#Tréguier

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Graffiti in a toilet, Tréguier

#Graffiti in a toilet#Tréguier#visualzen#abstract#minimalism#photography#streetart#graffitti#art#france#bretagne#kultur#mabellebretagne#original photographers#photographers on tumblr#black and white

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Calvary in Tréguier, Brittany region of France

French vintage postcard

#postal#france#historic#french#ansichtskarte#brittany#calvary#sepia#vintage#tarjeta#briefkaart#photo#trguier#postkaart#ephemera#postcard#postkarte#photography#region#tréguier#carte postale

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

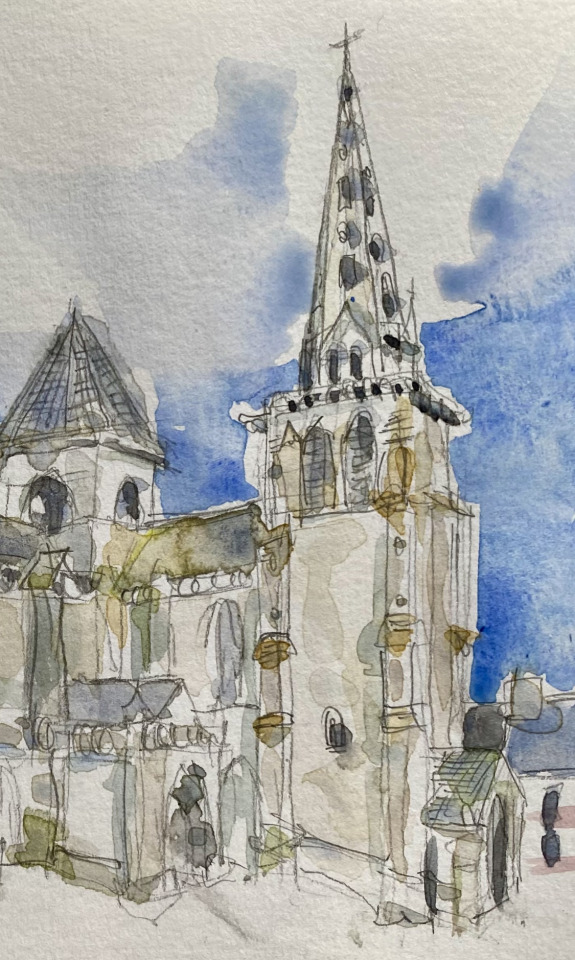

Cathédrale de Tréguier | juillet 2023

#aquarelle#watercolor#Tréguier#cotesdarmor#bretagne#drawingdaily#sketchbook#artwork#artists on tumblr

17 notes

·

View notes

Video

Tréguier (Côtes-d'Armor) - Cathédrale Saint-Tugdual - Transept sud - Grande verrière (vitrail de Hubert de Sainte-Marie de Quintin) by Patrick Via Flickr: Tréguier (Côtes-d'Armor) - Cathédrale Saint-Tugdual - Transept sud - Grande verrière (vitrail de Hubert de Sainte-Marie de Quintin) La vigne mystique se mêle aux fondateurs des septs évêchés bretons, aux saints du terroir et aux métiers bretons fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hubert_de_Sainte-Marie fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cath%C3%A9drale_Saint-Tugdual_de_Tr...

0 notes

Text

Arthurian myth: Morgan the Fey (1)

Loosely translated from the French article "Morgane", written by Philippe Walter, for the Dictionary of Feminine Myths (Le Dictionnaire des Mythes Féminins)

MORGANE

Morgane means in Celtic language “born from the sea” (mori-genos). This character is as such, by her origins, part of the numerous sea-creatures of mythologies. A Britton word of the 9th century, “mormorain”, means “maiden of the sea/ sea-virgin”, et in old texts it is equated with the Latin “siren”. A passage of the life of saint Tugdual of Tréguiers (written in 1060) tells of ow a young man of great beauty named Guengal was taken away under the sea by “women of the sea”. The Celtic beliefs knew many various water-fairies with often deadly embraces – and Morgane was one among the many sirens, mermaids, mary morgand and “morverc’h” (sea girls/daughters of the sea).

Morgane, the fairy of Arthurian tales, is the descendant of the mythical figures of the Mother-Goddesses who, for the Celts, embodied on one side sovereignty, royalty and war, and on the other fecundity and maternity. In the Middle-Ages, they were renamed “fairies” – but through this word it tried to translate a permanent power of metamorphosis and an unbreakable link to the Otherworld, as well as a dreaded ability to influence human fate. The French word “fée” comes from the neutral plural “fata”, itself from the Latin word “fatum”, meaning “fate”.

There is not a figure more ambivalent in Celtic mythology – and especially in the Arthurian legends – than Morgane. She constantly hesitates between the character of a good fairy who offers helpful gifts to those she protects ; and a terrible, bloodthirsty goddess out for revenge, only sowing death and destruction everywhere she goes. Christianity played a key role in the demonization of this figure embodying an inescapable fate, thus contradicting the Christian view of mankind’s free will.

I/ The sovereign goddess of war

It is in the ancient mythological Irish texts that the goddess later known as Morgane appears. The adventures of the warrior Cuchulainn (the “Irish Achilles”) with the war-goddess Morrigan are a major theme of the epic cycle of Ireland. The Morrigan (a name which probably means “great queen”) is also called “Bodb Catha” (the rook of battles). It is under the shape of a rook (among many other metamorphosis) that she appears to Cuchulainn to pronounce the magical words that will cause the hero’s death.

The Irish goddesses of war were in reality three sisters: Bodb, Macha and Morrigan, but it is very likely that these three names all designated the same divinity, a triple goddess rather than three distinct characters. This maleficent goddess was known to cause an epileptic fury among the warriors she wanted to cause the death of. The name of Bodb, which ended up meaning “rook”, originally had the sense of “fury” and “violence”, and it designated a goddess represented by a rook. The Irish texts explain that her sisters, Macha and Morrigan, were also known to cause the doom of entire armies by taking the shape of birds. Every great battle and every great massacre were preceded by their sinister cries, which usually announced the death of a prominent figure.

The Celtic goddesses of war have as such a function similar to the one of the Norse Walkyries, who flew over the battlefield in the shape of swans, or the Greek Keres. The deadly nature of these goddesses resides in the fact that they doom some warriors to madness with their terrifying screams. One of the effects of this goddess-caused madness was a “mad lunacy”, the “geltacht”, which affected as much the body as the mind. During a battle in 1722 it was said that the goddess appeared above king Ferhal in the shape of a sharp-beaked, red-mouth bird, and as she croaked nine men fell prey to madness. The poem of “Cath Finntragha” also tells of the defeat of a king suffering from this illness. The place of his curse later became a place of pilgrimage for all the lunatics in hope of healing.

The link between the war-goddess and the “lunacy-madness” are found back within folklore, in which fairies, in the shape of birds, regularly attack children and inflict them nervous illnesses. These fairies could also appear as “sickness-demons”. Their appearance was sometimes tied to key dates within the Celtic calendar, such as Halloween, which corresponded to the Irish and pre-Christian celebration of Samain. Folktales also keep this particularly by placing the ritualistic appearances of witches and of fate-fairies during the Twelve Days, between Christmas and the Epiphany – another period similar to the Celtic Halloween. Morgane seems to belong to this category of “seasonal visitors”.

II) The Queen of Avalon

In Arthurian literature, Morgane rules over the island of Avalon, a name which means the Island of Apples (the apple is called “aval” in Briton, “afal” in Welsh and “Apfel” in German). Just like the golden apples of the Garden of the Hesperids, in Celtic beliefs this fruit symbolizes immortality and belongs to the Otherworld, a land of eternal youth. It is also associated with revelations, magic and science – all the attributes that Morgane has. Her kingdom of Avalon is one of the possible localizations of the Celtic paradise – it is the place that the Irish called “sid”, the “sedos” (seat) of the gods, their dwelling, but at the same time a place of peace beyond the sea. Avalon is also called the Fortunate Isle (L’Île Fortunée) because of the miraculous prosperity of its soil where everything grows at an abnormal rate. As such, agriculture does not exist there since nature produces by itself everything, without the intervention of mankind.

It is within this island that the fairy leads those she protects, especially her half-brother Arthur after the twilight of the Arthurian world. Morgane acts as such as the mediator between the world of the living and the fabulous Celtic Otherworld. Like all the fairies, she never stops going back and forth between the two worlds. Morgane is the ideal ferrywoman. The same way the Morrigan fed on corpses or the Valkyries favored warriors dead in battle, Morgane also welcomes the soul of the dead that she keeps by her side for all of eternity. Some texts gave her a home called “Montgibel”, which is confused with the Italian Etna. The Otherworld over which she rules doesn’t seem, as such, to be fully maritime.

The ”Life of Merlin” of the Welsh clerk Geoffroy of Monmouth teaches us that Morgan has eight sisters: Moronoe, Mazoe, Gliten, Glitonea, Gliton, Thiten, Tytonoe, and Thiton. Nine sisters in total which can be divided in three groups of three, connected by one shared first letter (M, G, T). In Adam de la Halle’s “Jeu de la feuillée”, she appears with two female companions (Arsile and Maglore), forming a female trinity. As such, she rebuilds the primitive triad of the sovereign-goddesses, these mother-goddesses that the inscriptions of Antiquity called the “Matres” or “Matronae”. In this triad, Morgane is the most prominent member. She is the effective ruler of Avalon, since it was said that she taught the art of divination to her sisters, an art she herself learned from Merlin of which she was the pupil. She knows the secret of medicinal herbs, and the art of healing, she knows how to shape-shift and how to fly in the air. Her healing abilities give her in some Arthurian works a benevolent function, for example within the various romans of Chrétien de Troyes. She usually appears right on time to heal a wounded knight: she is the one that gave a balm to Yvain, the Knight of the Lion, to heal his madness. In these works, Morgane does not embody a force of destruction, but on the contrary she protects the happy endings and good fortunes of the Round Table. She is the providential fée that saves the souls born in high society and raised in the “courtois” worship of the lady. However, her powers of healing can reverse into a nefarious power when the fée has her ego wounded.

III/ The fatal temptress

In the prose Arthurian romans of the 13th century, Morgane can be summarized by one place. After being neglected by her lover Guyomar, she creates “le Val sans retour”, the Vale of No-Return, a place which will define her as a “femme fatale”. This place transports without the “littérature courtoise” the idea of the Celtic Otherworld. Also called “Le Val des faux amants” (The Vale of False Lovers), “le Val sans retour” is a cursed place where the fée traps all those that were unfaithful to her, by using various illusions and spells. As such, she manifests both her insatiable cruelty and her extreme jealousy. Lancelot will become the prime victim of Morgane because, due to his love for Queen Guinevere, he will refuse her seduction. The feelings of Morgane towards Lancelot rely on the ambivalence of love and hate: since she cannot obtain the love of the knight by natural means, she will use all of her enchantments and magical brews to submit Lancelot’s will. In vain. Lancelot will escape from the influence of this wicked witch. In “La Mort le roi Artu”, still for revenge, Morgan will participate in her own way to the decline to the Arthurian world: she will reveal to her brother, king Arthur, the adulterous love of Guinevre and Lancelot. She will bring to him the irrefutable proof of this affair by showing her what Lancelot painted when he had been imprisoned by her. The terrible war that marks the end of the Arthurian world will be concluded by the battle between Arthur and Mordred, the incestuous son of Arthur and Morgan. As such, Morgan appears as the instigator of the disaster that will ruin the Arthurian world. She manipulates the various actors of the tragedy and pushes them towards a deadly end. It should be noted that any sexual or romantic relationship between Arthur and Morgane are absent from the French romans – they are especially present within the British compilation of Malory, La Mort d’Arthur.

Behind the possessive woman described by the Arthurian texts, hides a more complex figure, a leftover of the ancient Celtic goddess of destinies. Cruel and manipulative, Morgan is fuses with the fear-inducing figure of the witch. Despite being an enemy of men, she keeps seeking their love. All of her personal tragedy comes from the fact that she fails to be loved. Always heart-sick, she takes revenge for her romantic failure with an incredible savagery. Her brutality manifest itself through the ugliness that some text will end up giving her – the ultimate rejection by this Christian world of this “devilish and lustful temptress”. “La Suite du Roman de Merlin” will try to give its own explanation for this transformation of Morgane, from good to wicked fairy: “She was a beautiful maiden until the time she learned charms and enchantments ; but because the devil took part in these charms and because she was tormented by both lust and the devil, she completely lost her beauty and became so ugly that no one accepted to ever call her beautiful, unless they had been bewitched”. In this new roman, she is responsible for a series of murders and suicides – and as the rival of Guinevere, she tries to cause King Arthur’s doom by favorizing her own lover, Accalon. Another fée, Viviane, will oppose herself to her schemes.

The demonization of the goddess is however not complete. Morgan appears in several “chansons de gestes” of the beginning of the 13th century, and even within the Orlando Furioso of the Arisote, in the sixth canto, in which she is the sister of the sorceress Alcina. She is presented as the disciple of Merlin. Seer and wizardess, she owns (within Avalon or the land of Faerie) a land of pleasure, a little paradise in which mankind can escape its condition. At the same time the Arthurian texts discredit her, she joins a strange historico-pagan syncretism, by being presented as the wife of Julius Caesar, and as the mother of Aubéron, the little king of Féerie.

After the Middle-Ages, the fée Morgane only mostly appears within the Breton folklore (the French-Britton folklore, of the French region of Bretagne). There, old mythical themes which inspired medieval literature are maintained alive, and keep existing well after the Middles-Ages. Morgane is given several lairs, on earth or under the sea. In the Côtes-d’Armor, there is a Terte de la fée Morgan, while a hill near Ploujean is called “Tertre Morgan”. There is an entire branch of popular literature in Bretagne (such as Charles Le Bras’ 1850 “Morgân”) where the fée represents the last survivor of a legendary land and the reminder of a forgotten past. She expresses the nostalgia of a lost dream, of a fallen Golden Age. True Romantic allegory of the lands and seas of Bretagne, she most notably embodies the feeling of a Bretagne land that was in search of its own soul.

However, it is her role of “cursed lover” that stays the most dominant within the Breton folklore. The vicomte de La Villemarqué, great collector of folktales and popular legends, noted in his “Barzaz Breiz” (1839) that the “morgan”, a type of water spirits, took at the bottom of the sea or of ponds, in palaces of gold and crystal, young people that played too close to their “haunted waters”. The goal of these fairies was to kidnap them to regenerate their cursed species. This ties the link between these “morganes” (also called “mary morgand”) and the Antique “fairy of fate”. Similar names, a same love of water, and the presence of the “land below the waves”, of a malevolent seduction – these are the permanent traits of Morgane, who keeps confusing and uniting the romantic instinct for love, and the desire for death. More modern adaptations of the legend (such as Marion Zimmer Bradley’s novels) weave an entire feminist fantasy around the figure of this fairy, supposed to embody the Celtic matriarchy.

#arthuriana#arthurian myth#arthurian legend#morgane#morgan#morgan le fey#fée#french folklore#folklore of bretagne#celtic mythology#irish mythology

50 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Officially, Constance is Conan and Margaret’s only child, but a certain William, brother of the Duchess is cited as a witness in acts C45 and A16. He is either an illegitimate son of Conan or a second child of the ducal couple because the first name William translates easily into English, which would suit Margaret perfectly by recalling her English royal parentage. In any case, William was removed from the succession by the marriage of his sister, who received the duchy as a dowry because it is clear that the presence of a son could only thwart Henry's intentions. An only child allows him to conquer the duchy by marrying her to his son Geoffrey without waiting for Conan's death, which the presence of a male heir barred him from doing. William is therefore set aside to maintain an official version allowing Conan to abdicate and Henry II to obtain custody of Constance and therefore of the duchy. Perhaps Conan kept the Count of Tréguier for this disinherited son. Nevertheless, William, trained as a cleric, remained in his sister’s entourage and contented himself with intervening in the administrative life of the duchy.

Constance's mother, Margaret, is mentioned on only one occasion in her daughter's deeds (C36) to have her confirm one of her gifts, an act which is also attested by Henry de Bohun, Margaret's son from her second marriage and therefore Constance's half-brother. Although they had a very close relationship, Margaret did not stay at her daughter's court. Her possessions in England and her remarriage kept her away from Brittany.

Finally, certain acts of Constance are attested by Etienne (Stephen) qualified as the duchess's uncle. Acts C3, C5 and C19 drawn up in Quimperlé and Nantes prove that at one time Etienne lived at court and followed it in its travels. Unfortunately, we don't have any information on the figure to establish his relationship to either Conan IV or Margaret.

Mari-Anna Sohier, Étude des actes de la duchesse Constance et de sa famille

#historyedit#twelfth century#william clericus#margaret of huntingdon#etienne of brittany#constance of brittany#my edit#my best guess is etienne is probably one of alan le noir's sons#he had several bastard children and a significant age difference with bertha#and etienne would be an established name in that part of the family if his grandfather was etienne de penthièvre#so my gif choice was primarily based on that

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

MAY_2424_00002 by Roy Curtis Photography France - Brittany. Tréguier. St. Yves Cathedral. Stained glass.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 11.5 (before 1940)

1138 – Lý Anh Tông is enthroned as emperor of Vietnam at the age of two, beginning a 37-year reign. 1499 – The Catholicon, written in 1464 by Jehan Lagadeuc in Tréguier, is published; this is the first Breton dictionary as well as the first French dictionary. 1556 – Second Battle of Panipat: Fighting begins between the forces of Hem Chandra Vikramaditya, the Hindu king at Delhi and the forces of the Muslim emperor Akbar. 1605 – Gunpowder Plot: Guy Fawkes is arrested in the cellars of the Houses of Parliament, where he had planted gunpowder in an attempt to blow up the building and kill King James I of England. 1688 – Prince William III of Orange lands with a Dutch fleet at Brixham to challenge the rule of King James II of England (James VII of Scotland). 1757 – Seven Years' War: Frederick the Great defeats the allied armies of France and the Holy Roman Empire at the Battle of Rossbach. 1768 – The Treaty of Fort Stanwix is signed, the purpose of which is to adjust the boundary line between Indian lands and white settlements set forth in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 in the Thirteen Colonies. 1780 – French-American forces under Colonel LaBalme are defeated by Miami Chief Little Turtle. 1811 – Salvadoran priest José Matías Delgado rings the bells of La Merced church in San Salvador, calling for insurrection and launching the 1811 Independence Movement. 1828 – Greek War of Independence: The French Morea expedition to recapture Morea (now the Peloponnese) ends when the last Ottoman forces depart the peninsula. 1834 – Founding of the Free University of Brussels by Pierre-Théodore Verhaegen. 1862 – American Civil War: Abraham Lincoln removes George B. McClellan as commander of the Army of the Potomac. 1862 – American Indian Wars: In Minnesota, 303 Dakota warriors are found guilty of rape and murder of whites and are sentenced to death. Thirty-eight are ultimately hanged and the others reprieved. 1872 – Women's suffrage in the United States: In defiance of the law, suffragist Susan B. Anthony votes for the first time, and is later fined $100. 1881 – In New Zealand, 1600 armed volunteers and constabulary field forces led by Minister of Native Affairs John Bryce march on the pacifist Māori settlement at Parihaka, evicting upwards of 2000 residents, and destroying the settlement in the context of the New Zealand land confiscations. 1895 – George B. Selden is granted the first U.S. patent for an automobile. 1898 – Negrese nationalists revolt against Spanish rule and establish the short-lived Republic of Negros. 1911 – After declaring war on the Ottoman Empire on September 29, 1911, Italy annexes Tripoli and Cyrenaica. 1912 – Woodrow Wilson is elected the 28th President of the United States, defeating incumbent William Howard Taft. 1913 – King Otto of Bavaria is deposed by his cousin, Prince Regent Ludwig, who assumes the title Ludwig III. 1914 – World War I: France and the British Empire declare war on the Ottoman Empire. 1916 – The Kingdom of Poland is proclaimed by the Act of 5th November of the emperors of Germany and Austria-Hungary. 1916 – The Everett massacre takes place in Everett, Washington as political differences lead to a shoot-out between the Industrial Workers of the World organizers and local police. 1917 – Lenin calls for the October Revolution. 1917 – Tikhon is elected the Patriarch of Moscow and of the Russian Orthodox Church. 1925 – Secret agent Sidney Reilly, the first "super-spy" of the 20th century, is executed by the OGPU, the secret police of the Soviet Union.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hommage à Pierre Taupin, héros de la chouannerie du Trégor

Christian Gilbert Aujourd’hui, c’est le triste anniversaire de la mort, le 10 février 1800, de Pierre Taupin, un des chefs de la troisième chouannerie dans les Côtes-du-Nord, ayant principalement combattu dans l’est du pays de Tréguier. Il naît le 31 mars 1753 à Omméel, dans l’Orne, en Normandie. En 1792, il est valet de chambre de l’évêque de Tréguier, Monseigneur Augustin-René-Louis Le Mintier.…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cathédrale Saint-Tugdual de Tréguier

#visualzen#bretagne#photography#minimalistgrammer#flower#church#art#original photographers#photographers on tumblr

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

#black and white photography#monochrome#industrial landscape#Port de Commerce Tréguier#Tréguier#Bretaña#Javi Roa

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Market scene in Tréguier, Brittany region of France

French vintage postcard

#sepia#photography#trguier#vintage#france#postkaart#tréguier#ansichtskarte#ephemera#carte postale#postcard#postal#briefkaart#region#market#photo#brittany#scene#tarjeta#historic#french#postkarte

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Projet 52-2023 semaine 12 : courant

Pas mal d’interprétations pour ce thème, pas toujours faciles à illustrer. Cette semaine, il y avait des grandes marées sur la côté, avec des vagues gigantesques à Saint-Malo et à Roscoff… même un peu plus loin dans les terres, les cours d’eau ont subi les conséquences de la montée du niveau d’eau aggravée par de fortes précipitations. De ce fait, à Tréguier, les bancs et les tables de…

View On WordPress

#Bretagne#chevaux#courant#courses#Du côté de chez Ma#eau#inondations#lifestyle#loisirs#normandie#photographie#plage#Projet 52#rivière#saison

1 note

·

View note

Text

While this is very touching, I am wondering somewhat how people get the idea that Europeans are less likely to have their bodies displayed. Medical history museums exist, and they're not just chock-full of (European) skeletons, but also of a vast number of specimens stored in alcohol, plastinated remains, wax models etc.

The point here is that poor people were more likely to end up in these collections because 1. they were more likely to suffer from 'medically interesting' health conditions and 2. more likely to not be able to afford a proper burial (and keeping their loved ones out of the hands of anatomists etc).

The Federal Pathologic-Anatomical Museum in Vienna, Austria with wax models on display.

However, the market of display bones is actually covered primarily by churches, particularly catholic and eastern orthodox ossuaries. And far too many skeletons and body parts are used as relics. You can't enter any decently sized catholic church without basically falling over a few bones.

We can accuse the Europeans of many things, but that they were somehow reluctant to put their own mortal bodies on display is certainly not one of them.

Reliquiary of St. Yves in Tréguier, France.

Catacombs in Paris.

Sedlec Ossuary in the Czech Republic.

San Bernardino alle Osse in Milan, Italy.

I was rambling on the issue of museums and human remains and how certain populations are more likely to have their bodies put on display to be gawked at and then went "well I guess the Pompeii casts were of Europeans. there are bones in there right?" and Googled it to make sure, at which point I confirmed that yes there are bones in there, but more interestingly DNA testing revealed that a cast of an adult holding a child everyone assumed was a mother and child were, in fact, a man and a kid entirely unrelated to him. Honestly that's more moving to me. Maybe they were connected in a way other than blood, but maybe a stranger saw a child when the world was ending and thought the one thing he could do was hold them.

47K notes

·

View notes

Text

En avance sur son temps ?

BLOG KELOU. Ven 22.05.2015, 19:23. MISE À JOUR. http://jfsaby.com/blogs/index.php/kelou/vW6 Article modifié. 1 PHOTO. En visitant la salle du « Trésor » de la cathédrale Saint Tugdual de Tréguier, je suis resté pantois devant la statue de Saint Jean l'Evangéliste. Je n'avais jamais entendu dire qu'il était le saint patron des auto-stoppeurs…

0 notes