#Theodore Low De Vinne

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Typography Tuesday

More De Vinne Initials

This week we present a few more initials from Types of the De Vinne Press, published in New York by the De Vinne Press in 1907. The press was founded in 1883 by Theodore Low De Vinne (1828-1914), a co-founder of the prestigious Grolier Club and one of the leading commercial printers of his day, whose enterprise had a profound influence on American printing and typography.

De Vinne defines the initial as:

A large or ornamented letter at the beginning of a chapter or paragraph, as high as many lines of the text type by its side, and lining neatly with its first and last lines . . . .

He further states that "A proper initial at the beginning of a first paragraph always gives attractiveness to the composition. It is the feature that first catches the eye." These initials certainly do.

View more posts from Types of the De Vinne Press.

View more posts with initials.

View more Typography Tuesday posts.

#Typography Tuesday#typetuesday#initials#historiated initials#ornamental initials#De Vinne Press#Theodore Low De Vinne#Theodore De Vinne#Types of the De Vinne Press#type specimen books#type display books#type specimens#19th century type

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

point of pilgrimage

still standing, in lower manhattan’s noho district, is the edifice erected by nyc’s—if not the usa’s—greatest trade printer, theodore low de vinne, to house his printing establishment. who, however, is the «Thomas De Vinne» named on the plaque? perhaps, the name of a son was misattached, but no: de vinne’s surviving sons were theodore brockbank de vinne, & the younger charles dewitt de vinne.* surely the department of the interior has had sufficient time to correct this by now! * cf. irene tichenor, No Art Without Craft, david r. godine, boston, 2005, p65.

0 notes

Text

The invention of printing. A collection of facts and opinions descriptive of early prints and playing cards, the block-books of the fifteenth century, the legend of Lourens Janszoon Coster, of Haarlem, and the work of John Gutenberg and his associates. Illustrated with fac-similes of early types and woodcuts. By Theo. L. De Vinne.

Description

Tools

Cite this

Main AuthorDe Vinne, Theodore Low, 1828-1914.Language(s)English PublishedNew-York, F. Hart, 1878. Edition2d ed. SubjectsPrinting > Printing / History > Printing / History / Origin and antecedents. Physical Description4p.ℓ.,7-557p. front.,illus. (incl. ports.,maps, facsims.) 24cm.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Trans Rights Letterpress tag. Printed at SAIC letterpress studio using 48 pt Satanick Font. I genuinely kinda love this font and not just bc of the name. But it's such a hodgepodge of different styles and is such a cluttered mess. Established printer/ writer Theodore Low De Vinne described it as a "cruel amalgamation of Roman with Black Letters" which is sick af. it goes against so many font norms and I love it. I could've kerned it better especially between the G and H but oh well I really like how the gradient came out.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sowersby, Kris. “How Lettering Became Gendered and Why It Is Wrong.” Www.itsnicethat.com, 26 Oct. 2021, www.itsnicethat.com/articles/kris-sowersby-how-lettering-became-gendered-and-why-it-is-wrong-opinion-261021. [Accessed 5 Mar. 2024.]

drag queens typically exaggerate and dramatise female gender signifiers, which is superficially playful, but actually a fundamental critique of socially constructed ideas of gender norms and sexuality

older generations have grown up with a culture underpinned by binary gender roles and toxic masculinity

"Theodore low De Vinne was and remains a respected figure in the type canon. In 1892 he gave a talk at a printers convention, eventually published as Masculine Printing. He kicks it off with: “I call printing ‘masculine’ that is noticeable for its readability, for its strength and absence of useless ornament. I call ‘feminine’ all printing that is noticeable for its delicacy, and for the weakness that always accompanies delicacy, as well as for its profusion of ornamentation.”

"20 years later, during the ascendency of modernism, Adolf Loos delivered his famous lecture: Ornament and Crime. It was subsequently published and taken seriously as a manifesto for the new style. Loos wrote his polemic during the height of Art Nouveau in Austria. Like earlier criticisms of the Baroque being “morally corrupt”, Loos claimed ornament “immoral” and “degenerate”. An insidious picture starts to emerge: ornament is feminine, weak, useless, corrupt, degenerate."

despite work done by organisations and institutions, these attitudes remain

most people have been raised in the binary belief of pinks and blues

baby boomers were the first generation brought up on gender coloured clothing

marketing industries realised arbitrary colour gendering and personalisation made more money

there is the same issue in icons, 'male' icons are suggested to have sharp edges and 'feminine' icons to be rounded and smooth curved lines

typical masculine typefaces will be square or geometric, hard corners and edges which are blunt or spiky. these can also be serif fonts, like slab serif

typical feminine typography will be slim lines with soft curves and flowing shapes with lots of ornaments and embellishments with slanted letters

" “What is queer typography?”, he states: “Female, male, intersex, trans, personal, non-conforming, and eunich. I don’t think it’s useful to categorize typography this way, to examine or classify type according to gender, or the other way around – this isn’t valuable in today’s discussion about queerness. Gender is not a metaphor."

this is an interesting exploration of the history behind gendered type and is something i intend of referring back to when i start designing because it will help me to navigate gender in type and help me to inform decisions.

i might want to consider exploring making a gendered typeface for a community or movement of relevance.

0 notes

Text

While diving into some extreme eye boggling research I’ve realised I want to interview de vinne himself, well Theodore Low De Vinne.

He wasn’t inspired by the Victorian era at all.. his fonts were just used by typographers in this era aswell as designers today to create this type of Victorian” style...

DeVinne actually preferred simplicity over ornaments and creativity ... how strange, I guess I’ve led myself to a topic more simplified in design but more intreugung than i initially planned ..

5 questions asked and answered ... next up design time

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The bookplate of Theo L. De Vinne features a shield upon which are three open books as well as the Latin phrase “Aere perennius” which translates to “More enduring than bronze.” The bust of a woman and a man appear on either side of the shield. A garland of flowers and fruits frames the scene.

Theodore Low De Vinne (December 25, 1828 - February 16, 1914) was an American printer and scholarly author on typography. De Vinne was one of the founders of the Grolier Club, a private society of bibliophiles in New York City, in 1884.

This bookplate was found in our copy of Antoine Vérard (1900).

#bookplates#ex libris#bookmarked#found in a book#design#shield#books#open books#othmeralia#aere perennius#grolier club

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

デザイン論ノート12|翻訳|ウィリアム・A・ドウィギンズ「新しい印刷が求める新しいデザイン」(4)

…………

広告美術家のより良い制作のために

とはいえ、彼らはパフォーマンスを向上させることができる。彼らは、不利な条件下で上手に働くチャンスがある。少なくとも販売用の印刷物が業者のメッセージを伝える一層明快で正確な媒体になるように、いくらかの負荷を与えることができる。彼らはゲームのルールを再学習する必要がある。預言者の言葉を彼らに聞かせて、彼らの方法を改めさせよう。彼らは、公正なタイポグラファーの活動領域で定められた道徳律を完全なものにする。

シンプルさを養うこと。文字のシンプルな形式とシンプルな配置を心がけること。

レイアウトの問題では、最初は美術を忘れて良識 common sense を用いること。印刷デザイナーの全責務は、メッセージを明確に提示すること──配置のあらゆる利点をメッセージに与えること──重要な主張を前に出し、重要でない部分を見落とさないように配置することである。ここでは、美術でなく良識の���践と分析能力が要求される。

印刷プロセスと一致する写真を用意すること。印刷機のインクと用紙は、明暗と色彩のためのしきたりである。しきたりの内にとどまること。

装飾、罫線、そのような装飾物は出し惜しむように使うこと。葬式の花のように飾り物を積み上げてはならない。余白 white spaces を計画すること──紙はまさに「絵の一部」である。印刷面の周りや内部の白紙の空間を操作して、心地よい形式 pattern を持つ領域をつくる���と。

活字の字体そのものの形態に慣れること。それらは、組み立てられていないレンガや梁など、新しい構造を構成する単位である。良いものを選び、それにこだわること。

ルールを策定するのは容易である。容易でないのはそれらを適用する場合である。実のところ、新しい種類の印刷には新しい種類のデザインが必要である。技術的方法における革命は完了している。古い方法はほとんど残っていない。この工芸 craft が始まって以来維持された良い印刷の基準は、突如取って代わられる。網点版、機械組版 machine composition〔自動鋳植〕、四色刷り、オフセット印刷、高速グラビア印刷など、新しいプロセスの複合体が印刷業者の手によって扱われなければならない。機械時代以前に維持されていた適切な印刷デザインに関する元々の概念は、これらの新しいプロセスとほとんど関係がない。紙の上のインクの刷りはまったく新しく異なったものである。

ある世代の印刷業者では、伝統の継続性に「断層」が生じた。アルダス〔Aldus Manutius、1449–1515〕、ボドニ〔Giambattista Bodoni、1740–1813〕、デ・ヴィネ〔Theodore Low De Vinne、1828–1914〕が用いた基準で訓練された精神でもって、この新しい印刷物をデザインできるだろうか? 私たちが良いと思っていたこれらすべてのことは、度を越してしまうことになるのか? 古い品質基準のどの程度が断絶を越えて引き継がれるのか、またそれが新しいモノの状態にどのように関連し得るのか? 手による植字は、手で糸を紡ぐのと同じくらい時代遅れになりつつある。機械組版は決着済みの事実である。古い感覚で良いものにするのはどうなのか? あるいは古い感覚は捨てるべきなのか?

もちろん、これらすべての質問に���えが与えられる。正しい方法がうまく行なわれ、新しい基準が発展する。強調すべき点は、新しい基準は機械的な基準だけでなく、美的な基準でもなければならないということである。美術家はそれを考え出す役割を果たさなければならない──美術サービスだけではなく、美術家が──ホルバイン〔Hans Holbein (子)、1497頃–1543〕とトーリー〔Geoffroy Tory、1480頃–1533〕という観点から見た美術家が。

(5)へ続く

0 notes

Photo

The Bumpy Typeface

Italian designer Beatrice Caciotti’s research shows us how gendered connotations have made their way into the genealogy of type design.

When gender is embedded into technical objects and processes, it not only reflects the gender norms of its society but also further reinforces these stereotypes. From hiring practices to the gendered naming of electrical sockets, certain ideologies are being actively reproduced through seemingly innocent everyday things and typefaces are no different. Italian visual designer Beatrice Caciotti’s research into this topic began when she noticed that logos of toys typically marketed for girls predominantly contained handwritten and twirly fonts, while on the other side had bold and sans serif lettering. “Currently, the relationship between typography and gender stereotypes is still scarcely addressed, and when it is it’s regarding marketing and thus audience targeting,” Beatrice tells It’s Nice That. With her Bumpy Typeface project, she decided to directly address this topic. “It is obvious that the use of gender attributes in the context of typography is not based on the lines drawn by the letters, but rather on cultural aspects.”

This designer/article addresses and summarises this issue really well and approached it in a similar way to me. The first line outlines how gender being embedded in things/processes such as typography reinforces gender stereotypes. The idea of gender ideologies being “reproduced through seemingly innocent every day things” (like typography) perfectly sums up my thoughts about the issue of gender binary in type - before learning about it type seemed so innocent and I didn’t realise it could hold and enforce stereotypes so powerfully. Her discussion on how toys marketed for ‘girls’ contained largely handwritten swirly fonts, while ones for ‘boys’ had bold sans serif type, addresses how gender stereotypes are seen in typography and how they’re not being addressed but rather used for marketing. “gender attributes in the context of typography is not based on the lines drawn by the letters, but rather on cultural aspects” is an interesting observation. Is it the form of the letters that implies gender stereotypes, or the context and culture behind the letters, or both?

Having written a master’s degree thesis on this topic, Beatrice’s research found that gender-specific attributes were already being used in typography since the early stages of design theory. “William Morris, precursor of design and design theorist, could not tolerate the modern aesthetics that came with the machine-made books of that time. In an effort to describe what he thought was wrong with the modern shapes and at the same time endorse pre-industrial typography, he stated that the modern lines were excessively ornamented, light, and feminine,” Beatrice describes. Morris advocated for a return to heavier, robust and darker shapes to reestablish the vigour of the printed page, thus linking a “feminine” typeface to weakness and listlessness. Another instance came from 19th century American printer Theodore Low De Vinne, who called for a return to “masculine printing.”

I think this is the first time outside of the Extra Bold chapter I’ve read about the history of gender binaries in typography. It makes sense that this is sort of how it began and where the associations came from. Not only did these actions separate typography into binary categories, but it begun the association of these ‘feminine’ fonts with weakness and fragility, as well as ‘masculine’ fonts with strength and permanency.

Beatrice found that more contemporary examples typically related to marketing products to a target audience where designers are prompted to understand these gendered differences in order to be able to sell to a certain gender. “The use of these fonts not only relies on outdated negative stereotypes about gender, but also reinforces the concept of a strict gender binary,” Beatrice says. For Beatrice, these stereotypes often become self-fulfilling prophecies.

Common to these examples is the idea that the letter is a metaphor for individuals in the society that they live in. Beatrice found that many existing projects that try to deal with the topic of typefaces and gender often take these stereotypes as a starting point and merely flip them around. “The view is just to mix and overturn attributes associated with gender,” she says of these projects. “Designing a font that simply and only flips the typical associations means adopting the corrupted perspective of the stereotype itself: if you’re not pink, then you are blue or vice versa, but what if I feel purple?”

It’s interesting to her an opinion on ways that gender binary in type has been addressed unsuccessfully/ineffectively. I think she's right that taking the original stereotypes and using them to build your font around is just further enforcing the stereotypes, even if you are just using them as an example of what to do the opposite off. Disregarding the stereotypes all together seems like the best approach.

Thus for Bumpy Typeface, Beatrice begins with the guideline that femininity and masculinity are culturally-restricted attributes, producing a typeface that reflects how difficult it is to be unaffected by the persistence of stereotypes in society. She decided on a variable font to contrast the “discriminatory limitations of the gender binary,” as well as a condensed typeface to express the external pressure of existing norms. “I created two masters that represent these two opposite ways of engaging with the surrounding context: one that adapts and conforms, adhering to the cage in its totality, and shaped with an edgy, axial and geometric shape. This was given a nominal value of 700 and the name Rigid. Whereas at the extreme opposite I designed a character with unexpected shapes, non conventional, fluid, giving it a nominal value of 300 and the name Fluid,” she says. “From the interpolation of these two extremes are born a series of variables, so that Bumpy in its variant 301 will be a bit more rigid than Bumpy 300. And Bumpy 500 is a variant that is halfway between these two extremes, adhering to the external grid and at the same time presenting non conventional elements. The decision to design a font family is a conscious decision in opposition to the limiting logics and discriminants of gender binary.”

Interesting to see her approach to addressing the issue of gender binary through typography. I gather that by creating a font that exists on a spectrum from one end of the binary to the other she is addressing how hard it is to escape these stereotypes, as well as showing how they visually manifest in type. One end is ‘geometric’ and ‘rigid’ - assuming masculinity, and one is ‘fluid’ ‘ assuming female. Or maybe on end represents being confined by the stereotypes and the other is breaking out from them? I interpret it as a depiction of the gender binary anyways. I think in my font I want to break and disregard the stereotypes rather than depict them. “The decision to design a font family is a conscious decision in opposition to the limiting logics and discriminants of gender binary.” communicates well my perspective on the responsibility of not enforcing gender binary through type design.

1 note

·

View note

Text

How lettering became gendered and why it is wrong - Kris Sowersby

https://www.itsnicethat.com/articles/kris-sowersby-how-lettering-became-gendered-and-why-it-is-wrong-opinion-261021

- Another really interesting take on gender/gender binary within typography/design

“Theodore low De Vinne was and remains a respected figure in the type canon. In 1892 he gave a talk at a printers convention, eventually published as Masculine Printing. He kicks it off with: “I call printing ‘masculine’ that is noticeable for its readability, for its strength and absence of useless ornament. I call ‘feminine’ all printing that is noticeable for its delicacy, and for the weakness that always accompanies delicacy, as well as for its profusion of ornamentation.”

20 years later, during the ascendency of modernism, Adolf Loos delivered his famous lecture: Ornament and Crime. It was subsequently published and taken seriously as a manifesto for the new style. Loos wrote his polemic during the height of Art Nouveau in Austria. Like earlier criticisms of the Baroque being “morally corrupt”, Loos claimed ornament “immoral” and “degenerate”. An insidious picture starts to emerge: ornament is feminine, weak, useless, corrupt, degenerate.

These primitive attitudes still permeate design thinking and conversation. Despite the good work done by many institutions and organisations to achieve gender parity and let the air out of stereotypes, they still linger on. Most recently in my orbit, Josie Young wrote about it in her post Gendered language in design. A creative director invoking how a logo is “too masculine” isn’t new, but that’s the point. “Most of us have been raised in a binary world of blues and pinks” writes Young, “so when it comes to describing the work we’re doing, of course we fall into those familiar patterns.” These familiar patterns are not benign. The masculine/feminine binary is corrosive for everyone because, “in a patriarchy, masculinity is considered superior to femininity.”

“The marketing industry figured out that arbitrary colour gendering and personalisation shifted more units.”

“Perhaps showing a bunch of people stereotypes, noting their response and re-promoting the stereotypes simply reinforces the stereotypes into a self-sustaining feedback loop of bullshit?”

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Typography Tuesday

De Vinne Ornamented Types

We return once again to Types of the De Vinne Press, published in New York by the De Vinne Press in 1907, this time to highlight some of the ornamented types offered by the press. It's wise to heed the warning that the incorrect use of ornamented type can sometimes be

An example of bad taste in superfluous ornamentation Printed work spoiled by needless ornamentation Fantastical ornament is disliked Simplicity most important.

You've been warned.

View more posts from Types of the De Vinne Press.

View more Typography Tuesday posts.

#Typography Tuesday#typetuesday#Types of the De Vinne Press#De Vinne Press#Theodore Low De Vinne#Theodore De Vinne#ornamented types#type specimen books#specimen books#type display books#type specimens#19th century type#uwm special collections

228 notes

·

View notes

Text

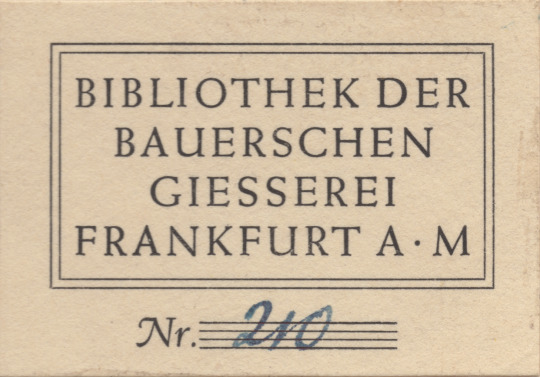

bauer bookplate

simple & tasteful typographical ex libris from the library of the bauer type foundry, frankfurt, germany. set in their weiss types.

i acquired the bauer type foundry library’s copy [after indeterminate journey] of that indispensable reference: A Treatise on Title Pages by theodore low de vinne; being the 1914, 2nd edition issued posthumously by the oswald publishing company, nyc. john clyde oswald, publisher of American Printer, after de vinne’s death obtained rights of publication to several de vinne publications, notably «The Practice of Typography» series. the 1914 oswald edition of A Treatise on Title Pages has a canceled title-page, & so was made up from sheets still standing at the de vinne press. the weiss types did not issue until 1928—cf. ‹vase 2›—thus giving terminus post quem for the volume’s entry into the bauer library.

#typography#ex libris#bauer’sche giesserei#bauer type foundry#theodore low de vinne#john clyde oswald

0 notes

Text

The invention of printing. A collection of facts and opinions descriptive of early prints and playing cards, the blockbooks of the fifteenth century, the legends of Lourens Janszoon Coster, of Haarlem, and the work of John Gutenberg and his associates. Illustrated with facsimiles of early types and woodcuts. By Theo. L. De Vinne ...

Description

Tools

Cite thisExport citation fileMain AuthorDe Vinne, Theodore Low, 1828-1914.Language(s)English PublishedNew-York, F. Hart & Co., 1876. SubjectsPrinting > Printing / Origin and antecedents Printing > Printing / History > Printing / History / Origin and antecedents. History NotePublished in five parts; with the last part cancels were issued to be substituted for p. 43-46, 369-370, 375-376 incorrectly printed, also the half sheet containing Contents, and Illustrations to be inserted between sig. [1] and [2], before the Preface. Physical Description4 p. l., [5]-556 p. incl. front., illus. facsim. 24 cm.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Que papelão!

Amanda Mussato, Fernanda Silva, Giulia Belchior, Luana Goldenberg AAQ- Materiais de construção - Rodrigo Serafino da Cruz

História, cronologia e desenvolvimento além do tempo (Amanda)

Fabricação→ Tipos, resistência, compensação, propriedades (Luana)

Meio ambiente, propriedades (Fernanda)

Arquitetura (Giulia)

Origem

Papelão, originado do latim papȳrus, significa papel grosso e rígido, com mais de 0,5 mm de espessura, com que são feitas caixas, capas de livro, pastas etc.

Tudo parece comprovar que o papelão surgiu na China entre 3 e 4 mil anos atrás, quando os chineses da dinastia Han começaram a usar folhas feitas de casca de amoreira para embalar e preservar alimentos.

Esse fato não é lá muito surpreendente, já que foram os chineses que inventaram o papel, também durante a dinastia Han. Pois esses materiais — papel, papelão e folhas impressas — gradualmente começaram a chegar até o Ocidente através da Rota da Seda e das relações comerciais estabelecidas entre a China e a Europa.

Fonte: http://www.miniweb.com.br/historia/Artigos/i_antiga/invencao_papel.html

A primeira menção ao papelão de que se tem notícia na Europa data do s��culo 17 e foi encontrada em um manual de impressão de Theodore Low De Vinne e Joseph Mixon chamado Mechanick Exercises — embora esse material tenha chegado muito antes no continente. No entanto, o livro não se refere a um tipo de papel utilizado para a produção de caixas, mas sim sobre o qual se podia escrever e imprimir.

A respeito às caixas propriamente ditas, a primeira menção é de 1817, quando elas começaram a ser usadas comercialmente, guardando um popular jogo de mesa alemão chamado Jogo de Besieging. De acordo com Matt, algumas evidências apontam para um industrial britânico chamado Malcolm Thornhill como o primeiro a produzir caixas feitas com uma única lâmina de papelão, mas, ainda assim, as informações são bem limitadas e incertas.

Fonte: http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O25924/the-game-of-besieging-board-game-unknown/

Sabe aquele “recheio” todo ondulado que tornam as lâminas de papelão mais firmes? Esse material foi inventado em 1856 pelos britânicos Edward Healey e Edward Allen, dois fabricantes de chapéus e estavam em busca de um material maleável, mas que não perdesse o formato.

Aparentemente, a dupla patenteou a invenção no mesmo ano e, em 1871, um norte-americano chamado Albert Jones recebeu a patente pelo desenvolvimento de uma nova forma de usar papel para embalagens que facilitava o transporte de produtos ao mesmo tempo que protegia as cargas.

Fonte: https://www.megacurioso.com.br/historia-e-geografia/66216-voce-sabe-como-foi-inventada-a-caixa-de-papelao.htm

Fonte: https://www.sashe.sk/Loora1/detail/papierova-krabica-kruh-vysoka-9x102-cm

Finalmente, as caixas no formato que conhecemos atualmente surgiram no acidente em 1879 graças a Robert Gair, o criativo dono de uma fábrica de sacolas de papel. Segundo Matt, até então, para fazer as caixas, os fabricantes pegavam as lâminas de papelão e marcavam todas elas com uma prensa antes de dobrar e fazer todos os recortes necessários à mão — o que resultava em um processo que, além de demorado, era bem caro.

Pois um dia, na fábrica de sacolas de Gair, um dos funcionários não percebeu que a prensa não estava regulada na posição certa e, quando foi acionada, acabou cortando milhares de sacolas em vez de apenas dobrá-las. Gair, no lugar de ficar bravo com o prejuízo, percebeu que poderia usar a mesma máquina para dobrar e cortar as lâminas e, ao substituir o papel pelo papelão e fazer algumas modificações, ele acabou desenvolvendo a produção em massa das caixas.

No início, Gair se dedicou à manufatura de caixas pequenas (para chá, tabaco e cosméticos), e, em 1896, o industrial fechou um contrato com a Nabisco para a fabricação de 2 milhões de unidades. E foi a partir daí que a produção em massa das caixas de papelão explodiu e se consolidou no mercado — e elas passaram a fazer parte de nossas vidas de uma vez por todas.

Fonte: https://www.megacurioso.com.br/historia-e-geografia/66216-voce-sabe-como-foi-inventada-a-caixa-de-papelao.htm

Estrutura

O papelão ondulado é uma estrutura formada por um ou mais elementos ondulados, chamados de “miolo”, fixados a um ou mais elementos planos, chamados de “capa”, por meio de adesivo aplicado no topo das ondas.

Ambas as partes são obtidas a partir de fibras virgens de celulose, matéria-prima renovável ou de papel reciclado

Tipos

O que diferencia os tipos do papelão é a quantidade de miolos e capas que cada placa possui. Assim como suas espessuras. Os principais tipos de ondulação interna são A, B, C e E.

QUANTIDADE DE ONDAS – em 10cm

TIPO A

ESPESSURA EM MÉDIA: 4,5mm

QUANTIDADE DE ONDAS ( em 10 cm) : 11 a 13 ondas

TIPO B

ESPESSURA EM MÉDIA: 3,0mm

QUANTIDADE DE ONDAS ( em 10 cm) : 16 a 18 ondas

TIPO C

ESPESSURA EM MÉDIA: 3,5mm

QUANTIDADE DE ONDAS ( em 10 cm) : 13 a 15 ondas

TIPO E

ESPESSURA EM MÉDIA: 1,5mm

QUANTIDADE DE ONDAS ( em 10 cm) : 1.38 ondas

Composição

O papel é feito através dos troncos das árvores. No Brasil, a principal espécie utilizada é o eucalipto, devido ao seu rápido crescimento. Apesar da grande reciclagem e reutilização do papelão, parte produzida no Brasil é feito com eucaliptos devido ao seu rápido crescimento.

Resistência

Como visto em nosso projeto, a resistência do papelão depende não só do seu tipo, mas também do sentido das nervuras trabalhadas. Nervuras trabalhadas no sentido vertical são mais resistentes do que no sentido horizontal.

Processo de Produção:

O papelão ondulado é fabricado em uma máquina denominada onduladeira, onde as ondas são fabricadas de acordo com o perfil do cilindro ondulador.

Para que as chapas sejam transformadas em caixas e/ou acessórios de papelão ondulado, são processadas em diversos equipamentos-impressoras, máquinas de corte vinco planas e rotativas, coladeira e grampeadeiras, vincadeiras e divisórias.

Devido ao custo benefício, o papelão é hoje o maior tipo de material usado para embalar produtos para transporte, etc.

Meio Ambiente

Por ser um produto de matéria prima sustentável, biodegradável, reciclável e geralmente feito através de energia de fontes renováveis.

Estima-se que atualmente mais de 70% do papelão produzido no Brasil é proveniente de material reciclado - um dos materiais que mais se recicla no país. Outro fator relevante é que a fabricação de papelão com uso de aparas gasta 10 a 50 vezes menos água que o processo tradicional - que usa celulose virgem - além de reduzir o consumo de energia pela metade.

Mesmo se houver descuido em relação a reciclagem do papelão, ele por ser biodegradável produz um impacto ambiental muito menor do que maioria dos outros materiais. Em menos de um ano o papelão pode está decomposto, desse modo não traz riscos à saúde humana ou dos animais, sendo que não contaminam solo nem os lençóis freáticos.

É importante analisar o processo desde a produção do produto para saber se ele é realmente sustentável, por exemplo na empresa alemã Hausberg os processos utilizados foram otimizados com o tempo. Maior eficiência energética na fabricação de papel foi alcançada através da otimização técnica em usinas de energia, máquinas de papel e alterando a estrutura de matérias-primas. A energia necessária para produzir uma tonelada de papelão caiu de 8.242 kWh / t em 1955 para 2.674 kWh / t em 2001.

A Organização Mundial de Alimentação e Agricultura (FAO) calcula o crescimento da floresta no hemisfério norte - onde são produzidas matérias-primas para embalagens de papel e papelão - a 5% ao ano. Só na Europa, isso corresponde a uma área de 1,5 milhão de campos de futebol. A rentabilidade desempenha um papel importante na produção e desenvolvimento do papelão, por isso é essencial se certificar de que a rigidez da embalagem economiza de fato recursos e atende a todos os requisitos. Uso praticamente exclusivo de adesivos à base de água e consumo de energia verde. A reutilização do papelão, também é uma saída que algumas empresas utilizam, é possível fabricar com até 90% de material reciclado.

Embalagens de papelão têm uma "pegada de carbono" extremamente pequena. Em 2010, o instituto ambiental sueco determinou que a produção de papelão e seu processamento no início até o fim produz apenas 234 kg de CO2 por tonelada. Isso leva em conta o armazenamento de carbono no produto e representa uma redução de 7% desde 2007. O consumo específico de energia por tonelada de papel foi reduzido em 16% através de várias otimizações de processo, como sistemas de feedback de calor. 53% da energia primária usada pela indústria de papel na Europa vem de fontes renováveis. Ao evitar fontes de energia fósseis não renováveis, como petróleo ou carvão, e o aumento do uso de biomassa para produção de energia, as emissões de CO2 na produção podem ser reduzidas continuamente. Ao redor do mundo, cerca de 85% de todo o papelão é reciclado, no Brasil estima-se 70% e nos Estados Unidos 95%. Sem esquecer que pode ser reciclado até mais de uma vez.

O processo de reciclagem é feito por meio de um triturador, que mói as fibras. Nela, adiciona água. Assim, essa massa é levada a uma centrífuga que separa as impurezas- grampos, durex, etc- do papelão. Então, produtos químicos são acrescentados para retirar a tinta ou clarear o produto. Depois de todo esse processo, a massa é colocada em uma esteira onde secará, e passará por novas máquinas onde sofrerá ondulações ou achatamento. Para 1 tonelada de papelão é necessário até 100.000 litros de água. Já no processo de reciclagem, é usado cerca de 2000 litros.

Nesses processos de reciclagem especialmente como exemplo no Brasil, não devemos deixar de lado os catadores de lixo que tem um papel muito importante.

Papelão na Arquitetura: Shigeru Ban

Entre muitos arquitetos que optam por diferentes materiais na sua construção, podemos destacar do papelão, o ganhador do Prêmio Pritzker de 2014, Shigeru Ban.

O arquiteto japonês é conhecido por ser especialista em estruturas de papel feitas com tubos de papelão ocos, porém fortes. Segundo uma entrevista de Andrew Barrie para o livro “Cardboard Cathedral: Shigeru Ban”, Shigeru afirma que “A qualidade da construção não depende da qualidade dos materiais. Depende da qualidade do espaço que é criado pelo volume, luz e sombra.”

Os tubos de papelão atraíram o arquiteto devido ao baixo custo, conservação da cor natural, facilidade de relocação e produzindo pouco resíduo, sendo utilizados como formas de colunas de concreto armado, implicando em um impacto menor ao meio ambiente. Muitos estudos estruturais foram feitos, assim como testes que resultaram na capacidade de impermeabilização, resistência ao fogo e água e detectou-se uma boa capacidade de isolamento térmico e acústico.

Suas estruturas baseadas em materiais recicláveis foram muitas vezes criadas para situações emergenciais, sendo na maioria das vezes, temporárias e de fácil relocação. Entre esses projetos podemos destacar:

Casas Paper Log - Kobe, Japão, 1995:

A fundação é constituída por caixas de cerveja que foram doadas e preenchidas por sacos de areia e as paredes são formadas por tubos de papel. As unidades são fáceis de desmontar e os materiais podem ser reciclados.

Igreja de Papel - Kobe, Japão, 1995-2005:

Foi construída após um terremoto destruir a igreja em Kobe, no Japão. Estruturada com materiais doados por uma série de empresas, e a construção foi concluída em apenas cinco semanas pelos 160 voluntários. A planta de (10 x 15 m) está inserida numa pele de papelão ondulado, e foi desmontada em junho de 2005, sendo enviado todos os materiais para Taiwan.

Escola Primária Temporária Hualin - Chengdu, China, 2008

Este projeto de colaboração entre as universidades japonesas e chinesas envolveu a concepção e construção de uma estrutura em tubos de papel para salas de aula temporárias na escola primária atingida pelo terremoto de Sichuan em maio de 2008. Foram os primeiros edifícios na China a portar uma estrutura de tubo de papel, e foram os primeiros edifícios escolares a serem reconstruídos na área atingida pelo terremoto.

Sala de Concertos de Papel - L'aquila, Itália, 2011

Devido ao terremoto de 6 de abril de 2009, a cidade recebeu a cúpula do G8. Shigeru Ban propôs construir uma sala de concertos temporários para apoiar a reconstrução da cidade. O objetivo era utilizar papel, que é fácil de montar e durável.

Catedral Cardboard - Christchurch, Nova Zelândia, 2013 (Prêmio Pritzker)

Após o terremoto de Christchurch, em 2011, a Catedral, símbolo da cidade foi destruída. Convidado para conceber uma nova catedral temporária, Shigeru utilizou-se de tubos de papel de igual comprimento e contêineres de 20 pés, configurando uma forma triangular. A estrutura tem vida útil de 50 anos, tempo necessário para a reconstrução da igreja de pedra original.

Aplicando o conhecimento

Bibliografia:

http://www.shigerubanarchitects.com/works.html

https://www.archdaily.com.br/br/01-185116/projetos-humanitarios-de-shigeru-ban

http://www.vitruvius.com.br/revistas/read/drops/14.078/5107

https://arcoweb.com.br/noticias/noticias/shigeru-ban-conclui-catedral-papelao-christchurch-nova-zelandia

https://www.galeriadaarquitetura.com.br/Blog/post/capela-de-papelao-foi-feita-para-substituir-igreja-da-nova-zelandia-destruida-com-o-terremoto-de-2011

Artigo EBSCO: Christchurch Transitional (Cardboard) Cathedral, Interview text by Andrew Barrie

http://www.papierverarbeitung.de/wpv/presse-und-service/infomaterial/Kampagnenbroschuere_natuerlich_verkaufsfoerdernd.pdf

http://www.hausberg-kartonagen.de/umwelt-nachhaltigkeit/a

http://procaixas.com.br/site/2015/12/22/beneficios-ambientais-de-caixas-de-papelao/

0 notes

Text

The Practice of Typography: A Treatise on Title-Pages

Theodore Low de Vinne. The Practice of Typography: A Treatise on Title-Pages. New York: Haskell House, 1972. ISBN: 0838309356. xx, 485 pp. 8vo. Many examples reproduced. Fine. Hardcover.

0 notes