#The Last Temptation of Christ is one of my top ten films so I do love Marty

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Martin Scorcese is about to make another movie about Christ and hasnt cast Jesus yet. All I can say is, Marty, do it for the memes!

#timothee chalamet#dune part two#martin scorcese#dune#paul atreides#christ#jesus christ#timothée chalamet#btw#The Last Temptation of Christ is one of my top ten films so I do love Marty#Andrew Garfield#is clearly the right choice#clearly anything remotely spiritual should always be played by Andrew Garfield#have you heard the man talk? he feeeeels life on another level

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Magdalene by FKA Twigs, a review.

youtube

I’ve been learning some shit from women from as long as I’ve been alive. Always some other shit that I never asked for but I got told it. I used to treat them things they said as laws as a child, but I never saw them in a book, so then I stopped believing them. They were always hushed laws though, laws told with squinted eyes and italicized whispers, laws told when no one else was around.

I mean, now of course men make the real laws that we know and live by. Well come on now, we write them on parchment, and display them on lights, we code them into computers, inscribe them on coins and stone. But these women…man women tell you some other shit, like glue shit, in low, muttered tones in the quiet part of the house. Like advice on… well not how the world works, but how to deal with the world when it works against you, and how to make it work for you. But you see, I’ve come to believe that the fairer sex tells you different laws than the vaunted laws and advice of our fathers because they all around see the world differently than men do. They may, in fact, have been harbouring different goals than us all along.

I mean for christssakes us men have our hero’s journey as clear as day, writ large and indelible across history books and entertainment. You could take that Joseph Campbell mono-myth theory and see it expressed in Arthurian swash-buckle, the middle earth ring-slaying of Tolkien, or in the recently concluded tri-trilogy of Star Wars galactic clashes. We’re in the empire business, as Breaking Bad’s Walter White infamously said. But still, the question always lingered to me: what is the heroine’s journey? Is it really just a lady in a knight’s armour? Or some tough-as-nails spy for some interloping government’s intelligence agency, delivering kidney kicks in a designer pencil skirt?

Well, I’ve come to believe that the heroine’s journey is navigating the waves of history we imperial and trans-national men make from our railroads and pipelines, our satellites and wars, them at once preserving a culture and sparking a path and creating a bond between cultures in order for them and their (il)legitimate brood to survive. That old chestnut about how behind every successful man is a woman always unnerved me by its easy adoption. I kept thinking ‘bout that woman. I kept thinking, what the fuck was she thinking?

You see women’s heroes, they ain’t as clear as day to me. They don’t kill the dragon, they don’t save the townspeople, they don’t shoot the Sherriff, or the deputy, or anyone most times. When I ask people in public at my job what super power they would like, most men go for strength, flight, and regenerative abilities (my pick). Most women went with mind reading and flight. In late night conversations though, with the moonlight coming through the white blinds and resting soft on us like so, I sometimes manage to hear that women’s heroes heal and clean the sick of the nation, in sneakers with heels as round as a childhood eraser; they feed a family with one fish and five slices of wonder bread; they would run gambling spots in the back of their house, putting the needle back on the Commodores record and patrolling the perimeter of the smoked-out room with a black .45 nested by their love handles; they climb up flag poles and speak out loud in public for the disposed and teach children those unwritten, floating laws while cloistered in the quiet part of the house.

Although their heroines are sometimes from the top strata of society –a Pharaoh here, an Eleanor Roosevelt there, an Oprah over there—they also name a healthy mix of radicals and weirdos with modest music success, people like Susan B. Anthony, Frida Kahlo, Virginia Woolf, or Nikki Giovanni, I mean did Nina Simone or Janis Joplin even crack the Billboard top ten? Yet there they are, up on the walls of a thousand college dorms across the country. So even though I couldn’t’ve foreseen it, it makes sense that of all the ultra-natural creatures, of all the great conquering kings and divining prophets of the Holy Bible, Mary Magdalene ends up the spirit animal for the album of the year for 2019.

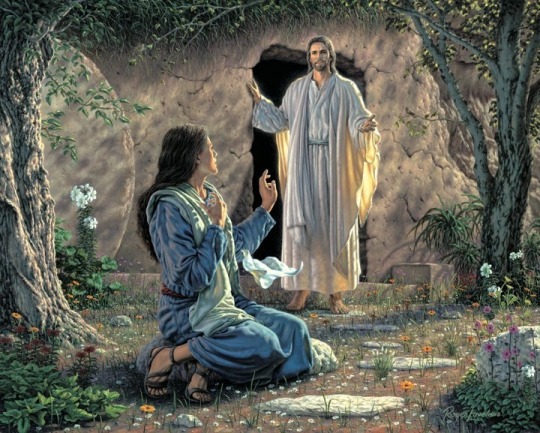

Mary Magdalene was a follower of Jewish Rabbi Jesus during the first century, according to the four Gospels of the New Testament of the Bible, a figure who was present for his miracles, his crucifixion and was the first to witness him after his resurrection. From Pope Gregory I in the sixth century to Pope Paul VI in 1969, the Roman Catholic Church portrayed her as a prostitute, a sinful woman who had seven demons exorcised from her. Medieval legends of the thirteenth century describe her as a wealthy woman who went to France and performed miracles, while in the apocryphal text The Gospel of Mary, translated in the mid-twentieth century, she is Jesus’ most trusted disciple who teaches the other apostles of the savior’s private philosophies.

Due to this range of description from varying figures in society, she gets portrayed in differing ways, by all types of women, each finding a part of Magdalene to explain themselves through. Barbra Hershey, in the first half of Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) plays her as a firm and mysterious guide, a rebellious older cousin almost, while Yvonne Elliman, in Norman Jewison’s 1973 film adaptation of Lloyd Weber’s Jesus Christ Superstar is lovelorn and tender throughout, a proud witness of the Word being written for the first time. In “Mary Magdalene,” FKA Twigs, the Birmingham UK alt-soul singer, describes the woman as a “creature of desire”, and she talks about possessing a “sacred geometry,” and later on in the song she tells us of “a nurturing breath that could stroke you/ divine confidence, a woman’s war, unoccupied history.” Her vocals that sound glassy and spectral in the solemn echoes of the acapella first third, co-produced by Benny Blanco, turn sensual and emotive when the blocky groove kicks in. That groove comes into its own on the Nicolas Jaar produced back third, and when this all is adorned with plucked arpeggios it sounds like an autumnal sister to the wintry prowl of Bjork’s “Hidden Place” from her still excellent Vespertine (2001).

This blending of the affairs of the body and of Christian theology is found in the moody “Holy Terrain�� as well. While it is too hermetic and subdued to have been an effective single, it still works really well as an album track. In this arena, Future is not the hopped up king of the club, but a vulnerable star, with shaded eyes and a heart wrapped up in love and chemicals, sending his girl to church with drug money to pay tithes. Over a domesticated trap beat he shows a vulnerable bond that can exist, wailing his sins and his devotion like a tipsy boyfriend does in the middle of a party, or perhaps like John the Baptist did, during one of his frenzied sermons, possessed and wailing “if you pray for me I know you play for keeps, calling my name, calling my name/ taking the feeling of promethazine away.”

Magdalene, the singer’s sophomore release, takes the mysterious power and resonance of this biblical anti-heroine, and involves its songs with her, these emotional, multi-textured songs about fame, pain and the break up with movie star boyfriend Robert Pattinson. With “Sad Day,” Twigs sings with a delicate yet emotional yearning, imbued with a Kate Bush domesticity. The synth pads are a pulsing murmur, and the vocal samples are chopped and rendered into lonely, twisting figures. The drums crash in only every once in a while, just enough to reset the tension and carve out an electronic groove, while the rest of the thing is an exercise in mood and restraint, the production by twigs, Jaar and Blanco, along with Cashmere Cat and Skrillex, leaves her laments cosseted in a floating sound, distant yet dense and tumultuous, the way approaching storm clouds can feel. Meanwhile “Thousand Eyes” is a choir of Twigs, some voices cluttered and glittering, some others echoed and filled with dolour. “If you walk away it starts a thousand eyes,” she sings, the line starting off as pleading advice and by the close of the song ending up a warning in reverb, the vintage synths and updated DAWs used to create these sparse, aural haunts where the choral of shes and the digital ghosts of memory can echo around her whispered confessional.

In many of these divorce albums, the other party’s role in the conflict is laid bare in scathing terms: the wife that “didn’t have to use the son of mine, to keep me in line” from Marvin Gaye’s Here My Dear from 1979; the players who “only love you when they’re playin’” as Stevie Nicks sang on Fleetwood Macs Rumours (1977); or as Beyonce’s Lemonade (2017) charges, the husband that needs “to call Becky with the good hair.” At first though, Twigs is diplomatic, like in “Home with me,” where she lays the conflict on both sides here, expressing the rigours of fame, the miscommunication –accidental or intentional –that fracture relationships, and the violent, tenuous silence of a house where one of the members is in some another country doing god knows what, physically or mentally. “I didn’t know you were lonely, if you’d just told me I’d be home with you,” she sings in the chorus over a lonely piano, while the verse sections have the piano chords flanked by blocks of glitch, and littered with flitched-off synths. Then, the last chorus swirls the words again, along with the strings and horns and everything into a rising crescendo of regret.

Later in the album however, her anger once smoldering is set alight, in the dramatic highlight “Fallen Alien.” Twigs sings with an increasing tension, as her agile voice morphs from confused, pouting girlfriend to towering lady of the manor, launching imprecations towards a past lover and perhaps fame itself. “I was waiting for you, on the outside, don’t tell me what you want ‘cuz I know you lie,” she sings, and, after the tension ratchets up becomes “when the lights are on, I know you, see you’re grey from all the lies you tell,” and then later on we have her sneering out loud “now hold me close, so tender, when you fall asleep I’ll kick you down.” All while pondering pianos drop like rain from an awning, tick-tocking mini-snares and skittering noises flit across the beat like summer insects, the kicks of which are like an insistent, inquisitive knocking at the door, and then there’s that sample, filtered into an incandescent flame, crackling an I FEEL THE LIGHTNING BLAST! all over the song like the arc of a Tesla coil. The song is a shocking rebuke, and it becomes apparent upon replays that the songs are sequenced to lead up to and away from it, the gravitational weight giving a shape and pace to the whole album. Because of this, the other songs on Magdalene have more tempered, subtle electronic hues and tones, as if the seductive future soul of 2013s “Water Me” from EP2, and the inventive, booming experimentation of “Glass & Patron” from 2015s M3LL1SSX, were pursed back and restrained until it was needed most, and this results in an album more accomplished, nuanced and focused than her impressive but inconsistent debut LP1 (reviewed here).

This technique of electronic restraint has shown up in the most recent albums by experimental pioneers, with the sparse, mournful tension of Radiohead’s A Moon Shaped Pool (2017), it’s cold, analog synths and digital embellishments cresting on the periphery of the song, and with Wilco’s Ode to Joy from last year, an album bereft of their lauded static and electric scrawl, mostly embossed in acoustic solitude and brittle, wintery guitar licks. Twigs and her co-producers take the same knack for the most part throughout the album, like with closer “Cellophane,” where the dramatic voice and piano are in the forefront, while effects crunch lightly in the background like static electricity in a stretched sweater, and elsewhere, as the synths of “Daybed” slowly intensify into a sparkling soundscape, as if manufacturing an awakening sunrise through a bedroom window. And it is this seamless melding of organic and electronic instruments, to express these wretched and fleeting emotions of heartbreak that makes this the album of the year.

It makes sense that an artist like FKA Twigs would be drawn to a figure like Mary Magdalene. Of the many Marys in the New Testament, she stuck out as palpably different, or rather, she depicted a differing part of womanhood than the other two. She wasn’t the chaste, life-giving mother of Jesus, or the dutiful Mary of Clopas. Instead, Magdalene was this mixture of sexuality and spirituality, one of those figures that managed to know men and women in equal measure, wrapped up with the blood as well as the flesh. Twigs also played with this enrapturing sexuality in her work, writhing around in bed begging some papi to pacify her and fuck her while she stared at the sun, then making you identify with the lamentations of video girls, and then telling you in two weeks you won’t even recognize who you were seeing before. There was something mysterious and layered to her millennial art-chick sexpot act though, layers that have begun to be revealed with this album.

We realise now, that what she was depicting all along was more like the sexual heat that lays underneath devotion, as opposed to fleeting, mayfly lust, and that she now understands the weight and half-life of love. That is, that beyond the sex and patron and fame there is a near sacred love we build between each other for a while in time, lasting as long as both hands can bear to hold it, and also that the death of a relationship still has the memory of the love created warm within it that then radiates off slow into the air. A love that then falls into our minds for safekeeping dark and unobstructed now, the way Jesus’ blood fell from his wound into Joseph of Arimathea’s grail held aloft.

“I never met a hero like me in a sci-fi,” FKA Twigs sings, an evocative line less so for the hegemonic patriarchy of the worldwide movie and comic book industry suggested by ‘the sci-fi’ here, and more for the ‘hero like me’ part, which suggests she had to make her hero origin story all up, without the scaffolding of centuries of relatable mythologies, presenting us with an avatar of millennial love, in all of its tortured luster. And you hear this type of love in her voice, no longer changed up and ran through a filter for Future Soul sophistication most times, but out in the open now, to express particular emotions, whether it’s in that swooping, falling ‘I’ in the heart-break closer “Cellophane,” or her assured realisation, later on “Home With Me” where she says “But I’d save a life if I thought it belonged to you/ Mary Magdalene would never let her loved ones down.”

youtube

It’s never about how to conquer with these women you see. In the end of all relationships it’s how they find their way out after us temporarily embarrassed conquerors are about to leave, jacket slung over shoulder, standing by the door. You squint your eyes back at her this time, and you listen this time, while she tells you, or tells the ground in front of you, what parts of love to let go of, and what parts are worth holding on to in this age of Satan, the parts that will help you become yourself. “I wonder if you think that I could never help you fly,” the song tells you then, one of those stinging admissions that only women come up with, and you wisely stay silent, and then the piano chords part, the synths subside. And for a while there as she looks at you, as the breathy sortilege in the song keeps going, it all sounds like something worth believing in again. And then, the words she says to you start to come across like laws.

#music#music review#rnb#rnb music#r&b#soul#future soul#future pop#alt soul#electronica#fka twigs#magdalene#mary magdalene#cellophane#Long Reads#sad day#hiro murai#new music

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Hard Work and Faith Lead to Success in Life.

Faith movies tend to get a bad rap. True, there have been the occasional big budget blockbuster exceptions such as The Passion of the Christ directed by Mel Gibson or the Noah directed by Darren Aronofsky. Then of course there is Cecil B DeMille’s famous “The Ten Commandments” with Charlton Heston and the less successful “Exodus: Gods and Kings” directed by Ridley Scott. Plus every two decades or so Martin Scorsese takes a shot at a Catholic-themed film like The Last Temptation of Christ or Silence.

However, today I am going to talk to you about the most religious movie you've ever seen — and didn't realize it. Frankly, it’s one of the best movies of all time.

Irwin Allen, a Hollywood Producer and Director, who became known as the “Master of Disaster” because of of two seminal movies he produced: 1972’s “The Poseidon Adventure" and 1974’s “The Towering Inferno.” I love them both.

The Poseidon Adventure (1972)

Because of the success of these movies, both of which became blockbusters, and because of the focus on the disaster spectacle of them, the true meaning of both are overlooked.

Today, I want to look at The Poseidon Adventure and what it has to say about religion, faith in oneself, and faith in God.

Let’s dive in.

In the beginning of the movie, we are introduced to all of our characters as the ship’s voyage is underway, and preparations are being made for New Year’s Eve, which is being celebrated that night in a gala in the ballroom onboard the ship. The cast contains some of the most familiar faces to audience in the 1970s (and today, among us cinephiles), with most of the cast having at one time or another been the top of his or her game in their respective arts: dance, theater, or movies. However, the main character we meet is clearly “Reverend Scott” played by Gene Hackman.

When people talk about roles that couldn't be played by anybody else, for me this is one that always comes to mind. In his first scene, Hackman’s “Reverend Scott” is in conversation with a fellow priest, the boat’s chaplain, played by Arthur O’Connell. Here we learn a little bit about Reverend Scott. We discover that he is being transferred to a parish deep in Africa. He actually says he had to look it up on a map. He is being sent to this parish because of his radical ideas about God, faith, and presumably the Catholic Church.

What's important is not the particular religion or the denomination, but rather that Reverend Scott is a character archetype: He is “A Religious Man.” “A Man of Faith.” More specifically, he is at the moment we meet him, a shepherd without a flock. We find Reverend Scott and Father John discussing God and faith in light of life-threatening circumstances. (A healthy bit of foreshadowing here). Reverend Scott is saying that if you're freezing to death you don't fall to your knees and pray to God. You get off your knees and you burn the furniture. You set fire to the building. Father John responds that those are pretty radical ideas. Scott’s reply is that they are radical, but “realistic.”

Realistic: Having or showing a sensible or practical idea about what can be achieved or expected.

Father John jokingly questions whether Scott is still a reverend. Reverend Scott has been stripped of most of his clerical powers (we realize he’s not wearing a frock and collar). However, he doesn’t view this as punishment but rather as “freedom…elbow room…freedom to find God in my own way.”

He’s mercurial. But what we do know so far is that his belief is that God wants you to take responsibility for your own life. He wants you to take action. Later, during his sermon, Reverend Scott tells the people, “Don’t pray to God to save you. Pray to that part of God within you. Have the guts to fight for yourself.” He then suggests that the New Years resolution they should all make is “to let God know they have the guts and the will to do it alone. To fight for those you love…Resolve to save your own life.” He tells them that if they do that, the part of God within them will be fighting with them all the way.

The movie is an exploration of this idea.

The movie continues, introducing us to the other characters. We are introduced to Ernest Borgnoine who plays “Mike Rogo,” a New York City cop with a backlog of dirtbags he’s still trying to put behind bars. Wait, no. That’s John McClane. We’ll get to him and Die Hard in other posts. The Poseidon Adventure’s “Mike Rogo,” is a veteran New York City Detective, who we get the sense is on his first vacation ever. He seems out of place—a literal fish out of water if you will. He is traveling with his wife “Linda,” who is sea sick. The ship, Poseidon, has been sailing through a storm and rough seas (a harbinger of things to come). Rogo seems a bit self-conscious about his wife, at the same time as he seems very protective of her. We come to find out this is because Linda, played by Stella Stevens, was a former hooker, and that she and Rogo met when he arrested her. Now, she’s his brassy, tough, take-no-guff wife, despite their shared self-conciosuness about her past. Even laid low by nauseau she’s the one person who can properly put Mike Rogo in his place. The reason is, these two are very much in love.

We also meet a young boy, “Robin” his sister, “Susan” as well as a quirky bachelor, “Mr. Martin,” played by Red Buttons who we first meet doing the funniest walk on film until Billy Crystal and Bruno Kirby went exercising in Central Park in “When Harry Met Sally.” We’ll come back to these characters later — when the world gets turned upside down.

The other characters we meet or an older couple named “Manny” and “Belle Rosen” played by Jack Albertson and the incomprable Shelly Winters. They are an older Jewish couple who are on their way to Israel to see their two-year old grandson who they've never met before.

We are also introduced to the Captain played by the great Leslie Nielsen. A actor who reinvented himself and had three successful careers in Hollywood, which is three more than most. As the Captain of Poseidon we get the sense that he is a man who loves the ocean, but has been out to sea for too long, has grown old at the helm, and that this islikely his last cruise before he gets dry docked. Which might explain why he is running three days behind schedule, (perhaps an attempt to prolong his final voyage?) Whatever the reason, there is pressure on him to go faster.

Eighteen minutes in, and the New Year's Eve party begins in the ballroom. We catch some snippets of conversation at the different tables. This gives us a chance to meet some of the ships’ officers among them the “Purser,” who says only half-kidding that he is the real head of the ship, referring to himself as the Manager of a hotel that floats. He is another figure of authority. We again meet the boy, “Robin’s” (Eric Shea) as well as his older sister, “Susan” (Pamela Sue Martin), and Roddy McDowell’s kind-hearted, Irish bartender, “Acres.”

It's worth noting here that it's no accident that the movie is set on New Year's Eve. Of all the holidays that could be celebrated in this movie, one which marks a time of year when things are coming to an end and people are hoping for fresh starts and new beginnings. It serves as a perfect metaphorical holiday for the movies larger story. And all our secular celebrations, New Year's Eve is often tied in peoples minds to Christmas, which is of course a very holy day. In fact, there is a giant Christmas tree in the ballroom, which is going to be very crucial in a few moments.

Meanwhile, at the Captain’s table, Leslie Neilsen is speaking to his guests about Poseidon, the Greek god of the sea, from whom the ship gets its name. The Captain makes an ominously prescient remark about Poseidon’s “ill-temper.” It is worth noting that Reverend Scott is at the table. So we have this Man of God sitting across from the Captain of a ship, who is worshipful of a different god. The Captain meanwhile gets a call that he is needed on the bridge and excuses himself.

The conversation and celebration continues with characters taking to the dance floor for a scene culminating countdown to the new year. (Which serves as a countdown to the disaster that is about to befall them all).

Meanwhile, we cut back to the Captain on the bridge, where he is given a report of an undersea earthquake which is triggered a tsunami. This is important. Because what is an earthquake, but an act of God. As is the wave that strikes them. It is described by the Lookout as bigger than anything he’s ever seen — in other words, it defies any expectation.

In a great cinematic moment, the celebratory cheers of the characters in the ballroom are drowned out by the sound out the ship’s clakhorn signalling the “mayday” the captain has just ordered. They are moments away from an unexpected tidal wave that is about to turn their world literally upside down.

The Ballroom Floods

This is usually how Acts of God tend to go.

In one of the classic scenes that made Irwin Allen the “Master of Disaster” the ship is struck by the wave, and capsizes—

The characters in the ballroom go flying every which way. So does everything else. Furniture, plates, glasses, even the grand piano, all of it tossed and tumbled, with the final shot of a man who falls from a table on what is now the ceiling, plummeting and landing (somewhat Christ-like) on to the glass skylight which shatters. Another explosion rocks the ship, and the lights go out.

Blackness.

When we fade back up, our characters find themselves in a new world. Upside down. In darkness. Underwater. It is a world of chaos.

Linda’s first words are “Jesus Christ” and when we see Shelly Winters she is silently whispering, The Shema prayer, which is if not the holiest, then the most well known of the Jewish prayers, written in the Torah.

In other words, characters are in their own, acknowledging God. Not little “g” god, Poseidon, but the One God, in all his names. And they don’t say it lightly either. These are people who now understand what it means to fear God (fear as in awe, not terror. They’re too shocked to be terrified, but they are most certainly awed).

Reverend Scott meanwhile goes to help a dying man crushed under the debris. He watches helplessly as the man dies in his arms.

It’s a leap of faith.

Next, we hear the voice of the ship’s Purser — an authority figure — as he tries to get control of the situation. He tells people to stay calm, that help is on the way (he actually says it twice, the second time sounding more desperate than the first.)

Reverend Scott sees the boy “Robin” wandering around looking for his sister. He goes to help the boy, at which point we hear his sister’s voice from above. They look up and there is “Susan” crouched under a table which is bolted to the floor which is now the ceiling. She needs help getting down.

There’s only one way. She has to jump.

Reverend Scott gathers some of the survivors and a tablecloth and tells Susan to jump. Scared, Susan can’t bring herself to do it. Reverend Scott tells her to trust him, that they will catch her, and to jump!

It’s a leap of faith.

The faith is not in God (at this point) but in her fellow passengers. The moment of relief is cut short as the giant Christmas tree in the ballroom topples over almost killing some more passengers.

The ship’s Purser once again yells out for everyone to stay still and wait where they are. Hackman’s Reverend Scott on the other hand, is taking action, helping people. Which is why Roddy McDowall’s “Acres”the bartender, who it turns out is also trapped on the ceiling calls out to Reverend Scott and not the ship’s Purser. (Fittingly, like any good movie bartender, even during disaster, Acres remains behind the bar).

However, rather than get Acres down, Reverend Scott has a different idea. They're going to go up. Actually, it’s Red Bottom’s “Mr. Martin” who suggests going up, and the boy Robin who knows that the thinnest part of the hull where they are most likely to be rescued. Reverend Scott realizes they’re right and they need to go up.

Up.

Get it?

They’re going to go higher.

Why?

Well, ostensibly because they need to get to the bottom of the ship’s hull to get rescued, but also because they need to outrun the water that is shortly going to burst into the ballroom and drown everyone.

Does that sound like anything familiar? Biblical?

It’s the Flood.

Many cultures have a flood story from the Old Testament Bible story of Noah, or the Babylonian epic of Gilgamesh. Fittingly, so does The Poseidon Adventure, a movie about faith and God.

The Sea pours in. The Flood.

So, a small group (a flock) of passengers are joining Reverend Scott in attempting to go up through the ship to reach the bottom. Kind of like the metaphor of having to go through hell to get to heaven. The passengers have to go to the bottom — through hell, as we will see — in order to be saved.

The question becomes how to reach Acres. How to get up to where he is, tohigher ground? They need a ladder of some kind. They find it in the toppled over Christmas tree. And who does Reverend Scott choose to be the first one up the ladder? The boy Robyn. And a small child shall lead them (Isiah 11:18)

At this point the ships Purser (authority figure) speaks up and tells everyone on the ship not to listen to the Reverend. His choice of words is interesting here. The Purser says, "for God’s sake, what you're doing is suicide." It’s almost a religious invocation to get them to stop. But it lacks the conviction of faith and instead sounds desperate. The two men, the two authority figures in this case, The Reverend and The Purser (religious and societal, you might say) square off.

Do the passengers listen to the Purser and stay where they are and wait to be rescued? “Pray” as he suggests to the Reverend. Or do they join Hackman’s Reverend, who believes that “maybe by climbing out [of the pit] they’re in” can save them. The Reverend’s choice of words is as revealing as the Pursers. He says, "if you have any sense you'll come with us." In other words, the purser makes a religious appeal and the Reverend makes a common sense appeal. There's probably more to this, something like the idea that the way we know the right(eous) path is initially through our human intuition (common sense) and not merely by declaring we should all believe in God, or pray to God for help and expect to be saved. God wants us to get up and go.

The first chapter of the Abrahamic stories in the Torah (the Old Testament) is God telling Abraham to leave his father’s house, to get up and go. (Hebrew: Lech lacha).

Each of our characters makes their choice considers their choice. Mike Rogo and Linda are the polemics of that choice. Rogo, the cop wants to follow the rules, (Although we do know that if the reason is a good enough one he'll break the rules; after all he used his powers as a cop to arrest a woman who was a prostitute because he wanted to marry her and he needed to get her off the street). Linda, who has only recently begun to conform to polite society, calls Mike out for being a person who always follows the rules. Not surprisingly, she is the next one up the ladder after Robin, the young boy.

We find Manny and Belle Rosen, the old Jewish couple. Belle is giving Manny her necklace, which is a hai, the Jewish word for life. She tells Manny to take the necklace to their grandson in Israel. She's not going. She's going to stay and wait with the others. Why? Because, she thinks she is too fat to climb. Enter Reverend Scott. He tells Belle that she's coming with them. That she can't stay here.

Why not? she asks. It's a good question too. It’s is a realistic one. She isn’t in good enough shape to climb. Yet, it is Reverend Scott, the proponent of being realistic—but also a believer that every person has to try to fight for their life—who encourages her to climb. Pointing up, he tells her, “that way is life.” It's hard not to think that his invocation of the word “life”—the meaning of the symbol on her necklace that just moments ago she was giving to her husband having resigned herself to die—that gets her join Reverend Scott and the others.

This is a key moment in the movie. We are seeing Reverend Scott's beliefs in action. He is encouraging people to fight to save their lives. There is an element of faith under girding his pleading with people to come with him. Where is that faith found? For the moment, it’s in the fight for life.

So Reverend Scott and his group climb the tree and join Acres up top. Before they leave, Hackman’s Reverend finds his friend, Father John. He asks Father John what he thought of his sermon earlier. Father John tells Reverend Scott that he spoke only for the strong. Reverend Scott asks Father John to be strong and come with them. Father John says he can't. He has to stay with the people staying behind. Hackman doesn't understand. He asks Father John what his life will be for, if he stays? Father John, after looking over the desperate faces of the surviving passengers, tells Reverend Scott that he doesn't have any other choice. Father John knows that, as a man of God, he is meant to stay to bring comfort to the people who are about to meet their maker. This sacrifice is in an anathema to Reverend Scott.

Before he departs, Reverend Scott pleads with the survivors one last time to reconsider and come with him. He's answered by the Purser who shouts back they're staying and waiting to be rescued. For the first time Reverend Scott invokes God and begs the people to come with him. “For God’s sake.”

No one comes.

Reverend Scott ascends the Christmas tree (of life) alone. He makes one final appeal from up top (almost like a pulpit). Just before he leaves there's an explosion. The water floods the ballroom drowning everybody who decided to stay and wait for a rescue…that will never come. Terrified passengers attempt to climb the tree-ladder, but in their panic they end up toppling the Christmas tree and falling backward into the water to their death (Reverend Scott is almost pulled off from his perch by the frantic passengers). There's an incredible music cue at this moment as Hackman offers a final remorseful look at the drowning passengers. He leaves them to return his flock. He tells them the terrible news. Terrible news that at the same time signifies they made the right choice.

The rest of the movie will be a race against the rising waters of the sinking ship. In other words, they are literally trying to outrun the flood. Paradoxically, in this flood story, if the people want to live, they need to get off of a boat, instead of on one.

The group arrive at a burning hot door behind which is a raging fire. They are literally opening the doors to hell.

Reverend Scott leads the way, going first in order to find the way through. He finds the path and returns for his flock and leads them safely through. As they make their way the passengers are horrified at the sight of the dead bodies and frightened by the fires burning all around them. Ominous signs.

They make it through, but just barely. The waters burst in and threaten to drown them yet again. They escape. Barely. But to get to the next level they have to climb through an air duct. Once again, Shelly Winters is concerned she won’t fit. The group is having to face their fears in order to keep moving forward.

Nadia, the lounge singer, is claustrophobic and doesn’t want to go into the shaft. Mr Martin (Red Bottoms) has taken a protective shine to her, and is able to reassure her. Linda, decides she’s done being polite and won’t be going after Belle Rosen because she doesn’t want to get stuck behind “old fat ass” as she calls Shelley Winters.

This is good advice in a crisis. You focus on the small steps. You take it one rung at a time.

The flock reaches another shaft where there is yet another ladder to climb. The climb is slowed down by Nadia’s claustrophobia. The waters, ever rising, stay close on their heels. Everyone climbs up the shaft.

Unfortunately, an explosion rocks the boat and poor Acres (Roddy McDowall) loses his grip and falls. Mike Rogo goes after him, but it’s too late. He’s gone.

The water is getting higher. Rogo climbs up from the depths but gets stuck behind Mr. Martin and Nadia, who’s frozen with fear and won’t climb. Mr. Martin has to help her up…one rung at a time. He tells her not to think of anything but the next rung on the ladder. This is good advice in a crisis. You focus on the small steps. You take it one rung at a time.

“Who do you think you are? God himself? There was an explosion, and he fell, and that’s it!”

The rest of the group meanwhile has reached the next level, and are astonished to see another group of survivors marching down a corridor going the opposite direction. Reverend Scott asks one of them where they're going and is told that they are following the doctor, (yet another authority figure). Reverend Scott finds the doctor at the head of the pack and tells them they’re going the wrong way. The doctor insists the only way out is forward, and tells Reverend Scott the way he wants to go—through the engine room—is flooded. However, he hasn’t seen it for himself. A woman begs the Reverend to come with them. Instead, he again shouts at the group that they are going the wrong way!

Reverend Scott returns to his flock, only now, minus Acres. He asks Mike Rogo what happened? Rogo tells him. He yells accusingly at Rogo saying he told him to keep everyone together. That Acres was hurt, that he needed help. He said he would get everyone out alive and he intends to do it dammit!

Rogo shouts back at Reverend Scott, “Who do you think you are? God himself? There was an explosion, and he fell, and that’s it!” But for Reverend Scott that's not it. What we're seeing here is Reverend Scott's dogmatic beliefs bumping up against the harsh realities of life, especially given the groups’ circumstances. He may not want to acknowledge it, but Hackman’s Preacher is starting to see that even people who fight for their life, sometimes still die. For them to live is going to require something more than just effort.

Mr. Martin, sensing the despair in the group, asks Reverend Scott where the other group of survivors were headed. Scott answers him that they are headed to the bow of the ship, then angrily shouts after them that, "but they're going the wrong way!” At this, Mike Rogo wheels on Reverend Scott and ask him how he knows? How is he so sure that he's right and they're wrong?

Reverend Scott tells him that just because 20 people decide to drown themselves by going the wrong way isn't a good reason to follow them. This is one of the great maxims of life. Just because everyone is doing something doesn't mean it's the right thing to do. Furthermore, if you follow others blindly you may find yourself in a world of hurt. The idea is to think for yourself.

After some shouting, Reverend Scott makes a deal with Rogo. He tells Rogo that he will find the way through to prove its passable. Rogo gives him fifteen minutes. “Or we’re going the other way.”

Reverend Scott finds himself traveling down another mangled corridor in darkness, which is an appropriate metaphor for this part of the journey they are on. Let's face it, very often in life we all feel like we're in the dark. Like we're not sure if we're going the right way. That maybe it's better to turn back. That maybe it's better to follow the herd. However, if we are confident of our knowledge, and have done the work to be ready, then we should trust ourselves to move forward on the path that looks like the right one to us. Even if others doubt, or don’t see the way forward you do.

Which is exactly what Reverend Scott succeeds at doing.

But before he does he spots more dead bodies. So many that he has to sit down. There is a brief moment of self-contemplation here. We wonder, is he having doubts? He must be considering the direness of his cicumstances. As we all must whenever we attempt something extremely difficult in life.

The moment is fleeting however, as Nadia shows up. She says she was scared and wanted to be with him. Sensing her worry, he reassures her that they’ll find another way out (this way is blocked).

The moment Nadia shows up we see a change in Reverend Scott's attitude and disposition. His worry and self-doubt is gone. Not entirely. Definitely not. But it is gone from the face he shows the world. Replaced instead with a confidence that he shares with Nadia, and which seems to reinvigorate him.

There are psychological studies that show that in a disaster people who survive are those who help others, and not themselves. The reason seems to be that, by doing so, they don't despair dwelling on their own predicament. Instead, they maintain a positive attitude for the sake of the people they're trying to help. The end result is that very often these people help themselves (to survive).

Meanwhile, back with the survivors they're beginning to have their doubts. It's been 15 minutes and Reverend scott still isn't back yet. Rogo wants to move on. Manny argues that they should give him more time given all he's done for them. Then, Reverend Scott returns. He says he’s seen the engine room. He’s seen the way out.

As they make their way however the water portion. Reverend scott and Robin are almost drowned. They make it through. But when they do they realize they now have a new problem. The level is flooded. The way through that Reverend Scott found is now underwater. He says that he will swim through and tie a rope that they can all use to follow. This sets up one of the greatest sequences in any movie, and one of the great onscreen heroic deaths of all time.

As Reverend Scott prepares to make the swim, Shelly Winters’s “Belle Rosen” speaks up. She tells him to let her make the swim. That she was a high school swimming champion. That though she is a big fat lady on land, in the water she is light and fast. She wants to do this for the group. All along they’ve been pulling for her, and now she has a chance to be the difference-maker, to help those who’ve been helping her. It’s her chance to get in the fight (for their lives).

Scott Reverend Scott however, refuses. He can’t let her do that. Besides, he is certain he can make the swim in one breath. He dives in and begins the underwater swim. The others time him.

In a great underwater sequence, reverend Scott swims through the flooded compartment. As with all the other levels of hell they’ve had to travel this one is filled with just as much death. Dead bodies float listlessly past him as he swims by. Until he is startled by one, causing him to jostle a piece of debris which falls on top of him pinning him down. He can't move. He can’t lift the debris. He's going to drown.

Back with the other passengers, worry is starting to set in. They all have a bad feeling. He’s been gone too long. As the others fret about what to do, looking to Mike Rogo for answers, Belle Rosen dives into the water.

“What the hell is she doing?!” Mike Rogo shouts. Her husband Manny responds, “She knows what she’s doing.”

He has faith in her because he saw the faith she had in herself, and in her God-given ability.

Belle swims through the flooded corridors, evenually finding him. She manages to free him, and rescue-swims him to safety, saving his life. She has a great line. “See, Mr. Scott, in the water, I’m a very skinny lady.”

In an absolutely heartbreaking moment, her victory is cut short, as she suffers a heart attack and falls back into the water.

Reverend Scott pulls her out of the water. He tells her to hold on, but she knows she’s done. Before she dies, she hands Reverend Scott her hai necklace and tells him to give it to Manny to give to their grandson. This is significant in that she is doing is an act of ensuring the connection between the generations, even beyond the time when she is still alive. This is actually one of the central tenets of the Covenant between God and the Jews (he will make our generations as plentiful as the stars). He act is not a sad goodbye, (though of course it is), but rather a final responsible action that will have repercussion for years, decades, generation of her family to come. In the final moments of the scene, Belle Rosen tells Reverend Scott the meaning of the symbol on her necklace. “This is the sign for life,” she tells him. “Life always matters very much.” With her final line — one of the greats in movie history — she confirms for him the correctness of his belief: life is indeed worth fighting for. It’s even worth dying for.

I literally cannot watch this scene without crying. I’ve seen this movie nine thousand times, and every single time the tears come, and I get choked up. I’m just a big softie. Or perhaps, it’s that I am affected by the sacrifice Belle Rosen makes. I’m not the only one.

In the most profound moment in the movie, Reverend Scott speaks to God for the first time.

In terms of screenplay structure, this is the part of third act sometimes referred to as “the long dark night of the soul.” Because this is when victory is very much in doubt, and the characters believe themselves to be furthest from their destination. In truth, they are closer then they’ve ever been.

This is how life works. Often, when things are darkest, you are close to success. Darkest before the dawn is the cliché — but it’s true.

First though, Reverend Scott, a Man of God who all along has been questioning his faith in his God, needs to have a revelation.

He speaks to God. He begs Him. “Not this woman.” The Preacher’s revelation is that faith, like life, requires sacrifice. And Belle Rosen has just given the ultimate sacrifice for all of them.

What does this mean for Reverend Scott’s beliefs? Might he perhaps be thinking of Father John’s final words to him? That Reverend Scott spoke only for the strong. Belle Rosen’s death calls to mind the questions that we all should be mindful of in our own lives: What about those who can’t make the swim, or the climb? What about those of us who falter along the journey? What does it take to ensure survival, not just of ourselves, but more importantly of our children, our families, and through them, our ideals and beliefs.

Which is of course what religion and faith is all about. Which is what “The Poseidon Adventure” is really about.

Mike Rogo makes the swim and appears next to Reverend Scott. At first, he doesn’t realize she’s dead. When he realizes she is, Rogo’s words are “Oh Jesus.” Which could simply be a lament, with nothing particularly religious attached to it. But given the movie’s story thus far, with all of these embedded ideas, intrinsically we understand that Mike Rogo is also speaking to his God. Reality and The Rules are out the window by this point. All that’s left is the fight for survival, and the dawning realization that to make it they are also going to need God’s providence.

In the run up to the final act of the movie, we see Reverend Scott’s dwindling flock make their way through more levels on fire. They travel up ladders, and over uneven ground. Sometimes heading to go up. This final “ascension” up the catwalk is a visual metaphor for the path these characters have had to travel. It’s basically the movie we’ve been watching for 101 minutes and 12 seconds.

If there is any doubt about the meaning of their journey, this short sequence — filmed almost entirely in a wide shot — makes it clear. This level of the ship, all iron, pipes and valves, which is ablaze with columns of fire everywhere, is an underwater hell. Their final passage before they reach their destination. The last door lies just ahead of them.

“There’s just one more door and we’re home!” Preacher shouts.

Even Mike Rogo begins to believe. “The bastard was right,” he says as he gets to his feet. Then, an explosion rocks the ship, and Rogo loses his grip on his wife, Linda, who loses her footing, and falls to her death.

Rogo wheels on Reverend Scott, eyes raging, pointing an accusing finger, and screaming at him, “Preacher! You lying, murdering, son of a bitch! You almost suckered me in! I started to believe in your promises! I started to believe we had a chance! What chance!”

He is a broken man…

“You took from me the only thing I ever loved,” Rogo weeps. “My Linda. You killed her!”

He has lost all faith, all hope, his reason to live. He crumbles to the catwalk. As if that’s not despairing enough, another explosion rocks the ship, and a jet of scalding hot steam erupts from a valve, blocking the door that is their way out. The wheel to turn off the steam valve is on the far wall…but the catwalk has fallen away in the explosion and no longer reaches it. Separating them from it is a chasm, beneath which are the churning, burning, rising flood waters.

For only the second time Reverend Scott speaks to God. “What more do you want from us?” he shouts. “We’ve come all this way! We did it on our own, no help from you! We didn’t ask you to fight for us, but dammit, don’t fight against us! Leave us alone!”

Of course, that’s not how life works. It doesn’t leave us alone. We struggle with it. In the process, often our faith, in ourselves, in others, and in God, is shaken.

This is what Reverend Scott is doing in this final monologue. He is wrestling with God. Arguing with him. This is a very Old Testament idea. Jacob wrestles with God on his journey. In Hebrew, “Israel” (the name God gives to Jacob after they wrestle) means “to struggle.”

“How many more sacrifices?” Reverend Scott asks God as he leaps to the red wheel.

The second leap of faith in this movie. He makes it.

His hands grab hold of the scalding hot wheel. Despite the enormous pain, he manages to hang on, and turn the wheel until the burning hot steam shuts off, clearing The Way forward for his flock.

Dangling from the wheel, he turns back to face them. He tells them they can make it. He calls out to Mike Rogo. He tells him to “Get them through!” turning over responsibility for the flock to Rogo. In his sacrifice, Reverend Scott is attempting to give Mike Rogo back his faith.

Borgnoine’s “Mike Rogo” is not ready yet. He sits crumbled on the catwalk, not moving. Now it is calm, even-tempered, Mr. Martin who shouts at Rogo. Filled with the faith Reverend Scott imparted to them along with the burning desire to live, Mr. Martin screams at Rogo. He asks him, “what kind of a policeman were you?” He accuses him of having done nothing but complain and be negtive. In other words, Mike Rogo has been the character with no faith, no beliefs in anything higher than himself, except perhaps for his wife, Linda.

Now, however, with Mr. Martin calling him out, he stands up.

“Alright, that’s enough,” he proclaims as the music swells.

We’re still not sure Rogo believes, as much as he’s just pissed-off, but he gets up and takes the lead. He leads them…to a dead end.

Until Robin reminds him of the thing he’s told them all along: this is right where they want to be (a child shall lead them, right). This is “shaft alley” the thinnest part of the hull.

Suddenly, they think they hear voices.

They grab wrenches and start banging on the hull. They get no response. But Mr. Martin shouts at the group that Reverend Scott would never quit! They keep banging.

This time, someone bangs back.

They’ve been rescued. Mike Rogo throws down his wrendch and says, his faith fully restored, a smile on his face for the first time the entire movie, as he says, “The Preacher was right. That beautiful, son of a bitch, was right!” He ruffles Robin’s hair. As the rescuers burn through the hull to get the survivors out, we see close-ups of all their faces. They’ve all been changed. Not merely because of the disaster they’ve survived. But because of how the journey restored their faith. To make this point, Ernest Borgnine’s “Rogo” looks back behind him at the way they came. Through a hatch, we can see the orange light of the fires of the hell from which they’ve just emerged, flickering on the wall. Rogo weeps. Then looks up as the rescuers appear in the hull.

In case there is any thought to the idea that perhaps they just got lucky and that’s why they were rescued, the movie spares time for one final dialogue exchange as the rescuers ask the survivors how many of them there are. Mr. Martin tells them six. Then asks the rescuers if they found anyone else? Anyone from the bow? (meaning the other group following the ship’s doctor).

The rescuers shake their head. The only survivors were Reverend Scott’s.

The movie life lesson, (and there are many in this movie to be sure), but the central one seems to be: In life it is important to have faith in yourself, but it is also necessary to have faith in a Power higher than yourself, if you want to reach your destinations in life. However, faith alone is not enough. God can’t do it for you and the prayers that get answered are the ones that are backed up with real effort, courage, and force of will.

That is what makes The Poseidon Adventure one of the great life lesson movies of all time.

Thanks for reading Movie Life Lessons! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Like

Comment

Share

No posts

© 2022 Jeremy Elice. See privacy, terms and information collection notice

Publish on SubstackMovie Life Lessons is on Substack – the place for independent writing

0 notes