#Treaty of Traverse Des Sioux of 1851

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

State of Minnesota Transferring State Park to Dakota Tribe

The State of Minnesota is now engaged in transferring the Upper Sioux Agency State Park in the southwestern part of the State to a Dakota Indian Tribe that was involved in its tragic history.[1] Historical Background The Treaty of Traverse Des Sioux of 1851 moved the Dakota Indians from Iowa and Minnesota to a reservation 20 miles wide in southwestern Minnesota along the Minnesota River Valley.…

View On WordPress

#Dakota Indian Tribe#Kevin Jensvold#Mary Kunesh#Minnesota#Standing Rock Nation#Treaty of Traverse Des Sioux of 1851#U.S.-Dakota War of 1862#Upper Sioux Agency State Park#Yellow Medicine Agency

1 note

·

View note

Text

In 1851, Sibley helped introduce land-grant legislation for the purpose of a territorial university, and just three days after Congress passed the bill, Minnesota’s territorial leaders established the University of Minnesota. With an eye on statehood, leaders knew more land would be granted for higher education, but first the land had to be made available. That same year, with the help of then-territorial governor and fellow university regent Alexander Ramsey, the Dakota signed the Treaty of Traverse De Sioux, a land cession that created almost half of the state of Minnesota, and, taken with other cessions, would later net the University nearly 187,000 acres of land — an area roughly the size of Tucson. Among the many clauses in the treaty was payment: $1.4 million would be given to the Dakota, but only after expenses. Ramsey deducted $35,000 for a handling fee, about $1.4 million in today’s dollars. After agencies and politicians had taken their cuts, the Dakota were promised only $350,000, but ultimately, only a few thousand arrived after federal agents delayed and withheld payments or substituted them for supplies that were never delivered. The betrayal led to the Dakota War of 1862. “The Sioux Indians of Minnesota must be exterminated or driven forever beyond the borders of the state,” said Governor Ramsey. Sibley joined in the slaughter, leading an army of volunteers dedicated to the genocide of the Dakota people. At the end of the conflict, Ramsey ordered the mass execution of more than 300 Dakota men in December of 1862 — a number later reduced by then-president Abraham Lincoln to 39, and still the largest mass execution in U.S. history. That grisly punctuation mark at the end of the war meant a windfall for the University of Minnesota, with new lands being opened through the state’s enabling act and another federal grant that had just been passed: the Morrill Act. Within weeks of the mass execution, the university was reaping benefits thanks to the political, and military, power of Sibley and the board of regents.

—Eliseu Cavalcante, from "Misplaced Trust," published by Grist

#quotes#essays#eliseu cavalcante#grist#landback#indigenous rights#minnesota#dakota#university of minnesota

1 note

·

View note

Text

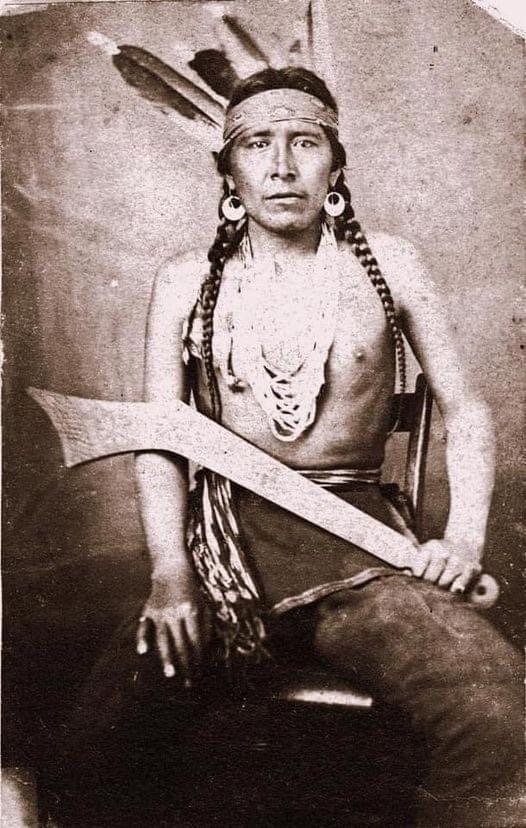

Chief Big Eagle 🦅 (1827-1906)

Mdewakanton Dakota Chief; during the US-Dakota War of 1862, he commanded a Mdewakanton Dakota band of two hundred warriors at Crow Creek in McLeod County, Minn. His Dakota name was "Wamdetonka," which literally means Great War Eagle, but he was commonly called Big Eagle. He was born in his Black Dog's village a few miles above Mendota on the south bank of the Minnesota River in 1827. When he was a young man, he often went on war parties against the Ojibwe and other enemies of the Dakota. He wore three eagle's feathers to show his coups. When his father Chief Grey Iron died, he succeeded him as sub-chief of the Mdewakanton band.

In 1851, by the terms of the treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota, The Dakota sold all of their land in Minnesota except a strip ten miles wide near the Minnesota River. In 1857, Big Eagle succeeded his father, Grey Iron, as Chief. In 1858, the remaining land was sold through the influence of Little Crow. That same year, Big Eagle went with some other chiefs to Washington D. C. to negotiate grievances with federal officials. Negotiations were unsuccessful. In 1894, he was interviewed about the Dakota War and its causes. He spoke about how the Indians wanted to live as they did before the treaty of Traverse des Sioux – to go where they pleased and when they pleased; hunt game wherever they could find it, sell their furs to the traders and live as they could. He also spoke of the corruption among the Indian agents and traders, with no legal recourse for the Dakota, and the way they were treated by many of the whites: "They always seemed to say by their manner when they saw an Indian, 'I am much better than you,' and the Indians did not like this. There was excuse for this, but the Dakotas did not believe there were better men in the world than they..."

In 1862, Big Eagle's village was on Crow Creek, Minn. His band numbered about 200 people, including 40 warriors. As the summer of 1862 advanced, conflict boiled among the Dakota who wanted to live like the white man and the majority who didn't. The Civil War was in full force and many Minnesota men had left their homes to fight in a war that the North was said to be losing. Some longtime Indian agents who were trusted by the Dakota were replaced with men who did not respect the Indians and their culture. Most of the Dakota believed it was a good time to go to war with the whites and take back their lands. Though he took part in the war, he said he was against it. He knew there was no good cause for it, as he had been to Washington and knew the power of the whites and believed they would ultimately conquer the Dakota people.

When war was declared, Chief Little Crow told some of Big Eagle's band that if he refused to lead them, they were to shoot him as a traitor who would not stand up for his nation and then select another leader in his place. When the war broke out on Aug. 17, 1862, he first saved the lives of some friends - George H. Spencer and a half-breed family - and then led his men in the second battles at Fort Ridgely and New Ulm on August 22 and 23. Some 800 Dakota were at the battle of Fort Ridgely, but could not defeat the soldiers due to their defense with artillery. They retreated and a few days later, he and his band trailed some soldiers to their encampment at Birch Coulee, near Morton in Renville County. About 200 of the Dakota surrounded the camp and attacked it at daylight. After two days of battle, General Sibley arrived with reinforcements and the Dakota eventually retreated. He and his band participated in a last attempt to defeat the whites at the battle of Wood Lake on September 23. However, they were once again defeated when their hiding place for ambush was discovered prematurely by some soldiers who went foraging for food

Soon after the battle, Big Eagle and other Dakotas who had taken part in the war surrendered to General Sibley with the understanding they would be given leniency. However, he was one of about 400 Dakota men who were tried by a Military Commission for alleged war crimes or atrocities committed during the war. After a kangaroo court trial, Big Eagle was sentenced to ten years in prison for taking part in the war. At his trial, a great number of witnesses were interviewed, but none could say that he had murdered any one or had done anything to deserve death. Therefore, he was saved from death by hanging. He was released after serving three years of his sentence in the prison at Davenport and the penitentiary at Rock Island. He believed his imprisonment for that long of a time was unjust because he had surrendered in good faith. He had not murdered any whites and if he killed or wounded a man, it had been in a fair, open fight.

The translators who interviewed him in 1894 described him as being very frank and unreserved, candid, possessing more than ordinary intelligence, and deliberate in striving to speak the truth. When speaking of his imprisonment, he said that all feeling on his part about it had long since passed away. He had been known as Jerome Big Eagle, but his true Christian name was "Elijah." For years, he had been a Christian and he hoped to die one. "My white neighbors and friends know my character as a citizen and a man. I am at peace with every one, whites and Indians. I am getting to be an old man, but I am still able to work. I am poor, but I manage to get along." He lived his final years in peace at Granite Falls, Minn.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Your Hero is Not Untouchable Pt 2

Your Hero is Not Untouchable

A Monuments Study: Dakota War of 1862 Memorials, Monuments and Markers

by Rye Purvis 7/3/2020

(T.C. Cannon, Kiowa, painting “Andrew Myrick - Let Em Eat Grass” 1970)

On December 26th, 1862 38 Dakota prisoners of war were executed in Mankato, Minnesota. This was to mark an ending (though not an end to the suffering of the Dakota peoples) to the Dakota War of 1862, a war that began just months earlier in the Fall of ’62. The 38 men were ordered to be executed under the order of Abraham Lincoln, after Lincoln’s examined 303 war trials conducted from September to November of ’62 in Minnesota:

“The trials of the Dakota prisoners were deficient in many ways, even by military standards; and the officers who oversaw them did not conduct them according to military law. The hundreds of trials commenced on 28 September 1862 and were completed on 3 November; some lasted less than 5 minutes. No one explained the proceedings to the defendants, nor were the Sioux represented by defense attorneys. "The Dakota were tried, not in a state or federal criminal court, but before a military commission. They were convicted, not for the crime of murder, but for killings committed in warfare. The official review was conducted, not by an appellate court, but by the President of the United States. Many wars took place between Americans and members of the Indian nations, but in no others did the United States apply criminal sanctions to punish those defeated in war." The trials were also conducted in an atmosphere of extreme racist hostility towards the defendants expressed by the citizenry, the elected officials of the state of Minnesota and by the men conducting the trials themselves. "By November 3, the last day of the trials, the Commission had tried 392 Dakota, with as many as 42 tried in a single day." Not surprisingly, given the socially explosive conditions under which the trials took place, by the 10th of November the verdicts were in, and it was announced to the nation and the world that 303 Sioux prisoners had been convicted of murder and rape by the military commission and sentenced to death.” 1

Lincoln reviewed all transcripts from the rushed trials and made his decision on the final execution in under a month. The public execution remains the largest mass execution in American history. Today a public park remains at the site of the execution, named “Reconciliation Park” and given the theme “Forgive Everyone Everything.” 2 Merriam-Webster’s lists its dictionary definition of reconciliation as “the act of causing two people or groups to become friendly again after an argument or disagreement.”

It Starts with Treaties

To provide context to the Dakota War of 1862 is to acknowledge a trail of once again broken treaties and a US hunger for land acquisition. Before colonial interactions, the Great Sioux Nation covered present-day northern Minnesota and Wisconsin. The ancestors of the Sioux “arrived in the Northwoods of central Minnesota and northwestern Wisconsin from the Central Mississippi River shortly before 800 AD.” 3 Under the Great Sioux Nation are three subdivision groups: The Lakota (Northern Lakota, Central Lakota and Southern Lakota), Western Dakota (Yankton, Yanktonai) and the Eastern Dakota (Santee, Sisseton). It wasn’t until the early 1800’s that the Dakota, of the Sioux Nation, signed a treaty with the US in order to establish US Military posts in Minnesota and open trading for the Dakota. Soon after, the 1825 Treaty of Prarie du Chien and the 1830 Fourth Treaty of Prarie du Chien were put into place to cede more land to the American government. Another 1858 Treaty established the Yankton Sioux Reservation for the Yankton Western Dakota peoples, a treaty that ultimately moved the band from “eleven and a half million acres” to a “475,000 acre reservation.”11 The US created the Territory of Minnesota in 1849, thus placing even more pressure on the Sioux to concede land. More treaties followed with the 1851 Treaty of Mendota and the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux. In both deals, 21 million acres were ceded to the US by the Sisseton and Wahpeton bands of the Dakota in exchange for $1,665,000. “However, the American government kept more than 80% of the funds with only the interest (5% for 50 years) being paid to the Dakota” 4

The US’s aim ultimately was to force the Sioux out of Minnesota. Minnesota, established as a state on May 11, 1858 had two temporary reservations set up along the Minnesota River, one for the Upper Sioux Agency and one for the Lower Sioux Agency. Relocation and displacement from land once used for hunting created even more tension with delayed treaty payments causing economic suffering and starvation. Treaties promised payments to the Sioux, payments that were used for foods but at that point but were often late due to the US’s focus on the Civil War. Trader store operators many times charged credit to the Upper and Lower Sioux Agency’s, collecting the annuity allotments directly from the government in return.

Let them eat grass

Having owned stores in both the Upper and Lower Sioux Agency at the time, trader Andrew J Myrick eventually refused to sell food on credit to the Dakota during the summer of 1862. That summer saw additional hardship with failed crops in the previous year on top of late federal payments. In response to his refusal to allot food, Myrick was quoted as “allegedly” saying “Let them eat grass” a quote that is oftentimes disputed. Around the same time as this disputed quote, on August 17, 1862 a few Santee men of the Whapeton band killed a white farmer and part of his family, thus starting the beginning of the Dakota War of 1862.

This is where we in the 21st century have to take a pause. Most of the written accounts of the start of the war or the “murderous violence” of the “Murdering Indians” 5 (a quote from Peter G Beidler’s “Murdering Indians”) were accounts from the side of the colonizers. When researching the Dakota War of 1862, perspectives from the Dakota are not common. At some point the basis for war warrants a question of American mythology. In researching about this white farmer debacle, the killing is in one instance described as coming from “an argument between two young Santee men over the courage to steal eggs from a white farmer became a dare to kill.”6 In another account, the story follows the same narrative about the farmer’s eggs: “Upon seeing some chicken eggs in a nest at the farm of a white settler, there was a disagreement whether or not to take the eggs. When one refused, his companion dared him to prove that he was not afraid of the white man's reaction.”7 I bring up the eggs incident not to stress on this sliver of historical mythology but to emphasize the instability of perspective in historical accounts. Anti-Indian perspectives and a notion of eradication of the “Indian” has been profound in the beginning in the colonization of the US. For a war to rest on the stolen eggs of a farmer, and the killing of 5 individuals doesn’t take into account the broken down persons that were driven to get to the point of having to steal eggs nor what exactly occurred between the farmer and the men.

After the incident, however it occurred, Mdewakanton Dakota leader Little Crow led a group against the American settlements waging war as a means to remove the white settlers. Little Crow as he is known in European mistranslations, name was actually Thaóyate Dúta meaning “His Red Nation”. He was instrumental in leading discussions in the treaties, providing a voice for his people, and leading Dakota in the Battle of Birch Coulee. In a letter to Henry Sibley, the first Governor of the US State of Minnesota, on September 7, 1862, Thaóyate described the context for the uprising:

“Dear Sir – For what reason we have commenced this war I will tell you. it is on account of Maj. Galbrait [sic] we made a treaty with the Government a big for what little we do get and then cant get it till our children was dieing with hunger – it is with the traders that commence Mr A[ndrew] J Myrick told the Indians that they would eat grass or their own dung. Then Mr [William] Forbes told the lower Sioux that [they] were not men [,] then [Louis] Robert he was working with his friends how to defraud us of our money, if the young braves have push the white men I have done this myself." 8

Famine, broken treaties, late payments from the government were but a few of the motivating factors for driving change. The killing of the five white settlers by the 5 Santee men prompted a motion of action led by then natural leader Thaóyate.

When the war neared an end, Thaóyate and other Dakota warriors escaped. It wasn’t until July 3 of 1863 that Thaóyate was shot by 2 settlers and mortally wounded. Upon his death, Thaóyate’s body was mutilated and his remains were withheld from both family and his tribe until 1971 when the Minnesota Historical Society returned his remains to Thaóyate’s grandson. A historical marker remains where Thaóyate’s life was taken:

“[The] marker, erected in 1929 at the spot where Chief Little Crow (who escaped the hanging) was shot, glorifies the chief’s killer: “Chief Little Crow, leader of the Sioux Indian outbreak in 1862, was shot and killed about 330 feet from this point by Nathan Lamson and his son Chauncey July 3, 1863.” The marker does not mention that Little Crow’s body was mutilated, that his scalp was donated to the Minnesota Historical Society and put on display at the State Capitol. He would not be buried until 1971.” 9

Marker of where Little Crow was shot (photo by Sheila Regan)

I just want to acknowledge, that there is a lot of information to unpack that occurred during the Dakota War of 1862, and I don’t want to pretend that this article can sum up every occurrence, battle or person involved. Author and non-Native Gary Clayton Anderson wrote “Through Dakota Eyes” in 1988, and though not perfect, it provides eyewitness accounts from various Dakota peoples perspectives that is worth noting. The Minnesota Historical Society, though known for its problematic history holding on to Thaóyate’s body, also provides more information on its website regarding oral traditions, resources, publications and more in regards to the Dakota War of 1862. I encourage those interested in diving deeper into information to seek out more while simultaneously questioning the source of the information.

Stolen Bodies

Before Thaóyate’s death, the 38 Dakota men were hung at Mankato under Lincoln’s orders. An additional 2 men by the name of Shakpe and Wakanozanzan who had been captured were also executed on November 11th, 1865 under the order of Andrew Johnson. But this mass execution was not the end of the US’s threat to eradicate the Sioux. After the mass execution, “277 male members of the Sioux tribe, 16 women and two children and one member of the Ho-Chunk tribe”1 were sent to a prison camp at Camp McClellan from April 25, 1863 to April 10, 1866. The prisoners who did not survive Camp McClellan were buried in unmarked graves, later dug up and their skulls used by scientists at the Putnam Museum in the late 1870’s. The 23 skulls were given to the Dakota tribe and not until 2005 was a proper memorial ceremony held for the Dakota prisoners.

In addition, 1600 Dakota women, children and old men were forced into internment camps at Pike Island. Wita Tanka, the Dakota name for Pike Island, is now part of Fort Snelling State Park.

“During this time, more than 1600 Dakota women, children and old men were held in an internment camp on Pike Island, near Fort Snelling, Minnesota. Living conditions and sanitation were poor, and infectious disease struck the camp, killing more than three hundred.[37] In April 1863, the U.S. Congress abolished the reservation, declared all previous treaties with the Dakota null and void, and undertook proceedings to expel the Dakota people entirely from Minnesota. To this end, a bounty of $25 per scalp was placed on any Dakota found free within the boundaries of the state.[38] The only exception to this legislation applied to 208 Mdewakanton, who had remained neutral or assisted white settlers in the conflict."1

Where does this leave us?

The year was 1990 and a 36-year old Cheyenne and Arapaho artist by the name of Hock E Aye VI Edgar Heap of Birds had just finished an installation along the Mississippi River in Downtown Minneapolis titled “Building Minnesota.” The installation featured 40 white metal signs containing the names of the 38 men executed under the order of Abraham Lincoln, and the 2 men executed under the order of Andrew Johnson. Heap of Birds explained, “‘Not everyone loved the piece. Heap of Birds says that he received criticism because of the negative portrayal of Abraham Lincoln. ‘They thought it was a betrayal,’”9 Beyond that, the installation came to be known as a space for healing, mourning, for acknowledgement of the lost men, and a place for community to gather.

(One of the 38+2 Signs by Edgar Heap of Birds, photo from Met Museum)

Two monuments were placed up in 1987 and in 2012 at Reconciliation Park in Monkato, MN. The ‘87 monument named “Winter Warrior” features a Dakota warrior figure made by a local artist and the 2012 monument features a large scroll with poems, prayers, and the list of all the men killed on that dark day of 1862.

Beyond that, Minnesota boasts a plethora of statues, monuments and memorials under the umbrella of the Dakota War of 1862. Fort Ridgely State Park located near Fairfax MN hosts a number of monuments, Wood Lake State Monument, Camp Release State Monument, Defenders State Monument are a few of the myriad of locations dedicated to the Americans who fought, lost their lives as well as civilian causality acknowledgement.

Located in Morton, MN, the Birch Coulee monument was erected in 1894. Close to this monument a granite obelisk was erected five years later titled the “Loyal Indian Monument,” to honor the 6 Dakota “who saved the lives of whites during the U.S. Dakota War.” This monument stood out to me, not so much for its bland appearance, but the unusual circumstance to highlight six “loyal” Native lives amongst the many lost who were seen as disloyal.

Seth Eastman, a descendant of Little Thunder (one of the 38 men executed in Mankato) shared how “one public school at the border of Minnesota, where a man dressed as Abraham Lincoln talked to the students and answered their questions [and one] of my nephews asked the question, ‘Why did you hang the 38?’ This man went on to tell him, ‘Oh, I only hung the bad Indians. The ones that killed and raped.’ Telling kids this, that we’re bad, it’s the same as how we’ve been portrayed in the media. That struck my core.””

He continued:

“Minnesota has its own memorials for the Dakota War, but some of the older ones especially are quite problematic. These markers paint the settlers who fought the Dakota as brave victims who defended themselves, without discussion of the broken treaties and ill treatment the Dakota endured which prompted the war; neither is there any mention of the mass execution, internment, and forced removal that followed.”9

Director and Founder of Smooth Feather productions Silas Hagerty released the documentary Dakota 38 in 2012. The documentary highlights a yearly journey where riders from across the world meet in Lower Brule, South Dakota to take a 330-mile journey to Mankato as part of a commemoration and ceremony of remembrance for the 38 lost in 1862. The film also delves into bits of history on the attempts the US took to remove the Dakota peoples from Minnesota. Jim Miller, a direct descendant of Little Horse (one of the 38 men) started the annual ride in 2005 as “a way to promote reconciliation between American Indians and non-Native people. Other goals of the Memorial Ride include: provide healing from historical trauma; remember and honor the 38 + 2 who were hanged; bring awareness of Dakota history and to promote youth rides and healing.”10

(Dakota Riders Ceremonial ride to Mankota, Photo by Sarah Penman)

The memorials and monuments are in abundance in regards to the Dakota War. But who’s perspective is acknowledged? Through work such as Edgar Heap of Birds in his 1990′s installation, to the 2012 larger public scroll monument in Mankato’s “Reconciliation Park” there have been steps taken by both Native and non-natives to explore what this reconciliation looks like.

Of the two Dakota men captured and ordered to be executed under then US president Andrew Johnson on November 11, 1865, Wakanozanzan of the Mdeqakanton Dakota Sioux Nation’s final words were:

“I am a common human being. Some day, the people will come from the heart and look at each other as common human beings. When they do that, come from the heart, this country will be a good place.”12

This article is dedicated to the 38+2.

-------

Images Sources Andrew Myrick – Let Em Eat Grass 1970 TC Cannon, Google Arts & Culture https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/andrew-myrick-let-em-eat-grass-t-c-cannon-kiowa-and-caddo-southern-plains-indian-museum/uwGyR0PTzacQkA

Met Museum photo of Edgar Heap of Birds artwork https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/653721

Mankota riders https://nativenewsonline.net/currents/dakota-382-wokiksuye-memorial-riders-commemorate-1862-hangings-ordered-lincoln/

Sources

1 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dakota_War_of_1862 2 https://www.mankatolife.com/attractions/reconciliation-park/ 3 Gibbon, Guy The Sioux: The Dakota and the Lakota Nations https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Sioux.html?id=s3gndFhmj9gC 4 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sioux 5 Beidler, Peter G. “Murdering Indians” October 17, 2013 https://books.google.com/books?id=4RRzAQAAQBAJ&dq=santee+men+murdered+white+farmer 6 History of the Santee Sioux Tribe in Nebraska http://www.santeedakota.org/santee_history_ii.htm 7 https://www.usdakotawar.org/history/acton-incident 8 Little Crow’s Letter https://www.usdakotawar.org/history/taoyateduta-little-crow 9 Regan, Sheila June 16, 2017 “In Minnesota, Listening to Native Perspective on Memorializing the Dakota War” Hyperallergic https://hyperallergic.com/385682/in-minnesota-listening-to-native-perspectives-on-memorializing-the-dakota-war/ 10 https://nativenewsonline.net/currents/dakota-382-wokiksuye-memorial-riders-commemorate-1862-hangings-ordered-lincoln/

11 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yankton_Sioux_Tribe

12 https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/64427183/wakan_ozanzan-medicine_bottle

Monuments Depicting Victims of the Dakota Uprising http://www.dakotavictims1862.com/monuments/index.html Morton, MN Monuments https://sites.google.com/site/mnvhlc/home/renville-county/morton-monuments

More information regarding Dakota War of 1862 Holocaust and Genocide Studies: Native American University of Minnesota https://cla.umn.edu/chgs/holocaust-genocide-education/resource-guides/native-american

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

While most Americans have never heard of The Dakota War or the injustices that led to the largest execution in American history, I’ve known about it my entire life. I am a member of the Oceti Sakowin (The Great Sioux Nation). Natives and non-Natives alike whisper legends about us.

It’s hard for them to accept what was done to us, and that they’ve directly benefited from such grievous wrongdoing.

My ancestors’ pictures are in history books. As a small child, I would see their photos at the Crazy Horse Memorial in the Black Hills of South Dakota. You see, I am a descendant of Wabasha, a hereditary Mdewakanton Dakota Chief who, along with other Dakota like Little Crow, led the people during our war with the United States. After the conflict, he was exiled from his Minnesota homelands to the Crow Creek Sioux Reservation in central South Dakota.

When I first tell non-Natives about the Dakota War, especially in the northern plains, there’s a lot of cognitive dissonance. It’s hard for them to accept what was done to us, and that they’ve directly benefited from such grievous wrongdoing.

What Happened

The Dakota War was a direct result of the United States breaking its own laws.

In 1851, Dakota leaders signed the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux and the Treaty of Mendota with the United States. Dakota ceded land in Minnesota to the U.S. in exchange for money, goods, and services

According to the U.S. Constitution, treaties are the supreme law of the land; yet, the United States Congress unilaterally breached these treaties with the Dakota. Unbeknownst to the Dakota, the U.S. eliminated Article 3 of each treaty, which set up reservation land for the Dakota to live on. The government also defaulted on payments to the Dakota, or gave their money directly to traders who were supposed to supply the Dakota with rations. These traders were often corrupt.

We still sing the song the Dakota sang that day.

While some Dakota remained peaceful, others began to defy the government to survive. Four young warriors stole eggs and killed five settlers in the process. All-out war began when they were protected by their village.

The Dakota War raged on for about six weeks, throughout August and September of 1862. Afterwards, 392 Dakota were taken prisoner and tried based on little or no evidence. Proceedings were held in a foreign language — English. The Court also failed to recognize the defendants’ status as members of a sovereign nation.

Treaty breaches were not discussed.

Continue On ...

Phroyd

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 things to do in Mankato MN with kids

Mankato is a city with lots of entertainment venues in it. Whether it's a place of entertainment with your family, partner, or children. So, if you are with small children, there are several things to do in Mankato MN with kids.

Sibley Farm Park

In Mankato with kids in tow, you absolutely must make a stop at Sibley Farm Park. Goats, alpacas, calves, peacocks, horses, lambs, and chicks call the big red barn home. If you're brave enough to visit, you'll want to spend the afternoon tasting the meats from pasture-raised pigs, talking with the animals, and enjoying the nice outdoor grounds. Sibley does not take reservations.

Hubbard House

My kids have yet to show signs of inheriting their mom’s intrigue with historic homes. The Hubbard Houses sympathizes with families such as mine by offering kid-friendly programming into the mix of tours that focus on architecture and the life of a milling magnate.

Visitors can walk through two ghostly wooded areas, such as the "Spirit's Room" or the "Sparkling Room" (yes, spelled that way), look into the fireplace and see fireflies in full color, and experience a fire-making experience inside a "firepit," a hard-working oven-turned-fireplace that was adapted to using firewood. We've heard the story of the ghost of a miller who would stage battles by hanging from a red hot bar across the street from the Hubbard House and pound on doors.

Minnesota River Trail

Brought the bikes along? Jump onto the paved Minnesota River Trail at one of Mankato’s parks (Sibley Park, Riverfront Park – both offer parking lots) and hug the namesake river along the western end of the city. Also, the continuous bicycle training ride along the trail would be an excellent way to hone your bicycle riding skills before venturing out on your own for your first time riding in the outdoors.

It is not advisable to do the 9-mile ride without a partner or a safe ride companion; however, as this is an urban/urban hybrid, the ride would still qualify as a group ride. If you are not a cyclist, please plan on riding with a group, or all the more than one.

Treaty Site History Center

Sneak in another history lesson on a side trip to St Peter, a 15-minute drive north of Mankato. While learning about the 1851 Treaty of Traverse des Sioux and its impact on the local Dakota people, junior historians get hands-on with educational exhibits disguised as play.

In addition to reenacting some Sioux missions, kids dig through railroad cars to find artifacts in the lot of the former wooden brewery that was established by the Dakota and Oklahoma Oil Co. This includes an exhibit of photos documenting the trauma endured by Dakota kids during their relocation to Oklahoma after the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux. The site has a very informative pamphlet that details several of the many Dakota Massacre-related events.

Jake's Pizza

Jake’s is our pick for the best pizza joint between the Twin Cities and Mankato. Their Bianco margarita pizza has a medium crust and has the ingredients that make a good pizza. We found our usual healthy version to be too bready, but their celery and mushroom cheddar pizzas with pepperoni are definitely worth a shot.

0 notes

Photo

Little Crow was the chief of the Mdewakanton Dakota people. He had a role in negotiating the Treaties of the Traverse des Sioux and Mendota of 1851, where he agreed to move his tribe in exchange for good, annuities, and certain rights. The government reneged on its treaty and Little Crow was forced to support the decision of the Dakota War Council in 1862. Little Crow was in many battles and was injured by cannon fire in an attack on Fort Ridgely. Little Crow later fled west taking three white boys captive. One of the boys was George Washington Ingalls, age 9, cousin of the writer Laura Ingalls Wilder. The boys were ransomed off for blankets and horses at the Canadian border.

On July 3, 1863, Little Crow was fatally wounded in a fight that began with some settlers while he and his son were picking raspberries in Minnesota. He was scalped and his body dragged down the Main Street of Hutchinson on the Fourth of July. They put firecrackers in his ears and nose, then his mutilated body was thrown into a slaughterhouse pit. His head was removed. His killer, Nathan Lamson, was awarded $500 for "rendering great service to the state". His son, Chauncy Lamson, got a $75 bounty for the scalp.

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Little_Crow)

#little crow#dakota tribe#history#19th century#America#fourth of july#treaties of the traverse des sioux and mendota

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Largest Mass Execution in US History (1862)

The Dakota War of 1862, also known as the Sioux Uprising, (and the Dakota Uprising, the Sioux Outbreak of 1862, the Dakota Conflict, the U.S.–Dakota War of 1862 or Little Crow's War) was an armed conflict between the United States and several bands of the eastern Sioux (also known as eastern Dakota). It began on August 17, 1862, along the Minnesota River in southwest Minnesota. It ended with a mass execution of 38 Dakota men on December 26, 1862, in Mankato, Minnesota.

Throughout the late 1850s, treaty violations by the United States and late or unfair annuity payments by Indian agents caused increasing hunger and hardship among the Dakota. Traders with the Dakota previously had demanded that the government give the annuity payments directly to them (introducing the possibility of unfair dealing between the agents and the traders to the exclusion of the Dakota). In mid-1862 the Dakota demanded the annuities directly from their agent, Thomas J. Galbraith. The traders refused to provide any more supplies on credit under those conditions, and negotiations reached an impasse.[3]

On August 17, 1862, one young Dakota with a hunting party of three others killed five settlers while on a hunting expedition. That night a council of Dakota decided to attack settlements throughout the Minnesota River valley to try to drive whites out of the area. There has never been an official report on the number of settlers killed, although figures as high as 800 have been cited.

Over the next several months, continued battles pitting the Dakota against settlers and later, the United States Army, ended with the surrender of most of the Dakota bands.[4] By late December 1862, soldiers had taken captive more than a thousand Dakota, who were interned in jails in Minnesota. After trials and sentencing, 38 Dakota were hanged on December 26, 1862, in the largest one-day execution in American history. In April 1863, the rest of the Dakota were expelled from Minnesota to Nebraska and South Dakota. The United States Congress abolished their reservations.

Background

Previous treaties

The United States and Dakota leaders negotiated the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux[5] on July 23, 1851, and Treaty of Mendota on August 5, 1851, by which the Dakota were forced to cede large tracts of land in Minnesota Territory to the U.S. In exchange for money and goods, the Dakota were forced to agree to live on a 20-mile (32 km) wide Indian reservation centered on a 150 mile (240 km) stretch of the upper Minnesota River.

However, the United States Senate deleted Article 3 of each treaty, which set out reservations, during the ratification process. Much of the promised compensation never arrived, was lost, or was effectively stolen due to corruption in the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Also, annuity payments guaranteed to the Dakota often were provided directly to traders instead (to pay off debts which the Dakota incurred with the traders).

Encroachments on Dakota lands

Little Crow, Dakota chief

When Minnesota became a state on May 11, 1858, representatives of several Dakota bands led by Little Crow traveled to Washington, D.C., to negotiate about enforcing existing treaties. The northern half of the reservation along the Minnesota River was lost, and rights to the quarry at Pipestone, Minnesota, were also taken from the Dakota. This was a major blow to the standing of Little Crow in the Dakota community.

The land was divided into townships and plots for settlement. Logging and agriculture on these plots eliminated surrounding forests and prairies, which interrupted the Dakota's annual cycle of farming, hunting, fishing and gathering wild rice. Hunting by settlers dramatically reduced wild game, such as bison, elk, whitetail deer and bear. Not only did this decrease the meat available for the Dakota in southern and western Minnesota, but it directly reduced their ability to sell furs to traders for additional supplies.

Although payments were guaranteed, the US government was often behind or failed to pay because of Federal preoccupation with the American Civil War. Most land in the river valley was not arable, and hunting could no longer support the Dakota community. The Dakota became increasingly discontented over their losses: land, non-payment of annuities, past broken treaties, plus food shortages and famine following crop failure. Tensions increased through the summer of 1862.

Breakdown of negotiations

On August 4, 1862, representatives of the northern Sissetowan and Wahpeton Dakota bands met at the Upper Sioux Agency in the northwestern part of the reservation and successfully negotiated to obtain food. When two other bands of the Dakota, the southern Mdewakanton and the Wahpekute, turned to the Lower Sioux Agency for supplies on August 15, 1862, they were rejected. Indian Agent (and Minnesota State Senator) Thomas Galbraith managed the area and would not distribute food to these bands without payment.

At a meeting of the Dakota, the U.S. government and local traders, the Dakota representatives asked the representative of the government traders, Andrew Jackson Myrick, to sell them food on credit. His response was said to be, "So far as I am concerned, if they are hungry let them eat grass or their own dung." [6] But the importance of Myrick's comment at the time, early August 1862, is historically unclear. When Gregory Michno shared the top 10 myths on the Dakota Uprising in True West Magazine, he stated that this statement did not incite the uprising: "An interpreter’s daughter first mentioned it 57 years after the event. Since then, however, the claim that this incited the Dakotas to revolt has proliferated as truth in virtually every subsequent retelling. Like so much of our history, unfortunately, repetition is equated with accuracy." [7] Another telling is that Myrick's was referring the Native American women who were already combing the floor of the fort's stables for any unprocessed oats to then feed to their starving children along with a little grass. Myrick was later found dead with grass stuffed in his mouth.[8]

War

Early fighting

On August 16, 1862, the treaty payments to the Dakota arrived in St. Paul, Minnesota, and were brought to Fort Ridgely the next day. They arrived too late to prevent violence. On August 17, 1862, four young Dakota men were on a hunting trip in Acton Township, Minnesota, during which one stole eggs and then killed five white settlers.[9] Soon after, a Dakota war council was convened and their leader, Little Crow, agreed to continue attacks on the European-American settlements to try to drive out the whites.

On August 18, 1862, Little Crow led a group that attacked the Lower Sioux (or Redwood) Agency. Andrew Myrick was among the first who were killed.[citation needed] He was discovered trying to escape through a second-floor window of a building at the agency. Myrick's body later was found with grass stuffed into his mouth. The warriors burned the buildings at the Lower Sioux Agency, giving enough time for settlers to escape across the river at Redwood Ferry. Minnesota militia forces and B Company of the 5th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment sent to quell the uprising were defeated at the Battle of Redwood Ferry. Twenty-four soldiers, including the party's commander (Captain John Marsh), were killed in the battle.[citation needed] Throughout the day, Dakota war parties swept the Minnesota River Valley and near vicinity, killing many settlers. Numerous settlements including the Townships of Milford, Leavenworth and Sacred Heart, were surrounded and burned and their populations nearly exterminated.

Early Dakota offensives

1912 lithograph depicting the 1862 Battle of Birch Coulee, by Paul G. Biersach (1845-1927)

Confident with their initial success, the Dakota continued their offensive and attacked the settlement of New Ulm, Minnesota, on August 19, 1862, and again on August 23, 1862. Dakota warriors initially decided not to attack the heavily defended Fort Ridgely along the river. They turned toward the town, killing settlers along the way. By the time New Ulm was attacked, residents had organized defenses in the town center and were able to keep the Dakota at bay during the brief siege. Dakota warriors penetrated parts of the defenses enough to burn much of the town.[10] By that evening, a thunderstorm dampened the warfare, preventing further Dakota attacks.

Regular soldiers and militia from nearby towns (including two companies of the 5th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry then stationed at Fort Ridgely) reinforced New Ulm. Residents continued to build barricades around the town.

During this period, the Dakota attacked Fort Ridgely on August 20 and 22, 1862.[11][12] Although the Dakota were not able to take the fort, they ambushed a relief party from the fort to New Ulm on August 21. The defense at the Battle of Fort Ridgely further limited the ability of the American forces to aid outlying settlements. The Dakota raided farms and small settlements throughout south central Minnesota and what was then eastern Dakota Territory.

Minnesota militia counterattacks resulted in a major defeat of American forces at the Battle of Birch Coulee on September 2, 1862. The battle began when the Dakota attacked a detachment of 150 American soldiers at Birch Coulee, 16 miles (26 km) from Fort Ridgely. The detachment had been sent out to find survivors, bury American dead and report on the location of Dakota fighters. A three-hour firefight began with an early morning assault. Thirteen soldiers were killed and 47 were wounded, while only two Dakota were killed. A column of 240 soldiers from Fort Ridgely relieved the detachment at Birch Coulee the same afternoon.

Attacks in northern Minnesota

Settlers escaping the violence, 1862.

Farther north, the Dakota attacked several unfortified stagecoach stops and river crossings along the Red River Trails, a settled trade route between Fort Garry (now Winnipeg, Manitoba) and Saint Paul, Minnesota, in the Red River Valley in northwestern Minnesota and eastern Dakota Territory. Many settlers and employees of the Hudson's Bay Company and other local enterprises in this sparsely populated country took refuge in Fort Abercrombie, located in a bend of the Red River of the North about 25 miles (40 km) south of present-day Fargo, North Dakota. Between late August and late September, the Dakota launched several attacks on Fort Abercrombie; all were repelled by its defenders.

In the meantime steamboat and flatboat trade on the Red River came to a halt. Mail carriers, stage drivers and military couriers were killed while attempting to reach settlements such as Pembina, North Dakota, Fort Garry, St. Cloud, Minnesota, and Fort Snelling. Eventually the garrison at Fort Abercrombie was relieved by a U.S. Army company from Fort Snelling, and the civilian refugees were removed to St. Cloud.

Army reinforcements

Due to the demands of the American Civil War, the region's representatives had to repeatedly appeal for aid before Pres. Abraham Lincoln formed the Department of the Northwest on September 6, 1862, and appointed Gen. John Pope to command it with orders to quell the violence. He led troops from the 3rd Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment and 4th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment. The 9th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment and 10th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment, which were still being constituted, had troops dispatched to the front as soon as Companies were formed.[13][14] Minnesota Gov. Alexander Ramsey also enlisted the help of Col. Henry Hastings Sibley (the previous governor) to aid in the effort.

After the arrival of a larger army force, the final large-scale fighting took place at the Battle of Wood Lake on September 23, 1862. According to the official report of Lt. Col. William R. Marshall of the 7th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment, elements of the 7th Minnesota and the 6th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment (and a six-pounder cannon) were deployed equally in dugouts and in a skirmish line. After brief fighting, the forces in the skirmish line charged against the Dakota (then in a ravine) and defeated them overwhelmingly.

Among the Citizen Soldier units in Sibley's expedition:

Captain Joseph F. Bean's Company "The Eureka Squad"

Captain David D. Lloyd's Company

Captain Calvin Potter's Company of Mounted Men

Captain Mark Hendrick's Battery of Light Artillery

1st Lt Christopher Hansen's Company "Cedar Valley Rangers" of the 5th Iowa State Militia, Mitchell Co, Iowa

elements of the 5th & 6th Iowa State Militia

Iowa Northern Border Brigade

In Iowa alarm over the Santee attacks led to the construction of a line of forts from Sioux City to Iowa Lake. The region had already been militarized because of the Spirit Lake Massacre in 1857. After the 1862 conflict began, the Iowa Legislature authorized “not less than 500 mounted men from the frontier counties at the earliest possible moment, and to be stationed where most needed”, although this number was soon reduced. Although no fighting took place in Iowa, the Dakota uprising led to the rapid expulsion of the few unassimilated Native Americans left there.[15][16]

Surrender of the Dakota

Most Dakota fighters surrendered shortly after the Battle of Wood Lake at Camp Release on September 26, 1862. The place was so named because it was the site where the Dakota released 269 European-American captives to the troops commanded by Col. Henry Sibley. The captives included 162 "mixed-bloods" (mixed-race, some likely descendants of Dakota women who were mistakenly counted as captives) and 107 whites, mostly women and children. Most of the warriors were imprisoned before Sibley arrived at Camp Release.[17]:249 The surrendered Dakota warriors were held until military trials took place in November 1862. Of the 498 trials, 300 were sentenced to death though the president commuted all but 38.[18]

Little Crow was forced to retreat sometime in September 1862. He stayed briefly in Canada but soon returned to the Minnesota area. He was killed on July 3, 1863, near Hutchinson, Minnesota, while gathering raspberries with his teenage son. The pair had wandered onto the land of white settler Nathan Lamson, who shot at them to collect bounties. Once it was discovered that the body was of Little Crow, his skull and scalp were put on display in St. Paul, Minnesota. The city held the trophies until 1971, when it returned the remains to Little Crow's grandson. For killing Little Crow, the state granted Lamson an additional $500 bounty. For his part in the warfare, Little Crow's son was sentenced to death by a military tribunal, a sentence then commuted to a prison term.

Trials

In early December, 303 Sioux prisoners were convicted of murder and rape by military tribunals and sentenced to death. Some trials lasted less than 5 minutes. No one explained the proceedings to the defendants, nor were the Sioux represented by a defense in court. Pres. Abraham Lincoln personally reviewed the trial records to distinguish between those who had engaged in warfare against the U.S., versus those who had committed crimes of rape and murder against civilians.

Henry Whipple, the Episcopal bishop of Minnesota and a reformer of U.S. policies toward Native Americans, first wrote an open letter and then went to Washington DC in the Fall of 1862 to urge Lincoln to proceed with leniency.[19] On the other hand, General Pope and Minnesota Senator Morton S. Wilkinson told him that leniency would not be received well by the white population. Governor Ramsey warned Lincoln that, unless all 303 Sioux were executed, "[P]rivate revenge would on all this border take the place of official judgment on these Indians."[20] In the end, Lincoln commuted the death sentences of 264 prisoners, but he allowed the execution of 38 men.

This clemency resulted in protests from Minnesota, which persisted until the Secretary of the Interior offered white Minnesotans "reasonable compensation for the depredations committed." Republicans did not fare as well in Minnesota in the 1864 election as they had before. Ramsey (by then a senator) informed Lincoln that more hangings would have resulted in a larger electoral majority. The President reportedly replied, "I could not afford to hang men for votes."[21]

Execution

One of the 39 condemned prisoners was granted a reprieve.[17]:252-259[22] The Army executed the 38 remaining prisoners by hanging on December 26, 1862, in Mankato, Minnesota. It remains the largest mass execution in American history.

Drawing of the 1862 mass hanging in Mankato, Minnesota.

Wa-kan-o-zhan-zhan (Medicine Bottle)

The mass execution was performed publicly on a single scaffold platform. After regimental surgeons pronounced the prisoners dead, they were buried en masse in a trench in the sand of the riverbank. Before they were buried, an unknown person nicknamed “Dr. Sheardown” possibly removed some of the prisoners' skin.[23] Small boxes purportedly containing the skin later were sold in Mankato.

At least two Sioux leaders, Little Six and Medicine Bottle, escaped to Canada. They were captured, drugged and returned to the United States. They were hanged at Fort Snelling in 1865.[24]

Medical aftermath

Because of high demand for cadavers for anatomical study, several doctors wanted to obtain the bodies after the execution. The grave was reopened in the night and the bodies were distributed among the doctors, a practice common in the era. The doctor who received the body of Mahpiya Okinajin (He Who Stands in Clouds), also known as "Cut Nose", was William Worrall Mayo.

Mayo brought the body of Mahpiya Okinajin to Le Sueur, Minnesota, where he dissected it in the presence of medical colleagues.[25]:77-78 Afterward, he had the skeleton cleaned, dried and varnished. Mayo kept it in an iron kettle in his home office. His sons received their first lessons in osteology from this skeleton[25]:167 In the late 20th century, the identifiable remains of Mahpiya Okinajin and other Native Americans were returned by the Mayo Clinic to a Dakota tribe for reburial per the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.[26]

Internment

The remaining convicted Indians stayed in prison that winter. The following spring they were transferred to Camp McClellan in Davenport, Iowa,[27] where they were held in prison for almost four years. By the time of their release, one third of the prisoners had died of disease. The survivors were sent with their families to Nebraska. Their families had already been expelled from Minnesota.

Pike Island internment

Dakota internment camp, Fort Snelling, winter 1862

Little Crow's wife and two children at Fort Snelling prison compound, 1864

During this time, more than 1600 Dakota women, children and old men were held in an internment camp on Pike Island, near Fort Snelling, Minnesota. Living conditions and sanitation were poor, and infectious disease struck the camp, killing more than three hundred.[28] In April 1863 the U.S. Congress abolished the reservation, declared all previous treaties with the Dakota null and void, and undertook proceedings to expel the Dakota people entirely from Minnesota. To this end, a bounty of $25 per scalp was placed on any Dakota found free within the boundaries of the state.[citation needed] The only exception to this legislation applied to 208 Mdewakanton, who remained neutral or assisted white settlers in the conflict.

In May 1863 Dakota survivors were forced aboard steamboats and relocated to the Crow Creek Reservation, in the southeastern Dakota Territory, a place stricken by drought at the time. Many of the survivors of Crow Creek moved three years later to the Niobrara Reservation in Nebraska.[29][30]

Firsthand accounts

There are numerous firsthand accounts of the wars and raids. For example, the compilation by Charles Bryant, titled Indian Massacre in Minnesota, included these graphic descriptions of events, taken from an interview with Mrs. Justina Krieger:

"Mr. Massipost had two daughters, young ladies, intelligent and accomplished. These the savages murdered most brutally. The head of one of them was afterward found, severed from the body, attached to a fish-hook, and hung upon a nail. His son, a young man of twenty-four years, was also killed. Mr. Massipost and a son of eight years escaped to New Ulm."[31]:141

"The daughter of Mr. Schwandt, enceinte [pregnant], was cut open, as was learned afterward, the child taken alive from the mother, and nailed to a tree. The son of Mr. Schwandt, aged thirteen years, who had been beaten by the Indians, until dead, as was supposed, was present, and saw the entire tragedy. He saw the child taken alive from the body of his sister, Mrs. Waltz, and nailed to a tree in the yard. It struggled some time after the nails were driven through it! This occurred in the forenoon of Monday, 18th of August, 1862."[31]:300-301

Continued conflict

After the expulsion of the Dakota, some refugees and warriors made their way to Lakota lands. Battles continued between the forces of the Department of the Northwest and combined Lakota and Dakota forces through 1864. Col. Henry Sibley with 2,000 men pursued the Sioux into Dakota Territory. Sibley's army defeated the Lakota and Dakota in four major battles in 1863: the Battle of Big Mound on July 24, 1863; the Battle of Dead Buffalo Lake on July 26, 1863; the Battle of Stony Lake on July 28, 1863; and the Battle of Whitestone Hill on September 3, 1863. The Sioux retreated further, but faced a United States army again in 1864. General Alfred Sully led a force from near Fort Pierre, South Dakota, and decisively defeated the Sioux at the Battle of Killdeer Mountain on July 28, 1864.

Conflicts continued. Within two years settlers' encroachment on Lakota land sparked Red Cloud's War; the US desire for control of the Black Hills in South Dakota prompted the government to authorize an offensive in 1876 in what would be called the Black Hills War. By 1881, the majority of the Sioux had surrendered to American military forces. In 1890, the Wounded Knee Massacre ended all effective Sioux resistance.

Alexander Goodthunder and his wife Snana, a Dakota family that returned to Minnesota after the war

Minnesota after the war

The Minnesota River valley and surrounding upland prairie areas were abandoned by most settlers during the war. Many of the families who fled their farms and homes as refugees never returned. Following the American Civil War, however, the area was resettled. By the mid-1870s, it was again being used for agriculture.

The Lower Sioux Indian Reservation was reestablished at the site of the Lower Sioux Agency near Morton. It was not until the 1930s that the US created the smaller Upper Sioux Indian Reservation near Granite Falls.

Although some Dakota opposed the war, most were expelled from Minnesota, including those who attempted to assist settlers. The Yankton Sioux Chief Struck by the Ree deployed some of his warriors to this effect, but was not judged friendly enough to be allowed to remain in the state immediately after the war. By the 1880s, a number of Dakota had moved back to the Minnesota River valley, notably the Goodthunder, Wabasha, Bluestone and Lawrence families. They were joined by Dakota families who had been living under the protection of Bishop Henry Benjamin Whipple and the trader Alexander Faribault.

By the late 1920s, the conflict began to pass into the realm of oral tradition in Minnesota. Eyewitness accounts were communicated first-hand to individuals who survived into the 1970s and early 1980s. The stories of innocent individuals and families of struggling pioneer farmers being killed by Dakota have remained in the consciousness of the prairie communities of southcentral Minnesota.[32]

Monuments and memorials

The Camp Release State Monument commemorates the release of 269 captives at the end of the conflict and the four faces of the 51-foot granite monument are inscribed with information about the battles that took place along the Minnesota River during the conflict, the Dakota's surrender, and the creation of the monument.

Large stone monuments at the Wood Lake Battlefield and in the parade ground of Fort Ridgely commemorate the battles and members of the military killed in action.

Located at Center and State Streets, Defender's Monument was erected in 1891 by the State of Minnesota to honor the memory of the defenders who aided New Ulm during the Dakota War of 1862. The artwork at the base was created by New Ulm artist Anton Gag. Except for being moved to the middle of the block, the monument has not been changed since its completion.[33]

In 1972, the City of Mankato, Minnesota removed a plaque that had commemorated the mass execution of the thirty-eight Dakota from the site where the hanging occurred. In 1992, the City purchased the site and created Reconciliation Park.[34] There is purposely no mention of the execution, but several stone statues in and around the park serve as a memorial. The annual Mankato Pow-wow, held in September, commemorates the lives of the executed men, but also seeks to reconcile the European American and Dakota communities. The Birch Coulee Pow-wow, held on Labor Day weekend, honors the lives of those who were hanged.

A number of local monuments honor white civilians killed during the war. These include the: Acton, Minnesota monument to those killed in the attack on the Howard Baker farm; Guri Endreson monument in the Vikor Lutheran Cemetery near Willmar, Minnesota; and Brownton, Minnesota monument to the White family, and the Lake Shetek State Park monument to 15 white settlers killed there and at nearby Slaughter Slough on August 20, 1862.

In popular media

Attacks on settlers by Sioux warriors are portrayed in a 1972 film about immigrants from Sweden titled The New Land (Nybyggarna)

The This American Life episode 'Little War on the Prairie' discusses the continuing legacy of the conflict in Mankato, Minnesota.

See also

References

^ Kenneth Carley (15 July 2001). The Dakota War of 1862. Minnesota Historical Society Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-87351-392-0. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

^ Clodfelter, Micheal D. (2006). The Dakota War: The United States Army Versus the Sioux, 1862-1865. McFarland Publishing. p. 67. ISBN 0-7864-2726-4.

^ Dee Brown Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian American History of the American West, p. 40, Henry Holt, Owl Book edition (1991, copyright 1970), trade paperback, 488 pages, ISBN 0-8050-1730-5.

^ Kunnen-Jones, Marianne (2002-08-21). "Anniversary Volume Gives New Voice To Pioneer Accounts of Sioux Uprising". University of Cincinnati. Retrieved 2007-06-06.

^ Carly, Kenneth (1976). The Sioux Uprising of 1862 (Second edition ed.). Minnesota Historical Society.

^ Dillon, Richard H. (1920). North American Indian Wars. City: Booksales. p. 126.

^ Michno, Gregory. ""10 Myths on the Dakota Uprising"". (2012). True West Magazine.

^ Anderson, Gary. (1983) "Myrick's Insult: A fresh look at Myth and Reality", Minnesota History Quarterly 48(5):198-206.

^ Furst, Jay (22 December 2012). "Dakota War timeline". Rochester Post-Bulletin. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

^ Burnham, Frederick Russell (1926). Scouting on Two Continents. New York: Doubleday, Page and Co. p. 2 (autobiographical account). ASIN B000F1UKOA.

^ Soldiers: 3 killed/13 wounded; Lakota: 2 known dead.

^ "Ft. Rid". The Dakota Conflict of 1862: Battles. Mankato Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved 2007-04-06.

^ Minn Board of Commissioners (October 2005). Andrews, C. C., ed. Minnesota in the Civil and Indian Wars, 1861-1865: Two Volume Set with Index. Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-87351-519-1. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

^ "History – Minnesota Infantry (Part 1)". Union Regimental Histories. The Civil War Archive. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

^ Rogers, Leah D. (2009). "Fort Madison, 1808-1813". In William E. Whittaker. Frontier Forts of Iowa: Indians, Traders, and Soldiers, 1682–1862. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. pp. 193–206. ISBN 978-1-58729-831-8.

^ McKusick, Marshall B. (1975). The Iowa Northern Border Brigade. Iowa City, Iowa: Office of the State Archaeologist, The University of Iowa.

^ a b Schultz, Duane (1992). Over the Earth I Come: The Great Sioux Uprising of 1862. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-07051-9.

^ Appletons' annual cyclopaedia and register of important events of the year: 1862. New York: D. Appleton & Company. 1863. p. 588.

^ "History Matters". Minnesota Historical Society. March/April 2008. p. 1.

^ Abraham Lincoln (30 October 2008). The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. Wildside Press LLC. p. 493. ISBN 978-1-4344-7707-1.

^ Donald, David Herbert (1995). Lincoln. New York, New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 394–95.

^ Carley, Kenneth (1961). The Sioux Uprising of 1862. Minnesota Historical Society. p. 65. "Most of the thirty-nine were baptized, including Tatemima (or Round Wind), who was reprieved at the last minute."

^ "Human Remains from Mankato, MN in the Possession of the Public Museum of Grand Rapids, Grand Rapids, MI". National Park Service. 2000-04-08. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

^ Winks, Robin W. (1960). The Civil War Years: Canada and the United States, Baltimore : Johns Hopkins Press, 1960, p. 174.

^ a b Clapesattle, Helen (1969). The Doctors Mayo. Rochester, MN: Mayo Clinic; 2nd edition. ISBN 978-5-555-50282-7.

^ Records of the Mayo Clinic.

^ "The Two Sides of Camp McClellan". Davenport Public Library. Retrieved 2012-06-04.

^ Monjeau-Marz, Corinne L. (October 10, 2005). Dakota Indian Internment at Fort Snelling, 1862–1864. Prairie Smoke Press. ISBN 0-9772718-1-1.

^ "Where the Water Reflects the Past". The Saint Paul Foundation. 2005-10-31. Retrieved 2006-12-12.

^ "family History". Census of Dakota Indians Interned at Fort Snelling After the Dakota War in 1862. Minnesota Historical Society. 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-12.

^ a b Bryant, Charles S.; Abel B. Murch (1864). A history of the great massacre by the Sioux Indians in Minnesota : including the personal narratives of many who escaped. Chicago: O.C. Gibbs. ISBN 978-1-147-00747-3.

^ Producers: Mark Steil and Tim Post (2002-09-26). "Minnesota's Uncivil War". MPR. KNOW-FM.

^ "Defender's Monument". Brown County Historical Society. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

^ Barry, Paul. "Reconciliation – Healing and Remembering". Retrieved 6 September 2011.

Further reading

Anderson, Gary and Alan Woolworth, editors. Through Dakota Eyes: Narrative Accounts of the Minnesota Indian War of 1862, Minnesota Historical Society Press (1988). ISBN 0-87351-216-2

Beck, Paul N., Soldier Settler and Sioux: Fort Ridgely and the Minnesota River Valley 1853–1867, Pine Hill Press, Inc. (2000). ISBN 0-931170-75-3

Berg, Scott W., 38 Nooses: Lincoln, Little Crow, and the Beginning of the Frontier's End Pantheon (2012). ISBN 0-307377-24-5

Collins, Loren Warren. The Story of a Minnesotan, (private printing) (1912, 1913?). OCLC 7880929

Cox, Hank. Lincoln And The Sioux Uprising of 1862, Cumberland House Publishing (2005). ISBN 1-58182-457-2

Folwell, William W.; Fridley, Russell W. A History of Minnesota, Vol. 2, pp. 102–302, Minnesota Historical Society (1961). ISBN 978-0-87351-001-1

Jackson, Helen Hunt. "A Century of Dishonor: A Sketch of the United States Government's Dealings with some of the Indian Tribes (1887), Chapter V.: The Sioux, pp. 136–185. [1]

Johnson, Roy P. The Siege at Fort Abercrombie, State Historical Society of North Dakota (1957). OCLC 1971587

Linder, Douglas The Dakota Conflict Trials of 1862 (1999).

Nix, Jacob. The Sioux Uprising in Minnesota, 1862: Jacob Nix's Eyewitness History, Max Kade German-American Center (1994). ISBN 1-880788-02-0

Tolzmann, Don Heinrich, German Pioneer Accounts of the Great Sioux Uprising of 1862, Little Miami Pub. Co. (April 2002). ISBN 978-0-9713657-6-6.

Yenne, Bill. Indian Wars: The Campaign for the American West, Westholme (2005). ISBN 1-59416-016-3

External links

Source: https://encyclopedia.thefreedictionary.com/Dakota+War+of+1862

1 note

·

View note

Text

Best known for: chief of the Mdewákantoηwaη Dakota people. He is notable for his role in the negotiation of the Treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota of 1851, in which he agreed to the movement of his band of the Dakota to a reservation near the Minnesota River in exchange for goods and certain other rights. However, the government reneged on its promises to provide food and annuities to the tribe, and Little Crow was forced to support the decision of a Dakota war council in 1862 to pursue war to drive out the whites from Minnesota. Little Crow participated in the Dakota War of 1862 but retreated in September 1862 before the war's conclusion in December 1862.

0 notes