#They stopped calling it the LEM in 1965

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

People constantly referring to the Lunar Module as "the LEM" is setting off my space OCD in ways I didn't think was possible.

#Space#Spaceflight#Nasa#Apollo#Lunar Module#Moon landings#They stopped calling it the LEM in 1965#I blame the guy who did the subtitles for the apollo 13 DVD

0 notes

Text

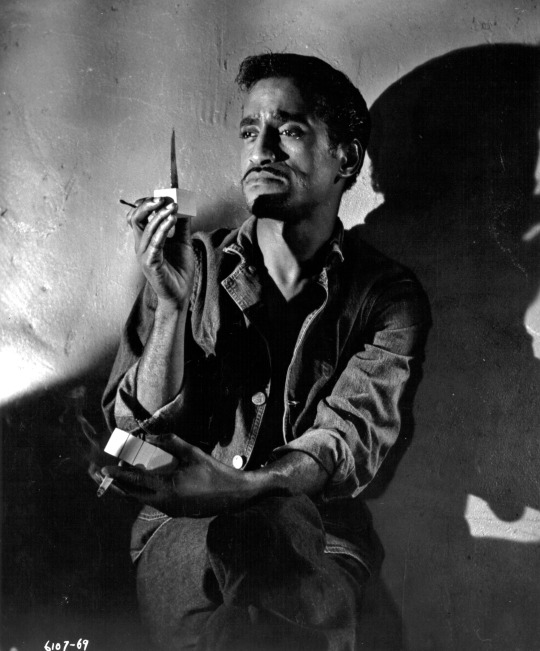

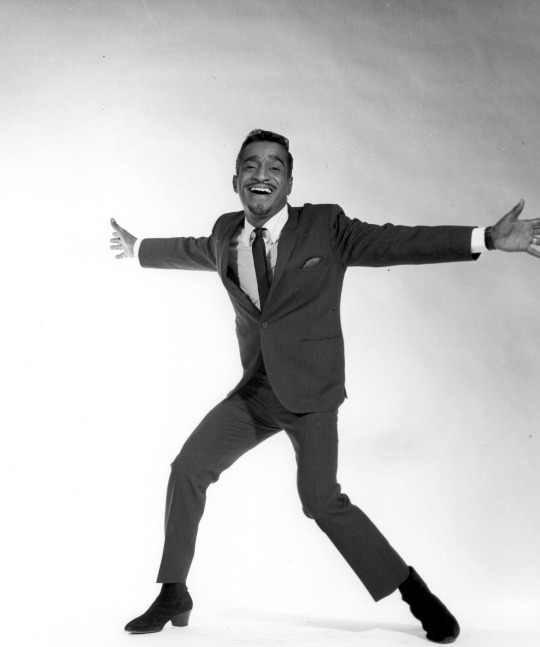

Sammy Davis Jr.: Civil Rights Activist and Natural Born Entertainer By Susan King

Sammy Davis Jr. was an exceptional talent. He could sing (you’ll get chills up your spine listening to his recording of “I Gotta Be Me”), dance, act and lest we forget, he was a member of the Rat Pack. He and Harry Belafonte made history in 1956 when they became the first African Americans to earn Emmy nominations.

But most people forget Davis was also very involved in the fight for civil rights in the 1950s and ‘60s. In January 1961, he joined Rat Packers Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin, as well as Harry Belafonte, Mahalia Jackson and Tony Bennett, for the Carnegie Hall benefit concert Tribute to Martin Luther King. He also performed at the Freedom Rally in Los Angeles that year and at the March on Montgomery in 1965.

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. even wrote Davis a thank you note: “Not very long ago, it was customary for Negro artists to hold themselves aloof from the struggle for equality… Today, greats like Harry Belafonte, Sidney Poitier, Mahalia Jackson and yourself, of course, are not content to merely identify with the struggle. They actively participate in it, as artists and as citizens, adding the weight of their enormous prestige and thus helping to move the struggle forward.”

In 1968, Davis received the prestigious Spingarn Medal from the NAACP for his 1965 autobiography Yes, I Can. Nevertheless, considering his work for the late Dr. King, Davis shocked the world in 1972 when he supported Richard Nixon, who had a poor track record when it came to civil rights and would refer to African Americans in derogatory terms behind closed doors. But there was Davis, attending the opening night of the Republican convention in Miami Beach and then performing a concert for Republican youth. And it was during the concert that he hugged Nixon.

The backlash in the African American community was loud and strong. Wil Haywood stated in his biography In Black and White: The Life of Sammy Davis, Jr., “Sammy failed to understand Blacks’ distrust of Nixon’s ultraconservative views. The hug at the Republican National Convention, in the glare of the nation’s spotlight, seemed too to minstrelsy.“

Davis later said: “By their definition I had let them down. In their minds there were certain things I could do, certain rules I could break. I married a white woman and I hardly got any heat. But by going with a Republican president I had broken faith with my people.”

In a 1976 Ebony interview, Davis reflected that working with Nixon was not a betrayal to African Americans but a way to help Black citizens. “When my wife, Altovise, and I were invited to the White House after the November elections, I repeated [my recommendations],” he noted. “We started to rap, and he asks, ‘What can I do?’ Come on Sam, tell me what I can do.’ So, I laid it down again.”

He told Nixon that the funds cut from anti-poverty programs needed to be reinstated and that Martin Luther King’s birthday should be made a national holiday. But he soon realized Nixon wasn’t listening to him. He regretted supporting Nixon.

Davis was born in Harlem on December 8, 1925 to vaudevillians Sammy Davis Sr. and Elvera Sanchez, who was of Afro-Cuban descent. The couple separated in 1928, and Sammy Jr. lived with his father and his grandmother, Mama. He was just three when he joined the Will Mastin Trio with his father and Mastin. Davis never went to school. In a 2014 Los Angeles Times interview, his daughter Tracey Davis recalled her father telling her, “What have I got? No looks, no money, no education. Just talent.”

As a youngster, he appeared in short films, including Rufus Jones for President (’33). He toured with the Mastin Trio until he was drafted into the Army during World War II, where he suffered so much abuse from white soldiers that his nose was broken three times. “How did he make it and so many others not make it?,” Tracey Davis reflected. “He had talent. But what he went through would have killed a lot of people or make them bitter or just messed with your life so bad you couldn’t get over it.”

In 1954, Davis survived a car crash on his way home to Los Angeles after performing in Vegas. He lost an eye. He wore an eye-patch for six months and then was fitted with a glass eye. Two years later, he opened on Broadway in the musical Mr. Wonderful.

It was announced in August 2020 that a film is in pre-production about the ill-fated relationship in 1957 between Davis and Kim Novak. The relationship was quashed, as it would have killed Novak’s career and supposedly, it quite literally would have killed Davis – a hit was allegedly put out on his life. To keep the heat off of him, Davis was briefly married in 1958 to dancer Loray White.

In 1960, Davis married striking Swedish actress Mai Britt. According to Tracey Davis, her mother, who had appeared THE YOUNG LIONS (‘58) and THE BLUE ANGEL (‘59), was dropped by 20th Century-Fox because of her marriage. Tracey said her parents “didn’t regret being together. My mom loved my dad like crazy and my dad loved my mother. My mother was so lucky because her parents didn’t care.” Though they divorced in 1968, she said they never fell out of love. Before his death of cancer in 1990 at the age of 64, Davis told his daughter why they broke up: “I just couldn’t be what she wanted me to be. A family man. My performance schedule was rigorous.”

Tracey said that her dad and Sinatra were great friends offstage. “He was like a good cushion for dad.” And, if Davis ran into trouble due to his race, Sinatra was there to fight the good fight for his friend. “He’d say, ‘Oh, Sammy can’t come in here? Then I’m not coming in.’ I think it gave my dad such comfort knowing he had this big brother out there that would go to the mat for him.” Davis, who was a chain smoker and was rarely seen without a glass of vermouth, had a falling out with Sinatra in the early 1970s, because the performer was using drugs. “Frank was mad he was squandering himself, doing stupid things. He let dad know about it and dad was kind of well, I don’t care.’’ Eventually, Davis did care and apologized to the Chairman of the Board.

Being a member of the Rat Pack gave Davis a certain visibility, especially in the films they made together, including OCEAN’S 11 (‘60) and ROBIN AND THE 7 HOODS (‘64), but all of the actors were just having a good time on screen. These vehicles didn’t show Davis’s strength as a dramatic actor. But occasionally, he got the opportunity, such as in ANNA LUCASTA (‘58) opposite Eartha Kitt, CONVICTS 4 (‘62) and A MAN CALLED ADAM (‘66). And in 1964, he returned to the Broadway stage in the Charles Strouse-Lee Adams musical Golden Boy, for which he earned a Tony nomination.

“He was very representative of a time and place,” said Strouse in a 2003 L.A. Times interview. “He was created from a lot of forces, like the Earth coming in and ‘whoop,’ here comes Sammy Davis. He was brilliant along with everything else. He was the biggest star of the day and in the theater, he had no peer. We sold out all the time.”

But Davis also missed a lot of performances of Golden Boy. “He got himself very tired or perhaps depressed or nervous,” reflected Stouse, adding that Davis stretched himself thin “the way lemmings go to the edge of the cliff and then they go off. He didn’t go off, but he was always on the end of the cliff. He was very driven and yet very mild-mannered and almost submissive to Sinatra. He had to be loved. He wouldn’t get off the stage.”

As he got older, Davis stopped wearing flashy clothes and jewelry and got back to basics as a singer and performer. And, he is the best thing about his last film, TAP (‘89), with Gregory Hines. Their tap dance will make your heart beat a bit faster. Tracey Davis said though her father was “incredibly driven,” he had a “huge heart, a zest for life. He had more energy than anyone I had known.”

#Sammy Davis Jr#old hollywood#Rat Pack#1950s#civil rights#Black performers#Black actors#Eartha Kitt#Martin Luther King#politics#TCM#Summer Under the Stars#Turner Classic Movies#Susan King

232 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gale Sayers

Gale Eugene Sayers (born May 30, 1943), nicknamed the Kansas Comet, is a former professional American football player who earned acclaim both as a halfback and return specialist in the National Football League (NFL). In a brief but highly productive NFL career, Sayers spent seven seasons with the Chicago Bears from 1965 to 1971, though multiple injuries effectively limited him to five seasons of play. He was known for his elusiveness and agility, and was regarded by his peers as one of the most difficult players to tackle.

Prior to joining the Bears, Sayers played college football for the Kansas Jayhawks football team of the University of Kansas, where he compiled 4,020 all-purpose yards over three seasons and was twice recognized as a consensus All-American. In his rookie NFL season, he set a league record by scoring 22 total touchdowns and gained 2,272 all-purpose yards en route to being recognized as the NFL's Rookie of the Year. He continued this production through his first five seasons, earning four Pro Bowl appearances and five first-team All-Pro selections. A right knee injury forced Sayers to miss the final five games of the 1968 season, but he returned in 1969 to lead the NFL in rushing yards and be named the NFL Comeback Player of the Year. An injury to his left knee in the 1970 preseason kept him sidelined for most of his final two seasons.

His friendship with Bears teammate Brian Piccolo, who died of cancer in 1970, inspired Sayers to write his autobiography, I Am Third, which in turn was the basis for the 1971 made-for-TV movie Brian's Song. Sayers was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1977 and, aged 34, remains the youngest person to receive the honor. For his achievements in college, he was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame the same year. His jersey number is retired by both the Bears and the University of Kansas. Following his NFL career, Sayers began a career in sports administration and business, and served as the athletic director of Southern Illinois University from 1976 to 1981.

Early years

Born in Wichita, Kansas, but raised in Omaha, Nebraska, Gale Eugene Sayers is the son of Roger Winfield Sayers and Bernice Ross. His father was a mechanic for Goodyear, farmed, and worked for auto dealerships. Sayers' younger brother, Ron, later played running back for the San Diego Chargers of the American Football League. Roger, his older brother, was a decorated college track and field athlete. Gale Sayers graduated from Omaha Central High School where he starred in football and track and field. A fine all-around track athlete, he set a state long jump record of 24'10 1⁄2" as a senior in 1961.

College career

Sayers was recruited by several major Midwestern colleges before deciding to play college football at the University of Kansas. While being interviewed by Len Kasper and Bob Brenly during a broadcast of a Chicago Cubs game on September 8, 2010, Sayers said he had originally intended to go to the University of Iowa. Sayers said that he decided against going to Iowa after the Iowa head coach, Jerry Burns, did not have time to meet Sayers during his one campus visit. During his Jayhawks career, he rushed for 2,675 yards and gained a Big Eight Conference-record 4,020 all-purpose yards. He was three times recognized as a first-team All-Big Eight selection and was a consensus pick for the College Football All-America Team in both 1963 and 1964.

As a sophomore in 1962, his first year on the varsity team, Sayers led the Big Eight Conference and was third in the nation with 1,125 rushing yards. His 7.1 yards-per-carry average was the highest of any player in the NCAA that season. Against Oklahoma State that season, he carried 21 times for a conference single-game-record 283 yards to lead Kansas to a 36–17 comeback victory. In 1963, Sayers set an NCAA Division I FBS record with a 99-yard run against Nebraska. He finished the year with 917 rushing yards, again leading all rushers in the Big Eight. He earned first-team All-America recognition from the American Football Coaches Association (AFCA), the Football Writers Association of America (FWAA), the Newspaper Enterprise Association (NEA), The Sporting News, and United Press International (UPI), among others. In 1964, his senior year, he led the Jayhawks to a 15–14 upset victory over Oklahoma with a 93-yard return of the game's opening kickoff for a touchdown. He finished the year with 633 rushing yards, third most among Big Eight rushers, and also caught 17 passes for 178 yards, returned 15 punts for 138 yards, and returned seven kickoffs for 193 yards. He earned first-team All-America honors from each of the same selectors as in the previous year, in addition to the Associated Press (AP), among others.

Professional career

1965: Rookie season

Sayers was drafted by the Chicago Bears in the first round, fourth overall, in the 1965 NFL Draft, and was also picked fifth overall by the Kansas City Chiefs of the American Football League in the AFL draft. He decided that all things being equal, he would rather play in Chicago, and so after consulting his wife he chose to sign with George Halas's Bears. In his rookie year, he scored an NFL-record 22 touchdowns: 14 rushing, six receiving, and one each on punt and kickoff returns. He gained 2,272 all-purpose yards, a record for an NFL rookie, with 1,371 of them coming from scrimmage. Sayers averaged 5.2 yards per rush and 17.5 yards per reception. His return averages were 14.9 yards per punt return and a league-high 31.4 yards per kickoff return.

Against the Minnesota Vikings on October 17, Sayers carried 13 times for 64 yards and a touchdown; caught four passes for 63 yards and two touchdowns; and had a 98-yard kickoff return touchdown in the 45–37 Bears victory. He was the last NFL player to score a rushing, receiving, and kickoff return touchdown in the same game until Tyreek Hill accomplished the feat over fifty years later, in 2016. Bears coach Halas lauded Sayers after the game, saying, "I don't ever remember seeing a rookie back who was as good," and deemed his talents equal to former Bears greats Red Grange and George McAfee. "And remember," said Halas, "we used to call George 'One-Play McAfee'." On December 12, he tied Ernie Nevers' and Dub Jones' record for touchdowns in a single game, scoring six in a 61–20 victory over the San Francisco 49ers that was played in muddy conditions at the Chicago Cubs' Wrigley Field. Sayers was the consensus choice for NFL Rookie of the Year honors from the AP, UPI, and NEA.

1966: First rushing title

In his second season, Sayers led the league in rushing with 1,231 yards, averaging 5.4 yards per carry with eight touchdowns and becoming the first halfback to win the rushing title since 1949. He also led the Bears in receiving with 34 catches, 447 yards, and two more touchdowns. He surpassed his rookie season's kick return numbers, averaging 31.2 yards per return with two touchdowns. He also supplanted his all-purpose yards total from the previous season, gaining 2,440 to set the NFL record. The first of his kickoff return touchdowns that season came against the Los Angeles Rams, as he followed a wedge of blockers en route to a 93-yard score. In the Bears' final game of the season and the first of Sayers' pro career with his parents in attendance, against the Minnesota Vikings, he carried 17 times for a franchise-record 197 yards after returning the opening kickoff 90 yards for a touchdown. Sayers was named to All-Pro first teams by the AP, UPI, the NEA, The Sporting News, and the Pro Football Writers Association, among others. Starring in his second straight Pro Bowl, Sayers carried 11 times for 110 yards and was named the back of the game. The Bears finished the season with a 5–7–2 record, and the Chicago Tribune tabbed Sayers as "the one bright spot in Chicago's pro football year."

1967: Shared workload

In Halas's final season as an NFL coach, Sayers again starred. Sharing more of the rushing duties with other backs, such as Brian Piccolo, Sayers gained 880 yards with a 4.7-yard average per carry. His receptions were down as well. He had three kickoff returns for touchdowns on 16 returns, averaging 37.7 yards per return. Only rarely returning punts (he returned three all season), Sayers still managed to return one for a score against the San Francisco 49ers, a game in which he also returned the opening kickoff 97 yards for a touchdown and scored a rushing touchdown on a rain-soaked field in San Francisco's Kezar Stadium. "It was a bad field, but it didn't stop some people," said 49ers coach Jack Christiansen, referring to Sayers' performance. Christiansen said that after Sayers' kickoff return, all punts were supposed to go out of bounds. But Sayers received the punt and ran 58 yards through the middle of the field for the score. In a November game against the Lions, a cutback by Sayers caused future hall of fame cornerback Lem Barney to fall over, after which Sayers sprinted for a 63-yard gain. Later in the game he returned a kickoff 97 yards for a touchdown. After the season, Sayers was invited to his third straight Pro Bowl, in which he returned a kickoff 75 yards and scored a three-yard rushing touchdown and again earned player of the game honors. Chicago finished in second place in the newly organized Central Division with a 7–6–1 record.

1968–1969: Right knee injury and comeback season

Sayers had the most productive rushing yardage game of his career on November 3, 1968, against the Green Bay Packers, during which he carried 24 times for 205 yards. His season ended prematurely the following week against the 49ers when he tore the ligaments in his right knee. Garry Lyle, the teammate nearest Sayers at the time, said, "I saw his eyes sort of glass over. I heard him holler. I knew he was hurt." Sayers had again been leading the league in rushing yards through the first nine games, and finished the year with 856 yards. After surgery, Sayers went through a physical rehabilitation program with the help of Piccolo, who had replaced him in the starting lineup. Despite missing the Bears' final five games, he earned first-team All-Pro recognition from several media outlets, including the AP, and UPI, and NEA.

In the 1969 season, after a slow start and despite diminished speed and acceleration, Sayers led the league in rushing once again with 1,032 yards. He averaged 4.4 yards per carry and was the only player to gain over 1,000 rushing yards that year. He moved into second place on the Bears' all-time rushing yards list, passing Bronko Nagurski. Sayers was recognized as the NFL's Comeback Player of the Year by United Press International. The Bears, long past the Halas glory years, finished in last place with a franchise-worst 1–13 record. In his fourth and final Pro Bowl appearance, Sayers was the West's leading rusher and its leading receiver. For the third time in as many Pro Bowl performances, he was named the back of the game.

1970–1971: Left knee injury and retirement

In the 1970 preseason, Sayers suffered a second knee injury, this time bone bruises to his left knee. Attempting to play through the injury in the opening game against the Giants, his production was severely limited. He sat out the next two games and returned in Week 4 against the Vikings, but he was still visibly hampered, most evident when he was unable to chase down lumbering Vikings defensive lineman Alan Page during a 65-yard fumble return. Sayers carried only six times for nine yards before further injuring his knee. He underwent surgery the following week and was deemed out for the remainder of the season. He had carried 23 times for 52 yards to that point. During his off time, Sayers took classes to become a stockbroker and became the first black stockbroker in his company's history. He also entered a Paine Webber program for 45 nationwide stockbroker trainees and placed second highest in sales.

After another knee operation and rehabilitation period, Sayers attempted a comeback for the 1971 season. He was kept out of the first three games after carrying the ball only twice in the preseason, as Bears head coach Jim Dooley planned to slowly work him back into the rotation. His first game back was against the New Orleans Saints on October 10, in which he carried eight times for 30 yards. After the game, he told reporters he was satisfied with his performance and that his knee felt fine. The following week, against the 49ers, he carried five times before injuring his ankle in the first quarter, an injury that ultimately caused him to miss the remainder of the season. He was encouraged to retire but decided to give football one last try. Sayers' final game was in the 1972 preseason in which he fumbled twice in three carries; he retired days later.

Playing style

Sayers' ability as a runner in the open field was considered unmatched, both during his playing career and since his retirement. Although he possessed modest raw speed—he completed a 100-yard dash in 9.7 seconds—he was highly elusive and had terrific vision, a combination which made him very difficult to tackle. Actor Billy Dee Williams, who portrayed Sayers in the 1971 film Brian's Song, likened his running to "ballet" and "poetry". Mike Ditka, a teammate of Sayers' for two seasons, called him "the greatest player I've ever seen. That's right—the greatest." Another former teammate, linebacker Dick Butkus, famous for his tackling ability, said of Sayers:

He had this ability to go full speed, cut and then go full speed again right away. I saw it every day in practice. We played live, and you could never get a clean shot on Gale. Never.

On his tendency to escape from tight situations, Sayers once proclaimed, "Just give me 18 inches of daylight. That's all I need." He felt if his blockers created 18 inches of space for him to run through, he could break a run into the open field. This quick acceleration became a hallmark of his running style, although some of it was lost following the injury to his right knee. After the injury, he relied more on tough running and engaging tacklers for extra yards.

Despite the production from Sayers, the Bears as a whole struggled to find success; in games that Sayers played, the team compiled a record of 29 wins, 36 losses, and 3 ties, and failed to reach the postseason. Because of this, Sayers' main focus each postseason was on the Pro Bowl, where he excelled. Showcasing his breakaway talents, throughout his Pro Bowl career he achieved runs of 74, 52, 51, 48, and 42 yards. In the Pro Bowl following his rookie season, he had kickoff returns of 51 and 48 yards, despite limited opportunities due to the East's attempts to punt and kick away from him. In the next season's game, his 10 yards-per-carry average set a Pro Bowl record. He was named the "back of the game", an honor he received again in 1968 and 1969, joining Johnny Unitas as the only players to win three Pro Bowl MVP awards. "The Pro Bowl is the time to prove how good you are, playing against the best of your peers," recalled Sayers. "I took it as a challenge. I came into the game in shape, came to play."

I Am Third and Brian's Song

In 1967, Sayers and Bears teammate Brian Piccolo became the first interracial roommates in the NFL. Sayers' ensuing friendship with Piccolo and Piccolo's struggle with cancer (embryonal cell carcinoma, which was diagnosed after it metastasized to a large tumor in his chest cavity), became the subject of the made-for-TV movie Brian's Song. The movie, in which Sayers was portrayed by Billy Dee Williams in the 1971 original and by Mekhi Phifer in the 2001 remake, was adapted from Sayers' account of this story in his 1970 autobiography, I Am Third. A notable aspect of Sayers' friendship with Piccolo, a white man, and the first film's depiction of their friendship, was its effect on race relations. The first film was made in the wake of racial riots, escalating racial tensions fueled by Martin Luther King's assassination, and charges of discrimination across the nation. Sayers and Piccolo were devoted friends and deeply respectful of and affectionate with each other. Piccolo helped Sayers through rehabilitation after injury, and Sayers was by Piccolo's side throughout his illness until his death in June 1970.

Later life

Sports administration and business career

Sayers worked in the athletic department at his alma mater, the University of Kansas, for three and half years, before he was named the athletic director at Southern Illinois University Carbondale in 1976. He resigned from his position at Southern Illinois in 1981.

In 1984, Sayers founded Crest Computer Supply Company in the Chicago area. Under Sayers' leadership, this company experienced consistent growth and was renamed Sayers 40, Inc. Currently, he is chairman of Sayers 40, Inc., a technology consulting and implementation firm serving Fortune 1000 companies nationally with offices in Vernon Hills, Illinois, Canton, Massachusetts, Clearwater, Florida, and Atlanta. Sayers and his wife are also active philanthropists in Chicago. They support the Cradle Foundation—an adoption organization in Evanston, Illinois, and they founded the Gale Sayers Center in the Austin neighborhood of Chicago. The Gale Sayers Center is an after-school program for children ages 8–12 from Chicago's west side and focuses on leadership development, tutoring, and mentoring. In 2009, Sayers joined the University of Kansas Athletic Department staff as Director of Fundraising for Special Projects.

Concussion lawsuit and dementia

In September 2013, Sayers sued the NFL, claiming the league negligently handled his repeated head injuries during his career. In the lawsuit, Sayers claimed he suffered headaches and short-term memory loss since retirement. He stated he was sometimes sent back into games after suffering concussions, and that the league did not do enough to protect him. The case was withdrawn after Sayers claimed it was filed without his permission, but he filed a new lawsuit in January 2014 along with six other former players.

In March 2017, Sayers' wife, Ardythe, revealed that he had been diagnosed with dementia four years prior. She stated that a Mayo Clinic doctor confirmed it was likely caused by his football career. "It wasn't so much getting hit in the head," she said." It's just the shaking of the brain when they took him down with the force they play the game in."

Legacy and honorsRecords

Sayers' record of 22 touchdowns in a season was broken by O. J. Simpson in 1975, who scored 23; his 22 touchdowns remains a rookie record as of 2017. Sayers remains the most recent player to score at least six touchdowns in a game. His career kickoff return average of 30.56 yards is an NFL record for players with at least 75 attempts, and he is one of several players to have scored two return touchdowns in a game. He is tied with four other players for the second most career kickoff return touchdowns, with six. Sayers' rookie record of 2,272 all-purpose yards was broken in 1988 by Tim Brown, who gained 2,317 yards through 16 games, two more games than Sayers set the record in. His single-season all-purpose yards record of 2,440 set in 1966 was broken in 1974 by Mack Herron, who surpassed it by four yards.

Post-career recognition

Sayers was elected to the Lincoln Journal's Nebraska Sports Hall of Fame in 1973, the first black athlete to be so honored. He was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1977. His number 48 jersey is one of three retired by the Kansas Jayhawks football team.

Later in 1977, Sayers was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame and is still the youngest inductee in its history. On October 31, 1994, at halftime of a Monday night game, the Bears retired his number 40 at Soldier Field, along with number 51, which had been worn by teammate, linebacker Dick Butkus. The Pro Football Hall of Fame selection committee named Sayers to its NFL 1960s All-Decade Team, which comprised the best players of the 1960s at each position. In 1994, Sayers was selected for the NFL 75th Anniversary All-Time Team as both a halfback and a kickoff returner; he was the only player selected for multiple positions. In 1999, despite the brevity of his career, he was ranked 22nd on The Sporting News's list of the 100 Greatest Football Players.

Wikipedia

0 notes