easy to understand, which brings in the light in the darkness and makes the number of readers become more diverse, makes the work more popular and universal.

Tbh, KnY is still very “bright” compared to many series in Japan, so a lot of children can approach this manga. Moreover, there are many cute characters and details in the story.

4. The gap between characters makes a unique way in Gotouge-sensei’s character creation

The Japanese love the interesting dynamic, and they define it as “the gap”. The more surprising gap a character has, the more popular that character is. Briefly, it is, “not judging the book by its cover”.

The first example is the character has the same or sometimes, more popularity over the MC in Japan, Zenitsu. They don’t usually like noisy guys, but because Zenitsu is a cool character and has an interesting gap, which attracts readers. Apart from his noisy, cheerful behaviour, he is a serious, thoughtful and experienced person who accepts pain and loss just like an adult.

Then there are countless characters with interesting gaps like Inosuke, Giyuu, and the Pillars. Crocs-sensei’s characters are not many, compared to a shounen series. But this is the mangaka’s intelligence to choose the strengths outshining the weakness. Although sensei does not create many characters, sensei has built the base for the character very well, for the impressive appearance of each one and makes the readers/audiences remember them deeply.

The proof of this success is that KnY goods are sold out with every character, from the most to least favourite.

5. The story is clearly set in the Taisho era, coming with its proportional design and architecture that makes the reader accessible

Taisho era is neither old nor new. The people witnessing the change in that era are still alive. But Taisho was the period of transition with the insecurities in the society. So the creation of a fantasy battle with the chaos between demons and people is extremely suitable for the Taisho era.

There are billions of reasons, like the previous parts, here would mention only main points. KnY is simply a normal series, but it is the ORDINARINESS that pulls out the EXTRAORDINARINESS and delivers those CLOSER to the readers. And this “extraordinariness” is not something that a so-normal series can do.

I love the welcoming spirit of the Japanese, they always appreciate new things, yet never forget to maintain and preserve the old ones.

Because it is a constant rule in development.

The same thing applies for the WSJ: increasing sales for the currently published series, at the same time discovering and boosting new titles. And the latter is more important than the former. But they still welcome new series that inherit such values in shounen genre, the magazine would develop the series open-heartedly if it is deserved.

I am also a fan of shounen and WSJ, I think KnY totally deserves the success it has achieved now.

I also hope it is kindly well-received because Kimetsu no Yaiba was made not to be a replacement, not to take any seats from any series. It is simply a shounen legacy in WSJ magazine. You would know that the spirit in shounen manga highly values this “inheritance” characteristic.

#Kimetsu no Yaiba#manga#anime#tanjirou kamado#kamado tanjirou#nezuko kamado#kamado nezuko#giyuu tomioka#tomioka giyuu#zenitsu agatsuma#agatsuma zenitsu#inosuke hashibira#hashibira inosuke

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Offering our voices to honor our ancestors

Protecting What is Sacred: Our land, Our water, Our hope for a better future

I preface this with an apology because these thoughts were scribbled in the wee hours of the morning when I couldn’t sleep and thus this lacks the clarity I’d hoped for in sharing some of what’s been weighing so heavily on my heart. That said, some folks have nudged me to share some of these reflections and it felt important to start somewhere in voicing how my heart connects these dots. So, below are some meandering thoughts as I reflect on Obon and how it threads us together with our past, present, and future... and ultimately each other...

In less than a month, I will be returning again to my place of birth - my maternal ancestral homeland in Okinawa - to visit with family and friends and to pay my respects to those who came before us. It’s been 2 years since my last visit and it will be the first time I am able to speak to my beloved grandmother in Uchinaaguchi - one of Ryukyu/Okinawa’s indigenous languages which I’ve been studying - to thank her and share with her my ongoing studies here in Hawai’i as I continue working to record our family’s stories, deepen my appreciation and understanding of our indigenous Ryukyuan history and culture, and create resources to share with fellow Uchinaanchu/Okinawans living in the diaspora across the globe. My grandmother is 96 now and has been my trusty compass since as far back as I can remember - back to my earliest childhood memories in Okinawa. Her visits to see us once we moved to North Carolina are highlights of my youth. Even when we moved to the states and we were thousands of miles apart, I could still always feel her love and would sometimes look out across the ocean in the direction of Okinawa, trying to picture her and the rest of the family there, hoping that I too could cultivate the kind of love she shares which could be felt across time and space.

It is not coincidental that my upcoming trip to Okinawa next month was planned to coincide with Obon and, as such, will involve returning to my grandmother’s village in Kijoka, Ogimi where some of our family tombs (ohaka) are located. I have yet to find the words to express what it means to me to be able to revisit the same land where generations of my family have lived and where we continue to return, year after year, to offer prayers and gratitude for our village, our ancestors, and all the sacrifices they have made for us. It is something to treasure all the more since there are many who are unable to do so, especially since I know many in Okinawa whose family tombs were destroyed during WWII or were paved over for US military bases under US occupation in the aftermath of the war.

I remember before taking that trip back to Okinawa two years ago, my mom had told me on a number of occasions that visiting our family tombs to pay respects was something she had always wanted us to be able to do together. I was never able to line up the time and resources to return for Shimi but she’d made clear that the timing wasn’t even what was important - just that we made the time. And I vividly remember when I finally had the opportunity to join my family to do so as an adult during that trip, time seemed to collapse onto itself. I could feel an overwhelming connection to the past, present, and future as a continuum extending well beyond the 5 generations of our family represented in the gathering that day.

One of my young nieces and I tidied up the area and altar together as other family prepared the offerings we brought. As we did so, I recall my grandmother commenting how happy the rest of the family (meaning our ancestors) must be to see my niece Sawana and I there together, putting such love and attention to detail in cleaning and helping with preparations. Hearing this as a gentle breeze passed, it certainly didn’t feel like we were alone. After our prayers and offerings, we found a nearby spot to enjoy our family picnic. Sitting in a circle, I looked around at my family with the sweeping views of the ocean behind them and my eyes welled up with tears of joy as I laughed and we talked story, savoring the beauty of that moment and seeing it similarly reflected on their faces. As I think back on such moments, my hope is that each day, I find a way through actions to express how much I cherish these gifts of love, tradition, and hope for a better future that have been and continue to be passed forward through my family and communities.

As many of you know, my return to Okinawa two years ago was something I was apprehensive about in many ways - despite longing to return since I was little - and I am beyond grateful that it was ultimately a deeply healing and transformational experience. During this trip in August, I plan to return to Shuri were my grandfather’s family is from and offer prayers and gratitude for my grandfather’s family at their hakas too, in hopes of contributing towards intergenerational healing within my family. After all, the history and stories of my grandfather’s family are part of what motivates me to do some small part to preserve Uchinaaguchi and not only Ryukyu/Okinawa’s history and culture but also our family’s legacy as part of that living history. (Some of you already know why I’ve not grown up close to that branch of our family but for others, suffice to say my grandmother is a strong, fiercely loving woman who would always stand up for what is best for her children...no matter the self-sacrifice involved.) I mention this because history is never clean - often filled with pain, conflict, and contradictions - but we shouldn’t shy away from certain parts of our past because of that; those parts shape(d) us too and can be part of how we learn, heal, and ultimately reclaim our futures. This is true even of my father’s side of the family - direct descendants of both Reverend John Robinson “Pastor of the Pilgrims” who sent his congregation over on the Mayflower as well as the Mississippi band of Choctaw who were nearly wiped out by the arrival of these European immigrants. I often think about how to hold these complicated truths and seeming contradictions of our past and/or different perspectives and the importance of doing so even as we face such situations in the present...

To Honor My Ancestors Is to Honor All Our Ancestors

Here in Hawai’i, Obon festivities have already begun as there are literally bon dances held every weekend from mid June through August. To write about some of my experiences and reflections thus far (including the way Obon is celebrated here versus back in Okinawa) is a topic for another time. I share this as context though because as a member of the Young Okinawans of Hawai’i (YOH), we share our song, drumming, and dance as offerings to our ancestors and to communicate with them, just as Okinawan eisaa was traditionally intended for. It is not entertainment for the crowd that gathers but, if anything, an invitation for the community to join us in this collective offering for all our ancestors. Whether it’s the little ones that find their way towards the inner circle around the yagura to dance by our side during our bon dances or the young ones in my family and communities, I hope that any child I ever interact with can feel and cherish the gifts of our uyafaafuji (ancestors) and learn to manifest that gratitude with their voices and in their actions, guided by what’s in their hearts. I do not take lightly the moments like this weekend when a group of little kids surrounded me and looked up wided-eyed and open-hearted, eager to watch and follow in my footsteps as we sang and danced around the yagura together. When I heard one of the littlest ones next to me begin to join me as we called out with our heishi, I’m not ashamed to admit I got a little something in my eyes.

In sharing the history and meaning of Okinawan eisaa and inviting friends to join us for Bon dancing, I have found myself often clarifying for folks that when I say I dance and sing for “our ancestors” I am referring collectively to the people we are tied to through our connection to place as well as our families of origin which we are connected to through blood and other familial connections. So, when I sing and dance here in Hawai’i, I too sing for the kanaka maoli - the indigenous Hawai’ians and the Kingdom of Hawai’i. I am aware that in moving here to study and build community with the Asian plurality and fellow Uchinaanchu here, I am also a settler. So, I strive to listen and learn from not only the elders I meet but also to their ancestors who sought to protect this land and its precious resources. That comes with inherent responsibilities to listen, learn, and take heart when I am asked to speak out as someone whose ancestral homelands were similarly colonized, whose people also endured physical and cultural genocide, and whose democratic voice and right to self-determination is still being ignored. As shimanchu whose past have so many parallels, I believe our hopes for a better future and collective liberation are also bound together. So too, I feel a deep responsibility as someone raised in the US and with the relative privilege that comes with that, even when so many Americans have made it clear that they will always see me as an outsider. It is all too clear to me how these things are all interconnected.

So, this weekend, I danced not only for my ancestors back in Kijoko but also for those in Henoko, Okinawa where my parents met and for the community there who have been dedicated to protecting our one ocean in the face of joint US-Japanese military construction in Oura Bay. My heart also joined the protectors here in Hawai’i who have been gathering at Mauna kea to prevent the desecration of that sacred land. I lit candles and held in my heart the memory of my paternal grandparents and their families. My heart too, also sang out for the children who are locked up in cages across the US for the crime of having a family who dreams of a better future for them but come from another side of an imaginary line. I carried in my heart - the heart of a first-generation immigrant to the US - all the families of refugees, asylum seekers, and immigrants who are dreaming for a brighter future.

I might not have all the answers for how to re-envision the future to be a better one for all, but I’ve seen enough to know one thing we have to do is speak out to say that this current path we’re on sure isn’t the way.

To honor my ancestors is to honor the preciousness of all life. Nuchi du takara. So, to honor all my ancestors, I offer my voice to honor the ancestors of all of us - to acknowledge our interconnectedness - and to share our ancestors hopes of a better future for us all. In sharing my voice as an offering, I also extend an invitation: Let us never give up the hopes and dreams of our ancestors. Instead, let that be what unites us as we protect what is sacred.

Rise for Henoko! Aole TMT! Protect Our One Ocean! Kū Kia`i Mauna! Never Again is Now! Together, We Rise!

p.s. I recently shared this music video but felt it was apropos to share this song again here with a gentle request to take the few minutes to watch and reflect:

youtube

#NuchiDuTakara#AlohaAina#RiseForHenoko#AoleTMT#KuKiaiMauna#ProtectOurOceans#ProtectMaunaKea#ProtectWhatIsSacred#NeverAgainIsNow#OurCollectiveLiberationIsBoundTogether#TogetherWeRise#Uchinaanchu#Obon#bon dance#Bon udui#eisaa#ancestors#hope#shimanchu#GovernorIgeDoesntSpeakForAllOkinawans#Ryukyu#Kijoka#Henoko#indigenous#indigenousrising#AllyIsAVerb

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Q&A with illustratai (Tai Yoshida)

Q: How and when did you discover you wanted to be an illustrator?

A: When I was little, I spent most of my time drawing and coloring, so my family really encouraged me to explore that. Since then, I haven't put my pencil down and that everyday practice and support from my family has really helped me to grow as a young self-taught artist. I wasn't interested in any subject except art and design classes in school. I also started working part-time at a restaurant when I was 17 and that made me realize... that I found so much freedom and self-appreciation in not working for someone!

So when I had to decide what type of college/major I wanted, choosing an art school and pursuing a degree in Illustration - especially going freelance, so I can be my own boss and make my own money doing the one thing I love - just felt natural to me. I know freelance isn’t easy, but I’m determine to make it work!

Q: How did you figure out that using an app on the iPad Pro was the right way to go about creating your art? Are there other mediums that you mess around with?

A: I actually use an iPad Pro to draw because I was scared to commit to a professional Cintiq drawing tablet at the time! I'll definitely invest in a Cintiq in the future, but for now I’m quite comfortable with my iPad. Although, my personal con to drawing digitally is that ever since I switched to it, I unfortunately rarely ever use sketchbooks anymore and I miss that.

Art school has really exposed me to work with different mediums I was never comfortable with like: ink, charcoal, watercolor, oil paints and gouache. My favorite class I've taken so far was a color class where I was taught to paint with gouache. I got accepted into my university's spring art show for that class' final painting assignment, which really made me fall in love with it. I plan to make some illustrations using gouache in the future.

Q: What inspires you to create new pieces? How do you begin your creative process and how do you know when it's finished?

A: Most of my inspiration comes from women and fashion. I'm really influenced by ethical fashion, indie boutiques, anime, old films, and Japanese fashion magazines. Of course social media is a huge influence as well. My eyes are always moving and absorbing other artist’s work so I can improve my own.

This might sound extra, but I begin by getting ready and dressing up like I'm going out! I feel like I create my best work when I think I look good and confident. I then begin to think about the composition of the piece, then the colors, mood, and so forth.

I honestly never know when a piece is finished. Even my current "finished" illustrations could have a few more touches. When I was younger, I would throw away so many drawings because I'd just hate how it looked the next day. It's like the feeling of looking at a nice selfie too long and then you start to see all these imperfections and then in the end you just don't like that selfie anymore. I'm never satisfied with my work but I know that's just my weird anxiety filled brain talking so in the end I just accept it.

Q: I love that the theme of your work revolves around girls. Is there someone specific that you base them on or is there a reason for this?

A: As an Asian American woman, I rarely (or never) saw myself in art or the media. My goal is to celebrate girls forever though my illustrations and draw real life women! The thought of one day bringing a bit of happiness, confidence or inspiration into a girl like me, who is vastly underrepresented, really lights a fire under me to keep creating. I deeply appreciate anyone who feels a connection or just likes the way my art looks though!

I sometimes draw friends or ig girls as practice, but I'd never sell it as a print or something without their permission. Other than those drawings, all other girls I illustrate are not based on real girls… but they could be real girls! (if you catch my drift.)

Q: Describe your art style in one word.

A: One word?! That's hard… maybe, “Vivid!”

Q: What is your favorite piece you've created and why?

A: My favorite piece is definitely my "Boss" girl. I was struck with inspiration after watching the film Akira and immediately drew her right after. She wears a periwinkle pullover with a crossed out pill logo smack dab in the center of her back. The fact that I didn't draw her face really lets the viewer and myself wonder what she looks like. She's quite mysterious. Plus the fact that she's positioned in a "front double bicep pose" (thank you, HYPERLINK "http://bodybuilding.com/"bodybuilding.com) makes her give off a powerful and confident aura. I wanted her colors to be cute and bright to balance the striking pose. Her motto is "Even though I look cute, don't f**k with me." I literally want her to be my best friend. We'd stomp around the city in our black boots together and beat up any cat callers!

Q: What do you feel when you look at your pieces and what do you hope other people feel?

A: In real life, I have multiple anxiety disorders, so I often battle with negative and self-depreciating thoughts about me and especially - my work. This issue is quite debilitating for me because it often seems like all the hard work I do is for nothing or is just unnecessary. So I feel really proud of myself and genuinely happy when I look at my pieces. My girls are simultaneously the best parts of me and also everything I aspire to be. I hope other people can feel the same sense of joy when they look at my work.

Q: You have recently launched your work with Mori Hawaii - what a huge milestone, congrats! What are your goals for the future, as an artist and/or just a human being?

A: Thank you! It’s been a dream come true to be able to sell my work in one of my favorite stores on O’ahu!

My #1 goal is to finish college and get my BFA in Illustration.

In terms of my personal art career, I want to be more active on Instagram to get myself more exposure as an artist and also take more commissions.

As a human being, I’m working on being more aware of how the things I buy are made. Instead of going for fast fashion, I’m purchasing clothes from ethical or local brands and thrifting. I’m also considering how much use I can get out of an item or if that item can go with many other pieces in my closet before purchasing. Just trying to make the world a better place one step at a time by being a smarter shopper.

Q: Who has inspired you the most?

A: My biggest art inspirations so far are definitely Hayao Miyazaki, Kelsey Beckett, Audra Auclair, and Leslie Hung. These artists never fail to push me to work harder at my craft.

Q: What advice would you give to someone who is in a creative block?

A: What really helps light a fire under me to draw is watching other people draw. I highly suggest watching speed-paints or drawing tutorials by your favorite artist. When it comes to being motivated, nothing beats seeing someone you look up to work hard! Aside from that, when I feel like I'm in an art block, walking around or just gazing out of the bus, train, or Lyft in San Francisco helps to open my eyes to new color schemes and settings for my girls.

Q: Lastly, what are three items you could not function without?

A: Not surprising but I could not live without my phone! It's how I connect with my loved ones, stay organized, and where I turn to for inspiration on-the-go. I'm on it all the time.

I can't live without a digital drawing tablet anymore! It really has changed my life and has brought out the best work in me. Technology is already taking over the world and the art industry, so I have to keep up.

Lastly, I can’t function without dogs! I know they aren’t an item, but I think I’d go mad without them. There was never a moment where we were dog-less in my house. I have two little chihuahua’s waiting for me at home right now - who I absolutely adore. Being without them in San Francisco has caused me to have this urge to want to pet everyone’s dogs here. Literally catch me on the street creepily staring at someone’s dog.

Check out Tai's Instagram page:

instagram.com/illustratai

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Which arc do you think best represent Gintama? Also, if you were to recommend any episode(s)/arc(s) to somebody who's never watched Gintama before, which would it be?

I don’t know if picking just one arc as a representative will suffice because another arc will deliver a different impact. I know it sounds like a cop-out, but it’s true – there are too many great arcs that embody the spirit of Gintama.

But for the sake of your question, I’ll select five candidates. I hesitate to choose anything beyond Shogun Assassination arc because that was the point of no return and the arcs that followed are all interconnected and quite dark in comparison to the earlier arcs (minus Yoshiwara, which I feel is on par with them). It’s not that Gintama can’t be dark and depressing, but I think in order to choose a representative arc, there has to be a balance of comedy and drama with a final wrap-up at the end. The arcs after (and including) the Shogun Assassination arc are quite emotionally heavy and depend on each other for story continuation.

Continued under the cut (along with my answer to your second question):

BenizakuraI know most people are tired of this arc, understandably so. I’ve seen/read it enough times already and had hoped the live action film would venture into original but Sorachi-approved/penned territory. Nevertheless, the Benizakura arc remains a vital part of Gintama for several reasons:

It’s the first arc in which the potential deaths of the Yorozuya are more real possibilities than ever before.

It introduces the main antagonists (although Takasugi is introduced early on), the Kiheitai, who will continue to have a significant presence in Gintama.

It is the first lengthy arc, surpassing three episodes/chapters.

It shares important information about Joui3, and, contrary to popular opinion, the Joui4 have always been an integral part of the story because of their connection with Gintoki, the main character.

Besides those reasons, I rather like how Benizakura’s subplot concerning the Murata siblings is introduced and wrapped up by the end with Gintama’s signature style of minor characters having more depth than first glance reveals. Their story and how Gintoki affects their lives serves as a prime example of the Yorozuya’s impact on everyone they encounter. Furthermore, this arc has the perfect balance of drama and comedy, which is why I consider it a candidate for best representative arc of Gintama.

Shinsengumi Crisis

My all-time favourite arc centered on my most favourite character, but I didn’t choose it for those reasons alone. I selected this arc because of the focus on the Shinsengumi as main, recurring characters while still having some focus on the Yorozuya. Additionally, this is an arc that centers on an antagonist who undergoes development and redeems himself by the end. We don’t really have that in the Benizakura arc except for Tetsuya, but he cannot really be compared to Itou and Bansai. Gintama is known for its antagonists rarely staying the same in an arc, and I think Shinsengumi Crisis is one of the best examples.

This is also one of those arcs where the Shinsengumi benefit from the Yorozuya’s assistance, but also don’t necessarily need them for character development, because they do that all on their own, for the most part, due to the strong bond between Shinsengumi members. The Yorozuya are partly there because Hijikata has requested for them to protect the Shinsengumi in his place (indicating his desperation for and devotion to the Shinsengumi, Kondou especially), and they do play a part in his breaking the curse, but beyond that, Kondou, Okita, and Yamazaki act on their own and, eventually, so does Hijikata. The primary focus is Itou, Hijikata, and the Shinsengumi and how they handle their own internal affairs.

Gintoki takes more of a side role in this, but returns to the main spotlight when he confronts Bansai and the inevitable link to Takasugi (who we know by now one of the main driving forces behind the series and someone deeply connected to Gintoki). Before that, they were charged to protect Kondou and then Hijikata, both on request, but, of course, nothing ever goes as planned. Gintoki, then, is given secondary reason to be in this arc when Bansai forces him to fight. After that, they are mainly observers helping in the best way they can for the greater good.

I don’t have anything else to add except that it makes a good standalone film, and evidently, the anime team thought so as well with the release of the film versions.

Ryugujo

This must seem like an odd choice given the fact that I rarely see it listed among fan favourites. It’s probably because none of the popular characters are in it save for Gintoki, Katsura, and Kagura (and even then, depending on which corner of the Internet you frequent, people don’t appreciate Gintoki and Katsura’s camaraderie as much, I find). While the arc’s plot is taken from Japanese folklore, the execution may seem a bit silly for some, but it’s in true Gintama-style.

Moreover, this is one of those arcs that doesn’t have any effect on the main, overarching plot line that I can discern, but that doesn’t make it less important. This is where people fail to distinguish between plot and character-driven stories, forgetting that Gintama is a mix of both and insisting that this arc or that character is unimportant (talk about missing the entire point of Gintama) to the story as a whole. Sorachi tells these stories for a reason and the reason in the Ryugujo arc is a lesson on true beauty. It’s a simple lesson, yes, but one that still needs to be taught time after time, because humanity still prioritizes the condition of their face over their soul. It’s only natural, but the Ryugujo arc emphasizes that you will have everlasting beauty if your soul is untainted, whether you’re young or old. Appearances change and fade, but your actions and words will have a longer and stronger impact on people and life in general.

Gintama is, essentially, a series of lessons and morals (as evident by chapter and episode titles that aren’t adages) and choosing to do the right/best thing, whatever the situation is. We see this constantly, especially through Gintoki as he strives to live the best, most peaceful life in a post-war era. For example, in this arc alone, they all could have left Otohime to her fate after what she did to them, but they didn’t; they fought to save her and give her another chance at life. Taking the higher road is a noble deed, and in doing so, they freed a person’s soul from its own cage. Thus, Otohime can live her life unburdened and age gracefully with true beauty behind her smile.

Therefore, I think the Ryugujo arc is one of the best examples of Gintama’s lesson-oriented stories that also gives the rest of the cast a chance to shine.

Courtesan of a Nation

This is an arc that plays a larger role in the overarching plot, but can still stand on its own without the next arc needing to play sequel for it. This arc uses more of the newer characters, like Tsukuyo, Isaburo, Nobume, and Oboro. It reveals more of Gintoki’s past. There’s action and comedy at the right moments. Lastly, like its predecessors, there are minor characters whose personal stories will draw you in, and I’ve got to say – the one featured in this arc gets me every time when the ending credits roll into view with that SPYAIR song.

Overall, this arc really has the atmosphere of an epic and tragedy all at once. There is real danger presented, as they grapple with government factions this time around: authoritative figures with the power to damage your reputation, destroy your career, or have you executed. When you start messing around with the higher-ups, it isn’t going to be easy to walk out the door unscathed.

This arc also brings to light the many conspiracies and treason-laced schemes that tie back to Gintoki more than one initially thought – and certainly more than he wanted it to. It’s easy to forget that Gintoki is a war veteran and considered, by the current government, a national criminal, as well, for his part with the Jouishishi. He is as much a wanted man as Katsura and Takasugi are.

Lastly, it’s an arc that shows nothing will stop the Yorozuya and their allies from doing what they perceive to be the right thing. It’s exciting to watch people who don’t normally work together do just that: the Shinsengumi, the Mimawarigumi, the Hyakka (Tsukuyo), and the Yorozuya. They all have a common goal in mind and view Shige Shige as the better and more just Shogun.

Kabukichou Four Devas

Finally, I would choose the Four Devas arc as a candidate for best representative arc because it’s a story of people from all walks of life coming together to protect what’s important to them. And that’s Gintama in a nutshell. Several arcs after this one, Gintoki speaks of gaining thousands of allies and this is where we see many of those allies first come together as a single force well before the Shogun Assassination and Silver Soul arcs. It is comprised of characters we meet in the first fifty episodes alone (including some from later on). It shows that people have not forgotten what the Yorozuya have done for them, and they want to give back in whatever way they can. It shows that Gintoki and the Yorozuya are not alone in the battle to save the Kabuki district as part of Otose’s faction.

Indeed, it also focuses on Otose, her past, and her bond with Gintoki. Most of the time, Otose is just in the background, rarely in the spotlight but always there at important moments when she needs to be. But here, she plays a key role as we are introduced to Jirochou and Pirako, plus the reintroduction of Saigou and Kada. Additionally, at the end of the arc, there is a brief story line with Takasugi and Kamui, which is crucial for the remainder of Gintama, as the Kiheitai and Harusame alliance will later prove.

Overall, it’s a great arc for showcasing the strength and bonds of multiple characters, major and minor. As stated by Gintoki himself in the Kintama arc:

“The main character of Gintama is every last idiot alive in this show!”

Now for the second part of your question: which arcs/episodes would I recommend for newcomers?

Well, it’s something I’ve wrestled with for over ten years: how do I get people into Gintama? People have watched those infamous first two episodes and ditched it. Others think it’s just comedy, parodies, and gags with no substance. The reality is that some people just won’t be able to understand what Gintama is, won’t come to love it as much as we do.

I’ve learned to accept that. I pity them; I feel sorry that they miss out on superb storytelling that leaves many other WSJ series in the dust. I think they’ve made a big mistake and are generally wrong about everything they perceive Gintama to be…but that’s their choice. No matter what I say or recommend, it won’t be enough for the newcomer, because they’re going to judge it by their own standards and decide if they want to continue or not, regardless of how much I hype the series up.

I can’t really recommend the serious arcs yet because they would be walking right into the middle of a story without really knowing anyone. Jokes will feel like inside jokes. They might find themselves constantly referring to a character chart to remember names, faces, and reasons for why they are way they are. They’ll miss little details that come into play later. Yet, I also hesitate to recommend just a single episode or comedy-centric arcs, because then the newcomer will judge Gintama by those alone and miss out on the equal quality of the drama arcs.

I think the first two episodes can be freely skipped for later viewing. Strictly speaking about the narrative, it is too much to introduce a ton of characters at once; it overwhelms the viewer, as they scramble to memorize everybody. Starting at episode 3, which is chapter 1 of the manga, is a better idea. One may also utilize a filler list to avoid those, but you can barely tell which is filler material or not.

However, in the end, I have to say…just watch it.

Watch it and understand that the comedy makes Gintama as much as the drama does. There’s no need to place either one on a pedestal. All the episodes leading up to the first serious arc and the ones that come in between can be just as worthwhile. Gintama has an overarching plot, but it’s also a slice-of-life series in that it doesn’t limit itself to common tropes of a shounen series. You can’t narrow it down to a single genre, either, because it has everything (although some by parodies). There are great comedic and dramatic moments in every episode, and in order to appreciate the rich diversity of the characters, it’s best to just take Gintama as it is.

And, honestly, you have a list of episodes available on several web sites with brief summaries. You can choose what you want to leave for later and focus on what sounds like it’ll be hilarious or extra interesting for you. I just don’t recommend watching the serious and longer arcs out of order, because they reveal necessary information for subsequent arcs.

Once I was a newcomer, too. I didn’t know what I was getting into except that I liked the style of comedy presented by early chapters of the manga. I took my time watching the anime, never knowing what was ahead within the serious arcs, that Gintama would grip me emotionally like few series have. I don’t like to call it patience here, because the fact that I watched every single episode doesn’t mean I was waiting for it to “get good,” as many people say and ask. To me, Gintama already WAS good. It was something different from the usual shounen fare. I didn’t need to wait at all, and before I realized it, I was already heavily invested in the characters that I loved seeing them in all kinds of situations.

Plus, I think today people have shorter attention spans with a desire for instant gratification – so much that they forego story build-up, wanting to get to the action quicker or whatever it is they’re looking for. There’s little appreciation for the art of storytelling nor all its subtleties (something Sorachi does in spades).

Gintama isn’t 500+ chapters or 300+ episodes of endless quests and final bosses and power-ups. If you want that, go watch/read something else. But if you want unique and developed characters, a female cast that’s treated with more respect than other series, hilarious comedy, historical parallels, and intriguing drama plots, then embrace Gintama and all its quirks. You won’t regret it. I certainly don’t. There’s a reason Gintama is consistently highly rated across a number of different web sites and ranking systems. Take my word for it.

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

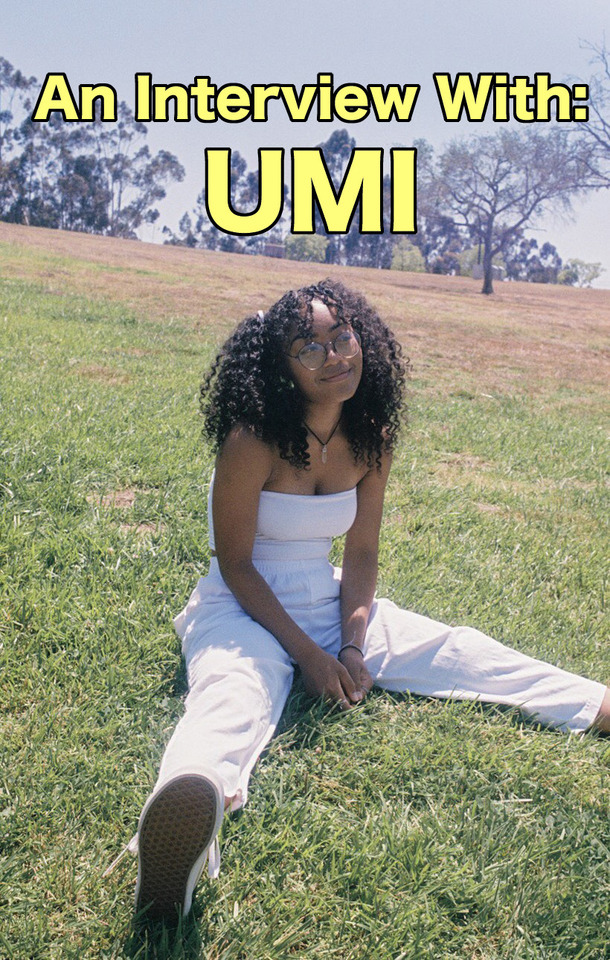

It’s common for music to be associated, at a base level, to emotion. While true that sound attaches to the idea, it is a step further to explore spirituality, and therefore the life’s intricacies as a whole, through vibrations. This is exactly the new step Umi is introducing to the listening world, building spaces of introspection as well as understanding.

While young, she uses her life and surroundings to explain much of what doesn't seem to have an answer. Her sounds are beautifully simplistic, yet deeply resonating with every note as they fill the mind with endless memories. In truth, her music makes us nostalgic for things to come.

With each passing day, her own personal knowledge and self connections become larger and stronger, more honest and hopeful. Ultimately, putting it towards a positive energy rare within music, but one so deeply appreciated. Umi is, in a sense, creating the musical embodiment of love, fear, defeat, laughter, and truly, the human experience.

Our first question as always, how’s your day going and how have you been?

My day’s been going great! I’m on the plane right now headed to New York. I’ve been doing amazing, life is beautiful!

To take it to the start, when did you originally find yourself caught by the idea of pursuing music? Who or what around you pushed you onto the path you’re currently on?

I feel like I’ve always wanted to be a musician, I literally couldn’t imagine myself doing anything else. I’ve been writing songs since I was 4 and remember putting on little concerts for my mom and sisters. I don’t think one moment or event pushed me to do music, but growing up in a musical household and having friends who did music definitely encouraged me to pursue my passion.

Artistically, who were the artists that you found yourself drawing from, and how do you contrast those early influences to the ones you hold now?

I’ve been really inspired by artists like SZA, Frank Ocean, Jhene Aiko, and Benny Sings and found a lot of inspiration in their lyricism. I would say in the past I was more inspired by genres of music (R&B, gospel, alternative, pop) rather than a specific artist, which is why I feel I was able to understand and develop my own sound. But finding inspiration in artists over the past few years has helped me to improve the way I write from a lyrical standpoint.

Do you find the roots that you grew up from helped shape who you are as an artist?

I definitely think so! I grew up in a very musical household so creating music became second nature to me. My mom was a pianist, my dad played the drums, my aunt is a blues singer, and literally, everyone else in my family sings or plays an instrument. There was always music playing in my house and because I’m both Black and Japanese, I grew up listening to lots of different types of music (from gospel to R&B to Japanese pop to Korean music). I think that’s what has allowed me to come up with the melodies that I do now and to feel comfortable making different types of music. I also grew up in Seattle. It rains there ALL THE TIME. I think the gloomy weather and all the nature might also be where certain aspects of my sound subconsciously developed from.

Beyond artists, you also have an interesting passion for astrology and similar forms of personal spirituality. Where would you say this came from and how has it lent itself to your music and understanding of yourself?

I’m not an expert on astrology so I can’t claim to that passion yet, but I am very passionate about spirituality. My mom has always been very spiritual but she never pushed her ideas onto me; I think she always knew it was something for me to discover on my own. I remember right before I moved to LA, I stumbled across this random YouTube video on the Law of Attraction (I definitely think the universe wanted me to watch it). That video shifted the way I saw the world. Since then, I’ve just been constantly reading, writing, meditating, and listening in order to learn more about my own spirituality. Spirituality to me is all about enhancing your self-awareness and understanding the power of your mind! Everything is energy, and whatever frequency your vibrate at reflects the people and circumstances that are attracted to you. When I began to understand this, my life changed!

To those who may not understand or question reasons to practice these forms of spiritually, what would be your message and answer to their confusion?

I think a lot of people stop themselves from being happy and truly fulfilled by holding onto learned ways of thinking. I think society teaches us that life is supposed to be hard and sad and full of discontent and so people become identified with this mindset. We think that happiness is difficult so we attract difficult situations, bad people, and unfortunate circumstances into our life. It’s a cycle. Happiness and belief in abundance is innate, you can see that in the way babies look at the world, they don’t fear anything! Life is limitless. Spirituality — or enhanced/deeper self-awareness — allows you to reconnect with this innate understanding you may have lost through living in an unconscious society. When you realize that life is meant to be happy, and easy and fun you attract happy people, positive circumstances, and abundance back into your life. Through practices like meditation, self-reflection etc you realize what traumas in your life may have caused you to hold negative beliefs of the world. This then gives you the power to release your past, let go of your perceived sense of self, and reconnect with the real essence of you! It’s beautiful! I know it’s the reason my music finally started to grow. Literally, every single affirmation I say to myself comes true now. I’m so powerful!

As well, you’re fantastically vocal about the current political and social situations that matter most to you, even expressing them musically with songs like Dear Donald Trump. Do you hope to continue using your music and artistry as a vehicle for change and why, for you, is it essential to remain expressive as a youth through such turbulent times?

Yes, as my platform begins to grow, my voice will only grow louder. It’s so important for me to use this opportunity to shed light on various social issues and stand up for what I believe in. I want to become an advocate for change especially for issues regarding woman of color, police brutality, reproductive rights, and immigration. I’m still constantly learning myself, so I hope as I get older and have more resources, I can find even better ways to enact change both through music and outside of music.

You’ve said yourself that it’s been a really positive past year for you, in all facets of life, but if you could pinpoint one memory which sticks out above the rest, which would it be and what is its significance?

There have been so many fulfilling memories this year (so many happy tears!) but the one that sticks out to me the most is when my video “Remember Me” hit 1 million views. It was such a surreal moment for me. I’ve made so many videos in the past that I hoped would reach a million views and every time it didn’t I would get discouraged. When this happened, it all made sense. I realized that nothing in the past was supposed to gain the views that “Remember Me” did. It was confirmation to me that everything was happening exactly the way it was meant to be, when it was meant to be. More than anything, I was just really proud of myself and deeply grateful for all the people who helped me get to where I am.

As we stand at the beginning of a, hopefully, positive new year, what goals and plans do you hold? What projects or ideas do you hope to work on or execute?

1. Release more music! Release a few projects! 2. Release more music videos3. Collaborate with more artists 4. Go on tour! See the world! And headline my own tour! 5. Perform at some festivals 6. Self-direct my own music video 7. Meditate more, read more, share love, express more gratitude 8. LOVE MYSELF! 9. Start weight lifting, or boxing.

Recently, you began to explore collaboration more with songs like Lullaby. Is this an experience you hope to continue pursuing? And, if you could collaborate with one living or dead artist, who would it be?

I have lots of exciting collaborations in the works right now that I’m excited to release! And I can’t wait to continue to collaborate with more artists. My dream is to collaborate with SZA and Jhene Aiko one day! I’ll manifest it.

If you could recommend one movie, book or show to everyone reading this currently, which would it be?

I think everyone in the world should read “A New Earth” by Eckhart Tolle and listen to the podcast series Oprah did with him about the book! It changed the way I see the world! Also, listen to Oprah’s "Super Soul Sunday" podcast. It’s such a great way to challenge your mind and shift your perspective about life. Also, watch the movie “Mr. Nobody” it still has me thinking about the concept of time and life.

Do you have anyone or anything to shoutout or promote? The floor is yours!

Follow me on Instagram, Twitter, Facebook @whoisumi, check out my website whoisumi.com, and stream my music on all streaming platforms!! I have lots of new music on the way.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Saturday, 29th of october 2005

Nasu has a foul temper this morning. The weather is awful.

Rain wasn't supposed to fall today according to the weather forecast, but it did anyway.

All of my conference meetings have ended at last. I finally have time to enjoy the day's recreational events. The Autumn Leaves of Nasu Festival happens today. We could have used some better weather for it.

Fog obscures and blanches the autumn leaves' colors. White leaves overlap the red leaves, and only white remains.

We salvaged the Rice Cake Making Event by moving it to a new location. We're all supposed to participate in this event and make rice cakes according to the traditional methods.

Hideo participated too! I tried to keep a steady pace while pounding rice cakes out of steamed rice. It's pretty tough keeping up with professional rice cake makers though.

We finished the rice cakes.

"Let's eat this with our favorite toppings: ground black sesame seeds, kinako, bean jam, grated Japanese radish, and natto."

My attention was so immersed in making rice cakes that I hadn't noticed the appearance of several new stalls. I saw that stalls had been prepared for Ramen, Oden, and Kenchin-jiru.

Kenichiro and Okamura slept deeply while I enjoyed these festivities. They didn’t budge from the karaoke machines last night! I had parted from them and returned to my room earlier in the evening. It looks like I made the right choice.

I exercised a little bit of self-control and omitted a certain photograph from this blog entry.

Rice cake making resumed once again! Everyone joined the pounding.

Nasu's weather returned to a better mood around noon. The world returned to its former beauty when the rain cleared. The sky smiled only moments after it had stopped weeping. Nasu became a newborn infant.

I decided to walk around some of the nearby areas when my stomach got full. Mr. Muraoka and Okamura joined me.

The three-day conference concluded with a horseback archery event.

I owe a large amount of gratitude to many people as usual: the administration, the management department, and the campus staff. Thank you so much everyone. I appreciate everything greatly.

A game developer's true work lies in entertaining people. In that sense, we are accustomed to making people happy. Our position reverses every time we come to Nasu though. We are always the ones made happier.

They really treat us with heartfelt care and ensure our satisfaction.

Nasu's Autumn Leaves Festival captivated us with its beauty, yet the event staff's attention to service also dazzled us. They were superb ; an excellent support staff. They slipped in and out of events without calling attention to their presence. They became as slick and inconspicuous as the shadows of those who they supported. Suffice to say, all this is easier said than done.

No one has a universal manual with directions that explain how to ease a person's heart and mind. People are genuinely hard to please and entertain. Everyone is different, including the audiences who we face when developing our games. Tastes, hobbies, and preferences differ between each person. We all react with different emotions. Our work must meet the gamut of personalities.

I am always impressed by the environment and procedure of this conference. Today's event was especially marvelous though. They acted with excellent speed, decisiveness, and flexibility, but their heartwarming hospitality stuck out the most.

The unfortunate weather didn't even faze them. They moved forward with a back-up plan that still succeeded to surprise and entertain us. We were greatly pleased. Their hospitality was most evident through their magic shows, balloon art, and cosplay performances. That was real entertainment.

I enjoyed myself fully despite the rain. In fact, I believe that I owe even the rain a bit of thanks too. It caused the things that pleased me most: what it revealed about our hosts' abilities, and Nasu's transformation from rain to shine.

The event staff waved after us while our bus left for the train station. They waved until we couldn't see each other anymore. They truly reminded me of the value of true hospitality. They provided irreplaceable, priceless support.

A video game is a type of service too. We offer our gaming audience a digital variant of hospitality.

I swore an oath as I left Nasu. "I must make a good game!" I swore my oath so that I would remember these feelings.

A thought occurred to me on the bus. Nasu's event staff was more entertaining and hospitable than my development staff! Perhaps I could make a game with the event staff instead. I bet that we could make something good and entertaining.

I slept soundly as the bus arrived at the Nasu-Shibara station. We really were in the thick of the tourist season. People packed the station, and many cars filled the rotary.

I looked toward the station's souvenir shop when I exited the bus. I saw something sparkle inside. How surprising! Sparkle-Badges were displayed in the shop, even though they hadn't been there two days earlier!

The stock was smaller than the number on sale three weeks ago. Still, there's no doubting that these were the same items. The tourists coming into town to see the autumn leaves must have bought out the store's stock before. I couldn't miss this opportunity.

I chose a white guitar model out of the many Sparkles available.

"I'll take this please!"

A young woman working in the store said, "All right! Let me check and make sure that it works correctly.

She pulled one from the inventory. She thoroughly and kindly explained how to change the batteries, how to make it sparkle, and how to wear the badge. She even wore it on her jacket as a demonstration before she was through.

I was really glad that someone took such care to explain something thoroughly and carefully. Hardly anyone takes time these days to explain a product's operation like she did, not even in high-tech electronics stores. Those clerks won't give a decent answer even if they're asked directly.

A shopkeeper's spirit penetrates a customer's thoughts. Herein lies the charm of a small business. They take the time to explain even cheap merchandise thoroughly. I could intuit the pleasure that she received from selling goods, and in this way I could share her work's pleasure. This is another variant of hospitality.

I felt good about the whole experience.

"Is she the same saleswoman who I saw three weeks ago?" I asked myself. She certainly showed a similar passion for her work. I checked my diary notes to read what I had written three weeks ago.

I noticed that I had written this: "I stared at the badges and then my eyes connected with those of an old woman who worked in the shop. She explained that dead batteries could be replaced with new ones in this particular model."

An old woman? Wait a second!

Let me correct something: she is not an old lady, but rather a young woman. I had observed and remembered people through a private veil of negativity that day. I consequently recorded the saleswoman as an old lady. Yet she appeared as a young woman today because I received such warm hospitality.

I finally had my hands on Nasu's local specialty, the Sparkle-Badge! I triumphantly mounted the train platform. Matsuhanan had been watching me while I was in the souvenir shop. He called me to his side.

"You bought one of those badges too, Director?"

"Matsuhanan . . . you have one?"

"Yes, I bought mine in Roppongi Hills."

What!? So this means that they can be purchased anywhere!

We took the Nasuno248 train back to Tokyo.

I switched on my Sparkle-Badge inside the Shinkansen bullet train. The Sparkler bought in Nasu lit up our little traveling Nasu ; the Nasuno248.