#Unemployed (Desocupados)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Unemployed (Desocupados)

Antonio Berni

1934

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

MWW Artwork of the Day (7/6/24) Antonio Berni (Argentine, 1905-1981) Desoccupados (The Unemployed)(1934) Tempera on burlap, 213.4 x 404.8 cm. Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires

Delesio Antonio Berni was an Argentine figurative artist. He is associated with the movement known as Nuevo Realismo ("New Realism"), a Latin American extension of social realism. He began painting realistic images that depicted the struggles and tensions of the Argentine people. His popular Nuevo Realismo paintings include "Desocupados (The Unemployed)" and "Manifestación" (Manifestation). Both were based on photographs Berni had gathered to document, as graphically as possible, the "abysmal conditions of his subjects."

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

red herring press

is based in the easterly town of Great Yarmouth. It houses a risograph printer, used to publish and distribute local writing in the town.

Over the next bit of time, red herring press plans to run free sessions where people can learn to print (and use for their own projects), publish pamphlets of poetry and fiction by local people as well as on local history and currents, host readings and discussions and film screenings, start a multilingual collectively-run community newspaper/newsletter, open a (very small) local history and radical literature library, house a Writer’s Workshop group, and be a resource for local groups struggling against austerity and the consequences of capitalism.

* * * *

What does it mean to have ‘roots’ in a place? And what, and who, are those roots attached to?

There is immense focus on what has left Great Yarmouth over the years. The dwindling tourists, relocated art school, the closing of the last smokehouse, the diminishing fishing industry, shipbuilding industry, port; the high street increasingly derelict. Cheap studio and exhibition spaces are often used by artists living elsewhere, who rarely contribute to the town’s inner social or cultural life.

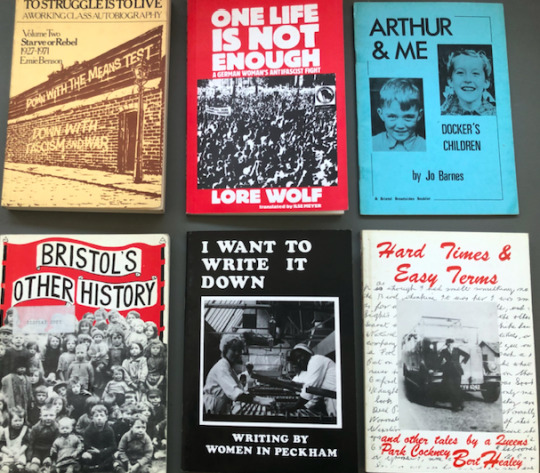

Despite the omnipresence of shops and businesses with seemingly little economic viability (the stall that sells only mushy peas, junk shops that open only between 2-4pm, the club that plays only Ministry of Sound CDs), there are no bookshops in Great Yarmouth. Why? Maybe cause of this widespread idea that a working class seaside town has no interest in, or need for, literature. That it is irrelevant: both literature to the town, and the town to literature. For the state and its bourgeois backscratchers, the ‘problem’ is seen as an impossibility to persuade or ‘educate’ working people to read books, rather than, as a Centerprise youth worker wrote in 1977: “seeing the issue as a result of two centuries of active suppression of working class people becoming too interested in politics and literature… The incalculable years of imprisonment spent by thousands of individuals in the last 150 years for daring to publish, or distribute writings on economics, philosophy, literature and other oppositional categories of thought.” This conscious strategy is clear in the government’s response to illiteracy: mobility scooters. This idea, and condescending responses around ‘the education of’ working people, led working class readers and writers in the 70s and 80s to set up their own bookshops and publishing presses across the UK, as documented by the Federation of Worker Writers and Community Publishers.

And then the dangerous liberalism (disguised as militancy) of trying to claim that people don’t need books like they need food, housing, work, warmth - as if we can only aspire to what we ‘need’ and not beyond it. As if survival is all we’re asking for. As if reading, writing and distributing literature (whether read or listened to) wasn’t fundamental to struggles for better material conditions in apartheid South Africa, or 70’s Nicaragua, or the Movimiento de Trabajadores Desocupados (Unemployed Workers Movement) in Argentina, or the Diggers’ occupations for common land in 1600s England, or liberation struggles led by communist peasants in Palestine. As if literature cannot be specific to our own lives.

But culture isn’t a ‘right’, it’s a real living force - one we’re already making and participating in daily. When workers in Argentina were faced with the shuttering of their factories, they occupied them - creating spaces inside for a cultural centre, theatre and printmaking workshops, a free health clinic, a people’s lending library, an adult middle and high school education program, and a University of the Workers. Yet the argument that ‘books are necessary too’ often goes hand-in-hand with gentrification and displacement, under the guise of ‘cultural development’.

With this comes the (western) assumption that much writing - particularly poetry - cannot relate to the conditions of a place where there is high unemployment, poverty, prison leavers, homelessness, precarious immigration, flats in which people die from easy-to-avoid fires and a lack of carbon monoxide detectors, a place in which Universal Credit was trialled and the number of people accessing foodbanks multiplied. Where one day you see neo-Nazi tattoos branded on arms, a car flashing Confederate flags, and a postbox address for the National Front; and the next, people shouting in the faces of racists, community meals where English is exchanged for Portuguese is exchanged for Lithuanian is exchanged for Guinensi, where people embroider quilted scraps of material with “No to austerity”, “No to immigration controls”, “No to the closure of women’s refuges”.

A real distinction does exist between culture and conditions, though: there is a difference between funding arts projects and funding housing. Books can’t house or feed us, but can’t we demand both? And it’s not difficult to separate the everyday practice of culture, to which everyone has a claim, from a literary establishment and industry that has, as the qualified arbiter of taste, its own reasons for trying to persuade us otherwise. That posits ‘craft’ over the political and social principles of a poem: who cares if a poem is racist or homophobic if it’s well written?

We are drawn to writing for our own reasons and histories - distinct from a literary industry that publishes writing from outside official state culture only if it can be labelled and sold as ‘prison writing’ or ‘crazy writing’ or ‘poverty writing’ or ‘exotic writing’. Its designated ‘otherness’ and ‘unprofessionalism’ becomes its selling point, its marketability.

When a distorted and dying culture cannot provide any hopes for living in a different way, how can we build our own sustainable, amateur structures to write and read and share one another’s work?

Email: [email protected]

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/redherringpress/

Risograph printing: designed to be a high-volume, fast and low cost photocopier, riso machines work a bit like screen printing: a print image is burned onto a master sheet, which is then wrapped round a print drum. Ink is pushed through this stencil onto the paper. First produced in Japan in 1986, risos were popular with schools, churches, and political groups to mass produce posters, flyers, pamphlets and small books.

A risograph printer

Printers: Many printshops were set up in the 60s and 70s across the UK. Anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist, anti-hierarchy, anti-racist, feminist, queer, anti-state. The radical printshop itself was not a new thing: printers of 'controversial’ material have existed in the UK - often at the risk of imprisonment - since at least the 17th century. Their aim was not just to produce politically radical materials but also to enact those politics through their non-hierarchical and collective organisational and production practices.

Books from the Trade Union Congress Library’s collection of publications from the Federation of Worker Writers and Community Publishers.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

"En nuestro mundo, la ociosidad se ha convertido en desocupación, lo cual es muy distinto: el desocupado está frustrado, se aburre, busca constantemente el movimiento que le falta / In our world, idleness has become unemployment, which is very different: the unemployed are frustrated, bored, constantly looking for the movement they lack."⠀ ⠀ Milan Kundera⠀ La lentitud / Slowness⠀ & Andrew Mar @andrewkmar (artist)⠀ ⠀ ⠀ #surrealportrait #surrealart #popsurrealism #retroart #illustration #illustrations #illustrationart #illustrationartits #illustrationartist #illustratror #illustrators #illustrated #illustrate #illustration_best #illustree #illustrarts #illustrationage #ilustracion #ilustra #illustrazione #illustrazioni #ilustración #ilustrador #nightmare #lowbrowart #weirdart #marcopolorules #vagabondwho #jesuislesurrealisme #andrewmar https://www.instagram.com/p/CAp4Ec4nXje/?igshid=113jsrsto0wsi

#surrealportrait#surrealart#popsurrealism#retroart#illustration#illustrations#illustrationart#illustrationartits#illustrationartist#illustratror#illustrators#illustrated#illustrate#illustration_best#illustree#illustrarts#illustrationage#ilustracion#ilustra#illustrazione#illustrazioni#ilustración#ilustrador#nightmare#lowbrowart#weirdart#marcopolorules#vagabondwho#jesuislesurrealisme#andrewmar

1 note

·

View note

Text

An Introduction to Mutual Aid

While mutual aid is a tactic that has been used in human society throughout history, the ideas behind it as a larger theory were developed by Peter Kropotkin in the 1902 book Mutual Aid: a Factor in Evolution. Kropotkin was a Russian scientist, zoologist, and philosopher who was particularly interested in anarchism and evolutionary theory. Thanks to his scientific background, not only is Kropotkin's work a success as political theory, his work on organization and cooperation has had a lasting effect on biology.

In the book, Kropotkin proposes that not only are systems of social organization in which individuals form larger collectives to aid one another our natural instinct, they're also evolutionarily desirable. It came about as an important response to the ideas of social Darwinism, that is, that existing social orders in which humans compete with one another and the fittest survive is the natural and optimal form of society. Kropotkin refutes this by emphasizing the struggle between cooperatives and their environment, rather than individuals fighting with one another over scarce resources, Kropotkin is able to create a framework of survival and development that reveals the benefits of collectivization. Through this focus on cooperation rather than competition, mutual aid can work to undermine the capitalist transformation of social into economic relationships.

In Rebecca Solnit's A Paradise Built in Hell, the author analyzes reactions to natural disasters and finds people coming together to support each other in the face of chaos. People come out of horrendous situations like the San Francisco earthquake feeling a sense human connection and shared purpose. In an odd way, the disasters allow people to break out of the constraints of capitalism and find new relations to each other that are mutually beneficial. Part of this takes form in the aid provided to one another in the form of food, clothing, shelter, and medical treatment. Of course, it's worth noting the role that the existing activist and organizer networks play in the rapid coalescence of the support systems. While in those situations there is a will to help, its efficacy is tied to pre-existing organizations.

If we are to expand our concept of “disaster times”, the image we are often presented with of revolutionary periods focuses on the upheaval, painting an image of a society in chaos in which all solidarity is lost and each must fend for themselves. However, if we are to think of a revolution as a disturbance of the status quo similar to a natural disaster, then mutual aid would be an essential and natural response to the loss of order that would come with the overthrow of the state. In fact, while the "restoration of order", or the status quo, following a great disaster may seem like an immediately desirable outcome, the reintroduction of hierarchical systems of state and capital serve to destroy the very natural social organizing that can naturally set to right the community.

Of course, the examples go beyond environmental disaster. People still find ways to organize for one another under the rule of capitalism. When Argentina suffered an economic crisis in 2001, defaulting on over $100 billion of public debt, in part brought on by austerity measures imposed by the IMF, the Movimientos de Trabajadoes Desocupados, or Movements of Unemployed Workers, organized to support those hit by the country's economic crisis. MTD served both as immediate material support as well as a way to challenge traditional representations of the unemployed as lacking political agency and revolutionary potential. Additionally, with a focus on the value of reproductive labor and relocation to the sites of people’s everyday lives, MTD was able to create a political body that was more gender and age inclusive. Mutual aid allows the political to be taken out of factories and halls of government and into neighborhoods.

Their organization sought to create schools, soup kitchens, health clinics, daycares, community gardens, social centers, legal clinics, and co-ops all operated autonomously by the local people. It built on the self-activity of the working class as expressed through the practice of everyday life and social organization in neighborhoods to create a radical, horizontal system. Through the MTDs, participants were able to both provide for themselves materially, while also creating a new social framework in which they were no longer helpless atomized individuals, but rather a powerful collective able to determine their own lives.

Mutual aid projects can function as a form of prefigurative politics that demonstrates the way that society should be organized to those who may not be completely sold on socialism while directly providing for their needs. Not only that, but it can also empower them to aid others. Ideally, by bringing more people into system, it could reproduce and expand its power and take in a greater number of people. On a large scale, a mutual aid community could form a dual power system, performing all of the basic tasks of the state without looking to it for any authority and challenging its legitimacy. In fact, through the state's necessary suppression of natural cooperation to support its hierarchical structure, it produces a system that is not only less equitable, but also one that is less productive. Rather than allowing the community to self determine and flourish, resources are wasted serving the limited goals of the individuals who seek to benefit themselves alone. Kropotkin notes this, writing: "Legislators confounded in one code the two currents of custom of which we have just been speaking, the maxims which represent principles of morality and social union wrought out as a result of life in common, and the mandates which are meant to ensure external existence to inequality”.

Ultimately, mutual aid is one way of actively resisting capitalism while reaching for a new political horizon.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

PIQUETEROS / 400 ML (proyecto) El Movimiento Piquetero en Argentina Este fenómeno ha surgido de las organizaciones de desocupados, los cortes de ruta han sido desde su origen el medio de expresión de sus necesidades. Reúne a distintos componentes sociales desocupados que pasaron por la experiencia de la lucha sindical, a una enorme población empobrecida de los barrios. El deterioro acelerado de la calidad de vida crea un clima de alta frustración y protesta formando “piquetes” de huelga. El Movimiento Piquetero pasó de los cortes de ruta aislados a la huelga general y al plan de lucha nacional. El movimiento piquetero tiene como eje central las reivindicaciones de este grupo que representan las necesidades de los estratos más pobres de la sociedad. The Piquetero Movement in Argentina This phenomenon has emerged from the organizations of unemployed, the route cuts have been originated from the middle of expression of their needs. It brings together various social components unemployed who went through the experience of union struggle, a huge impoverished population of the districts. The accelerated deterioration of the quality of life creates a climate of high frustration and protest forming "piquetes" to strike. The Piquetero Movement went from route cuts isolated for a general strike and the plan for national struggle. The piquetero movement whose core demands of this group representing the needs of the poorest strata of society. #piqueteros #400ml #stencil #lata #aerosol #spray #plantilla #nazza #nazzastencil

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Delesio Antonio Berni (May 14, 1905 – Oct 13, 1981) was an Argentinian figurative artist. He is associated with the movement known as Nuevo Realismo, a Latin American extension of social realism. His work, including a series of Juanito Laguna collages depicting poverty and the effects of industrialization in Buenos Aires, has been exhibited around the world.

var quads_screen_width = document.body.clientWidth; if ( quads_screen_width >= 1140 ) { /* desktop monitors */ document.write('<ins class="adsbygoogle" style="display:inline-block;width:300px;height:250px;" data-ad-client="pub-9117077712236756" data-ad-slot="1897774225" >'); (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); }if ( quads_screen_width >= 1024 && quads_screen_width < 1140 ) { /* tablet landscape */ document.write('<ins class="adsbygoogle" style="display:inline-block;width:300px;height:250px;" data-ad-client="pub-9117077712236756" data-ad-slot="1897774225" >'); (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); }if ( quads_screen_width >= 768 && quads_screen_width < 1024 ) { /* tablet portrait */ document.write('<ins class="adsbygoogle" style="display:inline-block;width:300px;height:250px;" data-ad-client="pub-9117077712236756" data-ad-slot="1897774225" >'); (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); }if ( quads_screen_width < 768 ) { /* phone */ document.write('<ins class="adsbygoogle" style="display:inline-block;width:300px;height:250px;" data-ad-client="pub-9117077712236756" data-ad-slot="1897774225" >'); (adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); }

Berni was born in the city of Rosario on May 14, 1905. His mother Margarita Picco was the Argentine daughter of Italians. His father Napoleón, an immigrant tailor from Italy, died in the first World War.

In 1914 Berni became the apprentice of Catalan craftsman N. Bruxadera at the Buxadera and Co. stained glass company. He later studied painting at the Rosario Catalá Center where he was described as a child prodigy. In 1920 seventeen of his oil paintings were exhibited at the Salon Mari. On November 4, 1923 his impressionist landscapes were praised by critics in the daily newspapers La Nación and La Prensa.

The Jockey Club of Rosario awarded Berni a scholarship to study in Europe in 1925. He chose to visit Spain, as Spanish painting was in vogue, particularly the art of Joaquín Sorolla, Ignacio Zuloaga, Camarasa Anglada, and Julio Romero de Torres. But after visiting Madrid, Toledo, Segovia, Granada, Córdoba, and Seville he settled in Paris where fellow Argentine artists Horacio Butler, Aquiles Badi, Alfredo Bigatti, Xul Solar, Héctor Basaldua, and Lino Enea Spilimbergo were working. He attended “City of Lights” workshops given by André Lhote and Othon Friesz at Académie de la Grande Chaumière. Berni painted two landscapes of Arcueil, Paisaje de París (Landscape of Paris), Mantel amarillo (The Yellow Tablecloth), La casa del crimen (The House of Crime), Desnudo (Nude), and Naturaleza muerta con guitarra (Still Life with Guitar).

He went back to Rosario for a few months but returned to Paris in 1927 with a grant from the Province of Santa Fe. Studying the work of Giorgio de Chirico and René Magritte, Berni became interested in surrealism and called it “a new vision of art and the world, the current that represents an entire youth, their mood, and their internal situation after the end of the World War. A dynamic and truly representative movement.” His late 1920s and early 1930s surrealist works include La Torre Eiffel en la Pampa (The Eiffel Tower in Pampa), La siesta y su sueño (The Nap and its Dream), and La muerte acecha en cada esquina (Death Lurks Around Every Corner).

He also began studying revolutionary politics including the Marxist theory of Henri Lefebvre, who introduced him to the Communist poet Louis Aragon in 1928. Berni continued corresponding with Aragon after leaving France, later recalling, “It is a pity that I have lost, among the many things I have lost, the letters that I received from Aragon all the way from France; if I had them today, I think, they would be magnificent documents; because in that correspondence we discussed topics such as the direct relationship between politics and culture, the responsibilities of the artist and the intellectual society, the problems of culture in colonial countries, the issue of freedom.”

Several groups of Asian minorities lived in Paris and Berni helped distribute Asian newspapers and magazines, to which he contributed illustrations.

Nuevo Realismo In 1931 Berni returned to Rosario where he briefly lived on a farm and was then hired as a municipal employee. The Argentina of the 1930s was very different from the Paris of the 1920s. He witnessed labor demonstrations and the miserable effects of unemployment[5] and was shocked by the news of a military coup d’état in Buenos Aires (see Infamous Decade). Surrealism didn’t convey the frustration or hopelessness of the Argentine people. Berni organized Mutualidad de Estudiantes y Artistas and became a member of the local Communist party.

Berni met Mexican artist David Alfaro Siqueiros who had been painting large-scale political murals on public buildings and was visiting Argentina to give lectures and exhibit his work in an effort to “summon artists to participate in the development of a proletarian art.” In 1933 Berni, Siqueiros, Spilimbergo, Juan Carlos Castagnino and Enrique Lázaro created the mural Ejercicio Plástico (Plastic Exercise). But ultimately Berni didn’t think the murals could inspire social change and even implied a connection between Siqueiro’s artwork and the privileged classes of Argentina, saying, “Mural painting is only one of the many forms of popular artistic expression…for his mural painting, Siqueros was obliged to seize on the first board offered to him by the bourgeoisie.”

Instead he began painting realistic images that depicted the struggles and tensions of the Argentine people. His popular Nuevo Realismo paintings include Desocupados (The Unemployed) and Manifestación (Manifestation). Both were based on photographs Berni had gathered to document, as graphically as possible, the “abysmal conditions of his subjects.” As one critic noted, “the quality of his work resides in the precise balance that he attained between narrative painting with strong social content and aesthetic originality.”

Since the late 1960s various Argentine musicians have written and recorded Juanito Laguna songs. Mercedes Sosa recorded the songs Juanito Laguna remonta un barrilete (on her 1967 album Para cantarle a mi gente) and La navidad de Juanito Laguna (on her 1970 album Navidad con Mercedes Sosa). In 2005 a compilation CD commemorating Berni’s 100th birthday included songs by César Isella, Marcelo San Juan, Dúo Salteño, Eduardo Falú, and Las Voces Blancas, as well as two short recordings of Berni speaking in interviews.

Several Argentine government organizations also celebrated Berni’s centennial in 2005, including the Ministerio de Educación, Ciencia y Tecnología de la Nación, and Secretaría de Turismo de la Nación. Berni’s daughter Lily curated an art show entitled Un cuadro para Juanito, 40 años después (A painting for Juanito, 40 years later). Through the organization De Todos Para Todos (By All For All) children across Argentina studied Berni’s art then created their own using his collage techniques.

In July 2008 thieves disguised as police officers stole fifteen Berni paintings that were being transported from a suburb to the Bellas Artes National Museum. Culture Secretary Jose Nun described the paintings as being “of great national value” and described the robbery as “an enormous loss to Argentine culture.”

In a 1936 interview Berni said that the decline of art was indicative of the division between the artist and the public and that social realism stimulated a mirror of the surrounding spiritual, social, political, and economic realities.

In 1941, at the request of the Comisión Nacional de Cultura, Berni traveled to Bolivia, Ecuador, Peru and Colombia to study pre-Columbian art. His painting Mercado indígena (Indian Market) is based on the photos he took during this trip.

Two years later he was awarded an Honorary Grand Prix at the Salón Nacional and co-founded a mural workshop with fellow artists Spilimbergo, Juan Carlos Castagnino, Demetrio Urruchúa, and Manuel Colmeiro. The artists decorated the dome of the Galerías Pacifico.

The 1940s saw various revolutions and coups d’état in Latin America including the ousting of Argentine President Ramón Castillo in 1943. Berni responded with more political paintings including Masacre (Massacre) and El Obrero Muerto (The Dead Worker).

From 1951 to 1953 Berni lived in Santiago del Estero, a province in northwestern Argentina. The province was suffering massive ecological damage including the exploitation of quebracho trees. While in Santiago del Estero he painted the series “Motivos santiagueños” and “Chaco,” which were later exhibited in Paris, Berlin, Warsaw, Bucharest and Moscow.

In the 1950s he returned to expressionism with works like Los hacheros (Axemen) and La comida (Food),[3] and began a series of suburban landscapes including Villa Piolín (Villa Tweety), La casa del sastre (House of Taylor), La iglesia (The Church), El tanque blanco (White Tank), La calle (Street), La res (The Answer), Carnicería (Carnage), La luna y su eco (The Moon and its Echo), and Mañana helada en el páramo desierto (Morning Frost on the Moor). He also painted Negro y blanco (Black and White), Utensilios de cocina sobre un muro celeste (Cookware on a Blue Wall), and El caballito (The Pony).

Berni’s post-1950s work can be viewed as “a synthesis of Pop Art and Social realism.” In 1958 he began collecting and collaging discarded material to create a series of works featuring a character named Juanito Laguna. The series became a social narrative on industrialization and poverty and pointed out the extreme disparities existing between the wealthy Argentine aristocracy and the “Juanitos” of the slums.

As he explained in a 1967 Le Monde interview, “One cold, cloudy night, while passing through the miserable city of Juanito, a radical change in my vision of reality and its interpretation occurred…I had just discovered, in the unpaved streets and on the waste ground, scattered discarded materials, which made up the authentic surroundings of Juanito Laguna – old wood, empty bottles, iron, cardboard boxes, metal sheets etc., which were the materials used for constructing shacks in towns such as this, sunk in poverty.”

Latin American art expert Mari Carmen Ramirez has described the Juanito works as an attempt to “seek out and record the typical living truth of underdeveloped countries and to bear witness to the terrible fruits of neocolonialism, with its resulting poverty and economic backwardness and their effect on populations driven by a fierce desire for progress, jobs, and the inclination to fight.”

Notable Juanito works include Retrato de Juanito Laguna (Portrait of Juanito Laguna), El mundo prometido a Juanito (The World Promised to Juanito), and Juanito va a la ciudad (Juanito Goes to the City). Art featuring Juanito (and Ramona Montiel, a similar female character) won Berni the Grand Prix for Printmaking at the Venice Biennale in 1962.

In 1965 a retrospective of Berni’s work was organized at the Instituto Di Tella, including the collage Monsters. Versions of the exhibit were shown in the United States, Argentina, and several Latin American countries. Compositions such as Ramona en la caverna (Ramona in the Cavern), El mundo de Ramona (Ramona’s World), and La masacre de los inocentes (Massacre of the Innocent) were becoming more complex. The latter was exhibited in 1971 at the Paris Museum of Modern Art. By the late 1970s Berni’s Juanito and Ramona oil paintings had evolved into three-dimensional altar pieces.

After a March 1976 coup Berni moved to New York City where he continued painting, engraving, collaging, and exhibiting. New York struck him as luxurious, consumerist, materially wealthy, and spiritually poor. He conveyed these observations in subsequent work with a touch of social irony. His New York paintings display a great protagonism of color and include Aeropuerto (Airport), Los Hippies, Calles de Nueva York (Streets of New York), Almuerzo (Lunch), Chelsea Hotel, and Promesa de castidad (Promise of Chastity). He also produced several decorative panels, scenographic sketches, illustrations, and collaborations for books.

Berni’s work gradually became more spiritual and reflective. In 1980 he completed the paintings Apocalipsis (Apocalypse) and La crucifixion (The Crucifixion) for the Chapel of San Luis Gonzaga in Las Heras, where they were installed the following year.

Antonio Berni died on October 13, 1981 in Buenos Aires where he had been working on a Martin Fierro monument. The monument was inaugurated in San Martin on November 17 of the same year. In an interview shortly before his death he said, “Art is a response to life. To be an artist is to undertake a risky way to live, to adopt one of the greatest forms of liberty, to make no compromise. Painting is a form of love, of transmitting the years in art.”

Since the late 1960s various Argentine musicians have written and recorded Juanito Laguna songs. Mercedes Sosa recorded the songs Juanito Laguna remonta un barrilete (on her 1967 album Para cantarle a mi gente) and La navidad de Juanito Laguna (on her 1970 album Navidad con Mercedes Sosa). In 2005 a compilation CD commemorating Berni’s 100th birthday included songs by César Isella, Marcelo San Juan, Dúo Salteño, Eduardo Falú, and Las Voces Blancas, as well as two short recordings of Berni speaking in interviews.

Several Argentine government organizations also celebrated Berni’s centennial in 2005, including the Ministerio de Educación, Ciencia y Tecnología de la Nación, and Secretaría de Turismo de la Nación. Berni’s daughter Lily curated an art show entitled Un cuadro para Juanito, 40 años después (A painting for Juanito, 40 years later). Through the organization De Todos Para Todos (By All For All) children across Argentina studied Berni’s art then created their own using his collage techniques.

In July 2008 thieves disguised as police officers stole fifteen Berni paintings that were being transported from a suburb to the Bellas Artes National Museum. Culture Secretary Jose Nun described the paintings as being “of great national value” and described the robbery as “an enormous loss to Argentine culture.”

Antonio Berni was originally published on HiSoUR Art Collection

1 note

·

View note