#Unryū Class

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

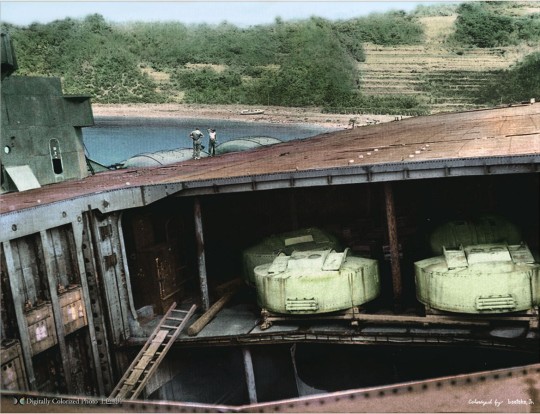

The incomplete Japanese Aircraft Carrier Kasagi (笠置, Mount Kasagi) anchored at Sasebo Naval Base, Japan. She is listening to the starboard.

Date: September 25, 1945

Colorized by Irootoko Jr: link

#Japanese Aircraft Carrier Kasagi#Kasagi#Unryū Class#Unryu Class#Japanese Aircraft Carrier#Aircraft Carrier#Carrier#Warship#Ship#ship construction#Sasebo Naval Base#Japan#Sasebo#Sasebo City#Imperial Japanese Navy#IJN#September#1945#postwar#post war#colorized#colorized photo#my post

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

who do you think the JP anniversary UR is gonna be?

yeah. just take a wild guess.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Japanese Aircraft Carrier Unryū

The lead-ship of her class, Unryu was launched on 25 September 1943 and commissioned on 6 August 1944. For her maiden sea voyage, she was loaded with thirty Yokosuka MXY7 Ōhka kamikaze rocket planes for transport to Manila in the Philippines. Four days after departing Kure, Hiroshima she was sunk by USS Redfish (SS-395) on 17 December 1944. Only 145 men survived to be rescued, with 1,238 officers, crewmen and passengers losing their lives.

More photos here.

#No categories#aircraft carrier#aircraftcarrier#IJNS Unryu#Imperial Japanese Navy#ImperialJapaneseNavy#Second World War#SecondWorldWar#Unryu#World War 2#World War Two#WorldWar2#WorldWartwo

0 notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 5 (17): the Gokushin Arrangement of Three Utensils on the Nagaita [長板]¹.

17) San-shu gokushin nagaita kazari nari [三種極眞長板飾也]².

[The writing (between the ten-ita and ji-ita) reads: kaku no gotoki (如此)³.]

The kaki-ire [書入]⁴:

① [This temae uses] the Gassan-nagabon [月山長盆]⁵.

◦ Among the [various] temae⁶, this one shows the highest degree of appreciation for the utensils⁷.

◦ Certain details dealing with the performance of this temae are ku-den [口傳]⁸.

◦ [One] should be mature in [ones] practice [before attempting this temae]⁹.

② In this case the hoya should be placed so that it overlaps [its kane] by one-third. This is only [done] during the san-shu [gokushin-temae]. The reason is to emphasize the appreciation of the three utensils¹⁰.

③ With respect to this tray, on an occasion when this arrangement [is being utilized] -- and also when two utensils are displayed on the Rai-bon [雷盆]¹¹ -- the tray [should rest] on a fukusa-mono¹².

_________________________

¹Nagaita [長板], in this context, refers to the ji-ita of the daisu. The Gassan-nagabon is arranged on the ji-ita, in the place usually occupied by the mizusashi. ___________ *Nagaita [長板] means “long board.” The implication is that this is the entire board.

In contrast with this idea, the board that is usually called a naga-ita today is referred to as the naka-ita [中板] (“the center of the board”) in the Nampō Roku. Etymologically speaking, this board was made by cutting away the edges of the ten-ita of an old daisu, hence it literally was the middle, or inner, part of the board.

It is entirely possible that these terms (which diverged from conventional usage even in that period) were deliberately chosen to make the contents of the Nampō Roku unintelligible to tea people who had not been initiated into the secrets of its usages. (In the classical documents, and poetry, the dakuten [濁点] that differentiate the sound ga [ガ] from ka [カ] were not used except when absolutely necessary: thus naka-ita and naga-ita might be written in exactly the same way as “ナカイタ.”) This could have been done by Tachibana Jitsuzan, but both the Sen family, and the Tokugawa bakufu, would have had their reasons for wanting to dissuade contemporary tea society from considering the documents that Jitsuzan forged into the Nampō Roku to be anything but antiquated gibberish.

²San-shu gokushin nagaita kazari nari [三種極眞長板飾也].

This means that the Gassan-nagabon, on which the meibutsu temmoku and meibutsu chaire are arranged, is displayed on the ji-ita* of the daisu. The tray is placed there because it is safer -- the tray and the other utensils do not need to lowered to the mat from the ten-ita†.

Because the nagabon is displayed on the ji-ita, a mizusashi cannot be placed there before the temae begins‡ -- and this issue is the subject of the major ku-den associated with this temae (this is the matter that is referred to in the first kaki-ire, as the “temae sabaki” [手前サバキ], “the actions involved in the performance of the temae”). Briefly, since, in the gokushin-temae**, the mizusashi is not needed until the end††, in this case it is not brought out until after everything else has been finished (when the host is going to start removing utensils from the room); and, after lifting it onto the ji-ita, it is used only to add two hishaku of cold water to the kama. ___________ *As I mentioned above, in the Nampō Roku, the ji-ita is frequently referred to as the naga-ita [長板] -- “long board.” However, in the interests of clarity, and to prevent the modern reader from being confused, I will try to use “ji-ita” wherever possible.

The etymologies of the terms nagaita [長板] and naka-ita [中板] are discussed above (in sub-note “*” under footnote 1).

†While it seems that, in the early days (at least in Japan) daisu were often custom-made (and so were able to take into account the host’s stature), this did not mean that every time the temae was performed, it would be in such an ideal setting. Often the height of the daisu would make lowering things to the mat difficult; and the more difficult things are, the easier it is to drop something -- which would be catastrophic, in this case (if not to the object that was mishandled, to the host’s reputation, which would be “ruined forever” -- as the old documents warn).

‡And once the temae has started -- the first step of which being the lowering of the Gassan-nagabon to the mat -- the presence of the nagabon in front of the right half of the daisu would preclude (or make extremely difficult -- which, in this case, is the same thing, since we are dealing with the highest class of the meibutsu utensils -- pieces, in this case, that had been treasured by the Emperor, and then presented to the shōgun) the task of lifting the mizusashi onto the ji-ita.

**To what extent the present temae (and the others in which the tray bearing the dai-temmoku and chaire is displayed on the ji-ita) can be considered a gokushin-temae is subject to debate. Technically, the gokushin-temae follows the formula futatsu-gumi・nanatsu-kazari [二ツ組・七ツ飾] (according to Rikyū, kumi [組] refers to things displayed on the ten-ita, while kazari [飾] defines those arranged on the ji-ita: futatsu-gumi means the dai-temmoku and chaire are grouped together on a tray of some sort, while nanatsu-kazari refers to the classical arrangement of the furo-kama and kaigu on the ji-ita, as per Rikyū’s Shin no dai-temmoku, onaji daisu no koto no densho [眞の臺天目、同臺子の事���傳書]) -- which this temae does not (even though it uses the three utensils that were employed during the san-shu gokushin temae). According to this, even the san-shu gokushin temae [三種極眞手前] is, in truth, a temae performed in the gokushin manner, rather than the actual gokushin-temae.

††Some argue that the mizusashi should be opened after the host drinks the cha-no-ato, following the service of koicha, even during the gokushin-temae. However, in the case of this particular temae, there is no way that the mizusashi could be brought out and lifted onto the ji-ita of the daisu at that time (or, indeed, at any point between the beginning of the temae and this).

Alternately, some suggest that the mizusashi should be brought out at the beginning (as in the previous temae), and placed on the left side of the mat, adjacent to the furo -- and then left in that place throughout the temae (with the mizusashi either lifted onto the ji-ita at the end of the temae, or taken back to the katte as would be the case with any other “hakobi-mizusashi”). These possibilities are considered (albeit with no reference to a meibutsu mizusashi like the seiji unryū) in the Izumi-gusa [和泉草], which collects together many of Katagiri Sadamasa’s teachings. However, it must be remembered that Sekishū was not really concerned with the original forms of the various temae that are described in his writings, but with what he perceived to be the usages unique to Jōō’s period. Yet, his intentions aside, his basic temae remained a variation on Sōtan’s temae, and everything that he discovered about Jōō’s period was interpreted through that temae. Furthermore, the incorporation of what has to be considered a decidedly wabi variation into the gokushin-temae must be viewed with skepticism (at least if we wish to consider things in a historically appropriate manner).

³Kaku no gotoki [如此] means “as usual.” In other words, the artist did not feel like drawing the kama and furo. Nevertheless, these things were arranged, as usual, on the left side of the ji-ita.

⁴The original texts of the three kaki-ire are:

① Gassan-bon nari, temae no naka no dai-ichi no shōgan nari, temae sabaki ku-den, te-juku subeshi [月山盆也、手前ノ中ノ第一ノ賞玩也、手前サバキ口傳、手熟スヘシ].

��� Hoya san-bu-ichi ni kakete-oki koto, kono san-shu no toki bakari nari, hanahada san-shu shōgan no kokoro nari [ホヤ三步一ニカケテ置コト、コノ三種ノ時ハカリ也、甚三種賞玩ノ心也].

③ Kono bon, kono kazari no toki, mata ha Rai-bon ni-shu nado no toki, bon fukusa-mono ni te [此盆、此カサリノ時、又ハ雷盆二種ナトノ時、盆フクサモノニテ].

It seems better to explain the first kaki-ire using several different footnotes -- since this entry consists of four independent statements that were simply linked together using punctuation marks.

The other two kaki-ire are more homogeneous in their contents, and so each of them will be discussed in a single footnote.

⁵Gassan-nagabon [月山長盆].

This was the highest ranked of the six meibutsu trays that were selected by Nōami for Ashikaga Yoshimasa to use when preparing tea with the daisu. The reason for its high ranking is because it allows a set of meibutsu utensils to be aligned with their kane (as mine-suri [峰摺り]), as a matter of course, when distributed equidistantly, or aligned with the decoration that was painted on the tray. In other words, everything comes into its correct place (with respect to kane-wari) quite naturally and easily.

The original Gassan nagabon [月山長盆] featured a night scene, executed in colored lacquer, maki-e, and mother-of-pearl inlay; but, since the original was destroyed during the Ōnin wars, the tray that came down to Jōō was the copy that Haneda Gorō made for Yoshimasa. This version was painted with kagami-nuri [鏡塗] (black lacquer with a mirror-like brilliance), without any other sort of decoration.

The face of this tray (as well as the outer dimensions of its foot) measured 1-shaku 2-sun by 8-sun; while, measured across the rims, it was 1-shaku 3-sun 2-bu by 9-sun 2-bu.

⁶Temae no naka [手前ノ中].

This means “among [all of] the temae” -- in other words, the san-shu gokushin temae is regarded as the highest way to do honor to these special utensils, among all existing temae (including both daisu temae, and those of a more wabi character).

⁷Temae no naka no dai-ichi no shōgan nari [手前ノ中ノ第一ノ賞玩也].

As mentioned in the previous footnote, this temae is the most respectful to the utensils.

Apparently this sentiment was intended to extend to all the variants where the dai-temmoku and chaire are displayed on the ji-ita of the daisu -- not just the version using the Gassan nagabon.

��Temae sabaki ku-den [手前サバキ口傳].

This ku-den refers to the way that the mizusashi* is gotten onto the daisu. Since it cannot be brought out earlier, the entire temae (including the cleaning of the chasen in the kae-chawan at the end of the temae†) is performed without the mizusashi being present‡. After the Gassan-nagabon has been removed from the temae-za, the mizusashi is brought out and lifted onto the ji-ita. Then, without bothering with the kata-kuchi, the lid is opened, and two hishaku of cold water are added to the kama. This is followed by a yu-gaeshi, and the closing of the lid of the kama.

The mizusashi remains on the daisu when the temae is concluded -- and, contrary to the teachings of many of the modern schools, the mizusashi is not refilled at the end of the temae**. ___________ *The “san-shu” [三種], or “three [meibutsu] utensils,” in the expression san-shu gokushin [三種極眞] refers specifically to the Kamakura nasu chaire [鎌倉茄子茶入], the Kazan temmoku [花山天目], and the seiji unryū-mizusashi [青磁雲龍水指]. Thus, for the temae to be an authentic “san-shu” version of the gokushin-temae, the seiji unryū-mizusashi must be included in the temae somehow (yet, because it was forbidden to arrange a ceramic mizusashi on the ji-ita from the first, the only time that the guests could approach the daisu to inspect and appreciate the seiji unryū was after the temae had been concluded).

†After the final chasen-tōshi, and the concluding actions of the temae, the lid of the kama remains open. And it remains open until the mizusashi has been brought out, and two hishaku of cold water are added to the kama. Only then is the lid of the kama, and that of the mizusashi, closed.

‡In Book Six there is a wabi-temae where a kuguri-bon [潜り盆] -- a tray that crosses more than one kane -- is displayed by itself next to the mukō-ro, and a mizusashi is not used. That temae was derived from this one.

There are also very tiny mizusashi that were made for this kind of usage (these pieces often resemble a kashi-bachi with a lacquered lid -- and are sometimes assumed to be kashi-bachi by modern chajin). They are brought out at the end of the ro-temae, and used to add two hishaku of cold water to the kama. This -- and the fact that the black lacquered kata-kuchi is used as the mizutsugi during the ro season -- is why it is said that the ro-temae is derived directly from that of the daisu.

**According to Rikyū’s densho, water is added to the mizusashi after it has been carried out to the utensil mat (so that it will be full when the host begins his temae). At the end -- and this is especially true with respect to the daisu -- there is no reason to refill it, since tea will not be served again afterward.

In the san-shu gokushin temae, the guests inspect the seiji unryū-mizusashi only at the end of the temae because (irrespective of the format) this mizusashi is never present on the daisu when they enter the room at the beginning of the goza. Only bronze mizusashi were traditionally placed out when the daisu was being set up.

⁹Te-juku subeshi [手熟スヘシ].

As was explained in the previous post, te-juku [手熟] literally means that “(ones) hands have ripened.” Te-juku subeshi means that the host's hands (in essence, his abilities and learned dexterity) should be mature (before he attempts to perform this temae).

¹⁰Hoya san-bu-ichi ni kakete-oki koto, kono san-shu no toki bakari nari, hanahada san-shu shōgan no kokoro nari [ホヤ三步一ニカケテ置コト、コノ三種ノ時ハカリ也、甚三種賞玩ノ心也].

“The hoya is placed so that it overlaps [the kane] by one-third. This is done only on an occasion when the san-shu [are being used]. This is intended to show greatest respect* for the san-shu.” ___________ *Because the ten-ita is usually considered the more honored place vis-à-vis the ji-ita, placing the hoya on the ten-ita, but oriented so that it overlaps its kane by only one-third, is like treating it as an ordinary utensil. Thus, this gesture shows great deference to the meibutsu pieces that have, most extraordinarily, been arranged on the ji-ita.

¹¹Rai-bon [雷盆].

This tray is more fully named the Chō-shō rai-bon [趙昌雷盆], Chō Shō being the Japanese reading of the name Zhào Chāng, a celebrated Chinese artist of the Song period, who was supposedly responsible for its painted decoration*.

The tray had a design of grassy flowers, in maki-e (with mother-of-pearl highlights) on the face. The painting was attributed to Zhào Chāng by the dōbō-shū (perhaps on account of a seal or signature on the underside).

The designation “rai-bon” [雷盆]† actually is a classical name for a suri-bachi [擂鉢], a bowl with incised ridges used to grind things like sesame seeds into a paste. It was applied to this tray because the edge of the tray was scalloped, with the inner corners giving a fanciful impression of the incised ridges of a suri-bachi.

This tray was 1-shaku 1-sun in diameter, and so could be used for gokushin arrangements‡. ___________ *From Wikipedia: Zhào Chāng [趙昌; 959年 ~ 1016] “was a Chinese painter during the Song dynasty. He was a disciple of flower-and-bird painter Teng Chang-you (滕昌祐). He also used the methods of the Southern Tang painter Xu Chong-si.”

This is a detail taken from of one of Zhao Chang’s paintings, also from Wikipedia. Presumably the flowers painted on the tray were rendered in a similar manner (albeit as a circular, rather than linear, composition).

†Rai-bon [雷盆] means “thunder tray.” Perhaps originally a corruption or mistaken rendering of the kanji rai [擂] (the first character in suri-bachi [擂鉢]: “rai” is its on [音] pronunciation), some scholars suggest that this name was used because grinding things in a large suri-bachi makes a thunder-like sound.

‡Albeit with the spacing between the utensils and the rim reduced to 1-sun 5-bu, rather than 2-sun, as on the Gassan-bon). Because of this, the Rai-bon was considered inferior to the Gassan-bon, and the arrangements executed with it “not quite” as indicative of the highest level of appreciation.

In the next post, we will look at another case, where the dai-temmoku and chaire are displayed on the naka maru-bon [中丸盆]. In that case, while the separation between the utensils, and between them and the rim of the tray, is 2-sun in every case, the fact that the rim of the tray had a raised band that increased its diameter to 1-shaku 2-sun 3-bu meant that it, too, was not considered to be of the highest rank.

¹²Kono bon, kono kazari no toki, mata ha Rai-bon ni-shu nado no toki, bon fukusa-mono ni te [此盆、此カサリノ時、又ハ雷盆二種ナトノ時、盆フクサモノニテ].

When the Gassan-nagabon, the naka maru-bon, or the Chō-shō rai-bon are displayed on the ji-ita of the daisu, the ji-ita should first be covered with a piece of cloth* -- for protection.

Displaying these trays on the ji-ita was much safer (for the utensils that were arranged on the trays), because the tray would not have to be lowered from the ten-ita at the beginning of the temae.

Nothing is said (in any of the manuscripts) regarding how the Gassan-nagabon is to be oriented on the ji-ita. Indeed, contrary to what one would expect, the kane are not even marked on the original sketch -- and, considering that this temae is regarded as being the most deferential toward the utensils that are being used, one can only wonder why this is so, since the absence of any sort of commentary on such an important temae is a real hardship for the scholar and reader alike†.

Shibayama Fugen speculates‡ that the dai-temmoku and chaire are placed on the yin-kane, while the chashaku rests on the yang-kane that is found in between them. This is impossible, however, because, if the two principal utensils were oriented in that way, the left rim of the Gassan-nagabon would touch the furo, which is -- of course -- not permissible (if, for no other reason, that the possibility raising the kan at the beginning of the temae would endanger the temmoku).

Tanaka Senshō (ever the businessman), only bothers to say that this temae is demonstrated every year during the Dai Nihon Sadō Gakkai’s ka-ki kōshu kai [夏期講習会]** (though one would have had to study with his school for many, many years before receiving an invitation to participate in that event: the purpose was to produce Dai Nihon Sadō Gakkai teachers with close ties to the iemoto, not assuage the curiosity of Nampō Roku scholars). Furthermore, we must remember that this is the Dai Nihon Sadō Gakkai’s temae (which was created as an analog of Urasenke’s high daisu-temae -- which, in turn, were fabricated in the nineteenth century based on Katagiri Sadamasa’s speculations), rather than an approximation of the original that would have dated from the fifteenth or sixteenth century.

The above sketch makes clear the details of the arrangement, and shows the relationship between the utensils and the various kane (the purple edge around the nagabon is supposed to represent the fukusa-mono†† that is mentioned in this kaki-ire).

It will be noticed that the chaire is immediately to the left of the first kane (and so, because it is 2-sun 2-bu in diameter, it is wholly situated between the yang and yin kane, while coming into contact with neither), while the temmoku touches both the second yang kane and the third yin kane (and so is, likewise, associated with neither of them -- since the foot of the temmoku has no association with either kane). The chashaku, likewise, is located between the yin and yang kane. The tray, however, is a kuguri-bon [潜り盆] (since it crosses more than one kane), and so the Gassan-bon (and everything on it) counts as han [半] (yang), as does the furo‡‡.

In the case of this kind of temae, the chashaku would almost always*** be enclosed in a shifuku. ___________ *Irrespective of its actual dimensions (which were probably based on the native width of the cloth that was being used to make it, rather than following the 8-sun by 8-sun 2-bu format of the “temae-fukusa” preferred by Furuta Sōshitsu -- notwithstanding the fact that Tanaka argues that this is precisely what is used), this piece of donsu was usually sewn like an over-sized fukusa -- the three open edges being closed with internal hems. This is why it is referred to as a fukusa-mono [フクサモノ = 袱紗物] in the kaki-ire.

Once the tray had been removed, the fukusa-mono was folded up and put into the host’s futokoro (or possibly his right sleeve).

†There are two possibilities: secrecy, or ignorance. We must remember that apparently Jōō never attempted to perform any of the temae that utilize the Gassan-nagabon -- perhaps because the correspondence to the kane in this variation nonplussed him (or because he was unable to add the original utensils, upon which this temae was based, to his collection -- the original nagabon, dai-temmoku, and chaire were all destroyed during the Ōnin wars).

‡Unfortunately, we can call it nothing more than speculation, since it precludes an actual understanding of the dimensions of the Gassan-nagabon vis-à-vis the space available on the ji-ita of the daisu between the furo and the hashira on the right. Shibayama seems to be playing mind games, rather than attempting to manipulate the objects on the ji-ita of an actual daisu.

**The ka-ki kōshu kai [夏期講習会] is one of two special training sessions (with access usually restricted to high-ranking teachers) during July and August (in most schools, it generally ends just before the O-bon festival on August 16) -- the other, the tō-ki kōshu kai [冬期講習会], is held during the winter (usually beginning after January 15 -- the end of the New Year’s holiday season -- and sometime in February). The tea world borrowed this idea from the Zen temples, where a special intensive meditation session (usually lasting 90 days) was held twice a year, in the summer, and in the winter (during the months when intensive farm work in the temple’s agricultural fields was not necessary).

††Tanaka Senshō interprets the word fukusa-mono to mean the modern day temae-fukusa, and he states that two fukusa are placed side-by-side on the ji-ita, with the nagabon placed on top of them. The modern temae-fukusa, however, did not exist during Jōō’s lifetime (it was created by Rikyū, not as a fukusa, but as a miniature furoshiki in which a lacquered container of matcha was tied when it would be sent to someone as a gift in a sa-tsū-bako; Furuta Sōshitsu is the first one to have actually used it as a temae-fukusa, and this was, on the first attempt, out of duress -- he received a sa-tsū-bako from Rikyū while hosting a gathering and decided to share the tea with his guests, but, lacking a new fukusa, he decided to use the little furoshiki as the temae-fukusa when serving the gift tea: only later did he start to have his temae-fukusa deliberately made like this, rather than out of Chinese donsu).

Originally, fukusa were made out of Chinese donsu [緞子], and their size was determined by the native width of the cloth: a piece twice as long as the native width was cut off of the roll, folded in half, and stitched with internal hems around the three open sides. Most Chinese cloth was around 1-shaku wide (Japanese cloth, on the other hand, was usually 9-sun wide, and it was this that determined the dimensions of Rikyū’s little furoshiki that became the prototype of the modern temae-fukusa).

In this instance, a special fukusa-mono would naturally have been made for the occasion -- probably by cutting a length of donsu a little over two and a half times as long as it was wide, and then sewing this into a rectangle by means of internal hems on the three open sides. This piece of donsu was then spread on the ji-ita, and the Gassan-nagabon was placed on top of it. The fukusa-mono was probably just slightly larger than the foot of the tray, and so may not have been obvious to the guests (I made it obvious in my sketch because otherwise nobody would have known it was there).

At the beginning of the temae, after the nagabon had been moved onto the mat in front of the daisu, the fukusa-mono would have been folded up and inserted into the futokoro of the host’s kimono (or, possibly, into his sleeve).

In point of fact, though, fukusa were always specially made for each chakai since, unlike now, it was a strict rule that the fukusa could be used only once: people like Rikyū would have always had a ready supply available to them (probably produced by a special seamstress, employed for just this purpose); but most chajin only had a fukusa made when they would be hosting a gathering (so that the cloth would be clean and dust-free on that occasion).

‡‡The furo is han, and the Gassan-nagabon is han [半]. On the ten-ita, the hoya is han (because it overlaps the central kane by one-third), while the hishaku is associated with neither the left-most yin, nor the left-most yang kane, and so is considered to be neither (it is, therefore, ignored, for the purposes of kane-wari). Thus, the daisu is han [半], for the purpose of kane-wari.

***The host would probably not make the chashaku himself unless that could not be avoided (a chashaku made by the host would not be enclosed in a shifuku, even if the host was considered to be a meijin by his contemporaries).

Nevertheless, given the high quality of the other utensils, if the chashaku were made by someone else, then it would be incumbent upon the host to try to get one that had been made by someone of high standing (at least, in the eyes of the world of chanoyu) -- in other words, a meijin [名人].

——————————————–———-—————————————————

◎ Analysis of the Arrangement.

The orientation of the Gassan-nagabon (and the utensils placed on it) on the ji-ita of the daisu was described above (under footnote 12). The complete arrangement is shown below.

The actual temae is essentially the same as the previous temae -- though, in this case, after the chashaku has been placed on the kae-chawan, the dai-temmoku is moved directly from the nagabon to the mat (in front of the furo); and then the chaire is centered on the tray, and it is lifted down to the mat (and oriented on the mat as was explained during the previous temae). Then the hoya would be lowered to the ji-ita (with the lid flipped over in the process), and then the hishaku would be rested upon it*. The service of tea would proceed as always.

At the end of the temae, the host arranges the dai-temmoku, chaire, and chashaku on the Gassan-nagabon, and places it on the mat next to the utensil mat†, and the guests come forward from their seats and inspect the utensils.

While this haiken is taking place, the host cleans the chasen in the kae-chawan (using hot water, on this occasion, since there is no cold water available at this time). When he is finished, he dries the kae-chawan by draping the chakin over the side, and rotating the bowl through four half-turns‡, and then places the chakin and chasen into the kae-chawan, and lifts it to the katte-side of the mat. He leaves the lid of the kama on the hoya, and the hishaku resting on the mouth of the kama.

When the guests are finished with their haiken, the host takes back the Gassan-nagabon and places it on the mat in front of the daisu (in the center of the mat). After lifting the dai-temmoku off and placing it on the mat in front of the furo, the host ties the chaire into its shifuku (tying the himo with a locking knot), places the chaire in the middle of the tray, and then lifts the Gassan-nagabon up to the ten-ita of the daisu**. Then, after moving the dai-temmoku in front of his knees, the host also ties it back into its shifuku (using a style of knot that is complementary to that used in the beginning), and then lifts the dai-temmoku up onto the ten-ita, to the left of the tray. Moving the chaire toward the right (so it is 2-sun from the rim), the host lifts the dai-temmoku onto the tray, and then moves the tray backwards and to the right, so that the dai-temmoku is located in the middle of the ten-ita††.

The host removes the koboshi, and then the kae-chawan, and returns to the utensil mat with the seiji unryū-mizusashi.

The host lifts the mizusashi onto the ji-ita in the same manner as was described in the previous post (though this time he does not bring out a kata-kuchi to add more water to the mizusashi). Then he opens the lid, and dips two hishaku of cold water into the kama, followed by a yu-gaeshi. Then he closes the lid of the kama. The hishaku is placed on the left side of the ten-ita, and the lid of the hoya is flipped over, and it is set down on the ji-ita, between the furo and the mizusashi, forward from the midline of the ji-ita. Finally, the Gassan-nagabon is lifted off of the ten-ita and placed on the shelf underneath the chigai-dana. ___________ *This will be explained in detail in the text accompanying the entry that deals with the Rai-bon [雷盆].

†The tray is turned so that the side that touched the front of the daisu is parallel to the heri of the utensil mat.

When the guests approach the Gassan-nagabon, they should generally look at the utensils without touching them. Only an extremely experienced chajin should presume to pick them up -- and then, care must be taken to return them to the same place afterward.

If, however, the shōkyaku is someone of extremely high rank (and so seated on the jōdan [上段] of the room), and he expresses a desire to inspect the utensils (the original temmoku-chawan and nasu-chaire that were used during this temae came from Emperor Go-komatsu’s personal collection of treasures, thus even an emperor would probably experience a desire to look at them carefully), then the nagabon will be conveyed into his presence by his attendants, and returned by them to the mat adjoining the utensil mat afterward.

‡This is the way most schools teach their students to dry the chawan on every occasion today -- though originally things were done this way only when drying the kae-chawan. (The confusion came about when the bowls originally used as kae-chawan came to be used as omo-chawan during the first decades of the sixteenth century, and this practice was perpetuated by some of the machi-shū: it became the usual way to do things under Sōtan).

**The extreme deference accorded the utensils is focused on the beginning of the temae. Once the service of tea has been concluded, they should be handled as usual (their usual treatment was described in the previous temae).

††This is an acknowledgement of the high rank of the shōkyaku.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Aircraft Carrier Amagi: World War II

Aircraft Carrier Amagi: World War II

Amagi (天城) was a Unryū-class aircraft carrier built for the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War II.

Named after Mount Amagi, and completed late in the war, she never embarked on her complement of aircraft and spent the war in Japanese waters.

The Aircraft Carrier Amagi capsized in July 1945 after being hit multiple times during airstrikes by American carrier aircraft while moored at Kure…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

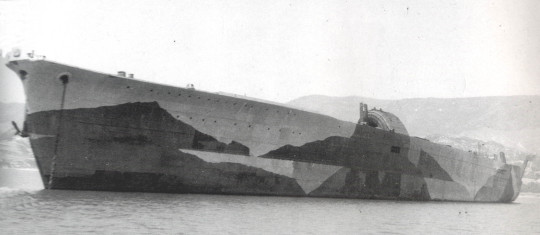

The capsized Japanese Aircraft Carrier Amagi (天城, Mount Amagi) at the Kure Naval Arsenal, Japan.

Date: October 8, 1945

NNAM.1996.488.037.007

#Japanese Aircraft Carrier Amagi#Amagi#Unryū Class#Unryu Class#Japanese Aircraft Carrier#Aircraft Carrier#Carrier#Warship#Ship#Capsized#Kure Naval Arsenal#Japan#Kure#October#1945#postwar#post war#Imperial Japanese Navy#IJN#battle damage#sink#my post

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Japanese Aircraft Carrier Kasagi (笠置) in Sasebo Harbor, Japan, on October 19, 1945. "This ship was not completed, but appears to have received a camouflage scheme. A number of Japanese wooden working craft are in the foreground."

U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command: SC 218457

#Japanese Aircraft Carrier Kasagi#Kasagi#Unryū Class#Unryu Class#Aircraft Carrier#Japanese Aircraft Carrier#October#1945#post war#Sasebo Harbor#Japan#Imperial Japanese Navy#IJN#my post

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The incomplete Imperial Japanese Navy Aircraft Carrier Kasagi (笠置, Mount Kasagi) anchored at Sasebo Naval Base, Japan.

Date: November 2, 1945.

source, source

Colorized by Irootoko Jr: link

#Imperial Japanese Navy Aircraft Carrier Kasagi#Japanese Aircraft Carrier Kasagi#Kasagi#Unryū Class#Unryu Class#Imperial Japanese Navy Aircraft Carrier#Japanese Aircraft Carrier#Aircraft Carrier#Carrier#Warship#Ship#Sasebo#Sasebo Naval Base#Sasebo Base#Japan#Nippon#Imperial Japanese Navy#IJN#postwar#post war#November#1945#colorized photo#colorized#my post

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Japanese Aircraft Carrier Amagi (天城, Mount Amagi) capsized after U.S. navy air raid, Kure, Japan.

Photographed, most likely, in August 1946

source

#Japanese Aircraft Carrier Amagi#Amagi#Unryū Class#Unryu Class#Japanese Aircraft Carrier#Aircraft Carrier#Carrier#Warship#Ship#sunk#wreck#Imperial Japanese Navy#IJN#Kure#Japan#August#1945#postwar#post war#color photo#my post

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Japanese Aircraft Carrier Ibuki (伊吹, Mount Ibuki), under dismantling operation at Sasebo Factory, Japan. On the right, workers are dismantling the Aircraft Carrier Kasagi (笠置, Mount Kasagi).

Photographed on October 22, 1946

source

Colorized by Irootoko Jr: link

#Japanese Aircraft Carrier Kasagi#Kasagi#Unryū Class#Japanese Aircraft Carrier Ibuki#Ibuki#Light Carrier#Japanese Aircraft Carrier#Aircraft Carrier#Warship#Ship#Imperial Japanese Navy#IJN#Sasebo Naval Base#Sasebo#Japan#Scrapping#October#1946#postwar#post war#colorized#colorized photo#my post

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

The incomplete Japanese Aircraft Carrier Ikoma (生駒, Mount Ikoma) anchored near Shodoshima, Japan. She was 60% complete when construction stopped on November 9, 1944. Her hulk was scrapped between July 4, 1946 and March 10, 1947.

Date: May 23, 1946

Collection of Kure Maritime History Science Museum: link

#Japanese Aircraft Carrier Ikoma#Ikoma#Ikoma Class#Unryū Class#Unryu Class#Japanese Aircraft Carrier#Aircraft Carrier#Carrier#Warship#Ship#ship construction#Imperial Japanese Navy#IJN#Shodoshima#Shōdo Island#Japan#Nippon#postwar#post war#May#1946#cancelled#my post

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Japanese Aircraft Carrier Katsuragi (葛城, Mount Katsuragi) at Kure, Japan.

Note: damage to the flight deck received in air attacks in July 1945.

Date: October 1945

U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command: 80-G-351362

#Japanese Aircraft Carrier Katsuragi#Katsuragi#Unryū Class#Unryu Class#Japanese Aircraft Carrier#Aircraft Carrier#Carrier#Warship#Ship#Imperial Japanese Navy#IJN#Kure#Japan#battle damage#postwar#post war#October#1945#colorized#colorized photo#my post

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Three Japanese aircraft carriers and a submarine in Kure Bay, during strikes by U.S. Navy carrier planes. Carrier at the extreme right is Kaiyō (海鷹, Sea Hawk). Those in the center top (barely visible) and at the bottom are probably Amagi (天城) and Katsuragi (葛城). The submarine is underway in the upper left."

Photographed from a USS HORNET (CV-12) plane on March 19, 1945.

U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command: 80-G-309660

#Japanese Aircraft Carrier Kaiyō#Kaiyo#Japanese Aircraft Carrier Amagi#Amagi#Japanese Aircraft Carrier Katsuragi#Katsuragi#Unryū Class#Japanese Aircraft Carrier#Aircraft Carrier#Warship#Ship#Imperial Japanese Navy#IJN#Submarine#USS HORNET (CV-12)#USS HORNET#Essex Class#United States Navy#U.S. Navy#US Navy#Kure#Hiroshima#Japan#Nippon#World War II#World War 2#WWII#WW2#March#1945

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 3 (18.7): Arrangement of the Shukō-chawan [珠光茶碗], and a Maru-bon Taikai [丸盆大海], on the Fukuro-dana.

18.7) Arrangement of the Shukō-chawan [珠光茶碗]; and of a taikai [大海] chaire arranged on a round tray.

[The writing reads: (above the upper sketch, from right to left) Shukō-chawan (珠光茶碗)¹, nakatsugi natsume mo (中次・ナツメモ)²; (to the right of the upper sketch) mizusashi no ue chakin ・ chasen (水指ノ上 茶巾・茶筅)³; (to the left of the upper sketch) chashaku (茶杓)⁴; (above the lower sketch) maru-bon⁵ taikai⁶ (丸盆大海).]

_________________________

¹Shukō-chawan [珠光茶碗].

While the original bowl that belonged to Shukō was destroyed in the summer of 1582, other, similar, bowls survive into the present.

There were actually a number of virtually identical bowls of this type*, each of which bore the name of the chajin who owned it†. The only discernible difference between them is the number of marks from the hera [篦] (see sub-note “*”, below) that are found on the outside of the bowls, and some variation in color (which ranges from a greenish-ocher to a stronger military green -- the slightly pinkish-gray tone seen in the interior of this bowl appears to be what Sōji referred to as hishira-iro [ヒシラ色]): according to the Yamanoue Sōji Ki [山上宗二記], the chawan of this sort that belonged to Shukō had 27 of these marks. While Shukō's chawan was destroyed (in the fire that consumed the Honnō-ji in Kyōto‡, in 1582), several others have survived down to the present** -- while others have since been imported from China (where they are occasionally recovered from the ruins of the storerooms at old kiln sites). The photos, above and below, show one of these other bowls (the shifuku is tied in what is called the tsune-no-tonbo musubi [常の蜻蛉結び] -- the “ordinary” dragonfly knot -- in the Nampō Roku: this is how the bowl would have been displayed on the ten-ita of the fukuro-dana)††.

These bowls were all decorated on their inner faces with a cloud-like design (using a sort of cutting tool that resembles a Rösle pastry wheel, which scores lines of small dots) -- since the designs differed slightly from bowl to bowl, the potters could ask a higher price by saying they were handmade. The circular depression in the bottom of the bowl insured that they would stack securely‡‡ (the staff of roadside food stalls generally took their pots and serving bowls home with them at the end of the day, to prevent theft or breakage).

The original Shukō-chawan is said to have developed a small crack at the rim early on, and this worsened while it was in Jōō’s keeping (Jōō seems to have been the person who was responsible for having the bowl repaired with same-colored lacquer). This probably accounts for the way it is arranged on the fukuro-dana, as well as its special usage***. After Rikyū was forced to sell his collection of utensils (apparently to Jōō), Jōō presented him with this chawan (as a sort of consolation gift), since its imperfect state -- as well as its history -- were sympathetically appropriate to Rikyū’s now-diminished circumstances. __________ *These bowls were shaped using a mold. Which, at that time (these bowls continued to be made, in Southern China, from the Sung to the Yuan periods), meant a wooden form that created the inside of the bowl (it was important that the interiors be identical in size, since they were used for serving noodles in road-side food stalls -- and if some of the bowls were of a different size, this could create serious problems between the staff and the frequently low-class customers who ate at these establishments). A uniform slab of leather-soft clay was placed over the mold and beaten into shape with a hera [篦] (which is a sort of spatula with the blade divided into elongated teeth like a comb, which makes it somewhat flexible: these marks are clearly visible in the photo on the lower right) while the mold was being turned slowly. Then the foot was added, the arabesque-like cloud motif was incised on the interior, and the mouth was trimmed. After drying, the bowls were glazed and fired.

†All of those who have been identified seem to have emigrated from Korea to Japan around the same time as Shukō, and they appear to have brought these bowls along with them. Since these bowls were actually made for serving noodles in roadside food stalls in China, they most likely were sold in stacks of 10 or so. It would seem that someone (perhaps a monk) brought back a stack or two of these bowls when he returned from a visit to China, and handed them out to the people who had given him money to support his pilgrimage (the cash that was then given as a thank-present would help him reestablish himself back in Korea).

‡Nobunaga was serving tea to his page-lover Mori Ranmaru [森蘭丸; 1565 ~ 1582] when Akechi Mitsuhide [明智光秀; 1528 ~ 1582] attacked the Honnō-ji, in Teramachi, Kyōto. After committing seppuku (to prevent his being captured alive) -- Ranmaru acted as his second -- Ranmaru set fire to the shoin by scattering the charcoal from the furo around the room (this was to prevent the dishonor of Nobunaga's head being collected and paraded by Mitsuhide). After which Mori Ranmaru also committed suicide (apparently unassisted).

Nobunaga was performing the naga-ita temae (interesting enough, the same temae that Yoshimasa had performed the last time he did chanoyu -- though he died of old age). The mizusashi (the seiji unryū-mizusashi [青磁雲龍水指]), chawan (the Shukō-chawan [珠光茶碗]), and kiri-kake kama were destroyed, while the old Temmyō kimen-buro [古天明鬼面風爐] (this was the furo that had been used by Ashikaga Yoshimasa during the period of his brief second retirement), and the two tea containers (the karamono-bunrin chaire now known as the Honnōji-bunrin [本能寺文琳], for koicha; and the old Seto chaire that is usually referred to as the Enjō-bō katatsuki [圓乗坊肩衝] today -- because it was rescued from the ruins of the temple by the monk Enjō-bō Sōen [圓乗坊宗圓; his dates of birth and death are unknown] -- for usucha), while damaged, were salvaged (and have managed to survive down to the present day -- though the furo was damaged further in the Keichō-Fushimi earthquake of 1596).

**They seem to have mostly lost their original names, and are (collectively) referred to as Shukō-seiji chawan [珠光青磁]. Shukō-seiji being the name that the Japanese gave to the low-quality green-glazed ware that resembled his chawan. (While this bowl is used as a chawan today, Shukō would have used it as the kae-chawan for his temmoku.)

††Like Shukō’s chawan, the bowl shown in the photo was also cracked and then repaired with (same-colored) lacquer. The silver fukurin was added in recent years, to help protect the bowl from further damage (lacquer repairs tend to become brittle as the centuries pass).

‡‡While this circular depression is called a cha-damari [茶溜り] today (meaning the place where the tea rests), it seems that the original name was chawan-damari [茶碗溜り] (the place where a chawan rests). In fact, the foot of one bowl fits into the depression like the foot of a cup into its saucer (and these large chawan seem to have been used as a sort of saucer for the temmoku before the introduction of Chinese lacquered temmoku-dai).

***The Shukō-chawan is placed, as a mine-suri [峰摺り], on the ten-ita of the fukuro-dana. This is the most exalted arrangement possible. However, when used with the daisu, it was displayed in a clearly inferior manner. This suggests that, in Jōō’s opinion, the Shukō-chawan was the preeminent chawan for wabi-no-chanoyu (and his gifting of this bowl to Rikyū, after Rikyū was forced to give up all of his fine utensils, can be understood as a recommendation that Rikyū henceforth give up any pretenses to gokushin-no-chanoyu, and devote himself exclusively to wabi tea for the rest of his life).

The special usage associated with this bowl (which was probably the “ku-den” to which the red spot is referring to) required the host to open the mizusashi at the beginning of the temae (before opening the kama). Then two hishaku of cold water were added to the kama (to cool it), and half of a third hishaku-full of cold water was poured into the chawan (while the rest was also added to the kama). Then a quarter hishaku of hot water was poured into the cold water in the chawan, and the bowl was picked up and rotated very slowly, to warm it gently. Next, without discarding the water that was already in the bowl, the Shukō-chawan was placed down on the mat again, and (following a yu-gaeshi) a half hishaku of hot water was added; the bowl was rotated three times again, and this time the water was discarded. Now, sufficiently warmed (so that the shock of adding hot water would not cause the crack to worsen -- as it apparently had before this procedure was created for it), a half-hishaku of hot water was added to the bowl, and the lid of the kama, and then the mizusashi, were closed, and the host performed the chasen-tōshi.

The remainder of the temae was as usual, though hot water was used for the final chasen-tōshi, rather than cold water.

After the bowl came into his possession, Rikyū used it resting on a large, red-lacquered, sakazuki [盃] (shaped like a flat dish with a raised rim, and low foot, measuring 6-sun in diameter), as a mark of respect. It is said that the first time he did so was when Jōō visited his residence for the first time.

²Nakatsugi ・ natsume mo [中次 ・ ナツメモ].

While the shin-nakatsugi was probably preferred (since it had been created by Shukō), a natsume could be used as well. The shin-nakatsugi would be arranged on the fukuro-dana hadaka [裸] (without a shifuku), and resting on a shiki-kami [敷紙]*; but a natsume would be displayed tied in its shifuku. The shiki-kami was only used with a shin-nakatsugi.

While Jōō created both the large natsume (ō-natsume [大棗]) and the small natsume (ko-natsume [小棗])†, the large natsume more closely approximates the volume of the shin-nakatsugi. __________ *See the post entitled Nampō Roku, Book 3 (18.2): the Arrangement of an Ordinary Chawan and Chaire on the Fukuro-dana; and the Arrangement of a Shin-nakatsugi on the Fukuro-dana for more on this, including directions for making the shiki-kami. The URL for that post is:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/186916844698/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-3-182-the-arrangement-of-an

†The assertion that the ko-natsume should be used for koicha and the ō-natsume for usucha may be a later interpretation: the ko-natsume holds enough tea for no more than three portions of koicha, while Jōō is mentioned as having served tea to as many as six (or even ten) guests during a single za.

Furthermore, Jōō served each guest an individual bowl of koicha (meaning that more tea would be needed than for a single large bowl of tea that was served as sui-cha [吸い茶] -- the practice where a single bowl of koicha is shared by all the guests). What is more likely is that Jōō used whichever was suitable, depending on the amount of matcha that had been ground.

³Mizusashi no ue chakin ・ chasen [水指ノ上茶巾・茶筅].

This temae is technically referred to as chasen-kazari because the folded chakin, with the chasen resting on top of it, is “displayed” on the lid of the mizusashi.

Because the Shukō-chawan was a large bowl (it measured 5-sun 2-bu in diameter), the chakin was initially folded in half (rather than into thirds, as is usual when a smaller chawan is being used).

⁴Chashaku (茶杓).

This would have been a chashaku that was made to be used with the nakatsugi (or natsume).

During Jōō's lifetime a Shutoku* chashaku [珠德茶杓] (above) was probably been paired with the former; but one of Jōō's own chashaku would have been more appropriate when using a natsume†. __________ *Shutoku [珠德] was the name of the craftsman who made chashaku for Shukō (and possibly accompanied him from the continent when he emigrated to Japan). He worked in both ivory and bamboo; and the special feature of his scoops (the bamboo ones as well as those carved from ivory) is the prominent flaring of the butt-end of the handle.

†The fact that the chashaku is displayed on the tana suggests that the comment regarding the use of a natsume as being a suitable substitute for the shin-nakatsugi was added in the Edo period.

As Shibayama Fugen has remarked several times, most -- if not all -- of the writing was added by later people.

⁵Maru-bon [丸盆].

Both Shibayama Fugen and Tanaka Senshō understand this to be the meibutsu naka-maru-bon [中丸盆] that had been used by Ashikaga Yoshimasa.

This tray was 1-shaku 2-sun 3-bu in diameter. However, the tray itself seems to have been 1-shaku 2-sun across, with straight sides, and a raised rib 1-su 5-rin high in the middle of the side. The face of the tray had a large “gold” (probably brass, since the purpose was to prevent the face of the tray from being damaged by heat) plate inlaid in the lacquer, and the rim of the tray was adorned with a fukurin [覆輪] (edge) of the same metal.

The tray seems to have originally been made for carrying chafing dishes and other heated serving vessels from the kitchens to the residential apartments (in China -- this was the purpose of the metal inlay, to keep the tray from catching fire), and (like the other meibutsu trays used by Yoshimasa) was adopted for use in chanoyu because its dimensions conformed to what was required.

The original of this tray had been destroyed when Yoshimasa's storehouse was burned down during the Ōnin wars (sometime between 1467 and 1477). However, Yoshimasa was able to order a (Japanese-made) copy in mirror-finished black lacquer (without either the fukurin or the metal inlay), and this was probably the tray that Jōō originally used with this kazari.

⁶Taikai [大海].

The taikai was the oldest kind of chaire used in Japan* -- and its use predated the arrival of chanoyu (c 1403) by several hundred years. The karamono taikai chaire known as Maru-umi [丸海] is shown below.

The fact that the chaire overlaps the kane by one-third (in other words, the foot was placed immediately to the side of the kane) means that this was one of the large taikai chaire that had been used to hold the tea on the o-chanoyu-dana [御茶湯棚] in the days before chanoyu was brought to Japan.

[I have circled the words uchi ni taikai [中ニ大海), which are written above the drawing of the tray -- indicating that these large taikai were the proper chaire for use in this setting. This sketch was drawn by Nōami (能阿彌), and shows the arrangement of the o-chanoyu-dana that he approved.]

Because it was an adopted piece (rather than one of the chaire that had been used for gokushin tea), the taikai was being treated as inferior to the “proper” chaire -- even when these chaire had been imported from the continent.

Takahashi Sōan [高橋��庵; 1861 ~ 1937] mentions six karamono taikai-chaire† in his seminal work, the Taishō Mei-ki Kagami [大正名器鑑], and the pertinent data for each has been entered in the following table.

Thus, while there was no absolute size, the taikai used in this temae were usually a little over 3-sun in diameter.

Note that while the line representing the kane is done in red, the chaire only overlaps the kane by one-third (like an ordinary chaire, rather than a meibutsu): the red ink is intended to draw attention to the fact that, even though the taikai is resting on a tray, it is displayed as if it were an ordinary chaire. ___________ *In the Chanoyu San-byakka Jō [茶湯三百箇條], which Jōō ascribed to Shukō (though the only surviving version of this document was edited extensively by Jōō’s disciple Uesugi Kenshin, and subsequently by Sen no Dōan and his disciple Kuwayama Sōzen, and the content clearly bears the stamp of these individuals), the taikai [大海] is considered to be the intermediate stage between the ko-tsubo [小壺] and the large katatsuki [肩衝], and so can be used in either way (tea was “pulled out” of the ko-tsubo -- sukuu [掬う] being the Japanese verb for this action -- with the side of the chashaku, but it was scooped out -- here the verb is kumu [汲む] -- from a katatsuki).

†A number of old Seto taikai chaire are also mentioned in the Taishō Mei-ki Kagami -- which is to be expected because every mansion had to have an o-chanoyu-dana, so there were many locally produced examples of this necessary object (only the wealthiest households could afford the imported pieces).

But both Shibayama Fugen and Tanaka Senshō, however, state that this chaire must be a karamono taikai, according to tradition. This is why I have not included the Japanese-made pieces in the list.

==============================================

I. The first arrangement.

Here the Shukō-chawan is arranged, together with a shin-nakatsugi, on the ten-ita of the fukuro-dana.(the nakatsugi without a shifuku, and resting on a shiki-kami [敷紙]*). The Shukō-chawan, being the preeminent chawan for wabi-no-chanoyu†, it is arranged as a mine-suri [峰摺り].

A chashaku -- probably made by Shukō‘s chashaku craftsman Shutoku [珠德]‡ -- is placed on the extreme left side of the kō-dana, while the chakin and chasen are arranged on top of the mizusashi (so that a kae-chawan is unnecessary).

While I have shown the Shukō-chawan without a shifuku in my sketch (so that the relationship between the cha-damari [茶溜り] -- the depressed circle in the bottom of the chawan, into which the matcha is transferred -- and the kane), the chawan would be displayed in its shifuku, as per Jōō’s sketch.

With respect to kane-wari, the tana is han [半] (with the exception of the chashaku, all of the objects arranged on it contact a kane). Taken together with the chabana in the toko**, and the kama in the ro, this gives a han count to the goza. ___________ *See footnote 2, and its sub-note “*”, above. The shiki-kami allows the nakatsugi to “overlap” its kane -- something impossible otherwise, since the straight sides mean that, when placed immediately adjacent to its kane, unlike most other utensils, there will be no “interaction” between the two at all.

†The Shukō-chawan was probably never used for drinking koicha by Shukō. It was the kae-chawan that he used when serving tea in his temmoku.

While sometimes the kae-chawan was used to serve usucha to the shōkyaku’s attendants (by mixing the cha-no-ato [茶の跡] in the temmoku with some more hot water, and then pouring this into the kae-chawan -- which was occasionally used as a sort of saucer when a lacquered Chinese temmoku-dai was not available), its primary purpose was to allow the host to bring the chakin and chasen into the room, serve as a vessel in which the chasen could be cleaned with cold water at the end of the temae, and then be used to take the chakin and chasen back to the katte at the conclusion of the service of tea.

The use of the kae-chawan to serve tea -- to the shōkyaku -- was a defining element of wabi-no-chanoyu (where the “proper” utensils were considered to be things that had been “neglected” theretofore in the practice of gokushin tea).

‡Shutoku [珠德] was active during the second half of the fifteenth century, but his dates of birth and death are unknown. His name suggests that he was a disciple of Shukō’s (as well as the man who carved chashaku -- in both ivory and bamboo -- for him), and he may have accompanied Shukō to Japan from Korea.

As for the chashaku itself, if a natsume is used (rather than a shin-nakatsugi), then one of Jōō‘s chashaku would be more appropriate (since Jōō created the natsume, just as Shukō did the shin-nakatsugi). A chashaku made by later generations of chajin, or by the host himself, would probably not be appropriately displayed in this way (since the chashaku does not contact a kane, its absence would not change anything -- though its absence would present the difficulty of how to get the chashaku into the room, since a kae-chawan is not available: perhaps it could be placed in the ji-fukuro; but the better idea would be to use one of the appropriate sort).

The chashaku is placed on the extreme left side of the tana because it must always be to the left of the tea container (and the shiki-kami means that the nakatsugi occupies all the space to the right of the kane).

This is an important point to keep in mind -- and not just in relation to this arrangement: when performing chasen-kazari, the chaire is usually displayed inside the chawan, and in this case (contrary to what many modern schools teach) the chashaku rests across the rim of the chawan on the left side of the chaire. Nevertheless, the present temae is, indeed, a variation on chasen-kazari.

**Assuming the chabana is displayed in the middle of the toko -- either resting on an usu-ita on the floor of the toko, or suspended from the hook that is inserted into the middle of the back wall.

If the chabana is suspended on the bokuseki-mado (or from a hook nailed into the minor pillar on the outer-wall side of the toko), then the toko is chō [調] -- which (like an empty toko) would give a chō count to the za, if all of the other things remained the same.

——————————————–———-—————————————————

II. The second arrangement.

In this arrangement, a (large) taikai chaire (of the sort that was used on the o-chanoyu-dana in the years before chanoyu was brought to Japan at the beginning of the fifteenth century). According to both Shibayama Fugen and Tanaka Senshō, the “maru-bon” in question is the meibutsu naka-maru-bon [中丸盆] that was used by Ashikaga Yoshimasa*.

Because this chaire was adopted for use in chanoyu from a different purpose (the o-chanoyu-dana -- which was not considered to be chanoyu, even though matcha can also be served in that way), it was considered to be an “ordinary” utensil. For this reason, even though it is displayed (and will be handled) on a tray, it still overlaps its kane by one-third†.

According to the Nampō Roku, of the six meibutsu trays associated with Ashikaga Yoshimasa, only the two smallest trays -- the Gassan nagabon [月山長盆] (outer dimensions, 1-shaku 3-sun 2-bu x 9-sun 2-bu), and the round Chōshō rai-bon [趙昌雷盆] (measuring 1-shaku 1-sun in diameter) -- were cleaned with the host’s temae-fukusa‡. The other four trays (of which the naka-maru-bon was one) were cleaned with the habōki. This is why the habōki is displayed on the maru-bon on the fukuro-dana at the same time as the hishaku. The chawan (probably something like an ido-chawan during the period when the original document on which Book Three is based was written) is placed in the ji-fukuro.

According to the Chanoyu San-byakka Jō, the fukuro-dana should be placed either 8-sun, or else 1-shaku 2-sun, away from the upper corner of the ro. While 8-sun generally suffices (which would be the case of for all of the arrangements discussed thus far), the present arrangement needs it to be 1-shaku 2-sun away, so that there will be sufficient room for the maru-bon (which is lowered to the mat so the karamono taikai can be handled upon it).

And finally, looking at the kane-wari, the tana is a straight-forward han [半] (the chawan in the ji-fukuro is ignored for this purpose). Assuming that the toko is also han**, this will yield a han count for the za. ___________ *This tray, which measured 1-shaku 2-sun 3-bu in diameter, is described more fully above in footnote 5. The original was destroyed during the Ōnin wars, and the tray that Jōō used for this arrangement was the copy made for Yoshimasa by Haneda Gorō.

The reader should keep in mind that all of the arrangements described here use very specific utensils, most of which existed as only a single example. If one managed to acquire the utensils specified, then one could perform this temae. And if not, using copies was generally frowned upon (though one could sometimes use other utensils that matched the important criteria).

†As always, the foot is placed so that it is immediately adjacent to the kane with which the chaire is associated. This allows the chaire’s bulk to “overlap” the kane in the appropriate manner. Any necessary adjustment can be made because the kane is 3-bu wide, and the edge of the foot of the chaire can be found anywhere within that space. This is explained in greater detail in the appendix that is found at the end of the post entitled Nampō Roku, Book 3 (18.5): Arrangements for a Meibutsu Futaoki, and for a Karamono Chaire. The URL for that post is:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/187172815712/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-3-185-arrangements-for-a

‡Trays smaller than these were, of course, also cleaned with the fukusa (though these “chaire-bon” did not exist until created by Jōō, many decades after Yoshimasa’s time): as can be seen in the chart that was included under footnote 6, the diameter of the foot is always close to one third of the total diameter (any deficiency can be made up by the fact that the “kane” is 3-bu wide, and the edge of the foot can be located anywhere within that space -- this was explained in the appendix at the end of the previous post).

**The room is always han, because it necessarily must contain the kama in the ro -- and generally nothing else (since the fukuro-dana was the original kind of wabi arrangement, the first departure from the formality of the daisu).

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 7 (6a): Addendum.

I was asked to provide additional details regarding the ko-Temmyō kimen-buro [古 天命 鬼面風爐], and why Furuta Oribe found it necessary to place it on a thick ceramic floor tile, and it is to address this question that I decided to publish this addendum.

The photo on the left shows what the large Temmyō kimen-buro would have looked like during the last years of Rikyū’s life (the furo in the photo, like the one that was owned by Ashikaga Yoshimasa, and passed through the hands of Oda Nobunaga, was made at Sano Temmyō [佐野天命] during the fifteenth century). Furo like these (with matching kiri-kake kama) were made to be used on the o-chanoyu-dana [御茶湯棚] that were commonly found in an anteroom attached to the shoin in the mansions of the upper classes. Rikyū created the small unryū-gama for Nobunaga’s furo because the furo had been cracked when Mori Ranmaru (Nobunaga’s page-lover) threw it across the shoin to scatter the burning charcoal around the room, in order to start the fire that burned down the Honnō-ji (and so prevented Akechi Mitsuhide from collecting Nobunaga’s head), after Ranmaru assisted his lord to commit seppuku. The crack had so weakened the rim and sides of the furo that it was feared that it could no longer support the weight of a kiri-kake kama safely.

Rikyū‘s first small unryū-gama (which had a beaten copper lid, because bronze was not yet being produced in Japan) is shown below. (Subsequently made copies -- apparently including those made for Rikyū, usually had cast-iron lids, though they usually imitated the indented shape of the original lid.)

That furo and kama were originally used on the Yamazato-dana [山里棚] in Hideyoshi’s 2-mat Yamazato-maru [山里丸], the wabi tearoom erected on the inner bank of the moat in Hideyoshi’s Ōsaka castle. Sometime later (perhaps after Rikyū’s death), the old Temmyō kimen-buro and its small unryū-gama were moved to the wabi small room on the grounds of Hideyoshi’s Shigetsu-Fushimi Castle in Kyōto, and it was there that the furo was further damaged during the earthquake of 1596 (which collapsed the roof of that small room). It was during that event that most of the rim was broken away, leaving the furo as it appears in the right photo (this is a photo of the actual furo, as it exists today).

Rikyū based the original height of the kama above the rim on the height of the mouth of the original kiri-kake kama (as was the diameter of the small unryū-gama, which was the same as the diameter of the kiri-kake kama’s mouth). After the earthquake, since most of the rim was broken off, Oribe decided that the kama should be settled lower in the furo (so that the mouth of the kama would be the same distance above the broken edge as the original had been above the intact rim).

Furthermore, since the original small unryū-gama had been destroyed in the earthquake, a new kama had to be provided. Oribe instructed Yojirō (who had been Rikyū’s kamashi [釜師]) to make the new kama conical (with the middle only the same diameter as Rikyū’s original kama), with the angle the inverse of that of the kiji-tsurube (with which the small unryū-gama was most frequently used). And, rather than using the Chinese dragon design that had been copied from the seiji-unryū mizusashi [青磁雲龍水指], Oribe used the Korean dragon that was found on one of the battle standards that had been captured during the invasion of Korea. Today, this version of the unryū-gama is usually referred to as the Sōtan unryū-gama (it is made in three sizes -- small, medium, and large), for the reason described below.

Because Hideyoshi was generally averse to using damaged utensils (and, probably because this particular furo would remind him of the loss of his Fushimi Castle, which was to have been his jewel), it seems that he no longer employed this furo and its new kama when serving tea with his own hands. So, when the Sen family name was restored, Hideyoshi presented this furo and its new kama to Sen no Shōan (who was the biological son of Hideyoshi’s retainer Miyaō Saburō Sannyū -- since Saburō Sannyū had literally saved Hideyoshi’s life during the battle of Yamazaki, this may have figured largely into Hideyoshi’s decision to restore the Sen family under Shōan).

Thus, this was the furo and kama (along with the kiji-tsurube as their mizusashi) that Shōan and his son Sōtan used whenever they served tea. The furo koicha-temae, as taught by all of the modern schools, was ultimately based on the way that Sōtan served tea with this kama and furo (and his attempt to continue serving tea in that way, even when the utensils were changed so that doing so was no longer technically possible).

Later, Sōtan (or one of his sons) had a large-size copy of this kama made, along with a large iron Dōan-buro (that features a bas relief design of waves, clouds, and falling rain), also with a (deliberately) broken rim. While the small unryū-gama has to be constantly replenished throughout the temae (each time water is taken from the kama, a hishaku of cold water must be added immediately thereafter), which can become troublesome, the large unryū-kama can be used just like any other furo-gama. It is also large enough to be used in the ro, as an ordinary tsuri-gama.

0 notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 5 (26): Display of the Hoya [ホヤ] ([One] Among Five [Arrangements]).

26) Hoya kazari itsutsu no uchi [ホヤカサリ五之内]¹.

[The writing reads: koboshi oroshite hoya koko ni (コホシヲロシテホヤコヽニ)²; ৹³; ji (字)⁴; hishaku kaku no gotoki hiku (ヒサク如此引)⁵.]

_________________________

¹Hoya kazari itsutsu no uchi [ホヤカサリ五之内].

“Display of the hoya, [one] of five [arrangements].”

The hoya [ホヤ]* has been regarded as the highest futaoki since ancient times; and, in consequence of this, it required special handling whenever it was being used. In this particular temae, the hoya is the featured utensil.

While the habōki is associated with the kane immediately to the left of the central kane in the Enkaku-ji manuscript, in Shibayama Fugen’s teihon [底本] it is placed on the end-most kane, as shown below.

While this might seem reasonable at first, the presence of the habōki on that kane might make it difficult to place the chaire’s shifuku on the ten-ita during the temae -- and it was probably for this reason that the habōki was associated with the second kane in the other sources for this arrangement.

As for the “five arrangements for the hoya” that are referenced in the title, these are the arrangements discussed in the entries:

◦ Seiji unryū・meibutsu nasu・meibutsu temmoku kazari nari [青磁雲龍・名物茄子・名物天目飾也] (Part 16)

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/621478104540528640/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-5-16-the-display-of-the-seiji

◦ San-shu gokushin nagaita kazari nari [三種極眞長板飾也] (Part 17)

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/622112317172318209/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-5-17-the-gokushin-arrangement

◦ Rai-bon ni-shu, shin kazari nari [雷盆二種、眞飾也] (Part 19)

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/623108862521851904/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-5-19-20-the-shin-%E7%9C%9E

◦ Kamakura isshu kazari [鎌倉一種飾] (Part 23)

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/624014874145652736/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-5-23-display-of-the-kamakura

◦ Hoya kazari itsutsu no uchi [ホヤカサリ五之内] (Part 26, which is the present post).

In the first part* of Book Five of the Nampō Roku, these are all of the daisu arrangements in which the hoya plays a part. (There is one additional instance in which the hoya is mentioned: the arrangement for the o-chanoyu-dana†. However, that is not a daisu arrangement, and so was not considered here.) ___________ *Hoya [ホヤ] is usually written hoya [火屋] (which means an incense burner that is provided with a cover that keeps things from falling onto the fire or smoldering incense), and this is appropriate to one class of objects that are used in this way -- miniature censers that were used by the Emperor during a ceremony to purify the four directions that was performed at dawn on the first day of the New Year. However, the original hoya (this is the object shown in the photo) was a Byzantine cloisonné reliquary that could not be used as a censer (the lid has no holes in it), perhaps brought to China by the Nestorian diaspora, whose priests are said to have converted the Tang emperor to a version of their interpretation of Christianity around 635 (though some scholars have questioned whether it was the followers of Nestorius, or one of the other Orthodox sects that flourished in western Asia, that first proselytized China). In the Orthodox ritual, relics (usually fragments of bones) were arranged on the altar in miniature ciboria such as this; wherefore the original name for this object may have been hone-ya [骨家] (cognate with forms such as hiki-ya [挽家]), contracted or conflated with the censer called hoya on account of a similarity of shape.

†Book Five consists of two distinct parts:

- the first part is concerned with historical arrangements for the large shin-daisu, from the early fifteenth century through the first half of the sixteenth century (the collection ends with a series of arrangements illustrating the way that the daisu was decorated for the Shino family’s kō-kai [香茶]);

- the second part deals with arrangements for the small shin-daisu (which is the sort of daisu that is used in the inaka-ma 4.5-mat room, the room that Jōō came to prefer during his middle period), as well as the arrangements for the kyū-dai daisu [及第臺子] and the naga-ita [長板] (this board is referred to as the “naka-ita” [中板] in the Nampō Roku) in the kyō-ma setting. Most of the arrangements discussed in this part of the book were created by Jōō himself (as, apparently, was the system of seven kane that he uses to interpret the arrangements).

Between these two is a brief section that purports to discuss the origin of the kane; though the sketch that seems to show the shiki-shi [敷き紙] has been interpreted as showing the large daisu divided by 3-kane (rather than 5), at least since the time of Tachibana Jitsuzan, resulting in confusion rather than clarity.

†There is an aspect of this matter that should be pointed out here: the o-chanoyu-dana [御茶湯棚] was a built-in area where tea was prepared. It was always located in the tsugi-no-ma [次ノ間] (an anteroom usually of 2-mats size) that was attached to the shoin, and this anteroom was usually off limits to the guests, at least in Japan. Nevertheless, many of the great meibutsu utensils were still used there -- as, in this case, the hoya. In those days, it was believed that the use of these utensils (which corresponded exactly to the demands of kane-wari) would enhance the “positive energy” of the tea, making it more beneficial to the health of the person who drank it.

It appears that the idea of the small room, which Rikyū brought back from Korea, was based on the practice of inviting the guests into the 2-mat tsugi-no-ma so that they could receive their bowls of tea directly from the hands of the person who prepared them, which he had observed on during his sojourn on the continent. This is why Rikyū held that the original small room was of 2-mats -- even though, in Japan, the historically earliest “small rooms” used by the machi-shū chajin were of 3 or 4 mats, as explained elsewhere in the Nampō Roku.

²Koboshi oroshite hoya koko ni [コホシヲロシテホヤコヽニ].

“After the koboshi has been lowered [to the mat], the hoya [should be placed] here.”

³৹.

This small circular mark is called a ku-ten [句点]. A ku-ten is most commonly used as a full stop (it is occasionally seen in poetry), though its purpose here is unclear (since it is not placed at the end of a line, but below, and in between, two lines of text).

Tanaka Senshō adds a ku-ten to the end of each phrase (コホシヲロシテホヤコヽニ。ヒサク如此引。), apparently in response to this (no other version of the text includes these punctuation marks -- and, indeed, the “৹” appears to have been ignored by their editors).

⁴Ji (字).

Or, possibly, sō [宗]. The gyō-sho [行書] form of both kanji is similar enough that they could be confused with each other.

If it is “ji” [字] (meaning “character”), perhaps this notation was originally aka-ji [赤字], meaning “red characters” -- that is, the characters of the notes were written in red ink (this compound -- or, at least in the Sadō Ko-ten Zen-shu [茶道古典全集] edition of the Nampō Roku, aka-gaki [赤書] -- is sometimes found as a superscript notations in versions of the text that were printed only in black, to indicate those portions of the text that were written in red in the original document from which they were copied).

If it is “sō” [宗], then perhaps Tachibana Jitsuzan mistakenly started to write Sōeki [宗易] here, rather than at the end of the entry (which is where Rikyū’s name is usually found*).

None of the commentaries include, or discuss, the significance (or lack whereof) of this kanji. ___________ *As has been mentioned before, if Jitsuzan was not responsible for adding Rikyū’s name -- as well as Sōkei’s (as the purported recipient of these secret texts) -- to these documents, then these things were most likely added in the early Edo period, along with at least parts of the first entry (which was meant to establish the connection between Rikyū, and Sōkei, and the kaki-ire that were added to the sketches) -- to associate the collection, which, in fact, was assembled by Jōō (during his middle period), with Rikyū and his “school” (meaning the “machi-shū,” as a recognized movement within chanoyu, and/or the Sen family, though neither of these Edo period institutions have any actual connection with Rikyū).

⁵Hishaku kaku no gotoki hiku [ヒサク如此引].

“The hishaku is rested* as [shown] here.” ___________ *Hiku [引く] is the verb traditionally used to describe the hishaku being rested on the futaoki.

Some schools interpret the kanji “hiku” to mean “strike,” and so (audibly) hit the hishaku against the futaoki (before dropping the handle onto the floor); but (at least according to Rikyū’s own writings) this is not historically justifiable.

The hishaku (according to Rikyū) should be rested on the futaoki by moving the “corner” (the point where the side meets the bottom) of the cup into the toi [樋] (the hole or depression -- the kanji means “gutter” or “rain-pipe” -- that must always be found in the middle of the top of any object used as a futaoki), and then gently lowering the handle to the mat -- because (according to him), striking the hishaku against the futaoki (which apparently was a feature of the machi-shū temae), and dropping the handle, can cause the join to become loose, resulting in the hishaku’s leaking during the temae -- which would be reprehensible (even though Sōtan included the deliberate dripping water on the mat as one of the “features” of his temae).

——————————————–———-—————————————————

◎ Analysis of the Arrangement.

The Enkaku-ji manuscript shows the habōki resting on the first kane to the left of the central kane, with the hoya arranged as a mine-suri [峰摺り] on the central kane. On the ji-ita, the furo-kama and other kaigu are arranged in the usual manner -- none of which are meibutsu utensils, but simply the usual bronze ones that were traditionally used on the daisu.

The chawan and chaire will be brought out from the katte at the beginning of the temae. While neither of these things should be meibutsu utensils, they should be of a quality suitable for use with the daisu. In Jōō‘s day, the chawan would probably have been something like an ido bowl, while the chaire might have been a large katatsuki (as shown), or even a large natsume -- since the point of this temae is to appreciate the hoya.

During the temae, the habōki remains on the ten-ita, while the hoya is placed on the ji-ita (once again, on the central kane). In the manuscript copies of this entry, the hishaku is shown resting on the hoya during the temae, with the handle extending toward the left (and this is how I have depicted it in the temae sketches). This, however, is problematic -- because the hishaku was usually kept in the shaku-tate when one was present*.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------