#V.S. Pritchett

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

V. S. Pritchett, December 16, 1900 – March 20, 1997.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Horror Needs Humor 🎃🧛♂️👻😱

If laughter allows us to cope with the trauma of being in the world.

When we think of the horror genre, we think not only of unsettling images, but of unsettling sounds. We think of the scores: the screeching strings of Bernard Herrmann’s anxiety-inducing music for Psycho, the intensifying dread of John Williams’s iconic two-note theme for Jaws, the mid-melody modulations that derange John Carpenter’s piano pieces in Halloween.

We think of the screams of the scream queens (and scream kings), from high-pitched whistle-tone shrieks to guttural bellows. We think of the thwap of a smooth axe chop, the crack of breaking bones, the snap of twigs in a dark forest, the creak of footsteps on an old wood floor, and the susurrations of strange winds. We think of the creepy cadences of “A boy’s best friend is his mother,” of “You’ve always been the caretaker,” of “They’re coming to get you, Barbra.”

Yet, unsettling though they may be, none of these are the sounds that disturb us most in a horror film. No, the most off-putting things to hear in horror are neither score, nor scream, nor sound-effect, nor speech; they’re the paroxysms of laughter that erupt from villain or victim. It doesn’t matter which; they’re terrifying either way.

“Our laughter,” according to writer V.S. Pritchett, “is only a note or two short of a scream of fear.” Perhaps this is why humor and horror, which on the surface seem to be representations of opposing human emotions, make natural bedfellows. In fact, with the possible exception of romance, horror is the film genre most willing to rendezvous with comedy. Comic impositions in the genre have been with us since the dawn of cinema. Early forays into horror territory by the Lumière Brothers and Georges Méliès often included humorous elements: dancing skeletons, spectral pranksters, and plenty of scared people’s pratfalls.

As the film medium grew throughout the silent era, horror and comedy continued to further intertwine. By the advent of the sound era, certain aesthetic and thematic genre elements became codified in the Universal Studios horror template—and a little comedy came along for the ride. We laugh almost as much as we shudder when we watch those classic Universal movies: Dracula, Frankenstein, The Mummy, and The Invisible Man.

The success of 1948’s Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein—where Universal poked fun at its menagerie of monsters—opened the door to parodies of both specific horror films and more general horror film conventions, a door through which many movies later marched: The Comedy of Terrors, Young Frankenstein, Attack of the Killer Tomatoes, Student Bodies, The Slumber Party Massacre, Scary Movie, Shaun of the Dead, Cabin in the Woods, etc. Sure, there are sci-fi-comedies and action-comedies and western-comedies, but the horror-comedy, like the rom-com, has almost graduated from a sub-genre to a distinct genre in its own right.

Perhaps the only thing keeping horror-comedy from becoming a full-fledged genre is that it might actually be redundant: the horror genre itself is a genre of both horror and comedy. Few are the horror films that don’t evoke some laughs. Sometimes the laughs are broad and cheap, sometimes they’re dark and distasteful, but yuck needs yucks. Defining a distinction between horror and horror-comedy becomes useless when faced with films like A Nightmare on Elm Street, Scream, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, American Psycho, and Psycho. These are funny films—and they’re all the more terrifying because of it. All dread and no play would make horror a dull genre.

The horror genre uses comedy in two ways. The first is to relieve the tension that the terror winds tight. Here humor is respite and release valve. Levity allows the audience to breathe, to have a bit of fun between the frights. These light moments allow us to see the people in a horror film as human, to connect with them, to empathize with them. When we see some high school kids laughing it up at a party or ribbing one another between classes, we’re reminded of our own friends. This also makes the frights all the more successful because not only has the comedy gotten us to care for these individuals, but it’s lulled us into a false sense of security. Our body relaxes—but not for long.

Though fun is usually associated with positive traits and likable characters, the horror genre also turns this natural order on its head, by making the villains the ones that seem to be having even more fun than our heroes: Freddy Krueger with his slapstick of the abject, Ghostface with his taunting phone calls, the Invisible Man’s silly transparent pranks, Pazuzu’s jouissance in sacrilege, Annie Wilkes’s gleeful fandom, the dinner-table play of all the Sawyers and Leatherface’s jovial chainsaw ballet under the blistering Texas sun.

Even killers who seem less outwardly giddy, like Michael Myers, still manage to have some fun. In the original Halloween, Myers makes time to dress up like a ghost with glasses for one victim and sets up his bodies in house-of-horrors fashion for another. If we find ourselves laughing along with these monsters and murderers, the humor may be working in a second way: ratcheting up the tension rather than releasing it.

The jokes of the Joker—the greatest horror villain to never feature in a true horror film—might make us laugh, but they rarely make us comfortable. In The Dark Knight, which is more of a horror film than most realize, the Joker’s devil-may-care attitude tempts us to see the world from his point of view: “Now I see the funny side. Now I’m always smiling.” But the humor is always tinged with not just disregard for human feelings (a not uncommon thing for “edgy” comedians), but disregard for actual human life. The violence that undergirds the maniacal humor is perhaps best illustrated by the Joker’s Glasgow smile, but it is also perfectly expressed in the “S” he or one of his clown minions have spray-painted on a stolen semi-truck. The message on the side of the truck, which once read “Laughter is the best medicine,” now reads “Slaughter is the best medicine.”

If laughter is indeed the best medicine, if it allows us to cope with the trauma of being in the world, the Joker highlights how it can also become the worst disease. When everything is funny, then seriousness becomes suspect: “Why so serious?” But in a world without seriousness, there is no empathy, no care, no camaraderie, no civilization; there is only the cold, continuous laughter of a sociopath. Of course, the Joker is so scary precisely because we sense there might be some truth to his outlook, even if we see the horrifying consequences of venturing too far down that path.

The Joker is but one of a seemingly infinite rogue’s gallery of laughing villains, the most horrifying wretches of all: Freddy Krueger, who’s constantly howling at his own one-liners; Chucky, the chuckling homicidal doll; Dr. Giggles, whose tittering sounds exactly as you’d expect; Patrick Bateman, with his variety of laughs; and all the Deadites, and the objects they possess, like that wall-mounted deer head that erupts in the most cartoonish cackles.

Maniacal laughs are not unique to horror; they’ve been a staple of a particular baddie archetype since before cinema even existed. And they’ve become such a common cinematic trope that The Muppets was able to have a villain who just repeats the phrase “maniacal laugh” over and over rather than actually laughing maniacally. (A perfect Muppet gag.)

The laughing villains need not be literal clowns, though evil clowns are quite common in horror: there’s Pennywise from It, the clown-shaped aliens in Killer Klowns from Outer Space, Art the Clown from the Terrifier films, Captain Spaulding from Rob Zombie’s Firefly Trilogy, the grinning clown toy in Poltergeist, even Michael Myers commits his first kill dressed as a clown in the original Halloween.

But the laughing villains do act as tricksters and jesters who mock us by holding a mirror up to society. They show us, in the words of the Joker, “how pathetic [our] attempts to control things really are.” They are cracked looking-glasses, in which we see a broken reflection of ourselves. In this act, we are confronted with how incongruous our beliefs, our rituals, and our rules are with the world in which we exist.

These laughing villains in a way reverse that V.S. Pritchett axiom, “Our laughter is only a note or two short of a scream,” to tell us that, in fact, it is our screams which are only a note or two short of a laugh.

In A Nightmare on Elm Street, dreams are called “incredible body hocus-pocus,” but the definition is as apt a description of laughter. Laughs are one of the most mysterious mechanisms of the body. We laugh for all sorts of reasons: we laugh to release tension and discomfort, we laugh to commiserate or empathize, we laugh out of schadenfreude or superiority, we laugh resignedly in the face of our own defeat, we laugh at absurdity and nonsense, we laugh amid confusion, and sometimes we can’t even explain—perhaps don’t even know—why we laugh.

But the one thing all laughs have in common is that they are a response to incongruity. In noticing such incongruities, we tiptoe around the madhouse. Yes, every laugh, from the smallest chuckle to the loudest howl, is a moment of minor madness making itself known. When Norman Bates says in Psycho that “we all go a little mad sometimes,” he’s not wrong. We do—we just call it laughter.

In this way, the laugh is never solely releaser or ratcheter of tension; it is always both. In our minor madnesses, we “see the funny side” of everything—which does, on the one hand, bring us joy—but we also, in the words of another Joker, “dance with the devil in the pale moonlight.” Through the laugh, we tango with the terrifying chaos at the core of existence; we become one with the horror.

This makes us, at least in the moment of our outburst, like the Invisible Man in The Invisible Man, whose experiments with invisibility have turned him “raving mad.” Our laugh, like his, can feel disembodied, like it erupts not from any visible self, but from some invisible navel-cord that links us back all the way to the primordial ooze of the universal incongruities from which we emerged.

But a laugh, even that of the Invisible Man, is always embodied. A laugh is a presence. A laugh implies a personality. There is no objective laughter, even if it arises from universal incongruities. We may not see the Invisible Man’s flesh and bones, but his laugh still originates from the meat of his body. Even if “the whole world” is the Invisible Man’s “hiding place,” he still has to physically be in the site of his laughter’s emanation: “I can stand out there amongst them in the day or night and laugh at them.”

If any horror film adequately expresses the meatiness of laughter, it’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, which is a visual poem of meat, mirth, machine. The horrifying Sawyer family at the center of the massacre, we are told by one of the family members, have “always been in meat.” As much as they are a family of meat though, they are also a family of machines: the chainsaw that Leatherface wields and their property’s red generator with its mechanical rumble.

Bodies are merely machines of meat. Therefore, the question that runs through The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, for which there is no definitive answer, might go something like this: Is the laugh the sound of the meat machine working as it’s supposed to, like the whirring of a generator or a chainsaw, or is it the sound of the meat machine breaking down?

Early in the film, a drunk says, “There’s them that laughs and knows better.” The relationship between laughter and knowledge is never detailed further, but the line haunts the rest of the proceedings. When Sally Hardesty, the film’s final girl, finally escapes from this family of butchers, her screams in the back of the pick-up truck turn to frantic laughter, and it’s hard to tell why she’s laughing, what she knows, if she knows better.

We’re more used to hearing such maniacal laughter from villains not victims. There are filmic forerunners to her crack-up—even going all the way back to one of the original Universal horror movies, The Mummy, in which Ralph Norton, an archeological assistant, laughs himself to death after he reawakens the mummified remains of Imhotep—but these are always somehow even more unsettling than the laughs of the maniacal villains.

They seem even more inexplicable. We want to know why! Why does Sally Hardesty laugh so hysterically in that truck bed? Why does Ralph Norton? What are they thinking? What do they know? Perhaps we understand them more than we know—or else they wouldn’t trouble us so.

Maybe, in the end, we recognize that it doesn’t matter what Sally knows or doesn’t know, what her brain is thinking about or not thinking about, it’s all just another incongruity. When we laugh, the body admits what the brain cannot.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Birthdays 12.16

Beer Birthdays

Troy Paski (1961)

Bryan Selders (1974)

Nicole Erny (1983)

Five Favorite Birthdays

Ludwig van Beethoven; German composer (1770)

Philip K. Dick; writer (1928)

Bill Hicks; comedian (1961)

Wassily Kandinsky; French artist (1866)

Miranda Otto; Australian actor (1967)

Famous Birthdays

Bruce Ames; biochemist (1928)

Jane Austen; English writer (1775)

Shane Black; actor (1961)

Quentin Blake; artist, illustrator (1932)

Steven Bocho; television producer (1943)

Benjamin Bratt; actor (1963)

Catherine of Aragon; consort of Henry VIII (1485)

Arthur C. Clarke; English scientist, writer (1917)

Barbe-Nicole Clicquot; champagne-maker (1777)

Noel Coward; English writer (1899)

Ben Cross; actor (1947)

Robben Ford; rock, blues guitarist (1951)

Billy Gibbons; rock musician (1949)

Jim Glaser; country singer (1937)

Piet Hein; Danish inventor (1905)

Anthony Hicks; rock singer, guitarist (1943)

Murray Kempton; journalist (1917)

Zoltan Kodaly; composer (1882)

Leopold I; Belgian king (1790)

Danielle Lloyd; English model (1983)

Margaret Mead; anthropologist (1901)

William "Refrigerator" Perry; Chicago Bears DL (1962)

V.S. Pritchett; English writer (1900)

Sam Robards; actor (1961)

George Santayana; Spanish philosopher (1863)

John Selden; English jurist (1584)

Shane; porn actor (1969)

JoAnn Stamm; Mom (1937)

Lesley Stahl; journalist (1941)

Liv Ullman; Norwegian actor (1939)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Found in "Five Bushel Farm" by Elizabeth Coatsworth. Published by Macmillan, 1939.

Found in "Problems, Cases and Materials on Evidence" by Eric Green, Charles Nesson and Peter Murray. Published by Aspen Law and Business, 2000.

Found in "The Web of Evil" by Lucille Emerick. Published by Doubleday, 1948.

Found in "Clifford Goes to Hollywood" by Norman Bridwell. Published by Scholastic, 1980.

Found in "The How and Why Wonder Book of Primitive Man" by Donald Barr. Published by Wonder Books, 1961.

Found in "The Iliad of Homer" translated by Richard Lattimore. Published by the University of Chicago Press, 1957.

Found in "Madness and Civilization" by Michel Foucault. Published by Vintage, 1973.

Found in "The White Album" by Joan Didion. Published by Pocket Books, 1980.

Found in "The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club (Part One)" by Charles Dickens. Published by Collier, 1900.

Found in "The Oxford Book of Short Stories" chosen by V.S. Pritchett. Published by the Oxford Press, 1981.

Forgotten Bookmarks found in books (x)

#art#illustration#cat#typography#graphic design#cover art#80's/90's#antique#vintage#60's/70's#40's/50's#20's/30's#00's/10's

1 note

·

View note

Text

📚 "The Ministry of Time" by Kaliane Bradley is a must-read!

The Ministry of Time blends time travel romance, spy thriller, and workplace comedy.

Explores themes of power, love, and historical defiance.

Features a cast of well-developed characters with witty, engaging dialogue.

The protagonist navigates living with a historical figure from the 1840s.

The novel balances humor, suspense, and emotional depth.

Introduction

Credit – amazon.com

The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley is an exhilarating debut novel that combines elements of time travel romance, spy thriller, and workplace comedy. This multifaceted story follows a civil servant in the near future who is assigned to assist and monitor a historical figure brought to the present day.

Summary

In the near future, a civil servant receives an enticing job offer and soon learns she will be working for a newly established government ministry. This ministry gathers historical figures, known as “expats,” to study the feasibility of time travel.

She is assigned to live with and assist Commander Graham Gore, a figure from Sir John Franklin’s 1845 Arctic expedition. As Commander Gore adjusts to modern life, the protagonist grapples with her feelings and the implications of the ministry’s project.

Critical Analysis

Credit – amazon.com

Bradley’s writing is witty and immersive, drawing readers into a unique narrative that defies genre boundaries. The interplay between the protagonist and Commander Gore is both humorous and poignant, with their evolving relationship serving as the story’s emotional core. The novel successfully balances its various elements, providing a smart and gripping read.

Impact

Readers have found The Ministry of Time to be a thought-provoking and entertaining novel. Its exploration of power dynamics and the potential for love to change everything resonates deeply. The book’s mix of humor, suspense, and romance has captivated a wide audience.

Credit – amazon.com

Comparison

Comparable to The Time Traveler’s Wife and A Gentleman in Moscow, The Ministry of Time offers a fresh take on time travel and historical fiction. Its engaging narrative and well-developed characters make it a standout in the genre.

About The Author

Credit – amazon.com

Kaliane Bradley is a writer and editor based in London. Her short stories and essays have appeared in numerous acclaimed publications, including Catapult, Electric Literature, The Tangerine, and Extra Teeth. Her talent has been recognized with prestigious awards such as the 2022 Harper’s Bazaar Short Story Prize and the 2022 V.S. Pritchett Short Story Prize. The Ministry of Time marks her debut as a novelist.

Bradley’s inspiration for The Ministry of Time stems from her deep fascination with historical polar exploration, particularly the 1845 Franklin Expedition and one of its officers, Graham Gore. What began as a literary parlor game for friends evolved into a full-fledged novel. Bradley posed the intriguing question: What would it be like if your favorite polar explorer lived in your house?

The Ministry of Time: A Novel

Kaliane Bradley’s The Ministry of Time is a masterful blend of time travel romance, spy thriller, and social commentary. If you’re looking for a novel that challenges conventions and keeps you hooked from start to finish, this is the book for you.

Pick up your copy at Amazon

Conclusion

The Ministry of Time is a captivating and original novel that explores the complexities of time travel, love, and historical defiance. Kaliane Bradley’s debut is a testament to the power of fiction to challenge and inspire readers.

Credit – amazon.com

Book Review

Let’s Get Lost By Finn Beales

Key Takeaways Showcases breathtaking remote locations through striking photography. Finn Beales’ narrative style blends personal insights with vivid description. Emphasizes the raw, untouched beauty of…

READ MORE

0 notes

Text

Alredered Remembers Sir V.S. Pritchett, prolific British author and literary critic, on his birthday.

"It is exciting and emancipating to believe we are one of nature's latest experiments, but what if the experiment is unsuccessful?"

-V. S. Pritchett

0 notes

Text

https://www.danzigergallery.com/artists/evelyn-hofer

Hofer's studies covered everything from photographic technique to art theory. She didn't just learn composition and the underlying theories of aesthetics, she also learned the chemistry involved in producing prints. Beginning in the early 1960s she became one of the first fine art photographers to adopt the use of color film and the complicated dye transfer printing process as a regular practice. Throughout her long career, Hofer continued to shoot in both color and black and white – determining which was the more apt for the picture at hand.

In the middle 1950s Hofer's career took an important turn when the writer Mary McCarthy asked her to provide the photographs for The Stones of Florence, a literary exploration of the history and culture of that city. Over the next forty years Hofer collaborated with writers including V.S. Pritchett and Jan (James) Morris to produce books on Spain, Dublin, New York City, London, Paris, Switzerland, and Washington, D.C. in which she mixed portraits and land or cityscapes.

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Photo

Quotable – V.S. Pritchett

Find out more about the author here

35 notes

·

View notes

Quote

In all her work from "Cranford" onwards, Mrs. Gaskell is the neat social historian. First of all, she is the historian [who] catches a whole society from aristocracy and the squirearchy down to the professions and trades. "Why," Molly Gibson, the doctor's daughter, asks Lady Harriet [in "Wives and Daughters"], "Why do you speak of my class as if we were a strange kind of animal instead of human beings?" That question Mrs. Gaskell puts to all classes. She never gets speech wrong, from dialect to drawl. So [by the time] she came to social strife in "North and South"- she had the practice of faithful record. The streets and again, the manners of the streets in that northern town are down with the fidelity of a Dutch painting, though never overdone. She observes not only particular looks and phrases, but the general look, the drift of common gossip. She contrasts the brutality of the mill atmosphere with the superstition of Margaret's beloved Hampshire village... She notes how both places go blindly on in the pursuit of their own magic.

The North Goes South: An Essay on ‘North and South’ by V.S. Pritchett

#North and South#Cranford#Wives and Daughters#English literature#Elizabeth gaskell#literature#v.s. pritchett#quotes

105 notes

·

View notes

Photo

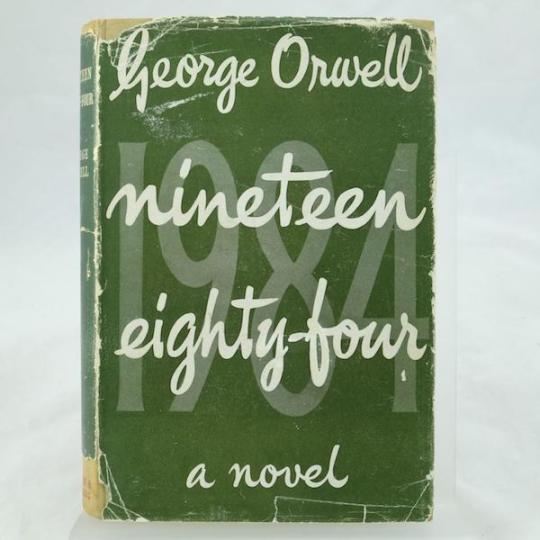

Today in 1949, 1984 was published. Upon its publication, critic V.S. Pritchett wrote, “I do not think I have ever read a novel more frightening and depressing.”

267 notes

·

View notes

Text

V. S. Pritchett, December 16, 1900 – March 20, 1997.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

"...the earth was shrunken like the face of a dying man." #VSPritchett #MarchingSpain

“…the earth was shrunken like the face of a dying man.” #VSPritchett #MarchingSpain

Having done so well reading books from the shelves for #ReadIndies, I thought I should carry on that way for as long as possible! And as Mr. Kaggsy was kind enough to present me with lots of books by V.S. Pritchett for Christmas, it seemed as good a time as ever to sample one. I have short stories and a book on Chekhov, but in the end I plumped for his travelogue “Marching Spain” – which turned…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Birthdays 12.16

Beer Birthdays

Joseph Fallert (1842)

Troy Paski (1961)

Bryan Selders (1974)

Nicole Erny (1983)

Five Favorite Birthdays

Ludwig van Beethoven; German composer (1770)

Philip K. Dick; writer (1928)

Bill Hicks; comedian (1961)

Wassily Kandinsky; French artist (1866)

Miranda Otto; Australian actor (1967)

Famous Birthdays

Bruce Ames; biochemist (1928)

Jane Austen; English writer (1775)

Shane Black; actor (1961)

Quentin Blake; artist, illustrator (1932)

Steven Bocho; television producer (1943)

Benjamin Bratt; actor (1963)

Catherine of Aragon; consort of Henry VIII (1485)

Arthur C. Clarke; English scientist, writer (1917)

Barbe-Nicole Clicquot; champagne-maker (1777)

Noel Coward; English writer (1899)

Ben Cross; actor (1947)

Robben Ford; rock, blues guitarist (1951)

Billy Gibbons; rock musician (1949)

Jim Glaser; country singer (1937)

Piet Hein; Danish inventor (1905)

Anthony Hicks; rock singer, guitarist (1943)

Murray Kempton; journalist (1917)

Zoltan Kodaly; composer (1882)

Leopold I; Belgian king (1790)

Danielle Lloyd; English model (1983)

Margaret Mead; anthropologist (1901)

William "Refrigerator" Perry; Chicago Bears DL (1962)

V.S. Pritchett; English writer (1900)

Sam Robards; actor (1961)

George Santayana; Spanish philosopher (1863)

John Selden; English jurist (1584)

Shane; porn actor (1969)

JoAnn Stamm; Mom (1937)

Lesley Stahl; journalist (1941)

Liv Ullman; Norwegian actor (1939)

0 notes

Text

The summary of the short story The Voice by V.S. Pritchett

The summary of the short story The Voice by V.S. Pritchett

Summary The story is about two characters both of them are clergymen. Lewis is a middle-aged man while Morgan is an old man. Both are Welsh. Morgan buries under the debris, Lewis also fell down in a hole while rescuing him. Morgan can sing. The story starts with an announcement by the rescue team. The members of the rescue team request the people to keep quiet so that they may listen to the voice…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Quote

The sea fog began to lift towards noon. It had been blowing in, thin and loose, for two days, smudging the tops of the trees up the ravine where the house stood.

V.S. Pritchett

3 notes

·

View notes