#Tiger is at the apex of Ecosystem

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Vital Link Between Wildlife and Ecosystems

Do you ever see wild animals? In the narrative, the author explores their experiences in Dudhwa and Corbett National Parks, highlighting the interdependence of forests and wildlife. The poignant observations emphasize that while humans exploit these ecosystems, animals contribute without seeking compensation. The piece advocates for respecting wildlife and maintaining a balanced coexistence for…

#Corbett National Park#dailyprompt#dailyprompt-2144#Dudhwa National Park#ecosystem#Elephant heard#Elephants#Forest#Forests and Wildlife#India#Life#Tiger#Tiger is at the apex of Ecosystem#Wild Animals#Wildlife#writing

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

Wild Cats

Jaguar, Cheetah, Lion, Tiger

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In a historic step toward the first-ever restoration of the tiger population to a nation where they were once extinct, two captive Siberian tigers have been translocated from Anna Paulowna Sanctuary, Netherlands, to the Ile-Balkhash Nature Reserve in Kazakhstan.

This remarkable event is part of an ambitious program led by the Government of Kazakhstan with support from WWF and the UN Development Program to restore the Ile-Balkhash delta ecosystem and reintroduce tigers to the country and region, where the species has been extinct for over 70 years.

“It is a high priority for Kazakhstan to work on the restoration of rare species. For ecological value it is important that our biodiversity chain is restored. And that the tiger that once lived in this area is reintroduced here,” said Daniyar Turgambayev, Vice-minister of the Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources of Kazakhstan.

In the early 21st century, genetic studies were carried out on bones and furs held in national collections which revealed that the population of tigers living between Iran, southern Russia, Central Asia, and the areas around the Caspian Sea was extremely similar to Siberian tigers.

This led scientists to conclude that Felis vigrata, the former name of the Caspian tiger, was simply the Siberian tiger that developed into a distinct population, but not a new subspecies, over generations of being separated by habitat fragmentation.

Bodhana and Kuma, the male and female tigers, will be housed in a spacious semi-natural enclosure of three hectares [7.4 acres] within the Ile-Balkhash Nature Reserve. Any of their offspring will be released into the wild and will become the first tigers to roam Kazakhstan in decades, and potentially the first-ever international tiger reintroduction.

They will play an important role in the establishment of a new tiger population in the region where they had previously been wiped out as a result of excessive hunting.

“Today marks a monumental conservation milestone to bring tigers back to Kazakhstan and Central Asia,” said Stuart Chapman Leader of WWF Tigers Alive. “This tiger translocation is a critical step to not only bring back the big cat to its historic homeland but also to rewild an entire ecosystem.”

Progress towards restoration of the area is already well underway with recovering and reintroduction of critical tiger prey species like the Kulan (Asiatic wild ass), and reforestation of over 120 acres with native trees. Being the apex predator, tigers will play a significant role in sustaining the structure and function of the ecosystem on which both humans and wildlife rely...

“With the launch of the tiger reintroduction program, we have witnessed a significant change—the revival of nature and our village of Karoi,” said Adilbaev Zhasar, the head of the local community group Auyldastar.

“This project not only restores lost ecosystems, but also fills us with pride in participating in a historic process. Because of small grants from WWF, we have the opportunity to do what we love, develop small businesses, and create jobs in the village, which brings joy and confidence in the future.”

From the very beginning, the local community around Ile-Balkhash Nature Reserve has been closely involved in the project. This includes support for improved agricultural techniques and the future development of nature tourism in the area.

The translocation of these tigers is the first of several planned in the coming years, with a goal to build a healthy population of about 50 wild tigers by 2035, starting with this pioneering pair for breeding. This initiative is not only a testament to the resilience of the species but also a powerful example of governments, conservation organizations, and local communities cooperating in wildlife and nature conservation."

-via Good News Network, November 27, 2024

#tiger#tigers#big cats#wild cats#kazakhstan#asia#central asia#biodiversity#endangered species#conservation#rewilding#wildlife conservation#ecology#nature reserve#good news#hope

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

There are more than 1000 species of sharks and rays worldwide. Sharks are apex predators in the ocean and they keep the ecosystem balanced. With decreasing populations, many ecosystems are becoming unbalanced leading to an increase in species that otherwise would have low populations and increased invasive species with no predators.

Due to overfishing and bycatch, some species are on the verge of extinction. Some threatened species include:

The great white shark (classified as vulnerable)

Whale sharks (classified as endangered by the IUCN)

The great hammerhead (classified as critically endangered)

Dusky sharks are officially endangered. They are highly sought after for finning(a practice where fishermen catch and cut the fins from shark ,throw them back into the ocean defenseless to prey ,bleeding out and unable to properly float).

Sand tiger sharks are classified as critically endangered. They have 1-2 pups every two to three’s years making it much more harder for their populations to naturally replenish.

Ganges shark-very rarely seen and it is estimated that approximately 250 of this species are alive. They are true river sharks(can inhabit freshwater) and a unique threat to them is pollution.

To give these sharks and many others a fighting chance,sustainable fishing practices should be enforced and ecosystem pollution should be reduced.

#conservation#nature#ocean#sharks#great white shark#whale shark#shark#sealife#overfishing#extinction#sharksofinstagram#wild animals#sustainable solutions#sustainablelifestyle#sustainability#oceanlife#pollution#wildlife#naturism#marine science#marine biology

194 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finale (The Gap Years part 32)

July 24th 2019

Las Vegas, NV

The end of the season, or book, or whatever this is. 4.5 k words. Marin's new allies go rescue Sierra. They still have a lot to resolve afterward.

thank you @lokiwaffles and @reggie246 for tagging along for the ride.

...............................

They answer his call. For eighty-six years now, Marin has been given every reason to think otherwise. Before he was their last chance, his allies weren’t even kind enough to whisper. If his green eyes (not true Sondaica emerald, just hazel) were any indication, then he had his mother’s bleeding heart and love for the human realm. Perhaps his father’s complexion and frame were more telling, and the prince was a push-over intended only to tie Zerada Adust into the family tree. Sure, he’s quick on his feet and good with a staff, but not like Rhiannon. He’s well-trained with his magic, but Elyan could give weight to the void itself. So every time he makes a phone call summoning a cousin or aunt or ally to Las Vegas, he does it expecting to hear that they’ve all actually run off behind his older cousin Lir and wouldn’t come back so close to the capital if Lazarus himself demanded it. Instead, he gathers an army.

Rhiannon kicks her feet up on his coffee table and twirls a pen between her fingers. She’s always been prone to nervous habits. Her father is in the next room over, scowling at the sound of a human party stories below them. The rest of Rhiannon’s close family, a mother and two brothers, are missing. Her little sister is confirmed dead. So is Elyan, a grandson of the apex who reigned before his mother. Lir shares the same grandfather, but different parents, and she holds the toy tiger that Marin earned at a carnival a month before up to the light as if it’s something more than cheap fabric. Her husband is dead as well, and they have no information about her young son.

The pattern continues through the elves of gens Adust, Celeron, Marolak, and the rest of the Lazarin faction. No one looks younger than fifteen or so in human years, as they were held at a different prison, and equally few are older than middle-age. Anyone who fought in the last coup would have been executed as a matter of revenge. Between those extremes, the family tree has been haphazardly pruned. There’s no pattern to who adds their magic to the illusions keeping them all hidden and who’s been given back to the ecosystem according to each family’s traditions. Nature never picks favorites. Luckily, their mysterious contact has cut through the fog of war. They know Sierra is being held in observation room three, down the hallway where the smaller offices used to be. The guards rotate their shifts every two hours, the human test subjects are fed at six and fourteen each day, and bodies are brought in or out every three days at sunset. For two dozen of the most powerful elves in the worlds, it doesn’t even feel right to call it a heist. The only real plans they need to make are about who dies once they’re inside.

Marin insists that they follow the new Apex’s lead and keep casualties low. The statement feels hollow with so many missing faces around him.

………………………

It’s not getting easier, Clay thinks, as he points his rifle down a hallway at a surrendering guard. Clay and Brian insisted on being part of the team to free Sierra, but they’re hardly more than mascots beside the nobility. He’s used to feeling like an outsider, but there’s something in the reflective eyes of the elves that catches him off guard every time. Zerada’s brother is one hundred and six, not twenty. Marin’s cousins all clearly remember the civil rights movement and the moon landing. Even Marin has gained new life now that he walks beside his real friends. Clay knows how to walk quietly, but these elves stalk through the halls.

He’s in a squad of four. Kova Marolak, niece of the traitorous Devana Marolak who their emissary confirmed was on the new High Council, is reckless but tough. She walks directly to his left and taps an axe across the floor. Marin walks ahead with his cousin, Lir, beside him. According to Marin, she’s his most likely challenger to the throne. According to the family tree, they’re second cousins. The guards here are commoners who were trained to handle defiant humans, not the best of the nobility. They surrender quickly, and Marin has to tell Kova off to keep her from slitting any unjustified throats.

Clay doesn’t have much to do, but Marin yields the floor to him after they corner a certain doctor at the end of a long hallway. The fluorescent lights flicker overhead and he stomps towards a thin figure kneeling against a heavy sealed door. It looks like a proper Tolkien elf in the wrong genre, slender and pale with straight black hair in a properly hygienic bun. It doesn’t wear a noble vambrace with its pale green scrubs, but raises its head to look at him without any particular fear. (Eburos? Lir mutters beside him). He raises the rifle. It should be easier now that he’s put a child into its sights.

“The vaccines are stored behind you?” he snaps. The elf thinks of Sierra as a test subject, so Clay will call him an it. So what if Brian freed his cell block with the power of friendship and hugs?

“Yes, but they’re all still in development”.

“You’re plotting global conquest for like, next year. Get up and open the door”. It does. Kova holds her axe under his neck while he and Marin file into the room. Clay barks orders back at the technician. Which of these have undergone the most testing? Which have side effects? Which strain will be used for the final attack? Clay makes it gravely clear that no matter who winds up on the throne in a few years, Marin can and will avenge him if he dies of smallpox from a sabotaged drug. He grabs vials by the handful and places them into Marin’s messenger bag. Clay’s read that there’s no real danger to getting several flu shots, so their immune systems can probably handle a few of these? Once again, side effects are better than actual smallpox. Basically everything is, except for rabies.

“What did you infect Sierra with? Where’s that antidote?”

The elf looks down. “She was given a strain derived from variola minor. It has a low fatality rate. We haven’t developed an antidote".

“You have got to be kidding me”. Kova grabs the elf’s soldier with her claw-like nails and lifts the blade higher. “Is it airborne?”.

The lab tech shakes his head. “Only through close contact”.

Marin sighs. “Kova, please don’t make the casualty list any longer. And Clay, calm. We have healers now”.

Right. Humans may have eradicated smallpox, but that achievement is probably nothing beside what elves have done.

Kova lowers the axe an inch and gives Marin a disappointed look. She has a strong elvish accent and layered brown hair down to her waist. “Just say the word”.

Clay lowers his rifle in turn. “Don’t. Let’s get out of here”.

She shoves the technician to the ground a little too harshly and hefts the axe back over her shoulders. Then they stalk back out. There are dozens of prisoners in this laboratory. A few lift themselves up to the windows of their cells and look out at him as they pass, but Clay keeps his head forward, even when the shadows seem familiar. Everyone here is already contagious. They’re also presumed dead, if anyone even noticed that they went missing. His father always said the same things about the people on the streets. Clay hesitates by a second hallway. The whole world is at stake and Sierra is locked in a cell. He can’t waste time. His family’s money won’t fix this.

Clay catches someone’s eyes anyway, a woman about his age. They had said they wanted a way out, any way out. They were cursed and Betrayed and couldn’t control it, and the Mercurali’s new rulings only brought them more pain. The jailbreak had to happen. It was a simple decision. Clay knows that the fate of a human who survives a place like this can’t be anything good. He grabs the handle of a door to a cell that used to be an office and pulls. It’s locked, of course. He looks away and laughs to himself. Marin asks what he’s doing, and Clay shrugs. He was lost in his thoughts. The rifle shakes in his hands.

………………

“Sierra!”

This… this is some sort of trick. Elves are illusionists. She knows this. Brian can’t actually-

Someone bangs on the other side of the two-way mirror. She can see a faint outline of his hands. “Sierra! We’re here to break you out!”

She sits up on the cot and listens carefully. The voice is quiet, but she guesses her cell wasn’t as soundproof as she thought. The door slides open, and she sees Brian standing in the hallway wearing an elven chestplate and sneakers. The vein-like lines that usually glow are dark, and he’s holding a baseball bat. The choice of weaponry is confusing until she sees Zerada and two unfamiliar elves behind him, all armed to the teeth. Brian’s just here for show.

“Say something that the elves wouldn’t know,” she replies.

“Eighth grade, when we had that freaky English teacher who made us read the book about seagulls? Like, quantum physics, hippie philosophy, seagulls? And the seagulls all had the last name ‘Seagull’?”

He’s actually here. She’s being rescued. She jumps to her feet and cheers (the world spins a bit. She tries not to think about Kebero’s threat of symptoms). “She wasn’t that bad”

“She was awful”. Brian looks back at her fearfully and stays in the hallway. “Wait, tell me something the elves wouldn’t know”.

She sighs. “In seventh grade, I tried to convince you to skip field day so we could all go hide in the supply closet and play Minecraft, but you didn’t want to let your team down and ratted us out to the teachers”.

Brian winces. “It’s been five years. I thought we were over that”.

“They made me play dodgeball, Brian. Me. Age thirteen. Dodgeball”.

She runs to hug Brian, but Zerada grabs her by the arm. “Cute story, but we need to leave. Clay’s team is working on grabbing your things, but no promises”.

She breaks free from her grip and mutters that he had better get her stuff. “How did you even find me? I mean, thank you, obviously”. Brian still keeps his distance. Is something wrong?

“We got a phone call from an informant in the elven palace. She’s human, and told us to call her an emissary. Essie for short, I guess. All of her information has been accurate so far”.

“Seriously? I’ve wanted to talk to a human for a while. Kebero let me speak to her seneschal, a personal secretary I think, during my interrogation but I barely got to say anything”.

One of the new elves, a twenty-year-old looking man with ombré red hair and Zerada’s pale freckles gives her a lopsided smile. “You speak to humans all the time”.

“You know what I mean!”

They start jogging. The new elves introduce themselves. The red-haired boy is Jezero, Zerada’s sibling. The other looks more alien, and is Sothea Celeron. The elf explains that Genus Celeron was more liberal with genetic engineering than most as a way to explain her webbed fingers.

The prison continues to look familiar. The lights seem cleaner and bluer than human ones, just like the ceiling lights at Project Excalibur did.

“Where even am I?” she asks, not expecting her guess to be right.

“The ruins of Project Excalibur,” Brian replies too quickly. “Have you been experiencing any symptoms? Clay says that smallpox takes over a week to show symptoms, but…”

Sierra looks sheepishly at Zerada. She had the right idea to hold her back. “I’ve felt a bit off lately, but I assumed it was just from being in a cell. Kebero did threaten me a few days ago… They said, uh, ‘it might be hard to take you away from Eburos once the symptoms start’”.

The elves mutter to each other. This Eburos seems to be a hated figure. Sothea pauses the group and pulls Sierra into a side hallway. She places a hand on her forehead and her eyes begin to glow the blue-green of an anglerfish’s light.

“She has a mild fever. I can’t tell anything else yet”.

Sierra focuses on the cracks in the ceiling. She’s out. They have allies. No matter how many lies Marin has told, he isn’t going to let her die.

…………….......

She holds a dagger up in front of her eyes. Perfectly straight with no chips or cracks, but it’s always a good idea to check after any sort of engagement. Engagement. She means a battle, but it’s probably a good idea to check one’s weaponry after setting a betrothal as well. Her betrothed is not as reliable as the metal of her daggers. He whispers with his cousin in old Lazarin, and Zerada makes sure to keep her ears back and give no sign that she’s listening.

“Lir, you led your army at the Conservatory. I know you want power, but we’re going to have to be united to take back the crown”. He waits for her to reply, but Lir just leans back in her chair. She looks more like a proper Sondaica than him, with looser curls and true emerald eyes.

“Certainly. Lazarus himself was known for his allies. Did your mother ever tell you about him?”

Now this is a rumor she’s heard, but never quite believed. Zerada makes herself busy with another task.

“Did she tell me about…Lazarus? He was the first apex and the founder of our line? He has the massive statue overlooking the harbor? I could probably list every battle he led, you know how much time we’ve spent studying. Unless…”.

Lir nods. “My father ruled in your mother’s stead for a decade or so, just before you were born. It wasn’t official, but he wore the helm and wielded the scepter”.

He did, and it was scandalous. For Emer to take a vacation from the throne… she’s always been impressed that the apex retained power once she came back. However, it did have a precedent.

“Once she returned, my father all but threw the regalia back into your mother’s hands. Everything about the old apexes drifting off into the void rather than abdicating… that’s not a euphemism”. Lir pauses. The nobility do not believe in life after death.

“When Lazarus emerged from the void with the power of a god, he left a piece of himself there. It’s an entire afterlife, and the scepter and helm are anchors to it. For those ten years my father was consulting with His Ascendance himself, and our ancestors did not approve of him”.

The void is pure magic and thought outside of time and space. With enough willpower, anything is possible. It’s still a shock. Life and death are the only sacred things the nobility have. If anyone was going to break those rules, yes, it would have been Lazarus Sondaica . He was a troublemaker, a psychopath, and completely unbound by any rules. The only person he ever truly cared for was a human soldier, and when he died of a bioweapon, Lazarus was never the same. Human stories tell of him abandoning his kingdom to search for eternal life. Elven history explains that he threw himself into the void after that, then not only survived but emerged to conquer the world. The idea that he succeeded in finding immortality… is nowhere near as unbelievable as it sounds. Jealousy hits her like Marin’s quarterstaff, which she knows has precisely the same weight as the scepter. He’ll see his mother again.

Marin is asking why he’s hearing this information. They’ve managed to manipulate the humans, but that seems to be the limit of his charisma.

“My father said it was awful if they didn’t want you there. It’s the highest council there’s ever been”.

They both pause.

“So who’s the heir then? I mean, some previous Lords have kept the regalia in exile, but I sure don’t have it on me”.

“Like you said, we’re going to have to be united to take back the throne. Your mother proved herself during the last coup. We’ll do the same. Survival of the fittest”.

Zerada’s bet is on Lir. Her betrothed is capable, but the truly impressive acts and plans have come from the humans. Before the void-blank judgment of Lazarus, there’s no way he’ll come out on top. The thing is, she’s never found gambling to be much fun on its own. It’s really about the players and what they lose. Too bad she’ll only get a seat beside Marin.

…………...........

“Crazy to think that I’m the champion wrestler, but you’re the one who’s good at hurting people”. Brian says it as a joke, but Clay freezes for a second while putting bandaids on his arm. They’re red, white, and blue, which he might deserve after all the politics he’s talked about these past few weeks.

“You cracked someone’s ribcage like a pumpkin. These are not equal acts".

Sierra has a mask (from their stash of makeshift radiation gear) on and her arms crossed. They never did get her favorite sweatshirt back from the elves. She has three dinosaur bandaids on her left shoulder, which has apparently gotten all of its movement back. “Seriously, where did you learn this?”

Clay only shrugs. He’s wearing a leather jacket and those reinforced jeans despite the heat. It’s been a pattern since the jailbreak. “How’d you learn to build a car?”

So he learned through some combination of sneaking into classes, his parents, bribing grad students, and the internet. Fair enough.

Somehow, they are all back in Las Vegas in one piece. No one has any injuries more severe than bruises and they’ve added dozens of nobles to their growing army. Their emissary seems confident that the Mercurali, and the rest of the Eight Points faction, still won’t make any overt moves against them in such a populated area. If they move a bit and stay sharp, they can stay here until the elven world reveals itself. Of course, that reveal will be an apocalyptic one. Brian has always loved that bit of etymology, but it’s less fun with actual doom on the horizon.

Sierra relayed her full interrogation to the two of them, including the brainwashed gaps. They’re staring down the barrel of a fifty percent casualty rate. Brian had taken a moment to clarify that it seemed like those deaths weren’t just from plague. The wording included anyone alive now who would die due to the elves, which meant deaths from plague, but also war, starvation, normal disease, or elven abuse. He’d felt a bit detached while he said it, like he wasn’t sitting on the tile floor of a Vegas suite, but actually drifting a few feet behind. He then clarified that this was not better. Either way, the plague is clearly meant to bring humanity to its knees. That means a high death toll, and as soon as it starts they lose their safe zone.

So, in reality, they can’t stay here at all. The three of them may be immune to the plague (or will be soon) but no one else is. They have a year, maybe even less, before humanity screws up a pandemic response so badly that they’ll never be able to convince anyone that human independence is a decent plan.

And he’s still drifting. Brian can catch a baseball moving at nearly a hundred miles per hour but his hands move like claws as he picks up a full vial.

“What if I drink this?” Every year, they announce the team roster with a sheet of paper by the lunch room. Last name, weight class, class year. Team members hear directly from the coach, but it’s always his time learning his new brothers in arms. Brian sees the gym empty and the mats rolled up against the walls. He sees smallpox scars and draft notices and crushed bones from concussion rifles. He looks out at San Fransisco from a stage before Ishtar Mercuralis puts him down like an old dog. He hopes Zerada would bail him out before it got that far.

“It would taste like salt water and do nothing,” Clay replies. Sierra mutters that he should totally try it.

“We should probably go home for a bit. Do something productive as an alibi,” she continues.

“That would put us within a literal stone’s throw of the elven palace. We can’t risk it,” Clay replies, then he blinks as if realizing something. “And there’s no way we can convince your family to get injected with a mysterious elf drug. This thing could genuinely kill us”. He doesn’t seem convinced by his own argument.

Brian is more offended by the idea. “Remember the ambush? Without elves, we’re completely vulnerable. They can find us anywhere”.

Six weeks ago they’d walked with Marin. The fog grew thicker and suddenly they had blood on their hands and a quest to complete. They need to stay together.

“We could hide Marin in that spare room Clay always used?“ she suggests. Brian laughs it off, but Clay seems to consider it.

“I’ll ask. I’m sure some noble would be willing to watch us for a week or two,”

“So what, we’re calling a timeout on our mission to save the world?” Brian replies.

Sierra leans back. “I thought I was going to die in elf prison until like twelve hours ago. We deserve a break”.

“And we all might be smallpox carriers now. We should quarantine here for a week at least. Might as well go home after. I want to give my friends some sort of warning, too. They can keep secrets”.

That gets a laugh out of the two of them. Brian rests his chin on one hand “Dirtboy, you are not getting back in touch with your ex to give him a suspicious elf drug”.

He blushes under his glasses. “...that wasn’t what I meant. I was talking more about social stuff. I swear I recognized one of the test subjects back at Excalibur. But now that you mention it, maybe we could convince Paige?”.

Brian’s thought about doing the same and warning his friends, but what can he say? This is all so unimaginable, and there’s not much they can do. Clay’s friends are more likely to die of this than his private-school teammates though. Brian also feels no instinct to protect his older brothers, but good on Clay for caring about his sister.

Sierra nods. “I wanted to run some more advanced tests on some of these elf gadgets too. Seems like there’s stuff elves don’t do with tech because magic can do it better. I’ve been thinking of a personal shield, like how Kebero deflected that shot during the car chase”. She turns to Clay. “Can you get someone to analyze the vaccine?”

He shakes his head. “I don’t think so. Smallpox would set off global alarms, and that would probably move the timeline of this invasion to, uh, right now”.

Which would end their grace period and get all of them captured. Going back home feels stifling. He’s spent the past month on the run, spending time with the most amazing people and living by his own merits. He doesn’t want the world to burn, but a smaller transformation instead? He could get behind a rebirth from the ashes if it’s just for him.

………………..

Even the meekest seneschals are spectacular liars, but Esther has more to hide than most. She is careful to act shocked, even horrified, when the Apex breaks the news that Marin’s new army broke the human girl out of captivity with ease, then adjusts that horror to a more personal type of fear when elves begin pointing fingers. Councilor Mercuralis, the Voyager turned backstabbing nobleman, declares that she was only rescued because Councillor Eburos was stupid enough to imprison the girl in a place the heirs had already infiltrated. Eburos snarls that there was no feasible way for the heirs to know she was hidden there, and questions if Councilor Marolak is having second thoughts about her change of allegiances. She accurately retorts that she had suggested holding Sierra on the other side of the planet, in one of the heavily guarded facilities where new human shock troops are raised. The details of that proposal never made it to the shining steel council table. The paper was misplaced in the shuffle, and when Daphne finds it a few days from now, she’ll surely hide the thing to save herself the blame.

She doesn’t have anything against the other woman. They’re cousins through biological fathers they barely know, and Marolak is a crueler master than Amedi, but if she doesn’t act, they’ll write the last lines of human history in this very room. Daphne will be fine. The only thing Marolak hates more than having a human handling her most secure documents is the time every few decades when she has to choose a new one.

She blinks up into the skylight. The room is cluttered and monitors cover the walls, but the glass ceiling lets in the sun. When she was younger, it felt almost holy. Now that she’s used to the nobility, it feels like a memorial. In the same way that water becomes a six-pointed snowflake, this is the shape that history takes when it crystalizes. No one has gotten enough sleep lately, least of all her. She doesn’t speak with the humans every night, but it’s enough that she’s not functioning as well as she should. Esther shouldn’t refer to them like that. They aren’t just any humans. They might even be friends, some day. Maybe that’s how this will end. Amedi will realize just how much she’s “taken a liking” to Marin's allies and charm her into revealing every secret she has.

The councilors take a vote. Ever since Lazarus Sondaica declared to the first Ishtar Mercuralis that he would not rest until her throne was his, the nobility have liked to call their mortal enemies, “adversaries”. The apex rules, and whoever has the strength to talk back receives the other title. Ishtar was the adversary once, and now she makes the proposal. Does Marin Sondaica deserve it? Have his actions, surviving their attacks, freeing his kin, rescuing that girl, warranted elevating him to this new height? Ryn almost laughs. Marolak recites a line from The Artificer, then says that maybe the humans can share it. The vote is unanimous. Marin is nothing more than a runaway.

.....................

this thing is now on indefinite hiatus. it's been very fun! I’ll probably be back someday but who knows. In total, this “season” or “book” or section of the story is about 75 thousand words. That is the length of a novel. I wrote the awful first draft of an actual novel chapter by chapter and I am quite proud!

The book Brian mentions is Jonathan Livingston Seagull. I also had to read it in middle school. It truly is that weird.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Bengal Tigers

The Bengal tiger, scientifically known as Panthera tigris tigris, stands as one of the most majestic and iconic creatures on our planet. It is a subspecies of the tiger and is renowned for its striking appearance, powerful physique, and enigmatic presence. This magnificent big cat is native to the Indian subcontinent and is often associated with the lush and diverse landscapes of countries like India, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Bhutan.

With its distinctive orange-gold fur adorned with black stripes, the Bengal tiger possesses a natural camouflage that helps it blend seamlessly into its forested habitat. These carnivorous predators are celebrated for their strength, agility, and stealth, making them apex predators in their ecosystems. Moreover, they play a crucial role in maintaining the ecological balance of the regions they inhabit.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

About Sunderbans National Park

Information About Sunderbans National Park, India

Covering an expanse of approximately 10,000 square kilometers, the Sundarbans forest spans across both India and Bangladesh. India claims around 4,262 square kilometers of this natural marvel, while the rest falls within Bangladesh's territory. Sundarbans National Park occupies the Indian portion, renowned globally for hosting the largest mangrove forest on the planet. This national park is a haven for nature enthusiasts and wildlife aficionados alike. With its thick mangrove cover, intricate network of river channels, picturesque estuaries, and a thriving population of Royal Bengal Tigers and various other wildlife species, the Sundarbans offers a captivating landscape that beckons visitors from far and wide. Recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the park possesses a unique allure that draws tourists seeking unparalleled natural beauty and biodiversity experiences.

Located at the southeastern edge of the 24 Paraganas district in West Bengal, India, the Sundarbans National Park derives its name from the Sundari mangrove plant (Heritiera Minor). Situated within the world's largest delta formed by the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Meghna rivers, this national park covers an expansive area of approximately 2585 square kilometers, making it India's largest national park and tiger reserve. The Sundarbans region encompasses around 2125 square kilometers of mangrove forest, while the remaining area, spread across 56 islands, is dominated by water bodies, totaling 4262 square kilometers.

Flora in Sundarbans National Park:

The Sundarbans, renowned as the largest mangrove forest globally, boasts the mangrove tree as its flagship species, thriving uniquely in its waterlogged terrain. With remarkable adaptability, these trees endure prolonged inundation by sending up spikes from their roots, aiding respiration and providing structural support to the mangrove ecosystem. Among its diverse array of flora, the Sundarbans is home to the 'Sundari' mangrove, a distinctive variety that dominates the landscape and lends its name to the forest. Encompassing over 300 plant species, the Sundarbans region harbors a rich botanical tapestry.

Fauna in Sundarbans National Park:

The Sundarbans National Park, dominated by the majestic Royal Bengal Tigers, reigns supreme as the apex predator with a population exceeding 400 individuals. These iconic tigers exhibit remarkable swimming prowess in the park's salty waters and are notorious for their occasional predation on humans. While tourists flock to catch a glimpse of these striped wonders, the park harbors a diverse array of fauna that equally captivates wildlife enthusiasts.

In addition to the Bengal Tigers, Sundarbans teems with captivating wildlife such as Fishing Cats, Leopards, Macaques, Wild Boars, Wild Buffaloes, Rhinoceroses, Indian Mongooses, Jungle Cats, Foxes, Flying Foxes, Pangolins, Barking Deer, Spotted Deer, Hog Deer, and Chitals. The park is also home to saltwater crocodiles and various snake species, adding to its rich biodiversity.

Moreover, Sundarbans boasts a vibrant avian population, featuring a kaleidoscope of exotic birds. Among them are Openbill Storks, Black-capped Kingfishers, Black-headed Ibises, Coots, Water Hens, Pheasant-tailed Jacanas, Brahminy Kites, Pariah Kites, Marsh Harriers, Swamp Partridges, Red Junglefowl, Spotted Doves, Common Mynahs, Jungle Crows, Jungle Babblers, Cotton Teals, Herring Gulls, Caspian Terns, Gray Herons, Common Snipes, Wood Sandpipers, Green Pigeons, Rose-ringed Parakeets, Paradise-flycatchers, Cormorants, Grey-headed Fish Eagles, White-bellied Sea Eagles, Seagulls, Common Kingfishers, Peregrine Falcons, Woodpeckers, Whimbrels, Black-tailed Godwits, Little Stints, Eastern Knots, Curlews, Golden Plovers, Northern Pintails, White-eyed Pochards, and Whistling Teals. These avian residents contribute to the park's enchanting atmosphere, making it a paradise for birdwatchers and nature lovers alike.

Climate of Sundarbans National Park:

The climate in the Sunderbans forest is generally temperate and pleasant, with temperatures ranging from 20 to 48 degrees Celsius. Due to its proximity to the Bay of Bengal, humidity levels are consistently high, averaging around 80%, and heavy rainfall is common. The summer season, lasting from March to May, is characterized by hot and humid weather. Monsoon conditions prevail from mid-May to mid-September, marked by increased humidity and windy conditions. The region frequently experiences storms, particularly in May and October, which can escalate into cyclones. Winter sets in from October to February, bringing colder temperatures to the area.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Terraforming Biodiversity

The seedships that arrived at Alpha Centauri had limited space on board for genetic samples, with parahuman and uplift DNA given the highest priority. The unfortunate result being that the vast majority of Old Terra's rich biodiversity died with that planet, leaving Secland and later terraformed worlds an extremely limited gene pool to work with.

During the terraforming process scientists struggled to fill in the niches left open by a gene bank weighed heavily towards domesticated and laboratory test animals. The possibility of making "downlifted" versions of the uplifted species was proposed but almost universally rejected by the uplifts in question. Instead, the Bureau of Ecosystem Management offered jobs to uplifts filling the ecological roles of their progenitors. This strategy worked surprisingly well, especially with apex predators such as dolphins.

Another approach was to modify the animals they did have using the non-human genes that had been incorporated into parahuman genomes. For instance Secland "bats" are actually heavily modified mice while the procyon is a fox given hand-like paws and a ringed tail.

Late in the terraforming process scientists made a breakthrough that would simplify later efforts. Large complexes of genes that could be activated or deactivated with specific epigenetic triggers were added to the genomes of many species that could produce massive physiological changes in later generations. That way a single breeding colony of ultra-ferrets could give birth to 20-centimeter long mini-ferrets, semi-aquatic ferr-otters, or two-meter mega wolverines as the ecosystem needed.

List of source species:

Mammals:

Cat (Felis catus)

Cattle (Bos taurus)

Dog (Canis lupus familiaris)

Ferret (Mustela furo)

Red fox (Vulpes vulpes)

House mouse (Mus musculus)

European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus)

Sheep (Ovis aries)

Birds:

Budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus)

Canary (Serinus canaria)

Chicken (Gallus domesticus)

Rock dove (Columba livia)

Zebra finch (Taeniopygia guttata)

Reptiles:

Green anole (Anolis carolinensis)

Spectacled caiman (Caiman crocodilus)

Fish:

Goldfish (Carassius auratus)

Zebrafish (Danio rerio)

Amphibians:

African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis)

Axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum)

Bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana)

Tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum)

Arthropods:

Fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster)

House cricket (Acheta domesticus)

Yellow mealworm beetle (Tenebrio molitor)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Texas entrepreneur working to bring back the woolly mammoth has added a new species to his revival list: the dodo.

Recreating this flightless bird, a symbol of human-caused extinction, is a chance for redemption. It might also motivate humans to remove invasive species from Mauritius, the bird's native habitat, said Ben Lamm, CEO and co-founder of Colossal Biosciences.

"Humanity can undo the sins of the past with these advancing genetic rescue technologies," Lamm said. "There is always a benefit for carefully planned rewilding of a species back into its native environment."

The dodo is the third animal that Colossal Biosciences — which announced Tuesday it has raised $225 million since September 2021 — is working to recreate.

And no, the company isn't cloning extinct animals — that's impossible, said Lamm, who lives in Dallas. Instead, it's focusing on genes that produce the physical attributes of the extinct animals. The animals it's creating will have core genes from those ancestors, engineered for the same niche the extinct species inhabited.

The woolly mammoth, for instance, is being called an Arctic elephant. It will look like a woolly mammoth and contribute to the Arctic ecosystem in a way that’s similar to the woolly mammoth. But it will technically be an Asian elephant with genes altered to survive in the cold. Asian elephants and woolly mammoths share 99.6 percent of their DNA.

The mammoth was the company's first project because it had long been a passion for Harvard University geneticist and Colossal co-founder George Church. He believes that Arctic elephants are the key to creating an Ice Age-like ecosystem with grasslands and grazing mammals, and this could help fight climate change by sequestering carbon under permanently frozen grounds that span areas including Siberia, Canada, Greenland and Alaska.

The altered genes could also give elephants a new habitat that’s far away from the destructive forces of (most) humans, and the company's gene editing technologies could help eradicate elephant diseases.

The company's de-extinction projects seek to fill ecological voids and restore ecosystems, Lamm said. The Tasmanian tiger, which Colossal announced as its second de-extinction animal in August of 2022, is a good example. This tiger was the only apex predator in the Tasmanian ecosystem. No other animal filled its place when it went extinct.

Apex predators eat sick and weak animals, which helps control the spread of disease and improves an ecosystem's genetic health. So the tiger's extinction could have contributed to the near-extinction of Tasmanian devils that lived in the same ecosystem, Lamm said.

For the dodo, Colossal is partnering with evolutionary biologist Beth Shapiro, a scientific advisory board member for Colossal who led the team that first fully sequenced the dodo's genome.

The dodo went extinct in 1662 as a direct result of human settlement and ecosystem competition. They were killed off by hunting and the introduction of invasive species. Creating an environment where the dodos can thrive will require humans to remove the invaders (the non-human invaders, anyway), and this environmental restoration could have cascading benefits on other plants and animals.

"Everybody has heard of the dodo, and everybody understands that the dodo is gone because people changed its habitat in such a way that it could not survive," Shapiro said. "By taking on this audacious project, Colossal will remind people not only of the tremendous consequences that our actions can have on other species and ecosystems, but also that it is in our control to do something about it."

The company has secured $150 million in funding to revive this bird and build an Avian Genomics Group, bringing the company's total fundraising to $225 million.

Colossal has more than 40 scientists and three laboratories working to recreate the woolly mammoth, and they hope to have mammoth calves in 2028. There are 30 scientists working on the Tasmanian tiger.

Reviving extinct animals is not a quick process, especially when considering the development of new technologies and the natural processes of Mother Nature (elephant gestation takes 22 months!). Some of Colossal's projects will take nearly a decade to complete, which is why the company is working to reintroduce multiple animals at the same time.

"Given the rapidly changing planet and various ecosystems heavily influenced by humankind, we need more tools in our tool belt to also help species adapt faster than they are currently evolving," Lamm said.

And the tools aren't limited to extinct animals. Colossal is developing technology that can benefit other industries, and it's spinning these out into new companies. Last year, it spun out a software platform called Form Bio that's designed to help scientists collaborate and work with their data, visualizing it in meaningful ways rather than looking at raw numbers in a spreadsheet.

"Synthetic biology will allow the world to solve various human-induced, world-wide problems," Lamm said, "like making drought-resistant livestock, curing certain disease states in humans, creating corals that are tolerant to various salinities and higher temperatures ... and much more."

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Animal Behavior Insights

"Whispers in the Wilderness: Insights into Indian Wildlife Animal Behavior"

Introduction

India, a land of diverse landscapes and rich ecosystems, is home to a mesmerizing array of wildlife. From the majestic Bengal tiger prowling the dense jungles to the graceful Indian elephant wandering the vast grasslands, each species exhibits unique behaviors that offer a captivating glimpse into the intricate tapestry of Indian wildlife. In this blog post, we delve into the heart of the subcontinent, exploring the behavioral insights of some of India's iconic wildlife.

Bengal Tiger: Master of Stealth

The Bengal tiger, Panthera tigris tigris, reigns as India's apex predator, navigating the lush forests with unmatched grace and power. The behavioral nuances of this magnificent big cat are a subject of fascination for wildlife enthusiasts and researchers alike.

One striking behavior of the Bengal tiger is its exceptional stalking and ambush prowess. These cats are masters of stealth, utilizing the dense vegetation to get within striking distance of their prey. Patiently observing their surroundings, they display a keen understanding of the art of surprise, an essential skill for survival in the competitive world of the Indian jungles.

In addition to their solitary hunting techniques, Bengal tigers also exhibit complex social behaviors, particularly during the mating season. The courtship rituals and interactions between individuals reveal a side of these big cats that goes beyond their reputation as solitary hunters.

Indian Elephant: Social Bonds and Emotional Intelligence

In the sprawling landscapes of India, the Indian elephant, Elephas maximus indicus, emerges as a symbol of strength, intelligence, and social complexity. These gentle giants display remarkable behaviors that highlight their strong sense of community and emotional intelligence.

One notable aspect of elephant behavior is their intricate social structure. Herds, led by a matriarch, consist of females and their calves, forming a tightly-knit family unit. Observing the communication within the herd, including vocalizations, body language, and tactile interactions, unveils the depth of their social bonds.

Moreover, elephants showcase empathy and mourning behaviors, particularly in response to the loss of a fellow herd member. Studies have documented elephants displaying signs of grief, such as lingering around the remains of a deceased companion and showing a subdued demeanor. These insights into the emotional lives of elephants challenge preconceived notions about the depth of feelings within the animal kingdom.

Indian Peafowl: Dance of Elegance

In the grassy meadows and open spaces of India, the Indian peafowl, or peacock (Pavo cristatus), captivates with its vibrant plumage and extravagant courtship displays. The peacock's behavior is a dance of elegance and flamboyance, designed to attract a mate.

During the breeding season, male peafowls unfurl their iridescent tail feathers into a breathtaking display, creating a mesmerizing fan of colors. This behavior, known as "train-rattling," is accompanied by intricate footwork and a series of calls. The purpose is to court and woo peahens, with the most elaborate displays often resulting in successful mating opportunities.

The peacock's courtship ritual is not only a visual spectacle but also a fascinating example of how certain behaviors in the animal kingdom have evolved to ensure the continuation of their species.

Indian Sloth Bear: Nurturing Bonds

Venturing into the scrub forests of India, the Indian sloth bear (Melursus ursinus) introduces us to a fascinating aspect of parental care and nurturing behavior. These bears, characterized by their shaggy fur and distinctive markings, exemplify a close-knit family structure.

Sloth bear mothers display remarkable devotion to their cubs, often carrying them on their backs or cradling them in their arms. This protective behavior extends beyond physical proximity, as mothers actively teach their cubs essential skills for survival, such as foraging and climbing. The strong maternal bonds observed in sloth bears emphasize the importance of family dynamics in the lives of these creatures.

Conclusion:

The behavioral insights into India's wildlife offer a profound appreciation for the complexities of the natural world. From the stealthy pursuits of the Bengal tiger to the emotional intelligence of the Indian elephant, each species contributes to the rich mosaic of Indian biodiversity.

As we observe and study these behaviors, it becomes evident that the lives of animals are marked by intelligence, social connections, and emotional depth. Preserving the habitats that support these remarkable creatures is not just a matter of conservation but also a commitment to safeguarding the intricate behaviors that make India's wildlife a source of wonder and inspiration. In understanding and respecting the behavioral intricacies of our fellow inhabitants on this planet, we foster a deeper connection with the natural world and cultivate a shared responsibility for its preservation.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

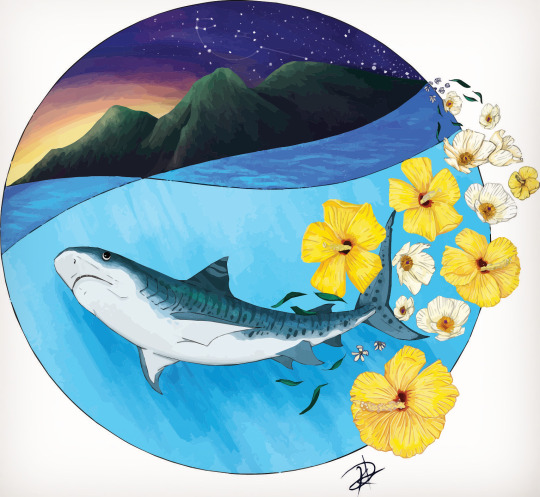

Manō Sunset! I wanted to do something featuring native and endemic Hawaiian flora and fauna. As a diver, tiger sharks are always a humbling animal to encounter out in the water: they’re as nerve-wracking as they are beautiful to witness up close. I’m truly lucky to have shared the water with these animals.

Niuhi or manō (tiger shark). Tiger sharks are apex predators and play a vital role in keeping ecosystems clean, healthy and balanced.

Tiger sharks can be considered ‘aumakua, the physical manifestation of the spirit of a relative or ancestor, who takes the form to look after and protect their families. Not all sharks are ‘aumakua, and not all ‘aumakua are sharks. However all sharks have a place of deep importance to Hawaiian culture and history.

Pua Kala (Hawaiian poppy): Hawaii’s only native poppy. While the blooms are short lived, they are one of the few few native flowers that can survive fire. This flower lives in dry woodland coastal regions on all the main islands.

Ma’o Hau Hele, known as the Hawaiian Hibiscus, this yellow hibiscus is Hawaii’s state flower. Sadly, it is now listed as an endangered species. Support organizations like the Waikoloa Dry Forest Initiative to help protect Hawaii’s invaluable native ecosystems.

The Kingdom of Hawai’i was illegally annexed by the U.S. and should be returned to its Native people. Learn more and stay updated with Native Hawaiian-led causes and activism, (such as shutting down the water-poisoning Red Hill Navy facility and the building of the thirty meter telescope on sacred land) here:

https://instagram.com/kanaeokana?igshid=MDM4ZDc5MmU=

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I’ve spoken before about my work documenting the rewilding of Saudi Arabia and the Arabian leopard as a powerful symbol of restoration and regeneration. I’ve spent days and days sitting calmly, waiting and watching these magnificent creatures. Although it can be frustrating (I’m not a patient person), I’m extremely happy to find that my work is becoming more difficult, more complex, with the arrival of each new cub. Here, we see the latest one. Born at the Arabian leopard breeding center in Taif, Saudi Arabia, these apex predators will one day be released back into this ecosystem. The center is operated by the Royal Commission for AlUla (RCU). This winter, RCU is releasing more than 1,500 Arabian gazelles, sand gazelles, Arabian oryx, and Nubian ibex into their ancestral habitat. #hvscofficial #leopard #wildlife #leopardprint #nature #animals #wildlifephotography #bigcats #fashion #safari #animal #cat #africa #cats #photography #tiger #bigcat #leopards #love #lion #wild #naturephotography #art #cheetah #catsofinstagram #style #animalprint #bengal #bigcatsofinstagram #cute https://www.instagram.com/p/CohuA_CpMve/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#hvscofficial#leopard#wildlife#leopardprint#nature#animals#wildlifephotography#bigcats#fashion#safari#animal#cat#africa#cats#photography#tiger#bigcat#leopards#love#lion#wild#naturephotography#art#cheetah#catsofinstagram#style#animalprint#bengal#bigcatsofinstagram#cute

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Raptors of Lemuria

For pictures see https://lemuriaspeculative.wordpress.com/2023/03/01/raptors-of-lemuria/

The largest birds of prey of Lemuria. Atop is the Rukh, followed by the Ningal (Lemurian Serpent Eagle) on the left and the Wagal (Lemurian Giant Falcon) on the right, the two giant eagle owls (larger U’uli and smaller N’ii), the Swagal (Lemurian Giant Falconet) and the various secretary owls.

Like many insular landmasses, the apex predators of Lemuria bear wings. Birds of prey are well known to attain insular gigantism and lord over island ecosystems, from the neighbouring Malagasy Crown Eagle to the Haast’s Eagle of New Zealand.

Unlike these birds, however, Lemuria’s largest birds of prey are not eagles, but rather unexpected species: owls, falcons and an Old World vulture. They are also relatively recent arrivals; previously, flying volaticotheres were the aaerial top dogs. The climatic changes resulting from the fusion of Maldivia and Marama as well as general Miocene climate changes ended much of the giant flying mammals, and allowed these upstarts to take their place at the top of the pecking order.

The largest of the falconets, the ancestors of the Swagal underwent a similar process as the Haast’s Eagle in New Zealand: an extremely rapid growth from a small bird into an aerial predator on the range of 13-14 kg and with a wingspan reaching 2.7 meters (females on average larger than the males, naturally). Having diverged from other falconets in the Pliocene, it was probably the first of Lemuria’s raptors to evolve, and subfossil remains dating to the early Pleistocene in the Great Lakes region seem to confirm that.

The Swagal is effectively the tiger of Lemuria, patrolling the dense rainforest habitats while the Wagal soars over the plains. It is the uncontested apex predator in the dense forest environments, both in the lowlands and at high altitudes, its talons capable of crushing anything from the hips of moamingos to the skulls of elephants. One female has even been reccorded attacking a freshwater dugong, dragging its body ashore. It nonetheless usually preffers smaller prey like mid-sized gondwanatheres and dryolestoids, which it can carry to the treetops to feed undisturbed by scavengers.

It is largely sedentary, adults forming strict territories; those of larger females may incorporate those of several males. Breeding takes place year round in rainforest habitats, after the wet season in slightly drier forests and in the (south hemisphere) summer in montane forests, every two years for the individual. Pairs last only during the breeding season, both male and female brooding and feeding the young bird for roughly an year, when it is near adult-sized and capable of fighting for its own territory; sexual maturity is reached at 6 years of age. The nest is a large platform on the tree canopies, though it occasionally also builds said nest on the ground, few predators willing to steal an egg or chick when at least one parent is around.

The Swagal has historically been the symbol of the Betsana Empire and subsquent east Lemurian nations, in contrast to the Wagal and west Lemuria. In a sense, it is analogous to the tiger while its open fields counterpart is analogous to the lion. A symbol of national pride, it is nonetheless endangered by deflorestation and revenge killings, as these birds are known to kill and eat even adult human beings.

It’s common name comes from the Werer language, from “seri” (broad, in this case “broad winged”) and Wagal (see below).

Weighting around 13-16 kg and bearing a wingspan of 3.3 meters, the Giant Falcon is the largest falconid in the world, a fitting giant in an island where the birds achieved uncontested supremacy of most raptor niches. Its exact position within its kin is unclear, but genetic studies place it most closely related to the hierofalcon line, probably having diverged from them in the Pliocene/Pleistocene boundary. The first subfossil remains apear in the mid-Pleistocene in the western Lemurian desert sites, implying that the species itself as we know it is a rather recent inovation.

Besides its massive size, the Wagal also possesses a proportionally larger and more powerful beak. As the apex predator of plains, savannas, steppes, semi-desert, alpine meadows and other open environments, it is the only falcon to specialize on mammals, attacking even the largest elephants, gondwanatheres and adapids by using the standard falcon techique of becoming a living missile. The talons, crushing through bones at such speeds, are then joined by the beak, inflicting even more damage. The prey is thus likely to die from shock very quickly. It is the raptor most specialized to feed on megafauna, rarely targetting prey smaller than a sheep, though it will frequently scavenge as well, its bulk enough to scare off most other carnivores. On occasion, it tackles bats and volaticotheres in flight.

There are two subspecies, the Western/Lasa Wagal (F. g. occidentalis) and the Eastern/Hesa Wagal (F. g. orientalis), the former being larger as it forages over a larger range that includes the western savannas and semi-deserts as well as the alpine plains, while the latter is confined to pockets of savanna in the eastern peninsulas. The Lasa Wagal is the one depicted and differs also from its smaller cousin by a brighter colouration.

The Wagal breeds either in the wet season or during the (south hemisphere summer) in the case of highland populations. The nest is a shallow cove on the ground, no predator willing to face the angry birds. Pairs mate for life, and brood the egg and raise the chick for a period of about an year. Sexual maturity is reached at nine years of age, and breeding intervals can take up as many as three years.

Hisotrically, the Wagal has symbolised the Arrokath Empire and subsequent western Lemurian nations. It is the most revered of the giant raptors, with even its eastern populations being seen as majestic, if lesser to the Swagal. During the Chola Dynasty the bird become a pan-Lemurian symbol, until the “rivalry” between the west and east was restored. It’s biggest threat today is the decline of megafauna due to environmental disruptions, though some farmers are willing to sacrifice cows to help these birds survive.

If the Wagal lords over the plains and the Swagal over the forests, then the Ningal rules over the wetland habitats. It is particularly fond of the unique Sammangal environment, where it resides during the dry season (when it also breeds) and migrates to more conventional wetlands such as deltas when the monsoon floods its hunting grounds.

Of the giant raptors, it seems to be the most recent arrival, having diverged from the Malagasy Serpent Eagle (Eutriorchis astur) around the late Pleistocene at 500,000 BCE. Like other raptors it underwent a rapid growth, attaining a maximum body weight of 15 kg and a wingspan of three meters, though unlike the Swagal and the Wagal it didn’t become entirely dependent on megafauna. In fact, it hunts all manner of prey from locusts to caecilians to fish to moamingos to hippos, with peafowl seemingly being its preferred prey.

As mentioned above, it breeds during the Sammangal dry season, when peafowl and other large animals roam the desiccated wetland; populations in more normal wetlands breed year-round. The birds engage in momentary monogamy, selecting a mate for the season and thus a territory, their loud, shriek-like calls heard throught the day in order to keep other birds at bay. Both parents incubate a single egg for about 38 days on a nest built on a tree (to avoid freak floods), and raise the chick for two months. The young birds may stay up to yet another month in the territory of their parents, learning how to hunt, before being chased off. Sometimes, large numbers may gather at a large carcasse, particularly young birds without full territories of their own. Sexual maturity is reached at around 5 years of age.

Unlike the Swagal and Wagal, the people’s of Lemuria have a more complicated relationship with this bird. It is the major antagonist in the national epic The Drama of the Moon, where it appears as a Set-like figure. With the arrival of Buddhism, it became equated with the Mahakala, a fearsome guardian figure. While rarely outright persecuted, this bird is currently largely endangered due to wetland removal, and it isn’t nearly as charismatic as its falconid counterparts.

The largest of the lemurian apex predators, the Rukh is also one of the largest flying birds in the world and without doubt the largest true raptor, bearing a wingspan of 4.5 meters and a body weight of 15 kg. Bearing a rather aquiline appearence and a fully feathered head, it is very similar to the Cinereous Vulture, but its relations are somewhat more complicated, in great part because it is very clear that it, the Cinereous Vulture, the Lappet-Faced Vulture, the Red-Headed Vulture and the White-Headed Vulture are all very close relatives. For convenience’s sake, the bird is reffered here in the “genus” Aegypius, but its actual relationships within this clade are not fully resolved. Regardless, it has been around since the Pliocene/Pleistocene boundary, subfossil remains occuring both in desert and alpine sites. This makes it the oldest lemurian raptor to appear in the fossil reccord.

Like the Wagal, the Rukh occurs in open environments; due to its size, it frequently soars at high altitudes and thus above forests, having no subspecies. Stray birds may even occur in South Asia, Madagascar or even Africa. It is primarily a scavenger, though it can take kills as large as an elephant calf. Such depictions no doubt inspired the Middle Eastern stories of these birds hunting elephants, though such events are comparatively rare. On occasion, it might stalk small prey on the ground like a stork or secretary bird, but it generally hunts from above like most raptors.

The Rukh breeds year round, though breeding intervals may take up to 4 years. It mates for life, pairs reinforcing their bonds through elaborate dances and aerial talon-locking spectacles. The nest is often built on the ground, but it is no stranger to nesting on the trees or cliffs. A single egg is laid and incubated for about 70 days, resulting in a small semi-altricial white downed chick. Moulting first occurs at 30 days of age, with the development of flight feathers, and is completed by 60. Fledging occurs around 130 days or so after hatching, but the young stay with the parents for up to another 4 months before leaving. Sexual maturity is reached at around 10 years of age, and the birds are known to live for as long as 70 years. Breeding success is, as per most of its relatives, very high, only other giant raptors posing a negative impact.

Middle-Eastern stories aside, the Rukh is generally seen as a peaceful bird, no doubt due to it preffering to scavenge over hunting and its white plummage. Many lemurian burials are sky burials, feeding these noble birds (and, if the deceased is lucky, a passing Wagal or Swagal). Like other vultures it is vulnerable to diclofenac poisoning, but thanks to its role in sky burial rituals diclofenac is officially banned in Lemuria.

The U’uli is one of two of Lemuria’s native giant eagle owls. It represents the second wave of eagle owl immigration, having diverged from the Eurasian Eagle Owl in the late Calabrian, coinciding with the extinction of a previous giant owl species, Aquilostrix faciens, and the first unambiguous remains come from the early Ionian. Subfossil remains are found throught the island, matching the bird’s widespread range. It occurs in all manner of habitats from semi-desert to wetlands, avoiding only the most dense forests.

Adults can reach 19 kg and a wingspan of 3.7 meters. In spite of these, they rarely target larger prey, as like most owls they suffocate their prey rather than pierce them with their talons; it hunts anything from locusts to mammals as large as pigs. Being rather versatile, it can thrive easily by avoiding competition with other giant raptors and targetting prey that they aren’t targetting. Wagals and swagals going for megafauna? Pick caecilians and fowl. Rukhs going for carcasses? Pick living prey. Swagal eating peafowl? Pick carrion. And so forth.

Such adaptability means it can breed year around, though highland populations preffer the (southern hemisphere) summer and those in the Sammangal the dry season. Like many raptors it nests on the ground, usually using used peafowl nests. Like other eagle owls, both partners engage in “duetting”, bowing and calling to each other. The female lays up to four large white eggs, and won’t leave the nest for 47 days, her mate bringing her food during this period. The chicks are raised for about four months, before leaving the territory. Sexual maturity is reached at around 5 years of age.

Like most owls, the U’uli has an ill reputation as an omen of death, though it’s size makes it a formidable adversary (though these birds rarely ever attack humans aside from defending their nests). It is thus often personified as the god of evil and the night in opposition to the Sun Goddess in many lemurian cultures. By far the main threat to its existence is persecution, particularly as they are not at all bothered by urbanisation and often nest on rural and even suburban areas.

Despiste being the exact same size as an Eurasian Eagle Owl, the N’ii represents an older owl clade, having diverged from its mainland relative in the Pliocene/Pleistocene boundary. What it lacked in size, it developed in skill; unlike most owls, which suffocate their prey, this bird hunts by piercing its prey like diurnal raptors do, an atavism as ancient owls also did this. This feature is shared with the extinct Aquilostrix faciens, and some researchers consider moving either the N’ii to that genus or A. faciens to Bubo. A. faciens once roamed most of the island, disappearing with the arrival of the U’uli.

Is the N’ii a remnant? Who knows, because both birds co-exist in its montane habitat, the N’ii occuring both in the montane forests and meadows. It is a specialized hunter, preying upon the endemic bear-sized lagomorph the Uaemotol, though it has also been reccorded attacking gondwanatheres and even humans. It’s piercing talons surely allow it to tackle proportionally larger prey than the larger U’uli.

Like most piercing predators it hunts from above, descending unto the prey’s back. But otherwise it spends most of its time on the ground; a N’ii might track a Uaemotol purely by sound for days by walking, then flying up silently and descending upon the unsuspecting prey.

Like its larger cousin, it nests on the ground, during the (south hemisphere) summer. Like other eagle owls, both partners engage in “duetting”, bowing and calling to each other. The female lays a single white egg, and won’t leave the nest for 47 days, her mate bringing her food during this period. The chick is raised for about two years, before leaving the territory. Sexual maturity is reached at around 11 years of age.

Due to its isolated alpine habitat, it has little interactions with humans. It’s name is an onamatopeia given by the Ragar people which it shares its environment with, which otherwise steer clear from this omen of death. Deflorestation is the main hazard to this species, with occasional persecution being a minor problem since few people live in the highlands.

Secretary Owls (Tytogrus)

These unique barn owls have specialised to a more terrestrial way of life, developing long legs and necks. Stalking both during the day and night, these birds only take flight to avoid predators or cover larger distances, otherwise preferring to run and walk. They are by far the oldest giant raptors, having diverged from other owls in the late Miocene, before the birds replaced the giant flying mammals as top predators. An extinct species, Tytogrus rangiferi, is well attested in numerous sites across the East Peninsula as recently as 30,000 BCE, and is possibly ancestral to the Avana and G’ulia.

Due to their more diurnal habits and comical apparence, these birds are generally seen more positively than other owls, and are in fact often welcomed to clear out pests. Still, a few species are endangered due to habitat or prey loss. They are seldomly distinct in most cultures; the names given here are all regional names applying to the birds as a whole in the native dialects.

The largest of the secretary owls at a height of 1.4 meters and a wingspan of 2.5 meters, the Sagu’ul is a truly imposing resident of the savannahs and veldt of western Lemuria, occuring more rarely along northwestern forest mosaics. It bears a distinctively white-grey plummage, with dark brown remige and retrice uppersides, an orange-golden facial disk and leg feathers and a black shoulders. Its neck plummage seems rather disporportionally thin compared to the large facial disk, from a distance making it look like a very unusual crane. Unlike those birds, though, the Sagu’ul is almost always seen alone or in pairs, hunting at day or night for primarily small mammals and ground dwelling birds, occasionally also hunting reptiles, arthropods and, on rare occasions, stomping large caecilians to death.

Like most of its kin, the Sagu’ul spends most of its time on the ground, striding through the tall grass or barren fields, either chasing after prey or pouncing in the vegetation, but it bears massive wings and it is a frequent flyer, either travelling long distances in search of new hunting grounds or performing bizarre maneuvers. Mated pairs frequently chase after each other in the air, and perform strange tricks, locking talons and intentionally bumping into each other. When threatened, it usually runs away, flying only when escaping ground dwelling predators like large sphenodonts, as aerial predators like the Wagal and the Rukh can seldomly be evaded on the air.

It breeds year round, though within intervals of up to 4 years. Both parents use a hole in the ground, usually one already dug by gondwanatheres or other mammals, but they can dig on their own, creating a burrow of up to 2 meters in depth. There, both parents incubate two large white eggs for up to 60 days, and raise both chicks for around 9 weeks, before they’re kicked out. Birds reach their sexual maturity at 6 years of age, and have relatively high breeding success rates at 89%, as few predators dare to attack their eggs and chicks.

At around 1.3 meters of height, the G’ulia is found across the southeastern East Peninsula, occuring through a variety of open environments, preffering savannahs and tropical grasslands but also occuring in open woodlands and similar mosaics. It has a largely light brown plummage, with darker wing feathers and white facial disks, tail feathers and leg “socks”, females also possessing white dots on the chest, while juveniles are predominantly black. It is most closely related to the Avana, and as such it shares some peculiarities with it, like a whistling, high pitched bark-like vocalisation that it uses when communicating over large distances, as well as a higher tolerance for woodland biomes and a higher content of insects and amphibians in its diet compared to the Sagu’ul and Tureia, preffering them to the largely mammalian prey of those species. That said, up to 46% of its diet is still composed by small mammals.

In some areas, G’ulia have a tendency to follow large mammals like elephants and large gondwanatheres, feeding on animals fleeing the giants, insects attracted by their dung and sometimes even stealing the placentas. Normally solitary, several birds may gather around in the wet seasons, tolerating each other more eagerly than normal.

Like most secretary owls, it nests on burrows, though like the Avana it may also do so in hollow tree trunks. It is a rather seasonal breeder, preffering to incubate its eggs around the dry season, and raise its young during monsoon months. Sexual maturity is reached at 5 years of age, with breeding intervals lasting for around 3 years.

The smallest of the secretary owls, the Avana stands at merely a meter tall. A largely brown coloured bird aside from the white “socks” and black facial disc, it inhabits the scrubland, semi-desert, forested savannahs and dry woodlands across the southwest of Lemuria, its range just to the south of the Sagu’ul’s, though they overlap significantly in the center-west savannah systems. In the late Pleistocene, its range appears to have extended more throughly across the center and east of Lemuria, including many areas now governed by Sammangal wetlands, and it clearly diverged from the G’ulia later than from the rest of its clade, and both were probably also particularly closely related to Tytogrus rangiferi.

The Avana is a rather insectivorous bird, with 56% of its diet being composed of large insects like grasshoppers and beetles, and the owls frequently forage on termites. It also feeds largely on frogs and squamates, with mammals, birds and sphenodonts composing a relatively small part of its diet at 20%. It is the only secretary owl to be primarily nocturnal, rarely foraging at midday, though it is frequently active at dusk and dawn.

Unlike other secretary owls, it rarely digs, preffering to nest on hollow trunks. Also unlike virtually all other owl species, it lives in small family units, the young remaining with their parents until they reach sexual maturity at 5 years of age, helping to raise the next generation and to defend their territory. At night, Avana family units produce loud calls in unison, a strange an alien chorus common throught their range.

Similar in size to the Sagu’ul, the Tureia is a rather different bird. It has a primarily black plummage aisde from the torso and wing undersides and the golden facial disc, and while all secretary owls have feathered legs, it has also feathered toes, contrastingly white in colour. Having diverged earlier from its relatives soon after the initial split, it is rather distinct from its relatives in many aspects, and its not clear if these are remnants from the last common ancestor between all these birds, or the result to its highland environment.

The Tureia inhabits the central lemurian highlands, in particular open alpine meadows and steppes, as well as the wetland mosaics and, more rarely, open Nothofagus complexes; it is sedentary, seldomly migrating to lowlands, though it is rather nomadic and frequently crosses valleys at high altitudes, there being virtually no isolation within its range. It is almost exclusively diurnal, rarely hunting at night, and it has a prefference for mammalian prey, small gondwanatheres composing up to 86% of its diet, though it also feeds on tenrecs, flying mammals, birds, frogs, caecilians and sphenodonts. More rarely it may target large prey, pairs ganging on wounded large gondwanatheres or dryolestoids and eating them alive. Though such events may allow an increase of individual tolerance, most birds are strictly solitary, emitting loud, songbird-like calls that are rather melodious in sound, if bellying a darker intention.

Also unlike most secretary owls, it nests on a shallow cove, not digging burrows or using trunks, much like other large terrestrial birds. It breeds during alpine spring months, the eggs being incubated for about 57 days and the young raised on the nest for three weeks, before they can walk and run, and thus accompany the parents on foot while they stride. Another six weeks, and they develop their adult plummage, and stay with their parents for about another month before leaving. Sexual maturity is reached at 8 years of age, and breeding intervals may last up to 6 years. They have virtually no predators aside from the Wagal, the eagle owls and the Rukh.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Majestic Life of Tigers in the Wild