#Thurmond Wisdom

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Thurman Wayne Wisdom, 90, of Greenville, SC passed away on May 4, 2022.

Thurman was born July 18, 1931, in Ratcliffe, Arkansas, a son of Elizabeth Rankin and Samuel Baldridge Wisdom. In 1949 he graduated from East Detroit High School in East Detroit, Michigan. After graduation, he joined the Air Force and was stationed in England until his honorable discharge in 1955. He often joked that he flew a Royal (typewriter) in the Air Force. He went on to study theology at Bob Jones University graduating cum laude in 1959. He continued his education and received his MA in 1960, and his PhD in 1975. He married Mary Perkins in 1966. Thurman and Mary went on to have three children, Stephanie Lynn Wisdom Mikkelsen (Doug), Stephen Wayne Wisdom (Debora, deceased), and Daryl Thurman Wisdom.

He taught at Bob Jones University for 42 years from 1961-2004 when he retired at the age of 73. He was the Dean of the School of Applied Studies and later became Dean of the School of Religion from 1978-2000. In addition to teaching, he traveled 20 times to Russia and Ukraine to minister there. He also traveled and taught in Australia, the Philippines, Singapore, Mexico, and Costa Rica. In 2006, he published a book called A Royal Destiny: The Reign of Man in God's Kingdom. After his retirement he continued to preach almost every Sunday at Shepherd's Care Assisted Living Center and was a member of the Gideons. In his free time, he enjoyed eating toast and drinking coffee, reading, playing chess, and spending time with his grandchildren.

Thurman was predeceased by his parents and three infant siblings, Gerald, Beal, and Wilma all in 1928, following the Arkansas flood of 1927; his adult brother, James Max Wisdom; and his daughter-in-law, Debora Wisdom. In addition to his wife, he is survived by his sisters, Nina Woods, Delena Ickes, and Kay Wisdom; his children Stephanie Lynn Wisdom Mikkelsen (Doug), Stephen Wayne Wisdom (Debora, deceased) and Daryl Thurman Wisdom; and his seven grandchildren, Sage, Reece, Hadley, Schaeffer, and Ridge Mikkelsen, and Nicholas and Grayson Wisdom.

A memorial service and visitation will be held at Hampton Park Baptist Church on Monday May 9, 2022. Visitation is at noon, with the service at 1 p.m.

#Bob Jones University#Archive#Obituary#BJU Hall of Fame#BJU Alumni Association#2022#Thurmond Wayne Wisdom#Dean of the School of Religion#BJU Administration#Class of 1959#Hampton Park Baptist Church

0 notes

Text

THIS DAY IN GAY HISTORY

based on: The White Crane Institute's 'Gay Wisdom', Gay Birthdays, Gay For Today, Famous GLBT, glbt-Gay Encylopedia, Today in Gay History, Wikipedia, and more … December 15

boys, wear your pearls today!

1904 – W. Dorr Legg (d.1994), was a landscape architect and one of the founders of the United States gay rights movement, then called the homophile movement.

He trained as a landscape architect at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor and from 1935 was professor of landscape architecture at Oregon State Agricultural College (now Oregon State University), but moved back to Michigan in the 1940s to care for his father and the family business. While there he fell in love with Merton Bird, an accountant.

Hoping to find a social environment more accepting of their interracial relationship, Legg, who was white, and Bird, an African American, moved to Los Angeles in 1949. Shortly thereafter the couple founded a social organization for interracial gay couples, the Knights of the Clocks, a name that Legg called "deliberately ambiguous." The society flourished for several years in the early 1950s.

The couple actively joined the national Mattachine Society, but Legg later led a split to co-found ONE, Inc.. Legg and Bird were among the six original members of ONE, which took its name from a line by Thomas Carlyle, "A mystic bond of brotherhood makes all men one."

Legg gave up his career as a landscape architect to become the business manager of the organization's monthly publication, also called ONE, the first issue of which appeared in 1953. It became the first widely distributed gay publication in the United States.

The magazine was a slim volume at first, typically running from twenty to thirty pages in length. The content initially consisted mainly of essays on topics of interest to the gay community but also included stories, poems, and book reviews. As time went on, the magazine grew, featuring articles on gay studies in the humanities, social and natural sciences, and medicine. By the end of the 1950s, the magazine had attained a distribution of five thousand copies.

The United States Post Office confiscated the October 1954 issue of ONE on the grounds that it was "lewd, obscene, lascivious and filthy" and could therefore not be sent through the mails.

ONE sued Los Angeles Postmaster Otto K. Olesen, who prevailed in the first round when in March 1956 U. S. District Judge Thurmond Clark agreed that the publication was obscene. He also stated that "the suggestion that homosexuals should be recognized as a segment of the populace is rejected."

ONE appealed the decision in the Ninth Circuit, which upheld the lower court's ruling in March 1957. The case next went to the United States Supreme Court.

The justices ruled in favor of ONE in January 1958. Their decision in ONE, Incorporated v. Olesen was per curiam, meaning that they held the issue to be so obvious that no lengthy written opinion was needed.

The news media gave the Supreme Court decision scant attention. Nevertheless, the case was a landmark, establishing the right to send gay and lesbian material through the mail. It had enormous consequence for the fledgling rights movement.

ONE remained in publication until 1969. Financing it had long been a problem. Donors had helped keep the magazine afloat, but the loss of their monetary support combined with a loss of readership to magazines of a more radical viewpoint made the enterprise no longer viable.

Legg traveled to Germany in the 1950s to recover the remains of the archives of the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft.

Legg died in Los Angeles on July 26, 1994 of natural causes. He was survived by his life partner of thirty years, John Najima.

In 2011 the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association announced that Legg would be inducted into its hall of fame.

1937 – In his explicitly gay works, Mutsuo Takahashi, internationally recognized poet and playwright, celebrates homosexual desire.

Takahashi was born in Japan on December 15, 1937, and educated at Fukuoka University of Education. He has published several volumes of poetry, including You Dirty Ones, Do Dirtier Things (1966), Poems of A Penisist (1975), The Structure of The Kingdom (1982), A Bunch of Keys (1984), Practice/Drinking Eating (1988), The Garden of Rabbits (1988), and Sleeping Sinning Falling (1992).

As a child, Takahashi spent much time with extended family and other neighbors. Especially important to him during this time was an uncle that served a pivotal figure in Takahashi's development, serving as a masculine role model and object of love. However, historical fate intervened, and the uncle, whom Takahashi later described in many early poems, was sent to the battlefield in Burma, where illness claimed his life.

Takahashi and his mother went to live in the port of Moji, just as the bombings of the mainland by the Allied powers intensified. Takahashi's memoirs describe that although he hated the war, World War II provided a chaotic and frightening circus for his classmates, who would go to gawk at the wreckage of the B-29s that fell from the sky and to watch ships blow up at sea, destroyed by naval mines. Takahashi writes that when the war came to an end, he felt a great sense of relief.

In his memoirs and interviews, Takahashi has mentioned that in the time he spent with his schoolmates, he became increasingly aware of his own sexual preference for men. This became a common subject in the first book of poetry he published in 1959.

Few poets bring as much skill and passion to their poems, especially those that consider homosexual desire. His work in drama has also earned acclaim. He won the Yamamoto Kenkichi Prize in 1987 for his stage script called Princess Medea. Other works in drama include an adaptation of W. B. Yeats's play At The Hawk's Well and a noh play inspired by Georges Bataille's Le Procès de Gil de Rais.

Even in his earliest work, Takahashi writes with vitality and precision about homosexual desire. Although Japan does not outlaw homosexual relations, the homosexual there remains an outcast because often he does not engage in the rituals and practices of Japanese family life.

The "okama" ("queen") is laughed at and ostracized. The more he is ostracized, the easier it is to keep the laughter going—at the okama's expense. Takahashi's poems give dignity to the okama, celebrating both his sexual desires and his outcast status.

Homoeroticism was an important them in his poetry written in free verse through the 1970s, including the long poem Ode, which the publisher Winston Leyland has called "the great gay poem of the 20th century." Many of these early works have been translated into English by Hiroaki Sato and reprinted in the collection Partings at Dawn: An Anthology of Japanese Gay Literature.

About the same time, Takahashi started writing prose. In 1970, he published Twelve Views from the Distance about his early life and the novella The Sacred Promontory about his own erotic awakening. In 1972, he wrote A Legend of a Holy Place, a surrealistic novella inspired by his own experiences during a forty-day trip to New York City in which Donald Richie led him through the gay, underground spots of the city. In 1974, he released Zen's Pilgrimage of Virtue, a homoerotic and often extremely humorous reworking of a legend of Sudhana found in the Buddhist classic Avatamsaka Sutra.

Moreover, most of Takahashi's explicitly gay work celebrates desire, finding joy in the male body much as Walt Whitman's poems do. The poems eagerly name body parts as they probe desire and longing.

The speaker of Takahashi's masterful poem "Ode" celebrates his erotic and promiscuous life much as a priest celebrates the Eucharist. This 1,000-line poem begins with a parody of the Mass: "In the name of / Man, member, / and the holy fluid, / AMEN." As the speaker seeks out sex in the places most frowned on by his society, he is reborn, saved by each new encounter. The glory hole, for example, takes on spiritual significance. Only what is "made flesh" satisfies.

Poems of A Penisist is one of the most important collections of poetry on homosexual desire and sex written in this century. The personae in these poems do not compromise—they see the world as outsiders ("a faggot that fingers point at") but being outsiders brings them joy and meaning. As the majority society mocks and condemns them, their joy in their identity as gay men, as individuals who enjoy pleasure with other men, gives them strength.

1958 – Alfredo Ormando, Italian homosexual, who committed ritual suicide to protest Church policies toward homosexuality.

Ormando was one of eight children from an impoverished family, who had been struggling to make a success of a writing career, after spending two years in a seminary. He had been suffering from serious depression, which clearly had multiple causes.

In December 1997 he wrote this letter to a friend of his in Reggio Emilia:

Palermo, Christmas 1997 Dear Adriano, this year I can't feel it's Christmas anymore, it is indifferent to me like everything; nothing can bring me back to life. I keep on getting ready for my suicide day by day; I feel this is my fate, I've always been aware but never accepted, but this tragic fate is there, it's waiting for me with a patience of Job which looks incredible. I haven't been able to escape this idea of death, I feel I can't avoid it, nor can I pretend to live and plan a future I do not have; my future will just be a prosecution of this present. I live with the awareness of who's leaving this life and this doesn't look dreadful to me! No! I can't wait for the day I will bring this life of mine to an end; they will think I am mad because I have chosen Saint Peter Square to be the place where I'll set myself on fire, while I could do it here in Palermo as well. I hope they'll understand the message I want to convey; it is a form of protest against the Church which demonises homosexuality, demonising nature at the same time, because homosexuality is its daughter. Alfredo.

On 13 January 1998 he set himself on fire in Saint Peter's Square in Rome to protest the attitudes and policies of the Roman Catholic Church regarding homosexual Christians. After two policemen put out the flames, he was brought to Sant'Eugenio hospital in critical condition. He died there 11 days later.

After his death, the Vatican denied that this had anything to do with the Church or homosexuality. Through its spokesperson, Father Ciro Benedettini, the Church downplayed the significance of the act.

In 2000, the year of the Jubilee, Pope John-Paul II exhorted his followers in the same spot where Alfredo Ormando had set himself on fire two years prior, telling them that homosexuality was "unnatural," and that the Church had a "duty to distinguish between good and evil."

In 2005, the new Pope Benedict committed himself to even harsher anti-gay teachings, initiating what some see as a gay witchhunt within the Catholic clergy, fighting same-sex partnership legislation worldover, and sending the message that homosexuals have no place in God's kingdom.

However, in September 2013, Pope Francis said the church shouldn't "interfere spiritually" with the lives of LGBT people in a wide-ranging interview in which he also said the church cannot focus solely on opposing abortion, contraception, and marriage equality. A month earlier, the pope told a group of reporters that he wouldn't judge gay priests, asking, "If someone is gay and seeks the Lord with good will, who am I to judge?"

Change comes slowly in the Catholic church.

1961 – Jack Halberstam, also known as Judith Halberstam, is Professor of American Studies and Ethnicity, Gender Studies, and Comparative Literature, as well as serving as the Director of The Center for Feminist Research at University of Southern California (USC). Halberstam was the Associate Professor in the Department of Literature at the University of California at San Diego before working at USC. He is a gender and queer theorist and author.

Halberstam, who accepts masculine and feminine pronouns, as well as the name "Judith," with regard to his gender identity, focuses on the topic of tomboys and female masculinity for his writings. His 1998 Female Masculinity book discusses a common by-product of gender binarism, termed "the bathroom problem" with outlining the dangerous and awkward dilemma of a perceived gender deviant's justification of presence in a gender-policed zone, such as a public bathroom, and the identity implications of "passing" therein.

Assigned female at birth, he uses the pronouns "he/his" with regard to his gender identity and goes by the name Jack, but says that "some people call me Jack, my sister calls me Jude, people I've known forever call me Judith" and "I try not to police any of it. A lot of people call me he, some people call me she, and I let it be a weird mix of things." The name "Judith Halberstam" has also accompanied "Jack" on some of Halberstam's later books.

Halberstam acknowledges that he is "a bit of a free floater" when it comes to pronouns. He said that "the back and forth between he and she sort of captures the form that my gender takes nowadays" and that the floating gender pronouns have captured his refusal to resolve his gender ambiguity. Halberstam does, however, state that "grouping me with someone else who seems to have a female embodiment and then calling us 'ladies', is never, ever ok!"

Jack is a popular speaker and gives lectures in the United States and internationally on queer failure, sex and media, subcultures, visual culture, gender variance, popular film and animation. Halberstam is currently working on several projects including a book on fascism and (homo)sexuality.

1974 – We're not sure of the exact date but sometime in December 1974, two Boston Gay rights activists, Bernie Toal and Tom Morganti, created a symbol of Gay pride. It was not to have lasting influence but it's damned cute and certainly speaks to the creativity that occurred in the years following the Stonewall uprising. The symbol was the purple rhino. The entire campaign was intended to bring Gay issues further into public view. The rhino started being displayed in subways in Boston , but since the creators didn't qualify for a public service advertising rate, the campaign soon became too expensive for the activists to handle. The ads disappeared, and the rhino never caught on anywhere else. As Toal put it, "The rhino is a much maligned and misunderstood animal and, in actuality, a gentle creature. But when a rhinoceros is angered, it fights ferociously." At the time, this seemed a fitting symbol for the Gay rights movement. Lavender was used because it was a widely recognized Gay pride color and the heart was added to represent love and the "common humanity of all people." The purple rhinoceros was never copyrighted and is in the public domain.

1994 – Jason Brown is an American figure skater. He is a nine-time Grand Prix medalist, a two-time Four Continents medalist (2020 silver, 2018 bronze), and the 2015 U.S. national champion. Earlier in his career, he became a two-time World Junior medalist (2013 silver, 2012 bronze), the 2011 Junior Grand Prix Final champion, and the 2010 junior national champion.

At only 19, Brown won a bronze medal in the team event at the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, becoming one of the youngest male figure skating Olympic medalists.

He came out as gay via Instagram post on June 11, 2021.

2000 – The Supreme Court of Canada finds in favor of the Crown in the Little Sister's Book and Art Emporium v. Canada obscenity case. However, they found that the way the law was implemented by customs officials was discriminatory and should be remedied, an opinion they suggested would avail the bookstore in any further legal battles

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

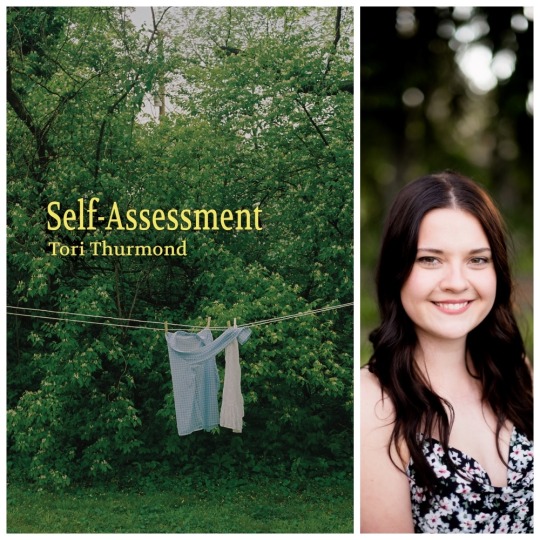

FLP CHAPBOOK OF THE DAY: Self-Assessment by Tori Thurmond

On SALE now! Pre-order Price Guarantee: https://www.finishinglinepress.com/product/self-assessment-by-tori-thurmond/

Self-Assessment includes #poems of noticing, growth, and longing. Who the speaker is and who she wants to be recognize each other in these poems. Gleaning inspiration from landscapes like the winding roads of the American South and the cold beaches of the Pacific Northwest and placing them alongside surreal, dream-like scenes, the speaker is allowed to openly examine herself with honesty and invites the reader to do the same.

Tori Thurmond originates from Nashville, Tennessee. She earned her MFA in poetry from Eastern Washington University in Spokane, Washington where she served as the poetry editor for Willow Springs Magazine. Her work has previously been published in Nashville Poet’s Quarterly, Tiny Seed Journal, Black Bear Review, and The Racket Journal and has been accepted to several national conferences across the US. She is currently living in Nashville working in marketing as a copy writer and reading and writing as much poetry as she can.

PRAISE FOR Self-Assessment by Tori Thurmond

“In Tori Thurmond, a new generation of American poetry has found its Rory Gilmore, its Jo March, its Dusty Springfield. Her poems give us the coming of age of a woman poignantly wistful and coolly astute, charmingly witty and scrupulously insightful, imaginatively inventive and exactingly observant. As convincingly as any young poet I know, she inhabits her life—from the company of a childhood park dragon to first adult heartbreak, from her dogwood-blooming yard in Tennessee to a driftwood-strewn beach in the remote Pacific Northwest—with a reverential, even ceremonial affection. Travel these pages with her and remember and relearn what it is to live that authentically.”

–Jonathan Johnson, author of May is an Island, Hannah and the Mountain: Notes toward a Wilderness Fatherhood, and other works

“With guileless, disarming intimacy, Thurmond’s Self Assessment ushers us into interior experiences: inside a car driven by an ex, into the living room of a burning house, to the sweat-damp skin beneath a fuzzy green bathrobe. And even while the speaker assesses her desires as “selfish,” these generous poems are always expanding out to a vibrant, blossoming world beyond private concern to become a part of something larger: “and yet still / a part of pink huckleberries. / Aspen trees. Spruce.”

–Bethany Schultz Hurst, author of Blueprint and Ruin and Miss Lost Nation

“Tori Thurmond’s Self-Assessment hums with the energy of Nashville’s last street lamp. Alert and aware, Thurmond’s speaker inhabits a luscious world filled with gnats, yellowing Timothy, and humid mornings. In a bathrobe, or under a willow tree, Thurmond reminds us how love and loss, earth and loam, reveal the tension between who we are and who we are becoming. We hold these delicate poems in our hands like prayers to a god who is also a bird. We follow Thurmond from Tennessee, to Wyoming, to Spokane, and every bone in the speaker’s body keeps working to teach us what it means to be wonderful and alive. We follow as Thurmond beckons us to consider how we age alongside our dragons, and if our house is actually the one on fire. We are glad to follow Thurmond’s poetry anywhere, because she has traveled the path before us, and we know her empathy and wisdom will light our way.”

–Jan Harris, author of Isolating One’s Priorities in a Time of Crisis

Please share/please repost #flpauthor #preorder #AwesomeCoverArt #poetry #chapbook #read #poems

#poetry#flp authors#preorder#flp#poets on tumblr#american poets#chapbook#chapbooks#finishing line press#small press

1 note

·

View note

Text

nancy drew name meanings

so this is the work i’ve been doing over the past couple days, I want to give you guys a heads up that list will contain spoilers for some of the characters/games so please be aware of all of that. if this garners interest, i’ll do maybe the penvellyn family tree (that thing could not fit in here) or last name origins!

Main Cast

Nancy Drew: Grace (Hebrew)

Bess Marvin: god of plenty (English)

Georgia “George” Fayne: farmer (English)

Edward “Ned” Nickerson: wealth, fortune, prosperous OR guardian, protector (English)

Joe Hardy: god will increase (English)

Frank “Franklin” Hardy: free landowner (English)

SCK/SCKR

Jacob “Jake” Rogers: supplanter (Hebrew)

Daryl Gray: open, from Airelle (English, French)

Connie Watson: strong willed, wise (Irish)

Hal Tanaka: army ruler (English)

Hector “Hulk” Sanchez: holding fast (Greek)

Mitch Dillon: Who is like God, gift from god (Hebrew)

Detective “Steve” Beech: crown, garland (Greek)

STFD

Mattie Jensen: lady, mistress of the house, might in battle (Aramaic or German)

Richard “Rick” Arlen: brave ruler (English)

Dwayne Powers: swarthy (Irish, Gaelic)

Lillian Weiss: lily, a flower (English)

Millie Strathorn: industrious (German)

William Pappas: resolute protector, strong willed warrior (German)

Ralph Guardino: counsel wolf, famous wolf (Norse, English)

MHM

Rose Green: rose, a flower (English)

Abby Sideris: father’s joy (Hebrew)

Charlie Murphy: free man (Charlie)

Louis Chandler: fame, warrior, famous in battle (French)

Hannah Gruen: favor, grace (Hebrew)

Emily Foxworth: rival, wily, persuasive (Latin, Greek)

TRT

Professor Beatrice Hotchkiss: she who makes happy, bringer of joy, blessings (Italian, French, Latin)

Dexter Egan: right handed, fortunate, one who dyes (Latin)

Lisa Ostrum: God’s promise (English, Hebrew)

Jacques Brunais: supplanter (French)

FIN

Brady Armstrong: spirited, broad (Irish)

Joseph Hughes: he will add (Hebrew)

Nicholas Falcone: victory of the people (Greek)

Simone Mueller: god has heard (Hebrew)

Maya Nguyen: good mother (Greek)

Eustacia Andropov: fruitful, productive (Greek)

Sherman Trout: shearer of woolen garments (English)

SSH

Joanna Riggs: god is gracious (Greek/Hebrew)

Alejandro Del Rio: defender of mankind (Spanish)

Taylor Sinclair: tailor (French)

Henrik Van Der Hune: ruler of the home, lord of the house (Swedish, Danish)

Franklin Rose: free landowner (English)

Poppy “Penelope” Dada: weaver (Greek)

Prudence Rutherford: prudence, good judgement (Latin)

DOG

Red Knott: person with red hair (English)

Jeff Akers: pledge of peace (English)

Emily Griffin: rival, persuasive, wily (Latin, Greek)

Sally McDonald: princess (Hebrew)

Vivian Whitmore: lively (Latin)

Mickey Malone: who is like god (Hebrew)

Lucy: as of light (English, French)

Iggy: fiery (Latin)

Vitus: lively (Latin)

Xander: defender of man (Greek)

Yogi: one who performs yoga (Indian, Hindu)

CAR

Harlan Bishop: army land (English)

Ingrid Corey: beloved, beautiful (Norse, German)

Elliot Chen: with strength and right, bravely and truly, boldly and rightly (English, Breton)

Joy Trent: joy, happiness (Latin)

Paula Santos: small (Latin)

K.J Perris: Petros-> the rock (Greek)

Tink Obermeier: love (English)

DDI

Jenna Deblin: white shadow, white wave (English, Welsh)

Katie Firestone: pure (English, Greek)

Andy Jason: manlike, brave (Greek)

Holt Scotto: woods, forest (English)

Casey Porterfield: vigilant, watchful (Irish, Gaelic)

Dr. Irina Predoviciu: peace (Greek)

Hilda Swenson: battle (Norse)

SHA

Dave Gregory: beloved (English)

Tex Britten: from Texas (American)

Mary Yazzie: bitter, beloved, rebelliousness, wished for child, marine, drop of the sea (Aramaic, Hebrew via Latin and Greek)

Shorty Thurmond: a short person (American)

Bet Rawley: god is my oath (Hebrew)

Ed Rawley: wealthy spear, protector, guard, frend (English)

Sheriff Hernandez: son of Hernando (Spanish)

Dirk Valentine: famous ruler (German)

France Humber: free one (French, English)

Meryl Humber: shining sea (English)

CUR

Linda Penvellyn: beautiful, pretty, cute OR clean (Spanish/Portugeuse, Italian)

Mrs. Leticia Drake: joy, gladness (Latin)

Jane Penvellyn: god is gracious/merciful (English)

Nigel Mookerjee: champion (Irish, Gaelic)

Ethel Bossiny: noble (English)

Hugh Penvellyn: mind, spirit (English)

Mrs. Petrov: petros-> rock (Greek to Russian)

CLK

Emily Crandall: rival, wily, persuasive (Latin, Greek)

Jane Willoughby: god is gracious/merciful (English)

Richard Topham: strong in rule (English, French, German, Czech)

Jim Archer: supplanter (English)

Carson Drew: son of marsh dwellers (Scandinavian)

Gloria Crandall: glory, fame, renown, praise, honor (Latin)

Marion Aborn: star of the sea (French)

Mrs Farthingham: a house supplying food (Scottish)

Josiah Crowley: god has healed (Hebrew)

TRN

Lori Girard: bay laurel (English)

Tino Balducci: little, junior (Italian)

Charleena Purcell: free man (German)

John Gray: graced by god (Hebrew)

Jake Hurley: supplanter (Hebrew)

Camille Hurley: helper to the priest (French)

Fatima: captivating, shining one (Arabic)

DAN

Minette: star of the sea, love, will helmet, protection (French)

Heather McKay: evergreen flowering plant (Middle English)

Jing Jing Ling: perfect essence (Chinese)

Dieter von Schwesterkrank: army of the people (German)

Jean-Michel Traquenard: god remits (Hebrew)

Lynn Manrique: pond, lake, pool, waterfall (Welsh)

Hugo Butterly: mind (German)

Zu: knowledgeable and voracious reader (French)

Tammy Barnes (Minette): palm tree (Hebrew)

Noisette Tornade: hazelnut (French)

the n*zi will not be appearing on this list

CRE

Pua Mapu: flower (Hawaiian)

Big Island Mike Mapu: who is like god, gift from god (Hebrew)

Dr. Quigley Kim: descendant of Coigleach or maybe messy hair (Irish)

Dr. Malachi Craven: messenger of god (Hebrew)

ICE

Ollie Randall: olive tree (Latin)

Yanni Volkstaia: god is gracious (Greek)

Bill Kessler: resolute protection (English)

Lou Talbot: renowned warrior (French)

Guadalupe Comillo: river of the wolf (Spanish)

Chantal Moique: stone (French)

Elsa Sibblehoth: pledged to god (German)

Freddie Randall: elf, magical counsel, peaceful ruler (English, German)

Isis: throne (Egyptian)

CRY

Henry Bolet Jr.: house ruler (French)

Dr. Gilbert Buford: bright pledge/promise (French)

Lamont Warrick: the mountain (French)

Renee Amande: reborn, born again (French)

Summer: season, half-year (German)

Bruno Bolet: brown (German)

Bernie: strong and brave bear (German, French)

Iggy: fiery (Latin)

VEN

Colin Baxter: whelp, cub, young creature (Irish, Scottish, Gaelic)

Margherita Faubourg: daisy (Italian)

Helena Berg: light/bright (Greek)

Enrico Tazza: homeowner, king (Italian)

Antonio Fango: priceless one (Spanish, Italian)

Sophia Leporace: wisdom (Greek)

HAU

Kyler Mallory: bowman, archer (Dutch)

Matt Simmons: gift of god (Hebrew)

Kit Foley: bearing Christ (Greek)

Donal Delany: world leader (Scottish)

Alan Payne: precious (German)

Fiona Malloy: white, fair (Gaelic)

RAN - Her Interactive refuses to acknowledge this game and so will I.

WAC

Corine Myers: maiden (American)

Danielle Hayes: god is my judge (Latin)

Mel Corbalis: council protector (English)

Megan Vargas: pearl (Greek)

Izzy Romero: god’s promise (Hebrew)

Leela Yadav: play OR night beauty (Sanskrit or Arabic)

Rachel Hubbard: ewe, one with purity (Hebrew)

Kim Hubbard: of the clearing of the royal fortress (Old English)

Rebecca Sawyer (Nancy): join, tie, snare (Hebrew)

Rita Hallowell: pearl (Spanish)

TOT

Scott Varnell: from Scotland, a Scotsman (old English)

Debbie Kircum: bee (Hebrew)

Tobias “Frosty” Harlow: god is good (Hebrew)

Chase Releford: to hunt (French)

SAW

Shimizu Yumi: reason/cause, beauty; abundant, beauty; evening, fruit; tenderness, beauty (Japanese)

Shimizu Miwako: child of beautiful harmony (Japanese)

Shimizu Kasumi: mist, clear, pure (Japanese)

Nagai Takae: filial piety, obedience and large river (Japanese)

Aihara Rentaro: dependant on kanji used (Japanese)

Savannah Woodham: treeless plain (Spanish)

CAP

Karl Weschler: free man, strong man, man, manly (German)

Anja Mittelmeier: grace (German, Russian)

Lukas Mittelmeier: man from Lucanus (German, Greek, Swedish)

Renate Stoller: Reborn (Latin)

Markus Boehm: dedicated to Mars (Latin)

ASH

Chief McGinnis: son of Angus (Irish)

Deirdre Shannon: broken hearted, sorrowful (Irish, Gaelic)

Brenda Carlton: sword (Norse)

Alexei Markovic: defender (Russian)

Antonia “Toni” Scallari: priceless, praiseworthy, beautiful (Roman)

TMB

Abdullah Bakhoum: servant of Allah (Arabic)

Lily Crewe: lily, a flower

Jamila El-Dine: beauty (Arabic)

Dylan Carter: son of the sea, son of the wave, born from the ocean (Welsh)

Jon Boyle: God is gracious, gift of Jehovah (Hebrew)

DED

Victor Lossett: winner, conqueror (Latin)

Ryan Kilpatrick: descendant of the king, little king (Irish, Gaelic)

Mason Quinto: one who works with stone (English)

Ellie York: shining light (Greek)

Gray Cortright: color, black mixed with white (English)

Niko Jovic: people of victory (Greek, English, Slavic)

GTH

Jessalyn Thornton: he sees (Hebrew)

Clara Thornton: clear, bright, famous (Latin)

Wade Thornton: to go, ford (Anglo-Saxon English)

Harper Thornton: harp, son of the harper (Scottish, Irish, English)

Colton Birchfield: swarthy person, coal town, settlement (Old English)

Charlotte Thornton: free man, petite (French)

Addison Hammond: son of Adam, son of Addi (Old English, Scottish)

SPY

Alec Fell: defender of the people (English)

Bridget Shaw: power, strength, virtue, vigor, noble or exalted one (Gaelic, Irish)

Ewan Macleod: born of the mountain (Scottish, Gaelic)

Moira Chisholm: destiny, share, fate (English)

Kate Drew: pure (English)

Samantha Quick: listens well, as told by god (Aramaic, Hebrew)

MED

Sonny Joon: son (English)

Patrick Dowsett: nobleman, patrician (Latin)

Leena Patel: young palm tree, tender, delicate (Qunaric Arabic)

Kiri Nind: skin, bark, rind (Māori)

Jin Seung: rise, ascent, victory, excel, inherit (Sino-Korean)

LIE

Xenia Doukas: foreigner, outlander, welcomed guest, hospitality (Greek)

Niobe Papadaki: fern (Greek)

Thanos Ganas: immortal (Greek)

Grigor Karakinos: vigilant (Greek)

Melina Rosi: honey, god’s gift (Greek)

SEA

Soren Bergursson: severe (Scandinavian)

Dagny Silva: new day (Old Norse)

Elisabet Grimursdottir: pledged to god (Hebrew)

Magnus Kiljansson: great (Latin)

Gunnar Tonnisson: fighter, soldier, attacker, brave and bold warrior (Nordic)

Burt Eddleton: bright, glorious (Old English)

Alex Trang: man’s defender, warrior (Greek)

MID

Mei Parry: beautiful (Chinese)

Teegan Parry: special thing, little poet (Cornish, Gaelic)

Olivia Ravencraft: olive, olive tree (Latin)

Judge Danforth: hidden ford (Old English) [Last name]

Lauren Corey: laurel tree, sweet of honor, wisdom (English, french)

Alicia Cole: noble natured (Germanic)

Jason Danforth: healer (Greek)

#nancy drew#the formatting is weird but hey it works#frank doesnt have a normal meaning so i used franklin bc some media did use that#anyways enjoy#sck#sckr#stfd#mhm#trt#fin#ssh#dog#car#ddi#sha#cur#clk#trn#dan#cre#ice#cry#ven#hau#ran#wac#tot#saw#cap#ash

35 notes

·

View notes

Link

In the heart of the US Capitol there’s a small men’s room with an uplifting Franklin Delano Roosevelt quotation above the door. Making use of the facilities there after lunch in the nearby House dining room about a year ago, I found myself standing next to Trent Lott. Once a mighty power in the building as Senate Republican leader, he had been forced to resign his post following some imprudently affectionate references to his fellow Republican senator, arch-segregationist Strom Thurmond. Now he was visiting the Capitol as a lucratively employed lobbyist.

The bathroom in which we stood, Lott remarked affably, once served a higher purpose. History had been made there. “When I first came to Washington as a junior staffer in 1968,” he explained, “this was the private hideaway office of Bill Colmer, chairman of the House Rules Committee.” Colmer, a long-serving Mississippi Democrat and Lott’s boss, was an influential figure. The committee he ruled controlled whether bills lived or died, the latter being the customary fate of proposed civil-rights legislation that reached his desk. “On Thursday nights,” Lott continued, “he and members of the leadership from both sides of the House would meet here to smoke cigars, drink cheap bourbon, play gin rummy, and discuss business. There was a chemistry, they understood each other. It was a magical thing.” He sighed wistfully at the memory of a more harmonious age, in which our elders and betters could arrange the nation’s affairs behind closed doors.

I don’t know that Joe Biden, currently leading the polls for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination, ever frequented that particular restroom, in either its bygone or contemporary manifestation, but it could serve as a fitting shrine to all that he stands for. Biden has long served as high priest of the doctrine that our legislative problems derive merely from superficial disagreements, rather than fundamental differences over matters of principle. “I believe that we have to end the divisive partisan politics that is ripping this country apart,” he declared in the Rose Garden in 2015, renouncing a much-anticipated White House run. “It’s mean-spirited. It’s petty. And it’s gone on for much too long. I don’t believe, like some do, that it’s naïve to talk to Republicans. I don’t think we should look on Republicans as our enemies.”

Given his success in early polling, it would seem that this message resonates with many voters, at least when they are talking to pollsters. After all, according to orthodox wisdom, there is no more commendable virtue in American political custom and practice than bipartisanship. Politicians on the stump fervently assure voters that they will strive with every sinew to “work across the aisle” to deliver “commonsense solutions,” and those who express the sentiment eloquently can expect widespread approval. Barack Obama famously launched himself toward the White House with his 2004 speech at the Democratic National Convention proclaiming that there is “not a liberal America and a conservative America,” only a “United States of America.”

By tapping into these popular tropes—“The system is broken,” “Why can’t Congress just get along?”—the practitioners of bipartisanship conveniently gloss over the more evident reality: that the system is under sustained assault by an ideology bent on destroying the remnants of the New Deal to the benefit of a greed-driven oligarchy. It was bipartisan accord, after all, that brought us the permanent war economy, the war on drugs, the mass incarceration of black people, 1990s welfare “reform,” Wall Street deregulation and the consequent $16 trillion in bank bailouts, the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force, and other atrocities too numerous to mention. If the system is indeed broken, it is because interested parties are doing their best to break it.

Rather than admit this, Biden has long found it more profitable to assert that political divisions can be settled by men endowed with statesmanlike vision and goodwill—in other words, men such as himself. His frequent eulogies for public figures have tended to play heavily on this theme. Thus his memorial speech for Republican standard-bearer John McCain dwelled predictably on the cross-party nature of their relationship, beginning with his opening: “My name is Joe Biden. I’m a Democrat, and I loved John McCain.” Continuing in that vein, he related how he and McCain had once been chided by their respective party leaderships for spending so much time in each other’s company on the Senate floor, and referred fondly to the days when senators Teddy Kennedy and James Eastland, the latter a die-hard racist and ruthless suppressor of civil-rights bills, would “fight like hell on civil rights and then go have lunch together, down in the Senate dining room.”

Clearly, there is merit in the ability to craft compromise between opposing viewpoints in order to produce an effective result. John Ritch, formerly a US ambassador and top aide on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, worked closely with Biden for two decades, and has nothing but praise for his negotiating skills. “I’ve never seen anyone better at presiding over a group of politicians who represent conflicting egos and interests and using a combination of conciliation, humor, and muscle to cajole them into an agreed way forward,” Ritch told me recently. “Joe Biden has learned the skills to get things done in Washington. And I’ve seen him apply it equally with foreign leaders.”

The value of compromise, however, depends on what result is produced, and who benefits thereby. McCain’s record had at least a few commendable features, such as his opposition to torture (though never, of course, war). But it is hard to find much admirable in the character of a tireless defender of institutional racism like Strom Thurmond. Hence, Trent Lott’s words of praise—regretting that the old racist had lost when he ran as a Dixiecrat in the 1948 presidential election—had been deemed terminally unacceptable.

It fell to Biden to highlight some redeeming qualities when called on, inevitably, to deliver Thurmond’s eulogy following the latter’s death in 2003 at the age of one hundred. Biden reminisced with affection about the unlikely friendship between the deceased and himself. Despite having arrived at the Senate at age twenty-nine “emboldened, angered, and outraged about the treatment of African Americans in this country,” he said, he nevertheless found common cause on important issues with the late senator from South Carolina, who had been wont to describe civil-rights activists as “red pawns and publicity seekers.”

One such issue, as Branko Marcetic has pitilessly chronicled in Jacobin, was a shared opposition to federally mandated busing in the effort to integrate schools, an opposition Biden predicted would be ultimately adopted by liberal holdouts. “The black community justifiably is jittery,” Biden admitted to the Washington Post in 1975 with regard to his position. “I’ve made it—if not respectable—I’ve made it reasonable for longstanding liberals to begin to raise the questions I’ve been the first to raise in the liberal community here on the [Senate] floor.”

Biden was responding to criticism of legislation he had introduced that effectively barred the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare from compelling communities to bus pupils using federal funds. This amendment was meant to be an alternative to a more extreme proposal put forward by a friend of Biden’s, hall-of-fame racist Jesse Helms (Biden had initially supported Helms’s version). Nevertheless, the Washington Post described Biden’s amendment as “denying the possibility for equal educational opportunities to minority youngsters trapped in ill-equipped inner-city schools.” Edward Brooke of Massachusetts, then the sole African-American senator, called Biden’s measure “the greatest symbolic defeat for civil rights since 1964.”

By the 1980s, Biden had begun to see political gold in the harsh antidrug legislation that had been pioneered by drug warriors such as Nelson Rockefeller and Richard Nixon, and would ultimately lead to the age of mass incarceration for black Americans. One of his Senate staffers at the time recalls him remarking, “Whenever people hear the words ‘drugs’ and ‘crime,’ I want them to think ‘Joe Biden.’” Insisting on anonymity, this former staffer recollected how Biden’s team “had to think up excuses for new hearings on drugs and crime every week—any connection, no matter how remote. He wanted cops at every public meeting—you’d have thought he was running for chief of police.”

The ensuing legislation might also have brought to voters’ minds the name of the venerable Thurmond, Biden’s partner in this effort. Together, the pair sponsored the 1984 Comprehensive Crime Control Act, which, among other repressive measures, abolished parole for federal prisoners and cut the amount of time by which sentences could be reduced for good behavior. The bipartisan duo also joined hands to cheerlead the passage of the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act and its 1988 follow-on, which cumulatively introduced mandatory sentences for drug possession. Biden later took pride in reminding audiences that “through the leadership of Senator Thurmond, and myself, and others,” Congress had passed a law mandating a five-year sentence, with no parole, for anyone caught with a piece of crack cocaine “no bigger than [a] quarter.” That is, they created the infamous disparity in penalties between those caught with powder cocaine (white people) and those carrying crack (black people). Biden also unblushingly cited his and Thurmond’s leading role in enacting laws allowing for the execution of drug dealers convicted of homicide, and expanding the practice of civil asset forfeiture, law enforcement’s plunder of property belonging to people suspected of crimes, even if they are neither charged nor convicted.

Despite pleas from the NAACP and the ACLU, the 1990s brought no relief from Biden’s crime crusade. He vied with the first Bush Administration to introduce ever more draconian laws, including one proposing to expand the number of offenses for which the death penalty would be permitted to fifty-one. Bill Clinton quickly became a reliable ally upon his 1992 election, and Biden encouraged him to “maintain crime as a Democratic initiative” with suitably tough legislation. The ensuing 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, passed with enthusiastic administration pressure, would consign millions of black Americans to a life behind bars.

In subsequent years, as his crime legislation, particularly on mandatory sentences, attracted efforts at reform, Biden began expressing a certain remorse. “I am part of the problem that I have been trying to solve since then, because I think the disparity [between crack and powder cocaine sentences] is way out of line,” he declared at a Senate hearing in 2008. However, there is little indication that his words were matched by actions, especially after he moved to the vice presidency the following year. The executive director of the Criminal Justice Policy Foundation, Eric Sterling, who worked on the original legislation in the House as a congressional counsel, told me, “During the eight years he was vice president, I never saw him take a leadership role in the area of drug policy, never saw him get out in front on the issue like he did on same-sex marriage, for example. Biden could have taken a stronger line [with Obama] privately or publicly, and he did not.”

While many black Americans will neither forgive nor forget how they, along with relatives and friends, were accorded the lifetime stigma of a felony conviction, many other Americans are only now beginning to count the costs of these viciously repressive initiatives. As a result, criminal justice reform has emerged as a popular issue across the political spectrum, including among conservatives eager to burnish otherwise illiberal credentials. Ironically, this has led, in theory, to a modest unraveling of a portion of Biden’s bipartisan crime-fighting legacy.

Last December, as Donald Trump’s erratic regime was falling into increasing disarray, the political-media class briefly united in celebration of an exercise in bipartisanship: the First Step Act. Billed as a long overdue overhaul of the criminal justice system, the legislation received rapturous reviews for its display of cross-party cooperation, headlined by Jared Kushner’s partnership with liberal talk-show host Van Jones. In truth, this was a very modest first step. It offered the possibility of release to some 2,600 federal inmates, whose relief from excessive sentences would require the goodwill of both prosecutors and police, as well as forbidding some especially barbaric practices in federal prisons, such as the shackling of pregnant inmates. Overall, it amounted to little more than a textbook exercise in aisle bridging, a triumph of form over substance.

In the near term, it’s unlikely that there will be further bipartisan attempts to chip away at Biden’s legislative legacy, a legacy that includes an inconsistent (to put it mildly) record on abortion rights. Roe v. Wade “went too far,” he told an interviewer in 1974. “I don’t think that a woman has the sole right to say what should happen to her body.” For some years his votes were consistent with that view. He supported the notorious Hyde Amendment prohibiting any and all federal funding for abortions, and fathered the “Biden Amendment” that banned the use of US foreign aid for abortion research.

As the 1980s wore on, however, and Biden’s presidential ambitions started to swell, he began to cast fewer antiabortion votes (with some exceptions), and led the potent opposition to Judge Robert Bork’s Supreme Court nomination as chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee. Then came Clarence Thomas. Even before Anita Hill reluctantly surfaced with her convincing recollections of unpleasant encounters with the porn-obsessed judge, Biden was fumbling his momentous responsibility of directing the hearings. As Jane Mayer and Jill Abramson report in Strange Justice, their book about the Thomas nomination battle, Biden’s questions were “sometimes so long and convoluted that Thomas would forget what the question was.” Biden prided himself on his legal scholarship, Mayer and Abramson suggest, and thus his questions were often designed “to show off [his] legal acumen rather than to elicit answers.”

More damningly, Biden not only allowed fellow committee members to mount a sustained barrage of vicious attacks on Hill: he wrapped up the hearings without calling at least two potential witnesses who could have convincingly corroborated Hill’s testimony and, by extension, indicated that the nominee had perjured himself on a sustained basis throughout the hearings. As Mayer and Abramson write, “Hill’s reputation was not foremost among the committee’s worries. The Democrats in general, and Biden in particular, appear to have been far more concerned with their own reputations,” and feared a Republican-stoked public backlash if they aired more details of Thomas’s sexual proclivities. Hill was therefore thrown to the wolves, and America was saddled with a Supreme Court justice of limited legal qualifications and extreme right-wing views (which he had taken pains to deny while under oath).

Fifteen years later, Biden would repeat this exercise in hearings on the Supreme Court nomination of Samuel Alito, yet another grim product of the Republican judicial-selection machinery. True to form, in his opening round of questions, Biden droned on for the better part of half an hour, allowing Alito barely five minutes to explain his views. As the torrent of verbiage washed over the hearing room, fellow Democratic Senator Patrick Leahy could only glower at Biden in impotent frustration.

Biden’s record on race and women did him little damage with the voters of Delaware, who regularly returned him to the Senate with comfortable margins. On race, at least, Biden affected to believe that Delawareans’ views might be closer to those of his old buddy Thurmond than those of the “Northeast liberal” he sometimes claimed to be. “You don’t know my state,” he told Fox as he geared up for his first attempt on the White House in 2006. “My state was a slave state. My state is a border state. My state has the eighth-largest black population in the country. My state is anything [but] a Northeast liberal state.” Months later, in front of a largely Republican audience in South Carolina, he joked that the only reason Delaware had fought with the North in the Civil War was “because we couldn’t figure out how to get to the South. There were a couple of states in the way.”

Whether or not most Delawareans are proud of their slaveholding history, there are some causes that they, or at least the dominant power brokers in the state, hold especially dear. Foremost among them is Delaware’s status as a freewheeling tax haven. State laws have made Delaware the domicile of choice for corporations, especially banks, and it competes for business with more notorious entrepôts such as the Cayman Islands. Over half of all US public companies are legally headquartered there.

“It’s a corporate whore state, of course,” the anonymous former Biden staffer remarked to me offhandedly in a recent conversation. He stressed that in “a small state with thirty-five thousand bank employees, apart from all the lawyers and others from the financial industry,” Biden was never going to stray too far from the industry’s priorities. We were discussing bankruptcy, an issue that has highlighted Biden’s fealty to the banks. Unsurprisingly, Biden was long a willing foot soldier in the campaign to emasculate laws allowing debtors relief from loans they cannot repay. As far back as 1978, he helped negotiate a deal rolling back bankruptcy protections for graduates with federal student loans, and in 1984 worked to do the same for borrowers with loans for vocational schools. Even when the ostensible objective lay elsewhere, such as drug-related crime, Biden did not forget his banker friends. Thus the 1990 Crime Control Act, with Biden as chief sponsor, further limited debtors’ ability to take advantage of bankruptcy protections.

These initiatives, however, were only precursors to the finance lobby’s magnum opus: the 2005 Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act. This carefully crafted flail of the poor made it almost impossible for borrowers to get traditional “clean slate” Chapter 7 bankruptcy, under which debt forgiveness enables people to rebuild their lives and businesses. Instead, the law subjected them to the far harsher provisions of Chapter 13, effectively turning borrowers into indentured servants of institutions like the credit card companies headquartered in Delaware. It made its way onto the statute books after a lopsided 74–25 vote (bipartisanship!), with Biden, naturally, voting in favor.

It was, in fact, the second version of the bill. An earlier iteration had passed Congress in 2000 with Biden’s support, but President Clinton refused to sign it at the urging of the first lady, who had been briefed on its iniquities by Elizabeth Warren. A Harvard Law School professor at the time, Warren witheringly summarized Biden’s advocacy of the earlier bill in a 2002 paper:

His energetic work on behalf of the credit card companies has earned him the affection of the banking industry and protected him from any well-funded challengers for his Senate seat.

Furthermore, she added tartly, “This important part of Senator Biden’s legislative work also appears to be missing from his Web site and publicity releases.” No doubt coincidentally, the credit card giant MBNA was Biden’s largest contributor for much of his Senate career, while also employing his son Hunter as an executive and, later, as a well-remunerated consultant.

It should go without saying, then, that Biden was among the ninety senators on one of the fatal (to the rest of us) legislative gifts presented to Wall Street back in the Clinton era: the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act of 1999. The act repealed the hallowed Depression-era Glass–Steagall legislation that severed investment banking from commercial banking, thereby permitting the combined operations to gamble with depositors’ money, and ultimately ushering in the 2008 crash. “The worst vote I ever cast in my entire time in the United States Senate,” admitted Biden in December 2016, as he prepared to leave office. Seventeen years too late, he explained that the act had “allowed banks with deposits to take on risky investments, putting the whole system at risk.”

In the meantime, of course, he had been vice president of the United States for eight years, and thus in a position to address the consequences of his (and his fellow senators’) actions by using his power to press for criminal investigations. His longtime faithful aide, Ted Kaufman, in fact, had taken over his Senate seat and was urging such probes. Yet there is not the slightest sign that Biden used his influence to encourage pursuit of the financial fraudsters. As he opined in a 2018 talk at the Brookings Institution, “I don’t think five hundred billionaires are the reason we’re in trouble. The folks at the top aren’t bad guys.” Characteristically, he described gross inequalities in wealth mainly as a threat to bipartisanship: “This gap is yawning, and it’s having the effect of pulling us apart. You see the politics of it.”

Biden’s rightward bipartisan inclinations are not the only source of his alleged appeal. In an imitation of Hillary Clinton’s tactics in the lead-up to the 2016 election, Biden has advertised himself as the candidate of “experience.” Indeed, in his self-estimation he is the “most qualified person in the country to be president.” It’s a claim mainly rooted in foreign policy, a field where, theoretically, partisan politics are deposited at the water’s edge and Biden’s negotiating talents and expertise are seen to their best advantage.

He boasts the same potent acquaintances with world leaders that helped earn Clinton a similar “most qualified” label on her failed presidential job application and, like her, has been a reliable hawk, not least when occupying the high-profile chairmanship of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. An ardent proponent of NATO expansion into Eastern Europe, an ill-conceived initiative that has served as an enduring provocation of Russian hostility toward the West, Biden voted enthusiastically to authorize Bush’s 2003 invasion of Iraq, was a major proponent of Clinton’s war in Kosovo, and pushed for military intervention in Sudan.

Presumably in deference to this record, Obama entrusted his vice president with a number of foreign policy tasks over the years, beginning with “quarterbacking,” as Biden put it, US relations with Iraq. “Joe will do Iraq,” the president told his foreign policy team a few weeks after being sworn in. “He knows it, he knows the players.” It proved to be an unfortunate choice, at least for Iraqis. In 2006, the US ambassador to Iraq, Zalmay Khalilzad, had selected Nouri al-Maliki, a relatively obscure Shiite politician, to be the country’s prime minister. “Are you serious?” exclaimed a startled Maliki when Khalilzad informed him of the decision. But Maliki proved to be a determinedly sectarian ruler, persecuting the Sunni tribes that had switched sides to aid US forces during the so-called surge of 2007–08. In addition, he sparked widespread allegations of corruption. According to the Iraqi Commission of Integrity set up after his departure, as much as $500 billion was siphoned off from government coffers during Maliki’s eight years in power.

In the 2010 parliamentary elections, one of Maliki’s rivals, boasting a nonsectarian base of support, won the most seats, though not a majority. According to present and former Iraqi officials, Biden’s emissaries pressed hard to assemble a coalition that would reinstall Maliki as prime minister. “It was clear they were not interested in anyone else,” one Iraqi diplomat told me. “Biden himself was very scrappy—he wouldn’t listen to argument.” The consequences were, in the official’s words, “disastrous.” In keeping with the general corruption of his regime, Maliki allowed the country’s security forces to deteriorate. Command of an army division could be purchased for $2 million, whereupon the buyer might recoup his investment with exactions from the civilian population. Therefore, when the Islamic State erupted out of Syria and moved against major Iraqi cities, there were no effective defenses. With Islamic State fighters an hour’s drive from Baghdad, the United States belatedly rushed to push Maliki aside and install a more competent leader, the Shiite politician and former government minister Haider al-Abadi. (Biden’s camp disputed the Iraqi official’s assertion that the United States pressed for Maliki in 2010. “We had no brief for any individual,” said Tony Blinken, who served as Biden’s national security adviser at the time.)

Biden devotes considerable space to this episode in Promise Me, Dad, his political and personal memoir documenting the year in which his son Beau slowly succumbed to cancer. But although we learn much about Biden’s relationship with Abadi, and the key role he played in getting vital help to the beleaguered Iraqi regime, there is little indication of his past with Maliki aside from a glancing reference to “stubbornly sectarian policies.”

Promise Me, Dad also covers Biden’s involvement in the other countries allotted to him by President Obama: Ukraine, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. Anyone seeking insight from the book into the recent history of these regions, or of actual US policy and actions there, should look elsewhere. He has little to say, for example, about the well-chronicled involvement of US officials in the overthrow of Ukraine’s elected government in 2014, still less on whether he himself was involved. He records his strenuous efforts to funnel IMF loans to the country following anti-corruption measures introduced by the government without noting that much of the IMF money was almost immediately stolen and spirited out of Ukraine by an oligarch close to the government. Nor, for that matter, do we learn anything about his son Hunter’s involvement in that nation’s business affairs via his position on the board of Burisma, a natural gas company owned by a former Ukrainian ecology minister accused by the UK government of stealing at least $23 million of Ukrainian taxpayers’ money.

Biden’s recollections of his involvement in Central American affairs are no more forthright, and no more insightful. There is no mention of the 2009 coup in Honduras, endorsed and supported by the United States, that displaced the elected president, Manuel Zelaya, nor of that country’s subsequent descent into the rule of a corrupt oligarchy accused of ties to drug traffickers. He has nothing but warm words for Juan Orlando Hernández, the current president, who financed his 2013 election campaign with $90 million stolen from the Honduran health service and more recently defied his country’s constitution by running for a second term. Instead, we read much about Biden’s shepherding of the Hernández regime, along with its Central American neighbors El Salvador and Guatemala, into the Alliance for Prosperity, an agreement in which the signatories pledged to improve education, health care, women’s rights, justice systems, etc., in exchange for hundreds of millions of dollars in US aid. In the words of Professor Dana Frank of UC Santa Cruz, the alliance “supports the very economic sectors that are actively destroying the Honduran economy and environment, like mega-dams, mining, tourism, and African palms,” reducing most of the population to poverty and spurring them to seek something better north of the border. The net result has been a tide of refugees fleeing north, most famously exemplified by the “caravan” used by Donald Trump to galvanize support prior to November’s congressional elections.

Biden’s claims of experience on the world stage, therefore, cannot be denied. True, the experience has been routinely disastrous for those on the receiving end, but on the other hand, that is a common fate for those subjected, under any administration, to the operations of our foreign policy apparatus.

Given Biden’s all too evident shortcomings in the fields of domestic and foreign policy, defenders inevitably retreat to the “electability” argument, which contends that he is the only Democrat on the horizon capable of beating Trump—a view that Biden, naturally, endorses. Specifically, this notion rests on the belief that Biden has unequaled appeal among the white working-class voters that many Democrats are eager to court.

To be fair, Biden has earned high ratings from the AFL-CIO thanks to his support for matters such as union organizing rights and a higher minimum wage. On the other hand, he also supported NAFTA in 1994 and permanent normal trade relations with China in 2000, two votes that sounded the death knell for America’s manufacturing economy. Regardless of how justified his pro-labor reputation may be, however, it’s far from clear that the working class holds Biden in any special regard—his two presidential races imploded before any blue-collar workers had a chance to vote for him.

It is this fact that makes the electability argument so puzzling. Biden’s initial bid for the prize in 1988 famously blew up when rivals unkindly publicized his plagiarism of a stump speech given by Neil Kinnock, a British Labour Party politician. (In Britain, Kinnock was known as “the Welsh Windbag,” which may have encouraged the logorrheic Biden to feel a kinship.) Biden partisans pointed out that he had cited Kinnock on previous occasions, though he didn’t always remember to do so. Either way, it was a bizarre snafu. It also emerged that Biden had been incorporating chunks of speeches from both Bobby and Jack Kennedy along with Hubert Humphrey in his remarks without attribution (although reportedly some of this was the work of speechwriter Pat Caddell).

Another gaffe helped upend Biden’s second White House bid, in 2007, when he referred to Barack Obama in patronizing terms as “the first mainstream African American who is articulate and bright and clean and a nice-looking guy.” The campaign cratered at the very first hurdle, the Iowa caucuses, where Biden came in fifth, with less than 1 percent of the votes. “It was humiliating,” recalled the ex-staffer. (The “gaffes” seem to take physical form on occasion. “He has a bit of a Me Too problem,” a leading female Democratic activist and fund-raiser told me, referring to his overly tactile approach to interacting with women. “We never had a talk when he wasn’t stroking my back.” He has already faced heckling on the topic, and videos of this behavior during the course of public events and photo ops have been widely circulated.)

Further to the issue of Biden’s assurances that he is the man to beat Trump is the awkward fact that, as the former staffer told me, “he lacks the discipline to build the nuts and bolts of a modern presidential campaign.” Biden “hated having to take orders from [David] Axelrod and the other Obama people as a vice-presidential candidate in 2008. Campaign aides used to say to him, ‘I’ve got three words for you: Air Force Two.’” My informant stressed that Biden “sucks at fund-raising. He never had to try very hard in Delaware. Staff would do it for him.” Certainly, Biden’s current campaign funds would appear to confirm this contention. His PAC, American Possibilities, had raised only two and a half million dollars by the end of 2018, a surprisingly insignificant amount for a veteran senator and two-term vice president. Furthermore, although the PAC’s stated purpose is to “support candidates who believe in American possibilities,” less than a quarter of the money had found its way to Democratic candidates in time for the November midterms, encouraging speculation that Biden is not really that serious about the essential brass tacks of a presidential campaign—which would include building a strong base of support among Democratic officeholders.

Other organizations in the Biden universe behave similarly, expending much of their income on staff salaries and little on their ostensible function. According to an exhaustive New York Times investigation, salaries accounted for 45 percent of spending by the Beau Biden Foundation for the Protection of Children in 2016 and 2017. Similarly, three quarters of the money the Biden Cancer Initiative spent in 2017 went toward salaries and other compensation, including over half a million dollars for its president, Greg Simon, formerly the executive director of Biden’s Cancer Moonshot Task Force during the Obama Administration. Outside the inner circle of senior aides, there does not appear to be an extended Biden network among political professionals standing ready to raise money and perform other tasks necessary to a White House bid, in the way that Hillary Clinton had a network across the political world composed of people who had worked for her and her husband. “Biden doesn’t have that,” his former staffer told me, “because he’s indifferent to staff.” It’s a sentiment that’s been expressed to me by many in the election industry, including a veteran Democratic campaign strategist. “Everyone else is getting everything set up to go once the trigger is pulled,” this individual told me recently. “I myself have firm offers from the [Kamala] Harris and [Cory] Booker campaigns. The Biden people talked to me too, but they could only say, ‘If we run, we’d love to bring you into the fold.’”

At the start of the new year, Biden must have been living in the best of all possible worlds. As he engaged in well-publicized ruminations on whether or not to run, he was enjoying a high profile, with commensurate benefits of sizable book sales and hundred-thousand-dollar speaking engagements. Even more importantly, Biden found himself relevant again. “You’re either on the way up,” he likes to say, “or you’re on the way down,” which is why the temptation to reject the lessons of his two hopelessly bungled White House campaigns has been so overwhelming. Regardless of the current election cycle’s endgame, though, it’s safe to assume that his undimmed ego will never permit any reflection on whether voters who have been eagerly voting for change will ever really settle for Uncle Joe, champion of yesterday’s sordid compromises.

47 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Link

OLD NUMB NUTS IS LYIN' THRU HIS TEETH, BUT WHAT ELSE IS NEW...

BACKFIREALLEY.COM-NEW EDITION EVERY SUNDAY!!! MYSTIC, ANCIENT WISDOM, COMMON SENSE, OPINIONS & POLITICS... http://backfirealley.com/news/dads451-500/483-Brother-By-Another-Mother.html RIPLEY'S BELIEVE IT OR NOT... NEW EDITION EVERY DAY!!!... facebook.com/joelamastus FREE COUPONS-GROCERIES-ELECTRONICS!... tinyurl.com/y39u22ca PINTEREST pinterest.com/BackfireAlley/the-war-of-the-nexs/ TWITTER twitter.com/Backfirealley

0 notes

Photo

Excited to be back online with my 2021 Leadership Dekalb Classmates for our Government Day. Honored to hear wisdom from Dekalb CEO Michael Thurmond... .. .. @AppLetstag #entrepreneur #entrepreneurship #leadershipdekalb2021 #rushmanmoorereg #goals #lifestyle #leader #wehunting #faith #wealth #commercialrealestate #tenantrep #businessbroker #REAP #10x #growth #mindset #milliondollarclub #branding #inspiration #marketing #commercial #realestate #broker #kingsofatlantabuilding #atlanta #decatur #downtown #buckhead #blackwealth (at Atlanta, Georgia) https://www.instagram.com/p/CKmAt72h89S/?igshid=wz7algntxln1

#entrepreneur#entrepreneurship#leadershipdekalb2021#rushmanmoorereg#goals#lifestyle#leader#wehunting#faith#wealth#commercialrealestate#tenantrep#businessbroker#reap#10x#growth#mindset#milliondollarclub#branding#inspiration#marketing#commercial#realestate#broker#kingsofatlantabuilding#atlanta#decatur#downtown#buckhead#blackwealth

0 notes

Text

Why Amnesty Remains America’s Best Immigration Policy

In 1986, President Ronald Reagan signed legislation granting amnesty to millions of immigrants while Strom Thurmond, George Bush, and Alan Simpson—among others—looked on. Courtesy of the Associated Press.

by Joe Mathews | October 29, 2018

One afternoon in July 1985, President Ronald Reagan met with his domestic policy council in the White House cabinet room. The question: should he keep pushing legislation to offer amnesty to undocumented migrants?

Some Reagan aides wanted him to drop his support for amnesty, the term for granting legal status to people in the country illegally. Reagan’s pollsters had told him that the public opposed amnesty. And the president’s championing of amnesty had produced defeats. Reagan’s first bill to legalize immigrants failed in Congress in 1982. In 1984, Reagan had convinced the House and Senate to pass a bill, only to see the legislation fall apart in conference committee.

But amnesty had one stalwart supporter in the room: Reagan himself.

Recently, at Reagan’s presidential library in Simi Valley, I read through the records on the legislation that became the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act. Today, IRCA doesn’t get much respect; it’s long been dismissed across the political spectrum as “the failed amnesty law.” Its central idea, of broad forgiveness and quick legal status for undocumented immigrants, is completely out of political fashion today.

But while studying the records, I was struck by the difference between the reality of the 1986 amnesty and its 2018 reputation. The 1986 law was carefully conceived, realistic, and humane—reflecting the practical wisdom of a California president.

The records show that Reagan, despite his reputation for avoiding details, was personally engaged on immigration. When aides talked about the supposed peril to public safety of immigrants, Reagan shifted the conversation to specific stories of undocumented immigrants in California who suffered because of their lesser legal status. “The president cited past cases of exploitation of illegal aliens,” according to the minutes of that 1985 meeting.

Reagan ended the meeting by saying he wanted to talk more with the legislation’s co-sponsor, a Republican U.S. senator from Wyoming named Alan K. Simpson. In those conversations, Reagan and Simpson determined to go forward with the legislation, for two big reasons.

First, they saw legalization as essential to protecting and integrating immigrants. “The work to be done is to avoid seeing this nation populated with a furtive illegal subclass of human beings who are afraid to go to the cops, afraid to go to a hospital…or afraid to go to their employer,” Simpson wrote Reagan in a private note that began, “Dear Ron.”

Second, and more important, both men were old enough to have seen immigrants used as scapegoats; they urgently wanted legislation to preempt divisive politics. “If we do not choose to have immigration reform in the near future, the alternative will not just be the status quo,” said Simpson while reintroducing the legislation in 1986. “No, the alternative instead will be an increased public intolerance—a failure of compassion, if you will—toward all forms of immigration and types of entrants—legal and illegal; refugees, permanent resident aliens, family members and all others within our borders.”

The bill did pass, and it forestalled Simpson’s nightmare—but only for a while.

Immigration restrictionists blame the 1986 law for today’s bitter conflicts over immigration. But they have it backward. Today’s immigration problems result not from amnesty but from our collective failure to understand what made the 1986 law successful.

IRCA actually had two big pieces. One—the successful piece—was amnesty, which was limited, fatefully, to immigrants who had been continuously in the U.S. since January 1, 1982. But the bill’s other big piece drew more attention and was more influential in turning immigration into an American quagmire: a new enforcement regime that prohibited hiring and employing the undocumented.

Familiar figures from today’s politics show up in the records in ways rich with irony. President Trump’s National Security Advisor, John Bolton, Trump legal spokesman Rudolph Giuliani, and Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts—all then in Reagan’s employ—worked on amnesty’s behalf. The politics around this new enforcement were scrambled and did not break down along party lines. Many Democrats opposed the bill, with some arguing that hiring restrictions would lead to discrimination against all Latinos. Labor unions worried that the bill would be too lenient on employers, particularly in agriculture, while some Republicans opposed it because it might be too tough on businesses.

Compromises pulled the bill to passage. To reassure those worried about employment discrimination, an amendment prohibited, for the very first time, employment discrimination on the basis of national origin. And, crucially, California’s own U.S. Senator Pete Wilson—who as governor in the 1990s would embrace anti-immigrant politics—helped lead negotiations that led to the creation of a special legalization category for agricultural workers.

The 1986 law was carefully conceived, realistic, and humane—reflecting the practical wisdom of a California president.

IRCA should have been celebrated as a tremendous legislative victory. But the bill’s passage was overshadowed by news of the explosion of the Space Shuttle Challenger. Reagan didn’t sign the bill until after the November 1986 election, in a small ceremony subdued by the fact that Republicans had lost control of the U.S. Senate. Reporters in attendance asked about the Iran-Contra scandal, not immigration.

But in his remarks that day, Reagan unabashedly emphasized the benefits of the bill for the undocumented. “The legalization provisions in this Act will go far to improve the lives of a class of individuals who now must hide in the shadows, without access to many of the benefits of a free and open society,” he said. “Very soon many of these men and women will be able to step into the sunlight and ultimately, if they choose, they may become Americans.”

Under the two-step amnesty process, more than 3 million people applied for temporary residency, which lasted 18 months, in the first phase. In the second phase, 2.7 million people received permanent residency as a result of the law. This was the largest legalization in the country’s history, but it should have been larger. An estimated 2 million people did not legalize their status.

Why not? The law was not generous enough. It excluded newer immigrants who had come between 1982 and the law’s 1987 implementation. Some undocumented immigrants feared making themselves known, while others didn’t know about the program, because publicity and outreach came late in the window for legalization. Some were discouraged by the federal government’s bureaucratic and time-consuming legalization process of security checks, document checks, and requirements for competency in English and American civics.

In retrospect, the process should have covered all undocumented immigrants and should have established a regular amnesty process every few years, since the demand for immigrant labor was certain to keep attracting people to the country. But in many ways, amnesty was a government success story—it gave millions of people the legal status they required to have a better life. It even turned a $100 million profit for the government through the $185 fees it charged applicants.

But amnesty’s successes didn’t stop immigration restrictionists from criticizing the law and scapegoating immigrants, especially after the economy went south in the early 1990s. The main attack on the law continues to this day: Amnesty encouraged more undocumented immigrants to come, critics say. In fact, the opposite is true. Studies show that amnesty produced a small decline in the number of illegal entries into the country.