#Tokaido Road prints

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Tokaido Road Trip. Part 3.

The end is in sight The Tokaido Road Hiroshige’s journey is over two-thirds complete. In the last blog he and his party had arrived at Arai and now the Tokaido Road travellers head in a westerly direction, following the coast as it approaches Shiomizaka, No.37. Akasaka: Inn with Serving Maids by Hiroshige Along with the preceding post stations of Yoshida and Goyu, the one at Akasaka was well…

View On WordPress

#Art#Art Blog#Art History#Hiroshige#Japanese art#Tokaido Road prints#Ukiyo-e prints#Utagawa Hiroshige#Woodblock prints

1 note

·

View note

Text

Pages from Tokyo Manga-kai (1921), a collection of manga sketches of the Tokyo Tokaido.

Artists include: Okamoto Ippei (1886-1948), Shimizu Taigaku (1884-1970), Maekawa Senpan (1888-1960), Shimokawa Hekoten (1892-1973), Mizushima Niou (1884-1958), and many more.

115 notes

·

View notes

Photo

HIROSHIGE’S JAPAN

Journey across the old Tokaido Road connecting Tokyo to Kyoto in Edo Period through the eyes of the French artist Philippe Delord as he explores the 53 post towns along the scenic route. Utagawa Hiroshige is famous for his artwork depicting the route in 1832. 200 years later, Philippe Delord set out on his own journey as he re-discover this mythical road on his scooter. He documented his findings in this illustrative journal where he share historical paintings, personal sketches and commentaries as he attempts to retrace all the exact spots. It’s like watching a travel road trip vlog as he describes the uniqueness of each town along the route, such as the food, festivals, scenery, people, culture, architecture and more. As someone who loves hiking in nature, this is a very pleasant read. I love browsing through it after a long day of work while listening to meditative music and imagine myself walking there. Hope to go hiking in Japan one day and explore the post towns seaside route such as this or the mountainside route like the famous Nakasendo Trail wandering around like a Ronin.

#hiroshige's japan#wood block print#tokaido road#utagawa hiroshige#the fifty three stations of the tokaido#phillippe delord#art book#travel journal#japan#kyoto#tokyo#edo period#ronin#book therapy#book review#book recommendations#japanese book#japanese art#tuttle publishing#hiking in japan#nakasendo trail

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

From a triptych known as “Cats for the 53 Stations of the Tōkaidō” by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (ca. 1847) — a spoof of the popular Japanese prints subject depicting the Edo to Kyoto coastal road. ⠀ Available as a print from our online shop — https://publicdomainreview.org/product/cats-for-the-stations-of-the-tokaido-road #caturday

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kuniyoshi Utagawa, Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido Road: The Cat-Witch of Okabe, 1835, woodblock print (Art Museum, Worceste

The dancing cat familiars of the witch make me giggle happily.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Images of Ghosts Have Endured in Japan for Centuries

A New Exhibition at the National Museum of Asian Art displays Haunting, Colorful Woodblock Prints

— Roger Catlin | April 26, 2024

The Ghost of a Fisherman, Tsukioka Kogyo, woodblock print, 1899 National Museum of Asian Art

Oiwa’s husband wanted to remarry his rich neighbor, but his wife was still very much alive. He first tried poisoning Oiwa, but it disfigured her horribly rather than killing her. Then, he threw her into a river to drown, which was indeed successful. But later, when he returned to that river, Oiwa’s ghost rose from the water to haunt him no matter where he fled.

Foreboding depictions of this Japanese ghost story and others like it populate the “Staging the Supernatural: Ghosts and the Theater in Japanese Prints” exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art.

Going back centuries, ghost stories carry great resonance in Japan. The over 50 works on display, created from the 1700s to the 1900s by Japanese artists, show the lingering power of woodblock print art and the stories that the art represents, which continue to flourish in Japan today. Coming out of the theater traditions of kabuki and noh, the prints proved equally as popular as the performances.

The story of Oiwa, the faithful wife who returned as a ghost to haunt her murderous husband, was told in the 1825 kabuki theater production of Ghost Story of Yotsuya on the Tokaido by Tsuruya Nanboku IV. Though the supernatural had long been part of Japanese culture, the Edo period (1603-1868) and this specific production gave permanent prominence to the genre, says Kit Brooks, co-curator of the exhibition. The production toured more extensively than earlier variations and featured the potent special effects of flames and actors spurting blood and flying via wires.

Artists reproduced images from this ghost play and others of the era for clamoring patrons who wanted a souvenir of the production and its specific actors, often identified in the prints, and to recall the stories.

Left: Tsuchigumo, from Prints of One Hundred Noh Plays (Nogaku hyakuban), Tsukioka Kogyo, woodblock print, 1922-1925 National Museum of Asian Art Right: Oiwake: Oiwa and Takuetsu, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, woodblock print, 1852 Oiwake: Oiwa and Takuetsu, no. 21, from the series Sixty-Nine Stations of the Kisokaido Road, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, woodblock print, 1852 National Museum of Asian Art

Kabuki, which originated in the Edo period, was known for its stylized performances and intricate special effects that made it a popular entertainment for broad audiences.

“Whether it was tricks on the stage in terms of trap doors, lots of props, synthetic blood, contraptions that would have characters on wires, flying through the theater—these things were obviously conveying the presence of ghosts,” Brooks says.

Productions featured “spirit flames,” or fire that indicated the presence of ghosts. “Kabuki is very overtly entertaining in terms of bombast,” Brooks says.

Thousands of prints were created and made available at surprisingly populist prices. In the 1840s, Brooks notes, someone could buy a single-sheet multicolor woodblock print for the price of a noodle lunch.

Such colorful, vivid examples rarely survive after nearly two centuries, especially the prints that involved paper flaps that lift up, meant to reflect complicated stage effects.

One such elaborate woodblock print in the exhibition, made in 1861 by Utagawa Kunisada, shows the body of Oiwa pulled to the surface with a fishing hook and, by raising the flap, the body of a second corpse, a servant whose fingernails kept growing after his death.

This trick is even more effective onstage, since both corpses were portrayed by the same actor, doing a quick costume change.

By the 1860s, the stage trick had been used for nearly 40 years, and in that decade, real water tanks were used onstage. Brooks says prints were created to commemorate the trick. The prints are rare, especially those that survived fully intact.

Ghosts had also been prominent in noh theater going back centuries and aimed at a more elite, discerning audience.

Shakkyo, from the series One Hundred No Plays, Tsukioka Kogyo, woodblock print, 1922-1927 National Museum of Asian Art

Noh started in the 14th century “but dates back much earlier to harvest rituals and entertainments at shrines and temples,” says co-curator Frank Feltens. Those rituals involved dances, chants and characters using elaborate wooden masks. Donning a mask meant “you are basically assuming not just the essence of that role—you’re becoming it,” he says. “It’s a kind of spirit transmission that happens for them.”

Noh may have died out, Feltens says, had it not been revived as a cultural currency when Japan was reinventing itself in the mid-19th century as a more modern nation-state.

The 19th-century woodblock artist Tsukioka Kogyo tapped into the growing interest in noh by not only documenting its fearsome characters, but also clearly indicating the actors beneath the masks to the point of creating behind-the-scenes images of the theater for the first time.

“This peeking behind the scenes is almost sacrilegious in a way because it takes the mythology of noh away,” Feltens says.

Noh stories may not have been as bombastic in ghostly reproductions as kabuki, but the form was instead “capturing stories of the distant past, and those stories are often associated with specific sites, specific locales scattered throughout Japan,” he says.

Those stories are told through spirits associated with the sites, and the spirits are conduits for local memory, he adds.

So why have ghosts endured in Japanese cultural traditions, and why the big revival in the Edo period?

Collector Pearl Moskowitz, who, along with her husband Seymour Moskowitz, gifted hundreds of prints to the museum, posits in the exhibition catalog that it may have been a way to reflect society in a changing time. “My guess is these tales of ghostly hauntings acted as forms of justice in a feudal society in which the authority of the ruling class was absolute,” she writes in her essay.

In such an unjust class system, “it was kind of a catharsis in watching these kinds of plays where ghosts could take vengeance in ways they weren’t able to, and get justice achieved through these revenge plots in a way that might have been very satisfying,” Brooks says. “And samurai were often villains in these stories as well, so that lent some credence to that theory.”

It’s difficult to know how many prints were made at the time, Brooks says, adding that people still make them with traditional methods, and a practitioner could make 200 in a morning.

Viewers can likely connect these images of specters to modern Japanese horror in films like 1998’s Ringu, and its English-language remake, 2002’s The Ring.

“Japanese ghosts are things that people know from Japanese horror films,” Brooks says. “So even if they’re not specialists in the subject, you can still see things that you’d recognize and be interested in.”

Originally set to open around Halloween in October 2023, the exhibition was postponed for almost six months following the discovery of a leak in a nearby stairwell.

“Even though nothing was in danger, you obviously have to have an overabundance of caution, so we took everything out,” says Brooks. “It meant the second installation went very, very fast.”

“Staging the Supernatural” will run until early October at the National Museum of Asian Art—closer to the Halloween connection it was denied last fall.

But people are encouraged to also contemplate the supernatural in the summer. “In Japan, summer is the ghost time period,” Brooks says. “People tell ghost stories in the summer because it’s hot and sweaty and humid, and they make you shiver, which makes you cold.”

— Roger Catlin | Washington, D.C. freelancer Roger Catlin has written about the arts for AARP The Magazine, The Washington Post and other outlets. He writes mostly about TV on his blog rogercatlin.com.

#Japan 🇯🇵#Images of Ghosts#Endured#Exhibition | National Museum of Asian Art#Haunting | Colorful Woodblock | Prints#Smithsonian | Magazine

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sakanoshita: Fudesute Mountain, by Utagawa Hiroshige, ca. 1833-1834

All printings of Fifty-three Stations of the Tôkaidô Road: https://www.masterpiece-of-japanese-culture.com/paintings/ukiyoe-wood-block-printing/utagawa-hiroshige/fifty-three-stages-on-the-tokaido-by-hiroshige

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kanshaku Tamanage Kantarou no Toukaidou Gojuusan Tsugi July 3, 1986 // Family Computer

The tokaido, or "eastern sea road," was the superhighway of Edo period Japan, linking modern-day Tokyo in the East to the old capital of Kyoto in the West. There was quite a bit of romanticism around the idea of traveling the tokaido, and this was immortalized by ukiyo-e master Hiroshige in his series of prints depicting each of the fifty-three government checkpoints along the road.

Many, many years later, someone decided to make a video game doing the same thing. You play as a fireworks artisan who has to make his way up to Edo, pursued all the way by various types of bastard (bird bastard, gun bastard, jumping bastard, etc) and only able to defend himself with what amounts to hand grenades. Unfortunately the game doesn't have 53 levels, but it does put a lot of effort into the geographical accuracy of its levels, with tons of historically-accurate landmarks appearing along the road just as they should. Graphically, the game is very enjoyable and is possibly the first game that lets you immerse into a historical location.

As such, I really wanted to complete this game, but it was pain. The player character controls like he's constantly on ice, and the one attack you have comes out at a weird angle so it can be hard to throw it in such a way that it actually hits the enemies. And the enemies for their part will often pursue you relentlessly, meaning almost certain death if you happen to miss your first shot at them. I watched a superplay on YouTube and with practice, you can really zoom through these levels, but I got other games to get to.

0 notes

Text

“Connecting the city of Edo (now known as Tokyo) to Kyoto, the Tokaido road was the most important of the "Five Routes" in Edo-period Japan. This coastal road and its 53 stations has been the subject of both art and literature, perhaps most famously depicted by the Japanese artist Utagawa Hiroshige in his The Fifty-three Stations of the Tökaido, a series of ukiyo-e woodcut prints created in the 1830s. An unusual take on the theme comes in the form of these potted landscapes from 1847, each depicting a station on the Tokaido road. A year after they were made the artist had a relatively obscure ukiyo-e artist named Utagawa Yoshishige to illustrate each piece and make them into a book.” Publicdomainrev on Instagram

0 notes

Text

The Artistic Tapestry of Ukiyo-e: Exploring Japanese Woodblock Prints

Japanese woodblock prints, also known as ukiyo-e, have captivated art enthusiasts for centuries. Originating in the 17th century, these prints reflect the unique artistic traditions of Japan and provide a window into its rich cultural heritage. This article explores the history, techniques, themes, and enduring appeal of Japanese woodblock prints, highlighting their significant contributions to the world of art.

Historical Context: Japanese woodblock prints emerged during the Edo period (1603-1868), a time of relative peace and stability in Japan. Initially used as book illustrations and playing cards, woodblock printing eventually evolved into a popular art form accessible to a wide range of social classes. The prints depicted a variety of subjects, including landscapes, historical events, theater actors, beautiful women, and scenes from everyday life.

Techniques and Process: Creating a woodblock print involved a collaborative process among the artist, carver, and printer. The artist would first design the composition, which was then transferred onto a woodblock. Skilled carvers would meticulously carve the image into the block, leaving raised areas that would receive ink. The printer would apply ink to the block and press it onto paper, resulting in a unique print. Multiple blocks were often used to achieve various colors and layers of detail.

Themes and Subjects: Japanese woodblock prints encompassed a wide range of themes and subjects. Landscapes, known as "fukeiga," depicted beautiful vistas, mountains, and famous landmarks, often incorporating elements of seasonality and poetic symbolism. Portraits of kabuki actors, sumo wrestlers, and historical figures were popular, showcasing the fascination with celebrity culture and traditional arts. Prints featuring "bijin-ga," or beautiful women, portrayed the idealized feminine beauty of the time, emphasizing grace, elegance, and fashion trends.

Masters of the Genre: Several artists achieved mastery in the art of woodblock prints, leaving an indelible mark on the medium. Katsushika Hokusai, renowned for his series "Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji," including the iconic "The Great Wave off Kanagawa," showcased his innovative compositions and dynamic use of color. Utagawa Hiroshige's "The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido Road" series captured the essence of travel and the changing seasons. Kitagawa Utamaro excelled in portraying the grace and allure of women in his series such as "Ten Beauties of the Pleasure Quarters."

Influence and Legacy: Japanese woodblock prints had a profound impact on Western art, especially during the late 19th-century Japonism movement. Artists like Vincent van Gogh and Claude Monet were inspired by the prints' flatness, bold compositions, and expressive use of color. The influence of ukiyo-e can also be seen in Art Nouveau and Impressionism. Today, Japanese woodblock prints continue to be admired for their intricate craftsmanship, harmonious compositions, and evocative storytelling, preserving a cultural legacy that continues to inspire artists and collectors around the world.

Japanese woodblock prints, with their delicate beauty and exquisite craftsmanship, offer a captivating glimpse into the artistic traditions of Japan. From their humble origins to their lasting influence on Western art, ukiyo-e prints have left an indelible mark on the art world. Through their skilled execution and depiction of various themes, these prints continue to be celebrated as a testament to the mastery of Japanese artists and a visual gateway to the rich cultural heritage of Japan.

#UkiyoE#JapanesePrints#WoodblockArt#TraditionalJapaneseArt#Printmaking#AsianArt#EdoPeriod#JapaneseCulture#ColorfulPrints#JapaneseArtistry

1 note

·

View note

Photo

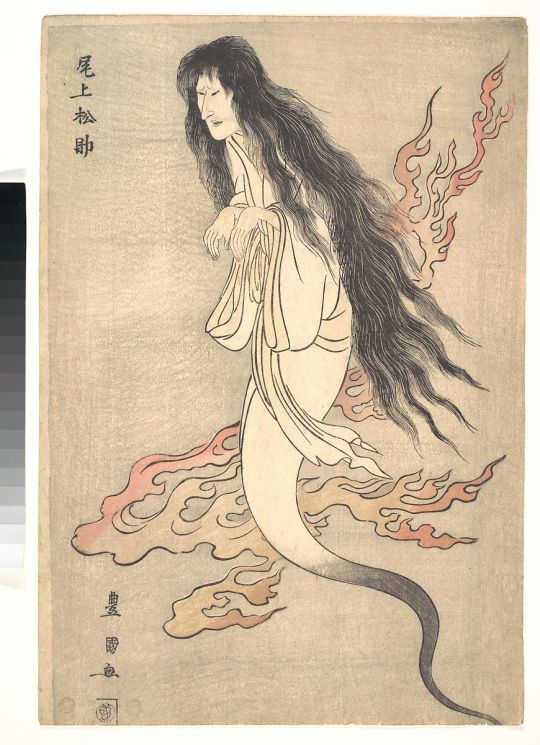

Ghost of the Murdered Wife Oiwa, in "A Tale of Horror from the Yotsuya Station on the Tokaido Road", 1812 Utagawa Toyokuni I woodblock print Metropolitan Museum of Art

#ghost#japanese horror#japanese art#japanese 1800s art#1800s art#horror illustration#yurei#japanese folktale#japanese folklore#metropolitan museum of art

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Tokaido Road Trip. Part 2.

The middle part of the journey. The Tokaido Road Post Stations: Edo (1) to Kyoto (55) The Takaido Road journey was about 500 kilometres long and most travellers made the tiring journey on foot, aiming to accomplish several stages per day although in some cases the travellers would spend several nights at one station. The whole trip, on average, would take two weeks but the more athletic could…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

Two differently coloured prints of the same woodblock template ‘Gotenyama at Shinagawa on the Tokaido Highway’, by Katsushika Hokusai, 1832.

#ukiyo-e#woodblock print#katsushika hokusai#hokusai#sakura#cherry blossoms#fuji#gotenyama#tokaido road#edo

613 notes

·

View notes

Text

For those who read widely and take an interest in Asia — likely readers of this article — chances are they will have picked up a book put out by Tuttle Publishing at one time or another.

History of Tuttle Publishing

While the Tuttle family business can be traced back to 1832, making it one of the oldest American publishers still in operation, according to the company, the Japan presence was established in 1948 when Charles Tuttle, noticed a gap in the market.

Initially arriving in Japan to work in the newspaper industry as part of the American Occupation, Tuttle later began importing American books for U.S. troops stationed in the country, and ferrying Japanese books back to the United States for interested readers.

He later opened what was reportedly Tokyo's first English-language bookstore, before publishing thousands of Asia-focused books himself. Before his death, Tuttle was awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure by Emperor Showa for his work.

Tuttle Publishing and Japan

Tuttle’s longtime presence in the market means it has an extensive back catalog that is now in high demand, fueled by the current boom in interest in Japanese culture. As interest in Japanese authors has grown, so has demand for Tuttle's early print editions.

“Because they’re hard to get hold of ... they can go for silly prices sometimes, because people collect them or tourists want Japanese literature,” he said. Tourists in particular go straight for them, as they’re hungry for Japanese stories to take home as souvenirs.

Prints vs Digital and AI

Despite people long decrying the death of print or the end of books, the publishing industry is growing stronger. During the pandemic in 2020, Tuttle saw a surge in book sales, and while this has subsided somewhat, “book sales are now higher than before the pandemic.”

Personally, although reading digitally on tablets is much more convenient and save space on bookshelf, the feeling of holding something physical, the smell of books and the sense of detachment from the world in going offline is something that readers love.

Below are 10 books that I have read from Tuttle Publishing that I would recommend those who are interested in Japanese culture.

A Brief History of Japan

The perfect book to understand Japan's history as it sums up everything concisely, not too brief and not too detailed.

A History of Japan in Manga

If you're not into reading books full of texts and more of a visual reader, then this one is for you as it's explained with manga.

The Heikei Story

The defining moment in history where the warrior class Samurai began to rise to its prominence to overthrow the Imperials.

Hiroshige's Japan

Join a French artist as he explores the old Tokaido Road that once connected Edo (Tokyo) and Kyoto as he shares his illustrations.

Japan Journeys

A collection of woodblock printing art which journals the travelers experience in Edo Period moving from one prefecture to the other.

My Travels in Japan

A cute travel diary which accounts her travel experience in modern Japan which consists of illustrations of places she visited.

Japan in 100 Words

Everything you need to know about Japan, from its culture, tradition, philosophy, food and pop culture, categorised into 100 sections.

Samurai Castles

History and design of the architecture of the iconic castles, which shows the uniqueness of each castle with photos and drawings.

Manga Yokai Stories

The short stories of Yokai and how they came to be, which are meant to demonstrate the humanity and tragedy of life.

Lady Murasaki's Tale of Genji

A story written by a Heian woman who envisions her version of an ideal man and depicts the life in the Imperial court of her time.

#tuttle publishing#japanese books#japan#book recommendations#japanese culture#japanese history#japan times#manga#japan travel#japanese art

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

From a triptych known as “Cats for the 53 Stations of the Tōkaidō” by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (ca. 1847) — a spoof of the popular Japanese prints subject depicting the coastal road that ran from Edo to Kyoto. ⠀ Available as a print from our online shop — https://publicdomainreview.org/product/cats-for-the-stations-of-the-tokaido-road

187 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kamiya Dojo Monogatari Tales 30 (JUMP SQ)

About Kamiya Dojo Monogatari:

Tales of Kamiya dojo is written by Kaoru Kurosaki and published along with the “Rurouni Kenshin Hokkaido” arc in JUMPSQ. The tale involves the Rurouni Kenshin character in daily life that takes time between Kenshin and Kaoru marriage until the epilogue chapter in the original manga before the Hokkaido Arc. Until this month (May 2022) there are a total 54 chapters in Tales of Kamiya dojo. This is an unofficial translation.

Previous Story: https://kenkaodoll.tumblr.com/post/683227437222494209/kamiya-dojo-monogatari-tales-29-jump-sq

Fujita Denzaburo and his men were escorted to Nanshuji Temple in Sakai, but their interrogation proved difficult.

Although they captured him, he stubbornly refused to talk. Investigations were also conducted at the Sanjushi National Bank and the first branch of the National Bank, but without success.

“We have solid evidence. If we show it to them, they won't be able to get away with it.”

Hearing these words of Inspector Sato, several of his followers began to speak in hushed tones.

“Of course, sir.”

“If they know that you have the evidence, even the most obstinate will give up and admit their guilt.”

“We will convict him by confronting him with the evidence.”

“Yes, that’s right.”

“There is no need to wait for the confession of an infidel who challenges the government.”

Among his cronies, the police inspector who had given the reward money directly to Chou and Kamatari spoke in high spirits.

“Let's go to the Fujita Group warehouse and seize the evidence.”

“I'd like to see them with my own eyes, the imported printing press and all.”

Inspector Sato's nose rose even higher at the mention of the foreign made printing press.

“Come in, I'll show you around. I found it by accident.”

Chou and Kamatari were the ones who showed him around, but he boasted as if he had found the printing press all by himself.

And when the group arrived at the warehouse of the Fujita group, the huge printing press had already been removed from the warehouse.

Of course it was the work of Misao and the rest of the Oniwabanshu.

“Choooooooooou!”

The inspector walks right and left in the empty warehouse.

“Kamatariiiiiiiiiiiiiii!”

He shouted, but there was no one to answer.

Both Chou and Kamatari had long since fled away.

・

“Well, that's still a lot of information.”

Under the clear Osaka sky, Chou and Kamatari were walking along the *Tokaido Road at a brisk pace.

“I would have liked to have seen the inspector's face when he realized the warehouse was empty.”

“If you were there, they would blame it on you.”

“I know, right? He wanted to take credit for finding the printing press, so he didn't seem to notice that we had excused ourselves before him. They should have at least kept an eye on us to make sure we didn't hide any evidence, but they didn't do that either. And since they paid us compensation first, we don't owe them any advice either.”

“He's so dim-witted, that inspector.”

“I feel better now that I've repaid that little girl.”

"All's well that ends well. Congrats”

“So what are you going to do now?”

“I don't know. I don't have anything in mind. I'm thinking of going to Kuwana.”

“Why Kuwana?”

“That's the place of *Muramasa, the sword that avenged the Shogunate!”

“Ah, there. I'm not interested in swords, but I'll join you on the way.”

“Where are you going, then?”

I don't have anything in particular to eat, but when I heard Kuwana, I wanted to eat clams. I might even go to eat Udon.

“Oh, let's go to Ise.”

“Too bad. I don't want to eat Ise udon. I want to eat Nagoya's *miso nikkomi udon.”

“Ah, that way.”

It seemed that they had decided where to go.

・

Meanwhile, Yahiko and Misao.

In the early morning of September 15, when Fujita Denzaburo was arrested, they had already taken the printing press out of the warehouse and brought it to Aoiya in Kyoto the next day.

And at the time when Chang and Kamatari were heading east on the *Tokaido Road.

Aoshi returned with Fukutaro.

Aoshi-sama! Welcome back. And you too, Fukutaro-kun."

Misao cheerfully greeted Aoshi and Fukutaro. She reported that she had managed to remove the printing press before it was seized as evidence that Fujita Denzaburo had been manufacturing counterfeit banknotess.

“Well done!”

Aoshi thanked Misao and Yahiko.

“Denzaburo Fujita has been arrested, though.”

Yahiko was not quite sure what was going on here. Since he could not let go and say he had done well, he felt unsettled, like he had a fish bone stuck in the throat.

“After the restoration, Japan became a judicial nation with a western policy. We must leave the rest to the law.”

Aoshi's goal to settle the wrongdoing of the Oniwabanshu by the Oniwabanshu.

“One can only hope that we are not in a country that would put people on trial for crimes without evidence.”

“That’s right.”

On this point there was nothing Yahiko and the rest could do.

“So, what's wrong with you, Fukutaro-kun? What happened to your outfit?”

In Yokohama, Fukutaro was dressed in fancy Western clothes and a silk hat. However, when Aoshi brought him to Kyoto, Fukutaro was dressed in a navy blue kimono and a haori. He was dressed modestly.

“I was wearing it as a kind of sign board to make my street stall stand out. Besides, since it was called a wrongdoing by the Oniwabanshu, it wouldn't be very convincing to apologize if I was dressed in a bizarre outfit.”

'Well, sure, you're right. But is an apology just finished by saying sorry?"

Yahiko asked him a question.

“That won't get it done, will it?”

Okina interrupted.

“Yes, that's right. He used his forbidden technique as a member of the Oniwabashu to commit a crime. The crime will be judged not by the judiciary but by the Oniwabanshu. Fukutaro, you...”

Aoshi was about to say something, but Okina drowned it out with a loud voice.

“Fukutaro, you are going to paint a scroll for each of the four seasons in all the private rooms of this Aoiya every year from now on. The *fusuma paintings will be renewed every three years. That is your atonement for your sins. Aoshi, is that right?”

“That's fine, I guess…”

Aoshi might have been thinking of a more serious punishment. However, he did not object, perhaps thinking that if it was for Aoiya's sake, it was all right.

“But I didn't know what I could draw. I was even thinking of quitting calligraphy and painting and starting over from scratch.”

Fukutaro scratched his head in embarrassment.

“No! A man with your talent stop painting? That would be a shame, wouldn't it?”

“Really! Don’t stop it!”

Okina and Misao loved Fukutaro’s work very much.

“So, I thought it would be better if I did not live again and was killed for my wrongdoing of Oniwabanshu.”

Fukutaro said this so lightly that it was hard to believe he was talking about his own life.

“That's not the way it's supposed to go, Fukutaro.”

It was Yahiko. As someone who had already lost his parents and was feeling sad about it, he was annoyed at Fukutaro's careless comments about being willing to be killed.

“You know. I was listening to you the other day. Fukutaro, aren’t you being carried away by the enthusiasm and madness of someone who wants to go to the West and create new paintings from beyond the sea?”

“You could say that.”

“I'm an outsider in the field of painting, but I've seen some great sword fighters with my own eyes. So let me tell you, in the way of the sword, there are those who want to fight and those who fight for something.”

The former was the sword-hunter Chou, who longed to wield a sword, and Yukishiro Enishi, who had no choice but to live a life of vengeance. The latter he was thinking of Kenshin, who wanted to save at least those in front of his eyes with his Sakabatou (reverse-blade sword), and Kaoru, who was aiming for a sword that would bring life to people.

“I think the path of painting is similar, isn't it? There are those who want to paint and those who paint for the sake of something. You are longing to be a person who wants to paint, but in fact you may be a person who paints for something. In order to find out, I think it is not a bad thing to paint for Aoiya.”

“I see. You have a point there.”

Fukutaro put his hand to his chin and nodded.

“You are a very young child, but you have a lot to say.”

“I am not a child. I am Yahiko Myojin, a Tokyo samurai.”

“Yes. I look forward to your future. When you grow up, Aoiya might be full of my work.”

Fukutaro, with a gentle smile on his face, agreed to paint a picture for the Aoiya.

Then at Kamiya Dojo.

“Oh my God! Kenshin, look at this.”

Kaoru unfolded the Tokyo Daily Newspaper and showed it to him.

“Arrest of Denzaburo Fujita, a wealthy merchant in Osaka.”

“This is...”

“Chou was after him. And Yahiko and Misao-dono are working on the case Aoshi asked them to work on.”

“He's been arrested… You're sure this guy didn't print counterfeit banknotes?”

“According to Yahiko, it would seem so.”

“Misao-chan and the others didn't make it, did they?”

Putting his hand on Kaoru's back, Kenshin said,

“There is no such thing as a life in which everything goes well.”

“I agree. It's impossible for a youngster like Misao and Yahiko to save a person who is about to be framed for a crime that could shake the country to its foundations. That's normal. I've been through so much in the last year that my senses have become numb.”

"Yes, that's right."

“When Yahiko comes home, we should give him plenty of good food to eat and show him our appreciation.”

“That's a good idea…”

Kenshin was about to say something.

“I'm home!”

A cheerful voice echoed through the Kamiya dojo.

“Yahiko!”

Kaoru turned around in surprise. Yahiko was standing there.

“I'm so sorry to hear about your troubles.”

Yahiko noticed that Kaoru was holding a newspaper with an article about Denzaburo Fujita's arrest.

“Oh, that. He was arrested five days ago. For a newspaper to write about something new, it doesn't mean it's up to date, does it?”

At that time, there was a considerable time lag between the time an incident in Osaka and the time it appeared in the Tokyo newspapers. It was difficult to send enough information for a newspaper article by telegram due to the limitation of the number of letters and other factors.

“Hopefully Fujita Denzaburo will be released for lack of evidence. If it doesn't work out, it means the Japanese law system is corrupt.”

“Which means...”

“The printing press that Fukutaro used for making counterfeit banknotes was dismantled and disposed of by Oniwabanshu, Shiro-san and Kuro-san. There is no more evidence of it.”

“You did well, I see.”

“That's great, Yahiko! We should eat something delicious to celebrate.”

After all, whether the mission failed or succeeded, they would go out to eat something delicious.

“It's been a while since I've been to Akabeko, that I have.”

“I'm sure Tsubame is feeling lonely. Let's go see her.”

“I want to know the details of what happened.”

Yahiko, who had just returned to Kamiya Dojo, had to turn around and go out again. Yahiko felt he was in a hurry, but he was relieved to see Akabeko in a relaxed atmosphere after a long absence.

Notes:

*)Tokaido Road: old seaside road to Kyoto from Tokyo

*)Muramasa, commonly known as Sengo Muramasa, was a famous swordsmith who founded the Muramasa school and lived during the Muromachi period in Kuwana, Ise Province, Japan. His swords were used by the Tokugawa clan.

*)miso nikkomi udon: udon cooked in a broth containing miso paste

*)Fusuma: Room partition

**Fujita Denzaburo's arrest is based on a real event, you can read more about him here.

.…..continue in chapter 31…… https://kenkaodoll.tumblr.com/post/683499038076715008/kamiya-dojo-monogatari-tales-31-jump-sq

TLnote(1): translating Japanese is so hard because the sentence structure is very different compared with the English also the style of writing is different, plus there’s a lot of figurative, poetic language and things that sounds not making sense if it’s directly translated into english. So forgive me if this is very weird to read, and please tell me if you want give corrections. TLnote(2) I will provide the original Japanese text for correction if any of you who read have better knowledge of Japanese language. Just dm and I’ll send the file. TLnote(3) Dtninja had translated some earlier chapters in his website. You can go and check on there.

#Kamiya Dojo Monogatari#Tales of Kamiya Dojo#rurouni kenshin#ruroken#Honjou Kamatari#Sawagejo Chou#Myoujin Yahiko#Makimachi Misao#Shinomori Aoshi#Oniwabanshu#Himura Kenshin#Kamiya Kaoru#unofficial translation#kaoru kurosaki#kurosaki kaoru#kenkao

9 notes

·

View notes