#The Life of Oharu

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Kenji Mizoguchi

- The Life of Oharu

1952

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

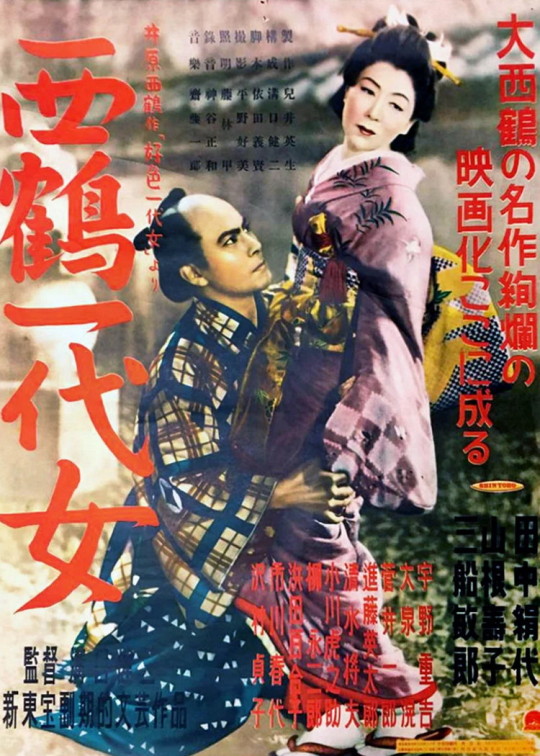

西鶴一代女 / The Life of Oharu Kenji Mizoguchi. 1952

Palace 541 Nijojocho, Nakagyo Ward, Kyoto, 604-8301, Japan See in map

See in imdb

#kenji mizoguchi#西鶴一代女#the life of oharu#kinuyo tanaka#movie#cinema#film#location#google maps#street view#japan#temple#nijo castle#kyoto#1952

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Life of Oharu (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1952)

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kenji Mizoguchi’s “西鶴一代女” (The Life of Oharu) April 17, 1952.

#Kenji Mizoguchi#西鶴一代女#The Life of Oharu#1952#Fifties#Foreign#🇯🇵#Drama#Tragedy#Kinuyo Tanaka#Toshiro Mifune#3/5

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saikaku ichidai onna, Kenji Mizoguchi, 1952

0 notes

Text

tagged by @peachpulpeuse

Favourite colour: dark blue

Last song: "Merry We Roll Along" has been in my head incessantly

Currently reading: I tried to start both Victoria Goddard's Hands of the Emperor and Tiffany McDaniel's On the Savage Side and it turns out that I hate them both! So I am doing a Prydain Chronicles reread and vacillating about whether to try and finish either or just give up and return them to the library

Currently watching: the real answer is the LotR extended edition special features. I have Kenji Mizoguchi's The Life of Oharu out from the library so hopefully I'll watch that in the next few days

Currently craving: a lot of rest. also samosas and chai, which is the best snack

Coffee or tea?: tea tea tea tea tea

A hobby you would like to try: mostly I just want enough time and energy to practice the hobbies I already have. But, given infinitely more time and energy, I would like to learn to weave

An AU you're working on/thought of: Penny Dreadful evil stepsisters AU! That one I would theoretically actually like to write. There's also a few variants on Dracula with spies that are floating around in my head but haven't taken form. Relatedly, @asimplecreature put "The Americans in Attolia" in my head and I have no idea what the hell to do with it but now it's stuck there. She gets credit for that one though.

tagging probably too many people because I am tired and doing this somewhat at random: @mysikrolik, @awildwickedslip, @tomato-greens, @twitterpatedly-yrs, @kareenvorbarra, @child-of-hurin, @winged-cries, @alder-knight, @measureformeasure

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

forgive me father, for i decided to rate mifune roles based on their husband-material qualities:

Eijima (from Snow Trail, 1947): would spit on the floor, gross, 4/10

Matsunaga (from Drunken Angel, 1948): homosexual??, 7/10

dr. Kyoji Fujisaki (from The Quiet Duel, 1949): don't care about his remorse and drama, get better soon, 7/10

detective Murakami (from Stray Dog, 1949): i love him, 9/10

Nagasawa (from Conduct Report on Professor Ishinaka, 1950): listen if he can tolerate that obnoxious laugh he's a saint, 10/10

Ichirō Aoye (from Scandal, 1950): 8/10

dr. Takeshi Ema (from Wedding Ring, 1950): 10/10

Tajōmaru (from Rashomon, 1950): 4/10

Denkichi Akama (from The Idiot, 1951): his first marriage didn't end well, 3/10

Miyamoto Musashi (from Sasaki Kojiro, 1951): too little material to rate, ?/10

Yonetaro Katayama (from Life of a Horse Trader, 1951): bad husband, 3.5/10

Chiyokichi (from Foghorn, 1952): don't know where the rating comes from but 8.5/10

Katsunosuke (from Life of Oharu, 1952): would literally die for you (if you are Oharu), 11/10

Kurokawa (from Tokyo Sweetheart, 1952): malewife, 10/10

Hayakawa (from The Last Embrace, 1953): cursed, 8/10

Ippei Itachi (from Sunflower Girl, 1953): has the potential to become malewife too, 10/10

Kikuchiyo (from Seven Samurai, 1954): compelling, 7/10

Musashi Miyamoto (from the Samurai trilogy, 1954-1955-1956): married first to swordmanship plus a lot of drama, honestly too much work for a marriage, 5/10

Mitsuo Yano (from No Time for Tears, 1955): haven't seen this one but love the vibes, 6/10

Shuntarō Ōhira (from Settlement of Love, 1956): get better friends first, 9/10

Kenkichi (from A Wife's Heart, 1956): 8.5/10

Washizu (from Throne of Blood, 1957): simp, will kill for you, 9.5/10

Sutekichi (from Lower Depths, 1957): 4.5/10

Matsugorō Tomishima (from The Rickshaw Man, 1958): PLEASE 8.5/10

general Rokurota Makabe (from The Hidden Fortress, 1958): would let you die for his clan but let's be honest those arms are worth the risk, 4.5/10

Heihachiro Komaki (from Samurai Saga, 1959): virtually 9/10

Nishi (from The Bad Sleep Well, 1960): we know how his first marriage went, 7.5/10

Sanjuro (from Yojimbo, 1961 and Sanjuro 1962): wouldn't settle down, probably bad husband (but i'd forgive him), 6/10

Gondo (from High and Low, 1963): boring job, 6/10

Akahige (from Red Beard, 1965), Shimada (from Sword of Doom, 1966), Jubei (from Red Sun, 1971): i think they would be married first to their job, 5/10

Isaburo Sasahara (from Samurai Rebellion, 1967): marriage to cover his old man gay affair with the in-movie Nakadai, ?/10

forgot many and haven't watched more but assume not going lower than 3/10 in the worst case scenario

#there's a twin list of mifune roles rated by how fuckables they are but i am not posting it because i like to think there's some dignity#left in me (although i ruined it all by admitting it here in the tags)#whateverrr#forgive me father#forgive me toshiro mifune#director's commentary

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

What criterions do you own?

Mirror, Before trilogy, The last picture show, Solaris, The life of oharu, A brighter summer day and In a lonely place

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kinuyo Tanaka and Isuzu Yamada in Flowing (Mikio Naruse, 1956)

Cast: Kinuyo Tanaka, Isuzu Yamada, Hideko Takamine, Mariko Okada, Haruko Sugimura, Sumiko Kurishima, Chieko Nakakita, Natsuko Kahara, Seiji Miyaguchi, Daisuke Kato. Screenplay: Toshiro Ide, Aya Koda, Sumie Tanaka, based on a novel by Koda. Cinematography: Masao Tamai. Production design: Satoru Chuko. Film editing: Eiji Ooi. Music: Ichiro Saito.

Having been a college English teacher and a print journalist, I know something about what it's like to be in a dying profession. So I have some empathy with the women in the geisha house in Mikio Naruse's Flowing. Their story is told largely from the point of view of Rita Yamanaka (Kinuyo Tanaka), whose name the owner of the house, Otsuta (Isuzu Yamada), finds too difficult to pronounce, so she calls her Oharu, a name that will have resonance for anyone who has seen Kenji Mizoguchi's 1952 masterpiece, The Life of Oharu. But unlike Mizoguchi's heroine, this Oharu is a simple woman in a profession that will probably never vanish: a maid. Her quiet ubiquity in the house enables her to see and hear things that heighten her mistress's financial struggles and the household's eventual doom. Equally valuable is the role of Katsuya (Hideko Takamine), Otsuta's daughter, who was trained as a geisha but doesn't want to be one. She regards her mother's profession as a commodification of self. Unfortunately, Katsuya has no marketable skills and is struggling to find her way in a male-dominated world. Naruse's film is a poignant and searching commentary not only on the disappearing way of the geisha but also on the role of women in a society trying to redefine the relationship between the sexes. Tanaka, Yamada, and Takamine are three of the greatest Japanese actors; it's a treat to see them working together, and they're beautifully supported by the rest of the cast.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Life of Oharu (It’s hard being hot)

Every guy you meet is either a total dirtbag, a criminal, or a dead man. Your parents sell you off at any chance they get. It’s rough being a lady in the Tokugawa era.

Oharu begins her life as a court lady who is exiled from Kyoto after being caught with a vassal of low status. I wasn’t that surprised at Oharu’s punishment, but it really shocked me when they straight up beheaded the vassal. I guess they were pretty serious about this stuff back in the day.

Next we follow the servants of a local lord on their search for a concubine. The lord’s demands are obviously absurd (8 inch feet??) and so its pretty comical to watch the servants frantically searching a huge row of women for the features requested (When one woman tells the older servant she’s 25, he replies “Oh, you’re just the leftovers!” LMAO) Like in Ugetsu, Mizoguchi uses comedy to enhance the social commentary of the film by putting us in the shoes of these men, to whom women are at best breeding stock, and at worst a punchline.

Oharu is selected as the concubine, but incurs the jealousy of the lord’s wife, who is already insecure as a result of some illness related balding. I think it’s kind of ironic that her hair condition would have been such a bad thing in an era where the highest men’s fashion is to push your hairline back to the age of dinosaurs, but that’s besides the point. Oharu exposes the wife with the help of a cat (for some reason it feels weird to see a cat in the 1600s) but is dismissed anyway, and goes back home to become a courtesan.

There she meets a counterfeiter, and is fired when some of her pride as a court lady emerges and she refuses to scrounge on the floor for his (fake) money. This counterfeiter is a total caricature of greed, another part of the film’s social commentary.

Oharu finally meets a nice man, then he gets stabbed like 5 minutes later. Womp womp. It’s rough out here ladies.

Taken in by another family, she is eventually visited by her a servant of her former lord collecting debt. It’s another hilarious moment when he declares to Oharu “I won’t be seduced by a whore like you!” and then changes his mind when he sees her naked, wiping his forehead like a cartoon character.

The story comes full circle to the temple, and we see Oharu finally taken in by her son, who is now a lord. But of course things never go right for Oharu, and she ends up repenting for the rest of her days.

Oharu’s is let down by everyone and everything in her life. She is let down by the rigid rules of the imperial court, and she is let down by her parents when they sell her. She is let down by the lord whom she serves as concubine, and she is let down by the man who promises to buy her from servitude. She is let down by the nun who promises to take her in, and by the priest who offers to buy her as a prostitute. Finally, she is let down by her own son.

Patriarchal systems are able to survive because they present themselves as a sort of exchange, wherein a woman submits to to men in exchange for their protection and monetary support. This film shatters the illusion of that bargain, and exposes the degree to which men, even in a period in which their conduct was supposedly honorable, used women for very specific purposes and discarded them almost immediately.

Good movie though. Oharu deserved better :(

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Life of Oharu

Dang. That movie was one of the saddest movies I have ever watched. The atmosphere that Mizoguchi created of a lady in the 1600s who had fallen from grace, may be exaggerated a bit, but still holds applicable to how many of the women during that time were treated. Even his own sister, who we talked about the class before, was sold off by her father which I can only imagine the effect that had on him and the future works that he would create. It really puts into perspective the hardships that women had to face throughout their lives and how the patriarchal society functioned. From her father, to her “lovers”, and to the other men that she had to face, every part that brought her problems was because of men and how they viewed women as property, rather than human beings like they should.

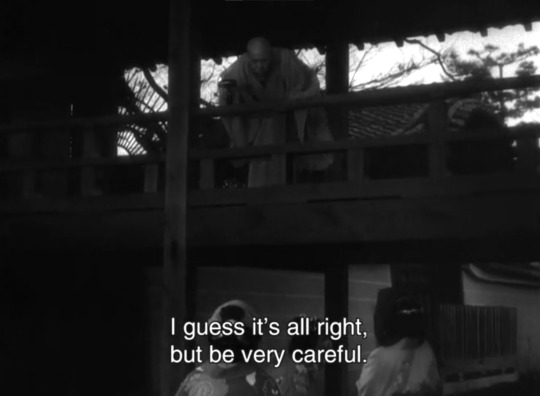

The titular character, Oharu, is introduced in the first frames of the movie, but it takes a bit for her to show her face, similar to how she would hide her face throughout the movie when meeting others for the first time. I think that Mizoguchi shot that long scene to put us into the shoes of how other people would see her and long to look at her face. Eventually, the beauty that she tries to hide turns into a beauty that she hides because of the path that she walks now as a nun. I thought that, despite everything that she went through, it was a respectable thing that she did. She was shunned by the nun at first because of the misunderstanding that was caused by Jihei, speaking of which, how terrible was that nun for not being able to forgive her and be the better person to still want to take care of a woman that has been tossed aside so many times. I thought that was so sad, to have Oharu in that position and turning to another lady who is supposed to take care of you, still casts you aside for what a man has done to you. It’s not even her fault, and she has to take the brunt of the punishment. But going back to the chronological story, one of the shots that I found interesting was the slow pan that revealed who I assumed was the priest of the temple, standing above the older ladies as a representation of the social status that men had back then.

The importance of money, not just in their society, but in the modern world as well. The shot where they all turned as the counterfeiter showed off the spoils to the people at the brothel was a really good shot. When they all turned around, it was pretty funny to me

More subtlety in the statues as the women are still below them, but also in the shot of Oharu and the other men looking down at her. It just reminds the audience of the lowly status that women had before.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kenji Mizoguchi

- The Life of Oharu

1952

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

The poor attempt at silencing the gun at the beginning probably set the tone for how I would feel throughout this whole film, lmao.

I also like, couldn't take anyone seriously when they walked hunched over and like they were seconds from either puking or peeing themselves. Genuinely "mom i frowed up" the whole film. Why.

One thing that did strike me from the beginning that I liked is that our man Nishi is just straight up a shell of a person. He has no life behind his eyes, no movement to his body. He's quiet and still. Guarded both by the way he physically holds himself as well as the near ever-present sunglasses he wears. It doesn't give me the stereotypical "I'm a tough guy cop" vibe. More of a sad, sullen and void of a human type of energy. Dude is entirely disassociated from life. Considering the shit he's had to deal with, it makes sense. He's like if Nanami was old and not hot.

While I do like the choice of mostly orchestral music because it tends to add a lot more of the typical despair tone that I feel like this movie carries throughout, I also can't give it too much credit. Maybe I'm burned out, but I've heard better orchestral OSTs. I will also give it credit that it knew when to kick up and when to fade out and leave no background music. More modern movies tend to have music constantly telling us how we're supposed to feel. It is interesting to see this juxtaposition of these scenes with really heartfelt/heart-wrenching orchestral elevator music where Nishi is supposedly Feeling Emotions compared to the silence or loud bursts of noise during violence. Likely its a commentary of the emptiness violence has to offer--because it appears much of (if not Nishi's whole life) is filled with violence of a sort (cancer is a form of violence) and why he, himself, is empty.

So much of this film is just standing around with quick cuts to abrupt violence before going back to the silence. Intentional, yes, but used so repeatedly throughout that I had the same issue I had with Oharu--dried up my give-a-shit well about a quarter of the way through. By the middle of the film baby I was in a drought worse than California.

I liked the non-linear storytelling. I do think that was done well, I just don't care for the story. It's also interesting that such a lifeless character gave art supplies to the dude who got paralyzed as a way to like, help him come back to and express himself. That felt oddly humanist. Maybe there's a soul in that detached body somewhere. Or maybe that was his way of like trying to kickstart himself into becoming a real boy again. It also felt like each painting foreshadowed what was about to happen in said scene--at least the one's they put more emphasis on.

One scene I think is particularly rude as hell is when she's watering the picked flowers and Mr. Buzzkill over here is saying its no use watering dead flowers like she herself isn't the physical manifestation of plucked wildflowers that are dead or dying. She still deserves to be watered, you prick.

Blood doesn't do that.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cruel Story of Youth / Naked Youth

Man, when we started watching this movie I came into it expecting the seriousness and intensity that we saw in Life of Oharu, but this film was something else. In this film the two young people, who are most likely supposed to be a larger representation of youths during that time, are wildly following passion and pleasure as the only truths of their existence. Nothing else is important to them, whether it be rules and regulations, legal matters, other family ties / relationship ties etc. We can see this clearly dictated in their actions when the main female character (Makoto) ignores the wishes of her family and lives with her boyfriend. We see it when Makoto lies to the police officers for a shorter sentence and then immediately wants to continue committing the crimes that got her put there in the first place. We see it in the guy when he ignores the older woman he is sleeping with for our main female character. When the main guy (Kiyoshi) drives the motorcycle, ignoring the effects that it may have for the person who he borrowed it from.

By driving this bike into the ocean he completely ruins it, and as a result they end up killing him for it. It creates this kind of dialogue indicating that despite their care free attitudes, that life has consequences and ignoring them will only end in harsher consequences. This happens with Makoto too when she gets a ride with another old man, willing ignorant of her own safety (I think she might have been trying the scheme again, but I can't remember exactly). This ends up with the same result that she was aiming for with every single shakedown they had attempted before; however, this time she wasn't ready for it, and when she tried to escape it killed her. This reinforces the idea that "choices have consequences" and that blindly adopting this generally western idea of 'following one's passion and damning the consequences' doesn't turn out well.

One thing that might have drawn audiences to this movie is its usage of color, but more realistically how B-rated it seems. There are many scenes that are comical in how bad or odd they feel. There is a scene where Kiyoshi puts an apple on the neck of Makoto (who just finished aborting her child), and then has an entire scene to himself just eating this apple. I'm still a bit lost to the message behind the scene, but the director chooses to film Kiyoshi eating nearly the entirety of the apple start to finish. Personally, I feel like whatever the message he was trying to send, he could have done that with an 8 second scene of him eating the apple rather than the near minute we get in the final production. The scene's with both of their deaths feel a bit B-rated as well. I am aware that this film was made in 1960; however, the way in which Makoto died just felt so unrealistic. She jumps out of a car and somehow catches her foot in the door and scrapes her face across the ground, but if you were really jumping out of a car is it even possible to get your foot stuck in the door like that?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

My best first-watches of March 2024

War and Peace [Война и мир] (1966-67) - Sergey Bondarchuk Fail Safe (1964) - Sidney Lumet The Browning Version (1951) - Anthony Asquith The Strategy of the Snail [La estrategia del caracol] (1993) - Sergio Cabrera Targets (1968) - Peter Bogdanovich The Earrings of Madame de… [Madame de...] (1953) - Max Ophüls The Celebration [Festen] (1998) - Thomas Vinterberg Poor Things (2023) - Yorgos Lanthimos Othello (1951) - Orson Welles The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice [お茶漬の味] (1952) - Yasujirō Ozu Funny Games (1997) - Michael Haneke Barton Fink (1991) - Joel & Ethan Coen The Night of the Iguana (1964) - John Huston Another Round [Druk] (2020) - Thomas Vinterberg Rope (1948) - Alfred Hitchcock The Prestige (2006) - Christopher Nolan That Most Important Thing: Love [L'important c'est d'aimer] (1975) - Andrzej Żuławski Panic [Panique] (1946) - Julien Duvivier The Holdovers (2023) - Alexander Payne The Life of Oharu [西鶴一代女] (1952) - Kenji Mizoguchi

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Life of Oharu by Kenji Mizoguchi

The film "Life of Oharu," directed by Kenji Mizoguchi, portrays the tumultuous life of a beautiful woman named Oharu.

The film portrays the societal roles of men and women during the Edo era. Regardless of a man's class or position, women were consistently viewed as possessions of men and were never regarded as equals. In such a world, Oharu, due to her exceptional beauty, finds herself manipulated by various men and repeatedly plunged into unfortunate circumstances. She lacks freedom in both love and work, with her downward spiral in life dictated entirely by the whims of men. Though fleeting moments of happiness do occur, they are often short-lived due to factors such as social status disparity or her past. It was hard to continue to watch Oharu, who stubbornly and strongly lives her life, not being rewarded while feeling the sorrow of living in a fate that repeatedly pushes her to the bottom of misfortune. Living as a woman during that era seemed incredibly challenging, and it made me unintentionally feel the joy of being able to live in the modern world. It is frightening to contemplate how a single misstep in choice due to a simple desire to live with a loved one could lead to such prolonged unhappiness.

While the film carries a profoundly tragic narrative, there are moments that elicit smiles, such as the scene where senior retainers search for a woman who meets the meticulous criteria of their lord, or when Oharu, likened to a bakeneko, mimics feline behavior. Also, scenes like the silhouette of a cat taking hair and where the face of one of the Five Hundred Rakan statues overlaps with that of Katsunosuke were particularly striking. The scene in which the man scatters money and revels extravagantly in a pleasure district where Oharu works recalled me the imagery of No-Face from "Spirited Away" dispensing gold.

The film predominantly employs long shots, allowing for seamless transitions between scenes as characters move from one location to another with the camera, maintaining continuity and enhancing realism, thereby immersing the audience in the unfolding narrative. It was as if I were watching a stage performance. There were many scenes, such as shots from under bridges and characters moving across rooms, that would not have worked unless everything was carefully calculated the meticulous coordination of character positions, camera movement, and set layout. This meticulous attention to detail facilitated a palpable sense of movement and flow, resulting in an engaging viewing experience. The structure of the story, such as the connection of the first and last scenes with flashbacks bridging, the fact that at the end of the story, Oharu takes the position of the woman who plays the shamisen midway through the story, and the out-of-focus camera direction to show Oharu's dizziness, were also good. I am amazed that they were able to create something this good at that time.

Moreover, the performances of the actors were amazing. Despite the few close-ups, their movements and expressions effectively conveyed the situations and emotions. Particularly noteworthy was the portrayal of Oharu by Kinuyo Tanaka, whose acting prowess was truly captivating. Her performance adeptly reflected Oharu's age, social status, position, and emotional state at each moment through her mannerisms, speech, voice, and expressions, and she skillfully depicted the tragic feelings of Oharu as she descended into old age, portraying her despair through facial expressions and demeanor with remarkable precision.

This film is a collaborative artistic creation of the director, cinematographer, cast, and crew, encapsulating the world of the Edo period with its cityscapes, props, traditional musical performances, puppetry, costumes, dances, hairstyles, makeup, and more. However, I do not think I have ever seen a film in which the protagonist is not rewarded until the end, with such a string of misfortunes. I can't think of any other film that leaves me with such a feeling of emptiness after watching it, even though there are no major incidents or deaths of characters that make me feel emotionally involved in the film.

3 notes

·

View notes