#Then rejecting the fin could be considered a compromise

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

In the tags:

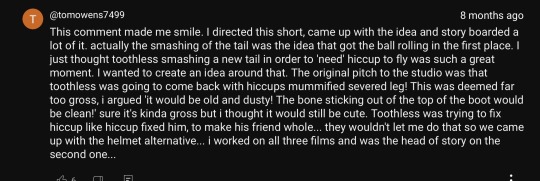

There is so much I love and agree with here. Your takes on reciprocity especially , and how the symbolism just works so much better, the story threads would feel more tied in. The story still seems built around this original, omitted idea.

In the story we got. Hiccup keeps slipping on his prosthetic which symbolizes that he needs Toothless.

But if the mummified leg wasn’t “cut” from the story, it would also motivate Toothless to bring him back the old leg that worked. Thus one idea would serve multiple functions, adding cohesion.

If I could add. The scene where Hiccup gives Toothless the new tailfin. To me Toothless’s reaction read as a bit conveniently overdramatic?

Toothless figures out what the tail and looks at Hiccup, eyes narrowing. Hiccup takes a step forward and Toothless flinches away before booking it.

Booking it to apparently, find Hiccup’s helmet. Which, you know, is very important, it was made from his mother’s breastplate and all - but to leave so suddenly your friend thinks you might be running away from him? It’s a lot.

I’ve heard the interpretation that maybe at first Toothless really was feeling the “call of the wild” the other dragons did. He just, couldn’t find another night fury so found Hiccup’s helmet instead. I don’t like this interpretation. But it seemed a little more in line with how the scene played out.

But if instead, you could read it like Toothless realizes what Hiccup has given him, that Hiccup has ‘fixed’ him, and is so overwhelmed (and mayhaps guilty), that he needs to, immediately, instinctively, fix him right back. Right the wrong of ‘failing’ to save his leg.

Well I can just see it a lot better. It would feel more in line with Toothless.

THE SHIT (GOLD) YOU FIND IN THE OCEAN (YOUTUBE COMMENT’S SECTION)

#that being said#I think there is a benefit to the helmet#besides it being less gross#sure there is less symbolism#and less cohesion#and importantly#there is less context for Toothless’s decision#to reject the new tail fin#which you can argue makes the gesture more powerful#because if Toothless brought back the leg#And Hiccup would have to say thanks bud no really thanks bud but I can’t actually#Then rejecting the fin could be considered a compromise#making up for failing to fix hiccup#by refusing to be fixed#thus not reflective of what toothless actually wants#but his guilt#while in the story we got#there is no such excuse#this is just what toothless wanted#what he would have always chosen regardless of the story’s events#he goes solo flying once comes back and says#the sky was lonely#and you were the tail I wanted#not that this wouldn’t have been present in the mummified leg timeline#but it would have been clouded

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

All Give

Ty watches Jim’s hands shake as he winds the compression bandage around Ty’s ribs. Ty holds very still, and tries to keep breathing deeply, and watches those hands tremble like they’re freezing cold.

It hurts to breathe, right now. He banged himself on the kitchen counter and his ribs are so sensitive these days, pain lurking constantly, ready to launch itself into an attack at the slightest provocation. He’d sat, clutching the wound, trying to keep the air coming in, for the hour and a half before Jim got home from work.

Jim is always exhausted, and Ty knows he doesn’t relax until he’s checked on him. If Ty is alright, he lets his tension go. If Ty has had a bad day, he doesn’t relax at all. He stays in work mode, businesslike, pushing down his feelings. He does everything he can to look after Ty without a word of complaint, night after night.

But he has tells. He has his hands, always shaking, as he tends to his husband. This is the third night in a row that Ty has had something, and the guilt is eating at him, watching Jim grow more and more resigned to giving up his relaxation time.

“How was work?” he offers, as Jim lets him go, ribs wrapped.

“Fine,” Jim mutters automatically, packing up the first aid kit. It’s a lie. Not conscious, maybe, but not honest either.

“You hungry?” Ty offers. There’s leftovers in the fridge, prepared last night for Jim’s late shift today. Another job on top of all the others, that Jim takes on for himself.

“No, I ate on the bus.”

The bus. Because Jim’s car is in for repairs. One extra weight on the camel’s back, not the last straw, not yet, but creeping ever closer.

“Jim,” Ty says, and he feels the stammer try and grab the single word and break it. He takes a deep breath. “Jim, can you sit down, please?”

Jim is halfway to the kitchen to return the first aid kit, the box that is stuffed with bandages and antiseptic and plasters and gauze and everything that it didn’t use to need, before Ty came home fragile and malnourished and so prone to overworking himself. He pauses, and Ty can see the reluctance in his shoulders and the way his body stays turned towards where he wanted to go. It was going to be his escape from this moment and a chance to breathe, compose himself, and layer over the exhaustion and frustration again so he can pretend Ty can’t see it.

Most days, Ty pretends with him. But most days he doesn’t have the time and energy and – clear-headedness, perhaps – to tackle it. He lets Jim go take care of himself, because he needs to do the same.

Not today. It’s the third day of this, and Jim is trying to avoid him.

“Sit down, please,” Ty requests, unable to keep the polite tone out of his voice. He’s halfway between his old therapist attitude and the nervous slave afraid to give orders.

“What’s wrong?” Jim says, finally sitting down on the sofa with a sigh of surrender.

What’s wrong, he asks, because when was the last time something wasn’t?

“I’m worried about you,” Ty tells him.

“Me?”

He nods.

Jim folds his hands, squeezing the shake out of them. “I’m fine, Ty, don’t worry about me. I’m just tired.”

“Tired of what?”

Jim doesn’t expect the question. “Work,” he says, blinking. “The usual.”

“Lots of things are the usual. I’m – this,” Ty gestures to his ribs, “is the usual. Are you tired of that?”

“No, no, I’m fine,” Jim repeats, and when he pauses, he meets Ty’s eyes. He sags a little, recognising he needs to give more. “It’s a lot, sure, but – it’s a lot for you. I just have to patch you up and stuff. Don’t worry about me.”

“Why shouldn’t I worry about you?”

Jim frowns. “Because you have to worry about yourself?”

“I can do both.”

“Really?”

Ty considers that. His instinct says there’s no reason why not. Worrying about himself takes most of his energy, yes, but when he has it to spare, he should be able to give some attention to his husband. Most days he has that, and it’s not enough to really get through Jim’s shell and use it... But he thinks he’s been storing it up. He knows they need this conversation.

So he doesn’t think Jim is right...but then, why does Jim say it? Jim knows how much energy you can give to others, he gives it to Ty every day, and it’s amazing, and Ty loves him so, so much for being willing to stick with him and not despair...

Jim doesn’t think people can worry about others and themselves.

Jim worries about others before himself. It’s been a constant worry of Ty’s ever since they got together. Jim is the kind of person who would make sure Ty had his life vest on before putting on his own, and if Ty asked him why, he’d get one of two answers. Things Jim has told him, in conversations like these. Things that Ty used to be able to tease apart and rearrange with him, before.

You’re more important, he’d say. The philosophical argument had worked on that one. No one person is more important than others. Everyone is equal in that. You deserve as much care and attention as I do, and you deserve it from yourself.

What if you can’t do it yourself? The other reason. Easier, in some ways, to counter. You don’t know that I can’t. You have to give me the chance to try, and while you do, look after yourself. When you’ve done that, if I’m still struggling, you can look after me.

Harder to reason with now that Ty can’t do so many things.

Jim has started to relax, thinking he’s deflected successfully. Ty rolls the words carefully in his mouth before saying them. “I can do both,” he reaffirms gently, “if you do both with me. When you need looking after, tell me.”

Jim doesn’t shake his head, but the look on his face is as good as a rejection. “I can’t ask you to help me.”

“Of course you can,” Ty returns. “I might not say yes, I might not be able to. But you can still ask. Why wouldn’t you?”

“Because it’ll stress you out!” Jim winces as he hears his own voice rising. “Sorry,” he adds, lowering it again. “Sorry, I just – I don’t want to burden you with it, Ty.”

He didn’t seem to realise how painful that was to hear. Ty scrunched his blanket in his hands, feeling his heart sting. “Am I a burden to you?” he asks.

“No. No! Never.”

“Then why would you be one to me?”

“Because it’s different! You have so much stuff, you need the help, you – you need to put yourself first, so you can get through stuff. I’m just – I’m just being selfish, it’s your issues that we’re dealing with.”

“In sickness and in health,” Ty says.

“That’s different, Ty, that’s – you get someone through sickness and it’s over and they’re better. You might not ever – you don’t need to ever get better, I’ll look after you every day, so just – let me do this.”

Ty breathes, and it hurts. It hurts his ribs and it hurts his chest, and his throat feels tight. It’s horrible, hearing how Jim feels about him. That he might not recover. That he might need looking after, every day, forever.

That’s not what Jim means...but it’s how it feels. And he’d say that, normally, he thinks – but today it would just start another cycle of guilt.

“Even if, if that were true,” he says, a compromise to his feelings, “you wouldn’t have to look after me. I kn-know it’s hard, I fin-nd it hard too.” He swallows again, willing the stammer to leave his words alone. “But we don’t have to, we can-n just, just leave it. Leave m-me. I’ll still be here tomorrow.”

“I can’t just switch off from you, I can’t just leave you—”

How many times, Ty wondered, would Jim describe his feelings with that minimising just?

“...and if I did, then, it’d just be – more work the next day.”

“Or I’d be okay,” Ty counters, as gently as he can with his voice shaking. “I’d m-manage, and be better when you wake up.”

“But if you’re in pain—”

“So are you,” Ty interrupted. “I know you’re tired, Jim, and you’re stiff and aching, just like me and my ribs. I can – I can do pain, I’ve survived a lot of pain. A few extra minutes of it while you eat or change clothes or just rest, that’s fine okay?”

“It shouldn’t be fine.”

“No, it shouldn’t, but – we can’t function on ideals.”

Jim is about to respond when the words really hit. When his brain catches up to what Ty said, his mouth closes, and he really thinks, this time. He stops and thinks, the way he has barely done.

Ty’s heart is racing and he hates the tension but he knows what Jim is thinking. Jim’s head is full of should – he should be better, he should be able to do this, he should be able to look after Ty without feeling exhausted and resentful and sad. He should be perfect. He should be everything.

He shouldn’t have his own needs.

“I...want you to be okay,” he admits slowly.

Ty tries to smile for him. “I will be. Just...not all the time. Even before, I wasn’t okay all the time, remember?”

Jim nods. They had their days. Bad days at work, or family drama, or the time his bibi broke her hip. Ty needed help then, and he needs it now, for very different reasons and in different ways, but...

“Okay,” Jim accepts eventually. “And the same goes for me, I’m guessing?”

Ty smiles. He wishes he could hug Jim, right now. “Yeah. You don’t have to be okay all the time, for my sake. You’re being all give, and – I want to give, sometimes, too.”

“I can’t make you—”

“You’re not,” Ty interrupts, firmly as he can. He needs to go and calm down, after this, his ribs hurt, but he can’t let that slide. “You don’t make me do anything, love. I do it because I want to, just like you want to.”

Jim sits for a moment, looking at his lap. Then, in a halting voice, he admits, “I...don’t always want to.”

“Then don’t.”

“But then you—”

“Will be fine. Not straight away, not easily, not without struggling, but that’s life, Jim, and you can’t protect me from everything. You shouldn’t try to. Let yourself fail, sometimes. Let yourself rest.”

Jim’s hand shakes as he wipes his eyes.

“Please, Jim.”

“O-Okay. Yeah, I – I get it, that’s, okay. You’re right, as – as always. I love y-you.”

The tearful smile Jim gives does wonders for Ty’s ribs. He smiles in relief. “I love you too. Now go to bed.”

#in which Jim is not okay#angst#exhaustion#emotional whump#my fic#ty#jim#crying#stammering#self-esteem

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

February 5, 2021: The Notebook (2004)(Part 1)

...Do I have to?

...The year was 2004. I was 13, my Mom was still into romance movies, and we had a Hollywood Video nearby. God, I miss Hollywood Video, you have NO idea. Anyway, I obviously didn’t watch this movie (or I wouldn’t be watching it now), but I do remember kissing in the rain...or was that just the DVD cover? Other than that, I got nothin’. Still, I like both Rachel McAdams and Ryan Gosling in other works, so I guess we’ll see.

I also can’t start this without acknowledging the fact that this is based upon a Nicholas Sparks book, and...I’m not into that. Sparks sucks, man. Sappy, overemotional, and constantly predictable folderol.

OK, Nicholas Sparks, let’s get this over with. SPOILERS AHEAD!!!

Recap

We start with scenic shots of a boat rowing through a marsh, being visited by a flock of snow geese. As they fly off, an elderly woman (Gena Rowlands) looks out of a window over it. The woman is in an old-folks home, and is visited by Duke (James Garner), another resident. He’s here to read from a book, despite it not being a “good day,” according to the woman’s attendant.

The story in the book begins on June 6, 1940, at a carnival in South Carolina. There, Noah Calhoun (Ryan Gosling) sees Allie Hamilton (Rachel McAdams), and it’s infatuation at first sight. He’s a lumber yard worker, and she’s a rich heiress. He’s also EXTREMELY forward, and she’s EXTREMELY not interested. He approaches her for a dance (at a...carnival), and she says no, having literally never seen this guy before. He responds to this rejection by...butting into her date with another dude of a Ferris Wheel?

And when she once again rejects his offer for a date...he, uh...he threatens to kill himself off of the Ferris Wheel?

Um. Yeah, no. That’s a new level of manipulation. She pants him on the Ferris Wheel and humiliates him, but JESUS CHRIST, this dude is a lot. That’s compounded the next day, when he continues to pursue her, and she continues to be EXTREMELY not interested! DUDE. GET A GODDAMN CLUE HERE, she is NOT INTERESTED IN YOUR SHIT.

Is Noah the first simp? Because he’s really starting to seem like it. Anyway, Noah and his friend Fin (Kevin Connolly) basically set her up to go on a double date with Noah, and he continues to be overly forward. Maybe this is supposed to be romantic, but it definitely doesn’t feel like it to me.

We find out that Allie is a quite well-educated young woman, whose schedule is basically completely controlled by her parents, who want her to go to college as well. Noah questions why her life is so restrictive, nothing that she should be free, which she insists she is. He then lies down in the middle of the road, watching the street...lights…

Holy shit, he’s a manic pixie dream boy. HOLY SHIT HE’S A MANIC PIXIE DREAM SIMP. He does all these quirky things, and breaks the girl in the restrictive lifestyle out of said lifestyle. Even if his dumbass actions nearly get him and Allie killed. See, she lies down in the street with him, and they nearly get run over by a car. And this second near-death experience is apparently SO romantic, that Allie’s won over, and they...just dance in the middle of the street. Because Ryan Gosling has no idea where to dance, apparently.

Billie Holiday sings “I’ll Be Seeing You” in the background (which, yes, I love), and we cut back to Duke reading to the elderly woman, who correctly guesses that they fell in love. And yeah, they go head-over-heels, apparently. Which is symbolized by, just, the most graphic of PDAs over, lord.

Allie meets Noah’s father, Frank (Sam Shepard), a seemingly nice man and poetry fan (he’s a Tennyson man apparently). He asks her if she wants breakfast-for-dinner, and he’s my favorite character so far.

However, as if to set up the conflict to come, we’re reminded that this is a summer romance, and that they come from two different classes and worlds. Because of course they do, but whatever, moving on. That is when the following scene takes place.

youtube

...Look, I’m a bird guy by trade, and even I think that was weird.

We get more glimpses of their romance, including them dancing at a gathering with...a bunch of black peopNOPE. HOLD YOUR TONGUE, 365, WAIT FOR THE REVIEW TO TALK ABOUT THAT SHIT. At the end of this montage, we meet Allie’s father, the uppity and rich John Hamilton (David Thornton), and his GLORIOUS mustache (mustache).

He invites Noah to Sunday brunch, which is being attended by...black servaHOOOOOOLD. NOT NOW 365 NOT NOW. We also meet Allie’s controlling mother, Anne Hamilton (Joan Allen). When Noah tells them how much money he makes, they immediately look down on him and his poor, poor ways. Anne reveals that Allie is headed to Sarah Lawrence, an all-girl’s school in New York. Which is, uh...NOT close.

Anne very much disapproves of her relationship with Noah, seeing him as a low-born of little consequence. Not that it matters, because the two head to a DEFINITELY HAUNTED house in the woods one night, which overlooks the marshlands. The bats from the Scooby-Doo intro fly by as the two walk in to, again, AN ABSOLUTELY HAUNTED HOUSE. This is the 1772 Windsor Plantation, home to...the Swamp Fox? Huh. Didn’t expect a crossover with the Mel Gibson movie The Patriot, but OK then.

The two talk about their house in the future, and somewhere in the house, a painting’s eyes move mysteriously. Allie plays a tune on the piano, which 1) sounds AMAZINGLY creepy, and 2) I’m pretty sure is the opening song, which is a neat touch. Guess that’s the theme for the movie, or possibly Allie’s leitmotif.

Anyway, it seems that the ghostly wails of Old Man Marion have gotten them both all hot and bothered, and they prepare to make love, right there in the old haunted house. The two undress while social distancing, then approach, significantly raising their risks of contracting COVID-19. Allie is CLEARLY very nervous, and as they attempt to begin the dirty deed, Allie can’t stop rambling about the current situation. Which is clearly putting Noah off the mood, but the two still clearly care about each other. It’s weirdly sweet, considering the fact that there’re, like, 50 ghosts watching, and God knows how many of those are slaaaaaaaAAAANYWAY

Fin suddenly bursts in, as it would appear that Allie’s parents have every policeman in town looking for her. Her parents are clearly upset, and her mother demands that Allie stops seeing Noah, whom she literally describes as “trash.” Jesus. And they aren’t exactly quiet about it, as Noah hears the entire conversation. He understandably leaves, and is also clearly disheartened by the whole situation.

When Allie catches up to him, he says he has to think about this whole thing, including the fact that she’s going to Sarah Lawrence, and he’s staying behind. And I’m not gonna lie, he’s actually being realistic about this whole thing, and she’s acting FAR less rational. She actually breaks up with him right then and there, and as she’s literally physically assaulting him, I realize that SHE is actually the psychologically unstable one, HOLY SHIT. Emotionally compromised or not, Allie goes BONKERS here.

The next day, her folks decide that they’re leaving, that very day. Allie doesn’t want to leave without making amends with Noah, and she’s regretting her actions the previous night. She goes to Fin, and tells him to tell Noah that she loves him, and that she’s sorry. Noah shows up a little too late, and goes to return the comments, but Allie’s already gone.

Noah somehow gets her address, and writes her 365 letters, one letter every day. He never gets one in response, so he gives up and moves with Fin to Atlanta. Allie’s mom is seen getting the mail, so we know EXACTLY what happened to those letters. Meanwhile, it’s now 1941, and it’s time for World War II for the USA! Fin and Noah fight with Patton’s troops, and Fin doesn’t make it.

Allie, meanwhile, is in college, and works as a Nurse’s Aide for war veterans. She sees all of them as Noah,,,which is weird because she hasn’t gotten any of his letters, so she wouldn’t know that he went to war, but whatever. One of these injured men is Lon Hammond, Jr. (James Marsden). And...aw...AWWWWWWW. Did I just type James Marsden? GODDAMN IT HE’S GONNA GET CUCKED

James Marsden seems to have only one role in movies, and that’s to be overshadowed by another dude, even though in many instances, he’s a totally fine guy. The X-Men films, Superman Returns, Enchanted, the Westworld series in a way, TELL ME I AM GODDAMN WRONG. Dude’s always in movies where he plays the love interest to a girl, and that girl is pursued by another guy, and he ALWAYS LOSES TO THAT GUY. You could argue that Cyclops in the X-Men escaped that fate, but need I remind that first, Jean died, and then she came back AND KILLED HIM. STOP SCREWING OVER JASON MARSDEN’S LOVE LIFE, MOVIES!!!!

Seems like we’re once again headed down that path, though, as the very injured Lon asks Allie out on a date while in recovery, then takes her out once he’s healed. And, since he’s about as forward as Noah was, but less crazy when asking her out, she falls in love with him quickly. And it’s Duke that makes that assessment, not me. And, OF COURSE, he’s a rich Southern boy, meaning that her parents are going to approve.

At a dance club in the city with...black performDEAR GOD IT’S GETTING HARD TO HOLD ON BUT I GOTTA DO IT MOVING ON

He proposes to her, with her parents’ full permission (of course, because he’s rich and southern, gross), and she gladly accepts. He jumps on stage and announces to the entire club that they’re getting married. However, she’s still missing Noah subconsciously.

Speaking of, Noah comes home from war, presumably in 1945, and finds that his father sold him the house in order to buy the Windsor Plantation. Around the same time, Noah finds out that Allie’s moved on, and is with Lon. So, what does he do? The only logical thing: he restores the entire plantation by himself in order to win Allie back FUCKING REALLY?

Dude, you rebuilt an entire house on your own, your father died, and you could EASILY get rich off of selling the house and continuing to restore other derelict properties in the area! Upwards mobility, my man! You don’t even need to stay in town anymore! Hell, THAT’S a better plan to win both Allie’s AND her parents’ approval! STOP SIMPIN’, AND IF YOU’RE GONNA SIMP, DO IT RIGHT!!!

He’s also sleeping with a war widow, Martha Shaw (Jamie Brown), and STILL thinks only of Allie, and her sweet, sweeeeeeet bathwater, probably. Speaking of, Allie’s trying on a wedding dress, when she sees a photo of Noah in the paper in front of the plantation, which certainly shocks her. Confused, she goes to see Lon at his job as a stockbroker, and laments to him her lost romantic whimsy, brought up by seeing Ryan Gosling (AKA a natural response). She tells him that she’s going to Seabrook to “clear her head.” Lon asks if he should be worried. She says no. SHE LIIIIIIIIIIES.

Halfway mark, and this is a good place to cut! See you in Part 2!

#the notebook#nick cassavetes#ryan gosling#noah calhoun#rachel mcadams#allie hamilton#james garner#gena rowlands#james marsden#kevin connolly#romance february#user365#365 movie challenge#365 movies 365 days#365 Days 365 Movies#365 movies a year#supernovass#sincerelygabby

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Carisi-centric thoughts on Eps 18x20, 18x21

I'm glad that's over.

Overall Thoughts

This was an intense but unnecessarily convoluted episode. This case could have been solved in fifteen minutes, not two hours. At least it wasn't another "rich white people he said/she said," and all the characters got their moment to shine, but I can't say I enjoyed it. It wasn't bad, it just kind of dragged. There was no need to stretch this over two episodes. The squad had to track down about twelve different witnesses to the same crime. Eliminate a couple of those witnesses, a few of the racist rants, and a Hallmark moment or three, and you'd have one tight finale.

Benson's Dilemma

I have to start here.

The characters kept saying it, but I don't see what was so different about this particular case (other than the fact it was not about rich white people). Hate crimes happen every day. So do rapes and murders. Why would Barba suddenly decide to urge Liv to lie on the stand? That wasn't just random and out of character, it wasn't supported by the script.

If they needed Barba to do that to create tension between himself and Liv, if they wanted to make Liv look better by comparison, and more ethical than Barba, they needed to set it up better. I mean, it didn't even make sense. When Barba was trying to convince Liv, he effectively said "I'm not saying lie, I'm saying maybe the witness was confused," but what does that have to do with anything? Liv could only testify to what she personally heard. If the witness says, "I told Benson," Liv can't say, "oh, I don't know, maybe she's confused". Liv can only say "yes, she told me," or "no, she didn't tell me." Liv can only tell the truth, and she's certainly not confused, so what was Barba's point?

Also, we're supposed to believe Barba would jeopardize his own career (which is already in the shitter, so maybe I'd buy that, actually), but also Liv's career, and for what? So he wouldn't lose? For justice? If so, why this case, and not last week's case? Why not next week's case? (thank God there's no next week) Why not every case? Is this something he's done before? Is this something he'll do again, if he thinks he can't win? What are his standards for lying? (probably “is it the season finale?” lol) Does he even have any standards? Where's the line? Is Barba okay with perjury now? And from now on? Or was it a one-time thing?

Dodds Thoughts

I wish the writers had chosen Dodds Sr. as the only character to gently goad Liv into lying. That would have been enough. I don't see why Barba had to compromise his own ethics. As a matter of fact, I loved the Dodds Sr./Olivia scene. It's worth noting that Dodds Sr. didn't actually try to sway her directly, not like Barba did. Dodds Sr. just offered her some perspective, and shared his own experiences. I loved that he said he had played it both ways, in the past. That was believable, for a cop in his position. It was subtle, and beautifully played, and well-written.

Bottom line, Dodds Sr. still let Liv make up her own mind. Barba tried to be cute, all "lol she was confused, Liv, can't you say you were confused too? Pretty please?" which kinda rubbed me the wrong way. And Liv clearly felt the same. Compare her reaction to Barba ("are you kidding me, sis?" and then a hilarious rejection) to her reaction to Dodds Sr. (she legitimately asked for his advice, in the end, with that quote about Mike lol whos' mike?, and she genuinely smiled at him).

I don't know. The whole thing reeked of "omg you guys it's the season finale and we need some drama". I'm glad Liv decided not to lie.

But let’s get to Sonny:

Sonny's Temper

Finally, the writers found a way to make Sonny angry in a believable way. In a way that wasn’t out of character. In a way that made sense in context, and didn’t come out of nowhere. Seriously, out of all the instances in which Sonny has lost his temper this season, this is the one and only time I felt for him, and thought he was justified. I mean, was it necessary to have him body slamming people left and right, throughout the episode? No. Was it necessary to have him (and everybody else) yelling in every other scene? No. But was it too much, or too violent? Also no.

This wasn't random anger for no reason, this wasn't just, "OK guys let's all SHOUT all our LINES because it's the season FINALE!!!!" (though that totally happened, too. They even got the usually very whispery Kirk Acevedo to yell, which made me laugh).

Sonny had a real reason to be mad, and that made a difference. Roughing up a perp is one thing, and it still makes me uncomfortable because I'm a SJW oops, sorry, I thought I was an SVU writer for a second, and I started using buzzwords :D

But shoving ICE agents, because they're detaining a key witness, and they're practically sending him to his death? Making Sonny break his promise, in the process? And letting rapists and murderers go free? That’s anger I can get behind.

I also appreciated the way Sonny and Barba argued without either of them losing their temper. They disagreed (and they didn't even really disagree, because Barba was only suggesting to use the threat of deportation as a bluff sort of), but they just expressed their opinions as professionals, and as equals, without any yelling or finger-wagging. And they both (sort of) had a point. That's the type of argument we might have seen in a previous season, and I enjoyed it watching it play out.

Sonny and Empathy

Finally, we got to see Sonny's love for children, shining through. That was always one of Sonny's main characteristics, and we never got to see it this season (aside from Great Expectations, a rare highlight). The way Peter conveyed Sonny's dismay at busting in on a couple of little girls with a gun in his hand? It was only a two-second reaction, but it said it all. Same for the way he tried to be there for Hector's poor daughters, kneeling in front of them at the hospital, trying to keep them away from their rightfully furious mother.

It was also interesting how Sonny was the only character who had strong feelings about threatening a woman using her children as leverage. Amanda and Liv, both mothers, had no such qualms (Rollins threatened multiple people's kids, like five times, and Liv was fine with literally calling ICE). Barba also had no qualms, but then Barba isn't exactly the most emotional person, lol.

I have to say, I didn't enjoy those threats. Every time, I'd side with the mother (even the racist one, who otherwise made me shudder). Leave kids out of this (didn’t Liv and Amanda go through this themselves, in Real Fake News?). And don't use shitty and scary immigration laws to threaten innocent people. It should be said, Soledad's husband was certainly complicit, but Soledad herself was just lying to keep her family together. Yes, murderers would go free as a result, but her motives weren't evil. Did she deserve to be separated from her kids?

And, the real question here, the one Liv and Barba ignored: did Soledad’s kids deserve to be separated from their mother?

That was my main issue (and also the main reason I loved Sonny’s reaction). I did agree with Barba in having little sympathy for Soledad, because ultimately she was lying, but what about her children? Barba had no sympathy for them, either. Sonny did (and Fin and Amanda seemed to agree). Sonny even sweetly said, "it's late, her kids are asleep," which was a wonderful detail. Liv and Barba were like, "Round 'em up! Right now! Traumatize those kids for life! Coercion! Fuck yeah!" but Sonny actually stopped to consider the emotional implications for those kids. That one line, and the way he said it, it moved me. It was perfectly consistent with Sonny's personality. He cares. He sees the big picture, but he also thinks about the little things, and how they affect others. Especially children.

That’s why that was my favorite Sonny moment in the entire finale. It showcased his empathy, and his idealism, and his conviction in his beliefs. Sonny has always been unafraid to speak his mind, even if his superiors disagree.

Speaking of Sonny's superiors, I wonder if this stunt made Sonny respect Liv and Barba a little less. Because that happened to me. And Fin, who totally called Liv out :D

Morality Thoughts

I may joke about it, but I loved how Sonny and Fin clearly didn't approve of that stunt, of threatening a mother of two small children with deportation, and I appreciated the fact they were "allowed" by the writers to express those opinions to Barba and Liv, respectively. I also liked that Liv didn't answer Fin's question. That's the type of "grey area" writing which was sorely missing this season.

This was the rare instance when the audience wasn't expected to think Liv is 100% right, for a change, and the writers even had a beloved character like Fin call her out. They had an idealistic and sincere character like Carisi call out a more pragmatic and underhanded character like Barba. That was actually good writing (what???). Letting the audience draw its own conclusions. I wish the writers hadn't waited until the finale to start doing that.

Stray Thoughts

This season didn’t give us much on the Barisi front (or on any front), but it did give us this:

YOU’RE GONNA DEPORT ME TO CUBA? AND TAKE HIM TO ITALY? :DDD

Peter Gallagher is so handsome. And so talented. He brings so much to all his scenes. How does he do it? And why can't the rest of the SVU cast do it too, lol? No one came close to his nuanced performance, last night (from the regulars, I mean. The guest cast was mostly fantastic). And his lines weren't even that great. Honestly, how does he do it? I love him.

I also love not Eddie Kirk Acevedo. Were they trying him out as a potential new squad member, pairing him up with Sonny, and having him participate in an interrogation with Amanda, or is that wishful thinking? And does it even matter, now that we'll get a new showrunner? I mean, they probably needed guest stars to fill the airtime, because the finale was 2 hours long and the show only has like 3 characters left :D

Fin still has a detective's badge, right? Did I blink and miss him actually making Sergeant? And did I also miss a reference to his twitter-grandson?

Rollins, after shoving and practically headbutting that woman in front of her small son: "Honey it's okay, your mommy's fine! I'm just about to punch her in the face, but it's all good! Go play with your Xbox!"

I liked Yusef's reactions to Sonny's naive remarks about America. "I get it." "No you don't." Damn straight.

Did Sonny kick down that door literally ON that woman's face? The hell? She was standing right behind the door as he kicked it! Sonny, sweetie, you're no Derek Morgan. Leave the door-kicking to the experts.

Barba keeps getting swerved by Liv, lmao.

I won't get into the politics of it all. I don't have the time or the inclination. I'll just say the script was way too heavy-handed. I mean:

random guy, for no reason whatsoever: "What is happening in this country? This is America, right?"

Sonny (and me): "...yeah okay thank you we'll call you if we need anything else bye"

I am GLAD that's over.

#sonny carisi#rafael barba#olivia benson#fin tutuola#svu#law and order svu#episode thoughts#long post#also#amanda rollins'#is amanda an afterthought for the writer lately#or is it me#anyway#season eighteen is DONE#and not a moment too soon#onwards and upwards#phew#ok now i can finish that episode tag#and then#the halloween fic lmao#and THEN THE WEDDING FIC#no promises on when#but it'll happen#i love you all

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ironists of a Vanished Empire

Adam Kirsch June 22, 2017 Issue

Edge of Irony: Modernism in the Shadow of the Habsburg Empire

by Marjorie Perloff University of Chicago Press, 204 pp., $30.00

Marjorie Perloff is one of America’s leading critics of poetry, having spent a long career writing on the work of avant-garde poets from Frank O’Hara to Charles Bernstein. But though she is the author of many books, she wrote in her 2004 memoir, The Vienna Paradox, “when I see [my] name in print…there is always a moment when I wonder who Marjorie Perloff is. It just doesn’t look or sound like me.” That is because, until she became a US citizen at the age of thirteen, she was called not Marjorie but Gabriele—Gabriele Mintz, the name she was born with in Vienna in 1931. Just seven years old when she came to America, Perloff can be counted as perhaps the youngest of the great wave of European Jewish intellectual refugees who immeasurably enriched American culture. On March 13, 1938, the day after Hitler’s armies marched into Austria to annex it to the Reich, the Mintz family boarded a train for Zurich, and kept moving until they had reached the Bronx, where Perloff would spend the rest of her childhood.

The dramatic metamorphosis from Gabriele to Marjorie, from haute-bourgeois Jewish Vienna to middle-class Riverdale, is the subject of Perloff’s excellent memoir. The Austria where she was born was a rump state, carved at the end of World War I from the defeated Austro-Hungarian Empire. But it retained some of the grandeur of the empire’s multinational culture. And none of the empire’s many ethnic groups—Germans, Hungarians, Czechs, Slavs—did more to create that culture, or held it in greater reverence, than its Jews. The emigration of Jews from rural villages in Galicia and other parts of Eastern Europe to the capital in Vienna had created, before World War I, an intelligentsia of amazing accomplishment, including figures like Gustav Mahler and Sigmund Freud.

As Perloff writes, Vienna’s Jews were passionate about German culture even though, or perhaps because, they were for the most part rejected as members of the German nation:

The alternative to…nationality was the Kulturnation of German Enlightenment culture—the liberal cosmopolitan ethos of Bildung [development], which had its roots in the classical Greek notion of paideia. Bildung was more than “civilization,” since…it was conceived as having a distinct spiritual dimension. Thus the cult of Kultur was gradually transformed into a kind of religion.

In her memoir, Perloff is alternately nostalgic for this religion of culture and suspicious of it. Plainly, the Viennese Jews’ enthusiasm for art and intellect did not earn them a secure place in Austrian society. On the contrary, fin-de-siècle Vienna was one of the birthplaces of political anti-Semitism, the place where the young Hitler first expressed his hatred of Jews. For all the accomplishments of the German Jews, Kultur could be seen as a kind of lullaby they sang to themselves as the walls closed in.

For a young girl trying to grow up into an American, Perloff writes, her parents’ inherited snobbery toward all things American, their nostalgia for the Vienna they had left behind, was maddening. “As a teenager, I was always hearing conversations culminating in the phrase, Dass ist doch nur Kitsch! (This is merely kitsch!),” she remembers. When Perloff “expressed my enthusiasm for Carousel,” the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, “my mother and grandmother gave each other a look, as if to say, ‘Poor child, she doesn’t yet understand.’” In a sense, Perloff’s career as a literary critic can be seen as an attempt to bridge these two realms of taste and value, showing that American postmodern writers, though saturated in mass media and popular culture, can be as sophisticated and rewarding as the Old World modernists.

In Edge of Irony: Modernism in the Shadow of the Habsburg Empire, Perloff returns to the world of her birth. She engages in a close reading of six major post-imperial Austrian writers, making the case for the existence of a distinctive and valuable tradition of “Austro-Modernism.” Modernism, in the twenty-first century, is almost as venerable as the Renaissance. When we look for the writers who shaped our world, we are likely to name the titans who lived a hundred years ago—Woolf, Pound, Proust. As these names suggest, however, it is “French and Anglo-American Modernism,” Perloff observes, “that has been the source of our norms and paradigms for the early century.” When it comes to the German-speaking world, too, there is a whole academic industry devoted to the writers, thinkers, and artists who flourished in Weimar Germany—figures like Thomas Mann, Walter Benjamin, Bertolt Brecht, and Kurt Schwitters.

But Perloff believes that this focus on Germany has cast a shadow over the distinctively different work done by twentieth-century German writers who lived in the territories once belonging to the Habsburg Empire. The poet Paul Celan was born in Czernowitz in Romania; the memoirist Elias Canetti was from Rustchuk in Bulgaria; the novelist and journalist Joseph Roth was from Brody, which after 1918 became part of Poland. But all of these places were once part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and Perloff considers them all as belonging to a coherent Austrian tradition. She reads them alongside three other writers closely associated with Vienna: the satirist Karl Kraus, the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, and Robert Musil, the only one of the six who was not Jewish.

It is a disparate group, but Perloff believes they share a certain sensibility, a way of thinking and feeling, that can be traced to their situation as legatees of a vanished empire. Modernism is usually thought of as being radical in all directions; whether they were politically revolutionary or reactionary, modernist thinkers strove for a new beginning in art and culture. “The essential elements of our poetry will be courage, audacity and revolt,” announced F.T. Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto in 1909. For the Austro-Modernists, by contrast, the dominant spirit was irony, as Perloff explains:

Its hallmark [was] a profound skepticism about the power of government—any government or, for that matter, economic system—to reform human life. In Austro-Modernist fiction and poetry, irony—an irony less linked to satire (which posits the possibility for reform) than to a sense of the absurd—is thus the dominant mode. The writer’s situation is perceived not as a mandate for change…but as an urgent opportunity for probing analysis of fundamental desires and principles.

This preference for diagnosis over prescription, for retrospection over renovation, is so far from what we usually think of as modernism that it may not seem to deserve the name. But in her case studies, Perloff argues convincingly that post–World War I Austro-Hungarian literature—a literature named after a country that had ceased to exist—did share fundamental elements with the wider modernist project. The preference for fragments over wholes, the resistance to “closure,” the dissolving power of analysis—these qualities, which we find in Eliot’s “The Waste Land” or Pound’s Cantos, Perloff also locates in works ranging from Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations to Kraus’s epic satirical play The Last Days of Mankind. The difference is that, while Eliot and Pound put their faith in various reactionary doctrines to repair the damage of the twentieth century, the Austro-Modernists remained poised in skepticism. To use a word that Perloff avoids, there is something liberal—in the sense of anti-utopian, anti-ideological—about these writers.

This skepticism about ideology appears to be an echt-Austrian quality, which developed over the course of the long reign of Emperor Franz Josef, from 1848 to 1916. During this period, the rise of nationalism in Eastern Europe and of Prussian military power robbed the Austro-Hungarian Empire of its raison d’être. The empire satisfied neither the militant pan-Germans, who looked to Prussia for leadership, nor the other ethnicities living under Habsburg rule, who yearned for independence. All that was holding the empire together, it came to seem, was the personal authority of Franz Josef, who was revered as the symbol of a continuity everyone knew was on its last legs.

For writers looking back on this long Indian summer of empire, from the vantage point of post-1918 anarchy, it was the very mildness of this ruling principle—its tolerance, even its slovenliness—that inspired nostalgia. This was especially true for Jewish writers who found themselves in successor states where anti-Semitism flourished, and who remembered the monarchy as a bulwark that had once held anti-Jewish hatred at bay.

One of the greatest elegies for the empire came from Robert Musil, who was born in 1880 and raised in Bohemia. In his unfinished novel, The Man Without Qualities, which is set in Vienna in 1913, Musil evoked the atmosphere of resigned mediocrity that sustained the empire he called “Kakania.” The name is a double pun. It evokes the phrase kaiserlich und königlich, “imperial and royal,” which was affixed to the empire’s institutions, since Franz Josef—in a typically Austrian compromise—reigned as both emperor of Austria and king of Hungary. But it also puns on the word “kaka,” which in German as in English is a childish name for excrement.

The eighth chapter of the first book of The Man Without Qualities is Musil’s ode to Vienna’s mixed-up, ridiculous, but curiously resilient regime. Musil writes:

By its constitution it was liberal, but its system of government was clerical. The system of government was clerical, but the general attitude to life was liberal. Before the law all citizens were equal, but not everyone, of course, was a citizen. There was a parliament, which made such vigorous use of its liberty that it was usually kept shut; but there was also an emergency powers act by means of which it was possible to manage without Parliament, and every time when everyone was just beginning to rejoice in absolutism, the Crown decreed that there must now again be a return to parliamentary government.

To Musil, all this confusion left Franz Josef’s subjects “negatively free,” and he concludes that “Kakania was perhaps a home for genius after all; and that, probably, was the ruin of it.” Certainly his own novel is a portrait of genius—in the shape of Ulrich, the titular man without qualities—that can find no expression, no worthy aim, no intellectual or spiritual discipline. What Ulrich finds instead is a job with the Parallel Campaign, an initiative to celebrate the seventieth year of Franz Josef’s reign, in 1918.

Of course the reader knows, as the characters do not, that the emperor will die before that anniversary, and so will the empire. The whole campaign is an exercise in hubris and blindness, accentuated by the fact that no one involved can actually define what they intend to accomplish. All they can do is rhapsodize: “Their goal must stir the heart of the world. It must not be merely practical, it must be sheer poetry…. It must be a mirror for the world to gaze into and blush.”

The Austrian idea is empty, but at least it is not menacing. The same can’t be said of another character, Hans Sepp, whom Perloff sees as a representative of the fascism that would triumph after the war. Sepp, Musil writes, was part of a “Christian-German circle” that opposed “‘the Jewish mind,’ by which they meant capitalism and socialism, science, reason, parental authority and parental arrogance, calculation, psychology, and skepticism.” Musil, writing his novel in the 1920s—the first two parts were published in 1930 and 1933—could already see that this kind of all-too-definite ideology had triumphed over Kakanian “negative freedom.” Musil himself, like the Mintz family, had to flee Austria after the Anschluss—among other things, he was vulnerable because he had a Jewish wife—and he died in penury and obscurity in Switzerland in 1942.

A similarly grim end was in store for Joseph Roth, whose The Radetzky March is the other major novelistic elegy to the vanished empire. This book too, in Perloff’s words, “tracks the dissolution of a particular complex of values—values in many ways absurd and regressive, but benign in comparison to the political climate of post–World War I Europe.” The story concerns three generations of the Trottas, a family elevated to the nobility when the grandfather, an ordinary peasant turned soldier, saves the life of Franz Josef at the Battle of Solferino. The grandson, Carl Joseph von Trotta, is an officer in the imperial army on the eve of World War I, where he too experiences the breakdown of traditional martial and aristocratic values. Perloff emphasizes that this is above all a breakdown of language: “Words—the official words and state dogma—can no longer control actions.”

Language was inevitably a central issue for writers in a polity that was riven along linguistic lines, and it is one of the recurring themes of Edge of Irony. Karl Kraus, the arch-satirist of imperial and post-imperial Vienna, edited a one-man journal, Die Fackel, whose major purpose was to expose and denounce journalistic clichés. Perloff’s chapter on Kraus focuses on The Last Days of Mankind, his immense antiwar drama, which he worked on throughout World War I and completed in 1922.

The work is unperformably long: as Kraus himself wrote, “the performance of this play, which according to terrestrial measurement of time would encompass about ten evenings, is intended for theater on Mars.” Rather than a script, Perloff thinks of it as “hypertextual,” an assemblage of “newspaper dispatches, editorials, public proclamations, minutes of political meetings, or manifestos, letters, picture postcards, and interviews—indeed, whatever constituted the written record of the World War I years.” In this way, Kraus anticipates today’s conceptual poets, such as Kenneth Goldsmith—a writer much admired by Perloff—whose work consists largely of transcriptions. (Goldsmith once led a project called Printing Out the Internet, which attempted to do just that; it’s easy to imagine Kraus admiring this impossible dream.)

Kraus famously referred to Vienna as a “proving ground for the destruction of the world,” and in The Last Days of Mankind he showed that the first stage in this process was the destruction of language. In one scene, Kraus mocks the wartime vogue for banning German words of foreign origin by having a character deliver a speech on behalf of “the provisional Central Commission of the Executive Committee of the League for the General Boycott of Foreign Words”—a speech that, Perloff observes, is “a tissue of foreign phrases,” including the word “boycott” itself.

In another scene, he has two characters discuss the proliferation of wartime rumors, in a dialogue where the word “rumor” appears thirty times, reducing language to nonsense: “The rumor going around in Vienna is that there are rumors going around in Austria,” and so on. Kraus’s emphasis on language might seem excessive until one remembers the euphemisms coined by the Nazis to conceal their crimes—proof that the corruption of language is indeed indispensable to the corruption of human beings.

The issue of language unites post-imperial writers as different as Elias Canetti, known mainly for his study Crowds and Power and his memoirs, and the poet Paul Celan. Perloff observes that, in describing his own childhood, Canetti makes much of the continual changes of language to which he was subject. Born in a Sephardic Jewish community in Bulgaria, he grew up speaking Ladino at home and Bulgarian to his neighbors; meanwhile his parents spoke German to each other, and a move to England brought English into his repertoire as well. Not until he turned eight and the family moved to Vienna did German become his “mother tongue.” But can a mother tongue acquired so late really be called native speech? Perloff argues that Canetti’s own prose “is the language of the always already translated,” as if “he intuitively looked for words and syntactic constructions that would ‘go’ in the other language.” In this sense, cosmopolitanism is a kind of dispossession.

If Perloff finds Canetti’s language insufficiently knotty and idiosyncratic, the same certainly can’t be said for Celan, one of the most difficult poets of the twentieth century. With Celan, she writes, “irony is carried to its logical conclusion, which is to say, a refusal to define, to assert, to take a stand,” even when it comes to matters of simple denotation. Perloff focuses particularly on the love poems Celan wrote to the Austrian poet Ingeborg Bachmann, in which “the scene of encounter tends to be abstract.” “White and Light,” for instance, reads in part: “White,/what moves us./without weight/what we exchange/white and light:/let it drift.” There is eroticism in these lines, a sense of something intimately shared. But there is also a profound sense of disconnection, Perloff observes: “The love proffered here is intense but hardly a source of joy,” partly because the world of the poem is abstract and underpopulated, a place where “no one else exists but the lovers.” Language, in Celan’s verse, often seems to have broken away from the world altogether, becoming almost a self-referential medium.

This pessimism about the power of language to communicate and refer may be the most important marker of Austro-Modernism. Kraus’s aggressive burlesque of journalism and slang, Roth’s melancholic mockery of the codes of chivalry and military honor, Canetti’s sense of being permanently lost in translation—in various ways, all of Perloff’s subjects seem to be in mourning not just for an empire and a way of life, but for the transparency and meaningfulness of language itself. As Austrians and, in many cases, as Jews, these writers had a unique vantage point on the crisis of language that was to become so central to modernism in all its guises. The edge of irony, Perloff shows, was an uncomfortable place to live, but a fruitful place to write from.

http://www.nybooks.com/articles/2017/06/22/marjorie-perloff-ironists-vanished-empire/

@catcomaprada as if you do not have enough to read lol

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

“then you tell me why.”

@quaesanat !

❝ y - you can’t heal me b - because ❞ because if i go up to the surface , then you will know i am human . how many times have melody watched her own tail sheds into two human legs ? mother used to say that it’s painful ; the growing nerves and receptors of a human feeling like thorns and knives against the muscles that would form in replacement of the fin and scales a merperson may reject . but melody does not feel pain . once she is human , her legs loses all of its function , and it’s it’s horrendous .

mother says too : once you are human , you cannot flimsily return to being a mermaid as you wish . the process itself feels like you’re blinded by rays of sun that will burn you ; you are only one species at a time . and thus , in the disguise of a curse , melody’s condition were also considered an awkward blessing , for she may turn and re - turn herself human and mermaid , but not an ounce of pain will follow . in return , however , her human life will be compromised of half - blind vision and paralysed legs . mother informs , do never tell this to anybody . for they will bind you and experiment ; their curiosities running deeper than their empathy to care and protect .

they would ask : why were you given the choice of being two species at a time ? while they cut you open and seek answers in your blood .

——— do not let them get to you , melody .

but she’s hurt , she wishes she could say . her tail is spreading blood all over the clean water and there’s this girl , offering to heal ... why wouldn’t she take them ? she wants so bad to just take it to relieve of the pain ( she hasn’t felt that in so long ! ) but what would happen if she do ? melody swims a bit further to avoid the other’s steadying gaze , almost stumbling back , despite her tail requesting otherwise — and winces . she needs to give an answer . clearly the other is seeking for one . ❝ — because i don’t tr - trust ... i don’t trust you . ❞ i’m not supposed to .

five word prompt » accepting !

#quaesanat#me: ok u're probs gonna answer this in 1 para the most#me actually writing: Betrayed and Hurt#idek what im doing bruh dont look at me

1 note

·

View note

Link

Image caption The BBC understands the talks ended at about 19:30 BST on Friday, breaking up fairly abruptly

The absence of devolved government in Northern Ireland “cannot continue for much longer,” Secretary of State James Brokenshire has said.

He spoke after another day of talks between the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and Sinn Fin ended with no deal.

Theresa May phoned DUP leader Arlene Foster and Sinn Fin’s northern leader, Michelle O’Neill on Friday evening.

The PM told them her government was committed to doing all it could to help parties reach a successful conclusion.

‘Running the show’

A No 10 spokesperson said Mrs Foster and Mrs O’Neill “both agreed on the need for the executive to be restored for the benefit of everyone in Northern Ireland”.

“The Prime Minister recognised that constructive discussions had taken place between the parties and urged them both to come together reach a collective agreement so that devolved government could be restored in Northern Ireland.”

The BBC understands the latest round of Stormont talks ended at about 19:30 BST on Friday, breaking up fairly abruptly and not in a positive mood.

Sinn Fin said no progress was made but added talks will resume on Saturday.

Speaking on the BBC’s Any Questions programme, Mr Brokenshire said: “We’ve obviously had an extended period where Northern Ireland has not had politicians making decisions.

“The Northern Ireland Civil Service has effectively been running the show here. That cannot continue for an extended period, for much longer.

“I’ve already had to make certain statements over the budget to ensure that civil servants are able to do their job, so yes, it is about that focus on what now needs to happen.”

Image caption Mr Brokenshire (right) took part in a recording of the BBC’s Any Questions programme in Ballymena

When the parties missed a government deadline on Thursday, the secretary of state extended the talks over the weekend, in the hope that a deal will be struck by Monday, when he is due to make a statement on Stormont’s future.

Earlier, Sinn Fin called for the British and Irish prime ministers to become directly involved in the talks process.

The party said the DUP had not moved on a number of issues, including an Irish language act, same-sex marriage, a Bill of Rights and measures to deal with the legacy of the Troubles.

Sinn Fin’s Conor Murphy said it was a “source of frustration” there had been no closing of the gap between the parties throughout the day.

He claimed that the DUP “haven’t yet accepted what brought down the institutions in the first place”.

But the DUP’s Christopher Stalford said Sinn Fin had presented a “shopping list” of demands and was refusing to go back into government until they had received every item on their list.

‘5% budget cut’

His party colleague, Edwin Poots, rejected a call for the prime ministers to get involved and said Sinn Fin knows what is required and “don’t need anyone to hold their hands”.

Mr Poots said Thursday’s missed deadline meant Stormont was now “operating on a 95% budget, which is essentially a 5% cut across all of the departments”.

The DUP MLA described this as “far greater austerity than any Conservative ever imposed upon the Northern Ireland public”.

Image caption Edwin Poots of the DUP said Sinn Fin “don’t need anyone to hold their hands”

“Whilst we understand that Irish language is hugely important to Sinn Fin – health, education, jobs, the economy, infrastructure, environment, agriculture – all of these issues are hugely important to us, hugely important to the public,” Mr Poots said.

Responding to his remarks, Mr Murphy said: “The DUP are in absolutely no position to lecture anyone in relation to the provision of public services.”

The Sinn Fin MLA accused DUP MPs of voting for a measure in the Queen’s Speech “which will effectively remove and reduce public sector wages”.

Earlier, his Sinn Fin colleague John O’Dowd said there must be a “step change” for talks to succeed.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

Media captionSinn Fin’s John O’Dowd calls on PMs to join Stormont talks

“As co-guarantor of the agreements, it is time for the British Prime Minister Theresa May and the Taoiseach (Irish Prime Minister) Leo Varadkar to take direct responsibility.”

Mr O’Dowd also said the DUP’s “confidence and supply” deal with the Conservatives had “emboldened and entrenched” their views, making the prospect of a deal less likely.

Tory-DUP deal: What you need to know

Ulster-Scots ‘forgotten’

Why Irish language is so divisive

A Downing Street spokesperson said that the secretary of state was on the ground in Belfast and would continue to engage intensively with the parties on Friday and over the weekend.

“The prime minister has met with all five parties and will continue to have close engagement with the Northern Ireland secretary and the taoiseach, who she spoke with earlier this weekend,” they added.

‘Crisis to crisis’

The secretary of state has the option of giving the parties more time to negotiate, calling another assembly election or reintroducing direct rule from Westminster.

The independent chair of the talks process, Sir Malcolm McKibbin, formally retired on Friday as head of the Northern Ireland Civil Service.

However, parties asked him to stay on as chair to steer the negotiations.

Analysis: Mark Devenport, BBC News NI political editor

While we’ve bust through another deadline, it’s a deadline that theoretically still exists.

So, Secretary of State James Brokenshire is under responsibility to set a date for a fresh assembly election.

However, everybody is expecting he will consider his options and come through with an emergency law to either allow for yet another deadline or move towards to some form of direct rule.

The mood music around Stormont hasn’t been particularly favourable.

I don’t get any kind of immediate sense that the parties are going to come up with an ingenious compromise.

Under the deal signed in Downing Street on Monday, the minority Conservative government can rely on the support of the DUP’s 10 MPs to get legislation through the House of Commons.

Critics of the deal have questioned whether the Westminster government can act with impartiality between unionists and Irish nationalists when it is dependent on the support of the DUP.

Conservative MP Laurence Robertson told the BBC’s The View programme that Mr Brokenshire would “weigh it up over the weekend” but added he did not believe there was any appetite for another snap assembly election.

Mr Robertson chaired Westminster’s Northern Ireland Affairs Committee for two terms from 2010 until the Dissolution of Parliament in May this year.

Image caption Conservative MP Laurence Robertson blamed Sinn Fin for the Stormont standoff

He told the programme that Stormont could not “keep stumbling from crisis to crisis” but added he hoped Northern Ireland was not heading for a prolonged period of direct rule.

“I sincerely hope not, I was a shadow minister when we had the last period of direct rule and very important issues are decided upstairs in the House of Commons, in a committee of 20 MPs.

“That’s no way to run Northern Ireland so I sincerely hope not.

“But, somebody has to run the province, so if that’s what Sinn Fin are forcing, well, that might be the only option.”

‘Dangerous game’

However, Mr Robertson said he did not think his party’s agreement with the DUP was causing the problem, because Stormont’s latest crisis had happened “long before” the deal.

“I think it’s a problem within Sinn Fin,” the Tory MP said.

“I don’t know what game they are playing, but I do know it’s a dangerous one.”

Northern Ireland has effectively been without a devolved government for almost six months.

Its institutions collapsed amid a bitter row between the DUP and Sinn Fin about a botched green energy scheme.

The late deputy first minister, Martin McGuinness, stood down in protest over the DUP’s handling of an investigation into the scandal, in a move that triggered a snap election in March.

View comments

Related Topics

Sinn Fin

DUP (Democratic Unionist Party)

Read more: http://ift.tt/2somaDa

The post NI talks standoff cannot go on much longer, says James Brokenshire – BBC News appeared first on MavWrek Marketing by Jason

http://ift.tt/2srFwHx

0 notes

Text

Turning Homes for Quick Realty Revenue

youtube

One of the increasing stars when it comes to real estate investment is called 'flipping' homes. This functions by buying residential or commercial properties that are in need of either small cosmetic fixings or seeking severe renovations, doing the work, as well as selling the house for a much higher price. Theoretically this generates a substantial amount of revenue in a rather percentage of time. This holds true for lots of that attempt to turn residential or commercial properties yet it takes a little greater than the concept in order to make the process work. Consequently, there are many that wind up compromising earnings or losing loan while doing so when strategies aren't well conceived.If you are considering a future in realty investing, this is just one of the quickest methods which capitalists can make a profit. It is likewise an approach for bringing in high revenue in a brief quantity of time. Sadly, this when closely secured key has obtained some level of infamy as well as there is intense competitors for the underestimated residential or commercial properties on the marketplace as more and more would certainly be capitalists make a decision to throw their hats right into the collective ring.If you are taking into consideration real estate financial investments generally and also house flipping in particular there are some points you ought to remember. new rochelle home values 1) Treat this as an organisation instead of a leisure activity. Far too many financiers do not take their investments seriously. This is an error due to the fact that in this business time is cash and on a monthly basis that your home isn't marketed is a month that the house is costing you money. Develop a plan, make a schedule, and also stick to them both.2) Bear in mind that this is a service. You are not purchasing residential properties making friends or seem wonderful. You remain in this company to make a profit. You can not be shy about making low offers. The ability to buy reduced as well as sell high is the lifeblood of this specific organisation. This implies that you are fairly most likely mosting likely to injure feelings and make individuals mad (since they frequently position emotional costs to their houses that are just not financially feasible). If you can not take care of this reality after that you are mosting likely to have some degree of trouble acquiring the high earnings you are looking for. Good guys end up last and also you can not truly pay for to do that in this job.3) Pay attention to the marketplace. This is essential. Many 'fins' shed their t shirts in the recent near collapse of the housing market around the U. S. The what's what is that the indications have been constructing for years. In cities where there was as soon as a scarcity of sensible real estate options there are presently surpluses. This does not own the worth of homes down so much as it brings them back to their appropriate values. Investors that were counting on a capacity to sell above the actual worth of the residential or commercial property were left holding the bag (or rather notes) on these homes for quite time until they can be offered. Some never handled to market these homes as well as were left taking care of the expense along with the costs of the upgrades. Do not buy in a filled with air market if it could be stayed clear of unless it is throughout the very beginning of the inflation (prior to home programmers have the possibility to produce a surplus).4) Do not enable it to come to be individual. Far way too many very first time house fins decide to produce a work of art rather than a business investment. It is alluring when making cosmetic and structural repairs to go on and also create a dream house. The issue with this is that depending upon the particular market you are not likely to recover the costs involved in doing so. The objective is to spend little and revenue huge. Granite countertops are lovely but never required in an area filled with those of simple methods. Accommodate the tastes and budget plans of your target market instead of your personal tastes.Regardless of the threats associated with flipping houses as a realty financial investment there is no rejecting that fortunes have been made doing just that. Also in the current real estate market there is a great deal of guarantee offered to those that can do the job quickly and also inexpensively. People still want to acquire these charming houses rather than buying a house that should be transformed after the rate of purchasing.

0 notes

Text

Ironists of a Vanished Empire

Adam Kirsch

June 22, 2017 Issue

Edge of Irony: Modernism in the Shadow of the Habsburg Empire

by Marjorie Perloff University of Chicago Press, 204 pp., $30.00

Marjorie Perloff is one of America’s leading critics of poetry, having spent a long career writing on the work of avant-garde poets from Frank O’Hara to Charles Bernstein. But though she is the author of many books, she wrote in her 2004 memoir, The Vienna Paradox, “when I see [my] name in print…there is always a moment when I wonder who Marjorie Perloff is. It just doesn’t look or sound like me.” That is because, until she became a US citizen at the age of thirteen, she was called not Marjorie but Gabriele—Gabriele Mintz, the name she was born with in Vienna in 1931. Just seven years old when she came to America, Perloff can be counted as perhaps the youngest of the great wave of European Jewish intellectual refugees who immeasurably enriched American culture. On March 13, 1938, the day after Hitler’s armies marched into Austria to annex it to the Reich, the Mintz family boarded a train for Zurich, and kept moving until they had reached the Bronx, where Perloff would spend the rest of her childhood.

The dramatic metamorphosis from Gabriele to Marjorie, from haute-bourgeois Jewish Vienna to middle-class Riverdale, is the subject of Perloff’s excellent memoir. The Austria where she was born was a rump state, carved at the end of World War I from the defeated Austro-Hungarian Empire. But it retained some of the grandeur of the empire’s multinational culture. And none of the empire’s many ethnic groups—Germans, Hungarians, Czechs, Slavs—did more to create that culture, or held it in greater reverence, than its Jews. The emigration of Jews from rural villages in Galicia and other parts of Eastern Europe to the capital in Vienna had created, before World War I, an intelligentsia of amazing accomplishment, including figures like Gustav Mahler and Sigmund Freud.

As Perloff writes, Vienna’s Jews were passionate about German culture even though, or perhaps because, they were for the most part rejected as members of the German nation:

The alternative to…nationality was the Kulturnation of German Enlightenment culture—the liberal cosmopolitan ethos of Bildung [development], which had its roots in the classical Greek notion of paideia. Bildung was more than “civilization,” since…it was conceived as having a distinct spiritual dimension. Thus the cult of Kultur was gradually transformed into a kind of religion.

In her memoir, Perloff is alternately nostalgic for this religion of culture and suspicious of it. Plainly, the Viennese Jews’ enthusiasm for art and intellect did not earn them a secure place in Austrian society. On the contrary, fin-de-siècle Vienna was one of the birthplaces of political anti-Semitism, the place where the young Hitler first expressed his hatred of Jews. For all the accomplishments of the German Jews, Kultur could be seen as a kind of lullaby they sang to themselves as the walls closed in.

For a young girl trying to grow up into an American, Perloff writes, her parents’ inherited snobbery toward all things American, their nostalgia for the Vienna they had left behind, was maddening. “As a teenager, I was always hearing conversations culminating in the phrase, Dass ist doch nur Kitsch! (This is merely kitsch!),” she remembers. When Perloff “expressed my enthusiasm for Carousel,” the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, “my mother and grandmother gave each other a look, as if to say, ‘Poor child, she doesn’t yet understand.’” In a sense, Perloff’s career as a literary critic can be seen as an attempt to bridge these two realms of taste and value, showing that American postmodern writers, though saturated in mass media and popular culture, can be as sophisticated and rewarding as the Old World modernists.

In Edge of Irony: Modernism in the Shadow of the Habsburg Empire, Perloff returns to the world of her birth. She engages in a close reading of six major post-imperial Austrian writers, making the case for the existence of a distinctive and valuable tradition of “Austro-Modernism.” Modernism, in the twenty-first century, is almost as venerable as the Renaissance. When we look for the writers who shaped our world, we are likely to name the titans who lived a hundred years ago—Woolf, Pound, Proust. As these names suggest, however, it is “French and Anglo-American Modernism,” Perloff observes, “that has been the source of our norms and paradigms for the early century.” When it comes to the German-speaking world, too, there is a whole academic industry devoted to the writers, thinkers, and artists who flourished in Weimar Germany—figures like Thomas Mann, Walter Benjamin, Bertolt Brecht, and Kurt Schwitters.

But Perloff believes that this focus on Germany has cast a shadow over the distinctively different work done by twentieth-century German writers who lived in the territories once belonging to the Habsburg Empire. The poet Paul Celan was born in Czernowitz in Romania; the memoirist Elias Canetti was from Rustchuk in Bulgaria; the novelist and journalist Joseph Roth was from Brody, which after 1918 became part of Poland. But all of these places were once part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and Perloff considers them all as belonging to a coherent Austrian tradition. She reads them alongside three other writers closely associated with Vienna: the satirist Karl Kraus, the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, and Robert Musil, the only one of the six who was not Jewish.

It is a disparate group, but Perloff believes they share a certain sensibility, a way of thinking and feeling, that can be traced to their situation as legatees of a vanished empire. Modernism is usually thought of as being radical in all directions; whether they were politically revolutionary or reactionary, modernist thinkers strove for a new beginning in art and culture. “The essential elements of our poetry will be courage, audacity and revolt,” announced F.T. Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto in 1909. For the Austro-Modernists, by contrast, the dominant spirit was irony, as Perloff explains:

Its hallmark [was] a profound skepticism about the power of government—any government or, for that matter, economic system—to reform human life. In Austro-Modernist fiction and poetry, irony—an irony less linked to satire (which posits the possibility for reform) than to a sense of the absurd—is thus the dominant mode. The writer’s situation is perceived not as a mandate for change…but as an urgent opportunity for probing analysis of fundamental desires and principles.

This preference for diagnosis over prescription, for retrospection over renovation, is so far from what we usually think of as modernism that it may not seem to deserve the name. But in her case studies, Perloff argues convincingly that post–World War I Austro-Hungarian literature—a literature named after a country that had ceased to exist—did share fundamental elements with the wider modernist project. The preference for fragments over wholes, the resistance to “closure,” the dissolving power of analysis—these qualities, which we find in Eliot’s “The Waste Land” or Pound’s Cantos, Perloff also locates in works ranging from Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations to Kraus’s epic satirical play The Last Days of Mankind. The difference is that, while Eliot and Pound put their faith in various reactionary doctrines to repair the damage of the twentieth century, the Austro-Modernists remained poised in skepticism. To use a word that Perloff avoids, there is something liberal—in the sense of anti-utopian, anti-ideological—about these writers.

This skepticism about ideology appears to be an echt-Austrian quality, which developed over the course of the long reign of Emperor Franz Josef, from 1848 to 1916. During this period, the rise of nationalism in Eastern Europe and of Prussian military power robbed the Austro-Hungarian Empire of its raison d’être. The empire satisfied neither the militant pan-Germans, who looked to Prussia for leadership, nor the other ethnicities living under Habsburg rule, who yearned for independence. All that was holding the empire together, it came to seem, was the personal authority of Franz Josef, who was revered as the symbol of a continuity everyone knew was on its last legs.

For writers looking back on this long Indian summer of empire, from the vantage point of post-1918 anarchy, it was the very mildness of this ruling principle—its tolerance, even its slovenliness—that inspired nostalgia. This was especially true for Jewish writers who found themselves in successor states where anti-Semitism flourished, and who remembered the monarchy as a bulwark that had once held anti-Jewish hatred at bay.