#Executive Director | African American | Civil War Memorial & Museum | Washington D.C.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

What Happened When a Fearless Group of Mississippi Sharecroppers Founded Their Own City

Strike City was born after one small community left the plantation to live on their own terms

— September 11, 2023 | NOVA—BPS

A tin sign demarcated the boundary of Strike City just outside Leland, Mississippi. Photo by Charlie Steiner

In 1965 in the Mississippi Delta, things were not all that different than they had been 100 years earlier. Cotton was still King—and somebody needed to pick it. After the abolition of slavery, much of the labor for the region’s cotton economy was provided by Black sharecroppers, who were not technically enslaved, but operated in much the same way: working the fields of white plantation owners for essentially no profit. To make matters worse, by 1965, mechanized agriculture began to push sharecroppers out of what little employment they had. Many in the Delta had reached their breaking point.

In April of that year, following months of organizing, 45 local farm workers founded the Mississippi Freedom Labor Union. The MFLU’s platform included demands for a minimum wage, eight-hour workdays, medical coverage and an end to plantation work for children under the age of 16, whose educations were severely compromised by the sharecropping system. Within weeks of its founding, strikes under the MFLU banner began to spread across the Delta.

Five miles outside the small town of Leland, Mississippi, a group of Black Tenant Farmers led by John Henry Sylvester voted to go on strike. Sylvester, a tractor driver and mechanic at the A.L. Andrews Plantation, wanted fair treatment and prospects for a better future for his family. “I don’t want my children to grow up dumb like I did,” he told a reporter, with characteristic humility. In fact it was Sylvester’s organizational prowess and vision that gave the strikers direction and resolve. They would need both. The Andrews workers were immediately evicted from their homes. Undeterred, they moved their families to a local building owned by a Baptist Educational Association, but were eventually evicted there as well.

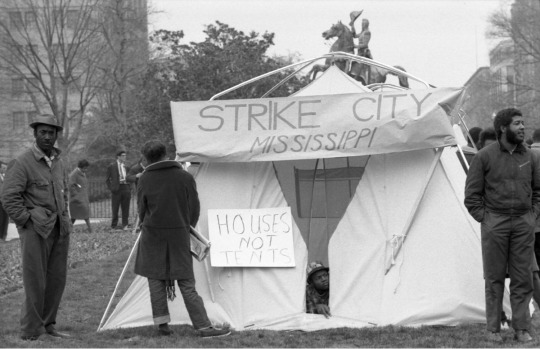

After two months of striking, and now facing homelessness for a second time, the strikers made a bold move. With just 13 donated tents, the strikers bought five acres of land from a local Black Farmer and decided that they would remain there, on strike, for as long as it took. Strike City was born. Frank Smith was a Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee worker when he went to live with the strikers just outside Leland. “They wanted to stay within eyesight of the plantation,” said Smith, now Executive Director of the African American Civil War Memorial and Museum in Washington, D.C. “They were not scared.”

Life in Strike City was difficult. Not only did the strikers have to deal with one of Missississippi’s coldest winters in history, they also had to endure the periodic gunshots fired by white agitators over their tents at night. Yet the strikers were determined. “We ain’t going out of the state of Mississippi. We gonna stay right here, fighting for what is ours,” one of them told a documentary film team, who captured the strikers’ daily experience in a short film called “Strike City.” “We decided we wouldn’t run,” another assented. “If we run now, we always will be running.”

But the strikers knew that if their city was going to survive, they would need more resources. In an effort to secure federal grants from the federal government’s Office of Economic Opportunity, the strikers, led by Sylvester and Smith, journeyed all the way to Washington D.C. “We’re here because Washington seems to run on a different schedule,” Smith told congressmen, stressing the urgency of the situation and the group’s needs for funds. “We have to get started right away. When you live in a tent and people shoot at you at night and your kids can’t take a bath and your wife has no privacy, a month can be a long time, even a day…Kids can’t grow up in Strike City and have any kind of a chance.” In a symbolic demonstration of their plight, the strikers set up a row of tents across the street from the White House.

John Henry Sylvester, left, stands outside one of the tents strikers erected in Washington, D.C. in April 1966. Photo by Rowland Sherman

“It was a good, dramatic, in-your-face presentation,” Smith told American Experience, nearly 60 years after the strikers camped out. “It didn’t do much to shake anything out of the Congress of the United States or the President and his Cabinet. But it gave us a feeling that we’d done something to help ourselves.” The protestors returned home empty-handed. Nevertheless, the residents of Strike City had secured enough funds from a Chicago-based organization to begin the construction of permanent brick homes; and to provide local Black children with a literacy program, which was held in a wood-and-cinder-block community center they erected.

The long-term sustainability of Strike City, however, depended on the creation of a self-sufficient economy. Early on, Strike City residents had earned money by handcrafting nativity scenes, but this proved inadequate. Soon, Strike City residents were planning on constructing a brick factory that would provide employment and building material for the settlement’s expansion. But the $25,000 price tag of the project proved to be too much, and with no employment, many strikers began to drift away. Strike City never recovered.

Still, its direct impact was apparent when, in 1965, Mississippi schools reluctantly complied with the 1964 Civil Rights Act by offering a freedom-of-choice period in which children were purportedly allowed to register at any school of their choice. In reality, however, most Black parents were too afraid to send their children to all-white schools—except for the parents living at Strike City who had already radically declared their independence . Once Leland’s public schools were legally open to them, Strike City kids were the first ones to register. Their parents’ determination to give them a better life had already begun to pay dividends.

Smith recalled driving Strike City’s children to their first day of school in the fall of 1970. “I remember when I dropped them off, they jumped out and ran in, and I said, ‘They don't have a clue what they were getting themselves into.’ But you know kids are innocent and they’re always braver than we think they are. And they went in there like it was their schoolhouse. Like they belonged there like everybody else.”

#The Harvest | Integrating Mississippi's Schools | Article#NOVA | PBS#American 🇺🇸 Experience#Mississippi Delta#Cotton | King#Abolition | Slavery#Black Sharecroppers#Mechanized Agriculture#Mississippi Freedom Labor Union (MFLU)#Leland | Mississippi#Black Tenant Farmers#John Henry Sylvester | Truck Driver | Mechanic#A.L. Andrews Plantation#Fair Treatment | Prospects#Baptist Educational Association#Frank Smith | Student | Nonviolent Coordinating Committee#Strike City#Executive Director | African American | Civil War Memorial & Museum | Washington D.C.#Federal Government | Office of Economic Opportunity#Congress of the United States | The President | Cabinet#Brick Homes | Black Children | Literacy Program#Wood-and-Cinder-Block | Community Center

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Florida's Emancipation Day Celebrations Held Locally

The African American Heritage Society of East Pasco County, Inc. and the Florida African American Heritage Preservation Network hosted the first annual Emancipation Day with a celebration at Agnes Lamb Park in Dade City on May 20. The activities honored traditions of the African American heritage. As for history, on May 20, 1865, General Edward McCook announced in Tallahassee, Florida, that all enslaved people were free. This was the first notice of the proclamation of freedom. Florida Celebrates Emancipation Day on May 20 In contemporary times, folks hear about this as Juneteenth in other locales, but in Florida, the emancipation was actually on May 20. The Emancipation Proclamation ending slavery was delivered by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, in Washington, D.C. Ironically the Civil War ended just a few days after the May 20th receipt. It is believed that President Lincoln’s actions altered the goals of the Civil War with the Emancipation Proclamation. Therefore, its delivery just after the Union’s victory at the Battle of Antietam was strategic. Historians also theorize that the proclamation would inspire many, especially the enslaved in the confederacy, to support the Union. The Program Celebrates Florida’s Emancipation Day: May 20, 1865 Brockmann, Sara. Reenactors recreate a reading of the Emancipation Proclamation at the Knott House Museum in Tallahassee. 2015. State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory. The evening’s written program of the first annual event in Dade City stated, “in the month of May, we honor those intrinsic values related to natural rights and freedom as we proudly salute one of the most significant days in the annals of Florida’s History: May 20, 1865.” On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing enslaved people in the rebelling Southern states. More than two years later on May 10th, Union General Edward McCook arrived in Tallahassee. General McCook established his headquarters at the Hagner House, now known as the Knott House. Fred Hearns, Curator of Black History from the Tampa Bay History Center, is seen giving the Keynote Address. Image courtesy of Facebook. Keynote speaker, Fred Hearns, Curator of Black History from the Tampa Bay History Center, explained the significance of the date to him and related that the event has been celebrated in Tampa for a number of years, as well as at the Chinsegut Hill Historic Site in Hernando County. Mr. Hearns conveyed that Tallahassee has been honoring Emancipation Day for many years. Hearns invited all to the Tampa Bay History Center's upcoming event on June 19, 2024, entitled “Fabric of Freedom.” Fashion and Black history will collide at the “Fabric of Freedom” event, providing an innovative program, with more information available at the Tampa Bay History Center site at https://tampabayhistorycenter.org/blog/. The master of ceremonies for the evening was the Reverend Dr. Emery Ailes, President of Lifeline University. Recognition of dignitaries who also served as greeters included: Mayor Scott Black of Dade City, Stephanie Black, Executive Director of the Pioneer Museum, Madonna Jervis Wise, Educator/Historian/Author, Angela Lewis-Bennett of Branch NAACP #5630, Eric Theodore, African-American Heritage Society of East Pasco County, and James Walters, Dade City Chief of Police. All presented greetings, review of projects, and congratulations on the newly formed celebration. Mayor Black announced that the City Commission would be delivering a proclamation to the group at the upcoming meeting. Madonna Wise spoke for herself, Stephanie Black, and the team who developed the Dade City Walking Tour: Mary Katherine Mason Alston, Margaret Angell, Stephanie Black, Britton Janning, James Walters, Melody Floyd, Wayne Sweat, Eric Baker, and Judge Lynn Tepper. Sixteen Stops on the Dade City Historic Walking Tour feature African American History Highland's Motors, part of the Dade City Historic Walking Tour. Image colorized and restored by Bill Price. Courtesy of his Facebook page. Madonna highlighted sixteen of the stops on the Dade City Walking Tour that particularly feature African American history and invited suggestions for additions. Madonna explained that the Dade City Self-Guided QR and Walking Tour was the brainchild of Alston and Angel, and the editing was expertly completed by team members, Imani Asukile and Judge Tepper. Angela Lewis- Bennett and Eric Theodore discussed the projects underway including scholarships and community projects. A Perfect Reading of Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation Emancipation Day Celebration image courtesy of Tampa Bay History Center. The culmination of the evening, which is customary across the communities for the day, was the dramatic reading of Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation by several local dignitaries, aiming to foster a deeper connection to this pivotal moment in history. With perfect symmetry, each of the four readers recited a portion of the proclamation. The readers included: Mayor Pro Tempore Normita Woodard, the Reverend Dr. Brian Butler of Saint John Missionary Baptist Church, Mayor Scott Black, and Dennis Feltwell. With real conviction and perfect diction, the four readers presented emotional deliveries. Remarks were also given by Jesse Pisors, President of Pasco Hernando State College who praised the African American Society of East Pasco and the organizers for the important remembrances. He also brought greetings as the newly appointed President of Pasco Hernando State College from all three campuses. Storytelling and Line Dancing in the African Tradition Conclude the Event To conclude the evening, the audience was brought back to two of the traditions of the African American ancestors which included storytelling and line dancing. Windell Campbell came to the stage to tell two eloquent stories. Campbell is a retired schoolteacher of 41 years who has been awarded many accolades for his storytelling, including work with many Tampa Bay libraries and festivals. He performed a rendition of the flying Africans that is rooted in an African legend from 1803 about a slave woman and her baby in the cotton fields as well as a symbolic story of the ‘Selfish Giant’ and his garden as a beautiful metaphor of kindness and giving. Storytelling was a traditional African American folklore for the enslaved. The evening was concluded with a couple of rounds of line dancing, as the celebration ended with a sense of joy and hope. (By the way, the dignitaries and readers were pretty good at the line dancing!) An image from the 2023 Florida Emancipation Day Celebration in Brooksville by Diane Bedard. Florida Emancipation Day is celebrated at Chinsegut Hill Historic Site Also On May 18, another Florida Emancipation Day celebration was held at Chinsegut Hill Historic Site. Fred Hearns led this captivating program alongside Gary Ellis, director emeritus of the Gulf Archaeology Research Institute, and Rodney Kite-Powell, director of the Touchton Map Library at Tampa Bay History Center. They uncovered the fascinating historical significance of the Hill. Michael Jones, Ed.D. shared insights into the local implications of recent archaeological findings, while Jesse Pisors, Ed.D., President of Pasco-Hernando State College, welcomed visitors to explore the historic house with complimentary tours offered by the college. This was followed by a Q&A session with Rodney Kite-Powell right after the presentations, followed by a 30-minute house tour! The first tour began at 11 a.m., with the final tour beginning at 4 p.m. The Tampa Bay History Center has made a concerted effort to bring knowledge and awareness of local history involving African American people to Florida’s Nature Coast. This is the second year that the Florida Emancipation Day celebration was held at Chinsegut Hill Historic Site. Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Charles Ogletree

Charles James Ogletree, Jr. (born December 31, 1952) is the Jesse Climenko Professor at Harvard Law School, the founder of the school's Charles Hamilton Houston Institute, and the author of numerous books on legal topics.

Education

Ogletree was born in Merced, central California. He earned both his B.A. (1974, with distinction) and M.A. (1975) in political science from Stanford University and his J.D. from Harvard Law School in 1978.

Career

Lawyer and professor

After graduating from law school, Ogletree worked for the District of Columbia Public Defender Service until 1985, first as a staff attorney, then as training director, trial chief, and deputy director. As an attorney, he has represented such notable figures as rapper Tupac Shakur. In 1985, he became a professor at Harvard Law School. In 1992, he became the Jesse Climenko Professor of Law and vice dean for clinical programs.

Media appearances and contributions

Moderator of television programs, including State of the Black Union; Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community; (with others) Ethics in America; Hard Drugs, Hard Choices, Liberty and Limits: Whose Law, Whose Order?; Credibility in the Newsroom, Race to Execution, 2006; Beyond Black and White; Liberty & Limits: Whose Law, Whose Order?; That Delicate Balance II: Our Bill of Rights; and other Public Broadcasting Service broadcasts.

He was a guest on many television programs, including Nightline, This Week with David Brinkley, McNeil-Lehrer News Hour, Crossfire, Today Show, Good Morning America, Larry King Live, Cochran and Company :Burden of Proof, Tavis Smiley, Frontline, America's Black Forum, and Meet the Press

On NBC news radio, he was a legal commentator on the O. J. Simpson murder case.

He contributed to periodicals such as New Crisis, Public Utilities Fortnightly, and Harvard Law Review.

In 2003 he visited the University of Washington, Seattle, to speak on reparations. At the time several of the majority-Black audience asked him how much money could potentially be wrought from reparations. While Ogletree would not elaborate on a particular number he seemed to support an audience member's suggestion of more than $2 trillion or more.

In February 2011, he gave a three-part lecture at Harvard Law School entitled "Understanding Obama", which provides an inside look at President Barack Obama's journey from boyhood in Hawaii to the White House. Professor Ogletree is set to publish a book about President Obama, but will not release it until after the 2012 Presidential election.

Ogletree appears in the 2014 documentary film Hate Crimes in the Heartland, providing an analysis of the Tulsa Race Riots.

Community and professional affairs

He was a member of the board of trustees at Stanford University. He founded the Merced, California scholarships. He was the chairman of the board of trustees of University of the District of Columbia. He used to be the national president of the Black Law Students Association.

Stature and public life

Ogletree taught both Barack and Michelle Obama at Harvard; he has remained close to Barack Obama throughout his political career. He appeared briefly on the joint The Daily Show-Colbert Report election night coverage of the 2008 presidential election, making a few remarks about his personal knowledge of the Obamas.

Ogletree has written opinion pieces on the state of race in the United States for major publications. Ogletree also served as the moderator for a panel discussion on civil rights in baseball on March 28, 2008 that accompanied the second annual Major League Baseball civil rights exhibition game the following day between the New York Mets and the Chicago White Sox.

On July 21, 2009, Ogletree issued a statement in response to the arrest of his Harvard colleague and client, Professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr., whose arrest at his own home became a major news story about the nexus of politics, police power, and race that summer. Professor Ogletree later wrote a book about the events titled The Presumption of Guilt: The Arrest of Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Race, Class and Crime in America.

After the September 2009 death of Senator Ted Kennedy, Ogletree's name was suggested as one of the possible appointees to Kennedy's seat as a "placeholder" until a special election could be held. Other names rumored to be in contention were Michael Dukakis and several people who had held important Massachusetts or national Democratic positions: Paul G. Kirk (a former chair of the Democratic National Committee), Nick Littlefield (a former Kennedy chief of staff), Robert Travaglini, and Shannon O'Brien.

He is a founder of the Benjamin Banneker Charter Public School (www.banneker.org) and serves on the school's foundation board. The school library is named in his honor.

Awards

He received the National Conference on Black Lawyers People's Lawyer of the Year Award, the Man of Vision Award, Museum of Afro-American History (Boston), the Albert Sacks-Paul A. Freund Award for Teaching Excellence, Harvard Law School in 1993, the Ellis Island Medal of Honor, 1995, the Ruffin-Fenwick Trailblazer Award, and the 21st Century Achievement Award, Urban League of Eastern Massachusetts.

Works

The Presumption of Guilt: The Arrest of Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Race, Class and Crime in America (Palgrave-Macmillan 2010)

When Law Fails (Charles J. Ogletree & Austin Sarat eds.)

From Lynch Mobs to the Killing State: Race and the Death Penalty in America (ed. with Austin Sarat, New York University Press 2006)

All Deliberate Speed: Reflections on the First Half-Century of Brown v. Board of Education (W.W. Norton & Company 2004)

Brown at 50: The Unfinished Legacy (ed. with Deborah L. Rhode, American Bar Association 2004)

Beyond the Rodney King Story: An Investigation of Police Conduct in Minority Communities, (ed. with others, Northeastern University Press Boston, Massachusetts 1995)

Contributor to books, including

Faith of Our Fathers: African-American Men Reflect on Fatherhood

ed. by Andre C. Willis

Reason and Passion: Justice Brennan's Enduring Influence

Lift Every Voice and Sing

, 2001

The Rehnquist Court: Judicial Activism on the Right

, 2002.Ogletree, Charles J. "The Rehnquist Revolution in Criminal Procedure" in

The Rehnquist Court

(Herman Schwartz ed., Hill and Wang Publishing, 2002).Ogletree, Charles J. "The Challenge of Race and Education" in

How to Make Black America Better

(Smiley ed., 2001).Ogletree, Charles J. "Privileges and Immunities for Basketball Stars and Other Sport Heroes?" in

Basketball Jones

(Boyd & Shropshire eds., 2000).Ogletree, Charles J. "The Tireless Warrior for Racial Justice" in

Reason

(Rosenkranz & Schwartz eds., 1998).

Articles

Ogletree, Charles J. "Commentary: All Deliberate Speed: Reflections on the First Half-Century of Brown vs. Board of Education," 66 Montana Law Review 283 (2005).Ogletree, Charles J. "All Deliberate Speed?: Brown's Past and Brown's Future," 107 West Virginia Law Review 625 (2005).Ogletree, Charles J. "The Current Reparations Debate," 5 University of California Davis Law Review 36 (2003).Ogletree, Charles J. "Does America Owe Us? (Point-Counterpoint with E.R. Shipp, on the Topic of Reparations)," Essence Magazine, February 2003.Ogletree, Charles J. "The Case for Reparations," USA Weekend Magazine, February 2003.Ogletree, Charles J. "Repairing the Past: New Efforts in the Reparations Debate in America," 2 Harvard Civil Rights- Civil Liberties Law Review 38 (2003).Ogletree, Charles J. "Reparations for the Children of Slaves: Litigating the Issues," 2 University of Memphis Law Review 33 (2003).Ogletree, Charles J. "The Right's and Wrongs of e-Privacy," Optimize Magazine, March 2002.Ogletree, Charles J. "From Pretoria to Philadelphia: Judge Higginbotham's Racial Justice Jurisprudence on South Africa and the United States," 20 Yale Law and Policy Review 383 (2002).Ogletree, Charles J. "The Challenge of Providing Legal Representation in the United States, South Africa and China," 7 Washington University Journal of Law and Policy 47 (2002).Ogletree, Charles J. "Judicial Activism or Judicial Necessity: D.C. Court's Criminal Justice Legacy," 90 Georgetown Law Journal 685 (2002).Ogletree, Charles J. "Black Man's Burden: Race and the Death Penalty in America," 81 Oregon Law Review 15 (2002).Ogletree, Charles J. "A Diverse Workforce in the 21st Century: Harvard's Challenge," Harvard Community Resource, Spring 2002.Ogletree, Charles J. "Fighting a Just War Without an Unjust Loss of Freedom," Africana.com, October 11, 2001.Ogletree, Charles J. "Unequal Justice for Al Sharpton," Africana.com, August 21, 2001.Ogletree, Charles J. "A. Leon Higginbotham, Jr.: A Reciprocal Legacy of Scholarship and Advocacy," 53 Rutgers Law Review 665 (2001).Ogletree, Charles J. "An Ode to St. Peter: Professor Peter M. Cicchino," 50 American University Law Review 591 (2001).Ogletree, Charles J. "America's Schizophrenic Immigration Policy: Race, Class, and Reason," 41 Boston College Law Review 755 (2000).Ogletree, Charles J. "A Tribute to Gary Bellow: The Visionary Clinical Scholar," 114 Harvard Law Review 420 (2000).Ogletree, Charles J. "A. Leon Higginbotham's Civil Rights Legacy," 34 Harvard Civil-Rights Civil Liberties Law Review 1 (1999).Ogletree, Charles J. "Personal and Professional Integrity in the Legal Profession: Lessons from President Clinton and Kenneth Starr," 56 Washington & Lee Law Review 851 (1999).Ogletree, Charles J. "Matthew O. Tobriner Memorial Lecture: The Burdens and Benefits of Race in America," 25 Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly 219 (1998).Ogletree, Charles J. "The President's Role in Bridging America's Racial Divide," 15 Thomas M. Cooley Law Review 11 (1998).Ogletree, Charles J. "The Conference on Critical Race Theory: When the Rainbow Is Not Enough," 31 New England Law Review 705 (1997).Ogletree, Charles J. "Race Relations and Conflicts in the United States The Limits of Hate Speech: Does Race Matter?" 32 Gonzaga Law Review 491 (1997).

Articles in a Newspaper

Ogletree, Charles J. "Court Should Stand By Bake Ruling," Boston Globe, April 1, 2003, Op-Ed.Ogletree, Charles J. "The Future of Admissions and Race," Boston Globe, May 20, 2002, Op-Ed.Ogletree, Charles J. "Litigating the Legacy of Slavery," New York Times, March 31, 2002, Op-Ed.Ogletree, Charles J. "The U.S. Needn't Shrink from Durban," Los Angeles Times, August 29, 2001, Op-Ed.Ogletree, Charles J. "The Real David Brock," Boston Globe, June 30, 2001, Op-Ed.Ogletree, Charles J. "The Court's Tarnished Reputation," Boston Globe, December 12, 2000, Op-Ed.Ogletree, Charles J. "Why Has the G.O.P. Kept Blacks Off Federal Courts?" New York Times, August 18, 2000, Op-Ed.

Reports or Studies

Ogletree, Charles J. "Judicial Excellence, Judicial Diversity: The African American Federal Judges Report" (2003).

Presentations

Ogletree, Charles J. A Call to Arms: Responding to W.E.B. DuBois's Challenge to Wilberforce, Wilberforce University Founder's Day Luncheon (February 11, 2003).Ogletree, Charles J. Grinnell College Special Convocation Address (January 22, 2003).Ogletree, Charles J. Remembering Dr. King's Legacy: Promoting Diversity and Promoting Patriotism, King County Bar Association MLK Luncheon (January 17, 2003).Ogletree, Charles J. Baum Lecture, University of Illinois Urbana-Champagne (November 2002).Ogletree, Charles J. University of California-Davis Barrett Lecture: The Current Reparations Debate, University of California-Davis Law School (October 22, 2002).Ogletree, Charles J. Why Reparations? Why Now?, Buck Franklin Memorial Lecture and Conference on Reparations, University of Tulsa College of Law, Oklahoma (September 25, 2002).Ogletree, Charles J. Northeastern University Valerie Gordon Human Rights Lecture, Northeastern University School of Law (April 2002).Ogletree, Charles J. Sobota Lecture, Albany School of Law (Spring 2002).Ogletree, Charles J. Mangels Lecturship, University of Washington Graduate School (Spring 2002).

Wikipedia

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why remembering matters for healing

http://bit.ly/2qoSVfH

Six memorial candles are lit during a Holocaust Remembrance Day ceremony at Sharkey Theater on board Naval Station Pearl Harbor. U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class James E. Foehl

April 12 marks Holocaust Remembrance Day. Each year communities and schools plan various events such as reading the names of Holocaust victims and survivors, forums of Holocaust survivor speakers, or panel discussions with historians. These events run through an entire week of remembrance.

Such formal days of remembrance are important. As a sociologist who studies grief and justice, I have seen how these events and permanent memorials can be both healing and inspirational. I will share four reasons why remembrance activities are important.

1. Telling one’s story

An essential part of healing rests on the ability to tell one’s story – to have someone listen and acknowledge pain and suffering. Scholars have explained how stories help people make sense of their experience. Stories can provide a release of emotion and help one connect to others when learning to live with loss.

How one grieves is dependent on social and cultural contexts. If one is surrounded, for example, by people who refuse to acknowledge someone’s loss, it will be a more traumatic experience than being in a culture that recognizes the loss.

Remembrance days, such as the Holocaust Remembrance, and memorials, in particular, can provide opportunities to share stories with a community, especially for those who might have trouble finding people to listen to them.

Bible verse on a wall of the Holocaust Museum, Washington, D.C. hannahlmyers/pixabay.com, CC BY

2. Providing public bonds

Research shows that many people develop continuing bonds with individuals who have died. Often people want to keep a deceased loved one’s memory in their lives. Remembrance events can present opportunities and rituals to help in sustaining those connections.

A person establishes private bonds with the deceased, through internal conversations, private rituals, or holding on to symbolic objects. Public bonds, on the other hand, require more people to help make connections, such as telling their story to an audience and hearing others’ stories through films, books, speakers or museum exhibits.

Community events that are scheduled as part of a day of remembrance provide resources for people who may want to develop more public bonds.

3. Documenting history through stories

Storytelling does not just benefit survivors and victims’ families. Individual stories can help the world understand the human toll of mass tragedy.

When entering the Holocaust Memorial and Museum in Washington D.C., for example, visitors are handed an ID card that describes an individual who lived, or died, in Europe during the Holocaust.

Further along, there is a permanent exhibit that includes a large wall of portraits.

Portrait in the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C. Nancy Berns, CC BY

Seeing family pictures and knowing how their lives were devastated poignantly brings the tragedy home in a way that numbers alone cannot do. Such stories become the building blocks of history, for they are never simply individual. They are told in specific historical times and they help us understand the relationships between people and society.

Portrait in the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C. Nancy Berns, CC BY

Portrait in the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C. Nancy Berns, CC BY

Portrait in the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C. Nancy Berns, CC BY

4. Inspiring other movements

Stories can also help inspire healing movements for other mass tragedies. One example of this inspiration can be found in the work of Bryan Stevenson, founder and executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative. Stevenson and his team have been helping audiences hear the stories of people who have been victims of racial injustice in the United States.

Bryan Stevenson at TED. James Duncan Davidson, CC BY-SA

Stevenson was inspired by the Holocaust memorials he visited when he went to Germany:

“You can’t go anywhere in Germany without seeing reminders of the people’s commitment not to repeat the Holocaust.”

It led him to build the National Museum for Peace and Justice, which will open on April 26 in Montgomery, Alabama. The museum will include a history of lynchings in the United States that occurred between the Civil War and World War II. EJI has documented over 4,000 lynchings that mostly targeted African-Americans. As Stevenson explains, the history of terrorism through lynching shapes the context of racial injustice in the United States. The museum aims to open up conversations and memorialize lives lost.

Conversations about a painful past are not something to be feared but rather remembered and shared. Healing does not come by closing the books and turning away from individual stories of trauma. Healing starts when the devastating consequences of injustice and loss are seen and acknowledged.

Nancy Berns does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

0 notes

Photo

At its 123rd Anniversary Celebration, the Historical Society of Washington, D.C. will honor Dr. Frank Smith, founder of the African American Civil War Memorial and Museum, with its fourth Visionary Historian Award. The Visionary Historian Award is presented to an individual whose lifetime body of work represents the highest achievement in the study of Washington, D.C. and related history. About Frank Smith Frank Smith, Jr., Ph.D., has been standing up for justice for close to six decades. Born in 1942 on a peach plantation in Newman, Georgia, Smith entered Morehouse College in Atlanta at age 16 and quickly found his calling as an activist. He left Morehouse to register voters and was an early member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). He registered voters in Mississippi, ran a Head Start program, and organized sharecroppers. During Freedom Summer (1964), Smith raised funds for Fannie Lou Hamer and other members of the Mississippi Freedom Party to travel to the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, where they ended up not being seated but did succeed in raising awareness of the lack of voting rights for African Americans in this country. In 1968 Smith moved to Washington and became active in tenants’ rights, housing, and other issues in his Adams Morgan neighborhood. In 1980 he received a Ph.D. from Union Institute (Ohio). He was elected to the DC Board of Education in 1979 and to the first of four terms on the DC Council in 1982. Representing Ward 1, he chaired the Council’s Housing and Economic Development Committee, the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority, and the Baseball Commission. In 1992 Smith formed the African American Civil War Memorial Freedom Foundation to tell the largely forgotten story of the 209,145 African American soldiers and sailors who had fought for the Union. He began planning, fundraising, and building public and private support for an African American Civil War Memorial and Museum, and in July 1998 presided over the memorial’s dedication. The memorial, a low wall inscribed with the names of the black soldiers and sailors who served in the war, is located at 10th and U Streets NW. Its centerpiece is a 9-foot-high bronze sculpture, The Spirit of Freedom by Ed Hamilton of Louisville, Kentucky. In January 1999, just after leaving the Council, Smith opened the African American Civil War Museum in a building adjacent to the memorial. The museum, which attracts more than 200,000 visitors per year, moved in 2011 to a larger space in the former Grimke School nearby on Vermont Avenue. As the museum’s founder and executive director, a noted authority on African Americans in the Civil War, a civil rights activist, and as an elected official in service to the District of Columbia, Smith has received numerous awards and recognitions.

1 note

·

View note

Text

New Post has been published on Mortgage News

New Post has been published on http://bit.ly/2lHy4TB

battlefield-of-memory-asphalt-where-a-black-cemetery-is-said-to-have-stood

Macedonia Baptist Church members, locals and others gather for a rally, march and protest at the historic African American church on River Road on Feb. 12. (Katherine Frey/The Washington Post)

Tim Bonds first heard the stories about the bones in the late 1960s, from construction workers who came to his father’s gas station in Bethesda for a cold drink or a quick game of craps.

Change was stirring along this quiet stretch of River Road, home to a century-old community founded by freed slaves and known today as Westbard. The crews were excavating the future site of a 15-story apartment and office tower across from the new Westwood Shopping Center.

“When they found a body,” recalled Bonds, 57, “they’d blow a whistle and they’d shut the job down.”

It seemed to him that the whistle blew pretty often. He remembers the men talking about human remains being pushed back under the dirt, down a steep slope toward a storm sewer, so excavation could resume more quickly. He and his pals sometimes slipped over to the site hoping for a glimpse of something ghoulish. But they never saw anything.

For a half-century, such stories were mostly forgotten. Then plans for new construction led to fresh details about the cemetery that historians say once stood on land behind the high-rise, and painful questions about what may have happened to the remains buried there.

A few hundred people gather outside Macedonia Baptist Church for a rally and march to demand an accounting of an almost-forgotten black burial site that was located nearby. (Katherine Frey/The Washington Post)

The issue has pitted Montgomery County officials and the prospective developer against a tiny Baptist church whose members fear history will once again be bulldozed, this time to make way for an aboveground parking garage near proposed high-rises, townhouses and a revamped shopping center.

The county and the developer, New York-based Equity One, have promised to work with the community and say no plans will be approved for the site until an archaeological investigation is complete. But members of Macedonia Baptist Church, the last standing vestige of the former black enclave, want to halt the process until Equity One agrees to include a museum about the former African American enclave in its project.

“It should be a place of reflection and a place for people to meditate about how important it is to preserve human rights,” said Marsha Coleman-Adebayo, head of Macedonia’s social justice ministry. “We need to memorialize this experience so that our children have the opportunity to learn from our mistakes.”

‘Like a lost colony’

The neighborhood that would become Westbard was home in the late 19th century to African Americans who had worked on Montgomery County’s farms and tobacco plantations since before the Civil War.

By the 1950s, according to research by the Little Falls Watershed Alliance, about 30 families lived on the sloping terrain by the old Georgetown branch of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, which would later become the Capital Crescent Trail. They farmed, worked as laborers or domestics in the nearby white neighborhood of Somerset, or toiled at Bethesda Blue Granite Co.’s quarry near Willett Branch.

“What I tell my grandkids, it was just like a lost colony,” said Harvey M. Matthews Sr., 72, whose family farm was located on the site of what is now the Kenwood Station Shopping Center, home to a Whole Foods, Bethesda Bagels and other upscale staples.

“When I travel around the country and people ask where I was born, I tell them, ‘Bethesda,’ ” added Matthews, who recalls playing hide-and-seek at the cemetery as a boy. “And they say, ‘There were black people in Bethesda?’ ”

Harvey M. Matthews Sr., 72, talks on the spot where an African American cemetery is said to have once stood. (Katherine Frey/The Washington Post)

There were also ballfields, a segregated elementary school and a tavern called the Sugar Bowl. And, according to research conducted by the county in preparing a new land-use plan for Westbard — deeds, state archives, the Congressional Record and old newspaper accounts — there was, at one time, a cemetery.

Historians with the Montgomery County Parks and Planning departments cite a 1911 tax assessment that shows the purchase of a one-acre parcel west of River Road, which includes what is now the parking lot behind Westwood Tower.

The buyer was White’s Tabernacle No. 39, a chapter of a black fraternal society called the Ancient Order of the Sons and Daughters, Brothers and Sisters of Moses. A notation on the assessment says “used as a graveyard,” and newspaper clippings say that James Loughborough, a prominent land owner and Confederate veteran, presented the Montgomery County Board of Commissioners in 1911 with a petition opposing a black burial ground at River Road.

At around the same time it purchased the River Road land, White’s Tabernacle sold a cemetery it owned in the Fort Reno section of Tenleytown. A 1914 Washington Post article mentioned a bill pending before the House of Representatives to allow disinterment of the Tenleytown graves. A later article said the site contained 192 bodies. In a 2015 report marked “confidential,” county senior planner Sandra Youla said the River Road site “likely contained remains disinterred” from the Tenleytown cemetery.

The society sold the cemetery in 1959, around the time that the African American families of Westbard began to sell their land and scatter. Historians have been unable to document what happened to the graves.

Laszlo Tauber in 1999. (Lois Raimondo/ TWP)

River Road, meanwhile, started to boom. One of the most active builders was Laszlo Tauber, a Hungarian Jewish surgeon and Holocaust survivor who made much of his fortune constructing office space to lease to the federal government. He headed a syndicate of other physician-investors that bought land in Westbard.

In 1966, Tauber developed plans for the high-rise, designed by prominent D.C. architect John d’Epagnier. The upper floors would be apartments, the lower levels the offices of the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission.

D’Epagnierdied in 1977. In 2015, county parks department researchers borrowed documents about the Westwood Tower project from his son Arnold, as part of their work on the land-use plan. On the day senior historian Jamie Kuhns and cultural resources manager Joey Lampl returned the materials, Arnold D’Epagnieroffered them his own memories of when the high-rise was built.

According to notes written by Kuhns and Lampl after the conversation, d’Epagnier recalled riding a pickup truck with his father and a family priest, “taking burlap bags with bones” from the construction site to Howard Chapel, a historically black cemetery in rural northern Montgomery.

The priest and young Arnold fished in a nearby creek while his father dug a makeshift grave, according to the notes, which are on file at the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission. The architect buried the remains, and the priest blessed them.

D’Epagnier recanted his story a year later, as Macedonia reviewed the county’s historical findings and began pushing to memorialize the cemetery. “I cannot say with any certainty that my vague recollections . . . are in any way accurate,” he said in an email to Lampl. “I recommend that you not consider any of those details as part of your work on this matter.”

In an email to The Post, he wrote, “I truly regret ever casually trying to recall my memories from so long ago.”

Meshach Louie, 7, holds up a sign he made during a rally outside Macedonia Baptist Church, where he and his family are members. (Katherine Frey/The Washington Post)

Tauber died in 2002, at age 87. A spokesman for the charitable foundation run by his children, Ingrid and Alfred Tauber, said they have no recollection of their father mentioning a gravesite on the land his group had purchased.

All company documents related to Westwood Tower were shredded in 2015, 10 years after Tauber sold the building to a New York real estate investor. Equity One bought it in 2013, for $25 million.

Unanswerable questions

Quiet disposal of remains was illegal but not unusual in the 1960s, experts in cemetery restoration say, especially in places where countryside became suburb and suburb became city.

In Alexandria, the original Contrabands and Freedmen’s Cemetery was first disturbed by 19th-century brickmakers digging for clay. Roads and a gas station were built later. Construction of the new Woodrow Wilson Bridge — a federally funded project subject to preservation laws — led to the restoration of the cemetery and creation of a three-acre memorial dedicated in 2014.

While the Westbard plan does not use federal dollars, it coincides with a surge of interest in recognizing such sacred places, and, perhaps, a new willingness by governments to preserve them.

Equity One Executive Vice President William Brown said the firm stands ready to cooperate with the county and the church: “We’re not trying to do anything to desecrate remains or cover anything up.”

The firm is close to hiring the Ottery Group, a cultural resource consulting firm, to examine the parking lot for evidence of graves. Montgomery Planning Director Gwen Wright said she is speaking with two prominent anthropologists about serving as independent peer reviewers of Ottery’s work.

Officials promise no construction will be approved without a full investigation, including ground-penetrating radar. If remains are located, police will be notified, as state law requires. County leaders say they will do what they can to pay homage to the site, perhaps as part of the proposed restoration of Willett Branch, the creek near the site that was lined with concrete in the 1950s to serve as a storm sewer.

But Macedonia Baptist Church members remain skeptical, saying they have been kept at arms length in their efforts to honor what Coleman-Adebayo calls “a battlefield of memory.”

At a planning board meeting Thursday, the Rev. Segun Adebayo, Macedonia’s interim pastor, said church members want the county to pay for the cemetery study instead of Equity One. “The old saying is still true,” said Adebayo, who is married to Coleman-Adebayo. “ ‘He who pays the piper calls the tune.’ ”

Wright said her agency has no money to pay for such a study, which could be costly. She added that it is customary for the land owner to foot the bill.

Adebayo also called for a criminal investigation if test results show that graves were disturbed and remains were moved. “Where did they go? Was it legal? Was it moral?”

Earlier this month, members of Macedonia and neighboring River Road Unitarian Universalist Congregation sang spirituals and placed flowers at the parking lot. Then the group moved to the sycamore trees near the Whole Foods parking lot, which Matthews said are all that remain of his family’s farm.

“Three dogs, two horses, chickens and pigs,” Matthews said, fighting tears. “This is my yard. I was here first.”

Harvey Matthews stands near a sycamore tree that he says was planted by his parents on their family farm, now a shopping strip anchored by Whole Foods on River Road. (Katherine Frey/The Washington Post)

With key decision-makers long deceased, a full accounting of what happened at the site is unlikely. No records have been located to confirm whether remains were found years ago, or to document the relocation of any graves after the cemetery was sold.

“The desecration of this community’s historic burial ground decades ago was certainly a tragedy that should have been prevented,” Montgomery County Council President Roger Berliner (D-Potomac-Bethesda), whose district includes Westbard, wrote to planning board chair Casey Anderson earlier this month. “I do not have the historical knowledge of the events that led to that act, and perhaps neither do you. But we do have an opportunity to do things differently today and moving forward.”

Bonds, who rents the land for his two service stations from Equity One, will lose his lease if and when the company starts building. Before he leaves, he said, he’d welcome a resolution to the childhood mystery that unfolded down the street.

“I’d kind of like to see them find it,” he said of the cemetery. “Everybody who’s lost should be found. I believe in history.”

Read more:

Should Va.’s black cemeteries get the same state support as Confederate burial grounds?

2002 Obituary: Hungarian Holocaust survivor Laszlo Tauber

Leggett and Baker: Former law school dean and his student have become political partners and peers

0 notes