#The youth are forced by law to sit in a steel chair in school for the entirety of their formative years and yet shit like this happens

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

Videos Show Teen Accused of Trashing Baby Rushing to Bathroom, Staff Detailing Gruesome Crime Scene

youtube

Bodycam: Teen Accused of Dumping Dead Baby in Trash Arrested for Murder in Front of Hysterical Mom

Law&Crime Network

#Youtube#This kind of shit enrages me. This girl was 19 years old and obviously not educated properly. There is no condoning what she did#But this is an example of the system failing the people.#The youth are forced by law to sit in a steel chair in school for the entirety of their formative years and yet shit like this happens#If the system was so concerned about babies being left in dumpsters#Then maybe you should actually start teaching children the importance of real life instead of fucking algebra#This young woman is clearly uneducated and this should be the fault of the adults not knowing how to raise and protect a child#My favourite part is in the second video just after the 5min mark#This fucking cop makes a remark about how they could arrest the mother for “obstruction” when she was only protecting her daughter#Disgusting and a perfect example of these fucking cops playing shit by their books and not having an ounce of humanity#Charging this 19 yo with murder. Fucking MURDER#This wouldn't happen to me because my children would know better.#Parents should remember this and the importance of educating their child properly rather than just expecting the system to do it#Because this is the system at work...

0 notes

Text

Nansook Hong – In the Shadow of the Moons book, part 5

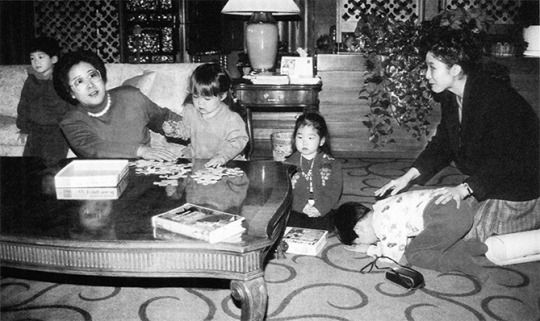

In the family room at East Garden, I instruct my son Shin Gil how to bow before his grandmother, Hak Ja Han Moon. She is surrounded by grandchildren.

In The Shadow Of The Moons: My Life In The Reverend Sun Myung Moon’s Family by Nansook Hong 1998

Chapter 8

page 154

I had just taken my last spring final exam at New York University when Hyo Jin called from Korea in May 1986. He had been in Seoul for weeks. He missed me and the baby, he said. We should come as soon as possible.

It was my first year in college. The Moons had been willing to send me on the theory that my academic success would reflect well on them one day. I had been up late every night for days, studying for finals and writing term papers. I wanted to do well, not only to justify the expense of my education to the Reverend and Mrs. Moon but to feel pride in my freshman accomplishments.

The classroom was the one place in my universe over which I felt complete mastery. I knew how to learn, how to study, how to take tests. I did not know how to think critically, but I rarely had to in order to earn good grades. The memorization skills I had learned as a child in Korea were serving me well in American higher education as well.

New York University had not been my first college choice. I wanted to attend Barnard College, the women’s undergraduate division of Columbia University. I knew it was one of the prestigious Seven Sisters schools and I felt reassured that my classmates would be females. I was married and a mother but still as awkward as an adolescent girl around young men.

Barnard would not have me. I had foolishly applied as an early-decision candidate, a realistic option for only the very best students. My grades were good but my essays showed the lack of self-reflection that characterized my life at that time. I was determined after that initial rejection to do so well at N.Y.U. that Barnard would reconsider and accept me as a transfer student one day.

I was also in my first trimester of a new pregnancy when Hyo Jin summoned me to Seoul, and the prospect of the long flight with a toddler could not have been less appealing. I was worried, too, about the chance of miscarriage after my last, failed pregnancy. But it was so rare for Hyo Jin even to call me when he was away, let alone to request my company, that I eagerly interpreted this as a hopeful sign for our marriage.

The flight was every bit as grueling as I had feared. My daughter was too excited to sleep. She shook me every time I closed my eyes. I kept myself awake with optimistic thoughts of how God must have used this time to soften Hyo Jin’s heart.

I was disabused of that fantasy as soon as my daughter and I arrived at the Moon household in Seoul. Hyo Jin had begged us to come and now he wanted nothing to do with us. I had become accustomed over the years to Hyo Jin’s need to control me, but I was alarmed by his almost paranoid monitoring of my every movement while we were in Korea. When I told him I would like to look up some of my old friends from the Little Angels school, for example, he barked that I would do no such thing. “You have no friends,” he told me. “I am your perfect friend. You do not need anyone else.”

He would become enraged if he returned home and found that I had taken my daughter to visit my parents. It was my duty to be waiting when he came home. He made me so nervous that whenever I went to visit my mother, I called the Moon household each and every hour to see if he was looking for me.

The elder Moons had returned to New York from one of their frequent trips to Korea soon after I arrived in Seoul, but many of the older Moon children were in Korea. In Jin was among them. She had always been very close to Hyo Jin and had not cared for me from the moment we first met. She summoned me to her room a few days after my arrival in Korea. It was clear she was furious at me — for what, I did not know. We had only exchanged polite greetings in the hall.

I sat on the floor, appropriately humble before a True Child. “My brother is working so hard and what are you doing? Nothing!” she shouted. “You are lazy and spoiled. According to Korean tradition, you should be mopping the kitchen floor and washing the dishes. You rank in the lowest position in this family and you should be clear about that.”

I was taken aback, but I knew In Jin did not expect me to answer. To have done so would have been impertinent. What was the point of telling her that Hyo Jin would not permit me to accompany him to church events? What would I gain by contradicting her? I let her fury wash over me. How often had I found myself in this position, on my knees being browbeaten by one of the Moons? It was difficult enough to hear the lies that they heaped upon me, but my powerlessness to respond reduced me to the status of a small child. Did In Jin really think that I preferred to live the life her brother forced on me? Did she think I would not enjoy seeing other people? Was she blind to how Hyo Jin spent his free time in Seoul?

The bar scene was even worse in Seoul than it was in New York. In Korea there was always someone willing to give Hyo Jin money, always some old friend to join him in one or another of his many vices. My mother had asked my uncle Soon Yoo to keep an eye on him. My uncle was a smooth talker, a trumpet player who knew the nightclubs even better than Hyo Jin did. My mom had a soft spot for him because he was the little brother who had brought her shoes to her when my grandmother locked her in her room to prevent her from marrying my father. However, it was unclear who was watching whom when my husband and my uncle were together. After a drinking session, the two of them often visited a Seoul steam bath, where, I later learned, Hyo Jin had found a lover among the towel girls.

One night when Hyo Jin returned home from the bars, I was kneeling beside our bed in prayer, as I did every evening. I heard him come into the room, but I thought I should complete my prayer before greeting him. That was a mistake. His palm slammed into the side of my head. Because of my pregnancy, my balance was off. He knocked me over. “How dare you not rise to greet your husband,” he said, his slurred words evidence that he was very drunk. “I was only trying to finish my prayer,” I said in a foolhardy attempt to explain myself. Hyo Jin let loose with a string of complaints about me and my parents: I was an ugly, fat, and stupid girl; my parents were arrogant and disloyal to Father; they were an evil influence on me. When he went into the bathroom, I saw my opportunity and ran to another room. He was only a few steps behind me.

He began banging loudly on the door. I was terrified and worried his screaming would awaken our child. I huddled on the bed while her madman father tried to batter down the door, which I was grateful had a solid brass lock. After several minutes he left and I fell asleep. I woke the next morning to the sound of his cursing in the hall. This time he was wielding his guitar as a sledgehammer, but the heavy wooden door would not yield. When he left, I ran to another room.

No sooner had I slipped into a room down the hall than I saw him on the balcony outside. He smashed his guitar through the window, raining shards of glass down onto the chair where I had just been sitting. I ran down the staircase, the sound of his angry cursing in my ears. I took refuge in the rooms of a church leader who lived downstairs. Hyo Jin kept shouting for me to show myself. I was scared, but I wasn’t stupid. I knew he would beat me senseless if I came out. I stayed hidden for hours while he recruited others in the household to search for me. When he finally gave up and went out to the bars, I called my father in hysterical tears. He immediately sent a car for my daughter and me.

It was the first time in my marriage that I was afraid for my life. Until then the abuse I had suffered had been more psychological than physical. I had spent years steeling myself against his cruelty and threats. I was “ugly” and “fat” and “stupid.” Without him I was a “nobody” and a “nothing.” I thought I was “so smart,” but he was the son of the Messiah. I could be “replaced.” I had trained myself not to react to his verbal abuse. At some level, I knew he was being defensive. Hyo Jin resented the education I was earning while he squandered his youth on booze and drugs and prostitutes. I knew not to fight back when he attacked me. To do so would only have invited more of the same. I worried for Shin June and the baby I carried, growing up in an atmosphere of such hatred and vitriol. For my children, I kept silent and tried not to offend him. It was like walking on eggshells; anything I said might set him off.

In many ways, Hyo Jin’s abusive behavior was a natural response to the environment of coercion and control in the Moon household and the Unification Church. I, too, suffered under the restrictions the Moons imposed. The expectation that I would be available at a moment’s notice to wait on Mrs. Moon meant I could have no substantive life outside the compound in Irvington. I was a phantom presence on campus when I attended New York University and, later, Barnard College.

Sun Myung Moon sent his children and sons and daughters-in-law to college to earn degrees that would bring greater public glory to him, not a broader personal experience to us. I made no friends for fear such contact would invite questions about my life or require further time away from the compound. Mrs. Moon already considered my studies a usurpation of time that rightfully should have been at her disposal.

I came and went from N.Y.U. with other Blessed Children. I interrupted my education to accommodate my pregnancies so often that I exhausted the number of leaves of absence each N.Y.U. student is allowed. In 1988, having earned high grades at N.Y.U., I transferred to Barnard. A security guard from East Garden would drive me to and from classes. Not even the professor who served as my adviser knew who I really was.

Much later, when I became pregnant with Shin Ok, my fourth child, I applied for a leave of absence from Barnard as well. My adviser, an older female professor, was very solicitous when I told her that I was pregnant. “Are you sure this is what you want?” she asked gingerly. “Oh, it’s O.K. I’m married!” I laughed. What I didn’t tell her was that Shin Ok would be my fourth child. I wasn’t sure Barnard had ever seen a coed quite like me.

The books I read and the lectures I heard exposed me to wider views of the world, but for me it was all an intellectual exercise. In the stacks of Wollman Library at Barnard and of Butler Library at Columbia, I gained information, not insight. I had been trained all my life never to question, not to doubt. No college course on the history of religion, no lecture on the roots of messianic movements, could have shaken my faith in Sun Myung Moon or the Unification Church.

The practical effect of blind faith is isolation. I was surrounded by people who believed as I did. Everything in my life — from my duty to prostrate myself before Mother and Father in greeting each morning to my duty to accept the divinity of my transparently flawed husband — reinforced that isolation. If I was angry or sad or upset, there was no one with whom I could share those feelings. The Moons did not care; my parents were a world away; and the staff of East Garden and ordinary church members barely spoke to me because of my elevated position as a member of the True Family.

I was alone. If not for prayer, I would have lost my mind. God became the friend and confidante I did not have on earth. He listened to my heartache. He heard my pain. He gave me strength to face my future with the monster I had married.

Hyo Jin’s rage in Seoul frightened my parents. They knew I lived a difficult life in East Garden, but this was the first time they had seen my suffering up close. When I had arrived at their home with Shin June, I was still shaking and tearful. We knew Hyo Jin would come to get me, and my parents were powerless to defy the son of the Messiah. I was so scared he would beat me for running away. My father drove me to a hospital in Seoul, where doctors admitted me after we explained what had happened. Hyo Jin called my parents’ home looking for me and demanded that I return. My father told him the doctors insisted I needed to stay in the hospital for the sake of the baby I was carrying.

It was not long before Hyo Jin appeared at my bedside. His message was clear: I could not hide out forever. I could not keep his daughter from him for long. I would have to come back eventually. He did not apologize or even acknowledge why I had fled the Moon household in terror. He wanted only to let me know that sooner or later I would have to return and face him.

I stayed in Seoul with my parents and my daughter for two months. Hyo Jin returned to East Garden. He explained my absence to his parents as an act of willfulness on my part. I was stubborn and defiant. He had had to hit me, he told them, because I had talked back to him. In their view, such physical punishment of a wife was justifiable. I remember one sermon at a 5:00 a.m. family Pledge Service when Father said wives should be struck now and then to keep them humble. “You wives who have been slapped or hit by your husband, raise your hands,” he once instructed at a Sunday sermon at Belvedere. “Sometimes you may be struck because of your lips. The body’s first criminal is the lips — those two thin lips!”

Unificationism teaches that wives are subservient to their husbands, just as children are subservient to their parents. They must obey. “If you beat your children from your temper, it is a sin,” the Reverend Moon has said. “But if they do not obey you, you can bring them by force. It will be good for them, after all. If they do not obey you, you can even strike them.” Just as Sun Myung Moon smacked his children when they defied him, the son of the Messiah felt free to beat his wife when she failed to accord him the respect to which he felt entitled.

A letter soon arrived for me at my parents’ home from Mrs. Moon. She wrote to tell me that I must come back. It was wrong for me to be at my parents’ house. I was not their child; I was Hyo Jin’s wife. She was angry at my mother and father for sheltering me, anger that hardened against them when her own daughter Je Jin and my brother Jin sent their children to stay with my parents in Korea to shield them from the influence of the Moons. Je Jin and Jin were already having doubts about her parents and the church.161

My parents and I both knew my time with them was no more than a temporary respite. I had to go back. It was my mission. It was my fate. It is easy for those outside the Unification Church to wonder how a mother and father could have sent their daughter back to an abusive husband and uncaring in-laws, but my parents and I believed we were fulfilling God’s plan. It was not for us to alter that course. Even to consider leaving Hyo Jin Moon meant rejecting my life, my church, my God. For my parents, it meant questioning every decision of their entire adult lives.

Beyond my religious compulsion to return, there was my fear. A woman does not have to be trapped in a cult to feel powerless before the man who beats her. What battered woman has not heard a well-meaning friend or relative ask: “Why don’t you leave?” It sounds so simple, but how simple is it for a mother of young children without resources who takes seriously her husband’s threats to kill her? Women beaten by their partners are at their greatest risk of being murdered when they flee. Crime statistics confirm that reality but women know it instinctively. Even if I did not have the pressure of my faith forcing me back to East Garden, I had the pressure of my fear.

Leaving my parents’ home that September was awkward and painful for all of us. I did not want to go. They did not want to let me. But none of us could see beyond the power of Sun Myung Moon and his church. There were tearful farewells with my mother and my siblings. My father could not even meet my gaze. I knew that his distress was as great as my own.

Hyo Jin did not come to meet Shin June and me at the airport. When we saw him at Cottage House, it was as though nothing had happened between us. At East Garden, Mrs. Moon summoned me to her room. She welcomed me home and assured me that Hyo Jin had promised there would be no repetition of the incident in Seoul that had kept me away so long. She spoke in euphemisms about his violence and his substance abuse, reminding me that it was my duty to work as God’s instrument to change her son. That was why I had been chosen. On the one hand, all my experience told me that her son was a pathological liar. On the other, I still believed in my divine mission, that God would bring about genuine change in him eventually if only I worked and prayed hard enough. I wanted to believe Mother’s reassurances as much as every battered woman wants to believe her husband’s promises to change.

Mrs. Moon was less indirect about her anger at my parents. It had been wrong of them to keep me in Seoul. She questioned their loyalty to Father. True Parents had been hearing reports from Korea about the Hongs that displeased them. I had only a vague idea of what Mrs. Moon was talking about. For some time my mother had been hinting that all was not well between them and the Reverend and Mrs. Moon. During recent visits of True Mother and True Father to Korea, the Reverend Moon had singled out my father for public criticism. He accused my father of packing 11 Hwa with Hong relatives to the detriment of the company. He accused my father of taking credit for the success of Il Hwa when the success belonged to Sun Myung Moon.

My mother told me these things, but without alarm. Father was known for his perverse inclination to dress down those who actually pleased him. Only in the Unification Church could it be considered a compliment to be criticized in public. I would learn later, though, that the Reverend Moon had begun to take sadistic pleasure in humiliating my father in front of others. At the opening of a bottling plant whose design, financing, and construction my father had supervised, the Reverend Moon scoffed at him as an ineffectual executive who could be fired at the Messiah’s whim. At his breakfast table in Seoul, he mocked my father in front of a dozen church leaders as a man led around by the nose by his wife.

It was difficult to know what accounted for the Moons’ shift in attitude toward my parents. Sun Myung Moon was at once attracted and repelled by intelligence and competence. No one should ever appear smarter than the Messiah. My father had built a successful company from the ground up for the Reverend Moon. That was good; he had served his master well. My father had accomplished this through his own skill and hard work. That was bad; he might take credit for Il Hwa’s success.

My mother was in an equally precarious position. A shy girl when she joined the Unification Church, she had become one of its most eloquent voices after years of preaching on Sun Myung Moon’s behalf. Well read, she had become a respected voice on matters of religion. Mrs. Moon, who had not finished high school before she married Sun Myung Moon, was uncomfortable around well-educated and pretty women like my mother. She insisted on being introduced in public as Dr. Hak Ja Han Moon, but the title was an honorary one.

Mrs. Moon’s insecurity was demonstrated by the kind of women she surrounded herself with in East Garden, Korean ladies I used to think of as her court jesters. They were there to entertain their mistress with jokes and foolishness, not to engage her in meaningful conversation. My mother was a breed apart. Smart and serious, she did not suffer fools. She was devoted to True Mother, but she did not play the role that Mrs. Moon most enjoyed.

The ladies around Mrs. Moon seized on her displeasure with my mother to further undermine her in True Mother’s eyes. Many of these women were eaten up with jealousy that the Hongs had married into the True Family. Jin and I, in their view, had taken the rightful places of their sons or daughters. Here was their opportunity for revenge. My mother’s every action was distorted by the rumor mill. A gift of money to a church member in need was misinterpreted as an attempt to buy someone’s affection. A defense of my father was read as an attack on the Moons.

In a medieval royal court, whoever whispered last into the ear of the king or queen had the most influence. It was no different in the Moon compound. The sycophants held sway. Soon there were rumors that my parents planned to establish a splinter church in Korea, that my father intended to declare himself the true Messiah. It was all nonsense, but the Moons were always willing to believe the worst. My father’s role in the Unification Church steadily declined at the urging of Mrs. Moon. To lessen his impact in Korea, Mrs. Moon eventually had the Reverend Moon appoint my father as president of the Unification Church in Europe, the continent where the movement had the least influence in the world.

The Moons’ mistrust of my parents spilled over into my life. I was told to minimize my contact with them. My calls through the East Garden switchboard to Korea were monitored to make certain that the Moons’ directive was obeyed. To be cut off from my family was more isolation than I could stand. I installed a private telephone in my room to maintain ties to my mother and father.

Two months after I returned to East Garden, our second daughter, Shin Young, was born. There was the usual disappointment that I had not produced a male heir, but there was relief, as well, that Hyo Jin’s abuse of drugs and alcohol had not damaged this beautiful baby girl.

A few months later, Mrs. Moon was preparing to return to Korea for an extended visit. She called me to her room and announced that she would be taking my four-year-old daughter with her to serve as a companion for her own five-year-old daughter, Jeung Jin. I did not dare voice my objections or ask all the questions I had. She did not indicate how long they would be gone. I barely had time to absorb this news when she returned from her closet safe with a Gucci handbag. It contained a hundred thousand dollars in cash. This was “seed money” for our family’s future, she told me. I should invest it wisely, perhaps in gold. Later, she said, she would give us another three hundred thousand dollars. Was she bribing me? Taking my daughter away in exchange for cash?

I begged Hyo Jin to intervene with his mother. I knew my daughter would not want to go. Jeung Jin was spoiled, and her baby-sitter was mean. My daughter and I were very close. She would miss me terribly. She was too young for such a trip. Hyo Jin refused to speak with his mother. If our daughter was in Korea, it would give him a convenient excuse to go there himself and visit his girlfriends. Besides, there was the money to think about from his mother. I was advised to store it in a safe deposit box in a bank in Tarrytown. Had I deposited it in a savings account we would have to do the unthinkable: pay taxes on it. The safe deposit box was a mistake, of course. It provided Hyo Jin with ready access to cash. He used the money that was earmarked for our children’s future to buy a thirty-thousand-dollar gold-plated gun for Father and motorcycles for himself and his brothers.

My little girl was in Korea for three long months. In the photographs Mrs. Moon sent home to East Garden, she was never smiling. When she left, she could hold a pencil and print her name. In Korea the baby-sitter slapped her hand and told her not to do that. Her aunt could not print her name, and the Moon children must be superior. It took me years to correct the damage. The baby-sitter would tell Shin June ghost stories that would give her nightmares. When she would ask to visit my mother, Mrs. Moon would distract her with a visit to a toy store or an ice cream parlor.

I vowed I would never let the Moons take any of my children from me again. The Moons brought the children on their speaking tours not because they loved their company but because they needed living ornaments, cutely outfitted decorations that would portray them as the loving parents and grandparents to the world. I would do whatever it took — flattery, manipulation, deceit — to stop Sun Myung and Hak Ja Han Moon from exploiting my children in the future.

My children were the one real blessing in my life. I defined myself as either pregnant or between pregnancies. I signed up for classes or dropped out of classes depending on my condition. In 1987 I was certain I was facing a second miscarriage. I was bleeding heavily in my fourth month. My doctor advised bed rest, but it did not stop the flow of blood. I was very frightened and I’m sure Hyo Jin heard as much in my voice when he called from Alaska, where he was fishing with his parents.

I was touched by the concern he expressed on the telephone but it had dissolved by the time he returned to East Garden. I was reading the Holy Bible in bed when he arrived at Cottage House. He knocked the Bible out of my hand. I put up my hands to protect myself from his blows. “Do you think the Bible is more important than True Parents?” he shouted. “Why weren’t you outside to greet them?” I tried to explain about the bleeding and the doctor’s orders but he was dismissive. If I was bleeding, then the baby was probably deformed, he yelled. It was better that I should miscarry than bring a damaged child into the True Family. I was appalled at his coldness. “Get up, you lazy bitch,” he shouted.

I tried to do as he asked but I was too weak. I stayed in bed and he stormed out of the house. I called my mother in Korea, who promised to have her prayer group pray for me and the baby. Days later, when the bleeding still had not stopped, I concluded that the baby must be dead. I packed a bag for my trip to the emergency room, anticipating that I would have to stay overnight after having a D and C. At the hospital my doctor performed an ultrasound. I was so resigned to an unhappy ending that I had to ask her to repeat herself when she said that the baby’s heartbeat was strong. The placenta had been bleeding, but it was beginning to heal.

That was the medical explanation, but I knew better. No baby could have survived the amount of blood I had lost. This was a miracle. When the doctor pointed out what else the ultrasound showed, I knew that this baby was a gift from God. I would bear a son. I told no one, not even my mother. When In Jin and Mrs. Moon asked later if I could tell the sex from the ultrasound, I said no. This was a secret between me and God. I felt that if I kept that secret, Satan would not try again to harm my baby.

The Moon household was ecstatic when I gave birth to Shin Gil on February 13, 1988. The Moons even softened temporarily toward my parents. Hyo Jin could not have been happier. A male heir strengthened his position as the rightful successor to his father. A son, the Reverend Moon hoped, would force Hyo Jin to accept his responsibilities to his family and to the Unification Church.

It was an idle hope. In April Hyo Jin made what was billed as a dramatic confession before a church gathering in the grand ballroom of the World Mission Center, the old New Yorker Hotel in New York City. It was Parents Day, a church holiday. “Many Blessed members blame Father for my wrongdoings. It is not Father’s fault; it is my fault,” Hyo Jin began. “It wasn’t easy for me to come to America. It was a spawning ground for my hate and misunderstanding. People tried to explain, but I never listened. I had a lot of anger in my heart. I hated almost everybody.”

He went on to detail his adolescent sexual encounters, his teenage drinking binges, his use of cocaine. But he led his audience to believe that these transgressions were all in his past. “I want to make sure none of these things happen to my brothers and sisters, to Blessed Children, to your children,” he said. What he didn’t say, of course, was that his drinking, his drug abuse, and his sexual promiscuity would continue unabated. “I want to do everything right from now on. That was the past and it comes and haunts me many times. I have told you everything, that I slept around, that I had many women. I have nothing more to tell you. Please forgive me.”

It was quite a performance before the membership. Hyo Jin was crying; his brothers and sisters were embracing him. I was merely a spectator at this sideshow. In his confession he had never even mentioned my name. He apologized to God, to True Parents, to church members, but he had nothing to say to his wife.

I was not surprised when this speech was followed by a resumption of his dissipated lifestyle. He began insisting that I accompany him to karaoke bars and nightclubs. I sometimes went just to avoid a fight, but I hated the atmosphere. Hyo Jin could sleep all day, but I had to rise early with the children. I had classes to attend. His drunkenness repulsed me. He would drink a half bottle of tequila and then leave a $150 tip for the waitress. I would sip my Coke and watch the clock.

I was not good company but I could drive home. Hyo Jin inevitably ran into trouble when he tried to drive himself. In 1989 the Moons had purchased an Audi for me to drive back and forth to college. One night Hyo Jin took the car into the city. I got a call near midnight that he’d had an accident and needed me to pick him up at Amsterdam Avenue and 146th Street. I could guess why he was in Harlem; that’s where he scored cocaine. He was not on the corner when I arrived so I drove around the area. I finally found him wandering several blocks away. He was drunk and incoherent. When I located the Audi, I was amazed that he had walked away uninjured. The car was a total loss.

With the insurance settlement, I leased a Ford Aerostar. It wasn’t long before Hyo Jin borrowed that car as well. At 4:00 one morning, I was awakened by a call from the New York City police. Hyo Jin had been arrested for driving while intoxicated. We were expected at a birthday celebration that morning for one of the Moon children. I sent my children with the baby-sitter and drove to the precinct house on 125th Street. In the next two hours, I reclaimed my car and arranged for a lawyer to represent Hyo Jin at his arraignment. I returned to East Garden to face True Mother, who scolded me for failing to attend the breakfast banquet. “Where were you? Where is Hyo Jin?” she demanded. This was his mess, not mine. I was tired of covering for him. “Hyo Jin is not here. When he comes home, I think you should ask him directly,” I said.

Hyo Jin returned to East Garden incensed that I had not gotten him released from jail sooner. He was furious to be told that Mother was waiting for him. He needn’t have been. The Moons took no action against their wayward son. The criminal justice system fined him, suspended his license, and ordered him to perform community service, but his parents did nothing to stem his drinking and driving.

The next time he asked me to accompany him to the bars, I refused. “I can’t go; I promised,” I told him. “Promised who?” he demanded. “Myself,” I said. He drove himself, without me and without his license.

170

Slowly I was learning to say no. More than any other factor, I think motherhood was responsible for my change in attitude. It was one thing to suffer the True Family’s abuse myself; it was another to subject my children to it. I gave birth to my third daughter, Shin Ok, in October 1989. I was twenty-three years old, with four children and a miscarriage behind me. I did not know how many more babies lay ahead.

I could defy Hyo Jin’s orders to accompany him to the bars, but I could not defy Mrs. Moon. In 1992 she told me I would accompany her on a ten-city tour of Japan. I was pregnant again, but I concealed my condition from my mother-in-law. My pregnancies were all that I had that were truly mine alone; I did not share them with the family of Sun Myung Moon until I had no choice.

The worshipful devotion accorded True Mother in Japan was beyond anything I had ever experienced in Korea. I had expected Mrs. Moon to be accommodated with the best hotel suites and the finest food, but what I saw in Japan was beyond pampering. Even her cutlery was kept separate, not to be used by anyone again, because it had touched True Mother’s lips. The slavish attention given to Mrs. Moon by the Japanese may have reflected their longing for True Father, who is banned from Japan because of his tax conviction in the United States.

Japan could fairly be said to be the site of the first imperial cult. In the nineteenth century, the Japanese emperor was declared a deity and the Japanese people descendants of ancient gods. State Shintoism, abolished by the Allies in 1945 after World War II, required the Japanese to worship their leaders. Obedience to authority and self-sacrifice were considered the greatest virtues.

It was no wonder, then, that Japan was fertile fund-raising ground for a messianic leader like Sun Myung Moon. Eager young Unification Church members found elderly people anxious to ensure that their loved ones came to a peaceful rest in the spirit world. To that end, they fleeced thousands of people out of millions of dollars for religious vases, prayer beads, and religious pictures to guarantee that their deceased family members entered the Kingdom of Heaven. A small jade pagoda could sell for as much as fifty-thousand dollars. Wealthy widows were conned into donating all of their assets to the Unification Church to guarantee that their loved ones would not languish in hell with Satan.

It was an extraordinary scene to witness. Church members waited on Mrs. Moon. Church leaders brought her stacks of money. At one juncture a member was styling my own hair when I noticed I had misplaced my watch. Within the hour a jeweler was in my hotel room with trays of expensive watches for me to choose from as a gift from our Japanese hosts. “Take several, take some for your family,” the jeweler insisted. I was relieved when I found my own watch and was able to politely decline their generosity.

Japan’s economy was booming. The country was fast becoming the source of most of Sun Myung Moon’s money. In the mid-1980s church officials claimed the Unification Church was pulling in four hundred million dollars a year through fundraising in Japan alone. The Reverend Moon used that money for his personal comfort and to invest in businesses in the United States and around the world. In addition, the church owned many profitable enterprises in Japan itself, including a trading company, a computer firm, and a jewelry concern.

Moon explained Japan’s crucial financial relationship to the Unification Church in theological terms. South Korea is “Adam’s country” and Japan is “Eve’s country.” As wife and mother, Japan must support the work of Father’s country, Sun Myung Moon’s Korea. There was more than a little vengeance in this view. Few Koreans, including Sun Myung Moon and his followers in the Unification Church, have ever forgiven the Japanese for their brutal forty-year occupation of Korea.

Members of the family of Sun Myung Moon were thoroughly scrutinized by customs agents whenever leaving Korea or entering the United States. This trip was no exception. One benefit of her enormous entourage was that Mrs. Moon had plenty of traveling companions with whom to enter the country. I was given twenty-thousand dollars in two packs of crisp new bills. I hid them beneath the tray in my makeup case. I held my breath in Seattle when customs agents began searching my luggage. I was the last of our party to go through customs, and the woman searching my bags seemed determined to find something. I pretended I did not speak English and could not understand her questions. An Asian supervisor came over and chastised her. “Can’t you see she only speaks Korean,” the supervisor said, smiling at me. “Let her through.”

I knew that smuggling was illegal, but I believed the followers of Sun Myung Moon answered to higher laws. It was my duty to serve without question. I did what I was told, worrying more that I might lose the money than that I might be arrested. I was so grateful to God that they didn’t find the money. In the distorted lens through which I viewed the world, God actually had thwarted the customs agents. God did not want them to find that money because that money was for God.

If I had thought about it with any critical sense, I would have realized that the money raised by street peddlers and pagoda sellers had little to do with God. Among other things, the money raised helped finance my husband’s adolescent fantasies of being a rock ’n’ roll star. With a group of church members, he had begun a recording career at Manhattan Center Studios, the church-owned facility next to the old New Yorker Hotel in Manhattan. The Reverend Moon bought the facility to promote a God-centered culture. The Metropolitan Opera, the New York Philharmonic, and Luciano Pavarotti recorded there. In 1987 Hyo Jin Moon began recording there, too. Rebirth was the name of the first album he cut, with second-generation Blessed Children Jin-Man Kwak, Jin-Hyo Kwak, Jin-Heung Eu, and Jin-Goon Kim.

Hyo Jin sold compact discs and tapes of his music to his only audience, the Unification Church, which included the Collegiate Association for the Research of Principles (CARP), which he served as the figurehead president. A campus student organization purportedly dedicated to world peace, CARP was just another recruitment arm and fund-raising tool of the Unification Church. Its most visible enterprise was the international Mr. and Miss University Pageant that CARP sponsored every year in different cities around the world.

Much of the money raised to do God’s work was squandered on Sun Myung Moon’s white elephant: the twenty-four-million-dollar personal residence and church conference center that he built on the grounds of East Garden. It took six years, and almost as many architects, to construct what might be the single ugliest building in Westchester County. We watched the building go through a dozen or more design changes and millions of dollars in cost overruns. What emerged was a stone and concrete monstrosity with a leaking roof.

The foyer and the bathrooms boasted imported Italian marble. The thick oak doors were carved with Korean flowers. There was a ballroom on the first floor and bedrooms for the Moons’ many small children on the second floor, down the hall from their parents’ lavish suite of private rooms. One of the two dining rooms had its own pond and waterfall. The kitchen was equipped with six pizza ovens. There was a third-floor game room and closets for Mrs. Moon’s clothes the size of a conventional bedroom. There was a dentist’s office and a turret that housed the office of Sun Myung Moon’s secretary, Peter Kim. The building was a monument to excess and nonsense. A bowling alley was located, not in the basement, but on the third floor, right above Sun Myung Moon’s bedroom. We used that room for storage. Hyo Jin, I, and the children moved into the mansion when True Parents moved into their new home.

At the end of 1992, Mrs. Moon told me I was to accompany her abroad again, this time on a European tour. I was battling exhaustion from my now advanced pregnancy and knew I would not be up to the demands of travel and waiting on True Mother. She and Hyo Jin were incensed when I declined to join her. What happened next, I know they saw as God’s punishment for my defiance.

I was scheduled for an ultrasound in January 1993. I knew from his vigorous kicks that the baby was strong. I smiled at the flailing legs and arms on the ultrasound monitor. “Looks good,” the doctor said as he ran the probe across my distended belly. Soon, however, the doctor’s smile faded. “We have a problem,” he said softly. His face was so troubled I knew I did not want to know the answer to the question I had to ask. “What’s wrong?” A few seconds seemed like hours before he said, “This fetus does not have a brain.” “What? How can the baby be kicking if it has no brain?” The kicks were only a reflex. The baby had no chance for survival outside the womb.

I cried so hard that the doctor led me out through a rear door. I’m sure I would have made a terrifying picture for the other pregnant women in the waiting room. I sat in my car for a long time before I was composed enough to drive home. When I came home, Hyo Jin was locked in the master suite. I knew what that meant. He was sniffing cocaine. I called my mom. I couldn’t be specific. All I could say was: “There’s something terribly wrong with the baby,” whose kicks I could still feel in my womb.

My doctor and I agreed that it would be awful for my children if I gave birth to a baby we knew would not live. I got a second ultrasound from another doctor just to be sure that there was no mistake. I drove myself to the hospital where the abortion was to be performed. Hyo Jin did not want to come. The pain, and the terrible sense of loss, were more than I anticipated. I had to call and ask him to pick me up. He seemed annoyed at my tears during the silent drive home. I moved into Shin June’s room. I was lonely and angry. Why had this happened? Had Hyo Jin’s drug abuse caused this? Was God punishing me for failing to bring Hyo Jin back to him?

Mrs. Moon was upset because I had not shown up to serve them at table. I begged Hyo Jin not to tell his parents the details of our loss. It was personal. “Can’t you just tell them I had a miscarriage?” I pleaded. In Jin had just had her fourth baby, and it was like a knife in my heart to hear her newborn crying in the house we shared. “You want me to lie to True Parents?” Hyo Jin asked indignantly. I only wanted some privacy, but I should have known that was too much to expect in the Moon compound. He told True Mother everything.

My secrecy enraged Mrs. Moon. It confirmed my untrustworthiness. I was duplicitous, a tool of my parents, who were trying to undermine the work of True Parents. The drumbeat of criticism against me and my parents became incessant. At Sunday-morning services, I would be vilified as the daughter of tools of Satan. I did not mind so much for myself but I hated for my children to have to listen to such ugly lies about their grandparents.

My mother and father were decent people who had devoted their lives, and the lives of their children, to Sun Myung Moon. The reward for their misguided self-sacrifice was public scorn. In 1993 my father suffered a stroke and was removed by the Moons from his position as president of the Unification Church in Europe. He went home to Korea, where he was ostracized by the religious movement that he and my mother had helped build.

Hyo Jin was emboldened by Father’s attacks on my parents. In response he stepped up his attacks on me. By 1993 Hyo Jin’s use of cocaine was constant. He locked himself in our master bedroom suite for days on end, forcing me to keep extra clothes in my children’s closets and to share their bedrooms.

One evening, after he had spent the entire week snorting cocaine and watching pornographic videos, he summoned me to his room but I refused to go. He came downstairs, screaming and yelling obscenities, into a room we used for church-related classes. He flipped the coffee table over onto its side and forced me into a corner of the room, pushing me up against the wall, his face only inches from my own.

I ran for the telephone to dial 911. “I’m calling the police,” I warned, but he just slapped the phone out of my hand. “How dare you try to call the police on me?” he shouted. “They have no authority here. Do you think I’m afraid of the police? Me? The son of the Messiah?”

I did not know what he would do next, so I began shouting for help as loud as I could. The door to the classroom was wide open. I knew the security guards, the kitchen sisters, the baby-sitters, could all hear me. No one came. Who would have the nerve to stand up to Hyo Jin Moon? Who would protect me from the Messiah’s son? He laughed at the futility of my screams and left the classroom in disgust. I called my brother Jin and told him I was going to the police.

I stumbled into the foyer in tears. There, huddled together on the staircase, were three of my four children. They were sobbing. “Don’t leave, Mommy,” they cried, as I headed for the front door. “I’ll be right back. Don’t worry,” I whispered as I dried their tears.

I drove straight to the Irvington Police Department. Once I pulled into the parking lot, though, I didn’t know what to do or why I had really come. I was still shaking, with fear and with rage. I sat there for a long time, praying for God to guide me. I had spent the last eleven years hiding my feelings, concealing the facts of my life from the outside world. What was I doing parked outside a police station? I was crying when the police officer looked up from the front desk. “I think I need some help,” I said. He took me into a private back room and listened quietly while I told him what had happened. He recognized the street address. He knew the family name. I could tell he was not surprised.

Did I have any place to go? he wanted to know. Did I have any family? I had only my brother Jin, who was a student at Harvard. I did not want to involve Jin and Je Jin in this. She had her own problems with her parents; I did not want to drag her into mine.

The policeman was patient and kind. He described my options: I could file assault charges against Hyo Jin; I could take my children to a shelter for victims of domestic violence. I thanked him but I knew in my heart that I could do no such thing. I was able only to file a report with the police. I did not lack the desire to flee; I lacked the courage. I was terrified to go back to East Garden, but sitting there in the Irvington police station, I was more certain than ever that I had nowhere to run.

Chapter 9

page 179

By 1994 my only ambition was to see my children grown so that I could leave my husband. I knew that Sun Myung Moon would never permit me to divorce Hyo Jin, but I fantasized that one day we could at least live apart. I dreamed of a time when I could live alone quietly in a small apartment, somewhere far from East Garden. The children would bring my grandchildren to visit me. I would be at peace.

It was a pathetic goal for a twenty-eight-year-old woman. I had just earned my undergraduate degree from Barnard College in art history, but I was writing off the next twenty-five years of my life. My passion for art, my vague thoughts of museum or gallery work, faded away, as dreamlike as the Impressionist paintings I favored.

In March I learned that I was pregnant again, and the joy I usually felt at the prospect of a new baby was this time mixed with dread. Each new birth would extend the length of my imprisonment.

It was a mystery to me how such precious lives could spring from such a poisonous union. It was my children who made me whole. With them I felt light and carefree. Their routines provided us with the only semblance of a normal life. I drove them to music and language lessons in a Dodge minivan just like other suburban moms; I helped them with their homework; I snuggled up with them at bedtime to read stories and to hear their daily concerns.

Too often, their worries were about their father. Nothing that went on in East Garden escaped the notice of our older son and daughters. Hyo Jin’s drunken rages, his cocaine stupors, his volatile temper, were impossible for them to overlook. They were awakened in the middle of the night by the sound of us fighting. They questioned why their father slept all day. “Why do we have a bad dad?” the older ones would ask. “Why did you marry him?”

I was grateful that Hyo Jin stayed away as much as he did, working at Manhattan Center Studios and sleeping at our suite in the old New Yorker Hotel. It reduced the tension in the mansion, which we now shared with In Jin and her family. The children and I managed some happy, even silly, hours together. One spring I had taught myself to ride a bicycle in the mansion driveway, to the great amusement of my more competent children.

Manhattan Center, which was originally built in 1906 as the Manhattan Opera House by Oscar Hammerstein, had become the focus of Hyo Jin’s life. The Unification Church had purchased the property, along with the New Yorker Hotel next door, in the 1970s. Manhattan Center was little more than a practice hall when Hyo Jin had taken charge of the production studios and the business operation in 1985. I was surprised that Sun Myung Moon had entrusted such a major enterprise to a son who had neither the education nor the experience — to say nothing of the discipline — to act as a chief executive officer. I should not have been. All over the world, when the Unification Church acquires new businesses, those enterprises serve as employment opportunities for the family of Sun Myung Moon.

For the first time in our marriage, for the first time in his life, Hyo Jin Moon at age twenty-six had a job. He supervised the production of videos for the church and he continued to record with his band of church members. I was no fan of rock music, but it was certainly true that Hyo Jin was a talented guitarist with a beautiful voice. He loved his music; it was the one unspoiled pleasure he had in life.

His employees at Manhattan Center were all members of the Unification Church, even though Manhattan Center Studios claims to be an independent corporation with no overt connection to the church. His employees accorded Hyo Jin the respect and loyalty due the son of the Messiah. With him they turned Manhattan Center into a sophisticated multimedia studio, with professionally run audio, video, and graphics departments. Hyo Jin’s elevated spiritual standing made for strained work relations, however. Imagine answering to a boss you could not question, who interpreted any hesitation to carry out his orders as a sign of betrayal. It was a recipe for disaster.

Money flowed in and out of Manhattan Center in what could generously be described as a liberal and informal fashion. Some weeks employees did not get paid because Hyo Jin had earmarked the thousands of dollars sitting in the safe for the purchase of new equipment. Most lived rent-free in the New Yorker Hotel next door. When Manhattan Center’s conventional sources of revenue — studio bookings and ballroom events — fell short, Hyo Jin would tap a church organization, such as CARP, to pay for a new video camera or the electricity bill. Personal “donations” to Hyo Jin financed the building of new studios and recording facilities. Church funds, channeled to Manhattan Center from True Mother, were recorded on the books as “TM.”

Manhattan Center became the fuel that powered Hyo Jin’s moral collapse. It was a source of ready cash to finance his cocaine habit, his growing arsenal of guns, and his nightly drinking binges. Manhattan Center provided Hyo Jin, who hated to drink alone, with a stable supply of drinking companions, all of whom had no choice but to attend to this True Child.

Most members of the Unification Church get no closer to the True Family than the distance between the stage and their seats at some rally. For the staff of Manhattan Center, the opportunity to work directly with Hyo Jin Moon was a matter of great pride. It soon became a source of spiritual conflict for many of them, however. He would order his inner circle to accompany him to Korean bars in Queens, where he cavorted openly with “hostesses” and drank himself senseless. He pressured people to take cocaine, people who had been drawn to the Unification Church because of its prohibitions against the very acts of self-destruction in which Hyo Jin was engaged.

As his cocaine abuse escalated, so did his belligerent behavior toward his staff and his family. His verbal abuse of me had grown from obscenity-laden insults to threats of physical harm. He would open the gun case he kept in our bedroom and stroke one of his high-powered rifles. “Do you know what I could do to you with this?” he would ask. He kept a machine gun, a gift from True Parents, under our bed. At Manhattan Center, those who displeased him became accustomed to hearing graphic descriptions of the violence that would come to them if they betrayed Hyo Jin Moon. An accomplished hunter, he once detailed for a gathering of his inner circle exactly how he would like to skin and gut a member of his staff who had recently left Manhattan Center.

It is difficult for anyone outside the Unification Church to understand the bind those close to Hyo Jin at Manhattan Center found themselves in. On the one hand, their leader was engaging in activities that were inimical to their beliefs. On the other hand, he was the son of the Messiah. Perhaps he had some special dispensation to act as he did. If they did not obey and join him in proscribed behavior, were they substituting their own inferior judgment for that of a True Child? Should they be honest with the Messiah or loyal to the son of the Messiah? Would they be protecting Hyo Jin Moon by exposing him or by shielding him?

Even if one or more of them had had the independence of mind to question Hyo Jin’s actions, unlikely given the authoritarian nature of the church, who would they have told? One doesn’t just call up East Garden and ask to speak to Sun Myung Moon. Even if a member tried to make an appointment to see Mrs. Moon, that information would soon be public knowledge. Hyo Jin would not have been pleased to discover that one of his trusted advisers had gone to True Parents to inform them that their son was an alcohol-abusing, drug-addicted womanizer.

On the contrary, the inner circle had enough experience with Hyo Jin’s unpredictable temper to go to any lengths to appease him. He terrorized his workers, reminding them whenever they displeased him that he was “a mean son of a bitch,” one of his favorite self-descriptions.

No one was learning that better than I. In September Hyo Jin beat me severely after I found him taking cocaine with a family member in our bedroom at 3:00 a.m. I could not contain my anger. “Is this how you want our family to live?” I asked him. “Is this the father you want to be to our children?” I told him I could not live like this anymore. I tried to flush the cocaine down the toilet, spilling some on the bathroom floor in the process. He pushed me to the floor and made me sweep up what white powder I could retrieve. He smashed his fist into my face, bloodying my nose. He wiped my blood on his hand and then licked it off. “Tastes good.” He laughed. “This is fun.”

I was seven months pregnant at the time. While he punched me, I used my hands to shield my tummy. “I’ll kill this baby,” Hyo Jin screamed and I could see he meant it.

The next morning my tearful children gave me ice for my blackened eye and hugs for my battered spirit. I can’t say Hyo Jin hadn’t warned me. How often had he told me that there was a deep well of violence inside him? “If you push me too far, I won’t be able to stop myself,” he would say. I knew now that he was not exaggerating.

Hyo Jin felt no regret for the beating he had administered. He told his inner circle at Manhattan Center later that he smacked me because I had been “bugging” him and that I reminded him of a teacher he had once had at school, who always tried to humiliate him in front of the class. I was a pious scold, he said, a self-righteous bitch.

As strong as his contempt was for me, it did not approximate his hatred of his Father. He loathed and loved Sun Myung Moon in equal measure. He mocked him in front of me and in front of his associates at Manhattan Center as a senile old fool who should know his time to leave; he denounced him as an uncaring father who had never had time for his children. He blamed his father for the taunts of “Moonie” hurled at him by his American classmates when he was a boy. He resented the burden of being the heir apparent to the Unification Church, but he chafed even more at his own inability to live up to his father’s expectations. He kept a gun at Manhattan Center, whose security chief often purchased weapons for him. When he was high, Hyo Jin would wave the gun around wildly and threaten to shoot his father if Sun Myung Moon ever tried to interfere with his control of Manhattan Center.

That control was absolute. He used Manhattan Center money as if it were his own and had his own paycheck deposited into a joint account with Rob Schwartz, his financial adviser at the company. Manhattan Center was there to serve his every whim. In 1989 and again in 1992, he had instructed Schwartz to buy a new Mercedes for Father with company funds. On another occasion he purchased an eighteen-foot fishing boat and trailer for the use of the extended Moon family. What those cars and that boat, all of which were kept at the compound in Irvington, had to do with the business of Manhattan Center was anyone’s guess.

The casualness with which Hyo Jin mingled his personal funds and church money and business accounts would have intrigued the Internal Revenue Service. In 1994 he ordered Rob Schwartz to give one of his younger sisters thirty-thousand dollars. There was internal debate at Manhattan Center about how best to disguise this transfer of funds. In the end, proceeds from the Mr. and Miss University Pageant held at Manhattan Center were kept off the books and thirty-thousand dollars was handed to Hyo Jin to give to his sister. The year before, a group of Japanese members of the Unification Church was touring the United States. On a visit to Manhattan Center, they made a personal “donation” to Hyo Jin of four hundred thousand dollars in cash. He kept some of the money and used the rest for pet projects at Manhattan Center. He never reported the gift on his tax return or paid a dime of taxes on the money.

In February 1994 Hyo Jin carried a Bloomingdale’s shopping bag into Manhattan Center containing six hundred thousand dollars in cash. I had helped him count out the money earlier in the day in our bedroom. He gathered his inner circle of advisers in his office, and while their jaws dropped open, Hyo Jin asked if they had ever seen so much money. What he didn’t tell them was that he had skimmed off four hundred thousand dollars for himself of the one million dollars Father had given him to finance Manhattan Center projects. Hyo Jin stashed the money in a shoebox in our bedroom closet. By November he had spent it all, mostly on drugs.

It is probable that Sun Myung Moon did not know until November of 1994 the extent to which Hyo Jin had turned Manhattan Center into his personal petty cash drawer and the family suite on the thirtieth floor of the New Yorker into his private drug den. He did not know because he did not want to know. The Reverend and Mrs. Moon had set the tone for their parental relationship with Hyo Jin back when he was a boy, expelled from school for shooting at classmates with a BB gun. On that occasion, and in every troubling incident since, they had not forced their son to accept responsibility for his actions. He grew up believing that there were no consequences for his misdeeds, and his parents, and the church hierarchy, did nothing to disabuse him of that notion.

That fall, for instance, Hyo Jin had been a guest speaker in a course called Life of Faith at the Unification Theological Seminary in Barrytown, New York, where he was enrolled as a part-time student. Another student asked Hyo Jin a general question about his remarks and Hyo Jin took offense. Without a word he walked over to where the student was seated and began punching him. The student remained seated and did not strike back.

Hyo Jin received two letters from Jennifer Tanabe, the academic dean, after the incident. One was a joint letter of reprimand to Hyo Jin and the student he assaulted, Jim Kovic; the other was a personal note to Hyo Jin advising him to disregard the official letter. “Please understand that my intention in addressing this letter to you, as well, is not to accuse you but to protect you against any possible accusation. I will do my very best to support you. This is my determination before God,” she wrote, incredibly ending her note with an apology to a man who had beaten up a student in one of her classrooms. “I am sorry to bring such bad memories of your experience at UTS. I hope that in the future you will find UTS to be somewhere that can bring you joy and inspiration.”

By November Hyo Jin was about to run out of excuses and defenders. The month began with the birth of our second son and fifth child, Shin Hoon. Hyo Jin was out at the bars when I went into labor, so I drove myself to the hospital with the baby-sitter in the passenger seat. I wanted her to learn the way so that she could bring the other children to visit me and their new brother. Before we left I put the children to bed. I told them I was going to the hospital to have the baby and that they should go to school the next day without telling anyone where I was. My desire for privacy in the suffocating world of the Moon family had become paramount. I called my brother Jin in Massachusetts to let him know I was on my way to Phelps Hospital and to ask him to call our parents in Korea.

I didn’t care that Hyo Jin was not with me. This was my baby, mine and my children’s. He had nothing to do with us as a family. If he preferred the company of barmaids, why should he be there for the birth of my son? At 4:00 a.m., when I was told I needed a cesarean section, my doctor insisted I call my husband. He was asleep. He assumed I was in one of the children’s rooms down the hall. He urged me to come and service him sexually. He was startled to hear that I was about to be wheeled into the operating room. He was too tired to come, he said. “What hospital is it anyway?” he asked. This was our fifth child and he did not know where they were all born? I was enraged. I did not answer. Hyo Jin began yelling. I hung up, but after I calmed down, I called back. “Forget it,” he said coldly. “I’m not coming. You can bring the baby to me.”

I saw my first glimpse of “Hoonie” through my tears. A nurse kept wiping my eyes as the doctor lifted this big boy, almost nine pounds, from my womb. He had a full head of black hair. The umbilical cord had been wrapped around his arm, complicating a natural delivery. His eyes were half closed but he had a healthy wail.

Hyo Jin did not come to see him for two days. His pride and his indifference kept him away. I was as stubborn as Hyo Jin, but I called to ask him to see his son. He stayed for only a few minutes with me and viewed Shin Hoon through the nursery window. He never asked to hold him. That night the babysitter brought my children. I was so happy to see them. They all posed for pictures with their new baby brother and begged me to come home soon.

I came home the next day, though the doctors wanted to keep me longer because of the surgery. I did not want anyone in the Moon compound to know I had had a cesarean section. It was such an anomaly to be in possession of information the Moons did not have; I wanted my surgery to be my secret. Hyo Jin came with the children and the baby-sitter in two cars to pick us up at the hospital. When it took longer than he had patience for to adjust the infant seat, he took off with Shin Gil for home, leaving me to ride with the baby-sitter. That night Hyo Jin announced he was going to New York. What I did not learn until later was that my husband had chosen the very day I brought our baby home from the hospital to take a lover. He slept with Annie, an employee at Manhattan Center, in our bed in our suite in the old New Yorker Hotel.

I knew Annie from the dozens of letters she had written to Hyo Jin since she first saw him at a church martial arts demonstration in Colorado several years before. Her letters read more like fan mail than anything else. Hyo Jin often got similar letters from young people in the church, men and women, who looked up to him as the son of the Messiah. I never took Annie’s infatuation with Hyo Jin seriously. An American herself, she was married to a Korean member and they had a young son. Annie had come to New York that year to work for Hyo Jin at Manhattan Center after appealing to him to bring her and her husband back from Japan, where they were stationed for the church.

Hyo Jin talked about her often, but I did not suspect the nature of their relationship initially. Maybe I did not want to see what was becoming more and more obvious to everyone else around them. I worried more about his dependence on cocaine. He was closeted in his room all the time that he was not at Manhattan Center. As it turned out, I was not alone in my concern.

Twenty-one days after the birth of a child, we hold a prayer service in the Unification Church to give thanks to God for the health of our baby. I held an informal service with my children. Hyo Jin had been out drinking all night and had not returned. His sister Un Jin came by that afternoon to see the baby. We had not been close for years, but I would never forget the kindnesses she showed me when I first came to East Garden.

She confided that she was worried about Hyo Jin. He had lost a lot of weight. He wasn’t eating. Did I think his problems with booze and drugs had gotten worse? Did I think True Parents should send him to rehab? I told her what I saw of his deteriorating lifestyle, but I expressed skepticism that he would voluntarily confront his addictions.

The very next day, Hyo Jin threw a Thanksgiving party at Manhattan Center for the staff. He served wine. Only his inner circle really knew about Hyo Jin’s drinking and cocaine use. The rest of the staff were shocked to see alcohol at a church function. When the Reverend Moon found out, he ordered the staff at Manhattan Center to meet with him, without Hyo Jin. He reminded them that Sun Myung Moon was the leader of the Unification Church; they were to support Hyo Jin by keeping him away from dangerous situations.

I called Hyo Jin’s assistant, Madelene Pretorius, to find out how the meeting went. We did not know one another well. We had met only once, when she came to videotape the children at a school play. She told me what Father had said and admitted that they had not told the Reverend Moon or me the whole truth. He had asked them if they smoked or drank with Hyo Jin and no one had admitted it. The truth was, she said, that they smoked and drank with him all the time in bars and in our suite at the old New Yorker Hotel.

I was horrified. What he did to himself was bad enough, but to drag other church members into the sewer with him was unforgivable. That he used our apartment to engage in this behavior enraged me. This was the beginning of the end of my marriage, though I didn’t know it then. Something in me was about to snap. I had accepted that it was my fate, my divine mission, to live a life of misery with this evil man. But I could not accept that the members of a church I still believed in were condemned to be led into sin by Hyo Jin’s abuse of power.

I called him at Manhattan Center. I was much braver on the telephone than I would have been in person, where he might have beaten me. I told him on the telephone that I thought he was an animal, that the children and I did not want him to come home.

It was a shortsighted reaction on my part, because, of course, he did come home, and when he got there he came looking for me. In my fury, I had already cleaned out his closets, packed his bags, cut his pornographic videos into shreds, and stacked it all in the storage room down the hall. I heard the front door slam. He ran up the stairs, grabbed me by my shirt collar, and dragged me into his room. He pushed me roughly into a chair, shoving me back down whenever I attempted to stand. “How dare you try to embarrass me in front of people at M.C.?” he screamed. “Who are you to tell me what to do?” He stood over me, slapping me and pushing me the whole time. I had no avenue of escape.

I was saved only because he was late for a meeting with his probation officer. He was still on probation for drunken driving. He tried to call and cancel the appointment, pleading a family emergency, but his probation officer insisted he come. He had missed too many appointments. “When I get back, I want a family meeting,” he told me. “You are going to tell the children that you were wrong to criticize Dad, that Dad is free to smoke and drink beer, that you are a bad mother. Do you understand?” I said that I did. I would have said anything to get him to leave.

No sooner had he gone than I got a telephone call from Mrs. Moon’s maid. “Father wants to see you right away,” she said. I thought I was about to be lectured again for failing to help my husband find a righteous path. I had had enough; it was time for me to take the initiative. The rising level of abuse had emboldened me somehow. I had not consciously decided that I was not going to take his beatings anymore, but that night, in the Moons’ study, I stood up for myself for the first time.

“Father wants to speak with you,” Mrs. Moon said as I entered their suite. “Could I please talk with you both?” I asked. “There is something I need to tell you.”

The Reverend and Mrs. Moon listened in silence as I described the scene that had just transpired. “It is not just me and the people at M.C. who are being affected,” I said. “Hyo Jin wants me to tell the children that his use of alcohol and drugs is O.K.” That was enough to spark a reaction in Father. “No. No,” he said, “you have to teach the children right from wrong.” I kept looking at my watch. I told True Parents I needed to get back before Hyo Jin did from his meeting with his probation officer.

The Reverend Moon was quiet for a few minutes: “I am going to send you to M.C. to keep an eye on him. You are to be his shadow. I will put you in charge. You can make sure he does not use money for drugs and drinking.”

I was surprised, but I knew that his use of me as his eyes and ears at Manhattan Center had less to do with his faith in my ability than with his certainty of my loyalty. The staff at Manhattan Center owed an allegiance to Hyo Jin; I followed True Father. He was right in the short run. In the long run, as we were all to discover, I realized that my ultimate loyalty was to God, my children, and myself.

When I returned to the mansion, Hyo Jin had not yet returned. I called our oldest child to my room. “Dad wants a family meeting,” I told her. “I’m going to have to say some things I don’t believe, because otherwise your dad will get very angry.” She was appalled that I would even consider saying what he demanded. “You are not a bad mom. You are a good mom. You can’t say what he does is O.K. when you know that it isn’t.” I could see that she was disappointed in my willingness to compromise the truth. I was ashamed in front of my twelve-year-old daughter, whose sense of justice was finely honed at a young age. I was selfish. I wanted to avoid more violence, more screaming. When he returned and asked me to tell the children I had been unfair to Dad, I did it. My daughter’s eyes filled with tears, but she was not sad. She was angry. “That’s a lie,” she yelled at her father. “Mom is good. She is with us all the time. You are never here. What do you know?” Hyo Jin turned his fury on her, denouncing American schools for breeding disrespectful children.

I felt like a coward witnessing my little girl’s courage. When Hyo Jin calmed down, he told her he had to spend time away from the family to pursue his mission for the church. I could not help but think of the irony: this was the excuse he had so despised when it came from his own father.

I was surprised that, despite his angry protests, Hyo Jin accepted my new role at Manhattan Center. He did not suspect why Father had placed me there, and since he had so little respect for me, he probably thought my presence would be no threat to him. He soon learned otherwise. As one of my first directives, I set up a meeting between Hyo Jin’s inner circle and Sun Myung Moon at East Garden. The Reverend Moon told them as explicitly as he could that they were not to take drugs with Hyo Jin or to drink with him. They were to give their allegiance to Father, and at Manhattan Center they were to follow my directions, not Hyo Jin’s.

As angry as I was at Hyo Jin, I was still susceptible to his accusation that it was my lack of understanding and support as a wife that led him to drink and abuse drugs.

If I was responsible in some way, I had to try one more time, with all my heart, to make things right, if not for us then for God. I spent all of my free time in December in Hyo Jin’s company. I went with him everywhere. I sat with him at home while he snorted cocaine.

The drug loosened his tongue and I listened for hours to his stream-of-consciousness pronouncements about God and Satan and Sun Myung Moon. The more I heard, the more convinced I became that Hyo Jin had no real sense of right and wrong. It was sad to hear him devise pathetic excuses, to tailor his morality to suit his circumstances.

His drug-induced monologues invariably portrayed him as the victim of his parents’ neglect, of his wife’s harsh judgment, of the church’s unrealistic expectations. I listened for any hint that my husband was capable of taking some responsibility for the bad choices he had made and was continuing to make.

I heard nothing of the kind. All of Hyo Jin Moon’s problems were the fault of others. As long as that was his attitude, how could he ever really serve God? How could he ever really be a good father to our children?

At Manhattan Center I set about trying to get the company’s financial and spiritual house in order. I instructed Hyo Jin’s assistant, Madelene Pretorius, that there were to be no more “petty cash” payments of hundreds of dollars at a time to Hyo Jin. Staff members who were paid huge salaries for little work were to be reassigned. All major decisions would have to be approved by me.

I had another mission at Manhattan Center as well. I was determined to find out whether Hyo Jin and Annie were lovers. Madelene suspected they were. Even my brother-in-law Jin Sung Pak had hinted there was something going on between them. I asked Hyo Jin directly many times, prompting the denials I expected but did not believe. After I began working at Manhattan Center, he taunted me about their ambiguous relationship. “Why do you worry about Annie?” he would ask, as if he were baiting me.

At the end of December, I decided I would hammer away at this topic until he confessed. It took hours of gentle coaxing for the truth to emerge. “No, I did not touch her,” he insisted at first. “Well, maybe I kissed her,” he conceded. “Maybe we had oral sex.” His rationalizations got more strained the more impropriety he was willing to admit. “I did penetrate her, but I didn’t ejaculate so it doesn’t count,” he said, before finally confessing: “I did ejaculate, but it doesn’t matter because she is on the pill,” I wondered if this guy even knew how pathetic he sounded.

I was very calm as he described his betrayal of our family. I had known in my heart all along; his confession was just confirmation. He began to cry and beg my forgiveness. I told him I would try to forgive but that I would not sleep with him until he had paid for his sin. “Why Annie?” I asked impulsively. “She’s not even that pretty.” It was as if I had held a match to gasoline. He exploded in rage: “She’s beautiful!” he yelled. “She’s not the only one. All the women in the church want me. I’ll fuck the prettiest girl I can find. I’ll show you.”

I was numb. This was the man who claimed to be the son of the Messiah, a man who had stood up at a church service a few years before and preached about the sacredness of the Blessing. “How can you connect to the Messiah if you are indulging and wallowing in the sensuality of the fallen world? You can’t. That’s why the idea of sacrifice has been promoted and endorsed,” he had told a Sunday-morning gathering at Belvedere.

“If Father told you to go out of this room and go to bars, get loaded and go to the streets where prostitutes walk and dwell among them, are you strong enough, do you love Father enough to overcome the kind of temptation that you might or might not expect there? Could you keep your purity and integrity? Could you truly do that? Living in that environment for the sake of changing the people is a good reason for living there. But do you know Father enough to overcome the temptation of touching a woman, of looking at beautiful women, or being intoxicated where your ability to make a sensible decision becomes weaker and weaker? Under that circumstance can you hold on to Father? Are you strong enough not to abandon Father regardless of the circumstances?”