#The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

New Findings For Alexander Hamilton’s Artillery Company!!

Today I came across “new” (new to me, anyway--nor have I seen a Hamilton biographer or scholar mention this) Captain Hamilton information and I feel bad for the people within my vicinity inside my campus library who had to hear my shocked squeal.

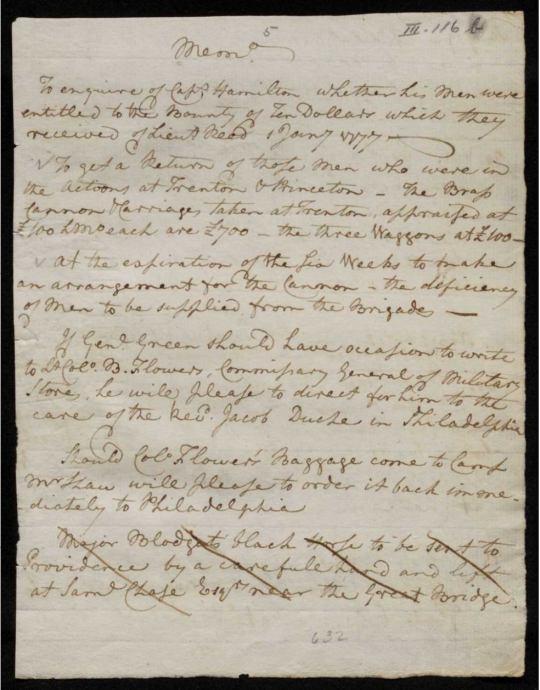

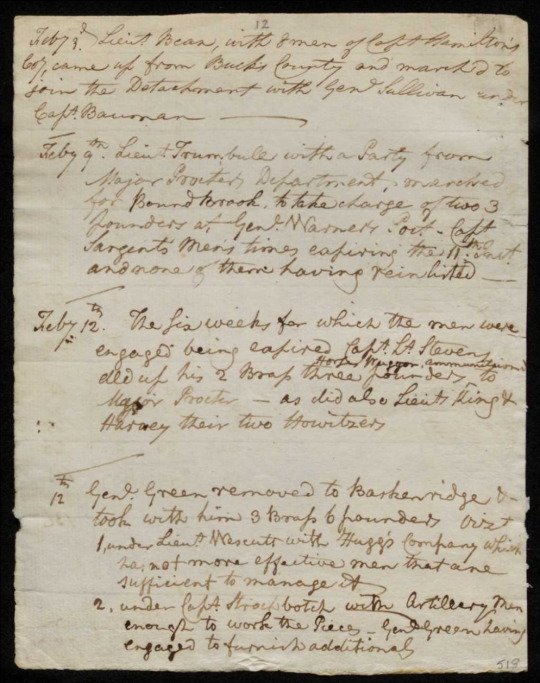

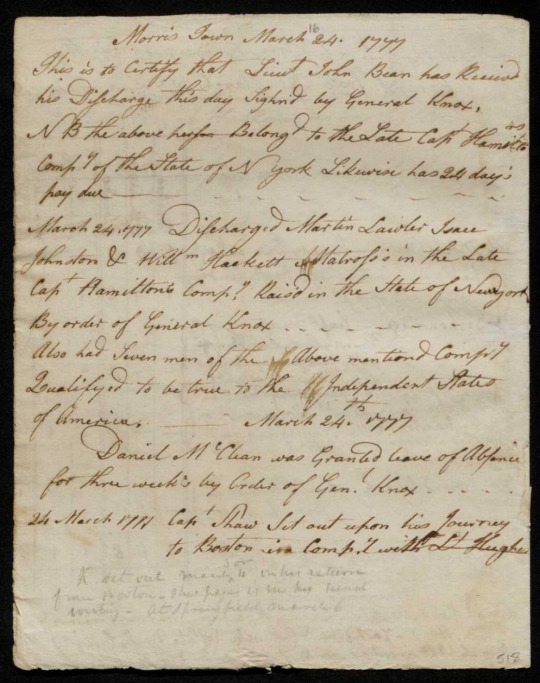

Within the Henry Knox Papers of the Gilder Lehrman Collection held by the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History is an “Artillery record book” which was written by Colonel Samuel Shaw for Knox’s regiment of artillery between January 12, 1777 and March 24, 1777. The book itself is only 16 pages (which includes the cover page), but it contains all sorts of troop movements, artillery inventory, and other notes.

The following (under the cut) is a chronological rundown of all the times Hamilton or his men are mentioned in the book, along with the images themselves (as unfortunately the database that the Knox Papers were digitized to, American History 1493-1945, is limited to institutional access. However, it can be found here):

First up, on page five (seen above), Colonel Shaw wrote a series of "memos," or tasks needing completion. One of these, as seen at the top of the page, included "To enquire of Capt Hamilton whether his men were entitled to the Bounty of Ten Dollars which they received of Lieut Reed 1 Jany [January] 1777 --". The start of the new year came of course on the heels of the Battle of Trenton fought on December 26, 1776, wherein Hamilton's cannons played a major role.

Next (and the most interesting to me), on page twelve (seen above) Shaw wrote a series of troop movements. Dated February 3, 1777, the colonel wrote that "Lieut [John] Bean, with 8 men of Capt Hamilton's Coy [Company] came [up?] from Bucks County and marched to join the Detachment with Genl [John] Sullivan and Capt [Sebastian] Bauman --". At this time, Hamilton was still in recovery from the illness he developed prior to Trenton, and the only other remaining officer in his company was his Third Lieutenant Thomas Thompson. This would thus mean that Hamilton and Thompson were left to watch over those that remained with the company while Bean and eight enlisted men were away.

Lastly, on the final page of the record book (seen above) a series of discharges for men in Hamilton's company were written on March 24, 1777. By that time, Alexander Hamilton had joined Washington's staff as an aide-de-camp. Colonel Shaw, and another person who has not been identified, explicitly wrote:

Morris Town March 24, 1777

This is to certify that Lieut John Bean has Received his Discharge this day Sign'd by General Knox, N B the above person Belong'd to the late Capt Hamilton's Compy [Company] of the State of N[ew] York Likewise has 24 days pay due --

March 24, 1777 Discharged Martian Laulen[,] Isaac Johnston & Will'm [William] Hackett Matross's in the Late Capt Hamilton's Compy, Rais'd in the State of New York By order of General Knox . . . .

Also had seven men of the above mentioned compy Qualifyed [Qualified] to be true to the Independent States of America --

Note: the names of the matrosses discharged were cross-referenced with the names found in Alexander Hamilton's artillery company pay book for making my above transcription.

This entire record makes me extremely happy. I have new dates and more minute details and therefore a more concrete timeline surrounding Hamilton and the men of his company, yay!! Lately I have become very interested in the company's continuing service in the American Revolution after Hamilton's departure, and this record just gave me some fascinating information that links to some other information I have found on the whereabouts of some of these men written about above. But this is daring to open a can of worms that should be saved for a later post.

Frankly, it does not surprise me that I have not read about this record previously. It is so detailed and routine that it doesn't stand out necessarily on its own in the wider scope of things. However, as regards The American Icarus (and another project I may or may not be considering tackling?), this new information is very interesting and helpful. And I hope someone else here finds it interesting too.

#I would update my captain hamilton timeline if not for having hit my image and hyperlink limit on that post 😭#grace's random ramble#alexander hamilton#amrev#historical alexander hamilton#captain hamilton#henry knox#amrev fandom#historical hamilton#american revoluton#historical documents#18th century letters#continental artillery#continental army#george washington#battle of trenton#american history#historical research#historical resources#henry knox papers#gilder lehrman institute of american history#the american icarus#TAI#my projects#my writing#writeblr#new york provincial company of artillery

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

June 2, 2024

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

JUN 03, 2024

Today is the one-hundredth anniversary of the Indian Citizenship Act, which declared that “all non-citizen Indians born within the territorial limits of the United States be, and they are hereby, declared to be citizens of the United States: Provided, That the granting of such citizenship shall not in any manner impair or otherwise affect the right of any Indian to tribal or other property.”

That declaration had been a long time coming. The Constitution, ratified in 1789, excluded “Indians not taxed” from the population on which officials would calculate representation in the House of Representatives. In the 1857 Dred Scott v. Sandford decision, the Supreme Court reiterated that Indigenous tribes were independent nations. It called Indigenous peoples equivalent to “the subjects of any other foreign Government.” They could be naturalized, thereby becoming citizens of a state and of the United States. And at that point, they “would be entitled to all the rights and privileges which would belong to an emigrant from any other foreign people.”

The Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868, established that “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” But it continued to exclude “Indians not taxed” from the population used to calculate representation in the House of Representatives.

In 1880, John Elk, a member of the Winnebago tribe, tried to register to vote, saying he had been living off the reservation and had renounced the tribal affiliation under which he was born. In 1884, in Elk v. Wilkins, the Supreme Court affirmed that the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution did not cover Indigenous Americans who were living under the jurisdiction of a tribe when they were born. In 1887 the Dawes Act provided that any Indigenous American who accepted an individual land grant could become a citizen, but those who did not remained noncitizens.

As Interior Secretary Deb Haaland pointed out today in an article in Native News Online, Elk v. Wilkins meant that when Olympians Louis Tewanima and Jim Thorpe represented the United States in the 1912 Olympic games in Stockholm, Sweden, they were not legally American citizens. A member of the Hopi Tribe, Tewanima won the silver medal for the 10,000 meter run.

Thorpe was a member of the Sac and Fox Nation, and in 1912 he won two Olympic gold medals, in Classic pentathlon—sprint hurdles, long jump, high jump, shot put, and middle distance run—and in decathlon, which added five more track and field events to the Classic pentathlon. The Associated Press later voted Thorpe “The Greatest Athlete of the First Half of the Century” as he played both professional football and professional baseball, but it was his wins at the 1912 Olympics that made him a legend. Congratulating him on his win, Sweden’s King Gustav V allegedly said, “Sir, you are the greatest athlete in the world.”

Still, it was World War I that forced lawmakers to confront the contradiction of noncitizen Indigenous Americans. According to the Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History, more than 11,000 American Indians served in World War I: nearly 5,000 enlisted and about 6,500 were drafted, making up a total of about 25% of Indigenous men despite the fact that most Indigenous men were not citizens.

It was during World War I that members of the Choctaw and Cherokee Nations began to transmit messages for the American forces in a code based in their own languages, the inspiration for the Code Talkers of World War II. In 1919, in recognition of “the American Indian as a soldier of our army, fighting on foreign fields for liberty and justice,” as General John Pershing put it, Congress passed a law to grant citizenship to Indigenous American veterans of World War I.

That citizenship law raised the question of citizenship for those Indigenous Americans who had neither assimilated nor served in the military. The non-Native community was divided on the question; so was the Native community. Some thought citizenship would protect their rights, while others worried that it would strip them of the rights they held under treaties negotiated with them as separate and sovereign nations and was a way to force them to assimilate.

On June 2, 1924, Congress passed the measure, its supporters largely hoping that Indigenous citizenship would help to clean up the corruption in the Department of Indian Affairs. The new law applied to about 125,000 people out of an Indigenous population of about 300,000.

But in that era, citizenship did not confer civil rights. In 1941, shortly after Elizabeth Peratrovich and her husband, Roy, both members of the Tlingit Nation, moved from Klawok, Alaska, to the city of Juneau, they found a sign on a nearby inn saying, “No Natives Allowed.” This, they felt, contrasted dramatically with the American uniforms Indigenous Americans were wearing overseas, and they said as much in a letter to Alaska’s governor, Ernest H. Gruening. The sign was “an outrage,” they wrote. “The proprietor of Douglas Inn does not seem to realize that our Native boys are just as willing as the white boys to lay down their lives to protect the freedom that he enjoys."

With the support of the governor, Elizabeth started a campaign to get an antidiscrimination bill through the legislature. It failed in 1943, but passed the House in 1945 as a packed gallery looked on. The measure had the votes to pass in the Senate, but one opponent demanded: "Who are these people, barely out of savagery, who want to associate with us whites with 5,000 years of recorded civilization behind us?"

Elizabeth Peratrovich had been quietly knitting in the gallery, but during the public comment period, she said she would like to be heard. She crossed the chamber to stand by the Senate president. “I would not have expected,” she said, “that I, who am barely out of savagery, would have to remind gentlemen with five thousand years of recorded civilization behind them of our Bill of Rights.” She detailed the ways in which discrimination daily hampered the lives of herself, her husband, and her children. She finished to wild applause, and the Senate passed the nation’s first antidiscrimination act by a vote of 11 to 5.

Indigenous veterans came home from World War II to discover they still could not vote. In Arizona, Maricopa county recorder Roger G. Laveen refused to register returning veterans of the Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation, including Frank Harrison, to vote. He cited an earlier court decision saying Indigenous Americans were “persons under guardianship.” They sued, and the Arizona Supreme Court agreed that the phrase only applied to judicial guardianship.

In New Mexico, Miguel Trujillo, a schoolteacher from Isleta Pueblo who had served as a Marine in World War II, sued the county registrar who refused to enroll him as a voter. In 1948, in Trujillo v. Garley, a state court agreed that the clause in the New Mexico constitution prohibiting “Indians not taxed” from voting violated the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments by placing a unique requirement on Indigenous Americans. It was not until 1957 that Utah removed its restrictions on Indigenous voting, the last of the states to do so.

The 1965 Voting Rights Act protected Native American voting rights along with the voting rights of all Americans, and they, like all Americans, are affected by the Supreme Court’s hollowing out of the law and the wave of voter suppression laws state legislators who have bought into Trump’s Big Lie have passed since 2021. Voter ID laws that require street addresses cut out many people who live on reservations, and lack of access to polling places cuts out others.

Katie Friel and Emil Mella Pablo of the Brennan Center noted in 2022 that, for example, people who live on Nevada’s Duckwater reservation have to travel 140 miles each way to get to the closest elections office. “As the first and original peoples of this land, we have had only a century of recognized citizenship, and we continue to face systematic barriers when exercising the fundamental and hard-fought-for right to vote,” Democratic National Committee Native Caucus chair Clara Pratte said in a press release from the Democratic Party.

As part of the commemoration of the Indian Citizenship Act, the Democratic National Committee is distributing voter engagement and protection information in Apache, Ho-Chunk, Hopi, Navajo, Paiute, Shoshone, and Zuni.

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#Heather Cox Richardson#Code Talkers#Letters from an American#History#American History#Native American#voting rights#citizenship

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The First Congress"

"The First Congress" by J. Rogers, 1787.

I found this image from a database my school library has with the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. I found this particularly interesting because of the collection of figures it incorporates. They (top to bottom, left to right): Patrick Henry, Charles Thomson, Peyton Randolph, Jacob Duché, and Richard Henry Lee. The author included the President of the First Continental Congress (Randolph), the Secretary (Thomson), the Chaplain (Duché), and two major figures of that body (Henry and Lee) but I want to understand why he believed that these 5 individuals were the ones worthy of representing the entire First Continental Congress. I am also interested in how this piece would change had it been created at a different time -- who would be the major players then?

#i love this kind of stuff#like thinking about how things are influenced by the time period in which they were created/happened#i also love historical memory#also they did thomson dirty with the picture they chose im ngl#like everyone else got the cute ones of them in their prime and thomson got the one of him really old#although part of me thinks that this was created after 1787 because of the picture they used for thomson but im not getting into that today#amrev#continental congress#charles thomson#patrick henry#peyton randolph#jacob duché#robert henry lee

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christianity and colonization, how this document gave European colonizers the right to land grab and enslave people of color. Why are so many people Christians?

0 notes

Note

A better source about the people featured in that photoshoot.

I feel like the term “white slavery”, while somewhat broadly used to refer to sex work at the time, was more specifically used to refer to what gets called trafficking now (and then as now, focusing only on kidnapped well off white women, just more openly). And there were just as many panicked stories about good middle class girls barely escaping ~Them~ (Chinese, Jewish, Black) as there are fb posts now about “almost being trafficked” because they saw a brown person somewhere around them. It’s also about drawing a line between sw deserving of care or not

Content warning: mentions of child sexual abuse in the reply, graphic description of abuse in the linked articles; racism, slavery.

Yes, and the OP of the post did respond to me to clarify that that is what they meant! One of my friends had actually been reading about the topic and how allegations of sex trafficking were used against men of other ethnicities who were in romantic partnerships with white women, and against said groups in general. In some cases the woman had even left her white husband for being abusive, but what mattered to public opinion was not the welfare of the woman herself but that she had ceased to be under the control of a white man.

But the reason I mentioned it is that it reminded me of something I read about. Now that I'm typing this, I'm thinking about it a little more. There was a famous case of investigative journalism in the 1880s, so a little later than the period that was mentioned in the post, that did not focus on adult women but demonstrated how easy it was in England to buy and sell children for such purposes. It led to a raise in the age of consent from 13 to 16 and prohibited the different methods of coercion that had been reported to be used, which most people, myself included, would regard as good things. But there is one more thing. For whatever reason, the same bill it inspired happened to criminalise "gross indecency"... Even though it was girl children that had been procured for men, according to the report that everybody read. This is one of those cases that demonstrate how common sense, popular ideas, such as "Of course children must not be sexually abused," can be used to slip in certain political ideas that have nothing to do with them.

It's a tough problem that we have to deal with, that certain political actors (and sometimes, regular people reacting to their emotions) try to pit different social causes against each other when it should be entirely possible for all of them to be acknowledged.

And to change the subject a little, the other thing that came into my mind, since the post did mention the American Civil War, was that to bolster support for the abolitionist cause among whites there was this argument that white women were being held in slavery because of the law of matrilineal descent and subjected to sexual abuses by their masters. The idea was that the war should liberate these white women and children who just so happened to be descended from an enslaved African woman a very long time ago. Here are some photos from one of those campaigns featuring children. (Sorry that the link is from Mashable, the source at the bottom says Library of Congress.)

Which is fucked up! I hate it. We're all human and like you mentioned there shouldn't be a distinction between people that are thought not to deserve abuse and those whose abuse is accepted.

That was a long and rambling post... But I guess I had been sitting on these thoughts for a bit.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Day of 'Hamilton,' The Hamilton Education Program in New York City

A Day of ‘Hamilton,’ The Hamilton Education Program in New York City

Hamilton Education Program, 24, May, 2017, Richard Rogers Theater, ‘Hamilton’ (photo Carole Di Tosti)

If you have yet to see Hamilton, an American Musical on Broadway and have been avoiding it because of the “hype” or the ticket prices, rethink the “hype” about the “hype.” I cannot recommend the production enough. I have not reviewed it because I cannot put into words its greatness and…

View On WordPress

#Hamilton An American Musical#Hamilton Education Program#Luis A. Miranda Jr.#The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History#The Rockefeller Foundation

0 notes

Text

Lin-Manuel Miranda makes his student program free online

Now, students from coast to coast can proclaim that “Hamilton” is in the house. Their house.

Not the film version of the megahit Broadway musical; that is planned for release in October 2021. What’s on-screen today is the popular companion in-school program known as EduHam, which is being made available digitally through August, free of charge, to teachers, parents and pupils everywhere.

The launch of EduHam at Home was announced Tuesday by “Hamilton” creator Lin-Manuel Miranda and his partners in the venture: producer Jeffrey Seller, the Rockefeller Foundation and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, which developed the curriculum. The program uses a love of the musical to spark students’ interests in creative pursuits and tie them to historical research.

EduHam was born as an offshoot of “Hamilton” itself, and Miranda says the project — in which 250,000 students nationwide have participated — has proved to be a hit as much with cast members as younger people.

“It quickly became our favorite thing we do as a company,” Miranda said in a telephone interview. “I am so inspired seeing what these kids draw on and are able to create.”

The digital version, available for download at gilderlehrman.org/eduhamhome, has been in development for a while. The launch was moved up as Miranda and others recognized a need for kids to have educational projects at home during the coronavirus-induced shutdown of classrooms.

“As a parent, I’ve been so grateful for the curriculum that has popped up online,” the actor-composer said, adding that he’s been a de facto “kindergarten teacher” for his own children: Sebastian, 5 and Francisco, 2. Other Broadway hits are unveiling home online versions of their school-based curriculum now, too: Disney Theatrical Productions, for instance, has just released “The Lion King Experience” (LionKingExperience.com), which trains students in the process of staging their own versions of the musical.

...

The program has the additional advantages of keeping “Hamilton” current, and forging a connection to the musical in parts of the country that it has not been able to reach in person. The show itself, which employs 450 people in its six companies, is temporarily sidelined, as are some of Miranda’s other projects. He said he was two weeks into directing a Netflix film version of “Rent” creator Jonathan Larson’s musical “Tick . . . Tick . . . Boom!” when the virus forced production to shut down. As a result, Miranda’s directorial debut is on hiatus, too.

“It’s a time to cope, for the most part,” he said of the suspension of normal life. “That’s not, though, not to mourn the alternate timeline.”

youtube

43 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey there, so I really like history as a subject, and I'm pretty good at it. The thing is, I don't know what my career options would be if I studied it, or if I would be able to make money. My parents are heavily discouraging me from taking it as a major. As a 'historian' in training' what's your take? Thank you

Hi there! Sorry for the delay, ‘tis the hectic season…

Oh man, I have so many thoughts for you. Full disclosure: this is something I have worked on a LOT over the course of my graduate career both at my uni and on a national level; most of my advice, however, comes from a PhD candidate’s perspective and may not be directly helpful to an undergraduate, and I should also emphasize that everything I can say on this is very firmly based on the U.S. market only. That being said, a lot of what I can say can be universally applied, so here we go -

The number of history undergraduates in the U.S. has plummeted in the last decade or so, from it previously being one of the most popular majors. There are many interacting reasons for this: a changeover from older to younger, better-trained, energetic professors who draw in and retain students has been very slow to occur, partly because of a lack of a mandatory retirement age; the humanities have been systematically demonized and minimized in favor of the development of STEM subjects, to the occasional benefit of students of color and women but to the detriment of critical public discourse and historical perspective on current events; with many liberal arts colleges going under financially and the enormous expansion of academic bureaucracy everywhere, resources are definitely being diverted away from social and human studies towards fields which are perceived to pay better or perceived, as mentioned in the article above, as being more ‘practical.’ (We do need a ton more healthcare workers/specialists, but that’s a different conversation to have.) But now I feel like quoting a certain Jedi Master: everything your parents say is wrong. Let’s dive into why being a historian is a positive thing for you both as a person and as a professional -

You will be a good reader. As you learn to decipher documents and efficiently and thoroughly read secondary literature, you will develop a particular talent for understanding what is important about any piece of writing or evidence (and this can go for visual and aural evidence as well). This will serve you well in any position in which you are collecting/collating information and reporting to colleagues or superiors, and evaluating the worth of resources. Specific example - editorial staff at publishing houses either private or academic, magazines, etc.

You will be a good writer. This will get you a good job at tons of places; don’t underestimate it. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been astonished (not in a punitive way, of course, but definitely with a sense of befuddlement) by how badly some of my Ivy-league students can write. Good writing is hard, good writing is rare, and good writing is a breath of fresh air to any employer who puts a high premium upon it in their staff. History in principle is the study of change; history in practice is presenting information in a logical, interesting, and persuasive manner. Any sort of institution which asks you to write reports, summaries, copy, etc. etc. will appreciate your skills.

You will be a good researcher. This sounds like a given, but it’s an underappreciated and vital skill. Historians work as consultants. Historians work in government - almost every department has an Office of the Historian - and in companies, writing company histories and maintaining institutional archives. A strong research profile will also serve you well if you want to go on to work in museum studies and in libraries public or private/academic. As a historian, you will know not just where to find information, but what questions you have to ask to get to the answer of how to tackle, deconstruct, and solve a problem. This is relevant to almost any career path.

You will provide perspective. Historians react to current events in newspapers and online - not just on politics, but culture as well (my favorite article of this week is about the historicity of The Aeronauts). Historians act as expert witnesses in court proceedings. Historians write books, good books, not just meant for academic audiences but for millions upon millions of readers who need thoughtful, intelligent respite from the present. Historians work for thinktanks, providing policy analysis and development (a colleague of mine is an expert on current events of war in Mali and works for multiple thinktanks and organizations because of it). Historians work for nonprofits or lobbying groups on issues of poverty, environmental safety, climate change, and minority and indigenous rights. In a world when Texas school textbooks push the states’ rights narrative, historians remind us that the Civil War was about slavery. Historians remind us that women and people of color have always existed. In this time and world where STEM subjects are (supposedly) flooding the job market, we need careful historical perspective more than ever. We need useful reactions to the 2016 election, to the immigration travesties on display at the southern border, to the strengthening of right-wing parties in Europe - and history classes, or thoughtfully historical classes on philosophy and political science, are one of the few places STEM and business students gain the basic ability to participate in those conversations. [One of my brightest and most wonderful students from last year, just to provide an anecdote, is an astrophysics major who complained to me in a friendly conversation this semester that she never got the chance to talk about ‘deep’ things anymore once she had passed through our uni’s centralized general curriculum, which has a heavy focus on humanities subjects.]

You will be an educator. Teaching is a profession which has myriad challenges in and of itself, but in my experience of working with educators there is a desperate need for secondary-school teachers in particular to have actual content training in history as opposed to simply being pushed into classrooms with degrees which focus only on pedagogical technique. If teaching is a vocation you are actually interested in, getting a history degree is not a bad place to start at all. And elementary/high schools aside, you will be teaching someone something in every interaction you have concerning your subject of choice. Social media is a really important venue now for historians to get their work out into the world and correct misconceptions in the public sphere, and is a place where you can hone a public and instructive voice. You could also be involved in educational policy, assessment/test development (my husband’s field, with a PhD in History from NYU), or educational activism.

If some of this sounds kind of woolly and abstract, that’s because it is. Putting yourself out there on the job market is literally a marketing game, and it can feel really silly to take your experience of 'Two years of being a Teaching Assistant for European History 1500-1750’ and mutate it to 'Facilitated group discussions, evaluated written work from students [clients], and ran content training sessions on complex subjects.’ But this sort of translation is just another skill - one that can be learned, improved, and manipulated to whatever situation you need it to fit.

Will you make money? That’s a question only you can answer, because only you know what you think is enough money. That being said, many of the types of careers I’ve mentioned already are not low-paying; in my experience expertise is, if you find the right workplace and the rewarding path, usually pretty well-remunerated.

Specific advice? Hone your craft. Curate an active public presence as a historian, an expert, a patient teacher, and as as person enthusiastic about your subject. Read everything and anything. Acknowledge and insist upon complexity, and celebrate it when you can.

And finally - will any of what I’ve said here make it easy? No, because no job search and no university experience is easy these days. It’s a crazy world and there are a lot of awful companies, bosses, and projects out there. But I do very firmly believe that you can find something, somewhere, that will suit your skills, and, hopefully, your passions too.

Resources for you: the American Historical Association has a breakdown of their skills-based approach to the job market, reports on the job market(s) for history PhDs collectively called ‘Where Historians Work,’ and a mentorship program, Career Contacts, which could connect you with professional historians in various workplaces. There is a very active community of historians on Twitter; search for #twitterstorians. For historians who identify as female, Women Also Know History is a newer site which collates #herstorian bios and publications to make it easier for journalists to contact them for expert opinions. ImaginePhD provides career development tools and exercises for graduate students, but could probably be applied to undergrads as well. The Gilder Lehrman Institute is one of the premier nonprofits which develops and promotes historical training for secondary school teachers and classroom resources (U.S. history only). Job listings are available via the AHA, the National Council on Public History, and the IHE, as well as the usual job sites. And there’s an awful lot more out there, of course - anyone who reads or reblogs this post is welcome to add field-specific or resource-specific info.

I hope this helps, Anon, or at least provides you with a way to argue in favor of it to your parents if it comes to that. Chin up!

142 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#Repost @araujohistorian • • • • • • THURSDAY!!!! #Repost @aswadiaspora ・・・ Thank you for joining our 1st IG Live Book talk! Our next talk is September 3rd at 5pm est, when Jessica Marie Johnson discusses her new book, Wicked Flesh: Black Women, Intimacy, and Freedom in the Atlantic World (Pennsylvania University Press, 2020) with Tyesha Maddox. _______ Wicked Flesh: Black Women, Intimacy, and Freedom in the Atlantic World (2020). The story of freedom and all of its ambiguities begins with intimate acts steeped in power. It is shaped by the peculiar oppressions faced by African women and women of African descent. And it pivots on theself-conscious choices black women made to retain control over their bodies and selves, their loved ones, and their futures. Slavery's rise in the Americas was institutional, carnal, and reproductive. The intimacy of bondage whet the appetites of slaveowners, traders, and colonial officials with fantasies of domination that trickled into every social relationship—husband and wife, sovereign and subject, master and laborer. Intimacy—corporeal, carnal, quotidian—tied slaves to slaveowners, women of African descent and their children to European and African men. In Wicked Flesh, Johnson explores the nature of these complicated intimate and kinship ties and how they were used by black women to construct freedom in the Atlantic world. ____________ JESSICA MARIE JOHNSON is an Assistant Professor in the Department of History at the Johns Hopkins University. A historian of Atlantic slavery and the Atlantic African diaspora, Johnson researches black diasporic freedom struggles from slavery to emancipation. As a digital humanist, Johnson explores ways digital and social media disseminate and create historical narratives, in particular, comparative histories of slavery and people of African descent. She is the recipient of research fellowships and awards from the Woodrow Wilson Foundation, the Gilder-Lehrman Institute, and the Richards Civil War Era Center and Africana Research Center at the Pennsylvania State University, and the Mellon Postdoctoral Fellowship Program in the Program in African American History at the Library Company of Philade https://instagr.am/p/CEolp18gu0h/ Follow #ADPhD on IG: @afrxdiasporaphd

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Review “A shrewd history of the fight to convey and repress objective truth.”—Kirkus “A lively and informative work that will appeal to anyone interested in American history, politics, and journalism.”—Library Journal “Harold Holzer has brought us a sweeping, groundbreaking and important history of the conflict between American presidents and the press, and it could not arrive at a more crucial moment.”—Michael Beschloss, NBC News presidential historian and New York Times bestselling author of Presidents of War “Harold Holzer's fascinating new book beautifully narrates the long history of contention between the press and the White House, but it does more than that. Presidential politics were born at the dawn of popular newspaper writing, and the fighting, seducing, and conniving on both sides has continued ever since. Presidents and reporters can't really exist without each other, and Holzer, a historian of the presidency with the eye of a reporter, expertly explains why.”—Sean Wilentz, Pulitzer Prize finalist and author of The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln “Harold Holzer is a master in telling us exactly what we need to know—no more, no less—on a critical and obsessive relationship spanning 200 years. With a gimlet-eye, Holzer shows how some of our best presidents—from George Washington to Abraham Lincoln to Barack Obama—were the most resistant to press scrutiny.”—Jonathan Alter, New York Times bestselling author of His Very Best: Jimmy Carter, A Life “Not surprisingly, George Washington was the first president to protest ‘the malicious falsehoods’ and ‘violent abuse’ he’d suffered from the press. In this vivid, anecdotal history, Harold Holzer, himself a shrewd veteran of political press relations as well as a fine historian, chronicles the ways in which Washington and eighteen of his most important successors have sought to seduce and cajole, defy and sometimes conspire with the men and women who cover them. No one interested in the presidency—or in the long history of ‘fake news’—should miss it.”—Geoffrey C. Ward, New York Times bestselling author of A First Class Temperament: The Emergence of Franklin Roosevelt “From George Washington railing against ‘infamous scribblers’ to the ravings of Donald Trump against ‘fake news,’ there is an inherent tension between presidents and the press. Harold Holzer brings this centuries-long struggle to life in a brisk, enjoyable and authoritative book that offers valuable perspective on the art of governing while shining a light on how the free press is still the ultimate guarantor of freedom.”—John Avlon, CNN Senior Political Analyst and author of Washington's Farewell: The Founding Father's Warning to Future Generations About the Author Harold Holzer is the recepient of the 2015 Gilder-Lehrman Lincoln Prize. One of the country's leading authorities on Abraham Lincoln and the political culture of the Civil War era, Holzer was appointed chairman of the US Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission by President Bill Clinton and awarded the National Humanities Medal by President George W. Bush. He currently serves as the director of the Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute at Hunter College, City University of New York.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

“Charley loves his Father very much,” by Charley Burpee, who was about four years old in 1864— Found on the body of his father, a soldier in the Civil War

The Charley in question was Charley Burpee, who was about four years old in 1864—the year he scrawled those loops and scribbles. He was writing to his father, Thomas, a soldier from Connecticut who began serving in the Civil War as a Union Army captain on July 12, 1862. Within a few months of receiving his son’s letter, Thomas was wounded at Cold Harbor, Virginia. He died two days later. Charley’s scribbles were among the personal effects given to the family when his body was shipped home.

Charley’s letter is a rarity. While many letters written by Civil War soldiers have survived, there are few remaining letters that were written by soldiers’ families and delivered to the battlefield. - The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Come on, come on, come on: get through it

NOTE: A lot of people who have read this have shared their condolences and well wishes, which is really nice. Some have also asked if there was anything they could do for Sean’s family, which is amazing. If you’re able and feel moved to, there is: There’s a college fund for Winnie. Thanks to everyone who has reached out.

***

One of the best friends I’ll ever have died on November 29, after a fight with cancer. He was 36, and he leaves a wife and a young daughter, all of which is an infuriating sin. I’ve been trying to find a way to sit with that. I’m not sure how well I’ve been doing.

I gave the eulogy at his funeral mass. Whenever I’ve talked to people about that, they have apologized to me, have said they were so sorry that I got asked to do that, that I had to do that. It’s weird: I never looked at it like that.

I feel so lucky that I got to know Sean Enos-Robertson -- to really know him, what he cared about, what he loved, what made him so special. You rarely get to know anybody like that, and when you do, sometimes you don’t wind up liking what you see. That never happened with Sean; he was a font of joy, someone who lived to make the lives of others just a little bit better. His wife asked me if I’d write something down and talk to people about this beautiful, amazing person I was so lucky to know. That wasn’t a burden. It was a privilege. An honor.

And now, a few weeks later, as I’m trying to figure out how to process this, I keep thinking that I’d like to share that.

You guys won’t get to know Sean, which is so, so decidedly your loss. But maybe this lets you know how much he meant to me, to us, and to so many other people, and it makes you think about the people who mean this much to you. And maybe you tell them.

Maybe you tell them while you have the chance, because telling people you care about them, and who they are in your life, and why you love who they are full stop is one of the best things there is, and there’s never a wrong time for it so long as it’s before the end. I got to tell Sean how I felt before he died, and I got to tell his family, and his friends, and his students -- my God, his students -- and now I’m telling you. Sean Enos-Robertson was brilliant, the best, a light in a lot of lives. I miss him, and I love him, and I always will. Here’s why.

***

Hello, everybody. My name is Dan Devine, and I'm a friend of Sean's. I am a friend of Sean's. I'm not going to use the past tense for that; it didn't stop being true last Thursday, and it's never going to.

On behalf of Courtney and Winnie, and of the Robertson and Enos families, I'd like to thank you for being here. In a broad sense, Sean believed in community: in the power of people uniting for a common good. More specifically, Sean believed in love. He loved his family — his wife and daughter, his parents and in-laws, his brother and grandmother. He loved his friends. He loved his students and colleagues. He loved the people he leaned on, and who leaned on him — those of us here today, and many others who couldn't make it, but are sharing their love, and our grief.

Sean was one of my favorite people. He was magnetic. He was invigorating. He was cool as hell.

Sean radiated. He was a candle: someone who lit up and warmed every room he walked into, every person whose life he touched. This ... this is a tough room to light up. So we're going to have to do it together.

Before we do it, though, I want to acknowledge a hard truth I've been sitting with, and that you might be sitting with, too. It is deeply, impossibly unfair that Sean is gone — that he was taken from us so soon. Too soon. Way, way, WAY too soon. That's real, and it's OK to feel that.

In my better moments, though, I can set that aside and make room for gratitude — that Sean walked into my life in the first place, that I got as much time with him as I did, and that I got so much exposure to such a shining example of how to love.

There's a song by Tom Petty that I really love called "Walls." There's a line in the chorus that goes, "You got a heart so big, it could crush this town." That was Sean. Sean loved openly, fearlessly, completely — he hugged like you could win medals for it. He loved with everything he had, with his whole body. And if you don't believe that, then you never saw my man dance.

He loved music, and especially sharing it — I don't think anybody made me more mix CDs to try to put me onto something that I hadn't heard. (I'm pretty sure I have about five different "best of Blur" mixes. Sean really loved Blur.)

youtube

I met Sean at Providence College in the fall of 2000, right near the start of our freshman year. I'd seen him around at meetings for people who wanted to apply for shows on the college radio station, WDOM, but we didn't become friends right away. I know exactly when that happened: October 29, 2000. (I looked it up.)

That night, Mike Doughty, the singer from Soul Coughing, played a solo show at the Met Cafe in downtown Providence. I took the PC shuttle downtown by myself to catch the show, and somewhere around the weird acoustic cover of "Real Love" by Mary J. Blige, I saw that tall, skinny dude again. We awkwardly sidled up to one another to watch the show, and wound up walking back to campus together. We talked about bands and school and the station and whatever else two 18-year-olds talk about, all the way back home, and that was that. From that moment on, that was my man.

We hung out a lot, as evidenced by the staggering number of old photos I've looked through recently in which one or both of us had extremely tragic haircuts, facial hair, or sideburns. We lived together for two wonderful years in an awful apartment in Cranston, R.I.

The first year, we lived with our friend Todd. We had two parking spots for three cars, so one of us would always be blocking somebody in. Whenever it was time for the blocked-in person to get out, he'd ask, "Are you behind me?" And always, every time, Sean would answer, "100 percent, man."

It was this small, dumb thing, but it always made me laugh. Sean was really good at that.

We learned how to be adults together, finishing school and trying to figure out how to pursue our passions. After searching a little, Sean found his. In 2007, he took a job teaching history to middle schoolers at Harlem Academy. He shared with scores of students his belief in civic responsibility, in actively engaging with our nation's past, in interrogating history to learn about how we got where we are and how we might make decisions about our future. He loved teaching, and he was incredible at it. In 2016, the Gilder-Lehrman Institute of American History named him the New York State History Teacher of the Year, and they don't just give that out.

Sean's commitment to his students went beyond the classroom. I got a much clearer picture of that when Courtney sent me a note she received after his passing from one of his students, sharing both condolences and her memory of Mr. Robertson as someone who "would always reach out to me when he thought I needed it." One day, in eighth grade, this student confided in Sean that she thought she wanted to be an artist. She braced for stereotypical adult dismissal, the classic speech about "getting a real job."

Instead, she got a giant smile and an inspiring conversation about Courtney's job as a graphic designer, about that being a real path, and about how she might be able to realize her dream. Courtney invited her to visit her job to see firsthand how it was done, and that it could be done. She's kept that dream throughout high school, and now into college, thanks in part to Sean's willingness to listen, to care, and to open his life to a student in need. I'm willing to bet there are a lot more stories like that.

The student concluded her note with a beautiful sentiment: "I pray that you and Winnie and the rest of Mr. Robertson's family and friends are able to find peace and comfort, and I pray that you are able to think of him and feel peace and joy, because I genuinely think that's what he would want." I think she's exactly right. Sean wanted to lift people's spirits, to lighten their moods; on the day he invited some of us Brooklyn friends over to tell us that his fight was coming to an end, he kept moving back and forth among playlists of incidental music, setting a soundtrack to hum underneath all the laughs and tears and reminiscing. Even then, dude was still DJing.

We learned how to be somebody's partner, and eventually somebody's husband, together. Sean met Courtney in 2002, and as I remember it, he knew very, very quickly that he'd hit the jackpot. I'm sure that they had their share of tough times over the years, especially recently, but they always seemed immensely supportive of one another. Their love, from the outside, always seemed easy, in that way that let you know it was right, secure for the long haul.

Something Sean and I had in common, and that I've always felt grateful for, is that we always knew our magnetic north. Everything in our life oriented around the person we wanted to spend it with, and wherever work or school or whatever tossed us, we could always go back to that, back to our person, and get pointed in the right direction. Courtney was his compass, his best reason for doing everything.

When they were going to get married, Sean asked me to stand up with him as his best man, and to give a toast. I dug that toast out of a box last week, and here's the part that matters: "I think that all guys — the honest ones, at least — will admit that the women in our lives do a lot of the heavy lifting in helping us become decent, valuable men. And this is no exception [...] When Sean called to tell me that he and Courtney had gotten engaged, the first thing I remember thinking is, 'They deserve each other.'"

Their time together deserved a better ending than this. But what came before — the 16 years of knowing this great a love was possible, the nine years of marriage, the two and a half years of Winnie's life? That was exactly what they deserved.

Courtney is one of the strongest, fiercest, most remarkable people I've ever met — a woman who has faced unimaginable challenges and kept putting one foot in front of the other. I can't fathom what today is like for you, Courtney, but I want you to know: we are going to be awesome for you and Winnie right now. And tomorrow, and the next day, and all the days after that. I'm sorry, but you're stuck with us.

We learned how to be fathers together. Sean was there for me when my Siobhan was born, ready to cradle this tiny thing in his arms and envelop us with love, and to look me in my bloodshot, frantic eyes and let me know that I didn't have to be OK, because I was never going to be alone with it all. I wanted to do the same for him when Winnie was born, but Sean never seemed to need it. He was just ready: all open arms and full heart and perfect love.

Winnie is amazing, and brave, and funny, just like her dad. She's one of my favorite people, too, and I ache for her. But I'm also so grateful that there are so many people who will line up to tell her just how fantastic her father was. She will always know how special he was, and how special she was to him, and how much he loved her. We'll make sure of that. It might be the most important thing any of us do once we leave here today.

This hurts. This is hard. It's not supposed to go like this. But we don't get to make these kinds of choices. All we can do is deal with the fallout.

I'd ask you to remember the words of Sean's student: "I pray that you are able to think of him and feel peace and joy." Sean Enos-Robertson spent 36 years doing everything he could to bring peace and joy to everybody he met. Sean loved with his whole soul, and we can do that, too. We can do that for him. Let's be candles. Let's radiate.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

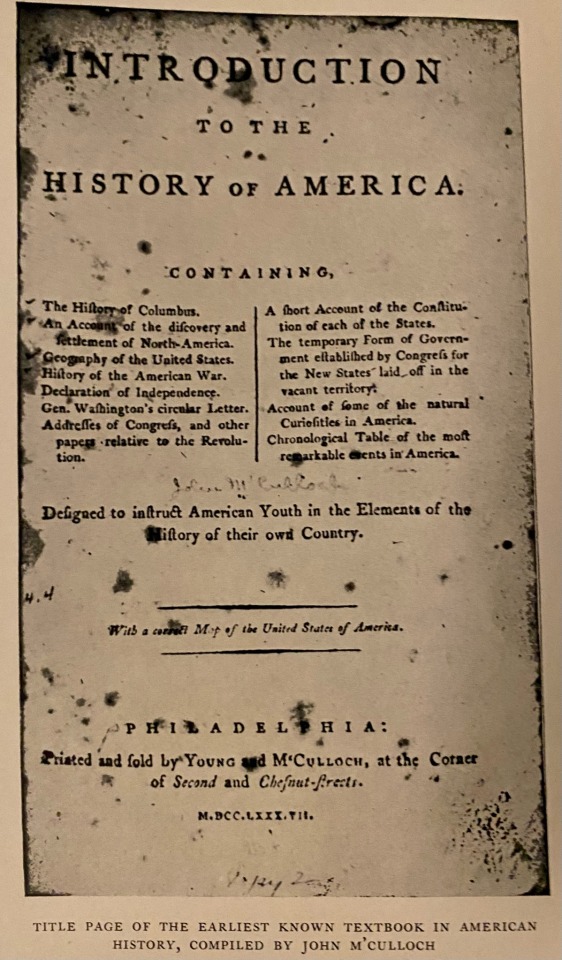

Introduction to the History of America by M’Culloch is generally accepted to be the oldest American history textbook. It was first published in 1787. There is no author listed, but the publisher is John M’culloch. Unfortunately it’s one of the few old textbooks not available for free online. I hope to change that one day, but for now all the digital copies are behind a paywall.

If you are a student or educator, you can check if your institution has access to to Gilder Lehrman’s digital collections.

https://www.gilderlehrman.org/collection/glc00920

It’s also available via Evans Digital Editions:

http://opac.newsbank.com/select/evans/20471

0 notes

Photo

EXPLORE THE WORLD OF ALEXANDER HAMILTON

Ahead of the release of Hamilton on Disney+ on July 3, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History invite you to take a deep dive into the world of Alexander Hamilton.

0 notes

Photo

Hamilton Goes to High School (EducationNext):

[. . .] Miranda knew how empowering it feels for a young person to create his own artistic project; indeed, that’s how he got his start in musical theater. He wrote three original songs when he was in 8th grade to help teach classmates the content of The Chosen, a novel by Chaim Potok set in 1940s Brooklyn. “My first musical I ever wrote was a class assignment,” Miranda revealed to Arrive magazine.

Hamilton producer Jeffrey Seller himself has a history of bringing Broadway to high school students. He created an educational program for the 1990s musical Rent, his first theatrical success.

And Gilder Lehrman has a long track record of developing history programs that benefit schools. Indeed, two-thirds of the students who take AP U.S. History visit the institute’s web site, and its total traffic jumped to 10 million visitors last year, up from fewer than 2 million two years ago. So when Seller and Miranda’s father, Luis Miranda Jr., visited Gilder Lehrman’s 45th Street office last summer, the institute’s director of education, Tim Bailey, showed them a recent curriculum program he had written called Vietnam in Verse. The lesson plan used poetry and music from the 1960s and ’70s to address the issues of that era. Seller was impressed: “You’re in,” he told Bailey. A partnership was born.

Working through the finances to create the education program was a complicated task. The first hurdle was to get the production to discount all seats for the student matinees. About 1,100 of the Richard Rodgers Theatre’s 1,321 seats cost between $179 and $199 apiece for a performance of Hamilton. The 200 or so center-orchestra seats fetch $849, by far the highest ticket price on Broadway. The play, which nets close to $2 million per week, is sold out until November 2017. The play’s principals agreed to sell the tickets for student matinees for $70, essentially the breakeven price point.

In October 2015, the Rockefeller Foundation put up $1.5 million to pay for Gilder Lehrman to create the curriculum and to subsidize $60 of each student ticket. Students pay the remaining $10 (a “Hamilton”) for each ticket, so they’re invested (except in San Francisco, where students attended for free because of a strict state law that prohibits them from paying for any educational experiences).

“Works like this don’t come around very often, and when they do we must make every effort to maximize their reach,” says Judith Rodin, former president of the Rockefeller Foundation. “Here’s a story that talks about American history and the ideals of American democracy . . . in a vernacular that speaks to young people, written by a product of New York public education,” Rodin told the New York Times. “Could there possibly be a better combination in terms of speaking to students?”

In June 2016 the foundation upped its commitment to $6 million to fund year two of EduHam in New York City and extend it to Chicago and the touring company.

[. . .]

The Curriculum

When Gilder Lehrman’s Tim Bailey started working on the Hamilton Project in late 2015, he knew he wanted to have students deal directly with primary sources. Gilder Lehrman owns 60,000 documents from American history, and Bailey recognized the value of reading and responding to these original materials. Secondary sources that merely summarize such documents and the events behind them tend to simplify the subject and rob students of the opportunity to analyze and interpret them for themselves. And the Common Core State Standards call for increased use of primary documents. But Bailey knew that asking students to read documents written more than 200 years ago could prompt lots of eye rolling.

Gilder Lehrman’s Basker puts it more succinctly: teaching the founding of the country can be the “castor oil of education,” he quips.

Bailey says that to capture kids’ interest in primary materials, “We have to teach the students the skills to unlock those sources. We provide enough structure so that students won’t freak out.”

[. . .]

Multimedia Materials

While Bailey worked on the classroom materials, colleagues set up a private Web portal where students could see excerpts from five songs performed during the show. The play’s creators insisted on limiting how much of the piece they would expose, for fear of diluting the play’s potential earnings on tour. Still, says Bailey, “We have amazing access to the show. It’s unprecedented.”

On the web site, students can view nine video interviews created exclusively for them. The videos feature Miranda explaining how Hamilton was different from other Founding Fathers, Chernow discussing the artistic license used in nonfiction writing, and actors reading from original documents of the period.

In one video, Miranda holds an actual love letter from Hamilton to his future wife Eliza and reads: “You not only employ my mind all day; but you intrude upon my sleep. I meet you in every dream and when I wake, I cannot close my eyes again for ruminating on your sweetness.” He looks up and tells students, “This puts whatever R&B song you’re listening to right now to shame.”

The web site also features information on 30 different historical figures, ranging from Martha Washington to Hercules Mulligan, the tailor who used his access to British troops to spy for the patriots. The site highlights 14 key events from the era, as well as 20-plus documents, including The Federalist Papers and Thomas Paine’s Common Sense.

While EduHam’s materials are robust, the program requires only two to three class periods to complete, Bailey says. Most of the student work, such as the suggested three hours of rehearsal, takes place outside the classroom. The program includes an 11-page teacher guide that discusses objectives, procedures, and the four Common Core standards the lessons align with. There is also a rubric to guide teachers in assessing student work.

Students are given wide latitude as to what, and how, they perform in EduHam. They can present a rap, song, poem, monologue, or scene. And while their performance must represent the Revolutionary War era, they can choose from key people, events, or documents, even if they aren’t in the play. During the November 2016 performances, one group of students compared the struggle between America and Britain to the Crips–Bloods gang battles in California. Students’ reactions were so enthusiastic it was hard to hear the end of the performance. One girl recited poetry about the African American poet Phillis Wheatley, who isn’t in the play, and another reworked the rapper Drake’s piece “5AM in Toronto” to depict the Boston Massacre.

[. . .]

Including Controversy

Of course, not all the drama around Hamilton has occurred onstage. At a performance in late November 2016, the cast addressed Vice President Elect Mike Pence, who was in the audience.

Actor Brandon Victor Dixon, who played Aaron Burr in that performance, told Pence: “We, sir, are the diverse America who are alarmed and anxious that your new administration will not protect us, our planet, our children, our parents, or defend us and uphold our inalienable rights. We truly hope that this show has inspired you to uphold our American values and to work on behalf of all of us.”

Miranda, who is prolific on Twitter, is not shy about trumpeting his political views, which lean decisively to the left.

When asked if this controversy would make schools less likely to use the play as a learning tool, Lawrence Paska says: “That’s going to depend on local school curriculum choices and planning. Some teachers and schools may use recent events as a way to highlight the intersection of history, art, and current events. Others may choose not to use works like Hamilton because they want to focus on historical events and not on recent activism.”

[. . .]

As Miranda tells students when they come to see the play, the big question is, “What kind of world do we want to create? It’s no less than that. What kind of world are you going to create when you grow up?”

amazing in-depth article on the #eduham program -- read the full piece!

#hamilton#eduham#education#history education#gilder lehrman institute of american history#lin manuel miranda#jeffrey seller#educationnext

75 notes

·

View notes