#The exploration of being diaspora in a foreign country & experiences of racism & her relationship with her mother was probably the most

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

2024 reads / storygraph

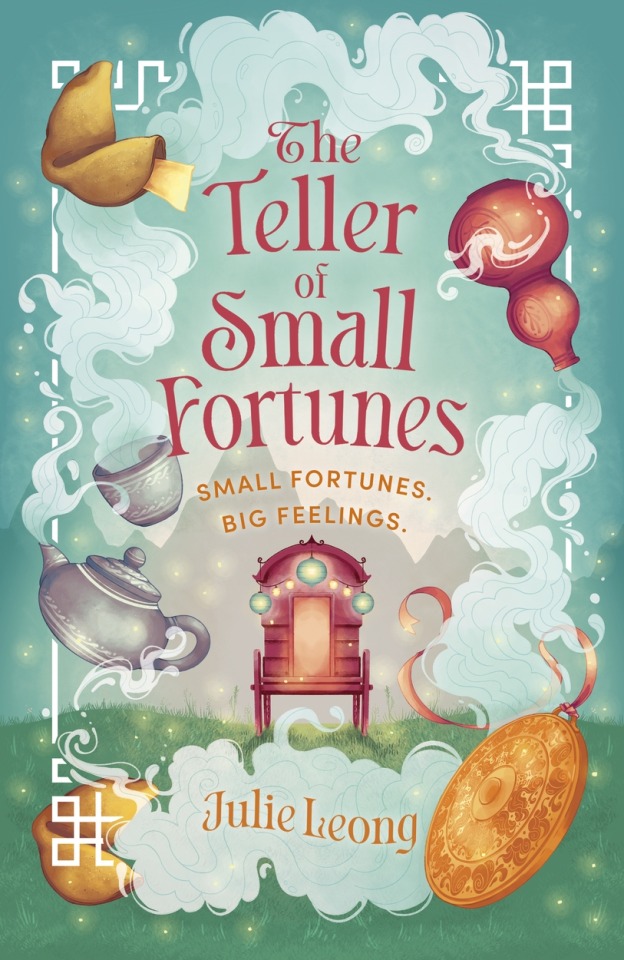

The Teller of Small Fortunes

lighthearted fantasy adventure

follows an immigrant fortune teller who travels between villages telling small fortunes for people

when she runs into a (mostly reformed) thief and an an ex-mercenary searching for his lost daughter, she ends up traveling with them in the hopes she can help, along with a baker they meet along the way,

they encounter various magical creatures and adventurous situations, and eventually she has to face her past

no romance

#The Teller of Small Fortunes#aroaessidhe 2024 reads#this was okay#to be honest I didn’t get very attached to any of the characters - I found most of them a bit one dimensional.#(I kept forgetting the cat even existed - why keep mentioning the magical cat in the promo if it’s barely there!!!)#And not feeling much for the characters meant I struggled to feel much about everything else about the story honestly#The exploration of being diaspora in a foreign country & experiences of racism & her relationship with her mother was probably the most#interesting to me.#I always give cozy fantasy a chance but honestly I need it to be deeply introspective or maybe like really funny#it’s just a bit too light for me? (other than the racism and xenophobia - I’m glad to see more of that in this space)#It’s just I think not deeply enough for me - and combined with not feeling attached to the characters I just wasn’t feeling it#Also one of the reasons I picked this up was because I was seeing people say it has an asexual MC and let me just say-#it has a very vaguely AROace CODED mc#If you’re looking for it there’s a few lines of implications but it’s not super clear and also any mention is romance related - aro! not ac#There were SO many instances that would have been an opportunity to bring up aro/aceness and the choice to not do that#felt sightly strange to me?. however tdlr readers could be promoting this on it having no romance and focusing on#friendship/family instead of saying it has an ace MC which is….only there if you squint#no romance#***other than side characters being married and also:#There’s a minor subplot where a side character has a crush on another SC which is unrequited#and there’s a bit of a confrontation after which he backs off. but then it’s implied they might get together in the end :(#which was unnecessary! come on!#I always find fantasy characters inventing real life foods slightly odd but at least this one is more from the author’s culture#anyway. it's okay! just didn't really end up being for me

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Q&A with Candice Whitney and Barbara Ofosu-Somuah, editors/translators of “Future. il domani narrato dalle voci di oggi,” edited by Igiaba Scego

A few weeks ago we announced on the WiT Tumblr an upcoming program at Casa Italiana NYU, “Stories Without Borders: A Conversation with Igiaba Scego,” hosted by Candice Whitney and Stefano Albertini, which you can watch here on YouTube. In an engaging and wide-ranging conversation, Scego talked about Italy’s colonial past in Africa, racial politics and systemic racism in Italy, the need for diversity in Italian publishing, and her reactions to the killing of George Floyd. Scego also discussed her reasons for editing the groundbreaking anthology of writings by AfroItalian women, Future. il domani narrato dalle voci di oggi [Futures. Tomorrow Narrated by the Voices of Today], published in 2019, which co-host Candice Whitney is currently translating with Barbara Ofosu-Somuah. (Candice is on the left and Barbara on the right in the photo above.) I followed up with Candice after watching the event to inquire about the Future anthology and about the translation project (which is currently seeking a publisher). Over several emails in July she and Barbara shared with me more details about the anthology and its writers, their personal encounters with Italy and the Italian language, and their commitment to creating a space for AfroItalian women writers in the English-language literary world.—Margaret

How did the Future anthology originate?

Candice Whitney and Barbara Ofosu-Somuah: Igiaba Scego, historian, journalist, fiction writer, and activist, wanted to create a text that acknowledges the future of Italy. The nation’s colonial legacy has shaped its national identity, citizenship laws, and how it relates to Blackness. For example, immigrants and their children, regardless of if they are born and/or raised in the country, are still othered as foreigners due to lack of citizenship reform.

A small publishing house in Florence, Italy, effequ, reached out to Scego to curate an anthology about migration. She had already edited and worked on influential anthologies related to migration, such as Italiani senza vocazione (Edizioni Cadmo, 2005). Ubah Cristina Ali Farrah, whose literary work connects the present day to the experiences of Somali relatives who moved to Italy, is an example of an artist that Scego collaborated with and admires. However, Scego wanted to pursue a different focus for effequ.

Reflecting on the double-consciousness of her life, specifically experiencing migration through the memory of her parents and living in Italy, Scego wanted to read and share perspectives of women similar yet different from her. The concept of Future was born from this idea. She chose to incorporate perspectives from writers of different generations, and from large and small cities across the nation.These authors write across genres. With this anthology, Scego highlights the diversity of the African diaspora in Italy. Contributors have backgrounds from Eritrea, Burkina Faso, Ghana, Rwanda, Tunisia, Haiti, and more.

While working on the anthology, Scego noticed the shared anger and exhaustion that AfroItalian women face due to systematic racism and discrimination. As such, in the introduction of Future, Scego describes the book as Italy’s contemporary J’accuse (signaling Émile Zola’s open letter to the president of the French Republic), as it “publicly denounces power and injustice.” More about the anthology can be found in a CUNYTV news segment, featuring interviews and readings by contributors Marie Moïse, Angelica Pesarini, and Camilla Hawthorne, hosted by the Calandra Italian American Institute of Queens College. The recording of Stories without Borders: A Conversation with Igiaba Scego, hosted by Casa Italiana of NYU, also focuses on Future and Scego’s other works like Beyond Babylon (trans. Aaron Robertson) and La linea del colore (The Color Line). (This response paraphrases Scego's answer to a similar question during Casa Italiana's virtual event, Stories without Borders).

What were the Fulbright projects that took you to Italy?

Barbara: I began studying Italian at Middlebury College, as a way of connecting with my cousins who were born and raised in the Veneto region. Italy was the only place my cousins had ever lived. Yet, because of their Blackness, they were always treated as outsiders. Learning the language helped me dive deeper into their experiences.

Studying in Italy my junior year sparked new questions about Blackness and sharpened my attention to how transnational contexts inflect the experience of Blackness. In Florence, I met and connected with many young people who, like my cousins, existed between Italian and Outsider – never quite considered Italian because of their Blackness. Meeting them pushed me to begin questioning what Blackness means across geographies and relationships.

So I returned to Italy in 2016 as a Fulbright Researcher to examine the complex interplay of education, citizenship, and identity for first and second-generation immigrant youth. I explored how school teachers create teaching practices that are responsive to these youths’ cultural and linguistic assets. I observed that, despite best intentions, teachers' relationships with Black students often reproduced antagonistic dynamics that led to those students, more than any other racialized group, being labeled as badly behaved or academically deficient. I joined various discussions held by Black Italians. I listened as they unpacked the reality of concurrently embodying Blackness and Italianness in a culture that perceives this duality as incompatible, an “irreconcilable paradox” as framed by Italian scholar Angelica Pesarini.

Candice: At Mount Holyoke College, I enrolled in Italian language courses to understand political commentaries about black communities during the immigration crisis. Through my majors Anthropology and Italian, I broadened my knowledge of analyzing culture and positionality with an intersectional approach to inform my research projects about the politics of Blackness, entrepreneurship, and institutions in Italy. I went to Italy for the first time as a year-long study abroad student in Bologna. My senior thesis analyzed my ethnographic research in that city and argued that Italian immigration laws negatively impact employment prospects for West African merchantmen, regardless of their legal status. Those laws also marginalize and racialize their bodies through biopolitics and biopower. I remained curious about the experiences of businesswomen of African descent and decided to apply for a Fulbright.

As a Fulbright Student Researcher in 2016-17, I researched how Italy’s racial and political history impacts the reception and promotion of businesses owned by African women and descendants in northern Italy. The women I spoke with had businesses in the hospitality, beauty, and e-commerce industries. They either moved to Italy as adults and had been living in the nation for years, or they were born and/or raised there as children and have been there their whole lives. They did not describe themselves as outsiders, even though the nation continues to view and treat them through immigration and exclusive citizenship laws shaped by the nation's colonial past. However, national organizations and political commentators see them as people who will save the country from a slow economy. This is usually juxtaposed with bodies that are considered illegitimate or a threat to the nation, often Black and Brown people of migratory backgrounds who do precarious labor to feed and sustain the needs of the population. I admire how these women challenge the boundaries of entrepreneurship and cultural production in Italy, considering the racist and neoliberal anxieties that impact their projects’ creation and perception.

Like Barbara, I also spoke with activists and changemakers about racial politics and notions of privilege. I was curious about the similarities between my experiences as an African American woman and those of Black Italians and the differences and ways that I may benefit from certain situations due to my Americanness. Tina Campt coined the concept of "intercultural address,” or how we see the commonalities and similarities between African American and Black European experiences through references to the hegemonic black American cultural capital across the globe. This notion significantly impacted my research and the articles I wrote during my Fulbright and currently shapes how I approach translation and promoting AfroItalian women’s voices.

Candice, you talked about doing a review of Future for The Dreaming Machine and mentioned that Pina, the editor, gave you the idea to translate one of its texts-- is that what made you think of doing the entire anthology?

Candice: As we spoke about writing a review in English for the book, Pina also gave me the idea to translate one of its stories. I thought it was a great idea to accompany the review.

I don’t remember the exact moment I decided to translate the anthology, but I do remember planning to do it as we got closer to the event at the Calandra Italian American Institute in February. I shared the idea with Marie Moïse, Angelica Pesarini, and Camilla Hawthorne as we prepared for the live event. It came up during the conversation on the importance of Black translators translating the works of Black authors. Barbara, who also has experience in translation and was also at the live event, shared her enthusiasm, and we decided to collaborate on it.

Barbara, what drew you to this project?

Barbara: I came to this project initially through Candice and then fully committed to it after reading the stories myself and hearing Marie Moïse, Angelica Pesarini, and Camilla Hawthorne, three contributors to the anthology speak at the Calandra Italian American Institute of the City University of New York.

In my various experiences living and studying in Italy, I was always acutely aware of my AfroItalian friends and colleagues’ liminal positionality. Because of my own identity as a Ghanaian American, and my background studying Black transnationalism, I empathize with aspects of their struggle. Nonetheless, I found that I did not always have the full scope of language to explain their specific positionality within the global Black diaspora to my non-Italian friends and colleagues. Translating Future is an opportunity to have these AfroItalian women speak for themselves on the world stage. In my role as a translator, my purpose is to create space for the anthology writers to grapple with and make meaning about their lives and have them be reachable to an English-speaking audience. These stories, which run the gamut of engaging Blackness in many forms is a relational process that I, as the translator, help bring forth.

Candice, you mentioned Tina Campt and her "concept of ‘intercultural address’ or the ways that we see the commonalities and similarities between African American and Black European experiences.” I'm wondering how that has affected your translation strategies in the anthology. And the opposite: are there examples of any differences you've struggled with in the translation?

Candice: Definitely. I think about power as an African American within the African diaspora, specifically amongst African descendants in Europe, and that discourses about race or systemic inequalities can be directly or indirectly about the United States. I try to reflect and act on how I may be contributing to perpetuating a hegemony of Americanness within the diaspora, so I think that one way to try and destabilize that is starting with myself.

As for strategies, Barbara has helped me with this as we work on the translation. One thing is using the word “folks” when perhaps a better word is “people.” I think “folk” is typical, maybe even expected, in American English vernacular, and the word “people” is clearer to all audiences.

Another example is translating racial slurs, which exist in the anthology. Misogynoir is not something that cannot be easily translated from one language to another, without considering the historical trauma those words come from. That’s something I am grappling with.

Like Barbara, I empathize with the struggles that AfroItalian women face. As I translate, I am learning a lot and hugely appreciate these women for sharing their stories. I hope that future readers will experience the same admiration that Barbara and I feel for them and their work.

How many authors are in the anthology?

Candice: Eleven authors contributed stories. The preface and postface were written by two academics, Dr. Camilla Hawthorne, from the U.S. and Prisca Augustoni, from Brazil. Igiaba Scego wrote the introduction.

We both appreciate that the anthology connects the experiences and struggles of AfroItalian women to others in the diaspora, such as Brazil. That type of trans-diasporic dialogue is essential and demonstrates that these histories and futures don't occur in a vacuum, or should only be compared to what occurs in the US.

Do you expect you'll be able to collaborate with the authors as you work on the translation?

Candice: Yes! Thankfully, Barbara and I already had connections with the contributors, either first degree or more. We plan to involve them in the process as we want to make sure that their words are reflected accurately and justly to English-speaking audiences.

Do you have any favorite texts among them?

Barbara: I can’t shake the stories by Marie Moïse or Angelica Pesarini.

Candice: I enjoyed all of them. In addition to the stories by Marie Moïse and Angelica Pesarini, "And Yet There Was Still a Smell of Rain" by Alesa Herero and "The Marathon Continues" by Addes Tesfamariam resonated with me.

#Candice Whitney#Barbara Ofosu-Somuah#Igiaba Scego#Marie Moïse#Camilla Hawthorne#Angelica Pesarini#Future. il domani narrato dalle voci di oggi#AfroItalians in translation

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Resisting Silence through Music: Asian Diaspora & Queer Identities

“I had supposed that I was practicing passive resistance to stereotyping, but it was so passive no one noticed I was resisting. To finally recognize our own invisibility is to finally be on the path toward visibility. Invisibility is not a natural state for anyone” (Mitsuye Yamada, 1979). In Invisibility is an Unnatural Disaster: Reflections of an Asian American Woman, Mitsuye Yamada urges Asian American women to strive toward visibility and resist the pressure to remain silent about their lived experiences. We wish to explore how Asian immigrants have navigated their multicultural and queer identities through music. In the United States and other Western countries, musicians with Asian ethnicities and heritage are often “othered,” with the label of “perpetual foreigner” imposed on their image, even if they have lived in the United States their entire lives. Here are some examples of musicians in the Asian diaspora who use their voices and music to affirm their Asian and queer identities, however they wish to define it.

youtube

1. Ruby Ibarra

Ruby Ibarra is a Filipina-American rapper who immigrated with her family from Tacloban City, Philippines to San Lorenzo, California. Living in the Bay area where hip-hop was a formative element of her childhood and adolescent years, Ibarra raps in Tagalog (Filipino language) and English. Through music she speaks about growing up with the colonial mentality of whitewashing, growing up as an immigrant family assimilating to US culture, and reclaiming pride as a filipina. She has said that she does not attempt to represent or define the immigrant experience for every individual, but that “[she] hopes people find moments in these songs where they feel represented.” As a non-black POC whose music largely focuses on the genre of rap music, there is definitely room to argue the nuances of using black culture for her music. It seems like Ibarra has taken steps to address this issue—on her social media platforms like instagram, she often gives tribute/credit to the black community: “I recognize my privileges as a non-black POC, and the beautiful culture and genre of music I’ve been able to participate in that was created by the black community.” (instagram post from February 1, 2018). She also takes action as an ally to use her platform in speaking out against police brutality: “Police (and media) typically justify the shootings by saying they were armed-- does being black cancel the right to bear arms? ...We need a system that doesn’t target a group of people. We need a system that doesn’t kill a group of people...The long history of system racism has led to mistrust and fear of law enforcement.” (instagram post from September 21, 2016).

Listen to her album Circa91. I recommend “Brown Out,” “Someday,” and “Us.”

youtube

2. Rina Sawayama

Rina Sawayama is a Japanese-British R&B pop musician. She was born in Niigata, Japan and immigrated to London, England with her family when she was 5 years old. In a 2018 Broadly interview, Zing Tsjeng describes Sawayama’s character as a “tangerine-haired, cyberpunk-influenced musician slash model.” A central theme that Sawayama explores in her music is romance and alienation in the internet-obsessed society that we live in.

In “Cherry,” Sawayama takes the opportunity to publicly vocalize her pansexual identity. She describes the song as her most personal but political song, and has contemplated past moments of shame around her queerness. For Sawayama, “Cherry” is a love letter of affirmation for bi and pan people who don’t feel authentically queer when they’re heterosexual relationships <3 <3 <3

During her studies at Cambridge in England, Sawayama felt alienated, different, and undesirable in an environment where over 60 percent of its student population is white and British. Later in life, Sawayama has found communities and families as she has continued her journey as a musician. She has spoken about the many emerging queer Asian artists active in many different genres: “We’re so protective of our space, even who we decide to sign to, who we decide to release through, or who we decide to work with. It’s really important to us. Because as queer Asians, there’s not that many of us and we really want to get it right.” To Sawayama, it’s important to her that she’s representing queer Asians, rather than just ‘Asian’. She wants to queer the world with pop music.

youtube

3. Japanese Breakfast

Michelle Zauner is a Korean American musician who takes the name Japanese Breakfast for her musical project that emerged as a way for Zauner to navigate her grief and memory of her mother’s terminal illness and death. Through music Zauner has found healing as well as a way to reckon with her Korean American identity. In the New Yorker essay “Crying in H Mart,” Zauner speaks about the identity crisis of losing her mother, who is her last connection to her Korean heritage.

Growing up in Eugene, Oregan, a predominately white town, Zauner hated being half Korean. She could barely speak the language and didn’t have any Asian friends. There was nothing about herself that felt Korean, except when it came to food. She has written an essay called “real Life: Love, Loss, and Kimchi” about the comforting power of food as a device of healing through her mother’s struggle with cancer.

On the moniker “Japanese Breakfast”, Zauner wanted a name that combined elements of something iconically American (breakfast) with something “American people just associate with something exotic or foreign” (Japanese). People often assume she’s Japanese, and Zauner says that she can tell who that real fans are—they know she’s Korean. She likes that the moniker exposes those who assume she’s Japanese.

Listen to her albums Psychopomp and Soft Sounds from Another Planet for trips of nostalgia and longing and contemplation on life and death and love and grief around identity and family <3 <3

youtube

4. Hayley Kiyoko

Hayley Kiyoko is a Japanese-American singer, songwriter, actress and director who was born and raised in Los Angeles, California. She has shown interest in music as early as 5 to 6 years of age when she got her first drum kit and wrote her first song. It was also around this age that she knew that she liked girls.

Since she was young, Kiyoko has combated the loneliness that comes with being a queer asian in society. She worked as an actress during her childhood, exposing her to discrimination due to her biracial physical appearance. Several rejections due to her appearance was enough to plant the seeds of doubt about whether she was enough. In addition, she kept her sexual orientation to herself in fear of being ostracized even further—only coming out to her parents in sixth grade. Unfortunately, her parents refused to acknowledge this confession, stating that it was just a phase.

She continued to keep her sexual orientation a secret which isolated her even further from her friends. She found it depressing to watch girls that I liked flirt with guys, so she stayed at home during her free time. Later on, she had her heart broken by her best friend which devastated her for a period of time. The constant rejection that Kiyoko had received until then prevented her from being comfortable with who she was, putting her in a state of perpetual fear.

In order to appeal to more of an audience, her songwriters wanted her to sing about topics that she personally connected to. As a result, she came out to her songwriters which inspired “Girls Like Girls,” a song that referenced her experience as a lesbian. Also, in putting out music videos that actually show the narrative that she sings about, she fights the heterosexual narrative that restricts the LGTBQ community in today’s society. Using her music as vehicle of representation, she unites a group of isolated individuals, earning her the nickname “Lesbian Jesus.”

By confronting her past fears and illustrating them in a form with which she loves and performs, she becomes the idol that she never had.

0 notes