#Triumph of Saint Thomas Aquinas

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Benozzo Gozzoli - Triumph of Saint Thomas Aquinas. 1470 - 1475

423 notes

·

View notes

Text

“With its private property, exploitation of man by man, economic and spiritual enslavement of man, the capitalist system has imposed a heavy burden on everyone, but especially and more barbarously on women. Women were the first slaves in human history, even before slavery. Throughout this history, not to mention prehistory, whether during the Hellenic civilization, Roman times, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, or in modern times, whether in the contemporary bourgeois era of the so-called “refined civilization,” women have been and are becoming the most enslaved, oppressed, exploited and humiliated people in every respect. Laws, traditions, religion, masculine mentality oppressed them and allowed them to be oppressed. Ecclesiastes says; “I find woman more harmful than death,” while St. John Chrysostom has another opinion about women. He says; “Among the wildest animals, you will not find anyone more decadent than a woman”. The theologian and philosopher Saint Thomas Aquinas, one of the most prominent philosophers of medieval reaction, defended the view that “woman's destiny is to live under the heel of men”. To complete these barbaric quotes, Napoleon said; “nature has made women our slaves”. Such were the views of the church and the bourgeoisie about women. Among the bourgeoisie, these views remain valid today. There are countless of philosophers and writers in Europe and all over the world who have made the superiority of men over women a mythological aspiration, norm and even demand. According to them, a man is strong, a warrior, brave and therefore smarter, therefore he is predetermined to rule, to lead, whereas a woman is by nature weak, vulnerable and timid, therefore she must be ruled and handled. Bourgeois theorists such as Nietzsche and Freud also defend the theory that man is active and woman is passive in the same way. This reactionary, anti-scientific theory has led to nazism in politics and sadism in sexology. Our mothers, grandmothers and great-grandmothers suffered under this terrible slavery, they carried these physical and spiritual cruelties on their own backs. Now, when the revolution has triumphed, when socialism has been successfully built in our country, the Party sets before us as a great task, as one of the greatest tasks, the complete and final liberation of women from all the shackles of the painful past, the complete liberation of Albanian women. Marxism teaches us that the participation of women in production and their liberation from capitalist exploitation are the two stages of women's liberation. Our Party, which follows the principles of Marxism-Leninism and applies them faithfully, has liberated the people and especially women from capitalist exploitation through war and revolution and has included them in production.”

— Enver Hoxha, Selected Works, 4, p. 268

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

...What is the proper response of faithful Christians to the sufferings of those who spend eternity in hell, especially if some of its occupants are revealed on the day of judgment to be friends or family members? It most certainly can be said that the righteous do not rejoice directly in the sufferings of the damned! However, those who love God rejoice in God’s just condemnation of evil. After all, if God is Good and loves that which is good, He must hate evil, as should His followers.

This is why Sacred Scripture refers to the smoke of the torment of those who rebel against God as ascending before the angels, and the righteous in heaven rejoicing over God’s just judgment (see Rev. 14:9-11, 18:20, 19:3). The righteous do not rejoice in the condemnation of the wicked as such, but in the condemnation of the wickedness that evil people committed. Saint Thomas Aquinas confirms this distinction: "A thing may be a matter of rejoicing in two ways. First, directly, when one rejoices in a thing as such: and thus the saints will not rejoice in the punishment of the wicked. Secondly, indirectly, by reason namely of something annexed to it: and in this way the saints will rejoice in the punishment of the wicked, by considering therein the order of Divine justice and their own deliverance, which will fill them with joy" (Summa Theologica Illa:94:1).

It is in this way that God triumphs over evil. When the saints see His mercy magnified by His justice, they will rejoice at their own gracious salvation from sin. Stated differently, in the same way the beauty of a diamond is more evident when examined against a black background, so too it is that God’s mercy for sinners is more radiant to the saints when considered against His justice. [And] it is in this way that an apprehension of the glorious radiance of God’s mercy leads to rejoicing in God’s triumph over evil. Perhaps the next time we witness the downfall of a wicked person, we should delight not in the death of the wicked-- [for God Himself does not even delight in that! (Eze 33:11)--] but in God’s gracious sparing of our own lives.

Michael Lofton

#this is a vital distinction#an important clarification#hell#the wages of sin is death#the terror of sin#a vital warning#saint thomas aquinas#judgment#divine justice

5 notes

·

View notes

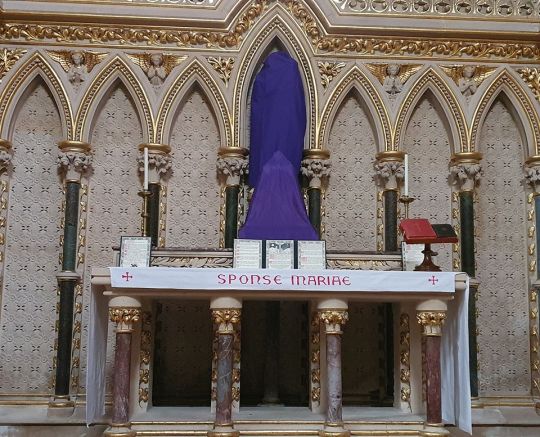

Photo

Ash Wednesday - February 17, 2021

Lent (the word “Lent” comes from the Old English “lencten,” meaning “springtime) lasts from Ash Wednesday to the Vespers of Holy Saturday — forty days + six Sundays which don’t count as “Lent” liturgically. The Latin name for Lent, Quadragesima, means forty and refers to the forty days Christ spent in the desert which is the origin of the Season.The last two weeks of Lent are known as “Passiontide,” made up of Passion Week and Holy Week. The last three days of Holy Week — Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday — are known as the “Sacred Triduum.”

The focus of this Season is the Cross and penance, penance, penance as we imitate Christ’s forty days of fasting, like Moses and Elias before Him, and await the triumph of Easter. We fast (see below), abstain, mortify the flesh, give alms, and think more of charitable works. Awakening each morning with the thought, “How might I make amends for my sins? How can I serve God in a reparative way? How can I serve others today?” is the attitude to have.

We meditate on “The Four Last Things”: Death, Judgment, Heaven, and Hell, and we also practice mortifications by “giving up something” that would be a sacrifice to do without. The sacrifice could be anything from desserts to television to the marital embrace, and it can entail, too, taking on something unpleasant that we’d normally avoid, for example, going out of one’s way to do another’s chores, performing “random acts of kindness,” etc. A practice that might help some, especially small children, to think sacrificially is to make use of “Sacrifice Beads” in the same way that St. Thérèse of Lisieux did as a child.

Because of the focus on penance and reparation, it is traditional to make sure we go to Confession at least once during this Season to fulfill the precept of the Church that we go to Confession at least once a year, and receive the Eucharist at least once a year during Eastertide. A beautiful old custom associated with Lenten Confession is to, before going to see the priest, bow before each member of your household and to any you’ve sinned against, and say, “In the Name of Christ, forgive me if I’ve offended you.” One responds with “God will forgive you.” Done with an extensive examination of conscience and a sincere heart, this practice can be quite healing (also note that confessing sins to a priest is a Sacrament which remits mortal and venial sins; confessing sins to those you’ve offended is a sacramental which, like all sacramentals one piously takes advantage of, remits venial sins. Both are quite good for the soul!)

In addition to mortification and charity, seeing and living Lent as a forty day spiritual retreat is a good thing to do. Spiritual reading should be engaged in (over and above one’s regular Lectio Divina). Maria von Trapp recommended “the Book of Jeremias and the works of Saints, such as The Ascent of Mount Carmel, by St. John of the Cross; The Introduction to a Devout Life, by St. Francis de Sales; The Story of a Soul, by St. Thérèse of Lisieux; The Spiritual Castle, by St. Teresa of Avila; the Soul of the Apostolate, by Abbot Chautard; the books of Abbot Marmion, and similar works.”

As to prayer, praying the beautiful Seven Penitential Psalms (Psalms 6, 31, 37, 50, 101, 129, and 142) is a traditional practice. It is most traditional to pray all of these each day of Lent, but if time is an issue, you can pray them all on just the Fridays of Lent, or, because there are seven of them, and seven Fridays in Lent, you might want to consider praying one on each Friday. These Psalms, which include the Psalms “Miserére” and “De Profundis,” are perfect expressions of contrition and prayers for mercy. So apt are these Psalms at expressing contrition that, as he lay dying in A.D. 430, St. Augustine asked that a monk write them in large letters near his bed so he could easily read them.

Another great prayer for this season is that of St. Ephraem, Doctor of the Church (d. 373). This prayer is often prayed with a prostration after each stanza:

O Lord and Master of my life,

take from me the spirit of sloth, despondency, lust of power, and idle talk;

But grant rather the spirit of chastity, humility, patience, and love to thy servant.

Yea, O Lord and King, grant me to see my own transgressions,

and not to judge my brother; for blessed art Thou unto the ages of ages.

In the East, this prayer is prayed liturgically during Lent and is followed by “O God, cleanse me a sinner” prayed twelve times, with a bow following each, and one last prostration.

Also, on all Fridays during Lent, one may gain a plenary indulgence, under the usual conditions, by reciting the En ego, O bone et dulcissime Iesu (Prayer Before a Crucifix) before an image of Christ crucified.

Food in Lent

According to the 1983 Code of Canon Law, the rule for the universal Church during Lent is abstain on all Fridays (inside or outside of Lent) and to both fast and abstain on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday.

Some traditional Catholics might follow the older pattern of fasting and abstinence during this time, which for the universal Church required:

Ash Wednesday, all Fridays, and all Saturdays: fasting and total abstinence. This means 3 meatless meals — with the two smaller meals not equalling in size the main meal of the day — and no snacking.

Mondays, Tuesdays, Wednesdays (except Ash Wednesday), and Thursdays: fasting and partial abstinence from meat. This means three meals — with the two smaller meals not equalling in size the main meal of the day — and no snacking, but meat can be eaten at the principle meal.

On those days of fasting and abstinence, meatless soup is traditional. Sundays, of course, are always free of fasting and abstinence; even in the heart of Lent, Sundays are about the glorious Resurrection. This pattern of fasting and abstinence ends after the Vigil Mass of Holy Saturday.

As to special Lenten foods, vegetables, seafoods, salads, pastas, and beans mark the Season, in addition to the meatless soups. The fasting of this time once even precluded the eating of eggs and fats, so the chewy pretzel became the bread and symbol of the times. They’d always been a Christian food, ever since Roman times, their very shape being the creation of monks. The three holes represent the Holy Trinity, and the twists of the dough represent the arms of someone praying. In fact, the word “pretzel” is a German word deriving ultimately from the Latin “bracellae,” meaning “little arms” (the Vatican has the oldest known representation of a pretzel, found on a 5th c. manuscript). Below is a recipe for the large, soft, chewy pretzels that go so well with beer.

by St. Thomas Aquinas Ash Wednesday : Death

By one man sin entered into this world, and by sin death.–Rom. v. 12.

1. If for some wrongdoing a man is deprived of some benefit once given to him, that he should lack that benefit is the punishment of his sin.

Now in man’s first creation he was divinely endowed with this advantage that, so long as his mind remained subject to God, the lower powers of his soul were subjected to the reason and the body was subjected to the soul.

But because by sin man’s mind moved away from its subjection to God, it followed that the lower parts of his mind ceased to be wholly subjected to the reason. From this there followed such a rebellion of the bodily inclination against the reason, that the body was no longer wholly subject to the soul.

Whence followed death and all the bodily defects. For life and wholeness of body are bound up with this, that the body is wholly subject to the soul, as a thing which can be made perfect is subject to that which makes it perfect. So it comes about that, conversely, there are such things as death, sickness and every other bodily defect, for such misfortunes are bound up with an incomplete subjection of body to soul.

2. The rational soul is of its nature immortal, and therefore death is not natural to man in so far as man has a soul. It is natural to his body, for the body, since it is formed of things contrary to each other in nature, is necessarily liable to corruption, and it is in this respect that death is natural to man.

But God who fashioned man is all powerful. And hence, by an advantage conferred on the first man, He took away that necessity of dying which was bound up with the matter of which man was made. This advantage was however withdrawn through the sin of our first parents.

Death is then natural, if we consider the matter of which man is made and it is a penalty, inasmuch as it happens through the loss of the privilege whereby man was preserved from dying.

3. Sin–original sin and actual sin–is taken away by Christ, that is to say, by Him who is also the remover of all bodily defects. He shall quicken also your mortal bodies, because of His Spirit that dwelleth in you (Rom. viii. II).

But, according to the order appointed by a wisdom that is divine, it is at the time which best suits that Christ takes away both the one and the other, i.e., both sin and bodily defects.

Now it is only right that, before we arrive at that glory of impassibility and immortality which began in Christ, and which was acquired for us through Christ, we should be shaped after the pattern of Christ’s sufferings. It is then only right that Christ’s liability to suffer should remain in us too for a time, as a means of our coming to the impassibility of glory in the way He himself came to it. (6)

by Abbot Gueranger Ash Wednesday

Yesterday the world was busy in its pleasures, and the very children of God were taking a joyous farewell to mirth: but this morning, all is changed. The solemn announcement, spoken of by the prophet, has been proclaimed in Sion: the solemn fast of Lent, the season of expiation, the approach of the great anniversaries of our Redemption. Let us then rouse ourselves, and prepare for the spiritual combat.

But in this battling of the spirit against the flesh we need good armor. Our Holy Mother the Church knows how much we need it; and therefore does She summon us to enter into the house of God, that She may arm us for the holy contest. What this armor is we know from St. Paul, who thus describes it: “Have your loins girt about with truth, and having on the breastplate of justice. And your feet shod with the preparation of the Gospel of peace. In all things, taking the shield of Faith. Take unto you the helmet of salvation, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the Word of God” (Eph. 6: 14-17). The very Prince of the Apostles, too, addresses these solemn words to us: “Christ having suffered in the flesh, be ye also armed with the same thought” (1 Peter 4: 1). We are entering today upon a long campaign of the warfare spoken of by the Apostles: forty days of battle, forty days of penance. We shall not turn cowards, if our souls can but be impressed with the conviction, that the battle and the penance must be gone through. Let us listen to the eloquence of the solemn rite which opens our Lent. Let us go whither our Mother leads us, that is, to the scene of the fall.

The enemies we have to fight with, are of two kinds: internal and external. The first are our passions; the second are the devils. Both were brought on us by pride, and man’s pride began when he refused to obey his God. God forgave him his sin, but He punished him. The punishment was death, and this was the form of the divine sentence: “For dust thou art, and into dust thou shalt return” (Gen. 3: 19). Oh that we had remembered this! The recollection of what we are and what we are to be, would have checked that haughty rebellion, which has so often led us to break the law of God. And if, for the time to come, we would persevere in loyalty to Him, we must humble ourselves, accept the sentence, and look on this present life as a path to the grave. The path may be long or short; but to the tomb it must lead us. Remembering this, we shall see all things in their true light. We shall love that God, Who has deigned to set His Heart on us, notwithstanding our being creatures of death: we shall hate, with deepest contrition, the insolence and ingratitude, wherewith we have spent so many of our few days of life, that is, in sinning against our Heavenly Father: and we shall be not only willing, but eager, to go through these days of penance, which He so mercifully gives us for making reparation to His offended justice.

This was the motive the Church had in enriching Her liturgy with the solemn rite, at which we are to assist today. When centuries ago She decreed the anticipation of the Lenten fast by the last four days of Quinquagesima week, She instituted this impressive ceremony of signing the foreheads of Her children with ashes, while saying to them those awful words, wherewith God sentenced us to death: “Remember man that thou art dust, and unto dust thou shalt return!” But the making use of ashes as a symbol of humiliation and penance, is of a much earlier date than the institution to which we allude. We find frequent mention of it in the Old Testament. Job, though a Gentile, sprinkled his flesh with ashes, that thus humbled, he might propitiate the Divine mercy (Job 16: 16): and this was 2,000 years before the coming of the Savior. The royal prophet tells us of himself, that he mingled ashes with his bread, because of the Divine anger and indignation (Ps. 101: 10, 11). Many such examples are to be met with in the sacred Scriptures; but so obvious is the analogy between the sinner who thus signifies his grief, and the object whereby he signifies it, that we read such instances without surprise. When fallen man would humble himself before the Divine justice, which has sentenced his body to return to dust, how could he more aptly express his contrite acceptance of the sentence, than by sprinkling himself, or his food, with ashes, which is the dust of wood consumed by fire? This earnest acknowledgment of his being himself but dust and ashes, is an act of humility, and humility ever gives him confidence in that God, Who resists the proud and pardons the humble.

It is probable that, when this ceremony of the Wednesday after Quinquagesima was first instituted, it was not intended for all the faithful, but only for such as had committed any of those crimes for which the Church inflicted a public penance. Before the Mass of the day began, they presented themselves at the church, where the people were all assembled. The priests received the confession of their sins, and then clothed them in sackcloth, and sprinkled ashes on their heads. After this ceremony, the clergy and the faithful prostrated, and recited aloud the Seven Penitential Psalms. A procession, in which the penitents walked barefoot, then followed; and on its return, the bishop addressed these words to the penitents: “Behold, we drive you from the doors of the church by reason of your sins and crimes, as Adam, the first man, was driven out of paradise because of his transgression.” The clergy then sang several responsories, taken from the Book of Genesis, in which mention was made of the sentence pronounced by God when He condemned man to eat his bread in the sweat of his brow, for that the earth was cursed on account of sin. The doors were then shut, and the penitents were not to pass the threshold until Holy Thursday, when they were to come and receive absolution.

Dating from the 11th century, the discipline of public penance began to fall into disuse, and the holy rite of putting ashes on the heads of all the faithful indiscriminately became so general that, at length, it was considered as forming an essential part of the Roman Liturgy. Formerly, it was the practice to approach bare-footed to receive this solemn memento of our nothingness; and in the 12th century, even the Pope himself, when passing from the church of St. Anastasia to that of St. Sabina, at which the station was held, went the whole distance bare-footed, as also did the Cardinals who accompanied him. The Church no longer requires this exterior penance; but She is as anxious as ever that the holy ceremony, at which we are about to assist, should produce in us the sentiments She intended to convey by it, when She first instituted it.

As we have just mentioned, the station in Rome is at St. Sabina, on the Aventine Hill. It is under the patronage of this holy Martyr that we open the penitential season of Lent. The liturgy begins with the Blessing of the Ashes, which are to be put on our foreheads. These ashes are made from the palms, which were blessed the previous Palm Sunday. The blessing they are now to receive in this their new form, is given in order that they may be made more worthy of that mystery of contrition and humility which they are intended to symbolize.

When the priest puts the holy emblem of penance upon you, accept in a spirit of submission, the sentence of death, which God Himself pronounces against you: “Remember, man, that thou art dust, and unto dust thou shalt return!” Humble yourself, and remember what it was (pride) that brought the punishment of death upon us: man wished to be as a god, and preferred his own will to that of his Sovereign Master.

Reflect, too, on that long list of sins, which you have added to the sin of your first parents, and adore the mercy of your God, Who asks only one death for all these your transgressions.

“When you fast, do not look gloomy like the hypocrites” (Matt. 6: 16). In the Gospel of the Mass, we learn that our Redeemer would not have us receive the announcement of the great fast as one of sadness and melancholy. The Christian who understands what a dangerous thing it is to be a debtor to Divine justice, welcomes the season of Lent with joy; it consoles him. He knows that if he be faithful in observing what the Church prescribes, his debt will be less heavy upon him. These penances, these satisfactions (which the indulgence of the Church has rendered so easy), being offered to God united with those of our Savior Himself, and being rendered fruitful by that holy fellowship which blends into one common propitiatory sacrifice the good works of all the members of the Church militant, will purify our souls, and make them worthy to partake in the grand Easter joy. Let us not, then, be sad because we are to fast; let us be sad only because we have sinned and made fasting a necessity. In this same Gospel, our Redeemer gives us a second counsel, which the Church will often bring before us during the whole course of Lent: it is that of joining almsdeeds with our fasting. He bids us to lay up treasures in Heaven. For this we need intercessors; let us seek them amidst the poor.

Every day during Lent, Sundays and feasts excepted, the priest before dismissing the faithful, adds after the Postcommunion a special prayer, which is preceded by these words of admonition: “Let us pray. Bow down your heads to God.” On this day he continues: “Mercifully look down upon us, O Lord, bowing down before Thy Divine Majesty, that they who have been refreshed with Thy Divine Mysteries, may always be supported by Thy heavenly aid. Through Our Lord Jesus Christ… Amen.” (9)

by Rev. James Luke Meagher, 1883

The fast of Lent begins on Ash Wednesday and lasts till Easter Sunday. During this time there are forty-six days, but as we do not fast on the six Sundays falling in this time, the fast lasts for forty days. For that reason it is called the forty days of Lent. In the Latin language of the Church it is called the Quadragesima, that is, forty. St. Peter, the first Pope, instituted the forty days of Lent. During the forty-six days from Ash Wednesday to Easter, we are to spend the time in fasting and in penance for our sins, building up the temple of the Lord within our hearts, after having come forth from the Babylon of this world by the rites and the services of the Septuagesima season. And as of old we read that the Jews, after having been delivered from their captivity in Babylon, spent forty-six years in building their temple in place of the grand edifice raised by Solomon and destroyed by the Babylonians, thus must we rebuild the temple of the Holy Ghost, built by God at the moment of our baptism, but destroyed by the sins of the past year. Again in the Old Testament the tenth part of all the substance of the Jews was given to the Lord (Exod. xxli. 29). Thus we must give him the tenth part of our time while on this earth. For forty days we fast, but taking out the Sundays of Lent, when there is no fast, it leaves thirty-six days, nearly the tenth part of the three hundred and sixty-five days of the year. According to Pope Gregory from the first Sunday of Lent to Easter, there are six weeks, making forty-two days, and when we take from Lent the six Sundays during which we do not fast, we have left thirty-six days, about the tenth part of the three hundred and sixty-five days of the year.

The forty days of fasting comes down to us from the Old Testament, for we read that Moses fasted forty days on the mount (Exod. xxiv. et xxxiv. 28). We are told that Elias fasted for forty days (III. Kings xix. 8), and again we see that our Lord fasted forty days in the desert (Math. iv.; Luke ix). We are to follow the example of these great men of the old law. But in order to make up the full fast of forty days of Moses, of Elias and of our Lord, Pope Gregory commanded the fast of Lent to begin on Ash Wednesday before the first Sunday of the Lenten season.

Christ began his fast of forty days after his baptism in the Jordan, on Epiphany, the twelfth of January, when he went forth into the desert. But we do not begin the Lent after Epiphany, because there are other feasts and seasons in which to celebrate the mysteries of the childhood of our Lord before we come to his fasting, and because during these forty days of Lent we celebrate the forty years of the Jews in the desert, who, when their wanderings were ended, they celebrated their Easter, while we hold ours after the days of Lent are finished. Again, during Lent, we celebrate the passion of our Lord, and as after His passion came His resurrection, thus we celebrate the glories of His resurrection at Easter.

During the services of Lent we read so often the words: “Humble your heads before the Lord,” and “let us bend our knees,” because it is the time when we should humble ourselves before God and bend our knees in prayers. After the words, “Let us bend our knees,” comes the word, “Arise.” These words are never said on Sunday, but only on week days, for Sunday is dedicated to the resurrection of our Lord. Pope Gregory says: “Who bends the knee on Sunday denies God to have risen.” We bend our knees and prostrate ourselves to the earth in prayer, to show the weakness of our bodies, which are made of earth; to show the weakness of our minds and imagination, which we cannot control; to show our shame for sin, for we cannot lift our eyes to heaven; to follow the example of our Lord, who came down from heaven and prostrated himself on the ground in the garden when in prayer (Matt. xxvi. 39); to show that we were driven from Paradise and that we are prone towards earthly things; to show that we follow the example of our father in the faith, Abraham, who, falling upon the earth, adored the Lord (Gen. xviii. 2). This was the custom from the beginning of the Christian Church, as Origen says: “The holy prophets when they were surrounded with trials fell upon their faces, that their sins might be purged by the affliction of their bodies.” Thus following the words of St. Paul: “I bow my knees to the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ (Ephes. iii. 14),” we prostrate ourselves and bend our knees in prayer. From Ash Wednesday to Passion Sunday the Preface of Lent is said every day, unless there comes a feast with a Preface of its own. That custom was in vogue as far back as the twelfth century.

At other times of the year, the clergy say the Office of Vespers after noon, but an ancient Council allowed Vespers to be commenced after Mass. This is when the Office is said altogether by the clergy in the choir. The same may be done by each clergyman when reciting privately his Office. This cannot be done on the Sundays of Lent, as they are not fasting days. The “Go, the dismissal is at hand,” is not said, but in its place, “Let us bless the Lord,” for, from the earliest times the clergy and the people remained in the church to sing the Vesper Office and to pray during this time of fasting and of penance.

We begin the fast of Lent on Wednesday, for the most ancient traditions of the Church tell us that while our Lord was born on Sunday, he was baptized on Tuesday, and began his fast in the desert on Wednesday. Again, Solomon began the building of his great temple on Wednesday, and we are to prepare our bodies by fasting, to become the temples of the Holy Ghost, as the Apostle says, “Know you not that you are the temple of God, and that the Spirit of God dwelleth in you (I. Cor. iii. 16)?” To begin well the Lent, one of the old Councils directed all the people with the clergy to come to the church on Ash Wednesday to assist at the Mass and the Vesper Offices and to give help to the poor, then they were allowed to go and break their fast.

The name Ash Wednesday comes from the ceremony of putting ashes on the heads of the clergy and the people on this day. Let us understand the meaning of this rite. When man sinned by eating in the garden the forbidden fruit, God drove him from Paradise with the words: “For dust thou art, and unto dust thou shalt return (Gen. iii. 19).” Before his sin, Adam was not to die, but to be carried into heaven after a certain time of trial here upon this earth. But he sinned, and by that sin he brought upon himself and us, his children, death. Our bodies, then, are to return to the dust from which God made them, to which they are condemned by the sin of Adam. What wisdom the Church shows us when she invites us by these ceremonies to bring before our minds the dust and the corruption of the grave by putting ashes on our heads. We see the great men of old doing penance in sackcloth and ashes. Job did penance in dust and ashes (Job ii. 12). By the mouth of His prophet the Lord commanded the Jews “in the house of the dust sprinkle yourselves with dust (Mich. i. 10).” Abraham said, “I will speak to the Lord, for I am dust and ashes (Gen xviii. 27).” Joshua and all the ancients of Israel fell on their faces before the Lord and put dust upon their heads (Joshua vii. 6). When the ark of the covenant was taken by the Philistines, the soldier came to tell the sad story with his head covered with dust (I Kings iv. 12).

When Job’s three friends came and found him in such affliction, “they sprinkled dust upon their heads toward heaven (Job ii. 12).” “The sorrows of the daughters of Israel are seen in the dust upon their heads (Lam. ii. 10).” Daniel said his prayers to the Lord his God in fasting, sackcloth and ashes (Dan. ix. 3). Our Lord tells us that if in Tyre and Sidon had been done the miracles seen in Judea, that they had long ago done penance in sackcloth and ashes (Matt. xi. 21; Luke x. 13). When the great city will be destroyed, its people will cry out with grief, putting dust upon their heads (Apoc. xviii. 19). From these parts of the Bible, the reader will see that dust and ashes were used by the people of old as a sign of deep sorrow for sin, and that when they fasted they covered their heads with ashes. From them the Church copied these ceremonies which have come down to us. And on this day, when we begin our fast, we put ashes on our heads with the words, “Remember, man, that thou art dust, and into dust thou shalt return (Gen. iii. 19).”

In the beginning of the Church the ceremony of putting the ashes on the heads of the people was only for those who were guilty of sin, and who were to spend the season of Lent in public penance. Before Mass they came to the church, confessed their sins, and received from the hands of the clergy the ashes on their heads. Then the clergy and all the people prostrated themselves upon the earth and there recited the seven penitential psalms. Rising, they formed into a procession with the penitents walking barefooted. When they came back the penitents were sent out of the church by the bishop, saying : “We drive you from the bosom of the Church on account of your sins and for your crimes, as Adam, the first man was driven from Paradise because of his sin.” While the clergy were singing those parts of Genesis, where we read that God condemned our first parents to be driven from the garden and condemned to earn their bread by the sweat of their brow, the porters fastened the doors of the church on the penitents, who were not allowed to enter the temple of the Lord again till they finished their penance and came to be absolved on Holy Thursday (Gueranger, Le Temps de la Septuagesima, p. 242). After the eleventh century public penance began to be laid aside, but the custom of putting ashes on the heads of the clergy became more and more common, till at length it became part of the Latin Rite. Formerly they used to come up to the altar railing in their bare feet to receive the ashes, and that solemn notice of their death and of the nothingness of man. In the twelfth century the Pope and all his court came to the Church of St. Sabina, in Rome, walking all the way in his bare feet, from whence the title of the Mass said on Ash Wednesday is the Station at St. Sabina.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

HOMILY for Passion Sunday (Dominican rite)

Heb 9:11-15; John 8:46-59

From Septuagesimatide, to Lent, and now to Passiontide: we have entered the third and final phase of our preparation for the Easter festival. The Crosses and sacred images have now been veiled in church, a further deprivation of the senses in this holy time of fasting and abstinence. But this year, Passiontide is truly, for all of us, as the name indicates, the time of suffering, and deprivations and the strangest of abstinences have been forced upon us: we have been deprived of access to our churches, deprived of the sacraments in some cases, and a prolonged Eucharistic fast, an abstinence from sacramental communion is the yoke placed upon us. This is the passion, the spiritual suffering, that many Catholics now undergo. And, moreover, there are the temporal sufferings of the whole world from sickness and death and the far-reaching effects of this pandemic that strike at us physically, socially, materially, and psychologically. Truly, this is a Passiontide, a time of suffering for all of humanity, that will extend beyond this fortnight of liturgical veiling.

How shall we respond, as Christians? “Stat crux dum volvitur orbis” say the Carthusians. “The Cross stands steady while the world spins”. Hence this liturgical time of Passiontide directs our attention to the Cross. The readings of this Passion Sunday Mass focusses us on the suffering and perfect sacrifice of Jesus Christ. The Liturgy today points us to the Sacrifice of the Mass itself, whereby Christ’s Cross is once again exalted in triumph over a world broken by sin and sickness and selfishness. As the preface says: “you placed the salvation of the human race on the wood of the Cross, so that, where death arose, life might again spring forth”.

Therefore, throughout this extended passiontide of the pandemic season, the Sacrifice of the Mass continues to be offered every single day in countless churches throughout the world by Christ’s priests. This is most necessary because the Mass proclaims the victory of Christ over sin and all its effects such as sickness. The Cross, that is to say, the Mass, stands steady while the world is in tailspin. And at the same time, the Mass objectively calls down upon the world, and upon the Church, the blessings that flow from Christ Crucified, namely, life and health, and, above all, the graces of salvation, eternal life.

Our forebears knew this well, and they would often go to church to “hear Mass”, even though they seldom partook of Holy Communion itself. This practice, at least since the time of Pope St Pius X, is now rather alien to our Ecclesial experience. But in the current circumstances, you now find yourself, in an odd way, through the medium of audio-visual technology, able to see and hear Mass but not partaking in sacramental Communion. You find yourselves, in a certain sense, united to this part of our liturgical tradition whereby Holy Communion was infrequent, and maybe even just an annual event. Hence, the current canon law of the Church still only obliges us to receive Communion once a year, a remnant of this (often pious) approach to infrequent Communion. But nobody doubted, thereby, that the blessings of the Mass did not continue to benefit the world and its inhabitants for their salvation and for their true good. For while the world continues to revolve, so the Cross must stand steady – the Mass, therefore is necessary for the very life and health of the world. This is the sense in which Saint Padre Pio said: “It is easier for the earth to exist without the sun than without the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass!”

But what about you as an individual? How are these blessings of the Sacrifice of Christ – his redemption and new life of grace – to be received then by you? My favourite Catechism, the St Joseph Baltimore Catechism, which was prepared for teenagers in school, puts it simply: “Those who cannot go to daily Communion, but would if they could, can make a spiritual communion. This means a real desire to go to Communion when it is impossible to receive sacramentally. This desire obtains for us from Our Lord the graces of Communion in proportion to the strength of the desire.”

There is something mysterious and providential, then, in this current situation. For when we receive Communion every day, as a matter of course, is it not possible for our desire to become less focussed on an intimate union with God through love, and more focussed on myself, my needs, and my desire to have an unbroken track record of daily Communions? Sometimes self-will and pride can be disguised by objectively good external routines. But in this period, when we cannot receive Communion – which, incidentally, has put an end to the scandal of sacrilegious and unworthy Communions – behold the wonderful work of God’s grace in this time of suffering. For to those souls who love him and know what the Mass is, is it not true that their desire for union with God has also increased? Therefore, in proportion to the strength of this desire, as the Baltimore Catechism says, know that the graces of Holy Communion are being given to you today by the good and loving and merciful Lord Jesus. In other words, nobody should despair of receiving the graces that are necessary for our salvation because God, who is not restricted by the Sacraments, can and does act without them, in an extraordinary manner, to confer graces on those souls who truly love him.

However, because you cannot see, touch, and taste the Eucharistic Lord with your own bodies, something greater is now demanded of you, namely Faith. In his hymn, Adoro Te devote, St Thomas Aquinas thus says: “Sight, touch, taste are all deceived in their judgment of you, but hearing suffices firmly to believe. I believe all that the Son of God has spoken; there is nothing truer than this word of Truth.” Therefore, in this time, as Cardinal Nichols put it, “dig deep” and believe that which the Word of God has promised. Jesus says in John 14: “I will not leave you desolate; I will come to you. Yet a little while, and the world will see me no more, but you will see me; because I live, you will live also. In that day you will know that I am in my Father, and you in me, and I in you… If a man loves me, he will keep my word, and my Father will love him, and we will come to him and make our home with him.” (John 14:18-20, 23) Or, again, as the Lord says in today’s Gospel: “If any one keeps my word, he will never see death.” (Jn 8:51)

So, the Lord, right now and throughout this time of our sufferings is present and alive in your life, and he comes to you where you are, and he gives himself to you if you open yourself to him in love, and prepare a home for him in your heart, if you treasure his Word and keep his commandment of charity. Indeed the Rededication of England to Our Lady today is precisely about this kind of faith. For just as the Lord sought out Mary in her humble abode in Nazareth, and the Word became flesh in her life, and dwelt within her, so the Lord shall also come to our homes, and, if we keep his Word because we love him, he wills to give us himself through grace and so to remain with us, dwelling within us.

Likewise, during this liturgical time of Passiontide, the sight of the crosses and saints in our churches is removed from us. Why? Because we are called to rely not on what we see and touch, but on what we know by faith. Firstly, we know that the Cross stands steady no matter how shaken the world becomes. It is our anchor and our one hope. And secondly, we recall that the Cross, although removed from our sight, is not removed from our lives. Rather, the Cross is to become part of our lives, through the different kinds of sufferings that we each carry day after day, and because we are united to Christ by grace, so the Lord is with us to carry that Cross with us, and to suffer alongside us, and therefore to sanctify us and give us a greater share in his final victory.

This time of Passiontide, therefore, although it is focussed on the sufferings of Our Lord, and the bitter pains he endured because of our sins, is not principally a time to wallow in self-reproach and shame. The Benedictine monk, Dom Pius Parsch, in his classic commentary on the traditional Liturgy, states that the Liturgy does not focus attention upon the human side of the passion as much as upon its goal, our salvation.” So, too, in this time of suffering that is the pandemic, let us remain focussed on the goal of salvation, and, with a living faith, know that in this time of suffering and death, God’s grace is poured out with even greater intensity to sanctify us. Therefore, look steadily ahead at the Cross. As our Holy Father Pope Francis said last Friday: “We have an anchor: by his cross we have been saved. We have a rudder: by his cross we have been redeemed. We have a hope: by his cross we have been healed and embraced so that nothing and no one can separate us from his redeeming love.”

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

April 30 is the feast day of St. Pius V., Pope

Source of picture: https://angelusnews.com

Life of St. Pius V.

Pope from 1566-1572 and one of the foremost leaders of the Catholic Reformation.

Born Antonio Ghislieri in Bosco, Italy, to a poor family, he labored as a shepherd until the age of fourteen and then joined the Dominicans, being ordained in 1528. Called Brother Michele, he studied at Bologna and Genoa, and then taught theology and philosophy for sixteen years before holding the posts of master of novices and prior for several Dominican houses. Named inquisitor for Como and Bergamo, he was so capable in the fulfillment of his office that by 1558, he was named grand inquisitor.

He was unanimously elected a pope in 1566. As pope, Pius saw his main objective as the continuation of the massive program of reform for the Church. He published the Roman Catechism, the revised Roman Breviary, and the Roman Missal; he also declared Thomas Aquinas a Doctor of the Church, commanded a new edition of the works of Thomas Aquinas, and created a commission to revise the Vulgate.

In dealing with the threat of the Ottoman Turks who were advancing steadily across the Mediterranean, Pius organized a formidable alliance between Venice and Spain, culminating in the Battle of Lepanto, which was a complete and shattering triumph over the Turks. The day of the victory was declared the Feast Day of Our Lady of Victory in recognition of Our Lady's intercession in answer to the saying of the Rosary all over Catholic Europe. Pius also spurred the reforms of the Church by example.

He insisted upon wearing his coarse Dominican robes, even beneath the magnificent vestments worn by the popes, and was wholeheartedly devoted to the religious life.

Source: https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=5515

Prayer to St. Pius V.

Source of picture: www.flickr.com/photos/paullew

Father, you chose Saint Pius V as pope of your Church to protect the faith and give you more fitting worship. By his prayers, help us celebrate your holy mysteries with a living faith and an effective love. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God, forever and ever. Amen.

Source: https://prayers4reparation.wordpress.com

#saints#prayer#christian religion#God#faith#Jesus#Christ#Jesus Christ#Father#St. Pius V.#pope#Dominicans#protect the faith#give God more fitting worship#Church#inquisitor

1 note

·

View note

Text

Visual Analysis “The Defenders of the Eucharist” By Peter Paul Rubens

Visual Analysis “The Defenders of the Eucharist” By Peter Paul Rubens

The medium is oil on canvas. This painting is huge, and takes up an entire wall of the museum. The dimension is 171 by 175 inches. There’s a wide range of colors. Three men dressed in gold, two in black, one in white, and one in red. The sky is a mix of grey, blue, and white. There’s few defined shapes but the main are the rectangular prisms on the sacrament of the Eucharist and the book. The subjects are the seven saints: St. Jerome, St. Norbert, Thomas Aquinas, Ste. Clare, Gregory the Great, St.Ambrose, and St Augustine. The work is designed with the saints as the main focus but in the background is an owl in the sky, fruits and flowers along the top, and two angel babies on each of the top corners. The painting is not balanced because there is an odd number of men. There is emphasis on the owl. The streaks of light are highlighting it. The rhythm is seen in the hand positions and the babies stance. The proportion of the objects show the difference in size and closeness. The colors contrast on the saint’s outfits. This work makes me feel like the owl is coming from heaven towards me. I feel this way because the lights are shinning down from the clouds. The work was created in the Renaissance times. This painting was one of eleven in the ‘The Triumph of the Eucharist’. Archduchess Isabella commissioned the paintings as a gift for the convent of the Descalzas Reales. The artwork displays how the artist feels towards the religion. Peter Paul Rubens was deeply faithful. There was a lot of time put into the series proving Rubens to be patient. Rubens was trying to persuade others to be fascinated by religion. He is able to get his message across very effectively. From first glance, I begin to understand the painting even though I am from a different religion. Based on my research, the importance of this artwork to the world is the reminder that god is looking down from above. It is meant to encourage the mass society to practice Catholicism and Eucharist. I chose The Defenders of Eucharist because it was the first artwork I saw and was amazed by the large size. I also was intrigued by the custom framing and room design matching the painting. The artwork itself captured my attention rather than the religious meaning which truthfully was the original intent. However after researching the painting I learned a lot about Catholicism which I had never taken the time to do previously. Rubens goal of spreading knowledge about his religion through his painting is effective even 395 years later.

Citations

John. “Five Facts about Rubens at The Ringling.” The Ringling, 17 Aug. 2017, www.ringling.org/five-facts-about-rubens-ringling.

“Peter Paul Rubens.” History Reference Center Database, 2020, union.discover.flvc.org/mj.jsp?st=Peter+paul+ruben&ix=kw&fl=ba&V=D&S=1461584586280972&I=2#top.

Rubens, Peter Paul. “The Defenders of the Eucharist.” EMuseum, 1 Jan. 1970, emuseum.ringling.org/emuseum/objects/24720/the-defenders-of-the-eucharist?ctx=c01cbaa6-71bb-4b1f-acc0-a21967189ca6&idx=3.

“The Defenders of the Eucharist.” The Defenders of the Eucharist, ringlingdocents.org/defenders2.htm.

0 notes

Link

March 16, 2020 Novena to St. Joseph, the Husband of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Day 7 Dear Family of Mary! Today is Day 7 of our Novena to St. Joseph! As we draw near to St. Joseph's feast day, March 19, it seems clear that we are in a very difficult time. The coronavirus is spreading through the world, and it is effectively stopping us in our tracks. There is no cure for this virus yet. So, we can only wait and see if we can escape it. We are vulnerable, and small before this little virus. But we have mighty advocates with the Lord. Both St. Joseph and Our Blessed Mother Mary are with us to help us. Our Lady is especially close to us in Medjugorje. But St. Joseph is always at her side. And so, we have recourse!! We have help in this difficult hour. Our Lady once said to us: June 2, 2007 "Dear children! Also, in this difficult time God's love sends me to you. My children do not be afraid, I am with you. With complete trust give me your hearts, that I may help you to recognize the signs of the time in which you live. I will help you to come to know the love of my Son. I will triumph through you. Thank you." Her words are even more powerful today, than they were in 2007. God's love has sent her to us!! He knows we need our Mother at just such a time. With our Rosaries we can hold on to her hand, like children, praying with hope and confidence. I just love it when she tells us: "My children, do not be afraid, I am with you." Children know the comfort of the mother's presence at night, in the dark. With her, they can be at peace. All is well. In our darkness today, our Mother is with us, what more do we need? "With complete trust give me your hearts, that I may help you to recognize the signs of the time in which you live." Just so. When a child is in the dark, the mother comes and grasps him by the hand and leads him out of the dark into the light. She shows him where he is and keeps him safe. We have been and are in a very dark moment in history, even before this virus. But Our Mother is leading us to the light, to peace and safety. She will show us the way and interpret the signs for us. "I will help you to come to know the love of my Son, I will triumph through you!" Mother Mary is leading us to Jesus, and when we see Him, it will be the Triumph!! Jesus will come to Crown His Mother as Queen of Heaven and Earth and quell all her enemies. This is where we are headed. St. Joseph is here, at Mary's side, silently supporting her and interceding for us. Here is what St. Thomas Aquinas had to say about St. Joseph: WORDS OF ST. THOMAS AQUINAS "Some Saints are privileged to extend to us their patronage with particular efficacy in certain needs, but not in others; but our holy patron St. Joseph has the power to assist us in all cases, in every necessity, in every undertaking." Dear St. Joseph, we believe that you can help us in every situation. Pray for us to finally give Mary our hearts, to trust her, and let her lead us. Pray that we can recognize the signs of the times in which we live and respond to them with holiness and love. Bring us safely into the Triumph of the Immaculate Heart of Mary!! Amen The prayer to St. Joseph, for the Mary TV Family: Remember, O most chaste spouse of the Blessed Virgin Mary, that never was it known that anyone who implored your help or sought your intercession was left unaided. Filled with confidence we implore you, O faithful St. Joseph: help us now in our turn not to leave the side of Mary, our Mother, Queen of Peace of Medjugorje, Queen of Divine Mercy. Help us St. Joseph, to be like you, faithful to her in everything. Help us respond to her call. St. Joseph, Foster Father of us all, hear us and answer us. Amen. In Jesus, Mary and Joseph! Cathy Nolan©Mary TV 2020

0 notes

Text

Benozzo Gozzoli - Triumph of Saint Thomas Aquinas. Detail. 1470 - 1475

257 notes

·

View notes

Text

Week of 4/28/2017

As we come closer to Holy Week and the Passion of Our Lord, we come face to face with the mystery of suffering and the grace it can bring. Years ago, a wise and elderly priest mentor of mine told me about a blind man named Matthew he met in 1952 who would attend every daily mass of St. Padre Pio’s. Padre Pio asked Matthew once if he would like to be cured. The man replied no, saying that he thought a cure would endanger his soul. To our world, an outlandish response. But, considering how Padre Pio accepted that answer, we must look for the presence of a mysterious grace that underlies such a response. It remains a powerful testimony to what St. Paul called the folly of the cross. This man, undoubtedly influenced by the remarkable holiness of St. Padre Pio, saw in his infirmity a reminder of his fragility, as well as protection from the pride of the world. Personal pain is permitted by God not as punishment but as a means to remind ourselves that we need God, to overcome selfishness, and that we need to understand what God did for us on the cross. The blindness is a handicap to the world, but to the supernatural reality of Matthew, it was a reminder of Christ’s suffering, and a means for growing in holiness; it was actually liberating for him. Such a personal discovery on Matthew’s part was the result of God’s grace; only the Lord’s holiness could have such an effect. In our own world, we are confronted by so much pain. Our Lord sees the amount of pain each person suffers from and wishes deeply to strengthen us, to heal us, to reveal to us that through. His cross He will help us overcome that pain. He will even turn that pain into a source of spiritual strength if we seek Him. All of sudden the cross becomes an anchor and ladder that grounds us and lets us reach heights we could not have reached all by ourselves. Jesus embraces and kisses His cross in the movie the Passion of the Christ, to show that while the Cross seemed to be a triumph of the world and the devil over God, it really becomes the victory sign of God when it is embraced with love. As we prepare for launching perpetual adoration here at St. Theresa’s, we are reminded yet again about the worst blindness, sin and ignorance of God. Sin waters down our passion for God; ignorance of Church teaching means ignorance of the way to heaven. The wisest are not the worldly successful; the wisest are those who see God and worship Him with great love in the hidden grace of the Holy Eucharist. When we reflect on our pain and frailty, the best salve is always the intense presence of God. By worshiping God in the Holy Eucharist, we sensitize the soul to the infinite generosity, love and healing power of God. We impassioned the soul to live for virtue. We find great joy in bringing others to Christ. And, we come to realize more deeply that infirmities and difficulties actually enable deeper holiness and thus deeper peace. To those of the world, nonsense. But to St. Thomas Aquinas, St Pope John Paul II, the soon to be saints Jacinta and Francisco of Fatima, this is the Truth. Pain initiates a journey into self knowledge; the anger or bitterness that may result from it becomes a gauge for which to admit to ourselves we have much to learn and bad habits to break. But Jesus walks with us every step of the way, and His Cross supplies us with towering strength. Let us always remember to seek the Lord always, that through His presence in the sacraments and prayer. He will lead us to the greatest victory. It is only through the Cross do we find true love, freedom, and eternal peace. God love you

0 notes

Photo

Second Saint of the Day – 18 February – St Flavian (Died 449) Archbishop of Constantinople, Martyr, Confessor, Defender of the Christ’s two natures, both divine and human.

St Flavian endured condemnation and severe beatings during a fifth-century dispute about the humanity and divinity of Jesus Christ. Though he died from his injuries, his stand against heresy was later vindicated at the Church’s fourth ecumenical council in 451.

St Flavian is closely associated with St Pope Leo the Great (400-461), who also upheld the truth about Christ’s divine and human natures during the controversy. The Pope’s best-known contribution to the fourth council – a letter known as the “Tome of Leo” – was originally addressed to St Flavian, though it did not reach him during his lifetime.

Flavian’s date of birth is unknown, as are most of his biographical details. He was highly-regarded as a priest during the reign of the Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius II (which lasted from 408 to 450) and he became Archbishop of Constantinople following the death of Saint Proclus in approximately 447.

Early in his reign, Flavian angered a state official named Chrysaphius by refusing to offer a bribe to the emperor. The ruler’s wife Eudocia joined the resulting conspiracy which Chrysaphius hatched against Flavian, a plot that would come to fruition in an illegitimate Church council and the patriarch’s death.

As head of the Church in Constantinople, Flavian had inherited a theological controversy about the relationship between deity and humanity in the person of Jesus Christ. In an occurrence that was not uncommon for the time, the doctrinal issue became entangled with personal and political rivalries. Flavian’s stand for orthodoxy gave his high-ranking court opponents a chance to act against him by encouraging the proponents of doctrinal error and manipulating the emperor in their favour.

The theological issue had arisen after the Council of Ephesus, which in 431 had confirmed the personal unity of Christ and condemned the error (known as Nestorianism) that said He was a composite being made up of a divine person and a human person. But questions persisted: Were Jesus’ eternal divinity and His assumed humanity, two distinct and complete natures fully united in one person? Or did the person of Christ have only one hybrid nature, made up in some manner of both humanity and divinity?

The Church would eventually confirm that the Lord’s incarnation involved both a divine and a human nature, at all times. When God took on a human nature at the incarnation, in the words of St Leo the Great, “the proper character of both natures was maintained and came together in a single person,” and “each nature kept its proper character without loss.”

During Flavian’s reign, however, the doctrine of Christ’s two natures had not been fully and explicitly defined. Thus, controversy came up regarding the doctrine of a monk named Eutyches, who insisted that Christ had only “one nature.” Flavian understood the “monophysite” doctrine as contrary to faith in Christ’s full humanity and he condemned it at a local council in November of 448. He excommunicated Eutyches and sent his decision to Pope Leo, who gave his approval in May 449.

Chrysaphius, who knew Eutyches personally, proceeded to use the monk as his instrument against the patriarch who had angered him. He convinced the emperor that a Church council should be convened to consider Eutyches’ doctrine again. The resulting council, held in August 449 and led by Dioscorus of Alexandria, was completely illegitimate and later formally condemned. But it pronounced against Flavian and declared him deposed from the patriarchate.

During this same illicit gathering, known to history as the “Robber Council,” a mob of monks beat St Flavian so aggressively that he died from his injuries three days later. Chrysaphius seemed, for the moment, to have triumphed over the Archbishop.

But the state official’s ambitions soon collapsed. Chrysaphius fell out of favour with Theodosius II shortly before the emperor’s death in July 450 and he was executed early in the reign of his successor Marcian.

St Flavian, meanwhile, was Canonised by the Fourth Ecumenical Council in 451. Its participants gave strong acclamation to the “Tome of Leo” – in which the Pope confirmed St Flavian’s condemnation of Eutyches and affirmed the truth about Christ’s two natures, both divine and human.

We bless you, holy St Flavian, pray for us, Amen!

Altar of Recanati, Polytypch, left wing - St Thomas Aquinas and St Flavian of Constantinople.

(via Saint of the Day - 18 February - St Flavian of Constantinople (Died 449) Martyr)

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Can you name the painters by two of their most important works? quizz

Years Painter Famous Work 1881-1973 Les Desmoiselles d'Avignon / Guernica c.1267-1337 Scrovegni Chapel 1452-1519 Mona Lisa / The Last Supper 1839-1906 Rideau, Cruchon et Compotier / Mont Sainte-Victoire 1606-1669 The Night Watch / Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp 1599-1660 Las Meninas 1866-1944 Der Blaue Reiter / On White II 1840-1926 Water Lillies / Impression, Sunrise 1571-1610 Cardsharps / Calling of St. Matthew 1775-1881 Rain, Steam and Speed - The Great Western Railway 1390-1441 Arnolfini Wedding / Ghent Altarpiece 1471-1528 Apocalypse Woodcuts / Knight, Death and the Devil 1912-1956 No. 5 / Blue Poles 1475-1564 David / Sistine Chapel Ceiling 1848-1903 Yellow Christ / Where Do We Come From? What Are We Where Are We Going? 1746-1828 Third of May, 1808 / Disasters of War 1853-1890 Starry Night / The Potato Eaters 1832-1883 Luncheon on the Grass / Olympia 1903-1970 Seagram Murals / White Center (Yellow, Pink and Lavender on Rose) 1869-1954 Woman With a Hat / The Plum Blossoms 1483-1520 School of Athens / The Parnassus 1960-1988 Profit I / Untitled Graffiti 1863-1944 The Scream / The Sick Child 1872-1944 Broadway Boogie Woogie / Composition with Red, Yellow and Blue 1416-1492 Flagellation of Christ / Brera Madonna 1577-1640 The Fall of Man / Massacre of the Innocents 1928-1987 Campbell's Soup Cans / Exploding Plastic Inevitable 1893-1983 Dona i Ocell / The Tilled Field 1401-1428 Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, Tribute Money / Holy Trinity 1887-1985I, and the Village / Stained Glass Works 1819-1877A Burial at Ornans / The Origin of the World c.1476-1576 Venus D'Urbino / Assumption of the Virgin 1594-1665 Rape of the Sabine Women / Et in Arcade Ego 1904-1997 Woman III / Easter Monday YearsPainterFamous Work 1879-1940 Twittering Machine / Fish Magic 1909-1992 Study for a Self Portrait - Triptych / Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion 1862-1918 The Kiss / Danae 1798-1863 Liberty Leading the People / Massacre at Chios 1397-1475 Saint George and the Dragon / Funerary Monument to Sir John Hawkwood 1757-1827 The Ghost of a Flea / The Song of Los 1878-1935 Black Square / White On White 1431-1506 St. Sebastian / Lamentation Over the Dead Christ 1632-1675 Girl With a Pearl Earring / View of Delft 1541-1614 View of Toledo / The Burial of the Count of Orgaz 1774-1840 Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog / The Abbey in the Oakwood 1836-1910 The Gulf Stream / The Bathers 1887-1968 Nude Descending a Staircase No.2 / Etant Donnes 1478-1510 The Tempest / Sleeping Venus 1907-1954 Self Portrait - Time Flies / Mi Nacimiento 1497-1543 The Ambassadors / Portrait of Erasmus of Rotterdam 1834-1917 New Orleans Cotton Exchange / The Absinthe Drinker 1387-1455 Day of Judgment / Transfiguration 1859-1891 Sunday Afternoon of the Island of La Grande Jatte / Bathers at Asnieres 1684-1721 Embarkation for Cythera / L'Enseigne de Gersaint 1904-1989 Persistence of Memory / Swans Reflecting Elephants 1891-1976 Europe After the Rain II / Men Shall Know Nothing of This 1518-1594 The Siege of Asola / The Last Supper born 1930- Flags / Targets 1445-1510 Birth of Venus / Primavera born 1937- The Joiners / A Bigger Splash 1882-1916 Unique Forms of Continuity In Space / The Street Enters the House 1480-1524 Landscape with Charon Crossing Styx / Landscape with St. Christopher c.1255-1318 Measta with Twenty Angels and Nineteen Saints / Rucellai Madonna 1399-1464 The Descent From the Cross / Adoration of the Magi 1776-1837 The Hay Wain / Dedham Vale 1748-1825 The Death of Marat / Oath of the Horatii 1905-1948 Landscape in the Manner of Cezanne / Nighttime, Enigma, Nostalgia 1450-1516 Garden of Earthly Delights / The Temptation of St. Anthony YearsPainterFamous Work 1528-1569 Landscape with the Fall of Icarus / The Peasant Wedding 1284-1344 The Annunciation with St. Margaret and St. Asano / S. Caterina Polyptych 1826-1900 The Heart of the Andes / Aurora Borealis 1882-1967 Nighthawks / Chop Suey 1899-1968 Spatial Concept / Luce Spaziale 1880-1916 The Fate of the Animals / Fighting Forms 1841-1919 Luncheon of the Boating Party / Girl With a Watering Can 1856-1921 Arrangement in Grey and Black - The Artists' Mother / Old Battersea Bridge 1791-1824 The Raft of the Medusa / The Charging Chasseur 1697-1764 A Rake's Progress / Marriage a-la-Mode 1796-1875 Souvenir de Mortefontaine / Ville d'Avray 1882-1963 Woman With a Guitar / Fruitdish and Glass 1435-1949 Advent and Triumph of Christ / Earthly Vanity and Divine Salvation born 1932 -Acht Grau / Baader-Meinhof 1884-1920 Madame Pompadoure / Jeanne Humberterne in Red Shawl 1593-1652 The Fortune Teller / Hurdy-Gurdy Player 1597-1654 Judith Slaying Holofernes / Susanna and the Elders 1814-1875 Angelus / The Gleaners c.1240-1302 The Madonna of St. Francis / Virgin and Child 1860-1949 Entry of Christ Into Brussels / The Vile Vivisectors 1898-1967 The Son of Man / Time Transfixed 1598-1664 Altar Piece of St. Thomas Aquinas / Death of St. Bonaventure 1890-1941 Proun / Wolkenbugel (Horizontal Skyscrapers) 1890-1918 Portrait of Wally / Self Portrait: 1912 1828-1882A Vision of Flammetta / The Blessed Damozel c.1580-1666 Gipsy Girl / Laughing Cavalier 1600-1682 Landscape with Mechants (The Shipwreck) / Marriage of Isaac and Rebekah 1923-1997 Ohh...Alright... / Whaam! 1887-1986 No.13 Special - Charcoal on Paper / Ram's Head White Hollyhock and Little Hills 1826-1898 Oedipus and the Sphinx / Athenians with the Minotaur 1888-1978 The Disquieting Muses / Enigma of the Hour 1881-1955 The Disks / The City 1780-1867 La Grande Odalisque / The Turkish Bath

0 notes

Photo

Ash Wednesday

Lent (the word “Lent” comes from the Old English “lencten,” meaning “springtime) lasts from Ash Wednesday to the Vespers of Holy Saturday — forty days + six Sundays which don't count as “Lent” liturgically. The Latin name for Lent, Quadragesima, means forty and refers to the forty days Christ spent in the desert which is the origin of the Season.The last two weeks of Lent are known as “Passiontide,” made up of Passion Week and Holy Week. The last three days of Holy Week — Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday — are known as the “Sacred Triduum.”

The focus of this Season is the Cross and penance, penance, penance as we imitate Christ's forty days of fasting, like Moses and Elias before Him, and await the triumph of Easter. We fast (see below), abstain, mortify the flesh, give alms, and think more of charitable works. Awakening each morning with the thought, “How might I make amends for my sins? How can I serve God in a reparative way? How can I serve others today?” is the attitude to have.

We meditate on “The Four Last Things”: Death, Judgment, Heaven, and Hell, and we also practice mortifications by “giving up something” that would be a sacrifice to do without. The sacrifice could be anything from desserts to television to the marital embrace, and it can entail, too, taking on something unpleasant that we'd normally avoid, for example, going out of one's way to do another's chores, performing “random acts of kindness,” etc. A practice that might help some, especially small children, to think sacrificially is to make use of “Sacrifice Beads” in the same way that St. Thérèse of Lisieux did as a child.

Because of the focus on penance and reparation, it is traditional to make sure we go to Confession at least once during this Season to fulfill the precept of the Church that we go to Confession at least once a year, and receive the Eucharist at least once a year during Eastertide. A beautiful old custom associated with Lenten Confession is to, before going to see the priest, bow before each member of your household and to any you've sinned against, and say, “In the Name of Christ, forgive me if I've offended you.” One responds with “God will forgive you.” Done with an extensive examination of conscience and a sincere heart, this practice can be quite healing (also note that confessing sins to a priest is a Sacrament which remits mortal and venial sins; confessing sins to those you've offended is a sacramental which, like all sacramentals one piously takes advantage of, remits venial sins. Both are quite good for the soul!)

In addition to mortification and charity, seeing and living Lent as a forty day spiritual retreat is a good thing to do. Spiritual reading should be engaged in (over and above one's regular Lectio Divina). Maria von Trapp recommended “the Book of Jeremias and the works of Saints, such as The Ascent of Mount Carmel, by St. John of the Cross; The Introduction to a Devout Life, by St. Francis de Sales; The Story of a Soul, by St. Thérèse of Lisieux; The Spiritual Castle, by St. Teresa of Avila; the Soul of the Apostolate, by Abbot Chautard; the books of Abbot Marmion, and similar works.”

As to prayer, praying the beautiful Seven Penitential Psalms (Psalms 6, 31, 37, 50, 101, 129, and 142) is a traditional practice. It is most traditional to pray all of these each day of Lent, but if time is an issue, you can pray them all on just the Fridays of Lent, or, because there are seven of them, and seven Fridays in Lent, you might want to consider praying one on each Friday. These Psalms, which include the Psalms “Miserére” and “De Profundis,” are perfect expressions of contrition and prayers for mercy. So apt are these Psalms at expressing contrition that, as he lay dying in A.D. 430, St. Augustine asked that a monk write them in large letters near his bed so he could easily read them.

Another great prayer for this season is that of St. Ephraem, Doctor of the Church (d. 373). This prayer is often prayed with a prostration after each stanza:

O Lord and Master of my life, take from me the spirit of sloth, despondency, lust of power, and idle talk;

But grant rather the spirit of chastity, humility, patience, and love to thy servant.

Yea, O Lord and King, grant me to see my own transgressions, and not to judge my brother; for blessed art Thou unto the ages of ages.

In the East, this prayer is prayed liturgically during Lent and is followed by “O God, cleanse me a sinner” prayed twelve times, with a bow following each, and one last prostration.

Also, on all Fridays during Lent, one may gain a plenary indulgence, under the usual conditions, by reciting the En ego, O bone et dulcissime Iesu (Prayer Before a Crucifix) before an image of Christ crucified.

Food in Lent

According to the 1983 Code of Canon Law, the rule for the universal Church during Lent is abstain on all Fridays (inside or outside of Lent) and to both fast and abstain on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday.

Some traditional Catholics might follow the older pattern of fasting and abstinence during this time, which for the universal Church required:

Ash Wednesday, all Fridays, and all Saturdays: fasting and total abstinence. This means 3 meatless meals — with the two smaller meals not equaling in size the main meal of the day — and no snacking.

Mondays, Tuesdays, Wednesdays (except Ash Wednesday), and Thursdays: fasting and partial abstinence from meat. This means three meals — with the two smaller meals not equaling in size the main meal of the day — and no snacking, but meat can be eaten at the principle meal. On those days of fasting and abstinence, meatless soup is traditional. Sundays, of course, are always free of fasting and abstinence; even in the heart of Lent, Sundays are about the glorious Resurrection. This pattern of fasting and abstinence ends after the Vigil Mass of Holy Saturday.

As to special Lenten foods, vegetables, seafood's, salads, pastas, and beans mark the Season, in addition to the meatless soups. The fasting of this time once even precluded the eating of eggs and fats, so the chewy pretzel became the bread and symbol of the times. They'd always been a Christian food, ever since Roman times, their very shape being the creation of monks. The three holes represent the Holy Trinity, and the twists of the dough represent the arms of someone praying. In fact, the word “pretzel” is a German word deriving ultimately from the Latin “bracellae,” meaning “little arms” (the Vatican has the oldest known representation of a pretzel, found on a 5th c. manuscript). Below is a recipe for the large, soft, chewy pretzels that go so well with beer.

BY ST. THOMAS AQUINAS Ash Wednesday : Death

By one man sin entered into this world, and by sin death.–Rom. v. 12.

1. If for some wrongdoing a man is deprived of some benefit once given to him, that he should lack that benefit is the punishment of his sin.

Now in man's first creation he was divinely endowed with this advantage that, so long as his mind remained subject to God, the lower powers of his soul were subjected to the reason and the body was subjected to the soul.

But because by sin man's mind moved away from its subjection to God, it followed that the lower parts of his mind ceased to be wholly subjected to the reason. From this there followed such a rebellion of the bodily inclination against the reason, that the body was no longer wholly subject to the soul.

Whence followed death and all the bodily defects. For life and wholeness of body are bound up with this, that the body is wholly subject to the soul, as a thing which can be made perfect is subject to that which makes it perfect. So it comes about that, conversely, there are such things as death, sickness and every other bodily defect, for such misfortunes are bound up with an incomplete subjection of body to soul.

2. The rational soul is of its nature immortal, and therefore death is not natural to man in so far as man has a soul. It is natural to his body, for the body, since it is formed of things contrary to each other in nature, is necessarily liable to corruption, and it is in this respect that death is natural to man.

But God who fashioned man is all powerful. And hence, by an advantage conferred on the first man, He took away that necessity of dying which was bound up with the matter of which man was made. This advantage was however withdrawn through the sin of our first parents.

Death is then natural, if we consider the matter of which man is made and it is a penalty, inasmuch as it happens through the loss of the privilege whereby man was preserved from dying.

3. Sin–original sin and actual sin–is taken away by Christ, that is to say, by Him who is also the remover of all bodily defects. He shall quicken also your mortal bodies, because of His Spirit that dwelleth in you (Rom. viii. II).

But, according to the order appointed by a wisdom that is divine, it is at the time which best suits that Christ takes away both the one and the other, i.e., both sin and bodily defects.

Now it is only right that, before we arrive at that glory of impassibility and immortality which began in Christ, and which was acquired for us through Christ, we should be shaped after the pattern of Christ's sufferings. It is then only right that Christ's liability to suffer should remain in us too for a time, as a means of our coming to the impassibility of glory in the way He himself came to it.

BY ABBOT GUERANGER ASH WEDNESDAY Yesterday the world was busy in its pleasures, and the very children of God were taking a joyous farewell to mirth: but this morning, all is changed. The solemn announcement, spoken of by the prophet, has been proclaimed in Sion: the solemn fast of Lent, the season of expiation, the approach of the great anniversaries of our Redemption. Let us then rouse ourselves, and prepare for the spiritual combat.

But in this battling of the spirit against the flesh we need good armor. Our Holy Mother the Church knows how much we need it; and therefore does She summon us to enter into the house of God, that She may arm us for the holy contest. What this armor is we know from St. Paul, who thus describes it: “Have your loins girt about with truth, and having on the breastplate of justice. And your feet shod with the preparation of the Gospel of peace. In all things, taking the shield of Faith. Take unto you the helmet of salvation, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the Word of God” (Eph. 6: 14-17). The very Prince of the Apostles, too, addresses these solemn words to us: “Christ having suffered in the flesh, be ye also armed with the same thought” (1 Peter 4: 1). We are entering today upon a long campaign of the warfare spoken of by the Apostles: forty days of battle, forty days of penance. We shall not turn cowards, if our souls can but be impressed with the conviction, that the battle and the penance must be gone through. Let us listen to the eloquence of the solemn rite which opens our Lent. Let us go whither our Mother leads us, that is, to the scene of the fall.