#Top Cross Breed Cow Supplier

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Research On Wagyu-style Beef Alternatives Begin At Ubc

Our pals at Cowbell Kitchen have lately added these 2 new nice menu objects. Either one is an awesome opportunity to pattern Grazing Meadows Wagyu. To view Cowbell Kitchen's full menu click on this hyperlink COWBELL KITCHEN MENU. As a chef I even have been fortunate to work with the Prior's and their unbelievable Wagyus. The meat has a tremendous sweetness that I even have by no means encountered before.

To put it merely, whereas all Kobe beef is Wagyu, but not all Wagyu is Kobe beef. Not surprisingly most individuals are, hopefully we will provide the data you should be informed the following time you are trying to purchase Kobe/Wagyu beef. Wagyu beef actually does take purple meat to a stage past Prime. Wagyu is arguably the most effective and most expensive beef cash can purchase. With its distinctive marbling, superior tenderness and beautiful flavor, it’s no marvel Wagyu is the top of the meat world. For close to a decade our desire at Grazing Meadows Wagyu has been the advancement, promotion and consciousness of the Wagyu breed of cattle.

The solutions to these questions and extra are just a scroll away. Enjoy FREE supply on $200+ orders, and FREE pickup on $95+ orders. Black Opal is certainly one of Australia’s best Wagyus, delivering a easy texture and superior marbling every time. Your net browser doesn't assist storing data locally.

Please present us together with your info and we will notify you as soon as we now have products out there in your province. That's what I did, principally waited for a special occasion nevertheless it's not like it happens on a daily basis so it's good to treat your self every so often. FREE DELIVERY from $100 inside Greater Montreal or from $150, depending on your postal code. It’s paying homage to the “uncanny valley,” an issue that has lengthy bedevilled robotics and digital artwork. Attempts to create a duplicate of the human face turn into more disturbing and unsettling as one will get nearer to perfection—almost human is creepier than clearly not human.

The USDA and CFIA approvals allow WÄGYU branded merchandise to be shipped to retailers and foodservice suppliers in any U.S. state or Canadian province. The Miyazaki Wagyu brand name can only be applied to black-haired Wagyu born and raised in Miyazaki Prefecture. Miyazaki Prefecture is positioned in southern-eastern Kyushu Island, and space blessed with a temperate local weather throughout the year. Clean water and farmland offers the perfect surroundings to lift Wagyu cattle.

Alberta beef producers like Bite Beef or Top Grass go for a continued grass finish to their cattle’s diet leading to leaner cuts of meat and a notable flavour distinction. The decrease fats content material in grass-finished beef is what individuals seem to be loving about these native products. Known for its extreme marbling, resulting in almost melt-in-your-mouth tenderness, wagyu beef has been adored by Canadian cooks wagyu beef canada because the Japanese heritage breed of cow made it’s means abroad in the early 1990s. Snake River Farms keep purebred Wagyu cow and bull herds from renowned Japanese bloodlines. These imported cattle are the muse of our Snake River Farms program.

If the meat is descendent of Japanese cattle, raised outside Japan, or crossbred exterior Japan, and not sourced immediately from Japan, it’s not wagyu. In reality, most Japanese cattle in Japan are cross-bred, but wagyu beef canada the difference between beef in Japan, and Japanese beef or some spinoff of it in, say, Canada, is evening and day. From water, to climate, to feed, to care, it’s just completely different.

This means the cattle raised there graze fortunately and free, resulting in a extra flavourful, leaner, and nutritious beef with less saturated fat and healthier Omega-3 fatty acids. You definitely will not miss the extra fats with the pure flavour of this beef. They have long horns and lengthy wavy coats which are colored black, brindle, pink wagyu beef canada, yellow, white, silver, or dun. Originated within the Highland and Western Isles of Scotland, they have been first talked about in the sixth century AD. They are a hardy breed due to their native surroundings. This ends in long hair, giving the breed its capacity to overwinter.

0 notes

Photo

Cross Breed Cow Supplier In Karnal | Pandit Dairy Farm

Pandit Dairy Farm is one of the best cross breed cow supplier in karnal. We are the suppliers of HF cow, Sahiwal cow, Murrah Bull and Murrah Buffalo. Before we feed our pure breed cattle, they are medically evaluated by famous veterinarians, who also develop diets for them. Each cattle is given personalised attention since we believe in and practise ethical animal treatment.

#Cross Breed Cow Supplier In Karnal#Best Cross Breed Cow Supplier In Karnal#Top Cross Breed Cow Supplier In Karnal#Cross Breed Cow Supplier#Best Cross Breed Cow Supplier#Top Cross Breed Cow Supplier

1 note

·

View note

Text

Americans Used to Eat Pigeon All the Time—and It Could Be Making a Comeback

It’s reviled by city slickers, but revered by chefs.

— By Eleanor Cummins | February 16, 2018 | Popular Science

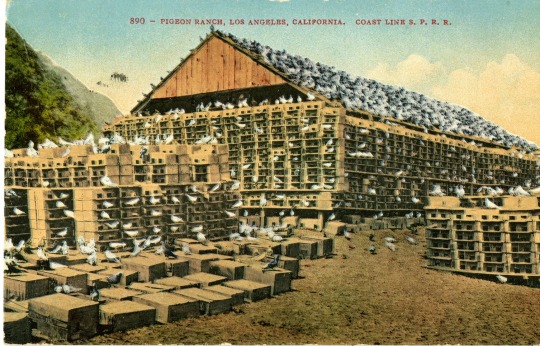

A vintage postcard of a pigeon plant. Wikimedia Commons

Brobson Lutz remembers his first squab with perfect clarity. It was the 1970s at the now-closed French restaurant Lutèce in New York City. “I came from North Alabama where there was a lot of dove and quail hunting and I knew how tasty little birds were,” the fast-talking Southerner recalls. “I’m not even sure if I knew then if it was a baby pigeon or not. But I became enamored with them.”

When he returned home, however, the New Orleans-based physician found pigeon meat in short supply. The bird was occasionally served in the Big Easy, but to satiate his need for squab, Lutz had to get creative. For a time, he says, he would call Palmetto Pigeon Plant, the country’s largest squab producer, and try to buy in bulk. “I pretended like I was a restaurant chef on the telephone to buy some from them, because they were only wholesale,” he says.

Eventually, Lutz decided to take matters into his own hands—and onto his own property. He bought some land along the Mississippi River, retrofitted a building into a pigeon loft, and bought a few pairs of breeding birds. “My initial plan was to go commercial, and I had a restaurant that wanted ‘em,” he says. But he’s found out he’s gotten a quarter of the production he expected. “I don’t know if it’s too hot here in the summer or if they’re not happy here or something, I’m lucky if I get from one pair six babies a year.” It’s enough to fill Lutz, but not enough to share his passion for pigeon meat with his fellow Louisianans.

Squab, once among the most common sources of protein in the United States, has fallen out of favor in the last century. The speedy, handsome, tender, and tasty pigeon of yesteryear was replaced in the hearts and minds of post-World War II Americans with the firsthand experience of the city pigeon, whose excrement encrusts our cities. It was replaced on the plate, too, by the factory-farmed chicken. But thanks to foodies like Lutz, squab is making a slow and steady comeback in French and Chinese restaurants around the country. Trouble is, the bird’s unique development needs mean farmers struggle to meet the growing demand.

A kit of passenger pigeons called for a shoot-out. Wikimedia Commons

Allen Easterly of Rendezvous Farm in Virginia sells his squabs in the Washington, D.C. area. He says most people are ignorant of the pigeon's culinary value—and that many seem to wish they could stay in the dark. "At the farmer's market, people say, 'What are squab?' And you say, 'Young pigeons.' And they go, 'Ew,'" he says. "They're thinking of the city birds pooping all over statues."

Pigeons may be reviled in the United States today, but as any squab enthusiast will tell you, for most of human history, the 310-ish species in the pigeon-dove family were revered. The little birds were a common theme for Pablo Picasso, who named his daughter Paloma, the Spanish word for dove. And physicist and futurist Nikola Tesla sought solace in his avian neighbors. One night in 1922, his favorite pigeon flew into his window looking distressed and eventually died. He reportedly said, "I loved that pigeon as a man loves a woman, and she loved me."

Since at least ancient Egypt, domesticated pigeons have served as a messengers. Their enviable speed and pristine sense of direction made them an important communication strategy well into the 20th century. Even when telegrams and eventually phone lines criss-crossed the continent, pigeons were often more reliable. During World War I, homing pigeons were used to discreetly deliver messages across enemy lines. One bird, Cher Ami, famously delivered a life-saving note to Army headquarters, despite being shot through the breast and blinded on her flight across the battlefield. She was awarded a French military honor, the Croix de Guerre, and her one-legged body (Cher Ami's right limb was also lost in her fated journey) sits taxidermied in the Smithsonian Museum of American History.

The pigeon's descent into the proverbial gutter is hard to chart, but its fate appears to have been sealed by 1914. That year, the last of the wild passenger pigeons, a little bird named Martha, died in captivity at the Cincinnati Zoo. The birds were once so plentiful in North America that a kit (that's the collective noun for a group of pigeons) in the midst of migration could black out the sun. As they traipsed across the Midwest and Eastern United States, snacking in farmer's fields along the way, hungry humans would pull the babies from the nest and cook them for a quick meal. But deforestation and overhunting—people not only stole the babies, but shot the adults from the sky—drove them to extinction in just a few centuries.

For those who remembered the passenger pigeon's prime, squab remained a popular dish. The birds merely morphed from a kitchen staple to a rare treat sourced from local farms or shipped in from faraway poultry plants. But these days, pigeon is a dish best served defensively. For the generations after World War II, who have grown up on factory-farmed chicken at the expense of other birds, the pigeon is a nuisance, not a source of nutrition. In the 1960s, prices for pigeon meat dropped as demand for pest control skyrocketed. In 1980, Woody Allen dubbed the same New York City pigeons Tesla adored "rats with wings" in his film Stardust Memories.

While it's true that city pigeons shouldn't be eaten, rumors that they are a particularly diseased bird are just that—rumors. Pigeons are no more likely to carry avian disease than any other bird, but we have made these feral birds moderately dangerous by feeding them our trash. Unlike farm breeds, which are carefully controlled and fed a special diet, city pigeons clean up our forgotten pizza crusts... and likely ingest rodenticide, battery acid, and lead along the way.

Around the same time that enterprising businessmen began putting up spikes and spreading poisons in pigeon-dense parks, the chicken, previously a fragile and finicky bird prized primarily for its eggs, became the nation's leading source of poultry. In 1916, just two years after Martha the passenger pigeon died in captivity, scientists began work to develop a "broiler" chicken, bred specifically for meat production. The hope was the bird would grow big and grow fast. After years of tinkering, the Cobb company launched its breeding program in the 1940s and other poultry producers soon followed. By 1960, the National Chicken Council reports, the per capita consumption of chicken was around 28 pounds. In 2018, the council projects we'll each consume about 92.5 pounds of the bird.

Despite the public vitriol and stiff competition from chicken, a few folks, motivated by the pigeon's gastronomic promise, have preserved the squab-eating tradition. Scott Schroeder is the owner and chef of Hungry Pigeon, a restaurant in Philadelphia. Trained in French cooking, he started eating squab early in his career, and has only become more enamored of its taste. "I really fell deeply in love with them in a way," he says of squab carcasses. "The breast in particular tastes like a mixture of duck and steak at the same time, which to me sounds really good."

There are two reasons for this unique flavor. First, pigeons are an entirely dark meat bird, meaning they have a high concentration of myoglobin, the oxygen-storing protein that gives dark meat its unique color and taste. Where myoglobin is concentrated in a chicken’s legs, it courses through a pigeon’s entire body, allowing for a more succulent, if iron-intense, eating experience. The second factor is the age at which a pigeon is killed. Like veal, the prized meat of young cows, farmers kill squab when they’re young and their meat is tender. By trapping them just days before they take their first flight—typically around four weeks old—farmers ensure that the meat around a baby pigeon’s wings are never used and therefore never hardened.

In France, squab is often pan-roasted, with a cream-colored crispy skin. In Chinese cuisine, the squab is usually fried, so it's served up whole and bronzed like Peking duck. In Morocco, squab is commonly served in a pastilla, an elaborate and pastry-centric take on the pot pie. While the first two preparations require a young, supple bird, the pastilla can use adult pigeon, too, as the slow-cooked process is enough to soften the more mature meat.

In the United States, the taste for pigeon meat remains rare, but the meat itself is rarer still. Schroeder recently had to remove squab from his menu at the Hungry Pigeon. His supplier—"a really nice Mennonite man named Joe Weaver who is the opposite of Purdue Chicken"—stopped selling the birds and the chef hasn't found another source of squab at a reasonable price. While a generic whole chicken costs around $1.50 a pound, a one-pound squab is typically 10 times that; depending on who you buy it from, prices for a whole pigeon can trend north of $25. “A hundred years ago, everyone was eating them,” Schroeder says. “Now, you can’t find them, unless you’re filthy rich.”

From the National Standard Squab Book (1921). Left page, top: "Squabs one week old." Left page, bottom: "Squabs two weeks old." Right page, top: "Squabs three weeks old." Right page, bottom: "Squabs four weeks old. Ready to be killed for market." Biodiversity Heritage Library

Tony Barwick is the owner of Palmetto Pigeon Plant, the largest squab producer in the United States. When he isn't dealing with calls from pigeon fiends like Lutz masquerading as restaurateurs, Barwick manages farm's 100,000 breeding pairs of pigeon. Each month, he says, the Sumter, South Carolina-based business aims to sell 40,000 to 50,000 squab. Barwick's birds can be found in "white tablecloth restaurants" and Chinatowns from New York to Los Angeles. "I've been backordered for 15 years," he says.

Though Palmetto's monthly output may sound big, it's nothing compared to pigeon's peers in poultry. The U.S. Department of Agriculture doesn't even track the nation's pigeon population, instead focusing primarily on chickens, chicken eggs, and turkeys. "We're a minor species," Barwick says. "I don't know how many squab are produced in the United States, but… let's say 22,000 a week. There's one chicken company in Sumter, South Carolina, they do 30,000 an hour in just that plant." After a poignant pause he adds, "In a hour what our entire industry does in a week."

Barwick acknowledges that part of the pigeon's problem is its bad reputation. But from an agricultural perspective, the real bottleneck is the bird's long babyhood. In the avian universe, most species develop quickly. Chickens, ducks, geese, and many other birds, are all precocial animals, meaning the newborns are mobile and reasonably mature from birth. While they still need to be protected, an infant chicken can start waddling—and, crucially, eating everyday food—from about the moment it cracks through its egg.

The pigeon, however, is an altricial bird, meaning the babies are helpless at birth. While it's possible that scientific manipulation could eventually turn squab into mass-produced meat, this fundamental facet of the pigeon's development makes things difficult. "A human baby is altricial," says Barwick. "So is a pigeon… It's born with its eyes shut, which means their parents have to regurgitate feed to them." Because the young are helpless, family units have to be kept relatively intact, and birds can't be forcibly fattened up. In the beginning, baby pigeons won't eat scattered bird seed, instead relying on so-called "pigeon milk," which is gurgled up from mom or dad's craw. This is why, on average, a pair of pigeons only produces two babies every 45 days. By contrast, a single female chicken in an artificially-lit environment can produce as much as one egg everyday, which, if they're inseminated and incubated, can turn into new chickens.

Pigeon problems aren't just a matter of maturity, however. They're also a matter of pure poundage: a pigeon doesn't weigh much. In four or five weeks, a squab tops out around a pound. In the same amount of time, a factory-farmed chicken will hit five pounds, thanks to selective breeding for broiler birds and other mass-production techniques like growth hormones. "It's like oysters," Schroder says of squab. "There's just not a whole lot there."

Still, it’s clear that some of squab’s inconveniences are also a part of its charm. Because it’s hard to produce and familiar primarily to foodies, it’s treated with more reverence than a chicken. While this keeps squabs out of the mouths of the masses, it’s actually great for business. After a severe decline in the 1960s and 70s, Barwick says demand for pigeon is back—even if most Americans remain oblivious to this particular source of protein.

“Most of our squab we sell into Asian markets in the United States,” he says. “They love squab.” In China, young pigeon meat pairs well with special occasions including weddings and holidays like Lunar New Year. Barwick says that the domestic squab industry started to bounce back after England and China brokered a deal to return Hong Kong to China. Hong Kong residents emigrated to the United States en masse in the 1980s, he explains, and brought their penchant for Peking duck and roast squab with them.

In more recent years, upscale restaurants have started to sell more squab, too. “We have these celebrities [like Julia Child, Alice Waters, and Emeril] who love squab and they’ve really pushed it, so we’ve seen domestic demand start to grow again and it’s that TV effect,” Barwick says. The unique taste and, of course, the relative scarcity of the bird, make it a mouth-watering menu item—for those who can afford it.

The combination of increased demand, a stagnated supply, and the bigger budgets of these white tablecloth establishments have all conspired to raise the price of the bird. While it’s easy to track down a host of midtown Manhattan restaurants, where one or six courses might be squab, finding the little bird in Chinatown is much harder. I found five Chinese restaurants in New York City that had squab on the menu, but only one actually kept it stocked—$18.95 a bird, head and all.

Arguably the worst part of city living. Pixnio

In many ways, the squab's spotty history is not unusual. At the turn of the 19th century, horse meat was all the rage. And during the Gold Rush, miners relied on turtles as a steady source of protein. What food appears unethical or unappetizing has always changed with the shifting sands of supply and demand.

What’s peculiar about the pigeon is our over-familiarity with the bird. We’ve all seen cows, pigs, and chickens, but few Americans encounter them on a daily basis, let alone share their stoops and streets with the critters. For devotees of French cuisine, the love of pigeon meat has actually enhanced their respect for the squab’s urbane cousin. “I like their resiliency and that they survive our environment,” Schroeder the chef says. “To me, they’re such an iconic bird.” But for the majority of people, negative encounters with the city bird means, even for a reasonable price, this particular meat will never make it on the menu.

Still, Barwick says Palmetto is planning to increase it production by nearly 50 percent. Over the next three years, he says, Palmetto intends to add 40,000 new breeding pairs. This increase may not be enough to substantially lower the price or convert chicken-lovers to the ways of the pigeon, but it's sure to provide pigeon devotees some relief. “Squab is perfect for one,” Lutz says, his Southern accent speeding up to deliver this final determination. “If I went with someone, I’d make them get their own. I wouldn’t share it.” If all goes well, he'll no longer have to.

0 notes

Text

Dairy Trade in Ethiopia: Current Scenario and Way Forward-Review- Juniper Publishers

Abstract

This review is concern on dairy trade in Ethiopia, current scenario and way forwards for enhancing dairy investment of Ethiopia. Consumers in Ethiopia come to be through formal and informal marketing system. The country spent over 678.75 million birrs to import various products of milk from 2006-2010 and the expenditure for powdered milk accounted for 79.6%, followed by cream, 12.9% and cheese 4.3%. Milk and its products market have changed significantly with strong global growth stemming in from the presence of evermore consumers in developing countries. To achieve the demand of milk and milk products in Ethiopia, it should be improve the genetic potential of dairy animal/cow- this could be through put in on genetic improvement on dairy animals, encouraging forage and fodder production and trade, establish agro-processing oil crops and use of by-products for animal feed, improving the productive, reproductive and weight gain performance of crossbreds, through enhanced provision of animal health services and better feed.

Keywords: Dairy Trade; Development policy; Milk market

Abbreviations: WTO: World Trade Organization; DDA: Dairy Development Agency; NFDM: Nonfat Dry Milk; DDE: Dairy Development Enterprise; DMY: Daily Milk Yield; WMP: Whole Milk Powder; SMP: Skim Milk Powder; GATT: General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade negotiations; LOD: Limit Of Determination; HACCP: Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point; DDMP: Dairy Development Master Plan; ADLI: Agriculture Development Led Industrialization; PRSP: Poverty Reduction Strategy Program; FSS: Food Security Strategy; RDPS: Rural Development Policy and Strategies; CBSP: Capacity Building Strategy and Program; AMS: Agricultural Marketing Strategies; IFD: Improved Family Dairy; BDS: Business Development Services

Introduction

World trade in dairy products has grown in recent decades at rates that generally exceed demand growth in developed countries which produce most the world’s dairy products [1]. In the world total milk production and trade is 816.0 and 73.2 million tones, respectively [2] (Figure 1). Milk and dairy products market have changed significantly with strong global growth stemming from the presence of evermore consumers in developing countries. The statistics showed a process of industrialization in the dairy chain with the marked presence of large national companies developing on the international scene and which also tend to concentrate the market [3]. Total world dairy exports grew by 4.6% per year on a milk equivalent basis during 2010–2014 [1] and the milk production also grew up 2.4% in 2014 a rate like previous years reaching 792 million tons. This is related with a favorable milk production outlook in most of the major exporting countries and continuous strong demand [4].

Ethiopia has one of the largest livestock inventories in Africa with a national herd estimated cattle population in Ethiopia is about 57.83 million, 28.04 million sheep, 28.61 million goats, 1.23 million camel and 60.51 million poultry. Out of 57.83 million cattle the female cattle constitute about 55.38% (32.0 million) and the remaining 44.55% (25.8 million) are male cattle. From the total cattle in the country 98.59% (57.01million) are local breeds and remaining are hybrid and exotic breeds that accounted for about 1.19% (706,793) and 0.14% (109,733), respectively [5]. Ethiopia holds large potential for dairy development particularly Ethiopian highlands possess a high potential for with diverse topographic and climatic conditions favorable for dairying [6]. Smallholder dairy farms in Ethiopia particularly in regional and zonal cities are alarmingly increasing because of high demand of milk and milk product from resident. However, the existing farming system which holds maximum of 10 or 15 cows per individual is not satisfactory to fulfill the demand. In addition, farming system has a major problem with regards to feed source, feed supply and the amount given per animal below the minimum standard, which entails in reduction in production and reproduction in the farms [7]. Livestock play a vital role in economic development; particularly as societies evolve from subsistence agriculture into cash-based economies [8]. Livestock in Ethiopia perform important functions in the livelihoods of farm owners, pastoralists and agro-pastoralists.

Dairy products in Ethiopia are channeled to consumers through formal and informal marketing systems [9]. The formal marketing system appeared to be expanding during the last decade with private farms entering the dairy processing. The informal market directly delivers dairy products by producers to consumer (immediate neighborhood or sales to itinerant traders or individuals in nearby towns). Generally, the low marketability of milk and milk products pose limitations on possibilities of exploring distant but rewarding markets. Therefore, improving position of dairy farmers to actively engage in markets and improve traditional processing techniques are important dairy value chain challenges of the country [10]. To develop dairy production system of Ethiopia, dairy supply and marketing system needs to undertake radical changes. To get access to distant markets farmers need to link up with manufacturers able to extend the shelf-life of farmers’ supply, as well as with traders and retailers, which can ensure a capillary distribution of final products. In short, dairy products cannot be expected to flow across Ethiopia unless a supply chain, bridging rural supply and urban demand is in place [6]. The country has not supplied the demand of milk and milk products because of different problem. To solve the problem or to increase the production of milk it should be focused on the policy and trade. Therefore, the objective of this review is to discuss on dairy trade in Ethiopia, current scenario and way forwards for enhancing dairy investment of Ethiopia.

Dairy Trade Development in World

Global dairy consumption has been on the rise steadily since 2005 except for 2009 and 2015. Trade in a large quantity (46%) of milk is informal [11] through short supply chains, and even with the formal trade most milk does not cross currency borders. The main reason dairy trade fell in 2009 was due to the global financial crisis. In 2015, dairy trade dropped by weaker demand for dairy commodities. The export subsidies received by European Union’s dairy farmers from their government contributed to lower international dairy prices and a weaker demand for dairy commodities (Figure 2). The increase in Europe’s dairy production grew faster than consumption. Dairy imports grew in value from $15 billion in 2005 to $43.2 billion in 2014, a 187% increase in US dollars. Similarly, global dairy exports expanded 175% in value from 2005 to 2014. The leading dairy importers from 2005 to 2009 were the United States, Mexico, Japan, Russia, and the European Union-28. From 2010 to 2015, the situation changed as China emerged as the world’s largest dairy importer followed by Russia, the US, Mexico, and Japan. Although the demographic landscapes of dairy consumption are changing globally, the major suppliers of dairy commodities have remained relatively unchanged from 2005 to 2015. New Zealand is the world’s largest dairy exporter in terms of volume. The four top global dairy exporters during the observed period based on value are the EU–28, New Zealand, the US, and Australia [12].

Over the last decade, interest in global dairy trade has intensified partially because of the enormous impact that domestic and international policies have had or are projected to have on the global trade and domestic supply. One significant example in the negotiations is the proposal made by the world trade organization (WTO) during the Nairobi ministerial in December 2015 in effort to help stabilize world dairy prices by eliminating export subsidies over the next four years. While many dairy commodities are traded internationally, some of the largest global exchanges involve cheese, nonfat dry milk (including skim dry milk), whey, and butter. In 2015 these four commodities accounted for 50% of the total value of global dairy imports. Of all the dairy commodities imported globally in 2015, cheese accounted for 24% of the total value [13].

Global dairy demand is estimated at approximately 15 million tons of product annually. The top 5 are China, Russia, Mexico, Japan and the USA. The US is the only major importer that is also a major net exporter. China imports ~2 million tons of dairy products annually, Russia ~1.4 million tons, Mexico and Japan over 500 thousand tons each. In addition, the US, Indonesia, Philippines, Saudi Arabia and Algeria import over 400 thousand tons and Singapore, Iraq, Malaysia, Venezuela and UAE importing over 300 thousand tons annually. Ethiopia exported an amount less than 300,000 USD per annum during the last five years. Majority of the export destined to Somalia and traditional spiced butter export for Ethiopian community and other consumers to USA and other countries. With the expansion of the sector the volume exported to Somalia can be increased and to other destinations like Sudan, South Sudan and Djibouti can be expanded. Nonfat dry milk (NFDM) was the second largest (in value) dairy commodity imported making up 11% of the world’s total dairy imports in 2015. The import value of NFDM grew by 96% from 2010 to 2014 and the top importers in 2015 included Mexico, China, Indonesia, and Malaysia. Whey and butter were the third and fourth largest dairy commodities imported, respectively. Both whey and butter balanced out at 7% of the total value of dairy imported in 2015. Over the five-year span from 2010 to 2014 the value of global imports of whey and butter increased by 81% and 62%, respectively. The world’s leading importers of whey are China, the US, and Indonesia, while Russia, Iran, and China are the leading importers of butter [14].

Dairy Production Development History in Ethiopia

Before started formal dairy production in early 1950s, dairy production in Ethiopia in the first half of 20th century was mostly traditional [2]. In 1947 the country has received 300 Friesian and Brown Swiss dairy cattle as a donation from the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration [15] to attempt the modern dairy production. With the introduction of these cattle in the country, commercial liquid milk production started on large farms in Addis Ababa and Asmera [16] and a small milk processing plant was established in Addis Ababa to support commercial dairy production [17]. During the second half of 1960s, dairy production around Addis Ababa began to develop rapidly due to demand and large private dairy farms and collection of milk from dairy farmers [2]. In 1971 Government established dairy development agency (DDA) to control and organize the collection, processing and distribution of locally produced milk, and facilitated the creation of dairy cooperatives to ease the provision of credit and technical and extension service to dairy producers [6]. Distribution of exotic dairy cattle particularly Holstein Friesian was done through government owned large-scale production such as WADU, ARDU and CADU. These units produced and distributed crossbred heifers, provided AI services and animal health service, in addition to forage production and marketing [18]. To establish the dairy development enterprise (DDE) numerous nationalized dairy farms (include large dairy farms, milk collection networks, and a processing plant) was merged in 1979 [17]. Distribution of exotic dairy cattle particularly Holstein Friesian was done through government owned large-scale production such as WADU, ARDU and CADU. These units produced and distributed crossbred heifers, provided AI services and animal health service, in addition to forage production and marketing [18]. The development of dairy sub sector is the shared effort of all stakeholders that explicitly and implicitly participate in the different activities of dairy development [19].

Currently, to bring market-oriented economic system, private sector begun to enter the dairy sector and market as an important actor the country’s policy reform. Many private investors have established small and large dairy farms. This commercial farm use grade and crossbred animals that have the potential to produce 1120-2500 litres over 279-day lactation. This production system is now expanding in the highlands among mixed crop-livestock farmers, such as those found in Selale, Ada’a and Holetta, and serves as the major milk supplier to the urban market. Additionally, some ten private investors and one cooperative union have established milk-processing plants to supply fresh processed milk and dairy products to Addis Ababa, Dire Dawa and Dessie towns. Most interventions during this period was focused on urban-based production and marketing. During the second half of the 1960s dairy production in the Addis Ababa area began to develop rapidly because of the expansion in large private dairy farms and the participation of smallholder producers [6].

Dairy Production Systems in Ethiopia

Dairy production is practiced almost all over Ethiopia involving a vast number of small subsistence and marketoriented farms [20,21], and is being practiced as an integral part of agricultural activities in Ethiopia since a time of immemorial. There are different types of milk production systems identified based on various criteria [22]. Based on climate, land holdings and integration with crop production as criterion, the dairy production system classified as rural (pastoralism, agro-pastoralism and highland mixed smallholder), peri-urban and urban [9,20,21,23]. The dairy sector in Ethiopia can also be categorized based on market-orientation, scale, and production intensity into three major production systems: traditional smallholder, private/ stateowned commercial4, and urban/ peri-urban [6].

Smallholder and commercial dairy farms are emerging mainly in the urban and peri-urban areas are located near or in proximity of Addis Ababa and regional towns and take the advantage of the urban markets. Urban dairy production system includes specialized, state and businessmen owned farms, but owners have no access to grazing land [24-26] and most Regional towns and Woredas [27]. Urban milk system in Addis Ababa consists of 5167 small, medium and large dairy farms producing 34.65 million liters of milk annually. Of the total urban milk production, 73% is sold, 10% is left for household consumption, 9.4% is fed to calves (excluding the amount directly suckled by the calves) and 7.6% is processed into butter and cottage cheese. In terms of marketing, 71% of the producers sell milk directly to consumers and the rest reaches to the consumers through intermediaries.

Peri-urban milk production system possesses animal types ranging from 50% crosses to the high-grade Friesian in small to medium-sized farms. The peri-urban milk system includes smallholder and commercial dairy farm owners in the proximity of Addis Ababa and other Regional towns. This sector owns most of the country`s improved dairy stock. The main source of feed is both homes produced or purchased hay; and the primary objective is to get additional cash income from milk sale. This production system is now expanding in the highlands among mixed croplivestock farm owners such as those found in Selale and Holetta and serves as the major milk supplier to the urban market [28]. The rural system is non-market oriented and most of the milk produced in this system is retained for home consumption and usually marketed through the informal market after the households satisfy their needs.

Milk Yield and Consumption Pattern

Most dairy products in the world are consumed in the region or country in which they are produced because of milk and its various derivatives are highly perishable products [29]. The estimate of total cow milk production for the rural sedentary areas of Ethiopia is about 3.06 billion liters [5]. The average daily milk yield (DMY) performances of indigenous cows in PLWs was 1.85 litres/day and ranged from 1.24 liters in rural lowland agro-pastoral system of Mieso to 2.31 litres in rural highland dairy production system of Fogera [30]. For hybrid cows, milk production per day per cow of 8 to 10 liters while their hybrid cow’s milk production per day is 11 to 15 liters [31]. In addition, the overall mean daily milk yield per liter per cow in western Oromiya were 2.2 ±0.6 and 6.5 ±1.6 for local and dairy breed [32]. Moreover, average daily milk yield of cross bred and local cows in Sululta were 9.56 ± 3.010 and 1.809 ± 0.4574 liter/day respectively. Moreover, the milk yield for crossbred and local cows in Wolmera areas were 8.60 ± 2.703 and 1.96 ± 0.8193 liters/day, respectively [33].

Currently Ethiopia’s milk consumption is only 19 liters per person 10% of Sudan’s and 20% of Kenya’s – but urbanization is driving up consumption per capita consumption in Addis Ababa is 52 liters per person [34]. The average expenditure on milk and products by Ethiopian household’s accounts for only 4% of the total household food budget. According to CSA [5] reported, from the total annual milk production, 42.38% used for household consumption, 6.12% sold, only 0.33% used for wages in kind and the rest 51.17% used for other purposes (could be to produce butter, cheese, and the likes). In rural area 59% and 41% of dairy farmers in Ada’a district, east Shawa zone sold raw milk through informal and formal milk marketing channels, respectively [35], but the finding of Valk & Tessema [36] is 98% of milk produced in rural area sold through informal chain whereas only 2% of the milk produced reached the final consumers through formal chain. According to Geleti & Eyassu [37,38] reported, there is no well-organized milk marketing system in Nekemte and Bako milk shed, and Dire Dawa. Dairy co-operatives and milk groups have facilitated the participation of smallholders in fluid milk markets in the Ethiopian highlands.

In Ethiopia, most consumers prefer unprocessed fluid milk due to its natural flavor (high fat content), availability, taste and lower price. Milk consumption in Ethiopia shows that most consumers prefer purchasing of raw milk because of its natural flavor (high fat content), availability and lower price. Ethiopians consume fewer dairy products than other African countries and far less than the world consumption. The present national average capita consumption of milk is much lower, 19kg/year as compared to 27kg for other African countries and 100kg to the world per capita consumption [39]. The recommended per capita milk consumption is 200 l/y. The consumption in Addis Ababa is very high (51.85 litres) as compared to the national and other towns. Indian milk production grew by 4.5%, Pakistan by 1.8%, Germany by 1.2%, and the USA by 1.1%. Brazil’s milk production decreased by 2.8% and New Zealand by 1.3% [40]. Generally, the demand for milk and milk products is higher in urban areas where there is high population pressure. The increasing trend of urbanization and population growth leads to the appearance and expansion of specialized medium-to-large scale dairy enterprises that collect, pasteurize, pack and distribute milk to consumers in different parts of the country [41].

Domestic and Export Market of Milk and Milk Product

Milk is channeled to consumers through formal and informal marketing systems [42]. The informal market involves direct delivery of milk by farmers to individual consumers in immediate neighborhood and sales to travelling traders or individuals in nearby towns. In informal market, milk may pass from producers to consumers directly or it may pass through two or more market agents. Ethiopia is not known to export dairy products; however, some insignificant quantities of milk and butter are exported to a few countries. Butter is mainly exported to Djibouti and South Africa (targeting the Ethiopians in Diaspora), while milk is solely exported to Somalia from the South Eastern Region of the country. As indicated by small quantities of cream are exported to Djibouti from Dire Dawa. The choice of targeting either domestic or export markets in the process of smallholder commercialization is basically linked to the nature of the targeted commodities [43]. For countries with large population size, domestic markets could also be a major market target due to higher domestic demand for both staples and high-value commodities [44]. In targeting the export market for the process of smallholder commercialization the issue of product quality, sanitary and phytosanitary standards, timely and regular supply, and volume need to be given emphasis in enabling the small-scale farmers to be part of the game [45].

The country spent over 678.75 million birrs to import various products of milk from 2006-2010. Expenditure on powdered milk accounted for 79.6%, followed by cream, 12.9% and cheese 4.3% [46]. With Ethiopia already spending approximately $10 million annually in foreign powdered milk imports, there is a huge opportunity for domestic UHT production to disrupt the current market. Investment size A $10-11 million greenfield investment would create a UHT plant with the largest processing capacity in the Ethiopian market Capacity 10,000 liters/hour (80,000 liters/ day, 24 million liters/year employment 500-600 employees estimated return IRR of 25-35% over 5 years.

International Market (Import Vs Export) in Milk and Milk Products

Only about 66.5 million tons or 8.3% of total world dairy production is traded internationally, excluding intra-EU trade. Dairy trade volumes increased by 6% from 2013 to 2014 compared to 2% growth between 2012 and 2013. International prices of all dairy products continued to decline from their 2013 peak for skim milk powder (SMP) and whole milk powder (WMP). A key factor was the decline in Chinese import demand, with demand for WMP dropping by 34% from 2014 levels. This decrease in Chinese demand for dairy products was coupled with continued production growth between 2014 and 2015 in key export markets, with total output of milk increasing in Australia (4%), European Union (2%), New Zealand (5%) and United States (1%) [47]. At global level demand for milk and milk products in developing countries is growing with rising incomes, population growth, urbanization and changes in diets. This trend is pronounced in East and Southeast Asia, particularly in highly populated countries such as China, Indonesia and Vietnam. The growing demand for milk and milk products offers a good opportunity for producers (and other actors in the dairy chain) in high-potential, peri-urban areas to enhance their livelihoods through increased production. Global milk production is estimated at approximately 735 billion litres annually.

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade negotiations (GATT), followed by those of the world trade organization (WTO) changed in the sense of liberating trade from all public intervention. A structural change in the shape and form of the main exporters and importers has taken place on the international dairy scene following this freeing-up of the market. International trade in milk and dairy products has exhibited quite large fluctuations over the last few decades, resulting in changes to public policies in western countries and their decisions stop subsidizing products. Significant growth in exports as well as imports of fresh drinking milk (whole and/or skimmed), milk powder (whole and/or skimmed), condensed whole milk and evaporated milk between 1960 and 2010. The European Union accounts for the largest share in total volume of exported and imported milk, even though its average annual rate of growth over the 25 years studied was just 0.25%. Worldwide new EU members, Oceania and Latin America have increased their share of total exported volumes. Milk production in 2015 was 6.4% higher than in 2014. In 2015 South Africa imported 69 354 t of dairy products, up 72.5% on the same period the previous year, and exported 61 296 t of dairy products, 13.8% down on 2014. International dairy product prices continued the extreme volatility and downward trend experienced since 2014 [48].

Technological developments in refrigeration and transportation only 7% of the milk produced are traded internationally if intra- EU trade is excluded. Trade in dairy products is very volatile as dairy trade flows can be affected by overall economic a situation in a country fluctuation in supply and demand, changing exchange rates and political measures. With demand for dairy products most rapidly rising in regions that are not self-sufficient in milk production, volumes of dairy trade are growing. Also, the share of global dairy production that is traded will increase as trade will grow at a faster pace than milk production. The developed countries account for 62 percent of the world’s dairy imports (measured in milk equivalents) and 93% of the exports, showing clearly that the major part of the global dairy trade takes place among developed countries [49].

International trade requirements for dairy

The international market for dairy products currently is far from having a single multinational processing firm [50]. Milk is perishable nature of dairy products, hygienic measures including heat treatment and cold storage are required to prevent hazardous bacterial contamination. By subjecting veterinary drugs and pesticides to strict authorization requirements, undesirable residue accumulation in dairy products is minimized. Other residues or contaminants, including diverse persistent environmental pollutants can accumulate in milk fat. Ensuring low levels of such pollutants in milk products requires adequate environmental protection. In the case of residues and contaminants that may constitute a danger to public health, regulations will set the maximum residue levels that are permitted in foodstuffs [51]. Especially in developing countries, but not exclusively there, it can be very difficult for farmers to meet private standards for milk quality and safety which might require investment in mechanical milking, on farm cooling, new feeds and genetic improvement. Apart from the initial investment cost a dairy farmer faces to meet those standards, also high operating costs might render small and even medium-scale units unprofitable in the long run.

There is different sanitary regulation apply both to dairy products and to the production processes. Regulation, which can be a mix of international recommendations and national legislation, is often dynamic. Regulation often is reactive: outbreaks of BSE in the UK and the associated fatalities of variant CJD in humans were followed by increased regulation of livestock products. In addition, rules develop in response to new scientific findings, albeit with a lag.

a. Sanitary product standards set targets for test results, and generally are composed of a maximum level of pathogenic load or contamination and the method for measurement. Micro bacterial standards apply to the dairy product as well as the raw milk inputs and are often measured by plate counts and cell counts. Tolerance levels also apply to contaminants such as residues of antibiotics or other veterinary medicine, mycotoxins and other ‘natural’ contaminants, or concentrations of food additives or pollution. Tolerances are set based on toxicological and epidemiological data that show effects on the health of humans and animals. The lower bound of a tolerance level is set by the limit of determination (LOD), which is the lowest possible concentration that can be picked up in a test. Due to the continuous progress of science and laboratory analyses, the LOD is continuously decreasing over time and moving ever closer to zero.

b. Process standards are used as a benchmark to judge whether a food has been produced in a manner to be fit for human consumption or trade. There are various required practices to ensure hygienic conditions of holdings and milk collection, processing plants, storage, and transport. Often, hygiene requirements demand a quality management scheme, such as hazard analysis critical control point (HACCP). A second important set of process standards applies to the health of the dairy cattle.

c. Conformity assessment is the provision of guarantees that the processes of hazard monitoring and control in the export firm are at least equivalent to those demanded by the importing country. The importing country has three mechanisms for enforcing that dairy shipments indeed meet its legal requirements: through certification, prior approval of handlers, and testing of the end-product.

Development Policy and Strategy

The current rural development policy and strategy of the country has some provisions indicating general direction for livestock development. Dairy Development Master Plan (DDMP) was formulated in 2002 to guide the sub-sector development and has been implemented since then across the regions. The DDMP highlights input and output targets but fails short of indicating roadmap and providing guidelines and principles to inform actual policy implementation on the ground. The uniqueness of each area means policy and development interventions must be customized. Whilst general guidelines and principles can be designed at national level, it is neither possible nor appropriate to design a master plan and implement throughout the country, or even throughout a province. Improving economic incentives to encourage innovations; pursuing value chain approach; providing public support to private sector development and private-public partnership; engaging in a holistic approach to technological innovations for increasing supply response; formulating policy and strategy to guide the sub-sector development, and strengthening capacity in local innovation systems with milk value chain perspective as strategic options for consideration by the relevant actors and stakeholders [52].

Trends in Development of the Dairy Sector in Ethiopia

Global milk production has been strong over the last several years leading to expanded growth in trade in most years with a sudden drop off in 2015. For example, from 2005 to 2013, the world milk production increased more than 16% [53]. An average of 594.4 million metric tons of cow milk was produced throughout the world over the observed nine-year period. The six major milk suppliers, the EU–28, the US, India, China, Russia, and Brazil accounted for more than 80% of the world’s cow milk production during the last four years EU–28 is the world’s largest milk producer, the greatest growth in milk production among the top six milk suppliers occurred in India and China. India’s cow milk production grew 15.3% from 2012 to 2015, while China production expanded by 15.1% Brazil milk production grew by 14.3%. Global dairy production is expected to continue to increase soon as world GDP raises and consumers’ preferences for different types of dairy products expand.

Opportunities and Challenges in Dairy Production Development in Ethiopia

Opportunities

Ethiopia holds large potential for dairy development due to its large livestock population, urbanization, emerging middle class consumer segments that are willing to embrace new products and services, demand for and consumption of milk, positive economic outlook, livestock genetic resources and production system, expected to increase processed dairy products consumption favorable climate for improved, export and foreign market possibility (Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan and Djibouti are potential foreign markets), indigenous knowledge, income generation and employment, and the relatively disease-free environment for livestock. In addition, the purchasing power increase, population growth and consumer awareness will increase the demand for quality, volume, graded and standardized products and traceability of sources. Land O’ Lakes in 2010 showed that the top 10% earners in Addis Ababa consumed about 38% of milk, while the lowest income group, approximately 61% of the population consumed only 23%.

Challenges

In Ethiopian the major constraints for dairy sector are shortage of feed at the end of dry, land shortage for establish improved forage, genetic limitation, limited access and high cost of dairy heifers/cows absence of an operational breeding strategy and policy, inadequate veterinary service provision, weak linkages between research, extension service providers and technology users, inadequate extension and training service, milk market related constraints, reproductive problems, lack of research and information exchange system, lack of education and consultation, socio-economic challenges and limited availability of credit to the dairy farmer.

Dairy marketing is a key constraint to dairy development throughout Sub-Saharan Africa. Marketing problems must be addressed if dairying is to realize its full potential to provide food and stimulate broad based agriculture and economic development. Because dairy development is sources of employment since it is labor intensive and associated with large incomes and price elasticity of demand. There is also risk of price decrease to suppliers related to dairy imports and food aid, and seasonal fall in demand due to cultural conditions. Adulteration is also believed to be a problem especially among the smallholders. Therefore, to increase milk productivity, it is necessary to eliminate the limiting factors and in turn exploit opportunities that could improve productivity of milk [54].

Major Trade Barriers to Dairy Products

Milk and dairy products are considered high-risk goods in production, consumption and trade. The risks, or perceived risks, are that milk products pose threats to food safety and animal health. As a result, dairy trade is subject to a considerable amount of regulation to limit the transfer of risk. Whereas such sanitary measures are generally applied for legitimate reasons, they can also be used in a protectionist manner, and such tendencies might increase with the further lowering of tariffs and expansion of tariff rate quotas [55]. High tariffs effectively block certain markets for exports or place severe restrictions through limited levels of quota access, high trade restrictions, combined with domestic support for dairy production, are common in the largest dairy markets such as Canada, the US, the EU and Japan. These trade restrictions are a key reason why only 7% of global dairy production is traded. Trade in dairy is expected to increase due to the rising demand for dairy products in emerging and developing markets.

Dairy Investment Policy Environment in Ethiopia (Figure 3)

The policy and regulatory environment influenced the country’s dairy sector characterized as free market economic system and the emergence of modern commercial dairying (1960 - 1974), socialist (Derg) regime that emphasized a centralized economic system and state farms (1974 - 1991) and free market and market liberalization (1991- present). The major goal of livestock policy programmed is to increase smallholders’ returns from investments in animal agriculture by providing them with essential information on government policies in the sector and developing appropriate policy and institutional options that will help improve livestock productivity, asset accumulation, promote sustainable use of natural resources and building capacity of policy makers and analysts [56]. Investment in dairy cattle breeds improvement in the MRS system through crossbreeding using AI and synchronization. For the five-year GTP II period, a total investment of ETB 148 million is needed to improve the capacity of the AI centers and the related service, and the training of AI technicians. The investment by the GoE to put in place the AI and synchronization services for the intervention is only ETB 148 million (very good leveraging by the GoE). Average milk production per crossbred cow per day in small specialized dairy increases from 10 to 12 litres (20% increase), in medium specialized dairy increases from 16 to 19.2 litres (20% increase), in small specialized dairy units increases from 2593 to 2746 litres (6% increase) and in medium specialized dairy units increases from 4608 to 5080 litres (10% increase) are the improvement objective crossbred dairy cattle in specialized dairy with the adoption of the interventions during the GTP II [57].

To meet the targets projected for 2020 government policy is important to create an environment conducive for innovation and risk taking on the part of investors (Figure 4). Delgado [58] identify four policy pillars for commercialization of smallholder dairying

a. Remove market distortions

b. Building participatory institutions of collective actions by small producers to facilitate their vertical integration

c. Increasing investment to improve productivity

d. Promoting effective regulatory institutions to deal with public health and environmental concerns of livestock intensification.

Current Scenario and Way Forward

The prospects of dairying seem to be bright because government is attempting them remedy through policies and strategies. Thus, dairy farmers are on the way to getting access to services and inputs that could help promote dairy production and productivity. This mainly includes feed and feeding, breeding services, credit, extension, training, veterinary services, and appropriate marketing system that addresses consumers’ demands etc. Since dairying is labor intensive, it promotes the motto of government policy in creating employment opportunities at house hold level. This improves employment, income and nutrition values of the family of the producers and the other demanders/consumers. The dairy industry would address and serve as one of the major instruments of the governments’ policy in achieving food security. This in turn promotes dairy production due to the attention of given by the government [59-63]. According to the 2014 GDP per capita statistics 0.4% of the population has consumption of 10-20 USD/day, 4.3% of the population 4-10 USD/day and 24.6% of the population 2-4 USD/day per capita. With the increase in income, it is expected that consumption pattern shifts to high value food items that demands encouraging supply of livestock products. The contribution of medium specialized dairy to GDP increases from ETB 353 million in 2015 to ETB 751 million in 2020. Milk trade in the dry lands, which is concentrated near towns, there is greater involvement of poorer herders, especially women than there generally is for live animal trade. However, opportunities for dairy trade in the dry lands (especially commerce in cow milk and butter) are limited mainly to urban and peri-urban areas where consumers are available and distance to markets is minimal.

Livestock development is guided by the broad policies of the government. These include the Agriculture Development Led Industrialization (ADLI), Poverty Reduction Strategy Program (PRSP), Food Security Strategy (FSS), Rural Development Policy and Strategies (RDPS), Capacity Building Strategy and Program (CBSP), Agricultural Marketing Strategies (AMS), foreign affairs and security policy and strategy, the export strategy, and the draft livestock breeding policy [64].

A future milk surplus could be realized through investment in better genetics, feed and health services, improving both traditional dairy farms and commercial-scale specialized dairy production units. The investment interventions proposed to improve cattle milk production and the value chain would transform family dairy farms in the highland moisture enough production zone from traditional to market-oriented improved family dairy (IFD) systems. These proposed interventions would also vastly increase the commercial-scale specialized dairy units as well as improve milk production from indigenous (or local) cattle breeds. Dairy co-operatives and Milk groups have facilitated the participation of smallholder in fluid milk markets in the Ethiopian highlands. Milk groups are a simple example of an agro-industrial innovation, but they are only a necessary first step in the process of developing more sophisticated co-operative organizations and well-functioning dairy markets [65,66]. The survival of the milk

groups that supply inputs and process and market dairy products will depend on their continued ability to capture value-added dairy processing and return that value-added to their members.

Evidence from Kenya emphasizes the importance of milk collection organizations in improving access to market and expanding productive bases. On the other hand, there is a need to stimulate consumption of dairy products in the country through various mechanisms, including school milk programmed as more consumption increase demand for dairy produce and can potentially encourage production in the long run. By increasing the number and productivity of cattle through improvements in genetics, health and feeding, domestic cow milk production will increase by about 93% by 2020, consumption demand will be satisfied, and export of cow milk and milk products will begin.

The following points should be implemented to growth the dairy trade

a. A clear understanding of potential market trends and opportunities is needed for policy and planning in the dairy sub-sector.

b. Public policy-makers should engage constructively with traditional markets to link them with formal modern industry.

c. Make investment in dairy co-operative development effective and pro-poor should be well managed, placed outside strong political forces and linked to strong demand.

d. There must be a link between agricultural research and growth in dairy development. Investment in dairy development through provision of appropriate credit and research technologies to smallholder producers will bring growth and shift producers towards greater commercial orientation, increasing their demand for improved technologies and innovations [67].

e. Imports and exports as well as macro policy and level of openness of the economy, can play a consistent role in the pace of dairy sector development. Import controls/ restrictions which is not for purposes of enforcing Sanitary Requirements and Food Safety Standards should be reduced or abolished. By so doing the role of domestic market protection will be relegated to ratification of dairy products.

f. Ethiopia dairy industry currently lacks some categories of products in terms of variety, quality and quantity. These include; cheeses, butter, milk powder, whey, yoghurts and ice cream. The processors can seek ways to increase capacity and invest aggressively in product development.

g. The performance of the few milk producing co-operatives operating so far has shown that the quantity of locally produced milk currently available to processors and consumers could be increased significantly if effective collection (quality controlplatform, chemical and microbiological) tests, transportation, cooling and marketing systems are put in place.

h. Milk producers’ organizations should provide ‘support services’ to increase clean milk production. An effective and well-trained animal health service should be available at any time to look after the health of animals, arrangements should be made for regular vaccination and checking against contagious diseases by the qualified veterinarians.

i. Formation of Dairy Board at national level and regional level are important for the development of the dairy industry [68]. Introduction of programs that will increase milk consumption (e.g. introduction of school milk program) price differentiation (i.e. premium price for high quality milk) are important for increasing milk production and consumption.

j. Addressing milk quality concerns and transforming the informal milk markets based on the concept of business development services (BDS), and be supervised by national regulatory authorities

k. As in many African countries, knowledge of hygiene is often not enough. Thus, the most important support services regarding clean milk production is “Extension –Education”.

Conclusion and Recommendation

Conclusion

Only about 66.5 million tons or 8.3% of total world dairy production is traded internationally, excluding intra-EU trade. Even if the demand is estimated 15 million tons of product annually, 816.0 million tons milk produced and the traded was 73.2 million tons. Over the last decade interest in global dairy trade has intensified partially because of the enormous impact that domestic and international policies have had or are projected to have on the global trade and domestic supply. In 2012-2016 Ethiopia imported more milk and milk products than exported (Figures 5 & 6). Though dairy sector in Ethiopia has a challenge, there are potential to development. Imports and exports as well as macro policy and level of openness of the economy, can play a consistent role in the pace of dairy sector development.

Recommendation

a. Should be develop marketing channels which can be used to promote the milk producers and dairy value chain actors, aware of the potential for increased production and marketing of specific products

b. Should be encourage licensed traders and qualitybased payments, strengthen the coordination between union, primary cooperatives and farmers and improve the effectiveness

c. Improve HACCP knowledge and skills and ensure milk producers, processors, transporters, retainers and collectors.

d. Dairy plants (like collection center, bulk cooling, transport, processing and distribution) should be organized to enhance formal marketing/trade

e. Should be set a clear market trends and opportunities policy and planning in the dairy sector

f. Strengthen investment in dairy co-operative development effective and pro-poor should be well managed, placed outside strong political forces and linked to strong demand

g. Should be encourage/develop quality control to increase consumer knowledge and demand for specific products

h. Improve milk production efficiency can be important through specific education and training

i. Improve milk production efficiency by investing high dairy herd size and create free access for investors in larger dairy farms with the best growth potential of livestock selection service recording system and strengthening project which supports investment and training in commercial dairy farms.

j. Training should be provide by professional for producers, dairy value chain actors, may include: skills and know-how on marketing and branding products to identify new opportunities at the dairy processing level; support for research and development initiatives for new dairy products; case studies and exposure to foreign experiences might stimulate creativity and entrepreneurship at the dairy processing level; a better understanding and a greater focus on market-driven value chains; knowledge of the requirements of food retailers is a precondition for the successful marketing of their products, better knowledge about these requirements may lead to opportunities for increased market participation; developing intermediary support structures that bring buyers and suppliers together is another initiative that can be undertaken at local and national levels.

k. Should be build the trust within farm communities and to improve awareness of the benefits of a more cooperative approach in terms of bargaining power and marketing strategy.

l. Develop or improve the image of the dairy sector by professionalizing the sector, to create better-quality jobs for young, well-educated people, and professional farms and a better marketing strategy for adding value, higher incomes and a more attractive dairy sector. More emphasis must be

placed on a young and successful entrepreneur profile to attract young people to the sector

Government should be fund for milk producers and investors based on their project proposal

To know more about journal of veterinary science impact factor: https://juniperpublishers.com/jdvs/index.php

To know more about Open Access Publishers: Juniper Publishers

0 notes