#There could be and historically was a great deal of overlaps between these concepts; they could bolster or even lead to the other; etc

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"My analysis is predicated on a distinction between the medieval concepts of authority, defined as the legitimate right to act, and of power, the ability to impose one’s will on others. By the High Middle Ages, inherited authority was associated with a fief, granting individuals the right to rule in a certain region according to certain prescribed regulations. While authority typically implies a chain of command, power, a more elusive quality, is defined abstractly as the ‘‘ability to act effectively on persons or things, to make or secure favorable decisions which are not of right allocated to the individuals or their roles.’’ According to this definition, power is much more elusive, based on personal effectiveness and influence rather than on sanctioned right to command. This distinction clearly operated in the Middle Ages, where the two concepts were related but not synonymous. Authority was associated with hereditary [or granted] titles and offices. However, while the possession of authority legitimated one’s actions, it did not guarantee their effectiveness. Conversely, while individuals who lacked authority could impose their will on others by force or influence, their actions would not have been considered legitimate. Although they are often used interchangeably by modern authors, authority and power referred to distinct attributes in the Middle Ages."

— Erin L. Jordan, "The "Abduction" of Ida of Boulogne: Assessing Women's Agency in Thirteenth-Century France", French Historical Studies, Volume 30, Issue 1 (Winter 2007)

#...I'm not sure what to tag this#medieval#my post#Don't reblog these tags#I'm sure that there have been other interpretations and assessments of these terms#There could be and historically was a great deal of overlaps between these concepts; they could bolster or even lead to the other; etc#But I think this distinction is still helpful#Someone holding a formalized position is ultimately different from someone acting in that way in a de-facto or ad-hoc capacity#I find it especially notable in the context of institutional sexism#Because I feel like sometimes historians who (rightfully) want to move past the 'Middle Ages were a period of constant suffering for women'#rhetoric or to correct the false idea of a public/private binary (there was none) sometimes tip the balance too far the other way#and end up acting as though it doesn't matter if women (and even queens) weren't given positions of authority#that their male counterparts were given because they could be powerful and obeyed anyway so who cares?#(eg: Lisa Benz in Three Medieval Queens which ends up ignoring both the context of English queenship & the regency of Eleanor of Provence)#Like...that's really not the point? Or rather that's EXACTLY the point.#If they were capable then why weren't those capabilities given formal recognition?#What was the problem with giving them those additional positions that men around them had by default?#Even if those official positions were 'just' symbolic or ceremonial why was that symbolism or ceremony maintained in the first place?#Like this is very very basic I can't believe I even have to discuss it#also btw Helen Maurer uses this similar distinction when analyzing Margaret of Anjou which Jordan highlighted in the notes#in the sense that queens did have both power and authority by the virtue of their station;#but in the late medieval era post Eleanor of Provence they generally* weren't given 'additional' positions in governance#(*only exempting Elizabeth Woodville's membership in councils as far as I know - which is at any rate the exception that proves the rule)#so I found that pretty interesting as well!#...anyway I'm mainly posting this so I can use it as a reference for some future posts lol

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

I recently read a fascinating book chapter in which the author makes a compelling case for defining a subset of historical despressive conditions specifically related to the struggles of queer men (he calls it "homodepression", which is not a very elegant word to my ear, but it gets the point across). He mentions that, at the time of writing, there was no comprehensive survey of depression and related conditions for the 18th century – but, since you've just written a thesis about it, that might have changed! Do you happen to have some reliable resources you could share on the topic?

For interest, the chapter is Rousseau, G. (2003). “Homoplatonic, Homodepressed, Homomorbid”: Some further genealogies of same-sex attraction in western civilization. In Love, Sex, Intimacy, and Friendship Between Men, 1550–1800. Palgrave Macmillan.

Thank you for the ask!

Firstly – let me just say that I'm kind of obsessed with the chapter's title, kind of a love-hate situation. I'll definitely give it a read once I get home! (It is especially interesting for me since I'm convinced that a queer reading of my primary text is possible. I haven't brought it up because academia in CR still can be quite conservative sometimes but I've definitely danced around the subject a bit. I may post more about it here after my defence to get it out of my system?)

Regarding your question – I mostly centred my analysis around few selected philosophical texts in my actual thesis, but I should have a folder on my laptop from back when I did background research. I can definitely look into it once I get home!

I can also ask my supervisor, he's bound to have much more resources than I do and I feel like I need to refresh my memory about the historical context before I defend anyway. I'll be sure to let you know!

Right now, without the access to my laptop, the one thing I can say that could potentially help is that like so many things, it may be an issue of language.

My research is technically about 'hypochondria'. That can be confusing because the meaning of the word has shifted quite a bit from the 18th century, but I've made a case that there's a great deal of overlap between hypochondria and the current understanding of depression, based on the current diagnostic criteria for depression. The word 'melancholy' was also sometimes used to refer to a similar idea. If can get quite blurry though, authors are often playing a bit fast and loose with the concepts.

So, searching for a review of either melancholy or hypochondria in the 18th century could (hopefully) yield some interesting results! I'll get back to you with links to potentially interesting articles once I get home/talk to my supervisor.

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

tell me about any of the lorn gods but specifically the ones you feel you haven't gotten the chance to ramble about as much

I'm gonna choose Tema specifically for this!

Tema in some ways out-of-universe was defined by the other characters. I had a vague concept of a plant/nature god before her but that figure arguably became the prototype for Sivi, which left me scratching my head for a great deal of time on what another god could be that wasn't overlapping with Sivi, since 'stone' and 'wood' are often conceptually united under earth. This ended up really fitting for her character, because she's steeply younger than the elder trio, and kind of trying to be her own god in their shadows more than any of them had to exist 'in the shadows' of the others considering they were fairly close in age and both Garu and Dena spread out heavily as children.

I'm a really big sucker for white mage/cleric type characters explored in unorthodox directions, since I think many fantasy stories have a bad habit of characterizing the healer as the most modest, restrained, unthreatening person, or at minimum someone who superficially comes off that way such that it's shocking or comedic if they aren't.

A big thing I tend to think of with gods in particular is that 'a god' to me is not merely a Being Of Great Power- they are also defined to some degree by a social role. Real historical pantheons are staffed by what mattered to the humans at this time- to the people of ancient Egypt, the yearly flooding of the Nile was vital to survival, so Isis- who was kind of a big cheese- was a goddess of the Nile and its floods.

It's also significant that the color gods go in sequence- they have a strict birth order and in some ways the ideas they embody commentate off each other. Dena in some ways embodies the raw promethean 'clay' that shaped the earth- molten rock- and when that cools, it becomes stone, Sivi's domain- just as Sivi's sense of foundations and civilization can't be born first without the raw, chaotic creation that Dena connects to. And likewise, Sivi's ordering of man and nature, the notion of not merely village but commonwealth and country- paves the way for Garu, a god of outcasts, rebels, and others who defy or are rejected/abandoned by an order.

So Tema in turn is shaped by all three of her older siblings, but particularly by Garu, even if she gets along better with Sivi. Compared to Aeon and Ilvi and their dramatic birth, Tema is superficially the "uncomplicated child" of the three younger gods, so that kind of made me think of her as the good girl who's trying hard to not be so needy at a point her older siblings are so busy and so worried. This tied well with one of the few surviving traits from the original concept- that she's quite bossy and pushy, the way that a growing tree might churn or throw things around with its roots, and plants can split foundations that lie underneath them.

This all came together into a life god- and one of my favorite ideas about life is how when you say "life god" the typical image is either a little girl or a motherly woman all with flowers in her hair, surrounded by beauty and grace- Persephone and Demeter.

But Tema isn't just life- she's a life who came as the fourth child after Garu- god of pestilence, hunger, dissatisfaction, anger, and frustration. The gnawing, furious, desperate thing that drove us to the first revolution of the stone age.

Life is... relentless. It seethes. It boils. Watch kudzu overtake a field or the concept of wolf trees- that devour so much from the soil nothing can grow around them- and for all the ways that fertility and vitality have been sought-after prizes for us, there is a "family resemblance" between Tema and her big brother, even when she doesn't like him- in particular because she doesn't like him. He's not the one she wants to be like- she wants to be like Sivi, all-beloved, all-adored.

So, Tema is all of that restlessness, all of that seething, bone-chewing, blood-drinking life that is born from successful predation. When windfalls blow in the right direction, when fortune smiles and the vicious work of Garu's domain pays off... it gives way to a different direction to that energy. The hunter-gatherer becomes the forest-tender, or the field-tiller; seeds are sown, weeds are pruned. Custodianship, symbiosis, and diligence. Living things, far more than anything else, have a contrast between if they're wild or tamed.

Tema, like Sivi, has an animal motif that is a domesticated creature, something whose nature changes when it is known by humans. In her case, it's a sheep or goat- ambitious climber and boundless energy. An angry goat isn't quite as destructive as a charging bull, but goats and sheep aren't beasts of burden that often- mostly they're valued for their coats.

Lambs are also seen as a symbol of innocence which comes back to that contradictory nature of Tema, that she is a wild thing, like climbing ivy or a goat on a mountainside- even if she is further from "the mother sun" she is ambitious enough to try and reach for that idea of All-Color anyway. But also, that ambition ironically makes her covet order- she's trying to be the bellwether herding everybody into place. So she thinks of herself- presents herself- as the sweet shepherd-child leading people back into order, diligence, "just till your field and be happy with it, good things will follow, prosperity is reliable and you don't have to gamble or hurt others" after Garu and before the truly untameable aspects of Aeon-

...but in practice, there is something pretty ungovernable about Tema herself. Every peaceful grazing herbivore will fight to defend itself and will resort to opportunistic meat-eating if food grows scarce. For the field to stay flourishing, its appetites must be sated.

So Tema, out of the gods, is probably the one who is simultaneously wild and tame, and has the biggest conflict with it. She has widely celebrated and welcomed healing magic, but that magic can also cause a body to run wild very easily. The truly-terrifying deathless abominations, ever-shifting, that she's given rise to in desperation to fix problems, are a testament to how powerful the 'little sapling' truly is- and how uneasily her power bends itself to being tamed or pruned into shape. Cut a bud off a tree and it will grow new ones as long as it has the resources to do so; the act of keeping a bonsai or a farm field is a continuous effort against a force that cannot tire.

And when the closest sibling to her in age is Aeon- the great pelagic force of destruction and entropy that rages so untamed as to be feared by their other siblings, this doesn't settle Tema's conflict at all, but exacerbates it. Her need to have power, to stay in control, drives her wild side at the same time she covets tameness for it- she is a good little girl, and she is loved by mortals for being a good little girl, daughter of paddocks and fields, priestess of honest work and princess among sovereigns- and she is a thing terribly, terribly afraid of growing up, because once she leaves this flowerpot, she suspects she will not be nearly so lovely to the mortals who don't see her family resemblance.

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

~HENRY TUDOR: A SOCIOLOGICAL INTERPRETATION.~

Today, I'll be discussing a character who left his mark in History, fathering a dynasty whose most proeminent members were his (second) son Henry VIII and his granddaughter Elizabeth I. Often overshadowed by his descendants, Henry's own deeds as a king and as an individual of his own days have been neglected until recently, when efforts from British historians have been working hard to change that.

The reason why I decided to bring him here was not only due to personal affections, though they certainly helped it, but because there are aspects overlapped in social structures that shaped him. In other words: what's Henry Tudor as a sociological individual? Can we point him out as a constant foreigner or someone whose socialization process were strongly marked by the addition of two different societies?

Henry Tudor was born in Pembroke, located in Wales, in January 28th 1457. His mother was Margaret Beaufort, a proeminent lady whose grandfather John Beaufort was the son of John of Gaunt, son in turn of King Edward III of England. The duke of Lancaster fathered four ilegitimated children (who were legitimated in posterity) by his (third marriage to his then) lover Katheryn Swynford, amongst whom John Beaufort was the oldest. Therefore, Henry was 3x grandson. to the duke and, despite what some might argue when Henry IV became king, in great deal to inherite the throne. Well, it's not my intention to deepen the discussion as to Henry's legitimacy or the Beauforts.

Though his father's ancestry, Henry's blood led him to the royal house of Valois. His paternal grandmother, Katherine de Valois, was the sister of Isabella, who had been the second wife of the ill-fated king Richard II. She was also descended of Louis IX and his spanish wife, Blanche de Castille. Henry was also a royal man from the Welsh lands, as Owain Tudor, his grandfather, was related to several princes of Wales. By all these I said, the first thing one might think (considering 15th century and it’s nobility) Henry would receive a proper education due to his status. However, this would not happen in the strict sense of the word. Let us not forget that England was collapsing by the time of Henry Tudor's birth and his childhood. Why am I using the word 'collapse' to qualify the civil war we know named as wars of the roses?

Émile Durkheim, a french sociologist, would write several centuries later, about how a society is formed: he compared it to the working of a human body. If the head, the brain of our body does not work well, what happens? The body will not work well, certainly. Neither would the head work well if other parts hurt somehow. Although if you did break a leg, you could still make use of your brain, but as a whole how limited wouldn't you be? He'd also say that when the human body, or as he called, the society was sick, it was because of the social structures which imposed the human being to the point where there would be no individuality, no matter of choice.

Such created social facts that were completely external (althoug well internalized through means of a process we call socialization) but coercitive. If they are not working, what does this mean? That soon another social facts will be replacing the former one. But between one and another, we have a "very sickly" society. Taking this understanding back to England's 15th century, it is not difficult to see what Durkheim was talking about.

The king was the head of the English body. If we have here two kings fighting over one crown, fighting over the rule of an entire body... Well, then? We have the collapse, a civil war that lasted for the next 30 years. Here, it's less about discussing who started what but why they did what they did, and the explanation for it. Power is power. It's crystal clear, and a statement that, however simple might it sound, points to the obvious. Factions that fought for power intended to dominate others, using the concept very well developed by sociologists as Pierre Bourdieu and Norbert Elias. This domination is a large field, a concept that embrace all sorts of it. Looking back to England's latter half of the century, domination was peril. The head was about to explode. The society was ill... and dominated by it.

What were the values? What was the racionalization proccess of social action led by individuals that were not only individuals but a group? How would all of this affect Henry Tudor? It was not about merely blaming the capitalism, because such coercitive system wasn't present yet. But Henry was, directly or not, linked to the royal house of Plantagenets, whose eagerness for dominating one another and by extension the rest of the country would include him in the game.

"Game." For Durkheim, this would imply an agitation, like a wave of sea, from which no one could escape from. Let's not forget that Institutions created ideas, renewed them, shaped them to the practice whether to dominate the weaker or to defeat the stronger. Whatever the purpose, we here have the Church, not the religiosity, but the precursor of ideas would subdue individuals to share (or manipulate to their own goals anyways) values in order to keep determined mentality to it. But also, monarchy was too an institution which held control over the lives and deaths of thousands of people. A monarch, as we know, is never alone regardless of how "absolut" they could be in different times and contexts. They were not above the law, either. At least where the socialization process is concerned. For the monarch embodied the content which was the law back then. He was literally the law.

Furthermore, Henry's education would foresee this fighting, which I'm not merely referring to custody going from his mother to another, before finally staying under his uncle's responsibilities, as well as the civil war itself. (Anyone remembers Warwick executing Herbert before the boy?)

See, we all know and comprehend today what trauma are capable of doing to someone. Such experience is the main responsible for shaping ideas, values and even costumes. Now, a society which is very much sick by it's own values and moral costumes (a point here must be made: the public consciousness always preached for a warrior, strong king, but has no one thought how this "common sense", validated by a general expectation towards the head of society, was what led it to... well, for the lack of better word, suicide itself?

For it's widely accepted that weak kings do not last long. But that is when we deal with a good deal of expectations that, when turned to frustrations, bring awful results. If England's society was ill in it's very extreme sense of the word, was because the values they created turned against themselves and that would leave it's mark in a boy as Henry. And until the age of 14, he was still absorbing these concepts, these morals, values, costumes from institutions (let's not forget that a monarch shares such with the nobility that surrounds him, as was the case of House Lancaster,f.e) before he was casted out to Bretagne and, in posteriority, to France. Now, I believe you all know what was done whether in England or with our king during these 14 years spent outside his own country before he became king upon the victory settled on the battle of Bosworth field.

I am not interested in discussing historical facts. At least not now, as we are finally dealing with Henry Tudor as a social actor

----/-HENRY TUDOR: A FOREIGNER? AN EXILED? OR AN OUTCAST?--

These questions mobilized me as I came to read a text written by 19th century sociologist named Georg Simmel. He wrote an essay (pardon by any mistakes in translations done from here on) entitled "The Foreigner", in which he brings a sociological question at why foreigners are seen as strangers who are never entirely immersed in the society they attempt to be part in.

Here's an excerpt translated by me in which he explains it:

"Fixed within a determined social space, where it's constancy cross-border could be considered similar to the space, their position [the foreigner's] in it is largely determined by the fact of not belonging entirely to it, and their qualities cannot originate from it or come from it, nor even going in it." (SIMMEL, 2005: 1.)

Furthermore, he adds:

“The foreigner, however, is also an element of the group, no more different than the others and, at the same time, distincted from what we consider as the 'internal enemy'. They are an element in whose position imanent and of member comprehend, at the same time, one outsider and the other insider." (SIMMEL, 2005: 1).

Here's why Henry, as Earl of Richmond, was not well seen by the Britons and the French, in spite of being "accepted" by them. Never forget that he would still be seen as an outsider by his own fellows. As Richard III would call Henry a bastard, one could understand this accusation with sociological implications. English back then detested these foreigners and by the concept brought here by me from Simmel we can understand why. But we could also see being called a bastard as a way to point out Henry's localization. Where can the Earl of Richmond & soon-to-be king be located?

I have pointed this far the structures which were raised and caused a collapsed society to live broken in many, many ways and how this affected Henry this far. Seeing how foreigner he was, nonetheless, he did not belong neither to England (at first) nor to the Continent.

On that sense of word, says Simmel (2005: 3):

"A foreigner is seen and felt, then, from one side, as someone absolutely mobiled, a wanderer. As a subject who comes up every now and then through specific contacts and yet, singularly, does not find vinculated organically to anything or anyone, nominally, in regards to the established family, locals and profissionals”

Even though we find a dominant group of foreigners in France, as we are talking about of nobles displeased with the Yorkist cause and supporters of the Lancastrian House, they were not majority. Where can we locate Henry, then? We don't, because he was not a French and however well he could speak the language, it was not his birth language. The French culture was not passed nor naturalized by him through the teachings of a family or the church by the institutions: monarchy, church, family, parliament, etc; he would have been defeated a long time. But that he did manage to, using this popular expression, put things together and become the first king to die peacefully since Henry V, it tells us a lot. Not rarely an immigrant is accepted by a society whose demands are forced upon him, most of the times in aggressive ways. But it's not often either that we see a king occupying such place in society.

Indeed, one might say that kings as Henry II and the conquerors before him were too foreigners, but not in the sociological way I'm explaining. Because the social structures were different. Henry's government were settled in a more centralized ruling, far more just and peaceful, more economic and less concerned with waging wars than his antecessors. The need to migrate was not 'forced', neither 'imposed' and even back to the 11th and 12th centuries were motivated by different reasons. That's to accentuate how English society evolved throughout the centuries. And I used again and again Georg Simmel to prove my point about casting a sociological light towards Henry VII not as a historical character so distant of us and who remains an object of controversial discussions, but a man of his times who was forced to deal with expectations that placed him in social positions nearly opposed to one another to fulfill each role whether as king or as a man. For some reason, the broken society shaped Henry as an immigrant, but as history shows us, it was this immigrant who helped shape medieval society, directing it towards the age of Renaissance and in posteriority to Modern Age.

Finally, to close this thread I leave here another quote (translated to English by me) found in the text written by Simmel:

"The foreigner, strange to the group [he is in], is considered and seen as a non-belonging being, even if this individual is an organic member of the group whose uniform life comprehends every particular conditioning of this social [mean]. (...) [the foreigner] earns in certain groups of masses a proximity and distance that distinguishes quantities in each relationship, even in smaller portions. Where each marked relationship nduced to a mutual tension in specific relationships, strenghtening more formal relations out of respect to what's considered 'foreigner' of which are resulted." (SIMMEL, p 7).

Bibliography:

AMIN, Nathen. https://henrytudorsociety.com/

DURKHEIM, Émile. "The Division of Labor in Society”.

KANTOROWICZ, Ernst H.”The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Medieavel Political Theology.”

PENN, Thomas. Winter King: Henry VII and the Dawn of Tudor England.

SIMMEL, Georg. The Foreigner. In: Soziologie. Untersuchungen über die Formen der Vergesellschaftung. Berlin. 1908.

#Henry VII#King Henry VII#Henry VII of England#sociology#socio-history#historical sociology#immigration#sociology of immigration#Henry Tudor#Tudor dynasty

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ribbons of Scarlet: A predictably terrible novel on the French Revolution (part 1)

Parts 2, 3, 4 and 5.

Q: Why is this post in English? Isn’t this blog usually in French?

A: Yes, but I can’t bypass the chance, however small, that someone in the book’s target audience might see and benefit from what I’m about to say.

Q: Why did you even read this book? Don’t you usually avoid bad French Revolution media?

A: My aunt left the book with me when she came for my defense last November. I could already tell it would be pretty awful and might not have read it except that I needed something that didn’t require too much concentration at the height of the Covid haze and I — like most people who insisted on finishing their doctorate despite the abysmal academic job market — have a problem with the sunk cost fallacy, so once I got started I figured I might as well find out just how bad it got.

Q: Don’t you have papers to grade?

A: … Next question.

Q: Aren’t you stepping out of your lane as an historian by reviewing historical fiction? You understand that it wasn’t intended for you, right?

A: First of all, this is my blog, such as it is, and I do what I want. Even to the point of self-indulgence. Why else have a blog? Also, I did receive encouragement. XD;

Second, while a lot of historians I respect consider that anything goes as long as it’s fiction and some even seem to think it’s beneath their dignity to acknowledge its existence, given the influence fiction has on people’s worldview I think they’re mistaken. Besides, this is the internet and no one here has any dignity to lose.

Finally, this is not so much a review in the classic sense as a case study and a critical analysis of what went wrong here that a specialist is uniquely qualified to make, not because historians are the target audience, but because the target audience might get the impression that it’s not very good without being able to articulate why. To quote an old Lindsay Ellis video, “It’s not bad because it’s wrong, it’s bad because it sucks. But it sucks because it’s wrong.” Or, if you prefer, relying on lazy clichés and adopting or embellishing every lurid anecdote you come across is bound to come across as artificial, amateurish and unconvincing.

This is especially offensive when you make grandiose claims about your novel’s feminist message and the “time and care” you supposedly put into your research.

I also admit to having something of a morbid fascination with liberals creating reactionary media without realizing it, which this is also a textbook example of (if someone were to write a textbook on the subject, which they probably should).

With that out of the way, what even is this book?

The Basics

It’s a collaboration between six historical novelists attempting to recount the French Revolution from the point of view of seven of its female participants. One of these novelists is in fact an historian herself, which is a little bit distressing, given that like her co-authors, she seems to consider people like G. Lenotre reliable sources. But then, she’s an Americanist and I’ve seen Americanists publish all kinds of laughable things about the French Revolution in actual serious works of non-fiction without getting called out because their work is only ever reviewed by other Americanists. So.

Anyway, if you’re familiar with Marge Piercy’s (far superior, though not without its flaws) City of Darkness, City of Light, you might think, “ok, so it’s that with more women.” And you might think that that’s not so bad of an idea; Marge Piercy maybe didn’t go all the way with her feminist concept by making half the point of view characters men (though I’d argue that the way she frames how they view women was part of the point). It’s even conceivable that if Piercy had wanted to make all the protagonists women her publisher would have said no on the grounds of there not being a general audience for that. It was the 1990s, after all.

Except the conceit this time is they’re all by different authors, we have some counterrevolutionaries in the mix, and instead of the POV chapters interweaving, each character gets her own chunk of the novel, generally about 70-80 pages worth, although there are a couple of notable exceptions. We’ll get to those.

It’s accordingly divided as follows:

· Part I. The Philosopher, by Stephanie Dray, from the point of view of salonnière, translator, miniaturist and wife of Condorcet, Sophie de Grouchy, “Spring 1786” to “Spring 1789”; Sophie de Grouchy also gets an epilogue, set in 1804

· Part II. The Revolutionary, by Heather Webb, from the point of view of Reine Audu, Parisian fruit seller who participated in the march on Versailles and the storming of the Tuileries, 27 June-5 October 1789

· Part III. The Princess, by Sophie Perinot, from the point of view of Louis XVI’s sister Élisabeth, May 1791-20 June 1792

· Part IV. The Politician, by Kate Quinn, from the point of view of Manon Roland, wife of the Brissotin Minister of the Interior known for writing her husband’s speeches and for her own memoirs, August 1792-(Fall 1793 — no date is given, but it ends with her still in prison)

· Part V. The Assassin, by E. Knight, which is split between the POV of Charlotte Corday, the eponymous assassin of Marat, and that of Pauline Léon, chocolate seller and leader of the Société des Républicaines révolutionnaires, 7 July-8 November 1793

· Part VI. The Beauty, by Laura Kamoie, from the point of view of Émilie de Sainte-Amaranthe, a young aristocrat who ran a gambling den and who got mixed up in the “red shirt” affair and was executed in Prarial Year II, “March 1794”-“17 June 1794”

An *Interesting* Choice of Characters…

Now, there are some obvious red flags in the line-up. I’m not sure, if you were to ask me to come up with a list of women of the French Revolution I would come up with one where 4/7 of the characters are nobles/royals — a highly underrepresented POV, as I’m sure you’re all aware — but fine. Sophie de Grouchy is an interesting perspective to include and Mme Élisabeth at least makes a change from Antoinette? And though the execution is among the worst (no pun intended) Charlotte Corday’s inclusion makes sense as she is famous for doing one of the only things a lay audience has unfortunately heard of in association with the Revolution.

Reine Audu is actually an excellent choice, both pertinent and original. Credit where credit is due. Manon Roland and Pauline Léon are not bad choices either in theory, but given the overlap with Marge Piercy’s book, if you’re going to do a worse job, why bother? The inclusion of Sophie de Grouchy, while, again, not a bad choice, also kind of makes this comparison inevitable, as another of Piercy’s POV characters was Condorcet.

But Émilie de Sainte-Amaranthe? I’m not saying you couldn’t write an historically grounded and plausible text from her point of view, but her inclusion was an early tip-off that this was going to be a book that makes lurid and probably apocryphal anecdotes its bread and butter.

The absolute worst choice was to make Pauline Léon only exist — at best — as a foil to Charlotte Corday. (It turns out to be worse than that, actually. She’s less of a foil than a faire-valoir.)

Still, why does no one write a novel about Simone and Catherine Évrard (poor Simone is reduced to “Marat’s mistress” here, not just by Charlotte Corday, which is understandable, but also by Pauline Léon) or Louise Kéralio or the Fernig sisters or Nanine Vallain or Rosalie Jullien or Jeanne Odo or hell, why not one of the dozens of less famous women who voted on the constitution of 1793 or joined the army or petitioned the Convention or taught in the new public schools. Many of them aren’t as well-documented, but isn’t that what fiction is for?

Let’s try to be nice for a minute

There are things that work about this book and while the result is pretty bad, I think the authors’ intentions were good. Like, who could object to the dedication, in the abstract?

This novel is dedicated to the women who fight, to the women who stand on principle. It is an homage to the women who refuse to back down even in the face of repression, slander, and death. History is replete with you, even if we are not taught that, and the present moment is full of you—brave, determined, and laudable.

It’s how they go about trying to illustrate it that’s the problem, and we’ll get to that.

For now, let me reiterate that while I’m not a fan of the “all perspectives are equally valid” school of history or fiction — or its variant, “all *women*’s perspectives are equally valid” — and there are other characters I would have chosen first, it absolutely would have been possible to write something good with this cast of characters (minus making Charlotte Corday and Pauline Léon share a section).

The parts where the characters deal with their interpersonal relationships and grapple with misogyny are mostly fine — I say mostly, because as we’ll see, the political slant given to that misogyny is not without its problems. These are the parts that are obviously based on the authors’ personal experience and as such they ring true, if not always to an 18th century mentality, at least to that lived experience.

Finally, there are occasionally notes that are hit just fine from an historical perspective as well. The author of the section on Mme Élisabeth doesn’t shy away from making her a persistent advocate of violently repressing the Revolution. Manon Roland corresponds pretty well to the picture that emerges from her memoirs even if the author of her section does seem to agree with her that she was the voice of reason to the point of giving her “reasonable” opinions she didn’t actually hold.

I should also note that while the literary quality is not great, it’s not trying to be great literature and in any case, on that point at least, I’m not sure I could do better.

Ok, that’s enough being nice. Tune in next time for all the things that don’t work.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Permutations of Post-Agricultural Civilizations

Industrial, Technological, and Scientific Formations

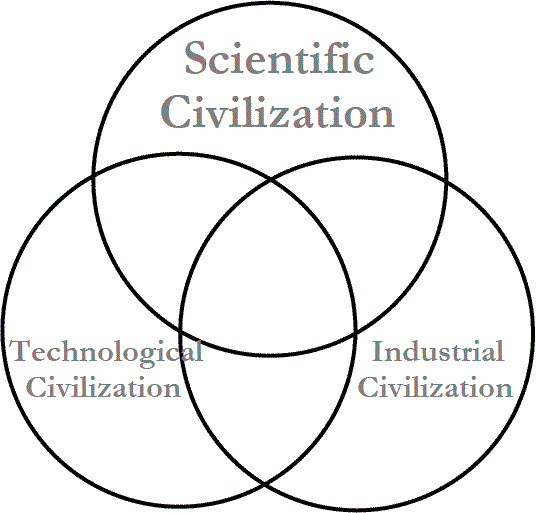

Having recently written about scientific civilization through the lens of comments by Jacob Bronowski and Susanne Langer, I have been doing more research on the idea of scientific civilization for further posts in the series. This has brought additional material to my attention, but it has also raised questions. Why focus on scientific civilization? Does scientific civilization have a special place in the future of civilization, or ought it to have a special place in the future of civilization?

In particular, what relationship does scientific civilization have to other forms of post-agricultural civilization, or what we might also call modern civilization? One can find “industrial civilization,” “technological civilization,” and “scientific civilization” used synonymously, which raises the question as to whether these ideas are subtly distinct or not. Is there a reason to distinguish between industrial civilization, technological civilization, and scientific civilization, or should we regard them as different names for the same thing?

One way to distinguish these three formations of modernity, and yet show them in relation to each other, is by way of what I call the STEM cycle, which is a tightly-coupled loop of scientific research, technological applications, and industrial engineering which characterizes civilization today. A STEM cycle has long been present in civilization, but in the past the STEM cycle was loosely-coupled, often with generations passing between each stage in the cycle. The combined effect of the scientific revolution and the industrial revolution served to transformed the loosely-coupled STEM cycle of agricultural civilizations (which make intensive use of specialized agricultural technologies, though often in a highly traditional context that discourages innovation) into the tightly-coupled STEM cycle of modern civilization.

There are, of course, many technologies that came about not because of science, but through mere tinkering. It seems that James Watt’s steam engine was the iterated result of the tinkering of many men over a long period of time, so that the central exhibit of the industrial revolution seems to defy my characterization of technology. If one wanted to take the time to carefully select one’s examples, one could assemble a history of technology that almost entirely excluded the contribution of science. I concede this point, but at the same time, I could write a history of technology that was entirely based upon technologies that emerged as a direct result of the dispassionate pursuit of scientific knowledge.

Selective histories aside, all of the most difficult and demanding technologies—nuclear energy, spacecraft, computing, DNA therapies in medicine, and so on—are the result of extensive scientific research, including pure science (Rutherford was doing pure science, but his pure science ultimately made nuclear technologies possible) performed with little or no interest in practical application. This also appears that it will hold good in the future, and the role of tinkering decreases and the role of scientific rigor in the advanced of technology increases. There are thresholds beyond which tinkering cannot pass.

Similar criticisms can be made of each section of the STEM cycle: scientific instruments that advance scientific research that do not come from industrial engineering, and industrial engineering developments that do not come from technology. All of these criticisms are valid, but they do not invalidate the idea of the STEM cycle generally. Also, the definitions of science, technology, and engineering need to be refined considerably in order to consistently make distinctions among these sections of the STEM cycle, which will inevitably have broad areas of overlap. As with my analysis of the institutional structure of civilization, the STEM cycle is an abstraction for use in the analysis of the economic infrastructure of civilization, and any actual processes will be far more complex that this idealized simplification.

For more on the STEM cycle, I have written several posts that examine this idea in detail, including:

The Industrial-Technological Thesis

Industrial-Technological Disruption

The Open Loop of Industrial-Technological Civilization

Chronometry and the STEM Cycle

The Institutionalization of the STEM Cycle

Secrecy and the STEM Cycle

Given a tightly-coupled STEM cycle as characterizing modern civilization, we can differentiate scientific civilization, technological civilization, and industrialized civilization as each being civilizations that emphasize section of the STEM cycle over the other sections of the cycle. In each, all sections of the STEM cycle are present, but in scientific civilization, for example, the section of the STEM cycle that predominates is scientific research.

Coming at this problem from another angle, given my analysis of the institutional structure of civilization, I can formally identify these three formations of modern civilization as follows:

A scientific civilization is a civilization that takes science as its central project

A technological civilization is a civilization that takes technology as its central project

An industrial civilization is a civilization that takes industrial engineering as its central project

The above formulations are, in each case, what I call a “proper” civilization, with other permutations of these formations following from science, technology, and engineering playing different roles in the institutional structure of civilization. This gives us a way to formally distinguish these three formations, but as I have pointed out in other posts, there are a great many different ways in which a civilization might take science as its central project, so there is room for a great deal of variation even among any one of these formations.

These formulations are entirely consistent with the above formulations that distinguish scientific, technological, and industrial civilizations in terms of an emphasis on one section of the STEM cycle: in each formation, there is a tightly-coupled STEM cycle, but in each formation one section of the STEM cycle either serves as the central project of the civilization, or is integral with the central project of the civilization.

The above formulations, then, allow me to integrate my definition of the institutional structures of civilization with the idea of the STEM cycle characterizing modern civilizations. This degree of integration of the two concepts strengthens both. However, I am lacking an intuitively perspicuous way to differentiate scientific, technological, and industrial civilizations. One way to address this deficit would be to formulate a great many scenarios (i.e., thought experiments, with possible real-world exemplifications, but not necessarily tied to actually existing civilizations in the historical record, which record is very shallow for modern civilizations) that highlighted distinctively scientific, technological, and industrial central projects, and then proceed inductively from these scenarios to generalizations that cover all tokens of the type.

I am not yet in a position to delineate an exhaustive description of the possibilities for scientific, technological, and industrial civilizations—this would a project for a lifetime, or for a scientific research program with many contributors—but I do have a few telling examples that can shed some limited light on the possibilities.

In Tinkering with the Mind (and the sequels Tinkering with Science and Addendum on “Tinkering with Science”) I discussed the possibility of innovations derived from high technology tinkering without a scientific basis. Such high technology tinkering could only come within an economic infrastructure built up by a tightly-coupled STEM cycle, but in the case of technologies derived by tinkering, the scientific element in the production of the innovative technology in question would be in the background, while technology and engineering would be in the foreground. In the event that a civilization emerged from the proliferation of such technologies of tinkering (another example would be Shawyer’s EmDrive), we could call this a technological civilization or an industrial civilization, but it clearly would not be a scientific civilization.

Another possibility that is not far from our present economic infrastructure would be a civilization focused on industrial engineering design, to the point that the technology and the science were far in the background, while the design became the focus of interest and development. Here, practical application would run ahead of actual scientific and technological innovation—though “run ahead” might be misleading in this context. Let me explain. Computer technology has been advancing so rapidly over the past several decades that those who use computers have been playing a game of catching up to the most efficient uses of the technologies available. The result has been a number of suboptimal operating systems that all of us present for the computer revolution have passed through in stoic and pragmatic determination. It hasn’t always been enjoyable. Suppose the technological innovations came to an end. One scenario that I have discussed in other contexts would be the collapse of modern civilization leaving a few industrialized enclaves. These enclaves would probably not be large enough to produce new innovations in semiconductor design, but they might be able to keep existing computational infrastructure functioning. Under these circumstances, there would be a strong motivation to use available technology as efficiently and effectively as possible. A real premium would attach to better software applications that could derive better performance from the same hardware.

We have an actual example of this in the Voyager spacecraft, far from us in outer space, indeed, having passed out of the solar system, but engineers on Earth have reprogrammed the spacecraft several times since their launch in order to obtain better results from hardware that cannot be changed. A civilization in which such conditions became the norm could be considered a civilization in which industrial engineering was in the foreground, while technology and science were distantly in the background, being maintained but not improved. If this particular example is to be taken as representative, it may be the case the industrial civilizations sensu stricto only come about after science and technology have faltered, that is to say, in the twilight of scientific civilization or technological civilization. But a generalization of this sweeping kind would require much more study of the problem.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Urban Ecology and Animism in the Landscape of the Great Lakes”: An interview on decay, restoration, bioregionalism, and “ecological citizenship” in the Midwest

From 26 December 2018, Belt Magazine. Excerpts:

Authors Matt Stansberry and Gavin Van Horn recently published books on the urban wildlife of the Great Lakes region (Rust Belt Arcana: Tarot and Natural History in the Exurban Wilds by Belt Publishing, and The Way of the Coyote: Shared Journeys in the Urban Wilds by University of Chicago Press, respectively). In this wide-ranging conversation, Stansberry and Van Horn discuss the overlaps in each other’s books and the progress, challenges, and joys of living with and writing about nature in the industrial Midwest.

GVH: Some of the book is about holding on to what remains, trying to live in a way that allows others to live (such as when you write about box turtles or salamanders). But there are also expressions of hope in the book, particularly when it comes to meeting people who are hard at work on restoration projects. I’m thinking here of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History’s work at Mentor Marsh, and also the lessons you glean from Tim Jasinski of Lights Out Cleveland. Could you tell us a little bit about those projects? And perhaps the strides you see in the Rust Belt to respond with care to the land and water, which you call “holy work”?

MS: Those two chapters show different approaches to dealing with our impacts on wildlife. The first chapter you reference, “Temperance,” explores the effort needed to restore one of Lake Erie’s largest wetlands back into a functioning ecosystem. It’s inspiring because of how daunting the task must have seemed—to try to remove hundreds of acres of nearly impervious invasive reeds. After years of sustained, systematic effort and investment, we are seeing a return of biodiversity to this site.

-

GVH: You end with “The World” card and reflections on what E.O. Wilson has called the “Age of Loneliness” (the Eremozoic Era). After detailing the historic superabundance of biological life in Ohio, you say, “I want to leave you with the impression that our home has a potential to be one of the wildest, most fecund places on the planet… I tell you these things to repeat the names, so that you know that they are there. …There is still plenty of time to roll in the dirt in a forest. Stare out at Lake Erie. Listen to the wind. Don’t live separately from the world. Don’t despair.” What kinds of practices would you recommend for connecting to the magic of the everyday?

MS: So you mention a bunch of good ideas right there. Roll in the dirt. Stare at the lake. Since finishing the book, I’ve read The Enchanted Life by Sharon Blackie, and it’s full of so many brilliant ideas that I’ve been trying, ways to make myself more grounded in the place where I live. We can learn the myths of our home regions, draw big maps of the places we live and hike, plant gardens with native species, craft objects and food out of the plants around us, name the species of birds, start re-enchanting the landscape.

I see a lot of overlaps in our work as well. For example, both of our books center around the study of urban wildlife, animals in the city. You write: “When the city presses in upon me, coyotes remind me of the vitality that weaves its way between the buildings. Humans may often disregard, displace, and disrupt other kinds of animal life, but the anima of what we now call Chicago is not gone. The coyotes keep it flowing; they keep going along, beckoning us toward greater fidelity with our non-human kin. Lead on coyotes. Show what a city can be.”

Engaging with urban wildlife is not something you expected to be doing, and not something historically that has been of interest to the science/naturalist community. What do you learn from studying city creatures that you don’t learn in more rural or wild environments?

GVH: A city constitutes one portion of a landscape continuum. Occasionally in the book, I venture outside of city limits, acknowledging that many species don’t do well in smaller patches of habitat and with human presence (hell, I don’t do well with continual human presence). Yet my focus is on “ordinary” and close-to-home creatures as amazing expressions of life, worthy of our fascination and attention. Familiarity need not breed contempt. Familiarity can be a portal into our most intimate and meaningful relationships. Several essays feature ecologists and biologists who are turning back toward the city with curiosity and scientific rigor, seeking to counter the story of urban nature as less-than-worthy. I suppose I’m doing something similar with my writing.

MS: In one of my favorite essays, “De los pajaritos del monte” you marvel at your friend’s lifelong connection—physical, familial, cultural—to a landscape. You’ve moved around the country, the same way I have, and seem to struggle with that rootlessness. I think we both envy what your friend has with his home landscape. Can you write your way into place? Is even one lifetime enough to get rooted?

GVH: One lifetime, so far as I know, is all we’ve got, so I hope that’s enough to actualize one’s ecological citizenship. As you know, this book was part of my own process of adapting to life in an urban area. Writing is a way to further deepen the bonds of memory, to invite others (and perhaps yourself) to see the world from a fresh perspective. It’s an alchemical process—to transform experience into ink, and then for readers to permit those words to conjure new worlds in their imaginations. And the hope is that those stories, then, shape how a person moves through the landscape and the way they value it.

But the question of roots is one that haunts me a bit, in all honesty. I’m a person that has lived in many places. Some of us are more nomadic in spirit; some landscapes make our hearts sing more than others. What if a person feels displaced—like a plant outside of the microbiome to which it is most suited—and no amount of spiritual equanimity or sheer amount of time spent in a place can create a sense of at-homeness? (...)

MS: You have a chapter exploring Aldo Leopold’s concept of the numenon of the north woods, the ruffed grouse. You suggest Chicago’s numenon is the Night Heron? What’s a numenon and what’s a night heron?

GVH: As one young man who does ecological restoration work on the South Side of the city told me, “It’s a getting better Chicago.” He’s right. A lot of Midwestern cities, like Chicago, are in what is sometimes called a post-industrial phase. (...) [But] the recovery is tangible ...

-

Read more.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Viva Voce (NEW)

Please note exact requirements will vary across schools, and all analysis here is based on the sample assessment/support material from the NESA website

The Viva Voce is the first formal assessment task, worth 30% of your internal mark. It’s the only assessment carried over from the old course, so some of the information here is recycled from my original post.

The Viva is a 15-20 minute panel interview where you present your Major Work to your teachers and respond to their questions. It’s basically “selling” your MW and its concept: “hey, look at how great my idea is! This is the form it’ll take, here’s the research I’ve done so far, and this is how I intend to carry it out.” You will also need to submit your Major Work Journal for review.

According to the sample assessment material on the NESA website, the presentation could include the following:

A thorough explanation of the purpose, audience, context and form of your Major Work

Acknowledgement of the sources you have used in developing the proposal and inquiry question

An outline of your plan to complete the Major Work project including a timeline

References to your journal to assist in explaining choices made and research completed.

Before I unpack the above, I want to briefly address concept. You obviously need to explain to the panel what your MW is about, but concept also underpins your understanding of purpose, audience, context and form. I have other detailed posts on developing a concept, but for our purposes here I just wanted to highlight concept as key to how you explain everything else required of you in the Viva.

Explanation of purpose, audience, context and form (+ concept) of your MW

While it’s important to explain each of these individually, it’s just as (if not more) important to link them together.

Purpose: Basically what you’ve set out to do with your MW. At this stage, it should not be something bland like “I aim to entertain my audience” or “I want to make people think”. Literally anybody could say that about their major. What is it that you want your MW to do specifically? What is the “conceptual purpose” of your MW, if you will. You might like to start out brainstorming a list of verbs, or thinking about the messages/themes you want to explore in your major.

Audience: Who is your Major Work intended for? Which group of people will respond to your major in the way you want them to? Again, broad answers along the lines of “the general public”, “high school students”, or “young people” won’t cut it. You need to delve a little deeper. Running with the last two examples, it’d be more “high school students who are highly active on social media” or “young people frustrated with their experience of the political system”. Specificity! It’s your friend.

Context: To quote the NESA glossary, context is “the range of personal, social, historical, cultural and workplace conditions in which a text is responded to and composed.” Replace “text” with “major work”, focus on “composed”, and you’ve got the gist. You need to be aware of your context (how your MW links to Advanced and Extension, for example) AND situate your MW in its context, e.g. a critical response on female journalists in WWII would require some knowledge of wartime reporting, government propaganda, censorship, attitudes towards women in journalism, etc.

Form: Most obviously, what is your form? And why have you chosen it? I’m not sure as to how detailed an answer teachers expect from the second question, but you should have some idea beyond “I like it.” This is where tying form to the other elements becomes important. What makes your form the most appropriate for your concept, purpose, and audience?

Putting it all together

Running through every permutation of purpose, audience, context and form would take far too long, so I’m going to limit this section to the relationships I personally find to be the most important. Please note that I’ve chosen to pair the elements for simplicity’s sake, but they all feed back into and overlap with one another.

Form and audience

Let’s say your major is a short story. Your intended audience would obviously not be film critics or even people who enjoy watching films. In other words, your intended audience should be directly related to your chosen form.

But there should also be a consideration of how your concept factors in: for example, why did you choose poetry to explore environmental activism on climate change? It could be because poetry is a strongly emotive form, and climate change is an issue that rouses great passion in your intended audience of green activists seeking new, culturally relevant ways to express their concerns around the consequences of failure to act on this issue.

(Btw there’s no shame in saying that you chose a form because it means a great deal to you personally! Familiarity with and fondness for a particular form is a perfectly legit reason to choose it. Just that it can’t be the only reason.)

(I pulled that poetry/climate change example from thin air, but turns out it’s a real thing.)

Audience and purpose

Your understanding of one is shaped by the other, the why of your MW informing the who and vice versa. Just as you wouldn’t buy someone a gift you know they’ll absolutely hate, you wouldn’t create a MW for an audience unlikely to appreciate it.

Say your major aims to deconstruct the Manic Pixie Dream Girl trope in science fiction film and encourage change in the way women are represented in this genre. Film critics and/or cultural studies academics might be interested, but they’re not in the best position to push for change. A better fit would be, say, directors and producers working in the sci-fi genre who are interested in subversive or transformative gender narratives.

Form obviously plays a part here too, since you may have decided a podcast is the best way to reach your affluent and online audience.

Form and purpose

Why is your form best suited to doing the thing you want your MW to do? Or to quote from the NESA description of the Major Work: “The form of the Major Work must be chosen deliberately to contribute to the authenticity, originality and overall conceptual purpose of the work.”

To go with my sci-fi example from above, deconstructions of popular tropes are very well-suited to critical responses (and academic audiences). But as I noted, the purpose of encouraging change in the film industry demands a more visible platform that you’d get with a podcast. If, however, you were more interested in deconstruction-through-satire, a short story or short film would be the better choice.

Acknowledgement of the sources you have used in developing the proposal and inquiry question

It should be self-evident, but bears spelling out in full: cite specific sources. “I read an interesting article online” isn’t as strong as “I read an Atlantic article about how teenagers use Instagram to debate the news, which informed my thinking about the ability of social media to polarise, and the evolution of news consumption among young people.” Let the extent of your independent investigation shine! Show off the knowledge you’ve accumulated! Own your research, basically. (Also ironic in that you’re acknowledging other people’s work, but you get what I mean.)

It wouldn’t hurt to link those specific sources to your proposal and inquiry question. I don’t know how thoroughly you’ll be expected to explain those links, but something like the following would be a decent example: “This Atlantic article helped to narrow the scope of my inquiry question about the impact of social media on news-gathering behaviour to young people, instead of everyone.” The key thing is to at least mention various sources and show the teachers you’ve actually been doing relevant research.

Action plan outline, including timeline

Hint: structure your plan in relation to the composition process. Obviously, the particulars are going to be specific to your major. But be realistic in your planning. Try to strike a balance between micromanagement and no time management at all: while you don’t strictly need to break the entire EE2 course up into minuscule steps like “week two: write the opening scene”, it’s also not helpful to say you’ll tackle the entire investigating stage in January. To reiterate: the points under each stage of the composition process provide a good guide for your action plan.

Be aware of your own and others’ limits too! If you know you’re a serial procrastinator, can you really crank out a first draft in three weeks? Will you be able to secure feedback from your learning community in the week before an assessment block? You also need to account for any other Major Works you’ve got and remember the workload from your other subjects. How will you fit EE2 around them? There’s nothing wrong in keeping your timeline tight, a kind of platonic ideal to which you aspire, but it shouldn’t be so unrealistic as to be impossible.

I say it in my guide to the composition process, but remember that your action plan will likely change throughout the year. Life happens! Something might happen in your personal life; you could come down with the flu; maybe a friend is late in getting their feedback to you, and you find yourself falling behind schedule. It’s not the end of the world. You can adjust your action plan as you go - working around obstacles is part and parcel of EE2.

References to your journal to assist in explaining choices made and research completed

You should be able to point to specific entries in your journal to explain why you made a decision, which is a good time to remind you to keep your journal up to date!! Back-filling entries is a pain but also procedurally unsound, since you can’t return to your state of mind and exact train of thought when you made a decision.

Preparing for the Viva

You’ll be given the questions 15 minutes beforehand, but that doesn’t mean you can’t prepare. Make sure you are familiar with and prepared to discuss your major’s concept, form, purpose, audience and context (particularly links to Advanced and Extension coursework).

If you’re still in doubt, the old English Extension 2 Support Document includes a handy list of starting questions, a sample of which I’ve copied below:

Concept

What concept have you developed for your Major Work? Describe it.

Why are you interested in this concept?

What are your sources of inspiration?

How is your concept an extension of the knowledge, understanding and skills developed in English (Advanced) and (Extension) courses?

Purpose

What are you aiming to achieve during the Extension 2 course?

How are you planning to achieve this purpose?

Form

Have you decided on the form in which you would like to compose?

Why have you chosen this particular form?

Intended Audience

Who is the target audience of your work and why?

The questions you answer in the Viva will be different and/or tailored to your MW specifically, but the list above broadly covers the things you’ll be asked. You don’t need to write an entire essay in response to each question; dot points are fine. The Viva is not a speech, so your language doesn’t need to be as formal.

Practice, practice, practice

If you’re worried or anxious about fronting up before a panel, I recommend doing a practice run with a close friend. Grab your notes, MW journal, a stopwatch, and someone you trust, then get them to pitch you the list of questions you’ve prepared for. Use the stopwatch to keep yourself within 15-20 minutes. Practicing will build your confidence and familiarity with your notes, as well as help you cut down on any waffle you might be inclined to.

During the Viva

The preparation is one thing, communicating what you’ve prepared to the panel is another. Of course, a lot depends on who the teachers are, how comfortable you are with them, your own confidence levels, etc. I can’t really help you there. All I can suggest is that you try to convey your interest and enthusiasm to the panel. It’s your project, and you want it to succeed. Channel some of that passion into the way you present your MW. You’re pretty much stopping short of grabbing each teacher by their lapels and yelling LOOK AT THIS FANTASTIC IDEA I HAVE.

The teachers will ask you questions related specifically to your MW, ones which are spontaneous and based on their understanding of your MW as you’ve presented it to them in the Viva. Again, try not to stress. The teachers are not looking for ways to trip you up, they’re helping you to think about the direction your MW could take. One of the most important things you’ll learn from the EE2 course that isn’t mentioned in the learning outcomes is taking criticism. It’s about being able to accept (reasonable) critique of your work and striving to improve those areas, as well as exercising control over your creative process, i.e. not taking absolutely every single suggestion put forward unless you truly believe they’ll all benefit you.

Post-Viva

When you get your marks back there should be comments as well, like suggestions on what you could be reading, or questions that might help you orientate the direction of your MW. Take these on board, and discuss them with your English teacher(s) as soon as possible. The assessment tasks are certainly there to assess you, but they’re also ways to keep you on track and help you to make your MW better. (Keep in mind what I mentioned above about taking criticism/feedback.)

#viva voce#assessments#my posts#hsc#english extension 2#this got very long#im sorry for everyone on mobile

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ritual Magic at the Museum of Witchcraft

I returned from the UK at the end of last week after attending the annual Museum of Witchcraft and Magic conference in Boscastle, Cornwall. The conference, which I attended last year, continues to grow from strength to strength. This year's theme was Ritual Magic, and the range of talks delivered really showcased how a great title like this allows speakers to bring a refreshing variety of approaches to such a topic. This also linked the conference to the current exhibition “Dew of Heaven: Objects of Ritual Magic” running until October 31st 2018.

As always, there is so much to be said, and so I am just going to summarise some of my favourite papers. I apologise to any speakers who feel I have grossly misinterpreted their key points. Any errors or over-emphases are mine and mine alone!

Dan Harms' talk, A Liverpool Cunning Man and his Magical Manual, took us into the eccentric consultation room of William Dawson Bellhouse, a nineteenth-century "surgeon, professor, and astrologer" whose cunning craft was melded with Bellhouse's interest in Galvanism and the potentially therapeutic effects of (hopefully mild!) electric shock treatments. Charting those bizarre overlaps of medicine and entertainment, Bellhouse's magical practice seems a fascinating admixture of the techniques and services of traditional English cunning folk and the instrumentations of the new sciences. Of particular interest to me was the rundown of the library of one technically unnamed cunning man operating in the area whom Harms seems sure refers to Bellhouse himself. The books used by this nineteenth-century practitioner should be very familiar to the early modernist and those interested in this kind of British folk magic: Agrippa's Three Books, the Fourth Book, Scot's Discoverie of Witchcraft, Hiebner's Mysterium Sigillorum and a whole host of charms only thus far found in manuscripts. Dan ended by sharing an incredibly detailed list of ingredients and instructions for constructing a witch-bottle which - beyond the usual urine and pins - included dragon's blood, "devil's dung" (i.e. asafoetida), and other choice materia magica. You can listen to the whole talk right here.

My other highlight of the first day was undoubtedly Peter Grey's poetic reflection The Shining Land: Ritual Magic in Cornwall. Not content to simply be a report on what makes some kind of "authentic Cornish magic", Grey's narrative exposed the very modern folly of such an attempt at constructing such an authenticity at the expense of the actual storied, cross-sectioned, and re-storied history of that land. More than a summary of all the magical things of Cornwall - and there are undoubtedly many! - it was a profoundly moving and potent meditation on the importance of place and the land in any magical practice. Those familiar with Grey's Apocalyptic Witchcraft should hardly be surprised by this, but the manners in which engagements with terroir were modeled in this piece were especially inspiring. I was personally delighted to discover Paracelsus' work in Cornish mining communities directly fed into his Book on Nymphs, Sylphs, Pygmies, and Salamanders, and to hear Peter's rendition of the Prayer of the Gnomes - a prayer I use heavily in my geomantic consultations - was a particular treat.

The evening's entertainment came in the form of my dear friend and Golgothan co-host Jesse Hathaway Diaz of Wolf & Goat giving an extended and interactive presentation on Quimbanda. As precisely no-one familiar with Jesse and his work was surprised to discover he effortlessly introduced this Afro-Brazilian witch-cult, grounded it in its historical and social contexts, before going onto explore the influence and contribution of European grimoires to this particular melting-cauldron of a necromantic tradition. There was singing, a lot of laughter, some shocked gasps, and plenty of excited chatter about it all in the bar afterwards. As is only proper.

It is said on this night that candlelight filled the afterhours Museum and the sound of rum-fueled carousing might have been caught on the wind. But who can say...

My two favourite papers delivered the following and already-upon-us final day of the conference were undoubtedly those of Tim Landry and Peter Mark Adams. Anthropologist Tim Landry gave an absolute tour-de-force in his presentation Willful Things: Sorcery and Encountering Ritual Magic in West Africa and Beyond. The task ahead of him - of introducing and contextualising the key epistemological and ontological differences between a European approach to magic and a West African approach to those activities and engagements sometimes characterised as equivalent - was not straightforward. Yet Tim demonstrated both great depth and clarity of analysis in presenting how West African modalities of sorcery impact on everything from basic social provisions to efforts to protect endangered species. Ending his talk on a definite high, Dr Landry posited that to examine this material and these practices responsibly we should move away from considering ritual magic as the manipulation of some emanated symbols in a (Neo)Platonic idealist universe, and towards a recognition of sorcerous potency in that which could be biologically dead but still ontologically alive. That, moreover, we benefit from considering ritual magic less as dealing in symbols, and more in terms of entering into relationships with non-human persons. I could not have applauded harder and more vehemently.

My final favourite was Peter Mark Adams' wonderful presentation on the Sola Busca tarocchi deck. While I have a copy of his excellent Game of Saturn, I must admit I have not worked my way through its entirety: this paper definitely highlighted the broader, deeper, and more practical utilities of his voluminous research into this elite Renaissance Italian Saturnine cult. Adams' work indicating and assessing the history and utility of ritual gesture alone was worth the price of admission, and his case-studies of but a few of the beautiful cards of this deck were so captivating there was an audible room-wide sigh of disappointment that the ride was over when he announced his last slide. Peter's conception of different levels of analysis - the historical, the alegorical and the magical - "trapdooring" down into further levels of each other has certainly given me plenty of methodology to muse on in my own work.

And speaking of my own work, I was very pleased to be able to present my paper on Ritual Magic of Early Modern Geomancy. This essay combined specific and general attitudes. In the case of the former, I sought to make assessment of geomancy's specific sorcery, considering especially the talismanic and semiotic consequences and utilities of Agrippa's assessment that geomantic figures and their sigils fell "betwixt images and characters". In service of the other, more generalist goal of this paper, I attempted to ruminate more broadly on ritual magical interrelations of all forms of divination and operative sorcery: how categories of divination become tools of enchantment, and how the lots of fate can be not simply read but re-written.

Threading these various presentations together like pearls on a tightly woven cord was Judith Hewitt of the Museum staff, framing these talks within an ongoing and unfolding revelation of the relationship between the Museum's founder Cecil Williamson and the work and disciples of Aleister Crowley. Owing to a last minute cancellation, Judith stepping in to fill the dead air and actually got to present and develop some of her own notions and questions of how Williamson considered and used the Museum, and this kind of critical reflexivity upon the Museum's own alchemical and thoroughly magical existence and operation was a perfect conclusion to a wonderful and expertly run conference.

I will continue to recommend the conference to anyone who can get a ticket quick enough! Long may it continue to pull practitioners, scholars, and seekers together under its sign to share their thoughts, their secrets and their rum! Long may it continue selling the wind!

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

The first.

The nice thing about blogging is that one doesn’t need to follow a strict academic essay structure: the issues and concepts I want to write about are always architectures built upon some underlying causal, foundational plot. It would be nice if we could hyperlink the written representations of our thought processes, but alas, that is one domain in which modern technology has fallen short. You might see that I jump around between topics, but I promise there are connections everywhere. So, here we go!

I’ve been hesitant to write about what ignites my passion the most.

There are a couple of reasons for this.

For one, save for some semblance of a university degree I attempted to put together years ago, I have little in the way of ‘respectable’ credentials. I rely on my own observations of what is happening around me. A high school friend once revealed to me a technique in visual arts that has stuck with me since. “Draw what you see, not what you know to be there.” I have applied this not only to achieve realism in the scant visual artworks I have produced and which have gone unseen by most others, but also to compose a coherent understanding of my world--or in other words, everything I feel. This “motto” of sorts shows that we often ignore details about our experience that are in plain sight. Despite holding this key, I am well aware that I have not necessarily earned any institutional authority to write on the matters that compel me so--yet, as a person who has simply lived and observed, I still feel that I should express myself, for what ever it may be worth.