#USFWS Pacific Region

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Arroyo Toad (Anaxyrus californicus), family Bufonidae, southern California, USA

ENDANGERED.

photograph via: USFWS Pacific Southwest Region

357 notes

·

View notes

Text

The species assignments for my Temeraire daemon AU!

[Image ID: a 2x 3 gride with green edges. It lists the names of six characters, with their daemon's names and species, and a photograph of those species next to them. They are as follows:

John Granby - Winail - Black-backed woodpecker Tenzing Tharkay - Japatyu - Bearded Vulture Jane Roland - Archibald - European Badger Catherine Harcourt - Phenel - Mason Bee Matthew Berkley - Jux - Common Toad Augustine Little - Borough - European Grey Squirrel. /end ID]

Full list of the image sources below the cut!

Black-backed woodpecker by USFWS Pacific Southwest Region Bearded Vulture by fveronesi1 European Badger by caroline legg Mason Bee by Julie Common Toad by Anne Burgess European Grey Squirrel by Brian Forsythe

Thank you to the photographers!

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

I heard this song and blacked out because it is such a TexaCali breakup song. (The other TexaCali breakup song is "We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together." I said what I said.)

Photo Credits under the cut.

Top row from left to right:

Diliff, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

"Native flora" by USFWS Pacific Southwest Region is marked with Public Domain Mark 1.0.

"Backpack People" by Chad Madden is marked with CC0 1.0.

Middle row from left to right:

Ronny Jacques fonds. Library and Archives Canada, e010980790

Harper, W. D, photographer. Two of a Kind. Texas, ca. 1904. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2003690414/.

Bottom row from left to right:

"USA Cowboy" by arnaudmatar is marked with CC0 1.0.

"Texas Bluebonnet" by Kaptured by Kala is marked with CC0 1.0.

Leaflet, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

In November, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) published a plan to cull nearly half a million barred owls across the lush old-growth forests of the Pacific Northwest and California.

But by killing these owls, the agency is hoping to save owls—albeit a different species of the bird. Officials plan to remove a portion of the abundant barred owl population over a three-decade span to clear up space and resources for the threatened northern spotted owl, of which only around 4,000 remain on federal lands. Native to the region, spotted owls have faced a number of threats in the past few decades, including forest loss due to logging and competition with the barred owl, which has been more successful at hunting and adapting to a variety of territories than its vulnerable avian cousin.

Scientists are still not certain how or where the barred owls came from, but research shows that they began to expand their range westward concurrently with European settlement and as human-caused changes altered habitats in the Great Plains and northern boreal forest. As a result, many say the barred owls are an invasive species and must be removed to protect native species, reports NPR.

However, the USFWS culling plan has triggered a spate of backlash since it was announced; just last week dozens of wildlife organizations published a letter condemning this effort and arguing that it “betrays a willful failure to anticipate the wide range of adverse consequences such a plan will invariably unspool.”

The plan has also resurfaced a longstanding debate over what makes a species “invasive,” and how nonnative plants and animals should be treated within an ecosystem. Today, I am diving into the details of the invasive debate, and how it could affect wildlife management moving forward.

What’s in a Name? The author Charles Elton was the first to use the term “invasion” to describe foreign plants and wildlife in his 1958 book “The Ecology of Invasions by Animals and Plants,” reports The New York Times.

Scientists have identified countless nonnative invasive species across the U.S.—from cane toads in Florida to fingernail-sized zebra mussels in the Great Lakes. In most cases, these species are introduced by humans who may accidentally carry them over on transit or intentionally release them. While many nonnative species are relatively harmless to an ecosystem, others can have catastrophic consequences; for example, feral pigs have destroyed crops and spread disease across at least 35 states in the U.S., according to the USDA.

...

“The words we use determine what courses of action are deemed acceptable and appropriate,” Bliss told me over email. “When we call something invasive, we may show less regard for their welfare.”

Bliss pointed to certain inhumane methods to kill nonnative species such as traps once used in the Netherlands to kill muskrats by holding them underwater until they drown. Other researchers have also questioned the term “invasive.”

“It’s not that it can’t be descriptively true at times, there can be nonnative species moving into an area, causing damage, which is emblematic of the meaning of invasion,” William Lynn, a researcher at Clark University in Massachusetts who studies animal and sustainability ethics, told me over the phone. “But to label species ‘invasive’ simply because they’re nonnative or they’re immigrant species, or to blindly bandy about the term ‘invasive’ species when it’s not clear that that’s what’s going on, is the problem.”

The Owl Conundrum: The northern spotted owl is listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act, meaning that the USFWS is legally required to protect it. This led the government to enact rules limiting the area that timber companies could log, sparking backlash from industry and residents in the region for its economic impacts.

Now, the Service has deemed this cull a necessity in following through with this obligation.

...

The U.S. government has performed a barred owl culling experiment before, but at a much smaller scale than the new USFWS project. Over a decade ago, a team of researchers led by the U.S. Geological Survey killed more than 2,400 barred owls, and found that their efforts helped temporarily stabilize spotted owl populations over the next five years, according to a 2021 study.

At that time, Lynn was a member of the government’s “Barred Owl Stakeholder Group,” which performed an ethics review before the project took place.

Despite the groups’ “deep discomfort with killing barred owls,” they deemed it necessary to cull several thousand barred owls in order to save the spotted owl species, Lynn said. Overall, though, he said that the experiment “failed” because while it slowed the decline of the spotted owl, it did not act as a long-term solution.

“It’s a very different situation now,” said Lynn, adding that he does not think this new cull will save the spotted owl.

#enviromentalism#ecology#us fish and wildlife service#wildlife services#BS Culling#owls#pacific northwest#california#barred owl#spotted owl#endangered species#Non-native species#Turns out killing you way out of a problem doesn't really work

0 notes

Text

last week the North American wolverine in the contiguous United States finally received federal protection under the Endangered Species Act! you can read the full press release from the USFWS, but here's a quick quote:

“Current and increasing impacts of climate change and associated habitat degradation and fragmentation are imperiling the North American wolverine,” said Pacific Regional Director Hugh Morrison. “Based on the best available science, this listing determination will help to stem the long-term impact and enhance the viability of wolverines in the contiguous United States.”

Wolverine (Gulo gulo)

470 notes

·

View notes

Text

Birding: How to get started and make it count for conservation

By: Rylan Suehisa - Public Affairs Officer with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service based out of Portland, OR

Spring migration continues to roll along as upwards of 3 billion birds make their way north toward their summertime breeding grounds. Wave after wave sweeps through the Pacific Northwest, giving us all a calming seasonal spectacle that brings with it a bit of normalcy during these uncertain times. And if you’ve been following along with our #MigrationMondays content, we hope that you’ve been enjoying paying closer attention to this incredible spring migration event as it happens in real time.

Maybe you’ve already taken that next step in helping birds along the way by planting native plants and avoiding harmful pesticides, or begun building birdhouses for birds that will spend the summer in your yard. If you are seeing positive results from your efforts, congratulations - we are stoked!

Here’s another thing you can do to help birds along their way - simply take time out of your day to watch birds and take note of your observations. In addition to the benefit to your well-being that this “pause” from the world provides, birdwatching benefits birds too. By noting what you see and submitting those observations to a database such as eBird, you are expanding our knowledge about where birds go, how they get there and what they need along the way.

Birding 101

“Hold on,” you might be saying. Maybe you are new to birding and wondering how to get started. Perhaps you’ve been an appreciator of birds for a while, but are uncertain about how to take the next step into birding as an activity. Below is an infographic that we hope you will find useful as you get started.

For more on the subject from a Service bird biologist and certified “Bird Nerd,” check out this piece written back when we were celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, a landmark agreement that laid the foundation for bird conservation as we know it today.

Why It Matters

As you begin to bird and get more comfortable with the activity, your observations will make a difference. By noting what types, how many and where you are seeing birds and submitting that data to a database such as eBird, you are contributing to a remarkable global knowledge-base. Here’s what the eBird team has to say about how your and thousands of other birders’ observations make a difference for birds:

eBird transforms a global birding community’s passion for birds into critical data for research, conservation, and education. Half a billion bird observations have been contributed so far. When combined and analyzed appropriately, these data enable next generation species distribution models that provide full life cycle information about birds at relatively fine scales across broad spatial and temporal extents. These model results inform novel conservation actions, from site-specific information about the occurrence and abundance of birds, to looking at patterns of species abundance across continent-spanning flyways.

Answers to large-scale questions such as “Where do birds go and how far do they travel?” to specific ones like “where do birds stop along the way so we can prioritize conservation of those locations?” come from citizen science data that you and many others submit. Indeed, the data you collect about birds you count from your yard, local park or National Wildlife Refuge goes a long way towards their conservation.

Now that you know more about this hobby and its impact, we hope you feel more comfortable taking the next step towards discovering an exciting way of experiencing nature. With that, we wish you happy birding!

#USFWS#USFWS Pacific Region#migration#spring migration#birds#birding#nature#science#MigrationMondays

548 notes

·

View notes

Video

Hermit crab by USFWS - Pacific Region Via Flickr: Photo Credit: USFWS / Andrew S. Wright About halfway between Hawai‘i and American Samoa lies Palmyra Atoll - a circular string of about 26 islets nestled among several lagoons and encircled by 15,000 acres of coral reefs.

#USFWS#USFWS Pacific Region#U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service#United States Fish and Wildlife Service#Palmyra Atoll NWR#Plants#Palmyra#Palmyra Atoll#Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument#Restoration#Forest#ocean#Seabirds#Crab

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Response to an excerpt I shared from this article which was originally published in October 2019:

Another response, same commenter:

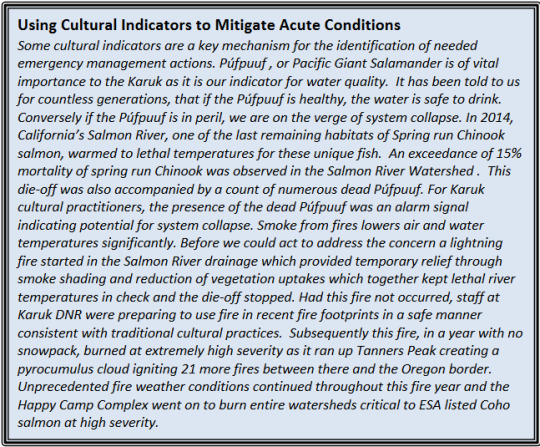

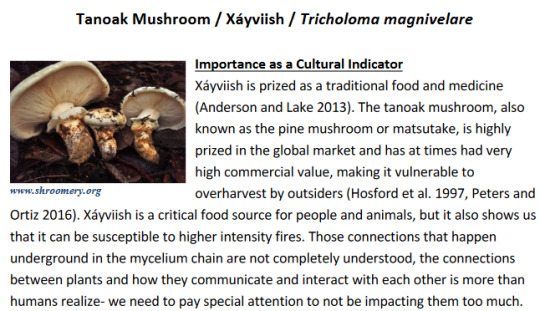

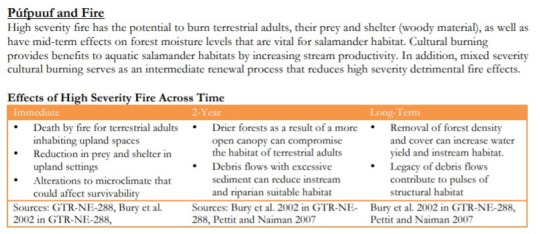

Gonna extend the benefit of a very generous doubt and respond in good faith. All due respect: this isn’t “bait” and this isn’t “just a timely attempt to capitalize on wildfire season on the Pacific coast”. The Karuk Department of Natural Resources (along with this author, Kari Norgaard) have written extensively about fires, the Klamath-Siskiyou ecoregion, and oak woodland, for years.

Two important Indigenous ecologists with knowledge of Klamath fires and landscapes: Bill Tripp (deputy directory of Karuk Department of Natural Resources) and Frank Lake. The Karuk tribe organizes what might be the most high-profile prescribed burning projects in the US. They work with the Cultural Fire Management Council, nearby tribes including the Yurok, and UC-Berkeley. The US Forest Service and California Department of Forestry have given a significant amount of formal authority and autonomy to Kaurk communities to lead forest/woodland management in the Six Rivers and Klamath regions. (Not that Indigenous knowledge has to be substantiated by those institutions in order to be recognized as both legitimate and materially effective.)

I highly recommend checking out the Karuk Climate Adaptation Plan (2019). In my opinion, providing sophisticated understanding of fire, and also one of the most interesting written presentations of ecological knowledge of North America. (The lead authors: Norgaard and Tripp.) Over 200 pages of extra-ordinary ecological knowledge.

Some excerpts:

Norgaard has also previously written about this:

1 - Contemporary ecologists and environmental historians, even those working for state and settler-colonial agencies in the 21st century, would (probably?) tell you with no reservations that prescribed burning is fundamental to North American ecology, and has been for millennia. Prescribed burning isn’t “just a thing Natives do” and data/writing/advocacy in support of prescribed burning isn’t a superficial and unsubtantiated “shout-out” to Indigenous land management; in the past 40 years, prescribed burning and selective management of smaller fires is the preferred settler-colonial method of management, too, practiced now by the FS and USFWS.

2 - Pacific coast oak savanna and oak woodlands, in particular, are sensitive to drying and soil death exacerbated by increased heat (for many reasons). And actually, the US federal government’s mismanagement of Klamath-Siskiyou ecoregion riparian corridors and oak savanna is one of the most clear and blatant examples of academic/institutional misunderstanding of ecology on the continent. When the State of California and US federal government took over the region’s management, they promoted growth/expansion of conifer trees because A) conifer forest looks green and pretty and lush, compared to the brown-colored less-dense woodlands of oak, making conifer forest appear more “attractive” than oak woodland. And because B) conifer trees were/are more valuable to timber industry and other resource extraction schemes facilitated by settler-colonial/imperial projects. By promoting conifer growth, rather than naturally-occurring and fire-adapted oak, the entire food web and ecosystem balance was interrupted and partially destroyed by US institutions. Karuk people, in contrast, understood that the riparian corridors needed oak woodlands to be propagated. (See: “Sometimes ... things that are aesthetically pleasing ... are worse.”)

3 - This article isn’t a “topical” one-time shout-out to Indigenous people to “score woke points.” Norgaard is a white academic, yes, but she’s spent years working with the Karuk Department of Natural Resources and she’s relaying the information explicitly shared with her by Karuk ecologists.

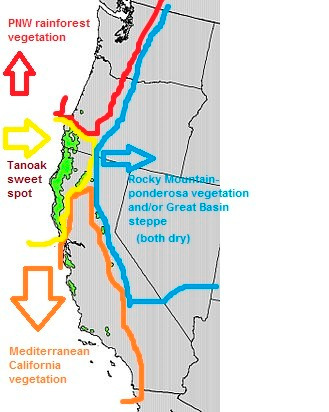

Also, if concerned about “annual fires burning down a quarter of the state,” I’d point out that not all of the landscapes within the political borders of “California” are comparable, and I’d encourage making a distinction between the Klamath-Siskiyou region (Klamath, Rogue River, Shasta area, Six Rivers, tanoak region, etc.) and Mediterranean California (Central Valley, central coast, So-Cal, western Sierra Nevada slopes). Two different ecologies. Fire behavior in Klamath-Siskiyou region and in Central Valley are different.

(Bad maps I made. Karuk land and Six Rivers oak/riparian woodlands located in the “tanoak sweet spot”.)

Regarding the accusation that Indigenous people “drove Pleistocene megafauna to extinction”: that’s an entire other Pandora’s box that I won’t really address, but both North American environmental history and global Pleistocene-Holocene extinction are special interests of mine, and there are so many factors influencing the Late Pleistocene extinction process that the debate won’t be resolved here, or soon. But it’s worth pointing out that, hypothetically, environmental degradation in places like Amazonia, the Asiatic Steppes, the Sahel, and the Near East might strongly, dramatically, rapidly lead to ecosystem collapse on opposite corners of the planet. Meaning that domestication or agriculture or mammoth-hunting in Central Asia, or subsequent explosive marine algae blooms, or self-reinforcing global rapid climate shift in response to localized regional devegetation of the Near East may have provoked unstoppable megafaunal extinction in North America. (I also invite you to search terms like Klamath, California, oak, Karuk, savanna, megafauna, and Pleistocene on my blog.)

Some other resources on the region.

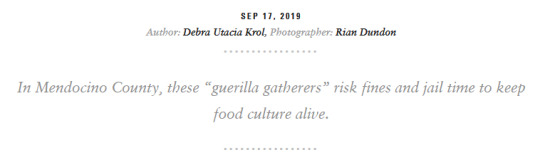

From late 2019, published at Roads and Kingdoms, more on Indigenous dispossession in the Klamath region:

From 2018, published at PS Magazine, more on Karuk prescribed burning:

From 2016, published at Bay Nature, more on prescribed burns in Northern California:

#my writing i guess#ecologies#indigenous#indigenous pedagogies#black methodologies#geographic imaginaries#tidalectics#multispecies#interspecies

318 notes

·

View notes

Link

I watched a little bit of this. Obviously, what you see depends on the time of day and the activity in the nesting site. One chick. Worth a gamble to peek.

youtube

Description from US Fish & Wildlife Service/Pacific Region:

This condor nest, known as the Huttons Bowl nest, is located in a remote canyon near the Hopper Mountain National Wildlife Refuge. This season features ten-year-old female #594 and fifteen-year-old male #374, a newly established pair who have been tending to their single chick #1075 that hatched on April 10.

Female condor #594 previously paired with male condor #462 in 2018 and 2020, successfully fledging one chick each year. Her previous mate is still alive and tending to their fledgling from last year. Male condor #374 is an experienced parent with six nesting attempts under his belt. He has successfully fledged four chicks in previous years—three of which are still alive today. Unfortunately, his previous mate was lost over the past year before pairing up with #594.

The Huttons Bowl nest site was last featured on the California Condor cam in 2018 when male #374 and his former mate successfully raised their chick (#923) to fledge.

Here’s a still shot of the chick:

Credit: Joseph Brandt/USFWS

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bobcat by Pacific Southwest Region USFWS from Sacramento, US

"We have a lot of cover, a small pond and lots of rabbits. We have at least one family of Bobcats and I am expecting to see their kittens soon. They are used to people, but I use a 500 mm lens so as not to interfere with their normal activities." -- Mark Stewart

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Officials Say Invasive Zebra Mussels Are Hiding in Aquarium Decor Sold Across U.S.

https://sciencespies.com/news/officials-say-invasive-zebra-mussels-are-hiding-in-aquarium-decor-sold-across-u-s/

Officials Say Invasive Zebra Mussels Are Hiding in Aquarium Decor Sold Across U.S.

Federal officials in the United States warn that invasive zebra mussels have been discovered lurking in shipments of moss balls sold as aquarium accessories in pet shops across the country, according to a statement from the United States Geological Survey (USGS). The statement says the invasive freshwater bivalves, which are native to Eurasia, have been found in pet shops in at least 21 states.

The Conservation Officer Service in British Columbia, Canada, has also reported finding zebra mussels in pet shops after conducting searches at some 600 locations, reports David Carrigg of the Vancouver Sun.

Zebra mussels are tiny, about the size of a fingernail, but they can be incredibly destructive. According to USFWS, when these small, stripey mollusks “become established in an environment, they alter food webs and change water chemistry, harming native fish plants and other aquatic life. They clog pipelines used for water filtration, render beaches unusable, and damage boats.”

Zebra mussels can quickly establish themselves and multiply if they are introduced to a water source, even if they are flushed down a toilet. In the Great Lakes region, for example, dealing with invasive Zebra and quagga mussels costs hundreds of millions of dollars every year, reports the Associated Press.

USGS officials tell the Detroit News‘ Mark Hicks that all moss balls should be treated as though they contain zebra mussels and destroyed before being properly disposed of in a sealed container in the trash. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) recommends destroying the hardy mussels by freezing, boiling or bleaching any moss ball or other item suspected of containing the invasive species.

The first sighting of zebra mussels in the moss balls was reported by a PetCo employee in Seattle, Washington, on February 25, according to the AP. After notifying local officials, USGS fisheries biologist Wesley Daniel took a trip to a pet store in Florida only to discover a zebra mussel in a moss ball there too, suggesting the issue was widespread. Since then, reports have come in from Alaska, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Iowa, Massachusetts, Michigan, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, Wisconsin, Washington and Wyoming, per USGS.

In a statement emailed to Newsweek‘s Jason Murdock, a Petco spokesperson says the company has “immediately paused the sale of all Marimo aquarium moss balls at Petco locations and on petco.com.”

The geographic extent of the moss balls, specifically “Betta Buddy” branded marimo balls, has experts concerned the incident could spread the mussels to new areas.

“This is one of the most alarming things I’ve been involved with in over a decade of working with invasive species,” Justin Bush, executive coordinator for the Washington Invasive Species Council, tells local broadcast network KING 5.

A bit farther south, Rick Boatner, the invasive species wildlife integrity supervisor at the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, tells Bradley W. Parks of Oregon Public Broadcasting (OPB) that a zebra mussel infestation “would be devastating to our environment if these ever got established in Oregon or the Pacific Northwest.”

Per OPB, the Pacific Northwest has been able to mostly keep zebra mussels at bay through strict monitoring of boats and other craft, which are one of the primary vectors for introducing the mussels to new waters.

However, Boatner admits to OPB, his agency was “not expecting zebra mussels from moss balls.”

#News

#03-2021 Science News#2021 Science News#Earth Environment#earth science#Environment and Nature#Nature Science#News Science Spies#Our Nature#outrageous acts of science#planetary science#Science#Science Channel#science documentary#Science News#Science Spies#Science Spies News#Space Physics & Nature#Space Science#News

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Hermit crabs at Baker Island (via USFWS - Pacific Region)

Photo by USFWS / Dana Schot

Baker Island National Wildlife Refuge, part of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument, is a tiny ancient atoll that supports a diverse community of marine organisms including seabirds, marine mammals, turtles, fish, plants, corals, and other invertebrates.

Nesting and foraging seabirds dominate the landscape and seascape while sheer isolation and solitude help us see our place in the natural world.

The Pacific Remote Islands National Marine Monument is one of the largest marine conservation areas in the world and protects over 400,000 square miles and seven national wildlife refuges on coral islands, reefs, and atolls.

#Strawberry Hermit Crab#Coenobita perlatus#Coenobita#Coenobitidae#Paguroidea#Anomura#Decapoda#Malacostraca#Crustacea#crustacean#hermit crab#wildlife refuge#Baker Island National Wildlife Refuge#Baker Island NWR#Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pronghorn Portrait by Photo credit: Doug Dance

(Via USFWS - Pacific Region)

71 notes

·

View notes

Note

Would you be able to point me in the direction of other blogs similar to yours? Perhaps about forests as well as oceans?

Yes! Several other public land and water management agencies are here on Tumblr. In no particular order:

@usfws: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

@usfwspacific: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Pacific Region

@usfwspacificsouthwest: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Pacific Southwest Region

@americasgreatoutdoors: U.S. Department of the Interior

@mypubliclands: Bureau of Land Management

@mountrainiernps: Mount Rainier National Park

@glaciernps: Glacier National Park

@npsparkclp: National Park Service’s Park Cultural Landscapes Program

@usgsbiml: U.S. Geological Survey’s Native Bee Lab

Fellow public agencies, who are we missing?

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tweeted

For whatever we lose(like a you or a me) it's always ourselves we find in the sea —E. E. Cummings Stuck inside during #NationalWildlifeRefugeWeek? Nbd, just take a virtual dive into the magical waters of Palmyra Atoll NWR, and thank us later ;) https://t.co/vCDlHWE2ge. pic.twitter.com/3zkc2ReYld

— USFWS Pacific Region (@USFWSPacific) October 16, 2019

1 note

·

View note

Text

#MigrationMondays: How You Can Help Birds On Their Way This Spring

By: Rylan Suehisa - Public Affairs Officer with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service based in Portland, Oregon

In the morning when you wake up during this time of Quarantine, what’s the first thing you hear? If it’s not a family member or roommate bugging you to “Get out of bed already!” - (I’ll raise my hand to that), chances are you’re greeted by a chorus of bird song.

As the current pandemic has many of us sheltering in place, we are experiencing nature more acutely. Instead of turning on the TV for morning commute traffic updates, we can take an extra minute or two to focus in on the birdsong coming in through the window, or note a flurry of actively-foraging birds in a nearby Douglas Fir tree. With current circumstances the way they are, we have more time to appreciate the little things.

Yet behind these much-needed moments of zen lies an incredible phenomenon - spring migration. With more than three billion birds heading north throughout North America creating a beautiful seasonal spectacle, migration is something to get pumped about.

Western tanager, credit: Peter Pearsall/USFWS

We’ve just celebrated World Migratory Bird day (WMBD), where a whole flock of bird lovers from around the globe gathered together in collective awe and appreciation of birds’ incredible springtime journeys. Showcasing the inter-connectivity of bird conservation through many virtual events around the world, WMBD participants stirred up a gust of momentum that has us thinking about the remaining duration of spring migration. How can we do our part throughout May into early June?

With much of the world under lockdown, these action items should follow guidelines set forth by your local and national leaders. Here in the Pacific Northwest, that means sticking close to home for now. So from your garden, to your porch, to the grocery store, join us in the coming weeks as we explore some of the ways we can help birds along their journeys.

Let’s get started! First up…

Make informed choices about the plants in your garden.

Black-capped chickadee with insect at William L. Finley NWR. Credit: George Gentry/USFWS

It’s hard to imagine that a tiny nickel-sized bird such as a Wilson’s Warbler travels 2,000 miles or more on its way from wintering in Mexico to northern nesting grounds each year, or that migrating songbirds such as western tanagers, vireos and flycatchers expend up to half their body weight to make their own journeys north. Given these circumstances, it’s not so difficult to grasp a songbird’s need for breaks along the way. Once they’ve landed they need to refuel their tiny bodies to recover and complete the rest of their journey.

These waves of small yet determined travelers often fan out across wild spaces, but also urban areas, voraciously eating any small insect they can find. Yet depending on what’s growing in your garden, a songbird might land to discover a bountiful buffet waiting, or nothing more than a colorful but empty picnic table. A couple keys to meeting the stopover needs of a bird on migration are planting native vegetation and eliminating all use of pesticides, especially those known as neonicotinoids, from your yard.

Native plants provide critical supplies of pollen and nectar for a host of pollinating species including caterpillars - delicacies that many spring migrants love! Non-native plants may have the vivid colors and more showy flowers, but some do not provide nectar nor pollen and research shows that native pollinators generally visit more native flowering plants. Birds in turn visit these same plants in search of the abundant insects found among their leaves. Native plants also have many advantages since they are accustomed to the local climate and native soils, and once established they need minimal care.

As you head over to your local nursery in search of native plants, inquire about that establishment’s use of neonicotinoids, one of the most prevalent pesticides around the world today. “Neonics,” as they are called, are highly toxic to pollinators such as butterflies and bees, but also toxic to birds that eat the dosed insects. A growing number of nurseries are specifying where these pesticides are in use among their offerings so you can be sure that the native plants you purchase will actually bring the insects and birds you’re hoping for.

For more information on neonicotinoids, hear from Regional Refuge Biologist Joe Engler.

For strategies to incorporate native plants into your garden, check out this piece from Regional Bird Biologist David Leal.

Next week, we’ll look into building birdhouses for resident songbirds that will be singing and raising young throughout the summer. Stay tuned!

#USFWS#USFWS Pacific Region#birds#birding#garden#plants#gardening#spring#springtime#ideas#inspiration#quarantine

5 notes

·

View notes