#Tomato Paste Factory China

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Everything You Must Know About The Tomato Paste Manufacturer

Tomato paste is one of the most versatile ingredients in the kitchens and food production facilities of the world, as it gives a rich taste. Whether you are an owner of a restaurant, manufacturer of food products, or simply a home chef, obtaining top-grade tomato paste makes all the difference in your finished product. A reliable manufacturer of tomato paste guarantees that the product delivered will satisfy not only your culinary but also business requirements. Are you someone who wants to gather more facts about the tomato paste manufacturer, tomato paste manufacturers in China? If Yes. This is the best place where people can gather more facts about the tomato paste manufacturer, tomato paste manufacturers in China.

Quality production

Companies from China have built their name based on the premise that it is possible for tomato paste manufacture to deliver good quality. Tomatoes from these countries are ripened perfectly, and immediately processed for minimal loss to retain its flavor and richness in nutritional value. From selecting the best raw materials to implementing cutting-edge technology, Chinese manufacturers produce tomato paste that maintains a consistent taste, texture, and color, making it ideal for both large-scale food production and everyday cooking.

Cost-Effective Bulk Sourcing

Its price competitiveness has made China the destination of choice for buyers seeking large-scale tomato paste supplies. Through such Chinese manufacturing companies, businesses will enjoy significantly reduced procurement costs. Such is more beneficial to restaurants, food producers, and catering companies since they need significant volumes of tomato paste in producing their products. Buying in large quantities also reduces the time intervals between restocking, and this helps companies that have engaged in mass food production manage their supply chain better.

Chinese tomato paste producers are known for their reliable schedules and consistent quality of products, so that companies always have the ingredients in their hands. Moreover, most of these producers are devoted to sustainability, with eco-friendly practices and certifications that are consistent with global environmental standards.

Hence, it will save much if quality could be maintained constantly as well as providing timely and unbroken supplies from such reliable tomato paste manufactures in China. For a business within the food industry, getting top-notch quality tomato paste in China, one of which has rich flavor in it with variability in cooking purposes, could have a good competitive edge among other firms.

#tomato paste factory china#canned tomato paste china#chinese tomato paste#good quality canned tomatoes

0 notes

Text

Agency Career (CIA Field Agent, Raised Since Birth; 1985-2024)

1989: Drop of Berlin Wall, informed tip to Holy See on Rabbi Anatole; vice and collegiate draft, of athletes wife. Polish Jewish labor mills, Gentile produced pork; isolated Israeli produce, to Arabia.

1992: Removal of amphetamines from children's medicine, IQ test revealed passage on State Police Captain's examination at maximum level; other child, converted Converso, allowed to return as Judaism; end of Sino-Judaic movement, Egyptian.

1996: Informed tip on Andrew Wachowski, Carrie-Anne Moss, and Raven Laventi, for enslavement of dominatrixes, preferred wives of Garfield Lodge rules, however as submissives, as if common prostitutes; rule reformed, 1860s, President James Garfield, Battle of Shiloh; wars won, Vicksburg, and Wilderness.

1999: Murder of Alice C. O'Neill, claimed named Charlebois, for Colombian betrayal into Likud, past war advisors of Chinese enemy; signals of CVS German-Israel alliance with PRCC-Diet, Japanese South Korean transit. Dragonball produced, at siding with North Korea, and the People's Republic of Communist China. Future trade partners, under George W. Bush, "Joshua Tree".

2003: Yeltsin revealed through Hopkinton, Massachusetts, as center basin of school shootings, beginning in 1990s; Holocaust History Museum, disapproval of temporary lesbianism, for shame of being Holocaust victims; German-Israel revealed as being the prime conspiracy, Israelis thrown out of orders as Wehrmacht. Rise of George Soros, Romalian, having had a precognitive accident, on motorway, dueling Mossad.

2004: Revealing of External Security pimping scandal, through Hamas; beginning of mathematical frequency, planted by Wiccans, Confederate-Catholics, to reform with African and Asian communities. Spanish pimping, "Ali", Episcopal drafts, "Popeye", Irish cops, "Blintzen", German spies, "Schnitzel", and remaining endeavors, Russian factories, "Google", African voudoun, "Mosey", and British fascist, "Mandatory".

2006: Sheriff's Cajun, of Fugitive Slave Act, removed through frame of Marvel Comics, under auspice of Hell's Angels; Third Degree interrogation, of Lairds of gender therapy, the mating of wives to unusual genomes of logic. Shut down, by lesbian accusations, the combined Kampuchean logic of all tribals associated, having been declared as poorly invertebrate. Friends Stand United, contacted, for Hollywood hit; the Foreign Office, readmission to destiny. The CIA's blessing, given, to learn new lessons.

2010: Suicide Squad on print; dietary disorders, of major operatives, offered as medicine and pills; except for Captain Boomerang, tomato sauce, potentially deadly kill ratio; "Vile", "Vava"; Doctor Ciel Mallory, Alice O'Neill.

2013: Murder of Whitey Bulger, for releasing secret that the Beatles, was anti-British, and that homosexual children steal brides, through the "Beatles", on forged check proxy of self, on strike to head; with lesbians, allowed to marry, however caged and hazed and brutally murdered, if a fan of American music of British recording studio print.

2016: Separation of factory unions, white supremacists, ordered, for African civil rights, blacks being the foundational bedrock of community, opposed to Asians; simpleton little people, working in small factories, without any ability to express own face. Racial inferiors, compared to Africans; Africans incapable of murder, Asians incapable of yielding. John Rocker.

2020: Mass quandry quarry, of INTERPOL, Unitarians, Tong, MI-6, and Abwehr, as Art Bell subscribers, held in prison facilities apart from wives and children; children turned over to CIA indentures, as orphans, to become proper Americans, as State Police Colonels; any dissenting, ignored by news, their supporting journalists indemnified, by Mayor Wu, of Boston.

2024: Gay leaders outed, as George W. Bush, Kim Jong-un, and Crown Prince William; having claimed own condition, is the other, the inability to produce a child, instead adopting under false claim; German-Mormon.

0 notes

Text

Taste Test: Bubly and Chinese Lay's

For a bit of a change of pace, I figured I'd write about some snacks I recently tried.

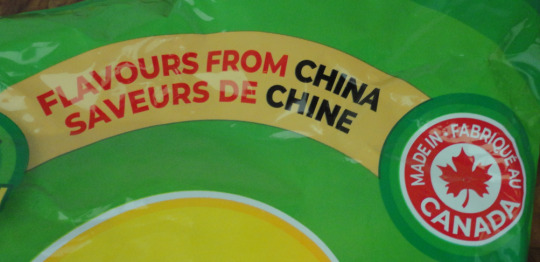

Apparently these are the two most popular Lay's flavors in China, so they've been made permanently available here.

As we all know GG is a snack lover, and he especially loves Lay's chips. He used to endorse them a while back and there have been occasional rumors that he'll be endorsing them again (they never materialize into anything).

I've seen photos of GG eating cucumber Lay's in the past, but unfortunately I couldn't find any for this post.

Here's one of his old ads.

The man can make even chocolate covered potato chips look appetizing.

I am actually glad that he doesn't endorse Lay's anymore, because I have a weakness for Lay's potato chips and I don't need any extra excuses to indulge!

Western Paranoia

They really want the consumer to know: while these are Chinese flavors, they are made in Canada! Don't worry, honorable Canadian, these were made in a trusted Canadian factory with trusted Canadian ingredients, not in some shady Chinese factory where who-knows-what is being thrown into the mix! 😅

Cucumber Lay's

These chips were a real shocker. I don't know what I was expecting, but these look like sour cream and onion chips, and they taste... like cucumbers. Not like pickles or marinated cucumbers or something, but like cucumbers plucked fresh out of the garden.

They also smell very strongly of fresh cucumbers, the moment the bag is opened. I found it off-putting.

...

I respect that these chips exist, but I wouldn't choose to eat them. 😅

My partner, on the other hand, has already devoured half the bag. I'm at least glad they won't be going to waste!

Verdict: 1/5 🏞️🏗️🏗️🏗️🏗️

Chicken and Tomato Lay's

Chicken and tomato... I was trying to think of any occasion in my cooking where I would put these two ingredients together, and I really couldn't. Maybe in a chicken taco or something? Or Chicken Parmesan (which I'd probably never make)? It seems such an odd flavor combination to me for some reason.

These taste exactly like tomato and chicken, and it's surprisingly good. The chicken flavor is savoury and the tomato flavor is a bit sweeter, so those who are into the whole 'sweet and salty' thing might really enjoy these.

My only complaint is that they are a bit too sweet for my taste (sweet in the way store-bought ketchup is sweet, as opposed to sweet like candy). I am much more into savoury flavors than sweets, and this was just a bit over the edge of sweetness to where I don't think I could eat many of these.

Verdict: 2/5 🐞🐞🪳🪳🪳

Blackberry Bubly

Wow, I was NOT expecting how amazing this would be. It is fresh and fruity with absolutely no sweetness. It smells as good as it tastes, too, and fills the air with the refreshing smell of berries.

I have always scoffed at the idea of paying for what is just flavored club soda. It seems perverse and excessive in some strange way. But when I tried this I immediately knew that I was going to be buying more Bubly, without a doubt.

And then I reflected on it some more and realized, pretty much everything we drink, whether tea, coffee, ginger ale or whiskey is all just flavored water in the end.

The fact that this is really simply flavored is a feature, not a bug.

I love that there is a delicious, refreshing fizzy drink option that has no sugar and absolutely no sweetness (nor any chemicals or food colorings). Bright and clean and flavorful. This will be perfect in the summer.

The funny thing is, I don't even like blackberry. At least, that's what I thought before I tried this. Blackberry wouldn't have been my first choice by any stretch of the imagination. But the only single cans available were blackberry and lime and I felt lime was too generic a flavor to really get the 'Bubly experience'. After all, club soda with lime is something I'd probably normally drink in the summer.

But the blackberry is absolutely delicious. So fruity and refreshing.

I can now confidently buy the grapefruit Bubly I've been eyeing every time I'm at the grocery store. I'm sure I'll drink every can. Maybe I'll post about it once I've given it a try...

Verdict: 4/5 🛼🛼🛼🛼⛸️

Anyway, hope this was interesting. If I come across anything else that I think is relevant, especially if it's something GG and DD endorse, I'll try to do something like this again.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

kaddish, allen ginsberg

I Strange now to think of you, gone without corsets & eyes, while I walk on the sunny pavement of Greenwich Village. downtown Manhattan, clear winter noon, and I’ve been up all night, talking, talking, reading the Kaddish aloud, listening to Ray Charles blues shout blind on the phonograph the rhythm the rhythm—and your memory in my head three years after—And read Adonais’ last triumphant stanzas aloud—wept, realizing how we suffer— And how Death is that remedy all singers dream of, sing, remember, prophesy as in the Hebrew Anthem, or the Buddhist Book of Answers—and my own imagination of a withered leaf—at dawn— Dreaming back thru life, Your time—and mine accelerating toward Apocalypse, the final moment—the flower burning in the Day—and what comes after, looking back on the mind itself that saw an American city a flash away, and the great dream of Me or China, or you and a phantom Russia, or a crumpled bed that never existed— like a poem in the dark—escaped back to Oblivion— No more to say, and nothing to weep for but the Beings in the Dream, trapped in its disappearance, sighing, screaming with it, buying and selling pieces of phantom, worshipping each other, worshipping the God included in it all—longing or inevitability?—while it lasts, a Vision—anything more? It leaps about me, as I go out and walk the street, look back over my shoulder, Seventh Avenue, the battlements of window office buildings shouldering each other high, under a cloud, tall as the sky an instant—and the sky above—an old blue place. or down the Avenue to the south, to—as I walk toward the Lower East Side—where you walked 50 years ago, little girl—from Russia, eating the first poisonous tomatoes of America—frightened on the dock— then struggling in the crowds of Orchard Street toward what?—toward Newark— toward candy store, first home-made sodas of the century, hand-churned ice cream in backroom on musty brownfloor boards— Toward education marriage nervous breakdown, operation, teaching school, and learning to be mad, in a dream—what is this life? Toward the Key in the window—and the great Key lays its head of light on top of Manhattan, and over the floor, and lays down on the sidewalk—in a single vast beam, moving, as I walk down First toward the Yiddish Theater—and the place of poverty you knew, and I know, but without caring now—Strange to have moved thru Paterson, and the West, and Europe and here again, with the cries of Spaniards now in the doorstoops doors and dark boys on the street, fire escapes old as you -Tho you’re not old now, that’s left here with me— Myself, anyhow, maybe as old as the universe—and I guess that dies with us—enough to cancel all that comes—What came is gone forever every time— That’s good! That leaves it open for no regret—no fear radiators, lacklove, torture even toothache in the end— Though while it comes it is a lion that eats the soul—and the lamb, the soul, in us, alas, offering itself in sacrifice to change’s fierce hunger—hair and teeth—and the roar of bonepain, skull bare, break rib, rot-skin, braintricked Implacability. Ai! ai! we do worse! We are in a fix! And you’re out, Death let you out, Death had the Mercy, you’re done with your century, done with God, done with the path thru it—Done with yourself at last—Pure—Back to the Babe dark before your Father, before us all—before the world— There, rest. No more suffering for you. I know where you’ve gone, it’s good. No more flowers in the summer fields of New York, no joy now, no more fear of Louis, and no more of his sweetness and glasses, his high school decades, debts, loves, frightened telephone calls, conception beds, relatives, hands— No more of sister Elanor,.—she gone before you—we kept it secret—you killed her—or she killed herself to bear with you—an arthritic heart—But Death’s killed you both—No matter— Nor your memory of your mother, 1915 tears in silent movies weeks and weeks—forgetting, aggrieve watching Marie Dressler address humanity, Chaplin dance in youth, or Boris Godunov, Chaliapin’s at the Met, hailing his voice of a weeping Czar—by standing

room with Elanor & Max—watching also the Capitalists take seats in Orchestra, white furs, diamonds, with the YPSL’s hitch-hiking thru Pennsylvania, in black baggy gym skirts pants, photograph of 4 girls holding each other round the waste, and laughing eye, too coy, virginal solitude of 1920 all girls grown old, or dead, now, and that long hair in the grave—lucky to have husbands later— You made it—I came too—Eugene my brother before (still grieving now and will gream on to his last stiff hand, as he goes thru his cancer—or kill—later perhaps—soon he will think—) And it’s the last moment I remember, which I see them all, thru myself, now—tho not you I didn’t foresee what you felt—what more hideous gape of bad mouth came first—to you—and were you prepared? To go where? In that Dark—that—in that God? a radiance? A Lord in the Void? Like an eye in the black cloud in a dream? Adonoi at last, with you? Beyond my remembrance! Incapable to guess! Not merely the yellow skull in the grave, or a box of worm dust, and a stained ribbon—Deathshead with Halo? can you believe it? Is it only the sun that shines once for the mind, only the flash of existence, than none ever was? Nothing beyond what we have—what you had—that so pitiful—yet Triumph, to have been here, and changed, like a tree, broken, or flower—fed to the ground—but mad, with its petals, colored, thinking Great Universe, shaken, cut in the head, leaf stript, hid in an egg crate hospital, cloth wrapped, sore—freaked in the moon brain, Naughtless. No flower like that flower, which knew itself in the garden, and fought the knife—lost Cut down by an idiot Snowman’s icy—even in the Spring—strange ghost thought—some Death—Sharp icicle in his hand—crowned with old roses—a dog for his eyes—cock of a sweatshop—heart of electric irons. All the accumulations of life, that wear us out—clocks, bodies, consciousness, shoes, breasts—begotten sons—your Communism—‘Paranoia’ into hospitals. You once kicked Elanor in the leg, she died of heart failure later. You of stroke. Asleep? within a year, the two of you, sisters in death. Is Elanor happy? Max grieves alive in an office on Lower Broadway, lone large mustache over midnight Accountings, not sure. l His life passes—as he sees—and what does he doubt now? Still dream of making money, or that might have made money, hired nurse, had children, found even your Immortality, Naomi? I’ll see him soon. Now I’ve got to cut through—to talk to you—as I didn’t when you had a mouth. Forever. And we’re bound for that, Forever—like Emily Dickinson’s horses—headed to the End. They know the way—These Steeds—run faster than we think—it’s our own life they cross—and take with them. Magnificent, mourned no more, marred of heart, mind behind, married dreamed, mortal changed—Ass and face done with murder. In the world, given, flower maddened, made no Utopia, shut under pine, almed in Earth, balmed in Lone, Jehovah, accept. Nameless, One Faced, Forever beyond me, beginningless, endless, Father in death. Tho I am not there for this Prophecy, I am unmarried, I’m hymnless, I’m Heavenless, headless in blisshood I would still adore Thee, Heaven, after Death, only One blessed in Nothingness, not light or darkness, Dayless Eternity— Take this, this Psalm, from me, burst from my hand in a day, some of my Time, now given to Nothing—to praise Thee—But Death This is the end, the redemption from Wilderness, way for the Wonderer, House sought for All, black handkerchief washed clean by weeping—page beyond Psalm—Last change of mine and Naomi—to God’s perfect Darkness—Death, stay thy phantoms! II Over and over—refrain—of the Hospitals—still haven’t written your history—leave it abstract—a few images run thru the mind—like the saxophone chorus of houses and years—remembrance of electrical shocks. By long nites as a child in Paterson apartment, watching over your nervousness—you were fat—your next move— By that afternoon I stayed home from school to take care of you—once and for all—when I vowed forever that once man disagreed with my opinion of the cosmos, I was lost— By my

later burden—vow to illuminate mankind—this is release of particulars—(mad as you)—(sanity a trick of agreement)— But you stared out the window on the Broadway Church corner, and spied a mystical assassin from Newark, So phoned the Doctor—‘OK go way for a rest’—so I put on my coat and walked you downstreet—On the way a grammarschool boy screamed, unaccountably—‘Where you goin Lady to Death’? I shuddered— and you covered your nose with motheaten fur collar, gas mask against poison sneaked into downtown atmosphere, sprayed by Grandma— And was the driver of the cheesebox Public Service bus a member of the gang? You shuddered at his face, I could hardly get you on—to New York, very Times Square, to grab another Greyhound— where we hung around 2 hours fighting invisible bugs and jewish sickness—breeze poisoned by Roosevelt— out to get you—and me tagging along, hoping it would end in a quiet room in a Victorian house by a lake. Ride 3 hours thru tunnels past all American industry, Bayonne preparing for World War II, tanks, gas fields, soda factories, diners, loco-motive roundhouse fortress—into piney woods New Jersey Indians—calm towns—long roads thru sandy tree fields— Bridges by deerless creeks, old wampum loading the streambeddown there a tomahawk or Pocahontas bone—and a million old ladies voting for Roosevelt in brown small houses, roads off the Madness highway— perhaps a hawk in a tree, or a hermit looking for an owl-filled branch— All the time arguing—afraid of strangers in the forward double seat, snoring regardless—what busride they snore on now? ‘Allen, you don’t understand—it’s—ever since those 3 big sticks up my back—they did something to me in Hospital, they poisoned me, they want to see me dead—3 big sticks, 3 big sticks— ‘The Bitch! Old Grandma! Last week I saw her, dressed in pants like an old man, with a sack on her back, climbing up the brick side of the apartment ‘On the fire escape, with poison germs, to throw on me—at night—maybe Louis is helping her—he’s under her power— ‘I’m your mother, take me to Lakewood’ (near where Graf Zeppelin had crashed before, all Hitler in Explosion) ‘where I can hide.’ We got there—Dr. Whatzis rest home—she hid behind a closet—demanded a blood transfusion. We were kicked out—tramping with Valise to unknown shady lawn houses—dusk, pine trees after dark—long dead street filled with crickets and poison ivy— I shut her up by now—big house REST HOME ROOMS—gave the landlady her money for the week—carried up the iron valise—sat on bed waiting to escape— Neat room in attic with friendly bedcover—lace curtains—spinning wheel rug—Stained wallpaper old as Naomi. We were home. I left on the next bus to New York—laid my head back in the last seat, depressed—the worst yet to come?—abandoning her, rode in torpor—I was only 12. Would she hide in her room and come out cheerful for breakfast? Or lock her door and stare thru the window for sidestreet spies? Listen at keyholes for Hitlerian invisible gas? Dream in a chair—or mock me, by—in front of a mirror, alone? 12 riding the bus at nite thru New Jersey, have left Naomi to Parcae in Lakewood’s haunted house—left to my own fate bus—sunk in a seat—all violins broken—my heart sore in my ribs—mind was empty—Would she were safe in her coffin— Or back at Normal School in Newark, studying up on America in a black skirt—winter on the street without lunch—a penny a pickle—home at night to take care of Elanor in the bedroom— First nervous breakdown was 1919—she stayed home from school and lay in a dark room for three weeks—something bad—never said what—every noise hurt—dreams of the creaks of Wall Street— Before the gray Depression—went upstate New York—recovered—Lou took photo of her sitting crossleg on the grass—her long hair wound with flowers—smiling—playing lullabies on mandolin—poison ivy smoke in left-wing summer camps and me in infancy saw trees— or back teaching school, laughing with idiots, the backward classes—her Russian specialty—morons with dreamy lips, great eyes, thin feet & sicky fingers, swaybacked, rachitic— great heads pendulous

over Alice in Wonderland, a blackboard full of C A T. Naomi reading patiently, story out of a Communist fairy book—Tale of the Sudden Sweetness of the Dictator—Forgiveness of Warlocks—Armies Kissing— Deathsheads Around the Green Table—The King & the Workers—Paterson Press printed them up in the ’30s till she went mad, or they folded, both. O Paterson! I got home late that nite. Louis was worried. How could I be so—didn’t I think? I shouldn’t have left her. Mad in Lakewood. Call the Doctor. Phone the home in the pines. Too late. Went to bed exhausted, wanting to leave the world (probably that year newly in love with R my high school mind hero, jewish boy who came a doctor later—then silent neat kid— I later laying down life for him, moved to Manhattan—followed him to college—Prayed on ferry to help mankind if admitted—vowed, the day I journeyed to Entrance Exam— by being honest revolutionary labor lawyer—would train for that—inspired by Sacco Vanzetti, Norman Thomas, Debs, Altgeld, Sand-burg, Poe—Little Blue Books. I wanted to be President, or Senator. ignorant woe—later dreams of kneeling by R’s shocked knees declaring my love of 1941—What sweetness he’d have shown me, tho, that I’d wished him & despaired—first love—a crush— Later a mortal avalanche, whole mountains of homosexuality, Matterhorns of cock, Grand Canyons of asshole—weight on my melancholy head— meanwhile I walked on Broadway imagining Infinity like a rubber ball without space beyond—what’s outside?—coming home to Graham Avenue still melancholy passing the lone green hedges across the street, dreaming after the movies—) The telephone rang at 2 A.M.—Emergency—she’d gone mad—Naomi hiding under the bed screaming bugs of Mussolini—Help! Louis! Buba! Fascists! Death!—the landlady frightened—old fag attendant screaming back at her— Terror, that woke the neighbors—old ladies on the second floor recovering from menopause—all those rags between thighs, clean sheets, sorry over lost babies—husbands ashen—children sneering at Yale, or putting oil in hair at CCNY—or trembling in Montclair State Teachers College like Eugene— Her big leg crouched to her breast, hand outstretched Keep Away, wool dress on her thighs, fur coat dragged under the bed—she barricaded herself under bedspring with suitcases. Louis in pajamas listening to phone, frightened—do now?—Who could know?—my fault, delivering her to solitude?—sitting in the dark room on the sofa, trembling, to figure out— He took the morning train to Lakewood, Naomi still under bed—thought he brought poison Cops—Naomi screaming—Louis what happened to your heart then? Have you been killed by Naomi’s ecstasy? Dragged her out, around the corner, a cab, forced her in with valise, but the driver left them off at drugstore. Bus stop, two hours’ wait. I lay in bed nervous in the 4-room apartment, the big bed in living room, next to Louis’ desk—shaking—he came home that nite, late, told me what happened. Naomi at the prescription counter defending herself from the enemy—racks of children’s books, douche bags, aspirins, pots, blood—‘Don’t come near me—murderers! Keep away! Promise not to kill me!’ Louis in horror at the soda fountain—with Lakewood girlscouts—Coke addicts—nurses—busmen hung on schedule—Police from country precinct, dumbed—and a priest dreaming of pigs on an ancient cliff? Smelling the air—Louis pointing to emptiness?—Customers vomiting their Cokes—or staring—Louis humiliated—Naomi triumphant—The Announcement of the Plot. Bus arrives, the drivers won’t have them on trip to New York. Phonecalls to Dr. Whatzis, ‘She needs a rest,’ The mental hospital—State Greystone Doctors—‘Bring her here, Mr. Ginsberg.’ Naomi, Naomi—sweating, bulge-eyed, fat, the dress unbuttoned at one side—hair over brow, her stocking hanging evilly on her legs—screaming for a blood transfusion—one righteous hand upraised—a shoe in it—barefoot in the Pharmacy— The enemies approach—what poisons? Tape recorders? FBI? Zhdanov hiding behind the counter? Trotsky mixing rat bacteria in the back of the store? Uncle Sam in Newark, plotting deathly

perfumes in the Negro district? Uncle Ephraim, drunk with murder in the politician’s bar, scheming of Hague? Aunt Rose passing water thru the needles of the Spanish Civil War? till the hired $35 ambulance came from Red Bank——Grabbed her arms—strapped her on the stretcher—moaning, poisoned by imaginaries, vomiting chemicals thru Jersey, begging mercy from Essex County to Morristown— And back to Greystone where she lay three years—that was the last breakthrough, delivered her to Madhouse again— On what wards—I walked there later, oft—old catatonic ladies, gray as cloud or ash or walls—sit crooning over floorspace—Chairs—and the wrinkled hags acreep, accusing—begging my 13-year-old mercy— ‘Take me home’—I went alone sometimes looking for the lost Naomi, taking Shock—and I’d say, ‘No, you’re crazy Mama,—Trust the Drs.’— And Eugene, my brother, her elder son, away studying Law in a furnished room in Newark— came Paterson-ward next day—and he sat on the broken-down couch in the living room—‘We had to send her back to Greystone’— —his face perplexed, so young, then eyes with tears—then crept weeping all over his face—‘What for?’ wail vibrating in his cheekbones, eyes closed up, high voice—Eugene’s face of pain. Him faraway, escaped to an Elevator in the Newark Library, his bottle daily milk on windowsill of $5 week furn room downtown at trolley tracks— He worked 8 hrs. a day for $20/wk—thru Law School years—stayed by himself innocent near negro whorehouses. Unlaid, poor virgin—writing poems about Ideals and politics letters to the editor Pat Eve News—(we both wrote, denouncing Senator Borah and Isolationists—and felt mysterious toward Paterson City Hall— I sneaked inside it once—local Moloch tower with phallus spire & cap o’ ornament, strange gothic Poetry that stood on Market Street—replica Lyons’ Hotel de Ville— wings, balcony & scrollwork portals, gateway to the giant city clock, secret map room full of Hawthorne—dark Debs in the Board of Tax—Rembrandt smoking in the gloom— Silent polished desks in the great committee room—Aldermen? Bd of Finance? Mosca the hairdresser aplot—Crapp the gangster issuing orders from the john—The madmen struggling over Zone, Fire, Cops & Backroom Metaphysics—we’re all dead—outside by the bus stop Eugene stared thru childhood— where the Evangelist preached madly for 3 decades, hard-haired, cracked & true to his mean Bible—chalked Prepare to Meet Thy God on civic pave— or God is Love on the railroad overpass concrete—he raved like I would rave, the lone Evangelist—Death on City Hall—) But Gene, young,—been Montclair Teachers College 4 years—taught half year & quit to go ahead in life—afraid of Discipline Problems—dark sex Italian students, raw girls getting laid, no English, sonnets disregarded—and he did not know much—just that he lost— so broke his life in two and paid for Law—read huge blue books and rode the ancient elevator 13 miles away in Newark & studied up hard for the future just found the Scream of Naomi on his failure doorstep, for the final time, Naomi gone, us lonely—home—him sitting there— Then have some chicken soup, Eugene. The Man of Evangel wails in front of City Hall. And this year Lou has poetic loves of suburb middle age—in secret—music from his 1937 book—Sincere—he longs for beauty— No love since Naomi screamed—since 1923?—now lost in Greystone ward—new shock for her—Electricity, following the 40 Insulin. And Metrazol had made her fat. So that a few years later she came home again—we’d much advanced and planned—I waited for that day—my Mother again to cook & —play the piano—sing at mandolin—Lung Stew, & Stenka Razin, & the communist line on the war with Finland—and Louis in debt��,uspected to he poisoned money—mysterious capitalisms —& walked down the long front hall & looked at the furniture. She never remembered it all. Some amnesia. Examined the doilies—and the dining room set was sold— the Mahogany table—20 years love—gone to the junk man—we still had the piano—and the book of Poe—and the Mandolin, tho needed some string, dusty— She went to the backroom to lie down in

bed and ruminate, or nap, hide—I went in with her, not leave her by herself—lay in bed next to her—shades pulled, dusky, late afternoon—Louis in front room at desk, waiting—perhaps boiling chicken for supper— ‘Don’t be afraid of me because I’m just coming back home from the mental hospital—I’m your mother—’ Poor love, lost—a fear—I lay there—Said, ‘I love you Naomi,’—stiff, next to her arm. I would have cried, was this the comfortless lone union?—Nervous, and she got up soon. Was she ever satisfied? And—by herself sat on the new couch by the front windows, uneasy—cheek leaning on her hand—narrowing eye—at what fate that day— Picking her tooth with her nail, lips formed an O, suspicion—thought’s old worn vagina—absent sideglance of eye—some evil debt written in the wall, unpaid—& the aged breasts of Newark come near— May have heard radio gossip thru the wires in her head, controlled by 3 big sticks left in her back by gangsters in amnesia, thru the hospital—caused pain between her shoulders— Into her head—Roosevelt should know her case, she told me—Afraid to kill her, now, that the government knew their names—traced back to Hitler—wanted to leave Louis’ house forever. One night, sudden attack—her noise in the bathroom—like croaking up her soul—convulsions and red vomit coming out of her mouth—diarrhea water exploding from her behind—on all fours in front of the toilet—urine running between her legs—left retching on the tile floor smeared with her black feces—unfainted— At forty, varicosed, nude, fat, doomed, hiding outside the apartment door near the elevator calling Police, yelling for her girlfriend Rose to help— Once locked herself in with razor or iodine—could hear her cough in tears at sink—Lou broke through glass green-painted door, we pulled her out to the bedroom. Then quiet for months that winter—walks, alone, nearby on Broadway, read Daily Worker—Broke her arm, fell on icy street— Began to scheme escape from cosmic financial murder-plots—later she ran away to the Bronx to her sister Elanor. And there’s another saga of late Naomi in New York. Or thru Elanor or the Workmen’s Circle, where she worked, ad-dressing envelopes, she made out—went shopping for Campbell’s tomato soup—saved money Louis mailed her— Later she found a boyfriend, and he was a doctor—Dr. Isaac worked for National Maritime Union—now Italian bald and pudgy old doll—who was himself an orphan—but they kicked him out—Old cruelties— Sloppier, sat around on bed or chair, in corset dreaming to herself—‘I’m hot—I’m getting fat—I used to have such a beautiful figure before I went to the hospital—You should have seen me in Woodbine—’ This in a furnished room around the NMU hall, 1943. Looking at naked baby pictures in the magazine—baby powder advertisements, strained lamb carrots—‘I will think nothing but beautiful thoughts.’ Revolving her head round and round on her neck at window light in summertime, in hypnotize, in doven-dream recall— ‘I touch his cheek, I touch his cheek, he touches my lips with his hand, I think beautiful thoughts, the baby has a beautiful hand.’— Or a No-shake of her body, disgust—some thought of Buchenwald—some insulin passes thru her head—a grimace nerve shudder at Involuntary (as shudder when I piss)—bad chemical in her cortex—‘No don’t think of that. He’s a rat.’ Naomi: ‘And when we die we become an onion, a cabbage, a carrot, or a squash, a vegetable.’ I come downtown from Columbia and agree. She reads the Bible, thinks beautiful thoughts all day. ‘Yesterday I saw God. What did he look like? Well, in the afternoon I climbed up a ladder—he has a cheap cabin in the country, like Monroe, N.Y. the chicken farms in the wood. He was a lonely old man with a white beard. ‘I cooked supper for him. I made him a nice supper—lentil soup, vegetables, bread & butter—miltz—he sat down at the table and ate, he was sad. ‘I told him, Look at all those fightings and killings down there, What’s the matter? Why don’t you put a stop to it? ‘I try, he said—That’s all he could do, he looked tired. He’s a bachelor so long, and he likes lentil

soup.’ Serving me meanwhile, a plate of cold fish—chopped raw cabbage dript with tapwater—smelly tomatoes—week-old health food—grated beets & carrots with leaky juice, warm—more and more disconsolate food—I can’t eat it for nausea sometimes—the Charity of her hands stinking with Manhattan, madness, desire to please me, cold undercooked fish—pale red near the bones. Her smells—and oft naked in the room, so that I stare ahead, or turn a book ignoring her. One time I thought she was trying to make me come lay her—flirting to herself at sink—lay back on huge bed that filled most of the room, dress up round her hips, big slash of hair, scars of operations, pancreas, belly wounds, abortions, appendix, stitching of incisions pulling down in the fat like hideous thick zippers—ragged long lips between her legs—What, even, smell of asshole? I was cold—later revolted a little, not much—seemed perhaps a good idea to try—know the Monster of the Beginning Womb—Perhaps—that way. Would she care? She needs a lover. Yisborach, v’yistabach, v’yispoar, v’yisroman, v’yisnaseh, v’yishador, v’yishalleh, v’yishallol, sh’meh d’kudsho, b’rich hu. And Louis reestablishing himself in Paterson grimy apartment in negro district—living in dark rooms—but found himself a girl he later married, falling in love again—tho sere & shy—hurt with 20 years Naomi’s mad idealism. Once I came home, after longtime in N.Y., he’s lonely—sitting in the bedroom, he at desk chair turned round to face me—weeps, tears in red eyes under his glasses— That we’d left him—Gene gone strangely into army—she out on her own in N.Y., almost childish in her furnished room. So Louis walked downtown to postoffice to get mail, taught in highschool—stayed at poetry desk, forlorn—ate grief at Bickford’s all these years—are gone. Eugene got out of the Army, came home changed and lone—cut off his nose in jewish operation—for years stopped girls on Broadway for cups of coffee to get laid—Went to NYU, serious there, to finish Law.— And Gene lived with her, ate naked fishcakes, cheap, while she got crazier—He got thin, or felt helpless, Naomi striking 1920 poses at the moon, half-naked in the next bed. bit his nails and studied—was the weird nurse-son—Next year he moved to a room near Columbia—though she wanted to live with her children— ‘Listen to your mother’s plea, I beg you’—Louis still sending her checks—I was in bughouse that year 8 months—my own visions unmentioned in this here Lament— But then went half mad—Hitler in her room, she saw his mustache in the sink—afraid of Dr. Isaac now, suspecting that he was in on the Newark plot—went up to Bronx to live near Elanor’s Rheumatic Heart— And Uncle Max never got up before noon, tho Naomi at 6 A.M. was listening to the radio for spies—or searching the windowsill, for in the empty lot downstairs, an old man creeps with his bag stuffing packages of garbage in his hanging black overcoat. Max’s sister Edie works—17 years bookkeeper at Gimbels—lived downstairs in apartment house, divorced—so Edie took in Naomi on Rochambeau Ave— Woodlawn Cemetery across the street, vast dale of graves where Poe once—Last stop on Bronx subway—lots of communists in that area. Who enrolled for painting classes at night in Bronx Adult High School—walked alone under Van Cortlandt Elevated line to class—paints Naomiisms— Humans sitting on the grass in some Camp No-Worry summers yore—saints with droopy faces and long-ill-fitting pants, from hospital— Brides in front of Lower East Side with short grooms—lost El trains running over the Babylonian apartment rooftops in the Bronx— Sad paintings—but she expressed herself. Her mandolin gone, all strings broke in her head, she tried. Toward Beauty? or some old life Message? But started kicking Elanor, and Elanor had heart trouble—came upstairs and asked her about Spydom for hours,—Elanor frazzled. Max away at office, accounting for cigar stores till at night. ‘I am a great woman—am truly a beautiful soul—and because of that they (Hitler, Grandma, Hearst, the Capitalists, Franco, Daily News, the ’20s, Mussolini, the living

dead) want to shut me up—Buba’s the head of a spider network—’ Kicking the girls, Edie & Elanor—Woke Edie at midnite to tell her she was a spy and Elanor a rat. Edie worked all day and couldn’t take it—She was organizing the union.—And Elanor began dying, upstairs in bed. The relatives call me up, she’s getting worse—I was the only one left—Went on the subway with Eugene to see her, ate stale fish— ‘My sister whispers in the radio—Louis must be in the apartment—his mother tells him what to say—LIARS!—I cooked for my two children—I played the mandolin—’ Last night the nightingale woke me / Last night when all was still / it sang in the golden moonlight / from on the wintry hill. She did. I pushed her against the door and shouted ‘DON’T KICK ELANOR!’—she stared at me—Contempt—die—disbelief her sons are so naive, so dumb—‘Elanor is the worst spy! She’s taking orders!’ ‘—No wires in the room!’—I’m yelling at her—last ditch, Eugene listening on the bed—what can he do to escape that fatal Mama—‘You’ve been away from Louis years already—Grandma’s too old to walk—’ We’re all alive at once then—even me & Gene & Naomi in one mythological Cousinesque room—screaming at each other in the Forever—I in Columbia jacket, she half undressed. I banging against her head which saw Radios, Sticks, Hitlers—the gamut of Hallucinations—for real—her own universe—no road that goes elsewhere—to my own—No America, not even a world— That you go as all men, as Van Gogh, as mad Hannah, all the same—to the last doom—Thunder, Spirits, lightning! I’ve seen your grave! O strange Naomi! My own—cracked grave! Shema Y’Israel—I am Svul Avrum—you—in death? Your last night in the darkness of the Bronx—I phonecalled—thru hospital to secret police that came, when you and I were alone, shrieking at Elanor in my ear—who breathed hard in her own bed, got thin— Nor will forget, the doorknock, at your fright of spies,—Law advancing, on my honor—Eternity entering the room—you running to the bathroom undressed, hiding in protest from the last heroic fate— staring at my eyes, betrayed—the final cops of madness rescuing me—from your foot against the broken heart of Elanor, your voice at Edie weary of Gimbels coming home to broken radio—and Louis needing a poor divorce, he wants to get married soon—Eugene dreaming, hiding at 125 St., suing negroes for money on crud furniture, defending black girls— Protests from the bathroom—Said you were sane—dressing in a cotton robe, your shoes, then new, your purse and newspaper clippingsno—your honesty— as you vainly made your lips more real with lipstick, looking in the mirror to see if the Insanity was Me or a earful of police. or Grandma spying at 78—Your vision—Her climbing over the walls of the cemetery with political kidnapper’s bag—or what you saw on the walls of the Bronx, in pink nightgown at midnight, staring out the window on the empty lot— Ah Rochambeau Ave.—Playground of Phantoms—last apartment in the Bronx for spies—last home for Elanor or Naomi, here these communist sisters lost their revolution— ‘All right—put on your coat Mrs.—let’s go—We have the wagon downstairs—you want to come with her to the station?’ The ride then—held Naomi’s hand, and held her head to my breast, I’m taller—kissed her and said I did it for the best—Elanor sick—and Max with heart condition—Needs— To me—‘Why did you do this?’—‘Yes Mrs., your son will have to leave you in an hour’—The Ambulance came in a few hours—drove off at 4 A.M. to some Bellevue in the night downtown—gone to the hospital forever. I saw her led away—she waved, tears in her eyes. Two years, after a trip to Mexico—bleak in the flat plain near Brentwood, scrub brush and grass around the unused RR train track to the crazyhouse— new brick 20 story central building—lost on the vast lawns of madtown on Long Island—huge cities of the moon. Asylum spreads out giant wings above the path to a minute black hole—the door—entrance thru crotch— I went in—smelt funny—the halls again—up elevator—to a glass door on a Women’s Ward—to Naomi—Two nurses buxom white—They led her out, Naomi

stared—and I gaspt—She’d had a stroke— Too thin, shrunk on her bones—age come to Naomi—now broken into white hair—loose dress on her skeleton—face sunk, old! withered—cheek of crone— One hand stiff—heaviness of forties & menopause reduced by one heart stroke, lame now—wrinkles—a scar on her head, the lobotomy—ruin, the hand dipping downwards to death— O Russian faced, woman on the grass, your long black hair is crowned with flowers, the mandolin is on your knees— Communist beauty, sit here married in the summer among daisies, promised happiness at hand— holy mother, now you smile on your love, your world is born anew, children run naked in the field spotted with dandelions, they eat in the plum tree grove at the end of the meadow and find a cabin where a white-haired negro teaches the mystery of his rainbarrel— blessed daughter come to America, I long to hear your voice again, remembering your mother’s music, in the Song of the Natural Front— O glorious muse that bore me from the womb, gave suck first mystic life & taught me talk and music, from whose pained head I first took Vision— Tortured and beaten in the skull—What mad hallucinations of the damned that drive me out of my own skull to seek Eternity till I find Peace for Thee, O Poetry—and for all humankind call on the Origin Death which is the mother of the universe!—Now wear your nakedness forever, white flowers in your hair, your marriage sealed behind the sky—no revolution might destroy that maidenhood— O beautiful Garbo of my Karma—all photographs from 1920 in Camp Nicht-Gedeiget here unchanged—with all the teachers from Vewark—Nor Elanor be gone, nor Max await his specter—nor Louis retire from this High School— Back! You! Naomi! Skull on you! Gaunt immortality and revolution come—small broken woman—the ashen indoor eyes of hospitals, ward grayness on skin— ‘Are you a spy?’ I sat at the sour table, eyes filling with tears—‘Who are you? Did Louis send you?—The wires—’ in her hair, as she beat on her head—‘I’m not a bad girl—don’t murder me!—I hear the ceiling—I raised two children—’ Two years since I’d been there—I started to cry—She stared—nurse broke up the meeting a moment—I went into the bathroom to hide, against the toilet white walls ‘The Horror’ I weeping—to see her again—‘The Horror’—as if she were dead thru funeral rot in—‘The Horror!’ I came back she yelled more—they led her away—‘You’re not Allen—’ I watched her face—but she passed by me, not looking— Opened the door to the ward,—she went thru without a glance back, quiet suddenly—I stared out—she looked old—the verge of the grave—‘All the Horror!’ Another year, I left N.Y.—on West Coast in Berkeley cottage dreamed of her soul—that, thru life, in what form it stood in that body, ashen or manic, gone beyond joy— near its death—with eyes—was my own love in its form, the Naomi, my mother on earth still—sent her long letter—& wrote hymns to the mad—Work of the merciful Lord of Poetry. that causes the broken grass to be green, or the rock to break in grass—or the Sun to be constant to earth—Sun of all sunflowers and days on bright iron bridges—what shines on old hospitals—as on my yard— Returning from San Francisco one night, Orlovsky in my room—Whalen in his peaceful chair—a telegram from Gene, Naomi dead— Outside I bent my head to the ground under the bushes near the garage—knew she was better— at last—not left to look on Earth alone—2 years of solitude—no one, at age nearing 60—old woman of skulls—once long-tressed Naomi of Bible— or Ruth who wept in America—Rebecca aged in Newark—David remembering his Harp, now lawyer at Yale or Srul Avrum—Israel Abraham—myself—to sing in the wilderness toward God—O Elohim!—so to the end—2 days after her death I got her letter— Strange Prophecies anew! She wrote—‘The key is in the window, the key is in the sunlight at the window—I have the key—Get married Allen don’t take drugs—the key is in the bars, in the sunlight in the window. Love, your mother’ which is Naomi— Hymmnn In the world which He has created according to his will Blessed Praised Magnified Lauded

Exalted the Name of the Holy One Blessed is He! In the house in Newark Blessed is He! In the madhouse Blessed is He! In the house of Death Blessed is He! Blessed be He in homosexuality! Blessed be He in Paranoia! Blessed be He in the city! Blessed be He in the Book! Blessed be He who dwells in the shadow! Blessed be He! Blessed be He! Blessed be you Naomi in tears! Blessed be you Naomi in fears! Blessed Blessed Blessed in sickness! Blessed be you Naomi in Hospitals! Blessed be you Naomi in solitude! Blest be your triumph! Blest be your bars! Blest be your last years’ loneliness! Blest be your failure! Best be your stroke! Blest be the close of your eye! Blest be the gaunt of your cheek! Blest be your withered thighs! Blessed be Thee Naomi in Death! Blessed be Death! Blessed be Death! Blessed be He Who leads all sorrow to Heaven! Blessed be He in the end! Blessed be He who builds Heaven in Darkness! Blessed Blessed Blessed be He! Blessed be He! Blessed be Death on us All! III Only to have not forgotten the beginning in which she drank cheap sodas in the morgues of Newark, only to have seen her weeping on gray tables in long wards of her universe only to have known the weird ideas of Hitler at the door, the wires in her head, the three big sticks rammed down her back, the voices in the ceiling shrieking out her ugly early lays for 30 years, only to have seen the time-jumps, memory lapse, the crash of wars, the roar and silence of a vast electric shock, only to have seen her painting crude pictures of Elevateds running over the rooftops of the Bronx her brothers dead in Riverside or Russia, her lone in Long Island writing a last letter—and her image in the sunlight at the window ‘The key is in the sunlight at the window in the bars the key is in the sunlight,’ only to have come to that dark night on iron bed by stroke when the sun gone down on Long Island and the vast Atlantic roars outside the great call of Being to its own to come back out of the Nightmare—divided creation—with her head lain on a pillow of the hospital to die —in one last glimpse—all Earth one everlasting Light in the familiar black-out—no tears for this vision— But that the key should be left behind—at the window—the key in the sunlight—to the living—that can take that slice of light in hand—and turn the door—and look back see Creation glistening backwards to the same grave, size of universe, size of the tick of the hospital's clock on the archway over the white door— IV O mother what have I left out O mother what have I forgotten O mother farewell with a long black shoe farewell with Communist Party and a broken stocking farewell with six dark hairs on the wen of your breast farewell with your old dress and a long black beard around the vagina farewell with your sagging belly with your fear of Hitler with your mouth of bad short stories with your fingers of rotten mandolins with your arms of fat Paterson porches with your belly of strikes and smokestacks with your chin of Trotsky and the Spanish War with your voice singing for the decaying overbroken workers with your nose of bad lay with your nose of the smell of the pickles of Newark with your eyes with your eyes of Russia with your eyes of no money with your eyes of false China with your eyes of Aunt Elanor with your eyes of starving India with your eyes pissing in the park with your eyes of America taking a fall with your eyes of your failure at the piano with your eyes of your relatives in California with your eyes of Ma Rainey dying in an aumbulance with your eyes of Czechoslovakia attacked by robots with your eyes going to painting class at night in the Bronx with your eyes of the killer Grandma you see on the horizon from the Fire-Escape with your eyes running naked out of the apartment screaming into the hall with your eyes being led away by policemen to an aumbulance with your eyes strapped down on the operating table with your eyes with the pancreas removed with your eyes of appendix operation with your eyes of abortion with your eyes of ovaries removed with your eyes of shock with your

eyes of lobotomy with your eyes of divorce with your eyes of stroke with your eyes alone with your eyes with your eyes with your Death full of Flowers V Caw caw caw crows shriek in the white sun over grave stones in Long Island Lord Lord Lord Naomi underneath this grass my halflife and my own as hers caw caw my eye be buried in the same Ground where I stand in Angel Lord Lord great Eye that stares on All and moves in a black cloud caw caw strange cry of Beings flung up into sky over the waving trees Lord Lord O Grinder of giant Beyonds my voice in a boundless field in Sheol Caw caw the call of Time rent out of foot and wing an instant in the universe Lord Lord an echo in the sky the wind through ragged leaves the roar of memory caw caw all years my birth a dream caw caw New York the bus the broken shoe the vast highschool caw caw all Visions of the Lord Lord Lord Lord caw caw caw Lord Lord Lord caw caw caw Lord Paris, December 1957—New York, 1959

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rules: List the first lines of your last 20 stories (if you have less than 20, just list them all!) See if there are any patterns. Choose your favourite opening line. Then tag 10 of your favourite authors!

Well the one pattern I can see is that I have way too many wips, damn my flighty muse

I’m tagging anyone willing to do this one

1. The Weapons of our warfare are not of the flesh (Nicolò di Genova/Yusuf al Kaysani, The Old Guard

Yusuf wasn’t even sure what he was doing, taking the invader with him. He should have left the man behind after the Franks took the city, but when he’d seen the look on the Christian’s face, that thousand mile stare in the other’s eyes, he’d been unable to do so. There had been a plea in the way he knelt there, not even reaching for a weapon, though he and Yusuf had killed each other dozens of times by now. Almost as if he wanted Yusuf to kill him. That might have been why he stayed his blade at first, that notion that he couldn’t give the other what he wanted, not after what the Franks had done. But then he’d seen the man’s eyes and he hadn’t been able to stop himself from feeling pity for him.

2. The Body Remembers (Scott McCall/Theo Raeken, Teen Wolf

He had flinched.

3. We come from Warriors (gen fic, with some Nicky/Joe , The Old Guard)

Solomon hesitated as he reached the door. He didn't want to go in. Not now, not when Mom would have prettied up the room, trying to achieve holiday cheer, desperate to pretend things were normal, that there wasn't another empty chair at the table. He was about ready to just turn around, to take his gifts back to the car and leave, go to a bar, and drink soda after soda, until he got on too much of a high and had to head out in his car, driving till the carbohydrate high was out of his system.

4.Artefacts of history (Nicky/Joe, Andy/Quynh, Nile, The Old Guard)

His first thought was ‘another one’.

5. Sinking Down (Gen, Andy and Booker, The Old Guard)

Booker wasn’t even sure why he was in this damn room, with these people, none of whom had a clue who he was, or what he’d done. They all had their issues of course, and he wasn’t stupid enough to assume that anything he went through was worse than what they went through.

6. Tomatoes, lettuce and a burger (Gen, Dean and Sam Winchester, Supernatural)

Dean wasn’t sure what it was that made it feel like his heart was torn to pieces. Sam was sitting right there, mere inches away from him. Reading, writing, Dean wasn’t sure what his brother was doing as Dean himself was cooking.

7. A Soldier goes marching on (gen, Nile Freeman, and Jay, The Old Guard)

Jay stared at he empty bunk. Dizzy wouldn’t even look at her. Jay would have screamed at her, but she knew it wasn’t fair, since her anger was aimed as much at herself as it was at Dizzy. And neither would do any good.

8. New Wolf in the Old Guard (Teen Wolf/The Old Guard crossover, Scott centric)

Scott woke up gasping for air. It was the third time this week that he had the dream of drowning. The other dreams were weird, and scary, but he’d have any of them over the ones where he drowned.

9. Good Little Milker (Dean Winchester, Supernatural a/b/o au)

Dean was still sulking. Sam could see it in the poor Omega cow's eyes, the way he glared at the both of them, when he thought Sam or Dad weren't looking. Oh sure, he was playing nice after the rough spanking Dad had given him. Dad had had no choice after Dean's initial tantrum when John had mentioned what was going to happen. It hadn't really been a surprise to anyone but Dean himself, when Sam's younger brother had presented as an Omega. Even during the first signs of his first heat, the boy had still been hoping to present at least as a beta if not an Alpha. But both Sam and John had known better. Dean was a brat, but he'd always been at his happiest when Dad or Sam told him what to do.

10. Clean (JDM/Jensen Ackles, spn rps, non-con)

Jeff couldn't believe his luck. The notion that this perfect piece of slave flesh had never once been fucked was probably the biggest waste of a slave's body he'd ever seen in his life.

11. Light in the Basement (Jensen Ackles/Jared Padalecki, spn rps, non-con)

Jensen wasn't even sure what had happened as he slowly woke up face down on a dusty floor. He stared up at the room he was in. It was dark, stuffy, like there was something in his throat making it hard to breathe. There was a pervading smell of shit and mold hanging around the place, like he was in a badly cleaned toilet in one of the factories he'd been working at over the past few months. He crawled up into the dark

12. The Treaty (Jensen Ackles/Jared Padalecki, spn rps, a/b/o, dub-con)

Peace. After ten years of war, it was long awaited, and even from the throne room, Jared could hear the celebrations spreading across the capitol city. Jared wished he could join the people, spend time with his loved ones and hold his mother, but all he could think of was his father's face as he'd died in Jared's arms.

13. the Wolf who Ran with Hunters (gen Teen Wolf/Supernatural, Scott-centric)

Scott shivered as he woke up. He didn’t want to open his eyes, because once he did, he’d have to accept that he was all alone in some crappy motel room. Outside the window, he could see the dusty town in Oklahoma which he didn’t even know the name of.

14. Covered in Bandaids (Scott McCall/Isaac Lahey, Teen Wolf)

Isaac wasn’t quite sure what he was doing at the field. He shouldn’t even care about lacrosse any more. He was strong now, and lacrosse had been something he’d done because his father wanted him to be more like Camden.

15. Breaking Point (Scott McCall/Theo Raeken, Teen Wolf)

The place was cold. Even with the increased body heat of a werewolf Scott shivered in the corner of the cell. He wished he’d been wearing more than a tank top and his jeans when the cops had burst into his room. They hadn’t told him what he was being arrested for, or what they wanted, which as far as he knew, was not the norm.

16. Kindness for the Devil (Lucifer Morningstar/Scott McCall, Lucifer/Teen Wolf)

It was a night like any other. Things were a bit too quiet over at Lux, but then it was early, and it seemed to make Linda happy, making her more likely to stay instead of having her take Charlie and leaving.

17.Can’t Always hold him back (Stiles Stilinski/Derek Hale, Teen Wolf)

Scott looked down at Stiles, carefully listening to his friend’s heartbeat, pushing out the distraction of outside noise. Nurses and visitors talking in the hall outside, the beeping of the machine monitoring Stiles. He desperately tried to follow the pattern. It scared him, how hard his friend’s heart was working just to keep going, how difficult Stiles’ breathing went even with the oxygen mask covering his mouth and nose. Scott had finally managed to get the sheriff to go downstairs to have something to eat, maybe even take a shower if Mom could slip him into the staff showers. They all knew that their stay here could end up being a marathon that might last days more than it already had.

18. Beloved (Btvs/Angel, co written with @spikesheart)

Sitting at one end of a fully laden table, Buffy looked at the appetizers piled on the finest bone china sitting atop platinum charger plates, studied her matching platinum silverware, and wrangled with the finely woven silver linen napkin in her lap – patently avoiding her lover’s gaze as he sat at the other end. Only the best of everything life had to offer was laid out before her. A wide variety of catered pasta, meat and vegetable dishes filled every square inch of space in between them, yet nothing caught her fancy.

19. Parent Wolf (Teen Wolf, the parents)

She woke up in an endless white room, found her head leaning against the bark of an old tree trunk, staring up and noticing several other men and women waking up alongside her.

20. Missed Shot (gen, teen wolf, Scott-centric)

Scott stared up at the men coming closer and at the man who had just shot him with an arrow. Derek Hale, the creepy guy who’d lured him here in the first place, tried to grab him and pull him loose, but seconds later he was down on the ground as well with arrows in his leg and back. Scott stared around in fear, pulling at the arrow, too scared to think of breaking it free.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

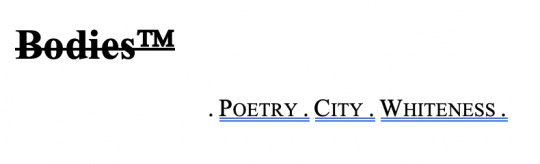

(ESSAY) ‘BodiesTM: Poetry. City. Whiteness.’ by Elliot C. Mason

A provocation on whiteness, futurity, capitalism and the fricative movements of racialised and gendered embodiment in contemporary poetics, by Elliot C. Mason.

//

> Capitalism keeps time in a centrifugal swirl that expands as space. The myth of the future is sucked in to the endless present of working time, the working day that never ends but rather blurrily recalibrates its always-changing relation to the past (the time before Capital, that horrific barbarism which could be called Communism, Africa or Keynesian Social Capitalism, depending on the context) and the future. The mythical future is total temporal accumulation, when the life-times of the disenfranchised are finally worth nothing and the life-times of the Tech-Execs, the Winners, the Exemplary Individuals are worth so much time that they have reached secular eternity: a capitalist immortality. The working time of people is pulled into the blurring vortex, this weightless phantasmagoria, and it expands imperially, ideologically, a waxed leg in steel-capped boots, over geographical codes. The move is architectural, strategically ordering bodies under spatial blocks and signs.

// James Nixon / Ars Poetica #5 //

//

> The violent horror of this vortex is that it is not there at all. We cannot see it. Our way of seeing is mutually constituted with what we see; Capital’s expansion is simply our sight. Precisely what makes capitalism so different to other ways of organising money and people is that it takes over everything. It destroys religion and becomes God itself. It makes every interaction geared towards accumulation. Dating is like opening a betting account, like browsing estate agents’ windows. The end of a relationship in 2019 is not when you stop seeing each other – it’s when you find each other on a dating app. But this has been happening since the beginnings of this system. Modern sciences are ways of justifying slavery, which Capital needed to produce far more than feudal farmers ever could; the city and its divisive architecture are a response to the need to keep laborers close to factories, to houses given by the factory-owners, to food provided by the factory-owners: to the total subsumption of life in a single Capital. In the beginning there was nothing, and then we traded commodities to accumulate labortime in the imperial movement of endlessly expanding architecture.

…

our new home has cockroaches. an exterminator came –

…

it’s smart how the poisoned gel spreads through the colony by cannibalism. he explains that they will eat their family, that the poison will spread faster that way.

/ AK Blakemore / nymphs //

//

> The creation of the body and its technological assemblages that constitute race and racial thinking are necessary components of these movements. The body in other systems is dependent on context: there is the body on the farm who picks tomatoes, the body in the family who teaches children how to speak, the body in the factory who welds iron, the body at war who receives bullet holes; the body is alive, and at any moment, for any misdemeanour, the lord or the law can kill it. The body in capitalism is always a laboring body, always awaiting work: we ask why that mother doesn’t have a job, why that homeless man isn’t working, we ask children what job they want and lament the misery of our jobless friends, hoping only that one day they will enter an office and reproduce some capital; the body is at work, and if it resists work, at any moment the economy can force it to stay painfully and agonisingly alive until it makes some fucking money! This is the totalizing development of the body as a machine of money-production in capitalism, in which each one of us is a camera for capturing space, pushing those architectural movements of Capital a little further on.

look, i’m not going to manufacture any more sadness. it happened. it’s happening.

America might kill me before i get the chance. my blood is in cahoots with the law. but today i’m alive, which is to say

i survived yesterday, spent it ducking bullets, some flying toward me & some trying to rip their way out

// Danez Smith / every day is a funeral & a miracle //

//

> The white body can never quite die, though, because whiteness is ownership. The white body is coded as the proper owner of Capital. The Black body is coded as property, and it belongs to the white body. The Indigenous body is coded as a misuser of property, the body that doesn’t know how to turn the land into an industrially productive machine and property into an expansive force of racialization. In the racial architecture of capitalism, the white body is property-ownership, the racialized other body is property. And so what this way of seeing in the vortex consuming time does is maintain a spatial boundary between bodies allowed into one racial category and bodies relegated to another, and this space creates existence: the white body lives and must die; it is narrated as the pinnacle of History and its property must be inherited, passed on to the next imperial body in the patriarchal line – it must become a statue marking space in the city. The racialized other body dies and must live; it is always on the periphery of every narrative, of History, of Capital, of wars and events and statues and the school syllabus (EUROPEANS INVENTED EVERYTHING), always on the edge of existence (AFRICA NEEDS HELP), always in the past (CHINA IS BECOMING WESTERN), and yet it can never die, it must work more, it must join the factory, get a loan from a bank, invest in property, make a classic slapstick YouTube clip, date on a narrowboat with fruity IPA and be saved by the bloody claws of white saviourism.

I chose my brother over my desire To be invisible.

We thought your brother was dead… He is.

And his death made you Visible?

You only see me When I carry a man on my back.

// Jericho Brown / The Interrogation. Part ii: The Cross-Examination //

//

> Seeing is capturing. The city sees, and in the racializing city the police maintain the neat division of which body captures and which is captured, which is inside the wall, which outside, which is allowed into the private park and which is not, all the while keeping up the imperial distraction of the ceremony: nothing to see here! Some bodies are allowed protection from this capturing, and must work endlessly for that protection. To have a body becomes a war, an endless body-on-body battle for superiority, the superiority of more accumulated Capital. Some bodies are accumulated, others accumulate. There is no longer any option but these two, and both these options are endless war. To see – to have a body – is not a secret war, a war by other methods: it is war. The very language and code of being becomes the body-on-body bloody war.

Language has no body. The message is a virus. The message cannot be killed.

// Jackie Wang / THE DEATH THAT IS NOT A DEATH BUT IS THE BIRTH OF EVERYTHING POSSIBLE //

//

> Time is taken into this fight, stolen from the bodies in their endless war, and more space is made. Space pushing forwards into open land, making it a battlefield. Space-as-Capital conquers everything and then moves upwards, scanning the land with drones now that the whole world is a warzone. As the drone indiscriminately flies above the areas of extraction, every speck of life everywhere is a possibility, another battlefield for producing profit. Every space is coded as beforethe present of American Capital, and every space needs to be violently hauled into now. Everywhere that was unspeakable in the grammar of Capital is retroactively certified as nothing but primordial barbarity always awaiting benediction by Capital, a zone marked for extraction, for abstraction, into the language of spatial domination and the force of being defined as a racialized body with no purpose but reproduction.

I was one burnt daughter in a genealogy. Stepped into the oil spill like a siren emerged dyed black backed with the wings of a tanker’s logo jangling stranded in the outer ocean

// Rachael Allen / Apostles Burning //

//

> This force is whiteness, and it is everywhere because it is unspeakable. Language cannot speak itself. Like the Law that opens everything but itself to condemnation, the centre cannot be self-seen, cannot be captured by the capturing mechanism of the photographic eye that functions only dialectically – the holder of the camera, of the eye, looking at the object and creating subjectivity through the object-status of the other. There is necessarily always an exemption to the rule, and the expansion of white supremacist Capital is exempted from its own language. It is a violence that constantly labels everything, but which disappears when turned to. A violence that abstracts itself as immovable/unspeakable myth above the rest, God to the Apostles, approachable only through the mediation of the myth itself.

Where are you I am not there for You. I’m morning in the milkiest decade

of all, a piece of white snow in a snow dome. Make happy, make ache vanish or dispel well

out on the winter’s wish well well well well

// Amy De’Ath / Holey //

//

> The Law can only focus on repairing a wound without realizing that the Wound precedes and creates the Law. Without the Wound there is no need for the Law. The Law is a force of imbalanced power that functions to maintain the divisions and differentiations of the Wound. People for millennia have traded in the inequality of bodies, but it was not until Caucasian capitalism that the racialized divisions were retroactively inscribed as the entire ontology (way of being) and epistemology (way of knowing) of life. Every defender of capitalism loves to eternalize power imbalances: Greeks had slaves; feudal farmers were fucking miserable. Obviously. But only in Caucasian capitalism has the racial code become a reproductive dogma, inscribing racial power imbalances in the ideology of time and constructing nothing but the liberal futility of the Law to enforce change, so that regardless of what anyone does, regardless of which laws are passed or who is voted into seats of power, the racial code will survive because to undermine it, the entirety of being, knowing, space and time have to be destroyed. Only in Caucasian capitalism is an ideology of “nature” a homogeneous hegemony. Time, space, being, nature, life: all are bound to Capital. No other system has ever been so self-obsessed. That is the problem with City Everywhere.

If Black Lives Matter, then that means the destruction of America. The entirety. That vibrates deep down into the core of the earth, to emerge and destroy Europe and the imaginings of it.

I’m the angel knocking on yr door To let disease in The place that I fit in doesn’t exist, Until I destroy it.

// Jasmine Gibson / Hollow Delta //

//

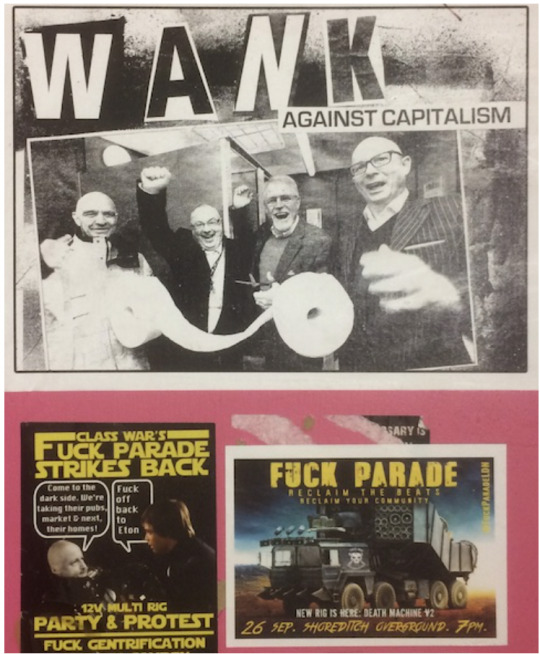

> The greatest show imaginable of the whiteness of the Wound in the terrifying horror City Everywhere is the ejaculating white male. The man staring at his laptop screen, pixels tied around the form of feminized bodies, jizz-spilt, spunky teens, the man in his endless war strumming, rubbing time into this spatial production. Rub, rub, rub, make space, man. Spill it over the time you have used, man. The first act of masturbation is Onan in Genesis, who spills his seed on the ground to protect his property. Wanking, like Capital, captures space. But does wanking steal time? Or is wanking its own kind of temporality? It is circular, endless, it goes on and on and never changes and rewrites all time as itself (while wanking, all you want to do is wank forever…) – just like Capital and the shiny shitshow of the white supremacist city. But in ejaculation there is no promise of a Future. Capital must promise a greater Future, the time when value is accumulated entirely in the Tech Execs and the Supreme White Bodies of the Law and the Economy. Wanking is the cancellation of the Future. It is labor that produces no value except the value of itself as a valueless act. It is the spillingof the Future, the cut in flows of Capital. Wanking is the brief moment of calm in the endless war of body-on-body. The body is still producing spatial codes as it spunks up its Future. Ejaculation is the waste of white supremacist Capital.

// Fuck Parade / Wank Against Capitalism //

//

> And poetry is so spatial, it’s such a rubbing force, collapsing the solidity of structure and yet being so structural, bound so strictly to the past and its ordered forms. The words rise up, the imperial power of language limiting thought to its own centrifuge, restricting knowledge to its own mythology. Poetry clearly shows the impossibility of Wittgenstein’s famous “Whereof one cannot speak”. One is always already speaking, regardless of what one says, whether or not sound is made. In the language of late liberal Capital, everything is said by the code of value accumulation and racializing modern sciences. Poetry is the spatial performance of language, cutting up pages and fetishizing the blank spaces not yet marked in the ink of languages. It is, as it has been thought since Ancient Greece, a mimesis of the city. It is the towering code of privileged space, placing monumental statues as celebrations of imperial domination and the pride of extracting materials to produce more space which creates the architectural/poetic language of words and buildings versus not-yet-conquered land, which is codified in Capital as white bodies versus bodies of colour. Everything about poetry is a battleground of racialized bodies. I keep speaking to people about this and they keep waving me away. But poetry swirls the myth of poetic time into more poeticized space, turning everything into it while it removes itself. Poetry is the city, and the city is whiteness. For how long can we just pretend that raciality and its violent colonial ideologies that construct divided bodies are not inherent in poetry? We’re walking through the city all the time, picking up new spatial codes that break the seamless ease of futurity, spunking out predictable Futures, and so we are complicit in the divisions and the violence.

We drill through to our body’s core with quack psychoanalysis, drawing ancient oils to conflagration. And it all starts with a tug on the sleeve: desire to be known.

But what we discover in the cistern of our history is pure horror.

// Oliver Jones / tug on the sleeve //

//

> I wish I had some kind of solution. All I can think of is writing poetry about whiteness, confront baldly the violence of the city we exist in. To ignore it is to accept the racializing code of the Law. To say it’s not a problem is to presume the spatial divisions of this city are somehow natural or unchangeable. Poets who exist in the category of corporeal privilege called Whiteness (which is the City and the Law) have to undermine the solidity of their bodies by writing it away with new codes of space, spatializing the bodily city in new ways that snap the normative movements of the violent force. Since the white body’s power comes precisely from its self-removal from City Everywhere and its racializing dynamics, it is poets with white bodies that must join the chorus of antiracist poetry by poets with racialized bodies to break the horrible solidity of City Everywhere and its divisive architecture. When poets existing in the privileged category of whiteness recognize that the constitution of their body is precisely the power of the city, when white poets call forth the violence of their oversight that captures while paving over complex temporalities with more white ground, then and only then will a poetry of radically subversive equality be existent. Then there will be a poetry that is not all one, that is not held together by misunderstood pursuits of homogeneous unity and uniformity, but rather a poetry formed of infinite differences in which the meaning of each difference changes every time it is spoken. Poetry distorts the path from sign to signifier, from the thing to what the thing is meant by. When poetry consumes City Everywhere, eating up its tracks and blinding the power of its sight, then black will not mean what black means, indigenous will not refer to that, white will not mean what we all know it does now. There will be difference untied from its singular orbit, unscratched from the hackneyed tracks.

[insert poem]

// you //

// Notes // Citations in the order they appear in the text:

James Nixon, ‘Ars Poetica #5’, from Rimbaud’s Lost Manuscript, unpublished Ph.D. thesis, Goldsmiths (2018).

A. K. Blakemore, ‘nymphs’, in Fondue (London: Offord Road Books, 2018), p. 23.

Danez Smith, ‘every day is a funeral & a miracle’, in Don’t Call Us Dead (London: Chatto & Windus, 2018), p. 66.

Jericho Brown, ‘The Interrogation’, in The New Testament (London: Picador, 2018), p. 12.

Jackie Wang, ‘THE DEATH THAT IS NOT A DEATH BUT IS THE BIRTH OF EVERYTHING POSSIBLE’, in Carceral Capitalism (South Pasadena, CA: Semiotext(e), 2018), p. 313.

Rachael Allen, ‘Apostles Burning’, in Kingdomland (London: Faber & Faber, 2019), p. 70.

Amy De’Ath, ‘Holey’, in Lower Parallel (Brighton: Barque Press, 2014), p. 21.

Jasmine Gibson, ‘Hollow Delta’, in Don’t Let Them See Me Like This (New York: Nightboat Books, 2018), p. 80.

Fuck Parade, ‘Wank Against Capitalism’, photograph taken by E. C. Mason at LARC (London Action Resource Centre, Whitechapel), November 2018.