#The Harvest | Integrating Mississippi's Schools | Article

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

What Happened When a Fearless Group of Mississippi Sharecroppers Founded Their Own City

Strike City was born after one small community left the plantation to live on their own terms

— September 11, 2023 | NOVA—BPS

A tin sign demarcated the boundary of Strike City just outside Leland, Mississippi. Photo by Charlie Steiner

In 1965 in the Mississippi Delta, things were not all that different than they had been 100 years earlier. Cotton was still King—and somebody needed to pick it. After the abolition of slavery, much of the labor for the region’s cotton economy was provided by Black sharecroppers, who were not technically enslaved, but operated in much the same way: working the fields of white plantation owners for essentially no profit. To make matters worse, by 1965, mechanized agriculture began to push sharecroppers out of what little employment they had. Many in the Delta had reached their breaking point.

In April of that year, following months of organizing, 45 local farm workers founded the Mississippi Freedom Labor Union. The MFLU’s platform included demands for a minimum wage, eight-hour workdays, medical coverage and an end to plantation work for children under the age of 16, whose educations were severely compromised by the sharecropping system. Within weeks of its founding, strikes under the MFLU banner began to spread across the Delta.

Five miles outside the small town of Leland, Mississippi, a group of Black Tenant Farmers led by John Henry Sylvester voted to go on strike. Sylvester, a tractor driver and mechanic at the A.L. Andrews Plantation, wanted fair treatment and prospects for a better future for his family. “I don’t want my children to grow up dumb like I did,” he told a reporter, with characteristic humility. In fact it was Sylvester’s organizational prowess and vision that gave the strikers direction and resolve. They would need both. The Andrews workers were immediately evicted from their homes. Undeterred, they moved their families to a local building owned by a Baptist Educational Association, but were eventually evicted there as well.

After two months of striking, and now facing homelessness for a second time, the strikers made a bold move. With just 13 donated tents, the strikers bought five acres of land from a local Black Farmer and decided that they would remain there, on strike, for as long as it took. Strike City was born. Frank Smith was a Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee worker when he went to live with the strikers just outside Leland. “They wanted to stay within eyesight of the plantation,” said Smith, now Executive Director of the African American Civil War Memorial and Museum in Washington, D.C. “They were not scared.”

Life in Strike City was difficult. Not only did the strikers have to deal with one of Missississippi’s coldest winters in history, they also had to endure the periodic gunshots fired by white agitators over their tents at night. Yet the strikers were determined. “We ain’t going out of the state of Mississippi. We gonna stay right here, fighting for what is ours,” one of them told a documentary film team, who captured the strikers’ daily experience in a short film called “Strike City.” “We decided we wouldn’t run,” another assented. “If we run now, we always will be running.”

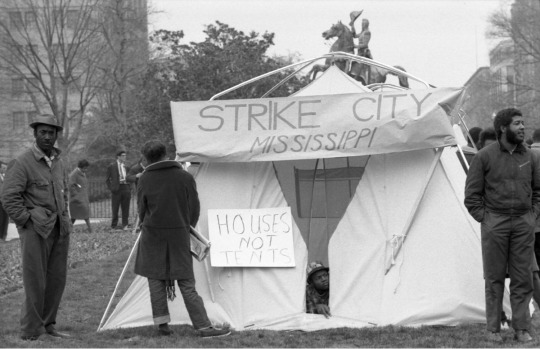

But the strikers knew that if their city was going to survive, they would need more resources. In an effort to secure federal grants from the federal government’s Office of Economic Opportunity, the strikers, led by Sylvester and Smith, journeyed all the way to Washington D.C. “We’re here because Washington seems to run on a different schedule,” Smith told congressmen, stressing the urgency of the situation and the group’s needs for funds. “We have to get started right away. When you live in a tent and people shoot at you at night and your kids can’t take a bath and your wife has no privacy, a month can be a long time, even a day…Kids can’t grow up in Strike City and have any kind of a chance.” In a symbolic demonstration of their plight, the strikers set up a row of tents across the street from the White House.

John Henry Sylvester, left, stands outside one of the tents strikers erected in Washington, D.C. in April 1966. Photo by Rowland Sherman

“It was a good, dramatic, in-your-face presentation,” Smith told American Experience, nearly 60 years after the strikers camped out. “It didn’t do much to shake anything out of the Congress of the United States or the President and his Cabinet. But it gave us a feeling that we’d done something to help ourselves.” The protestors returned home empty-handed. Nevertheless, the residents of Strike City had secured enough funds from a Chicago-based organization to begin the construction of permanent brick homes; and to provide local Black children with a literacy program, which was held in a wood-and-cinder-block community center they erected.

The long-term sustainability of Strike City, however, depended on the creation of a self-sufficient economy. Early on, Strike City residents had earned money by handcrafting nativity scenes, but this proved inadequate. Soon, Strike City residents were planning on constructing a brick factory that would provide employment and building material for the settlement’s expansion. But the $25,000 price tag of the project proved to be too much, and with no employment, many strikers began to drift away. Strike City never recovered.

Still, its direct impact was apparent when, in 1965, Mississippi schools reluctantly complied with the 1964 Civil Rights Act by offering a freedom-of-choice period in which children were purportedly allowed to register at any school of their choice. In reality, however, most Black parents were too afraid to send their children to all-white schools—except for the parents living at Strike City who had already radically declared their independence . Once Leland’s public schools were legally open to them, Strike City kids were the first ones to register. Their parents’ determination to give them a better life had already begun to pay dividends.

Smith recalled driving Strike City’s children to their first day of school in the fall of 1970. “I remember when I dropped them off, they jumped out and ran in, and I said, ‘They don't have a clue what they were getting themselves into.’ But you know kids are innocent and they’re always braver than we think they are. And they went in there like it was their schoolhouse. Like they belonged there like everybody else.”

#The Harvest | Integrating Mississippi's Schools | Article#NOVA | PBS#American 🇺🇸 Experience#Mississippi Delta#Cotton | King#Abolition | Slavery#Black Sharecroppers#Mechanized Agriculture#Mississippi Freedom Labor Union (MFLU)#Leland | Mississippi#Black Tenant Farmers#John Henry Sylvester | Truck Driver | Mechanic#A.L. Andrews Plantation#Fair Treatment | Prospects#Baptist Educational Association#Frank Smith | Student | Nonviolent Coordinating Committee#Strike City#Executive Director | African American | Civil War Memorial & Museum | Washington D.C.#Federal Government | Office of Economic Opportunity#Congress of the United States | The President | Cabinet#Brick Homes | Black Children | Literacy Program#Wood-and-Cinder-Block | Community Center

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sharecropping: Slavery Rerouted

Though slavery was abolished in 1865, sharecropping would keep most Black Southerners impoverished and immobile for decades to come.

— Published: August 16, 2023 | By Jared Tetreau | The Harvest: Integrating Mississippi's Schools | Article | Sunday August 20, 2023

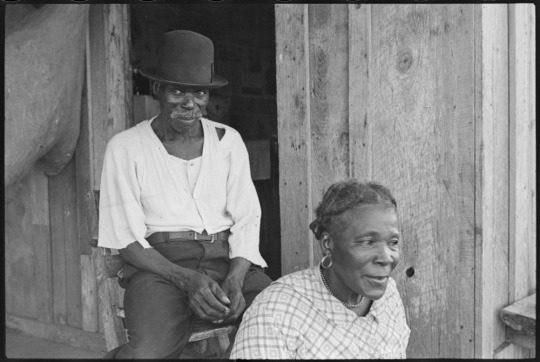

Sharecropper's children. Montgomery County, Alabama, 1937, photographer Arthur Rothstein, Library of Congress

“The White Folks had all the Courts, all the Guns, all the Hounds, all the Railroads, all the Telegraph Wires, all the Newspapers, all the Money and nearly all the Land – and we had only our Ignorance, our Poverty and our Empty Hands.” — an anonymous Sharecropper, Elbert County, Georgia, ca. 1900

On January 1, 1867 in Marshall County, Mississippi, Cooper Hughes and Charles Roberts entered into an agreement. In their contract with landowner I.G. Bailey, Hughes and Roberts, both formerly enslaved men, agreed to work 40 acres of corn and 20 acres of cotton on Bailey’s land, along with “all other work…necessary to be done to keep [the farm] in good order,” for the duration of 1867. In exchange for their labor, Hughes, Roberts and their families would be “furnished” with stipends of meat, a mule for plowing, a plot of land to grow a garden, separate cabins and one-third and one-half of the corn and cotton crops respectively.

On that first day of 1867, Hughes and Roberts joined a growing number of newly freed African Americans turning toward a new agricultural arrangement in the South. It would come to be called “sharecropping.” In the decades that followed, sharecropping would grow into what scholar Wesley Allen Riddle called the “predominant capital-labor arrangement” in the region, defining how hundreds of thousands of Black Southerners made a living and supported their families. But once up and running, sharecropping itself would deny the formerly enslaved their rights and liberties as free American citizens for nearly one hundred years.

Sharecropper "Mother Lane" Pulaski County, Arkansas,1937, United States Resettlement Administration, photographer Ben by Shahn, Library of Congress

What is Sharecropping?

Sharecropping is a system by which a tenant farmer agrees to work an owner’s land in exchange for living accommodations and a share of the profits from the sale of the crop at the end of the harvest.

The system emerged after the Civil War, when the southern economy lay in ruins. With the Confederate monetary system wiped out, farm land decimated, and slavery abolished under the 13th Amendment, access to labor and capital was extremely limited among Southern landowners. For former slaves, federal proposals to redistribute land fell apart in the 1860s, leaving millions without the promises of full citizenship guaranteed to them by the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments.

Pitched as a solution for both groups, sharecropping was presented to the formerly enslaved as land ownership by proxy. It put an end to work in “gangs” under an overseer, while keeping Black workers within the agricultural sector, preferably on the same land where they had been held captive, and incentivizing high crop yields, benefitting landowners. But even though the old plantation system had changed and some day-to-day activities were delegated to sharecroppers, sharecropping proved a fundamentally unequal arrangement, organized to keep Black farmers from ever achieving economic or social mobility.

As writer Doug Blackmon notes, many white southerners after Emancipation were determined not to pay for something they had once had for free—Black labor.

Many landowners at the end of the Civil War were furious at the idea of paying Black workers whom they’d owned only months before. As a result, landowners developed systems adjacent to slavery. On the plantations, this took the form of sharecropping, though the transformation did not happen overnight.

Black Americans in the South were eager to exercise their newfound freedoms after the war. As historian Wesley Allen Riddle writes, “the most basic and symbolic” of these freedoms was “mobility” itself. The formerly enslaved left their plantations in droves, some looking for work in the South’s devastated cities, while others looked for—and were given by the Union Army—vacant land on which to raise a farm. But work in cities was hard to come by. Only about 4 percent of Freedmen were able to find work in southern cities after the war, and many who came there were relegated to shantytowns of the formerly enslaved. As for those that were given vacant lands by the army, they were forced out when President Andrew Johnson canceled Field Order No. 15 in the fall of 1865, returning these properties to their white owners.

While many formerly enslaved did leave the plantations after the war, many others could not. Those trying to leave faced horrific violence and intimidation from their former owners. As Union General Carl Schurz reported in his testimony to Congress in 1865, “In many instances, negroes who walked away from plantations, or were found upon the road, were shot or otherwise severely punished.”

With land ownership all but closed to them, and urban service work extremely limited, many Freedmen had little choice but to return to the plantations by the end of the 1860s. Their motives for this were mixed. Though economic pressures were strong, many wanted to reunite with loved ones who had been sold during slavery, and saw some appeal in working in an agricultural sector that they were familiar with.

Twenty to 50 acre plots, a cabin to live in and farming supplies were promised to them, all in exchange for about 50 percent of their harvest. Freedmen envisioned a self-sustained life working a plot of land, raising a garden, and providing for their families as they wanted. But these hopes were dashed as the pitfalls of sharecropping quickly became clear.

Sharecroppers, Pulaski County, Arkansas. 1937, photographer Ben by Shahn, United States Resettlement Administration, Library of Congress

Life as a Sharecropper

By design, sharecropping deprived Black farmers of economic agency or mobility. Although they were no longer legally enslaved, sharecroppers were kept in place by debt. As their income was dependent on both the profits from the sale of the crop and the whims of the landowners, sharecroppers had to find means to sustain themselves during the rest of the year. They were forced to purchase food, seed, clothing and other goods on credit, typically from a plantation “commissary” owned by the landlord.

At the end of the harvest, when revenue from the crop was “settled up,” the sharecroppers’ portion of the profits was calculated against their debts. As a result, sharecroppers often ended the year owing their landlords money. What could not be paid off was carried into the next year, creating a cycle of indebtedness that was often impossible to break.

Sharecroppers in debt to their landlord were subject to laws that tied them to the land. If they attempted to move, any new tenancy contracts they signed with other landlords could be voided by their existing ones. If they ran away, they could be brought back to their landlord in chains, and made to work as a prisoner for no pay at all.

Even if sharecroppers did not try to leave, they still faced massive obstacles in achieving any kind of solvency. For instance, many Southern states limited how and to whom sharecroppers could sell their part of the crop. In Alabama, cotton had to be sold and transported during the day, and could only be purchased by a state-defined “legitimate” merchant. As sharecroppers couldn’t afford to lose a day’s work to take their crop to market, these laws curtailed their ability to sell their product at the best possible price.

In addition, individual freedoms were crushed by tenancy contracts, many of which included arbitrary clauses forbidding alcohol consumption, speaking to other sharecroppers in the fields or allowing visitors on rented land.

Black sharecroppers could not seek redress through the political system either. Despite the ratification of the 14th and 15th Amendments, the southern “Redemption” that followed the withdrawal of Union troops from the South in 1876-7 ensured that the federal government would not enforce Black voting rights. Black elected officials disappeared from Congress and state legislatures, and attempts at organizing Black voters were brutally suppressed, as in New Orleans in July of 1866, where a convention of Black voters was attacked by a white mob under police protection that killed an estimated 200 people.

Educational opportunities were also sparse. In 1872, white Southerners pressured Congress to abolish the Freedmen's Bureau, a federal agency designed to provide food, shelter, clothing, medical services and land to newly freed African Americans. With the dissolution of the Bureau, few resources remained for the approximately 80 percent of Black people who were illiterate.

Sharecropping, with its prohibitive restrictions on physical and economic mobility, its use of violence and intimidation and its emphasis on maximum production, denied Black Southerners the ability to gain wealth, to exercise the freedom granted them by Emancipation and to gain the education they were deprived of during enslavement. The system existed, in conjunction with other institutions, to exploit Black labor at a minimum “relative loss” to white landowners while keeping the Black population underfoot.

As Black sharecropper Ed Brown said of his experience, “hard work didn’t get me nowhere.”

Sharecropper's cabin, Southeast Missouri Farms. 1938, photographer Russell Lee, Library of Congress

Sharecropping’s Decline and Legacy

After dominating the southern agricultural economy for decades, sharecropping was, like most other farming practices, upended by the rise of new technologies. While these changes were delayed by the Great Depression, sharecropping had become obsolete in many areas of the South by the mid-twentieth century. With increased mechanization, white planters’ demand for Black labor dried up.

Also during this time, Jim Crow obstructions to Black enfranchisement, as well as state-sanctioned violence against Black people, were directly challenged by the Civil Rights Movement and the landmark legislation it helped enact. The Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1968 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 deconstructed de jure segregation across the South in housing and public accommodation, while empowering the federal government to secure the right to vote for Black Southerners.

As scholars Paru Shah and Robert S. Smith note, enfranchisement, desegregation and the decline of sharecropping weakened “the broader agenda of White Supremacy to crush African American socioeconomic mobility,” but did not destroy it. The effects of centuries of Black economic and social oppression, represented in part by sharecropping, are still felt today. Limited access to capital, to mobility, and to representation during Jim Crow and before it denied Black Americans the ability to save, invest or accumulate wealth, concentrating inherited fortunes in the hands of white families and shaping the present class makeup.

For nearly a century, sharecropping defined Southern agriculture and hindered Black economic advancement. The system reflected a multidude of attempts by the white power structure to keep Black workers stagnant, achieving this through intimidation, physical violence and exploitation. Ultimately, aided by organized action, shifting technological and economic conditions and the determination of sharecroppers themselves, the oppressive reality of sharecropping ended. But in the endemic inequities of American political and economic life, its legacy persists.

#NOVA | PBS#Sharecropping#Slavery Rerouted#Black Southerners#The Harvest#Integration#Mississippi's Schools#Jared Tetreau#Article#White Folks | Possessor of Courts | Guns | Railroads | Telegraph Wires | Newspapers | Money | Land#Marshall County | Mississippi#Cooper Hughes | Charles Roberts#Landowner | I.G. Bailey#Sharecropper | Ignorence | Poverty | Empty Hands#African Americans#Civil War#Confederate Monetary System#Doug Blackmon#Emancipation#Historian | Wesley Allen Riddle#Union General Carl Schurz#Southern States | Alabama#Redemption#Educational Opportunities#Freedmen's Bureau#Black Sharecropper | Ed Brown#Civil Rights Movement#Civil Rights Acts of 1964 & 1968 | Voting Rights Act of 1965#Scholars: Paru Shah | Robert S. Smith

3 notes

·

View notes