#Vergennes

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The holidays set in

Vergennes, VT

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

so many kids named Finger these days....mamma mia...whata the world-a comin' to?

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Franklin" mini-série créée par Kirk Ellis et Howard Korder - adaptée de "A Great Improvisation: Franklin, France, and the Birth of America" de Stacy Schiff (2005) sur les années passées en Europe de Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) pour aboutir à l'alliance franco-américaine (1778) et à la signature de la "Déclaration d'Indépendance Américaine" avec l'Angleterre (1783) - avec Michael Douglas, Noah Jupe, Ludivine Sagnier, Jeanne Balibar, Eddie Marsan, Daniel Mays, Thibault de Montalembert, Assaâd Bouab, Théodore Pellerin, Olivier Claverie, Tom Hughes, Marc Duret, Lily Dupont, Florence Darel, Aïtor de Calvairac, Sonia Bonny, Robin Renucci, Tom Pezier, Maria-Victoria Dragus et la participation de Romain Brau, mai 2024.

#films#Biopic#RevolutionFrançaise#XVIIIe siècle#Paris#Franklin#BrillonDeJouy#MarieAntoinette#LouisXVI#Beaumarchais#LignivilleHelvetius#LaFayette#Eon#Douglas#Brau#Sagnier#Pellerin#Vergennes#Chaumont#LeRayDeChaumont#Adams#Maurepas#Bancroft#Ellis#Korder#Schiff#Jupe#Balibar#Marsan#Mays

0 notes

Text

I finished watching Franklin the other day and I had to comment on the portrayal of La Fayette throughout the series – while there were some things that I disliked, the show did a really good job portraying La Fayette. I have a lot of notes and screenshots because the show actually included a great number of sweet details. Therefore, I hope you are interested, because we are going into detail.

Franklin – Episode 1

There are two important things happening in this episode with regards to La Fayette: La Fayette’s first meeting with William Temple Franklin and their visit to the club.

The show naturally puts the two Franklins at the center of all the action and this is – with regards to La Fayette, one of the “problems” it suffers from. La Fayette’s departure for America and the whole politics behind it are oversimplified, the show omits his visit to his uncle-in-law in England and its also omits Silas Dean. Dean played a very important role in getting La Fayette to America – arguably more important than Franklin’s role and definitely more important than Temple’s role. La Fayette and Temple knew each other, they exchanged letters and these letters were polite and friendly, but there are none of these overenthusiastic declarations of love that we see in letters to his family, to Adrienne, to Washington or Hamilton for example. In fact, the first letter I could find between the two of them was written by La Fayette on September 14, 1779 – so long after La Fayette’s initial departure. As I already said, the letter is friendly, but not overly so. There might be other letters, that did not survive and many things could have happened, that can not be represented by letters and what is written in them – but I nevertheless think it is safe to assume that the show depicts a deeper friendship between them then there actually was.

With that out of the way, we meet La Fayette for the first time in de Vergenne’s anteroom where Temple is also currently waiting for an audience. When I was watching the show, especially in later episodes, I am not quite sure if it was made clear, that de Vergennes and La Fayette actually had a very warm relationship. Sure, de Vergennes sometimes needed to reign La Fayette in a bit but they were still very affectionate with each other. I saw their interaction in the show always as a mentor-son-thing or some friendly banter but I am not quite sure if you got the same impression when you have not read their letters for example.

Anyway, the real star of this scene was La Fayette’s uniform. This set probably won me over to watch Franklin – because the show actually managed to put La Fayette in the right uniform at the right time!

Here he is wearing the uniform of a Captain from the Noailles regiment. He joined the regiment in 1775 and his commission was a “wedding-gift” from his father-in-law who owned said regiment (although La Fayette had to wait until he turned eighteen to actually be commissioned a Captain). La Fayette wore this uniform in a painting by Louis-Léopold Boilly – although the painting was only done in 1788.

And of course, there was no way the show could do without a scene about La Fayette’s many first names.

I was baptized like a Spaniard. (…) But it was not my fault. And without pretending to deny myself the protection of Marie, Pauls, Joseph, Roch and Yves, I more often called upon Saint Gilbert.

Then we have this absolutely delicious scene of La Fayette dressing Temple up – something very much on brand. @my-deer-friend and I once had a conversation about La Fayette doing something along these lines with John Laurens as well if I am not mistaken.

Next we are taken to a club where La Fayette introduces Temple to his friend Ségur and de Noailles – I really liked it that they were included as well:

And in the course of the conversation there were many interesting aspects raised. For example, there is a reference to La Fayette’s “country-origins”, something that was perceived by his peers back then as way more significant, to the point where he was ridiculed for it, then we today might believe it to be. There was also a spotlight shown on La Fayette’s pursuit for glory and fame, a strong factor in the crafting in his public image and something that was very important for him. I made a post about this here.

We also have La Fayette express his distaste for the British and relay the story about his father’s death. And while I appreciate the background information and motivation, I think that “We hate British” is a bit of an oversimplification – as I said, La Fayette had recently visited his uncle by marriage in England, he was the French ambassador to the British court, and by his own accounts, La Fayette had a blast of a time while in England. I also would like to one day look a bit deeper into the connection La Fayette felt towards his father and his passing, because I believe that he might not have felt quite so strong about the matter.

Lastly, La Fayette comments about his distaste for court rituals. While this was his general opinion, there was one especially notable incident were he purposefully insulted the future Louis XVIII, younger brother of Louis XVI, in order to avoid an appointment to the royal household. I wrote about his little stunt here. He also mentioned that the King at the time, Louis XVI, had forbidden him to sail to America. The logical conclusion: La Fayette bought his own ship.

#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#lafayette#french history#american history#american revolution#history#franklin tv#episode 1#benjamin franklin#william temple franklin#comte de vergennes#tv series#1779#louis xvi#louis xviii#come de ségur#vicomte de noailles#théodore pellerin#really good casting

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I showed M. de Beaumarchais the secret of this binding which consists of two layers of cardboard. You put the secret papers between these two layers; when the edges of the calf are folded over again and the marble endpaper of the book is stuck down over it and left for a day under the press, the cover becomes so smooth and solid that even a bookbinder could not guess the secret. This book is the same one that was given to me by the late M. Tercier on the occasion of my first journeys to Russia"

~ The Chevalière d'Eon to the Comte de Vergennes, 28 May 1776, translated by Antonia White in Memoirs of the Chevalier d'Éon*

*it seems to be one of the legitimate letters included in this book

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

NaNoWriMo Day 7

The writing went better today than yesterday; I slept better and I meditated and exercised in the morning. What kind of exercise? Yoga on the Beach with Elin and 18 minutes on the treadmill gave me energy. I believe you have to achieve homeostasis to be able to keep up with the 50k-word challenge. I can only do the challenge when my body, mind, and spirit are balanced. I did come across a few…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

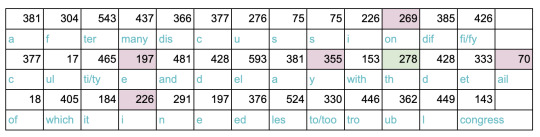

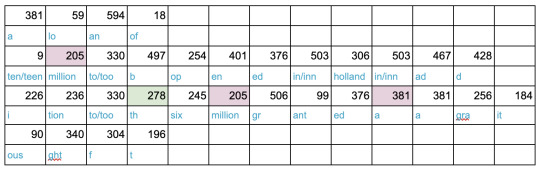

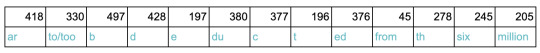

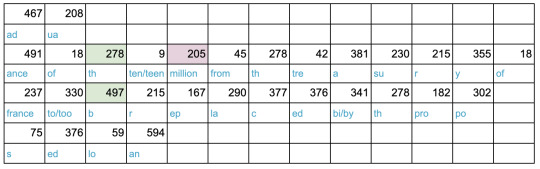

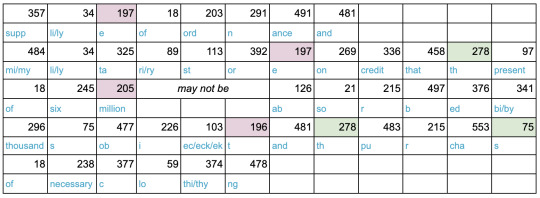

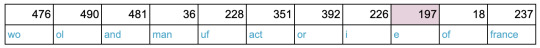

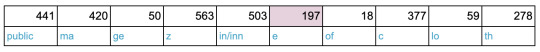

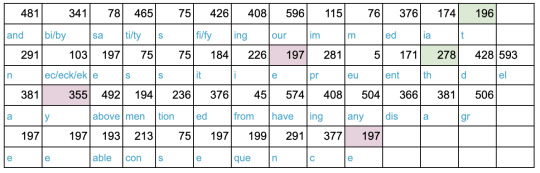

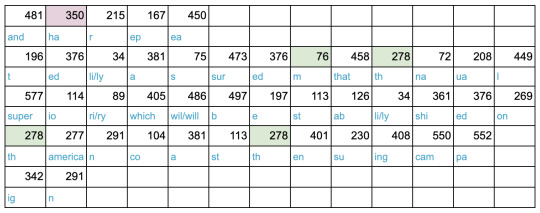

Play along: Amrev codebreaker!

While browsing through some primary materials reading up about John Laurens’ mission to France as special minister to the court of Versailles, I came across a letter that he wrote to the president of the Continental Congress on 9 April 1781 that included a coded message using a numerical cipher.

I took a shot at deciphering it – here’s the process I followed, and you can play along too!

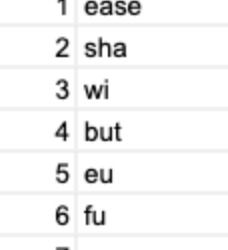

1. The first step, of course, was to determine which specific encryption was being used. After a bit of digging, I came across the immensely useful United States diplomatic codes and ciphers, 1775-1938 by Ralph E Weber. He explains that the cipher in question was “prepared on separate encode and decode sheets, the latter contained 660 printed numbers, with usually 600 words, syllables, and letters of the alphabet scattered randomly throughout the sheet.�� So, for example, the word “congress” is “143”, the syllable “el” is “593” and the letter “r” is “215”. This cipher was an updated and improved version of the one used by Benjamin Tallmadge, and Weber explains that Laurens was the first one to use it. Weber also handily provides the decode table in an appendix.

2. The second step was to design an efficient way to decode the hundreds of numbers Laurens used in his letter, and the obvious answer was my good friend the spreadsheet. I transferred the table from the book to Google Sheets, which was mildly tedious but hugely time-saving later on.

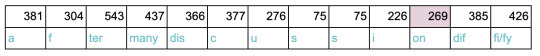

3. Now the fun part! I typed out the numbers from Laurens’ letter, and then used a simple LOOKUP formula to match the number to the decoded text.

The cipher also includes two nuances - an underscore beneath the word means a plural, and an overscore denotes adding an “e” - so I marked these in the cells with pink and green highlights respectively.

4. The final step was correcting a few errors in my table, refining the decoding (some numbers have various iterations to save space, such as 103 which can be any one of “ec/eck/ek” depending on which syllable is needed), and extracting the final text.

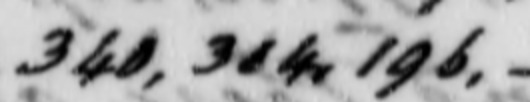

It all reads very smoothly, with the singular exception of “ght-f-t”, which is the way Laurens rendered the word “gift”. The obvious explanation for this mangle is that he mis-wrote 340 (ght) instead of 170 (gi).

That’s definitely 340, 304, 196 which decodes as “ght-f-t”.

While it seems like a strange error to make, bear in mind that the encoding sheet (the one Laurens was using to change plaintext into numbers) would have been listed in alphabetical order to make finding the numbers easier (while the person at the other end has the sheet in numerical order, to reverse the process just as easily). And when we sort alphabetically, we can see that 340 and 170 are right next to each other:

A simple slip to make for someone writing coded letters late at night in low candlelight.

If you want to play along:

Here’s the code/decode spreadsheet.

And here is the transcribed text (underlines for plurals, asterisk for added “e”). I've given the solution under the cut!

I have employed the most unremitting efforts to obtain a prompt and favorable decision relative to the object of my mission_ 381, 304, 543, 437, 366, 377, 276, 75, 75, 226, 269, 385, 426, 377, 17, 465, 197, 481, 428, 593, 381, 355, 153, 278*, 428, 333, 70, 18, 405, 184, 226, 291, 197, 376, 524, 330, 446, 362, 449, 143 The Count de Vergennes communicated to me yesterday his most Christian Majesty's determination to guarantee 381, 59, 594, 18, 9, 205, 330, 497, 254, 401, 376, 503, 306, 503, 467, 428, 226, 236, 330, 278*, 245, 205, 506, 99, 376, 381, 381, 256, 184, 90, 340, 304, 196 ...and the value of the military effects which may be furnished from the Royal Arsenal, 418, 330, 497, 428, 197, 380, 377, 196, 376, 45, 278, 245, 205 I shall use my utmost endeavours to procure an immediate 467, 208, 491, 18, 278*, 9, 205, 45, 278, 42, 381, 230, 215, 355, 18, 237, 330, 497*, 215, 167, 290, 377, 376, 341, 278, 182, 302, 75, 376, 59, 594, and shall renew my solicitations for the 357, 34, 197, 18, 203, 291, 491, 481, 484, 34, 325, 89, 113, 392, 197, 269, 336, 458, 278*, 97, 18, 245, 205 may not be 126, 21, 215, 497, 376, 341, 296, 75, 477, 226, 103, 196, 481, 278*, 483, 215, 553, 75*, 18, 238, 377, 59, 374, 478, the providing this article I fear will be attended with great difficulties and delays as all the 476, 490, 481, 36, 228, 351, 392, 226, 197, 18, 237, are remote from the sea, and there are no 441, 420, 50, 563, 503, 197, 18, 377, 59, 278, suitable to our purposes. The cargo of the Marquis de la Fayette will I hope arrive safe under the convoy of the Alliance_ 481, 341, 78, 465, 75, 426, 408, 596, 115, 76, 376, 174, 196*, 291, 103, 197, 75, 75, 184, 226, 197, 281, 5, 171, 278*, 428, 593, 381, 355, 492, 194, 236, 376, 45, 574, 408, 504, 366, 381, 506, 197, 197, 193, 213, 75, 197, 199, 291, 377, 197 The Marquis de Castries has engaged to make immediate arrangements for the safe transportation of the pecuniary and the other succours destined for the United States_ 481, 350, 215, 167, 450, 196, 376, 34, 381, 75, 473, 376, 76*, 458, 278*, 72, 208, 449, 577, 114, 89, 405, 486, 497, 197, 113, 126, 34, 361, 376, 269, 278*, 277, 291, 104, 381, 113, 278*, 401, 230, 408, 550, 552, 342, 291

Have fun!

I have employed the most unremitting efforts to obtain a prompt and favorable decision relative to the object of my mission_ after many discussions, difficulties and delays with the details of which it is needless to trouble congress.

The Count de Vergennes communicated to me yesterday his most Christian Majesty's determination to guarantee a loan of ten millions to be opened in Holland in addition to the six millions granted as a gracious gift.

...and the value of the military effects which may be furnished from the Royal Arsenal are to be deducted from the six million.

I shall use my utmost endeavours to procure an immediate advance of the ten millions from the treasury of France to be replaced by the proposed loan,

and shall renew my solicitations for the supplies of the ordinance and military stores on credit that the present of six millions may not be absorbed by thousands objects and the purchase of necessary clothing

the providing this article I fear will be attended with great difficulties and delays as all the wool and manufactories of France are remote from the sea, and there are no

public magazines of cloth suitable to our purposes.

The cargo of the Marquis de la Fayette will I hope arrive safe under the convoy of the Alliance_ and by satisfying our immediate necessities prevent the delays above-mentioned from having any disagreeable consequences

The Marquis de Castries has engaged to make immediate arrangements for the safe transportation of the pecuniary and the other succours destined for the United States_ and has repeatedly assured me that the naval superiority which will be established on the American coast the ensuing campaign

#historical john laurens#john laurens#amrev#18th century history#code breaking#it's my birthday so naturally i must give all my beloved mutuals and followers a lil gift#let me know what results you got!!

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fallen Log, Vergennes Watershed Trail, Vermont

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

A very gothic victorian house. Found in Vergennes VT 4/7/24.

41 notes

·

View notes

Note

La Fayette received and wrote quite a number of letters in the context of John Laurens’ mission to France. Two quite interesting letters are form the Comte de Vergennes and Marquis de Castries.

The letter quoted above was not the first that Vergennes wrote La Fayette, he had written before on April 19, 1781 and a comparison of the two letters show how much can change in the span of a month:

Mr. Laurens, moreover, has been very well received by all of the king's ministers, and I dare say that, in this respect, he will make known his complete satisfaction.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 4, April 1, 1781–December 23, 1781, 1981, pp. 47-48.

The second letter is a bit longer and was written by the Marquis de Castries on May 25, 1781. He was the minister of the marine.

I tried to make Colonel Laurens aware, sir, of the value I placed on your recommendation. While I was on my way to Brest, I found him near Lorient just after he arrived from America, and upon my return to this area, my first care was to render him every service at the disposal of my department. He would have liked to know more positively than I could let him what naval forces the king would employ on the coast of North America in this campaign and for what periods of time. I was sorry not to be able to confide that to him, but I could not, because events that are to take place in the warm seas of the Windward and Leeward islands may make a difference both in the times in which the naval forces would be employed in the area that concerns him and in the efforts that would remain for us to make. Moreover, the republican constitution is so unsuited to secrecy that it is dangerous to inform him with too much precision of the dispositions we intend to make. I therefore confined myself to assuring him that in this campaign there would be for a considerable time (at least I have reason not to doubt it) superior forces on the coasts of North America and that it was advisable for our army to be prepared to go into action as soon as it arrived. We had a difference of opinion, Mr. Laurens and I, on the most important objective of your army's operations. Like your French general, I thought that New York, because of the layout and the forces defending it, would be an objective that would require stronger forces than those you could use to attack it. Mr. Laurens nevertheless thinks that this operation will be practicable when you have mastery of the sea. I hope so, but if you were to succeed in freeing your southern provinces (even if Charleston did not fall into your hands), you would nonetheless have had a good campaign. Although Colonel Laurens did not obtain everything he requested, he should be satisfied with the results of his negotiations. He will have the equivalent of twenty million livres in silver money or merchandise; or if we accurately tally up your whole account, we find that if we assume the total expenditure to be made by the government of the United States is thirty-five million and if we balance this expenditure with the country's resources, the result is that, if we add twenty million to the nation's revenues, that sum in total will be left for the army, and assuredly it will suffice for the army you have ready for action. I understand how the poor state of a troop's clothing and arms affects the opinion it has of itself and the opinion other troops have of it. If all the resources being sent to you reach you, you will have an abundance. I hope Mr. Laurens was well served in this respect. It was not my place to help him, since he did not tell me of his confidential affairs, but he consulted M. de Veimerange, who, I imagine, will have been useful to him.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 4, April 1, 1781–December 23, 1781, 1981, pp. 132-134.

I particularly love the phrase “Moreover, the republican constitution is so unsuited to secrecy that it is dangerous to inform him with too much precision of the dispositions we intend to make.” :-)

I read your post about how Laurens was infamous for his diplomacy skills in Europe, but was he ever banned from the country for it? What did his father think about it, especially since the Laurens reputation would be on the line? Did Franklin ever try to do anything about Laurens’ diplomatic skills?

Definitely not banned, but his name was nonetheless a bitter one amongst the higher-ups of France. He had broken French etiquette but it didn't warrant anything that severe, other than being renowned as a total nuisance. In fact, even after leaving France he was still pestering them for more, that Vergennes wrote to Lafayette;

Despite the enormous efforts we are making for the United States, we have not been able to satisfy Mr. Laurens. That officer has much neglected me since I announced to him His Majesty's decision. I know he is complaining rather indiscreetly, and I foresee that he will make every effort to get at least his chief to share his sentiments. Please warn the latter and engage him to instruct his aide-de-camp and, above all, to make him realize the necessity of giving Congress the most temperate account of the mission he carried out in France. I hope we shall not be sent any more such messages; France is not inexhaustible, and it would be absolutely impossible to give them any consideration. We are doing a great deal for the Americans, but they must do their part to help themselves, too.

Source — Comte de Vergennes to Marquis de Lafayette, [May 11, 1781]

He sent a similar report to the Chevalier de La Luzerne and instructed him to minimize any “damage” Laurens may have caused with a biased report to Congress. Funny enough though, after Laurens had taken leave of the court, Vergennes told La Luzerne; “I hope that no one will be sent back here.” [x]

Although I haven't found anything about Henry's knowledge of Laurens's conduct in France. He was taken to London under suspicion of high treason, and imprisoned in the Tower of London on October 6, 1780, until being officially discharged on April 27, 1782. So, I doubt it was easy for the story to be passed around, especially towards Henry who was imprisoned the entire time. Nonetheless, he knew his son's temperament and warned him about discretion in the past—I doubt the story would come as a surprise, but that's not to say he wouldn't be infuriated about it. Especially since the Laurens family did travel through Europe often.

And surprisingly - despite not agreeing with Adams's similar conduct in France - Franklin seemed pleased with Laurens. I suppose because in the end, it worked, no matter the terrible methods. But it could be speculated he probably tried to regulate or give better advice to the hot tempered Laurens during the whole ordeal. Regardless, he even suggested he continue as a diplomat;

Inclos’d is the Order you desire for another Hundred Louis._ Take my Blessing with it, and my Prayers that God may send you safe & well home with your Cargoes. I would not attempt persuading you to quit the military Line, because I think you have the Qualities of Mind and Body that promise your doing great Service & acquiring Honour in that Line. Otherwise I should be happy to See you again here as my Successor; having sometime since written to Congress requesting to be reliev’d, and believing as I firmly do, that they could not put their Affairs in better Hands._

Source — Benjamin Franklin to John Laurens, [May 17, 1781]

But Laurens was firm on his word that he would not be returning to any diplomatic positions;

I take this opportunity of returning Your Excellency my best thanks for the indulgent expressions in the letter which you did me the honor to write previous to my departure from Paris_ I repeat to Your Excellency that it was only a principle of obedience that brought me to Europe on the present occasion_ that I have not the most remote inclination to engage in the diplomatic line_

Source — John Laurens to Benjamin Franklin, [May 22, 1781]

#reblog#yr-obedt-cicero#john laurens#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#comte de vergennes#marquis de castries#letters#1781#french history#american history#american revolution

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Antoine de Favray - Portrait of the Countess of Vergennes in Turkish Attire (fragment)

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

"On nous a toujours trafiqués, vendus comme des porcs, comme des chiens, à quelque pouvoir hostile pour les besoins d'une politique absolument étrangère, toujours désastreuse. Nos maîtres ont toujours été, à part très rares exceptions, à la merci des étrangers. Jamais vraiment des chefs nationaux, toujours plus ou moins maçons, jésuites, papistes, juifs, selon les époques, les vogues du moment, dynasties, mariages, révolutions, insurrections, tractations, toujours des traîtres en définitive. Jamais nos chefs n'ont eu les mains très nettes. Les Mazarins, les demi-Talleyrands, les sous-Mirabeaux, les Vergennes, les Briands, les Poincarés, Jaurès, Clémenceaux, Blums abondent dans notre histoire. Nous sommes les snobs, les engoués d'une certaine forme d'anéantissement par traîtrise."

Louis-Ferdinand Céline, L’école des cadavres, 1938.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

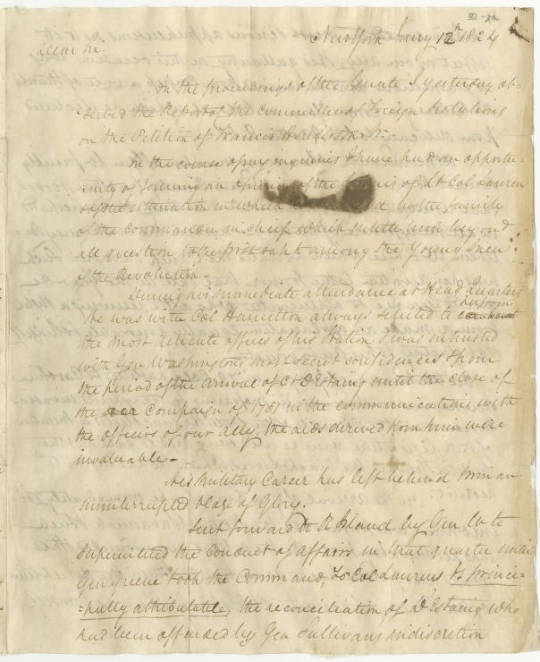

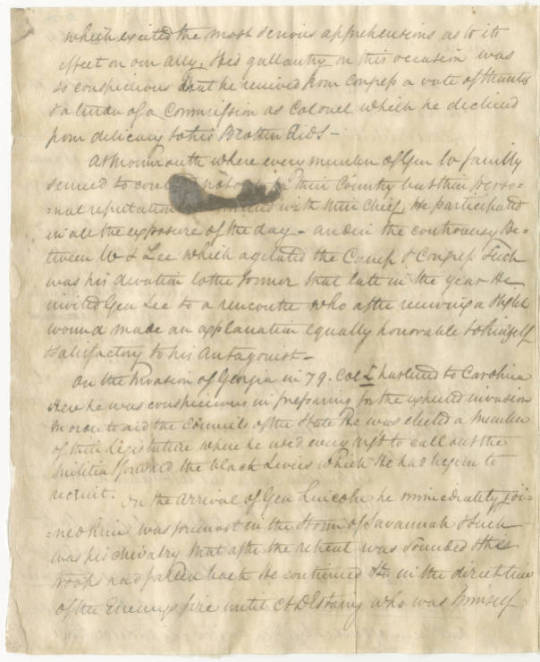

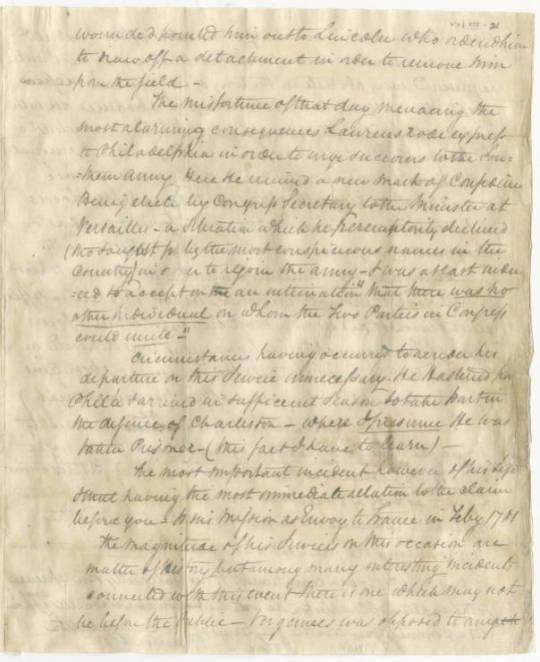

John Church Hamilton to unknown, New York, [January 12, 1824]

Dear Sir: In the proceedings of the Senate, I yesterday ob served the Report of the Committee of Foreign Relations on the Petition of Francis Henderson Jr. In the course of my inquiries I have had an opportunity of forming an opinion of the services of Lieut. Col. Laurens and of the estimation in which he was held by the family of the Commander in chief, which entitles him, beyond all question to the first rank among the young men of the revolution. During his immediate attendance at headquarters he was, with Col. Hamilton always selected to perform the most delicate offices of his station, and was entrusted with Gen. Washington's most secret confidences, and, from the period of the arrival of C D'Estaing, until the close of the campaign of 1781, in the communications with the officers of our ally, the aids derived from him were invaluable. His military career has left behind him an uninterrupted blaze of glory. Sent forward to R Island, by Gen W. to superintend the conduct of affairs in that quarter until Gen. Greene took the command; to Col. Laurens is principally attributed the reconciliation of D'Estaing, who had been offended by Gen. Sullivan's indiscretion, which excited the most serious apprehensions as to its effect on our ally. His gallantry on this occasion was so conspicuous that he received from Congress a vote of thanks and a tender of a commission of Colonel, which he declined from delicacy to his brother aids. At Monmouth where every member of Gen. W's family seemed to contend, not only for their country but for their personal reputation, as connected with their chief, he participated in all the exposure of the day and, in the controversy between W. & Lee which agitated the camp and Congress, such was his devotion to the former that, late in the year, he invited Gen. Lee to a rencontre, who, after receiving a slight wound, made an explanation equally honorable to himself and satisfactory to his antagonist.

On the invasion of Georgia in '79, Co' L. hastened to Carolina. Here he was conspicuous in preparing for the expected invasion. In order to aid the councils of the State, he was elected a member of their Legisla ture where he used every arg to call out the militia and forward the black levies which he had begun to recruit. On the arrival of Gen. Lincoln, he immedi ately joined him; was present in the storm of Savannah, and such was his chivalry, that, after the retreat was sounded, and the troops had fallen back, he continued on, in the direction of the enemy's fire until C D'Es taing, who was himself wounded, pointed him out to Lincoln, who ordered him to draw off a detachment in order to remove him from the field.

The misfortune of that day menacing the most alarming consequences, Laurens rode express to Philadelphia, in order to urge succours to the Southern Army. Here he received a new mark of confidence; being elected by Congress Secretary to the Minister at Versailles- a situation which he peremptorily declined (though sought for by the most conspicuous names in the country)_ in order to rejoin the army, and was at last induced to accept, on an intimation “that there was no other individual on whom the two parties in congress could unite.” Circumstances having occurred to render his departure on this service unnecessary, he hastened from Philadelphia and arrived in sufficient season to take part in the defence of Charleston, where I presume, he was taken prisoner_ (this fact I have to learn). The most important incident, however, of his life and that having the most immediate relation to the claim before you, is his mission as Envoy to France in Feby. 1781. The magnitude of his services on this occasion are matters of history, but among many inte resting incidents connected with this event there is one which may not be before the public. Vergennes was opposed to any open interference on our behalf at the outset of the quarrel, and always continued adverse to our independence. In this spirit he presented every obstacle in the way of Col. Laurens negotiation,_ Wearied by these delays L. obtained an interview with him, and after a warm expostulation, characteristic of his noble spirit, he broke from him_ prepared a memorial to the king, and, waiting upon him in the succeeding levée, regardless of the etiquette of the court, handed it to Louis in person. This decisive bearing although it excited great astonishment, was followed by the happiest effects. On the succeeding day the ministers contended with each other in their zeal to promote his views, and he returned here in sufficient season to aid us in a most critical posture of our affairs. (The money obtained by Laurens was deposited in the Bank of N. A. and sustained the financial operations of Mr. Morris until the signature of the provisional treaty). Laurens arrived in Boston, in Sept. 1781, and he immediately joined the army and in the storm of the Redout on the night of the 14th Oct, which was the closing scene of my father's service, L. who, with a body of picked men, was detached by him to take the enemy in reverse and intercept their retreat, entered the works among the foremost and made prisoner the commanding officer. As a compliment to his gallantry and in reference to the capture of Charleston, he with the Viscount De Noailles, was appointed a commissioner to settle the terms of the capitulation. (Signed) John C. Hamilton.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

24 Days of La Fayette: December 20th – Louis-Saint-Ange, chevalier Morel de La Colombe

Although it is not any longer December, we are going to finish this series – just a month or two delayed. :-)

Louis-Saint-Ange, chevalier Morel de La Colombe is one of La Fayette’s more prominent aide-de-camps and he was also one of his initial fours aide-de-camps (the other ones being Brice, Virgny and Gimat, all three of them were already covered in posts) and a passenger on La Victoire. Among all of La Fayette’s other aide-de-camps and travel companions, La Colombe had the most interesting motivation. He was not seeking glory, fame or fortune, he was not put at La Fayette’s side by chance or French or American agents. In short, he had no ulterior motives beside being with La Fayette. This is also evident in the agreement between the French adventures and Silas Deane.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 1, December 7, 1776–March 30, 1778, Cornell University Press, 1977, p. 18.

As we can see, La Colombe only ever desired to be made a Lieutenant, a, comparatively speaking, low rank. La Colombe was born in 1755 in the Auvergne, the same region that La Fayette hailed form and his family could easily rival those of La Fayette’s in terms of influence and means in the area. He was the son of Jean-Claude de La Colombe. The two families were closely connected and La Fayette and La Colombe were friends. In fact, La Fayette considered him the worthiest of his companions and called him his “best friend”. Despite his moderate demands, Congress was not very forthcoming with La Colomb’s commission – nor with that of anyone else, as we all know, even La Fayette had to fight for his commission and even more so for his commission to be taken seriously.

La Colombe was most likely in the group that travelled by water to Charleston and from there to Philadelphia. For the first months after his arrival, very little mind was paid to La Colombe’s case from official side. La Fayette wrote on September 25, 1777 to Henry Laurens:

The bearer of my letter [La Colombe] is a genteleman who came with me upon my assurance that he would be employed. He is of a very good birth, and a sensible young man. He wants only a commission of lieutenant, and General Canaouay is desirous of having him in his brigade. As Congress did not comprehend him in sending back the others I hope that he will be received in our service. Will you be so good to speack about it when you') find some occasions?

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 1, December 7, 1776–March 30, 1778, Cornell University Press, 1977, pp. 110-112.

The Marquis continued to petition Laurens on La Colombe’s behalf and he also wrote to George Washington on October 14, 1777:

among the officers who came on board of my ship, this whom Congress did pay the less regard to, is the very same whom I recommended as the most able and respectable man and my best friend—he was coming only for me (…)

“To George Washington from Major General Lafayette, 14 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 11, 19 August 1777 – 25 October 1777, ed. Philander D. Chase and Edward G. Lengel. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001, pp. 505–508.] (02/10/2023)

It was around that time that finally some movement in La Colombe’s case could be observed. On September 10, 1777, Congress recognized his rank as a Lieutenant (and his work he had done for La Fayette since his arrival) by paying him 243 Continental Dollar as his pay as a Lieutenant from December 1, 1776 until September 1, 1777. On November 15, 1777 he was commissioned an aide-de-camp to La Fayette with the rank of Captain. La Fayette himself wrote a note of thanks to Henry Laurens on November 29, 1777:

All the letters I receive from frenchmen are full of theyr gratefulness for your own particular kindness towards them. Will you be so good as to accept my thanks for them and for myself, and to join here my sincere ones on account of the appointement of Mr. de Ia Colombe?

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 1, December 7, 1776–March 30, 1778, Cornell University Press, 1977, pp. 160-161.

The next months passed relatively uneventful and La Colombe dutifully continued his service. There was only one more interesting episode during this time when La Colombe was send to negotiate with the Natives. La Fayette wrote to Charles Lee in June 1778:

Mr. de Fai'lly, de La Colombe See. are now going with Gal. MgKintosh, where theyr presence among the indians is of a great Service, but they’ll come again and we must provide for them or such others as may come from France

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 2, April 10, 1778–March 20, 1780, Cornell University Press, 1978, pp. 62-64.

Shortly before La Fayette returned to France for the first time, La Colombe desired to be made a Major and La Fayette was eager to lend a helping hand. He wrote to the President of Congress on January 9, 1779:

May I beg leave to Reccommend Mr. de La Colombe who desires to sollicit the commission of Major.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 2, April 10, 1778–March 20, 1780, Cornell University Press, 1978, pp. 220-222.

At first, La Colombe’s prospects seemed very good, the Committee for Foreign Applications was in favour of his promotion but he eventually failed to gain the nine votes in the Continental Congress required. Very interesting in this context are two letters between Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, whom, as President of Congress, La Fayette had previously petitioned. Jay wrote on September 18, 1779:

The Board of War are charged with Chevalier de Colombes affair, and will probably report in his favor; for my own Part I have ever been averse to giving Brevets except in very particular Cases; it cheapens us.

“To Alexander Hamilton from John Jay, 18 September 1779,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 2, 1779–1781, ed. Harold C. Syrett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1961, pp. 182–183.] (02/10/2023)

Hamilton replied on September 29, 1779:

I shall not be sorry if Colombe fails in his application. My sentiments correspond with yours on the operation of brevets; but we began wrong and the transition must be gradual.

“From Alexander Hamilton to John Jay, [29 September 1779],” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 2, 1779–1781, ed. Harold C. Syrett. New York: Columbia University Press, 1961, pp. 189–192.] (02/10/2023)

In the meantime, La Fayette had returned to France and believed that several of his aides, La Colombe among them, would follow shortly after. He wrote to the Comte de Vergennes on May 23, 1779:

Any day I expect three Americans and a Frenchman who would be of the greatest use to us, and I enclose their names so that M. de Sartine may send word to all the ports to urge them, upon their arrival, to come and see me at Saintes.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 2, April 10, 1778–March 20, 1780, Cornell University Press, 1978, pp. 268-269.

When the party did not arrive for several more weeks, La Fayette started to assume the worst. He wrote to George Washington on June 12, 1779:

I don't know what is Become of Cle[l]. Nevill and the Cher, de La Colombe. I beg you would make some inquiries for them, and do any thing in your power for theyr speedy exchange in case they have been taken.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 2, April 10, 1778–March 20, 1780, Cornell University Press, 1978, pp. 276-281.

In the end, the matter was not quite that dramatic and as it turned out, La Colombe and the others had never intended to immediately follow La Fayette. La Colombe in fact was transferred to the staff of the Baron de Kalb and served him as an aide-de-camp for some time. He eventually left Boston for France on November 15, 1779 onboard the French Frigate La Sensible, the same ship that also carried John Adams and John Quincy Adams. La Colombe and John Qunicy Adams would indeed meet again later in life. On July 8, 1794, John Quincy Adams wrote to his mother Abigail Admas:

I have likewise seen a Mr: Colomb, an aid to Mr De la Fayette; who went to Europe in 1779 with us on board the Sensible. “tempora mutantur et nos mutamur in illis.” Mr: Colomb and I sat and conversed very sociably together for half an hour before either of us discovered that we had been formerly acquainted, and fellow passengers.

“John Quincy Adams to Abigail Adams, 8 July 1794,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Adams Papers, Adams Family Correspondence, vol. 10, January 1794 – June 1795, ed. Margaret A. Hogan, C. James Taylor, Sara Martin, Hobson Woodward, Sara B. Sikes, Gregg L. Lint, and Sara Georgini. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011, p. 207.] (02/10/2023)

But back to the topic at hand. Washington wrote to La Fayette on September 30, 1779:

You enquire after Monsr. de la Colombe, & Colo. Neville; the first (who has been with Baron de Kalb) left this a few days ago as I have already observed for Phila., in expectation of a passage with Monsr. Gerard.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 2, April 10, 1778–March 20, 1780, Cornell University Press, 1978, pp. 313-319.

De Kalb wrote on October 15, 1779 to John Adams:

The Chevr. de la Colombe having been in Marquess de la Fayette’s family while he Staid in our army, and a Supernumerary aid de Camp to me this Campaign, But his father desiring him to come home, I request the Favour of you to admit as a Passenger into the Same Frigate you are to Sail in.

“To John Adams from Johann Kalb, 15 October 1779,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Adams Papers, Papers of John Adams, vol. 8, March 1779 – February 1780, ed. Gregg L. Lint, Robert J. Taylor, Richard Alan Reyerson, Celeste Walker, and Joanna M. Revelas. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989, pp. 202–203.] (02/10/2023)

While in France, La Colombe transferred back to the French Forces under General Rochambeau. In the spring of 1780 and with the help of La Fayette, La Colombe was made a Captain in the King’s Dragoons. He returned to America in early September of 1780 onboard the Alliance and participated in the battle at Yorktown. After Yorktown, he returned to France with La Fayette where he retired from the King’s Dragoons in 1783.

By March 9, 1784, La Fayette included La Colombe’s name in an enclosed list of “Names of the American officers wearing now in France the badge of the society of the Cincinnati” in a letter to George Washington.

After the onset of the French Revolution, he again entered the military and became the colonel of an infantry regiment in 1791 before he once more took up working as La Fayette’s aide-de-camp in 1792. La Fayette’s wife Adrienne wrote on January 14, 1790:

The Chr de la Colombe who has had the honour of serving under your orders, and whose patriotism and sentiments for Mr De la Fayette have rendered eminent services to our cause as well in his province as in the parisien Army, in which he is Aid-Major, having known that I had the honour of writing to you wishes that I offer to you his best respects.

“To George Washington from the Marquise de Lafayette, 14 January 1790,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 4, 8 September 1789 – 15 January 1790, ed. Dorothy Twohig. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1993, pp. 571–574.] (02/10/2023)

When La Fayette tried to leave France for America during the French Revolution, La Colombe was by his side and arrested along with him. While La Fayette would have to endure imprisonment for several years, La Colombe quickly regained his freedom. William Short wrote to Thomas Jefferson on October 19, 1792:

M. de la Colombe, aide de camp to the Marquis de la fayette, and stopped with him, has made his escape from the citadel of Antwerp—he wrote to me from Rotterdam to know whether he would be safe in this country—I did not suppose he would be if demanded by the Austrian government and gave him that opinion—he proceeded in consequence without delay to England.

“To Thomas Jefferson from William Short, 19 October 1792,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 24, 1 June–31 December 1792, ed. John Catanzariti. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990, pp. 502–504.] (02/10/2023)

I have seen some editors mention that La Colombe was imprisoned with La Fayette in Olmütz but that can hardly be, given the timing of events. There was a considerable back and forth between Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Pinckney (U.S. minister at London) and Edmund Randolph (Secretary of State) about some possible funds for La Colombe and the practicability of him coming to America. He eventually settled in Philadelphia in 1794 where he became a member of the Philadelphia mercantile firm of La Colombe Cadignan & Company, located at 97 South Water Street.

Once safe in America, La Colome started writing letters to garner support and practical aide for La Fayette.

Edmund Randolph wrote to George Washington on May 15, 1794:

If I do not mistake the hints from Mr Lacolombe, these letters are submitted to you, in order to interest you in making, or causing to be made, a demand of M. La Fayette, as a citizen of the United States. I presume, however, that the step, which you have already taken, will be found to be a satisfactory tribute of personal affection, and, altho’ not more than public duty warranted, yet as much, as actual circumstances will permit.

“To George Washington from Edmund Randolph, 15 May 1794,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 16, 1 May–30 September 1794, ed. David R. Hoth and Carol S. Ebel. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2011, pp. 76–77.] (02/10/2023)

Several of the letters mentioned in the excerpt above were in fact addressed to La Colombe. When La Fayette’s son Georges came to America in the company of Felix Frestel, he likely stayed some time with La Colombe in Philadelphia – in any case, the two of them met. On November 21, 1797 La Colombe wrote to Washington, after having stayed at Mount Vernon in October of the same year:

I take the liberty of presenting you with a short abstract of a letter that may afford you a proof that the man for whose wellfare you have allways had the warmest interest in, General De Lafayette has at last obtained his liberty—as is ascertained by an official note from his Imperial Majesty’s minister, M. ⟨Biro⟩ resident at Hambourg, to a friend of mine Mr Masson formerly his aid du Camp.

“Hambourg 19th Septemr—I have the honor to let you know Sir, that I have received at this moment the official note—an order has been sent from Vienna to Olmutz to set at liberty instantly M. De Lafayette & the other Prisoners.” Several other letters that I have received from Hambourg, and from a particular Correspondent at Olmutz leave me no reason of doubt on this subject—I’m also particularly inform’d that the General & the other gentlemen that were in confinement with him were on the road to Dre[s]den and in all probability would arrive there about the 18th Septemr last, and from thence they were to proceed to Hambourg

“To George Washington from Louis La Colombe, 21 November 1797,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Retirement Series, vol. 1, 4 March 1797 – 30 December 1797, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1998, pp. 479–480.] (02/10/2023)

After helping with the travelling arrangements of Georges, he wrote January 5, 1798:

I have had news of all my Esteem’d friends who were confined in the austrian Bastilles. (…) I am happy sir, to have the honor of forwarding to you the enclosed letter from our mutual Friend Genl De Lafayette whose greatest happiness I’m well assured, was to avail himself the pleasure to write you on the first moment of enjoying his liberty—I took the liberty of sending him a Copy of your letter to me of 3d Decr last, It will be pleasing to him as it may afford a renewed proof of the Paternal sentiments you have for him (…)

“To George Washington from Louis La Colombe, 5 January 1798,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Retirement Series, vol. 2, 2 January 1798 – 15 September 1798, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1998, p. 4.] (02/10/2023)

La Colombe died in America around 1800, the exact date is unknown. With the exception of one short trip, he had never returned to France, nor did he ever see La Fayette again.

#24 days of la fayette#la fayette's aide de camps#marquis de lafayette#la fayette#louis-saint-ange chevalier morel de la colombe#la colombe#adrienne de lafayette#adrienne de noailles#alexander hamilton#george washington#georges de lafayette#william short#john adams#john quincy adams#abigail adams#henry laurens#edmund randolph#thomas jefferson#silas deane#comte de vergennes#founders online#american revolution#american history#french history#french revolution#history#1755#1776#1777#1778

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

I want to talk about the following quote that is supposedly from a letter of the 18th of October 1771 from d'Eon to the Duke of Aiguillon:

Since it is required for the welfare of my country and an august personage, I agree to pass for a woman and promise to give no living soul evidence to the contrary. But what I cannot accept is to wear the clothing of the other sex, although for a time I did wear it in my youth in obedience to my king. To resume this disguise permanently, or even temporarily, would be beyond me; the mere idea appals me so much that nothing could overcome my revulsion.

This quote seems to have come Dr. John M. Mitchell's translation of Joseph Boulogne, called Chevalier de Saint-Georges by Emil F. Smidak. Smidak cites Mémoires du Chevalier d'Éon by Frédéric Gaillardet.

Mémoires du Chevalier d'Éon (1836) by Frédéric Gaillardet is a fictionalised novel that was loosely based on d'Eon's life. Gaillardet himself clarifies that much this book is fictional in his later nonfiction book Mémoires sur la Chevalière d'Éon (1866).

In his novel Gaillardet also includes a letter from the Duke of Aiguillon to d'Eon of the 6th of November 1773 in which Aiguillon informs d'Eon that if she wished to return to France she must do so as a woman.

Michel de Decker includes these two letters in his biography on d'Eon. However he points out Gaillardet doesn't include these letters in his 1866 nonfiction book only his 1836 fictional one. "Il faut bien se résoudre à admettre que lorsque Gaillardet ne trouvait pas une pièce du grand puzzle qu'est son roman historique, il la fabriquait!" [We must resolve to admit that when Gaillardet could not find a piece of the great puzzle that is his historical novel, he made it!]*

In fact in Gaillardet's 1866 nonfiction book he writes:

Nous n'avons trouvé, ni dans les papiers de sa famille, ni dans les archives des affaires étrangères, aucune preuve à l'appui de son assertion que Louis XV et le duc d'Aiguillon aient demandé sa métamorphose. Quant à Louis XVI et à M. de Vergennes, ils n'ont demandé, comme on le verra, la reprise de ses habits de femme qu'après la confession inattendue de son prétendu sexe, faite spontanément par d'Éon à Beaumarchais. [We have found, neither in the papers of her family, nor in the archives of foreign affairs, any proof to support her assertion that Louis XV and the Duke of Aiguillon requested her metamorphosis. As for Louis XVI and M. de Vergennes, they only asked, as we will see, for her to wear women's clothes again after the unexpected confession of her alleged sex, made spontaneously by d'Éon to Beaumarchais.]*

So it seems the letters are in fact fictional.

*google translate

#chevalière d'eon#frédéric gaillardet#someone posted this on tumblr witch caught my attention but the post is a few years old#and I didn't want to seem like I was calling them out on a years old post#they seem to have gotten a lot of their info from Gaillardet (perhaps indirectly)

16 notes

·

View notes