#Vrijman

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Remco Campert ontmoet de hoogblonde dichteres

bron beeld: groene.nl Jagtlust van schrijfster Annejet van der Zijl (1962, Oterleek) geeft een prachtig inkijkje in de bezigheden van de artistieke scene uit de jaren 50, vorige eeuw. Alles draait om de plek: Villa Jagtlust in het Gooi. Het buitenhuis bood in de wilde jaren 50 onderdak aan tal van prominente schrijvende en beeldende kunstenaars: Cees Nooteboom, Jan Vrijman, Fritzi Harmsen van…

View On WordPress

#20-ste eeuws#artistieke scene#Blaricum#Campert#Harmsen ten Beek#Heintje Harmsen ten Beek#Het Gooi#jaren 50#Max Reneman#Müller#Nooteboom#Oterleek#prominenten#Schierbeek#schrijfster#Van der Elsken#Van der Keuken#Villa Jagtlust#Vrijman

0 notes

Text

Kraaminrichting Rijkskweekschool voor vroedvrouwen aan de Henegouwerlaan, 1914.

Op 26 juni 1914 werd de Rijkskweekschool voor Vroedvrouwen aan de Henegouwerlaan officieel geopend door de Minister van Binnenlandse Zaken Cort van der Linden. De in 1882 gestichte school was eerder in de Raampoortstraat gevestigd. Het statige nieuwe gebouw was ontworpen door Johannes Vrijman (1865-1954), rijksbouwkundige voor onderwijsgebouwen. Het gebouw heeft een U-vormige plattegrond rond een binnentuin. Een langgerekt bouwdeel van 70 meter lengte ligt op 28 meter afstand van de Henegouwerlaan; de twee zijvleugels zijn 37 meter lang.

Het gebouw bevatte lokalen voor het onderwijs, huisvesting voor de leerlingen en een moderne kraamkliniek. Het was een voor die tijd zeer moderne kliniek, met centrale verwarming, elektrische verlichting en modern sanitair. Op de begane grond lagen de leslokalen en directievertrekken, op de eerste verdieping verpleegkamers en op de tweede verdieping 50 kamertjes voor verpleegsters. Deze lagen aan weerszijden van een middengang. Op de zolder waren bergruimtes, linnenkamers en dienstbodenkamertjes, die hun daglicht kregen door middel van dakkapellen. In het uitspringende middendeel waren de eetzaal en een grote verpleegzaal gesitueerd. Er was dus geen monumentale hoofdentree, maar een viertal secundaire ingangen. In de hoeken voeren twee royale trappenhuizen naar de verbindingsgangen langs de buitenste gevel. Zo hadden alle ruimtes uitzicht op de tuin. Het gebouw was voorzien van betonnen vloeren. De houten kap was met leien bedekt. Het gebouw heeft sobere bakstenen gevels met een regelmatige raamindeling, voorzien van natuurstenen versieringen. Er zijn plaquettes aangebracht met de namen van de vier belangrijkste verloskundigen uit het verleden.

In 1970 werd het gebouw uitgebreid met een bouwdeel van staal en glas langs de Henegouwerlaan. De begane grond bleef onbebouwd zodat er zicht bleef op de binnenhof. In 1975 verhuisde de kliniek naar het Van Dam-ziekenhuis. In 1979 werd het kantongerecht in het gebouw gehuisvest.

Na de verhuizing van de rechtbank naar de Kop van Zuid in 1996 ontstond het idee het gebouw een bestemming als woongebouw te geven. Eerst werd het complex als Nieuw Leven gepresenteerd; toen deze ontwikkeling niet vlotte werd het project herontwikkeld als De Magistraat. De detonerende voorbouw werd verwijderd zodat de oorspronkelijke U-vormige opzet terugkeerde. Het gebouw is verder extern in oorspronkelijke staat gebracht; intern zijn 35 appartementen van 60 tot 200 vierkante meter gerealiseerd. De woningen hebben een bijzondere verdiepingshoogte van ca. vier meter op de onderste lagen en bijna zes meter onder de schuine kap. De binnentuin is in ere hersteld en voorzien van een parkeerkelder. Een nieuw hek, waarin een glazen geluidswand is verwerkt, moet het verkeerslawaai van de Henegouwerlaan weren.

Tegelijkertijd zijn aan de achterkant van het complex in de Zijdewindestraat 41 woningen gebouwd, ontworpen door Molenaar & Van Winden.

De foto komt uit de Collectie Topografie Rotterdam en bevindt zich in het Stadsarchief Rotterdam. De informatie komt van rotterdam.nl. http://www.rotterdam.nl/tekst:rijkskweekschool

0 notes

Text

Update 08 - “Anarchy” in Kemayoran

18th of August 1997

After personally being enraged by the lack of serious action by the students, the leader of Forum Kota hastily assembled an ad hoc group of “Vrijman” (Premans) to voice their concerns against the status quo around the area of Kemayoran. Adian Napitupulu stated “their strength in numbers” will flood the streets of Jakarta. This resulted in a group of 10 men (seen in the picture) in Napitulu’s personal vehicle causing minor disturbances with local authorities. Other students have cited the event as "bizarre."

0 notes

Photo

Action, reality and fiction in the art of the 60's in the Netherlands

+28

#Robert Jasper Grootveld#Cor Jaring#Peter Schat#Herbert Behrens#Mood Engineering Society#Igno Cuypers#Wim T. Schippers#Hans Bruggeman#Simon Vinkenoog#Jan Vrijman#Gerrit Lakmaaker#Cornelis Bastiaan Vaandrager#Ed van der Elsken#Benjamin Patterson#Egbert Munks#Willem de Ridder#Simon Posthuma#Anton Kothuys#Bart Huges#Johnny van Doorn#Peter Bergman#Marijke Koger#Yoshio Nakajima#Robert Hartzema#Internationaal Instituut voor herscholing van kunstenaars#Pieter Boersma#Jeffrey Shaw#Tjebbe van Tijen#Thom Japsers

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

*Ik kende Yvi niet zo goed. Zij was de moeder van onder andere Barbara, mijn broer Pieters vrouw. Altijd een zeer vriendelijke dame, ondanks alle MS-toestanden waar ze mee te kampen had in haar rolstoel.

*En nog een dierbare, die overleed: Jan Vrijman. Zijn films, waaraan ik meehielp als opnameleider, zijn voor mij nog steeds de meest memorabele. Een saaie wasmiddelcommercial vergeet je natuurlijk sneller als een film over sociale werkplaatsen of over 100 jaar Rijksmuseum.

*

*Fred Petri belde op vanuit zijn huis in Oud-Loosdrecht: een leuke filmklus kwam er aan voor ons tweeën. Fred als cameraman en ik als interviewer. In opdracht van zijn buurman twee dorpen verderop, Zadelhoff de vastgoedhandelaar. Die nodigde om de zoveel tijd op zijn immense landgoed bij Breukelen de Zuid-Amerikaanse polo-wereld uit om een paar potjes te komen spelen. Paarden, jockeys, zadels, de hele mikmak werd vanuit Argentinië op Schiphol binnengevlogen. En de heer Zadelhoff wilde daar wel eens een filmpje van.

Chique feesttenten werden al dagen van tevoren in de weilanden op het Zadelhoff-domein opgezet door tientallen decorbouwers. Dit was serieus. Dit was niet camping Bakkum.

Onwaarschijnlijk uitgebreide catering voor de rijke genodigden werd voorbereid. En niet op plastic bordjes.

Op de grote dag, dat de polowedstrijden zouden worden gespeeld, kabbelde het opgewonden publiek rond het middaguur binnen voor een eerste glas welkomstchampagne. De meeste dames droegen volgens de traditie stevig (doch luxe) schoeisel om in pauzes tussen de wedstrijden het door paardenhoeven geteisterde grasveld weer bij elkaar te stampen: prachtig filmmateriaal natuurlijk, van die hele dure mantelpakjes in het weiland aan het rondtrappelen. Fred en ik hadden ogen en oren tekort. Prachtdag. Leuke Spaanse babbels met de Argentijnse staljongens.

*

*Met Mick, Coco, Jur en Lili spaarden we maandenlang centen, stuivers, dubbeltjes, kwartjes en guldens uit elk jaar vanaf 1950 want die zouden binnenkort verdwijnen met de komst van de euro; ik wou eigenlijk starten vanaf mijn geboortejaar 1949, maar toen zijn er geen munten geslagen. Dat sparen lukte goed: we betaalden altijd in de winkels met briefjes van 5 en 10 gulden, dan kreeg je lekker veel muntgeld terug, maar de munten die ontbraken vroegen we aan de luisteraars van Radio Noord-Holland. Succesvol. Natuurlijk heb ik ze allemaal nog, een ordner vol met plastic inlegvellen voor de verscheidene munten.

*Niet lang hierna had ik profijt van mijn nieuwe filmcredit, die ik was gaan gebruiken: Japan Consultant voor film en televisie. Eddy Terstall van Jordaan Film vroeg om raad voor een in Japan te draaien film van zijn hand, 'Rent-a-Friend'. Nou graag, zeg het maar, wawilluwete en wanneer gaan we erheen?

Wordt vervolgd.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dutch Loanwords

350 years is a while, so Dutch seeping into the Indonesian language is inevitable. Let’s explore some Indonesian words that are derived from Dutch! (We’ll ignore the ones that are similar to English, because you’ll know that already.)

A preamble fun-fact: older Indonesian spelling is closer to Dutch, but modern Indonesian has been simplified. OE becomes U, TJ becomes C, J becomes Y, and DJ becomes J.

anjing laut from zeehond. Seal (animal), but both these words literally mean “sea dog.”

apotek/apotik from apotheek. Pharmacy.

arloji from horloge. Wristwatch, watch. A fancier version of the more commonly used “jam tangan” (hand clock).

asbak from asbak. Ashtray.

ban from band. Vehicle tire/tyre.

bak from bak. As a noun, not a particle. Meaning container. Most commonly used for “bak mandi” (bathtub)

baut from bout. Bolt. As in, the metal fastener.

beken from bekend. Famous, popular, or well-known. Considered an informal slang word.

besuk from bezoeken. Bezoeken originally means “visit,” but “besuk” usually refers to visiting sick people.

BH (or beha) from bustehouder. Bra. So yes, BH does indeed mean “boob holder.”

bioskop from bioscoop. Cinema, movie theatre.

bon from bon. Bill, receipt.

buncis from boontjes. Boontjes means beans, but buncis refers specifically to green beans.

dah/dadah from dag. Dag means “day,” but “dadah” is a goodbye, like “bye-bye!”

dasi from das. (Neck)tie.

duit from duit. Duit is a copper Dutch coin. In modern Indonesian it’s a slang term to refer to money in general.

ember from emmer. Bucket.

engsel from hengsel. Hinge, like the ones on doors.

gaji from gage. Wages, salary.

gang from gang. Alley.

gardu from garde. Guard, watch post.

gorden from gordijn. Curtain.

gratis from gratis. Free of charge.

halte (bus) from bushalte. Bus stop.

handuk from handdoek. Towel.

insinyur from ingenieur. Engineer.

indehoy from in het hooi. “in het hooi” literally means “in the hay.” Indehoy is used to refer to sexual intercourse, though it’s not so common nowadays.

jas from jas. In Dutch it’s a coat/jacket, in Indonesian it’s a (formal) suit.

kalkun from kalkoen. Turkey (the bird). For comparison, turkey in Malay is “ayam belanda” (Dutch chicken).

kamar from kamer. Room.

kantor from kantoor. Office.

karcis from kaartjes. Ticket(s). It’s plural in Dutch.

kastanye from kastanje. Chestnut.

katun from katoen. Cotton.

kol from kool. Cabbage.

korsleting/konslet from kortsluiting. Short circuit.

kuitansi from kwitantie. Receipt.

kulkas from koelkast. Refrigerator.

kuda nil from nijlpaard. Hippopotamus, but both these words literally mean “nile horse.”

laci from laatje. Drawer. The derived Dutch word is a diminutive of “lade.”

mantel from mantel. Coat, mantle.

maskapai from maatschappij. Means “company” in Dutch, but is a fancy formal word for “airline” in Indonesian.

mebel from meubel. Furniture.

minder from minder. Means “less” in Dutch, but in Indonesian it means not confident/unconfident, "feeling lesser/smaller” if you will.

mur from moer. The nut, the companion to the bolt.

om from oom. Uncle. Another Indonesian word for uncle is “paman,” though it comes across as more formal.

oma from oma. Grandmother. Another Indonesian word for grandmother is “nenek.”

opa from opa. Grandfather. Another Indonesian word for grandfather is “kakek.”

pabrik from fabriek. Factory.

parkir from parkeer. Parking.

pensiun from pensioen. Retire/retirement.

persik from perzik. Peach (fruit).

preman from vrijman. Vrijman literally means “free man.” Preman refers to gangsters.

rekening from rekening. (Bank) account.

rem from rem. Brake.

rentenir from renteneer. Loan shark.

rok from rok. Skirt.

rokok from roken. Roken means “to smoke,” rokok can refer to cigarettes and smoking.

sakelar/saklar from schakelaar. Switch. Like light switches.

segel from zegel. Seal, with the definition “a device or substance that is used to join two things together so as to prevent them from coming apart or to prevent anything from passing between them.”

sekop from schop. Shovel.

sekrup from schroef. Screw. The metal pin with the spirals.

selang from slang. Does not mean slang. It means hose, like a water hose.

senewen from zenuwachtig. Nervous/jumpy.

setrika from strijkijzer. Clothes iron.

skakmat from schaakmat. Checkmate.

spanduk from spandoek. Banner.

tang from tang. Pliers.

tante from tante. Aunt/auntie. Another Indonesian word for aunt is “bibi.”

tas from tas. Bag.

traktir from trakteer. Treat, like to treat someone food.

wastafel from wastafel. Sink (for washing).

wortel from wortel. Carrot.

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

Of course the official title is different . The documentary by Jan Vrijman from 1961 is called ” De werkelijkheid van Karel Appel”, but most people from the genaration of Karel Appel know his famous words ….”ik rotzooi maar wat aan”. But his painting is far from intuitive and improvisation. Many of his complex paintings were thought out and prepared on paper and i suspect that even the painting Appel is executing in the documentary is prepared and worked out on paper before he paints the canvas.

Appel is a great artist and certainly one of the most important ones in the Netherlands from the last century. His painting is the summit in abstract expressionism and he deservedly earned his place among the worlds greatest artist.

http://www.ftn-books.com has a large collection of Karel Appel books available

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

Karel Appel and Jan Vrijman ( Ik rotzooi maar wat aan, 1961) Of course the official title is different . The documentary by Jan Vrijman from 1961 is called " De werkelijkheid van Karel Appel", but most people from the genaration of Karel Appel know his famous words ...."ik rotzooi maar wat aan".

#abstract expressionism#alechinsky#appel#cobra#gemeentemuseum#karel appel#painting#rotzooi#stedelijk#vrijman

0 notes

Text

REFLECTION.03 | urban FLESH deterritorializing URBANITY | Rohan Cloete

How does liminal space in an urban development accommodate the flesh of the city and bodies to allow for an embodied imagination?

“Inevitably, life between buildings isricher, more stimulating, and morerewarding than any combination ofarchitectural ideas”(Gehl, 2011:43)

The interpretation of liminality has various contexts, ranging from the social and cultural to the spatial (Zimmerman, 2008:5). The root word limen “is derived from the Latin word for ‘threshold,’ which literally means ‘being on a threshold” (Alexander, 1991:31). In all contexts, liminal refers to an intermediate state or condition; an in-between condition in which the liminal entity has characteristics of what it is between, but at the same time is separate and distinct from them. American architect, Fred Koetter, defines the liminal as “the realm of conscious and unconscious speculation and questioning – the ‘zone’ where things concrete and ideas are intermingled, taken apart and reassembled – where memory, values, and intentions collide” (Koetter, 1980:69). Very often Modernist, as well as contemporary architecture tend to be accused of emotional coldness and exclusivity.

Why is it that architecture and architects, unlike film andfilmmakers, are so little interested in people during thedesign process? Why are they so theoretical, so distantfrom life in general?(Vrijman, 1994:1)

It is for this reason that liminal, or in-between, spaces are so important. These spaces allow for both physical embodiment and an embodied imagination. Finnish architect and theorist, Juhani Pallasmaa, argues that there are two imaginations. “In my view, there are two qualitative levels of imagination; one projects formal and geometric images while another one simulates the actual sensory, emotive and mental encounter with the projected entity” (Pallasmaa, 2015:7). The first type of imagination projects the material object in isolation, while the second projects it as a lived and experienced reality in the life world (ibid).

“In the first case, the imaginatively projected object remains as an external image outside of the experiencing and sensing self. In the latter case, it becomes part of our existential experience, as in the encounter with material reality” (ibid). Therefore, the formal imagination is largely engaged with topological or geometric facts, while the emphatic imagination conjures embodied and emotive experiences, qualities, and moods. This relates to the notion of the French philosopher, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, which denotes the lived reality as “the flesh of the world”. To Pallasmaa, the empathic imagination conjures multi-sensory, integrated and lived experiences of this very flesh (Pallasmaa, 2015:8). It is for this reason that an urban corridor and architectural object will be investigated and anlayzed in terms of its success to create embodied imagination through liminal space. The chosen corridor is an exclusive pedestrian walkway, which runs diagonally along Bishops Avenue in Kimberley, South Africa. The corridor is part of an urban development in the city which forms a city campus for the Sol Plaatje University. The corridor was chosen due to its dedication to both the human flesh as well as the city flesh. Serveral principles and a spatial development framework guides the design of the urban environment in which the corridor finds itself. These will all be analyzed and expanded upon. The chosen architectural object also finds itself along this corridor. The architecture will also be analyzed and its qualities will be measured in terms of the research question and the applicability to the urban approach.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Cinema of the Unspoken: Documentary Shorts of Yasmine Kabir

by Tazeen Ahmed

Yasmine Kabir is a Bangladeshi independent filmmaker who has been exploring the documentary field since 1990s. Before this blog delves into her films, it is important to explain her place in contemporary Bangladeshi cinema. The documentary form is quite widely practiced in Bangladesh. Being a developing nation, Bangladesh is the hub of prolific development work with innumerable Non Governmental Organizations (NGO), schemes and policies in place. Along with policies and interventions comes development communication where documentary filmmaking plays an important role. Thus, to find a documentary in Bangladesh regarding marginal societies may not be a hard feat. Kabir’s work also encompasses unspoken stories of various marginal communities. At first glance, her films might come across as just another tale of development narrative. Yes, it is part of the narrative. Yet, her work somehow exceeds the ‘status quo’ narrative of the development documentary and rather throws the audience into her subjects’ pain in a much more direct manner. There is a do-it-yourself (DIY) flavour to her films which I think really sets her apart in the documentary filmmaker’s realm in Bangladesh.

Like her subjects, Kabir’s films seem to belong to the unspoken territory in the written world of film criticism. With a filmmaking career going back to the 1990s and with many of her films having been screened at various international festivals or film societies including Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival and International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (where it received the Jan Vrijman Fund), it is rather surprising that almost no written work exists about her films. However, she is highly revered among the independent filmmaking community of the country. It is a growing time for independent film in Bangladesh. Due to participation of several films in many prestigious international festivals and film markets in recent years, Bangladeshi films are garnering a spotlight as part of South Asian cinema, which used to mainly refer to films from India. I believe it is about time to talk about the films of Yasmine Kabir who has inspired filmmakers in Bangladesh for quite a while now.

Yasmine Kabir’s films span from the topic of migrant workers to war victims. Her films are extremely powerful, yet minimalistic in their language; no complicated filming techniques are applied. Rather, she delves directly into her subject and makes the audience experience them up close throughout a 16-30 minutes runtime. She is solely interested in capturing the faces and voices of her subjects, like a portrait painting. But her work is diverse. Her films can also be completely devoid of voices and dialogues.

My Migrant Soul

Let us begin with Kabir’s most renowned film, titled My Migrant Soul (2000). It is the story of a migrant worker Shahjahan Babu, who went to work in Malaysia in the 1990s, only to fall into the usual traps of a manpower scam, ending up perishing away in a detention camp. The images in the film are made by juxtaposing interviews of his family members – long after he passed away – and images of streets and locations in Malaysia with the voice of Babu who used to send cassette tape recordings back to his mother as correspondence. My Migrant Soul opens with workers being inspected and selected at a ‘manpower export’ organization. We see close-up shots of the workers’ faces and their bodies with their hands while working. The shots of the faces have no sound. The opening soundscape thus ends up provoking a kind of anxiety by placing loud thuds, hammering, machine sounds in opposition to complete silence.

After the black-and-white opening of the film, the rest of the film intermingles home-video styled images of Malaysia with the smoother images ‘at home’ which create an interesting contrast in texture; images are blurrier abroad, clearer at home. Yet, it is almost as if Babu had recorded those images of Malaysia along with his voice-recordings and ended up provoking a haunting feeling in the viewer. The deceased protagonist of the film exists in memories; in his voice recordings, a few photographs and in the coffin that his sister still carefully keeps in the house while Malaysia only exists in the imagination of her family members. The film is able to create a powerful diegesis in the viewer’s mind, made up of images that are not shown. A secret reel of Babu’s life in Malaysia plays inside the viewer’s mind while watching the film. None of it is present on screen; it is not possible to present it on screen. But that does not stop Kabir from telling the story. I always remember a scene from the film where Babu is working at night, in a construction building with welding sparks flying about. Yet, when watching the film for this essay after many years, to my surprise, I found no such image exists.

The Last Rites

Her next film The Last Rites (2008) is the only one out of the five shorts discussed here that contains an opening with a long shot. However, that is probably due to the film’s topic of workers in a Chittagong yard engaged in the gruelling job of ship-breaking. In 2019, the ship-breaking industry of Bangladesh topped the world market by dismantling 42.2% of the world’s vessels (Hussain, 2019). But one of the reasons behind this success is cheap labour and no standard regulations. Most of the scrapping is done manually, without the use of heavy machinery.

The film throws us into a morning at a yard. By repeatedly showing images of men pulling ropes tied to heavy pieces, close ups of their bodily strain, the film shifts from light to dark, from morning to night. But the work never stops and the weights on the workers’ shoulders are never lifted. After the opening, shots become tighter and the subjects seem overwhelmed in their surrounding of water and metal. The handycam tries to zoom in as close as possible. As soon as Kabir gets a chance, with workers reaching the shore, we are back to close-ups and extreme close-ups again; of hands pulling ropes, nets, garbage. The film ends with a combination of silence and haunting music on stills of ship parts and scraps which, by then, scream of death, blood and sweat.

A Certain Liberation

A Certain Liberation (2013) follows a Liberation War victim Gurudasi Mondol, who roams the streets of her small town in Southern Bangladesh and is known as a mad woman who takes money from passersby at will. Some people give her money out of pity, but most tolerate her to avoid some kind of attention-drawing incident. Mondol has garnered an authority in usually male-dominated spaces by physically touching men passing by or beating them with a stick she carries around or simply by uttering swear words that a woman is not supposed to – she defies all definition of being ‘lady-like’. But the people of her community have gotten used to her eccentricities as well. The children of her community love her and find her to be a queen while she calls herself ‘the mother of Bengal’ as many of the children grew up with her around.

The circumstance of her life is rooted in the atrocities of the Liberation War of Bangladesh. Her family was killed in front of her eyes by the ‘Rajakar Bahini’, the anti-Bangladeshi paramilitary created by the Pakistani army. Although it is never explicitly mentioned in the film, but we can assume that Gurudasi Mondol was most likely raped as she was captured and imprisoned in the ‘Rajakar’ camp for days. The war took everything from her, and she found her own way of liberation and survival. By being obscene, she is liberated and free to do whatever she wants. But it is difficult to say which is more obscene, her madness or her circumstances.

Tazreen and Rope

Yasmine Kabir’s next two films are even looser in structure than the ones mentioned so far. Tazreen (2014) is probably the most DIY in style out of the five films discussed in this article. The film simply interviews the worker victims of a garments building fire, year after its occurrence. From beginning to end, the film records whatever the victims have to say in close-ups. Rope (2016), her last film is made up of close-up images of a child labourer working at a rope factory, manually turning jute thread into ropes.

All of Yasmine Kabir’s films have extremely short exposition, which almost never uses long shots to establish location. Instead, the camera is up-close and personal from the very beginning of the film, creating an effect of throwing the audience into focusing on the subjects’ faces. Just like in a portrait, we can take our time to observe the shapes and colours of the face closely and because of the moving images, also the subtlest changes in expression or shifts in the eyes. We are forced to ‘look at’ her subjects that are usually people who are overlooked in society. A Certain Liberation has a brilliantly minimalistic exposition by which the context of the film is set. Kabir uses footage of the victory of the Liberation War followed by chronological footages of all the leaders of Bangladesh and ends up expressing the country’s history in a handful of shots. Her style of using close-ups usually includes other parts of the body such as hands and feet. As many of her films want to signify physical labour of the working class, it becomes a very effective device to express strenuous labour. Both Rope and The Last Rite portray visual imagery of physical strain and force by using these devices and show how much the human body endures in the age of modern slavery.

••••••••••••

It is important to understand some of the context of Yasmine Kabir’s films. The 1990s saw an explosion of NGO documentary filmmaking and a lot of funding was available in that sector. However, unlike today, the topic of migrant workers was not in much fashion back then. My Migrant Soul is an early account of the perils of migrant workers of Bangladesh and is a film that was way ahead of its time in its thinking. On the other hand, Tazreen might seem like an almost amateurish news-report type account of victims. However, it is important to mention that the film was shot after a year of the original Tazreen garment fires of 2012. It was made in 2013, when another tragedy hit with the collapse of the Rana Plaza garment in Bangladesh that garnered international attention. By bringing the victims of the Tazreen fire on screen, at a time when all lenses were focused on Rana Plaza, Kabir is able to make the bold statement of how quickly we forget these incidents and how they just keep on happening, no matter how much we cover them in the media. As for A Certain Liberation, a great number of women were victims of genocidal rape and went through the horrors of a bloody war. However, the representation of these women on screen usually remains as that of victims, broken, or as helpers of the liberation army (Mukti Bahini). Kabir takes the war victim, embraces her madness and gives her power and authority in her film. We see the strength of the rape victims not in their sacrifice (as sacrificing is deemed as woman’s virtue), but in their resilience and endurance.

Within the development narrative, Kabir’s films, by delving into the micro-level, looking at a single person (My Migrant Soul, A Certain Liberation), forces the audience to remember a singular migrant worker, a singular liberation war victim which in our story-loving minds become much more effective than a broader macro-level narrative. On the other hand, Rope and The Last Rite give us an ensemble of close encounters of the hands, feet, shoulders of working boys and men in blips and glimpses. But again, by repeating and continuously focusing on just the characters, not the backdrop, we are forced to remember, maybe not a single person, but what every ship breaker and rope worker goes through every day. Tazreen, as I have mentioned before is an anomaly. The power of Tazreen portrays Kabir’s sense of urgency, sense of timing for making her films. This completely plain looking video recording of a crowd expressing their pain was a necessary film. It is this urgency, a sense of ‘this must be recorded’ that gives power to Yasmine Kabir’s films. Her intent shines through in this urgency; the intent to directly show the audience whatever is available even if it means that aesthetics of film needs to be sacrificed.

The films of Kabir are usually self-produced, with help from friends. The filmmaker leads a rather secluded lifestyle, often refusing public appearances. Her films have been exhibited in prestigious international film festivals. But that has not stopped her from taking ‘a step down’ and screening her films at as many small film societies as possible. Unlike many filmmakers, she is not very particular about where or how her film is being shown, as long as there is an audience. Her last film Rope was screened in a small rural community and after Gurudasi Mondol’s passing, A Certain Liberation was screened at her community in Kopilmoni. These screenings did not garner much media coverage either.

Yasmine Kabir’s films are not interested in the beauty of an image, per se. They do not contain the perfect shot. She is interested in showing but not showing-off. She is interested in maybe in the absence of aesthetics. That does not mean that her films are devoid of beauty. The beauty lies in compassion and empathy for her characters. It is very difficult to un-watch her films, to forget her images. Most of all, it is very difficult to forget the truth that is portrayed in Yasmine Kabir’s films.

YASMINE KABIR // FILMS

1. A Certain Liberation

Gurudasi Mondol gave herself up to madness in 1971, during the Liberation War of Bangladesh, as she watched her entire family being killed by the Razakars, collaborators of the Pakistan occupying forces.

Thirty years later, Gurudasi continues to roam the streets of Kopilmoni, a small-town in rural Bangladesh, in quest of all she has lost; snatching at will from strangers and breaking into spaces normally reserved for men. In her madness, she has found a strategy for survival.

In Kopilmoni, Gurudasi has attained near legendary status. Through her indomitable presence, she kept alive the spirit of Liberation.

2. My Migrant Soul

vimeo

“If I live, I'll write the history of my travels in Malaysia…. I'll write a poem about it." — Migrant worker, Shahjahan Babu

My Migrant Soul, is about Shahjahan Babu, a migrant worker, who left Bangladesh in search of work. Having sold his only piece of property and virtually mortgaging his life, the young man arrives in Malaysia, only to experience disillusionment, misery and frustration.The film highlights the plight of the migrant worker in these times.

Prior to his death, Babu sent home audiotapes to his family, in which he recounted his bitter experiences in Malaysia. These tapes are used as a running narrative throughout the film. Songs, sung by Babu, are woven into the film, lending a poignant structure to the tragedy of Babu’s life. The camera is the medium through which Babu tells us his story posthumously.

"In a marketplace, like fish and vegetables, humans are being bought and sold", said Shahjahan Babu.

My Migrant Soul is about dreams that crumble into despair.

3. Rope

Continuing a tradition that goes back centuries, children are employed as rope-makers in old town, Dhaka, making ropes by hand from jute fibres. They twist, tie, knot and weave from early morning till nightfall.

4. The Last Rites

'The Last Rites’, a silent film, depicts the shipbreaking yards of Chittagong.

Every year, hundreds of ships are sent from all over the world to yards in Bangladesh. And every year, thousands of people, many of them migrant farmers, come to these yards in search of jobs. Risking their lives to save themselves from hunger, they breathe in asbestos dust and toxic waste.

The elemental struggle between man and metal figures throughout the film, as men carry the weight of steel ropes over their shoulders, pull huge parts of the vessels inland, and bear great metal plates.

'The Last Rites’ is a portrayal of the agony of hard labor.

5. Tazreen

'Tazreen' documents the aftermath of one of the deadliest industrial fires to have occurred in the history of the garments industry in Bangladesh.

At Tazreen Fashions, Dhaka, Bangladesh on November 24th, 2012, the fire, started on the ground floor, quickly spreading to the floors above, trapping countless workers. Many were burnt, others leapt to their deaths below, and scores were left severely wounded. The fire blazed for over 17 hours. It was estimated to have killed 117 workers.

The film captures the grief, trauma and helplessness suffered by the survivors as well as of those who lost their loved ones.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Het gebouw van de Rijkskweekschool voor vroedvrouwen aan de Henegouwerlaan, 1914.

Op 26 juni 1914 werd de Rijkskweekschool voor Vroedvrouwen aan de Henegouwerlaan officieel geopend door de Minister van Binnenlandse Zaken Cort van der Linden. De in 1882 gestichte school was eerder in de Raampoortstraat gevestigd. Het statige nieuwe gebouw was ontworpen door Johannes Vrijman (1865-1954), rijksbouwkundige voor onderwijsgebouwen. Het gebouw heeft een U-vormige plattegrond rond een binnentuin.

Het gebouw bevatte lokalen voor het onderwijs, huisvesting voor de leerlingen en een moderne kraamkliniek. Het was een voor die tijd zeer moderne kliniek, met centrale verwarming, elektrische verlichting en modern sanitair. Op de begane grond lagen de leslokalen en directievertrekken, op de eerste verdieping verpleegkamers en op de tweede verdieping 50 kamertjes voor verpleegsters. Deze lagen aan weerszijden van een middengang. Op de zolder waren bergruimtes, linnenkamers en dienstbodenkamertjes, die hun daglicht kregen door middel van dakkapellen. In het uitspringende middendeel waren de eetzaal en een grote verpleegzaal gesitueerd. Er was dus geen monumentale hoofdentree, maar een viertal secundaire ingangen. In de hoeken voeren twee royale trappenhuizen naar de verbindingsgangen langs de buitenste gevel. Zo hadden alle ruimtes uitzicht op de tuin. Het gebouw was voorzien van betonnen vloeren.

In 1970 werd het gebouw uitgebreid met een bouwdeel van staal en glas langs de Henegouwerlaan. De begane grond bleef onbebouwd zodat er zicht bleef op de binnenhof. In 1975 verhuisde de kliniek naar het Van Dam-ziekenhuis. In 1979 werd het kantongerecht in het gebouw gehuisvest.

Na de verhuizing van de rechtbank naar de Kop van Zuid in 1996 ontstond het idee het gebouw een bestemming als woongebouw te geven.

De fotograaf is Cornelis Vreedenburgh en de foto komt uit het Stadsarchief Rotterdam. De informatie komt van rotterdam.nl

2024 🆕️

1 note

·

View note

Text

Kraaminrichting Rijkskweekschool voor vroedvrouwen aan de Henegouwerlaan, 1914.

Op 26 juni 1914 werd de Rijkskweekschool voor Vroedvrouwen aan de Henegouwerlaan officieel geopend door de Minister van Binnenlandse Zaken Cort van der Linden. De in 1882 gestichte school was eerder in de Raampoortstraat gevestigd. Het statige nieuwe gebouw was ontworpen door Johannes Vrijman (1865-1954), rijksbouwkundige voor onderwijsgebouwen. Het gebouw heeft een U-vormige plattegrond rond een binnentuin. Een langgerekt bouwdeel van 70 meter lengte ligt op 28 meter afstand van de Henegouwerlaan; de twee zijvleugels zijn 37 meter lang.

Het gebouw bevatte lokalen voor het onderwijs, huisvesting voor de leerlingen en een moderne kraamkliniek. Het was een voor die tijd zeer moderne kliniek, met centrale verwarming, elektrische verlichting en modern sanitair. Op de begane grond lagen de leslokalen en directievertrekken, op de eerste verdieping verpleegkamers en op de tweede verdieping 50 kamertjes voor verpleegsters. Deze lagen aan weerszijden van een middengang. Op de zolder waren bergruimtes, linnenkamers en dienstbodenkamertjes, die hun daglicht kregen door middel van dakkapellen. In het uitspringende middendeel waren de eetzaal en een grote verpleegzaal gesitueerd. Er was dus geen monumentale hoofdentree, maar een viertal secundaire ingangen. In de hoeken voeren twee royale trappenhuizen naar de verbindingsgangen langs de buitenste gevel. Zo hadden alle ruimtes uitzicht op de tuin. Het gebouw was voorzien van betonnen vloeren. De houten kap was met leien bedekt. Het gebouw heeft sobere bakstenen gevels met een regelmatige raamindeling, voorzien van natuurstenen versieringen. Er zijn plaquettes aangebracht met de namen van de vier belangrijkste verloskundigen uit het verleden.

In 1970 werd het gebouw uitgebreid met een bouwdeel van staal en glas langs de Henegouwerlaan. De begane grond bleef onbebouwd zodat er zicht bleef op de binnenhof. In 1975 verhuisde de kliniek naar het Van Dam-ziekenhuis. In 1979 werd het kantongerecht in het gebouw gehuisvest.

Na de verhuizing van de rechtbank naar de Kop van Zuid in 1996 ontstond het idee het gebouw een bestemming als woongebouw te geven. Eerst werd het complex als Nieuw Leven gepresenteerd; toen deze ontwikkeling niet vlotte werd het project herontwikkeld als De Magistraat. De detonerende voorbouw werd verwijderd zodat de oorspronkelijke U-vormige opzet terugkeerde. Het gebouw is verder extern in oorspronkelijke staat gebracht; intern zijn 35 appartementen van 60 tot 200 vierkante meter gerealiseerd. De woningen hebben een bijzondere verdiepingshoogte van ca. vier meter op de onderste lagen en bijna zes meter onder de schuine kap. De binnentuin is in ere hersteld en voorzien van een parkeerkelder. Een nieuw hek, waarin een glazen geluidswand is verwerkt, moet het verkeerslawaai van de Henegouwerlaan weren.

Tegelijkertijd zijn aan de achterkant van het complex in de Zijdewindestraat 41 woningen gebouwd, ontworpen door Molenaar & Van Winden.

De foto komt uit de Collectie Topografie Rotterdam en bevindt zich in het Stadsarchief Rotterdam. De informatie komt van rotterdam.nl. http://www.rotterdam.nl/tekst:rijkskweekschool

0 notes

Text

Hoeveel weegt een filmteam? Ik zit hier tijdens een kleine, maar fijne filmproductie naast regisseur Fons Grasveld (met baard) op de weegschaal in een sociale werkplaats in Gennep.

Jan Vrijman was de producent en het was me een genot die inspirerende man bij hem thuis in de Vondelstraat te ontmoeten. Juist die middag was de wasmachine overleden en Jans zeer verdrietige vrouw Nicole had het arme ding omwikkeld met een enorme zwarte zijden strik. Wij van het kleine filmteam aan de grote keukentafel rouwden mee onder het genot van oude kaas en een glaasje rode port.

Terug naar de film: titel "O, moet dat zo". Dat was de spontane uitroep van een van de geestelijk gehandicapte werkers, toen hij het trucje doorhad hoe hij iets in een bepaalde volgorde moest leggen. Enerverend om te filmen met geestelijk gehandicapten, ze doen alles met een goudeerlijke passie. Twee smoorverliefde broers van 42 jaar met het syndroom van Down verklaarden mij dagelijks in de week dat we er draaiden hun onvoorwaardelijke liefde. Mijn moeders broer was een mongooltje zoals dat indertijd heette, oom Dréke. Een grote schat, die voor al zijn nichtjes en neefjes jarenlang wollen onderhemden en onder- en zwembroeken (onmogelijk om in te zwemmen, ze lubberden uit en werden loodzwaar) breide. Hij deed wel eens raar, maar wie niet?

Zo'n sociale werkplaats is een oplossing voor in ledigheid thuiszittende geestelijk gehandicapten. Zeer eenvoudig werk, dat af en toe aan de peuterspeelzaal doet denken: dit kleurtje bij dat kleurtje, dat moertje bij dit boutje, dit balletje in dat gaatje: "O, moet dat zo!" Met die prachtige blije trotse ogen. Dat is film, meneer!

#catrienarïens

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

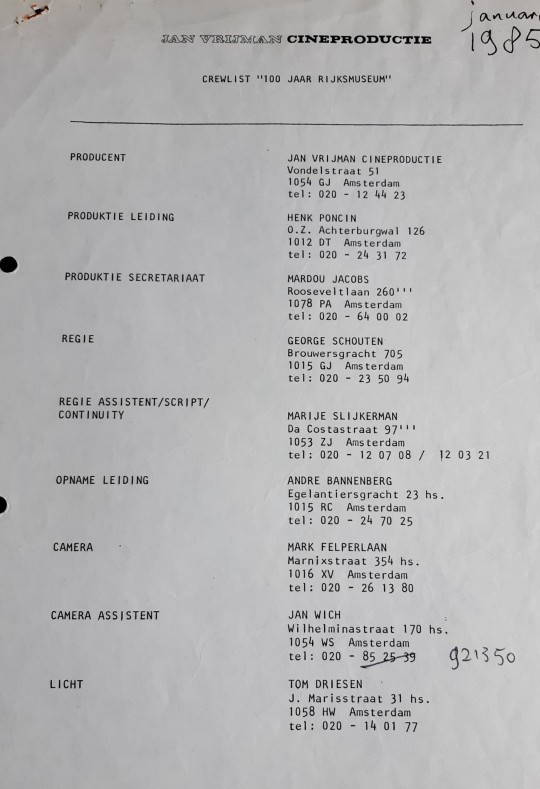

1985. Het Rijksmuseum bestaat 100 jaar. Jan Vrijman kreeg de opdracht daar een filmische ode aan te brengen.

Op de crewfoto: producent Jan Vrijman met snor en pet achter de camera, achter hem regisseur George Schouten. Derde van links staat ondergetekende, mèt peuk tussen de lippen, voor het duurste schilderij van de wereld...

Roken in het Rijksmuseum was een heel gedoe, dat kon alleen beneden in het restaurant bij de ingang. George Schouten, de regisseur, was een heavy smoker. Nu hadden we uitgerekend dat een sigaretje roken ongeveer 30 minuten in beslag nam: 10 minuten trappen af gangen door zalen in en uit in het immense museum naar het restaurant, 10 minuten roken en weer 10 minuten terug, hijg hijg, naar de set in die verre vleugel. Dus we konden alleen rustig een paffertje opsteken als er een flinke lichtombouw moest plaatsvinden of tijdens de luchbreak. Maar ja. Hoort erbij.

Gelukkig, ook voor de overige rokers, draaiden we af en toe een buitenopname in de tuin van het museum, zodat men even nicotine kon tanken.

En het volgende werk kondigde zich gelukkig al snel aan. Al die kindermondjes te voeden...

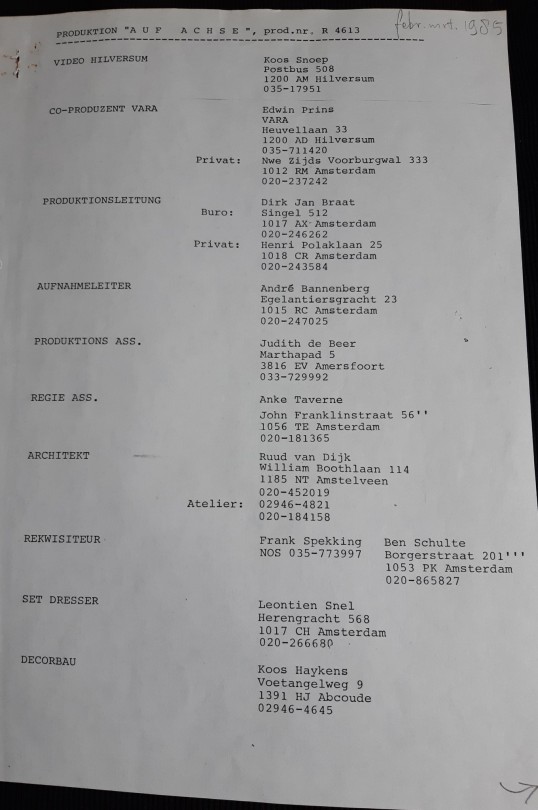

*In het voorjaar streek een grote Duitse filmploeg neer om opnames te maken in hun buurland voor een in Duitsland zeer populaire Krimi-serie: 'Auf Achse' = vrij vertaald: 'Met de vlam in de pijp'. Over vrachtwagen-criminaliteit.

Und so werd ik opeens Aufnahmeleiter: "Achtung bitte! Aufnahme!"

Het aardige tijdens deze productie was dat ik de verantwoordelijkheid kreeg over een nogal chique (nep)politiewagen, een Jaguar XSJ.

Dat ding werd door de Duitse decorploeg op aanwijzing helemaal aangekleed met (Hollandse) politie-emblemen, stickers en zwaailichten, dat zag er gelikt uit. Opvallend en tegelijk boeiend was het feit, dat ik, achter het stuur in die Jag, overal brave verkeersdeelnemers meemaakte, die me onnodig voorrang gaven en me tè vriendelijk toewuifden, vooral 's ochtends vroeg.

Ik parkeerde hem 's avonds voor de veiligheid in de garage van het Marriott-hotel bij het Leidsebosje. Op een avond stapte ik daarbinnen uit de Jaguar en daar stond een beeldschone Engelse jongedame voor mijn neus, die het gorgeous zou vinden om met mij van gedachten te wisselen over het politievak, op haar kamer hier in het Marriott, met een drankje erbij: Sheila werkte bij de Londense politie en was nu in Amsterdam voor het politiecongres, waar ik wellicht ook een dezer dagen naar toe ging?

Wordt niet vervolgd.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Opnieuw een kleine maar fijne sociaalbetrokken filmproductie met producent Jan Vrijman en regisseur Fons Grasveld (op de foto met baard). Het onderwerp was wegenbouw in Nederland.

(Op de crewlijst hadden de telefoonnummers 6 cijfers, zie ik. Tien jaar geleden nog 5.)

Mooie buitenlokaties, prachtig zomerweer en een kleine crew: dat betekende zeer productief draaien.

Er werd geprobeerd Amsterdam autovrij te maken. Pal onder ons raam in de Kinkerstraat tijdens een demonstratie lagen de opnames voor het oprapen.

Op de Museumlaan, toen nog helemaal geplaveid met klinkers en bekend als een racebaan, was het ook een drukte van belang met protesterende fietsers en figuranten zoals Sally en Rick uit Amerika, links op de voorgrond. Aan het eind van de opnames die middag besprak ik met Oom Agent de voordelen van het motorrijden, terwijl langzaam de demonstranten afdropen in het spitsuur.

1 note

·

View note