#Virginia iFile

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Weekly output: Virginia tax filing, Android 16, Disney and Universal v. Midjourney

View On WordPress

#AI image generation#android#Android 16#copyright#Disney+#Electronics Home Mexico#generative AI#Homer Simpson#Intuit#Mexico City#Midjourney#Pixel#Virginia form 760#Virginia iFile#Virginia taxes

0 notes

Text

Gwen Ifill

Gwendolyn L. (Gwen) Ifill (/ˈaɪfəl/; September 29, 1955 – November 14, 2016) was an American journalist, television newscaster, and author. She was the moderator and managing editor of Washington Week and co-anchor and co-managing editor, with Judy Woodruff, of PBS NewsHour, both of which air on PBS. Ifill was a political analyst and moderated the 2004 and 2008 Vice Presidential debates. She was the author of the book The Breakthrough: Politics and Race in the Age of Obama.

Early life and education

Ifill was born in New York City, the fifth child of African Methodist Episcopal (AME) minister (Oliver) Urcille Ifill, Sr., a Panamanian of Barbadian descent who emigrated from Panama, and Eleanor Ifill, who was from Barbados. Her father's ministry required the family to live in several cities throughout New England and the Eastern Seaboard during her youth. In her childhood, Ifill lived in Pennsylvania and Massachusetts church parsonages and in federally subsidized housing in Buffalo and New York City. She graduated in 1977 with a Bachelor of Arts in Communications from Simmons College in Boston, Massachusetts.

Career

While at Simmons College, Ifill interned for the Boston Herald-American and was hired after graduation by editors deeply embarrassed by an incident during her internship in which a coworker wrote her a note that read, "Nigger go home." Later she worked for the Baltimore Evening Sun (1981–84), The Washington Post (1984–91), The New York Times (1991–94), and NBC.

In October 1999, she became the moderator of the PBS program Washington Week in Review. She is also senior correspondent for the PBS NewsHour. Ifill has appeared on various news shows, including Meet the Press.

She serves on the board of the Harvard Institute of Politics, the Committee to Protect Journalists, the Museum of Television and Radio, and the University of Maryland's Philip Merrill College of Journalism.

On February 7, 2011, Ifill was made an Honorary Member of Delta Sigma Theta during the sorority's 22nd Annual Delta Days in the Nation’s Capital.

With Kaitlyn Adkins, Ifill co-hosted Jamestown LIVE!, a 2007 History Channel special commemorating the 400th anniversary of Jamestown, Virginia.

The PBS ombudsman, Michael Getler, has twice written about the letters he's received complaining of bias in Ifill's news coverage. He dismissed complaints that Ifill appeared insufficiently enthusiastic about Sarah Palin's speech at the 2008 Republican National Convention, and concluded that Ifill had played a "solid, in my view, and central role in PBS coverage of both conventions."

On August 6, 2013, the NewsHour named Gwen Ifill and Judy Woodruff as co-anchors and co-managing editors. They shared anchor duties Monday through Thursday with Woodruff as sole anchor on Friday.

Published works

Ifill's first book, The Breakthrough: Politics and Race in the Age of Obama, was released on January 20, 2009, Inauguration Day. The book deals with several African American politicians, including Barack Obama and such other up-and-comers as Massachusetts governor Deval Patrick and Newark, New Jersey, mayor Cory Booker. The publisher, Random House, describes the book as showing "why this is a pivotal moment in American history" through interviews with black power brokers and through Ifill's observations and analysis of issues.

2004 & 2008 vice-presidential debates

On October 5, 2004, Ifill moderated the vice-presidential debate between Republican Vice President Dick Cheney and Democratic candidate John Edwards. Howard Kurtz described the consensus that Ifill "acquitted herself well" as moderator.

Ifill also moderated the October 2, 2008, vice-presidential debate between Democratic Senator Joe Biden and Republican Governor Sarah Palin at Washington University in St. Louis. The debate's format offered Ifill freedom to cover domestic or international issues.

Before the 2008 debate, Ifill's objectivity was questioned by conservative talk radio, blogs and cable news programs as well as some independent media analysts because of her book The Breakthrough, which was scheduled to be released on Inauguration Day 2009 but whose contents had not been disclosed to the debate commission or the campaigns. The book was mentioned in the Washington Times and appeared in trade catalogs as early as July 2008, well before Ifill was selected by the debate committee. Several analysts viewed Ifill's book as creating a conflict of interest, including Kelly McBride of The Poynter Institute for Media Studies, who said, “Obviously the book will be much more valuable to her if Obama is elected.” McCain said in an interview on Fox News Channel, "I think she will do a totally objective job because she is a highly respected professional." Asked about the forthcoming book, McCain responded, "Does this help...if she has written a book that's favorable to Senator Obama? Probably not. But I have confidence that Gwen Ifill will do a professional job."

To critics, Ifill responded, "I've got a pretty long track record covering politics and news, so I'm not particularly worried that one-day blog chatter is going to destroy my reputation. The proof is in the pudding. They can watch the debate tomorrow night and make their own decisions about whether or not I've done my job."

After the debate, Ifill received praise for her performance. The Boston Globe reported that she "is receiving high marks for equal treatment of the candidates."

Ifill's moderation of the debates won her pop-culture recognition when the debates were parodied on Saturday Night Live with host and musical guest Queen Latifah portraying Ifill.

Death

Ifill had been battling breast cancer for some time. She passed away quietly surrounded by friends on November 14, 2016.. Ifill was 61.

Wikipedia

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Favorite tweets

I cannot think of a more fitting replacement. #BarbaraJohns is an American hero. At 16, she defied school leaders and led a walkout at her segregated HS in Virginia. Her action led to the Virginia Brown v Bd case. Learn abt this extraordinary activist https://t.co/rhTqZLXNIk https://t.co/LZUiTkvqgj

— Sherrilyn Ifill (@Sifill_LDF) December 22, 2020

from http://twitter.com/Sifill_LDF via IFTTT

0 notes

Link

On March 15, 2019, legions of Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s admirers celebrated her 86th birthday by dropping to the ground and grinding out the Super Diva’s signature push-ups on the steps of courthouses around the country.

This unusual tribute to a Supreme Court justice was one of the many ways a new generation has shown the love to the five-foot tall legal giant who made the lives they live possible. But by Sept. 18, her iron will and gritty determination was no longer enough to propel her to court. Ginsburg died on Friday at the age of 87 of complications from metastatic pancreatic cancer, according to a statement released by the Supreme Court, per the Associated Press.

In the early ’70s—when Gloria Steinem was working underground as a Playboy Bunny to expose sexism, and Betty Friedan was writing a feminist manifesto about “the problem with no name”—Ginsburg named the problem, briefed it, and argued it before the Supreme Court of the United States.

She was 37 then, on the receiving end of so much of the discrimination she would work to end, and she was just undertaking her first job as a litigator—as co-director of the Women’s Rights Project of the American Civil Liberties Union. In her “very precise” way, as Justice Harry Blackmun put it, she studied title, chapter, clause, and footnote of the legal canon that kept women down and overturned those that discriminated on the basis of sex in five landmark cases that extended the 14th Amendment’s equal rights clause to women. In that long, hard slog, she employed some novel devices, using “gender” (so as not to distract male jurists with the word “sex”) and representing harmed male plaintiffs when she could find one (to show that discrimination hurts everyone). And she never raised her voice.

When she was done, a widower could get the same Social Security benefits as a woman and a woman could claim the same military housing allowance as a man. A woman could cut a man’s hair, buy a drink at the same age, administer an estate, and serve on a jury.

By the time she left the ACLU, and before she donned her first black robe, Ginsburg had brought about a small revolution in how women were treated, wiping close to 200 laws that discriminated off the books. Over the next decades, first as a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, appointed by President Jimmy Carter in 1980, and then as the second woman on the Supreme Court, appointed by President Bill Clinton in 1993, she would become to women what Thurgood Marshall was to African Americans. She employed the same clause in the 14th Amendment he used to free former slaves to extend protection to the mentally ill who wanted to live outside institutions, gays who wanted to marry, immigrants who lived in fear, and, of course, females: those who wanted to be cadets at the Virginia Military Institute, have access to abortion, and, when pregnant, not be fired if they couldn’t perform duties their condition made, temporarily, impossible.

Her fans’ courthouse celebration was also a plea for the bionic Ginsburg to carry on, at least until the 2020 election. There was high anxiety when she fell asleep at the State of the Union in 2015 (a case of enjoying a fine California wine brought by Justice Anthony Kennedy to the justices pre-speech dinner) and even more when she missed the court’s 2019 opening session in January, her first such absence in 26 years. She hadn’t fully recovered from surgery to remove three cancerous nodules from her lungs. But she took her seat as the senior justice next to Chief Justice John Roberts in mid-February, picking up her full caseload. That following summer, she went through radiation to treat a cancerous tumor on her pancreas, her fourth brush with cancer. In July 2020, she announced that cancer had returned yet again. Despite receiving chemotherapy for lesions on her liver, the 87-year-old reasserted that she was still “fully able” to continue serving on the Supreme Court.

Collection of the Supreme Court of the United StatesAugust 2, 1935 Childhood photograph of Ruth Bader taken when she was two years old.

Baton-twirling bookworm

Joan Ruth Bader was born in 1933 in Brooklyn and came of age during the Holocaust, “a first-generation American on my father’s side, barely second-generation on my mother’s … What has become of me could happen only in America,” she said at her confirmation hearing.

True enough, but what would become of her was a long time coming. In an enthralling biography, Jane Sherron De Hart describes schoolgirl Ruth, who twirled a baton but was such a bookworm she tripped and broke her nose reading while walking. Her mother, who convinced her she could do anything, died just before Ruth, the class valedictorian, graduated and headed off to Cornell. There she met the tall, handsome Martin Ginsburg, and married him the minute she graduated Phi Beta Kappa—the first person, she said, who “loved me for my brain.” She’d been accepted to Harvard Law, where Marty was already enrolled. She calls “meeting Marty by far the most fortunate thing that ever happened to me.”

What happened next is proof of her maxim that “a woman can have it all, just not all at once.” Marty was called up to active duty, so instead of studying torts in Cambridge, Ginsburg found herself working as a claims examiner at the Social Security Administration in Fort Sill, Oklahoma—that is, until she was demoted with a pay cut for working while pregnant.

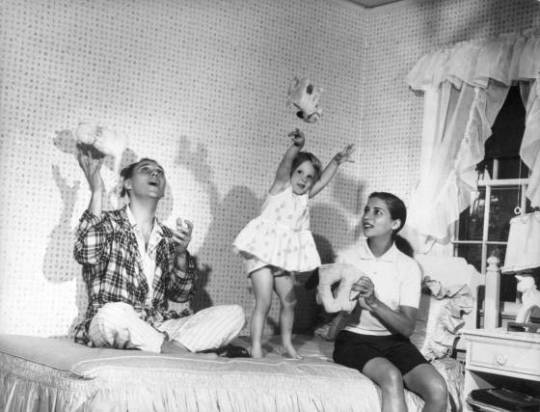

Collection of the Supreme Court of the United StatesSummer 1958 Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Martin Ginsburg play with their three-year old daughter, Jane, in her bedroom at Martin’s parents’ home in Rockville Centre, N.Y

Life threw another wrench into the works when both were back at Harvard with a baby girl, and Marty was stricken with a rare testicular cancer. Ruth went to class for both of them, typing up his notes and papers as well as her own, getting along on even less sleep than your usual new mother, all while being scolded for taking up a man’s seat by Dean Erwin Grisold. When her husband graduated and was offered a prestigious job at a white shoe law firm in New York, she gave up her last year at Harvard to finish at Columbia.

Once again, she felt the sting of the discrimination. Despite being the first student ever to serve on both the Harvard and Columbia Law Reviews and graduating at the top of her class, she couldn’t get a job at a premier law firm or one of the Supreme Court clerkships that went so easily to male classmates who ranked below her. According to DeHart, Judge Felix Frankfurter fretted a woman clerk might wear pants to chambers. Without bitterness, she calls anger a useless emotion; she noted that in the ’50s, “to be a woman, a Jew and a mother to boot—that combination was a bit too much.”

Librado Romero—The New York Times/Redux 1972 Ruth Bader Ginsburg in New York, when she was named a professor at Columbia Law School.

Battling discrimination

She didn’t get outwardly angry and only, after many years, got even. She took a lower court clerkship, researched civil procedure (and equality of the sexes in practice) in Sweden and wrote a book on the subject—in Swedish! She returned home to teach at the Newark campus of Rutgers Law, where she co-founded the Women’s Rights Law Reporter. Despite being a progressive school, discrimination struck again. She learned she didn’t earn the same as a male colleague because, the dean explained, “he has a wife and two children to support. You have a husband with a good paying job in New York.” No wonder then, when she found herself surprisingly (given her husband’s medical history) but happily pregnant again, she took no chances and hid it.

After the birth of her son, James, she became a tenured professor at Columbia, co-authored the first case book on discrimination law, a work in progress as she changed much of it while litigating for the ACLU, until in 1980 she joined the Court of Appeals.

Then, in 1993, President Bill Clinton was elected and he wanted a Cabinet, and by extension a Supreme Court, that looked like America. Ginsburg was on the list, but so were a dozen others and she wasn’t at the top.

Even Clinton’s deliberations weren’t without a peculiar form of discrimination as he worried, “the women are against her.” He was right. To the feminists of the ’90s—who might be ignored by the White House if it weren’t for Ginsburg’s decades of opening doors—she was yesterday. The judge methodically chipping away at bias, without burning a bra or tossing a high heel, looked plodding and uninspiring; her friendship with her colleague on the district court, Scalia, looked suspect.

Enter Marty. “I wasn’t very good at promotion, but Marty was,” she told the late Gwen Ifill, a PBS anchor. “He was tireless”—and beloved among lawyers, professors, and politicians. Women came around, reminded that she was a pioneer in their fight to overcome the patriarchy and a steadfast supporter of abortion rights, despite acknowledging in an interview that the country might be politically better off if the states had continued to legalize abortion rather than have Roe v. Wade as a singular target of its foes. Ginsburg was confirmed 96 to 3.

Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States August 10, 1993 Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg is sworn in as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court. From left to right stand President Bill Clinton, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Martin Ginsburg, and Chief Justice William Rehnquist.

David Hume Kennerly—Getty Images March 2001 The only two female Justices of the U.S. Supreme Court, Sandra Day O’Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, pose for a portrait in Statuary Hall, surrounded by statues of men at the U.S. Capitol Building in Washington, D.C. The two Justices were preparing to address a meeting of the Congressional Women’s Caucus.

The Great Dissenter

She didn’t disappoint. In one case after another, she asked the right questions (and usually the first one), cobbled together majorities and wrote elegantly reasoned opinions: striking down stricter requirements for abortion clinics designed to make the procedure extinct (Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt), and approving gay marriage (Obergefell v. Hodges), making the point during oral argument that if you can’t refuse a 70-year-old couple marriage because they can’t procreate, how could you use that excuse to deprive a gay one.

But it was her minority — not her majority — opinions that made her beloved to a new generation of women. As the court tilted right in 2006 after the retirement of Sandra Day O’Connor, Ginsburg started to read, not just file, her dissents to explain to the majority why they were wrong in hopes that “if the court has a blind spot today, its eyes will be open tomorrow.”

Here was a shy, understated incrementalist suddenly becoming the Great Dissenter. In Shelby County v. Holder, she said that relieving errant states of the close scrutiny of the Voting Rights Act was like “throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.” In Hobby Lobby, she was aghast that the court would deny costly contraception coverage to working women “because of someone else’s religious beliefs.” In the Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber equal pay case, she asked how her brethren could penalize the plaintiff, who only got evidence of the disparity from an anonymous note, for missing a 180-day filing deadline given that salaries are kept secret. One person whose eyes were opened was Barack Obama. His first piece of legislation in 2009 was the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act.

Karsten Moran—ReduxA woman attending the New York City Women’s March wears a t-shirt featuring Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg on Jan. 20, 2018.

Becoming the Notorious RBG

Ginsburg’s womansplaining caught the attention of New York University law student Shana Knizhnik, who uploaded Ginsburg’s dissents to Tumblr. Overnight, a younger generation of women, and their mothers and grandmothers, were reminded of what Ginsburg had done for them. Knizhnik joined with reporter Irin Carmon to write Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg. The justice was soon a recurring character on Saturday Night Live, with a hyperkinetic Kate McKinnon issuing blistering “Ginsburns.” The justice’s 2016 memoir, My Own Words, was a New York Times bestseller. There were more books — adult, children’s and coloring. In 2018, Hollywood released a major motion picture, On the Basis of Sex, and the documentary RBG, which won an Emmy. Store shelves groan with merch: mugs (you Bader believe it), onesies (The Ruth will set you free), tote bags, bobblehead dolls, and action figures, one of the latest from her cameo in Lego Movie 2, produced by none other than Trump Administration Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin.

All this late-arriving fame rested uneasily on the shoulders of Ginsburg, who accepted it with dignity and took some pleasure at grandchildren’s shock that “so many people want to take my picture.” She kept a large supply of Notorious RBG T-shirts as a party favor for visitors.

At the heart of Hollywood’s treatment of Ginsburg wasn’t only the case Marty and his wife worked on together—an appeal of an IRS ruling—but a marriage of extraordinary compatibility and mutual support. After he recovered from cancer and had become a sought-after lawyer, he eagerly took on his share of domestic duties, which included feeding the children since, according to former Solicitor General Ted Olson, ��Ruth wanted nothing whatsoever to do with the kitchen.” Marty was the fun parent (Ginsburg joked at her confirmation hearing that the children kept a log called “Mommy Laughed”) and a big-hearted host who happily roasted “Bambi,” Ruth’s name for whatever Scalia, her opera buddy, bagged on his last hunting trip. The pair were the subject of an actual comic opera, Scalia/Ginsburg, in which one scene depicts the over-emoting Scalia, locked in a dark room for excessive dissenting, and Ginsburg descending through a glass ceiling to rescue him.

A fellow justice said that neither Ginsburg would be who they were without the other. Marty once joked about being second banana: “As a general rule, my wife does not give me any advice about cooking and I do not give her any advice about the law. This seems to work quite well on both sides.” De Hart reprints the letter Marty put in a drawer in the bedside table as he was dying from a recurrence of his cancer. He was the “most fortunate” part of her life.

Marty lived to see his wife recognized beyond what the two imagined when they agreed to marry and be lawyers together, but died just before a slight she suffered for following him to New York was righted. In 2011, she was awarded an honorary degree from Harvard Law that Dean Griswold had denied her for taking her last credits at Columbia.

The longer she lived, the wider her reach and the deeper the appreciation for her years on the bench. At the opening concert of the National Symphony Orchestra in Sept. 2019, Kennedy Center chair David Rubinstein introduced the dignitaries in the audience. When he got to the justice, women rose to applaud her. Then, the men quickly joined in until everyone in the hall was standing, looking up at the balcony, cheering and whistling, as if they’d come to tell her that they knew what she had done for them, not to hear Shostakovich’s Piano Concerto #2.

This wasn’t an audience of liberals, but a cross-section of the capital touched by a once-young lawyer who saw unfairness and quietly tried to end it during her 60 years of public service.

Throughout the decades, Ginsburg quietly persisted—through discrimination she would seek to end, through the death of Marty, through more illness and debilitating treatments than any one person should have to endure—without complaint, holding on and out, until sheer will was no longer enough.

from TIME https://ift.tt/2RHBzbQ

0 notes

Text

New top story from Time: Ruth Bader Ginsburg Has Died. She Leaves Behind a Vital Legacy for Women — and Men

On March 15, 2019, legions of Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s admirers celebrated her 86th birthday by dropping to the ground and grinding out the Super Diva’s signature push-ups on the steps of courthouses around the country.

This unusual tribute to a Supreme Court justice was one of the many ways a new generation has shown the love to the five-foot tall legal giant who made the lives they live possible. But by Sept. 18, her iron will and gritty determination was no longer enough to propel her to court. Ginsburg died on Friday at the age of 87 of complications from metastatic pancreatic cancer, according to a statement released by the Supreme Court, per the Associated Press.

In the early ’70s—when Gloria Steinem was working underground as a Playboy Bunny to expose sexism, and Betty Friedan was writing a feminist manifesto about “the problem with no name”—Ginsburg named the problem, briefed it, and argued it before the Supreme Court of the United States.

She was 37 then, on the receiving end of so much of the discrimination she would work to end, and she was just undertaking her first job as a litigator—as co-director of the Women’s Rights Project of the American Civil Liberties Union. In her “very precise” way, as Justice Harry Blackmun put it, she studied title, chapter, clause, and footnote of the legal canon that kept women down and overturned those that discriminated on the basis of sex in five landmark cases that extended the 14th Amendment’s equal rights clause to women. In that long, hard slog, she employed some novel devices, using “gender” (so as not to distract male jurists with the word “sex”) and representing harmed male plaintiffs when she could find one (to show that discrimination hurts everyone). And she never raised her voice.

When she was done, a widower could get the same Social Security benefits as a woman and a woman could claim the same military housing allowance as a man. A woman could cut a man’s hair, buy a drink at the same age, administer an estate, and serve on a jury.

By the time she left the ACLU, and before she donned her first black robe, Ginsburg had brought about a small revolution in how women were treated, wiping close to 200 laws that discriminated off the books. Over the next decades, first as a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, appointed by President Jimmy Carter in 1980, and then as the second woman on the Supreme Court, appointed by President Bill Clinton in 1993, she would become to women what Thurgood Marshall was to African Americans. She employed the same clause in the 14th Amendment he used to free former slaves to extend protection to the mentally ill who wanted to live outside institutions, gays who wanted to marry, immigrants who lived in fear, and, of course, females: those who wanted to be cadets at the Virginia Military Institute, have access to abortion, and, when pregnant, not be fired if they couldn’t perform duties their condition made, temporarily, impossible.

Her fans’ courthouse celebration was also a plea for the bionic Ginsburg to carry on, at least until the 2020 election. There was high anxiety when she fell asleep at the State of the Union in 2015 (a case of enjoying a fine California wine brought by Justice Anthony Kennedy to the justices pre-speech dinner) and even more when she missed the court’s 2019 opening session in January, her first such absence in 26 years. She hadn’t fully recovered from surgery to remove three cancerous nodules from her lungs. But she took her seat as the senior justice next to Chief Justice John Roberts in mid-February, picking up her full caseload. That following summer, she went through radiation to treat a cancerous tumor on her pancreas, her fourth brush with cancer. In July 2020, she announced that cancer had returned yet again. Despite receiving chemotherapy for lesions on her liver, the 87-year-old reasserted that she was still “fully able” to continue serving on the Supreme Court.

Collection of the Supreme Court of the United StatesAugust 2, 1935 Childhood photograph of Ruth Bader taken when she was two years old.

Baton-twirling bookworm

Joan Ruth Bader was born in 1933 in Brooklyn and came of age during the Holocaust, “a first-generation American on my father’s side, barely second-generation on my mother’s … What has become of me could happen only in America,” she said at her confirmation hearing.

True enough, but what would become of her was a long time coming. In an enthralling biography, Jane Sherron De Hart describes schoolgirl Ruth, who twirled a baton but was such a bookworm she tripped and broke her nose reading while walking. Her mother, who convinced her she could do anything, died just before Ruth, the class valedictorian, graduated and headed off to Cornell. There she met the tall, handsome Martin Ginsburg, and married him the minute she graduated Phi Beta Kappa—the first person, she said, who “loved me for my brain.” She’d been accepted to Harvard Law, where Marty was already enrolled. She calls “meeting Marty by far the most fortunate thing that ever happened to me.”

What happened next is proof of her maxim that “a woman can have it all, just not all at once.” Marty was called up to active duty, so instead of studying torts in Cambridge, Ginsburg found herself working as a claims examiner at the Social Security Administration in Fort Sill, Oklahoma—that is, until she was demoted with a pay cut for working while pregnant.

Collection of the Supreme Court of the United StatesSummer 1958 Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Martin Ginsburg play with their three-year old daughter, Jane, in her bedroom at Martin’s parents’ home in Rockville Centre, N.Y

Life threw another wrench into the works when both were back at Harvard with a baby girl, and Marty was stricken with a rare testicular cancer. Ruth went to class for both of them, typing up his notes and papers as well as her own, getting along on even less sleep than your usual new mother, all while being scolded for taking up a man’s seat by Dean Erwin Grisold. When her husband graduated and was offered a prestigious job at a white shoe law firm in New York, she gave up her last year at Harvard to finish at Columbia.

Once again, she felt the sting of the discrimination. Despite being the first student ever to serve on both the Harvard and Columbia Law Reviews and graduating at the top of her class, she couldn’t get a job at a premier law firm or one of the Supreme Court clerkships that went so easily to male classmates who ranked below her. According to DeHart, Judge Felix Frankfurter fretted a woman clerk might wear pants to chambers. Without bitterness, she calls anger a useless emotion; she noted that in the ’50s, “to be a woman, a Jew and a mother to boot—that combination was a bit too much.”

Librado Romero—The New York Times/Redux 1972 Ruth Bader Ginsburg in New York, when she was named a professor at Columbia Law School.

Battling discrimination

She didn’t get outwardly angry and only, after many years, got even. She took a lower court clerkship, researched civil procedure (and equality of the sexes in practice) in Sweden and wrote a book on the subject—in Swedish! She returned home to teach at the Newark campus of Rutgers Law, where she co-founded the Women’s Rights Law Reporter. Despite being a progressive school, discrimination struck again. She learned she didn’t earn the same as a male colleague because, the dean explained, “he has a wife and two children to support. You have a husband with a good paying job in New York.” No wonder then, when she found herself surprisingly (given her husband’s medical history) but happily pregnant again, she took no chances and hid it.

After the birth of her son, James, she became a tenured professor at Columbia, co-authored the first case book on discrimination law, a work in progress as she changed much of it while litigating for the ACLU, until in 1980 she joined the Court of Appeals.

Then, in 1993, President Bill Clinton was elected and he wanted a Cabinet, and by extension a Supreme Court, that looked like America. Ginsburg was on the list, but so were a dozen others and she wasn’t at the top.

Even Clinton’s deliberations weren’t without a peculiar form of discrimination as he worried, “the women are against her.” He was right. To the feminists of the ’90s—who might be ignored by the White House if it weren’t for Ginsburg’s decades of opening doors—she was yesterday. The judge methodically chipping away at bias, without burning a bra or tossing a high heel, looked plodding and uninspiring; her friendship with her colleague on the district court, Scalia, looked suspect.

Enter Marty. “I wasn’t very good at promotion, but Marty was,” she told the late Gwen Ifill, a PBS anchor. “He was tireless”—and beloved among lawyers, professors, and politicians. Women came around, reminded that she was a pioneer in their fight to overcome the patriarchy and a steadfast supporter of abortion rights, despite acknowledging in an interview that the country might be politically better off if the states had continued to legalize abortion rather than have Roe v. Wade as a singular target of its foes. Ginsburg was confirmed 96 to 3.

Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States August 10, 1993 Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg is sworn in as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court. From left to right stand President Bill Clinton, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Martin Ginsburg, and Chief Justice William Rehnquist.

David Hume Kennerly—Getty Images March 2001 The only two female Justices of the U.S. Supreme Court, Sandra Day O’Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, pose for a portrait in Statuary Hall, surrounded by statues of men at the U.S. Capitol Building in Washington, D.C. The two Justices were preparing to address a meeting of the Congressional Women’s Caucus.

The Great Dissenter

She didn’t disappoint. In one case after another, she asked the right questions (and usually the first one), cobbled together majorities and wrote elegantly reasoned opinions: striking down stricter requirements for abortion clinics designed to make the procedure extinct (Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt), and approving gay marriage (Obergefell v. Hodges), making the point during oral argument that if you can’t refuse a 70-year-old couple marriage because they can’t procreate, how could you use that excuse to deprive a gay one.

But it was her minority — not her majority — opinions that made her beloved to a new generation of women. As the court tilted right in 2006 after the retirement of Sandra Day O’Connor, Ginsburg started to read, not just file, her dissents to explain to the majority why they were wrong in hopes that “if the court has a blind spot today, its eyes will be open tomorrow.”

Here was a shy, understated incrementalist suddenly becoming the Great Dissenter. In Shelby County v. Holder, she said that relieving errant states of the close scrutiny of the Voting Rights Act was like “throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.” In Hobby Lobby, she was aghast that the court would deny costly contraception coverage to working women “because of someone else’s religious beliefs.” In the Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber equal pay case, she asked how her brethren could penalize the plaintiff, who only got evidence of the disparity from an anonymous note, for missing a 180-day filing deadline given that salaries are kept secret. One person whose eyes were opened was Barack Obama. His first piece of legislation in 2009 was the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act.

Karsten Moran—ReduxA woman attending the New York City Women’s March wears a t-shirt featuring Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg on Jan. 20, 2018.

Becoming the Notorious RBG

Ginsburg’s womansplaining caught the attention of New York University law student Shana Knizhnik, who uploaded Ginsburg’s dissents to Tumblr. Overnight, a younger generation of women, and their mothers and grandmothers, were reminded of what Ginsburg had done for them. Knizhnik joined with reporter Irin Carmon to write Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg. The justice was soon a recurring character on Saturday Night Live, with a hyperkinetic Kate McKinnon issuing blistering “Ginsburns.” The justice’s 2016 memoir, My Own Words, was a New York Times bestseller. There were more books — adult, children’s and coloring. In 2018, Hollywood released a major motion picture, On the Basis of Sex, and the documentary RBG, which won an Emmy. Store shelves groan with merch: mugs (you Bader believe it), onesies (The Ruth will set you free), tote bags, bobblehead dolls, and action figures, one of the latest from her cameo in Lego Movie 2, produced by none other than Trump Administration Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin.

All this late-arriving fame rested uneasily on the shoulders of Ginsburg, who accepted it with dignity and took some pleasure at grandchildren’s shock that “so many people want to take my picture.” She kept a large supply of Notorious RBG T-shirts as a party favor for visitors.

At the heart of Hollywood’s treatment of Ginsburg wasn’t only the case Marty and his wife worked on together—an appeal of an IRS ruling—but a marriage of extraordinary compatibility and mutual support. After he recovered from cancer and had become a sought-after lawyer, he eagerly took on his share of domestic duties, which included feeding the children since, according to former Solicitor General Ted Olson, “Ruth wanted nothing whatsoever to do with the kitchen.” Marty was the fun parent (Ginsburg joked at her confirmation hearing that the children kept a log called “Mommy Laughed”) and a big-hearted host who happily roasted “Bambi,” Ruth’s name for whatever Scalia, her opera buddy, bagged on his last hunting trip. The pair were the subject of an actual comic opera, Scalia/Ginsburg, in which one scene depicts the over-emoting Scalia, locked in a dark room for excessive dissenting, and Ginsburg descending through a glass ceiling to rescue him.

A fellow justice said that neither Ginsburg would be who they were without the other. Marty once joked about being second banana: “As a general rule, my wife does not give me any advice about cooking and I do not give her any advice about the law. This seems to work quite well on both sides.” De Hart reprints the letter Marty put in a drawer in the bedside table as he was dying from a recurrence of his cancer. He was the “most fortunate” part of her life.

Marty lived to see his wife recognized beyond what the two imagined when they agreed to marry and be lawyers together, but died just before a slight she suffered for following him to New York was righted. In 2011, she was awarded an honorary degree from Harvard Law that Dean Griswold had denied her for taking her last credits at Columbia.

The longer she lived, the wider her reach and the deeper the appreciation for her years on the bench. At the opening concert of the National Symphony Orchestra in Sept. 2019, Kennedy Center chair David Rubinstein introduced the dignitaries in the audience. When he got to the justice, women rose to applaud her. Then, the men quickly joined in until everyone in the hall was standing, looking up at the balcony, cheering and whistling, as if they’d come to tell her that they knew what she had done for them, not to hear Shostakovich’s Piano Concerto #2.

This wasn’t an audience of liberals, but a cross-section of the capital touched by a once-young lawyer who saw unfairness and quietly tried to end it during her 60 years of public service.

Throughout the decades, Ginsburg quietly persisted—through discrimination she would seek to end, through the death of Marty, through more illness and debilitating treatments than any one person should have to endure—without complaint, holding on and out, until sheer will was no longer enough.

via https://cutslicedanddiced.wordpress.com/2018/01/24/how-to-prevent-food-from-going-to-waste

0 notes

Photo

New Post has been published on http://techcrunchapp.com/trump-tweets-video-with-white-power-chant-then-deletes-it-snopes-com/

Trump Tweets Video with 'White Power' Chant, Then Deletes It - Snopes.com

WASHINGTON (AP) — President Donald Trump on Sunday tweeted approvingly of a video showing one of his supporters chanting “white power,” a racist slogan associated with white supremacists. He later deleted the tweet and the White House said the president had not heard “the one statement” on the video.

The video appeared to have been taken at The Villages, a Florida retirement community, and showed dueling demonstrations between Trump supporters and opponents.

“Thank you to the great people of The Villages,” Trump tweeted. Moments into the video clip he shared, a man driving a golf cart displaying pro-Trump signs and flags shouts ’white power.” The video also shows anti-Trump protesters shouting “Nazi,” “racist,” and profanities at the Trump backers.

“There’s no question″ that Trump should not have retweeted the video and “he should just take it down,” Sen. Tim Scott, R-S.C., told CNN’s “State of the Union.” Scott is the only Black Republican in the Senate.

“I think it’s indefensible,” he added.

Shortly afterward, Trump deleted the tweet that shared the video. White House spokesman Judd Deere said in a statement that “President Trump is a big fan of The Villages. He did not hear the one statement made on the video. What he did see was tremendous enthusiasm from his many supporters.”

Seniors from The Villages in Florida protesting against each other: pic.twitter.com/Q3GRJCTjEW

— Fifty Shades of Whey (@davenewworld_2) June 27, 2020

The White House did not respond when asked whether Trump condemned the supporter’s comment.

Joe Biden, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, condemned Trump. “We’re in a battle for the soul of the nation — and the President has picked a side. But make no mistake: it’s a battle we will win,” the former vice president tweeted.

Trump’s decision to highlight a video featuring a racist slogan comes amid a national reckoning over race following the deaths of George Floyd and other Black Americans. Floyd, a Black Minneapolis man, died after a white police officer pressed his knee into his neck for several minutes.

Protests against police brutality and bias in law enforcement have occurred across the country following Floyd’s death. There also has also been a push to remove Confederate monuments and to rename military bases that honor figures who fought in the Civil War against the Union. Trump has opposed these efforts.

Trump has been directing his reelection message at the same group of disaffected, largely white voters who backed him four years ago. In doing so, he has stoked racial divisions in the country at a time when tensions are already high. He also has played into anti-immigrant anxieties by falsely claiming that people who have settled in this country commit crimes at greater rates than those who were born in the U.S.

Trump’s tenure in office has appeared to have emboldened white supremacist and nationalist groups, some of whom have embraced his presidency. In 2017, Trump responded to clashes in Charlottesville, Virginia, between white nationalists and counter-protesters by saying there were “very fine people on both sides.”

Sherrilyn Ifill, president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund told CBS’ “Face the Nation” that ”This really is not about the president taking it down. This is about the judgment of the president in putting it up.”

She added, “It’s about what the president believes and it’s time for this country to really face that.”

0 notes

Photo

#BlackHistoryMonthProfile (Day 5)(1 of 3): Gwendolyn L. Ifill ( September 29, 1955 – November 14, 2016) was an American journalist, television newscaster, and author. In 1999, she became the first woman of African descent to host a nationally televised U.S. public affairs program with Washington Week in Review.[3] She was the moderator and managing editor of Washington Week and co-anchor and co-managing editor, with Judy Woodruff, of the PBS NewsHour, both of which air on PBS. Ifill was a political analyst and moderated the 2004 and 2008 vice-presidential debates. She authored the best-selling book The Breakthrough: Politics and Race in the Age of Obama. Ifill went on to work for the Baltimore Evening Sun from 1981 to 1984 and for The Washington Post from 1984 to 1991. She left the Post after being told she wasn't ready to cover Capitol Hill, but was hired by The New York Times, where she covered the White House from 1991 to 1994. Her first job in television was with NBC, where she was the network's Capitol Hill reporter in 1994.In October 1999, she became the moderator of the PBS program Washington Week in Review, the first black woman to host a national political talk show on television. She was a senior correspondent for PBS NewsHour. Ifill appeared on various news shows, including Meet the Press,Face the Nation,The Colbert Report, Charlie Rose, Inside Washington, and The Tavis Smiley Show. In November 2006, she co-hosted Jamestown Live!, an educational webcast commemorating the 400th anniversary of Jamestown, Virginia. https://www.instagram.com/p/B8L-nUpJT474BkG-A6uc4d7LvH05iCUcQLn7-40/?igshid=1mm0gtulj70cl

0 notes

Text

Kansas woman at center of 1954 school segregation ruling dies

TOPEKA, Kan. — Linda Brown, who as a Kansas girl was at the center of the landmark U.S. Supreme Court ruling that struck down racial segregation in schools, has died at age 76.

Her father, Oliver Brown, tried to enroll the family in an all-white school in Topeka, and the case was sparked when he and several black families were turned away. The NAACP’s legal arm brought the lawsuit to challenge segregation in public schools, and Oliver Brown became lead plaintiff in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision by the Supreme Court that ended school segregation.

Sherrilyn Ifill, president and director-counsel at NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., said in a statement that Linda Brown is one of a band of heroic young people who, along with her family, courageously fought to end the ultimate symbol of white supremacy — racial segregation in public schools.

“She stands as an example of how ordinary schoolchildren took center stage in transforming this country. It was not easy for her or her family, but her sacrifice broke barriers and changed the meaning of equality in this country,” Ifill said.

Peaceful Rest Funeral Chapel of Topeka confirmed that Linda Brown died Sunday afternoon. No cause of death was released. Funeral arrangements are pending.

Her sister, Cheryl Brown Henderson, founding president of The Brown Foundation, confirmed the death to The Topeka Capital-Journal . She declined comment from the family.

The landmark case was brought before the Supreme Court by the NAACP’s legal arm to challenge segregation in public schools. It began after several black families in Topeka were turned down when they tried to enroll their children in white schools near their homes. The lawsuit was joined with cases from Delaware, South Carolina, Virginia and the District of Columbia.

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that separating black and white children was unconstitutional because it denied black children the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection under the law. “In the field of public education, the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place,” Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote. “Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

The Brown decision overturned the court’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision, which on May 18, 1896, established a “separate but equal” doctrine for black’s in public facilities.

“Sixty-four years ago, a young girl from Topeka, Kansas sparked a case that ended segregation in public schools in America,” Kansas Gov. Jeff Colyer said in a statement. “Linda Brown’s life reminds us that by standing up for our principles and serving our communities we can truly change the world. Linda’s legacy is a crucial part of the American story and continues to inspire the millions who have realized the American dream because of her.”

Brown v. Board was a historic marker in the Civil Rights movement, likely the most high-profile case brought by Thurgood Marshall and the lawyers of the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund in their decade-plus campaign to chip away at the doctrine of “separate but equal.”

“Her legacy is not only here but nationwide,” Kansas Deputy Education Commissioner Dale Dennis said.

Oliver Brown, for whom the case was named, became a minister at a church in Springfield, Missouri. He died of a heart attack in 1961. Linda Brown and her sister founded in 1988 the Brown Foundation for Educational Equity, Excellence and Research.

The foundation says on its webpage that it was established as a living tribute to the attorneys, community organizers and plaintiffs in the landmark Supreme Court decision. Its mission is to build upon their work and keep the ideals of the decision relevant for future generations.

“We are to be grateful for the family that stood up for what is right,” said Democratic state Rep. Annie Kuether of Topeka. “That made a difference to the rest of the world.”

from Tiffany Favorites https://www.politico.com/story/2018/03/26/brown-board-education-segregation-ruling-487317

0 notes

Text

Progress in Virginia still demands some patience

Decades of practice as a Virginia voter have tempered my expectations of progress in any one General Assembly session. And yet...

The Virginia General Assembly is now past the halfway mark of its first session under Democratic control since the 2021 session, and I have to admit that I expected a little more out of my state’s legislature now that Republicans can’t quietly sink decent bills in committees as they did in the House of Delegates in the previous two-year session. It’s not that the Western Hemisphere’s oldest…

View On WordPress

#anti-SLAPP#campaign finance#crossover day#direct tax prep#Glenn Youngkin#House of Delegates#leaf blowers#Richmond#Virginia Democrats#Virginia General Assembly#Virginia iFile#Virginia Senate

0 notes

Text

Linda Brown, central figure in school segregation case, dies

New Post has been published on https://goo.gl/8eN9om

Linda Brown, central figure in school segregation case, dies

TOPEKA, Kan. /March 26, 2018 (AP)(STL.News) — As a girl in Kansas, Linda Brown’s father tried to enroll her in an all-white school in Topeka. He and several black families were turned away, sparking the Brown v. Board of Education case that challenged segregation in public schools.

A 1954 decision by the U.S. Supreme Court followed, striking down racial segregation in schools and cementing Linda Brown’s place in history as a central figure in the landmark case.

Funeral officials in Topeka said Brown died Sunday at age 75. A cause of death was not released. Arrangements were pending at Peaceful Rest Funeral Chapel.

Her sister, Cheryl Brown Henderson, founding president of The Brown Foundation, confirmed the death to The Topeka Capital-Journal. She declined comment from the family.

Sherrilyn Ifill, president and director-counsel at NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund Inc., said in a statement that Linda Brown is one of a band of heroic young people who, along with her family, courageously fought to end the ultimate symbol of white supremacy — racial segregation in public schools.

“She stands as an example of how ordinary schoolchildren took center stage in transforming this country. It was not easy for her or her family, but her sacrifice broke barriers and changed the meaning of equality in this country,” Ifill said in a statement.

The NAACP’s legal arm brought the lawsuit to challenge segregation in public schools before the Supreme Court, and Brown’s father, Oliver Brown, became lead plaintiff.

Several black families in Topeka were turned down when they tried to enroll their children in white schools near their homes. The lawsuit was joined with cases from Delaware, South Carolina, Virginia and the District of Columbia.

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that separating black and white children was unconstitutional because it denied black children the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection under the law. “In the field of public education, the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place,” Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote. “Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

The Brown decision overturned the court’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision, which on May 18, 1896, established a “separate but equal” doctrine for blacks in public facilities.

“Sixty-four years ago, a young girl from Topeka, Kansas sparked a case that ended segregation in public schools in America,” Kansas Gov. Jeff Colyer said in a statement. “Linda Brown’s life reminds us that by standing up for our principles and serving our communities we can truly change the world. Linda’s legacy is a crucial part of the American story and continues to inspire the millions who have realized the American dream because of her.”

Brown v. Board was a historic marker in the civil rights movement, likely the most high-profile case brought by Thurgood Marshall and the lawyers of the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund in their decade-plus campaign to chip away at the doctrine of “separate but equal.”

“Her legacy is not only here but nationwide,” Kansas Deputy Education Commissioner Dale Dennis said.

Oliver Brown, for whom the case was named, became a minister at a church in Springfield, Missouri. He died of a heart attack in 1961. Linda Brown and her sister founded in 1988 the Brown Foundation for Educational Equity, Excellence and Research.

The foundation says on its webpage that it was established as a living tribute to the attorneys, community organizers and plaintiffs in the landmark Supreme Court decision. Its mission is to build upon their work and keep the ideals of the decision relevant for future generations.

“We are to be grateful for the family that stood up for what is right,” said Democratic state Rep. Annie Kuether of Topeka. “That made a difference to the rest of the world.”

___

By Associated Press – published on STL.News by St. Louis Media, LLC (A.S)

___

0 notes

Link

A civil rights group filed a lawsuit Monday that seeks to stop election officials from declaring a winner in a state House of Delegates race that could determine which party controls the chamber. The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund filed a lawsuit in Stafford County nearly a week after Election Day, claiming that local election officials gave “conflicting and misleading instructions” to voters who had cast provisional ballots. “At the heart of this lawsuit is the ability of voters to have their voices heard,” said Sherrilyn Ifill, president of the legal defense fund. “When extraordinary steps are taken to impede the electoral process, we must act swiftly to ensure that each and every citizen has a meaningful opportunity to participate.” At the heart of the lawsuit is the race to fill the House seat being vacated by retiring Speaker William J. Howell (R-Stafford). Republican Robert Thomas is ahead of Joshua Cole by 86 votes.

0 notes

Text

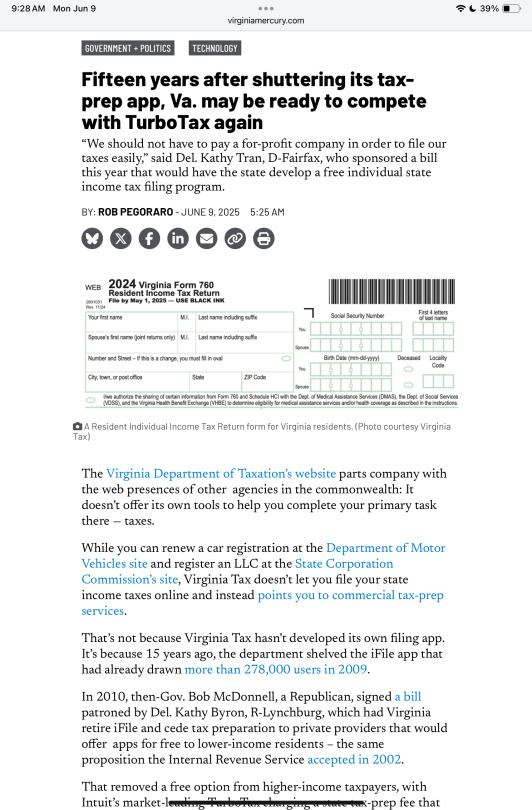

Why I'm back to filing our Virginia taxes on paper

One of the little luxuries of life in Virginia is having more time to file state tax returns–ours, unlike those of most states, aren’t due until the first business day of May. And one of the little indignities of life in Virginia is having this annual ritual offer a reminder of how badly our state got suckered by the tax prep industry’s “Free File” con. Rewind 20 years, and the Virginia…

View On WordPress

#crony capitalism#direct tax prep#e-file taxes#Free File#Free Fillable Forms#Intuit#paper tax forms#rent seeking#tax prep#Virginia form 760#Virginia iFile#Virginia taxes

0 notes

Text

Weekly output: your browser choices, how Virginia got suckered by Intuit

I didn’t have to file taxes, file for an extension on taxes, or make quarterly estimated-tax payments this week. So it had that much going for it.

4/14/2020: Chrome, Edge, Safari or Firefox: Which browser won’t crash your computer when working from home?, USA Today

My editor asked if I could assess which browsers would leave the biggest dent in a home computer’s processor and memory, so I tested…

View On WordPress

#browser CPU time#browser memory usage#browser privacy#browser processor usage#Chrome#Firefox#Free Fillable Forms#Intuit#Microsoft Edge#Safari#tax prep#Virginia iFile

0 notes